Enhanced Household Air Conditioning Access Data for More Targeted Federal Support Against Extreme Heat

While access to cooling is the most protective factor against extreme heat events, the U.S. Census lacks granular, residential data to determine who has access to air conditioning (AC). The addition of a question about household access to working AC to the Census American Community Survey, a nationally representative survey on the social, economic, housing, and demographic characteristics of the population, would have life-saving impacts.

This is especially essential as the U.S. is experiencing more frequent and intense extreme heat events, and extreme heat now kills more people than all other weather-related hazards. Many vulnerable demographics — including people who are elderly, low-income, African-American, socially isolated, as well as those with preexisting health conditions— are exposed to high temperatures within their homes.

Better data on working AC infrastructure in American homes would improve how the federal government and its state and local partners target local social services and interventions, such as emergency responder deployment during high-heat events, as well as distribute federal assistance funds, such as the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and funding from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) along with the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL).

Challenge and Opportunity

In 2019, the U.S. Census Bureau acknowledged the danger of heat by issuing the Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat. The CRE for Heat is a measure that combines 10 questions from the existing American Community Survey questions. The questions ask about:

- Financial hardship

- Older residents living alone

- Crowding

- Whether the home is a mobile home, boat, or recreational vehicle

- Employment status for those under 65 years old

- Whether a resident has a disability

- Whether a resident has health insurance

- Access to a vehicle

- Connection via broadband internet access

- Communication barriers

However, the CRE for Heat lacks a question about air conditioning, the most important protective factor. Indoor temperature regulation is essential for mitigating heat illness and death on extremely hot days – temperatures above 86°F indoors can easily become dangerous and deadly.

Currently, the best information on residential AC is provided by the biennial American Housing Survey (AHS). In 2019, the AHS reported that 8.8% (11.6 million households) of all U.S. housing units have no form of AC. However, this information has three significant weaknesses. First, the American Housing Survey is based on 2,000 homes sampled across a metropolitan area. The sampling process generates an average across high-, medium-, and low-income residents; therefore, it overestimates the presence of AC in lower-income households. American households with higher incomes are more likely to have access to AC: 92.2% of households with incomes greater than $100,000 have some form of AC, compared with 88.9% of households with incomes less than $30,000. Second, lower-income households may have broken AC systems or units and lack money for repairs, skewing collected data. Third, the AHS fails to consider how poverty constrains electricity consumption. Many lower-income households reduce or abstain from using their AC in fear of costly electricity bills that trigger shutoffs. For instance, a 2022 report found that nearly 20% of households earning less than $25,000 reported keeping their indoor temperatures at levels that felt unsafe for several months of the year. These three weaknesses of the AHS data underscore the need for fine-grained information on who has access to working AC, especially in lower-income households.

The U.S. Census American Community Survey (ACS), on the other hand, samples 3.5 million addresses every year in a nationally representative annual survey. The ACS asks about housing characteristics, costs, and conditions (including heating) but not about AC nationwide. The equivalent survey administered in the four Island Areas of Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and American Samoa — known as the “Island Areas Census” — included an AC question until 2010. This is an important precedent for adding a similar question to all Census surveys and should expedite the process. However, adding the term “working” (or a similar word) to the air-conditioning question would enhance its ability to capture low-income homes with broken systems as well as households that cannot use their existing AC due to energy insecurity.

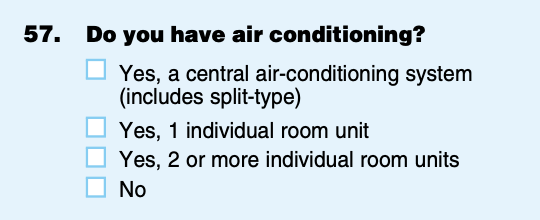

Former question on air-conditioning in the American Community Survey for U.S. Island Areas

Better Information for Better Distribution of LIHEAP and WAP Funding

In addition to helping emergency responders, city planners, and public health departments, information collected on the presence of working AC could help ensure that the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Low Income Heat Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) and Department of Energy’s (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) serve the most vulnerable residents.

LIHEAP, administered by the Office of Community Services (OCS) within the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), is designed to “assist low-income households, particularly those in the lowest incomes, that pay a high proportion of household income for home energy, primarily in meeting their home energy needs.” LIHEAP is a targeted block grant program whereby states distribute their funds across three programs that subsidize home energy heating or cooling costs; fund payment in crises; and support home weatherization (limited to 15% of funds unless a state requests a waiver to increase their percentage to 25%). The largest proportion of the funds subsidizes lower-income, vulnerable residents’ energy spending. While LIHEAP is an important federal program that impacted 7.1 million American households in 2023, only approximately 20% of eligible households received LIHEAP assistance, and the program is currently facing budget shortfalls of $2 billion.

By expanding cooling assistance, LIHEAP is being asked to do more with less: 24 of 50 states now include cooling assistance, and 9.8% of funds subsidized cooling costs. As extreme heat events become more frequent and severe and households become more energy insecure in the face of rising energy prices, more states will need to expand cooling assistance programs. Data on where households are most vulnerable — that is, those households without working AC or the financial ability to operate their AC — would enable targeted distribution of federal funds. Therefore, adding a Census question on household access to working AC would provide critical information to ensure LIHEAP funds serve the most vulnerable households.

Unlike LIHEAP, WAP’s sole focus is weatherization. Many weatherization improvements that help in cold weather also improve indoor thermal comfort during warm summer months. These improvements include fixing broken AC; adding insulation in walls, attics, and crawlspaces; and replacing leaky, inoperable windows. Compared to LIHEAP, WAP serves a much smaller number of homes — 35,000 homes annually versus LIHEAP’s 7.1 million (as of FY2023). Knowing the number of individual households in a census tract in need of investments in heat resilience adaptation and air-conditioning would enable much more targeted delivery of limited federal resources. Further, DOE can use this information to predict future grid demand and enhance necessary resilience measures for hotter summers.

Plan of Action

To save lives in the face of growing extreme heat, the Census should add a question about working AC to the American Community Survey. This could be executed as follows:

Recommendation 1. The Office of Community Services in the Administration for Children and Families (OCS ACF) requests the addition of a question about access to working AC at the census tract level to the American Community Survey. This would directly aid the LIHEAP program’s mandate to identify and serve vulnerable individuals, and benefit other programs like DOE’s WAP as well as programs authorized by the IRA and BIL.

Recommendation 2. Legal staff in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Census Bureau review the proposal to determine whether it meets legislative requirements.

Recommendation 3. After a successful legal review, OMB and the Census Bureau, in consultation with the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy Subcommittee for the American Community Survey, determine whether the request merits consideration.

Recommendation 4. Subject matter experts across relevant federal government programs (i.e. LIHEAP and WAP) and external institutions (housing experts, extreme heat experts, social vulnerability experts) identify ways to ask the question. The Census Bureau conducts interviews to determine which wording produces the most accurate results. Because a similar question (but lacking the term “working”) is used on the American Community Survey for Island Areas, this process may be expedited. A potential example of the new question is below:

Do you have working air air-conditioning?

- Yes, a central air conditioning system (includes split-type)

- Yes, 1 individual room unit

- Yes, 2 or more individual room units

- No, my air conditioning system is non-functional or broken

- No, I cannot afford to run my air-conditioning system

- No, I do not have any air-conditioning system

Recommendation 5. The Census Bureau solicits public comment on the question and request OMB’s approval for field testing.

Recommendation 6. The Census Bureau and ACF OCS review the results and decide whether to recommend adding the new survey question. Through the Federal Register Notice, the Census Bureau solicits public comment. Public comments inform the final decision that is made in consultation with the OMB and the Interagency Council on Statistical Policy Subcommittee on the American Community Survey.

Recommendation 7. If approved by OMB, the Census Bureau adds the question to its materials, and implementation begins at the start of the following calendar year (October).

Recommendation 8. The Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat is updated with information about AC as it becomes available. This tool can be shared, along with refined guidance, with state-level administrators of programs like LIHEAP and WAP to target investments to the households most vulnerable to overheating and resulting heat illness and death. The CDC could integrate AC coverage within its existing syndromic surveillance programs on extreme heat, as an additional layer of “risk” for targeted public health deployment during high-heat events.

Conclusion

The U.S. lacks fine-scaled data to determine whether households can access working AC systems/units and operate them during extreme heat events. Adding a question to the American Community Survey will provide life-saving information for emergency responders, social service providers, and city staff as extreme heat events become more frequent and intense. This fine-scaled information will also aid in distributing LIHEAP and WAP funding and increase the federal government’s ability to protect the most vulnerable residents from life-threatening extreme heat events.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

Revolutionizing Research and Treatments for Infection-Associated Chronic Diseases

The National Institutes of Health should create an Office of Infection-Associated Chronic Illness Research. Reporting directly to the NIH Director, the Office would provide a timely and urgently needed command center for prioritizing innovative research across a group of complex, chronic conditions that are all known to be downstream effects of viral and bacterial infections. These include Long Covid and many others. The Office of IACIR should champion transformative, catalytic research that cuts across multiple institutes and centers.

The Covid-19 pandemic has proven to be a massive disabling event that has shined a bright and historic light on infection-associated illnesses. As many as 1 in 5 adults develops a new health condition in the aftermath of Covid, and for many, the condition could be lifelong. This should not come as a surprise. For decades, millions of sufferers have experienced debilitating illness, gaslighting, misunderstanding, lack of insurance coverage, disability, and no FDA-approved treatment options. In alignment with President Biden’s National Research Action Plan for Long Covid, the Office should pursue a two-pronged approach that includes pioneering next-generation diagnostics while also fast-tracking patient-centered clinical trials for repurposed drugs. The Office would spur creation of a world in which all people with an infection-associated chronic illness have access to a timely diagnosis and effective treatments.

Challenge and Opportunity

The world faces a massive problem with long term disability due to the long-term effects of infections. The cost of Long Covid is estimated at $3.7 trillion over five years, according to Harvard University economist David Cutler. Within the United States, it is estimated that up to 23 million Americans currently have or have had Long Covid or similar complex, chronic conditions.

Long Covid is part of a family of infection-associated chronic illnesses. More than two-thirds of people with Long Covid develop moderate to severe dysautonomia, most commonly presenting as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), a condition estimated to impact up to 3 million Americans prior to the pandemic. Dysautonomia symptoms, the result of a problem with the autonomic nervous system, include lightheadedness, palpitations, profound fatigue, exercise intolerance, cognitive impairment, gastrointestinal dysmotility and more. Similarly, about half of all Long Covid cases fit the criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). With two of the most common symptoms of ME/CFS being unrelenting exhaustion and brain fog. These symptoms are also seen in persistent Lyme disease. Patients with Long COVID, dysautonomia/POTS, ME/CFS or persistent Lyme disease often present with autoimmunity, small fiber neuropathy, gut dysbiosis, migraine, mast-cell activation syndrome (MCAS), Ehlers Danlos syndrome (EDS), and cranio-cervical instability (CCI).

While there appears to be significant shared pathophysiology and symptomatology between these diseases, progress in each of these diseases has been stymied because research has been siloed and underfunded. For instance, one analysis of NIH funding and disease burden showed that ME/CFS received just 7% of research dollars commensurate with disease burden, making it the most underfunded disease at NIH with known disability-adjusted life years data. Reaching parity with diseases of similar severity and prevalence would require a fourteen fold increase in ME/CFS.

Each condition is in its own silo for a different reason, making full coordination impossible until a new NIH office is established. For instance, Gulf War illness doesn’t have an NIH budget line item at all; it is studied through the Department of Defense’s medical research program. And while the NIH studies acute Lyme infections, the agency didn’t formally start studying “post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome” until 2023. For POTS, there is a lack of research showing quality of life disruptions for dysautonomia sufferers. This makes it impossible to quantify the gap in research funding given the disorder’s large economic burden. And for decades, ME/CFS research was hamstrung in part because it was housed in NIH’s poorly funded Office of Research on Women’s Health. In short, to adapt a line from Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, “Understood diseases are all alike; every misunderstood disease is misunderstood in its own way.”

Therefore, studying infection-related conditions all together, within one multidisciplinary NIH office, provides an unprecedented scientific opportunity to build on existing research and apply a comprehensive molecular biology approach toward unraveling how the body’s systems go awry in complex disorders. Given the urgent need to rapidly scale interventions, these diseases also provide an ideal opportunity to make immediate progress with clinical trials for repurposed drugs.

This synergistic approach is also the most efficient and cost-effective from a financial standpoint, because it creates economies of scale and reduces redundancies that result from researching each disease piecemeal, from their respective silos. Streamlining research under one roof would also eliminate red tape and bureaucratic inefficiencies, thus ensuring the type of low barriers to entry and high return on investment (ROI) that are necessary to attract private sector participation. Moreover, a plan to fast-track FDA approval of promising drug therapies would both incentivize pharmaceutical involvement and guarantee that patients receive life-changing treatments as quickly as possible.

ME/CFS is an often lifelong condition in which about half of all patients are disabled and cannot work full-time. The level of disability for ME/CFS has been compared to that of cancer, heart disease, and last-stage AIDS. POTS is also often a lifelong condition, with a majority of patients reporting symptoms staying the same or worsening over time. Health-related quality-of-life in POTS is worse than what is seen in diabetes, neoplasms, cardiovascular disease, COPD, HIV and chronic kidney disease. Less than half of adult POTS patients are employed, and of those who are able to work, POTS symptoms prevent a majority of them from working as many hours as they would like to work. More than half of college students with POTS drop out of college due to the severity of their POTS symptoms. Given the high rate of POTS and ME/CFS with the Long Covid population, it follows that Long Covid patients can expect a similar prognosis. For all three diagnoses, there are as yet no treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The landscape for drugs to treat these conditions is also undeveloped.

Given the magnitude of the challenge, a realistic budget for a Long Covid “moonshot” should be at least $1 billion per year for 10 years. Therefore, to incorporate all infection-associated chronic illnesses, the budget would need to be a great deal higher. This is an historic opportunity for the U.S. to lead with state-of-the art scientific research. A fully funded and comprehensive research program can tackle these diseases, alleviate suffering, and enable these individuals once again to pursue their dreams as productive members of society.

Several NIH offices created in recent years show us how to seize the current opportunity. In response to the most recent previous global pandemic, HIV/AIDS, the NIH created the Office of AIDS Research in 1988.

Later, the NIH established the Office of Women’s Health Research in 1990, after the Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues asked the General Accounting Office to conduct an investigation into NIH’s implementation of guidelines for inclusion of women in medical research. The OWHR remedies longstanding inequities in which women were dramatically underrepresented in clinical research.

More recently, in 2023, the NIH launched its Office of Autoimmune Research. The office was originally proposed by then-Senator Joe Biden in 1999. In 2022, the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine held a research symposium, and issued a conclusive report, outlining five options for how to elevate federal research on autoimmune disease.

One of those called for the establishment of the Office, situated within the Office of the Director. The authors noted the benefits of that high-level placement, including elevated visibility, sustained leadership, and becoming a clear focal point for intramural, extramural, training, and outreach activities. Placing it close to the NIH Director “may provide many of the benefits of a new Institute…with fewer bureaucratic costs or controversies,”they wrote.

On June 29-30, 2023, NASEM held a similar symposium to begin establishing a common research agenda for infection-associated chronic illnesses. The creation of the new Office of IACIR should organically flow out of this past summer’s NASEM meeting, just as the Office of Autoimmune Research did from the 2022 meeting.

Last year’s NASEM symposium was a watershed moment in the history of chronic illness patient advocacy movements, which for decades had effectively been voices in the wilderness. The nation’s most esteemed scientific body had consolidated the foundational literature for each condition, identified the possibilities for common pathophysiology, and illuminated a path forward. This establishes a clear generational opportunity to solve a major set of disabling conditions globally, and positions American institutions to lead in pioneering these breakthroughs.

Plan of Action

Working with champions in Congress, a select group of Administration officials – across Office of Science and Technology Policy, Domestic Policy Council, NIH, and the HHS Assistant Secretary for Health – would serve as executive sponsors and provide oversight.

Each of these primary stakeholders should take responsibility for the following steps in executing this proposal.

Clearly state the goals of the office and its NIH-wide responsibilities.

Since this research must span neurology, immunology, cardiology, pulmonology, virology, and other fields to encompass the multi-system impact of these illnesses, the Office must have a clearly-defined mission and authority to integrate work across multiple NIH institutes.

The key functions of the Office should include:

- Evangelize the concept of infection-associated chronic illnesses to the public, health providers, and researchers and administrators inside NIH

- Ensure that NIH and health systems are responsive to long-term sequelae of current and future pandemics

- Serve as a convener for industry, disease organizations, patient advocates, and patients across IACIs to set research priorities and design studies

- Embrace a spirit of co-producing research with patients, acknowledging the wisdom that those with lived experience bring to the scientific enterprise,

- Advance state-of-the-art IACI research focusing on biomarkers, root causes, and therapeutic targets in collaboration with patient communities

- Hold budgetary authority to fund and coordinate IACI research across all Institutes

- Identify and validate common biomarkers and therapeutic targets across conditions

- Collaborate with other U.S. government agencies (FDA, CDC, SSA, AHRQ, PCORI, etc.), community groups, and global organizations to catalyze rapid diagnosis, effective treatment, and relevant disability services/supports for all IACI patients

- Advise Director of NIH, HHS, and other entities on IACI research. In particular, this Office should directly coordinate with HHS’s Office of Long Covid Research and Practice so that IACI research is synergistic with a cabinet-level champion

Identify leadership and staffing.

At minimum, the office would require robust staffing and could be funded through several avenues.

To begin, the Office of IACIR’s authority could be inaugurated under the auspices of the NIH’s Common Fund. This is a highly attractive option because it wouldn’t require additional Congressional funding allocations. The fund creates a space where investigators across NIH institutes collaborate on innovative research in order to address high-priority challenges and make a broader impact on the scientific community. Among the Common Fund’s most successful initiatives is the Undiagnosed Diseases Network.

To best amplify its mission, the office should be placed within the Office of the Director. Importantly, we stipulate that the NIH Director leads this new Office in consultation with community stakeholders, who have decades of experience managing infection-associated chronic conditions.

Congress could also consider bicameral legislation to create this new NIH office. If passed, policymakers could consider taking approaches similar to those taken for AIDS and Alzheimer’s, which could mandate special oversight of this Office. AIDS legislation, for instance, requires NIH to submit a research plan directly to Congress. Alternatively, Congress should also use the authority of the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program to support and oversee this Office.

Launch a comprehensive IACI research agenda.

The Office should create a high-level blueprint as well as a more detailed agenda with an implementation plan for carrying it out. Research projects should mirror the most recent findings and avenues for next steps discussed at the NASEM symposium.

Diagnostic research activities should include:

- Advanced central and peripheral nervous system analysis and imaging

- AI-based analysis of immune profiles and comprehensive panels

- Investigation of viral or bacterial persistence, microclotting/coagulation parameters, tissue pathology, and epigenetics

Clinical trial platforms should support state-of-the-art techniques including:

- Decentralized, multi-arm clinical trials with dynamic, adaptable design

- Cross-diagnosis research amongst IACIs with common co-morbidity

- More efficient testing of repurposed medications

Not only would these approaches incorporate best practices scientifically, but by combining multiple diseases into single studies, they would create economic efficiencies that would reduce costs overall and make it easier and more cost-effective to roll out treatments.

Scale it into an Institute.

Once the new Office becomes established in the NIH and has put “points on the board” with early successes in its first five years, leaders at NIH and in the Administration should evaluate how to develop it into a Center or Institute. Alternatively, Congress could pass further legislation to elevate it to the level of an Institute.

An Institute is likely the best vehicle to fully execute a true long-term high investment capable of curing these diseases. Given the economic and social burden of these diseases – and coupled with their historic neglect – an annual research budget measured in the billions of dollars may be required.

Conclusion

Throughout its history, the NIH has continually evolved to meet new and pressing challenges as scientific understanding has progressed. Globalization, microbial resistance, and climate change continue to upset the balance of the natural world, with unpredictable effects on the human population. It’s not a question of if – but rather when – the next global pandemic will occur. Every pandemic causes long-term health consequences. The research advanced by this Office would foster pandemic resilience against the types of global infectious threats that will become increasingly common in the modern world. At the same time, it would help address the large swath of disability from the trickle-down of chronic illnesses triggered by everyday community infections as well.

Just as the NIH Office of AIDS Research has made great strides against AIDS, a new Office of Infection-Associated Chronic Illness Research will turn the tide against Long Covid and its many cousins. By diagnosing, managing, treating and ultimately curing these conditions, this program will help many millions get their lives and careers back. As they rejoin the workforce and contribute to the economy, the returns generated by this Office will exceed its costs by many orders of magnitude.

The Office of IACIR should dynamically collaborate with several offices at the cutting edge. First among these is the Office of Long Covid Research and Practice, established in 2023 under the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), includes an advisory committee composed of as many as 20 members.

Next, our future NIH Office should work in partnership with the federal government’s new health moonshot agency – the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) – which is uniquely suited to help lead on building next-generation diagnostics for infection-associated chronic illnesses. Its model calls for rapid high-risk, high-reward science. Launched in 2022, ARPA-H is currently hiring its first slate of program managers, leading innovative projects that are disease-agnostic. Infection-associated chronic illnesses could be a target of a future ARPA-H program manager.

The Office should work closely with the Food and Drug Administration, such that safe and effective repurposed drugs can be approved for this patient population.

And throughout all of this, the Office must collaborate with the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which has funded innovative work by the Patient Led Research Collaborative on Covid-19 to develop patient scorecards to grade the efficacy and quality of research proposals. To improve equity and stakeholder engagement, NIH should consider piggybacking off such efforts.

- Establish a consensus vocabulary; assess which chronic diseases or illnesses are “infection-associated,” and potentially expand into more areas

- Annually develop and evaluate a strategic plan for all IACI research across NIH Institutes, Centers, and Offices

- By the end of its first year, hold an international conference to rapidly develop a common research agenda, timeline, and milestones toward key accomplishments by 2030

- Accelerate development of a common IACI biobank by leveraging existing disease-specific biobanking initiatives

- Build research infrastructure to seed and sustain diverse and multidisciplinary IACI scientific workforce

- Establish advisory council for whole-of-government approach to IACI research, care, and services

- Involve and incentivize the private sector and fast-tracking FDA approval for promising drugs

How an Obscure Law Shapes the Way the Public Engages with the Food and Drug Administration

Every day, the executive branch of the federal government makes transformative policy changes. When federal agencies need expert input, they look to advice from external experts and interested citizens through a series of public engagement mechanisms, from public meetings to public comment. Of these, only one mechanism allows the executive branch to actively source consensus-based public advice and for external experts to directly advise policymakers, the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA). And it’s a law many Americans have never heard of.

FACA enables agencies to create advisory committees

Enacted in 1972, FACA governs expert and public engagement with executive branch decision making. FACA articulates rules for the establishment, operation, and termination of advisory committees (AC), groups of experts that the federal agencies establish, manage, and use to provide external advice on key policy questions. At any given moment in time, there are ~1000 active ACs across the federal government making crucial recommendations to agency leaders.

At the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), FACA is essential to the workings of the agency’s regulatory engine and public health mission. The FDA uses its ACs to provide independent advice on medical products (drugs and devices), providing a unique window for experts and the public to comment on cutting-edge medical products in the approvals pipeline. ACs capture the headlines through their “yes” or “no” votes on product approval, raising spirits or breaking hearts. Industry takes notice: medical product sponsors spend months preparing for these meetings, supported by a boutique industry geared to help them “ace” their AC meetings.

ACs need to be reformed to build public trust in the FDA

While ACs are a crucial transparency measure for an agency like FDA that is currently grappling with declining public trust, the system has been repeatedly under fire. Recent controversies include FDA’s public overruling of AC recommendations against approval for hydrocodone, an opioid pain reliever, and aducanumab, an Alzheimer’s treatment. After aducanumab approval, several high-profile resignations exacerbated the trust-issues. What’s more, FDA’s use of ACs is in decline, with the percentage of new drugs reviewed by ACs decreasing by almost 10 times from 2010-2021. These actions are in direct conflict with current whole-of-government efforts to modernize regulatory review and expand meaningful participation in the regulatory decision making process. Advancing racial equity, opening up the scientific enterprise, and broadening public engagement in regulatory decisions will require transformative policy solutions for the FDA.

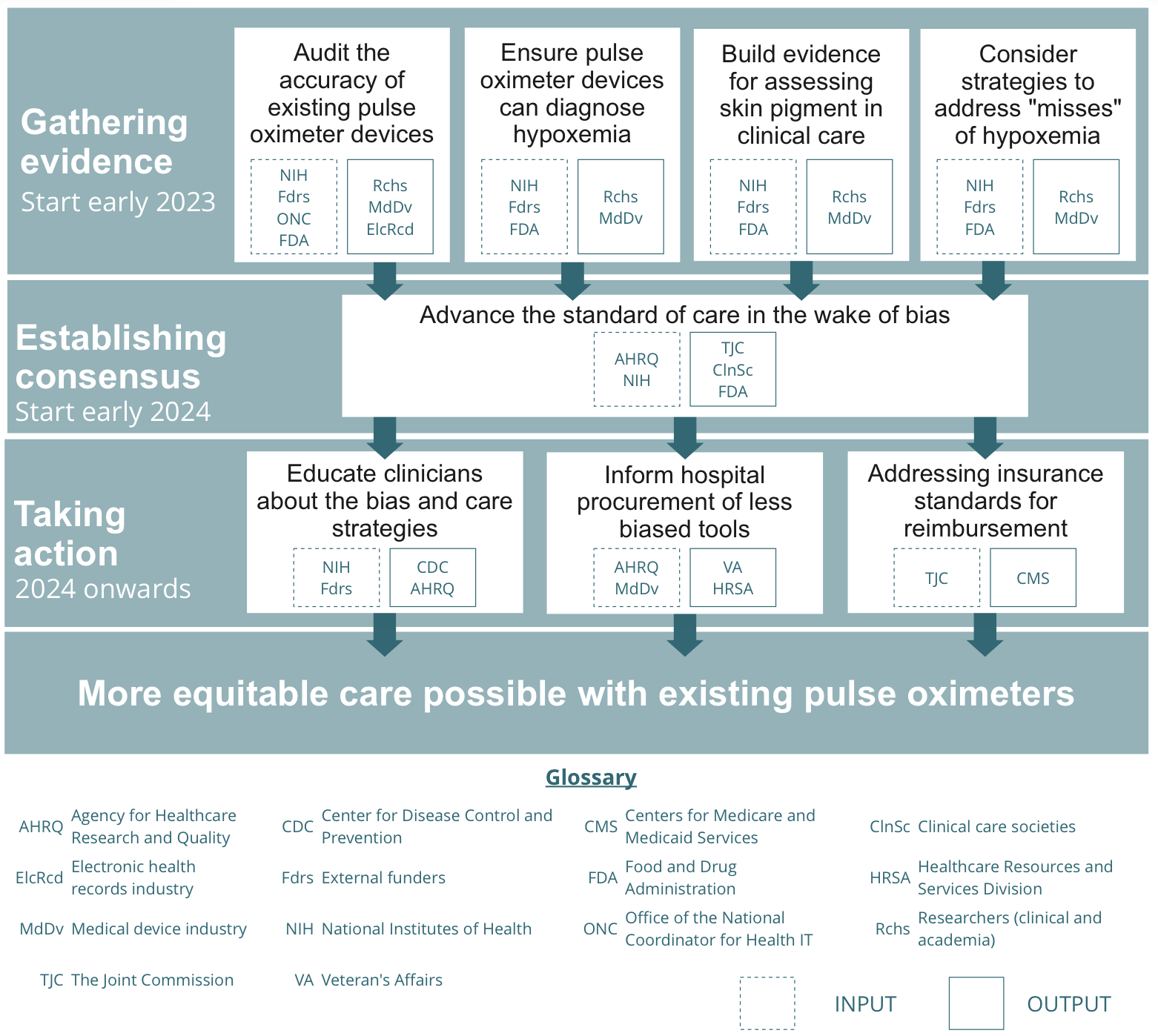

To re-envision how the FDA and other federal agencies engage external scientific experts and the public to address critical challenges facing public health, FAS is diving deep into how FACA is put into action at the FDA. Over the next year, FAS will be engaging AC members on their experiences in service, understanding key evidence needs at the agency that a reformed AC system could better meet, and scoping necessary process, regulatory, and statutory changes to the AC system. This will build upon our previous efforts: FAS has participated in and provided public comment to many AC meetings and documented how ACs are slow to respond to emerging questions of regulatory concern in our ongoing work to address bias in medical innovation. FAS has also documented strategies to improve science advice for the executive branch, including FACA reform. We invite you to follow this work and join us in calling for reforms that strengthen trust in the FDA Advisory Committee system.

Calls for systematic reform are coming from leadership across the FDA, yet consensus does not yet exist on what those reforms should look like. From recommendations to get rid of voting requirements at meetings (already receiving Congressional scrutiny), to broadening membership, including to members with conflicts of interest, to increasing review timelines of sponsor materials before meetings, there is no shortage of ideas for what this new system could look like. Non-profit leaders and academic researchers have also started coming together to make recommendations that address FDA’s influence over Advisory Committee discussions and ongoing issues with agency leadership overruling the AC’s vote. There could also be clearer requirements for the FDA to respond to AC recommendations and make set public timelines for agency action. Twenty-five Attorneys General recently called on the FDA to release updates to its actions on pulse oximetry one year after the AC meeting.

More broadly, the FDA can learn from other agencies with explicit policies guiding their public engagement, such as the Meaningful Involvement Policy at the Environmental Protection Agency. These FDA-specific recommendations build upon long-standing calls to reform FACA to reduce the administrative barriers that make it challenging to solicit expert advice when needed or lead some agencies to forgo processes that could invoke FACA altogether.

To improve patient care, it is essential to create a nimble, participatory, and transparent process that ensures regulated products will benefit the health of all Americans. AC reform will be essential to building the FDA’s capacity to address increasingly complex regulatory science challenges, from artificial intelligence, to real-world data, to emerging platform technologies, to health inequity, while also improving the federal government’s ability to more rapidly generate consensus-based science advice. FAS is excited to play our part in strengthening evidence-based policy by engaging in policy entrepreneurship to engage stakeholders, develop roadmaps, and advocate for change.

Moving the Nation: The Role of Federal Policy in Promoting Physical Activity

Physical activity is one of the most powerful tools for promoting health and wellbeing. Movement is not only medicine—effective at treating a range of physical and mental health conditions—but it is also preventive medicine, because movement reduces the risk for many conditions ranging from cancer and heart disease to depression and Alzheimer’s disease. But rates of physical inactivity and sedentary behavior have remained high in the U.S. and worldwide for decades.

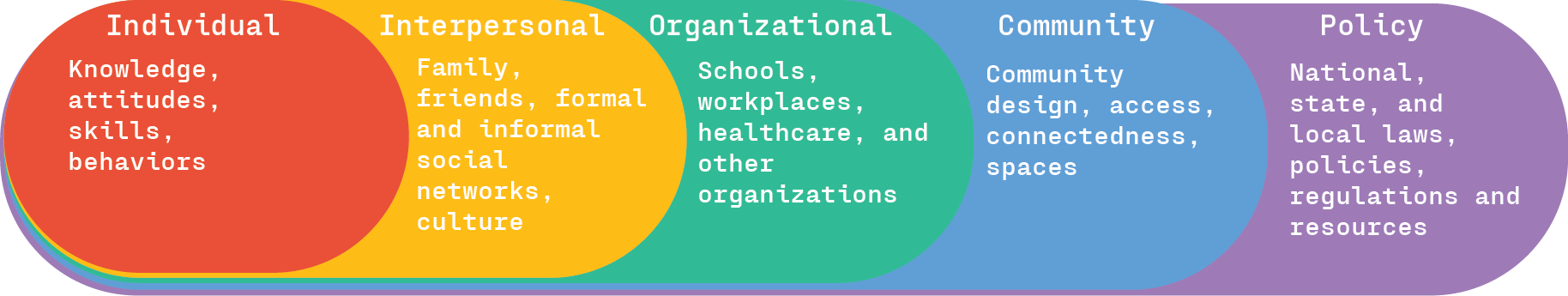

Engagement in physical activity is impacted by myriad factors that can be viewed from a social ecological perspective. This model views health and health behavior within the context of a complex interplay between different levels of influence, including individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy levels. When it comes to healthy behavior such as physical activity, sustainable change is considered most likely when these levels of influence are aligned to support change. Every level of influence on physical activity within a social-ecological framework is directly or indirectly affected by federal policy, suggesting physical activity policy has the potential to bring about substantial changes in the physical activity habits of Americans.

Why are federal physical activity policies needed?

Physical inactivity is recognized as a public health issue, having widespread impacts on health, longevity, and even the economy. Similar to other public health issues over past decades such as sanitation and tobacco use, federal policies may be the best way to coordinate large-scale changes involving cooperation between diverse sectors, including health care, transportation, environment, education, workplace, and urban planning. An active society requires the infrastructure, environment, and resources that promote physical activity. Federal policies can meet those needs by improving access, providing funding, establishing regulations, and developing programs to empower all Americans to move more. Policies also play an important role in removing barriers to physical activity, such as financial constraints and lack of safe spaces to move, that contribute to health disparities. With such a variety of factors impacting active lifestyles, physical activity policies must have inter-agency involvement to be effective.

What physical activity initiatives exist currently?

Analysis of publicly available information revealed that there are a variety of initiatives currently in place at the federal level, across several departments and agencies, aimed at increasing physical activity levels in the U.S. Information about each initiative was evaluated for their correspondence with levels of the social-ecological model, as summarized in the table. Note that it is possible the search that was conducted did not identify every relevant effort, thus there could be additional initiatives that are not included below.

Given the large number of groups with the shared goal of increasing physical activity in the nation, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) may help to promote coordination of goals and implementation strategies.

These and other federal departments and agencies can coordinate action with state and local partners, for example in healthcare, business and industry, education, mass media, and faith-based settings, to implement physical activity policies.

The CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation initiative provides an example of this approach. This campaign, launched in 2020, has the goal of helping 27 million Americans become more physically active by 2027. By taking action steps focused on program delivery, partnership engagement, communication, training, and continuous monitoring and evaluation, the campaign seeks to help communities implement evidence-based strategies across sectors and settings to provide equitable and inclusive access to safe spaces for physical activity. According to our analysis, the strategies of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative are aligned with the social-ecological model. The Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network, a research partner of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative, provides an example of coordinating with partners in other sectors to promote physical activity. Through collaboration across sectors, the network brings together diverse partners to put into practice research on environments that maximize physical activity. The network includes work groups focused on equity and inclusion, parks and green space, rural active living, school wellness, transportation policy and planning, and business/industry.

The Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, announced in September 2022, also includes strategies that are consistent with a social-ecological model. The strategy outlines steps toward the goal of ending hunger and increasing healthy eating and physical activity by 2030 so that fewer Americans will experience diet-related diseases. Pillar 4 of the strategy is to “make it easier for people to be more physically active—in part by ensuring that everyone has access to safe places to be active—increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity, and conduct research on and measure physical activity.” The strategy specifies goals such as building environments that promote physical activity (e.g., connecting people to parks; promoting active transportation and land use policies to support physical activity) and includes a call to action for a whole-of-society response involving the private sector, state, local, and territory governments, schools, and workplaces.

The Congressional Physical Activity Caucus has been active in introducing legislation that can help realize the goals of the current physical activity initiatives. For example, in February 2023, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), co-chair of the Caucus, introduced the Promoting Physical Activity for Americans Act, a bill that would require the Department of Health and Human Services to continue issuing evidence-based physical-activity guidelines and detailed reports at least every 10 years, including recommendations for population subgroups (e.g., children or individuals with disabilities). In addition, members of the Caucus, along with other members of congress, reintroduced the bipartisan, bicameral Personal Health Investment Today (PHIT) Act in March 2023. This legislation seeks to encourage physical activity by allowing Americans to use a portion of the money saved in their pre-tax health savings account (HSA) and flexible spending account (FSA) toward qualified sports and fitness purchases, such as gym memberships, fitness equipment, physical exercise or activity programs and youth sports league fees. The bill would also allow a medical care tax deduction for up to $1,000 ($2,000 for a joint return or a head of household) of qualified sports and fitness expenses per year.

What progress has been made?

There are signs that some of the national campaigns are leading to changes at other levels of society. For example, 46 cities, towns, and states have passed an Active People, Healthy Nation Proclamation as of September 2023. According to the State Routes Partnership, which develops “report cards” for states based on their policies supporting walking, bicycling, and active kids and communities, many states have shown movement in their policies between 2020 and 2022, such as implementing new policies to support walking and biking and increasing state funding for active transportation. However, more time is needed to determine the extent to which recent initiatives are helping to create a more active country, since most were initiated in the past two or three years. Predating the current initiatives, the overall physical activity level of Americans increased from 2008 to 2018, but there has been little change since that time, and only about one-quarter of adults meet the physical activity guidelines established by the CDC.

Clearly, there is a critical need for concerted effort to implement the strategies outlined in current physical activity initiatives so that national policies have the intended impacts on communities and on individuals. Leveraging provisions in existing legislation related to the social-ecological model of physical activity promotion will also help with implementation. For example, title III-D of the Older Americans Act supports healthy lifestyles and promotes healthy behaviors amongst older adults (age 60 and older), providing funding for evidence-based programs that have been proven to improve health and well-being and reduce disease and injury. Physical activity programs are prime candidates for such funding. In addition, programs under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act are helping to change the current car-dependent transportation network, providing healthier and more sustainable transportation options, including walking, biking, and using public transportation, and are providing investments in environmental programs to improve public health and reduce pollution. For example, states can use funds from the Highway Safety Improvement Program for bicycle and pedestrian highway safety improvement projects, and funding is available through the Carbon Reduction Program for programs that help reduce dependence on single-occupancy vehicles, such as public transportation projects and the construction, planning, and design of facilities for pedestrians, bicyclists, and other non-motorized forms of transportation.

Partnering with non-governmental groups working towards common goals, such as the Physical Activity Alliance, can also help with implementation. The Alliance’s National Physical Activity Plan is based on the socio-ecological model and includes recommendations for evidence-based actions for 10 societal sectors at the national, state, local and institutional levels, with a focus on making change at the community level. The plan shares many priorities with those of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative, while also introducing new goals, such as establishing a CDC Office of Physical Activity and Health.

With coordinated action based on established public health models, such as the social-ecological framework, federal policies can be successfully implemented to make the systemic changes that are needed to create a more active nation.

The work for this blog was undertaken before Dr. Dotson joined the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Dr. Dotson is solely responsible for this blog post’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

It’s Time to Move Towards Movement as Medicine

For over 10 years, physical inactivity has been recognized as a global pandemic with widespread health, economic, and social impacts. Despite the wealth of research support for movement as medicine, financial and environmental barriers limit the implementation of physical activity intervention and prevention efforts. The need to translate research findings into policies that promote physical activity has never been higher, as the aging population in the U.S. and worldwide is expected to increase the prevalence of chronic medical conditions, many of which can be prevented or treated with physical activity. Action at the federal and local level is needed to promote health across the lifespan through movement.

Research Clearly Shows the Benefits of Movement for Health

Movement is one of the most important keys to health. Exercise benefits heart health and physical functioning, such as muscle strength, flexibility, and balance. But many people are unaware that physical activity is closely tied to the health conditions they fear most. Of the top five health conditions that people reported being afraid of in a recent survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the risk for four—cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, and stroke—is increased by physical inactivity. It’s not only physical health that is impacted by movement, but also mental health and other aspects of brain health. Research shows exercise is effective in treating and preventing mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, rates of which have skyrocketed in recent years, now impacting nearly one-third of adults in the U.S. Physical fitness also directly impacts the brain itself, for example, by boosting its ability to regenerate after injury and improving memory and cognitive functioning. The scientific evidence is clear: Movement, whether through structured exercise or general physical activity in everyday life, has a major impact on the health of individuals and as a result, on the health of societies.

Movement Is Not Just about Weight, It’s about Overall Lifelong Health

There is increasing recognition that movement is important for more than weight loss, which was the primary focus in the past. Overall health and stress relief are often cited as motivations for exercise, in addition to weight loss and physical appearance. This shift in perspective reflects the growing scientific evidence that physical activity is essential for overall physical and mental health. Research also shows that physical activity is not only an important component of physical and mental health treatment, but it can also help prevent disease, injury, and disability and lower the risk for premature death. The focus on prevention is particularly important for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia that have no known cure. A prevention mindset requires a lifespan perspective, as physical activity and other healthy lifestyle behaviors such as good nutrition earlier in life impact health later in life.

Despite the Research, Americans Are Not Moving Enough

Even with so much data linking movement to better health outcomes, the U.S. is part of what has been described as a global pandemic of physical inactivity. Results of a national survey by the CDC published in 2022 found that 25.3% of Americans reported that outside of their regular job, they had not participated in any physical activity in the previous month, such as walking, golfing, or gardening. Rates of physical inactivity were even higher in Black and Hispanic adults, at 30% and 32%, respectively. Another survey highlighted rural-urban differences in the number of Americans who meet CDC physical activity guidelines that recommend ≥ 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and ≥ 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening exercise. Respondents in large metropolitan areas were most active, yet only 27.8% met both aerobic and muscle strengthening guidelines. Even fewer people (16.1%) in non-metropolitan areas met the guidelines.

Why are so many Americans sedentary? The COVID-19 pandemic certainly exacerbated the problem; however, data from 2010 showed similar rates of physical inactivity, suggesting long-standing patterns of sedentary behavior in the country. Some of the barriers to physical activity are internal to the individual, such as lack of time, motivation, or energy. But other barriers are societal, at both the community and federal level. At the community level, barriers include transportation, affordability, lack of available programs, and limited access to high-quality facilities. Many of these barriers disproportionately impact communities of color and people with low income, who are more likely to live in environments that limit physical activity due to factors such as accessibility of parks, sidewalks, and recreation facilities; traffic; crime; and pollution. Action at the state and federal government level could address many of these environmental barriers, as well as financial barriers that limit access to exercise facilities and programs.

Physical Inactivity Takes a Toll on the Healthcare System and the Economy

Aside from a moral responsibility to promote the health of its citizens, the government has a financial stake in promoting movement in American society. According to recent analyses, inactive lifestyles cost the U.S. economy an estimated $28 billion each year due to medical expenses and lost productivity. Physical inactivity is directly related to the non-communicable diseases that place the highest burden on the economy, such as hypertension, heart disease, and obesity. In 2016, these types of modifiable risk factors comprised 27% of total healthcare spending. These costs are mostly driven by older adults, which highlights the increasing urgency to address physical inactivity as the population ages. Physical activity is also related to healthcare costs at an individual level, with savings ranging from 9-26.6% for physically active people, even after accounting for increased costs due to longevity and injuries related to physical activity. Analysis of 2012 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) found that each year, people who met World Health Organization aerobic exercise guidelines, which correspond with CDC guidelines, paid on average $2,500 less in healthcare expenses related to heart disease alone compared to people who did not meet the recommended activity levels. Changes are needed at the federal, state, and local level to promote movement as medicine. If changes are not made in physical activity patterns by 2030, it is estimated that an additional $301.8 billion of direct healthcare costs will be incurred.

Government Agencies Can Play a Role in Better Promoting Physical Activity Programs

Promoting physical activity in the community requires education, resources, and removal of barriers in order for programs to have a broad reach to all citizens, including communities that are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic of physical inactivity. Integrated efforts from multiple agencies within the federal government is essential.

Past initiatives have met with varying levels of success. For example, Let’s Move!, a campaign initiated by First Lady Michelle Obama in 2010, sought to address the problem of childhood obesity by increasing physical activity and healthy eating, among other strategies. The Food and Drug Administration, Department of Agriculture, Department of Health and Human Services including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Department of Interior were among the federal agencies that collaborated with state and local government, schools, advocacy groups, community-based organizations, and private sector companies. The program helped improve the healthy food landscape, increased opportunities for children to be more physically active, and supported healthier lifestyles at the community level. However, overall rates of childhood obesity remained constant or even increased in some age brackets since the program started, and there is no evidence of an overall increase in physical activity level in children and adolescents since that time.

More recently, the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2030 campaign established data-driven national objectives to improve the health and well-being of Americans. The campaign was led by the Federal Interagency Workgroup, which includes representatives across several federal agencies including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Department of Education. One of the campaign’s leading health indicators—a small subset of high-priority objectives—is increasing the number of adults who meet current minimum guidelines for aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity from 25.2% in 2020 to 29.7% by 2030. There are also movement-related objectives focused on children and adolescents as well as older adults, for example:

- Reducing the proportion of proportion of adults who do no physical activity in their free time

- Increasing the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who do enough aerobic physical activity, muscle-strengthening activity, or both

- Increasing the proportion of child care centers where children aged 3 to 5 years do at least 60 minutes of physical activity a day

- Increasing the proportion of adolescents and adults who walk or bike to get places

- Increasing the proportion of children and adolescents who play sports

- Increasing the proportion of older adults with physical or cognitive health problems who get physical activity

- Increasing the proportion of worksites that offer an employee physical activity program

Unfortunately, there is currently no evidence of improvement in any of these objectives. All of the objectives related to physical activity with available follow-up data either show little or no detectable change, or they are getting worse.

To make progress towards the physical activity goals established by the Healthy People 2030 campaign, it will be important to identify where breakdowns in communication and implementation may have occurred, whether it be between federal agencies, between federal and local organizations, or between local organizations and citizens. Challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., less movement outside of the house for people who now work from home) will also need to be addressed, with the recognition that many of these challenges will likely persist for years to come. Critically, financial barriers should be reduced in a variety of ways, including more expansive coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for exercise interventions as well as exercise for prevention. Policies that reflect a recognition of movement as medicine have the potential to improve the physical and mental health of Americans and address health inequities, all while boosting the health of the economy.

Towards a Well-Being Economy: Establishing an American Mental Wealth Observatory

Summary

Countries are facing dynamic, multidimensional, and interconnected crises. The pandemic, climate change, rising economic inequalities, food and energy insecurity, political polarization, increasing prevalence of youth mental and substance use disorders, and misinformation are converging, with enormous sociopolitical and economic consequences that are weakening democracies, corroding the social fabric of communities, and threatening social stability and national security. Globalization and digitalization are synchronizing, amplifying, and accelerating these crises globally by facilitating the rapid spread of disinformation through social media platforms, enabling the swift transmission of infectious diseases across borders, exacerbating environmental degradation through increased consumption and production, and intensifying economic inequalities as digital advancements reshape job markets and access to opportunities.

Systemic action is needed to address these interconnected threats to American well-being.

A pathway to addressing these issues lies in transitioning to a Well-Being Economy, one that better aligns and balances the interests of collective well-being and social prosperity with traditional economic and commercial interests. This paradigm shift encompasses a ‘Mental Wealth’ approach to national progress, recognizing that sustainable national prosperity encompasses more than just economic growth and instead elevates and integrates social prosperity and inclusivity with economic prosperity. To embark on this transformative journey, we propose establishing an American Mental Wealth Observatory, a translational research entity that will provide the capacity to quantify and track the nation’s Mental Wealth, generate the transdisciplinary science needed to empower decision makers to achieve multisystem resilience, social and economic stability, and sustainable, inclusive national prosperity.

Challenge and Opportunity

America is facing challenges that pose significant threats to economic security and social stability. Income and wealth inequalities have risen significantly over the last 40 years, with the top 10% of the population capturing 45.5% of the total income and 70.7% of the total wealth of the nation in 2020. Loneliness, isolation, and lack of connection are a public health crisis affecting nearly half of adults in the U.S. In addition to increasing the risk of premature mortality, loneliness is associated with a three-fold greater risk of dementia.

Gun-related suicides and homicides have risen sharply over the last decade. Mental disorders are highly prevalent. Currently, more than 32% of adults and 47% of young people (18–29 years) report experiencing symptoms of anxiety and depression. The COVID-19 pandemic compounded the burden, with a 25–30% upsurge in the prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders. America is experiencing a social deterioration that threatens its continued prosperity, as evidenced by escalating hate crimes, racial tensions, conflicts, and deepening political polarization.

To reverse these alarming trends in America and globally, policymakers must first acknowledge that these problems are interconnected and cannot effectively be tackled in isolation. For example, despite the tireless efforts of prominent stakeholder groups and policymakers, the burden of mental disorders persists, with no substantial reduction in global burden since the 1990s. This lack of progress is evident even in high-income countries where investments in and access to mental health care have increased.

Strengthening or reforming mental health systems, developing more effective models of care, addressing workforce capacity challenges, leveraging technology for scalability, and advancing pharmaceuticals are all vital for enhancing recovery rates among individuals grappling with mental health and substance use issues. However, policymakers must also better understand the root causes of these challenges so we can reshape the economic and social environments that give rise to common mental disorders.

Understanding and Addressing the Root Causes

Prevention research and action often focus on understanding and addressing the social determinants of health and well-being. However, this approach lacks focus. For example, traditional analytic approaches have delivered an extensive array of social determinants of mental health and well-being, which are presented to policymakers as imperatives for investment. These include (but are not limited to):

- Adverse early life exposures (abuse and neglect)

- Substance misuse

- Domestic, family, and community violence

- Unemployment

- Poverty and inequality

- Poor education quality

- Homelessness

- Social disconnection

- Food insecurity

- Pollution

- Natural disasters and climate change

This practice is replicated across other public health and social challenges, such as obesity, child health and development, and specific infectious and chronic diseases. Long lists of social determinants lobbied for investment lead policymakers to conclude that nations simply can’t afford to invest sufficiently to solve these health and social challenges.

However, it Is likely that many of these determinants and challenges are merely symptoms of a more systemic problem. Therefore, treating the ongoing symptoms only perpetuates a cycle of temporary relief, diverts resources away from nurturing innovation, and impedes genuine progress.

To create environments that foster mental health and well-being, where children can thrive and fulfill their potential, where people can pursue meaningful vocation and feel connected and supported to give back to communities, and where Americans can live a healthy, active, and purposeful life, policymakers must recognize human flourishing and prosperity of nations depends on a delicate balance of interconnected systems.

The Rise of Gross Domestic Product: An Imperfect Measure for Assessing the Success and Wealth of Nations

To understand the roots of our current challenges, we need to look at the history of the foundational economic metric, gross domestic product (GDP). While the concept of GDP had been established decades earlier, it was during a 1960 meeting of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development that economic growth became a primary ambition of nations. In the shadow of two world wars and the Great Depression, member countries pledged to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth, employment, efficiency, and development of the world economy as their top priority (Articles 1 & 2).

GDP growth became the definitive measure of a government’s economic management and its people’s welfare. Over subsequent decades, economists and governments worldwide designed policies and implemented reforms aimed at maximizing economic efficiency and optimizing macroeconomic structures to ensure consistent GDP growth. The belief was that by optimizing the economic system, prosperity could be achieved for all, allowing governments to afford investments in other crucial areas. However, prioritizing the optimization of one system above all others can have unintended consequences, destabilizing interconnected systems and leading to a host of symptoms we currently recognize as the social determinants of health.

As a result of the relentless focus on optimizing processes, streamlining resources, and maximizing worker productivity and output, our health, social, political, and environmental systems are fragile and deteriorating. By neglecting the necessary buffers, redundancies, and adaptive capacities that foster resilience, organizations and nations have unwittingly left themselves exposed to shocks and disruptions. Americans face a multitude of interconnected crises, which will profoundly impact life expectancy, healthy development and aging, social stability, individual and collective well-being, and our very ability to respond resiliently to global threats. Prioritizing economic growth has led to neglect and destabilization of other vital systems critical to human flourishing.

Shifting Paradigms: Building the Nation’s Mental Wealth

The system of national accounts that underpins the calculation of GDP is a significant human achievement, providing a global standard for measuring economic activity. It has evolved over time to encompass a wider range of activities based on what is considered productive to an economy. As recently as 1993, finance was deemed “explicitly productive” and included in GDP. More recently, Biden-Harris Administration leaders have advanced guidance for accounting for ecosystem services in benefit-cost analyses for regulatory decision-making and a roadmap for natural capital inclusion in the nation’s economic accounting services. This shows the potential to expand what counts as beneficial to the American economy—and what should be measured as a part of economic growth.

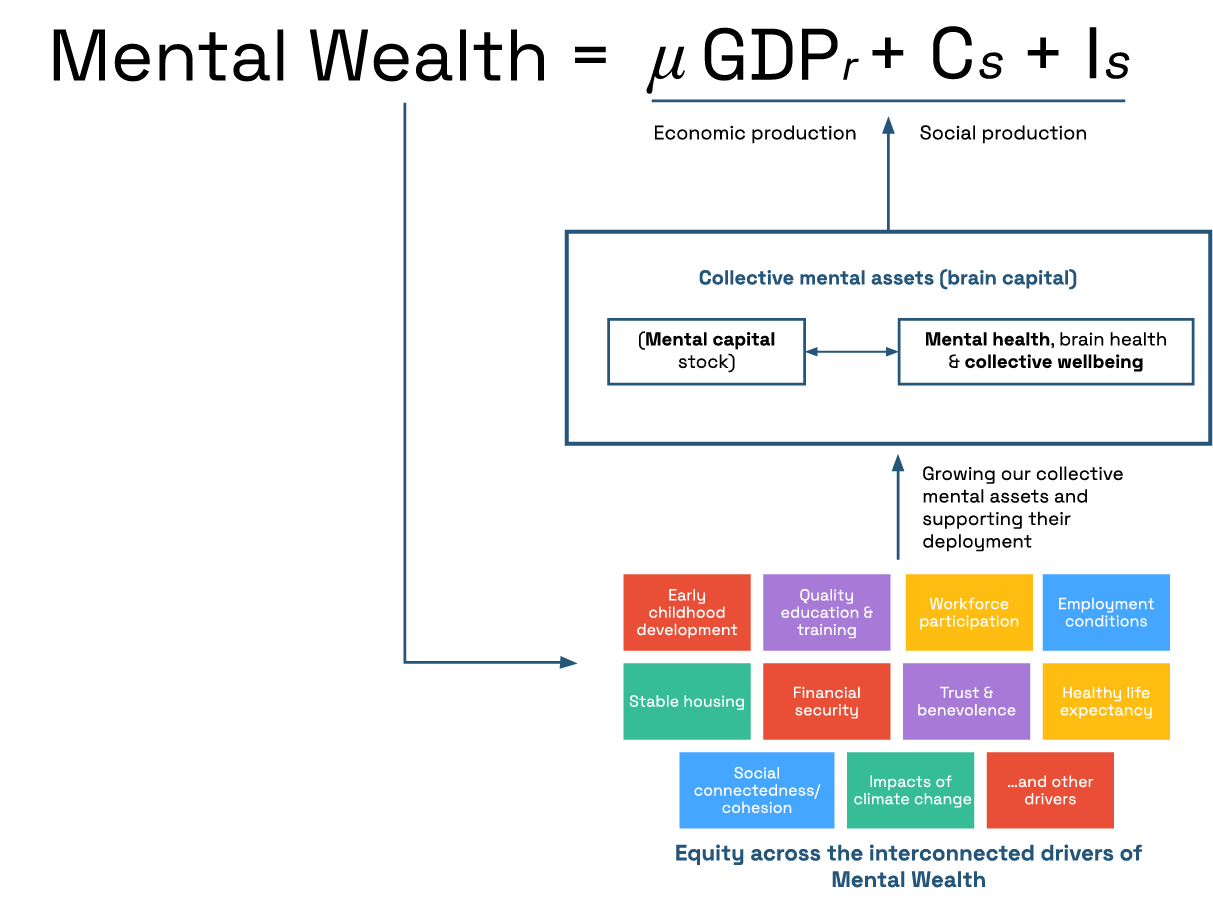

While many alternative indices and indicators of well-being and national prosperity have been proposed, such as the genuine progress indicator, the vast majority of policy decisions and priorities remain focused on growing GDP. Further, these metrics often fail to recognize the inherent value of the system of national accounts that GDP is based on. To account for this, Mental Wealth is a measure that expands the inputs of GDP to include well-being indicators. In addition to economic production metrics, Mental Wealth includes both unpaid activities that contribute to the social fabric of nations and social investments that build community resilience. These unpaid activities (Figure 1, social contributions, Cs) include volunteering, caregiving, civic participation, environmental restoration, and stewardship, and are collectively called social production. Mental Wealth also includes the sum of investment in community infrastructure that enables engagement in socially productive activities (Figure 1, social investment, Is). This more holistic indicator of national prosperity provides an opportunity to shift policy priorities towards greater balance between the economy and broader societal goals and is a measure of the strength of a Well-Being Economy.

Mental wealth is a more comprehensive measure of national prosperity that monetizes the value generated by a nation’s economic and social productivity.

Valuing social production also promotes a more inclusive narrative of a contributing life, and it helps to rebalance societal focus from individual self-interest to collective responsibilities. A recent report suggests that, in 2021, Americans contributed more than $2.293 trillion in social production, equating to 9.8% of GDP that year. Yet social production is significantly underestimated due to data gaps. More data collection is needed to analyze the extent and trends of social production, estimate the nation’s Mental Wealth, and assess the impact of policies on the balance between social and economic production.

Unlocking Policy Insights through Systems Modeling and Simulation

Systems modeling plays a vital role in the transition to a Well-Being Economy by providing an understanding of the complex interdependencies between economic, social, environmental, and health systems, and guiding policy actions. Systems modeling brings together expertise in mathematics, biostatistics, social science, psychology, economics, and more, with disparate datasets and best available evidence across multiple disciplines, to better understand which policies across which sectors will deliver the greatest benefits to the economy and society in balance. Simulation allows policymakers to anticipate the impacts of different policies, identify strategic leverage points, assess trade-offs and synergies, and make more informed decisions in pursuit of a Well-Being Economy. Forecasting and future projections are a long-standing staple activity of infectious disease epidemiologists, business and economic strategists, and government agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, geared towards preparing the nation for the economic realities of climate change.

Plan of Action

An American Mental Wealth Observatory to Support Transition to a Well-Being Economy

Given the social deterioration that is threatening America’s resilience, stability, and sustainable economic prosperity, the federal government must systemically redress the imbalance by establishing a framework that privileges an inclusive, holistic, and balanced approach to development. The government should invest in an American Mental Wealth Observatory (Table 1) as critical infrastructure to guide this transition. The Observatory will report regularly on the strength of the Well-Being Economy as a part of economic reporting (see Table 1, Stream 1); generate the transdisciplinary science needed to inform systemic reforms and coordinated policies that optimize economic, environmental, health and social sectors in balance such as adding Mental Wealth to the system of national accounts (Streams 2–4); and engage in the communication and diplomacy needed to achieve national and international cooperation in transitioning to a Well-Being Economy (Streams 5–6).

This transformative endeavor demands the combined instruments of science, policy, politics, public resolve, social legislation, and international cooperation. It recognizes the interconnectedness of systems and the importance of a systemic and balanced approach to social and economic development in order to build equitable long-term resilience, a current federal interagency priority. The Observatory will make better use of available data from across multiple sectors to provide evidence-based analysis, guidance, and advice. The Observatory will bring together leading scientists (across disciplines of economics, social science, implementation science, psychology, mathematics, biostatistics, business, and complex systems science), policy experts, and industry partners through public-private partnerships to rapidly develop tools, technologies, and insights to inform policy and planning at national, state, and local levels. Importantly, the Observatory will also build coalitions between key cross-sectoral stakeholders and seek mandates for change at national and international levels.

The American Mental Wealth Observatory should be chartered by the National Science and Technology Council, building off the work of the White House Report on Mental Health Research Priorities. Federal partners should include, at a minimum, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), specifically the Office of the Surgeon General (OSG) and Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP); the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA); the Office of Management and Budget; the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA); and the Department of Commerce (DOC), alongside strong research capacity provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Operationalizing the American Mental Wealth Observatory will require an annual investment of $12 million from diverse sources, including government appropriations, private foundations, and philanthropy. This funding would be used to implement a comprehensive range of priority initiatives spanning the six streams of activity (Table 2) coordinated by the American Mental Wealth Observatory leadership. Acknowledging the critical role of brain capital in upholding America’s prosperity and security, this investment offers considerable returns for the American people.

Conclusion

America stands at a pivotal moment, facing the aftermath of a pandemic, a pressing crisis in youth mental and substance use disorders, and a growing sense of disconnection and loneliness. The fragility of our health, social, environmental, and political systems has come into sharp focus, and global threats of climate change and generative AI loom large. There is a growing sense that the current path is unsustainable.

After six decades of optimizing the economic system for growth in GDP, Americans are reaching a tipping point where losses due to systemic fragility, disruption, instability, and civil unrest will outweigh the benefits. The United States government and private sector leaders must forge a new path. The models and approaches that guided us through the 20th century are ill-equipped to guide us through the challenges and threats of the 21st century.

This realization presents an extraordinary opportunity to transition to a Well-Being Economy and rebuild the Mental Wealth of the nations. An American Mental Wealth Observatory will provide the data and science capacity to help shape a new generation grounded in enlightened global citizenship, civic-mindedness, and human understanding and equipped with the cognitive, emotional, and social resources to address global challenges with unity, creativity, and resilience.

The University of Sydney’s Mental Wealth Initiative thanks the following organizations for their support in drafting this memo: FAS, OECD, Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Boston University School of Public Health, the Brain Capital Alliance, and CSART.

Brain capital is a collective term for brain skills and brain health, which are fundamental drivers of economic and social prosperity. Brain capital comprises (1) brain skills, which includes the ability to think, feel, work together, be creative, and solve complex problems, and (2) brain health, which includes mental health, well-being, and neurological disorders that critically impact the ability to use brain skills effectively, for building and maintaining positive relationships with others, and for resilience against challenges and uncertainties.

Social production is the glue that holds society together. These unpaid social contributions foster community well-being, support our economic productivity, improve environmental wellbeing, and help make us more prosperous and resilient as a nation.

Social production includes volunteering and charity work, educating and caring for children, participating in community groups, and environmental restoration—basically any activity that contributes to the social fabric and community well-being.

Making the value of social production visible helps us track how economic policies are affecting social prosperity and allows governments to act to prevent an erosion of our social fabric. So instead of just measuring our economic well-being through GDP, measuring and reporting social production as well gives us a more holistic picture of our national welfare. The two combined (GDP plus social production) is what we call the overall Mental Wealth of the nation, which is a measure of the strength of a Well-Being Economy.

The Mental Wealth metric extends GDP to include not only the value generated by our economic productivity but also the value of this social productivity. In essence, it is a single measure of the strength of a Well-Being Economy. Without a Mental Wealth assessment, we won’t know how we are tracking overall in transitioning to such an economy.

Furthermore, GDP only includes the value created by those in the labor market. The exclusion of socially productive activities sends a signal that society does not value the contributions made by those not in the formal labor market. Privileging employment as a legitimate social role and indicator of societal integration leads to the structural and social marginalization of the unemployed, older adults, and the disabled, which in turn leads to lower social participation, intergenerational dependence, and the erosion of mental health and well-being.

Well-being frameworks are an important evolution in our journey to understand national prosperity and progress in more holistic terms. Dashboards of 50-80 indicators like those proposed in Australia, Scotland, New Zealand, Iceland, Wales, and Finland include things like health, education, housing, income and wealth distribution, life satisfaction, and more, which help track some important contributors to social well-being.