A Federal Adaptive, On-Demand Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Initiative

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need to address lags in American pharmaceutical manufacturing. An investment of $5 billion over five years will improve U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure, including the development of new technologies that will enable the responsive, end-to-end, on-demand production of up to half of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) list of 223 essential medicines by year two, and the entire portfolio by year five. Spearheading improvements in domestic manufacturing capacity, coupled with driving the advancement of new adaptive, on-demand, and other advanced medicine production technologies will ensure a safe, responsive, reliable, and affordable supply of quality medicines, improving access for all citizens, including vulnerable populations living in underserved urban communities, rural areas, and tribal territories.

Challenge and Opportunity

Urgent Need to Strengthen U.S. Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

COVID-19 has served as a wake-up call and an opportunity to bring pharmaceutical manufacturing into the 21st century. Production factory closures, shipping delays, shutdowns, trade limitations, and export bans have severely disrupted the supply chain. Yet the demand for vaccines and COVID-19 treatment options worldwide continues to increase. However, recent advances in manufacturing technology can be deployed to create a 21st century domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing economy that is distributed, flexible, and scalable, while producing consistent high-quality medicines that Americans rely on.

To improve national security and achieve the goal of medicine production self-sufficiency, the Biden-Harris Administration has an opportunity to address legacy issues plaguing the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry and usher in a technology revolution that will leapfrog our legacy 19th century industrial manufacturing processes. The Biden-Harris Administration should prioritize:

Improving the domestic production of small-molecule medicines, including Key Starting Materials (KSMs) and Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) in order to reduce dependence on foreign manufacturers. China and India together supply 75- 80 percent of the APIs imported to the U.S.1 In March, during the largest spring spike in U.S. COVID-19 cases, India restricted the export of 26 APIs as well as finished pharmaceuticals. The U.S is the leading market for generic pharmaceuticals, with 9 out of every 10 prescriptions filled being for generic drugs in 2019, and a projected market value of $415 billion by 2023.2 An aggressive race to the bottom in terms of price has driven the vast majority of supply chain manufacturing overseas, where lower production costs and government subsidies, particularly for exports, benefit foreign suppliers.

Improving the scale, efficiency, and effectiveness of domestic biopharmaceutical manufacturing. The past decade has ushered in a significant shift in the nature of pharmaceutical products: there is now a greater prevalence of large molecule drugs, personalized therapeutics, and a rise in treatments for orphan diseases. New approaches to developing vaccines, such as the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine, are setting a new paradigm for future vaccines using DNA, RNA, adenoviruses, and proteins. There is an urgent need to scale up the domestic manufacturing of biologics, including vaccines, to address biomedical threats. In addition, innovation in manufacturing technology is critical to improving both scalability and time to market. New technology will improve yields while lowering costs and reduce waste through green chemistry.

Additional benefits associated with establishing a robust domestic manufacturing base, including distributed manufacturing capability, include:

Reducing vulnerabilities associated with an over-reliance on centralized manufacturing and processing models. In the food industry, a COVID-19 outbreak in just a few chicken and pork processing plants led to a nationwide shortage of these important foods. A more flexible, resilient distributed manufacturing model, such as one utilizing additive manufacturing and 3-D printing, would have prevented the need for such a disruptive response. 3-D printing, for example, has successfully delivered more than 1,000 parts to local hospitals during the pandemic.

Improving the reliability of facilities and the quality of products for the U.S. market through the development and deployment of advanced manufacturing technologies. Low-cost, offshore manufacturing raises quality risks; more than half of FDA warning letters issued between 2018 and 2019 were sent to facilities in India or China.4 There are numerous examples of risks to both the health and security of U.S. citizens in the recent past. In 2007, a Chinese company deliberately contaminated the blood thinner Heparin and 246 Americans died. In 2015, the FDA banned 29 products after inspecting a Chinese pharmaceutical factory, although it exempted 14 products over U.S. shortage concerns. And in 2018, a Chinese vaccine maker sold at least 250,000 substandard doses of vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, and whooping cough.

Improving access for vulnerable populations living in underserved urban communities, rural areas, and tribal territories. COVID-19 created unprecedented pressure on the federal system when requests from 56 State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) authorities nearly simultaneously requested medical supplies. According to testimony presented by the RAND Corporation, the quantities of material in the Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) were not nearly enough to fill all of the requests, resulting in a heated competition and a failure to deliver products to all of the different parts of the United States equitably.

Reducing critical drug shortages that have plagued U.S. health systems for more than a decade. With COVID-19 cases on the rise, and hospitalizations increasing in more than 40 states, critical drug supplies are waning, with 29 out of 40 drugs used to combat the coronavirus currently in short supply. In addition, 43% of 156 acute care medicines used to treat various illnesses are running low. In 2019 the U.S. experienced 186 new drug shortages; 82% of which were classified as being due to “unknown” reasons, largely because of the intentional opacity and secrecy of the upstream supply chain. According to the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) the U.S. health system spends more than $500 million a year on estimated costs related to drug shortages, with approximately $200 million in direct costs and up to $360 million on indirect costs.

Stabilize pricing by enabling ‘just in time’ manufacturing capability that reduces the need to stockpile large supplies of medicines and is more responsive to surges in demand. Furthermore, complex supply chains, procurement mechanisms, and the consolidation of U.S. buyers create ‘pay-to-play’ schemes that contribute to chronic drug shortages by driving manufacturers out of the market and contribute to price volatility. New technologies that enable responsive and efficient approaches to surges in demand, or to address drug shortages, will also stabilize pricing over time. Today, one in four Americans cannot afford their medication. Mylan, for example, increased the price of EpiPen by more than 500%, from $94 for a two-dose pack in 2007 to $608 in 2018.

21st Century Problems Require 21st Century Solutions

Advanced manufacturing technologies such as continuous flow, which allows for drugs to be produced in a continuous stream, can reduce the time it takes to manufacture a drug and ensure quality through advanced controls and process analytic technologies. These technologies can enable remote monitoring during production and real-time release testing. In addition, miniaturized manufacturing units that could easily fit in existing pharmacies would facilitate a distributed network for producing medicines that is flexible enough to rapidly pivot and make any therapeutic required for national security or emergency preparedness with short lead times. A distributed network of on-demand pharmaceutical manufacturing devices will improve supply availability without the need to stockpile large quantities of medications.

Automation will play a key role in advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing, as will 3-D printing. Automation will reduce manufacturing overheads and ensure quality, scalability, and increased outputs. It allows advanced connectivity of equipment, people, processes, services, and supply chains. The 3-D printing of pharmaceutical products, meanwhile, is accelerating following the FDA’s approval of the first 3-D printed drug in 2015. This technology accommodates personalized doses and dosage forms and other emerging technologies that enable bespoke tablet sizes, dosages, and forms (suspension, wafers, gel strips, etc.) to optimize patient compliance and ease of use. Another major advantage is the possibility of redistributed manufacturing–printing medicine much closer to the patient. 3-D printing and on-the-spot drug fabrication will have major implications in medical countermeasures and for medications with limited shelf-life.

Finally, investing in advanced biopharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure and innovation would establish the capacity to produce domestically through a network of high-tech, end-to-end manufacturing and development solutions, which will ensure that the medicines of today and tomorrow, such as new vaccines, can be made quickly, safely, and at scale.

Plan of Action

The Biden-Harris Administration should launch a national adaptive pharmaceutical manufacturing initiative focused on the ambitious goal of achieving medicine production self-sufficiency. The Presidential Initiative should be led by an Ambassador who reports to the Secretary of Defense. The Secretary of Defense is already leading a whole-of-government effort to assess risk, identify impacts, and propose recommendations in support of a healthy manufacturing and defense industrial base – a critical aspect of economic and national security. The Department of Defense (DoD) coordinates these efforts in partnership with the Departments of Commerce, Labor, Energy, and Homeland Security, and in consultation with the Department of the Interior, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, and the Director of National Intelligence.

Clear deliverables and timeline-dependent milestones are critical to the success of this initiative. New local manufacturing solutions — such as state-of-the-art facilities and devices for automated end-to-end pharmaceuticals to be deployed in a trailer — can augment ongoing efforts to reduce manufacturing ramp-up time, the need for strict environmentally controlled secure storage facilities, and waste from expired medications. Having stand-alone or mobile devices for automated end-to-end pharmaceuticals would empower local authorities to manage delivery and distribution protocols, ensuring that local populations have the lifesaving medicines they need when they need them.

To this end, the DoD, in collaboration with HHS and the FDA, should launch a national initiative to increase U.S. manufacturing capacity and accelerate the development of new technology, with an emphasis on the adoption of advanced analytical capabilities to ensure quality. These platforms should be able to produce precursors, APIs, and final drug products (small molecule and biologics) in multiple forms, enabling rapid response priority medicines on demand, targeting the creation of a self-sustaining domestic supply chain of the 223 medicines on the FDA Essential Medicines list, as well as new vaccines and medicines coming off patent in the next 5 years.

The establishment of a national pharmaceutical manufacturing network will facilitate a U.S. strategic asset that changes how we source, manufacture, and distribute medicines. This robust domestic network will mitigate drug shortages, ensure quality, and allow rapid response to emergency scenarios. Importantly, it re-establishes a domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing industry that relies less on overseas suppliers, advances our country’s innovation prowess, and will create thousands of new U.S. jobs.

Recommendations for the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Defense

To enable a more resilient, responsive and adaptive U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain and achieve medicine production self-sufficiency, the following actions are recommended.

First, sign an executive order that directs the formation of a Joint Interagency Task Force (JIATF) DoD, HHS and FDA, led by a Presidential appointee (Ambassador), with a $5 billion, 5-year funding commitment, to establish a more robust domestic responsiveness that includes advanced manufacturing technologies for biologics and small molecules. A key objective of the executive order and the formation of a JIATF is to ensure the U.S. can produce medicines stateside with improved responsiveness.

This initiative will:

- Identify a portfolio of products that can be rapidly deployed at a national, state or local level utilizing advanced manufacturing platforms, identify associated research and development agenda needs, and determine how this aligns with other initiatives such as the Strategic National Stockpile.

- Support targeted synthetic biology research and development to enable faster manufacturing of low-cost, on-demand vaccines and precision immunotherapies.

- Support the advanced development of green, modular, on-demand small-molecule manufacturing technologies that would accommodate small batch lines, with an ability to scale and produce higher volume when needed. • Support targeted advanced development of sensor technologies that can monitor online and real-time quality control.

- Support the acquisition and/or establishment of new U.S.-based manufacturing facilities.

- Support green technology solutions.

- Establish a center for excellence in advanced manufacturing at the FDA, to support and advance regulatory science.

- Identify new business models to support the economically sustainable domestic adoption and deployment of new manufacturing technology.

- Enact push and pull incentives to direct new medical countermeasure development funded by HHS (Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, BARDA) and other federal agencies to utilize adaptive manufacturing practices as appropriate.

Key milestones and deliverables of this initiative include the following:

- By year 2, ensure that 50% of the FDA’s Essential Medicines are manufactured from end-to-end in the United States, to include starting materials and APIs.

- By Year 5, the FDA will have the capability to manufacture all Essential Medicines in the United States.

- In this same time frame, the quality of every dose of the medicines produced can be provided to the FDA for oversight.

- All starting materials are sourced domestically or from trusted allied nations.

Conclusion

Expanding critical U.S. pharmaceutical manufacturing infrastructure and establishing an adaptive, transparent on-demand pharmaceutical manufacturing capability guarantees safe, secure, high-quality, and reliable supply of affordable drugs and would create thousands of new U.S. high-paying jobs. By utilizing green technology, it could reduce hazardous material waste by as much as 30 percent over conventional manufacturing. It would also improve transparency and supply chain efficiencies that could reduce shortages, lower costs, and improve the quality of medicines. A distributed, modular, on-demand manufacturing network capable of making biologics and small molecules cannot be disrupted by the loss of centralized facilities, natural disasters, pandemics, or adversarial actions. New local on-demand manufacturing solutions will reduce manufacturing ramp-up time, the need for strict environmentally-controlled secure storage facilities, and waste from expired medications. It will empower local authorities to manage delivery and distribution protocols, ensuring that local populations have the lifesaving medicines they need when they need them. In addition, it would offer the potential to improve warfighter resilience and recovery by providing the groundwork for producing medicines on demand, and at the point of care, whether it be on a C-5, submarine, or at a forward combat support hospital.

Rethinking Payment for Prevention in Healthcare

Summary

Prevention plays a crucial and underappreciated role in our health system. To improve health outcomes and bring down costs, it will be important to establish a better balance between preventive measures and drug treatments. The next administration should provide incentives to healthcare providers that scale up—and reduce costs of delivering—preventive interventions with demonstrated efficacy. Currently, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) sets broad standards regarding managed care contracts. But states have considerable latitude. States can set income eligibility criteria, define services, and set alternative payment methods with Managed Care Organizations (MCOs). And in just the last few decades, Medicaid programs have been almost fully privatized: MCOs now cover over 85% of the Medicaid population. Because of the existing patchwork of insurance programs and state rules, it is important that regulations set minimum national standards to ensure that health care is accessible and affordable for those who need it the most. Particularly important to this effort are non- distortionary prices and reimbursement policies.

For a few decades, policymakers have, with bi-partisan consensus, moved away from a fee-for-service (FFS) system whereby providers are paid for service delivery and toward capitation and pay for performance (p4p) models. While these models offer significant improvements over FFS models, each involves risks of incentivizing non-optimal care and expenditures if they are not structured carefully. When paying capitation rates, bonuses adjusting for population risk alone should be avoided as this incentivizes an increase in diagnoses without necessarily improving care. Either all health care payments should be p4p, or a p4p component should be added to the capitation base. Pharmacological interventions should also be included in the overall provider reimbursement structure to align reimbursement incentives with health outcomes. Healthcare providers will then determine the right mix of services. Furthermore, while p4p is generally a good idea (i.e., hospitals and MCOs are rewarded for decreasing the number of avoidable hospital readmissions), if this metric is not applied homogeneously across all services, this payment structure significantly hampers the provision of preventive services.

Elevating Patients as Partners in Management of Their Health Data and Tissue Samples

Summary

From HIPAA to doctor-patient confidentiality, the U.S. healthcare system is replete with provisions designed to ensure patient privacy. Most people are surprised, then, to hear that patients in the United States do not legally own nearly any of their health data: data as diverse as health and medical records, labs, x-rays, genetic information, and even physical specimens such as tissue and blood removed during a procedure.

Providing patients with agency over their health data is necessary for elevating patients as partners in their own health management—as individuals capable of making genuinely informed and even lifesaving decisions regarding treatment options.

The next administration should pursue a two-pronged approach to help do just that. First, the administration should launch a coordinated and comprehensive patient-education and public- awareness campaign. This campaign should designate patient data and tissue rights as a national public-health priority. Second, the administration should expand provisions in the Cures 2.0 Act to ensure that healthcare providers are equally invested in and educated about these critical patient issues. These steps will accelerate a needed shift within the U.S. healthcare system towards a culture that embraces patients as active participants in their own care, improve health- data literacy across diverse patient populations, and build momentum for broader legislative change and around complex and challenging issues of health information and privacy.

Congressional briefing: Potential of fluvoxamine to counter COVID-19

There has been a surge of public interest in the drug fluvoxamine as a potential treatment for individuals with mild COVID-19, and Congressional offices are receiving many questions about the possibility of using the drug to counter COVID-19 from constituents. This brief outlines what is known to date about fluvoxamine in the context of the coronavirus pandemic in order to help both policymakers and scientists discuss this issue with those in their communities.

Fluvoxamine is a long-used drug that showed promising preliminary results in a small, well-controlled COVID-19 patient study

The generic drug fluvoxamine (also referred to by the brand name Luvox) was first synthesized in 1971, and is used to treat anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fluvoxamine blocks serotonin reuptake in the brain, but it is chemically unrelated to other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that are used to treat anxiety or depression, like fluoxetine (Prozac) or sertraline (Zoloft). Studies have demonstrated that fluvoxamine also binds a protein in mammalian cells called the sigma-1 receptor. One of this receptor’s functions is to regulate cytokine production; cytokines cause inflammation. When fluvoxamine has been used in the laboratory, it results in a dampened inflammatory response in human cells in the test tube, and protects mice from lethal septic shock, which is an out-of-control immune response to infection, causing massive inflammation that can impede blood flow to major organs, and result in organ failure. Notably, retrospective analyses have indicated that COVID-19 patients given antipsychotic drugs that target the sigma-1 receptor were less likely to require mechanical ventilation than COVID-19 patients given other antipsychotic drugs, and some drugs that bind the sigma-1 receptor also have antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in the petri dish.

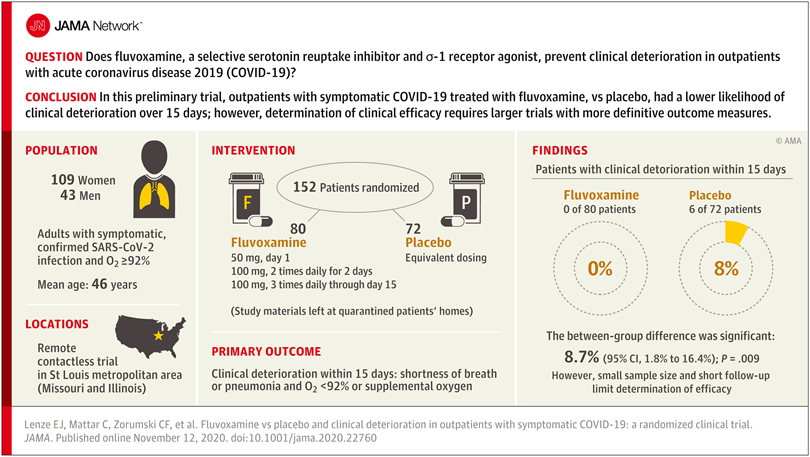

Researchers reasoned that fluvoxamine may be able to stave off the “cytokine storm” that can lead to the out-of-control inflammatory response that appears to cause severe respiratory and blood-clotting issues for some people infected with the coronavirus, and tested the drug in a pilot study to gauge whether it has potential as a treatment for COVID-19. The study was a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 152 non-hospitalized adults with mild COVID-19. Treatment of symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19 patients started within 7 days of their diagnosis. None of the 80 patients treated with fluvoxamine experienced clinical deterioration, compared to 6 of 72 patients treated with placebo who experienced both “1) shortness of breath or hospitalization for shortness of breath or pneumonia and 2) oxygen saturation less than 92%.” While this amounted to a statistically significant difference, the study serves as only preliminary evidence for the efficacy of fluvoxamine as a therapy to counter COVID-19, and a much larger clinical trial has been initiated to pursue conclusive results.

Further study of treating many more COVID-19 patients with fluvoxamine is required before the drug should be used outside of clinical trials as a therapy to counter COVID-19

While the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized design of the clinical trial does minimize bias and provide the opportunity to identify a causal relationship between treatment and patient outcome, larger randomized trials with more definitive metrics in place for assessing patients’ health status are necessary in order to reach a conclusion about whether fluvoxamine should be used to treat patients with COVID-19 outside of clinical trials. The findings of this single, small study are a launching point for larger clinical trials, and “should not be used as the basis for current treatment decisions.”

The limitations of the study include the small number of COVID-19 patients involved and the low number of patients in the placebo group whose conditions worsened – only six. And while fluvoxamine is safe, easily accessible, administered orally, and inexpensive, it may interact with other drugs, and does have some side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, increased sweating, dizziness, drowsiness, insomnia, or dry mouth.

The researchers who performed this pilot study are currently conducting a larger clinical trial to conclusively determine whether fluvoxamine is an advisable treatment for mild COVID-19. The trial is expected to be watched closely since the identification of drugs – in addition to the monoclonal antibody treatments developed by Regeneron and Eli Lilly – that could be used to reduce the likelihood of progression from mild to more severe COVID-19 would greatly improve health outcomes for people infected by the coronavirus, as well as reduce the burden on the US healthcare system.

–

This briefing document was prepared by the Federation of American Scientists along with Professor Alban Gaultier at the University of Virginia and Professor David Boulware at the University of Minnesota.

Providing High-Quality Telehealth Care for Veterans

Summary

While the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) provides telehealth services across the country, current services neglect to respond to the access challenges that constrain veterans, particularly in rural areas. Of the nearly 5 million veterans who live in rural areas, 45% lack access to reliable broadband internet and smart technology. In the absence of available or reliable internet, veterans are often forced to access telehealth services in person at VA Clinical Resource Hubs (CRHs). However, these facilities are limited in number and are typically located far from rural communities. To address digital inequities and constraints posed by infrastructure and geography, the VHA needs to create more ways for veterans to access and fully utilize telehealth. We propose that the VHA partner with federal agencies like the United States Postal Service (USPS) or United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), leveraging their infrastructure to develop telehealth hubs. We further suggest that the VHA develop and lead a federal taskforce to build critical technology infrastructure that will facilitate expansion and use of telehealth for veterans. These interventions will be vital for ensuring that veterans in rural communities have greater access to care and can not only survive but thrive.

An Evidence-based Approach to Controlling Drug Costs

Summary

Optimizing the dosing of many expensive drugs can drastically reduce both costs and toxicities. The Federal Government, state governments, employers, and individual patients could collectively save tens of billions of dollars each year by simply optimizing the dosing of the most expensive prescription drugs on the market, particularly in oncology. Optimized dosing can also improve health outcomes. The next administration should, therefore, launch an effort to control the cost of prescription drugs through an evidence-based approach to optimizing drug dosing and improving outcomes. The requisite trials pay for themselves in immediate cost savings.

Advancing Economic and Health Goals by Increasing the Use of Evidence and Data

Summary

As the United States continues to grapple with unprecedented economic, health, and social justice crises that have had a devastating and disproportionate effect on the very communities that have long struggled most, the next administration must act quickly to ensure equitable recovery. Improving economic mobility and increasing equity in communities furthest from opportunity is more urgent than ever.

The next administration must work with Congress to quickly enact a new round of recovery or stimulus legislation. State and local governments, school systems, and small businesses continue to struggle to respond to COVID-19 and the economic and learning losses that have accompanied the resulting closures. But federal resources are not unlimited and there is little time to spare – communities need positive results quickly. It is imperative, furthermore that the administration ensures that the dollars it distributes are used effectively and equitably. The best way to do so is to use existing evidence and data — about what works, for whom. and under what circumstances — to drive recovery investments.

Fortunately, the federal government has access to unprecedented evidence and data tools that can increase the speed and effectiveness of these urgent recovery and equity-building efforts. And where evidence or data do not exist, this unique moment affords an opportunity to build evidence about what does work to help communities recover and rebuild.

Thus, one of the first priorities of the next administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should be helping agencies develop their capacity to use existing evidence and data and to build evidence where it is lacking in order to advance economic mobility across the country. OMB should also support federal agency efforts to assist state and local governments to build and use local evidence that can accelerate economic growth and help communities recover from the current crises.

Specifically, OMB should issue guidance directing federal agencies to: 1) define and prioritize evidence of effectiveness in their grant programs to help identify what works, for whom, and under what circumstances to advance economic mobility post-COVID; 2) set aside 1% of discretionary funding for evidence building, including evaluations, technical assistance and capacity building; 3) support state and local governments in using recovery funding to build their own data, evidence-building and evaluation capacity to help their communities rebuild; and 4) require that findings from 2021 evidence-building activities be incorporated into strategic plans due in 2022.

A Draft Executive Order to Ensure Healthy Homes: Eliminating Lead and Other Housing Hazards

Summary

Over 23 million homes in America have significant lead paint hazards and more than 200,000 children have unsafe levels of lead in their blood. Lead poisoning causes significant decreases in math and reading scores and a host of other health problems, all of which are preventable.

The urgent need for homes that support good health has never been clearer: the COVID-19 pandemic has meant more time in our residences, bringing healthy housing to the fore as a national priority. Inadequate housing conditions—such as exposure to lead paint, radon, mold and moisture, pest infestations, structural instability, and fire hazards—cause or exacerbate asthma, allergies, poisonings, falls and injuries, cancer, cardiovascular problems and other preventable illnesses. They needlessly burden our hospitals, schools, communities, and housing finance institutions, exacerbating the housing affordability crisis. Sustainable healthy housing is essential to economic vitality, climate change mitigation, and children’s futures.

This Executive Order establishes a cabinet-level Presidential Task Force on Lead Poisoning Prevention and Healthy Housing to coordinate the nation’s response to lead paint and other housing-related diseases and injuries under the Biden administration. Led by the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, this Task Force will recommend new strategies, regulations, incentives and other actions that promise to conquer these avoidable problems. With strategic leadership and concerted action, the Task Force can eliminate childhood lead poisoning as a major public health problem and ensure that all American families have healthy homes.

Scientists take action by engaging with Congress on the promise of monoclonal antibody therapies for COVID-19

The limited science and technology (S&T) resources available to policymakers in Congress and state legislatures have compounded the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. To help meet legislators’ S&T needs, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) organized more than 60 specialists with expertise in all the different aspects of the pandemic to serve on the COVID-19 Rapid Response Task Force. In addition to providing many written briefings to Congressional and state legislative offices, members of the Task Force have so far provided three oral briefings to Congress, including one about the promise of monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies for COVID-19.

Monoclonal antibodies to counter COVID-19

Many experts believe that mAb therapies have a major role to play in protecting people from COVID-19, serving as a bridge to a vaccine, and safeguarding groups that potentially would not respond to a vaccine, for example, an aged population or immunocompromised individuals. There is certainly precedent for mAb therapies helping people survive deadly diseases; for instance, mAb therapies resulted in statistically significant survival benefits for Ebola patients.

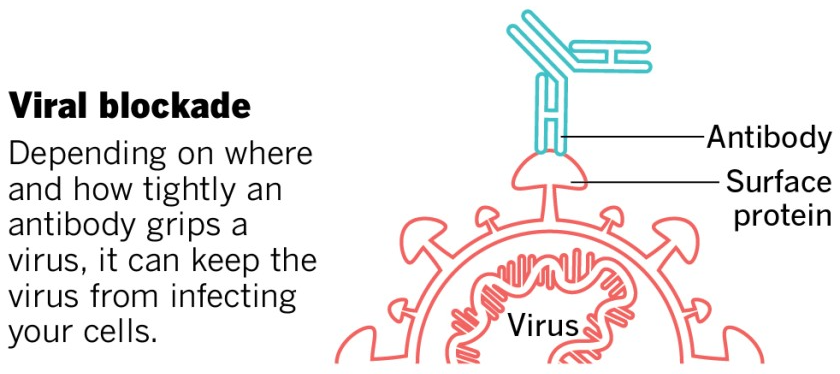

Therapeutic mAbs against COVID-19 are intended to stick to the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2, which are on the outside of the virus, and block them from being able to attach to receptor proteins on the outside of human cells, which would be needed for viral entry and infection. Most focus has been on the spike protein interaction with the human cell surface receptor ACE2, and recent work shows that the human cell surface protein Neuropilin-1 also has a role in facilitating SARS-CoV-2 entry and infectivity in some human cell types. Designing mAb therapies that interfere with either one or both of these interactions could help explore the range of efficacies of COVID-19 mAbs.

This image was adapted from the San Diego Union-Tribune.

An experimental mAb from Eli Lilly being tested in early-stage clinical trials, while not appearing to help COVID-19 patients who are hospitalized (that testing has been stopped), has shown promise for people with mild or moderate COVID-19 who receive the treatment early and who are not hospitalized, reducing viral load, symptom severity, and eventual hospitalizations. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Eli Lilly’s antibody. Under the EUA, the treatment, called bamlanivimab, is supposed to be given to patients as soon as possible after a positive coronavirus test, no more than 10 days after developing symptoms. The treatment should not be used for patients who are hospitalized. It is intended for individuals 12 and older and at risk for developing a severe form of COVID-19 or being hospitalized.

Regeneron has also developed a mAb treatment, and has, like Eli Lilly, stopped its clinical trial in hospitalized patients – in Regeneron’s case, “an independent data monitoring committee warned that the risks might outweigh the benefits for hospitalised patients on high levels of oxygen.” Like Eli Lilly’s drug, Regeneron has reported that its mAB cocktail reduces virus levels in the body and improves symptoms for individuals with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized. Regeneron has also applied to the FDA for an EUA of their mAB therapy, and overall, at least ten COVID-19 antibodies are being tested in clinical trials, with many more under development.

While EUAs can serve to get drugs to patients more rapidly than going through full FDA approval, the use of mAbs outside of clinical trials can make it more difficult to ascertain the therapies’ true effectiveness in different age groups. Furthermore, it could make it harder to enroll volunteers in future clinical trials for alternative therapies, since people may want to take a drug that appears to work, rather than risk possibly getting placebo. Authorizing a low-impact therapeutic could be counterproductive. FDA must take care to only grant EUAs for mAb therapies where the data show they are potent, and clearly delineate the circumstances in which they should be administered to help patients.

Antibodies are expensive and difficult to make, and they are administered at relatively high levels. These factors conspire to limit the number of doses that are produced. By the end of the year, Regeneron is expected to have produced up to 300,000 doses of its cocktail, and Eli Lilly greater than one million. More doses are needed; experts estimate that each day, 10,000 to 15,000 people in the US would be indicated for the drugs based on age and risk factors, even if there’s no further surge of infection.

A major challenge is that manufacturing capacity for monoclonal antibodies is limited, generally actively being used to produce treatments that are needed by patients as therapies for conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, or osteoporosis. Globally, bioreactor capacity for producing mAbs from mammalian cells is spread across 200 facilities, with a total capacity of about 1,500,000 gallons. Constructing new manufacturing capacity requires years, with different types of facilities taking anywhere from 18 months to 7.5 years to come online. Bringing inactive facilities back online is a possibility, but how available such facilities are, and what would be needed to update them for operation, is unclear, and unlikely to happen in the near future. So, COVID-19 mAb manufacturing will need to rely on facilities either in use or in development, at least in the near-term.

Possible roles for government include helping to coordinate the construction of new mAb manufacturing capacity, or the repurposing of existing sites that could serve as bioreactors. Non-traditional mammalian cell lines could be tested to see which produce the highest levels of these mAbs to make the best use of the bioreactor capacity. Also, there are techniques for producing mAb therapies in bacterial or fungal (like brewer’s yeast) cells, in addition to mammalian cells, which could take advantage of existing capacity for microbial fermentation. And regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and FDA could help expedite actions like repurposing bioreactor sites or deploying new bioproduction technologies by prioritizing the evaluation of these activities without harming the environment or sacrificing drug safety or efficacy.

Government could also assist with coordination between companies, providing a framework and forum for sharing information about or partnering on manufacturing capacity, or discussing approaches to COVID-19 mAb design that may have already been attempted and that did not pan out. This coordination could even extend to facilitating international collaborations, as COVID-19 mAb development efforts are taking place in countries all around the globe.

Considering COVID-19 is a deadly disease that can also have long-term health impacts for those who survive, the development and deployment of mAb therapies that can be administered soon after infection is detected and reduce the severity of disease are expected to contribute to countering the health effects of the pandemic.

Briefers

The experts who briefed Congress were Megan Coffee, MD/PhD, Clinical Assistant Professor at New York University; Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, Professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and lead of the Coronavirus Immunotherapy Consortium; Jill Horowitz, PhD, Executive Director of the Strategic Operations Laboratory of Molecular Immunology at Rockefeller University; John Cumbers, PhD, CEO of SynBioBeta; Eric Hobbs, PhD, CEO of Berkeley Lights; Jake Glanville, PhD, CEO of Distributed Bio; Mike Fisher, PhD, Senior Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists; and Ali Nouri, PhD, President of the Federation of American Scientists.For more information about FAS’ work with Congress, visit our Congressional Science Policy Initiative website.

Categories: Public Health

Preventing the Next Pandemics: An Upstream Approach to Novel National Security Threats

COVID-19 is estimated to cost the global economy between $8 to 15 trillion USD1, but it is not the first such outbreak, nor will it be the last. Since the 1970’s, 70% of emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) have been at the human-wildlife boundary2, with new infectious diseases emerging at a faster rate than ever before. Further, a common, defining feature of emerging infectious diseases is that they are triggered by anthropogenic changes to the environment. As natural environments degrade (specifically, due to climate change, loss of biodiversity and fragmentation of habitats, or invasive species), they are more likely to harbor infectious diseases and their vectors (animals or plants that transmit a pathogen)2.

This memo proposes a series of actions to shift the focus of our existing EID strategies from merely reacting to disease outbreaks – which is economically devastating – to detecting, addressing, and mitigating the major upstream factors that contribute to the emergence of such diseases prior to an outbreak, and would come at orders of magnitude lower cost. Recent analysis of the exponentially rising economic damages from increasing rates of zoonotic disease emergence suggests that strategies to mitigate pandemics would provide a 250:1 to 700:1 return on investment. Even small reductions in the estimated costs of a future pandemic would be substantial. This approach would have greater success at a much lower cost in reducing the impacts of EIDs.

The next administration should

- launch a strategy aimed at strengthening biosurveillance systems at home and abroad through a global viral weather system for spillover, including harnessing technology and data science to create predictive risk systems;

- eliminate existing barriers in international development and foreign policy between food security, global health, and environmental sustainability by establishing a coordinator for planetary health;

- address and alter the incentive structures that facilitate spillover, and create new incentives for investments to reduce the risk for spillover through institutions like the Development Finance Corporation; and

- through creating the world’s first climate & biodiversity neutral development agency, to ensure that our development investments aren’t facilitating spillover risks.

Challenge and Opportunity

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic represents the greatest global public health crisis of this generation and, potentially, since the pandemic influenza outbreak of 1918. But it is not the only new pathogen to have threatened humanity in that time, nor will it be the last. Scores of infectious diseases threaten humankind: both familiar ones like malaria, tuberculosis, and neglected tropical diseases, and emerging viruses, fungal, and bacterial infections like Ebola, H5N1 avian flu, Zika, severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Increasingly, emerging infectious diseases (EIDs) are zoonotic: 60% are shared between wildlife and humans3. Today, the frequency of epidemics is increasing, driven by surging populations, our degradation debt owed to the planet and climate, wildlife trafficking, and globalized trade and travel.

As we have seen with COVID-19, in a thoroughly interconnected world, those of us in developed economies cannot afford to ignore the developing world if we are concerned about disease outbreaks. The failure to address Covid-19 everywhere affects our ability to address it anywhere. Not enough is known about the trajectory of the transmission of COVID-19 in the Global South. Many developing countries, especially in rural communities, are limited in their ability to test and isolate patients due to under-funded healthcare systems that lack medical staff, training, laboratories, reagents, equipment, and trained personnel. They lack the resources and bio-surveillance capacity to identify spillover events, and outbreaks even with large mortality may go undiagnosed when their symptoms mimic other diseases.1 Moreover, EIDs can exacerbate chaos in failed and failing states, and failed states make ready homes for pandemics.4 COVID-19 in fact may have moved between 88-115 million people back into extreme poverty, and potentially 150 million by 2021, setting back efforts to end extreme poverty by 3 years.5 This is why the response to COVID-19, and the next pandemics, are not just health problems, but need be framed within a larger development and conservation context that requires investments in restructuring how we address the wicked problems facing our country and our planet.

Accordingly, as we respond to this outbreak, it is even more important to think about how we prevent the next one. The U.S. has invested significant resources to prepare for, monitor, and respond to outbreaks of existing infectious diseases. Although this investment has been insufficient as we have seen in COVID-19, there is a bigger issue: How do we avoid the next 10 pandemics? These “downstream” responses fail to address the origination of novel emerging infectious diseases, i.e. how such diseases initially arise, or the factors that accelerate their spread. We need to focus on factors that greatly contribute to disease emergence: our food systems & supply chains, environmental degradation, climate change, and the movement and trade of wildlife and wildlife products.

Much of the world’s population lives in close proximity to animals and natural environments; such proximity translates into greater disease risks. More than half of the 1,407 recognized infectious diseases are shared between humans and wildlife (“zoonotic”); such zoonotic pathogens are twice as likely to be emerging or reemerging, than are nonzoonotic pathogens. Since the 1970’s, 75% of EIDs have been at the human-wildlife boundary, with new infectious diseases emerging at a faster rate than ever before.6 Further, a common, defining feature of emerging infectious diseases is that they are triggered by anthropogenic changes to the environment. As natural environments degrade (specifically, due to climate change, loss of biodiversity and fragmentation of habitats, or invasive species), they are more likely to harbor infectious diseases and their vectors (animals or plants that transmit a pathogen). Understanding and addressing how such environmental changes may affect the spread of disease allows us to mitigate or even prevent outbreaks in the future.

It would be substantially more cost effective, efficient, and safer to prevent these diseases from initial emergence and spread. According to Dobson et al, the estimated cost difference of prevention would be $22.0 to $31.2 billion, compared to the expected costs of COVID-19 of $8.1 to $15.8 trillion, ranging from a 250:1 to 700:1 difference of costs. There are additional ancillary benefits to these upstream approaches, which include ecosystem services and reduced CO2 emissions.

COVID-19 presents us with an unprecedented opportunity to create a world where we anticipate, plan for, and mitigate pandemics before they happen, and even prevent them from emergence. We can address the challenge of EIDs by building the capacity and infrastructure needed to prevent future outbreaks and through addressing the root causes of EIDs. This requires us eliminate the barriers that separate global health programming from investments that address the root causes of environmental degradation, food insecurity, public health, and economic insecurity. It is also an extraordinary opportunity to take a problem-oriented approach to solving conservation & development problems, rather than a disciplinary one, and think about how we create new pathways for industrialization that meet the exigencies of climate change and sustainability.

Climate Change

Climate change expands the range and impact of pathogens, facilitating the spread of EIDs. Warmer temperatures enable pathogens and their vectors to survive and sometimes thrive in habitats previously outside of their tolerance range. It also serves to change weather patterns (like storms or rainfall) that lead to more standing water, and increase the population of mosquitos or other vectors. Climate change may also alter the range and fitness of host predators or competitors that would have limited spread of vectors under previous conditions. Vectors may also be active for longer periods of time during the day (e.g., mosquitos may have more opportunities to transmit a disease because they have more times to bite). Tropical diseases such as malaria, cholera, yellow fever, now reach previously unexposed human populations in South America, Central Africa, and Asia due to the spread of their vectors to new regions. Dengue is expected to reach New York and Washington DC by 2080.

Environmental Degradation and Disease Risk

The destruction and degradation of natural habitats and the stress and defaunation of species communities within them, facilitates the emergence of infectious diseases by increasing the opportunities for disease spread and spillover.

First, reduced species diversity increases the relative commonness of those species that incubate, carry, and help spread a pathogen (“reservoirs”), increasing disease prevalence. Further, predators are the first to disappear after habitat degradation; the lack of a “regulatory” agent leads to an increase in reservoirs, increasing opportunities for transmission as with Lyme disease in the Eastern U.S. Lower resources could mean less competitors, another regulatory agent. Environmental degradation may also increase shedding rates by stressing animals, encouraging the spread of the disease. Deforestation and degradation of habitats may also facilitate the spread of infectious disease by increasing habitat that favors disease vectors, such as mosquitos (rice paddies around forest edges), or edge habitat that favors invasions by invasive species.

Finally, changes in landscape geometry and makeup, coupled with changes in density in domesticated and wild species, may draw together formerly isolated populations, increasing spillover risks to humans and domesticated animals from wildlife populations, and vice versa. Tropical forest edges create spillover opportunities for novel human viruses, as humans and their livestock are more likely to come into contact with wildlife when more than 25% of the original forest cover is lost.7 Environmental degradation, driven by forestry, mining, and agriculture, increases opportunities for hunting wildlife, and the potential for spillover.

Invasive Species, Wildlife Trade, Pet Trade, and Food Systems

The invasion of foreign species (pathogens, vectors, and reservoirs) into novel habitats also spreads infectious disease. Such introductions may happen due to increasing globalization of industry, trade, and tourism; through the pet trade (as what happened with the U.S. outbreak of Monkeypox), through legal or illegal trade in wildlife and wildlife products; or through habitat changes that facilitate invasions by alien plants or animals. Invasive alien species may carry disease into populations previously unexposed to those pathogens. Invasive species may also destroy native species or their food supplies, creating an unbalanced ecosystem more vulnerable to disease. As SARS-COV-2 has shown us, wildlife trade is especially prone to spillover, as the capture, handling, slaughter, and ingestion of wildlife can lead to the transfer of a pathogen from wildlife to humans. Ebola is thought to have arisen due to bushmeat hunting of bats and nonhuman primates; HIV is thought to have arisen due to bushmeat hunting of chimpanzees; MERS is thought to have arisen due to animal husbandry (camels).

Plan of Action

Currently, U.S. policies to combat and address EIDs are focused on costly responses to individual outbreaks, rather than reducing the chance for an outbreak to occur. Artificial barriers between public health responses, food security, animal health, biodiversity conservation, and national security also exacerbate the problem. On the international level, there is a total failure to standardize disease data, link it with environmental change, and assess risks despite scientific evidence linking disease emergence and environmental change. Confronting EIDs more effectively and efficiently requires a multifaceted and multidisciplinary approach. To better understand and address the threat posed by EIDs and develop more effective responses to this threat, this memo recommends the following steps:

Establish a biosurveillance system in the most biodiverse places

A first line of defense against emerging zoonotic viruses is dependent on countries having adequate capacities for monitoring and reducing spillover of viruses from wildlife to people (either directly or through intermediate animals such as livestock). Existing biosurveillance efforts are typically not sufficiently robust, as evidenced most-recently by the spillover of SARS-CoV-2 from animals to people in Wuhan, China.

Through massively better biosurveillance of targeted pathogens through new technologies, including low cost molecular testing to be able to understand opportunities for spillover in the United States, as well as in the Amazon Basin, Wallacea, and the Congo Basin, we can establish a global, integrated monitoring network that forms the basis of an actionable biosurveillance system. Key will be increasing world class lab capacity in the places where spillover is more likely to happen and development of new low cost technologies that can help identify new pathogens, and their reservoirs in situ. With this networked of networked devices, patterns of emergence and spread can also be monitored in near real-time, producing transformative data on the epidemiological and ecological progression of novel pathogens. However, this will require setting up a modern surveillance network in partnership with other health organizations with a large foot print on the ground. These include the CDC, FHI360, WCS, Veterinarians without Borders, and the World Health Organization. It will also require the US to create a Field ParaVets Program, a rapid training program for rapid response and paraveterinarian specialists that would be focused on one-health surveillance and outbreak detection.

Utilizing big data, machine learning, and models from epidemiology, ecology, and evolution, we can begin to develop the integrated frameworks and analytical capacity that will enable a global forecasting system for future pandemics and EIDs. Much like the Global Weather Services enterprise, we can create a system that provides information and services to front-line actors, governments, health agencies, civil society, and front-line communities that enables them to anticipate and respond to the emergence of new diseases. Furthermore, because of the integrated nature of such a Global Biosurveillance System, capitalizing on the ecological and evolutionary understanding described above, we can create actionable insights that will allow conservationists, public health officials, food system agents, and others to move upstream from the emergence of these novel pathogens to turn off the underlying drivers.

Implementation

Creating a Global Viral Intelligence Service for Predicting Pathogen Spillovers. We need a global surveillance network for emerging infectious diseases to gather information on the incidence of disease in populations of wildlife, humans, and domesticated animals, and agriculture, at every stage of the trade supply chain beginning with free-ranging populations and extending to wildlife farms, confiscated animals being smuggled, and animals legally being shipped at points of export, and create adaptive “weather” maps of the risks of disease transmission. This service, would be based within the NIH, and work closely with the Centers for Disease Control, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, and the USGS National Wildlife Health Center

Improving Monitoring and Prevention Internationally. The US must take a leadership role to strengthen efforts by UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), UNDP, UNEP, and the World Health Organization, to develop a systematic approach for early detection and rapid response to identify and control emerging infectious disease of human, wildlife, and domesticated animals, including delineating risks from wildlife trade, environmental degradation, and climate change. Through USAID, in partnership with the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the Navy Medical Research Centers in Egypt, Lima, and Singapore, the US would develop new funding and technical assistant programs for building disease monitoring lab activity and personnel, building on USAID’s IDENTIFY program, previous programs including PREDICT, PREVENT, IDENTIFY, RESPOND, and DTRA’s Cooperative Biological Engagement Program.

Expansion of Existing Authorities to Defend our Borders. The new administration should expand the mission of APHIS to address not only disease issues that affect agricultural animals but also those associated with zoonotic and wildlife diseases, and increased focus on disease prevention, preparedness, detection, and early response activities. We may give CDC the authority to use pre-import screening, such as a process that assesses disease risk by species and country and determines allowable imports on the basis of that assessment. We may also amend the Lacey Act to strengthen the USFWS’s ability to identify, designate and stop injurious species, including dangerous pathogens from entering the United States, and from moving in interstate commerce if and when they arrive here.

Breaking down barriers between food security, global health, and sustainability

It is clear that how we may address pandemics requires us to break down the barriers – such as the health accounts in USAID – that limit opportunities to take a transdisciplinary approach to how we may address pandemics. Emerging pathogens are not limited to human health or wildlife, but cross over into the disruptive pests and pathogens that address the crops we grow, the food we store, and ecosystems we value. Our solutions to EIDs require us to think more broadly than global health, but think about health systems, food safety and security, wildlife trade, and environmental change.

Implementation

Address the Drivers of Pandemic Emergence. Work with Congress to allow for greater multisectoral programming within USAID to address the underlying drivers of extinction. Proactive efforts that minimize risk of emerging diseases are less costly than the economic and mortality costs of responding to these pathogens once they have emerged. Harnessing intelligence from the Global Viral Intelligence Service, the US should also fund programs to mitigate the underlying factors that facilitate disease emergence, including addressing food systems and global production of feed, food, materials, and their supply chains, and environmental degradation. This includes looking at how we may reduce risk through (1) protecting habitats, conserving biodiversity, reducing deforestation, restoring degraded habitat; (2) prioritizing international transdisciplinary research collaborations under the Ecohealth, OneHealth, and Planetary Health Frameworks; and (3) using ecological interventions to reduce human disease burdens and pandemic risk through experimental management and conservation.

Encourage a whole of government approach through the leadership of the National Security Council. The National Security Council should coordinate both international and domestic approaches to take a multi-disciplinary approach to addressing the upstream factors of pandemics, working in consultation with PCAST, NSTC, CEQ, OSTP, and OMB, and through an interagency process with representation from State, USAID, DFC, DOD, Treasury, HHS, NOAA, NASA, USGS, ODNI, and other relevant federal agencies, through an interagency working group.

Changing the incentives that drive spillover

Regardless of the exact determinants of the origin of COVID-19, this pandemic is primarily due to human behavior. Wildlife wet markets bring together an array of wild animals, in stressful and confined conditions, that would not normally occur. This creates an environment conducive to the spread of disease. Consumption of these wild animals (such as bats, pangolins, and even primates) puts human health at risk by providing an opportunity for the virus to potentially spillover from non-human animals to humans. We need to change the incentives for human behavior, and facilitate that change through modernization of the food system, animal husbandry, and supply chains, and increasing the sustainability of systems to reduce the demand for wildlife products that produce pandemics and decimate wild populations.

Creating new technological systems to better protect the forests tied to direct payments for conservation systems & monitoring (whose value is based on spillover risks & biodiversity value) to change behavior for those at greatest risk of spillover, and who have few other economic choices. Some early attempts exist to change behavior around wildlife trade, such as campaigns in China to reduce the consumption of shark fin soup, that can serve as models for ways to leverage new technologies and behavioral science approaches (gamification, peer networks, positive and negative reinforcement, etc.) to reduce demand for wildlife products. This, coupled with market signals that incentivize proper behavior could produce significant benefit.

Implementation

End Implicit and Explicit Subsidies that Drive Spillover at home and abroad. Many threats to planetary health, including emerging infectious diseases, are unwittingly subsidized and facilitated by the government. These subsidies include those in water use, energy, agriculture, transportation, fisheries, land management, and trade. Ending subsidies domestically may not only support planetary health, but free up revenue to the program. Internationally, subsidies violate the underlying principles of global trade through the World Trade Organization and allow for countervailing measures. Further, parties to the WTO may implement trade related measures at protecting the environment. These would serve to benefit the sustainability of US industry and make our domestic and better regulated products more competitive.

Create new Financial Innovations & Encouraging Investment for Preventing Pandemics. Financial innovations are a powerful class of behavioral incentives. We should consider innovations such as Advanced Market Commitments, Direct Payments for Conservation, Social Impact Bonds & Direct Payments, Franchise Models, and Nutrient and Carbon Trading, coupled with mechanisms such as the Development Credit Authority within the new Development Finance Institution which guarantees up to 50% of “first loss” of an investment to encourage the development of new capital to support Planetary Health and addressing emerging infectious diseases. The SEC could also require companies to report measures on their environmental sustainability, and potential risk from environmental degradation, climate change or pollution on their operations.

Creating a climate & biodiversity neutral development agency

Climate change and biodiversity degradation will be a major driver of the spread of EIDs. To mitigate what is an increasing threat to human security, USAID needs to ensure that its entire portfolio of activities, do not on average, worsen climate change or undermine biodiversity loss. This requires us to think beyond just funding sporadic climate and conservation programs, but thinking about the systematic impact of the Agency’s activities on climate change, and ensuring that US development investments are generating a net impact of zero emissions of the greenhouse gases that cause global warming, and are not driving species defaunation and extinction. Such an approach supports the SDGs, and will allow for countries to find new pathways to industrialization and development. It will enable the Agency to stop contributing to the very problems it is trying to solve such as weather-related humanitarian crises, livelihood re-engineering due to decreasing water levels, and conflict over arable land.

Climate & biodiversity neutrality does not detract from other development goals, such as economic growth. While the United States should invest heavily in encouraging sustainable economic growth –and it is in the environment’s interest to do so — it is imperative that we act in a way that does not worsen the effects of climate change or the extinction crisis. Future economic growth must work to reduce rather than expand emissions of greenhouse gases. Working towards climate & biodiversity neutrality would benefit the people assisted by USAID, as well as the environment. Certain USAID programs are inherently emissions-intensive, such as responding to disasters or building roads. Achieving climate & biodiversity neutrality across the entire basket of USAID foreign assistance activities allows development activities in one country that reduce emissions (such as forestry, biodiversity conservation, and renewable energy) to balance activities in other countries that increase emissions (humanitarian aid missions, roadbuilding). USAID can become, once again, the most forward-thinking development agency, shining as an innovative example among other donor organizations throughout the world.

Implementation

Create an annual estimate, through the annual budget process, of the approximate carbon impact of USAID programs, and create an office within the Policy Bureau to carry out this analysis. This office will lead a Climate Neutral Task Force (CNTF), with representatives from each Washington Bureau and, initially, those Missions that choose to participate in a comprehensive assessment of both their programs and operations. Bureaus will be represented by environment officers and experts in the key sectors — infrastructure & engineering, energy, agriculture, water, and natural resources, and our own operational management. One year appears a reasonable estimate for how long it would take for the CNTF to accomplish the work described in the proposal. We recommend undertaking the emissions assessment process in several self-selected, pilot Missions, in the first year, and then expand to the whole Agency in the next year.

Improving Federal Management of Wildlife Movement and Emerging Infectious Disease

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed systematic vulnerabilities in the way that wildlife movement and emerging infectious diseases are managed at national and international scales. The next administration should take three key steps to address these vulnerabilities in the United States. First, the White House should create a “Task Force on the Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases”. This Task Force would convene agencies with oversight over animal imports, identify necessary policy actions, determine priority research areas, and coordinate a national response strategy. Second, the next president should work with Congress to pass a bill strengthening live-animal import regulations. Third, U.S. agencies should coordinate with international organizations to address global movement of infectious diseases of animals. Together, these actions would reduce the risk of emerging infectious diseases entering the United States, offer greater protection to citizens from zoonotic diseases, and protect American biodiversity from losses due to wildlife diseases.

Challenge and Opportunity

More than 60% of emerging infectious diseases in humans first originate in animals. More than 70% of these come from wild animals. HIV, for instance, jumped to human hosts from primates in Africa. MERS spread to humans from camels in the Middle East. Of present salience, experts believe that the virus that causes COVID-19 originated from wild animals in China (probably bats).

The risk of animal-to-human “spillover”—and the global spread of zoonotic diseases—increases when wildlife are traded and imported around the world (e.g., for food, traditional medicines, display, pets, etc.). The global spread of COVID-19 has drawn attention to problems such as lack of disease surveillance in wild animal populations and lack of disease testing in many live animals at international borders. International wildlife-trade laws do not account for public-health risks of wildlife trade. These laws also do not require collection of data on zoonotic diseases (i.e., diseases caused by germs that spread between animals and people): data that could help prevent the next pandemic. These problems are exacerbated by accelerating rates of habitat conversion and biodiversity loss coupled with increased volume and speed of international commerce.

The United States is especially susceptible to emerging zoonotic diseases because it is the world’s largest importer6 of legally traded wild animals, yet lacks domestic regulations requiring most imported live animals to be tested for diseases, pathogens, or parasites. Gaps in U.S. statutory and regulatory frameworks governing live-animal imports increase disease risks for humans while also threatening our country’s biodiversity and natural resources. In the United States, four agencies oversee some aspect of live-animal imports—but this oversight is far from comprehensive. The Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) is responsible for assessing the risk of diseases in agricultural imports, but not wildlife species. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) oversees imports of only primates and some species of rodents, bats, or birds known to spread zoonotic diseases. The Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) is responsible for regulating imports of all wildlife (and imposes stricter standards on species previously identified as injurious), but its mandate does not cover infectious diseases or parasites. The upshot is that imports of most wildlife species to the United States are not assessed for disease risk by any agency. Most disease agents that infect wildlife (except for a small number of known zoonotic diseases) are not monitored by any agency either.

Plan of Action

The next administration should take three key steps to address systematic vulnerabilities in the way that wildlife movement and emerging infectious diseases are managed in the United States and around the world.

Create a White House Task Force on the Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

This Task Force would convene agencies with oversight over animal imports (including the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Department of the Interior (DOI), and CDC) and those supporting research (NSF, NIH) or international assistance (U.S. Department of State, USAID) to determine global research priorities on wildlife disease, and facilitate international cooperation on mechanisms to reduce demand as well as disease risk in the live animal trade. The task-force would use the One Health concept that links human health with animal health and environmental health, and that applies a comprehensive approach to understanding the drivers of disease emergence, the spread of disease, and the impacts on human health.

Work with Congress to pass a bill strengthening live-animal import regulations.

This bill would build on past legislation (e.g., H.R. 6362/S. 3210;11 H.R. 3771/S. 1903;12 and S. 375913) related to wildlife disease. The bill should:

- Reduce risk of zoonotic disease introduction to the United States by increasing surveillance of live-animal imports at U.S. borders. Specifically, Congress should give APHIS the authority to use pre-import screening, such as a process that assesses disease risk by species and country and determines allowable imports on the basis of that assessment. Congress should also expand the mission of APHIS to address not only disease issues that affect agricultural animals but also disease issues associated with zoonotic and wildlife diseases.

- Amend the Lacey Act to strengthen the FWS’s ability to identify, designate, and stop injurious species (including dangerous pathogens) from entering the United States, and from moving via interstate commerce if and when they do enter. Specifically, the Lacey Act should be amended to grant the FWS authority over emergency listing (i.e. one that is accelerated and bypasses the notice and public comment process); authority to list human and wildlife pathogens as injurious species; and authority to regulate interstate commerce in listed injurious species.

- Expand efforts to control illegal wildlife trade. President Obama’s July 2013 Executive Order on Combating Wildlife Trafficking resulted in the development of a holistic national strategy for tackling the entire trade chain of wildlife trafficking. The next administration should strive to implement elements of this strategy that have not yet been implemented, and to build on elements that have. This could include increasing the FWS’s enforcement capacity, strengthening measures to prevent and deter wildlife trafficking, increasing the severity of penalties for wildlife crime, and taking steps to reduce demand (media campaigns, behavior change) for imported wildlife.

Coordinate internationally to address diverse aspects of wildlife movement and emerging infectious diseases.

The next administration should direct USDA (primarily APHIS) and the FWS to lead the following efforts:

- Amend the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) treaty and accompanying resolutions to (i) consider disease risk as a factor in regulating wildlife imports and exports, and (ii) broaden the scope of CITES in tackling domestic markets.

- Strengthen efforts by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) to develop a systematic approach for early detection of (and rapid responses to) emerging infectious diseases of human, wildlife, and domesticated animals.

- Expand OIE’s ambit from simply assessing disease risk in livestock trade to one in which OIE works with CITES and country-based labs to expand disease surveillance in all live-animal trade, including by conducting tests. OIE should establish a publicly accessible, centralized, and curated system for monitoring the global incidence and spread of wildlife pathogens in order to facilitate early detection of disease emergence and to document disease spread. Such a system could be modeled on GISAID or EpiFlu.

Conclusion

Regulatory gaps put Americans at risk of exposure to emerging infectious disease from unregulated and under-regulated imports of wildlife. The next administration should address these gaps by creating a White House task force, strengthening live-animal import regulations, and coordinating with international institutions to reduce the global movement of emerging infectious diseases. The result would be a nation that is healthier and safer—for humans and animals alike.

Adopting an Open-Source Approach to Pharmaceutical Research and Development

The U.S. pharmaceutical industry conducts over half the world’s research and development (R&D) in pharmaceuticals and accounts for well over $1 trillion in economic output annually. Yet despite the industry’s massive size, there are still no approved therapies for approximately 95% of human diseases—diseases that affect hundreds of millions in the United States and around the world. The disparity between industry inputs and societally valuable outputs can be attributed to two key market failures. First, many medicines and vaccines have high public value but low commercial potential. Most diseases are either rare (afflicting few), rapidly treated (e.g., by antibiotics), and/or predominantly affect the global poor. Therapies for such diseases therefore generate limited revenue streams for pharmaceutical companies. Second, the knowledge required to make many high-value drugs is either underdeveloped or under-shared. Proprietary considerations may prevent holders of key pieces of knowledge from exchanging and integrating information.

To address these market failures and accelerate progress on addressing the overwhelming majority of human diseases, the next administration should launch a new program that takes an open-source approach to pharmaceutical R&D. Just as open-source software has proven a valuable complement to the proprietary systems developed by computer giants, a similar open source approach to pharmaceutical R&D would complement the efforts and activities of the for-profit pharmaceutical sector. An open-source approach to pharmaceutical R&D will provide access to the totality of human knowledge and scientific expertise, enabling the nation to work quickly and cooperatively to generate low-cost advances in areas of great health need.

Challenge and Opportunity

Approximately 95% of human diseases (~9,500 in number) lack any approved therapies. At the current rate of discovery, it would take 2,000 years to find therapies for all known human diseases. The result is that hundreds of millions of people in the United States and around the world lack medicines and vaccines that are essential to a healthy life.

Simply put, the status quo with respect to drug development has failed. The pharmaceutical industry expends huge amounts of money—often funded with taxpayer dollars—to develop and procure medicines and vaccines, straining national and personal budgets. Moreover, our legacy system of pharmaceutical R&D is unacceptably slow. It now takes 10–20 years for the pharmaceutical industry to develop a single new medicine or vaccine. Pharmaceutical R&D efficiency is declining exponentially: Moore’s Law in reverse. Finally, investment by the existing pharmaceutical industry is driven by profit potential, not societal need. Hence, diseases that afflict many but offer limited revenue streams continue to remain neglected.