Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

Photo Depicts Potential Nuclear Mission for Pakistan’s JF-17 Aircraft

Due to longstanding government secrecy, analyzing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program is fraught with uncertainties. While it is known that Pakistan–along with many other nuclear-armed states–is modernizing its nuclear capabilities and fielding new weapons systems, little official information has been released regarding these plans or the status of its arsenal.

One of the many questions researchers have been asking concerns the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and its associated air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM). It has been long assumed that the Mirage III and Mirage V fighter bombers are the two aircraft with a nuclear delivery role in the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). The Mirage V is thought to have a strike role with Pakistan’s limited supply of nuclear gravity bombs, while the Mirage III has been used to conduct test launches of Pakistan’s dual-capable Ra’ad-I (Hatf-8) ALCM, as well as the follow-on Ra’ad-II. The Ra’ad ALCM was first tested in 2007 and has since remained Pakistan’s only nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missile.

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) reported in 2017 that the Ra’ad cruise missile was “conventional or nuclear,” a term normally used to describe a dual-capable system.

In order to retire its aging Mirage III and V aircraft and bolster defense production, Pakistan has procured over 130 operational JF-17 aircraft–which are jointly produced with China–and plans to acquire more in the future. During the 2024 Pakistan Day Parade, the PAF also announced a JF-17 PFX (Pakistan Fighter Experimental) project to maximize the operational lifespan and modernize the capabilities of the JF-17 aircraft.

Over the past few years, several reports have suggested Pakistan may incorporate the dual-capable Ra’ad ALCM onto the JF-17 so that the newer aircraft could eventually take over the nuclear strike role from the Mirage III/Vs. However, little information has been revealed about the status of this procurement and whether the JF-17s will replace the Mirage III and Vs in the nuclear mission. That is, until March 2023, when an aviation photographer captured an image that could help answer some of these lingering questions.

A possible new nuclear mission

During rehearsals for the 2023 Pakistan Day Parade (which was subsequently canceled), an image surfaced of a JF-17 Thunder Block II carrying what was reported to be a Ra’ad ALCM. Notably, this was the first time such a configuration had been observed in public.

Photo credit: Rana Suhaib/Snappers Crew

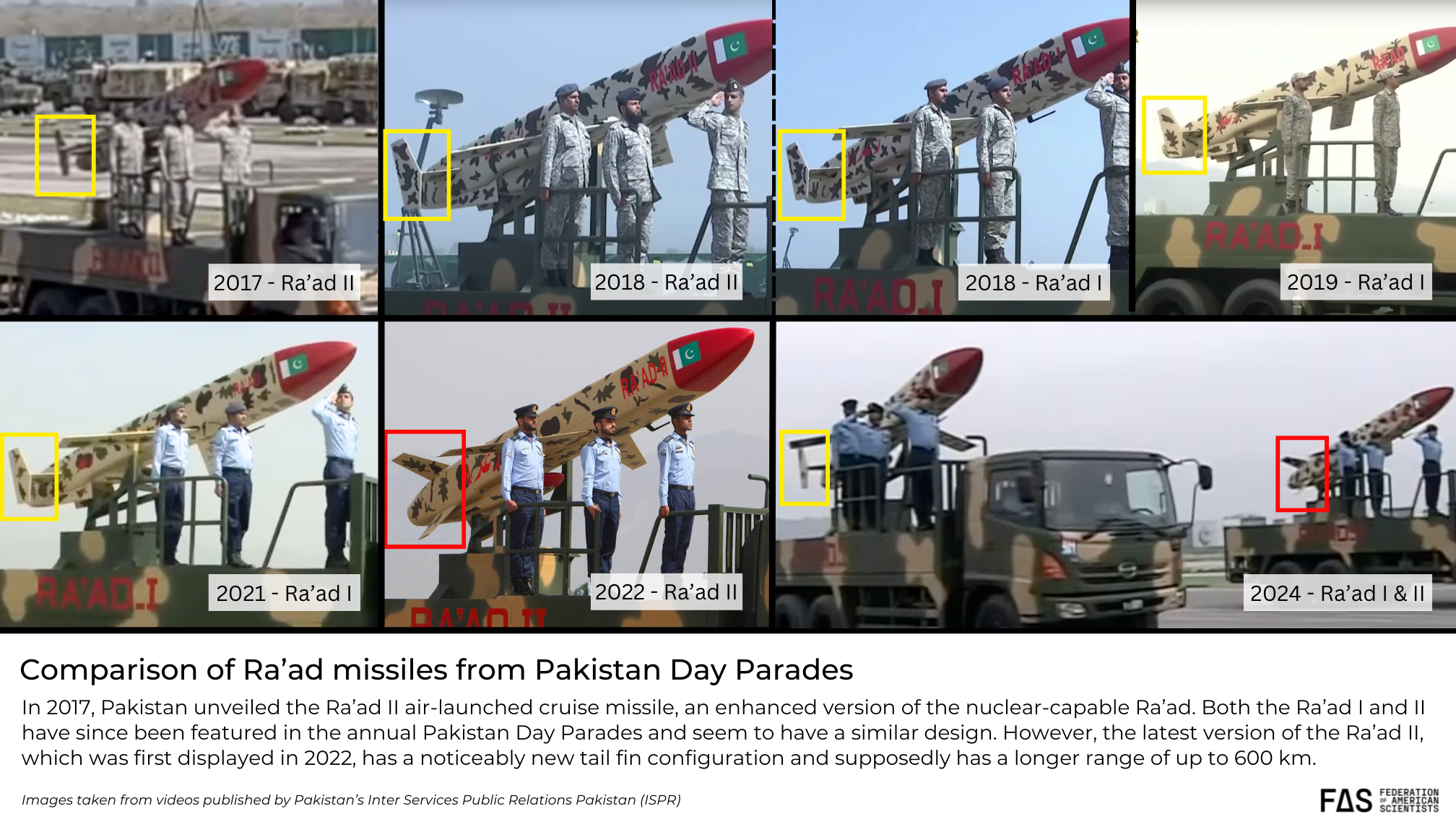

FAS was able to purchase the original image. To try and ascertain which type of Ra’ad is in the JF-17 image–the original Ra’ad-I or the extended-range Ra’ad-II–we compared it to other Ra’ad-I and -II missiles displayed in the 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2024 Pakistan Day Parades (the parades in 2020 and 2023 were canceled) where the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II were showcased alongside other nuclear-capable missiles such as the Nasr, Ghauri, Shaheen-IA and -II, as well as the Babur-1A.

Between 2017–when the Ra’ad-II was first publicly unveiled–and 2022, there were very few observable differences between the Ra’ad-I and -II. During this period, both missiles featured a new engine air intake, and although the Ra’ad-II was presented as having nearly double the range capability, this was not clearly observable through external features.

In 2017, Pakistan unveiled the Ra’ad Il air-launched cruise missile, an enhanced version of the nuclear-capable Ra’ad. Both the Ra’ad I and II have since been featured in the annual Pakistan Day Parades and seem to have a similar design. However, the latest version of the Ra’ad II, which was first displayed in 2022, has a noticeably new tail fin configuration and supposedly has a longer range of up to 600 km.

However, in 2022, a new version of the Ra’ad-II was displayed at the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Notably, this new version had an ‘x-shaped’ tail fin configuration as opposed to the other ‘twin-tail’ configurations seen in previous versions of the missile. The subsequent 2024 Pakistan Day parade also showcased the two distinct versions of the Ra’ad with their respective tail fin arrangements.

The fin arrangements of the photographed missile on the JF-17 appear to more closely match the ‘twin-tail’ configuration of the Ra’ad-I, rather than the newer ‘x-shaped’ tail of the Ra’ad-II, especially since it is unlikely that an outdated version of the Ra’ad II would be utilized in a flight test intended to demonstrate state-of-the-art capabilities.

Pakistan is also developing a conventional, anti-ship variant of the Ra’ad ALCM, known as Taimoor, that can be launched from the JF-17. Photos of the missile indicate that the two designs are highly similar, although the Taimoor missile also appears to include an ‘x-tail’ fin configuration, and its length is reported to be 4.38 meters. The ‘x-tail configuration’ would appear to indicate that the missile photographed on the JF-17 was not the Taimoor; however, for additional clarity, we measured multiple parade images of both versions of the Ra’ad and compared their lengths to that of the photographed missile.

We took an image of the Ra’ad-I from the 2019 Pakistan Day Parade and used the Vanishing Point feature in Photoshop to add gridded planes that simulate a 3D space in order to account for the angle at which the image was taken and the depth at which the missile sits compared to the side of the truck. After finding the make and model of the vehicle carrying the missile (which appears to be an early version of the Hino 500 Series FM 2630), we used the truck’s trailer axle spread of approximately 1.3 meters and wheelbase of 4.24 meters reference values and used Photoshop’s measuring tool to render an approximate length. We found it to be around 4.9 meters.

To estimate the dimensions of the Ra’ad-II, we started with a photo from the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Using the same methodology with Photoshop’s Vanishing Point tool to account for the angle of the photo and the distance from the missile’s position in the center of the vehicle to the foremost gridded plane that measures the length of the truck, we roughly estimated the size of the missile to be around 4.9 meters.

We also double-checked the dimensions of the cruise missile in the JF-17 image. Since we know that the JF-17 is roughly 14.3 meters long, we used that number as a reference value and employed Photoshop’s Vanishing Point and measuring tool again to render an approximate length of the missile, given its lowered position in relation to the edge of the fuselage. The result was 4.9 meters, which matches the reported dimensions of the Ra’ad-I and -II ALCM as well as our estimated measurements. This measurement is also longer than the Taimoor’s reported 4.38-meter length.

While it is possible that the missile could be an old Ra’ad-II, given that the 2017 version also had a ‘twin-tail’ configuration, that version of the Ra’ad-II appears to be outdated and is therefore unlikely to be utilized in a flight test. Still, it is possible that more information, images, or statements from the Pakistan government could surface that answer some of these questions.

Observing the differences between the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II missiles raises a few questions. How was Pakistan able to nearly double the range of the Ra’ad from an estimated 350 km to 550 km and then to 600 km for the newest version without noticeably changing the size of the missile to carry more fuel? The answer could possibly be that the Ra’ad-II engine design is more efficient, the construction components are made from lighter-weight materials, or the payload has been reduced.

These measurements offer additional evidence to support our conclusion that the missile observed in the photographed image of the JF-17 is the Ra’ad-I ALCM.

Implications for Pakistan’s nuclear forces

Given the lack of publicly available information from the government of Pakistan about its nuclear forces, we must rely on these types of analyses to understand the status of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. From these observations, it is likely that Pakistan has made significant progress toward equipping its JF-17s with the capability to eventually supplement–and possibly replace–the nuclear strike role of the aging Mirage III/Vs. Additionally, it is evident that Pakistan has redesigned the Ra’ad-II ALCM, but little information has been confirmed about the purpose or capabilities associated with this new design. It is also unclear whether either of the Ra’ad systems has been deployed, but this may only be a question of when rather than if. Once deployed, it remains to be seen if Pakistan will also continue to retain a nuclear gravity bomb capability for its aircraft or transition to stand-off cruise missiles only.

This all takes place in the larger backdrop of an ongoing and deepening nuclear arms competition in the region. Pakistan is reportedly pursuing the capability to deliver multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) with its Ababeel land-based missile, while India is also pursuing MIRV technology for its Agni-P and Agni-5 missiles, and China has deployed MIRVs on a number of its DF-5B ICBMs and DF-41. In addition to the Ra’ad ALCM, Pakistan has also been developing other short-range, lower-yield nuclear-capable systems, such as the NASR (Hatf-9) ballistic missile, that are designed to counter conventional military threats from India below the strategic nuclear level.

These developments, along with heightened tensions in the region, have raised concerns about accelerated arms racing as well as new risks for escalation in a potential conflict between India and Pakistan, especially since India is also increasing the size and improving the capabilities of its nuclear arsenal. This context presents an even greater need for transparency and understanding about the quality and intentions behind states’ nuclear programs to prevent mischaracterization and misunderstanding, as well as to avoid worst-case force buildup reactions.

The author would like to thank David La Boon and Decker Eveleth for their invaluable guidance and feedback on using Photoshop’s Vanishing Point feature.

Correction: After the article’s publication, the final image was removed and replaced with the correct image. The language and conclusions of the piece remained unchanged.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Notebook: Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column finds that Pakistan is continuing to gradually expand its nuclear arsenal with more warheads, more delivery systems, and a growing fissile material production industry. We estimate that Pakistan now has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 170 warheads.

Read the full “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Flying Under The Radar: A Missile Accident in South Asia

A crashed Indian missile inside Pakistani territory. Image: Pakistan Air Force.

With all eyes turned towards Ukraine these past weeks, it was easy to miss what was almost certainly a historical first: a nuclear-armed state accidentally launching a missile at another nuclear-armed state.*

On the evening of March 9th, during what India subsequently called “routine maintenance and inspection,” a missile was accidentally launched into the territory of Pakistan and impacted near the town of Mian Channu, slightly more than 100 kilometers west of the India-Pakistan border.

Because much of the world’s attention has understandably been focused on Eastern Europe, this story is not getting the attention that it deserves. However, it warrants very serious scrutiny––not only due to the bizarre nature of the accident itself, but also because both India’s and Pakistan’s reactions to the incident reveal that crisis stability between South Asia’s two nuclear rivals may be much less stable than previously believed.

The Incident

Using official statements and open-source clues, it is possible to piece together a relatively complete picture of what took place on the evening of March 9th.

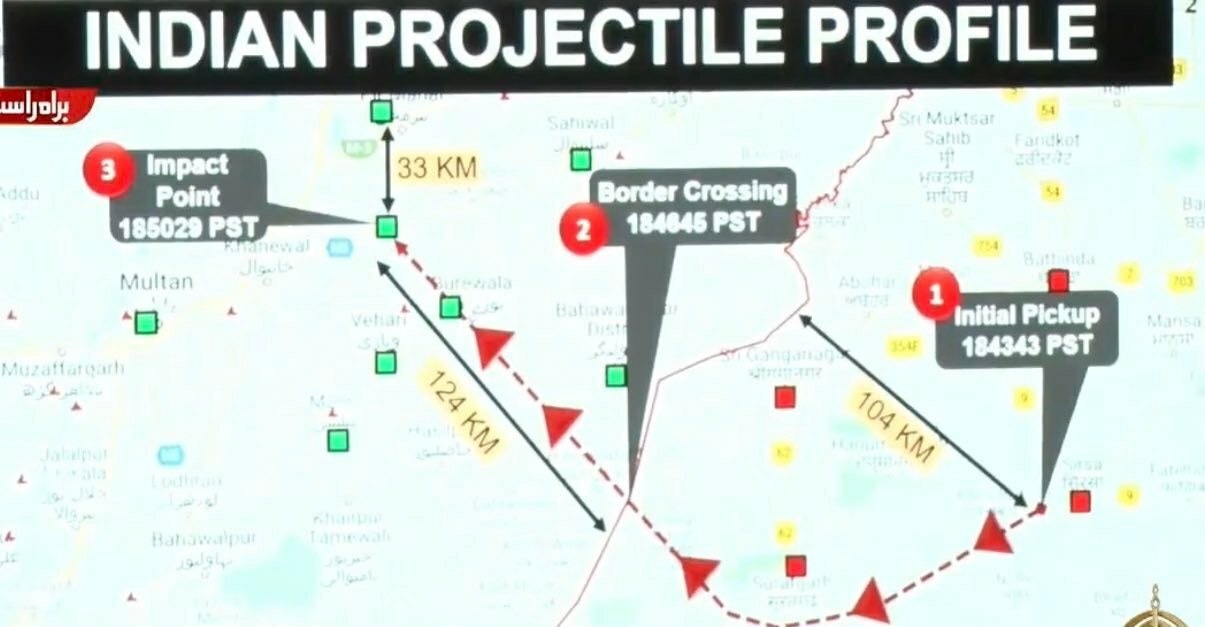

At 18:43:43 Pakistan Standard Time (19:13:43 India Standard Time), the Pakistan Air Force picked up a “high-speed flying object” 104 kilometers inside Indian territory, near Sirsa, in the state of Haryana. According Air Vice Marshal Tariq Zia––the Director General Public Relations for the Pakistan Air Force––the object traveled in a southwesterly direction at a speed between Mach 2.5 and Mach 3. After traveling between 70 and 80 kilometers, the object turned northwest and crossed the India-Pakistan border at 18:46:45 PKT. The object then continued on the same northwesterly trajectory until it crashed near the Pakistani town of Mian Channu at 18:50:29 PKT.

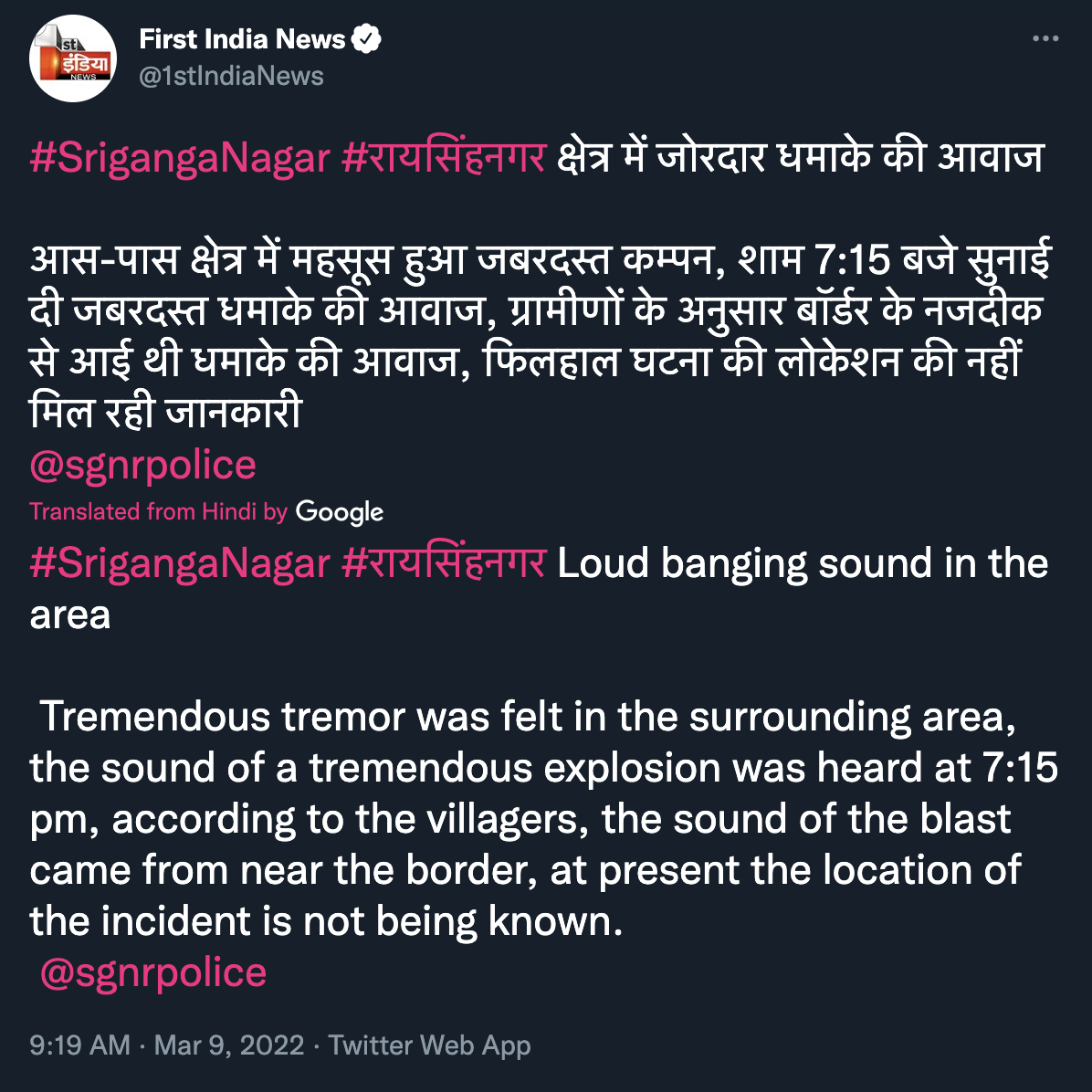

Tweet from @1stIndiaNews indicating that a “tremendous explosion” was heard at approximately 19:15 IST at the city of Sri Ganganagar near the India-Pakistan border. This time and location adds a data point to interpreting the flight path of the missile.

According to Pakistani military officials in a March 10th press conference, 3 minutes and 46 seconds of the object’s total flight time of 6 minutes and 46 seconds were within Pakistani airspace, and the total distance traveled inside of Pakistan was 124 kilometers.

Annotated map of the missile’s flight path provided by Pakistani military officials to media on 10 March 2022.

In a press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that the object was “certainly unarmed” and that no one was injured, although noted that it damaged “civilian property.”

Although the crash site has not been confirmed and official photos include very few useful visual signatures, observation of local civilian social media activity indicates that a likely candidate is the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel, just outside of Mian Channu (30°27’6.40″N, 72°24’10.87″E). One video of the crash site posted to Twitter includes a shot of a uniquely-colored blue building with a white setback roof on the other side of a divided highway. At least two vertical poles can be seen on the roof of the building. All of these signatures appear to match those included in images of the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel in Google Images.

The video’s caption suggests that the object that crashed was an “army aviation aircraft drone;” however, Pakistani military officials subsequently reported that the object was an Indian missile. Neither Pakistan nor India has publicly confirmed what type of missile it was; however, in a March 10th press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that “we can so far deduce that it was a supersonic missile––an unknown missile––and it was launched from the ground, so it was a surface-to-surface missile.”

This statement, in addition to photos of the debris and other official details relating to range, speed, altitude, and flight time of the object, suggest that it was very likely a BrahMos cruise missile.

BrahMos is a ramjet-powered, supersonic cruise missile co-developed with Russia, that can be launched from land, sea, and air platforms and can travel at a speed of approximately March 2.8. The US National Air and Space Intelligence Centre (NASIC) suggested that an earlier version of BrahMos had a range of “less than 300” kilometers, but the Indian Ministry of Defence recently announced on 20 January 2022 that it had extended the BrahMos’ range, with defence sources saying that the missile could now travel over 500 kilometres. The reported speed of the “high-speed flying object,” as well as the distance traveled, matches the publicly-known capabilities of the BrahMos cruise missile.

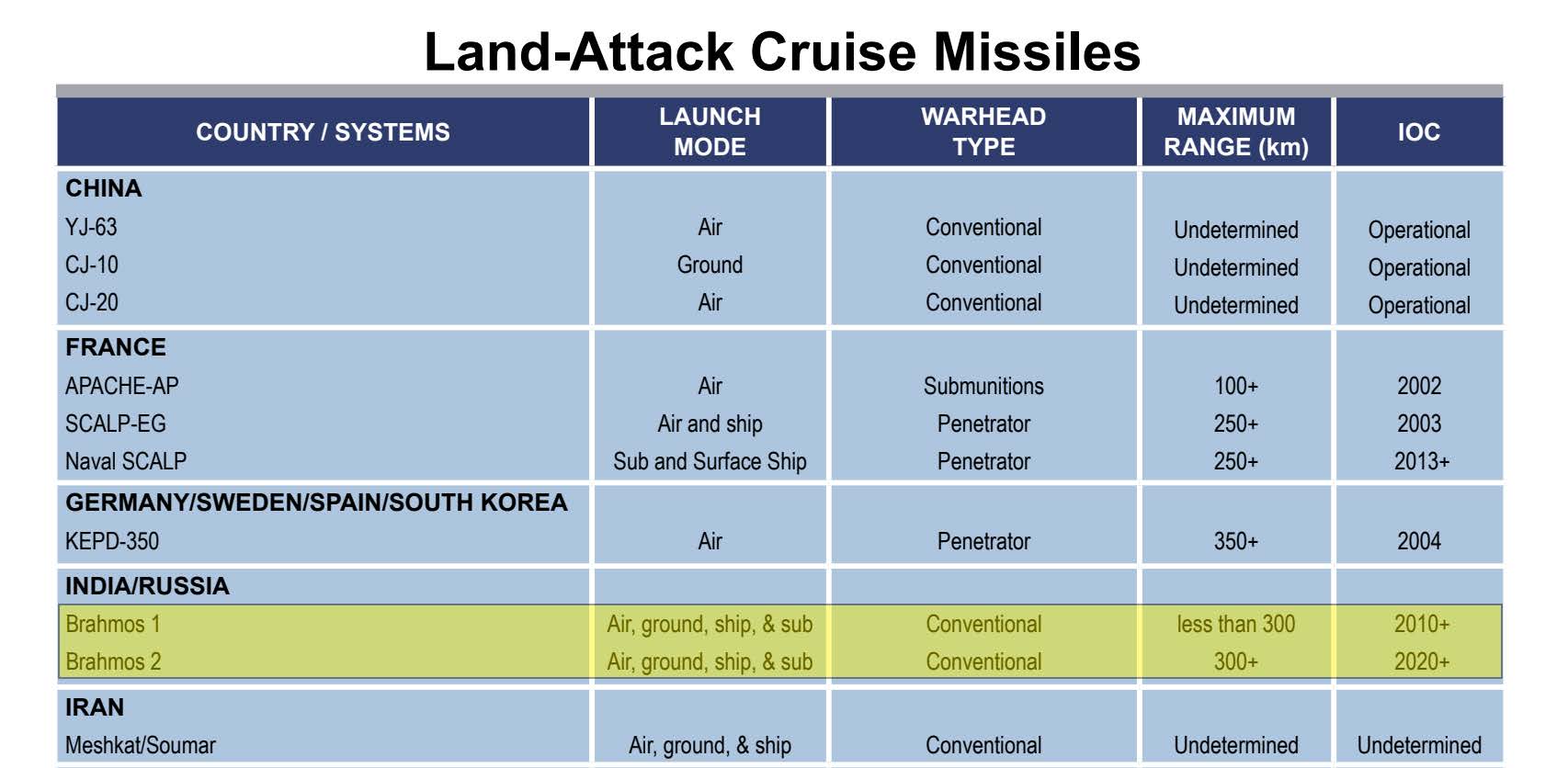

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s 2017 Ballistic and Cruise Missile report lists two versions of the BrahMos missile as “conventional.”

Although many Indian media outlets often describe the BrahMos as a nuclear or dual-capable system, NASIC lists it as “conventional,” and there is no public evidence to indicate that the missile can carry nuclear weapons.

India has launched a Court of Inquiry to determine how the incident occurred; however, the Indian government has otherwise remained tight-lipped on details. In the absence of official statements, small snippets have trickled out through Indian and Pakistani media sources––prompting several questions that still need answers.

How did the missile get “accidentally” launched?

According to the Times of India, an audit was being conducted by the Indian Air Force’s Directorate of Air Staff Inspection at the time of the launch. As part of that audit, or possibly as part of a separate exercise, it appears that target coordinates––including mid-flight waypoints––were fed into the missile’s guidance system. According to Indian defence sources, in order to launch the BrahMos, the missile’s mechanical and software safety locks would also have had to be bypassed and the launch codes would have had to be entered into the system.

The BrahMos does not appear to have a self-destruct mechanism. As a result, once the missile was launched, there was no way to abort.

Given that defence sources indicate that the missile “was certainly not meant to be launched,” it still remains unclear whether the launch was due to human or technical error. On March 11th, in its first public statement about the incident, the Indian government stated that “a technical malfunction led to the accidental firing of a missile.” However, since the formal convening of a Court of Inquiry, the government has since changed its rhetoric, with Indian officials stating that “the accidental firing took place because of human error. That’s what has emerged at this stage of the inquiry. There were possible lapses on the part of a Group Captain and a few others.” Tribute India reports that there are currently four individuals under investigation.

While this is certainly a plausible explanation for the incident, it is also worth noting that the Indian government would be financially incentivized to emphasize the human error narrative over a technical malfunction narrative. On January 28th, India concluded a $374.96 million deal with the Philippines to export the BrahMos––a deal which amounts to the country’s largest defence export contract. Additional BrahMos exports will be crucial for India to meet its ambitious defence export targets by 2025, and the negative publicity associated with a possible BrahMos technical malfunction could significantly hinder that goal.

Did Pakistan track the missile correctly?

In a press conference on March 10th, Pakistani military officials noted that Pakistan’s “actions, response, everything…it was perfect. We detected it on time, and we took care of it.” However, Indian military officials have publicly disputed Pakistan’s interpretation of the missile’s flight path. Pakistan announced on March 10th that the missile was picked up near Sirsa; however, Indian officials subsequently stated that the missile was launched from a location near Ambala Air Force Station, nearly 175 kilometers away. India’s explanation is likely to be more accurate, given that there is no known BrahMos base near Sirsa, but there is one near Ambala (h/t @tinfoil_globe). Indian defence sources have also suggested that the map of the missile’s perceived trajectory that the Pakistani military released on March 10th was incorrect.

Annotated Google Earth image showing the 175 kilometer distance between the likely launch site and Pakistan’s radar pickup.

Furthermore, Pakistani officials announced on March 10th that the missile’s original destination was likely to be the Mahajan Field Firing Range in Rajasthan, before it suddenly turned and headed northwest into Pakistan. However, Indian defence sources have since suggested that the missile was not actually headed for the Mahajan Field Firing Range, but instead was “follow[ing] the trajectory that it would have in case of a conflict, but ‘certain factors’ played a role in ensuring that any pre-fed target was out of danger.” Given that the impact site was not near any critical military or political infrastructure, this could suggest that the cruise missile had its wartime mid-flight trajectory waypoints pre-loaded into the system, but its actual target had not yet been selected. If this is the case, then this targeting practice would be similar in nature to how some other nuclear-armed states target their missiles at the open ocean during peacetime––precisely in case of incidents like this one. Although the missile still landed on Pakistani territory, the fact that it did not hit any critical targets prevented the crisis from escalating. It is worth noting, however, that this would certainly not be the case if the missile had actually injured or killed anyone.

During the March 10th press conference, Pakistani officials noted that the Pakistan Air Force did not attempt to shoot down the missile because “the measures in place in times of war or in times of escalation are different [from those] in peace time.” However, India’s challenges to Pakistan’s narrative also raise significant questions about whether the Pakistan Air Force was able to accurately track the missile correctly. If not, then this raises the possibility of miscalculation or miscommunication, and crisis stability would be seriously eroded if a similar situation occurred during a time of heightened tensions.

Were any civilian aircraft put in danger?

In its public statements, Pakistan has emphasized that the accidental missile launch could have put civilian flights in danger, as India did not issue a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) prior to launch. Governments typically issue NOTAMs in conjunction with missile tests, in order to inform civilian aircraft to avoid a particular patch of airspace during the launch window. Given that India did not issue one, a time-lapse video prepared by Flightradar24 showed that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch. The video erroneously suggests that the missile traveled in a straight line from Ambala to Mian Channu, when it appears to have dog-legged in mid-flight; however, the video is still a useful resource to demonstrate how crowded the skies were at the time of the accident.

A screenshot of a video prepared by Flightradar24, showing that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch.

Why was India’s response so poor?

Given the seriousness of the incident, India’s delayed response has been particularly striking. Immediately following the accidental launch, India could have alerted Pakistan using its high-level military hotlines; however, Pakistani officials stated that it did not do so. Additionally, India waited two days after the incident before issuing a short public statement.

India’s poor response to this unprecedented incident has serious implications for crisis stability between the two countries. According to DNA India, in the absence of clarification from India, Pakistan Air Force’s Air Defence Operations Centre immediately suspended all military and civilian aircraft for nearly six hours, and reportedly placed frontline bases and strike aircraft on high alert. Defence sources stated that these bases remained on alert until 13:00 PKT on March 14th. Pakistani officials appeared to confirm this, noting that “whatever procedures were to start, whatever tactical actions had to be taken, they were taken.”

We were very, very lucky

Thankfully, this incident took place during a period of relative peacetime between the two nuclear-armed countries. However, in recent years India and Pakistan have openly engaged in conventional warfare in the context of border skirmishes. In one instance, Pakistani military officials even activated the National Command Authority––the mechanism that directs the country’s nuclear arsenal––as a signal to India. At the time, the spokesperson of the Pakistan Armed Forces not-so-subtly told the media, “I hope you know what the NCA means and what it constitutes.”

If this same accidental launch had taken place during the 2019 Balakot crisis, or a similar incident, India’s actions were woefully deficient and could have propelled the crisis into a very dangerous phase.

Furthermore, as we have written previously, in recent years India’s rocket forces have increasingly worked to “canisterize” their missiles by storing them inside sealed, climate-controlled tubes. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis.

This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

India’s recent missile accident––and the deficient political and military responses from both parties––suggests that regional crisis instability is less stable than previously assumed. To that end, this crisis should provide an opportunity for both India and Pakistan to collaboratively review their communications procedures, in order to ensure that any future accidents prompt diplomatic responses, rather than military ones.

Background Information:

- “Indian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August 2020.

- “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept/Oct 2021.

- “India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, Dec 2021.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This article was made possible with generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

*[Note: This type of missile accident has apparently happened before; on 11 September 1986, a Soviet missile flew more than 1,500 off-course and landed in China. Thank you to the excellent Stephen Schwartz for the historical reference.]

Categories: Arms Control, ballistic missiles, Deterrence, Disarmament, India, Nuclear Weapons, Pakistan

New NASIC Report Appears Watered Down And Out Of Date

The US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published a new version of its widely referenced Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report.

The agency normally puts out an updated version of the report every four years. The previous version dates from 2017.

The 2021 report (dated 2020) provides information on developments in many countries but is clearly focused on China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. Especially the North Korean data is updated because of the significant developments since 2017.

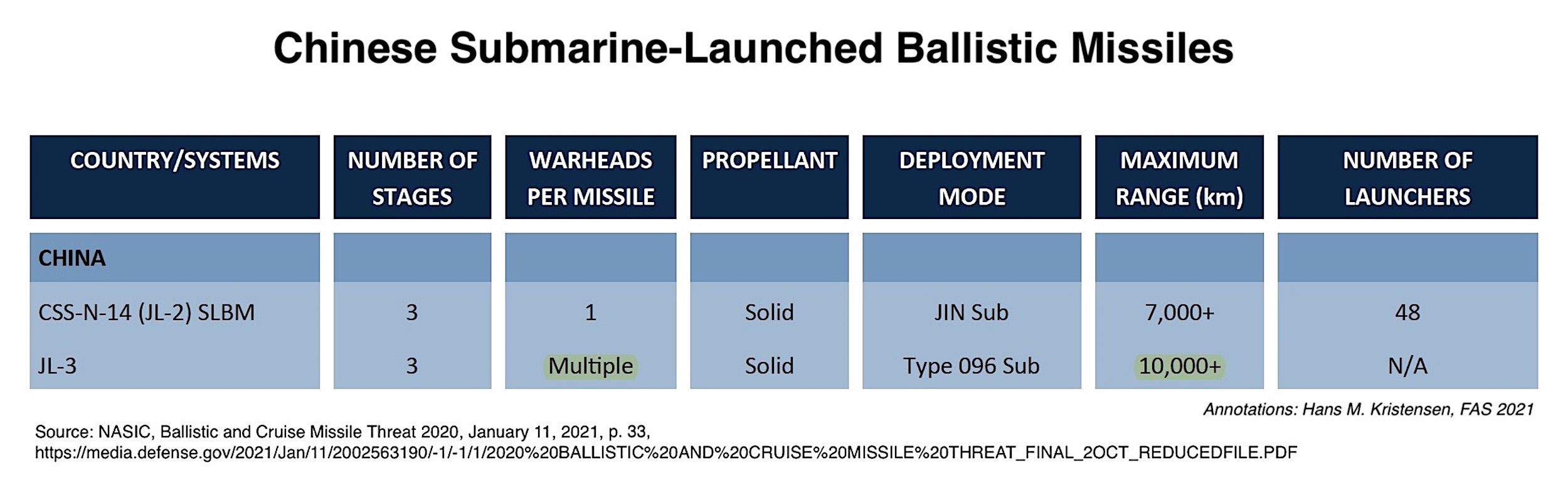

The most interesting new information in the updated report is probably that the new Chinese JL-3 sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is capable of carrying multiple warheads.

Overall, however, the new report may be equally interesting because of what it does not include. There are a number of cases where the report is scaled back compared with previous versions. And throughout the report, much of the data clearly hasn’t been updated since 2018. In some places it is even inconsistent and self-contradicting.

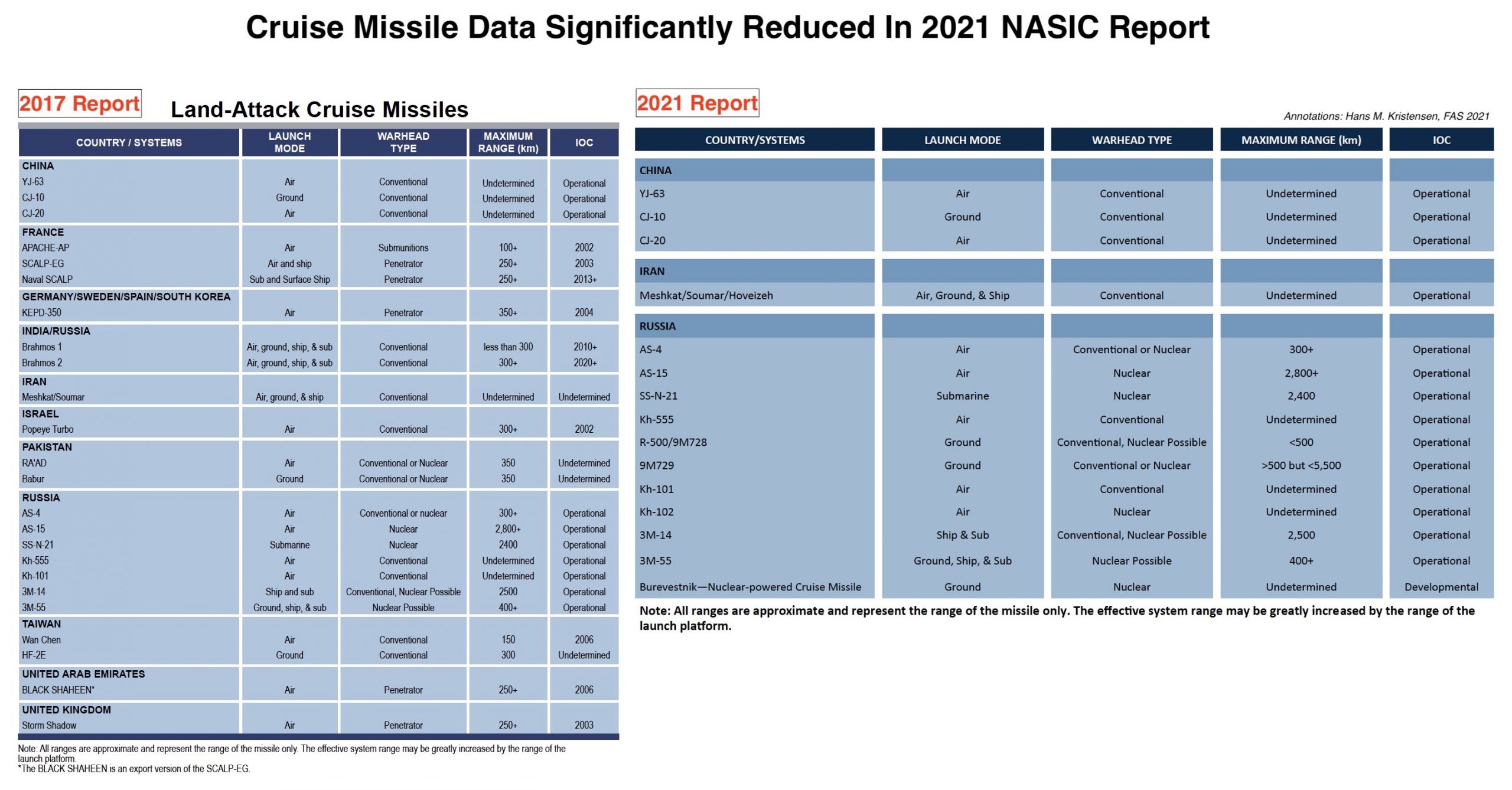

The most significant data reduction is in the cruise missile section where the report no longer lists countries other than Russia, China, and Iran. This is a significant change from previous reports that listed a wide range of other countries, including India and Pakistan and many others that have important cruise missile programs in development. The omission is curious because the report in all ballistic missile categories includes other countries.

Cruise missile data is significantly reduced in the new NASIC report compared with the previous version from 2017. Click on image to view full size.

Other examples of reduced data include the overview of ballistic missile launches, which for some reason does not show data for 2019 and 2020. Nor is it clear from the table which countries are included.

Also, in some descriptions of missile program developments the report appears to be out of date and not update on recent developments. This includes the Russian SS-X-28 (RS-26 Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM, which the report portrays as an active program but only presents data for 2018. Likewise, the report does not mention the two additional boats being added to the Chinese SSBN fleet. Moreover, the new section with air-launched ballistic missiles only includes Russia but leaves out Chinese developments and only appears to include data up through early 2018.

Whether these omissions reflect changes in classification rules, chaos is the Intelligence Community under the Trump administration, or simply oversight is unknown.

Below follows highlights of some of the main nuclear issues in the new report.

Russian Nuclear Forces

Information about Russian ballistic and cruise missile programs dominate the report, but less so than in previous versions. NASIC says Russia currently has approximately 1,400 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, a reduction from the “over 1,500” reported in 2017. The new number is well known from the release of New START data and is very close to the 1,420 warheads we estimated in our Russian Nuclear Notebook last year.

NASIC repeats the projection from 2017, that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints….”

The statement that “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs” is curious, however, because would imply the SLBM force is loaded with fewer warheads than normally assumed. The warhead loading attributed to the SS-N-32 (Bulava) is 6, the number declared by Russia under the START treaty, and less than the 10 warheads that is often claimed by unofficial sources.

The new version describes continued development of the SS-28 (RS-26 (Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM suspected by some to actually be an IRBM. But the report only lists development activities up through 2018 and nothing since. The system is widely thought to have been mothballed due to budget constraints.

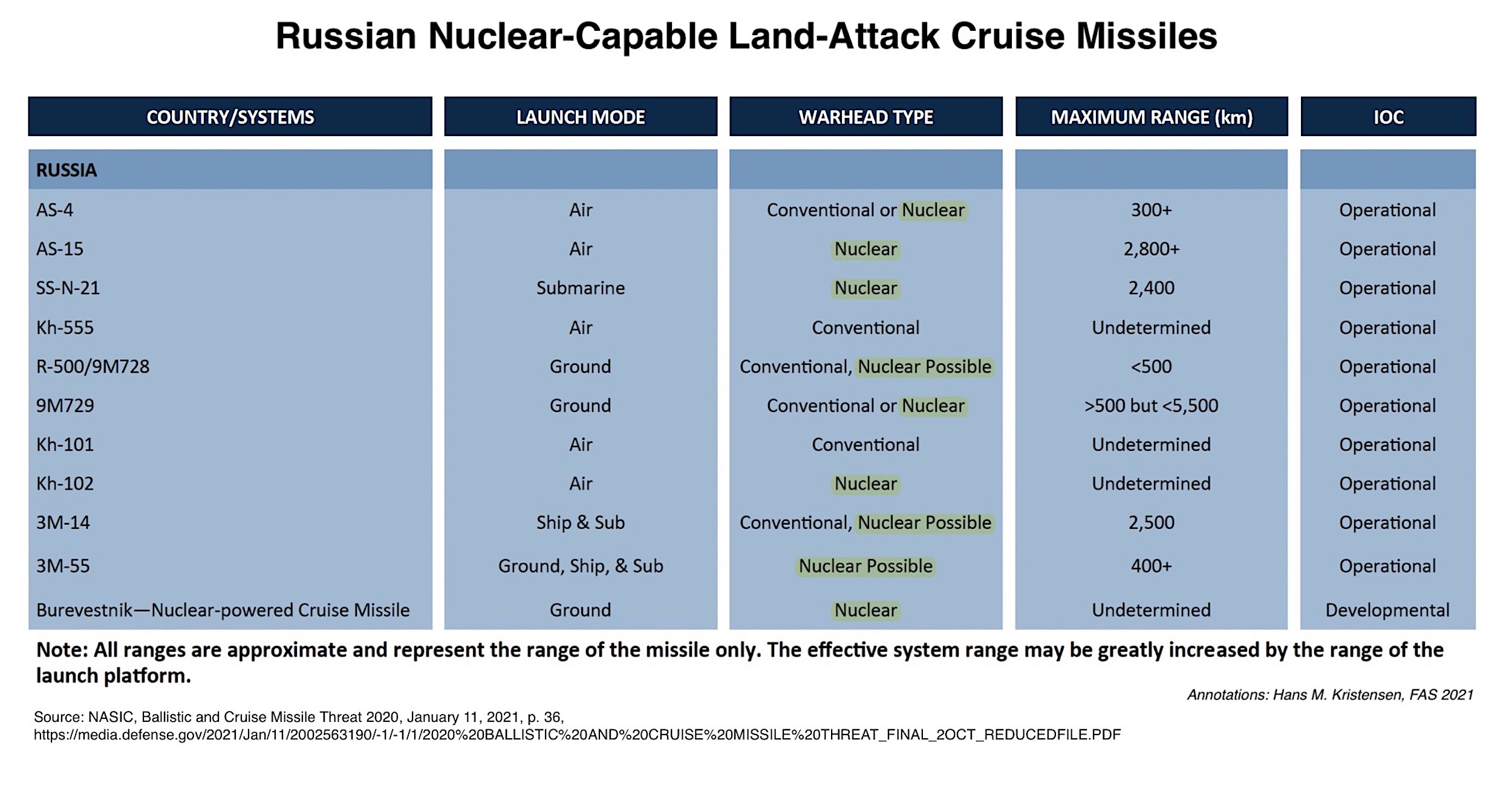

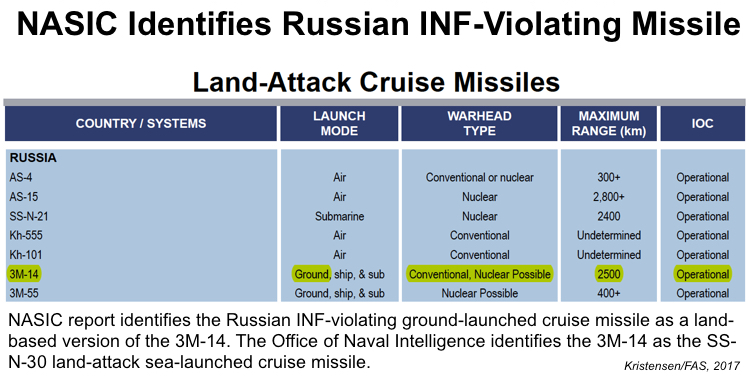

The cruise missile section attributes nuclear capability – or possible nuclear capability – to most of the Russian missiles listed. Six systems are positively identified as nuclear, including the Kh-102, which was not listed in the 2017 report. Two of the nuclear systems are dual-capable, including the 9M729 (SSC-8) missile the US said violated the now-abandoned INF treaty, while 3 missiles are listed as “Conventional, Nuclear Possible.” That includes the 9M728 (R-500) cruise missile (SSC-7) launched by the Iskander system, the 3M-14 (Kalibr) cruise missile (SS-N-30), and the 3M-55 (Yakhont, P-800) cruise missile (SS-N-26).

NASIC attributes nuclear capability to nine Russian land-attack cruise missiles, three of them “possible.” Click on image to view full size.

The designation of “nuclear possible” for the SS-N-30 (3M-14, often called the Kalibr even though Kalibr is strictly speaking the name of the launcher system) is curious because the Russian government has clearly stated that the missile is nuclear-capable.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

The biggest news in the China section of the NASIC report is that the new JL-3 SLBM that will arm the next-generation Type 096 SSBN will be capable of delivering “multiple” warheads and have a range of more than 10,000 kilometers. That is a significant increase in capability compared with the JL-2 SLBM currently deployed on the Jin-class SSBNs and is likely part of the reason for the projection that China’s nuclear stockpile might double over the next decade.

NASIC reports that China’s next-generation JL-3 SLBM will be capable of carrying “multiple” warheads. Click on image to view full size.

Despite this increased range, however, a Type 096 operating from the current SSBN base in the South China Sea would not be able to strike targets in the continental United States. To be able to reach targets in the continental United States, an SSBN would have to launch its missile from the Bohai Sea. That would bring almost one-third of the continental United States within range. To target Washington, DC, however, a Type 096 SSBN would still have to deploy deep into the Pacific.

The new DF-41 (CSS-20) has lost its “-X-“ designation (CSS-X-20), which indicates that NASIC considers the missile has finished development is now being deployed. A total of 16+ launchers are listed, probably based on the number attending the 2019 parade in Beijing and the number seen operating in the Jilantai training area.

The number of DF-31A and DF-31AG launchers is very low, 15+ and 16+ respectively, which is strange given the number of bases observed with the launchers. Of course, “+” can mean anything and we estimate the number of launchers is probably twice that number. Also interesting is that the DF-31AG is listed as “UNK” (unknown) for warheads per missile. The DF-31A is listed with one warhead, which suggests that the AG version potentially could have a different payload. Nowhere else is the AG payload listed as different or even multiple warheads.

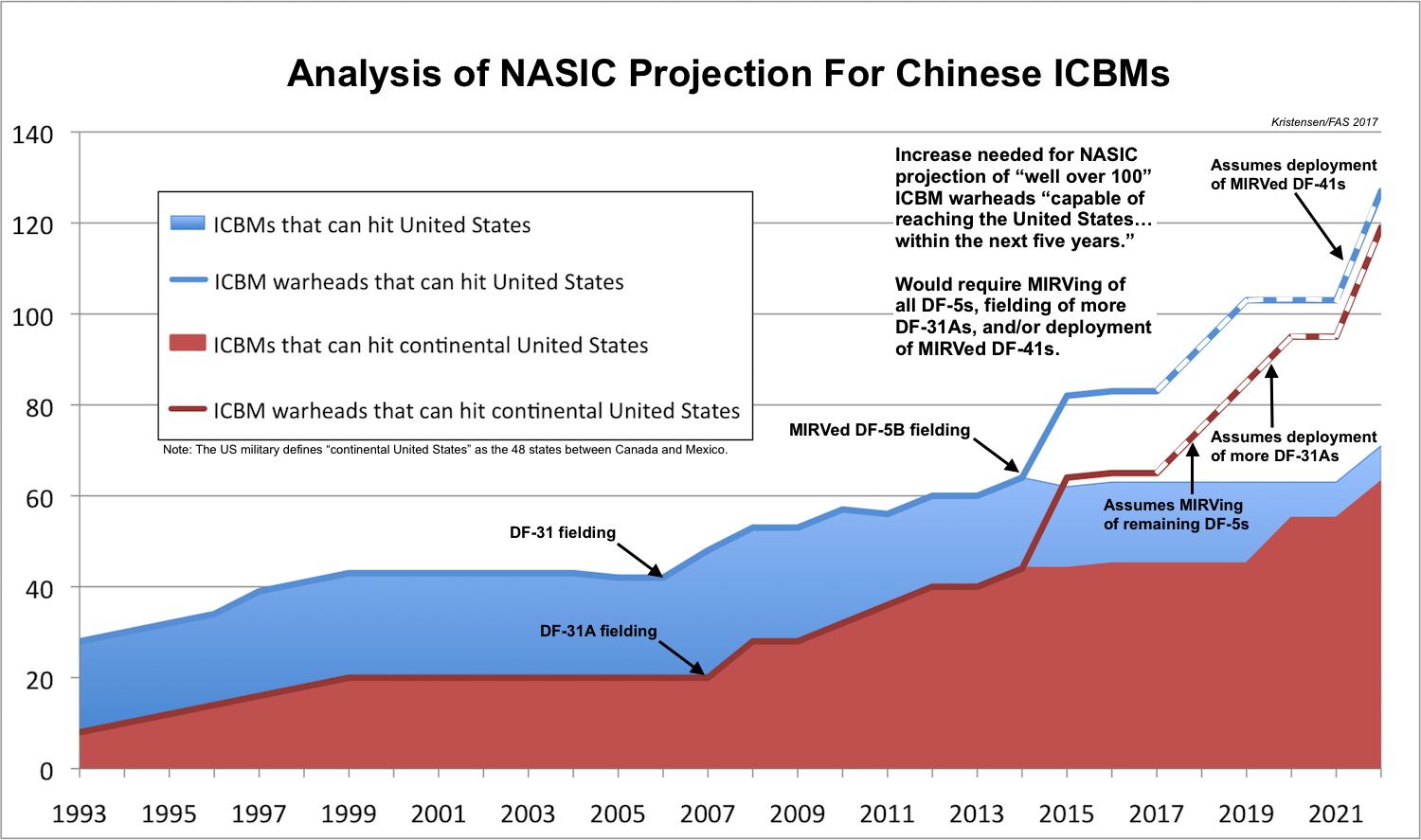

The NASIC report projection for the increase in Chinese nuclear ICBM warheads that can reach the United States is inconsistent and self-contradicting. In one section (p. 3) the report predicts “the number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States potentially expanding to well over 200 within the next 5 years.” But in another section (p. 27), the report states that the “number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 5 years.” The projection of “well over 100” was also listed in the 2017 report, and the “well over 200” projection matches the projection made in the DOD annual report on Chinese military developments. So the authors of the NASIC might simply have forgotten to update the text.

On Chinese shorter-range ballistic missiles, the NASIC report only mentions DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2) as nuclear, but not the CSS-5 Mod 6 version. The Mod 6 version (potentially called DF-21E) was first mentioned in the 2016 DOD report on Chinese military developments and has been included since.

Newer missiles finally get designations: The dual-capable DF-26 is called the CSS-18, and the conventional (possibly) DF-17 is called the CSS-22. NASIC continues to list the DF-26 range as less (3,000+ km) than the annual DOD China report (4,000 km).

An in case anyone was tempted, no, none of China’s cruise missiles are listed as nuclear-capable.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

The report provides no new information about Pakistani nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. As with several other sections in the report, the information does not appear to have been updated much beyond 2018, if at all. As such, status information should be read with caution.

The Shaheen-III MRBM is still not deployed, nor is the Ababeel MRBM that NASIC describes as a “MIRV version.” It has only been flight-tested once.

The tactical nuclear-capable NASR is listed with a range of 60 km, the same as in 2017, even though the Pakistani government has since claimed the range has been extended to 70 km.

Because the new NASIC report no longer includes data on Pakistan’s cruise missiles, neither the Babur nor the RAAD programs are described. Nor is any information provided about the efforts by the Pakistani navy to develop a submarine-launched nuclear-capable cruise missile.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Similar to other sections of the report, the data on Indian programs are tainted by the fact that some information does not appear to have been updated since 2018, and that the cruise missile section does not include India at all.

According to the report, Agni II and Agni III MRBMs are still deployed in very low numbers, fewer than 10 launchers, the same number reported in 2017. That number implies only a single brigade of each missile. But, again, it is not clear this information has actually been updated.

Nor are the Agni IV or the Agni V listed as deployed yet.

North Korean Forces

The North Korean sections are main interesting because of the inclusion of data on several systems test-launched since the previous report in 2017. This contrasts several other data set in the report, which do not appear to have been updated past 2018. But since the North Korean long-range tests occurred in 2017, this may explain why they are included.

NASIC provides official (unclassified) range estimates for these missiles:

The Hwasong-12 IRBM range has been increased from 3,000+ km in 2017 to 4,500+ km in the new report.

On the ICBMs, the Taepo Dong 2 no longer has a range estimate. The Hwasong-13 and Hwasong-14 range estimates have been raised from the generic 5,500+ km in the 2017 report to 12,000 km and 10,000+ km, respectively, in the new report, and the new Hwasong-15 has been added with a range estimate of 12,000+ km. The warhead loading estimates for the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15 are “unknown” and none of the ICBMs are listed as deployed.

On submarine-launched missiles, the NASIC report lists two: the Puguksong-1 and Pukguksong-3. Both have range estimates of 1,000+ km and the warhead estimate for the Pukguksong-3 is unknown (“UNK”). Neither is deployed. The new Pukguksong-4 paraded in October 2020 is not listed, not is the newest Pukguksong-5 displayed in early 2021 mentioned.

Additional background information:

• Russian nuclear forces, 2020

New Nuclear Notebook: Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2018

A Babur-3 dual-capable SLCM is test-launched from an underwater platform in the Indian Ocean on January 9, 2017.

By Hans M. Kristensen, Robert S. Norris, and Julia Diamond

The latest FAS Nuclear Notebook has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: Pakistani nuclear forces, 2018 (direct link to PDF). We estimate that Pakistan by now has accumulated an arsenal of 140-150 nuclear warheads for delivery by short- and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles and aircraft.

This is an increase of about ten warheads compared with our estimate from last year and continues the pace of the gradual increase of Pakistan’s arsenal we have seen for the past couple of decades. The arsenal is now significantly bigger than the 60-80 warheads the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency in 1999 initially estimated Pakistan might have by 2020. If the current trend continues, we estimate that the Pakistani nuclear warhead stockpile could potentially grow to 220-250 warheads by 2025.

The future development obviously depends on many factors, not least the Pakistani military believes the arsenal needs to continue to grow or level out at some point. Also important is how the Indian nuclear arsenal evolves.

The Pakistani government and officials initially described Pakistan’s posture as a “credible minimum deterrent” but with development of tactical nuclear weapons later began to characterize it as a “full spectrum deterrent.” Moreover, development is now underway to add a sea-based leg to its nuclear posture, and a flight test was conducted in 2017 of a ballistic missile that Pakistani officials said would be capable of carrying multiple warheads to overcome missile defense systems.

Additional information can be found here:

Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Yet the description of the DF-31A program sounds like deployment is still in progress: “The longer range CSS-10 Mod 2 will allow targeting of most of the continental United States” (emphasis added).

For the first time, the report includes a graphic illustration of the DF-31 and DF-31A side by side, which shows the longer-range DF-31A to be little shorter but with a less pointy nosecone and a wider third stage (see image).

The long-awaited (and somewhat mysterious) DF-41 ICBM is still not deployed. NASIC says the DF-41 is “possibly capable of carrying MIRV,” a less certain determination than the 2017 DOD report, which called the missile “MIRV capable.” The report lists the DF-41 with three stages and a Post-Boost Vehicle, details not provided in the previous report.

One of the two nuclear versions of the DF-21 MRBM appears to have been retired. NASIC only lists one: CSS-5 Mod 2. In total, the report lists “fewer than 50” launchers for the nuclear version of the DF-21, which is the same number it listed in the 2013 report (see here for description of one of the DF-21 launch units. But that was also the number listed back then for the older nuclear DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1). The nuclear MRBM force has probably not been cut in half over the past four years, so perhaps the previous estimate of fewer than 50 launchers was intended to include both versions. The NASIC report does not mention the CSS-5 Mod 6 that was mentioned in the DOD’s annual report from 2016.

Sea-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report lists a total of 48 JL-2 SLBM launchers, corresponding to the number of launch tubes on the four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. That does not necessarily mean, however, that the missiles are therefore fully operational or deployed on the submarines under normal circumstances. They might, but it is yet unclear how China operates its SSBN fleet (for a description of the SSBN fleet, see here).

The 2017 report no longer lists the Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN or the JL-1 SLBM, indicating that China’s first (and not very successful) sea-based nuclear capability has been retired from service.

Cruise Missiles: The new report removes the “conventional or nuclear” designation from the DH-10 (CJ-10) ground-launched land-attack cruise missile. The possible nuclear option for the DH-10 was listed in the previous three NASIC reports (2006, 2009, and 2013). The DH-10 brigades are organized under the PLA Rocket Force that operates both nuclear and conventional missiles.

A US Air Force Global Strike Command document in 2013 listed another cruise missile, the air-launched DH-20 (CJ-20), with a nuclear option. NASIC has never attributed nuclear capability to that weapon and the Office of the Secretary of Defense stated recently that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.”

At the same time, the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently told Congress that China was upgrading is cruise missiles further, including “with two, new air-launched ballistic [cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Pakistan

The NASIC report surprisingly does not list Pakistan’s Babur GLCM as operational.

The NASIC report states that “Pakistan continues to improve the readiness and capabilities of its Army Strategic Force Command and individual strategic missile groups through training exercises that include live missile firings.” While all nuclear-armed states do that, the implication probably is that Pakistan is increasing the reaction time of its nuclear missiles, particularly the short-range weapons.

The report states that the Shaheen-2 MRBM has been test-launched “seven times since 2004.” While that fits the public record, NASIC doesn’t mention that the Shaheen-2 for some reason has not been test launched since 2014, which potentially could indicate technical problems.

The Abdali SRBM now has a range of 200 km (up from 180 km in the 2013 report). It is now designated as close-range ballistic missile instead of a short-range ballistic missile.

NASIC describes the Ababeel MRBM, which was first test-launch in January 2017, as as “MIRVed” missile. Although this echoes the announcement made by the Pakistani military at the time, the designation “the MIRVed Abadeel” sounds very confident given the limited flight history and the technological challenges associated with developing reliable MIRV systems.

Neither the Ra’ad ALCM nor the Babur GLCM is listed as deployed, which is surprising especially for the Babur after 13 flight tests. Babur launchers have been fitting out at the National Development Complex for years and are visible at some army garrisons. Nor does NASIC mention the Babur-2 or Babur-3 (naval version) versions that have been test-flown and announced by the Pakistani military.

India

It is a surprise that the NASIC report only lists “fewer than 10” Agni-2 MRBM launchers. This is the same number as in 2013, which indicates there is still only one operational missile group equipped with the Agni-2 seven years after the Indian government first declared it deployed. The slow introduction might indicate technical problems, or that India is instead focused on fielding the longer-range Agni-3 IRBM that NASIC says is now deployed with “fewer than 10” launchers.

Neither the Agni-4 nor Agni-5 IRBMs are listed as deployed, even though the Indian government says the Agni-4 has been “inducted” into the armed forces and has reported three army “user trial” test launches. NASIC says India is developing the Agni-6 ICBM with a range of 6,000 km (3,728 miles).

For India’s emerging SSBN fleet, the NASIC report lists the short-range K-15 SLBM as deployed, which is a surprise given that the Arihant SSBN is not yet considered fully operational. The submarine has been undergoing sea-trials for several years and was rumored to have conducted its first submerged K-15 test launch in November 2016. But a few more are probably needed before the missile can be considered operational. The K-4 SLBM is in development and NASIC sets the range at 3,500 km (2,175 miles).

As for cruise missiles, it is helpful that the report continue to list the Bramos as conventional, which might help discredit rumors about nuclear capability.

North Korea

Finally, of the nuclear-armed states, NASIC provides interesting information about North Korea’s missile programs. None of the North Korean ICBMs are listed as deployed.

The report states there are now “fewer than 50” launchers for the Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM. NASIC sets the range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles) instead of the 4,000 km (2,485 miles) sometimes seen in the public debate.

Likewise, while many public sources set the range of the mobile ICBMs (KN-08 and KN-14) as 8,000 km (4,970 miles) – some even longer, sufficient to reach parts of the United States, the NASIC report lists a more modest range estimate of 5,500+ km (3,418 miles), the lower end of the ICBM range.

Additional Information:

- Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2017 [Note: A corrected NASIC report was published in June 2017.]

- Previous versions of this NASIC report: 2006, 2009, 2013

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

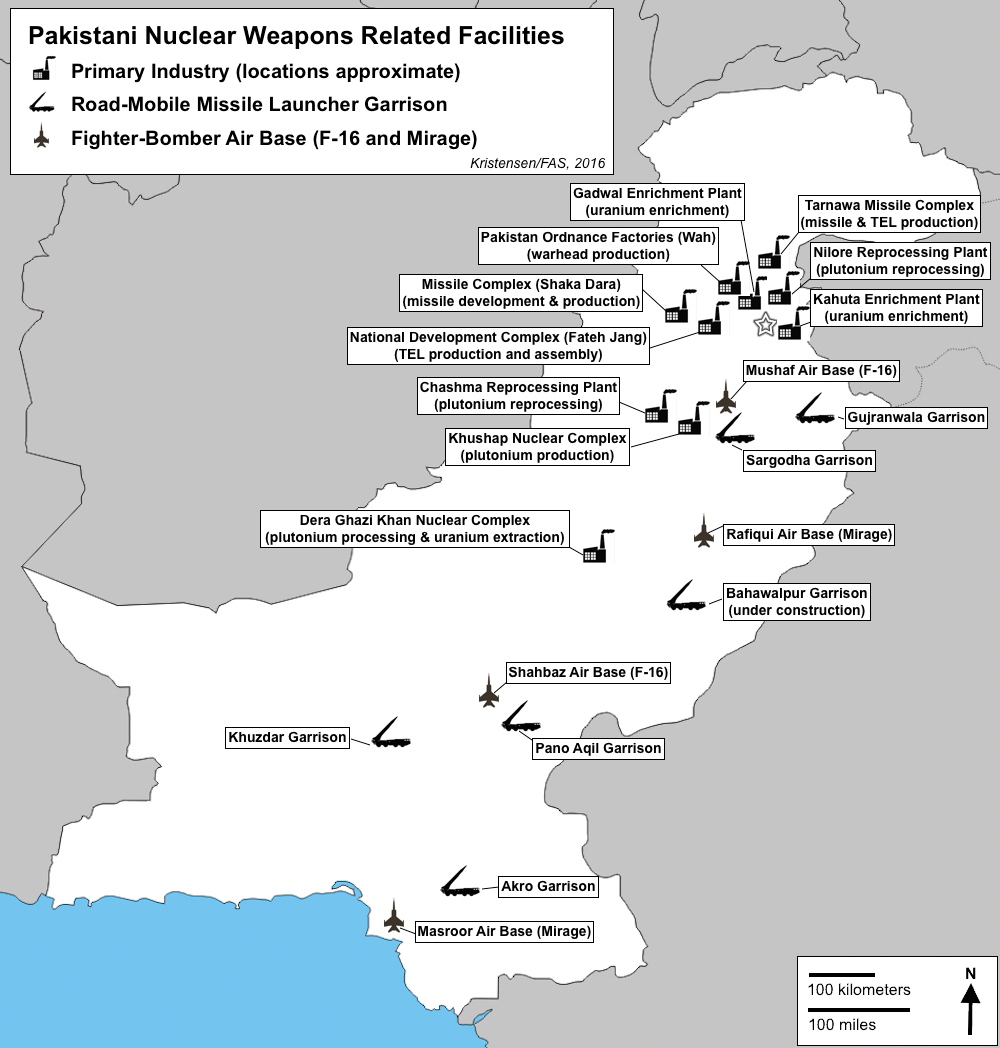

Pakistan’s Evolving Nuclear Weapons Infrastructure

Pakistan’s tactical NASR nuclear-capable mobile rocket launcher now appears to be deployed.

In our latest Nuclear Notebook on Pakistani nuclear forces, Robert Norris and I estimate that Pakistan has produced an estimated stockpile of 130-140 nuclear warheads for delivery by short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and fighter-bombers.

Pakistan now identifies with what is described as a full-spectrum nuclear deterrent posture, which is though to include strategic missiles and fighter-bombers for so-called retaliatory strikes in response to nuclear attacks, and short-range missiles for sub-strategic use in response to conventional attacks.

Although there have been many rumors over the years, the location of the nuclear-capable launchers has largely evaded the public eye for much of Pakistan’s 19-year old declared nuclear weapons history. Most public analysis has focused on the nuclear industry (see here for a useful recent study). But over the past several years, commercial satellite pictures have gradually brought into light several facilities that might form part of Pakistan’s evolving nuclear weapons launcher posture.

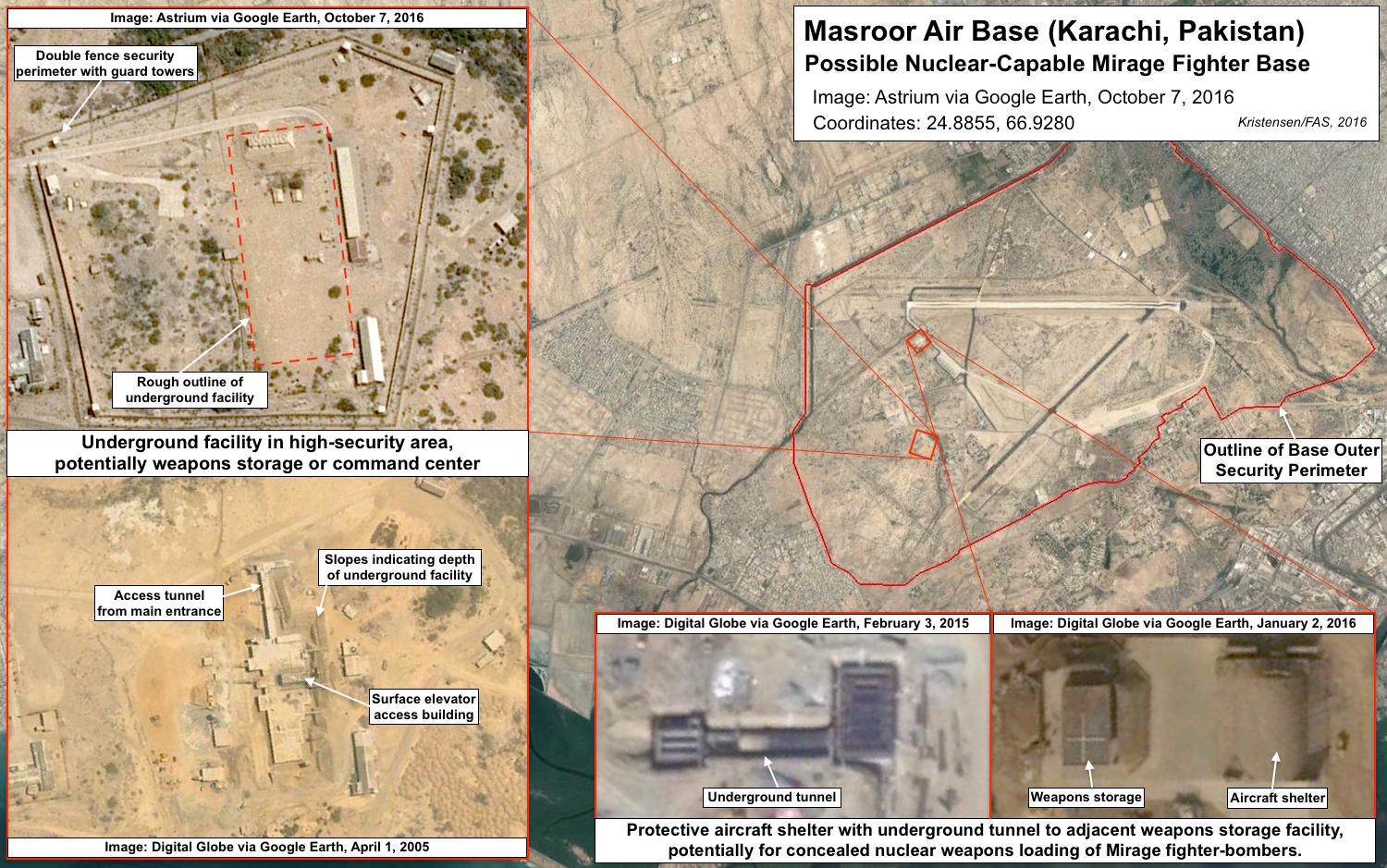

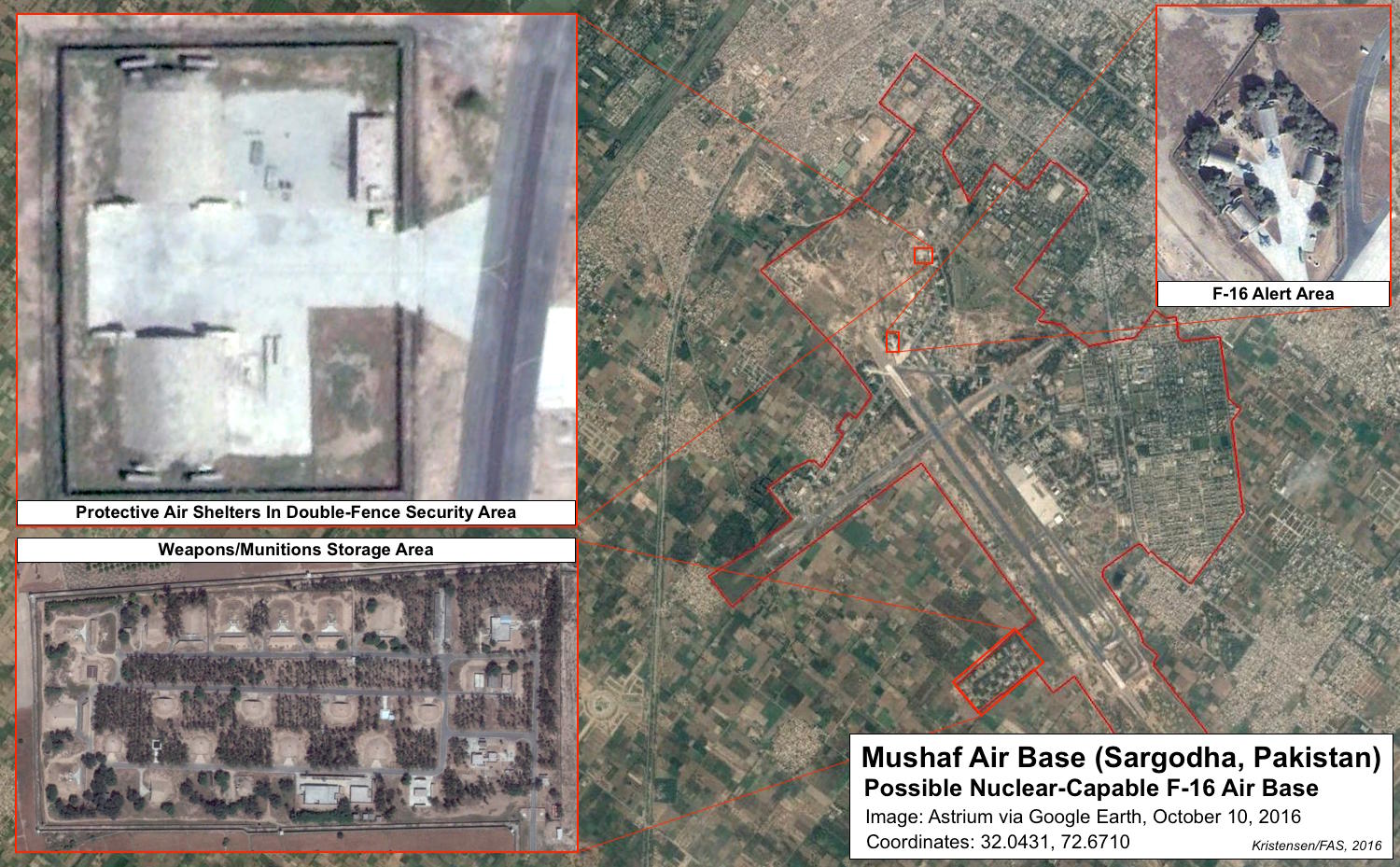

This includes 10 facilities, including 5 missile garrisons (soon possibly 6) as well 2 (possibly 4) air bases with fighter-bombers.

Pakistan’s nuclear weapons related infrastructure includes at least 10 major industrial facilities and about 10 bases for nuclear-capable forces. Click map to view full size.

The nuclear warheads that would arm the launchers are thought to be stored at other secure facilities that have not yet been identified. In a crisis, these warheads would first have to be brought to the bases and mated with the launchers before they could be used.

Security at these and other Pakistani defense facilities is a growing concern and many have been upgraded with additional security perimeters during the past 10 years in response to terrorist attacks.

There are still many unknowns and uncertainties about the possible nuclear role of these facilities. All of the launchers are thought to be dual-capable, which means they can deliver both conventional and nuclear warheads. So even if a base has a nuclear role, most of the launchers might be assigned to the conventional mission. Further analysis in the future might disqualify some and identify others. But for now, this profile of potential road-mobile launcher garrisons and air bases are intended as a preliminary guide and accompany the recent FAS Nuclear Notebook on Pakistani nuclear forces.

Nuclear-Capable Road-Mobile Missile Launcher Bases

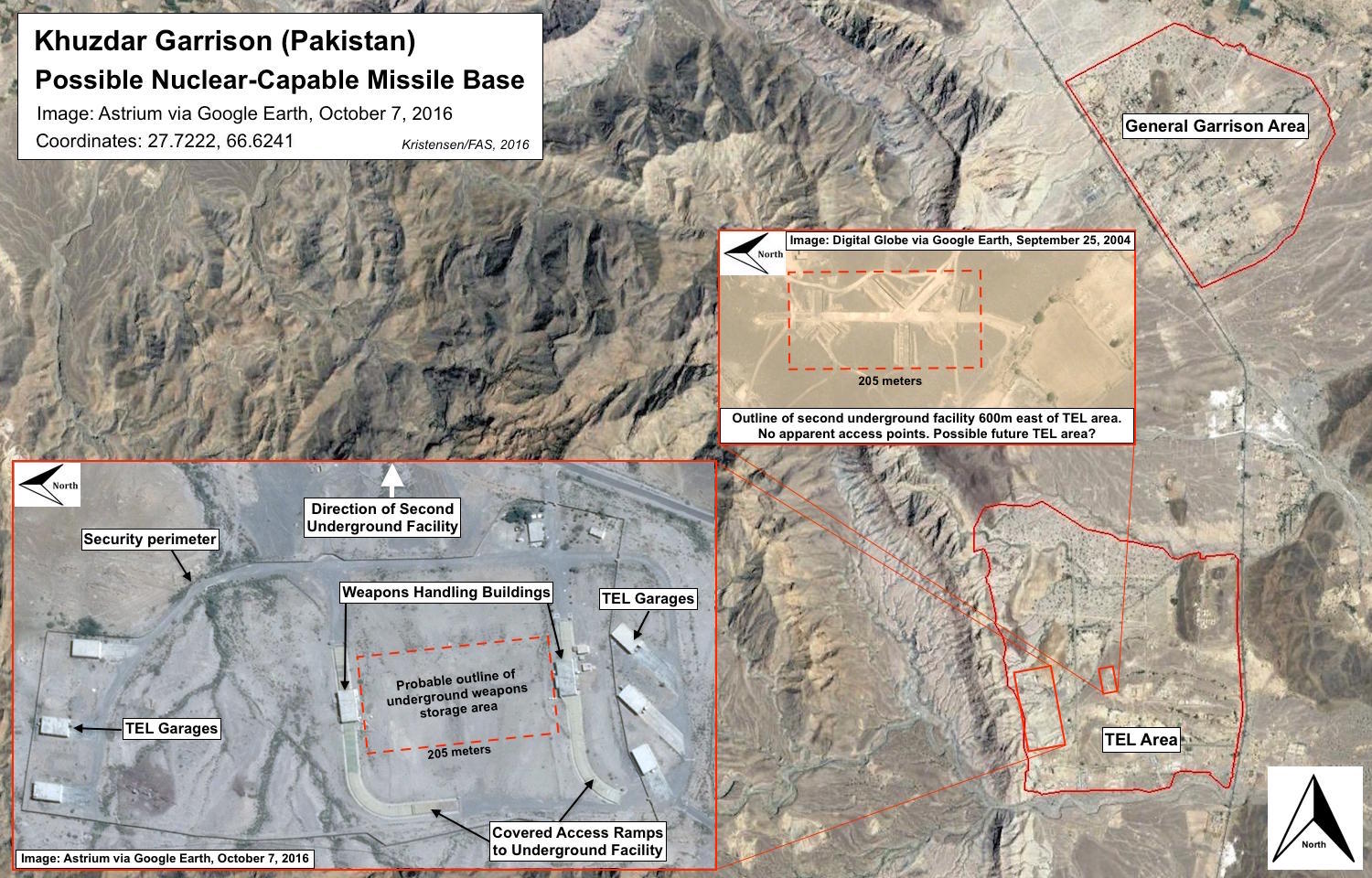

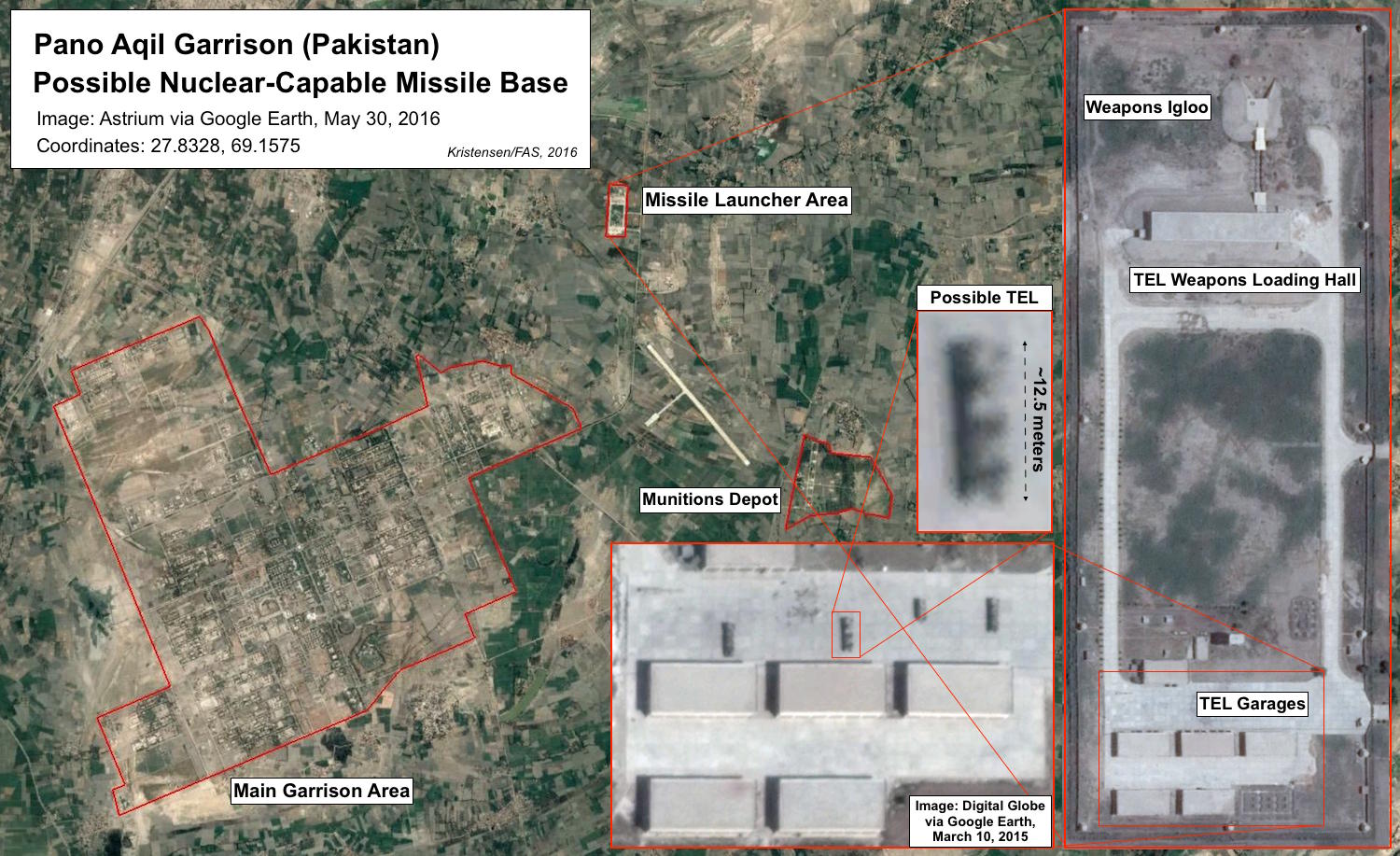

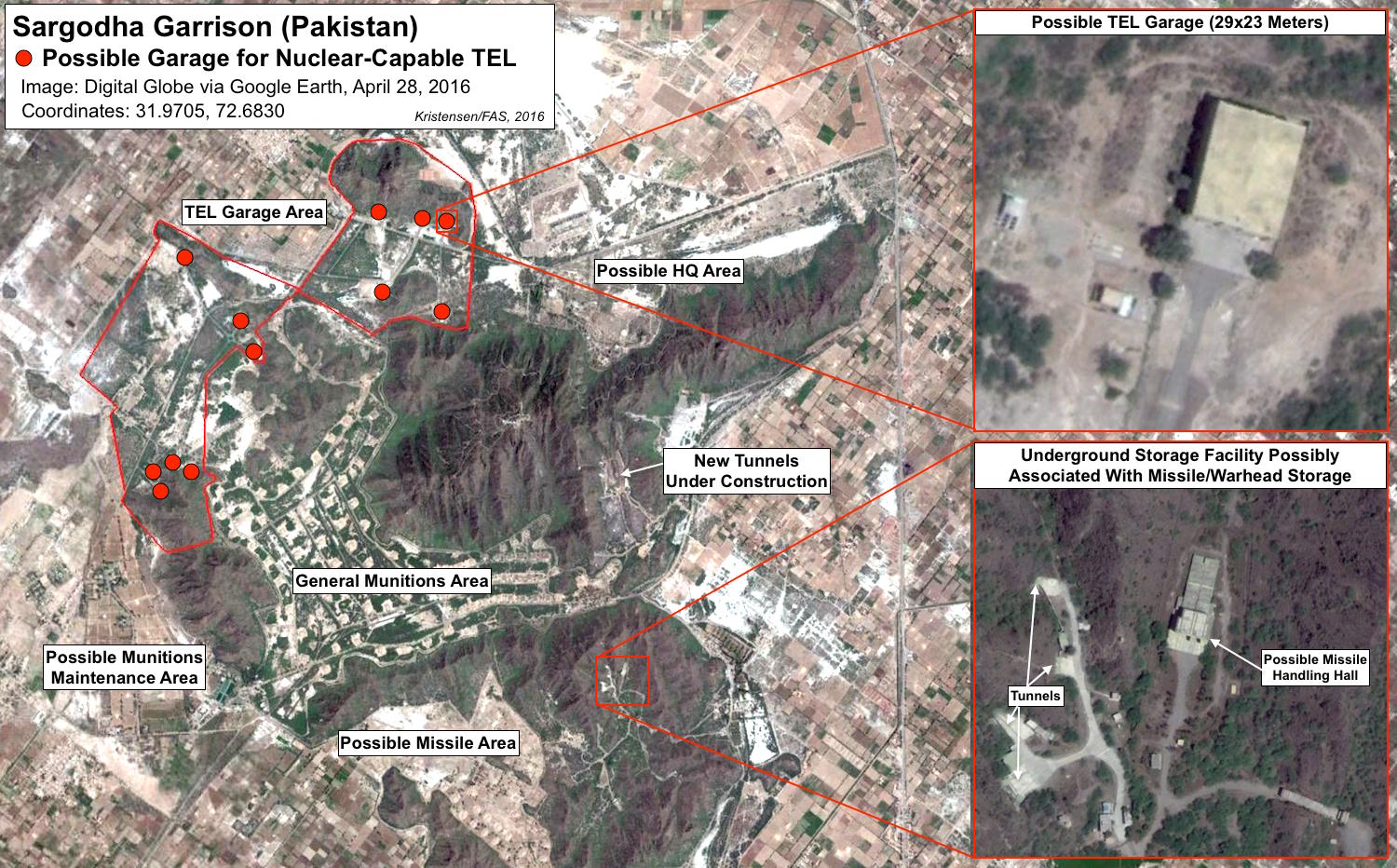

The total number and location of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable missile bases is not known. But analysis of commercial satellite photos has identified features that suggest that at least five bases might serve a role in Pakistan’s emerging nuclear posture. This includes army garrisons at Akro (Petaro), Gujranwala, Khuzdar, Pano Aqil, and Sargodha. A sixth base at Bahawalpur (29.2829, 71.7955) may be under construction. There is also a seventh base near Dera Ghazi Khan (29.9117, 70.4922), but the infrastructure is very different and not yet convincing.

An obvious difficulty in identifying nuclear missile bases is that the infrastructure is not yet publicly known, that commercial satellite photos do not have sufficient resolution to positively identify nuclear-capable launchers with certainty (especially smaller shorter-range types), that all launchers are dual-capable (not all bases with a certain launcher may have a nuclear role; and not all nuclear-capable launchers at a particular base may be assigned nuclear warheads), and that Pakistan (like other nuclear-armed states) most likely is engaged in considerable efforts to conceal and confuse identification of nuclear launchers.

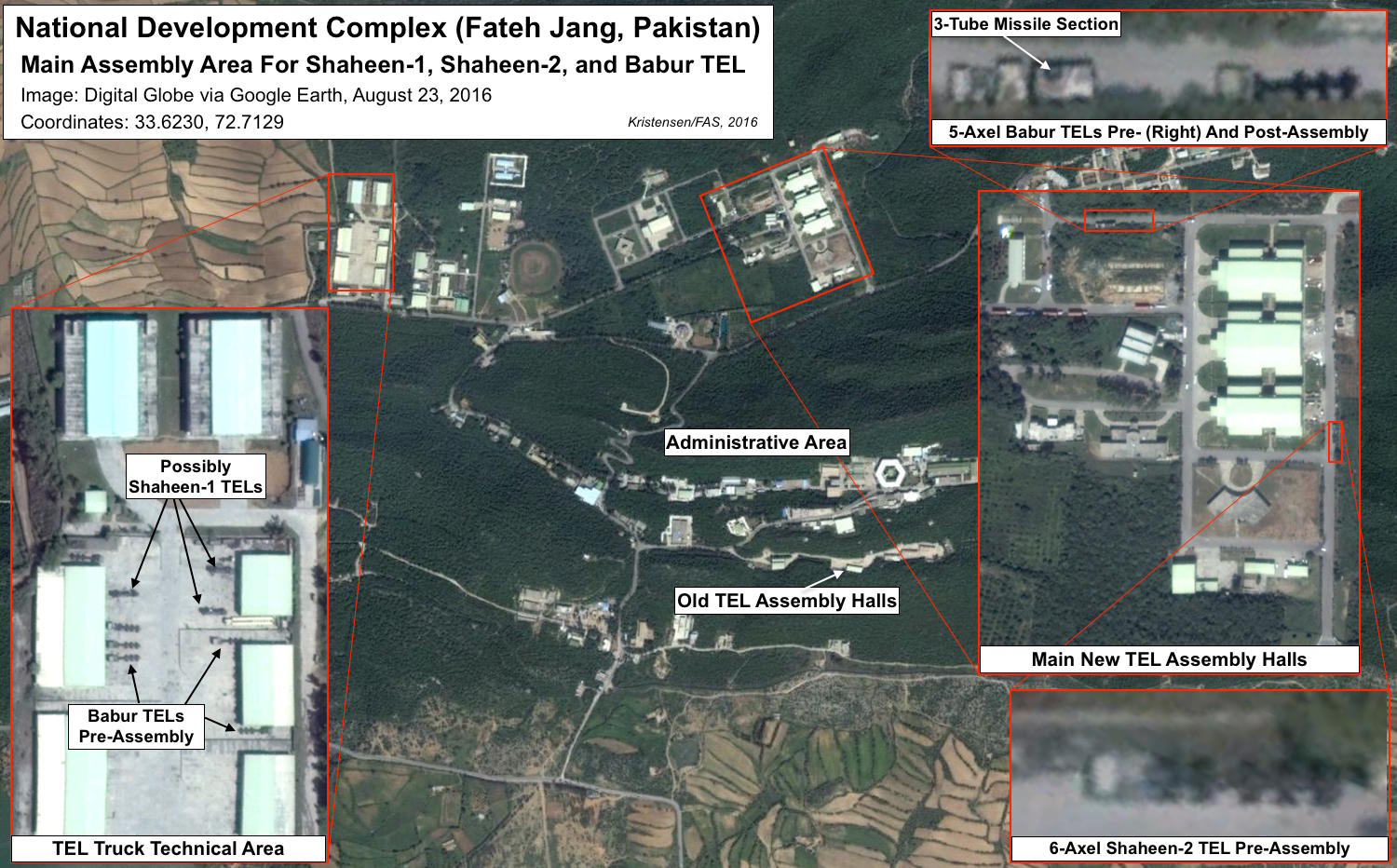

With these caveats, here is a description with images of what we consider to be the five primary nuclear-capable bases and the primary TEL (Transporter Erector Launcher) production facility in Pakistan:

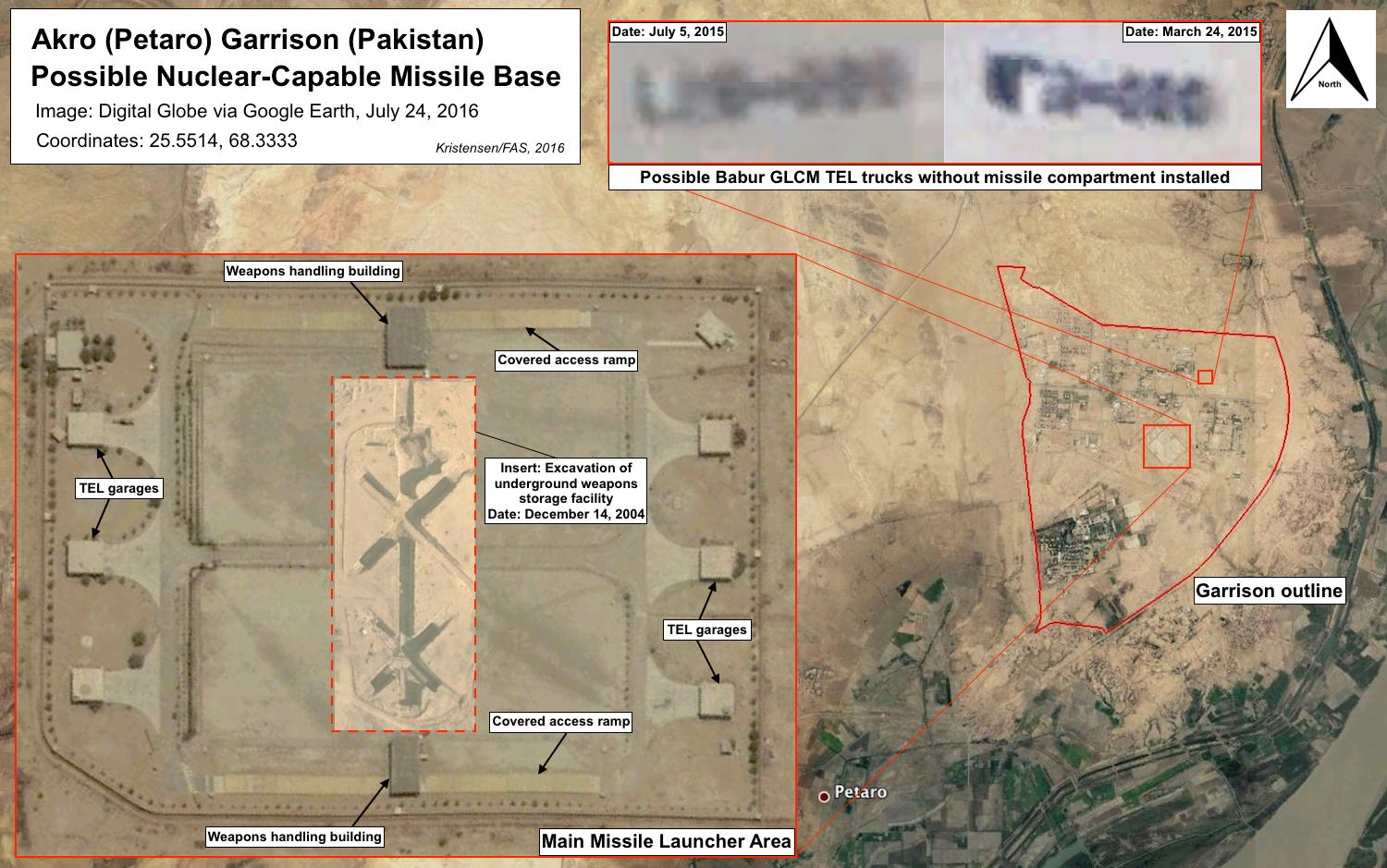

Akro Garrison: This base is located (25.5483, 68.3343) approximately 18 km (11 miles) north of Hyderabad between Akro and Petaro in the southern part of the Sindh Province approximately 145 kms (90 miles) from the Indian border. The garrison covers an area of 6.9 square kms (2.7 square miles) and has been expanded significantly since 2004 (the base was first pointed out to me by Martin Bulla, a German amateur satellite imagery enthusiast). The Akro Garrison includes a unique underground facility located under what appears to be a missile TEL garage complex. The underground facility consists of two star-shaped sections located along a central corridor that connects to two buildings with covered access ramps. The six TEL garages appear to be designed for 12 launchers.

The Akro Garrison has a TEL area with unique underground facility.

It is not possible to identify the suspected launchers in the TEL complex from the available photos. But analysis of a vehicle training area in the northeast corner of the garrison shows what appears to be five-axel TELs for the Babur cruise missile weapon system.

In a hypothetical crisis the launchers presumably would load their complement of missiles at the base and disperse outside to predetermined launch locations in the region. The range of the Babur is uncertain; NASIC reports it as 350 km (217 miles) while the Pakistan government claims a range of more than 500 kms (373 miles), sometimes as much as 700 kms (435 miles). The Akro unit would be able to defend all of the southeastern part of Pakistan, including Karachi.

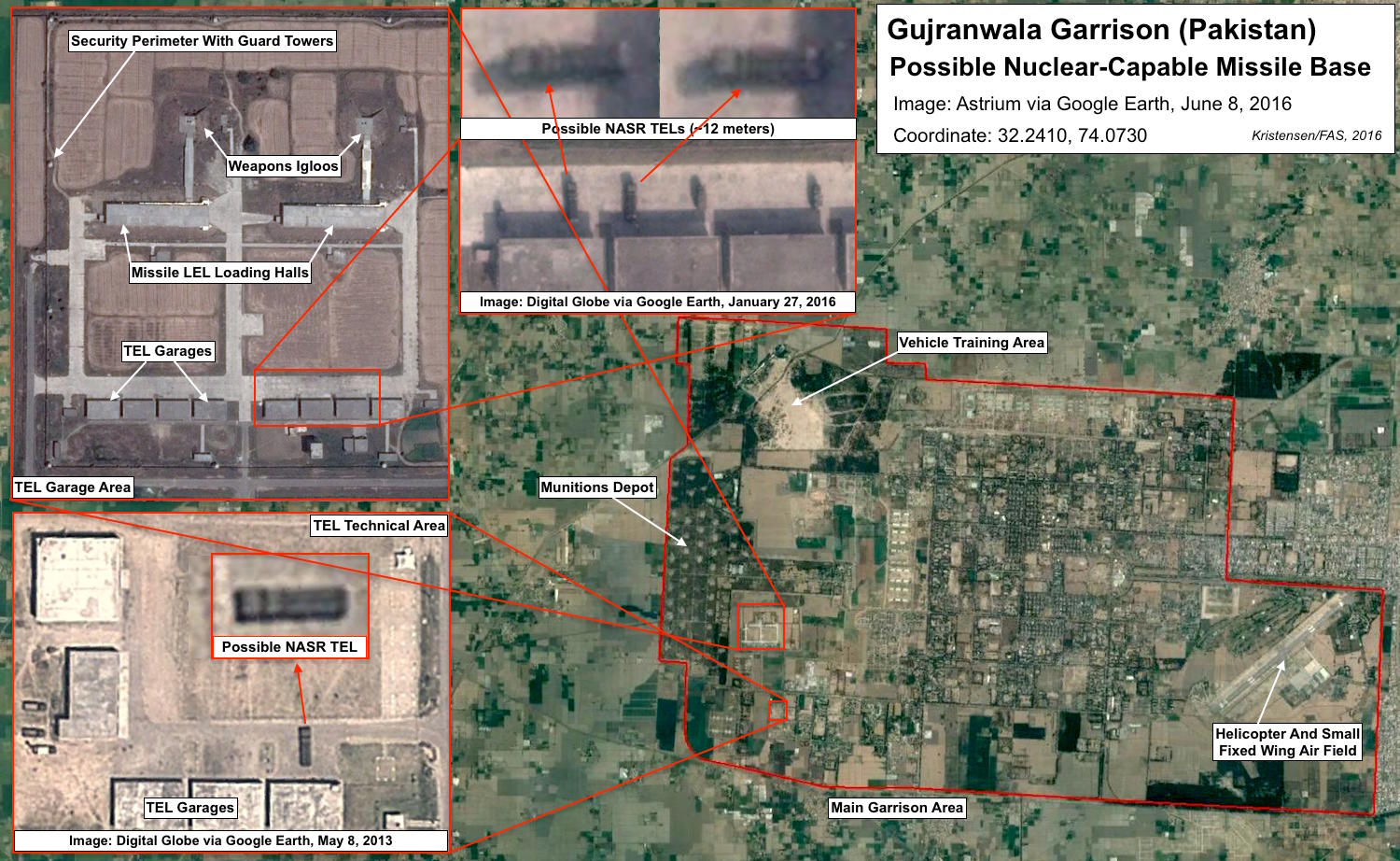

Gujranwala Garrison: This sprawling base complex covers an area of approximately 30 square kms (11.5 square miles) and is located (32.2410, 74.0730) in the northeastern part of the Punjab Province approximately 60 kms (37 miles) from the Indian border. Since 2010, the base has added what appears to be a TEL launcher area in the western part of the complex. There is also what appears to be a technical area for servicing the launchers. The TEL area became operational in 2014 or 2015. The TEL area appears to be made up of two identical sections (each consisting of launcher garages, a weapons loading hall, and a weapons storage igloo), each similar in design to the TEL area at Pano Aqil. The security perimeter appears to have room for a third TEL section. (This and other facilities have also been spotted by https://twitter.com/rajfortyseven.)

Gujranwala Garrison appears to be a base for the NASR tactical nuclear-capable launcher.