Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 1

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea serious about their threats and are we on the brink of war? What influence does China exert over DPRK, and what influence is China wiling to exert over the DPRK? How does the increase in tension affect South Korean President Park Guen-he’s political agenda?

This is the first part of the Q&A featuring Dr. Ted Galen Carpenter, Dr. Balbina Hwang, Ms. Duyeon Kim and Dr. Leon Sigal. Read part two here.

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense with Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

Q: (CB) Last Friday, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

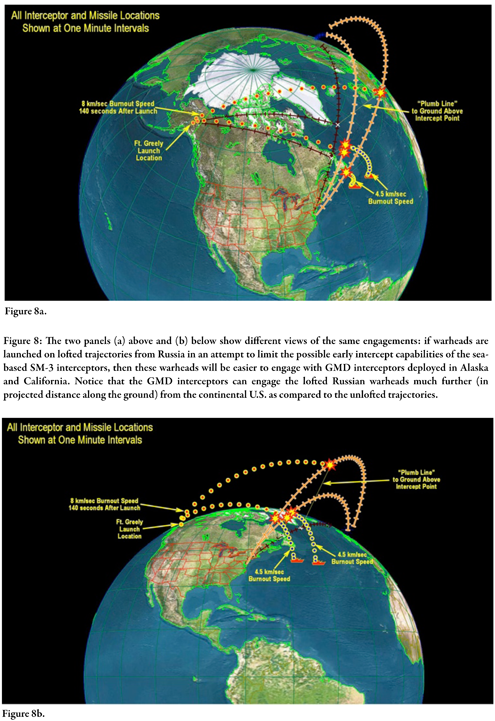

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) from the FAS Special Report Upsetting the Reset: The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense, by Yousaf Butt and Theodore Postol (p. 27).

Event: Conference on Using Satellite Imagery to Monitor Nuclear Forces and Proliferators

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Earlier today we convened an exciting conference on use of commercials satellite imagery and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to monitor nuclear forces and proliferators around the world. I was fortunate to have two brilliant users of this technology with me on the panel:

- Tamara Patton, a Graduate Research Assistant at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, who described her pioneering work to use freeware to creating 3D images of uranium enrichment facilities and plutonium production reactors in Pakistan and North Korea. Her briefing is available here.

- Matthew McKinzie, a Senior Scientists with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Nuclear Program and Lands and Wildlife Program, who has spearheaded non-governmental use of GIS technology since commercial satellite imagery first became widely available. His presentation is available here.

- My presentation focused on using satellite imagery and Freedom of Information Act requests to monitor Chinese and Russian nuclear force developments, an effort that is becoming more important as the United States is decreasing its release of information about those countries. My briefing slides are here.

In all of the work profiled by these presentations, the analysts relied on the unique Google Earth and the generous contribution of high-resolution satellite imagery by DigitalGlobe and GeoEye.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Letter Urges Super Committee to Reduce Nuclear Weapons Spending

FAS joined 48 organizations in signing a letter to United States Representatives asking them to cosign Representative Markey’s letter to members of the Super Committee. Markey’s letter urges Super Committee members to increase U.S. security by reducing spending on outdated and unaffordable nuclear weapons programs.

Additionally, this support letter offers specific suggestions to Congress on how to scale back new nuclear weapons programs and help close the budget deficit.

October 11, 2011

Dear Representative,

We, the undersigned organizations and experts, ask you to cosign Rep. Markey’s (D-MA) letter to members of the Super Committee urging them to reduce nuclear weapons spending and use the resulting savings to invest in higher priority programs.

There is broad bipartisan agreement that few national security issues are as critical as how to deal with America’s crippling debt. Getting America’s fiscal house in order will require difficult budgetary choices. This means that we need to make smart decisions about what is most needed to safeguard U.S. national security in the 21st century.

The United States currently spends over $50 billion per year on maintaining and upgrading a nuclear weapons force of 5,000 nuclear weapons and weapons related programs. These costs are expected to increase in light of the Obama administration’s plan to spend at least $200 billion over the next decade on new nuclear delivery systems and warhead production facilities. Much of this spending is designed to confront Cold War-era threats that no longer exist while posing financial and opportunity costs that can no longer be justified.

In the current economic environment, it will be counterproductive to make unsustainable, open-ended commitments to hugely expensive programs that are irrelevant to the most likely threats we face. “We’re not going to be able to go forward with weapon systems that cost what weapon systems cost today,” Strategic Command chief Gen. Robert Kehler said recently “Case in point is [the] Long-Range Strike [bomber]. Case in point is the Trident [submarine] replacement. . . . The list goes on.”

Fiscally responsible Republicans are also proposing to rein in spending on nuclear weapons. Sen. Tom Coburn (R-OK), who voted against the New START nuclear reductions treaty in December 2010, has proposed a deficit reduction plan that would cut $79 billion in spending on nuclear weapon systems over the next decade by reducing the U.S. nuclear arsenal to below the New START limit of 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear warheads and cutting the number of delivery systems and warheads in reserve and by delaying procurement of a new long-range bomber until the mid-2020s.

The United States could save billions by canceling or scaling back new nuclear weapons programs such as the plan to build 12 new nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines, which the Pentagon estimates could cost nearly $350 billion over their 50-year lifespan and new facilities to support the nuclear weapons force. For example, by building and deploying no more than 8 new SSBN(X) nuclear-armed submarines, the United States could still deploy the same number of strategic nuclear warheads at sea as is currently planned (about 1,000) under New START and save roughly $26 billion over 10 years, $31 billion over 30 years, and $120 billion over the life of the program.

By responsibly pursuing further reductions in U.S. nuclear forces and scaling back plans for new and excessively large strategic nuclear weapons systems and warhead production facilities, the United States can help close its budget deficit. And by reducing the incentive for Russia to rebuild its arsenal, these budget savings will make America safer and more secure.

Please sign Rep. Markey’s letter calling on the Super Committee to increase U.S. security by reducing spending on outdated and unaffordable nuclear weapons programs.

Sincerely,*

Joni Arends, Executive Director,

Concerned Citizens for Nuclear Safety

David C. Atwood, Former Director and Representative

for Disarmament and Peace Quaker United Nations Office, Geneva

Mavis Belisle, Coordinator

JustPeace

Peter Bergel, Executive Director

Oregon PeaceWorks

Harry C. Blaney III, Senior Fellow, National Security Program

Center for International Policy

Beatrice Brailsford, Nuclear program director

Snake River Alliance, Idaho

Jay Coghlan, Executive Director

Nuclear Watch New Mexico

David Culp, Legislative Representative

Friends Committee on National Legislation (Quakers)

Jenefer Ellingston

Green Party delegate

Matthew Evangelista, President White Professor of History and Political Science

Cornell University

Honorable Don M. Fraser

Former Member of Congress from MN

Susan Gordon, Director

Alliance for Nuclear Accountability

Lt. Gen. Robert Gard, USA, Ret., Chairman

Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

Jonathan Granoff, President

Global Security Institute

Ambassador Robert Grey

Former US Representative to the Conference on Disarmament

Don Hancock, Director, Nuclear Waste Program

Southwest Research and Information Center

William D. Hartung, Director, Arms and Security Project

Center for International Policy

Katie Heald, Coordinator

Campaign for a Nuclear Weapons Free World

Ralph Hutchison, Coordinator

Oak Ridge Environmental Peace Alliance

John Isaacs, Executive Director

Council for a Livable World

Marylia Kelley, Executive Director

Tri-Valley CAREs, Livermore

Daryl Kimball, Executive Director

Arms Control Association

Kevin Knobloch, President

Union of Concerned Scientists

Honorable Mike Kopetski

Former Member of Congress from OR

Don Kraus, Chief Executive Officer

Citizens for Global Solutions

David Krieger, President

Nuclear Age Peace Foundation

Hans M. Kristensen, Director, Nuclear Information Project

Federation of American Scientists

Jan Lodal

Former Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy

Paul Kawika Martin, Political Director

Peace Action (formerly SANE/Freeze)

David B. McCoy, Executive Director

Citizen Action New Mexico

Mark Medish

Former NSC Senior Director

Marian Naranjo, Director

Honor Our Pueblo Existence (H.O.P.E.)

Sister Dianna Ortiz, OSU, Deputy Executive Director

Pax Christi USA

Christopher Paine, Nuclear Program Director

Natural Resources Defense Council

Bobbie Paul, Executive Director

Georgia WAND

Jon Rainwater, Executive Director

Peace Action West

Taylor Reese

Pax Christi USA

Susan Shaer, Executive Director

Women’s Action for New Directions

Karen Showalter, Executive Director

Americans for Informed Democracy

Nancy E. Soderberg, former Ambassador to the United Nations

and Deputy National Security Advisor

David C. Speedie, Director, U.S. Global Engagement Program

Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs

Carla Mae Streeter, OP

Aquinas Institute of Theology

Ann Suellentrop, Director

Physicians for Social Responsibilities-KC

Gerald Warburg, Professor of Public Policy

and co-author of arms control initiatives

Paul Walker, Director, Security and Sustainability

Global Green USA

Peter Wilk, MD, Executive Director

Physicians for Social Responsibility (PSR)

Michael J. Wilson, National Director

Americans for Democratic Action

James E. Winkler, General Secretary

General Board of Church and Society

The United Methodist Church

=====================

*Organizations listed for affiliation purposes only

2012 Nuclear Security Summit in Seoul: Achieving Sustainable Nuclear Security Culture

By Igor Khripunov

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), nuclear security culture is “the assembly of characteristics, attitudes and behavior of individuals, organizations and institutions which serves as a means to support and enhance nuclear security.”[1] The concept of security culture emerged much later than nuclear safety culture, which was triggered by human errors that led to the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents. Much as these incidents confirmed the importance of nuclear safety, security culture has gained acceptance as a way to keep terrorist groups from acquiring radioactive materials and prevent acts of sabotage against nuclear power infrastructures. Safety and security culture share the goal of protecting human lives and the environment by assuring that nuclear power plants operate at acceptable risk levels.

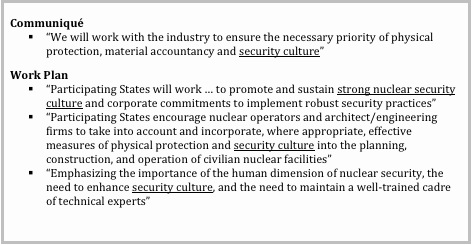

The 2010 Nuclear Security Summit held in Washington, DC, emphasized the importance of culture as a critical contributing factor to nuclear security:

Using Enrichment Capacity to Estimate Iran’s Breakout Potential

While diplomats and officials claim Iran has slowed down its nuclear drive, new analysis shows that Iran’s enrichment capacity grew during 2010 and warns against complacency as five world powers resume talks.

New START Delay: Gambling With National and International Security

|

| A few Senators are preventing US inspectors from verifying the status of Russian nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The ability of a few Senators to delay ratification of the New START treaty is gambling with national and international security.

At home the delay is depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about the status and operations of Russian strategic nuclear forces. And abroad the delay is creating doubts about the U.S. resolve to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, doubts that could undermine efforts to limit proliferation.

New START may not be the most groundbreaking treaty ever, but it is a vital first step in moving U.S.-Russian relations forward and paving the way for additional nuclear reductions and nonproliferation efforts. Essentially all current and former officials and experts recommend verification of New START, and after more than 20 hearings and nearly 1,000 detailed questions answered it is time for the Senate to ratify the treaty.

Important Inspections

Ratification would set in motion a wide range of data exchange and on-site inspection activities. By delaying ratification, the Senators are depriving the U.S. intelligence community important information about Russian nuclear forces. Apart from monitoring how Russian strategic nuclear forces are evolving and operating, the information is important to avoid worst-case threat assessments that can negatively affect U.S.-Russian relations.

It has now been 348 days since the last U.S. inspection team left Russia.

During the 15 years the START Treaty was in effect between 1994 and 2009, U.S. teams conducted 659 inspections of Russian nuclear weapons facilities; Russian conducted 481 inspections of U.S. facilities.

The last U.S. on-site inspection took place on November 18-19, 2009, at an SS-25 mobile missile base near Teykovo, approximately 130 miles (210 km) northeast of Moscow.

.

That inspection had special meaning because the SS-25 is being phased out from this area and replaced with the new SS-27. While each SS-25 is equipped with one warhead, the SS-27 comes in two versions: one with a single warhead and one with three warheads. The U.S. intelligence community calls the latter the SS-27 Mod 2, while the Kremlin named it RS-24 so as to avoid conflict with the now expired START treaty.

One of the four bases at Teykovo has already been equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2, two still have the SS-25, while the fourth base has been emptied and might be converting to the newer missile. Within the next decade, all four bases may be equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2.

The Russians chose Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri for their final on-site inspection in the United States. That inspection took place on December 1-2, 2009, just two days before the treaty expired.

| B-2 of the 509th Bomb Wing over Whiteman AFB |

|

| Russia chose the B-2 base at Whiteman Air Force Base as its final inspection in the United States under the now expired START treaty. |

.

The Nonproliferation Gamble

From the outset, the Obama administration appears to have seen Russia as the main potential obstacle to the treaty, rather than the U.S. Senate. Absent a strategy to secure the votes for ratification early on, the tables have now turned; with the White House desperate to secure ratification, a few Senators who still see Russia through Cold War lenses have effectively managed to use hearings and voting rules to extort concessions (read: money) from the administration to modernize the nuclear weapons production complex and delivery systems.

| Senator Jon Kyl |

|

| A few senators, most prominently Senator Jon Kyl (R-Arizona), have managed to delay ratification of the New START treaty. |

.

The administration quickly agreed to boost the FY 2011 budget for the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) well above the FY 2010 level. But that didn’t satisfy the Senators. So when Congress was unable to approve the budget before the mid-term election, the administration agreed that a Continuing Resolution (CR) designed to keep federal agencies operating at FY2010 budget levels through December 3rd would include an exemption for NNSA’s weapons program to fund the agency at the higher FY 2011 budget request – about $7 billion or an additional $625 million. But since the provisions in the defense appropriations bill and report don’t apply to the CR, the appropriators have lost control of how the funds are used; Congress is basically providing NNSA with a blank check to spend the $7 billion.

In addition, in an effort to buy the Senators’ votes for ratification during the “lame duck” session before the new Congress begins, the administration has offered $600 million more for the FY 2012 NNSA budget above FY 2011 levels, as well as an additional $3.6 billion spread out over FY 2013-2016.

Altogether, in a nuclear spending spree that would have been inconceivable during the Bush administration, the Obama administration plans to spend well over $180 billion to modernize nuclear weapons delivery systems and production facilities over the next decade.

There is a real risk that in the coming years, this modernization could backfire and undermine the second pillar of U.S. nuclear policy: strengthening nonproliferation.

The reason is simple: U.S. nonproliferation efforts dependent upon international support, but if the international community sees the increased nuclear modernizations as contradicting the U.S. pledge to work toward nuclear disarmament, some countries may well decide not to support the administration’s nonproliferation agenda.

This risk could be compounded later this week if NATO approves a new Strategic Concept that reaffirms the importance of nuclear weapons – and fails to order the withdrawal of the remaining tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

The Senate needs to demonstrate that it understands that the Cold War is over and that it cares more about national and international security than politics by ratifying the New START treaty before Christmas. And the administration must be careful to balance its nuclear modernization plans with the need to sustain the vision of nuclear disarmament that so inspired the international community just 18 months ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Fuel Deal with Iran: Getting Back to Basics

by Ivanka Barzashka

After a year-long stalemate, Iran and the P5+1 seem to have agreed on a day for holding political talks – December 2. Iran’s Foreign Ministry spokesman confirmed last week that the meeting “will not include discussions on fuel swap” – the deal with France, Russia and United States, also known as the Vienna Group, to refuel the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR).

In principle, both Washington and Tehran agree that the fuel deal is still on the table, but the Iranians have been critical of the delay in setting a date for talks, which they interpret could be a lack of “willingness to enter peaceful nuclear cooperation.”

A successful fuel deal is a necessary condition for further engagement. However, circumstances have changed since October 2009, when the Vienna Group first made the fuel offer. Now, the State Department maintains that “any engagement [should be] in the context of that changed reality.” (Most of the Vienna Group’s outstanding concerns were listed in a confidential document to the IAEA, published by Reuters on June 9.)

However, the alleged terms of Washington’s new proposal seem to be muddled and will not have the claimed threat-reduction benefits (for a detailed discussion, see this Oct 29 post.) A technically-grounded analysis of what the fuel deal today can, cannot and ought to achieve is available in “New fuel deal with Iran: Debunking common myths,” published on Nov 2 in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Some highlights of these two assessments are provided below. (more…)

Iran Fuel Negotiations: Moving Muddled Goalposts

by Ivanka Barzashka and Ivan Oelrich

A year ago, France, Russia and the U.S.—called the Vienna Group—proposed a deal in which Iran would ship out some of its worrying low-enriched uranium (LEU) in exchange for fuel for its medical isotope reactor, called the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). These narrow technical discussions about the TRR were meant to serve as a confidence-building effort. The negotiations fell apart because of differences about timing of the exchange of material, but they may be about to restart. A year later, the facts on the ground have changed. These new circumstances may call for new negotiating terms, but changes have to make some sense. Calculations show that numbers recently floated by the State Department seem ad hoc and arbitrary and will not have the touted threat-reduction benefits.

On October 27, The New York Times reported that a senior U.S. official believed that the Vienna Group were “very close to having an agreement” on how the original fuel swap offer, made in October 2009, should be changed. One of the new terms would be an increase in the amount of LEU provided from 1,200 kg to 2,000 kg. The State Department explained a day later that “the proposal would have to be updated reflecting ongoing enrichment activity by Iran over the ensuing year.” Iran’s larger LEU stockpile changes Washington’s threat-reduction calculus, which ultimately undermines the confidence-building aspect of the deal.

Another new circumstance is Iran’s production of 20 percent enriched uranium, ostensibly to produce TRR fuel domestically. This is a worrying development because, compared to LEU, a stockpile of 20 percent material would cut by half Iran’s time to a bomb.

Iran’s New Dual Track: A Challenge to Negotiations?

by Ivanka Barzashka and Thomas M. Rickers

Coaxed by Turkey and Brazil, Iran seems to be actively pursuing fuel talks. France, Russia and the U.S. (also known as the Vienna Group) claim that they, too, are interested in a deal, even as the U.S. and EU passed their own tougher sanctions against the Islamic Republic as part of a dual-track approach. Now Tehran may even be willing to address what was once the major hindrance to a deal: its 20 percent enrichment. Yesterday, Ali Akbar Salehi, Iran’s atomic energy head, said his country “will not need to enrich to 20 percent if [their] needs are met.” And yet on July 18, the Majlis passed a law requiring the government to continue 20 percent enrichment and manufacture own fuel, which is an apparent contradiction to negotiations for foreign fuel supply. Clearly, Iran is sending mixed messages. But does this mean there is an internal disagreement about nuclear policy? Or is Iran not serious about a fuel deal? (more…)

Will Iran Give Up Twenty Percent Enrichment?

|

by Ivanka Barzashka

In response to sanctions, Iran’s parliament adopted the Nuclear Achievement Protection Bill on July 18. Among other things, the law requires the government to continue 20 percent enrichment and provide fuel for the Tehran Research Reactor (TRR). Although this aspect of the legislation has largely fallen below the news radar, it raises important questions about the future of nuclear talks, which Iran has postponed until September as “punishment” of the West.

Iran says it is enriching to higher concentrations to manufacture its own fuel for the TRR, but a stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium will reduce by more than half Iran’s time to a bomb (when compared to its current stockpile of 3.5 percent LEU). Now Iran’s higher-level enrichment may have become the connection between sanctions and a fuel deal that will hinder any engagement options. However, there is still time to explore resolutions to the impasse.

Ivan Oelrich and I have co-authored an FAS issue brief that traces the history of Iranian higher-level enrichment efforts in an effort to understand Tehran’s nuclear intentions. We were driven by the question: Will Iran, at this stage, give up twenty percent enrichment? Three distinct periods were analyzed: (1) from the beginning of 20 percent enrichment to the Tehran Declaration, (2) from the Tehran Declaration to the passing of UN sanctions, and (3) after sanctions. (more…)

Will Iran Give Up Twenty Percent Enrichment

Since February 2010, Iran has been enriching uranium to concentrations of 20 percent U-235. A stockpile of 130 kg of 20 percent enriched uranium would reduce, by more than half, Iran’s time to develop a bomb. A key unknown is whether Tehran will stop the higher enrichment and, if so, under what circumstances.