Ready for the Next Threat: Creating a Commercial Public Health Emergency Payment System

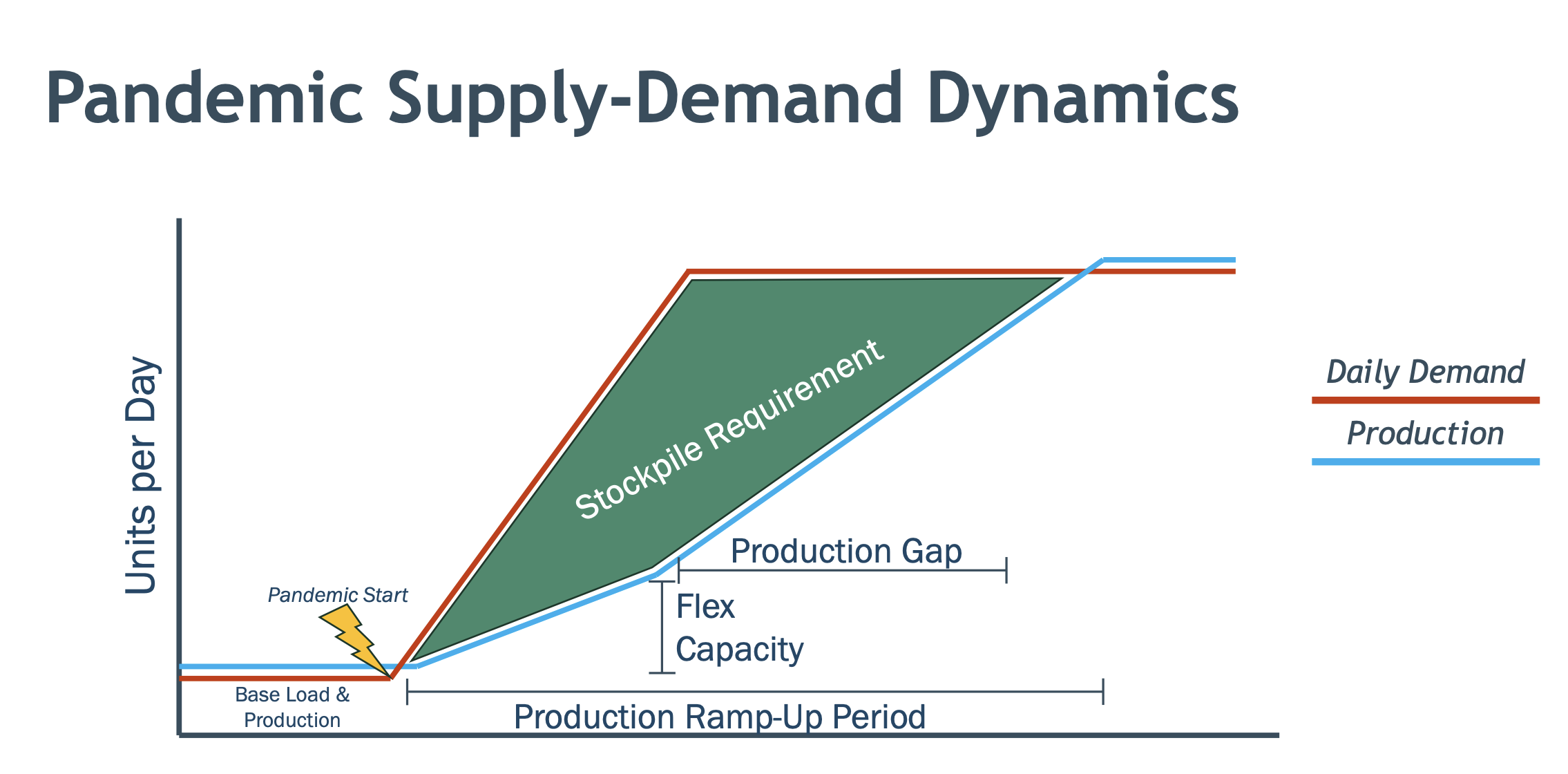

There are many examples of groundbreaking success in the development of life-saving vaccines, diagnostics, and therapeutics to which we can point in the response to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as the introduction of mRNA vaccines and the accelerated path to its authorization through Operation Warp Speed. However, in anticipation of future known and unknown health security threats, including new pandemics, biothreats, and climate-related health emergencies, our answers need to be much faster, cheaper, and less disruptive to other operations. One path to a more permanent state of readiness is to create a commercial public health emergency payment system to use the full power of commercial healthcare reimbursement, providing clear and tunable market signals to catalyze investment in anticipation and in response to public health emergencies.

Challenge and Opportunity

There are two key problems we have yet to solve. First, how do we break out of the panic/neglect cycle of investments in emergency medical countermeasures (MCMs), i.e invest more in prevention and preparedness than in response? Secondly, how can we avoid any friction in capital (both public and private) once there is an emergency, while preserving the ability to fine tune incentives as needs evolve?

Many of the most promising and impactful tools applicable to emerging infectious diseases and public health emergency (PHE) management more broadly (e.g. wastewater surveillance, home testing, vaccinations, improved indoor air quality), face strong headwinds due to small, poorly defined, and/or unstable markets, significantly reducing private investment in them and relying on seemingly stochastic public investments by a fragmented set of federal, state, and local agencies.

Additionally, there is a prevailing assumption within the health security community that it operates largely outside the commercial U.S. healthcare system due to lack of private incentives (as opposed to, for instance, the development and use of cancer therapies). This, however, reflects a policy decision and not fundamental underlying market demand. And yet there remain two key realities to contend with: pandemic-related demand is largely unpredictable, and we have, thus far, been unable to effectively amortize pandemic costs into interpandemic periods.

U.S. health care insurers process more than nine billion claims for payment each year – a process which features a sophisticated, standardized accounting system that is widely understood by the entire healthcare industry; it is also a powerful signal of future market expectations that drives private and public R&D investment decisions.

Plan of Action

The U.S. government should create a prospective healthcare reimbursement code set that can anticipate the need for any product or service in the context of PHEs, including MCMs and infrastructure-based countermeasures. The goal would be to provide clear market signals and pull incentives, to encourage and accelerate development and appropriate utilization of medical countermeasures (diagnostics, vaccines, therapies, early warning detection, and others). This would complement other strategies, such as advanced R&D investments made by federal funding agencies including the Biomedical Advanced Research & Development Authority (BARDA). Creating clear reimbursement pathways would likely immediately attract private investment in MCMs in ways that are notoriously difficult currently and help enable rapid response to public health emergencies.

The development and management of this reimbursement system should be housed within the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and would require introduction of legislation clearly authorizing CMS to pay for products and services under EUA and use of prospective payment policies.

There are a variety of additional benefits to using a payment system like this for emergency response. This system could be a unique and core source of surveillance data, through conditions of payment policies, that can be used to provide intelligence and manage evolving emergencies such as outbreaks and pandemics, significantly reducing the need for additional data collection systems – need which proved to be a major bottleneck during COVID-19. Prospective codesets are not common in public and private insurance, but the existence of them would likely serve as a new and powerful tool for private investment in a capability that would be certain to have public health benefit were it to exist.

We propose that reimbursable services be categorized into three tiers.

Tier 1. Existing and prospective medical products/services under FDA EUA

This is the set of regulated medical products that would typically be considered for emergency use authorization by the FDA. It can include infectious disease diagnostics, vaccinations, and therapeutics. It can even include the use of repurposed generic drugs to mitigate potential drug shortages.

Tier 2. Existing public health products/services typically not requiring FDA approvals, but may have other regulatory hurdles

There are a variety of products and services not considered medical products but nonetheless play critical roles not only in response but in prevention of public health emergencies. Many of these technologies struggle to find stable markets in which to operate and are relegated to the sidelines. This includes genomic surveillance, remnant sample sequencing, or other surveillance testing capabilities, early warning systems, use of commercial wearables as a check engine light for possible infection prior to symptom onset. Many of these technologies need to be “always on” to be most effective.

Tier 3. Prospective public health products/services typically not requiring FDA approvals, but may have other regulatory hurdles

This category deviates from current models of healthcare reimbursement, because it is comprised of interventions that are carried out by service providers outside of healthcare delivery, but which nonetheless have high impact potential. This can include indoor air quality upgrades, or wastewater detection. Again, the commercialization of indoor air quality is in part impeded by poorly defined markets.

Value-based care models

While the above items are largely “fee for service” payment models, we can also envision the use of value-based care models here, focusing on community outcomes and providing flexibility to communities or other systems to achieve them. This can include models to prevent hospitalization due to PHE (e.g. COVID-19), prevent community transmission (could be directed at local public health agencies or other agents), herd immunity vaccination rates, etc.

Conclusion

One of the biggest frustrations amongst the life science and medical device communities in the COVID-19 response was that the government was not clear about target product profiles and advanced market commitments for the full range of products and services needed. These types of systems, if implemented early, would have sent clear and powerful signals to the market that would have quickly unlocked the necessary private sector investment needed to expedite product development needed for the response. Using the already widely adopted and understood commercial healthcare reimbursement system to incentivize and pay for prospective emergency product development and delivery is a novel, powerful, and turnkey approach to pandemic preparedness.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Creating an HHS Loan Program Office to Fill Critical Gaps in Life Science and Health Financing

We propose the establishment of a Department of Health and Human Services Loan Programs Office (HHS LPO) to fill critical and systematic gaps in financing that prevent innovative life-saving medicines and other critical health technologies from reaching patients, improving health outcomes, and bolstering our public health. To be effective, the HHS LPO requires an authority to issue or guarantee loans, up to $5 billion in total. Federally financed debt can help fill critical funding gaps and complement ongoing federal grants, contracts, reimbursement, and regulatory policies and catalyze private-sector investment in innovation.

Challenge and Opportunity

Despite recent advances in the biological understanding of human diseases and a rapidly advancing technological toolbox, commercialization of innovative life-saving medicines and critical health technologies face enormous headwinds. This is due in part to the difficulty in accessing sustained financing across the entire development lifecycle. Further, macroeconomic trends such as non-zero interest rates have substantially reduced deployed capital from venture capital and private equity, especially with longer investment horizons.

The average new medicine requires 15 years and over $2 billion to go from the earliest stages of discovery to widespread clinical deployment. Over the last 20 years, the earliest and riskiest portions of the drug discovery process have shifted from the province of large pharmaceutical companies to a patchwork of researchers, entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, and supporting organizations. While this trend has enabled new entrants into the biotechnology landscape, it has also required startup companies to navigate labyrinthine processes of technical regulatory guidelines, obtaining long-term and risk-friendly financing, and predicting payor and provider willingness to ultimately adopt the product.

Additionally, there are major gaps in healthcare infrastructure such as lack of adequate drug manufacturing capacity, healthcare worker shortages, and declining rural hospitals. Limited investment is available for critical infrastructure to support telehealth, rural healthcare settings, biomanufacturing, and decentralized clinical trials, among others.

The challenges in health share some similarities to other highly regulated, capital-intensive industries, such as energy. The Department of Energy (DOE) Loan Program Office (LPO) was created in 2005 to offer loans and loan guarantees to support businesses in deploying innovative clean energy, advanced transportation, and tribal energy projects in the United States. LPO has closed more than $40 billion in deals to date. While agencies across HHS rely primarily on grants and contracts to deploy research and development (R&D) funding, capital-intensive projects are best deployed as loans, not only to appropriately balance risk between the government and lendees but also to provide better stewardship over taxpayer resources via mechanisms that create liquidity with lower budget impact. Moreover, private-sector financing rates are subject to market-based interest rates, which can have enormous impacts on available capital for R&D.

Plan of Action

There are many federal credit programs across multiple departments and agencies that provide a strong blueprint for the HHS LPO to follow. Examples include the aforementioned DOE Loan Programs Office, which provides capital to scale large-scale energy infrastructure projects using new technologies, and the Small Business Administration’s credit programs, which provide credit financing to small businesses via several loan and loan matching programs.

Proposed Actions

We propose the following three actions:

- Pass legislation authorizing the HHS LPO to make or guarantee loans supporting the development of critical medicines that serve unmet or underserved public health needs.

- Establish the LPO as a staffing division within HHS.

- Appropriate a budget to support the staffing and operations of the newly created HHS LPO.

Scope

Similar to how DOE LPO services the priorities of the DOE, the HHS LPO would develop strategy priorities based on market gaps and public health gaps. It would also develop a rigorous diligence process to prioritize, solicit, assess, and manage potential deals, in alignment with the Federal Credit Reform Act and the associated policies set forth by the Office of Management and Budget and followed by all federal credit programs. It would also seek companion equity investors and creditors from the private sector to create leverage and would provide portfolio support via demand-alignment and -generation mechanisms (e.g., advance manufacturing commitments and advanced market commitments from insurers).

We envision several possible areas of focus for the HHS LPO:

- Providing loans or loan guarantees to amplify investment funds that use venture capital or other private investment tools, such as early-stage drug development or biomanufacturing capacity. While these funds may already exist, they are typically underpowered.

- Providing large-scale financing in partnership with private investors to fund major healthcare infrastructure gaps, such as rural hospitals, decentralized clinical trial capacity, telehealth services, and advanced biomanufacturing capacity.

- Providing financing to test new innovative finance models, e.g. portfolio-based R&D bonds, designed to attract additional capital into under-funded R&D and lower financial risks.

Conclusion

To address the challenges in bringing innovative life-saving medicines and critical health technologies to market, we need an HHS Loan Programs Office that would not only create liquidity by providing or guaranteeing critical financing for capital-intensive projects but address critical gaps in the innovation pipeline, including treatments for rare diseases, underserved communities, biomanufacturing, and healthcare infrastructure. Finally, it would be uniquely positioned to pilot innovative financing mechanisms in partnership with the private sector to better align private capital towards public health goals.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The DOE LPO, enabled via the Energy Policy Act of 2005, enables the Secretary of Energy to provide loan guarantees toward publicly or privately financed projects involving new and innovative energy technologies.

The DOE LPO provides a bridge to private financing and bankability for large-scale, high-impact clean energy and supply chain projects involving new and innovative technologies. It also expands manufacturing capacity and energy access within the United States. The DOE LPO has enabled companies involving energy and energy manufacturing technologies to achieve infrastructure-scale growth, including Tesla, an electric car manufacturer; Lithium Americas Corp., a company supplying lithium for batteries; and the Agua Caliente Solar Project, a solar power station sponsored by NRG Solar that was the largest in the world at its time of construction.

The HHS LPO would similarly augment, guarantee, or bridge to private financing for projects involving the development and deployment of new and innovative technologies in life sciences and healthcare. It would draw upon the structure and authority of the DOE LPO as its basis.

The HHS LPO could look to the DOE LPO for examples as to how to structure potential funds or use cases. The DOE LPO’s Title 17 Clean Energy Financing Program provides four eligible project categories: (1) projects deploying new or significantly improved technology; (2) projects manufacturing products representing new or significantly improved technologies; (3) projects receiving credit or financing from counterpart state-level institutions; and (4) projects involving existing infrastructure that also share benefits to customers or associated communities.

Drawing on these examples, the HHS LPO could support project categories such as (1) emerging health and life science technologies; (2) the commercialization and scaling access of novel technologies; and (3) expanding biomanufacturing capacity in the United States, particularly for novel platforms (e.g., cell and gene therapies).

The budget could be estimated via its authority to make or guarantee loans. Presently, the DOE LPO has over $400 billion in loan authority and is actively managing a portfolio of just over $30 billion. Given this benchmark and the size of the private market for early-stage healthcare venture capital valued at approximately $20 billion, we encourage the creation of an HHS LPO with $5 billion in loan-making authority. Using proportional volume to the $180 million sought by DOE LPO in FY2023, we estimate that an HHS LPO with $5 billion in loan-making authority would require a budget appropriation of $30 million.

The HHS LPO would be subject to oversight by the HHS Inspector General, OMB, as well as the respective legislative bodies, the House of Representatives Energy and Commerce Committee and the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pension Committee.

Like the DOE LPO, the HHS LPO would publish an Annual Portfolio Status Report detailing its new investments, existing portfolio, and other key financial and operational metrics.

It is also possible for Congress to authorize existing funding agencies, such as BARDA, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), or the National Institutes for Health (NIH), with loan authority. However, due the highly specialized talent needed to effectively operate a complex loan financing operation, the program is significantly more likely to succeed if housed into a dedicated HHS LPO that would then work closely with the other health-focused funding agencies within HHS.

The other alternative is to expand the authority for other LPOs and financing agencies, such as the DOE LPO or the U.S. Development Finance Corporation, to focus on domestic health. However, that is likely to create conflicts of priority given their already large and diverse portfolios.

The project requires legislation similar to the Department of Energy’s Title 17 Clean Energy Financing Program, created via the Energy Policy Act of 2005 and subsequently expanded via the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022.

This legislation would direct the HHS to establish an office, presumably a Loan Programs Office, to make loan guarantees to support new and innovative technologies in life sciences and healthcare. While the LPO could reside within an existing HHS division, the LPO would most ideally be established in a manner that enables it to serve projects across the full Department, including those from the National Institutes of Health, Food and Drug Administration, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. As such, it would preferably not reside within any single one of these organizations. Like the DOE LPO, the HHS LPO would be led by a director, who would be directed to hire the necessary finance, technical, and operational experts for the function of the office.

Drawing on the Energy Policy Act of 2005 that created the DOE LPO, enabling legislation for the HHS Loan Programs office would direct the Secretary of HHS to make loan guarantees in consultation with the Secretary of Treasury toward projects involving new and innovative technologies in healthcare and life sciences. The enabling legislation would include several provisions:

- Necessary included terms and conditions for loan guarantees created via the HHS LPO, including loan length, interest rates, and default provisions;

- Allowance of fees to be captured via the HHS LPO to provide funding support for the program; and

- A list of eligible project types for loan guarantees.

Supporters are likely to include companies developing and deploying life sciences and healthcare technologies, including early-stage biotechnology research companies, biomanufacturing companies, and healthcare technology companies. Similarly, patient advocates would be similarly supportive because of the LPO’s potential to bring new technologies to market and reduce the overall Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) for biotechnology companies, potentially supporting expanded access.

Existing financiers of research in biomedical sciences technology may be neutral or ambivalent toward this policy. On one hand, it would provide expanded access to syndicated financing or loan guarantees that would compound the impact of each dollar invested. On the other hand, most financiers currently use equity financing, which enables the demand for a high rate of return via subsequent investment and operation. An LPO could provide financing that requires a lower rate of return, thereby diluting the impact of current financiers in the market.

Skeptics are likely to include groups opposing expansions of government spending, particularly involving higher-risk mechanisms like loan guarantees. The DOE LPO has drawn the attention of several such skeptics, oftentimes leading to increased levels of oversight from legislative stakeholders. The HHS LPO could expect similar opposition. Other skeptics may include companies with existing medicines and healthcare technologies, who may be worried about competitors introducing products with prices and access provisions that have been enabled via financing with lower WACC.

Slow Aging, Extend Healthy Life: New incentives to lower the late-life disease burden through the discovery, validation, and approval of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints

The world is aging. Today, some two thirds of the global population is dying from an age-related condition. Biological aging imposes significant socio-economic costs, increasing health expenses, reducing productivity, and straining social systems. Between 2010 and 2030, Medicare spending is projected to nearly double – to $1.2 trillion per year. Yet the costly diseases of aging can be therapeutically targeted before they become late-stage conditions like Alzheimer’s. Slowing aging could alleviate these burdens, reducing unpaid caregivers, medical costs, and mortality rates, while enhancing productivity. But a number of market failures and misaligned incentives stand in the way of extending the healthy lifespan of aging populations worldwide. New solutions are needed to target diseases before they are life-threatening or debilitating, moving from retroactive sick-care towards preventative healthcare.

The new administration should establish a comprehensive framework to incentivize the discovery, validation, and regulatory approval of biomarkers as surrogate endpoints to accelerate clinical trials and increase the availability of health-extending drugs. Reliable biomarkers or surrogate endpoints could meaningfully reduce clinical trial durations, and enable new classes of therapeutics for non-disease conditions (e.g., biological aging). An example is how LDL (a surrogate marker of heart health) helped enable the development of lipid-lowering drugs. The current lack of validated surrogate endpoints for major late-life conditions is a critical bottleneck in clinical research. Because companies do not capture the majority of the benefit from the (expensive) validation of biomarkers, the private sector under-invests in biomarker and surrogate endpoint validation. This leads to countless lives lost and to trillions of public dollars spent on age-related conditions that could be prevented by better-aligned incentives. It should be an R&D priority for the new administration to fund the collection and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints, then gain regulatory approval for them. As we explain below, the existing FNIH Biomarkers Consortium does not fill this role.

Currently, companies are understandably hesitant to invest in validation without clear rewards or regulatory pathways. The proposed framework would encourage private companies and laboratories to contribute their biomarker data to a shared repository. This repository would expedite regulatory approval, moving away from the current product-by-product assessment that discourages data sharing and collaboration. Establishing a broader pathway within the FDA for standardized biomarker approval would allow validated biomarkers to be recognized for use across multiple products, reducing the existing incentives to safeguard data while increasing the supply of validated biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. Importantly, this would accelerate the development of drugs which holistically extend the healthspan of aging populations in the U.S. by preventing instead of treating late-stage conditions. (Statins similarly helped prevent millions of heart attacks.)

Key players such as the FDA, NIH, ARPA-H, and BARDA should collaborate to establish a streamlined pathway for the collection and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints, allowing these to be recognized for use across multiple products. This initiative aligns with the administration’s priorities of accelerating medical innovation and improving public health with the potential to add trillions of dollars in economic value by making treatments and preventatives available sooner. This memo outlines a framework applicable to various diseases and conditions, using biological aging as a case study where the validation of predictive and responsive biomarkers may be vital for significant breakthroughs. Other critical areas include Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), where the lack of validated surrogate endpoints significantly hinders the development of life-saving and life-improving therapies. By addressing these bottlenecks, we can unlock new avenues for medical advancements that will profoundly improve public health and mitigate the fast-growing, nearly trillion-dollar Medicare spend on late-life conditions.

Challenge and Opportunity

By 2029, the United States will spend roughly $3 trillion dollars yearly – half its federal budget – on adults aged 65 and older. A good portion of these funds will go towards Medicare-related expenses that could be prevented. Yet the process of bringing preventative drugs to market is lengthy, costly, and currently lacking in commercial incentives. Even for therapeutics that target late-stage diseases, drug development often takes 10+ years and cost estimates range between $300 million to $2.8 billion. This extensive duration and expense are due, in part, to the reliance on traditional clinical endpoints, which require long-term observation and longitudinal data collection. The burden of chronic diseases is growing, and better biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are needed to accelerate the development of therapeutics that prevent non-communicable diseases and age-related decline. Chronological age, for instance, is a commonly used but inadequate surrogate marker for biological age. This means that, to date, clinical trials on therapeutics designed to improve the biology of aging take decades to validate, rather than years. As a result, pharmaceutical companies find more short-term rewards in treating late-stage diseases, since developing drugs that reduce overall age-related decline requires longer and currently uncertain endpoints.

The validation of reliable biomarkers and surrogate endpoints offers a promising solution to this challenge. Biological measures often correlate with and predict clinical outcomes, and can therefore provide early indications of whether a treatment is effective. If sufficiently predictive, biomarkers can serve as surrogate clinical endpoints, potentially reducing the duration and cost of clinical trials. Validated biomarkers must accurately predict clinical outcomes and be accepted by regulatory authorities, yet the validation process is underfunded due to insufficient commercial incentives for individual agents to share their biomarkers to be used as a public good. (From a purely financial standpoint, companies are better off targeting diseases with known endpoints.)

The most prominent existing efforts to advance biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are the Foundation for the National Institute of Health’s (FNIH) Biomarkers Consortium and the FDA’s Biomarker Qualification Program. Established in 2006, the Biomarkers Consortium is a public-private partnership aimed at advancing the development and use of biomarkers in medical research. Meanwhile, the FDA’s qualification program was the result of the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in 2016, which underscored the critical role biomarkers play in accelerating medical product development. The Act mandated the FDA to implement a more transparent and efficient process for biomarker qualification.

Despite the Consortium’s ambitious goals, the rate of biomarker qualification by the FDA has been slow. Since its inception in 2006, only a small number of biomarkers have been successfully qualified. This sluggish progress has been a source of criticism for stakeholders, especially given the high level of resources and collaboration involved. For example, the process of validating biomarkers for osteoarthritis under the Consortium’s “PROGRESS OA” project has been ongoing since Phase 1 and still faces hurdles before full qualification. We are of the view that this is the result of two issues. Firstly, the qualification process, which involves FDA approval, is seen as overly complex and time-consuming. Despite the 21st Century Cures Act aiming to streamline the process, resulting in the qualification pathway, it remains a significant challenge. The difficulty in navigating the regulatory landscape can limit the impact of Biomarkers Consortium (BC) projects. The Kidney Safety Project, for example, faced substantial regulatory hurdles before finally achieving the first qualification of a clinical safety biomarker. Secondly, even though the Consortium operates in a precompetitive space, there are ongoing challenges related to data sharing. Companies may still hesitate to share critical data that could advance biomarker validation out of concern for losing a competitive edge, which hampers collaboration. To address these issues, it is crucial to implement a framework that promotes data sharing in the academic and private sectors, providing strong incentives for the validation and regulatory approval of biomarkers, while improving regulatory certainty with a standardized regulatory process for surrogate endpoint validation.

The current boom in biotechnology underscores the urgency of addressing persisting inefficiencies. Without changes, we face a significant bottleneck in proving the efficacy of new drugs. This is exacerbated by Eroom’s Law—the observation that drug discovery is becoming slower and more expensive over time. This growing inefficiency threatens to hinder the development of new, life-saving treatments at a time when the American population is aging and rapid medical advancements are crucial to deter increasing medical and social costs. In just 11 years—between 2018 and 2029—the U.S. mandatory spending on Social Security and Medicare will more than double, from $1.3 trillion to $2.7 trillion per year. Yet the costly diseases of aging can be therapeutically targeted before they become late-stage conditions like Alzheimer’s. For federal policymakers, taking immediate action to improve data sharing and biomarker validation processes is vital. Failure to do so will not only stifle innovation but also delay the availability of critical therapies that could save countless lives and accelerate economic growth in the long run. Prompt policy intervention is essential to capitalize on the current advancements in biotechnology and ensure the development of new life-saving tests, tools, and drugs.

Implementing pull-incentives for data sharing now can help the United States adjust to its new demographic structure, where adults in advanced age prevail, while fertility rates decline. It can also mitigate the escalating costs and timelines of clinical trials, and accelerate the approval of life-saving, health-extending drugs. If our proposed framework is successfully implemented, a robust pool of biomarker data will be established, significantly facilitating the discovery and validation of biomarkers. This will result in several key advancements, including shortened clinical trial durations, increased R&D investment, faster drug approvals, and even increased drug efficacy. Additionally, new drug classes targeting non-disease endpoints, such as biological aging, could be developed. Just as the discovery of LDL as a surrogate marker of heart health was critical in enabling the testing and development of statins, the discovery of clinical-grade biomarkers may unlock new therapeutics designed to target the mechanisms that drive human aging, slowing down the progression of age-related diseases (like cancers) before they become deadly and socio-economically expensive.

Plan of Action

To address the challenge of inefficient data sharing, validation, and approval of biomarkers, we propose implementing a series of pull-incentives aimed at encouraging pharmaceutical companies to contribute their relevant biomarker data to a shared repository and undertake the necessary research and analysis for public validation. These validated biomarkers can then be formally accepted by regulators as surrogate endpoints for drug approval, accelerating the drug development process and reducing late-life costs.

Recommendation 1. An NIH-FDA initiative for Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints Within the NIA

Most existing agencies focus on single, often late-stage diseases. This is at odds with a holistic understanding of human biology. A new initiative within the National Institute on Aging (NIA) could be devoted to the discovery, collection, and validation of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints for overall human health and age-related decline. Most National Institutes of Health funds are currently devoted to the diseases of aging (think cancers, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, or Parkinson’s.) Within the NIA, research on Alzheimer’s disease alone receives roughly eight times more funding than the biology of aging, with few human-relevant results. Every federal agency and U.S. individual would benefit from better biomarkers of long-term health and from an understanding of how to measure the biology of aging. Yet no single agent has the incentives to collect and validate this data, for instance by shouldering the costs of validating predictive and responsive biomarkers of aging.

This new initiative could also be devoted to the development of preclinical, human-relevant methodologies that could broadly facilitate or streamline drug development. In 2022, the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 approved the use of in vitro and in silico New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like cell-based assays (e.g. organs-on-chips) or computer models (like virtual cells) in preclinical development to reduce or replace animal studies, especially “where no pharmacologically relevant animal species exists.” This may be the case for human aging, where no single animal model reflects the full complex biology of our aging process.

At present, these technologies cannot accurately represent the multifactorial processes of aging, and they cannot model entire organisms. Much work remains to be done to even understand how to “code” aging into organs-on-chips. Yet if supplemented by approaches like in vivo pooled screening, next generations of human-relevant in vitro or in silico methodologies (like virtual cells) could be infused with the complex data needed to accelerate clinical trial results and increase drug efficacy. For in vitro and in silico models to reproduce key aspects of aging biology, a better understanding of how human aging works in living organisms — and what markers to include to represent it either virtually or in vitro — may be needed. Yet pharmaceutical companies, startups, health insurance firms, and even research hospitals again lack the incentives to shoulder the costs of collecting and validating this type of data. This means a new office within a federal agency may be needed to supply these incentives.

Recommendation 2. New Data-sharing Incentives

The specific incentives used would need to be developed in collaboration with policymakers and industry stakeholders, but a few are outlined below:

Pull-incentives

One possibility is offering transferable Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs) or similar pull incentives to companies that share their biomarker data. PRVs are currently awarded by the FDA to companies developing drugs for neglected tropical diseases, rare pediatric diseases, or medical countermeasures. A PRV allows the holder to expedite the FDA review of another drug from 10 months to 6 months, and holds significant financial value. Offering transferable PRVs for drugs designed to target biological aging, for instance, could create the incentives needed for pharmaceutical companies to target early-stage age-related conditions before they turn into diseases.

The creation of a new PRV category would require legislative action. Our proposed NIH-FDA initiative would be well positioned to oversee the issuance of PRVs, working with government agencies and think tanks to determine, for instance, what an “aging therapeutic” means, and what a company needs to achieve to gain a PRV for a longevity drug. The Alliance for Longevity Initiatives, for instance, has developed an advanced approval pathway for health-extending drugs that directly target the biology of aging. Another possible strategy would be for the FDA to encourage drugs that target multiple disease indications at once, perhaps offering discounts or incentives for every extra biomarker or surrogate endpoint validated. This could effectively encourage the development of drugs that do more than marginally improve on existing interventions.

We acknowledge that an overabundance of PRVs can saturate the market, decreasing their value and weakening the intended pull-incentive for pharmaceutical innovation. A response would be to demand that proposals to issue additional PRVs include a comprehensive market impact analysis to mitigate unintended economic consequences. Expanding the number of PRVs can also place extra demands on the FDA’s limited resources, potentially leading to longer approval times for other essential medications, even though PRV holders often delay redemption, preventing an immediate influx of priority review applications. The PRV system may inadvertently favor larger, well-established pharmaceutical companies that have the means to acquire and leverage PRVs effectively, creating barriers for smaller firms and startups. These are all spill-over problems worth solving for the potential upshot of mitigating late-life disease costs and encouraging drugs that holistically improve the human healthspan.

Biomarker Data Sharing as a Condition of Federal Funding

Federal funding recipients are legally obligated to make their research publicly accessible through agency-specific policies aimed at advancing open science. This mandate was strengthened by the 2022 OSTP Memorandum. Despite this clear mandate, the implementation of public access policies has been uneven across federal agencies, with progress varying due to differences in resources, technical infrastructure, and agency-specific priorities. The 2022 OSTP Public Access Memorandum aims to accelerate agency efforts to enhance public access infrastructure and policies. This updated guidance presents an opportunity for agencies to not only meet immediate data-sharing requirements but also to expand policy scopes to include essential clinical data, such as biomarker data from clinical trials. To meet these goals, agencies should ensure that funding agreements explicitly require the publication of comprehensive biomarker data and that suitable repositories are available to store and share these critical datasets effectively.

Case Study: Project NextGen

A prime example of the potential success of such initiatives is Project NextGen, a program led by BARDA in collaboration with the NIH to advance the next generation of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments. As part of its vaccine program, Project NextGen includes centralized immunogenicity assays with the overarching goal of establishing correlates of protection, which could serve as surrogate biomarkers for next-gen vaccines. These assays are collected during Phase 2b vaccine studies sponsored by Project NextGen, which have been designed to measure a number of secondary immunogenicity endpoints including systemic and mucosal immune responses. Developers share their assays so that they can be used as a public good, in return for federal funding. This effort demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of a federally led effort to share assay data to advance biomarker validation and drug development.

Recommendation 3. Create and Manage a Data Repository

To enhance collaborative research and ensure the efficient use of publicly funded clinical data, we recommend establishing a secure data repository. This repository will serve as a centralized platform for data submission, storage, and access. Management of the repository could be undertaken by a federal agency, such as the NIH, leveraging their experience with the Biomarkers Consortium, perhaps in partnership with non-governmental organizations like the Biomarkers of Aging Consortium. Drawing from existing models, such as Project NextGen’s assay data management, can provide valuable insights into the implementation and operationalization of the repository.

The cost of establishing and maintaining this repository, including data storage, management, and access controls, would be dwarfed by the socio-economic returns it could provide. This repository can facilitate data sharing, protect sensitive information, and promote a collaborative environment that accelerates biomarker validation and approval, while ensuring pharmaceutical companies that their hard-earned data is safely stored.

The securely stored data in the repository would primarily be accessible to qualified researchers, clinicians, and policymakers involved in biomarker research and development, including academic researchers, pharmaceutical companies, and public health agencies. Access would be granted through an application and review process. The benefits of this repository are multifaceted: it accelerates research by providing a centralized database, enhances collaboration among scientists and institutions, increases efficiency by reducing redundancy and improving data management, ensures data security through robust access controls, offers cost-effectiveness with long-term socio-economic returns, and supports regulatory bodies with comprehensive data sets for more informed decision-making.

Recommendation 4. Create A Regulatory Pathway with Broader Application

To accelerate the adoption of validated biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development, we propose the creation of a streamlined regulatory approval process within the FDA. This new pathway would establish clear criteria and standardized procedures for biomarker evaluation and approval, facilitating their recognition for use across multiple products and therapeutic areas.

Currently, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) operates the Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP), which allows drug developers to seek regulatory qualification for specific contexts of use. While this program fosters collaboration between the FDA and external stakeholders, biomarkers are qualified on a case-by-case basis, limiting their broader applicability across different drug development programs.

Additionally, the FDA maintains a Table of Surrogate Endpoints that have been used as the basis for drug approvals under the accelerated approval pathway. However, this table primarily serves as a reference and does not comprehensively address the need for a streamlined approval process for biomarkers and surrogate endpoints.

By developing a framework that moves away from traditional product-by-product assessments, the FDA could reduce existing barriers to biomarker and surrogate endpoint discovery and approval. This approach would encourage data sharing and collaboration among pharmaceutical companies and research institutions, leading to faster validation and broader acceptance of these critical tools in drug development.

This proposal builds upon existing legislative efforts, such as the 21st Century Cures Act of 2016, which includes provisions to accelerate medical product development and supports the use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in the regulatory process. Furthermore, it aligns with the FDA’s ongoing efforts to provide clarity on evidentiary criteria for biomarker qualification, as outlined in the 2018 guidance document “Biomarker Qualification: Evidentiary Framework.”

Inspiration for this approach can be drawn from the Advanced Approval Pathway for Longevity Medicines (AAPLM) proposed by the Alliance for Longevity Initiatives (See AAPLM-Whitepaper). The AAPLM includes provisions such as a special approval track, a priority review voucher system, and indication-by-indication patent term extensions, which align economic incentives with the transformative health improvements that longevity medicines can provide. These measures offer a valuable template for facilitating the recognition and approval of biomarkers. Adding to the existing FDA table of surrogate endpoints that can serve as the basis for drug approval or licensure, and referencing existing collaborations between the NIH and FDA, such as the Biomarkers Consortium, can provide a robust foundation for new biomarker evaluations. Ultimately, this regulatory innovation will support the development of life-saving drugs, enhance public health outcomes, and meaningfully contribute to economic growth by bringing effective treatments to market more quickly.

Conclusion

Today, over two thirds of all deaths in the United States are the result of an age-related condition. The burden of non-communicable diseases is growing, and better biomarkers and surrogate endpoints are needed to target diseases before they are life-threatening or debilitating. The next administration should implement a comprehensive framework to promote data sharing and incentivize the validation and regulatory approval of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. This aligns directly with the administration’s goal to make Americans healthy. These solutions can substantially reduce the duration and cost of clinical trials, accelerate the development of life-saving drugs, and improve public health outcomes. It is possible and necessary to create an environment that encourages and rewards pharmaceutical companies to share crucial data that accelerates medical innovation. By discovering and validating predictive and responsive biomarkers of health and disease, new therapeutic classes can be developed to directly target biological aging and prevent most forms of cancers, heart disease, frailty, vulnerability to severe infection, and Alzheimer’s. This will enable the United States to remain at the forefront of medical research, and to respond to the growing demographic crisis of aging populations in declining health.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

A number of market failures stand in the way of the discovery and validation of predictive, reliable, and responsive biomarkers. First, it’s currently expensive to test drugs in multiple disease indications, which means pharmaceutical companies are often incentivized to focus on late-stage diseases (e.g. delaying death by a terminal cancer by three months), since this drug class is more easily and quickly trialed. The FDA also strongly assumes that a treatment ought to modulate a single outcome. (Think life/death; heart disease/no heart disease.) Therapeutics that target biological aging, for instance, would take decades to test without validated biomarkers or widely accepted surrogate endpoints.

Aging research, for instance, has seen a 70-fold increase in venture capital funding since the last decade. Yet so far—and this is a critical asterisk—misaligned commercial incentives have mostly optimized for unproven supplements, imprecise biological-age-tracking apps, and unsafe experimental therapies or cosmetics. The most well-meaning investors and founders in “longevity” often end up developing drugs for single disease indications (like osteoarthritis, or obesity) to avoid bankruptcy or as a path to self-fund their intent of developing drugs that more holistically target the mechanisms that drive aging. arket incentives need to be aligned to the pressing social needs these therapeutics could respond to.

The federal government is uniquely positioned to coordinate large-scale initiatives that require significant resources and regulatory oversight. While private sector companies play crucial roles in drug development, they often lack the incentives to self-coordinate and the authority to drive comprehensive data-sharing and biomarker validation efforts.

Cohesion from data-collection to regulatory approval of biomarkers is going to be key if surrogate endpoints are actually going to be adopted. Having the federal government oversee all stages will ensure this cohesion.

The Biomarkers Consortium has made meaningful strides in advancing biomarker research, but they have not succeeded in acquiring sufficient data. The consortium relies on voluntary, precompetitive collaboration without providing strong financial or legislative incentives for data sharing. It does not maintain a centralized, secure data repository, and struggles with fragmented data sharing. It also lacks influence over the FDA’s biomarker qualification process, which remains complex and time-consuming. This has resulted in slow progress due to hesitancy from private entities to share valuable data. Our solution differs by directly addressing this data-sharing hurdle through a series of targeted incentives that reduce the case-by-case assessment currently required, and enable broader application of validated biomarkers across multiple drugs and therapeutic areas.

By introducing legislative changes to authorize patent extensions and expand Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs), we create compelling reasons for companies to share their data. Additionally, our proposal includes the development of a centralized data repository with a streamlined regulatory approval process, inspired by the Advanced Approval Pathway for Longevity Medicines (AAPLM). This approach not only incentivizes data sharing but also provides a clear and efficient pathway for biomarker validation and regulatory acceptance. By leveraging existing frameworks and offering tangible rewards, our solution proposes an increase in incentives, to match the socioeconomic benefits that may be unlocked by more accessibility to the wealth of existing but undersupplied biomedical data.

The FDA’s Accelerated Approval Pathway is indeed a valuable tool that allows for the approval of drugs based on surrogate endpoints that are reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. This pathway requires substantial evidence showing that these surrogate endpoints are linked to clinical outcomes, usually gathered from rigorous clinical trials. However, it typically applies to surrogate endpoints validated for specific uses or products. Our goal is to establish a new pathway that supports the validation and use of surrogate endpoints across multiple products. By validating biomarkers that can be used across various drugs, we can streamline the drug development process, reducing the time and cost associated with bringing new therapies to market. This broader approach would enhance efficiency, reduce drug development time and costs, and promote innovation by encouraging pharmaceutical companies to invest in research, knowing that successful biomarkers can have wide-reaching applications.

Pharmaceutical companies could push back on this proposal due to concerns over losing their competitive advantage by sharing proprietary data. They might reasonably fear that sharing valuable biomarker data could erode their market position and intellectual property. By involving pharmaceutical companies in the development of the proposal, we can better understand their concerns and tailor incentives accordingly. One effective strategy would be to offer significant financial incentives, such as Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs) or patent term extensions to companies that share their data. These incentives can offset the perceived risks and provide tangible benefits that make data sharing more attractive. By making PRVs transferable and offering additional incentives to small biotechnology companies, this policy can be implemented without overly favoring large pharmaceutical companies. Another possible strategy would be for the FDA to encourage drugs that target multiple disease indications at once, perhaps offering discounts or incentives for every extra biomarker or surrogate endpoint validated. Fostering a collaborative environment where the benefits of shared data (such as accelerated drug approvals and reduced R&D costs) are clearly communicated can reduce hurdles. Engaging economists to quantify the long-term economic gains to individual pharmaceutical companies as well as to society, while demonstrating how shared data can lead to industry-wide advancements, can further encourage participation. By providing competitive enough incentives, a framework can be created that balances the interests of pharmaceutical companies with the broader goal of advancing medical innovation and public health.

The first step to get this proposal off the ground is to introduce legislative changes that authorize patent extensions and expand the eligibility for Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs). These legislative changes will create the necessary incentives for pharmaceutical companies to participate in the program by offering tangible benefits that offset the risks associated with data sharing.

Simultaneously, developing and launching a pilot program for the centralized data repository is crucial. This pilot should focus on a specific subset of biomarkers for high-priority diseases and non-disease indications to demonstrate the feasibility and benefits of the proposed framework. By starting with a targeted approach, we can gather initial data, test the processes, and make any necessary adjustments before scaling up the program. This pilot will not only help in garnering support from stakeholders by showcasing the practical benefits of the framework but also refine the approach based on real-world feedback, ensuring a smoother and more effective broader implementation.

Similar efforts in the past have often been hindered by a lack of incentives for data sharing and collaboration, along with fragmented regulatory processes. Our proposal aims to overcome these obstacles by introducing strong incentives which will encourage companies to share their data. Moreover, we propose creating a standardized regulatory pathway for biomarker approval, which will streamline the process and reduce fragmentation. By involving key federal agencies, we ensure a coordinated and comprehensive implementation, thus avoiding the pitfalls that have doomed past efforts.

The status quo is unacceptable. Millions of lives are lost or debilitated every year due to the slow and costly process of bringing new drugs to market, which is hindered by the lack of validated biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. The recommended course of action leverages existing regulatory frameworks and incentives that have proven effective in other contexts, such as the use of Priority Review Vouchers (PRVs) for neglected tropical diseases. By adapting these mechanisms to encourage data sharing and biomarker validation, we can build on established successes while addressing the specific challenges of the current drug development landscape.

This approach ensures that we utilize proven strategies to accelerate drug development and approval, reducing the overall time and cost associated with clinical trials. By fostering a collaborative environment and providing tangible incentives, we can significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of the drug development process. This targeted strategy not only addresses the immediate needs but also sets a foundation for continuous improvement and innovation in the field of medical research, ultimately saving lives and improving public health outcomes.

Establishing a National Water Technology Pipeline

The next administration should establish a National Water Technology (Pipeline) to spur the innovation and commercialization of water technologies. The Pipeline should be designed to:

- Proactively deploy broad-spectrum monitoring and treatment technologies nationwide to avoid the devastating societal impacts of water contaminants.

- End significant sanitary sewer overflows that pose risks to human and environmental health.

- Ensure that every community in America has access to affordable and safe drinking water.

A National Water Technology Pipeline would mobilize American entrepreneurs and manufacturers to lead on research and development of the next generation of solutions in water treatment, monitoring, and data management. The Pipeline would facilitate commercialization of later-stage water technologies by identifying innovative next-to-market solutions, proving technology through competitive demonstration projects, and deploying market-ready technology at full scale with federal funding support. An underlying objective of the Pipeline would be to improve water quality and access in the United States while addressing mounting infrastructure and maintenance costs. The Pipeline would also place an emphasis on training the next generation of technology-focused water professionals and strengthening community engagement and customer service.

Modernizing the water sector will require the federal government to renew its commitment to investing in water. In recent years, the water sector received only 4% of its funding from the federal government: a far lower fraction than other infrastructure sectors, such as highways (25%), mass transit and rail (23%), and aviation (45%). The funding injection from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) has provided a temporary step-change in federal investment, but the substantial gap in funding is still anticipated to grow. Increasing federal funding for water technology advancement even by a percentage point would have hugely beneficial impacts. By dedicating 1% of projected water infrastructure costs for a “good state of repair”—an estimated $12 billion over the next 10 years—the next administration can build a robust National Water Technology Pipeline, ushering in a new era of water and sanitation technologies. A similar scale of investment, $25 billion over 10 years for clean energy demonstrations, was authorized through BIL for the Department of Energy (DOE).

Challenge and Opportunity

The next administration will inherit water and wastewater infrastructure that the American Society of Civil Engineers has given a C- and D+ rating, respectively in 2021, which is essentially unchanged from the prior D and D+ rating in 2017. Much of the water and wastewater infrastructure across the United States is more than half a century old. These infrastructure assets are showing signs of significant deterioration and displaying strong risks of failure as they approach the end of their service lives. Put simply, many U.S. water systems are not equipped to handle emerging treatment requirements and increasing severe weather challenges.

We cannot address our nation’s water infrastructure crisis without addressing water infrastructure funding for modern systems. One problem is that federal water infrastructure funding has simply dried up. In the 1970s and early 1980s, federal funding accounted for 15–30% of water infrastructure funding nationwide. This fraction has recently declined to a baseline of only 4%, far lower than other infrastructure sectors. Municipalities have been forced to raise local water rates to cover the funding gap. Access to adequate supplies of clean water is quickly becoming unaffordable for many Americans as a result, and recent polls show that the percentage of voters who find their water service unaffordable is on the rise. The inadequacy of current investment in water is both perception and reality.

A second problem is the growing cost of operating and maintaining water infrastructure. Nearly three-quarters of the public spending in the water sector supports operations and maintenance water systems, often legacy facilities. EPA conservatively estimates expenditures of $1.2 trillion over the next 20 years are needed just to maintain legacy drinking water ($625B) and wastewater ($630B) systems at current levels of service, without any modernization. Moreover, the U.S. water sector is large and complex, including over 50,000 community water systems and 16,000 sanitary sewer systems nationwide. Such a balkanized system makes it difficult to transfer innovative experiences and funding strategies across jurisdictional boundaries.

These challenges were exacerbated by the financial stresses and widespread supply chain challenges that the COVID-19 pandemic placed on municipalities. COVID-19 highlighted water treatment as an essential service. Serving as one of the most important tools we have for reducing the spread of infectious disease, clean water merits robust federal investment. COVID-19 also highlighted the usefulness of wastewater collection systems as early warning detection systems via wastewater-based epidemiology. Had there been investment in these wastewater based monitoring systems over the previous decade, the tracking of COVID-19 would have been significantly improved. The water industry is also vital to operations of other sectors essential to human health, environmental health, energy production, and transportation. Every dollar invested in drinking water and wastewater infrastructure increases GDP by $6.35, creates 1.6 new jobs, and provides $23 in public health-related benefits. Investing in the water sector is investing in the U.S. economy. The United States is lagging behind many other countries in dealing with issues as wide ranging as water-loss reduction, asset management, customer engagement, and customer service. It is past time to catch up.

The next administration should view these challenges as opportunities. Much has changed for the water sector in the last four years including the rise to prominence of artificial intelligence and machine learning capabilities, increased availability of low-cost sensors, widespread use of wastewater-based epidemiology as an early warning system for health risks, and rising challenge of malevolent cybersecurity threats from bad actors. Instead of propping up aging facilities, the next administration can incentivize investment into—and demonstration of—the most advanced and efficient water systems. Moreover, the next administration can incentivize the deployment of advanced monitoring and analytic technologies to proactively evaluate equipment health and develop a data-driven schedule for infrastructure replacement instead of ad hoc upgrades. The recent BIL funding provides an example of a historic $15B water infrastructure investment to replace lead pipes nationwide. While some innovative construction methods are being utilized, the water sector still lacks a suitable technology solution for the non-invasive identification of buried lead pipes, this is exactly the type of challenge a Technology Pipeline could address. Establishing a National Water Technology Pipeline will help unify our nation’s water sector and create pathways to expedite the installation of modern systems instead of maintaining outdated legacy technologies.

The next administration should empower the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in the Department of Commerce to lead this Pipeline development. (Isn’t the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in charge of water quality for the United States? See FAQs.) With the recent expansion of capabilities afforded by the CHIPS and Science Act, NIST is better positioned now more than ever to facilitate validation of new breakthroughs in low-cost sensors, data management and analytics, internet of things (IOT), predictive analysis, and machine learning and other technologies that are proving capable of significant productivity gains for water utilities and can prevent catastrophic system failures. As an example, modern sensor and data solutions have been demonstrated to reduce the historical challenge of sanitary sewer overflows by optimizing existing sewer networks. Further advances could even enable real-time monitoring of lead, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and other contaminants. Operational and maintenance savings realized from these technological solutions can be directly reinvested into infrastructure needs and/or used to subsidize water costs for low-income customers. The growth of the semiconductor manufacturing sector and water-intensive microchip facilities are also closely linked to water and wastewater infrastructure and NIST can play a part in driving those solutions. NIST can also engage in interagency initiatives with the DOE to address specific water-energy nexus challenges

Plan of Action

The next administration should set the United States on a path to build the most advanced water systems in the world by launching a new National Water Technology Pipeline initiative. The Pipeline would accelerate adoption of existing “market-ready” solutions from around the world while also fostering the development of next-generation technologies by American innovators. The Pipeline should be structured around three main goals:

- Proactively deploying broad-spectrum monitoring and treatment technologies nationwide to avoid the devastating societal impacts of water contaminants.

- Ending significant sanitary sewer overflows that pose risks to human and environmental health.

- Ensuring that every community in America has access to affordable and safe drinking water.

Achieving these goals will require a multi-pronged approach, as described below.

New Public-Private Frameworks to Enable Innovation

NIST should lead a new collaborative effort aligned with the Department of Commerce’s mission to “promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness” in the water sector. Specifically, NIST should partner with industry leaders from utilities, vendors, equipment manufacturers, and system designers to develop a unified framework for deploying new technologies in the water sector. The framework would include verification and provisional standards to allow utilities to more easily adopt new technologies and to open the market for private investment in public water infrastructure. These efforts could be modeled after NIST efforts on the Manufacturing USA program or DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED).

Technology Demonstration and Deployment Network

Congress should appropriate 1% of the projected total water infrastructure costs each year for the next 10 years to support water innovation. Specifically, these monies would be used for competitive grants (administered by NIST) to assist “early adopter” water utilities in deploying improved technologies, to fund state-based water innovation councils, and to support small manufacturers innovating in the water sector. NIST would coordinate with state, county, and local utilities, industry associations and professionals, and manufacturers to facilitate identification, testing, validation, and adoption of viable technology solutions. A similar development and dissemination strategy has successfully accelerated innovation in the transportation sector. NIST can also help lower risk associated with technology piloting by borrowing from the emerging piloting models in the water sector including the Isle Utilities “Trial Reservoirs” and WaterStart “CHANNELS” programs

Education, Workforce, and Community Engagement

Innovation in theory cannot become innovation in practice without a well-trained, certified workforce to implement new solutions. Now more than ever, Americans are in need of well-paying jobs. A new water workforce will provide job opportunities in every county in the nation. The next administration can begin retraining workers into tech-savvy water professionals immediately through programs like the National Science Foundation’s Advanced Technological Education program and the Department of Defense’s SkillBridge program.

Over the last three decades, the federal government has abdicated its responsibility for funding the water sector, leaving states and local utilities to tackle new treatment challenges, deal with the impacts of climate change, and overcome catastrophic events like the COVID-19 pandemic. The next Administration can reinvest in U.S. water systems and bolster our economy by empowering NIST to spearhead a Pipeline to deliver modern solutions for modern water obstacles.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

To meaningfully modernize U.S. water systems, the federal government should directly invest 1% of projected water infrastructure funding needs (about $12 billion over the next 10 years) into innovative water technology solutions. For comparison, recent investments into energy infrastructure such as DOE’s clean energy demonstrations have received $25 billion over the next 10 years. Federal spending on water infrastructure is nowhere near other peer infrastructure sectors and an order of magnitude lower than it is for the transportation sector.

The water sector is strongly influenced by federal regulations that maintain minimum drinking-water and wastewater treatment standards. Where existing treatment standards can be met with legacy technologies, there is little incentive for utilities to invest in newer, advanced systems. Furthermore, evaluation and approval of new technologies typically occurs on a state-by-state basis, where differing state regulatory requirements inhibit the dissemination of successful solutions across jurisdictional boundaries. These barriers mean that useful new technologies can take as long as a decade to see widespread deployment in the water sector.

Funding support allocated through the Pipeline will de-risk investment by individual water utilities and enable those utilities to adopt new technologies and upgrade to newer systems more easily and efficiently. The uptake of new technologies will in turn increase demand for new water innovations, creating market opportunities for U.S. start-ups and entrepreneurs. Overall, the Pipeline will increase public health protections through deployment of advanced treatment systems and monitoring solutions while also attracting additional private investment in the water sector.

The Pipeline will expedite development of new treatment technologies, monitoring systems, and cost-saving strategies, and will enable these solutions to be deployed at local utilities much more quickly. The Pipeline will support promising innovations and fund demonstration projects to increase the availability and visibility of vetted technology solutions for large and small utilities alike. Emphasis could and should be placed on accelerating technologies that solve challenges in rural communities, overburdened communities, communities with declining populations, and other underserved communities.

The Pipeline will require leadership and expertise from an agency focused on public-private partnerships and job creation. The DOC’s mission is “to promote job creation, economic growth, sustainable development, and improved living standards for all Americans by working in partnership with businesses, universities, communities, and workers.” NIST, within the DOC, is well positioned to support standards development, fund technology evaluations, support small manufacturers, and develop public-private partnership consortia. DOC would coordinate with EPA experts as needed to evaluate public health impacts and/or environmental compliance.

The Clean Water and Drinking Water State Revolving Funds (SRFs) are designed to provide some funding directly to states – and then subsequently to utilities – to support local infrastructure projects through loans and grants. This process is not well suited for the funding of demonstration projects nor rapid sharing of solutions both regionally and nationally. The purpose of the Pipeline, by contrast, would be to identify new technologies that solve immediate and emerging broad challenges facing utilities across the nation, and to directly fund projects or consortia. Technologies identified through the Pipeline could ultimately be incorporated into SRF projects where appropriate.

Promoting Fairness in Medical Innovation

There is a crisis within healthcare technology research and development, wherein certain groups due to their age, gender, or race and ethnicity are under-researched in preclinical studies, under-represented in clinical trials, misunderstood by clinical practitioners, and harmed by biased medical technology. These issues in turn contribute to costly disparities in healthcare outcomes, leading to losses of $93 billion a year in excess medical-care costs, $42 billion a year in lost productivity, and $175 billion a year due to premature deaths. With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, there’s a risk of encoding and recreating existing biases at scale.

The next Administration and Congress must act to address bias in medical technology at the development, testing and regulation, and market-deployment and evaluation phases. This will require coordinated effort across multiple agencies. In the development phase, science funding agencies should enforce mandatory subgroup analysis for diverse populations, expand funding for under-resourced research areas, and deploy targeted market-shaping mechanisms to incentivize fair technology. In the testing and regulation phase, the FDA should raise the threshold for evaluation of medical technologies and algorithms and expand data-auditing processes. In the market-deployment and evaluation phases, infrastructure should be developed to perform impact assessments of deployed technologies and government procurement should incentivize technologies that improve health outcomes.

Challenge and Opportunity

Bias is regrettably endemic in medical innovation. Drugs are incorrectly dosed to people assigned female at birth due to historical exclusion of women from clinical trials. Medical algorithms make healthcare decisions based on biased health data, clinically disputed race-based corrections, and/or model choices that exacerbate healthcare disparities. Much medical equipment is not accessible, thus violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. And drugs, devices, and algorithms are not designed with the lifespan in mind, impacting both children and the elderly. Biased studies, technology, and equipment inevitably produce disparate outcomes in U.S. healthcare.

The problem of bias in medical innovation manifests in multiple ways: cutting across technological sectors in clinical trials, pervading the commercialization pipeline, and impeding equitable access to critical healthcare advances.

Bias in medical innovation starts with clinical research and trials

The 1993 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act required federally funded clinical studies to (i) include women and racial minorities as participants, and (ii) break down results by sex and race or ethnicity. As of 2019, the NIH also requires inclusion of participants across the lifespan, including children and older adults. Yet a 2019 study found that only 13.4% of NIH-funded trials performed the mandatory subgroup analysis, and challenges in meeting diversity targets continue into 2024 . Moreover, the increasing share of industry-funded studies are not subject to Revitalization Act mandates for subgroup analysis. These studies frequently fail to report differences in outcomes by patient population as a result. New requirements for Diversity Action Plans (DAPs), mandated under the 2023 Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act, will ensure drug and device sponsors think about enrollment of diverse populations in clinical trials. Yet, the FDA can still approve drugs and devices that are not in compliance with their proposed DAPs, raising questions around weak enforcement.

The resulting disparities in clinical-trial representation are stark: African Americans represent 12% of the U.S. population but only 5% of clinical-trial participants, Hispanics make up 16% of the population but only 1% of clinical trial participants, and sex distribution in some trials is 67% male. Finally, many medical technologies approved prior to 1993 have not been reassessed for potential bias. One outcome of such inequitable representation is evident in drug dosing protocols: sex-aware prescribing guidelines exist for only a third of all drugs.

Bias in medical innovation is further perpetuated by weak regulation

Algorithms