US Nuclear Weapons Base In Italy Eyed By Alleged Terrorists

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two suspected terrorists arrested by the Italian police allegedly were planning an attack against the nuclear weapons base at Ghedi.

The base stores 20 US B61 nuclear bombs earmarked for delivery by Italian PA-200 Tornado fighter-bombers in war. Nuclear security and strike exercises were conducted at the base in 2014. During peacetime the bombs are under the custody of the US Air Force 704th Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a 130-personnel strong units at Ghedi Air Base.

The Italian police said at a press conference today that the two men in their conversations “were referring to several targets, particularly the Ghedi military base” near Brescia in northern Italy.

Ghedi Air Base is one of several national air bases in Europe that a US Air Force investigation in 2008 concluded did not meet US security standards for nuclear weapons storage. Since then, the Pentagon and NATO have spent tens of millions of dollars and are planning to spend more to improve security at the nuclear weapons bases in Europe.

There are currently approximately 180 US B61 bombs deployed in Europe at six bases in five NATO countries: Belgium (Kleine Brogel AB), Germany (Buchel AB), Italy (Aviano AB and Ghedi AB), the Netherlands (Volkel AB), and Turkey (Incirlik AB).

Over the next decade, the B61s in Europe will be modernized and, when delivered by the new F-35A fighter-bomber, turned into a guided nuclear bomb (B61-12) with greater accuracy than the B61s currently deployed in Europe. Aircraft integration of the B61-12 has already started.

Read also:

– Italy’s Nuclear Anniversary: Fake Reassurance For a King’s Ransom

– B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Iran Nuclear Deal: What’s Next?

By Muhammad Umar,

On July 14, 2015, after more than a decade of negotiations to ensure Iran only use its nuclear program for peaceful purposes, Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, Russia, China, France + Germany) have finally agreed on a nuclear deal aimed at preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

Iran has essentially agreed to freeze their nuclear program for a period of ten years, as in there will be no new nuclear projects or research related to advanced enrichment processes. In exchange the West has agreed to lift crippling economic sanctions on Iran that have devastated the country for over a decade.

President Barack Obama said this deal is based on “verification” and not trust. This means that the sanctions will only be lifted after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has verified that Iran has fulfilled the requirements of the deal. Sanctions can be put back in place if Iran violates the deal in any way.

All though the details of the final agreement have not yet been released, based on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreed to in April, some of the key parameters the IAEA will be responsible for verifying are that Iran has reduced the number of centrifuges currently in operation from 19,000 to 6,140, and does not enrich uranium over 3.67 percent for at least 15 years. The IAEA will also verify that Iran has reduced its current stockpile of low enriched uranium (LEU) from ~10,000 kg to 300 kg and does not build any new enrichment facilities. According to the New York Times, most of the LEU will be shipped to Russia for storage. Iran will only receive relief in sanctions if it verifiably abides by its commitments.

Even after the period of limitations on Iran’s nuclear program ends, it will remain a party to the NPT, its adherence to the Additional Protocol will be permanent, and it will maintain its transparency obligations.

The President must now submit the final agreement to the US Congress for a review. Once submitted, the Congress will have 60 days to review the agreement. There is no doubt that there will be plenty of folks in Congress who will challenge the agreement. Most of their concerns will be unwarranted because they lack a basic understanding of the technical details of the agreement.

The confusion for those opposing the deal on technical grounds is simple to understand. Iran had two paths to the bomb. Path one involved enriching uranium by using centrifuges, and path two involved using reactors to produce plutonium. The confusion is that if Iran is still allowed to have enriched uranium, and keep centrifuges in operation, will it not enable them to build the bomb?

The fact is that Iran will not have the number of centrifuges required to enrich weapons grade uranium. It will only enrich uranium to 3.7 percent and has a cap on its stockpile at 300 kilograms, which is inadequate for bomb making.

Again, the purpose of the deal is to allow greater access to the IAEA and their team of inspectors. They will verify that Iran complies with the agreement and in exchange sanctions will be lifted.

Congress does not have to approve the deal but can propose legislation that blocks the execution of the deal. In a public address, the President vowed to “veto any legislation that prevents the successful implementation of the deal.”

The deal will undergo a similar review process in Tehran, but because it has the support of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khameeni, there will be no objection.

Those opposing the deal in the United States fail to understand that although the deal is only valid for 10 to 15 years, the safeguards being put in place are permanent. Making it impossible for Iran to secretly develop a nuclear weapon.

This deal has potentially laid down a blueprint for future nuclear negotiations with countries like North Korea. Once the deal is implemented, it will serve as a testament for diplomacy. It is definitely a welcome change from the experience of failed military action in Iraq, a mess we cannot seem to get out of to this day.

A stable Iran with a strong economy will not only benefit the region but the entire world. The media as well as Congress should keep this fact in mind as they begin to review the details of the final deal.

This is a tremendous victory for the West as well as Iran. This deal has strengthened the non-proliferation regime, and has proven the efficacy of diplomacy.

The writer is a visiting scholar at the Federation of American Scientists. He tweets @umarwrites.

The Risk of Nuclear Winter

Since the early 1980s, the world has known that a large nuclear war could cause severe global environmental effects, including dramatic cooling of surface temperatures, declines in precipitation, and increased ultraviolet radiation. The term nuclear winter was coined specifically to refer to cooling that result in winter-like temperatures occurring year-round. Regardless of whether such temperatures are reached, there would be severe consequences for humanity. But how severe would those consequences be? And what should the world be doing about it?

To the first question, the short answer is nobody knows. The total human impacts of nuclear winter are both uncertain and under-studied. In light of the uncertainty, a risk perspective is warranted that considers the breadth of possible impacts, weighted by their probability. More research on the impacts would be very helpful, but we can meanwhile make some general conclusions. That is enough to start answering the second question, what we should do. In regards to what we should do, nuclear winter has some interesting and important policy implications.

Today, nuclear winter is not a hot topic but this was not always the case: it was international headline news in the 1980s. There were conferences, Congressional hearings, voluminous scientific research, television specials, and more. The story is expertly captured by Lawrence Badash in his book A Nuclear Winter’s Tale.1Much of the 1980s attention to nuclear winter was driven by the enthusiastic efforts of Carl Sagan, then at the height of his popularity. But underlying it all was the fear of nuclear war, stoked by some of the tensest moments of the Cold War.

When the Cold War ended, so too did attention to nuclear winter. That started to change in 2007, with a new line of nuclear winter research2 that uses advanced climate models developed for the study of global warming. Relative to the 1980s research, the new research found that the smoke from nuclear firestorms would travel higher up in the atmosphere, causing nuclear winter to last longer. This research also found dangerous effects from smaller nuclear wars, such as an India-Pakistan nuclear war detonating “only” 100 total nuclear weapons. Two groups—one in the United States3 and one in Switzerland4 — have found similar results using different climate models, lending further support to the validity of the research.

Some new research has also examined the human impacts of nuclear winter. Researchers simulated agricultural crop growth in the aftermath of a 100-weapon India-Pakistan nuclear war.5 The results are startling- the scenario could cause agriculture productivity to decline by around 10 to 40 percent for several years after the war. The studies looked at major staple crops in China and the United States, two of the largest food producers. Other countries and other crops would likely face similar declines.

Following such crop declines, severe global famine could ensue. One study estimated the total extent of the famine by comparing crop declines to global malnourishment data.6 When food becomes scarce, the poor and malnourished are typically hit the hardest. This study estimated two billion people at risk of starvation. And this is from the 100-weapon India-Pakistan nuclear war scenario. Larger nuclear wars would have more severe impacts.

This is where the recent research stops. To the best of my knowledge there are no recent studies examining the secondary effects of famines, such as disease outbreaks and violent conflicts. There are no recent studies examining the human impacts of ultraviolet radiation. That would include an increased medical burden in skin cancer and other diseases. It would also include further loss of agriculture ecosystem services as the ultraviolet radiation harms plants and animals. At this time, we can only make educated guesses about what these impacts would be, informed in part by what research was published 30 years ago.

When analyzing the risk of nuclear winter, one question is of paramount importance: Would there be permanent harm to human civilization? Humanity could have a very bright future ahead; to dim that future is the worst thing nuclear winter could do. It is vastly worse than a few billion deaths from starvation. Not that a few billion deaths is trivial—obviously it isn’t—but it is tiny compared to the loss of future generations.

Carl Sagan was one of the first people to recognize this point in a commentary he wrote on nuclear winter for Foreign Affairs.7 Sagan believed nuclear winter could cause human extinction, in which case all members of future generations would be lost. He argued that this made nuclear winter vastly more important than the direct effects of nuclear war, which could, in his words, “kill ‘only’ hundreds of millions of people.”

Sagan was however, right that human extinction would cause permanent harm to human civilization. It is debatable whether nuclear winter could cause human extinction. Alan Robock, a leader of the recent nuclear winter research, believes it is unlikely. He writes: “Especially in Australia and New Zealand, humans would have a better chance to survive.”8 This is hardly a cheerful statement, and it leaves open the chance of human extinction. I think that’s the best way of looking at it. Given all the uncertainty and the limited available research, it is impossible to rule out the possibility of human extinction. I don’t have a good answer for how likely it is. But the possibility should not be dismissed.

Even if some humans survive, there could still be permanent harm to human civilization. Small patches of survivors would be extremely vulnerable to subsequent disasters. They also could not keep up the massively complex civilization we enjoy today. It would be a long and uncertain rebuilding process and survivors might never get civilization back to where it is now. More importantly, they might never get civilization to where we now stand poised to take it in the future. Our potentially bright future could be forever dimmed.9 Nuclear winter is a very large and serious risk. But that on its own doesn’t mean much—just another thing to worry about. What’s really important are the implications of nuclear winter for public policy and private action.

In some ways, nuclear winter doesn’t change nuclear weapons policy all that much. Everyone already knew that nuclear war would be highly catastrophic. Nuclear winter means that nuclear war is even more catastrophic, but that only reinforces policies that have long been in place, from deterrence to disarmament. Indeed, military officials have sometimes reacted to nuclear winter by saying that it just makes their nuclear deterrence policies that much more effective.10 Disarmament advocates similarly cite nuclear winter as justifying their policy goals. But the basic structure of the policy debates is unchanged.

In other ways, nuclear winter changes nuclear weapons policy quite dramatically. Because of nuclear winter, noncombatant states may be severely harmed by nuclear war. Nuclear winter gives every country great incentive to reduce tensions and de-escalate conflicts between nuclear weapon states. Thankfully, this point has not gone unnoticed at recent international conferences on the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons, such as the December 2014 conference in Vienna, which I spoke at.11These conferences are led by, and largely aimed at, non-nuclear weapon states.

Nuclear weapon states should also take notice. Indeed, the biggest policy implication of nuclear winter could be that it puts the interests of nuclear weapon states in greater alignment. Because of nuclear winter, a nuclear war between any two major nuclear weapon states could severely harm each of the other six. (There are nine total nuclear-armed states, and North Korea’s arsenal is too small to cause any significant nuclear winter.) This multiplies the risk of being harmed by nuclear weapons, while only marginally increasing the benefits of nuclear deterrence. By shifting the balance of harms vs. benefits, nuclear winter can promote nuclear disarmament.

Additional policy implications come from the risk of permanent harm to human civilization. If society takes this risk seriously, then it should go to great lengths to reduce the risk. It could stockpile food to avoid nuclear famine, or develop new agricultural paradigms that can function during nuclear winter.12 It could abandon nuclear deterrence, or shift deterrence regimes to different mixes of weapons.13 And it could certainly ratchet up its efforts to improve relations between nuclear weapon states. These are things that we can do right now, even while we await more detailed research on nuclear winter risk.

Seth Baum is Executive Director of the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute (gcrinstitute.org), a nonprofit think tank that he co-founded in 2011. His research focuses on risk, ethics, and policy questions for major risks to human civilization including nuclear war, global warming, and emerging technologies. The aim of this research is to characterize the risks and develop practical, effective solutions for reducing them. Dr. Baum received a Ph.D. in geography from Pennsylvania State University with a dissertation on climate change policy. He then completed a post-doctoral fellowship with the Columbia University Center for Research on Environmental Decisions. Prior to that, he studied engineering, receiving an M.S. in electrical engineering from Northeastern University with a thesis on electromagnetic imaging simulations. He also writes a monthly column for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

His research has appeared in many journals including Ecological Economics, Science and Engineering Ethics, Science and Global Security, and Sustainability. He is currently co-editor of a special issue of the journal Futures titled “Confronting future catastrophic threats to humanity.” He is an active member of the Society for Risk Analysis and has spoken at venues including the United Nations, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, and the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University.

Mind the Empathy Gap

Here is some news from recent research in neuroscience that, I think, is relevant for FAS’s mission to prevent global catastrophes. Psychologists Dacher Keltner of the University of California, Berkeley, and Jonathan Haidt of New York University, have argued that feelings of awe can motivate people to work cooperatively to improve the collective good.1Awe can be induced through transcendent activities such as celebrations, dance, musical festivals, and religious gatherings. Prof. Keltner and Prof. Paul Piff of the University of California, Irvine, recently wrote in an opinion article for the New York Times that “awe might help shift our focus from our narrow self-interest to the interests of the group to which we belong.”2 They report that a forthcoming peer reviewed article of theirs in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, “provides strong empirical evidence for this claim.”

Their research team did surveys and experiments to determine whether participants who said they experienced awe in their lives regularly would be more inclined to help others. For example, one study at UC, Berkeley, was conducted near a spectacular grove of beautiful, tall Tasmanian blue gum eucalyptus trees. The researchers had participants either look at the trees or stare at the wall of the nearby science building for one minute. Then, the researchers arranged for “a minor accident” to occur in which someone walking by would drop a handful of pens. “Participants who had spent the minute looking up at the tall trees—not long, but long enough, we found, to be filled with awe—picked up more pens to help the other person.”

Piff and Keltner conclude their opinion piece by surmising that society is awe-deprived because people “have become more individualistic, more self-focused, more materialistic and less connected to others.” My take away is that this observation has ramifications for whether people will band together to tackle the really tough problems confronting humanity including: countering and adapting to climate change, alleviating global poverty, and preventing the use of nuclear weapons. I find it interesting that Professors Piff and Keltner have mentioned shifting individuals’ interest to the group to which those people belong.

What about bringing together “in groups” with “out groups”? Can awe help or harm? Here’s where, I believe, the geopolitical and neuroscience news is mixed. First, let’s look at the bad news and then finish on a positive message of recent psychological research showing interventions that might alleviate the animosity between groups who are in conflict.

While awe can be inspiring, a negative connotation toward out groups is implicit in the phrase “shock and awe” in the context of massive demonstration of military force to try to influence the opponent to not resist the dominant group. Many readers will recall attempted use of this concept in the U.S.-led military campaign against Iraq in March and April 2003. U.S. and allied forces moved rapidly with a demonstration of impressive military might in order to demoralize Iraqi forces and thus result in a quick surrender. While Baghdad’s political power center crumbled quickly, many Iraqi troops dispersed and formed the nuclei of the insurgency that then opposed the occupation for many years to come.3 Thus, in effect, the frightening awe of the invasion induced numerous Iraqis to band together to resist U.S. forces rather than universally shower American troops with garlands.

Nuclear weapons are also meant to shock and awe an opponent. But the opponent does not have to be cowed into submission. To deter this coercive power, the leader of a nation under nuclear threat can either decide to acquire nuclear weapons or form an alliance with a friendly nation that already has these weapons. Other nations that do not feel directly threatened by another nation’s nuclear weapons can ignore these threats and tend to other priorities. This describes the world we live in today. Most of the world’s nations in Central Asia, Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia are in nuclear-weapon-free-zones and have opted out of nuclear confrontations. But in many countries in Europe, North America, East Asia, South Asia, and increasingly the Middle East, nuclear weapons have influenced decision makers to get their own weapons and increase reliance on them (for example, China, North Korea, Pakistan, and Russia), acquire a latent capability to make these weapons (for example, Iran), or request and receive protection from nuclear-armed allies (for example, non-nuclear countries of NATO, Japan and South Korea).

Is this part of the world destined to always figuratively sit on a powder keg with a short fuse? Perhaps if people in these countries can close the empathy gap, they might reduce the risk of nuclear war and eventually find cooperative security measures that do not require nuclear weapons. Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Empathy is a natural human capacity especially when dealing with people who share many common bonds.

If we can truly understand someone we now perceive to be an enemy, would we be less likely to want to do harm to that person or other members of his or her group? Empathic understanding between groups is not a guarantee of conflict prevention, but it does appear to offer a promising method for conflict reduction. However, as psychological research has shown, failures of empathy often occur between groups that are socially or culturally different. People in one group can also feel pleasure in the suffering of those in the different group, especially if that other group is dominant. The German word schadenfreude captures this delight in others’ suffering. Competitive groups especially exhibit schadenfreude; for example, Boston Red Sox fans experience glee when the usually dominant New York Yankees lose to a weaker opponent.4

Are there interventions that can disrupt this negative behavior and feelings? Cognitive scientists Mina Cikara, Emile Bruneau and Rebecca Saxe point out that “historical asymmetries of status and power between groups” is a key variable.5 If the same intervention method such as asking participants to take the perspective of the other into account is used for both groups, different effects are observed. For example, the dominant group tends to respond most positively to perspective taking in which members of that group would listen attentively to the perspective or views of the other group. A positive response means that people’s attitude toward the other group becomes favorable. In contrast, the non-dominant group’s members often experience a deepening of negative attitudes toward the dominant group if they engage in perspective taking. Rather, members of the non-dominant group show a favorable change in attitude when they perform perspective giving toward the dominant group. Importantly, they have to know that members of the dominant group are being attentive and really listening to the non-dominant group’s perspective. In other words, the group with less or no political power needs to be heard for positive change to occur. While these results seem to be common sense, Bruneau and Saxe point out that almost always perspective taking is used in interventions intended to bring asymmetric groups together and often this conflict resolution method fails. Their research underscores the importance of perspective giving, especially for non-dominant groups.6

This research shows promising results that could have implications for bridging the divide between Americans and Iranians on the different views on nuclear power, for example, or the gap between Americans and Chinese on the implications of the U.S. pivot toward East Asia and the Chinese rise in economic, military, and political power. I conclude this president’s message with encouragement to cognitive scientists in the United States and other nations to apply these and other research techniques to the grand social challenges such as how to get people across the globe to work together to mitigate the effects of climate change and to achieve nuclear disarmament through cooperative security.

Who was Willy Higinbotham?

Editor’s note: The following is a compilation of letters by Dr. William Higinbotham, a nuclear physicist who worked on the first nuclear bomb and served as the first chairman of FAS. His daughter, Julie Schletter, assembled these accounts of Higinbotham’s distinguished career.

Thank you for this opportunity to share with you my father’s firsthand accounts of the inception of the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). After my father died in November 1994, I inherited a truly intimidating treasure of letters, correspondence and most importantly a nearly complete manuscript (mostly on floppy disks) of his unpublished memoirs. Over the last couple of decades, I have read widely and deeply, collected resources, transcribed and sorted through this material and am planning to publish a personal history of Willy in the near future.

William Higinbotham

Having studied this man from a more distant perspective, I am sure about certain things. Willy was at his heart an optimist, a democrat, a child of liberal New England Protestants during the Great Depression, and a man who didn’t mind doing a lot of behind the scenes dirty work to make things happen. He did this with self-deprecating humor, confidence in the humanity of others, a terrific sense of play, music, camaraderie, and most importantly a deep respect for the opinions of everyone. He was humble, incredibly brilliant and could recall details from meetings many years in the past as well as lyrics to jazz standards and sea chanties not sung in a while.

Dad was a terrific story teller. This is his version of how he came to Washington, DC to serve as the first chairman of FAS. These are mostly his words with some additional anecdotes from colleagues and friends who knew him well during the war years and after.

In a letter to his daughter Julie in April 1994, Willy began his account with his parents, a beloved Presbyterian minister and wife:

“It is from them and their example that I have been inspired to do something for humanity. In my case, the opportunity did not arise until I was 30 and the Second World War had started. As a graduate student at Cornell I was too poor to consider marriage and had no prospects for a reasonable job. As soon as Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany, I knew that the US should prepare to go to war with our European allies. However, the vast majority of US citizens and Congressmen believed that we should have nothing to do with any European conflicts. It was only with difficulty that President Roosevelt was able to provide some assistance to the UK by “Lend Lease.” I was delighted to be invited to go to MIT in Jan. 1941, as Hitler’s Luftwaffe was bombing London and other British cities.

The US finally initiated the draft in March or April and (my brother) Robert was one of the first to be called up. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor that fall, we were in the war for good. (My brother) Freddy was the next to be drafted. By the summer of 1943 he was a navigator on a small C47 transport plane that dropped parachuters on Sicily, and then (my brother) Philip was drilling with the Army Engineers. I had strong reasons to develop technology that would speed defeat of Germany and Japan.

As you know, it was when I saw the first nuclear test on July 16, 1945, that I determined to do what I could to prevent a nuclear arms race.”

Willy and his wife Julie

From his unpublished memoirs, Willy described the Trinity test:

“Until the last moment, it was not clear if the implosion design [which used plutonium] would actually work. Everyone was confident that the gun design [which used highly enriched uranium] would work, but Hanford was producing plutonium at a good rate while Oak Ridge was producing highly enriched uranium with great difficulty. Consequently, the Trinity test was planned for early in 1945.

Almost everyone in Los Alamos was involved in constructing the implosion weapon or in designing and installing measurement instruments for the test. Most of my group was involved in the latter. Sometimes I drove, with others, to the site to install and test various devices. Many of the instruments were to be turned on minutes or seconds before the bomb was to be triggered. Joe McKibben, of the Van de Graff group, designed the alarm-clock and relay system which was to send out signals for the last ten minutes. I designed the electronic circuit which was to send out the signals during the last second and then to send the signal to the tower. Some of my scientists and many of my technicians spent many days at the site. By test day, we had done all that was requested and I was prepared to await the results of the test, at Los Alamos.

At the last minute, I had a call from Oppie [Scientific Director J. Robert Oppenheimer], asking me to bring a radio to the test site for a number of special observers who were to be at 18 miles from the tower. We had an all-wave Halicrafters receiver which needed a storage battery for the filaments and a stack of big 45 volt B-batteries for the plates. We also had several cheap loud speakers. So, I grabbed several of the remaining technicians and had them check the equipment and pack it into a small truck. They drove the truck to the site. I went with some of the special guests by bus to Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque, whence a military bus took us to the place reserved for us, near where the road to the test site leaves the main highway north of it.

We arrived there in the evening. As has been reported often, the weather clouded over and there was some rain. So we waited. The radio worked although the sound was rather weak. The Halicrafter had less than a watt of output and the speakers were not very efficient. Eventually, the countdown began. We were issued slabs of very dark glass, used by welders. I couldn’t see the headlights on the truck through it. I only remember one of the others who was in our select group, Edward Teller. As the countdown approached the last 10 seconds, he began to rub sun screen on his face, which rather shook me. I had been assured that the bomb, if it worked, would not ignite the atmosphere or the desert. At 18 miles it seemed incredible to me that we might get scorched.

At T = 0, we saw a brilliant white flash of light through our dark glass filters, and the hills around us were suddenly brightly lit. Immediately, the point of light expanded to a white sphere and then to a redder inverted bowl shaped object which began to be surrounded with eddies and then rose up into the air and climbed rapidly to the sky, where a clear space suddenly opened in the high thin cloud layer and finally ended as an ugly white cap. All up and down the smoky column there were bluish sparks due to the radioactivity and electric discharges. It must have been more than a minute before the shock wave came through the ground, followed shortly by the sharp air-wave blast, which rumbled off the hills for another minute or so. It was clear that the bomb worked as predicted. I had hoped that the physicists might have been wrong and for many reasons I figured that this test would not be successful. Now I had to face the existence of nuclear weapons. It was a paralyzing realization.

As I recall, no one said anything. My boys packed up the radio equipment and headed home. I got into a bus with about fifteen others and we started for Albuquerque. I had saved one of the bottles of scotch, which my MIT friends had given me in 1943, and had it with me, in case. I pulled it out, opened it, and passed it around. The others on the bus, scientists and military types, quietly sipped it and passed it along until it was empty. No one said anything.

Several hours later we arrived at Kirtland and those of us from Los Alamos transferred to another bus to return there. I was paralyzed. I went back to the Lab and doodled there until closing time. I had supper and went to my room. I didn’t sleep. All I could think of was that the Soviet Union would surely develop nuclear weapons and might blow us off the map. I knew about radar and anti-aircraft and that a bomb, such as the one I had seen, would wipe out any city. The best defense against bombers in Europe had been to shoot down ten percent of the attackers. Ninety percent would not save us.

After agonizing for a day or more, I finally began to think about why Stalin might attempt to destroy the US. It was quite possible that Soviet aircraft could cross the oceans and attack the US. However, it would do them no good to just destroy cities. They would have to occupy us to gain any advantage. The more I thought about this, the more I came to believe that attacking the US with nuclear weapons would not make sense even to an evil man like Stalin. What might make more sense would be to use nuclear weapons to attack our allies in Europe. By then it was clear that Stalin intended to continue to occupy Poland, Hungary and other previously free countries that surrounded the Soviet Union. (In my mind) at least the US did not seem to be threatened. There would be time to see if the Soviet Union was going to threaten the other nations beyond those it now controlled. (Eventually) I got some sleep and went back to work on the new jobs which faced the Lab.

I had no intention of taking a major role in this effort. As soon as Japan surrendered, many of the scientists at Los Alamos began to discuss this subject. When General Groves said that we could keep the secret for 15 years, and Congressmen told scientists to design a defense, we held a big meeting and started to draft a statement for the public.”

In a letter Dad wrote to his mother from Los Alamos:[ref]Jungk, Robert. Brighter Than a Thousand Suns. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1958 p 223.[/ref]

“I am not a bit proud of the job we have done . . . the only reason for doing it was to beat the rest of the world to a draw . . . perhaps this is so devastating that man will be forced to be peaceful. The alternative to peace is now unthinkable. But unfortunately there will always be some who don’t think. . . . I think I now know the meaning of “mixed emotions.” I am afraid that Gandhi is the only real disciple of Christ at present . . . anyway it is over for now and God give us strength in the future. Love, Will.”

From his memoirs, Willy described how he came to Washington, DC in the fall of 1945:

“Strangely, I don’t remember many discussions of the implications of nuclear weapons at Los Alamos before the end of the war. My friends and I had some scattered discussions about how Nazism had taken hold, and of what the world might face after Hitler was defeated. I was invited a few times to sit in Oppie’s living room as Niels Bohr discussed his thoughts about the future control of atomic energy. Bohr was almost impossible to understand because he had an accent and because he always spoke several decibels below the audible threshold. Much later I would understand how wise he was, but at the time the whole subject seemed confusing and not very important to me.

Then came Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender. We had a big party the night the surrender was announced. I sat on the hood of a jeep, playing my accordion, as we paraded around town. Immediately after that, the discussions began in earnest. A number of them were held in my office in the Tech area in the evenings. The public response to the development of atomic weapons was discouraging. General Groves asserted that it would take the Soviets fifteen years to develop an atomic weapon. Congressmen began talking about defenses. Scientists at Oak Ridge and Chicago were organizing and we began to hear from them.

The first large meeting was attended by about sixty people on August 20th. All agreed that we should form an organization and the question of whether it should consider scientists’ welfare as well as the social implications of nuclear energy, was discussed. A committee was appointed to make arrangements for a meeting for all of the scientists and engineers.

On August 23rd, a nine member committee issued an invitation to attend a meeting for all scientists and engineers on August 30th for the following purpose:

“Many people have expressed a desire to form an organization of progressive scientists which has as its primary object to see that the scientific and technological advancements for which they are responsible are used in the best interests of humanity.

Most scientists on this project feel strongly their responsibility for the proper use of scientific knowledge. At present, recommendations for the future of this project and of atomic power are being made. It would be the immediate purpose of this society to examine our own views on these questions and take suitable action. However, the future will hold more problems and scientists will feel the need of a more general organization to express their views.

Before the next meeting had been held it was clear to everyone that the international control of atomic energy was the vital issue and should be the only issue with which the organization was concerned.”

The meeting on August 30th was attended by about five hundred individuals. They overwhelmingly approved the following motion by Joe Keller:

- We hereby form an organization of scientists, called temporarily, the Association of Los Alamos Scientists (ALAS).

- The object of this organization is to promote the attainment and use of scientific and technological advances in the best interests of humanity. We recognize that scientists, by virtue of their special knowledge, have, in certain spheres, special social responsibilities beyond their obligations as individual citizens. The organization aims to carry out these responsibilities by keeping its members informed and by providing a forum through which their views can be publicly and authoritatively expressed.

We discussed what our statement should say to the President and to the public. Except for Edward Teller, we all agreed that the message was that (1) there is no secret (scientists anywhere could figure out how to make atomic weapons now that we had demonstrated that they are possible). In addition, (2) there is no defense that can prevent great devastation by atomic weapons, and (3) we must have “world control.” Edward Teller would not agree with the latter because that was a political and not a technical conclusion. Leo Szilard’s counter to this, we later heard, was that you don’t shout “fire” in a crowded theater without telling people where the exits are. Anyway, the three phrases became our policy.

To my great surprise, I was elected the first chairman of the Association of Los Alamos Scientists. Later, I went to Washington and offered to spend a year managing the scientists’ office. Then I was elected the first chairman of the Federation of American Scientists in January, 1946. I was surprised and hoped that I would not let people down. I think that I understand this. I do not have strong beliefs as did Leo Szilard and many others. I was not a Nobel laureate. I was a team worker. I sought to unite people on positions that they could agree to. People trusted me.

The first executive committee was composed of David Frisch, Joseph Keller, David Lipkin, John Manley, Victor Weisskopf, Robert Wilson, William Woodward, and myself (chairman).

From the beginning, we were aware that the scientific and military success of our work would bring both new dangers and new possibilities of human benefits to the world.

We posed and answered five questions:

- What would the atomic bomb do in the event of another war?

- Use of such bombs would quickly and thoroughly annihilate the important cities in all countries involved. We must expect that bombs will be developed which will be many times more effective and which will be available in large numbers.

- What defense would be possible? One hundred percent interception should be considered impossible. Therefore, were there a possibility of attack we could not gamble on defenses alone and would have to make drastic changes such as abandoning cities and decentralizing communications. How long would it take for any other country to produce as atomic bomb? Within a few years.

- What would be the effect of an atomic arms race on science and technology? Emphasis on the development of more weapons would interfere with developments for peaceful applications.

- Assuming that international control of the bomb is agreed upon, is such control technically feasible? From a scientific point of view we assert that international control of the atomic bomb is feasible and that such control need not interfere with free and profitable peacetime research and development.

Like everyone else, I visited congressmen, talked to reporters, lectured to local organizations and answered phone calls. A large part of the public was interested in atomic energy. A number of the leaders of major national organizations visited us or asked us to meet with them.

When the Soviets fired their first nuclear test in 1949, the President and the Congress pushed for development of the H bomb, which stimulated the nuclear arms race. It was a sad story after that. Edward Teller was convinced that the Soviets would blow up the US if it ever had the opportunity to do so without suffering much retaliation. More rational people felt that the Soviets would have enough trouble keeping on top of their people and satellites, especially after Stalin died in 1970. I could go on. The US became paranoid about communists. Joseph McCarthy lied but many innocent people lost their jobs. Oppenheimer was publicly disgraced. The US continued to accelerate the nuclear arms race. By good luck, the US and USSR agreed to halt tests in the atmosphere in 1963 and the Cuban missile crisis did not lead to the Apocalypse, though that was close. I have spent a lot of my time and effort trying to influence US policy in this area. A lot of that was spent talking to the already converted. My friends and I have had some minor successes. But we never could convince our government that the nuclear arms race was unnecessary and that the Soviets would respond favorably if we were to suggest winding it down. It was the Soviet leaders, with Gorbachev, who realized that the arms race was a waste of effort and who were willing to take the risk of offering to reduce their deployed nuclear weapons and go further if the US agreed.

If we and others are to survive, we must understand the present situation and try to find new and better ways to deal with international problems. The development of nuclear weapons means that the traditional policies will probably fail. I have had a few opportunities to discuss this with some of the doubters. Most of the time, however, the people that I talked to were sympathetic to our attempts at developing a new approach.

So, the objective that I devoted so much time, effort, and thought to was finally attained by the Soviets. Most of the time I was discouraged but did not give up. A number of the scientists who were active at the start gave up. Some of the scientists that I have worked with thought that I was crazy — but they never took the trouble to find out what I knew about what was going on or what I was really doing. There were many distinguished scientists who thought as I did, and we encouraged each other. They have been a great help to me.”

These last few anecdotes come from the many letters that were sent to my father on the occasion of his 80th birthday. I believe they speak to the qualities that made Dad so incredibly successful at ALAS, FAS, and then on to Brookhaven National Laboratory where he worked on an astounding number of projects and committees, and where he established the Technical Support Organization Library. During his tenure at BNL he attended some of the Pugwash meetings, SALT talks and traveled extensively all over the world to communicate honestly with scientists and policy makers regarding atomic energy and nuclear safeguards.

He also built the prototype for Pong in the mid-fifties as a demonstration exhibit for the public and guests at the summer open lab events. He was “discovered” by computer gamers all over the world by around 1972. Dad was mortified by this! He thought anyone with a simple understanding of electronics could have invented that sort of game just as easily as he did! He bemoaned the idea that he would be remembered not for his life’s work on nuclear non-proliferation, but on a silly computer game. And (regrettably) he was right about that.

Willy on Long Island with his beloved accordion around 1951

Jim de Montmollin, colleague from the Manhattan Project:

“I think the most important thing to me is your sensitivity and selflessness. In an era when people seek to project an image of sophistication through a cynical and ‘me first’ attitude toward everything, I especially value knowing people like you. I think of myself also as a sort of pragmatic idealist, and I consider you to be the ultimate model. Far more than I, you have worked tirelessly toward unselfish objectives, always seeking practical and feasible steps toward getting there.

I also admire your tolerance. You don’t hesitate to call it like you see it, but neither are you ever hesitant to defend any cause or individual, however unpopular or unfashionable they may be. That is what has always made it such a pleasure to discuss anything with you: it [is] rare to know people who think for themselves, who absorb new information and develop their thoughts from it, who are more than carriers of the conventional wisdom, and who are so well—informed on so many things as you. What I refer to as your tolerance is both an openness toward new facts and ideas and a lack of animosity toward those who differ in any way.

Your dedication and drive over at least the last 50 years toward objectives that are not self-seeking or necessarily fashionable is another aspect that makes you so outstanding to me. Long before I knew you, you did it at no small personal sacrifice. When you became too old to meet the bureaucratic rules for continued work, you have worked as hard as ever, taking advantage of the freedom to apply yourself wherever you could be the most effective. If you ever have any private doubts about what you may have sacrificed, let me assure you that I appreciate and admire you for it.

I remember you commenting on more than one occasion that you regarded George Weiss as a ‘real gentleman.’ I agree, but that also applies to you even more so. It is your sensitivity to others’ feelings, your tolerance of their shortcomings, and your efforts to point out their good qualities that mark you as a gentleman to me, in the finest sense of the word.”

From Freeman Dyson, English-born American theoretical physicist and mathematician:

“I am delighted to hear that the FAS headquarters building is to be named in your honor. In this way we shall celebrate the historic role that you played in the beginnings of FAS. And we make sure that future generations did not forget who you were and what you did.

I remember vividly the day I joined FAS, soon after I arrived in the USA as a graduate student in 1947. Gene Lochlin, who was a fellow student at Cornell, took me to an FAS meeting and I was immediately hooked. One of the things that attracted me most strongly to FAS was the spontaneous and un-hierarchical way in which [it] should function. Coming fresh from England, I found it amazing that the leader of FAS was not Sir Somebody-Something, but this young fellow Willy Higinbotham who had grabbed the initiative in 1945 and organized the crucial dialogue between scientists and congressmen.

And [by] 1947 you were already a legendary figure, a symbol of the ordinary guy who changes history by doing the right thing at the right time. To me you were also a symbol of the good side of America, the open society where everyone is free to make a contribution. You just happen to make one of the biggest contributions. I am proud now to join and honoring your achievement.”

The world has certainly changed since the atomic bomb first exploded over the white sands of New Mexico in July 1945, yet it is clear that in regard to nuclear non-proliferation and world peace we have a mighty long way to go. William Higinbotham served as the first chairman of FAS in 1945; the mission and objectives were clear and imperative. The work he began now continues 70 years later. On behalf of my father, thank you for your most noble efforts to make our world a safer and saner place for all of humanity.

Julie Schletter retired in 2013 after almost forty years working in education as a school counselor. Her recent project has been completing a book about her father, Accordion to Willy: A Personal History of William Higinbotham the Man who Helped Build the Atom Bomb, Launched the Federation of American Scientists and Invented the First Video Game.

The False Hope of Nuclear Forensics? Assessing the Timeliness of Forensics Intelligence

Nuclear forensics is playing an increasing role in the conceptualization of U.S. deterrence strategy, formally integrated into policy in the 2006 National Strategy on Combatting Terrorism (NSCT). This policy linked terrorist groups and state sponsors in terms of retaliation, and called for the development of “rapid identification of the source and perpetrator of an attack,” through the bolstering of attribution via forensics capabilities.12 This indirect deterrence between terrorist groups and state sponsors was strengthened during the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit when nuclear forensics expanded into the international realm and was included in the short list of priorities for bolstering state and international capacity. However, while governments and the international community have continued to invest in capabilities and databases for tracking and characterizing the elemental signatures of nuclear material, the question persists as to the ability of nuclear forensics to contribute actionable intelligence in a post-detonation situation quickly enough, as to be useful in the typical time frame for retaliation to terrorist acts.

In the wake of a major terrorist attack resulting in significant casualties, the impetus for a country to respond quickly as a show of strength is critical.3 Because of this, a country is likely to retaliate based on other intelligence sources, as the data from a fully completed forensics characterization would be beyond the time frame necessary for a country’s show of force. To highlight the need for a quick response, a quantitative analysis of responses to major terrorist attacks will be presented in the following pages. This timeline will then be compared to a prospective timeline for forensics intelligence. Fundamentally, this analysis makes it clear that in the wake of a major nuclear terrorist attack, the need to respond quickly will trump the time required to adequately conduct nuclear forensics and characterize the origins of the nuclear material. As there have been no instances of nuclear terrorism, a scenario using chemical, biological, and radiological weapons will be used as a proxy for what would likely occur from a policy perspective in the event a nuclear device is used.

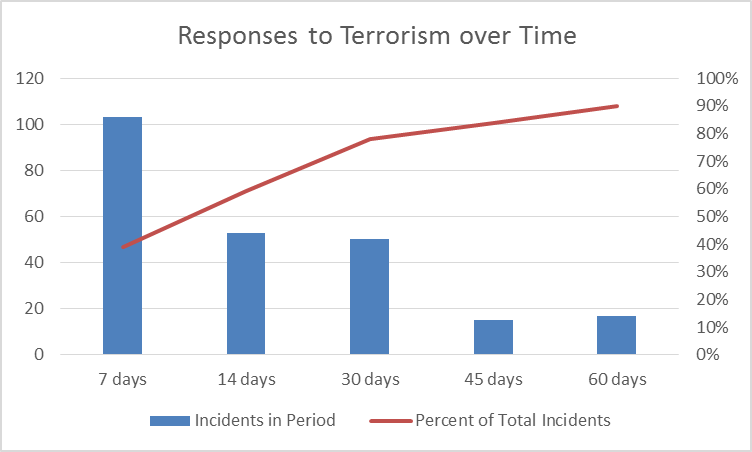

This article will examine existing literature, outline arguments, review technical attributes,4 examine the history of retaliation to terrorism, and discuss conclusions and policy recommendations. This analysis finds that the effective intelligence period for nuclear forensics is not immediate, optimistically producing results in ideal conditions between 21 and 90 days, if at all. The duration of 21 days is also based on pre-detonation conditions, and should be considered very, if not overly, optimistic. Further, empirical data collected and analyzed suggestions that the typical response to conventional terrorism was on average 22 days, with a median of 12 days, while terrorism that used chemical, biological, or radiological materials warranted quicker response – an average of 19 days and a median of 10 days. Policy and technical obstacles would restrict the effectiveness of nuclear forensics to successfully attribute the origin of a nuclear weapon following a terrorist attack before political demands would require assertive responses.

Literature

Discussions of nuclear forensics have increased in recent years. Non-technical scholarship has tended to focus on the ability of these processes to deter the use of nuclear weapons (in particular by terrorists), by eliminating the possibility of anonymity.5 Here, the deterrence framework is an indirect strategy, by which states signal guaranteed retribution for those who support the actions of an attacking nation or non-state actor. This approach requires the ability to provide credible evidence both as to the origin of material and to the political decision to transfer material to a non-state actor. As a result of insufficient data available on the world’s plutonium and uranium supply, as well as the historical record of the transit of material, nuclear forensics may not be able to provide stand-alone intelligence or evidence against a supplying country. However, scholars have largely assumed that the ‘smoking gun’ would be identifiable via nuclear forensics. Michael Miller, for example, argues that attribution would deter both state actors and terrorists from using nuclear weapons as anyone responsible will be identified via nuclear forensics.6 Keir Lieber and Daryl Press have echoed this position by arguing that attribution is fundamentally guaranteed due to the small number of possible suppliers of nuclear material and the high attribution rate for major terrorist attacks.7 There is an important oversight from both a technical and policy perspective in these types of arguments however.

First, the temporal component of nuclear forensics is largely ignored. The processes of forensics do not produce immediate results. While the length of time necessary to provide meaningful intelligence differs, it is unlikely that nuclear forensics will provide information as to the source of the device in the time frame required by policymakers, who in the wake of a terrorist attack will need to respond quickly and decisively. This is likely to decrease both the credibility of forensics information and its usefulness if the political demand requires a leader to act promptly.

Secondly, the existence and size of a black-market for nuclear and radiological material is generally dismissed as a non-factor as it is assumed that a complex weapon provided by a state with nuclear weapon capacity is necessary. While it is acknowledged that a full-scale nuclear device capable of being deployed on a delivery device certainly requires advanced technical capacity that a terrorist organization would likely not have, a very crude weapon is possible. Devices such as a radiological dispersal device or a low yield nuclear device, or even a failed (fizzle) nuclear weapon, would still create a desirable outcome for a terrorist group in that panic, death, and devastating economic and societal consequences would ensue. Further, black market material could the ideal method of weaponization, as its characterization and origin-tracing would prove nearly impossible due to decoupling, and thus confusion, between perpetrator and originator.

It is evident that there is a gap between a robust technical understanding and arguments as to the viability and speed of nuclear forensics in providing actionable intelligence. This gap could lead to unrealistic expectations in times of crisis.

Technical Perspective

This section will outline the technologies, processes, and limitations of forensics in order to better inform its potential for contributing meaningful data in a crisis involving nuclear material. It should be noted that most open-source literature on the processes and capabilities of nuclear forensics come from a pre-detonation position, as specifics on post-denotation procedures and timelines are classified.8 This has resulted in the technical difficulties and inherent uncertainties in the conduct of forensic operations in a post-detonation situation being ignored. The following will attempt to extrapolate the details of the pre-detonation procedures into the post-detonation context in order to posit a potential time frame for intelligence retrieval.

Fundamentally, nuclear forensics is the analysis of nuclear or radiological material for the purposes of documenting the material’s characteristics and process history. With this information, and a database of material to compare the sample to, attribution of the origin of the material is possible.9 Following usage or attempted usage of a nuclear or radiological device, nuclear forensics would examine the known relationships between material characteristics and process history, seeking to correlate characterized material with known production history. While forensics encompasses the processes of analysis on recovered material, nuclear attribution is the process of identifying the source of nuclear or radioactive material, to determine the point of origin and routes of transit involving such material, and ultimately to contribute to the prosecution of those responsible.

Following a nuclear detonation, panic would likely prevail among the general populace and some first responders charged with helping those injured. Those tasked with collecting data from the site for forensic analysis would take time to deploy.10 While National Guard troops are able to respond to aid the population, specialized units are more dispersed throughout the country.11 Nuclear Emergency Support Teams, which would respond in the wake of a nuclear terror attack, are stationed at several of the national laboratories spread around the country. Depending on the location of the attack, response times may vary greatly. The responders’ first step would be to secure the site, as information required for attribution comes from both traditional forensics techniques (pictures, locating material, measurements, etc.) and the elemental forensics analysis of trace particles released from the detonation. At the site, responders would be able to determine almost immediately if it was indeed a full-scale nuclear detonation, a fizzle, or a radiological dispersal device. This is possible by assessing the level of damage and from the levels of radiation present, which can be determined with non-destructive assay techniques and dosimetry. Responders (through the use of gamma ray spectrometry and neutron detection) will be able to classify the type of material used if it is a nuclear device (plutonium versus uranium). With these factors assessed, radiation detectors would need to be deployed to carefully examine the blast site or fallout area to catalogue and extricate radioactive material for analysis. These materials would then need to be delivered to a laboratory capable of handling them.

Once samples arrive at the laboratories, characterization of the material will be undertaken to provide the full elemental analysis (isotopic and phase) of the radioactive material, including major, minor and trace constituents, and a variety of tools that can help classify into bulk analysis, imaging techniques, and microanalysis. Bulk analysis would provide elemental and isotopic composition on the material as a whole, and would enable the identification of trace material that would need to be further analyzed. Imaging tools capture the spatial and textural heterogeneities that are vital to fully characterizing a sample. Finally, microanalysis examines more granularly the individual components of the bulk material.

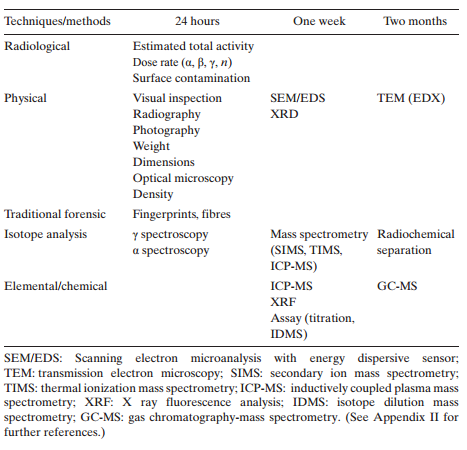

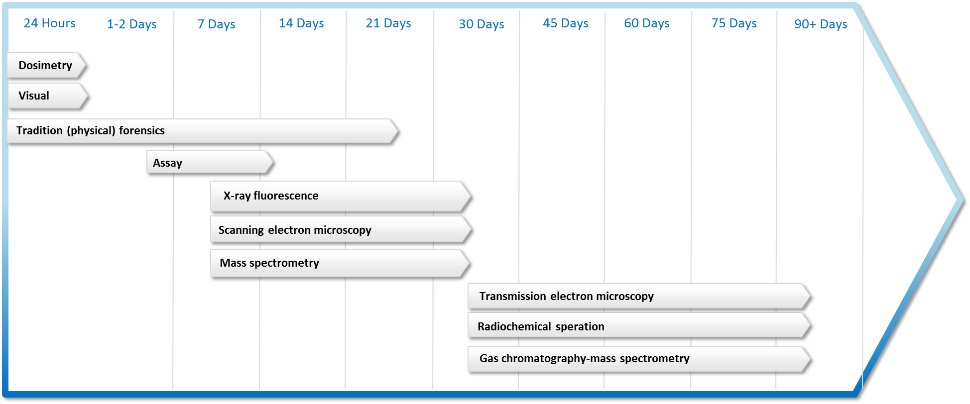

The three-step process described above is critical to assessing the processes the material was exposed to and the origin of the material. The process, the tools used at each stage, and a rough sequencing of events is shown in Figure 1.12 This table, a working document produced by the IAEA, presents techniques and methods that would be used by forensics analysts as they proceed through the three-step process, from batch analysis to microanalysis. Each column represents a time frame in which a tool of nuclear forensics could be utilized by analysts. However, this is a pre-detonation scenario. While it does present a close representation of what would happen post-detonation, some of the techniques listed below would be expected to take longer. This is due to several factors such as the spread of the material, vaporization of key items, and safety requirements for handling radioactive material. These processes take time and deal with small amounts of material at a time which would require a multitude of microanalysis on a variety of elements.

IAEA Suggested Sequence for Laboratory Techniques and Methods

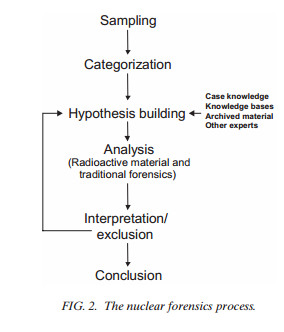

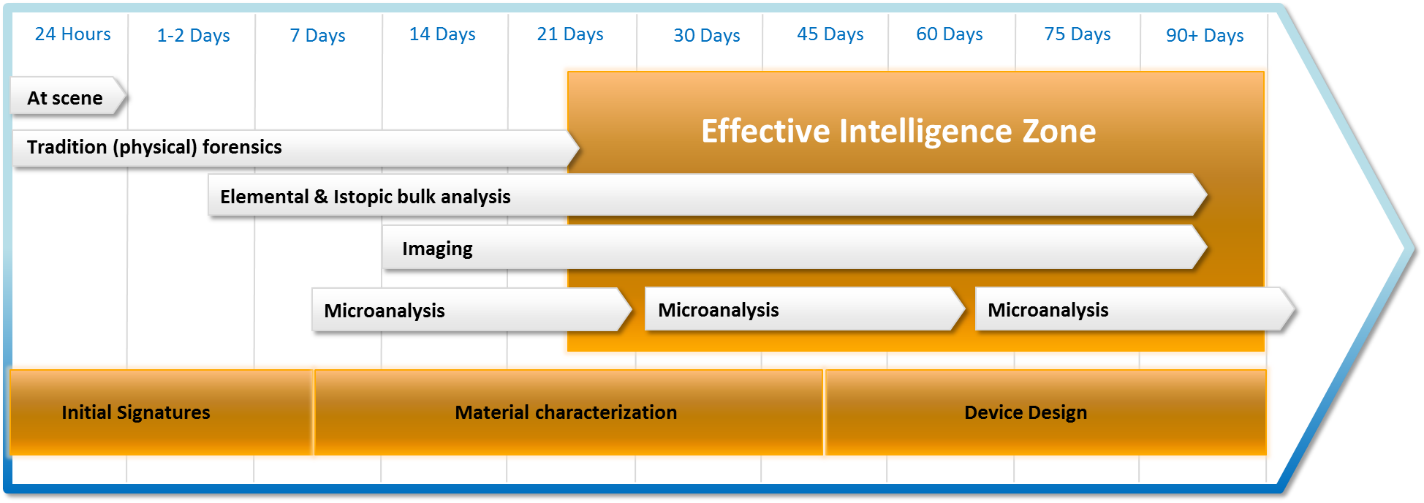

It should also be noted that while nuclear forensics does employ developed best practices, it is not an exact science in that a process can be undertaken and definitive results. Rather, it is an iterative process, by which a deductive method of hypothesis building, testing, and retesting is used to guide analysis and extract conclusions. Analysts build hypotheses based on categorization of material, test these hypotheses against the available forensics data and initiate further investigation, and then interpret the results to include or remove actors from consideration. This can take several iterations. As such, while best practices and proven science drive analysis, the experience and quality of the analyst to develop well-informed hypotheses which can be used to focus more on the investigation is critical to success. A visual representation of the process is seen in Figure 2 below.13

IAEA forensic analysis process

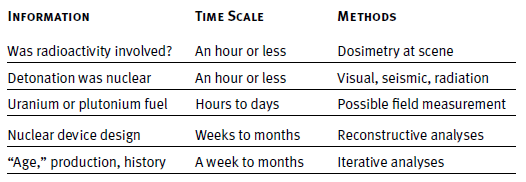

A net assessment by the Joint Working Group of the American Physical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science of the current status of nuclear forensics and the ability to successfully conduct attribution concluded that the technological expertise was progressing steadily, but greater cooperation and integration was necessary between agencies.14 They also provided a simplified timeline of events following a nuclear attack, which is seen in Figure 3.15 Miller also provides a more nuanced breakdown of questions that would arise in a post-detonation situation; however, it is the opinion of the author that his table overstates technical capacity following a detonation and uses optimistic estimates for intelligence.16

Nuclear forensics activities following a detonation

Many of the processes that provide the most insight simply take time to configure, run, and rerun. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, for instance, is able to detect and measure trace organic elements in a bulk sample, a very useful tool in attempting to identify potential origin via varying organics present.17 However, when the material is spread far (mostly vaporized or highly radioactive), it can take time to configure and run successfully. Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) allows for the measuring of multiple isotopes simultaneously, enabling ratios between isotope levels to be assessed.18 While critically important, this process takes time to prepare each sample, requiring purification in either a chemical or acid solution.

With this broad perspective in mind, how long would it take for actionable intelligence to be produced by a nuclear forensics laboratory following the detonation of a nuclear weapon? While Figure 1 puts output being produced in as little as one week, this would be high-level information and able to eliminate possible origins, but most likely not able to come to definitive conclusion. The estimates of Figure 3 (ranging from a week to months), are more likely as the iterative process of hypothesis testing and the obstacles leading up to the point at which the material arrives at the laboratory, would slow and hamper progress. Further, if the signatures of the material are not classified into a comprehensive database, though disperse efforts are underway, the difficulty in conclusively saying it is a particular actor increases.19 As such, an estimate of weeks to months, as is highlighted in Figures 4 and 5, is an appropriate time frame by which actionable intelligence would be available from nuclear forensics. The graphics below show the likely production times for definitive findings by the forensics processes and outlines a zone of effective intelligence production. How does this align with the time frame of retribution?

Nuclear forensics timeline (author-created figure, compiled from above cited IAEA reports and AAAS report}

Effective Intelligence Zone (author-created figure, compiled from above cited IAEA reports and AAAS report.)

Retaliation Data

How quickly do policymakers act in the wake of a terrorist attack? This question is largely unexplored in the social science literature. However, it is critical to establishing a baseline period in which nuclear forensics would likely need to be able to provide actionable intelligence following an attack. As such, an examination of the retaliatory time to major terrorist attacks will be examined to understand the time frame likely available to forensics analysts to contribute conclusions on materials recovered.

Major terrorist attacks were identified using the Study for Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism Global Terrorism Database.20 As such, the database was selected to return events that resulted in either 50 or more fatalities or over 100 injured. Also removed were cases occurring in Afghanistan or Iraq after 2001 and 2003 due to the indistinguishability of responses to terror attacks and normal operations of war within the data. This yielded 269 observations between 1990 and 2004. Cases that had immediate responses (same day) were excluded as this would indicate an ongoing armed conflict. Summary statistics for this data are as follows:

The identified terrorist events were then located in Gary King’s 10 Million Events data set21, which uses a proven data capture and classification method to catalogue events between 1990 and 2004. Government responses following the attack were then captured. Actions were restricted to only those where the government engaged the perpetrating group. This was done by capturing events classified as the following: missile attack, arrest, assassination, unconventional weapons, armed battle, bodily punishment, criminal arrests, human death, declare war, force used, artillery attack, hostage taking, torture, small arms attack, armed actions, suicide bombing, and vehicle bombing. This selection spans the spectrum of policy responses available to a country following a domestic terror attack that would demonstrate strength and resolve. Additionally, by utilizing a range of responses, it is possible to examine terrorism levied from domestic and international sources, thus enabling the consideration of both law enforcement and military actions. Speech acts, sanctions, and other policy actions that do not portray resolve and action were excluded, as they would typically occur within hours of an attack and would not be considered retaliation.

Undertaking this approached yielded retaliation dates for all observations. The summary statistics and basic outline of response time by tier of causalities are as follows:

Table 2: Summary Statistics Table 3: Casualties by Retaliation Quartile

Immediately, questions arise as to the relationship between retaliation time and destruction inflicted, as well as the time frame available to nuclear forensics analysts to provide intelligence before a response is required. With an average retaliation time of 22 days, this would fall within the 1-2 month time frame for complete analysis. Further, a median retaliation time of 12 days would put most laboratory analysis outside the bounds of being able to provide meaningful data. Figure 6 further highlights this by illustrating that within 30 days of a terrorist attack, 80 percent of incidents will have been responded to with force.

Response Time

One of the fundamental graphics presented in the Lieber and Press article shows that as the number of causalities in a terror attack increases, the likelihood of attribution increases correspondingly. This weakens their arguments for two reasons. First, forensics following a conventional attack would have significantly more data available than in the case of a nuclear attack, due to the destructive nature of the attack and the inability of responders to access certain locales. Secondly, a country that is attacked via unconventional means could arguably require a more resolute and quicker response. In looking at the data, the overall time to retaliation is 21.66 days. This number is significantly smaller when limited to unconventional weapons (19.04 days) and smaller still when the perpetrators are not clearly identified (18.8 days). This highlights the need for distinction between unconventional and conventional attacks, which Lieber and Press neglected in their quantitative section.

To further highlight the point that nuclear forensics may not meet the political demands put upon it in a post-detonation situation, Table 4 highlights the disconnect between conventional and unconventional attacks and existing threats. To reiterate, the term unconventional is used colloquially here as a substitute for CBRN weapons, and not unconventional tactics. In only 37 percent of the cases observed was the threat a known entity or attributed after the fact. This compares to 85 percent for conventional. In all of these attacks, retaliation did occur; allowing the conclusion that with the severity of an unconventional weapon and the unordinary fear that is likely to be produced that public outcry and a prompt response would be warranted regardless of attribution.

As the use of a nuclear weapon would result in a large number of deaths, the question as to whether or not higher levels of casualties influence response time is also of importance. However, no significant correlation is present between retaliation time and any of the other variables examined. Here, retaliation time (in days) was compared with binary variables for whether or not the perpetrators were known, if the facility was a government building or not, if the device used was a bomb or not, and if an unconventional device was used or not. Scale variables used include number of fatalities, injured, and the total casualties from the attack. Of particular note here is the negative correlation between unconventional attacks and effective attribution at time of response; this reemphasizes the above point on attribution prior to retaliation as being unnecessary following an unconventional attack.

Assessment

From this review, the ability of nuclear forensics to provide rapid, actionable intelligence in unlikely. While it is acknowledged that the process would produce gains along the way, an effective zone of intelligence production can be assumed between 21-90 days optimistically. This is highlighted in Figure 5 above, which aligns the effective zone with the processes that would likely provide definitive details. However, this does not align with the average (22 days) and median (12 days) time of response for conventional attacks. More importantly, unconventional attack responses fall well before this effective zone, with an average of 19 days and a median of 10. While the effective intelligence zone is close to these averages of these data points, the author remains skeptical that the techniques to be performed would produce viable data in a shorter time frame presented given the likely condition of the site and the length of time necessary for each run of each technique.22 This woasuld seem to support an argument that the working timelines for actionable data being outside the boundary of average retaliatory time. More examination is necessary to further narrow down the process times, a task plagued with difficulties due to material classification.ass

A secondary argument that can be made when thinking about unattributed terror attacks is that even without complete attribution, a state will retaliate against a known terror, cult, or insurgent organization following a terror attack to show strength and deter further attacks. This was shown to be the case in 34 of 54 observations (63 percent unattributed). While this number is remarkably high, all states were observed taking decisive action against a group. This would tend to negate the perspective that forensics will matter following an attack, as a state will respond more decisively to unconventional attacks than conventional whether attribution has been established or not.

There are also strategic implications for indirect deterrent strategies as well. Indirect deterrence offers a bit more flexibility in the timing of results, but less so in the uncertainty of results, as it will critical in levying guilty claims against a third-party actor. Thus, nuclear forensics can be very useful, and perhaps even necessary, in indirect deterrent strategies if data is available to compare materials and a state is patient in waiting for the results; however, significant delays in intelligence or uncertainty in results may reduce the credibility of accusations and harm claims of guilt in the international context. From a strategic perspective, the emphasis in the United States policy regarding rapid identification that was discussed at the outset of the paper reflects optimism rather than reality.

Policy Recommendations

While nuclear forensics may not be able to contribute information quickly enough to guide policymakers in their retaliatory decision-making following terrorist attacks, nuclear forensics does have significant merit. Nuclear forensics will be able to rule people out. It will be able to guide decisions for addressing the environmental disaster. Forensics also has significant political importance, as it can be used in a post-hoc situation following retaliation to possibly justify any action taken. It will also continue to be important in pre-detonation interdiction situations, where it has been advanced and excelled to-date, providing valuable information on the trafficking of illicit materials.

However, realistic expectations are necessary and should be made known so that policymakers are able to plan accordingly. The public will demand quick action, requiring officials to produce tangible results. If delay is not possible, attribution may not be possible. To overcome this, ensuring policymakers are aware of the technical limitations and hurdles that are present in conducting forensics analysis of radioactive material would help to manage expectations.

To reduce analytical time and improve attribution success rates, further steps should be taken. Continuing to enlarge the IAEA database on nuclear material signatures is critical, as this will reduce analytical time and uncertainty, making more precise attribution possible. Additional resources for equipment, building up analytical capacity, and furthering cooperation among all states to ensure that signatures are catalogued and accessible is critical. The United States has taken great steps in improving the knowledge base on how nuclear forensics is conducted with fellowships and trainings available through the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). While funding constraints are tight, expansion of these programs and targeted recruitment of highly-qualified students and individuals is key. Perhaps, these trainings and opportunities could be expanded to cover individuals that are trained to do analytical work, but is not their primary tasking – like a National Guard for nuclear forensics. DOE and other agencies have similar programs for response capacity during emergencies; bolstering analytical capacity for rapid ramp-up in case of emergency would help to reduce analytical time. However, while these programs may reduce time, some of the delay is inherent in the science. Technological advances in analytics may help, but in the short-term are unavailable. In sum, further work in developing the personnel and technological infrastructure for nuclear forensics is needed; in the meantime, prudence is necessary.

Philip Baxter is currently a PhD Candidate in the International Affairs, Science, and Technology program in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at Georgia Tech. He completed his BA in political science and history at Grove City College and a MA in public policy, focusing on national security policy, from George Mason University. Prior to joining the Sam Nunn School, Phil worked in international security related positions in the Washington, DC area, including serving as a researcher at the National Defense University and as a Nonproliferation Fellow at the National Nuclear Security Administration. His dissertation takes a network analysis approach in examining how scientific cooperation and tacit knowledge development impacts proliferation latency. More broadly, his research interests focus on international security issues, including deterrence theory, strategic stability, illicit trafficking, U.S.-China-Russia relations, and nuclear safeguards.

Nuclear Information Project: External Publications and Briefings

This chronology lists selected external publications and briefings by the staff of the Nuclear Information Project. External links might go dead over time; if you need assistance to locate missing items, please contact individual project staff via the “About” page. To search for publications on the FAS Strategic Security Blog, see our Publications page.

2023

- “Strategic Arms Control after the New START Treaty”, Presentation to the Princeton Program on Science and Global Security, April 12, 2023.

- “Chinese nuclear weapons, 2023,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 2023.

- “Nuclear Weapons Ban Monitor 2022,” March 2023.