Missile Mystery in Beijing

|

| The mysterious DF-41 missile did not appear at the Chinese National Day parade on October 1st, but the Chinese Ministry of National Defense says the DF-31A did. But did it, or was it in fact the DF-31? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The military parade at China’s 60th National Day celebration last week was widely rumored to be displaying a new long-range ballistic missile described in the news media as the DF-41. The rumors turned out to be, well, rumors.

Instead the Chinese Ministry of National Defense identified two other missiles: the nuclear DF-31A and the conventional DF-21C, to my knowledge a first.

But was it the DF-31A that rolled across the square or the shorter-range DF-31 already displayed ten years ago at the 1999 parade?

What Was Displayed: DF-31A or DF-31?

The Chinese Ministry of National Defense web site carries several pictures (backup copy here) that identify the DF-31A, the long-range version of the DF-31 mobile ICBM, taking part in the parade. No DF-31s were identified. The U.S. intelligence community estimates that the DF-31A with a range of 11,200+ kilometers (6,959+ miles) is capable of striking targets throughout the United States and Europe. The missile is thought to carry a single warhead, was first deployed in 2007, and less than 15 are currently deployed.

The identification is curious because the DF-31A mobile launcher displayed in the 2009 parade is almost identical to the DF-31 launcher displayed in the 1999 parade. I’ve been going through all my images of Chinese mobile launchers and I cannot see any significant difference between the two. The only apparent difference is that the eight-axle truck has been upgraded and painted. But the missile canister on the “DF-31A” launcher appears to have the same dimensions as the one on the DF-31 launcher (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: |

|

| The DF-31A launcher identified by the Chinese Ministry of Defense at the 2009 parade (top) is almost identical to the DF-31 launcher displayed at the 1999 parade (bottom). Do the two missiles use a common mobile launcher or did the Chinese government re-display the DF-31? Images: Chinese Ministry of National Defense |

.

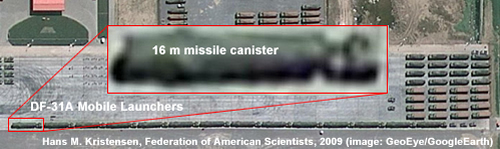

And it’s not as if there were two different long-range missile launchers in the area. A satellite image taken on June 23, 2009, and first described in China Brief, shows what appears to be the military vehicles rehearsing at Tongxian Air Base in the outskirts of Beijing in preparation for the parade. A line-up of 14 mobile launchers for long-range missiles all appear to have the same overall dimensions, including a 16-meter missile canister, and appear to be the “DF-31A” launchers identified in the parade (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Fourteen vehicles of what the Chinese Ministry of National Defense says are DF-31A missiles launchers lined up at Tongxian Air Base prior to the 2009 National Day parade all appear to have the same overall dimensions. Image: DigitalGlobe/Google Earth |

.

Do the DF-31 and DF-31A use the same or a very similar mobile launcher? Or were the launchers displayed in Beijing in fact DF-31s but misidentified on Chinese television and the Chinese Ministry of National Defense web site as DF-31As? It’s hard to imagine the Ministry misidentifying the DF-31 as the DF-31A. But although there are no official public comparisons of the two missiles and their launchers (except the DF-31 has two stages and the DF-31A has three), the DF-31A is assumed to be longer than the DF-31 – 18 meters versus 13 meters, according to Jane’s Strategic Weapons Systems. If so, the launchers displayed at the parade were too short for the DF-31A and must have been for the DF-31.

The Mysterious DF-41 (or still-to-be-seen DF-31A)?

The news media widely reported that the DF-41 would be displayed at the parade. The rumors about the missile seem to have fed off private web sites that claim the existence of a missile called DF-41. There is no official confirmation of this missile and a 2009 report from the U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Agency does not list a DF-41 missile or any other new Chinese long-range ballistic missile under development even though it lists new missiles under development by other countries.

The rumors about the DF-41 were so prevailing that an interviewer on the Chinese CCTV 4 Focus Today program the day before the parade kept asking Major General Zhang Xinan, the Assistant Director of the Second Artillery Corps’ Political Department, about the missile. But the General appeared to caution about what he called the “so-called DF-41,” saying that “this mystery will be cleared up tomorrow in the parade.” He did not dismiss the existence of a DF-41, but no such missile launcher rolled across the square.

Even so, photos have been circulating on the web for several years allegedly showing what appear to be a Chinese mobile missile launcher that is clearly different from the DF-31. Many have speculated that the launcher is for the elusive DF-41. Is it, or could this be the launcher for the DF-31A, or something completely different?

|

DF-31A or DF-41 Mobile Launcher? |

|

| Images of a Chinese eight-axle mobile missile launcher have circulated on the web for years, said to be for the DF-41 missile. Is it, or is it for the DF-31A, or something else? Images: Web |

.

The JL-2 Payload

Finally, although the Chinese Navy’s new Julang-2 sea-launched ballistic missile was not displayed at the parade, the CCTV 4 Focus Today program interviewed Du Wenlong, identified as a “researcher” from the Chinese Academy of Military Science, who said the JL-2 “penetration capability and number of carried warheads have been raised to a large degree” compared with the JL-1.

The JL-2 is expected to carry some form of penetration aids, but it would be a surprise if it carries more than one warhead. Whether the “researcher” is in a position where he would know what JL-2 will carry or is talking in general terms is unclear, but the U.S. intelligence community has consistently – most recently in June this year – assessed that the JL-2 carries a single warhead.

Final Observations

It would be interesting if the DF-31 and DF-31A use a similar mobile launcher. It would mean that estimates of an 18-meter DF-31A are wrong; the missile would have to be less than 16 meters to fit inside the launcher that was displayed at the parade as the DF-31A. A common launcher would have some serious implications for crisis stability in a hypothetical war between China and the United States because a launch of a DF-31 against regional targets initially could be misinterpreted by the U.S. military as a nuclear attack on the U.S. mainland, and lead to further escalation of the war.

But it would certainly be curious if the Chinese Ministry of National Defense claimed to display the DF-31A but instead re-displayed the DF-31.

CTBT Article XIV Conference

by: Alicia Godsberg

This past Thursday and Friday marked the 6th bi-annual Article XIV Conference, the Conference on Facilitating the Entry Into Force of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT). This year’s conference was held at the United Nations in New York and was met with a measure of cautious optimism – most states voiced their appreciation of President Obama’s pledge to work toward US ratification of the CTBT, while many states recognized the challenges of obtaining all the necessary ratifications for entry into force of the Treaty and mentioned the challenges to the nonproliferation regime stemming from the lack of the Treaty’s entry into force (despite former commitments to do so) and from the DPRK’s 2006 and 2009 nuclear tests.

Entry into force of the CTBT has been on the international agenda for thirteen years. Because the US, China, UK, France, and Russian Federation have all imposed a voluntary moratorium on national nuclear testing, many question the need for entry into force of the CTBT. Although the Treaty would bring few new tangible benefits, the political impact of entry into force would be tremendous. As explained below, the vast majority of sates see entry into force of the CTBT as somewhat of a litmus test for the future viability of the nonproliferation regime.

The CTBT was opened up for signature in 1996 and since then the Treaty has obtained 181 signatories and 150 ratifications. In order for the Treaty to enter into force, 44 states mentioned in annex II of the Treaty must ratify. As of today, only 35 of these states have ratified the Treaty, leaving the full implementation of the Treaty in the hands of the remaining nine states.[i] The Treaty has an extensive verification system that is continuing to be built and includes 321 monitoring stations and 16 laboratories in 89 countries that make up an International Monitoring System (IMS). This system is now approximately 85% operational and since 2000 has been transmitting data to an International Data Center (IDC) to be interpreted and shared with all signatories to the Treaty. The IMS provides valuable data for civilian applications, such as advance tsunami warnings, but the main focus of the IMS is detection and attribution of nuclear test explosions. The system was proven effective even without the CTBT entering into force after collecting and interpreting data from both of the recent DPRK nuclear tests. However, the option of imposing intrusive on-site inspections is necessary for an extra layer of investigation into the attribution of nuclear explosions. According to the terms of the CTBT this option cannot be exercised before the Treaty enters into force, and is one main reason for the need to obtain the remaining nine “annex II” state ratifications.

Entry into force of the CTBT is also important, as many states reiterated at this latest conference, because the early entry into force of the CTBT was one of the conditions under which the non-nuclear weapon states parties (NNWS) to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) agreed to indefinitely extend the NPT in 1995. Similarly, at the 2000 NPT Review Conference, early entry into force of the CTBT was the first of 13 Practical Steps toward nuclear disarmament that was adopted by consensus by all states parties to the NPT that year. Nuclear weapon states parties to the NPT (NWS) have all signed the CTBT, but China and the US have not ratified the Treaty. President Obama has pledged to work toward US ratification, but it seems he is going to have to fight to get the 67 votes he needs in the Senate to do so. Indonesia, also an annex II state, recently publicly stated that once the US ratifies the CTBT they will follow with ratification, and it is likely that China will follow US ratification as well. Ratification of the CTBT by the last two NWS before the NPT Review Conference in May 2010 would be an important first step toward fulfilling NWS’s political commitments and legal obligations to NNWS. US and China’s ratifications of the CTBT could set the tone for cooperation on President Obama’s nonproliferation agenda and perhaps even on the sensitive topic of the control of the nuclear fuel cycle at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May.

If you go here and read a random selection of statements from the Article XIV Conference, you will find that most states are looking to the US to fulfill its past promises and to take up the leadership position on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament, about which President Obama speaks so eloquently. Yet, with all the positive reasons for states to ratify the CTBT, there still remain some important international and domestic stumbling blocks. Because countries like the DPRK and Iran are on the list of annex II states, many in the US and around the world believe that the Treaty will never enter into force. These voices in the US use such countries as one excuse not to support US ratification of the Treaty. While US ratification is not sufficient for the Treaty to enter into force it is necessary, and US ratification is likely to be followed by the ratification of at least some other annex II states as well. In addition, the international community would certainly see US ratification of the CTBT as a positive step toward a world free of nuclear weapons and toward fulfilling the nuclear disarmament obligation under Article VI of the NPT.

Policy makers in Washington don’t seem to make the connection between keeping political commitments/upholding international treaty obligations and getting support from the global community for US nonproliferation objectives. This point is never lost at the UN on the vast majority of states (meaning all but the five permanent members of the Security Council). In speech after speech, in forum after forum, NNWS – along with India, Pakistan, and Israel – call upon NWS to fulfill their obligations from the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995 and from the 13 Practical Steps of the 2000 NPT Review Conference. President Obama recognizes the need for the international community to work together to manage our common security (see his speech to the GA here and to the Security Council here) and last week began reasserting US leadership at the UN in matters of nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation. To show the high-level of engagement that the US intends to have on the subject, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton led the US delegation to the Article XIV Conference (the first US delegation at an Article XIV Conference in ten years) and President Obama addressed the 64th General Assembly the day before the conference started and chaired the first ever Security Council Summit on nuclear disarmament and nonproliferation in a separate meeting on the conference’s first day. All this high-level attention from the US for the CTBT, nuclear disarmament, and nonproliferation was noted and welcomed by most of the states in attendance at the conference.

One thing that was not mentioned by any states in their official statements to the conference was the possibility of the provisional entry into force of the Treaty prior to obtaining all remaining annex II ratifications. Provisional entry into force of the CTBT could allow states parties to the Treaty to agree to on-site inspections when necessary, an important added layer to detect potential cheating. Provisional entry into force might also put pressure on those annex II states that have not yet ratified the Treaty to do so by being yet another indicator of the importance the vast majority of the international community places on the CTBT. Recognizing that international law helps solidify norms of state behavior and brings predictability and stability to international relations, many states at the conference spoke about the importance of codifying the voluntary nuclear testing moratoria the NWS have made into the CTBT, a legally binding treaty. Provisional entry into force of the Treaty before all annex II states have ratified could be an important step in the cementing of the norm against nuclear testing, thus providing another motivation for more annex II states to work toward ratification of the Treaty.

One other interesting note from the conference is that the actual measures to promote early entry into force of the CTBT – the main stated purpose of the conference – were not mentioned by many countries. Japan was one of only a few countries to discuss such measures in their speech, measures that included sending high-level envoys to annex II states to encourage their ratification of the Treaty at an early date. And while 103 states were represented at the conference, attendance during the bulk of state speeches was relatively low. This could be due to the fact that the General Assembly was simultaneously in session, and it should be noted that the large number of participants is indicative of the importance the international community places on the early entry into force of the CTBT.

The conference ended with the adoption of a final document but without much celebration. NNWS want serious progress to be made toward nuclear disarmament before NWS further restrict nuclear technology for peaceful purposes; the ratification of the CTBT by the two hold-out NWS is a promise that needs to be fulfilled for the vast majority of the world to recognize such serious progress. Despite the positive developments many states mentioned since the last Article XIV Conference in 2007, the CTBT is still not in force. US ratification of the CTBT might become the strongest signal of the revitalization of the nonproliferation regime, which will be tested for its durability at the upcoming NPT Review Conference in May 2010.

[i] The following is the list of annex II states that need to ratify the CTBT before it can enter into force: China; DPRK; Egypt; Indonesia; India; Islamic Republic of Iran; Israel; Pakistan; and the United States of America. Of these nine countries, three have not yet signed the Treaty (DPRK, India, and Pakistan).

Calculating Output of the New Iranian Uranium Enrichment Plant

On Friday, President Obama announced that the United States knows of a new, undeclared, and hidden underground gas-centrifuge uranium enrichment facility in Iran, near the city of Qom. Some news reports suggest that 3000 centrifuges will be housed there. How significant is this discovery? Well, just in time, our crack FAS researcher, Ivanka Barzashka, has posted on the FAS website a calculator to help you answer questions just like that.

Natural uranium is made up predominantly of two isotopes, that is, atoms of the same element with the same chemical properties but very slightly different masses and, therefore, dramatically different nuclear properties. Uranium-235 is the isotope that powers nuclear reactors and nuclear bombs. Natural uranium is less than one percent 235 but approximately 90 percent U-235 is needed for a bomb. Getting these higher concentrations is called “enrichment”. Today gas centrifuges are the method of choice for enriching uranium. Hence the great concern about the latest revelation. [We have a nice little video that explains how centrifuges work.]

The calculator can be used to investigate possible Iranian breakout scenarios. In summary, the user has to supply the calculator with the concentration of uranium-235 in the input, or feed. Natural uranium is 0.7%. If the Iranians used the output of the enrichment plant at Natanz as input to the Qom plant, then they could start with 3.5%. The user must also specify the U-235 concentration in the waste. If Iran wants to get as much U-235 as possible out of its uranium supply, then this number will be small, usually 0.2-0.25%. If Iran is in a rush, it could feed uranium through faster but throw away more U-235. For example, if it used 3.5% as input, it could have “waste” of 1%, which is a higher U-235 concentration than natural uranium.

The calculator then returns the value of amounts of uranium and the “separative work” needed. Separative work is a general measure of the capacity of an enrichment element (such as a centrifuge or centrifuge plant) to enrich a certain amount of material over a given time. A plant operator can utilize any given plant capacity to enrich a large amount of uranium a little bit (as you would for a nuclear reactor) or to enrich a small amount of uranium a lot (as you would for a nuclear bomb). It is as though we had a pump of a certain power available and we could choose to pump a large volume of water a small distance uphill or a small quantity of water much further uphill. Separative work is measured in Separative Work Units or SWUs, performed on a certain amount of material, almost always kilograms, so the unit is kg-SWU.

How many SWUs would the enrichment plant at Qom have and what could the Iranians do with it? First, keep in mind that all information we currently have on the new facility is pretty vague and based on a few news reports. Iran has not officially declared the capacity of the Qom plant or what kind of machines it will contain. But it was reported to have 3000 centrifuges. Very simple calculations based on IAEA reports suggest that the first generation Iranian centrifuges produce approximately 0.5 kg-SWU/year so the plant would produce 1500 kg-SWU/year. Perhaps the second generation centrifuges would go in the new facility. We really know very little at all about these except that they are presumably better than the first generation. You can speculate on the separative work of these centrifuges and multiply by 3000.

Using some of the examples above, we can use the calculator to estimate the bomb-making potential of the new Iranian facility. For example, if we start with natural uranium and calculate how many SWUs are needed to produce on bomb’s worth of 90% U-235 (estimated to be 27.8 kg for the simplest bomb, significantly less for a more sophisticated bomb), we find that 6400 SWUs are required or over four year’s worth of production at 1500 SWU a year. If we start with 3.5% U-235 from the Natanz plant and have wastes of 1%, then we need 1328 SWUs, so a 1500 SWU plant could produce a bomb’s worth in a little less than a year. Of course, if the individual centrifuges are higher performance, these times are reduced proportionately. We don’t know enough about the new facility to say much more than that.

The calculator was developed by an interdisciplinary team with background including scientists and programmers. The calculator is geared toward people without a technical background. The programming was done predominantly by FAS intern Augustine Sebastionelli, a computer systems major at Alvernia University. The technical aspect of the project was managed by Greg Watson, IT manager at FAS and, when Greg left FAS to return to get his master’s degree in political science, finished by our new IT Manager, Robert Lilly. FAS intern Amit Talapatra, a chemical engineering major from the University of Virginia, worked with the programmers to develop an algorithm to perform the dynamic calculation. Overall coordination and concept design was Ivanka Barzashka’s.

Next Obama Speech: The Pentagon

President Obama has once again pushed nuclear weapons, and his vision for a world free of nuclear weapons, to the center of the world’s stage with his speech yesterday before the United Nations’ General Assembly and his chairing of the United Nations’ Security Council meeting this morning. He reiterated his goal of ratifying the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), of negotiating a Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT) that would end production of bomb-grade nuclear material (something the Bush administration supported in theory but without any verification procedures), of negotiating a treaty with Russia that will “substantially reduce” strategic nuclear warheads, and of strengthening the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The President also said “We will complete a Nuclear Posture Review that opens the door to deeper cuts, and reduces the role of nuclear weapons.” This morning, as chair of the UN Security Council, the President got unanimous consent to Council resolution that endorsed all the points made before the General Assembly.

The President’s remarks are powerful and plain and were overwhelming well received by all of us who have long hoped that the world might someday be free of nuclear weapons. Still, I am worried that the message has been clearer at the UN, and in Prague, than it is here in Washington. If we look at the direction the bureaucracy and politics are taking here, there is reason to worry that the President’s vision will be dangerously diluted.

While the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is not paramount, it will be an important document. It will set out in broad terms what the U.S. nuclear doctrine is. I do not have any secret source deep within the Pentagon giving me access to special insider information but the Obama administration has made an admirable effort to keep interested parties posted on developments. And the news is not reassuring. Based on public briefings, the NPR document that seems to be shaping up is not a dramatic change from the status quo. Far from being revolutionary, it is a cautious, even modest, move in the right direction. That is not what we need.

To achieve a fundamental change, to put the world on a new course, the nuclear powers, led by the United States, have to change the fundamental role that nuclear weapons play. We have to change their mission and justification. Everything else is just working around the edges. And change in the fundamentals is what I don’t see coming out of the administration’s current effort.

The “requirements” for nuclear weapons, not just their numbers but how they are deployed, their power, accuracy, and reliability, all follow from the military missions that nuclear weapons are assigned. Nuclear weapons, and their missions, have been with us for so long people forget that these “requirements” don’t come from the laws of physics but from choices we make. If we got rid of all the first strike, preemptive missions and restricted nuclear weapons to the sole mission of retaliating for nuclear attack, with the aim of deterring that attack in the first place, then much of the danger of nuclear weapons could be removed. This would be essentially a no-nuclear-first-use doctrine. With such a doctrine, there would no need for weapons on alert, there would be no need for new weapons, not even a need to maintain extremely high reliability.

All the information coming out of the administration indicates that it is not considering giving up the first strike, preemptive missions and moving to a no-first-use doctrine. In a speech at the Carnegie Endowment early in the administration, Gary Samore, the staffer on the National Security Council who is keeping the White House on top of the NPR, said, in response to a question from my colleague Hans Kristensen, that a US no-first use doctrine is not plausible. Recently, Defense Secretary Gates said that we will need increased investments in the nuclear weapon enterprise and that he seems to think we will have nuclear weapons as far into the future as we can see; the “requirement” for billions of dollars in nuclear infrastructure rests on the unspoken assumption that nuclear weapons have to characteristics making them usable for a first strike. In a series of briefings on the NPR for a small group of interested parties, the Pentagon has suggested that the steady-as-she goes Congressional Strategic Posture Commission would be the foundation to build on.

No one expects a great deal from the current negotiations for the treaty that will take the place of START, the “START-follow-on.” Because START expires in December, it is important to get some lose ends tied up before then and to provide an interim treaty until the treaty after that is negotiated. It is that treaty, the follow-on to the follow-on, that is important. Nevertheless, the current negotiations seem modest even by those standards. The numbers being considered, 1675 deployed strategic weapons, is not meaningfully different from the 1700 limit in the wholly uninspiring Strategic Offensive Reduction Treaty (SORT). Moreover, the seven year time horizon discussed for the limits hints at a possible lack of urgency in taking a dramatic next step anytime soon.

All of this is important on the near and far term. The political stars are now aligned for a fundamental reassessment of the role of nuclear weapons. No one I know thinks we will ever have a better chance. And major decisions are coming up over the next decade in both the U.S., concerning new nuclear warheads, new missiles, and new submarines, that will affect our nuclear posture for the next fifty years.

The danger is that the President’s vision will not survive the wheels of the bureaucracy. All of the people who are working on the NPR are all extremely talented, knowledgeable, and thoughtful. But the evidence so far is that they are not inspired by a vision of a fundamental, revolutionary change. Nuclear weapons are serious business, a business we need to approach with sober caution, but the President needs to give his UN and Prague speeches at the Pentagon to inspire among the nuclear foot soldiers his passion and vision and not to settle for gradualism.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces 2009

|

| A high-security weapons storage area northwest of Karachi appears to be a potential nuclear weapons storage site. (click image to download larger version) |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Pakistan’s nuclear weapons stockpile now includes an estimated 70-90 nuclear warheads, according to the latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The estimate is an increase compared with the previous estimate of approximately 60 warheads due to Pakistan’s pending introduction of a new ballistic missile and cruise missiles.

The increase in the warhead estimate does not mean Pakistan is thought to be sprinting ahead of India, which is also increasing its stockpile.

Modernizations

The nuclear-capable Shaheen-II medium-range ballistic missile appears to be approaching operational deployment after long preparation. The Army test-launched two missiles within three days in April 2008, and the U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) reported in June 2009 that the weapon “probably will soon be deployed.”

Two types of nuclear-capable cruise missiles are also under development; the ground-launched Barbur and the air-launched Ra-ad. The development of cruise missiles with nuclear capability is interesting because it suggests that Pakistan’s nuclear weapons designers have been successful in building smaller and lighter plutonium warheads.

Warhead Security Concerns

An article published in the July issue of the CTC Sentinel news letter of the Combating Terrorism Center at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point gained widespread attention for describing terrorist attacks against three of Pakistan’s rumored nuclear weapons facilities: Wah Ordnance Facility, Kamra Air Base, and Sargodha Weapons Storage Facility. Although the incidents had been reported before, the article triggered the predictable rejection from a Pakistani military spokesman but with the additional claim that neither facility stored nuclear weapons. “These are nowhere close to any nuclear facility,” he said. Yet the official would most likely not disclose the location of the nuclear weapons, even if he knew where they were.

While the CTC Sentinel article says “most” of Pakistan’s nuclear sites might be close to or even within terrorist dominated areas, senior U.S. officials said the weapons were secure and mostly located south of Islamabad.

Regardless of the actual location of the weapons, there have, of course, been many more terrorists attacks against other facilities that have nothing to do with Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program, and so far no pattern has emerged in public of a concerted terrorist effort against nuclear sites – much less an attempt to steel nuclear weapons. A U.S. intelligence official commented to the New York Times that it was unclear whether the attackers knew what the facilities contained. “If they were after something specific, or were truly seeking entry, you’d think they might use a different tactic, one that’s been employed elsewhere – such as a bomb followed by a small-arms assault.”

Pakistani and U.S. statements about the Pakistani nuclear arsenal, and the basis for our estimate, are included in the Nuclear Notebook.

Publication: Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2009

Hiroshima: Making the Sixty-fourth Anniversary Special

by Ivan Oelrich

Today is the sixty-fourth anniversary of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, which was one of those rare events that divides human history into a before and an after. That day was the beginning of the nuclear age. There is nothing special about sixty-four, not like a fiftieth or a centenary. But, years from now, the sixty-fourth anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing may be seen as special: there is a chance that people looking back on today’s anniversary will see this as the beginning of the end of the nuclear age.

The Cold War came to a close two decades ago but only now are national leaders seriously considering a world free of nuclear weapons. Even those who see a global ban as a long-term goal can see that making serious progress in the direction of that goal will enhance the security of the nation and the world.

The number of nuclear weapons in the world has fallen dramatically from their frightening Cold War peaks. This decline is not due primarily to arms control treaties or any sudden rationality of national leaders. The numbers have gone down mostly because the missions for nuclear weapons —everything from nuclear torpedoes to nuclear land mines—have been taken over by militarily superior alternatives: advanced, guided, accurate conventional weapons. Nuclear weapons have gone away primarily because they are becoming technologically obsolete.

Obviously, the end of the Cold War was important too. The Cold War was a stand-off between two implacable ideologies, each of which felt it had a historic mandate to guide the future of the world. Nuclear weapons, weapons of global destruction, might have seemed appropriate to an ideological struggle of global dimension. But today, the stakes in play are smaller. If ever there were a global political justification for nuclear weapons, it no longer applies. Nuclear weapons are becoming politically obsolete.

Nuclear advocates, unwilling to admit that they are planning for the use of nuclear weapons, always talk in terms of deterrence, a term that has become so vague, misused, and overused that it barely means anything anymore. Those wanting a robust nuclear force, who want to think it is useful, even crucial, emphasize that deterring some action by threatening retaliation requires both the ability to retaliate and the willingness to do so. They make much of the need to constantly keep the perception of U.S. capability and willingness very high to deter any possible enemy.

There are three problems (at least three) with this use of the latent power of nuclear weapons. First, history shows it doesn’t work. Whether the U.S. in Vietnam or the Soviet Union in Afghanistan or in a score of other cases, having nuclear weapons does not automatically deter wars between nuclear and non-nuclear adversaries or win them, if they are not deterred. Second, nuclear weapons are so wildly destructive that the United States—and the other established nuclear powers—have destructive power at hand far in excess of any imaginable need. There is no reason to worry about the details of our nuclear capability. Finally, some nuclear advocates argue that we need to have smaller nuclear weapons to make our willingness to use them more plausible, so they will deter more effectively. This is the sort of more-is-less upside-down logic that only nuclear theorists could hope to get away with. But all the tweaking and fine-tuning of the nuclear arsenal will not change the plausibility of their use compared to one outstanding, and hopeful, fact: nuclear weapons have not been used in war for sixty-four years. If they were not used in Korea, or Vietnam, or Afghanistan, or the Falklands, or Iraq, their use is going to be even less plausible in similar conflicts in the future. The logic is inescapable but nuclear advocates will not face it: the only thing that can make the use of nuclear weapons significantly more plausible (and, thus, they argue, a better deterrent) is to occasionally use them. If we want to frighten non-nuclear nations with our nuclear weapons, we have to bomb one of them every decade or so. Mercifully, after sixty-four years, no nuclear power has done this. Moreover, every year that passes without nuclear use further erodes the plausibility of future nuclear use for anything other than national survival. The strategic leverage provided by nuclear weapons continues to erode. Nuclear weapons are becoming strategically obsolete.

Finally, the moral question of nuclear weapons is often overlooked. They have been with us so long, we have stopped asking the hard questions. Nuclear weapons analysts, both pro and con, avoid the squishy problems of moral debate if they want to be taken seriously. Yet, nuclear weapons force many of the moral concerns about war into stark relief. The customary laws of war are that violent action should be proportionate to the threat and should, to the extent possible, distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. Thus, what is moral depends in part on technology. If no alternatives exist, then an indiscriminant weapon might be justified. But today, alternatives do exist. Nuclear weapons are becoming morally obsolete.

Today’s call for a world free of nuclear weapons is not a call for sacrifice. It is not a call to accept greater risk for our country to improve the security of the rest of the world. It is not a call to take a moral stand, rejecting something that is wrong, but admittedly useful. The call for a nuclear free world is an acknowledgement that the curtain is starting to close on the nuclear age. Battleships, the very epitome of great nation power, ruled the oceans for about the same length of time the Nuclear Age has lasted. They arose, they had their day, and then a combination of changes in technology and global politics displaced those awesome, powerful giants and they were retired. Nuclear advocates are fighting an aggressive and skillful rear-guard action, fueled by nostalgia for the certainties of the past and a lack of imagination about the future just as romantics wanted to keep battleships alive long after aircraft carriers, submarines, radar, and cruise missiles had made them obsolete. Nuclear weapons are in the middle of this process of obsolescence. It is better to speed the process along and reduce the risk nuclear weapons pose to world civilization, to explicitly reject them and plan for their demise than to continue to bumble through the danger we daily face but have become inured to. For the first time since Hiroshima, the world seems ready to listen. It may be, a generation from now, that sixty-four will be seen as a special anniversary.

Thought for the day, courtesy of Fogbank

by Alicia Godsberg

Yesterday’s Washington Post had another article[1] in the ongoing saga of W76 warhead refurbishment Life Extension Program (LEP) and Fogbank – a material that, according to open sources, is an intermediary material between the primary and secondary of a nuclear weapon that is “crucial” to the weapon reaching its designed yield.[2] The problem for the W76 LEP: the original Fogbank manufacturing facility was closed years ago, at least partly because the material is extremely hazardous. In addition, due to a lack of record keeping from the original manufacturing process (and the retirement of many knowledgeable scientists involved in that process), the labs found themselves not knowing how to re-manufacture Fogbank or a suitable replacement material for the W76 in a timely manner. The labs tried a three-prong approach to fixing this problem: building a new Fogbank production facility; manufacturing limited quantities at an interim location; and producing a suitable alternative made from less hazardous materials that would not need to undergo nuclear testing.[3] What we have now is a new $50 million dollar facility at Y-12 to produce Fogbank in either some new form or its older, more hazardous form.[4]

That is the brief background – here is the thought of the day, courtesy of many conversations with Ivan Oelrich: there is no longer any justification for retaining complex, extremely high-yield two-stage thermonuclear nuclear weapons in a post-Cold War world. Our nuclear deterrent would be sufficient with more simple-to-make HEU weapons, even gun-type weapons, the design of which was so scientifically fool-proof that it didn’t need testing before it was dropped on Hiroshima 64 years ago almost to the day. (more…)

French Aircraft Carrier Sails Without Nukes

|

| The French nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle with air wing on deck. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

France no longer deploys nuclear weapons on its aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle under normal circumstances but stores the weapons on land, according to French officials.

President Nicolas Sarkozy declared in March 2008 that France “could and should be more transparent with respect to its nuclear arsenal than anyone ever has been.” But while the other nuclear powers declared long ago that their naval weapons were offloaded or scrapped after the Cold War ended, a similar announcement has – to my knowledge – been lacking from France.

The French acknowledgment marks the end of peacetime deployment of short-range nuclear weapons at sea.

It is not clear when the French offload occurred; it may have been instigated years ago. But it completes a worldwide withdrawal of short-range nuclear weapons from the world’s oceans that 20 years ago included more than 6,500 British, French, Russian, and U.S. cruise missiles, anti-submarine rockets, anti-aircraft missiles, depth bombs, torpedoes and bombs.

Nuclear Charles de Gaulle

The nuclear-powered aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle carries a squadron of Super Étendard bombers equipped with the ASMP nuclear cruise missile. From 2010 these aircraft will be replaced with the Rafale MK3 (navy version) equipped with a new nuclear cruise missile known as the ASMP-A. The weapon will enter service with air force’s Mirage 2000Ns this fall and next year with the Rafale F3.

|

ASMP on Super Étendard |

|

| A Super Étendard prepares to take off from an aircraft carrier with an ASMP nuclear cruise missile shape under its right wing. |

France previously operated two aircraft carriers, the Clemenceau and Foch, with nuclear capability. Initially armed with nuclear bombs, the ships were upgraded to the ASMP in the late 1980s, but decommissioned in 1997 and 2000, respectively. Plans to replace them with two nuclear-powered carriers did not materialize; only the Charles de Gaulle has been built.

|

ASMP-A on Rafale F3 |

|

| A Rafale F3 aircraft with an ASMP-A nuclear cruise missile shape installed on the center pylon. |

With a range of only 300 km (500 km for the ASMP-A), the cruise missile strictly speaking falls into the category of U.S. and Russian non-strategic weapons, but France calls its cruise missile strategic or pre-strategic. Technically, the range of the aircraft delivering the cruise missile extends the range to 2,000-2,500 km, similar to the U.S. nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile and the Russian SS-N-21. But that assumes the aircraft will be able to penetrate the air defenses of the target country. Regardless, potential adversaries probably care less about the category terminology than the fact that the weapon is nuclear.

During normal circumstances the cruise missiles are stored on land, perhaps in a weapons storage area close to the carrier’s homeport in Toulon. The weapons storage spaces onboard the Charles de Gaulle are maintained and the crew periodically trained and certified to store and handle the missiles so they can quickly be brought onboard if a decision is made to deploy the them.

As for the Charles de Gaulle’s nuclear strike mission, it can hardly be said to be essential; During the extended time periods the carrier is in overhaul (18 months), France does not have a sea-based nuclear cruise missile capability.

Additional Information: French Nuclear Forces 2008

State Department Confirms FAS Warhead Estimate

|

| Retirement of the W62 warhead will be completed in 2009. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. State Department has confirmed the estimate made by FAS on this blog in February that the United States had already reached the limit of 2,200 operationally deployed strategic nuclear warheads set by the 2002 Moscow Treaty. The confirmation occurred earlier today in a fact sheet published on the State Department’s web site: “As of May 2009, the United States had cut its number of operationally deployed strategic nuclear warheads to 2,126.”

This is a reduction of 77 warheads from the 2,203 operationally deployed strategic nuclear warheads deployed on February 5, 2009, and probably reflects the ongoing retirement of the W62 warhead from the Minuteman III ICBM force, scheduled for completion later this year.

The total U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile includes approximately 5,200 warheads.

The Big Picture – what is really at stake with the START follow-on Treaty

by Alicia Godsberg

There is cause for cautious optimism after Presidents Obama and Medvedev signed their START follow-on Joint Understanding in Moscow last Monday – the goal of completing a legally binding bilateral nuclear disarmament agreement with verification measures is preferable to letting START expire without an agreement or without one that keeps some sort of verification protocol. The Joint Understanding leaves some familiar questions open, such as the lack of definition of a “strategic offensive weapon” and what to do about the thousands of nuclear warheads in reserve or awaiting dismantlement. But so far few analysts on either side of the nuclear debate have been talking about the big picture, what for the vast majority of the world (and therefore our own national security) is really at stake here – the viability of the nonproliferation regime itself.

Why will the follow-on treaty to START have such a great impact on the entire nonproliferation regime? Simply, the rest of the world is looking for the possessors of 95% of the global nuclear weapon stockpiles to show greater effort in working toward their nuclear disarmament obligation under the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The NPT is both a nonproliferation and disarmament treaty, and at the NPT Review Conferences (RC’s) and Preparatory Committees (PrepCom’s) the Non-Nuclear Weapons States Parties (NNWS) continue to voice their growing concern and anger over what they perceive to be lack of real progress on nuclear disarmament. At the PrepCom this past May those voices – including many of our closest allies – spoke loudly, stating that continued failure by the NWS to work in good faith toward their nuclear disarmament obligation could eventually break up the nonproliferation regime, spelling the end of the other part of the Treaty’s bargain: the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

Just to put things in perspective, NNWS are every country in the world except the five NWS (US, Russia, UK, France, and China) and the three countries that have never signed the NPT (Israel, India, and Pakistan – with a question now about the obligations of North Korea and without including Taiwan, which is not recognized by the United Nations). While the NPT has an elaborate mechanism to verify the compliance of NNWS with their nonproliferation obligations under the Treaty (i.e. the IAEA and its Safeguards Agreements), there are no institutionalized means to monitor or enforce compliance with the disarmament obligation of NWS under Article VI of the Treaty. And while some NWS are now proposing further restrictions on NNWS nuclear energy programs through preventing the spread of sensitive fuel-cycle technology, NNWS are increasingly voicing their frustration over nuclear trade restrictions while greater progress on nuclear disarmament remains in some distant future. Further fueling this distrust of the NWS and of new technology transfer restrictions was the Bush administration’s ill-advised US-India nuclear cooperation deal, seen by many NNWS as “rewarding” India with an exception to nuclear trade laws and export controls while India continues to operate its nuclear programs largely outside the NPT’s nonproliferation regime and its oversight and restrictions.

This blog is not meant to weigh in on the controversy surrounding the inalienable right of NNWS to nuclear technology under Article IV of the NPT, but rather to state the fact that a series of what are perceived as broken promises by NWS to NNWS has led the regime to approach what many have seen as a breaking point. Some of those promises include the ratification of the CTBT, strengthening of the ABM Treaty, and the establishment of a Nuclear Weapon Free Zone in the Middle East. These promises have special significance, as they were part of political commitments made to get the indefinite extension of the NPT in 1995, thereby removing any small pressure NNWS might have been able to place on NWS to meet their disarmament obligation by threatening not to renew the Treaty at future RC’s.

The US has a special role to play in this drama for two reasons. First, the US is the second largest possessor of nuclear weapons in the world and as such needs to be at the forefront of nuclear disarmament for that goal to be taken seriously and eventually come to fruition. Second, President Obama has publicly reversed some positions of President George W. Bush on nuclear disarmament and the world is waiting to see if his vision will be translated into action by the US. For example, at the 2005 NPT RC the Bush administration stated it would not consider as binding any of the commitments made by prior US administrations at previous RC’s, such as the commitment to the “unequivocal undertaking” to eliminate nuclear weapons and the commitment to work toward ratifying the CTBT. Contrast that with Obama’s policy speeches, especially the one in Prague on April 5, 20009 in which he placed a high priority on US verification of the CTBT and on his vision of a world free of nuclear weapons, and you can begin to understand the feeling of hope surrounded by a continued atmosphere of mistrust that pervaded the United Nations in May.

A recent New York Times op-ed[i] pointed out that there is no guarantee the US Senate is going to go along with President Obama’s nuclear policy vision, and he may in fact encounter difficulty ratifying the CTBT and gaining support for the reductions outlined in last week’s Joint Statement. In a June 30 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal,[ii] Senator Kyl and Richard Perle voiced this side of the debate, stating:

There is a fashionable notion that if only we and the Russians reduced our nuclear forces, other nations would reduce their existing arsenals or abandon plans to acquire nuclear weapons altogether… this is dangerous, wishful thinking. If we were to approach zero nuclear weapons today, others would almost certainly try even harder to catapult to superpower status by acquiring a bomb or two. A robust American nuclear force is an essential discouragement to nuclear proliferators; a weak or uncertain force just the opposite.

This fear mongering, unsupported by the facts, is the type of rhetoric that will confuse the debate once any START or CTBT-related issues hit the Senate floor. In a world where reductions would still leave actively deployed nuclear warheads in the thousands – with thousands more on reserve – “superpower status” will not be achieved by acquiring “a bomb or two.” Think about North Korea – are they a “superpower” now that they have exploded two nuclear devices and we know they are continuing to work on their nuclear weapon program? Hardly. Instead, they are international outcasts, condemned even by China for their latest atomic experiment, and have become weaker still in their attempt to achieve international status. And if the US, the country with the most powerful and advanced conventional forces, needs a “robust” nuclear force to protect its national security and fulfill security commitments, then it seems that any country with a weaker conventional force (which is everyone else) should seek nuclear weapons. So, I would argue exactly the opposite Senator Kyl and Mr. Perle, and say that a diminishing role for nuclear weapons in US security actually lessens the case for other nations to develop their own nuclear weapons, which are more costly both economically and politically than conventional forces.

Whether the US can restore the faith of the rest of the world in our leadership on nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament by meeting previous political commitments and working toward fulfilling Treaty obligations remains to be seen. Rose Gottemoeller’s remarks to the 2009 NPT PrepCom at the UN in May were well received by the global community, but NNWS also made clear that words need to be followed by concrete actions. The US needs the cooperation of the global community to continue the success of the nonproliferation regime, which has been largely successful over the past 39 years minus the few notable failures. To do this, the US must understand that the follow-on treaty to START will directly impact the perception the rest of our global community has about the seriousness of our commitment to the NPT. That is because the NPT is both a disarmament and nonproliferation treaty; if the US recognizes and acts on this truth, it will be able to achieve the urgent goal of regaining its leadership position on the nonproliferation of nuclear weapons.

[i] Taubman, Philip. “Obama’s Big Missile Test.” Editorial. New York Times 8 July 2009.

[ii] Jon Kyl and Richard Perle. “Our Decaying Nuclear Deterrent.” Editorial. Wall Street Journal 30 June 2009.

Not Getting It Right: More Bad Reasons to Have Nuclear Weapons

A recently released report, U.S. Nuclear Deterrence in the 21st Century: Getting It Right, by the ad hoc New Deterrent Working Group with a forward by James Woolsey, is an interesting document. I believe this report is significant because it might typify the arguments that will be used against arms control treaties in the upcoming Senate debates.

Much of what is written in support of existing nuclear policies is such a logical muddle that one hardly knows where to start in a critique. As a statement of the pro-nuclear position, this paper is clearer than most so worth addressing. It makes the errors that others do when arguing for nuclear weapons, specifically, making statements about the “requirements” for nuclear weapons that imply missions left over from the Cold War, but the report is particularly blunt in its demands and might serve as a good example of the pro-nuclear arguments. The report is almost seventy pages long, so I can’t touch on every point in a blog and I think I will leave the arguments about nuclear testing for a separate blog to follow.

The report starts out with one fundamental mistake contained in almost every discussion on nuclear weapons: It conflates nuclear weapons with deterrence. Nuclear weapons are so thoroughly equated with deterrence—they are often simply called “the deterrent” —that we seldom stop to think about the details of how this deterrent is supposed to work. What is being deterred, whom, how, for what purpose? If we do not know what nuclear weapons are for, what their missions are, what their targets are, then it is impossible to pin down what their performance characteristics ought to be.

Uncertainty, Reliability, and Safety

The report argues that we need nuclear weapons in part because the world and the future are very uncertain. The report admits no one knows the answers to any of the questions above so the United States simply has to make certain that it has sufficient numbers of nuclear weapons with a variety of capabilities and hope for the best. The problem with this approach is that planning for uncertainty is never finished; we never reach an endpoint. For example, the heading on p. 25, “U.S. nuclear weapons are deteriorating and do not include all possible safety and reliability options” is not only true but always will be true. The “deteriorating” fear has been refuted: parts in weapons age, and these parts are being replaced when needed so the weapons remain within design specifications. This is not cheap or simple but neither is it impossible and can continue for decades. But admittedly, nuclear weapons do not have “all possible safety and reliability options.” There are, no doubt, “options” no one has even thought of yet. So how much reliability and safety is enough? When can we stop?

The answer depends on the missions for nuclear weapons. If nuclear weapons had only the mission of retaliating against nuclear attack, to inflict sufficient pain to make such an attack seem pointless in the first place, then one could plausibly argue that 90% reliability is adequate. If the United States needs to destroy, say, ten targets to inflict sufficient pain to deter, then which ten is not absolutely critical and it could fire at eleven targets and accept that one might escape. Even if the United States wanted to use nuclear weapons to attack and destroy stocks of chemical and biological weapons, it could fire a nuclear weapon at the target and, if one in ten does not go off, it could fire off another bomb an hour later. It is not as though we will not know whether a nuclear bomb actually went off, that will be pretty obvious. If, on the other hand, the United States wants to conduct a surprise, disarming first strike against Russian central nuclear forces, destroying its missiles on the ground, then there is a huge difference whether the attack is 90%, 95%, or 99.9% successful. If the Russians have a thousand warheads, that is the difference between 100, 50, or 1 surviving, obviously significant. So, to say that nuclear warheads need a certain reliability, specifically a high reliability, is to imply certain missions. But these are missions that nuclear advocates rarely want to acknowledge explicitly because they know what a hard sell it will be while “reliability” seems like an obvious, inarguable good quality to have.

What about safety? Certainly we should have nuclear weapons that are as safe as possible and no effort should be spared to make them safer, right? In fact, the Working Group does not agree. The safest nuclear weapons are the ones that do not exist, so ultimate safety calls for nuclear abolition, an option explicitly rejected by the Working Group. If we are going to have actual nuclear weapons, they could be made safer by storing them disassembled. If we need assembled warheads, they could be made safer by removing them from their missiles. Warheads on missiles could be made safer by taking the missiles off alert. All of these options are explicitly rejected by the Working Group. What the report really means when it says we should have “all possible” safety options is that we should fund the National Labs at high levels forever but not change deployments one iota in the interest of safety, hardly my definition of “all possible.”

How Much Is Enough?

The rest of the report makes claims that are unproven and often unprovable and sets requirements for nuclear weapons that sound as though the Cold War never ended. I understand that even in a report of seventy pages not every statement can be fully analyzed and supported but, even so, there are a score of amazing claims for nuclear weapons that are supported mostly by lots of quotes.

The report makes the error of discussing the numbers of nuclear weapons in terms of reductions, specifically since the Cold War (p. 11). All references to reductions imply the Cold War is a benchmark by which current arsenals are measured. But the world has been turned on its head since then and comparison to Cold War numbers is neither relevant nor enlightening. (The Navy also has fewer battleships than it did in World War II. The point is?)

The report states (p. 11), “In a number of cases, a robust American nuclear arsenal has proven to be effective not only in deterring attacks on the United States and its allies from adversaries using weapons of mass destruction.” This may be true but it is very hard to know. Failures of deterrence are obvious but, if some action does not happen, then why did it not happen? Was the action every really considered? Was it considered but rejected for some other reason? Or was it deterred? Arguments about the effectiveness of deterrence are inevitably going to be speculative and based on absence of evidence. As Donald Rumsfeld pointed out while Secretary of Defense, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. There is no doubt that deterrence is real in many cases, it really works in many cases, but it is very difficult to be certain when and where. We should all (me included) be very cautious when making arguments about deterrence. I believe that general discussions of deterrence almost always go off the rails. When we talk about deterrence, we should at least try to use concrete examples for discussion. In the case of nuclear weapons, going to some example, any example, almost always demonstrates that the arguments in favor of nuclear weapons are simply incredible.

The report states (p. 12), “In short, the available evidence suggests that an American nuclear deterrent that is either qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient will have the effect of encouraging the very proliferation of nuclear forces we seek to prevent.” This might be tautologically true if the definition of “insufficient” is chosen to make it true. But there is no “available evidence” for the simple reason that the “American nuclear deterrent” (note again how nuclear weapons are thoughtlessly referred to as the “deterrent”) has never been anywhere near “insufficient” since 1945. So exactly when was this experiment conducted? Later (p. 51) the reports states, “To the contrary, history has clearly shown that unilateral US reductions, far from causing a similar response, actually stimulate nuclear buildups by adversaries.” What can they be talking about? Russia, Britain, France, and China went nuclear while the U.S. arsenal was expanding or just plain huge. The nuclear arsenal of the United States declined from its peak because of the retirement of thousands of battlefield nuclear weapons made obsolete by modern precision conventional alternatives. Did South Africa, India, Israel, Pakistan, or North Korea really go nuclear because of “unilateral US reductions”? These confident statements are based on a “history” of some parallel universe.

The report asserts that China has “its own extensive military modernization program.” China, with a growing economy is naturally increasing its overall budget but its nuclear ambitions continue to appear quite restrained. Hans Kristensen has written extensively on this.

Hydronuclear Alert

The report asserts that Russia is conducting hydronuclear tests, that is, nuclear weapon tests with very small nuclear yields, tests that the United States would consider in violation of the Comprehensive Test Ban. This is a common claim from pro-nuclear people, based, apparently on highly classified reports that are repeated here in this unclassified document. Some of the authors of the report have or had security clearances so any claim to the contrary is met with “if only you knew what I know.” All I can say is that I have asked people who do know what the authors know and apparently the evidence is unclear, specifically, the United States does not have good enough detection capability to prove that the Russians are not conducting such tests. If the Russians are conducting such tests, and the pro-nuclear lobby has already let the cat out of the bag, the intelligence community should present testimony in Congress confirming the tests. As far as I know, they have not done so. Even so, note that the fuss is about a treaty that the United States has not ratified. Upon ratification, the United States and Russia (and perhaps China) could agree in parallel to place instruments at each other’s tests sites and resolve this ambiguity.

Nuclear Weapons Ready to Fly.

The report advocates, even assumes, an aggressive nuclear stance, with weapons constantly ready to go. For example, (p. 15): “Finally, the continued credibility and effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear deterrent precludes de-mating of warheads on operational systems or otherwise reducing the alert rates or alert status of U.S. forces.” Again, we should apply this general statement to a few concrete examples. First, by arguing against reducing alert rates they are endorsing current alert rates. While the report objects to the term “hair trigger alert,’ U.S. nuclear weapons are, in fact, ready to launch on a few minutes’ notice. At any given moment, many are deployed on submarines off the coast of China and Russia, atop missiles just a few minutes flight time from their targets. Do they really mean that an enemy will not be deterred if these conditions are relaxed? We have to imagine a scenario in which the leader of China, Russia, or maybe North Korea want to use nuclear weapons against the United States but, knowing that they will be hit back 40 minutes later are deterred. Then their head of military intelligence comes in and reports that the American nuclear bombs won’t arrive until eight hours later, or perhaps the next day, or whatever, and as a result the enemy leader says, “Well, in that case, let’s attack.” Perhaps someone else can think of a case in which this is plausible but I cannot.

Later (p. 59), the report does try to give some further justification for high alerts: “They [nuclear weapons] must be known to be ready and useable to have deterrent effect. No START follow-on agreement can be deemed in the national security interest if it would require downgrading of that condition and, thereby, potentially leave the United States vulnerable to coercion based on the threat of second or third strikes before we could respond to an attack.” This actually makes some sense but we have to think about what it really means. It means keeping a constant counterforce attack capability. The statement above says that, if Russia (in the context of START, we are talking about Russia) attacks the United States with nuclear weapons, the next act of the United States should be to attack all remaining Russian nuclear weapons so they can’t do any more damage. That sounds plausible but let’s think this though. The Russians can safely assume the Americans will be more than a little upset after a nuclear bomb has gone off. The Russians will know that their vulnerable weapons could be attacked so they would either disperse their weapons to make them invulnerable or they would use them. It might be that keeping a counterforce capability results in the Russians throwing everything they can throw at the United States in the first wave, actually increasing the damage to the United States in a contest that would otherwise have smaller stakes. I have written elsewhere how high U.S. alert rates make reductions in nuclear forces more difficult for Russia. Moreover, the report completely neglects the costs of high alert rates, not just the financial costs but the risks of accidental nuclear launch, either by the United States or Russia, and the danger of Russian mitigating tactics, and the loss of escalation control. The authors fail to imagine that the United States and Russia might negotiate mutual force postures that include weapons off alert that are mutually invulnerable, creating a much more stable nuclear environment. The authors seem to believe that a Cold War Lite is the only way the world can be. They cannot see over the hill into the next valley.

The report makes a series of other remarkable and unsupportable claims, but I want to address those in a separate blog about nuclear testing.

START Follow-On: What SORT of Agreement?

|

| Presidents Obama and Medvedev sign a joint understanding on a START follow-on treaty. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

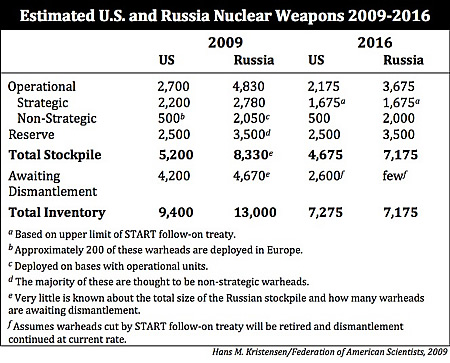

The Joint Understanding for the START Follow-on Treaty signed by President Obama and Medvedev on July 6, 2009, commits the United States and Russia to “reduce their strategic warheads to a range of 1500-1675, and their strategic delivery vehicles to a range of 500-1100.”

Negotiators will still have to hammer out the details and draft a new treaty that the presidents can sign, hopefully by the end of the year, to be implemented in seven years.

The Summit was a good effort to revive U.S.-Russian relations, but seven years is a very long timeline for a START follow-on that doesn’t force either side to change very much. Does it rule out deeper cuts for the rest of the Obama administration?

Perceived and Actual Cuts

Although the actual treaty has yet to be written up, the Joint Understanding indicates that it will be a hybrid between the 1991 START treaty and the 2002 SORT agreement: limits on strategic delivery vehicle and deployed strategic warheads. It adopts the range-limit of the SORT agreement and continues some form of verification regime.

The lower limits of 1,500 strategic warheads and 500 delivery vehicles are meaningless because neither country is prohibited from going lower if it chooses to do so. The only real limit is the upper limit of 1,675 deployed strategic warheads and 1,100 strategic delivery vehicles.

Unfortunately, and this often happens when arms control agreements are covered, the news media has widely misreported what has been agreed to. Here are some examples:

* Washington Post: The agreement would “cut the American and Russian nuclear arsenals by as much as a third” by reducing the “the number of deployed nuclear warheads in each country to between 1,500 and 1,675….”

* Associated Press: The agreement would “slash nuclear stockpiles by about a third….”

* Washington Times: The agreement “would reduce nuclear warheads to between 1,500 and 1,675….”

In fact, the agreement only reduces deployed strategic warheads. It does not affect warheads held in reserve, non-strategic warheads, the size of the total stockpile, nor does it require dismantlement of any nuclear warheads.

The number of warheads in each country is secret and projections fraught with considerable uncertainty, but here is how the proposed START follow-on treaty might affect the nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States:

Compared with the forces deployed as of 2009, the effect of the START follow-on appears to be a reduction of Russian deployed strategic warheads by approximately 40 percent, and a U.S. reduction of roughly 24 percent. The estimated effect on the total stockpile of either country is more modest: 14 percent fewer warheads for Russia and 10 percent for the United States. But that assumes the warheads cut by the START follow-on treaty would be retired rather than placed in the reserve, something the agreement does not require. The treaty itself requires no change in the size of the total stockpiles.

The reduction to 500-1,100 strategic delivery vehicles represents a significant reduction from the START ceiling of 1,600, at least on paper. In reality, however, the upper limit exceeds what either country currently deploys, and the lower level exceeds what Russia is expected to deploy by 2017 anyway. Therefore, a 500-1,100 limit doesn’t force either country to make changes to its nuclear structure but essentially follows current deployment plans.

The United States currently deploys approximately 798 strategic delivery vehicles; Russia approximately 620. But many of the Russian systems are being retired and not being replaced on a one-for-one basis so the entire force could shrink to less than 400 strategic delivery vehicles by 2016. To put in perspective; that would be less than the United States deploys in its ICBM force alone.

It is clear that claims that the Kremlin got everything while Washington gave away at the store are not accurate. Because Russia deploys more strategic warheads than the United States it also has to reduce more under the new treaty. And even after implementation, the United States will still have more – and better – strategic delivery vehicles than Russia.

So What?

Just like President Bush set a force level of 1,700-2,200 “operationally deployed strategic warheads” before the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review was completed, President Obama has now set what probably will be the overall force level of the ongoing Nuclear Posture Review. Not only will that review cut the number of warheads, it will probably also cut the number of delivery vehicles, perhaps a couple of the SSBNs and some of the ICBMs.

Yet some planners will probably argue against such cuts because Russia is compensating for its lower number of strategic delivery vehicles by deploying more warheads on each missile than the United States. In the minds of some, details like that still matter.

One architect of the Bush administration’s nuclear policy recently argued that the START follow-on agreement is a sellout by the Obama administration because it will “control or eliminate many elements of U.S. military power in exchange for strategic force reductions [Russia] will have to make anyway,” make the United States more vulnerable to a nuclear first strike, and make it harder to direct the nuclear force against other potential adversaries. Another warned that it would right-out “compromise” the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

Such arguments are both well known from the Cold War and out of sync with the 21st Century because they represent a cocooned form of strategic thinking that is preoccupied with Cold War scenarios. It is precisely because Russia is reducing that the United States should also trim its force; anything else will cater to those elements in Russia who want to stop and reverse the reduction. How could such a future possibly be in the interest of the United States or its allies (and, for that matter, Russia)?

And just why a U.S. arsenal of several thousand nuclear weapons would not be able to deter any other realistic adversary – to the extent anything can – is beyond me.

Internally the START follow-on will no doubt help the United States and Russia at the 2010 Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Yet even when the new treaty has been implemented in seven years, the two countries will still possess more than 90 percent of the world’s nuclear weapons, each with over 20 times more weapons than the next-largest nuclear power: China.

What’s Next?

Where does the new agreement fit in? It is explicitly described as a follow-on agreement to START, and U.S. and Russian officials have spoken of a step-by-step process that would initially extend START, produce a follow-on treaty, and also address non-strategic weapons and reserve warheads.

Yet the long timeline of the START follow-on agreement – seven years from the date of signing, five years after the SORT deadline – raises the question of whether this is as deep as they want to go in deployed strategic weapons. Since the limit of 1,100 delivery vehicles liberates either country from having to change their force structure, the agreement could be implemented very quickly – probably in a few months. So why set a timeline of seven years? I hope it does not rule out deeper cuts during even a second Obama administration.

Is the START follow-on the umbrella structure and the other steps – reserve weapons, counting rules, and non-strategic weapons – intended to follow underneath while it is being implemented?

Time will tell, but a couple of clarifying statements from the administration would be helpful.

Background Information: Full Text of Joint Understanding | U.S. Nuclear Forces 2009 | Russian Nuclear Forces 2009