Alternatives to the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent

This policy memo suggests that the Biden administration should immediately launch a National Security Council-led strategic review examining the role of ICBMs in US nuclear strategy, and presents four alternative policy options that the Biden administration could pursue in lieu of the current GBSD program of record.

Download the report here.

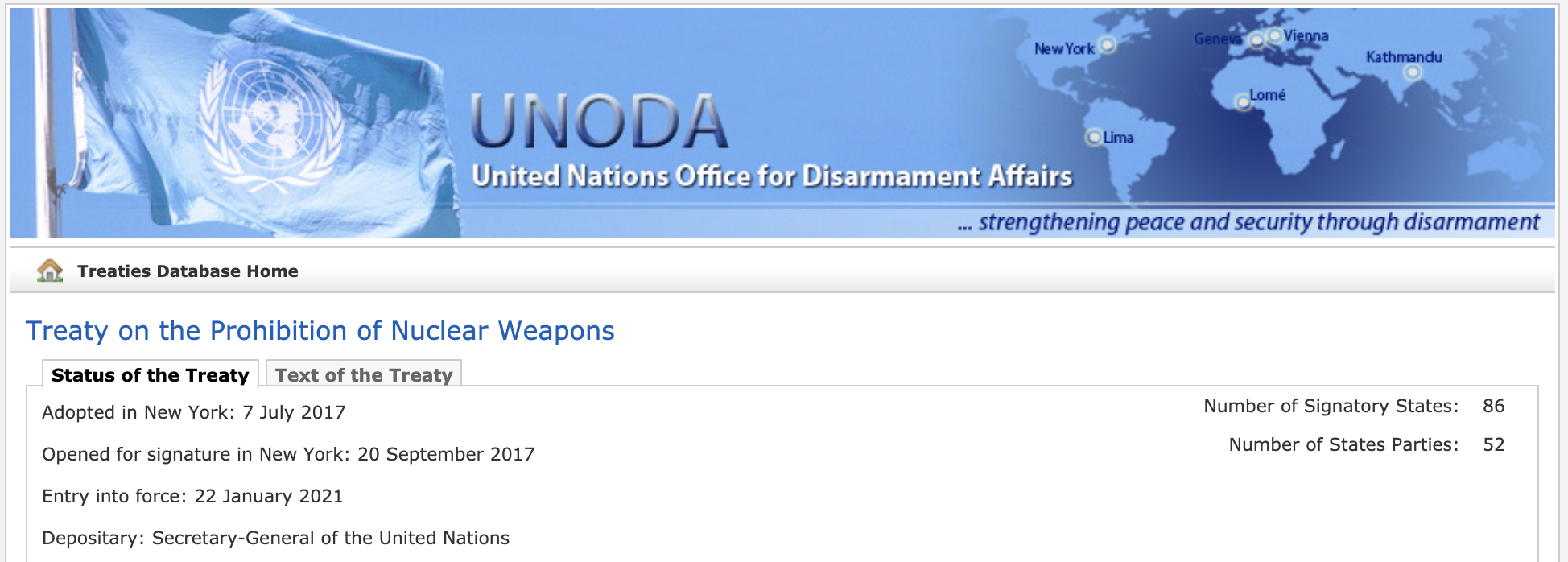

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Enters Into Force Today

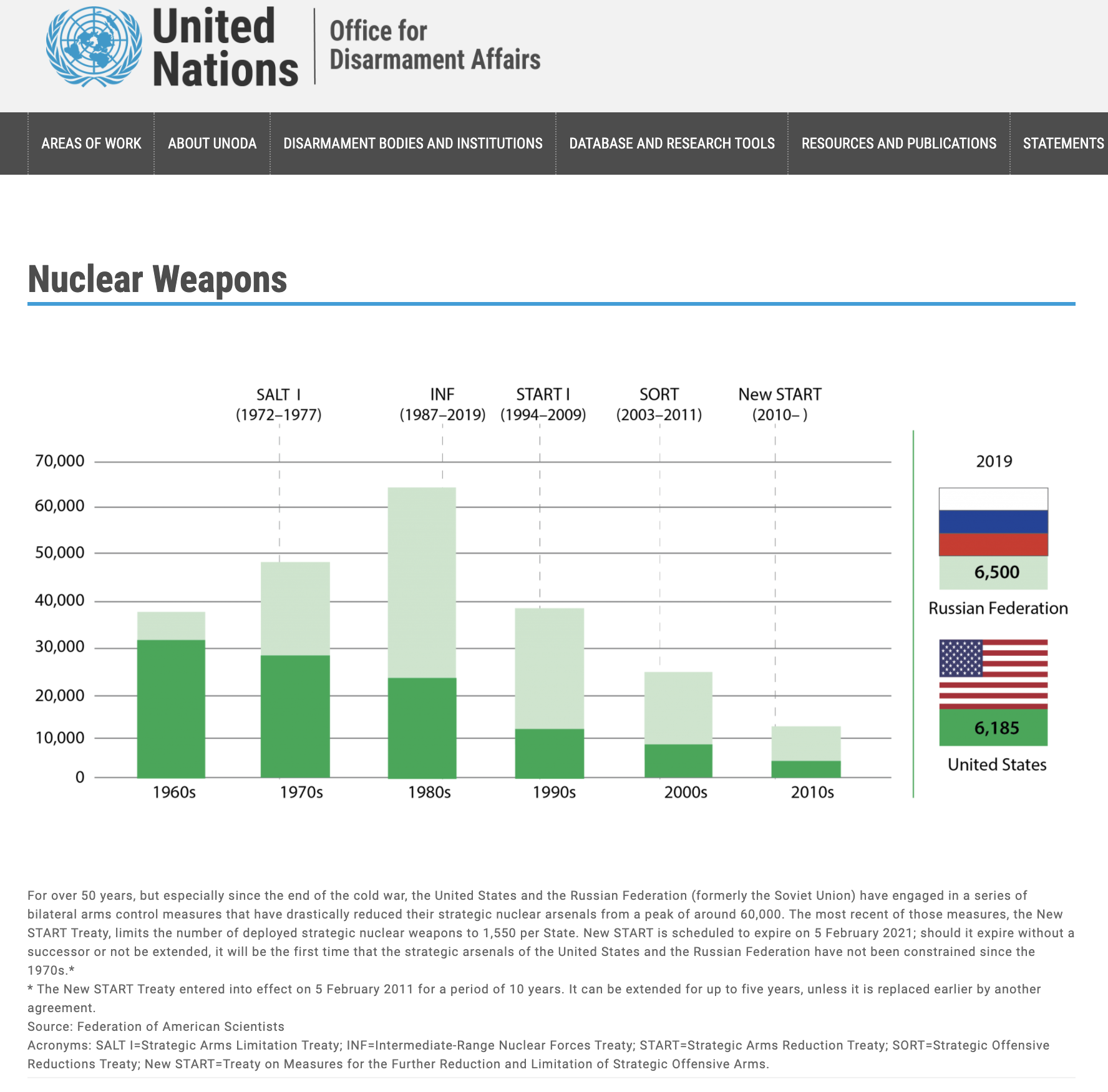

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) enters into force today, 90 days after the deposit of the 50th instrument of ratification. So far, a total of 86 countries have signed the treaty, which complements existing disarmament measures like the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

The TPNW is a significant milestone in the long and global effort to achieve a world free from nuclear weapons. The 86 countries that have signed so far are also signatories to the NPT––which also calls for nuclear disarmament––but signed on to the TPNW in apparent frustration over what they consider inadequate progress by the nuclear-armed states in fulfilling their NPT obligations. As we wrote in July 2020, on the 75th anniversary of the Trinity Nuclear Test:

Nuclear-armed states largely do not appear to consider nuclear disarmament to be an urgent global security, humanitarian, or environmental imperative. Instead, most states seem to consider disarmament as a type of chore mandated by the Non-Proliferation Treaty – and not one that they are seriously interested in completing in the foreseeable future.

It is increasingly rare to hear any officials from nuclear weapon states express a coherent rationale for pursuing disarmament other than as a result of the obligation to do so under the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Moreover, they seem increasingly focused on shifting the disarmament responsibility onto the non-nuclear states by arguing they first must create the security conditions that will make nuclear disarmament possible.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons seeks to turn this reality on its head. Rather than listening to another half-century of excuses from the nuclear-armed states that they can’t disarm, the countries behind the TPNW seek to take the initiative and increase pressure on the nuclear-armed states to adopt disarmament measures.

Unfortunately, no matter how many countries sign it, the TPNW does not eliminate any nuclear weapons unless the nuclear-armed states join and implement the treaty’s provisions. They are not legally bound by the prohibition unless they sign the treaty. So far, they have refused, boycotted meetings, and even pressured countries not to sign on. Rather than a ban, they argue that “an incremental, step-by-step approach is the only practical option for making progress towards nuclear disarmament…”

However, decades of trying that approach has left the world with more than 13,000 nuclear weapons, led to a slowed pace of reductions, increasing modernization programs––and in some cases, increasing nuclear arsenals, worsening military tensions, reaffirmations of the enduring role and importance of nuclear weapons, and the discarding of arms control agreements. Non-nuclear armed states would seem justified in wanting to try something new.

FAS is honored that the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs uses our nuclear weapons estimates. For latest updates, go here.

Whether or not one believes the TPNW is the right approach, the Treaty is a reality and now in force. More NPT countries are likely to join. While the Treaty may not immediately create disarmament, it is supported by a significant number of the states party to the NPT. Additionally, the TPNW includes welcome and unprecedented provisions on humanitarian assistance and environmental remediation, which offer a bridge to nuclear-armed states and their allies by allowing them to engage with these provisions without immediately signing the treaty.

Now that the Treaty is in force, instead of continuing to boycott and reject their efforts and motivations of its supporters, the nuclear-armed states must work with them to achieve responsible reductions of nuclear forces and create the conditions that would allow them to be eliminated.

Background Information:

• UN: Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

• FAS: Status of World Nuclear Forces

The Federation of American Scientists is honored to provide the world with the best non-classified estimates of the nuclear weapons arsenals. We are grateful for the financial support from the New Land Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation to do this work. To explore this vast data, developed over many decades, start here.

New NASIC Report Appears Watered Down And Out Of Date

The US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published a new version of its widely referenced Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report.

The agency normally puts out an updated version of the report every four years. The previous version dates from 2017.

The 2021 report (dated 2020) provides information on developments in many countries but is clearly focused on China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. Especially the North Korean data is updated because of the significant developments since 2017.

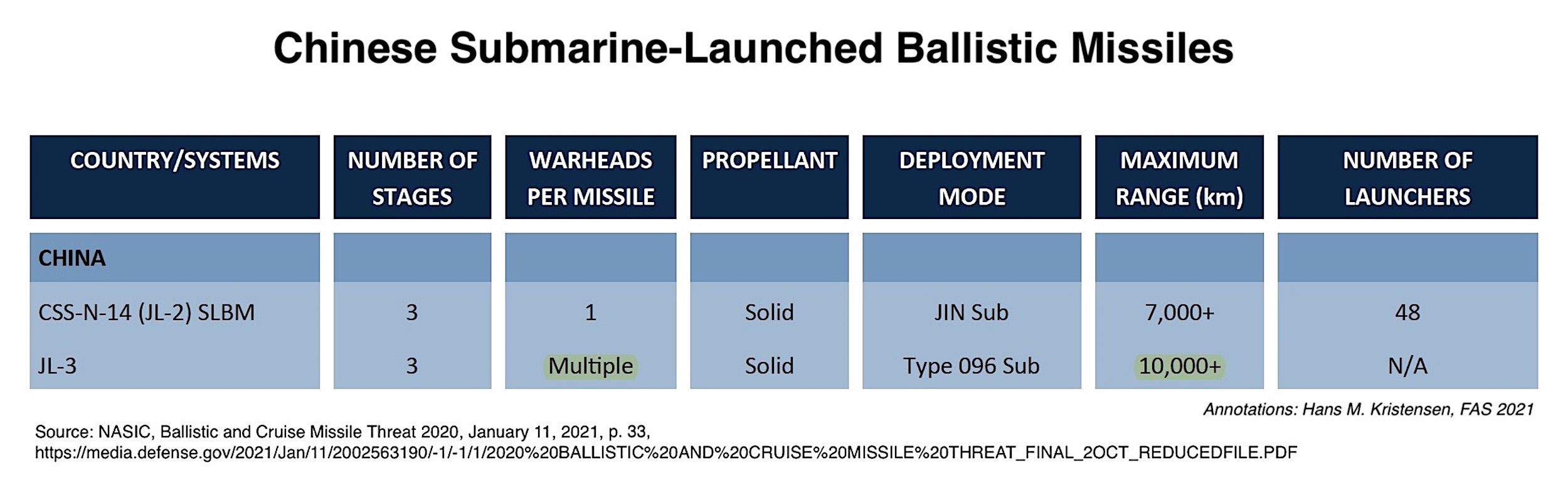

The most interesting new information in the updated report is probably that the new Chinese JL-3 sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is capable of carrying multiple warheads.

Overall, however, the new report may be equally interesting because of what it does not include. There are a number of cases where the report is scaled back compared with previous versions. And throughout the report, much of the data clearly hasn’t been updated since 2018. In some places it is even inconsistent and self-contradicting.

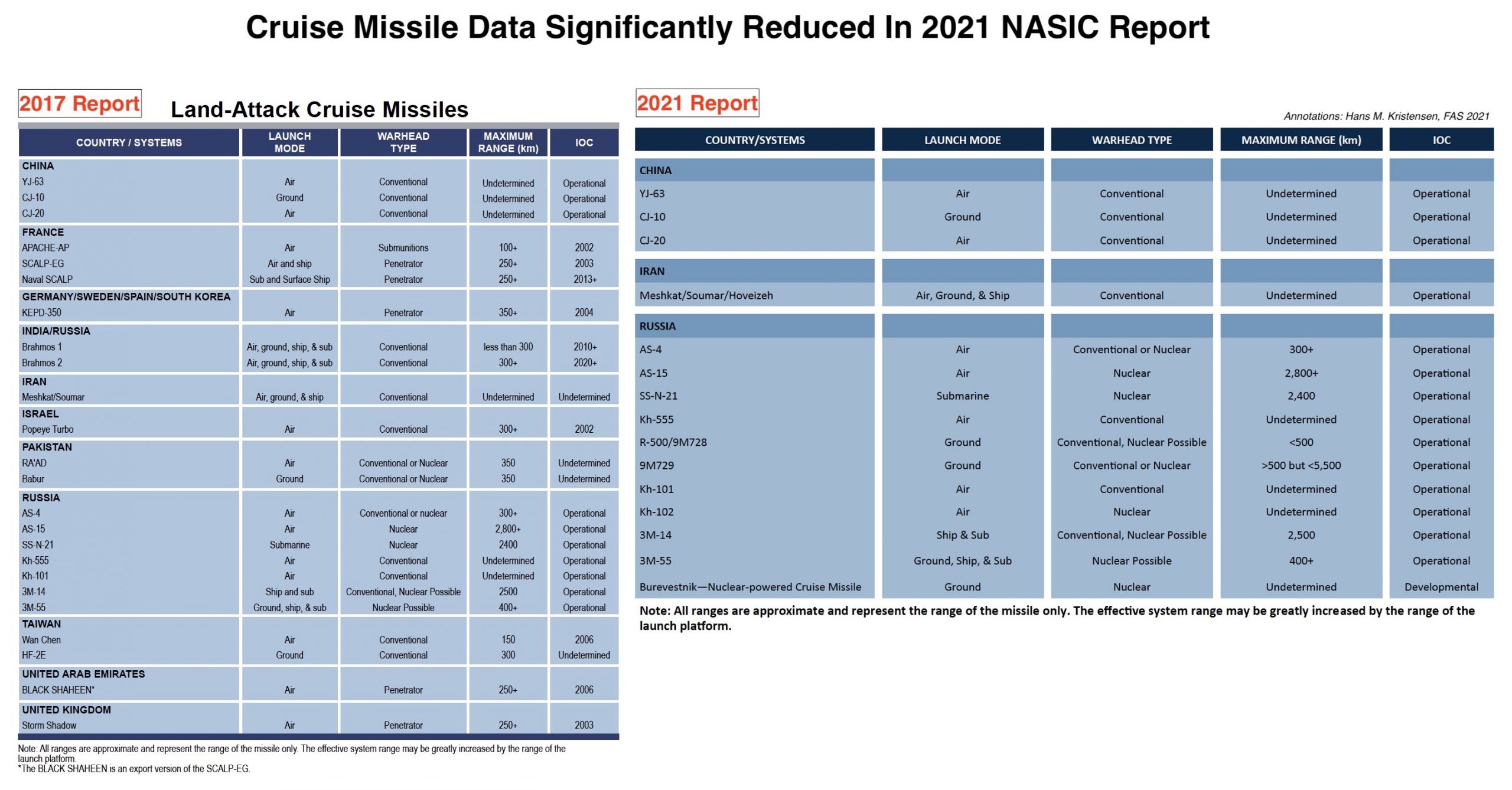

The most significant data reduction is in the cruise missile section where the report no longer lists countries other than Russia, China, and Iran. This is a significant change from previous reports that listed a wide range of other countries, including India and Pakistan and many others that have important cruise missile programs in development. The omission is curious because the report in all ballistic missile categories includes other countries.

Cruise missile data is significantly reduced in the new NASIC report compared with the previous version from 2017. Click on image to view full size.

Other examples of reduced data include the overview of ballistic missile launches, which for some reason does not show data for 2019 and 2020. Nor is it clear from the table which countries are included.

Also, in some descriptions of missile program developments the report appears to be out of date and not update on recent developments. This includes the Russian SS-X-28 (RS-26 Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM, which the report portrays as an active program but only presents data for 2018. Likewise, the report does not mention the two additional boats being added to the Chinese SSBN fleet. Moreover, the new section with air-launched ballistic missiles only includes Russia but leaves out Chinese developments and only appears to include data up through early 2018.

Whether these omissions reflect changes in classification rules, chaos is the Intelligence Community under the Trump administration, or simply oversight is unknown.

Below follows highlights of some of the main nuclear issues in the new report.

Russian Nuclear Forces

Information about Russian ballistic and cruise missile programs dominate the report, but less so than in previous versions. NASIC says Russia currently has approximately 1,400 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, a reduction from the “over 1,500” reported in 2017. The new number is well known from the release of New START data and is very close to the 1,420 warheads we estimated in our Russian Nuclear Notebook last year.

NASIC repeats the projection from 2017, that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints….”

The statement that “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs” is curious, however, because would imply the SLBM force is loaded with fewer warheads than normally assumed. The warhead loading attributed to the SS-N-32 (Bulava) is 6, the number declared by Russia under the START treaty, and less than the 10 warheads that is often claimed by unofficial sources.

The new version describes continued development of the SS-28 (RS-26 (Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM suspected by some to actually be an IRBM. But the report only lists development activities up through 2018 and nothing since. The system is widely thought to have been mothballed due to budget constraints.

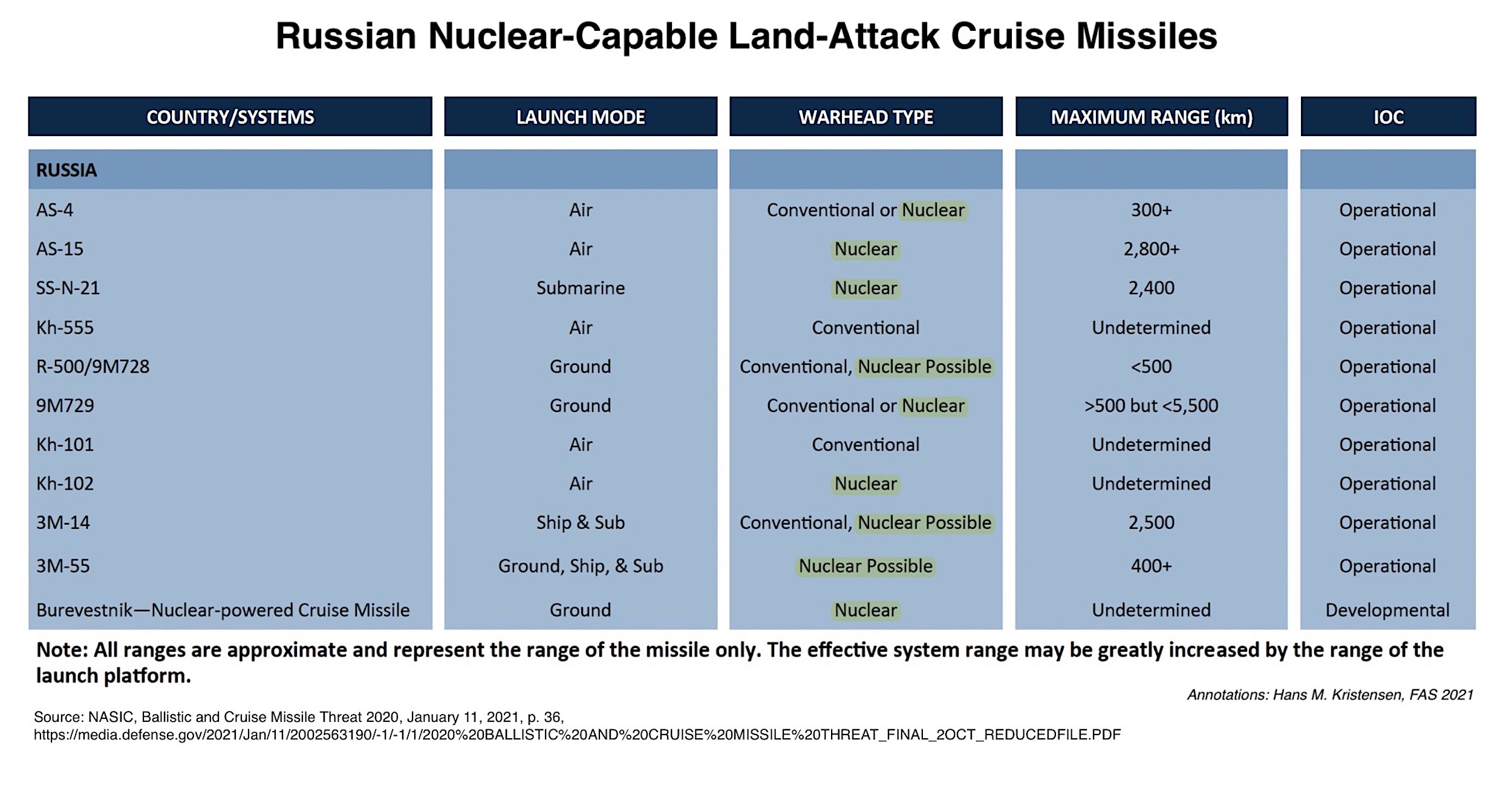

The cruise missile section attributes nuclear capability – or possible nuclear capability – to most of the Russian missiles listed. Six systems are positively identified as nuclear, including the Kh-102, which was not listed in the 2017 report. Two of the nuclear systems are dual-capable, including the 9M729 (SSC-8) missile the US said violated the now-abandoned INF treaty, while 3 missiles are listed as “Conventional, Nuclear Possible.” That includes the 9M728 (R-500) cruise missile (SSC-7) launched by the Iskander system, the 3M-14 (Kalibr) cruise missile (SS-N-30), and the 3M-55 (Yakhont, P-800) cruise missile (SS-N-26).

NASIC attributes nuclear capability to nine Russian land-attack cruise missiles, three of them “possible.” Click on image to view full size.

The designation of “nuclear possible” for the SS-N-30 (3M-14, often called the Kalibr even though Kalibr is strictly speaking the name of the launcher system) is curious because the Russian government has clearly stated that the missile is nuclear-capable.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

The biggest news in the China section of the NASIC report is that the new JL-3 SLBM that will arm the next-generation Type 096 SSBN will be capable of delivering “multiple” warheads and have a range of more than 10,000 kilometers. That is a significant increase in capability compared with the JL-2 SLBM currently deployed on the Jin-class SSBNs and is likely part of the reason for the projection that China’s nuclear stockpile might double over the next decade.

NASIC reports that China’s next-generation JL-3 SLBM will be capable of carrying “multiple” warheads. Click on image to view full size.

Despite this increased range, however, a Type 096 operating from the current SSBN base in the South China Sea would not be able to strike targets in the continental United States. To be able to reach targets in the continental United States, an SSBN would have to launch its missile from the Bohai Sea. That would bring almost one-third of the continental United States within range. To target Washington, DC, however, a Type 096 SSBN would still have to deploy deep into the Pacific.

The new DF-41 (CSS-20) has lost its “-X-“ designation (CSS-X-20), which indicates that NASIC considers the missile has finished development is now being deployed. A total of 16+ launchers are listed, probably based on the number attending the 2019 parade in Beijing and the number seen operating in the Jilantai training area.

The number of DF-31A and DF-31AG launchers is very low, 15+ and 16+ respectively, which is strange given the number of bases observed with the launchers. Of course, “+” can mean anything and we estimate the number of launchers is probably twice that number. Also interesting is that the DF-31AG is listed as “UNK” (unknown) for warheads per missile. The DF-31A is listed with one warhead, which suggests that the AG version potentially could have a different payload. Nowhere else is the AG payload listed as different or even multiple warheads.

The NASIC report projection for the increase in Chinese nuclear ICBM warheads that can reach the United States is inconsistent and self-contradicting. In one section (p. 3) the report predicts “the number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States potentially expanding to well over 200 within the next 5 years.” But in another section (p. 27), the report states that the “number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 5 years.” The projection of “well over 100” was also listed in the 2017 report, and the “well over 200” projection matches the projection made in the DOD annual report on Chinese military developments. So the authors of the NASIC might simply have forgotten to update the text.

On Chinese shorter-range ballistic missiles, the NASIC report only mentions DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2) as nuclear, but not the CSS-5 Mod 6 version. The Mod 6 version (potentially called DF-21E) was first mentioned in the 2016 DOD report on Chinese military developments and has been included since.

Newer missiles finally get designations: The dual-capable DF-26 is called the CSS-18, and the conventional (possibly) DF-17 is called the CSS-22. NASIC continues to list the DF-26 range as less (3,000+ km) than the annual DOD China report (4,000 km).

An in case anyone was tempted, no, none of China’s cruise missiles are listed as nuclear-capable.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

The report provides no new information about Pakistani nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. As with several other sections in the report, the information does not appear to have been updated much beyond 2018, if at all. As such, status information should be read with caution.

The Shaheen-III MRBM is still not deployed, nor is the Ababeel MRBM that NASIC describes as a “MIRV version.” It has only been flight-tested once.

The tactical nuclear-capable NASR is listed with a range of 60 km, the same as in 2017, even though the Pakistani government has since claimed the range has been extended to 70 km.

Because the new NASIC report no longer includes data on Pakistan’s cruise missiles, neither the Babur nor the RAAD programs are described. Nor is any information provided about the efforts by the Pakistani navy to develop a submarine-launched nuclear-capable cruise missile.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Similar to other sections of the report, the data on Indian programs are tainted by the fact that some information does not appear to have been updated since 2018, and that the cruise missile section does not include India at all.

According to the report, Agni II and Agni III MRBMs are still deployed in very low numbers, fewer than 10 launchers, the same number reported in 2017. That number implies only a single brigade of each missile. But, again, it is not clear this information has actually been updated.

Nor are the Agni IV or the Agni V listed as deployed yet.

North Korean Forces

The North Korean sections are main interesting because of the inclusion of data on several systems test-launched since the previous report in 2017. This contrasts several other data set in the report, which do not appear to have been updated past 2018. But since the North Korean long-range tests occurred in 2017, this may explain why they are included.

NASIC provides official (unclassified) range estimates for these missiles:

The Hwasong-12 IRBM range has been increased from 3,000+ km in 2017 to 4,500+ km in the new report.

On the ICBMs, the Taepo Dong 2 no longer has a range estimate. The Hwasong-13 and Hwasong-14 range estimates have been raised from the generic 5,500+ km in the 2017 report to 12,000 km and 10,000+ km, respectively, in the new report, and the new Hwasong-15 has been added with a range estimate of 12,000+ km. The warhead loading estimates for the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15 are “unknown” and none of the ICBMs are listed as deployed.

On submarine-launched missiles, the NASIC report lists two: the Puguksong-1 and Pukguksong-3. Both have range estimates of 1,000+ km and the warhead estimate for the Pukguksong-3 is unknown (“UNK”). Neither is deployed. The new Pukguksong-4 paraded in October 2020 is not listed, not is the newest Pukguksong-5 displayed in early 2021 mentioned.

Additional background information:

• Russian nuclear forces, 2020

Public Perspectives on the US Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force

This report features the results of an October 2020 poll on US nuclear policy conducted by ReThink Media on behalf of the Federation of American Scientists.

Download the report here. View the polling as a webpage here.

An Integrated Approach to Deterrence Posture

The primary deterrence challenge facing the United States today is preventing aggression and escalation in limited conventional conflicts with a nuclear-armed adversary. It is a difficult conceptual and practical challenge for both conventional and nuclear strategy—but existing Pentagon strategy development processes are not equipped to integrate these tools to meet the challenge.

At the conceptual level, two strategy documents guide U.S. deterrence policy. The 2018 National Defense Strategy (NDS) described how multiple layers of conventional forces can help to deter aggression by nuclear-armed adversaries while the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) proposed new nonstrategic nuclear options to enhance deterrence of aggression and nuclear use. The two documents each present a strategy for deterring nuclear-armed adversaries in regional conflicts and serve as valuable public diplomacy tools to explain U.S. strategic thinking and intentions to allies and partners, potential adversaries, the public, and Congress.

However, it is not clear how the strategies described in the NDS and the NPR relate to each other. What is the respective role of nuclear and conventional weapons in managing escalation in a limited conflict? How can conventional weapons deter and respond to an adversary’s limited nuclear employment? As nuclear forces consume an increasing proportion of Pentagon procurement budgets, how should the services balance competing nuclear and conventional priorities? While these questions of national policy go unanswered, commands are also struggling with a number of practical challenges with operating conventional forces under the shadow of nuclear escalation. Are combatant commands prepared to conduct nuclear signaling and employment operations during a limited conventional conflict, given complex logistical and strategic challenges? How can conventional forces operate effectively in an environment that may be degraded by nuclear use?

NNSA Nuclear Plan Shows More Weapons, Increasing Costs, Less Transparency

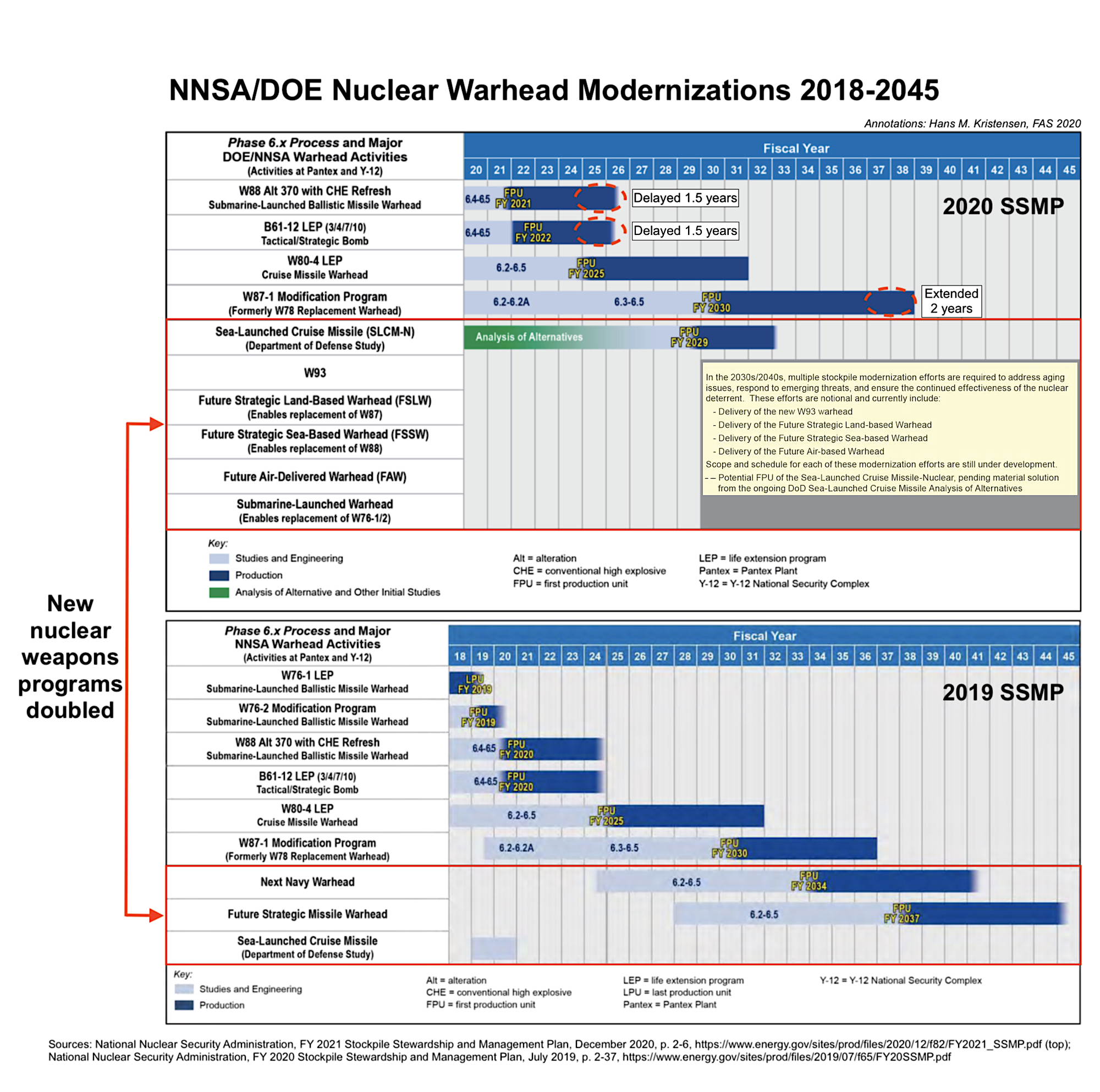

The National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA’s) new Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) doubles the number of new nuclear warhead programs compared with the previous plan from 2019. The plan shows nuclear weapons advocates taking full advantage of the Trump administration to boost nuclear weapon programs.

The new plan also shows significantly increasing nuclear weapons costs projected for the next two decades. These additional costs reflect the steadily growing ambitions of the nuclear modernization programs in response to the embrace of the Great Power Competition strategy articulated in the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy and Nuclear Posture Review.

Moreover, the 2020 SSMP significantly reduces the information available to the public about NNSA’s nuclear weapons activities by cutting by nearly half the size of the public version of the plan and omitting information that used to be included in previous SSMP reports.

More Nuclear Weapons

The new NNSA report doubles the number of new nuclear weapons modernization programs compared with the previous SSMP plan from 2019. This includes the recently reported W93 navy warhead, a new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile, and two future warheads that appear to be derived from what was previously called the Reliable Replacement Warheads. “In addition to these warheads,” the SSMP states, “a replacement air-delivered warhead and submarine-launched warhead (for the W76-1/2) will be needed in the 2040s.” Some of these future warheads were indicated in the DOD’s Nuclear Matters Handbook, which was published earlier this year.

The 2020 NNSA plan lists twice as many new nuclear weapons as the previous plan from 2019. Click on figure to view full size.

The navy gets four of the six new warheads. The first of these is the new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) advocated by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. Congress has funded a study for this weapon and NNSA plans to begin production in 2029, but it remains to be seen if the new Biden administration will continue it. If so, the missile might be equipped with a modified W80 cruise missile warhead (perhaps a W80-5 modification) for deployment on Virginia-class attack submarines.

The second navy warhead is the W93, which was announced by NNSA in February. Importantly, the W93 is not listed as a replacement for the W76 or W88 warheads, which are listed to be replaced by two other warheads, but as a supplement. This fits the description in the navy’s talking points on the new warhead.

The third navy warhead is the Submarine Launched Warhead (SLW) slated to replace the W76-1 and W76-2. This indicates that the SLW might have flexible yield settings to cover both the medium/high-yield mission of the W76-1 and the low-yield mission of the W76-2, or that they will produce two yield versions of it, or that the W76-2 mission will simply fall away.

The fourth navy warhead is the Future Strategic Sea-Based Warhead (FSSW), which is listed as a replacement of the W88, the highest-yield ballistic missile warhead, which is currently being life-extended under the Alt 370 program.

Four of the six new nuclear weapon programs listed in the new NNSA plan are for the US Navy. (Image: US Navy)

The ICBM force gets one new warhead – known as Future Strategic Land-Based Warhead (FSLW) – to replace the W87. It is unclear from the SSMP if the if the new warhead is intended to replace both versions of the W87 or only the W87-0. The W87-1 will still have a lot of life left in it in the 2040s, so it probably initially means replacing the W87-0. If it replaces both, then the ICBM force would go to a single warhead instead of the two currently arming it.

The bombers get a new weapon, known as the Future Air-Delivered Warhead (FAW). The weapon was previously known as the B61-13. The weapon is a follow-on to the B61-12, which will begin rolling off the projection line in late-2021.

The new warhead focus appears to continue the trend to somewhat break with the post-Cold War approach by moving away from simple life-extension of existing warheads to instead produce weapons based on significantly modified or even new designs with new military capabilities. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review removed restrictions in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review on new warheads with new military capabilities. Instead, the 2020 SSMP more overtly justifies new requirement to be able to quickly design and produce new nuclear weapons with “enhanced military capabilities” and “responding to increased threats” in a Great Power Competition context.

The W93, for example, will “address the changing strategic environment” and “improve…flexibility to address future threats,” according to the SSMP. And the new future ballistic missile warheads will “support threats anticipated in 2030 and beyond.” Likewise, part of the justification to increase warhead pit production capacity to at least 80 pits per year is “Renewed competition among global powers that may lead to changes in deterrent requirements.”

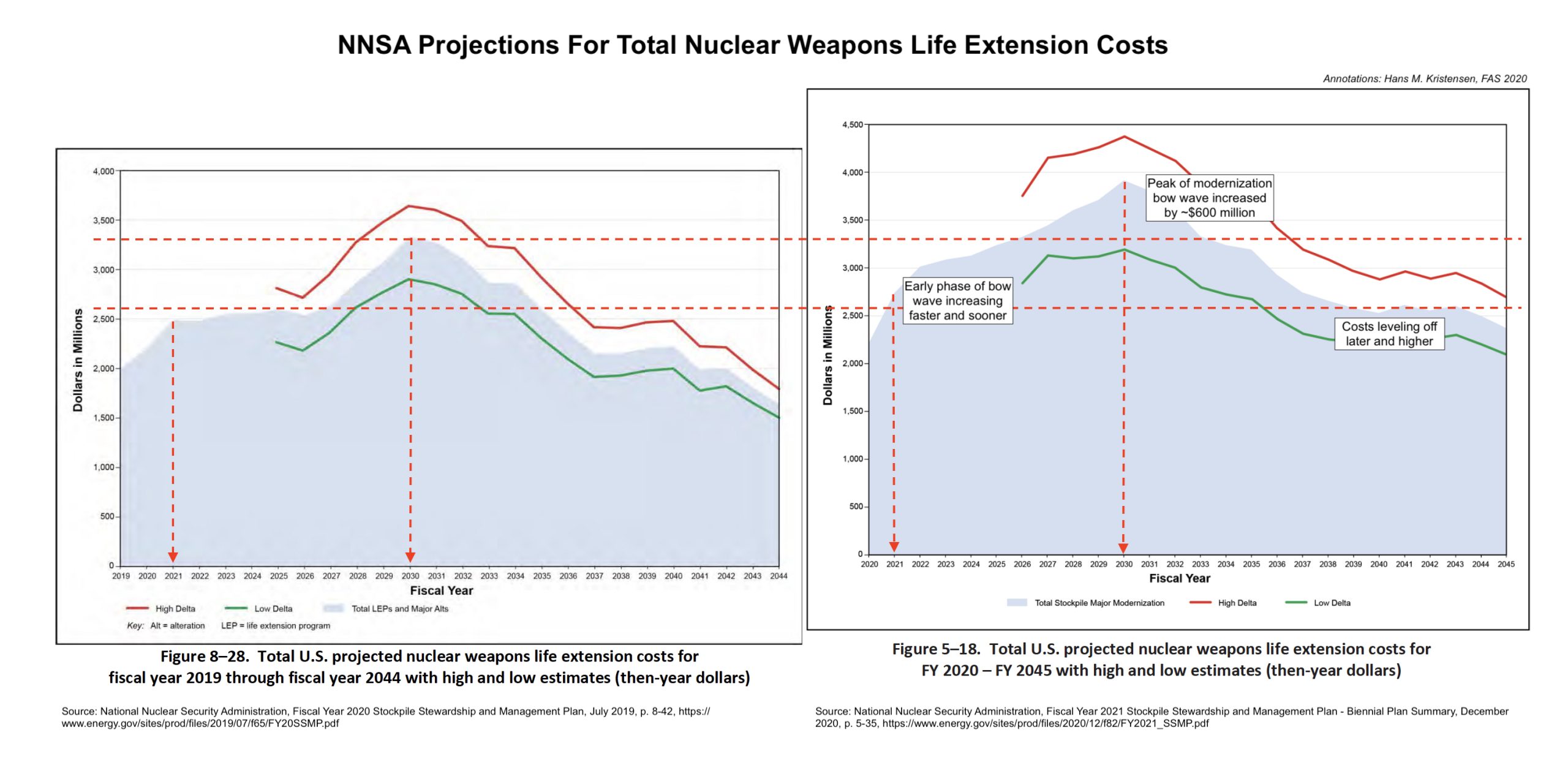

Growing Costs

Underpinning all of these nuclear weapons maintenance and modernization plans is a sprawling nuclear weapons complex that is scheduled to increase significantly with new bomb-making factories and support facilities. This includes boosting the warhead pit production capacity at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and adding a second pit production factory at the Savannah River Site to produce no fewer than 80 new pits per year by 2030. The new pits will feed the W87-1 production and the new future warheads.

The NNSA budget began to increase during the Obama administration and the Trump administration has increased it significantly since and is proposing an additional increase of 19 percent in the FY2021 budget.

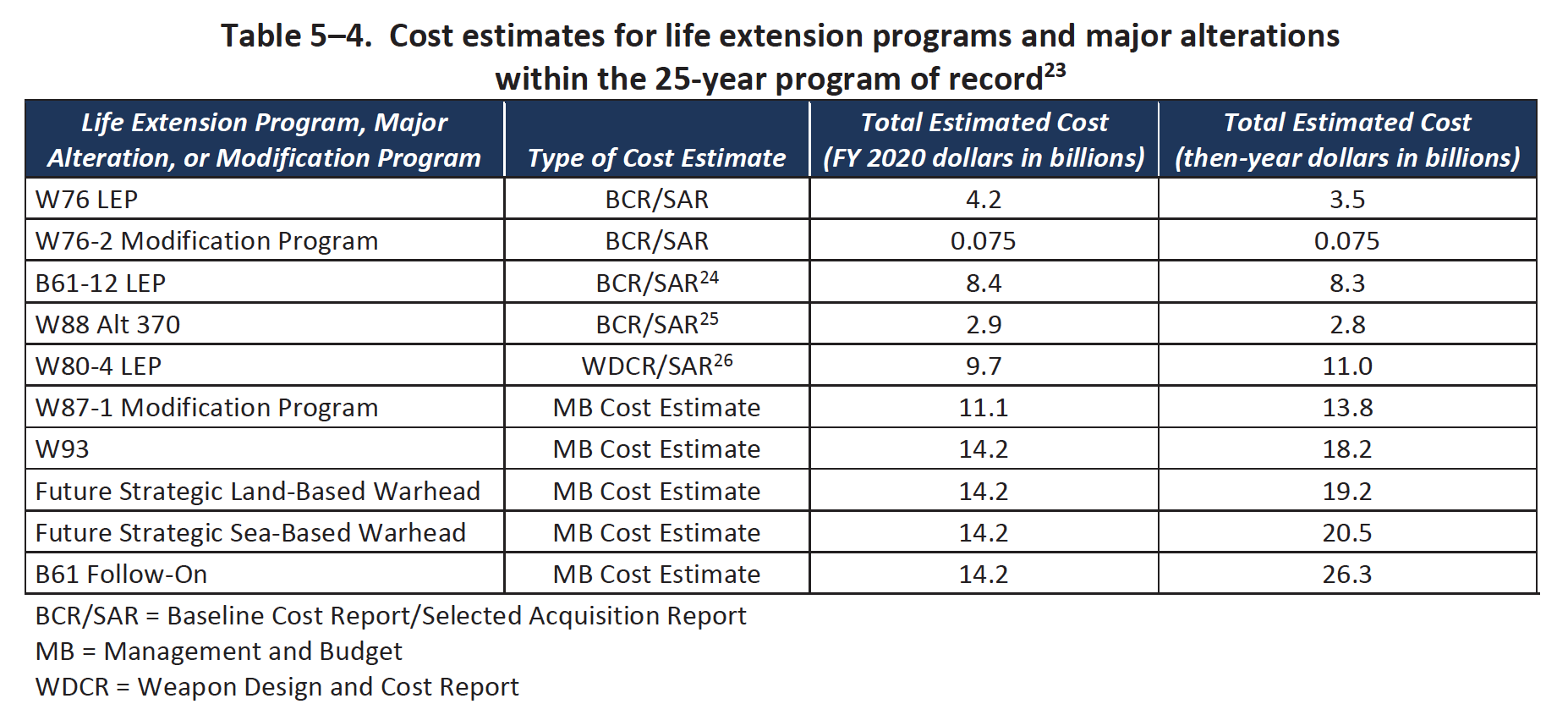

The trend is that warhead modernization programs are becoming more and more expensive. The current LEPs are twice as expensive as the W76-1 LEP, and the new warheads in the SSMP are projected to cost three-and-a-half times that amount (see figure below). Once the programs get underway, the early estimates will likely prove to be too low. The reason for this dramatic increase is that the nuclear laboratories and the military add more and more bells and whistles and new components to more advanced warhead designs that increase complexity and cost.

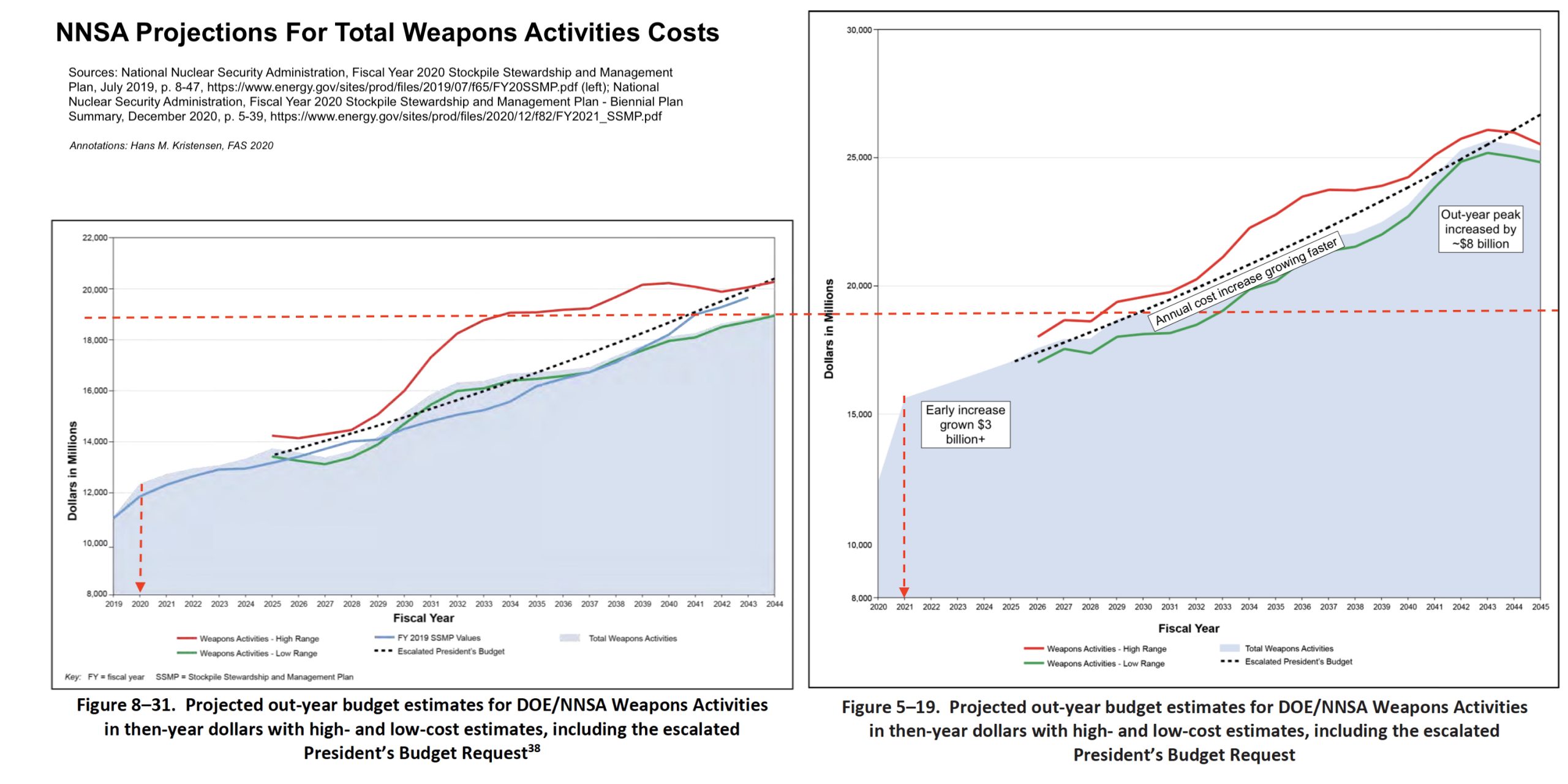

The 2020 SSMP shows increased costs for nuclear weapons life-extensions compared with the previous SSMP (in then-year dollars). A rough comparison of the two reports shows that the cost bow wave peak in 2030 is about $600 million higher than projected last year, the early phase of the bow wave increases faster and sooner, and the future costs are leveling off later and higher than projected in the 2019 report (see figure below).

NNSA cost projection for warhead life-extension programs is increasing. Click on figure to view full size.

Similarly, the cost projection for total Weapons Activities in the 2020 SSMP shows a significant increase across the board. The peak projected for the early-2040s has increased by approximately $8 billion, the increase in the early 2020s has increased by more than $3 billion, and the annual cost increase is growing faster than projected in the 2019 SSMP.

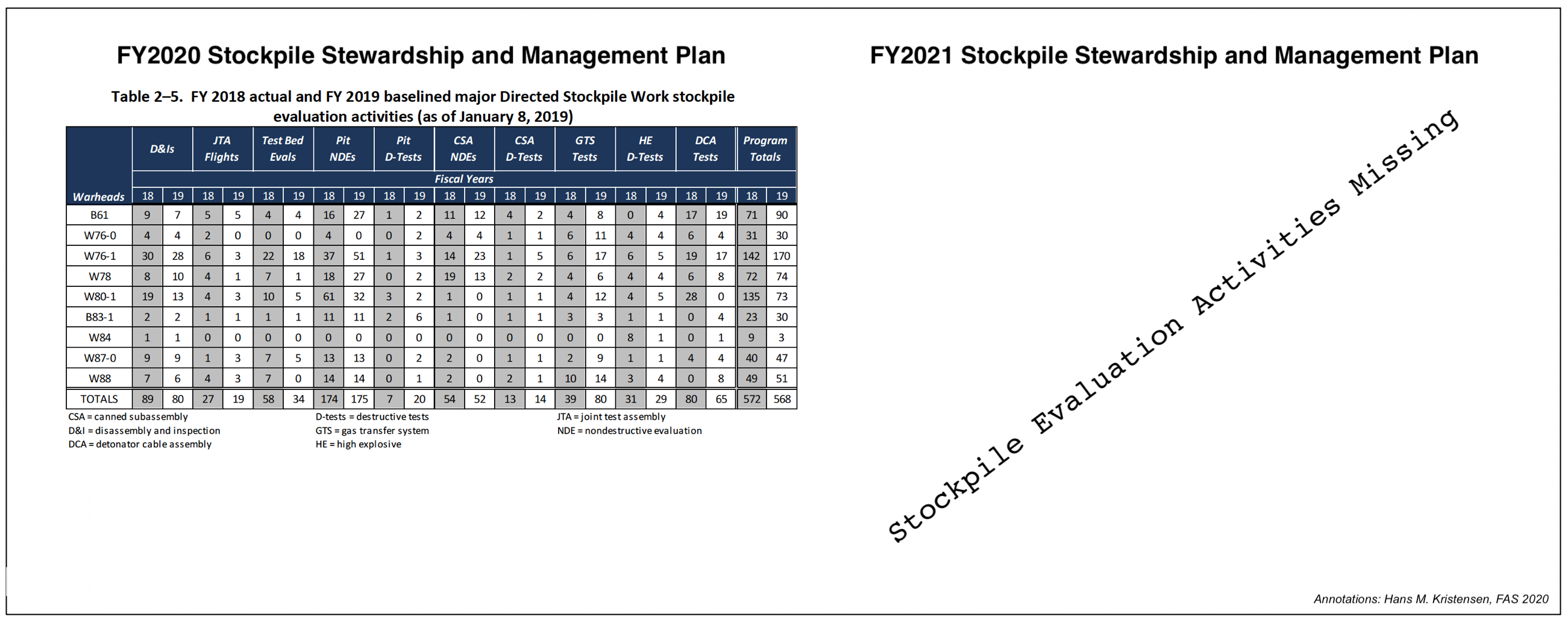

Reducing Nuclear Transparency

The 2020 SSMP significantly reduces nuclear weapons information made available to the public. Contrary to the 2019 SSMP, the new report is not a full report but a plan summary. It is only about half the size of 2019 SSMP (192 pages versus 364). Important information that was previously made available is not included at all or significantly reduced.

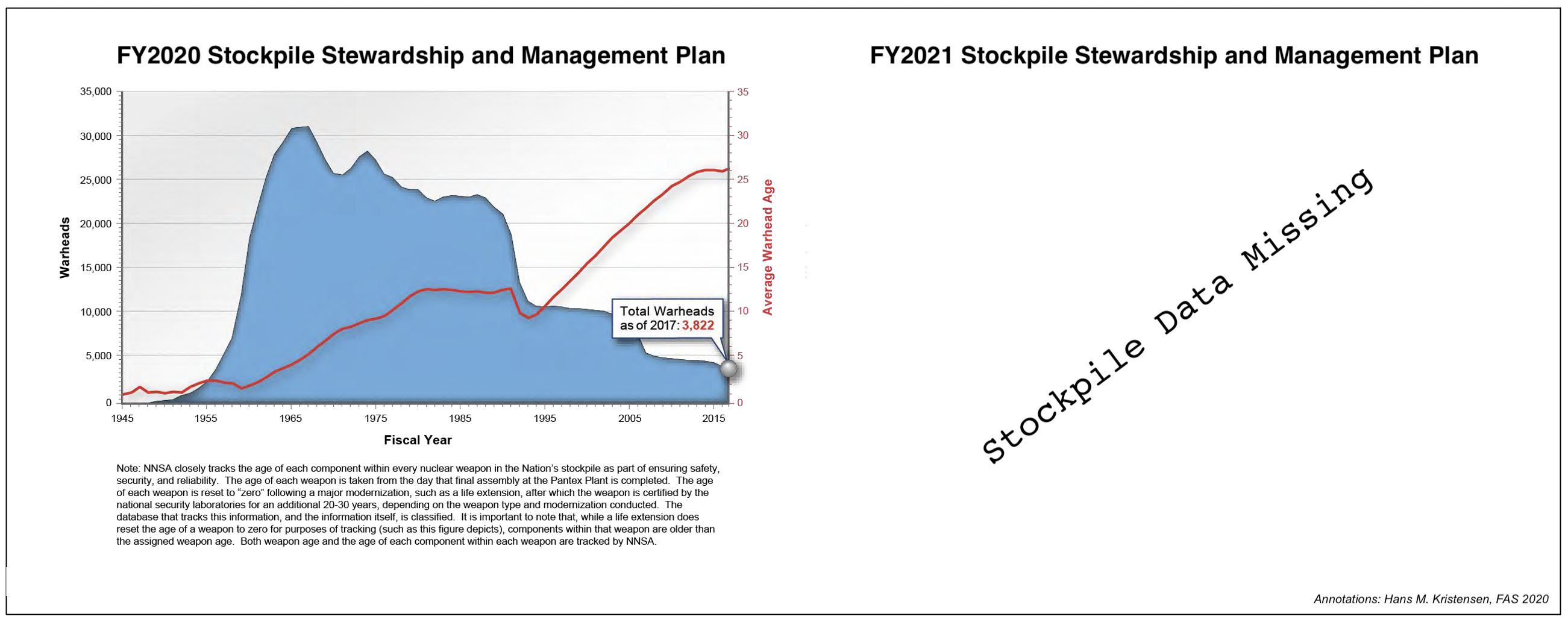

One example of omitted information is the United States nuclear weapons stockpile, which is completely missing from the new report. The 2019 SSMP included a chart that showed the history and size of the stockpile and the average age of stockpiled warheads. The omission of the stockpile data coincides with the Trump administration’s refusal to declassify the stockpile data for the past two years.

The new NNSA plan no longer includes nuclear weapons stockpile data. Click on image to view full size.

Another example of omitted information is data about warhead sustainment activities. The 2019 SSMP includes two charts that showed the number of such activities for each warhead as well as the total number of sustainment tests. Such information is not included in the 2020 version.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) deserves credit for publishing the 2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP). Other nuclear-armed states should follow the example to increase transparency of their nuclear weapons activities to avoid misunderstandings, reduce worst-case planning, and increase trust. That said, the new SSMP shows some concerning trends.

First, the plan shows a nuclear modernization program that goes well beyond modernizing the existing nuclear deterrent to increasing the types – and in the future potentially the number – of nuclear weapons and enhancing their military capabilities as part of growing competition with other nuclear-armed states.

Second, the plan shows nuclear weapon modernization programs where costs are not only increasing but doing so faster. The plan shows that NNSA anticipates that significant additional funding is required in the years ahead. The increased costs to the taxpayers come at a time when the US economy is buckling under the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic. And the nuclear modernization costs compete with funding for other high-priority programs.

Third, the NNSA plan continues a worrisome trend of increased secrecy by significantly reducing the type and amount of information previously made available in SSMP reports about nuclear modernization programs and activities. This reduces the public’s ability to monitor government programs, ask questions, and make informed decisions.

The 2020 SSMP is a timely reminder that the incoming Biden administration must trim and adjust the nuclear weapons modernization program to make it more affordable, sustainable, and justifiable. It must do so in a way that safeguards US national security and that of its allies while reducing international tension and military competition. Some adjustments can be unilateral, others bilateral, while some will require broader international cooperation.

Background information:

2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan – Biennial Plan Summary

2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size

The Trump administration has denied a request from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile and the number of dismantled warheads.

The denial was made by the Department of Defense Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) in response to a petition from Steven Aftergood, director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, “that the Department of Energy (and the Department of Defense) authorize declassification of the size of the total U.S, nuclear stockpile and the number of weapons dismantled as of the end of fiscal year 2020.”

The decision to deny release of the data contradicts past US disclosure of such information, undercuts US criticism of secrecy in other nuclear-armed states, and weakens US ability to document its adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. As Aftergood explained in the petition letter:

[su_quote]We believe that the reasons that led to the previous declassifications of stockpile information are still valid. The benefits of declassification are substantial while the detrimental consequences, if any, are insignificant.

As the first nuclear weapons state, the United States should strive to set a global example for clarity and transparency in nuclear weapons policy by disclosing its current stockpile size. Ambiguity is not helpful to anyone in this context.

Far from diminishing security, a credible USG account of its stockpile size both enhances deterrence and serves as a confidence building measure. Even if other nations do not immediately follow our lead, stockpile declassification sends a valuable message. And at a time when the future of US nuclear weapons policy is under discussion in Congress and elsewhere, stockpile disclosure also helps to provide a factual foundation for ongoing public deliberation.[/su_quote]

In its denial letter, the DOD Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) did not respond to these points and gave no reason for the denial other than stating that “the information requested cannot be declassified at this time.”

Stockpile Size and Developments

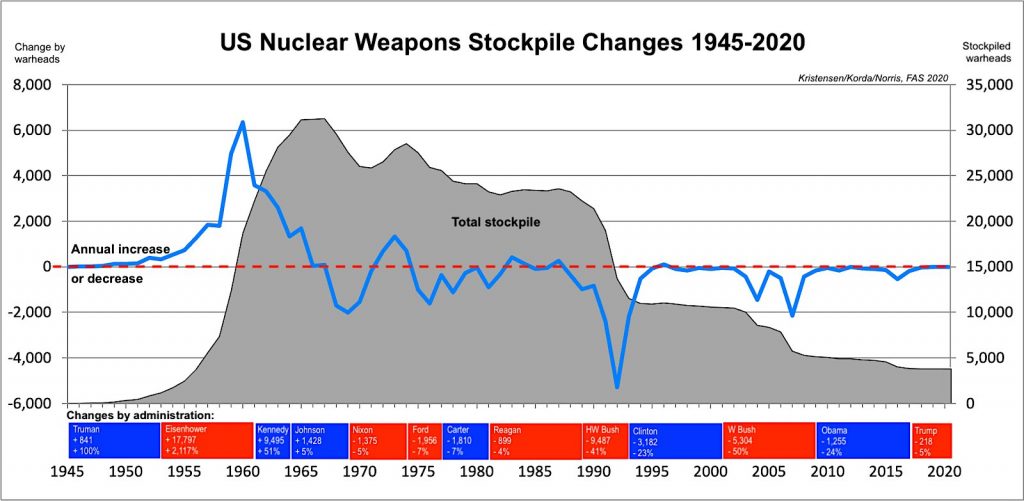

The decision to deny declassification of the warhead stockpile and dismantlement numbers contradicts the publication of such data between 2010 and 2017 during which the Obama administration released annual numbers as well as the entire history of the stockpile size going back to 1945.

The decision also contradicts the decision in 2018 to declassify the data for 2017, the first year of the Trump administration.

In 2019, however, the Trump administration suddenly, and without explanation, decided to withhold the stockpile data.

The available data shows significant fluctuations in the size of the US stockpile over the years depending on how the various administrations increased or decreased the number of nuclear weapons. The graph below shows the size of the stockpile over the years and the in- and out-flux of warheads from the stockpile. As far as we can gauge, the stockpile has remained relatively stable for the past three years at around 3,800 warheads. And the number of warheads dismantled per year is probably currently in the order of 300-350.

The size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile has fluctuated considerably over the years but remained relatively stable during the Trump administration. Click on image to view full size.

Implications and Recommendations

The decision by the Trump administration to deny declassification of the nuclear weapons stockpile size and dismantlement numbers contradict release of such data in the past for no apparent reason.

The increased secrecy of the US nuclear weapons arsenal comes at a time when the Trump administration has been criticizing China for “its secretive, nuclear crash buildup…” The administration’s criticism would carry a lot more weight if it didn’t hide its own stockpile behind a “great wall of secrecy.”

In addition to undercutting the US ability to push for greater transparency among other nuclear-armed states, the decision to classify warhead stockpile and dismantlement data also weakens the ability of the United States to demonstrate good faith on its efforts to continue to reduce its nuclear arsenal in the context of the upcoming review conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The decision enables conspiracists to spread false rumors that the United States is secretly increasing its nuclear arsenal.

The incoming Biden administration should overturn the Trump administration’s excessive and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency of the US nuclear warhead stockpile and dismantlement data.

Background Information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

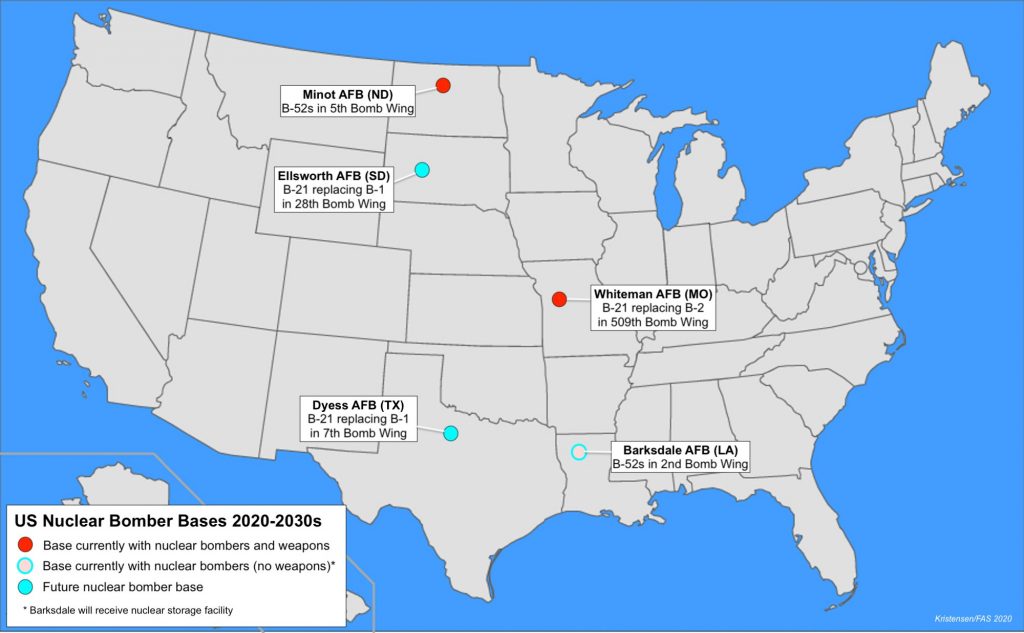

USAF Plans To Expand Nuclear Bomber Bases

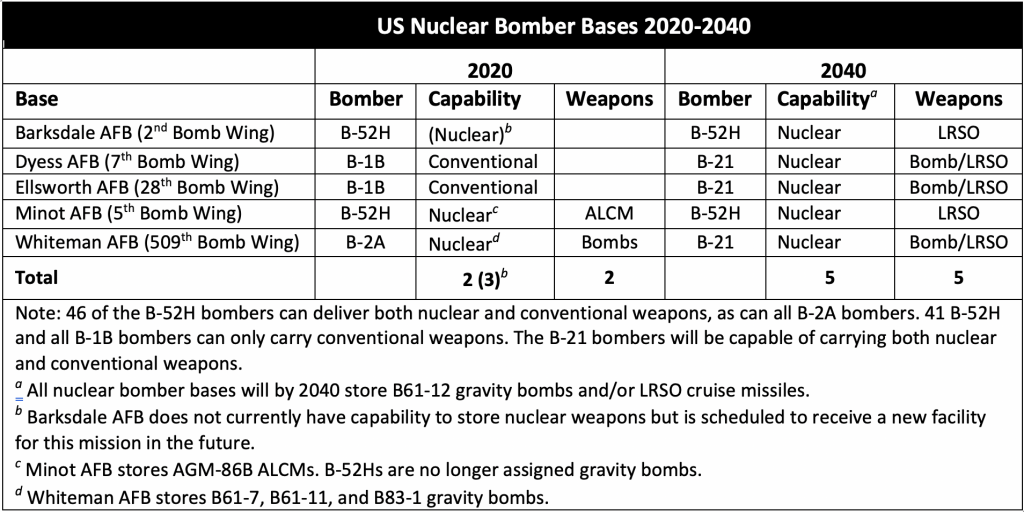

The US Air Force is working to expand the number of strategic bomber bases that can store nuclear weapons from two today to five by the 2030s.

The plan will also significantly expand the number of bomber bases that store nuclear cruise missiles from one base today to all five bombers bases by the 2030s.

The expansion is the result of a decision to replace the non-nuclear B-1B bombers at Ellsworth AFB and Dyess AFB with the nuclear B-21 over the next decade-and-a-half and to reinstate nuclear weapons storage capability at Barksdale AFB as well.

The expansion is not expected to increase the total number of nuclear weapons assigned to the bomber force, but to broaden the infrastructure to “accommodate mission growth,” Air Force Global Strike Command Commander General Timothy Ray told Congress last year.

Nuclear Bomber Base Expansion

The Air Force announced in May 2018 that the B-21 would replace the B-1B and B-2A bombers and be deployed at Ellsworth AFB, Dyess AFB, and Whiteman AFB. The commander of the strategic bomber force later explained in a video address to the B-1B bases that “the B-21 will bring significant changes to each location, to include the reintroduction of nuclear mission requirements.”

Since the B-1B was replaced in the nuclear war plan by the B-2A in 1997 and all B-1B bombers were denuclearized in 2011, the effect of the B-21 bomber program is that nuclear bomber operations will increase from the three bases today to five bases in the future (see map):

The Air Force plans to increase nuclear weapons storage capacity at bomber bases from two locations today to five in the future. Click map to view full size.

The Air Force previously planned for the B-21 to replace the B-2A no later than 2032 and the B-1Bs no later than 2036, though those dates may have shifted some since.

The effect of the integration of the B-21 is that bases with nuclear stealth bombers will increase from one today (Whiteman AFB) to three in the future.

The modernization plan also appears to significantly expand the location of nuclear cruise missiles from one base today (Minot AFB) to all five bomber bases by the late-2030s. The LRSO is scheduled to begin entering the arsenal in 2030 (see table):

The US Air Force plans a significant expansion of nuclear bomber bases and their capabilities. Click table to view full size.

Nuclear Storage Facilities

A key element of the base upgrades to operate the B-21 involves the construction of a new nuclear weapons storage facility at each base: a Weapons Generation Facility (WGF). The new facility is different than the Weapons Storage Areas (WSAs) that that the Air Force built during the Cold War because it will integrate maintenance and storage mission sets into the same facility. The WGF will have a footprint of roughly 35 acres and include an approximately 52,000-square-foot (4,860 square meters) building as well as a 17,600 square-foot munitions maintenance building. The Air Force says the WGF will be “unique to the B-21 mission” and designed to provide a “safer and more secure location for the storage of Air Force nuclear munitions.”

An WGF is also under construction at F.E. Warren AFB for storage of ICBM warheads.

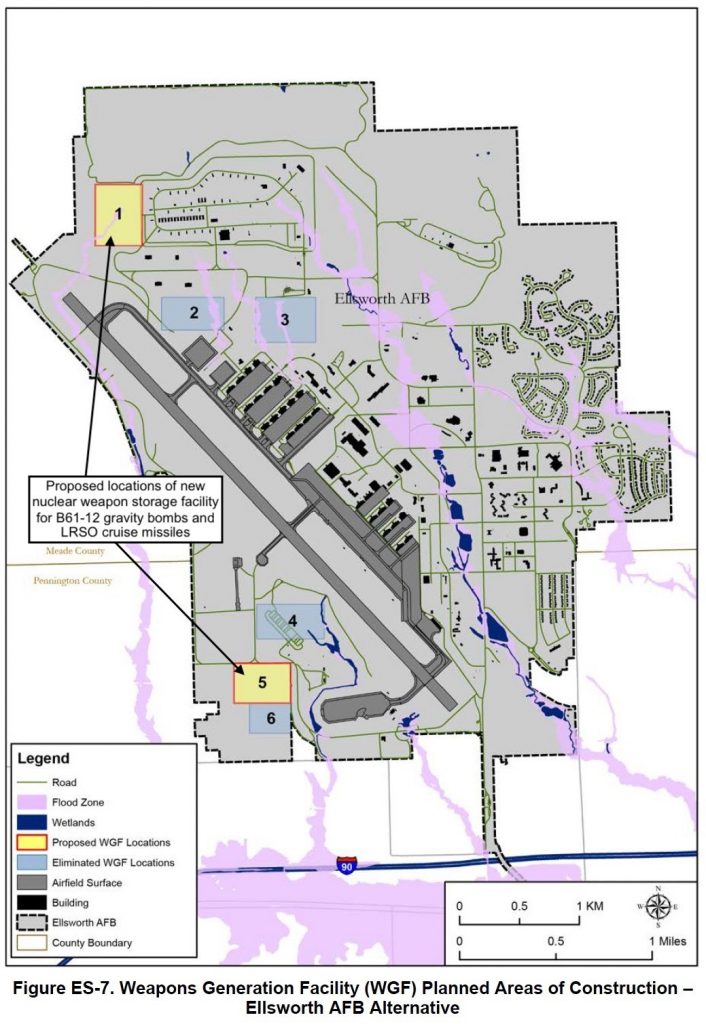

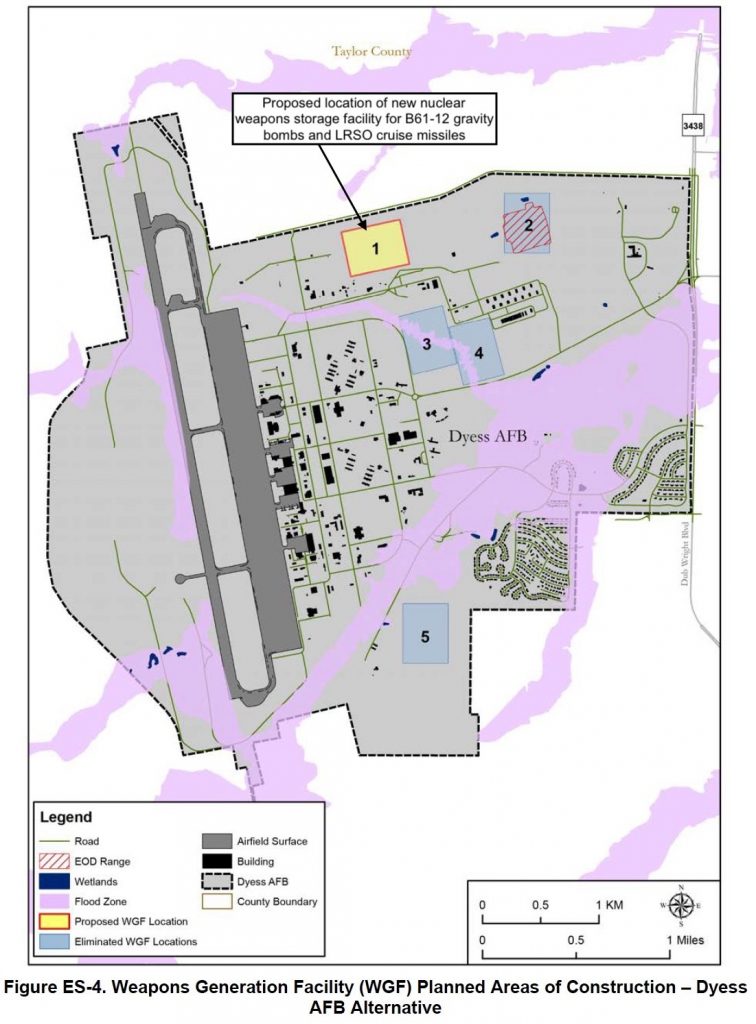

A draft Environmental Impact Statement recently posted by the Air Force shows the planned location of the nuclear weapons storage facility at Dyess and Ellsworth air force bases. At Dyess AFB, the intension is to build facility at the northern end of the base near the current munitions depot (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Dyess Air Force Base in Texas. Click on map to view full size.

At Ellsworth AFB, the Air Force has identified two preferred locations: one at the northern end near the munitions depot, and one at the southern end near the aircraft alert apron (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota. Click on map to view full size.

Although Barksdale AFB is not scheduled to receive the B-21, preparations are underway to reinstate the capability to store nuclear weapons at the base. The capability was lost when the Air Force last decade consolidated operational nuclear ALCM storage at Minot AFB. Once completed, the new WGF will enable the base to store nuclear LRSO cruise missiles for delivery by the B-52s.

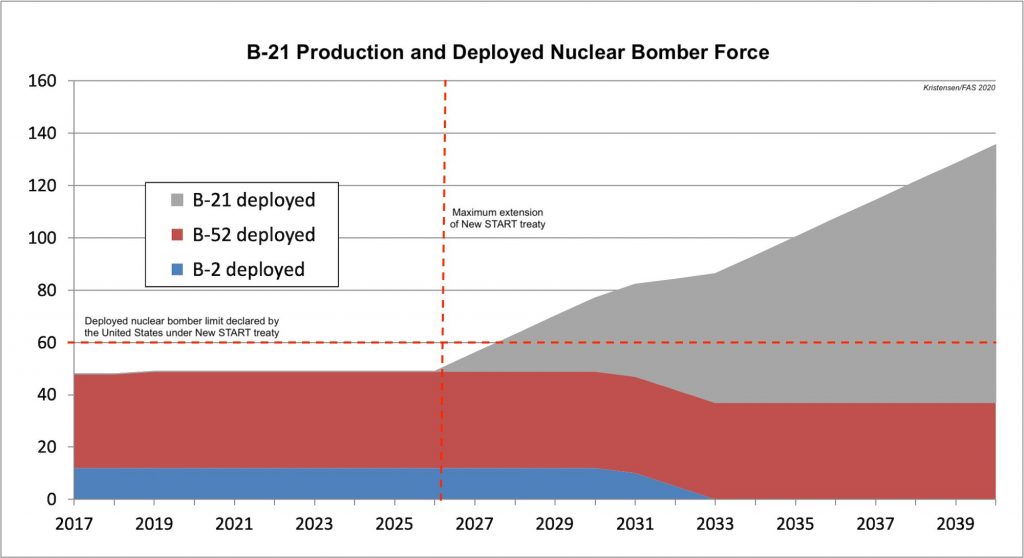

Nuclear Bomber Force Increase

The B-21 bomber program is expected to increase the overall size of the US strategic bomber force. The Air Force currently operates about 158 bombers (62 B-1B, 20 B-2A, and 76 B-52H) and has long said it plans to procure at least 100 B-21 bombers. That number now appears [https://www.airforcemag.com/article/strategy-policy-9/] to be at least 145, which will increase the overall bomber force by 62 bombers to about 220. There are currently nine bomber squadrons, a number the Air Force wants to increase to 14 (each base has more than one squadron).

During an interview with reporters in April, the head of AFGSC, General Timothy Ray, reportedly said the 220 number was a “minimum, not a ceiling” and added: “We as the Air Force now believe it’s over 220.” Whether Congress will agree to pay for that many B-21s remains to be seen.

The fielding of large numbers of nuclear-capable B-21 bombers has implications for the future development of the US nuclear arsenal. Under the New START treaty, the United States has declared it will deploy no more than 60 nuclear bombers. Although the treaty will lapse in 2026 (after a five-year maximum extension), it serves as the baseline for long-term nuclear force structure planning.

Unless the Air Force limits the number of nuclear-equipped B-21 bombers to the number of B-2As operated today, the number of nuclear bombers would begin to exceed the 60 deployed nuclear bomber pledge by 2028 (assuming an annual production of nine aircraft and two-year delay in deployment of the first nuclear unit). By 2035, the number of deployed nuclear bombers could have doubled compared with today (see graph below):

Unless nuclear B-21 bombers are not limited, the future nuclear bomber force could significantly exceed the bomber force under the current New START treaty. Click graph to view full size.

It is difficult to imagine a military justification for such an increase in the number of nuclear bombers – even without New START. One would hope that the number of nuclear B-21s will be limited to well below the total number. Although the New START treaty would have expired before this becomes a a legal issue, it would already now send the wrong message to other nuclear-armed states about US long-term intensions, deepen suspicion and “Great Power Competition,” and could complicate future arms control talks.

In the short term, the incoming Biden administration should commit the United States to not increase the number of nuclear bombers beyond those planned under the New START treaty, and it should urge Russia to make a similar declaration about the size of its nuclear bomber force.

See also: Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear force, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

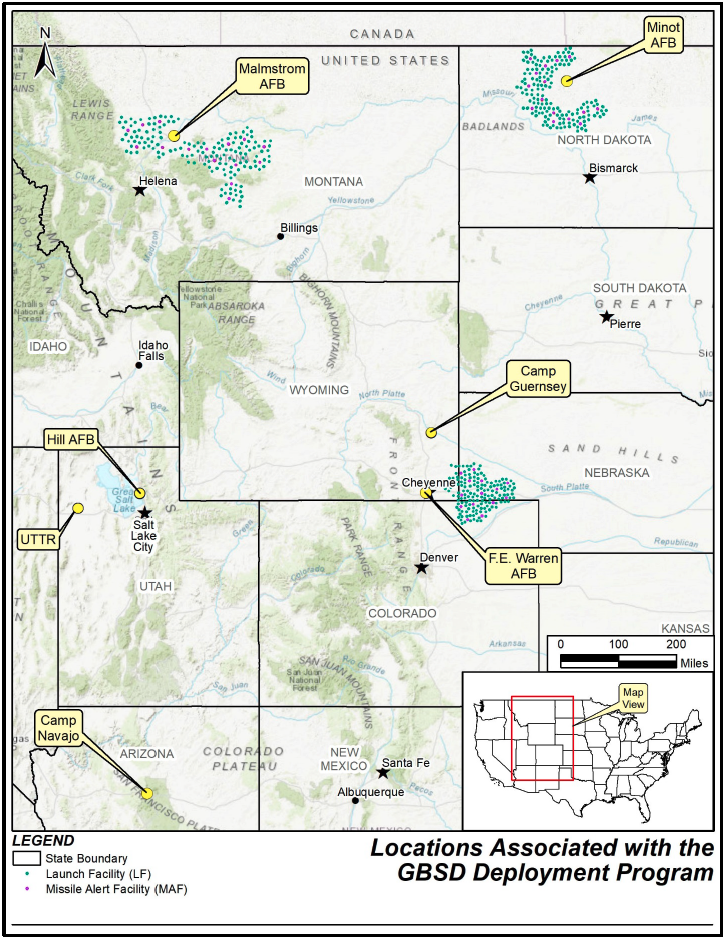

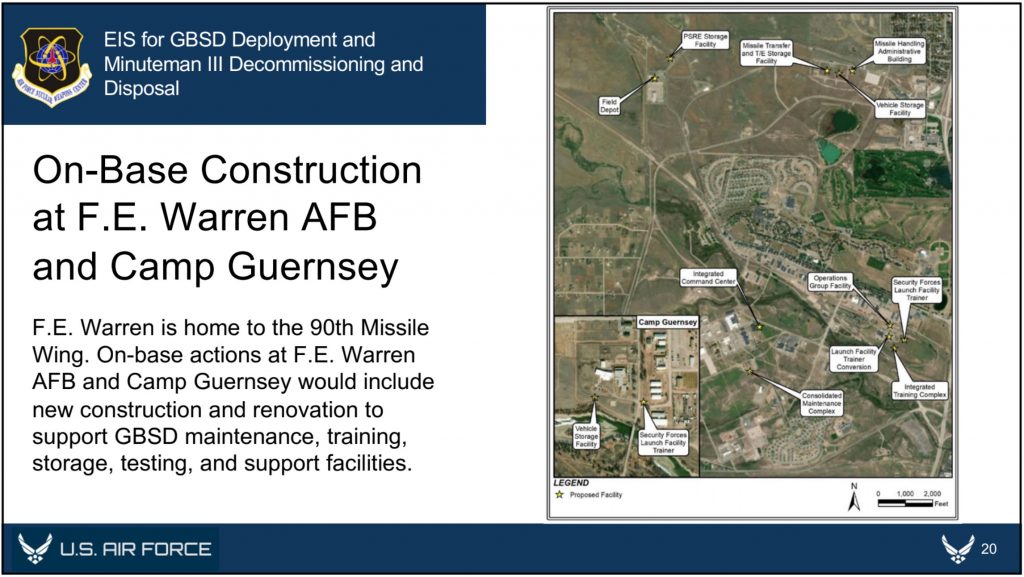

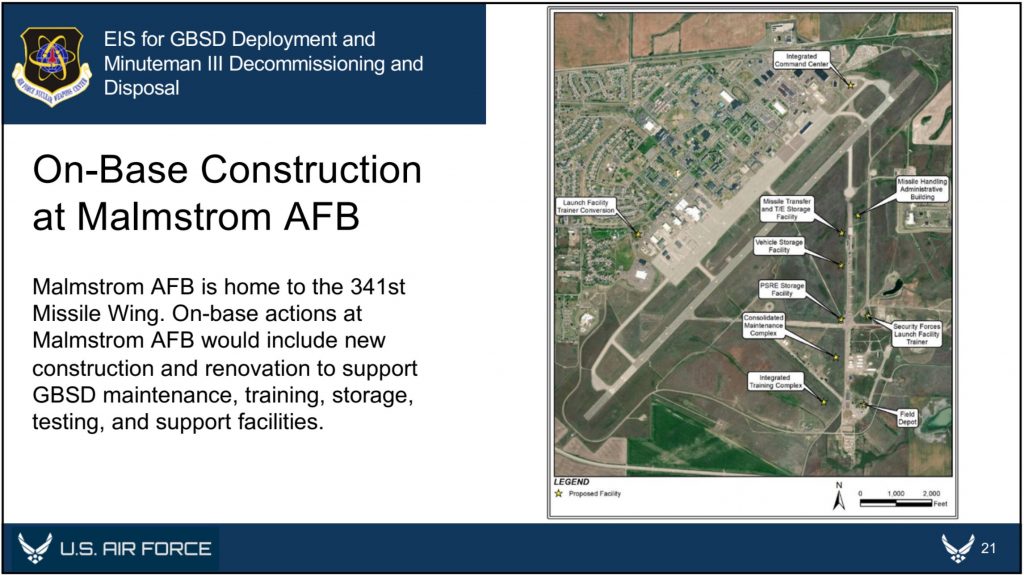

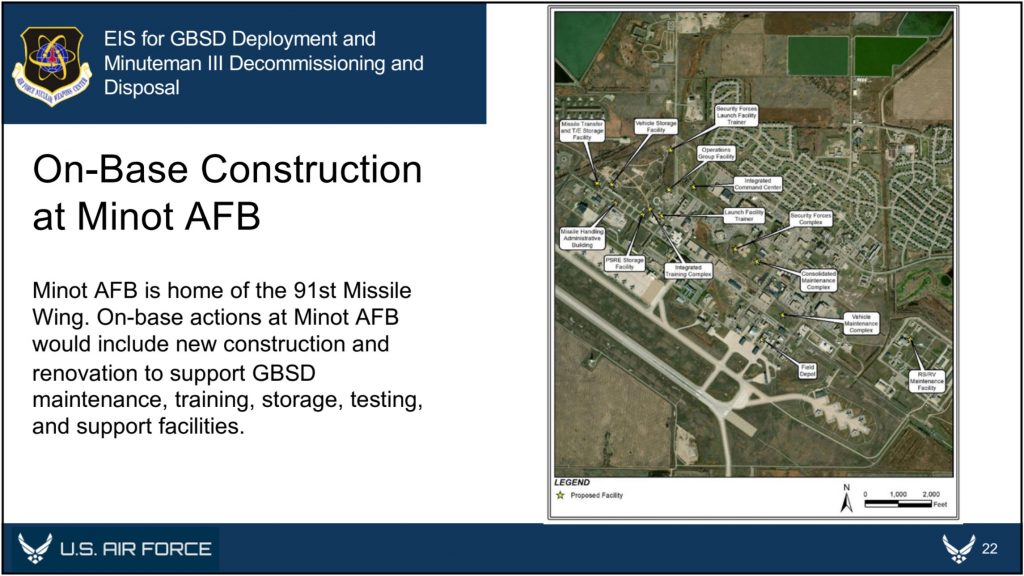

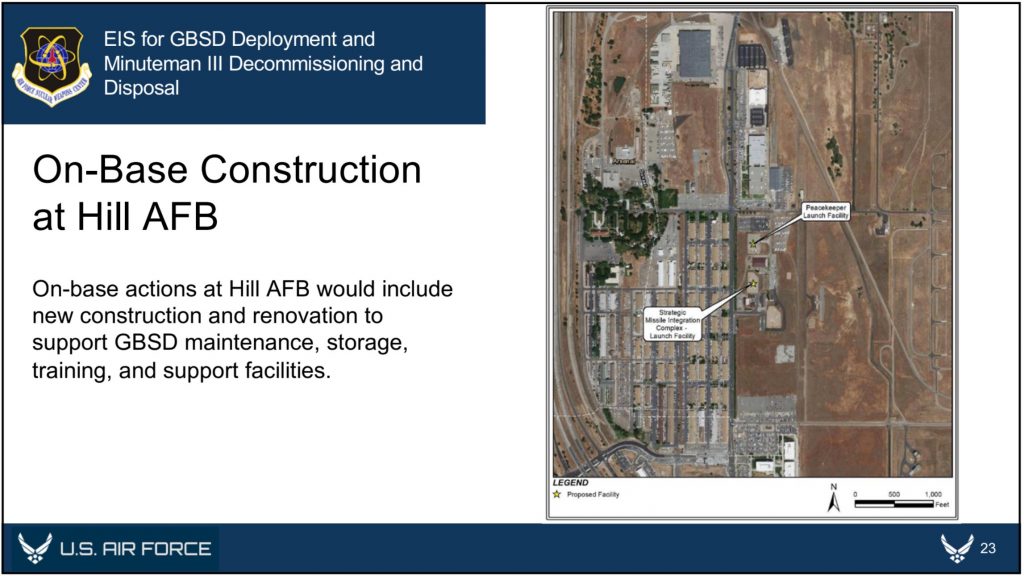

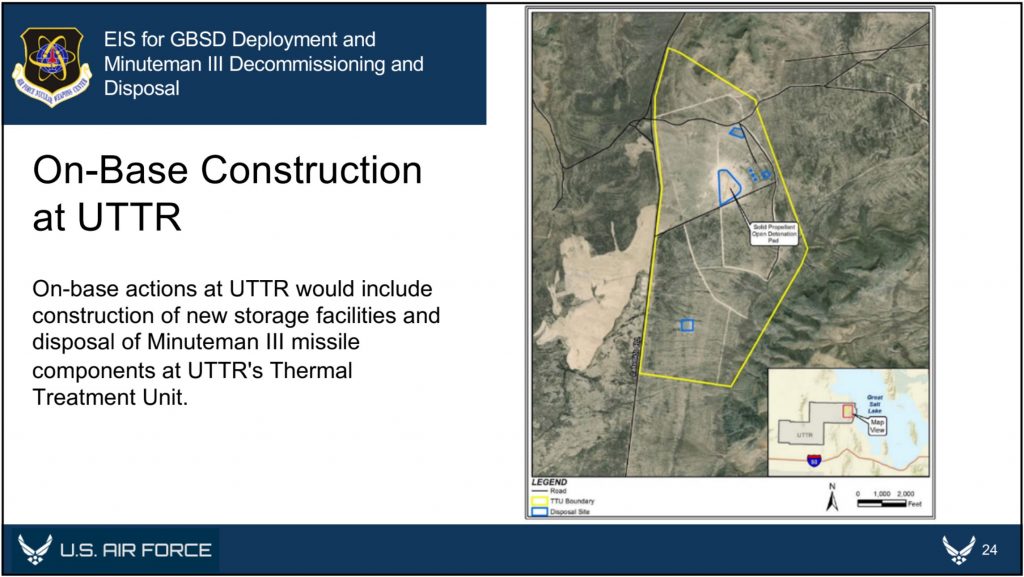

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

US Officials Give Confusing Comparisons Of US And Russian Nuclear Forces

October 22, 2020 [updated]

In their effort to paint the New START treaty as insufficient and a bad deal for the United States and its allies, Trump administration official have recently made statements suggesting the treaty limits the US nuclear arsenal more than it limits the Russian arsenal.

New START imposes the same restrictions on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces.

During a virtual conference organized by the Heritage Foundation on October 13, Marshall Billingslea, special presidential envoy for arms control, stated: “What we’ve indicated to the Russians is that we are in fact willing to extend the New START Treaty for some period of time provided that they agree to a limitation, a freeze, in their nuclear arsenal. We’re willing to do the same. I don’t see how it’s in anyone’s interests to allow Russia to build up its inventory of these tactical nuclear weapons systems with which they like to threaten NATO…We cannot agree to a construct that leaves unaddressed 55 percent or more of the Russian arsenal.”

One week later, in an interview on National Public Radio, Billingslea added: “The New START treaty constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent” but “only covers 45 percent or less of the Russian arsenal…”

Finally, on October 21, Secretary of State Michal Pompeo repeated this talking point: “President Trump has made clear that the New START Treaty by itself is not a good deal for the United States or our friends or allies. Only 45 percent of Russia’s nuclear arsenal is subject to numerical limits, posing a threat to the United States and our NATO allies. Meanwhile, that agreement restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits contained in the New START agreement.”

Pompeo and Billingslea didn’t specify what they meant by “arsenal” and the reaction from nuclear weapons analysts – ourselves included – was bewilderment. Most assumed “arsenal” was referring warheads, but the numbers don’t seem to fit with the percentages and descriptions in the statements. Interestingly, the percentages and categories seem to work better for launchers, unless one does a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Matching Comparison With Warheads

Our first step was to analyze the statements and see if we could make them fit with our understanding of the size and composition of the nuclear arsenals. If we assume the percentages and descriptions refer to warhead numbers, then we see the following potential options:

Option 1: The 45% refers to New START warhead limit for deployed strategic warheads (1,550). If this were the case, then Russia’s entire stockpile would only consist of 3,445 warheads, which we doubt. Our estimate is 4,310. For the United States, 1,550 would only constitute 41% of the US stockpile, not 92% as stated by Billingslea.

Option 2: The 45% refers to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto ICBMs and SLBMs but not bomber weapons. New START counts actual numbers of warheads on deployed ICBMs and SLBMs, but not those on bomber bases. According to our estimate of Russian forces, their ICBMs can load 1,136 warheads and SLBMs can load 720 warheads, a total of 1,856 warheads. That would constitute 43% of the total stockpile of 4,310 warheads (our estimate). It would of course be embarrassing if the US officials have been using our numbers instead of those of the US Intelligence Community. Even so, that methodology does not fit with the 92% comparison used for the United States. US ICBMs and SLBMs can load a maximum of 2,720 warheads, by our estimate, or 72% of the stockpile. And Billingslea explicitly says the US comparison includes the “entire” arsenal.

Option 3: The 45% refers to the total number of strategic warheads in the Russian arsenal (deployed and non-deployed). If that were the case, then the remaining 55% of 3,025 warheads would be non-strategic warheads, far more than the “up to 2,000” stated in the Nuclear Posture Review. And it would imply a total stockpile of 5,500 warheads, far more than the number of warhead spaces on launchers.

Option 4: The percentage numbers come from a simplistic back-of-the-envelope calculation. The Russian 45% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 2,000 (tactical). The US 92% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 150 (tactical). Those numbers don’t fully match the stockpiles and statements but can explain the comparison. (We are indebted to Pavel Podvig for suggesting this option.)

Billingslea and Pompeo both compared the Russian restrictions to those affecting the US arsenal, but they described it differently.

Billingslea said New START “constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent…” (emphasis added). Since we know the approximate size of the total US stockpile (about 3,800 warheads), 92% would constitute 3,496 warheads, far more than the treaty’s limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. But the count would be close to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto strategic launchers (3,570 by our estimate), leaving about 300 non-strategic warheads.

Pompeo said that New START “restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits” (emphasis added), which is different than what Billingslea said because it doesn’t appear to include non-deployed strategic warheads or tactical warheads, two categories that are not subject to the treaty limits.

Matching Comparison With Launchers

Our next step was to analyze the statements to see how they compare with the number of launchers that can deliver nuclear warheads. New START limits both sides to no more than 800 strategic launchers in total, of which no more than 700 can be deployed at any given time.

In the latest set of aggregate numbers released by the US State Department, the United States is listed with exactly 800 launchers in total, of which 675 are deployed. Russia is listed with a total of 764 launchers, of which 510 are deployed.

While complaining about limits on US and Russian weapons, neither Billingslea nor Pompeo mentions this US strategic advantage of 165 deployed launchers, a number that exceeds the number of Minuteman IIIs in one missile wing and corresponds to more than half of the entire Russian ICBM force.

For the United States, if the 800 total strategic launchers constitute 92% of all US nuclear launchers (“entire” arsenal), then that would imply the existence of another 70 launchers, which potentially could refer to non-strategic fighter-bombers assigned missions with gravity bombs.

For Russia, if the 764 total strategic launchers constitute 45% of all its nuclear launchers, that would potentially imply that Russia has 1,698 total nuclear launchers, of which 934 would be launchers of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

We don’t yet know if this is the case. But the percentages mentioned by Billingslea and Pompeo appear to fit better if they refer to launchers than warheads, unless one applies the Option 4 calculation described above. The Trump administration has been particularly critical about Russia’s development of new types of strategic-range weapons that are not covered by the New START treaty, just like it has criticized that Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are not covered by any arms control agreement.

Context and Recommendations

The comparisons and descriptions of Russian and US nuclear forces presented by Billingslea and Pompeo are confusing. Some might suspect “fuzzy math” but until we see otherwise, we suspect the comparisons use real data. Option 4 above might represent the most likely explanation although it doesn’t fully match the stockpiles and descriptions provided by the officials.

When it comes to nuclear negotiations, it is incredibly important to be precise with official words and statements, in order to avoid misunderstandings or mischaracterizations. Unfortunately, the Trump administration has a habit of cherry-picking or spinning statistics in an apparent attempt to make existing and equitable arms control agreements seem like “bad deals” for the United States. Given this track record, we should view their statements here with skepticism and ask for clarification if they’re referring to warheads or launchers. We have done so but have not yet heard back from the State Department.

A one-year extension of New START is better than no extension, but it’s worse than a five-year extension because it creates uncertainty about the commitment to continue to limit force levels and unnecessarily shortens the time available to negotiate follow-on arrangements. There is no technical need to shorten the extension. If a new deal is made, the old one will fall away.

A freeze on warheads would be a welcoming new step and Russia’s acceptance of the idea is a breakthrough because it opens up possibilities for building on this idea in the future. But a freeze will not have much credibility or effect without verification and despite saying it would like “portal monitoring” the Trump administration has not presented a plan for how this would work or secured Moscow’s agreement. Verification of a total warhead freeze would be much more complex than verifying the New START treaty itself and one year may not be sufficient to do the work. Has the US military and intelligence community signed off on Russian inspectors monitoring every US warhead moving in and out of facilities? Have US allies in Europe agreed to allow Russian officials to monitor the bases where the US Air Force stores nuclear bombs?

Russia’s acceptance of a one-year New START extension and a declaration to freeze warhead levels is a significant compromise from its previous offer to unconditionally extend the treaty by five years with no warhead freeze.

The Trump administration’s “offer” of a one-year extension of New START and a one-year warhead freeze with no verification at the outset represents an astounding walk-back from its previous statements. Trump has repeatedly called New START a “bad deal” and the whole point of the talks was to “fix” what the administration claimed was inadequate verification, incorporate Russia’s new strategic weapons into the agreement, and get China onboard. And how many times have we heard that you can’t trust Russia because they violate every arms control agreement they have signed? Yet here we are. None of those “fixes” are attached to the one-year treaty extension and the administration now says it is willing to sign on to a warhead freeze without agreed verification measures with the Great Cheater.

There is nothing wrong with trying to broaden arms control to other weapons categories and countries. We strongly support that. But the last-minute flurry and attempts to shorten extension strongly suggest that the Trump administration has been more focused on creating chaos and to appear tough on Moscow and Beijing than to create nuclear arms control progress. The one-year timeline unnecessarily constrains both countries and could well mean that they would be in pretty much the same situation one year from now.

The inconvenient fact is that New START is working as designed and keeps the vast majority of Russian and US strategic arsenals in check, prevents either country from uploading thousands of extra warheads onto their deployed missiles, and offers a modicum of predictability in an otherwise unpredictable world.

Additional background information:

- Status of world nuclear forces, September 2020

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

- Russian nuclear forces, 2020

- At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty

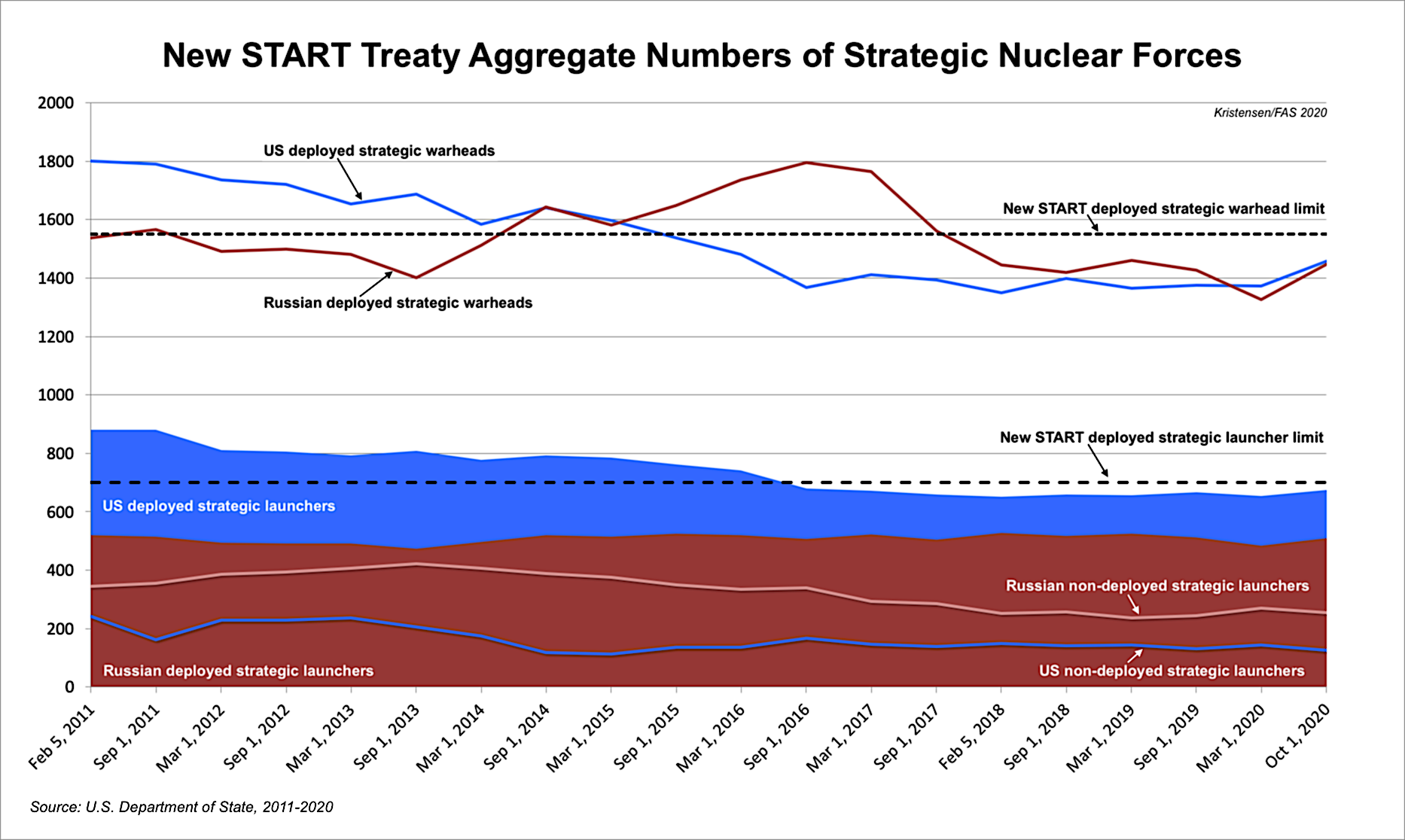

Just four months before the New START treaty is set to expire, the latest set of so-called aggregate data published by the State Department shows the treaty is working and that both countries – despite tense military and political rhetoric – are keeping their vast strategic nuclear arsenals within the limits of the treaty.

The treaty caps the number of long-range strategic missiles and heavy bombers the two countries can possess to 800, with no more than 700 launchers and 1,550 warheads deployed. The treaty entered into force in February 2011, into effect in February 2018, and is set to expire on February 5, 2021 – unless the two countries agree to extend it for an additional five years.

Twice a year, the two countries have exchanged detailed data on their strategic forces. Of that data, the public gets to see three sets of numbers twice a year (1 March and 1 October): the aggregate data of deployed launchers, warheads attributed to those launchers, and total launchers. This time, the web-version helpfully includes the full data set (including a breakdown of US forces; it would be helpful is Moscow could also publish its breakdown) but the PDF-version does not.

This is the final set of periodic six-month aggregate data to be released, although a final set will probably be released if the treaty expires in February. If the treaty is extended for another five years, an additional ten data sets would probably be released.

The nearly ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of October 1, 2020. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,564 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,185 launchers were deployed with 2,904 warheads. That is a slight increase in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with March 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 10, increased combined deployed strategic launchers by 45, and increased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 205. Of these numbers, only the “10” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 have cut 425 strategic launchers from their combined arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 218, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 433. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (less than 6 percent) of the estimated 8,110 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (less than 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 12,170 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, the maximum number allowed by the treaty, of which 675 are deployed with 1,457 warheads attributed to them. This is an increase of 20 deployed strategic launchers and 84 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual increases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The warhead numbers are interesting because they reveal that the United States now deploys 1,009 warheads on the 220 deployed Trident missiles on the SSBN fleet. That’s an increase of 82 warheads compared with March and the first time since 2015 that the United States has deployed more than 1,000 warheads on its submarines, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for nearly 70 percent of all the 1,457 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 72 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data reveals that the United States as of October 1, 2020 deployed over 1,000 warheads on its fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 207, and deployed strategic warheads by 343. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 9 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 6 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 764 strategic launchers, of which 510 are deployed with 1,447 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 25 deployed launchers and 121 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 101, deployed launchers by 11, and deployed strategic warheads by 90. This modest warhead reduction represents about 2 percent of the estimated 4,310 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (not even 3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,370 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials and nuclear weapons advocates that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 165 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap that exceeds the size of an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by one-third since its lowest point in February 2018. One factor that could change this is if the Trump administration kills New START and Russia believes the threat made by Marshall Billingslea, the Trump administration’s Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control, that the United States might increase its nuclear forces if New START expires.

The New START data shows that Russia’s nuclear modernization program has not been trying increase the number of launchers despite a sizable gap compared with the US arsenal.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher gap by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles that are replacing older types (Yars and Bulava). Many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance, however, but stored and could potentially be uploaded onto launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (Avangard and Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types, which have become a sticking point for the Trump administration, are in relatively small numbers (if they have even been deployed yet) and do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types.

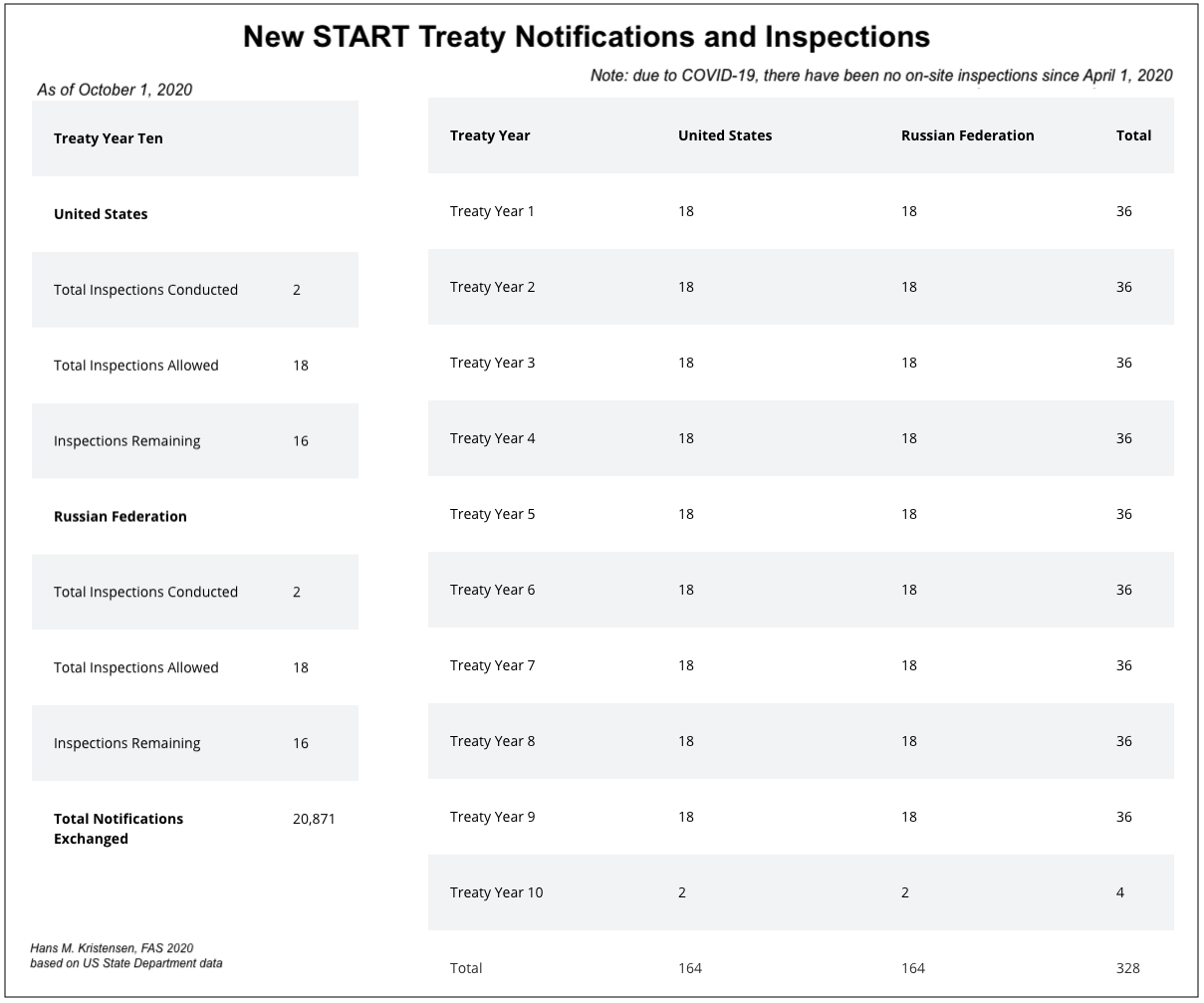

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 20,871 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 1,200 of those notifications were exchanged since March 5, 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Treaty opponents might use this to argue that compliance with the treaty cannot be determined or that it shows it’s irrelevant. Both claims would be wrong because National Technical Means of verification also provide insight to activities on the ground, but that on-site inspections provide valuable additional data.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for US-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

The 11th Hour

Time is now quickly running out for New START with only a little over four months remaining before the treaty expires on February 5, 2021. Rather than working to secure extension, the Trump administration instead has introduced last-minute conditions that threaten to derail extension.

Russia and the United States can and should extend the New START treaty as is by up to 5 more years. Once that is done, they should continue negotiations on a follow-on treaty with additional limitations and improved verification. It is essential both sides act responsibly and do so to preserve this essential cornerstone of strategic stability.

The fact that Marshall Billingslea has already threatened to increase US nuclear forces if Russia doesn’t agree to the US conditions for extending the treaty only reaffirms how important New START is for keeping a lid on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces and for providing transparency and predictability on the status and plans for the arsenals.

Additional background information:

Status of world nuclear forces, September 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

Construction has begun of a new nuclear weapons storage facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base. Click on image to view full size

The Air Force has begun construction of a new underground nuclear weapons storage and handling facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The new Weapons Storage and Maintenance Facility (WSMF; sometimes called Weapons Generation Facility), which will replace the current Weapons Storage Area (WSA), will be a 90,000-square-foot reinforced concrete and earth-covered facility with supporting surface structures.

A satellite image taken in August and obtained from Maxar shows construction is well underway of the underground facility as well as several supporting facilities.

The Air Force says the new facility “will provide a safer and more secure facility for the storage of U. S. Air Force (USAF) assets,” a reference to W78/Mk12A and W87/Mk21 warheads for the Minuteman III ICBMs deployed in Warren AFB’s 150 missile silos. In the future, if Congress agrees to fund it, the new W87-1 warhead will replace the W78. According to the Air Force:

“The primary interior walls of Maintenance and Storage Area are 4-foot thick reinforced concrete (RC) elements with 4-foot thick RC roof slabs. The primary wall and roof elements are surrounded by a 20-foot thick soil layer which is contained by a 3-foot thick RC wall and roof element layer. The heavy multilayered system sits on a 5-foot thick RC structural mat for support.”

The $144 million contract was awarded to Fluor Corporation by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2018. The ground-breaking ceremony took place on May 21, 2019 but substantial construction (of buildings) did not begin until the Spring of 2020. The president of Flour’s Government Group is Tom D’Agostino, who previously served as the undersecretary for nuclear security at the Department of Energy, administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), and deputy administrator for defense programs. Construction was scheduled to take 40 months and be completed in 2022.

Construction of the underground storage facility at F.E. Warren AFB follows the completion in 2012 of a massive underground nuclear weapons storage facility at the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC) next to the Kitsap Naval Submarine Base. Underground storage facilities are also planned at other bases.