(The Other) Red Storm Rising: INDO-PACOM China Military Projection

Click on image to download PDF-version of full briefing

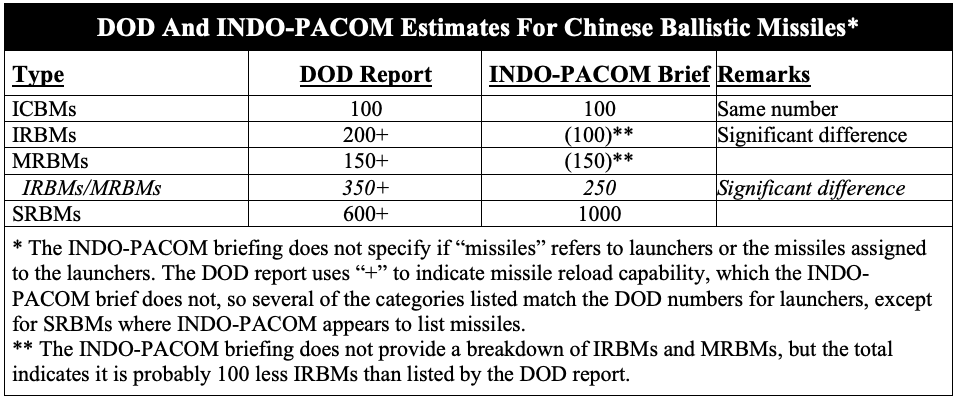

Some Missile Numbers Do Not Match Recent DOD China Report

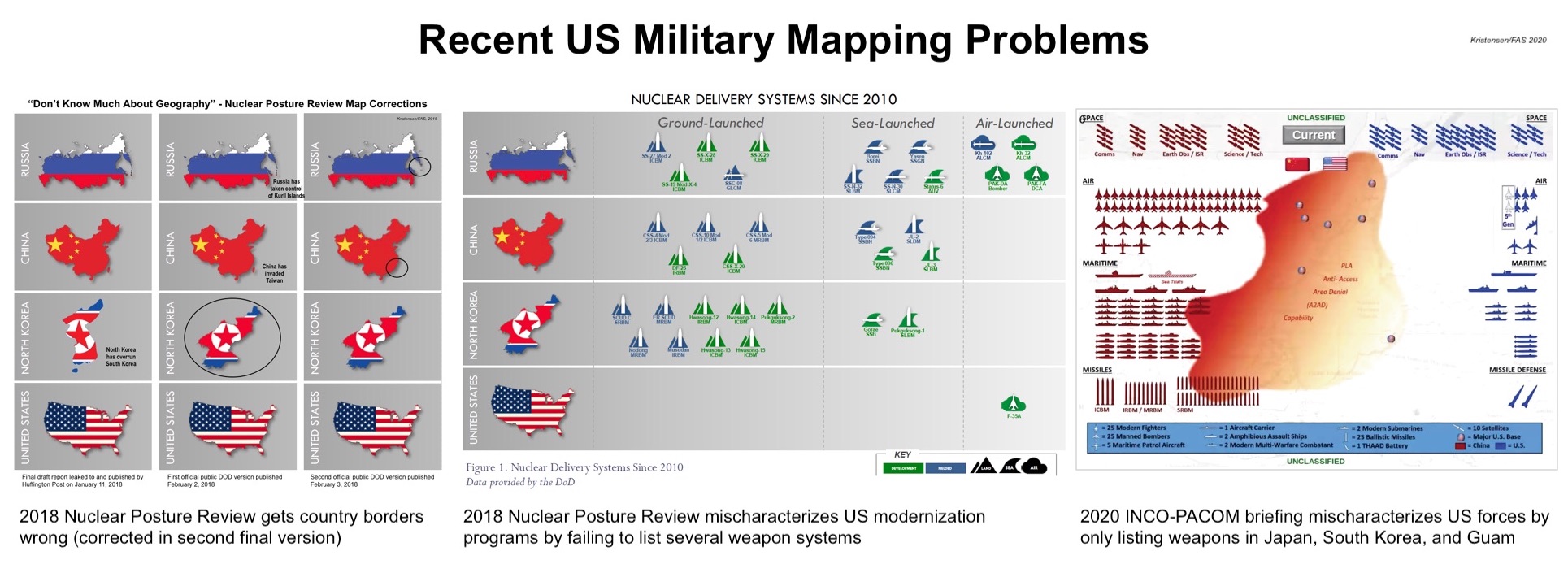

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command recently gave a briefing about the challenges the command sees in the region. The briefing says China is the “Greatest Threat to Global Order and Stability” and presents a set of maps that portray a massive Chinese military buildup and very little U.S. capability (and no Allied capability at all) to counter it. With its weapons icons and a red haze spreading across much of the Pacific, the maps resemble a new version of the Cold War classic Red Storm Rising.

Unfortunately, the maps are highly misleading. They show all of China’s forces but only a fraction of U.S. forces operating or assigned missions in the Pacific.

There is no denying China is in the middle of a very significant military modernization that is increasing its forces and their capabilities. This is and will continue to challenge the military and political climate in the region. For decades, the United States enjoyed an almost unopposed – certainly unmatched – military superiority in the region and was able to project that capability against China as it saw fit. The Chinese leadership appears to have concluded that that is no longer acceptable and that the country needs to be able to defend itself.

In describing this development, however, the INDO-PACOM briefing slides make the usual mistake of overselling the threat and under-characterizing the defenses. Moreover, some of the Chinese missile forces listed in the briefing differ significantly from those listed in the recent DOD report on Chinese military developments. As military competition and defense posturing intensify, expect to see more of these maps in the future.

Apples, Oranges, and Cherry-Picking

The INDO-PACOM maps suffer from the same lopsided comparison and cherry-picking that handicapped the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review: it overplays the Chinese capabilities and downplays the U.S. capabilities (see image below). While he briefing maps includes all of China’s military forces, whether they are postured toward India or Russia, it only shows a small portion of U.S. forces. INDO-PACOM mapmakers may argue that it’s only intended to show the force level in the Western Pacific theater, but INDO-PACOM spans all of the Pacific and the maps ignore other significant U.S. forces that are operating in the region to oppose China.

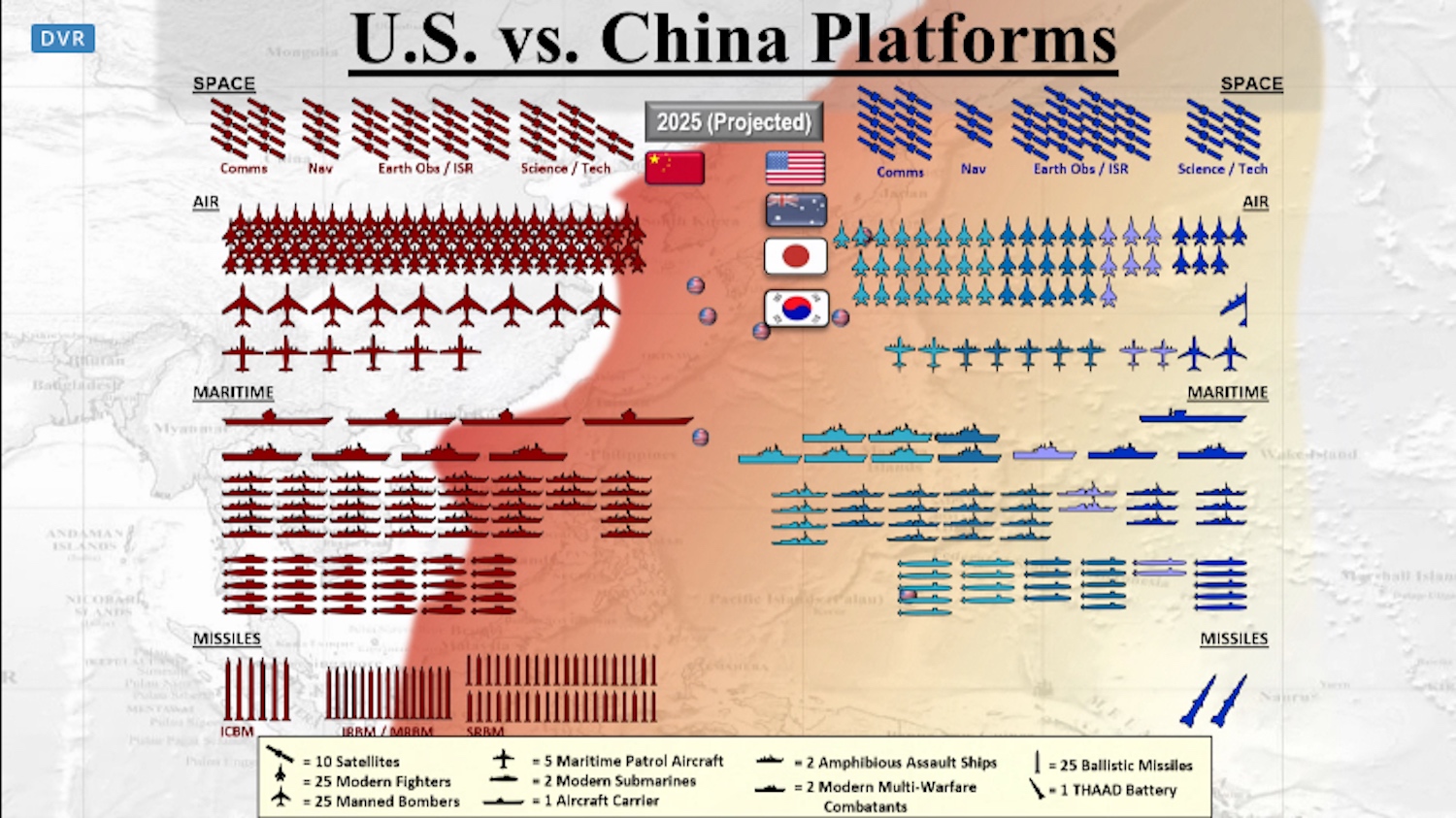

The INDO-PACOM map gives the impression that the United States only has 175 fighter-jets, 12 bombers, 50 maritime patrol aircraft, 1 aircraft carrier, four amphibious assault ships, 12 modern multi-warfare warships, 10 submarines, and 2 THAAD missile defense batteries in the region to deter China. In reality, the U.S. military forces based or assigned missions in the INDO-PACOM area of responsibility are significantly greater. The map excludes everything based in Hawaii, in Alaska, on the U.S. west coast, and elsewhere in the continental United States with missions in the Pacific or forces rotating through bases in the Indo-Pacific region. Examples of mischaracterizations of U.S. forces include:

Fighter aircraft: The map lists only lists 175 fighter-jets, but Pacific Air Forces says it has “Approximately 320 fighter and attack aircraft are assigned to the command with approximately 100 additional deployed aircraft rotating on Guam.”

Bombers: The map lists only 12 bombers, but the United States has more than 150 bombers, many of which would be used to counter Chinese forces in a war. Moreover, those bombers are considerably more capable than Chinese bombers and are supported by tankers to provide unconstrained range in the Pacific, something Chinese bombers cannot do.

Submarines: The map lists only 10 U.S. submarines, but according to the U.S. Naval Vessel Register the U.S. Navy has more than three times that many (35) in the Pacific, including 25 attack submarines, 2 guide missile submarines, and 8 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) homeported in Pacific ports. The omission of the 8 Pacific-based SSBNs is particularly problematic given their important role of targeting China – and that they are assigned up to eight times more nuclear warheads than China has in its entire nuclear weapons stockpile.

The INDO-PACOM briefing does not show that the United States has any ballistic missile submarines in the Pacific, even though eight U.S. Pacific-based SSBNs play a central role in targeting China. Just two of these Ohio-class SSBNs can carry more warheads than China has in its entire nuclear stockpile. This image shows the USS Pennsylvania (SSBN-735) during a port visit to Guam in 2016.

Aircraft carriers: The map lists only one U.S. aircraft carrier, but according to the U.S. Naval Vessel Register the U.S. Navy has six aircraft carriers based in the Pacific (two of them in shipyard). Moreover, unlike China’s single aircraft carrier (a second is fitting out), U.S. carriers are large flat-tops with more aircraft.

Amphibious assault ships: The map shows four U.S. amphibious assault ships, but the U.S. Pacific Fleet says it operates six (although one was recently damaged by fire). Moreover, the amphibious assault ships are being upgraded to carry the F-35B VSTOL aircraft, significantly improving their strike capability.

Missile defense: The map shows only two THAAD batteries but does not mention the Ground Based Midcourse missile defense system in Alaska. Nor are missile defense interceptors deployed on cruisers and destroyers listed.

ICBMs: One of the most glaring omissions is that the maps do not show the United States has any ICBMs (the map also does not list U.S. SLBMs but nor does it list Chinese SLBMs). Although U.S. ICBMs are thought to be mainly assigned to targeting Russia and would have to overfly Russia to reach targets in China, that does not rule out they could be used to target China (Chinese ICBMs would also have to overfly Russia to target the continental United States). U.S. ICBMs carry more nuclear warheads than China has in its entire nuclear stockpile.

The INDO-PACOM briefing shows China with 100 ICBMs and the United States with none. This infrared image shows a U.S. Minuteman III ICBM test-launched from Vandenberg AFB into the Pacific on September 2, 2020.

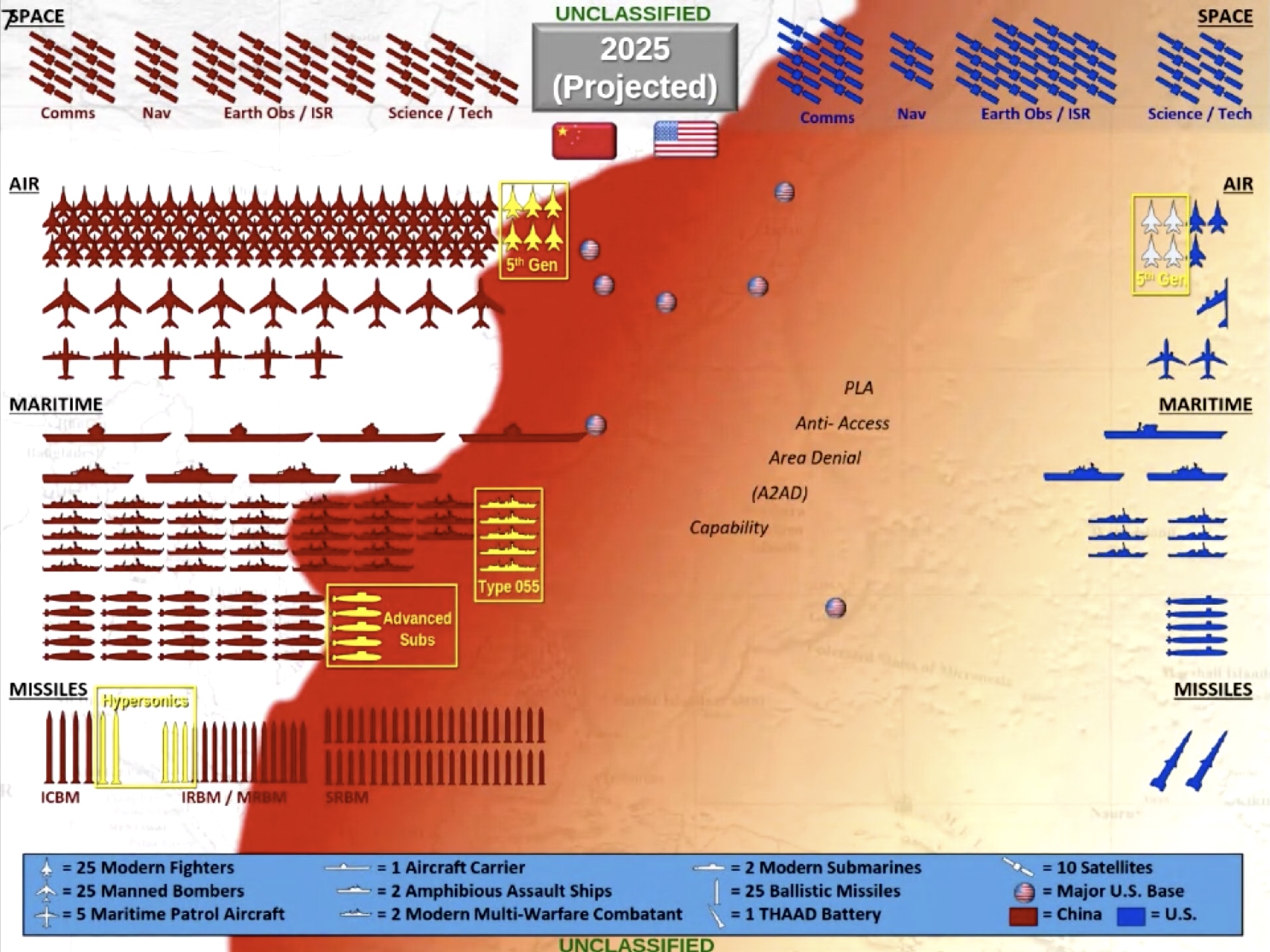

A modified map, apparently made available by U.S. Pacific Air Forces, is a little better because it includes Australian, Japanese, and South Korean forces. But it still significantly mischaracterizes the forces the United States has in the Pacific or are assigned missions in the region. Moreover, the new map does not include the yellow highlights showing “hypersonics” missiles and portion of aircraft, ships, and submarines that are modern (see modified map below).

A modified map released after the INDO-PACOM briefing also shows Australian, Japanese, and South Korean forces – but still mischaracterizes U.S. military forces in the Pacific.

Inconsistent Missile Numbers

The INDO-PACOM maps are also interesting because the numbers for Chinese IRBMs and MRBMs are different than those presented in the 2020 DOD report on Chinese military developments. INDO-PACOM lists 250 IRBMs/MRBMs, more than 100 missiles fewer than the DOD estimate. China has fielded one IRBM (DF-26), a dual-capable missile that exists in two versions: one for land-attack (most DF-26s are of this version) and one for anti-ship attack. China operates four versions of the DF-21 MRBM: the nuclear DF-21A and DF-21E, the conventional land-attack DF-21C, and the conventional anti-ship DF-21D.

There is also a difference in the number of SRBMs, which INDO-PACOM sets at 1,000, while the DOD report lists 600+. The 600+ could hypothetically be 1,000, but the INDO-PACOM number shows that the high-end of the 750-1,500 range reported by the 2019 DOD China report probably was too high.

A comparison (see table below) is complicated by the fact that the two reports appear to use slightly different terminology, some of which seems inconsistent. For example, INDO-PACOM lists “missiles” but the low IRBM/MRBM estimate suggests it refers to launchers. However, the high number of SRBMs listed suggest it refers to missiles.

Several of the Chinese missile estimates provided by INDO-PACOM and DOD are inconsistent.

2025 Projection

The projection made by INDO-PACOM for 2025 shows significant additional increases of Chinese forces, except in the number of SRBMs.

The ICBM force is expected to increase to 150 missiles from 100 today. That projection implies China will field an average of 10 new ICBMs each year for the next five years, or about twice the rate China has been fielding new ICBMs over the past two decades. Fifty ICBMs corresponds to about four new brigades. About 20 of the 50 new ICBMs are probably the DF-41s that have already been displayed in PLARF training areas, military parades, and factories. The remaining 30 ICBMs would have to include more DF-41s, DF-31AGs, and/or the rumored DF-5C, but it seems unlikely that China can add enough new ICBM brigade bases and silos in just five years to meet that projection.

The briefing also projects that 50 of the 150 ICBMs by 2025 will be equipped with “hypersonics.” The reference to “hypersonics” as something new is misleading because existing ICBMs already carry warheads that achieve hypersonic speed during reentry. Instead, the term “hypersonics” probably refers to a new hypersonic glide vehicle. It is unclear from the briefing if INDO-PACOM anticipates the new payload will be nuclear or conventional, but a conventional ICBM payload obviously would be a significant development with serious implications for crisis stability. Even if this expansion comes true, the entire Chinese ICBM force would only be one-third of the size of the U.S. ICBM force. Nonetheless, a Chinese ICBM force of 100-150 is still a considerable increase compared with the 40 or so ICBMs it operated two decades ago (see graph below).

The INDO-PACOM briefing appears to show a greater increase in ICBMs projected for the next five years than DOD reported in the past decade.

The IRBM/MRBM force is projected to increase to 375, from 250 today. That projection assumes China will field 125 additional missiles over five years, or 25 missiles each year. That corresponds to a couple of new brigades per year, which seems high. Yet production is significant and IRBM launchers have been seen in several regions in recent years. The IRBM/MRBM force presumably would include the DF-17, DF-21, and the DF-26.

About 75-87 of the IRBM/MRBM force will be equipped with “hypersonics” by 2025, according to INDO-PACOM. That projection probably refers to the expected fielding of the DF-17 with a new glide-vehicle payload, although that would imply a lot of the new launcher (enough for 4-6 brigades). Another possibly is that a portion of other IRBMs/MRBMs (perhaps the DF-26) might also be equipped with the new payload or have their own version. China has presented the DF-17 as conventional but STRATCOM has characterized it as a “new strategic nuclear system.” Adding new hypersonics to IRBMs/MRBMs that are already mixing nuclear and conventional seems extraordinarily risky and likely to further exacerbate the danger of misunderstandings.

The INDO-PACOM does not list any DF-17s but projects that 75-87 of China’s IRBMs/MRBMs by 2025 will carry some form of hypersonic payload that is different from what they carry today.

The status and projection for the surface fleet are also interesting. The INDO-PACOM briefing lists the total number of aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, and modern multi-warfare combatant vessels at 54, of which 46 are modern multi-warfare combatant vessels. The briefing doesn’t specify what is excluded from this count, but it differs significantly from the count in the DOD China report.

One of the puzzling parts of the INDO-PACOM briefing is the projection that China by 2025 will be operating four aircraft carriers for fixed-wing jets. China is currently operating one carrier with a second undergoing sea-trials. How China would be able to add another three carriers in five years is a mystery, not least because the third and fourth hulls are of a new and more complex design. The projection also doesn’t fit with the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, which predicts the third carrier won’t be commissioned until 2024.

The INDO-PACOM briefing says China will operate four aircraft carriers by 2025 but ONI estimates the third won’t be commissioned until 2024.

Bombers are projected to increase from 175 today to 225 in 2025, an increase of nearly 30 percent. Since 2025 is probably too early for the new H-20 to become operational, the increase appears to only involve modern version of the H-6 bomber. Although the bomber force has recently been reassigned a nuclear mission, the majority of the Chinese bomber force will likely continue to be earmarked for conventional missions.

Submarines and surface vessels will also increase and some of them are being equipped with long-range missiles. Combined with the growing reach of ground-based ballistic missiles and air-delivered cruise missiles, this results in the INDO-PACOM maps showing a Chinese “anti-access area denial” (A2AD) capability bleeding across half of the Pacific well beyond Guam toward Hawaii. But A2AD is not a bubble and weakens significantly in areas further from Chinese shores.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The INDO-PACOM maps project China’s military modernization will continue at a significant pace over the next five years with increases in delivery platforms and capabilities. This will reduce the military advantage the United States has enjoyed over China for decades and further stimulate modernization of U.S. and allied military forces in the region. As forces grow, operations increase, and rhetoric sharpens, insecurity and potential incidents will increase as well and demand new ways of reducing tension and risks.

The Trump administration is correct that China should be included in talks about limiting forces and reducing tension. So far, however, the administration has not presented concrete ideas for what that could look like. Like the United States, China will not accept limits on its forces and operations without something in return that Beijing sees as being in its national interest. Although China is modernizing its nuclear forces and appears intent on increasing it further over the next decade, the force will remain well below the level of the United States and Russia for the foreseeable future. Insisting that China should join U.S.-Russian nuclear talks seems premature and it is still unclear what the United States would trade in return for what. In the near-term, it seems more important to try to reach agreements on limiting the increase of conventional forces and operations.

Unfortunately, the INDO-PACOM briefing does a poor job in comparing Chinese and U.S. forces and suffers from the same flaw as the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review by cherry-picking and mischaracterizing force levels. It is tempting to think that this was done with the intent to play up the Chinese threat while downplaying U.S. capabilities to assist public messaging and defense funding. But the Chinese military modernization is important – as is finding the right response. Neither the public nor the Congress are served by twisted comparisons.

It would also help if the Pentagon and regional commands would coordinate and streamline their public projections for Chinese modernizations. Doing so would help prevent misunderstandings and confusion and increase the credibility of these projections.

Finally, these kinds of projections raise a fundamental question: why does the Pentagon and regional military commands issue public threat projections at all? That should really be the role of the Director of National Intelligence, not least to avoid that U.S. public intelligence assessments suffer from inconsistencies, cherry-picking, and short-term institutional interests.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Russian Pacific Fleet Prepares For Arrival of New Missile Submarines

Later this fall (possibly this month) the first new Borei-class (sometimes spelled Borey) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) is scheduled to arrive at the Rybachiy submarine base near Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

[Update September 30, 2015: Captain First Rank Igor Dygalo, a spokesperson for the Russian Navy, announced that the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550) arrived at Rybachiy Submarine Base at 5 PM local time (5 AM GMT) on September 30, 2015.]

At least one more, possibly several, Borei SSBNs are expected to follow over the next few years to replace the remaining outdated Delta-III SSBNs currently operating in the Pacific.

The arrival of the Borei SSBNs marks the first significant upgrade of the Russian Pacific Fleet SSBN force in more than three decades.

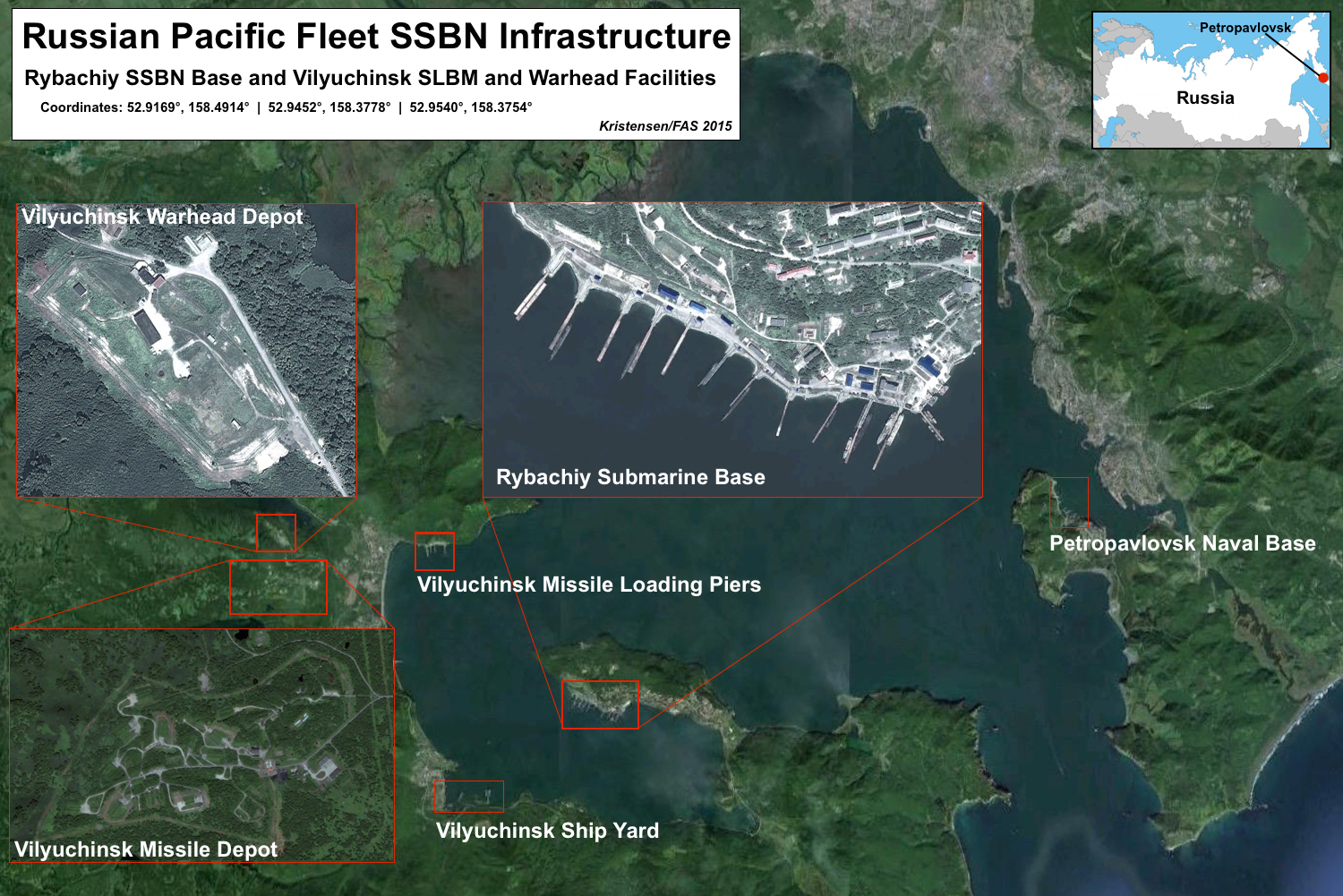

In preparation for the arrival of the new submarines, satellite pictures show upgrades underway to submarine base piers, missile loading piers, and nuclear warhead storage facilities.

Several nuclear-related facilities near Petropavlovsk are being upgraded.

Upgrade of Rybachiy Submarine Base Pier

Similar to upgrades underway at the Yagelnaya Submarine Base to accommodate Borei-class SSBNs in the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula, upgrades visible of submarine piers at Rybachiy Submarine Base are probably in preparation for the arrival of the first Borei SSBN – the Aleksandr Nevskiy (K-550) in the near future (see below).

Upgrades at Rybachiy submarine base.

Commercial satellite images from 2014 show a new large pier under construction. The pier includes six large pipes, probably for steam and water to maintain the submarines and their nuclear reactors while in port.

The image also shows two existing Delta III SSBNs, one with two missile tubes open and receiving service from a large crane. Other visible submarines include a nuclear-powered Oscar-II class guided missile submarine, a nuclear-powered Victor III attack submarine, and a diesel-powered Kilo-class submarine.

The arrival of the Borei-class in the Pacific has been delayed for more than a year because of developmental delays of the Bulava missile (SS-N-32) and the SSBN construction program. Russian Deputy Defence Minister Ruslan Tsalikov recently visited the base and promised that infrastructure and engineering work for the Borei-class SSBNs would be completed in time for the arrival of the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550). Predictions for arrival range from early- to late-September 2015.

Upgrade of Missile Depot Loading Pier

When not deployed onboard SSBNs, sea-launched ballistic missiles and their warheads are stored at the Vilyuchinsk missile deport and warhead storage site across the bay approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) east-northwest of the Rybachiy submarine base. To receive and offload missiles and warheads, an SSBN will moor at one of two piers where a large floating crane is used to lift missiles into or out of the submarine’s 16 launch tubes.

Upgrades of Vilyuchinsk missile loading piers.

Satellite images show that a larger third pier is under construction possibly to accommodate the Borei SSBNs and the Bulava SLBM loadings (see above). This will also provide additional docking space for both submarines and surface ships that use the facility.

SS-N-18 handling at Vilyuchinsk missile loading pier.

The missile depot itself includes approximately 60 earth-covered bunkers (igloos) and a number of service facilities located inside a 2-kilometer (1.3- mile) long, multi-fenced facility covering an area of 2.7 square kilometer (half a square mile). The igloos have large front doors that allow SLBMs to be rolled in for horizontal storage inside the climate-controlled facilities (see image below).

Vilyuchinsk missile depot.

In addition to SLBMs for SSBNs, the depot probably also stores cruise missiles for attack submarines and surface ships. A supply ship will normally load the missiles at Vilyuchinsk and then deliver them to the attack submarine or surface ship back at their base piers. However, most of the Russian surface fleet in the Pacific is based at Vladivostok, some 2,200 kilometers (1,400 miles) to the southwest near North Korea, and has its own nuclear weapons storage sites.

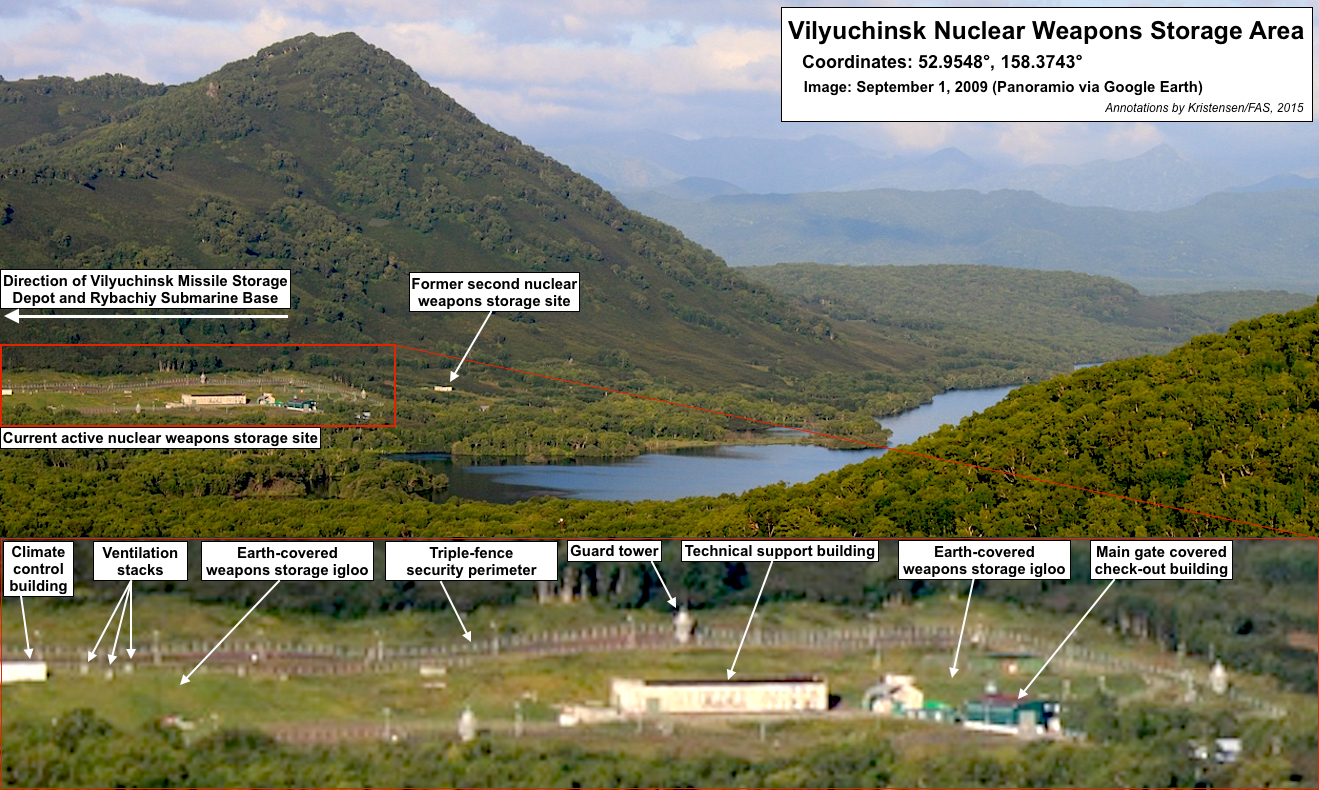

Upgrade of Warhead Storage Site

When not mated with SLBMs onboard the SSBNs, nuclear warheads appear to be stored at a weapons storage facility north of the missile depot. The facility, which includes two earth-covered concrete storage bunkers, or igloos, inside a 430-meter (1,500-foot) long 170-meter (570-foot) wide triple-fenced area, is located on the northeastern slope of a small mountain next to a lake north of the missile depot. A third igloo outside the current perimeter probably used to store nuclear warheads in the past when more SSBNs were based at Rybachiy (see image below).

Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons storage area.

Satellite images show that the nuclear weapons storage site is under major renovation. The work started sometime after August 2013. By September 2014, one of the two igloos inside the security perimeter had been completely exposed revealing an 80×25-meter (263×82-foot) underground structure. The structure has two access tunnels and climate control (see below).

Upgrade of Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons storage area.

A later satellite image taken on November 1, 2014 reveals additional details of the storage facility. Rather than one large storage room, it appears to be made up of several rooms. One of the internal structures is about 37 meters (82 feet) long. A 30-meter (90 feet) long and 10-meter (30 feet) wide tunnel that connects the storage section with the main square of the site is being lengthened with new entry building. It is not possible to determine from the satellite images how deep the structure is but it appears to be at least 25 meters (see image below).

Upgrade of Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons igloo.

The weapons storage facility is likely capable of storing several hundred nuclear warheads. Each Delta-III SSBN based at Rybachiy can carry 16 SLBMs with up to 48 warheads. In recent years the Pacific Fleet has included only 2-3 Delta IIIs with a total of 96-144 warheads, but there used be many more SSBNs operating from Rybachiy. Each new Borei-class SSBN is capable of carrying twice the number of warheads of a Delta III and so far 2-3 Borei SSBNs are expected to transfer to the Pacific over the next few years.

To arm the SLBMs loaded onto submarines at the missile-loading pier, the warheads are first loaded onto trucks at the warheads storage facility and then driven the 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) down the road to the entrance of the missile depot. During storage site renovation the warheads that are not onboard the SSBNs are probably stored in the second igloo inside the security perimeter or temporarily at the missile depot.

Implications and Recommendations

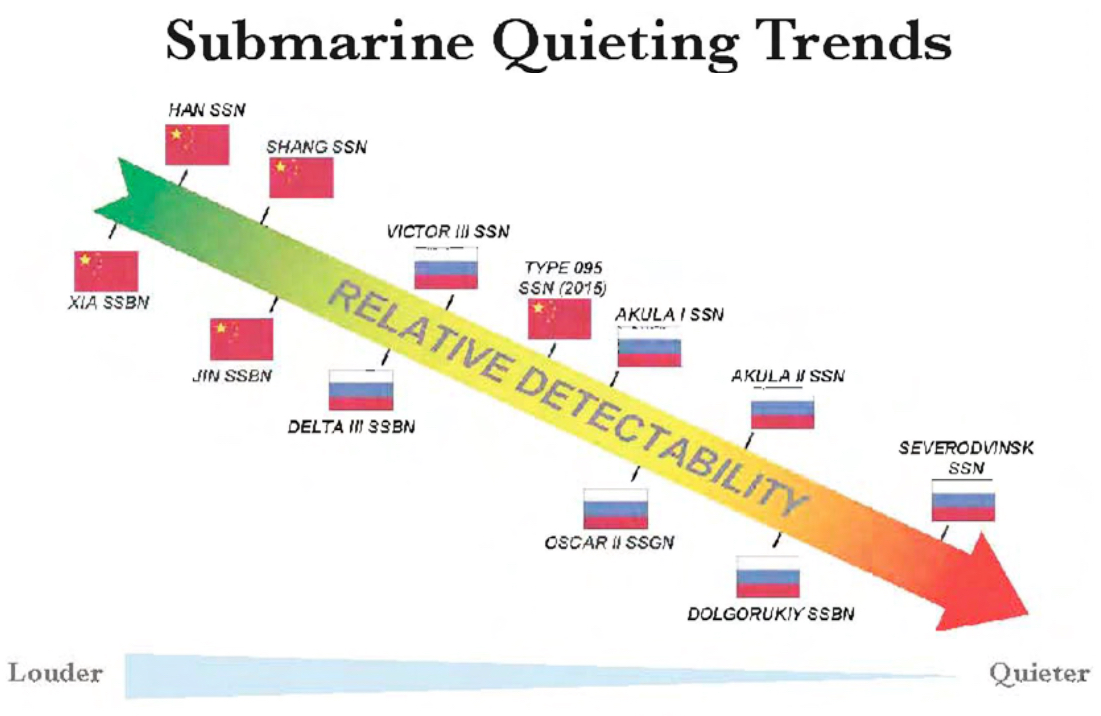

The expected arrival of the Borei SSBNs at the Rybachiy submarine base marks the first significant upgrade of the Russian Pacific Fleet SSBN force in more than three decades. The new submarines will have implications for strategic nuclear operations in the Pacific: they will be quieter and capable of carrying more nuclear warheads than the current class of Delta III submarines.

The Borei-class SSBN is significantly quieter than the Delta III and quieter than the Akula II-class attack submarine. A Delta III would probably have a hard time evading modern U.S. and Japanese anti-submarine forces but the Borei-class SSBN would be harder to detect. Even so, according to a chart published by the US Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence, the Borei-class SSBN is not as quiet as the Severodvinsk-class (Yasen) attack submarine (see graph below).

Nuclear submarine noise levels. Credit: US Navy Office of Naval Intelligence.

The Borei-class SSBN is equipped with as many SLBMs (16) as the Delta III-class SSBN. But the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM on the Borei can carry twice as many warheads (6) as the SS-N-18 SLBM on the Delta III and is also thought to be more accurate. How many Borei-class SSBNs will eventually operate from Rybachiy remains to be seen. After the arrival of Alexander Nevsky later this year, a second is expected to follow in 2016. A total of eight Borei-class SSBNs are planned for construction under the Russian 2015-2020 defense plan but more could be added later to eventually replace all Delta III and Delta IV SSBNs.

With its SSBN modernization program, Russia is following the examples of the United States and China, both of which have significantly modernized their SSBN forces operating in the Pacific region over the past decade and a half.

The United States added the Trident II D5 SLBM to its Pacific SSBN fleet in 2002-2007, replacing the less capable Trident I C4 first deployed in the region in 1982. The D5 has greater range and better accuracy than its predecessor and also carries the more powerful W88 warhead. Unlike the C4, the D5 has full target kill capability and has significantly increased the effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific. Today, about 60 percent of all U.S. SSBN patrols take place in the Pacific, compared with the Cold War when most patrols happened in the Atlantic. The US Navy has announced plans to build 12 new and improved SSBNs and there are already rumors that Russia may build 12 Borei SSBNs as well.

China, for its part, has launched four new Jin-class SSBNs designed to carry the new Julang-2 SLBM. The Julang-2 (JL-2) has longer range and greater accuracy than its predecessor, the JL-1 developed for the unsuccessful Xia-class SSBN.

Combined, the nuclear modernization programs (along with the general military build-up) in the Pacific are increasing the strategic importance of and military competition in the region. The Borei-class SSBNs at Rybachiy will sail on deterrent patrols into the Pacific officially to protect Russia but they will of course also be seen as threatening other countries. Rather than sailing far into the Pacific, the Boreis will most likely be deployed in so-called bastions near the Kamchatka Peninsula where Russian attack submarines will try to protect them against U.S. attack submarines – the most advanced of which are being deployed to the Pacific.

And so, the wheels of the nuclear arms race make another turn…

For more information, see: Russian Nuclear Forces 2015

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.