Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons Discussed in Warsaw

The conference was held in this elaborate room at the Intercontinental Warsaw hotel.

By Hans M. Kristensen

In early February, I participated in a conference in Warsaw on non-strategic nuclear weapons. The conference was organized by the Polish Institute of International Affairs, the Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, with the participation of the U.S. State Department.

The conference had very high-level government representation from the United States and NATO, and included non-governmental experts from the academic and think-tank communities in Russia and NATO countries. The Russian government unfortunately did not send participants.

The United States and NATO want to broaden the arms control agenda to non-strategic nuclear weapons, which have so far largely eluded limitations and verification. The objective of the conference was to try to identify options for how NATO and Russia might begin to discuss confidence-building measures and eventually limitations on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The conference commissioned eight working papers to form the basis for the discussions. My paper, which focused on identifying common definitions for categories of non-strategic nuclear weapons, recommended starting with air-delivered weapons as the only compatible category for negotiations on U.S-Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Background: Working papers and lists of participants are available on the PISM web site. For background on non-strategic nuclear weapons, see this FAS report.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Options for Reducing Nuclear Weapons Requirements

By Hans M. Kristensen

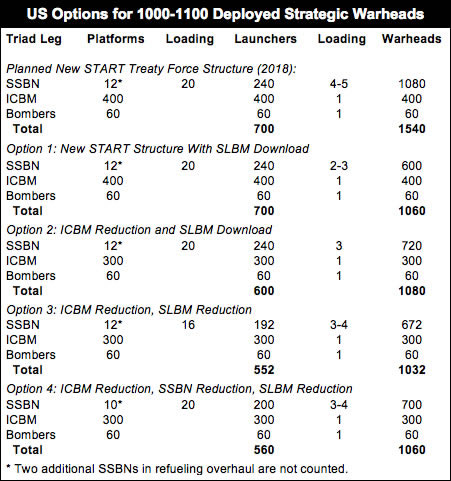

With the ink barely dry on the New START Treaty, Jeff Smith at the Center for Public Integrity reports that the Obama administration has determined that the United States can meet its national and international security requirements with 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic nuclear warheads – 450-550 warheads less than planned under the New START Treaty.

The administration is exploring how to get Russian agreement to the reductions without a new treaty, according to the New York Times. That would avoid a new agreement being held hostage to conservative Cold Warriors in Congress who fought ratification of the New START Treaty. Their efforts will be complicated by the fact that the U.S. military (and others) backs the reduced force level.

This is great news that reaffirms the administration’s commitment to continuing reducing excessive nuclear force levels. The fact that the new force level ended up closer to 1,000 than 1,200 warheads continues the 30 percent step-by-step reduction trend of the New START Treaty. The new initiative apparently also seeks reductions of non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear weapons, although it is unclear whether this is part of the first phase of the effort.

The lower force level has the potential to save billions of dollars, but how much depends on how the administration decides to implement it.

Reduction Options

The United States could meet the lower force level simply by reducing the warhead loading on ballistic missile submarines but without changing the force structure planned under the New START Treaty (see Table 1, Option 1). This would be a mistake because it would make it hard to convince Russia to join and it would save little money.

A more likely option would be to combine an ICBM reduction with a smaller SLBM download (Table 1, Option 2). That would reduce the ICBM force to 300 missiles and the overall force structure to 600 deployed launchers, or 100 less than under New START. Reducing the ICBM force to 300 from 400 planned under new START – a reduction of 150 from today’s 450 Minuteman III missiles – could be achieved by closing one of the three ICBM bases. A more likely option would be to spread job losses across the force by reducing the number of missile squadrons at each wing from three to two.

Another option would be to cut the ICBM force to 300 and reduce the missile loading on each SSBN from 20 planned under New START to 16, the same number planned for the next-generation SSBN (Table 1, Option 3). This option would reduce the force structure by nearly 150 deployed launchers below New START limit, thereby limiting the large advantage compared with Russia’s smaller force structure.

Yet another option could be to retire two SSBNs and reduce the ICBM force to 300. This option (Table 1, Option 4) would cancel the expensive refueling overhauls of the USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) and USS Louisiana (SSBN-743), retire the two submarines, and reduce the SSBN force to 12. Only 10 of those would be available for deployment.

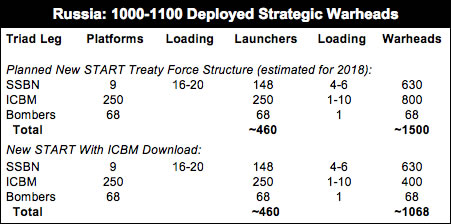

How would a reduction to 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads affect Russia’s posture? There are many uncertainties about how Russia’s missile forces will evolve over the next decade, but by the early 2020s the number of deployed missiles might decline to some 350 (down from around 450 today), or significantly less than the 700 permitted by the New START Treaty. So a new treaty would likely have little effect on reducing Russian deployed launchers.

The most important effect of a new limit of 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads would be to reduce the warhead loading on Russia’s ICBMs. This is particularly important because Russia compensates for its smaller missile inventory by deployed more warheads on each missile. Again, the numbers are uncertain, but the lower warhead limit could potentially reduce Russian ICBM warheads by as much as 50 percent from roughly 800 estimated under the New START Treaty to approximately 400 warheads under the new reduced limit (see Table 2).

The only reason Russia would agree to this, it seems, is if the United States significantly reduced its deployed missiles and also reduced the number of warheads kept in reserve as a potential upload capability. The combination of a larger U.S. missile force with a large upload capacity is a significant breakout capability that undermines the changes of reaching a new agreement.

It is double important that a new agreement limits the upload capability because it could otherwise result in Russia also creating a “hedge” of non-deployed strategic warheads. Closing this “reconstitution” loophole in the arms reduction process is important for making nuclear reductions irreversible.

Effect on Role of Nuclear Weapons

How the reduced force level will reduce the role of nuclear weapons is yet unclear. President Obama stated in his Prague speech that he wanted to “put an end to Cold War thinking” by reducing “the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.”

We have yet to hear how the new guidance puts and end to Cold War thinking in the way the military is required to plan for the potential use of nuclear weapons. Smith’s article states that the lower deployed warhead level would be achieved by U.S. Strategic Command “targeting fewer, but more important, military or political sites in Russia, China, and several other countries.”

If so, that would appear to refer to what is known as “nodal targeting,” in which planners focus targeting with nuclear forces on the most important facilities rather than holding at risk all facilities within a target category. Nodal targeting has been used for the past two decades to reduce warhead requirements and focus the strategic nuclear war plan on effects rather than on creating rubble.

The current nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010, Strategic Deterrence and Global Strike [/blog/ssp/2010/02/warplan.php]) is designed to hold at risk nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction (WMD) forces, command and control, military and political leadership, and war supporting industries of six potential adversaries: Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, Syria (a country that might be dropped from the plan soon, if it hasn’t happened already), and a non-state WMD attack.

|

| The Obama administration’s nuclear targeting review appears to have considered a nuclear targeting option similar to what we proposed in this study in 2009. |

Focusing nodal targeting more would not necessarily change how nuclear targeting is performed. Nor does a force level itself of 1,000-1,100 deployed strategic warheads suggest that the day-to-day alert level of the forces has been reduced significantly. Indeed, Smith’s story describes that the review considered, but rejected, a proposal by the State Department, National Security Council staff, and Vice President Biden’s staff to consider changing targeting policy more fundamentally:

“A much steeper reduction, to around 500 total warheads, was debated within the administration last year, but rejected, sources said. Known as the “deterrence only” plan, it would have aimed U.S. warheads at a narrower range of targets related to an enemy’s economic capacity and no longer emphasized striking the enemy’s leadership and weaponry in the first wave of an attack. […]

Some officials at the State Department, the NSC staff, and Vice president Biden’s staff urged consideration of the smaller arsenal and new targeting policy, officials said. But ‘a small brake’ was applied by the Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, who worried that making such a major policy change was too risky at a moment of upheaval in conventional military strategy, and would create too much uncertainty among allies, said one of the sources with knowledge of the discussion.”

This appears to refer to a targeting policy similar to the one FAS and NRDC proposed in our 2009 study From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence as a way of putting an end to Cold War thinking in nuclear planning. President Obama apparently “decided we did not need to do deterrence-only targeting now,” but did not rule it out for later.

Obviously, we have more work to do to put an end to Cold War thinking.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Trimming Nuclear Excess

Despite enormous reductions of their nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, the United States and Russia retain more than 9,100 warheads in their military stockpiles. Another 7,000 retired – but still intact – warheads are awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of more than 16,000 nuclear warheads.

This is more than 15 times the size of the total nuclear arsenals of all the seven other nuclear weapon states in the world – combined.

The U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals are far beyond what is needed for deterrence, with each side’s bloated force level justified only by the other’s excessive force level.

The FAS report – Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces – describes the status and 10-year projection for U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

The report concludes that the pace of reducing nuclear forces appears to be slowing compared with the past two decades. Both the United States and Russia appear to be more cautious about reducing further, placing more emphasis on “hedging” and reconstitution of reduced nuclear forces, and both are investing enormous sums of money in modernizing their nuclear forces over the next decade.

Even with the reductions expected over the next decade, the report concludes that the United States and Russia will continue to possess nuclear stockpiles that are many times greater than the rest of the world’s nuclear forces combined.

New initiatives are needed to regain the momentum of the nuclear arms reduction process. The New START Treaty from 2011 was an important but modest step but the two nuclear superpowers must begin negotiations on new treaties to significantly curtail their nuclear forces. Both have expressed an interest in reducing further, but little has happened.

New treaties may be preferable, but reaching agreement on the complex inter-connected issues ranging from nuclear weapons to missile defense and conventional forces may be unlikely to produce results in the short term (not least given the current political climate in the U.S. Congress). While the world waits, the excess nuclear forces levels and outdated planning principles continue to fuel justifications for retaining large force levels and new modernizations in both the United States and Russia.

To break the stalemate and reenergize the arms reductions process, in addition to pursuing treaty-based agreements, the report argues, unilateral steps can and should be taken in the short term to trim the most obvious fat from the nuclear arsenals. The report includes 32 specific recommendations for reducing unnecessary and counterproductive U.S. and Russian nuclear force levels unilaterally and bilaterally.

New Report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

The US and Russian nuclear arms reduction process needs to be revitalized by new treaties and unilateral initiatives to reduce nuclear force levels, a new FAS report argues (click on image to download report).

By Hans M. Kristensen

Despite enormous reductions of their nuclear arsenals since the Cold War, the United States and Russia retain more than 9,100 warheads in their military stockpiles. Another 7,000 retired – but still intact – warheads are awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of more than 16,000 nuclear warheads.

This is more than 15 times the size of the total nuclear arsenals of all the seven other nuclear weapon states in the world – combined.

The U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals are far beyond what is needed for deterrence, with each side’s bloated force level justified only by the other’s excessive force level.

A new FAS report – Trimming Nuclear Excess: Options for Further Reductions of U.S. and Russian Nuclear Forces – describes the status and 10-year projection for U.S. and Russian nuclear forces.

The report concludes that the pace of reducing nuclear forces appears to be slowing compared with the past two decades. Both the United States and Russia appear to be more cautious about reducing further, placing more emphasis on “hedging” and reconstitution of reduced nuclear forces, and both are investing enormous sums of money in modernizing their nuclear forces over the next decade.

Even with the reductions expected over the next decade, the report concludes that the United States and Russia will continue to possess nuclear stockpiles that are many times greater than the rest of the world’s nuclear forces combined.

New initiatives are needed to regain the momentum of the nuclear arms reduction process. The New START Treaty from 2011 was an important but modest step but the two nuclear superpowers must begin negotiations on new treaties to significantly curtail their nuclear forces. Both have expressed an interest in reducing further, but little has happened.

New treaties may be preferable, but reaching agreement on the complex inter-connected issues ranging from nuclear weapons to missile defense and conventional forces may be unlikely to produce results in the short term (not least given the current political climate in the U.S. Congress). While the world waits, the excess nuclear forces levels and outdated planning principles continue to fuel justifications for retaining large force levels and new modernizations in both the United States and Russia.

To break the stalemate and reenergize the arms reductions process, in addition to pursuing treaty-based agreements, the report argues, unilateral steps can and should be taken in the short term to trim the most obvious fat from the nuclear arsenals. The report includes 32 specific recommendations for reducing unnecessary and counterproductive U.S. and Russian nuclear force levels unilaterally and bilaterally.

Full report: Trimming Nuclear Excess

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Detailed Data For US Nuclear Forces Counted Under New START Treaty

|

| Air Force personnel perform New START Treaty inspection training on a Minuteman III ICBM payload section at Minot AFB in 2011. Nearly two years into the treaty, there have been few reductions of U.S. deployed strategic nuclear forces. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. State Department today released the full (unclassified) and detailed aggregate data categories for U.S. strategic nuclear forces as counted under the New START treaty. This is the forth batch of data published since the treaty entered into force in February 2011.

Although the new data shows a reduction compared with previous releases, a closer reading of the documents indicates that changes are due to adjustments of delivery vehicles in overhaul at any given time and elimination on so-called phantom platforms, that is aircraft that carry equipment that make them accountable under the treaty even though they are no longer assigned a nuclear mission. Actual reduction of deployed nuclear delivery vehicles has yet to occur.

The joint U.S.-Russian aggregate data and the full U.S. categories of data are released at different times and not all information is made readily available on the Internet. Therefore, a full compilation of the September data is made available here.

Overall U.S. Posture

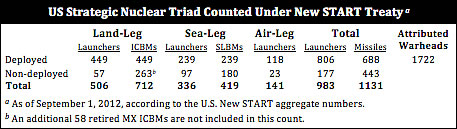

The data attributes 1,722 warheads to 806 deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers as of September 1, 2012. This is a reduction of 15 deployed warheads and 6 deployed delivery vehicles compared with the previous data set from March 2012.

A large number of non-deployed missiles and launchers that could be deployed are not attributed warheads.

The data shows that the United States will have to eliminate 234 launchers over the next six years to be in compliance with the treaty limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers by 2018. Fifty-six of these will come from reducing the number of launch tubes per SSBN from 24 to 20, roughly 80 from stripping B-52Gs and nearly half of the B-52Hs of their nuclear capability, and destroying about 100 old ICBM silos.

The released data does not contain a breakdown of how the 1,722 deployed warheads are distributed across the three legs of the Triad. But because the bomber number is disclosed and each bomber counts as one warhead, and because 450-500 warheads remain on the ICBMs (downloading to one warhead per ICBM was scheduled to resume in 2012), it appears that the deployed SLBMs carry 1,104 to 1,154 warheads, or more than two-thirds of the total number of warheads counted by New START.

Just to remind readers: the New START numbers do not represent the total number of nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal – only about a third. The total military stockpile is just under 5,000 warheads, with several thousand additional retired (but still intact) warheads awaiting dismantlement. For an overview, see this article.

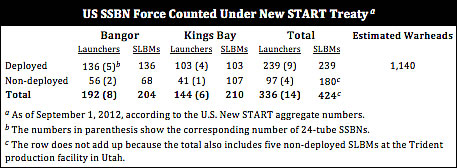

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The New START data shows that the United States as of September 1, 2012, had 239 Trident II SLBMs onboard its SSBN fleet, a reduction of three compared with March 2012. That is only enough to fill nine SSBNs to capacity, but it doesn’t reflect an actual reduction of SLBMs or SSBNs but a fluctuation in the number of SLBMs onboard SSBNs during overhaul. Each SSBN has 24 missile tubes for a maximum loadout of 288 missiles (48 tubes on two SSBNs in overhaul are not counted), but at the time of the New START count it appears that two or three of the 14 SSBNs were empty (including the two in refueling overhaul) and two or three were only partially loaded (in missile loadout).

It is widely assumed that 12 out of 14 SSBNs normally are deployable, but the various sets of aggregate data all indicate that the force ready for deployment at any given time may be closer to 10. This ratio can fluctuate significantly and in average 64 percent (8-9) of the SSBNs are at sea with roughly 920 warheads. Up to five of those subs are on alert with 120 missiles carrying an estimated 540 warheads – enough to obliterate every major city on the face of the earth.

Of the eight SSBNs based at Bangor (Kitsap) Submarine Base in Washington, the data indicates that three were out of commission on September 1, 2012: one had empty missile tubes (possibly because it was in dry dock) and two others were only partially loaded. This means that five SSBNs from the base were fully loaded and probably deployed with 120 Trident II D5 missiles carrying some 540 warheads at the time of the New START count.

For the six SSBNs based at Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia, the New START data shows that 103 missiles were counted as deployed on September 1, 2012. That number is enough to load four SSBNs, with two other SSBNs only partially loaded. The four deployed SSBNs probably carried 96 Trident II SLBMs with some 430 warheads.

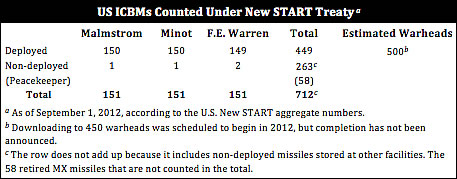

Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

The New START data shows that the United States deployed 449 Minuteman III ICBMs as of September 1, 2012, the same number that was deployed in March 2012. Most were at the three launch bases, but a significant number (321) were at maintenance and storage facilities in Utah. That included 58 MX Peacekeeper ICBMs retired in 2003-2005 but which have not been destroyed.

The New START data does not show how many warheads were loaded on the 449 deployed ICBMs. Downloading to single warhead loading was scheduled to begin in FY2012, but a completion has not been announced. The warhead number is 450-500. The 2010 NPR decided to “de-MIRV” the ICBM force, an unfortunately choice of words because the force will retain the capability to re-MIRV if necessary.

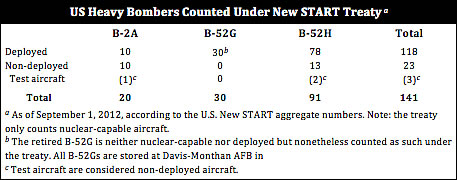

Heavy Bombers

The New START data shows that the U.S. Air Force possessed 141 B-2 and B-52 nuclear-capable heavy bombers as of September 1, 2012. Of these, 118 were counted as deployed, a reduction of four compared with March 2012. The data shows that only half of the B-2 stealth bombers are deployed.

Unfortunately the bomber data is misleading because it counts 30 retired B-52G bombers stored at Davis-Monthan AFB in Arizona as “deployed” at Minot AFB in North Dakota. The mischaracterization is the result of a counting rule in the treaty, which says that bombers can only be deployed at certain bases. As a result, the 30 retired B-52Gs are listed in the treaty as deployed at Minot AFB – even though there are no B-52Gs at that base. According to Air Force Global Strike Command, “There are no B-52Gs at Minot AFB, N.D…In accordance with accounting requirements, we have them assigned to Minot and as visiting Davis-Monthan.” The actual number of deployed heavy bombers should more accurately be listed as 88 B-2A and B-52H, with another 53 non-deployed (including the 30 at Davis Monthan AFB.

All of these bombers carry equipment that makes them accountable under New START, but only a portion of them are actually involved in the nuclear mission. Of the 20 B-2s and 91 B-52Hs in the Air Force inventory, 18 and 76, respectively, are nuclear-capable, but only 60 of those (16 B-2s and 44 B-52Hs) are thought to be nuclear tasked at any given time. None of the aircraft are loaded with nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are attributed a fake count under New START of only one nuclear weapon per aircraft even though each B-2 and B-52H can carry up to 16 and 20 nuclear weapons, respectively. Roughly 1,000 nuclear bombs and cruise missiles are in storage for use by these bombers. Stripping excess B-52Hs and the remaining B-52Gs of their nuclear equipment will be necessary to get down to 60 counted nuclear bombers by 2018.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The New START data released by the State Department continues the decision made last year to release the full U.S. unclassified aggregate numbers, an important policy that benefits international nuclear transparency and counters misunderstandings and rumors.

The latest data set shows that the U.S. reduction of deployed strategic nuclear forces over the past six months has been very modest: 6 delivery vehicles and 15 warheads. The reduction is so modest that it probably reflects fluctuations in the number of deployed weapon systems in overhaul at any given time. Indeed, while there have been some reductions of non-deployed and retired weapon systems, there is no indication from the new data that the United States has yet begun to reduce its deployed strategic nuclear forces under the New START treaty.

Those reductions will come slowly over the next five-six years to meet the treaty limits of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads and 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic delivery vehicles by February 2018. But almost two years after the New START treaty entered into force, it is clear that the Pentagon is not in a hurry to implement it.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12: Contract Signed for Improving Precision of Nuclear Bomb

|

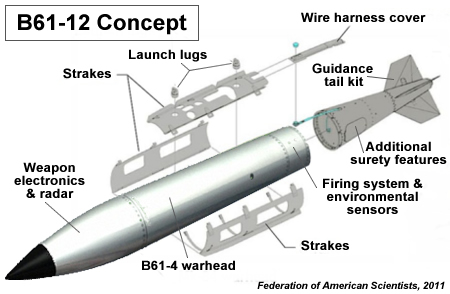

| The first contract was signed yesterday for the development of the guided tail kit that will increase the accuracy of the B61 nuclear bomb. This conceptual drawing illustrates the principle of adding a guided tail kit assembly to the gravity bomb. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force’s new precision-guided nuclear bomb B61-12 moved one step closer to reality yesterday with the Pentagon issuing a $178.6 million contract to Boeing. The contract covers Phase 1 (Engineering and Manufacturing Development) to be completed in October 2015. The contract also includes options for a Phase 2 and production.

In a statement on the contract, Boeing said that the tail kit program “further expands Boeing’s Direct Attack weapons portfolio” and that the precision-guided B61-12 would “effectively upgrade a vital deterrent capability.”

The expensive B61-12 project will use the 50-kiloton warhead from the B61-4 gravity bomb but add the tail kit to increase the accuracy and boost the target kill capability to one similar to the 360-kiloton strategic B61-7 bomb.

Because the B61-4 warhead also has selective lower-yield options, the tail kit will also allow war planners to select lower yields to strike targets that today require higher yields, thereby reducing radioactive fallout of an attack. The Air Force tried in 1994 to get a precision-guided low-yield nuclear bomb (PLYWD), but Congress rejected it because of concern that it would lead to more useable nuclear weapons. Now the Air Force get’s a precision-guided nuclear bomb anyway.

The U.S. Air Force plans to deploy some of the B61-12s in Europe late in the decade for delivery by F-15E, F-16, F-35 and Tornado aircraft to replace the B61-4s currently deployed in Europe. The improved accuracy will increase the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture, which will be further enhanced by delivery of the B61-12 on the stealthy F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Increasing the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture contradicts the Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) adopted in May 2012, which concluded that “the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” Moreover, improving NATO’s nuclear capabilities undercuts efforts to persuade Russia to decrease its non-strategic nuclear forces.

Instead of improving nuclear capabilities and wasting scarce resources, the Obama administration must re-take the initiative to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and work with NATO to withdraw the nuclear weapons from Europe.

See also: Modernizing NATO’s Nuclear Forces: Implications for the Alliance’s Defense Posture and Arms Control

And: Previous blogs about NATO and nuclear weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Modernization Talk at BASIC Panel

|

| Linton Brooks and I discussed nuclear modernization at a November 13 panel organized by BASIC. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

BASIC invited me to discuss nuclear weapons modernization with Linton Brooks at a Strategic Dialogue panel held at the Capitol Hill Club on November 13, 2012. We’re still waiting for the official transcript, but BASIC has a rough recording and my prepared remarks are available here. [Update: all material, including transcript with questions/answers, is available from BASIC].

In my talk, I argued that the Obama administration’s nuclear arms control profile is at risk of being overshadowed by extensive nuclear weapons modernization plans, and that the approach must be adjusted to ensure that efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons and put and end to Cold War thinking are clearly visible as being the priority of U.S. nuclear policy.

The administration has nearly completed a strategic review of nuclear targeting and alert requirements to identify additional reductions of nuclear forces. Release of the findings was delayed by the election, but the administration now needs to use the review to reinvigorate the nuclear arms reduction agenda that has slowed with the slow implementation of the modest New START Treaty and the disappointing “nuclear status quo” decision of the NATO Chicago Summit.

Recommendations to Prevent Catastrophic Threat

Only three days after the 2012 national election, FAS hosted a day-long symposium that featured distinguished speakers and provided recommendations to the Obama administration on how best to respond to catastrophic threats to national security at the National Press Club in Washington, DC.

These experts addressed the policy and technological aspects of conventional, nuclear, biological and chemical weapons; nuclear safety; electricity generation, distribution, and storage, and cyber security. These policy memoranda call for a coordinated national effort to prepare for, prevent and respond to catastrophic threats to the United States.

Germany and B61 Nuclear Bomb Modernization

|

| During a recent visit to Germany I did an interview with the Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk magazine FAKT on the status of the B61 nuclear bomb modernization. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week, I was in Berlin to testify before the Disarmament Subcommittee of the German Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee on the future of the U.S. B61 nuclear bombs in Europe (see my prepared remarks and fact sheet).

One of the B61 bombs currently deployed in Europe is scheduled for an upgrade to extend its life and add new military capabilities and use-control features. The work has hardly begun but the project is already behind schedule and the cost has increased by more than 150 percent in two years, from $4 billion to $10.4 billion. The subcommittee wanted to know if the program is in trouble. I said I believe it certainly is.

The German television magazine FAKT did an interview (article; video) with me and it came as somewhat of a surprise to them that the B61 life-extension will not install a fire-resistant pit to improve the safety of the weapon. They also tried to get German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle on the program. The policy of the German government coalition is to try to have nuclear weapons removed from Germany and Westerwelle has publicly promoted this position clearly in the past. This time he did not want to talk, however, as journalists and camera-teams chased him down the hallway. He may have gotten shell-shocked by the pushback from the old nuclear guard in NATO.

|

| German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle did not want to talk with MDR FAKT about withdrawal of US nuclear weapons. |

.

Although NATO recently determined that the current nuclear posture in Europe meets the Alliance’s deterrence and defense needs, NATO has decided – with German backing – to introduce a new precision-guided nuclear bomb in Europe with increased military capabilities at the end of the this decade for delivery by a new stealthy aircraft.

During my briefing to the foreign affairs committee I urged Germany to continue to push for a withdrawal. Otherwise it will have to explain to the German public why it has decided instead to support deployment of precision-guided nuclear bombs on stealth-delivered aircraft in Europe. The two positions will be hard to square.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Cuban Missile Crisis: Nuclear Order of Battle

|

| At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis blockade, unknown to the United States, the Soviet Union already had short-range nuclear weapons on the island, such as this FKR-1 cruise missile, that would most likely have been used against a U.S. invasion. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Fifty years ago the world held its breath for a few weeks as the United States and the Soviet Union teetered on the brink of nuclear war in response to the Soviet deployment of medium-range nuclear missiles in Cuba.

The United States imposed a military blockade around Cuba to keep more Soviet weapons out and prepared to invade the island if necessary. As nuclear-armed warships sparred to enforce and challenge the blockade, a few good men made momentous efforts and decisions that prevented use of nuclear weapons and eventually defused the crisis.

What the Kennedy administration did not know, however, was that the Soviet Union had 158 nuclear warheads of five types already in Cuba by the time of the blockade. This included nearly 100 warheads for short-range ballistic missiles and cruise missiles. If the invasion had been launched, as the military recommended but the White House fortunately decided against, it would most likely have triggered Soviet use of those short-range nuclear weapons against the U.S. Naval Base at Guantanamo and at amphibious forces storming the Cuban beaches. That, in turn, would have triggered wider use of nuclear forces.

In our latest Nuclear Notebook – The Cuban Missile Crisis: a nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962 – we outline the nuclear order of battle that the United States and the Soviet Union had at their disposal. At the peak of the crisis, the United States had some 3,500 nuclear weapons ready to use on command, while the Soviet Union had perhaps 300-500.

The Cuban Missile Crisis order of battle of useable weapons represented only a small portion of the total inventories of nuclear warheads the United States and Russia possessed at the time. Illustrating its enormous numerical nuclear superiority, the U.S. nuclear stockpile in 1962 included more than 25,500 warheads (mostly for battlefield weapons). The Soviet Union had about 3,350.

For all the lessons the Cuban Missile Crisis taught the world about nuclear dangers, it also left some enduring legacies and challenges that are still confronting the world today. Among other things, the crisis fueled a build-up of quick-reaction nuclear weapons that could more effectively hold a risk the other side’s nuclear forces in a wider range of different strike scenarios.

Today, 50 years later and more than 20 years after the Cold War ended, the United States and Russia still have more than 10,000 nuclear weapons combined. Of those, an estimated 1,800 nuclear warheads are on alert on top of long-range ballistic missiles, ready to be launched on short notice to inflict unimaginable devastation on each other. The best way to honor the Cuban Missile Crisis would be to finally end that legacy and take nuclear weapons off alert.

Nuclear Notebook: The Cuban Missile Crisis: A nuclear order of battle, October and November 1962

NATO: Nuclear Transparency Begins At Home

|

| What’s wrong with this picture? Despite NATO’s call for greater nuclear transparency, old-fashioned nuclear secrecy prevents media access to the Nuclear Planning Group. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than six months after NATO’s Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) adopted at the Chicago Summit called for greater transparency of non-strategic nuclear force postures in Europe, the agenda for the NATO defense minister get-together in Brussels this week listed the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) meeting with the usual constraint: “no media opportunity.”

Why should the news media not have access to the NPG meeting just like they have access to other meetings discussing NATO security issues? After all, the high stakes that justified nuclear secrecy in the past disappeared with the demise of the Soviet Union, no urgent military mission is (publicly) attributed to the remaining nearly 200 U.S. nuclear bombs left in Europe, and NATO now officially advocates greater nuclear transparency.

Whatever the reason, the “no media opportunity” is symbolic of the old-fashioned secrecy that continues to constrain NATO nuclear policy discussions. The nuclear planners are insulated deep within the alliance with little or no public scrutiny. Even for NATO officials, tradition, past political statements, and turf can make it difficult to ascertain and question the rationales behind the nuclear posture.

The DDPR determined “that the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” The reasons for that conclusion remain elusive and the news media should have access to the NPG meeting to ask the questions. Not least because the conclusion is now resulting in significant modernization of NATO’s nuclear forces at considerable cost to the Alliance and some of its member countries. Another potential cost is how it will affect relations with Russia.

If NATO wants to increase nuclear transparency, it should and could break with old-fashioned nuclear secrecy and disclose the broad outlines of its non-strategic nuclear deployment in Europe. It is already widely known and NATO’s nuclear members are already transparent about the broad outlines of their strategic nuclear forces – those that unlike the non-strategic weapons in Europe are actually tasked to provide the ultimate security guarantee to the Allies.

Rather than limiting nuclear transparency efforts to prolonged negotiations for what’s likely to be small incremental steps that essentially surrender the agenda to hardliners in Moscow, unilateral disclosure of NATO’s non-strategic posture would jump-start the process, put pressure on Russia to follow suit, and be consistent with the already considerable transparency of NATO’s strategic forces.

See also: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons, FAS, May 2012.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DOD: Strategic Stability Not Threatened Even by Greater Russian Nuclear Forces

A Department of Defense (DOD) report on Russian nuclear forces, conducted in coordination with the Director of National Intelligence and sent to Congress in May 2012, concludes that even the most worst-case scenario of a Russian surprise disarming first strike against the United States would have “little to no effect” on the U.S. ability to retaliate with a devastating strike against Russia.

I know, even thinking about scenarios such as this sounds like an echo from the Cold War, but the Obama administration has actually come under attack from some for considering further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces when Russia and others are modernizing their forces. The point would be, presumably, that reducing while others are modernizing would somehow give them an advantage over the United States.

But the DOD report concludes that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty” (emphasis added).

The conclusions are important because the report come after Vladimir Putin earlier this year announced plans to produce “over 400” new nuclear missiles during the next decade. Putin’s plan follows the Obama administration’s plan to spend more than $200 billion over the next decade to modernize U.S. strategic forces and weapons factories.

The conclusions may also hint at some of the findings of the Obama administration’s ongoing (but delayed and secret) review of U.S. nuclear targeting policy.

No Effects on Strategic Stability

The DOD report – Report on the Strategic Nuclear Forces of the Russian Federation Pursuant to Section 1240 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012 – was obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. It describes the U.S. intelligence community’s projection for the likely development of Russian nuclear forces through 2017 and 2022, the timelines of the New START Treaty, and possible implications for U.S. national security and strategic stability.

Much of the report’s content was deleted before release – including general and widely reported factual information about Russian nuclear weapons systems that is not classified. But the important concluding section that describes the effects of possible shifts in the number and composition of Russian nuclear forces on strategic stability was released in its entirety.

|

| As long as a sufficient number of U.S. SSBNs are at sea, strategic stability is intact even with significantly greater Russian nuclear forces, the DOD says. |

.

The section “Effects on Strategic Stability” begins by defining that stability in the strategic nuclear relationship between the United States and the Russian Federation depends upon the assured capability of each side to deliver a sufficient number of nuclear warheads to inflict unacceptable damage on the other side, even with an opponent attempting a disarming first strike.

Consequently, the report concludes, “the only Russian shift in its nuclear forces that could undermine the basic framework of mutual deterrence that exists between the United States and the Russian Federation is a scenario that enables Russia to deny the United States the assured ability to respond against a substantial number of highly valued Russian targets following a Russian attempt at a disarming first strike” (emphasis added). The DOD concludes that such a first strike scenario “will most likely not occur.”

But even if it did and Russia deployed additional strategic warheads to conduct a disarming first strike, even significantly above the New START Treaty limits, DOD concludes that it “would have little to no effects on the U.S. assured second-strike capabilities that underwrite our strategic deterrence posture” (emphasis added).

In fact, the DOD report states, the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” (more…)