B61-12: NNSA’s Gold-Plated Nuclear Bomb Project

Escalating cost estimates for the B61 Life- Extension Program threaten to make the new B61-12 bomb the most expensive ever.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The disclosure during yesterday’s Senate Appropriations Subcommittee hearing that the cost of the B61 Life Extension Program (LEP) is significantly greater that even the most recent cost overruns calls into question the ability of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to manage the program and should call into question the B61 LEP itself.

If these cost overruns were in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

At the hearing yesterday, Senator Dianne Feinstein revealed that NNSA recently told her that the $4 billion cost estimate they provided in the FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan was too low and that they would need $4 billion more to complete the program. Two months ago I reported that the cost had increased to $6 billion.

NNSA’s new cost estimate is already being challenged, this time by the Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) office, which only a few days ago increased the estimate by another $2 billion to a whopping $10 billion.

But get this: the already too high B61 LEP cost estimate does not include other pricy elements of the B61 modernization program. In addition to the LEP itself comes a new guided tail kit assembly that the Air Force is developing to increase the accuracy of the B61. The cost estimate for that tail kit has recently increased by 50 percent from $800 million to $1.2 billion.

Add to that the cost of equipping the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter with the capability to carry the new weapons, recently estimated at around $340 million. If the LEP and tail kit increases mentioned above are any indication, however, then the cost of equipping the F-35 with nuclear capability is also likely to increase.

The escalating costs may eventually make the B61 LEP the most expensive nuclear weapons program (per warhead unit) in the U.S. arsenal. Already the projected B61 LEP cost far exceeds the cost of the W76 LEP, which probably involves three times as many warheads as will produced by the B61 LEP. As Nick Roth points out, the new $10 billion estimate is equivalent to two-thirds of what NNSA planned to spend on life extending all the other warhead types in the US arsenal over the next twenty years!

The precise number of B61-12 planned is still a secret. My take currently is around 400. If so, that would mean each B61-12 bomb would cost $28 million (including cost of tail kit).

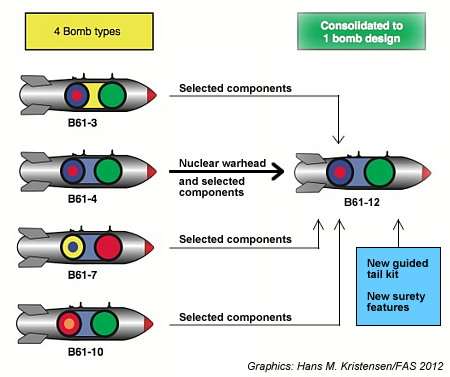

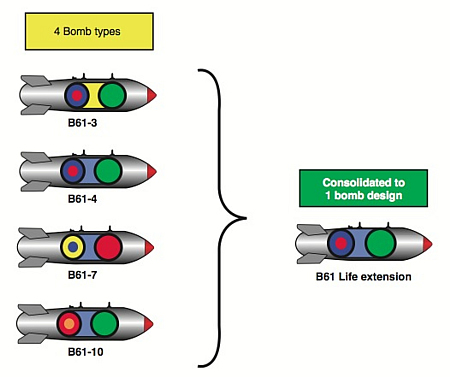

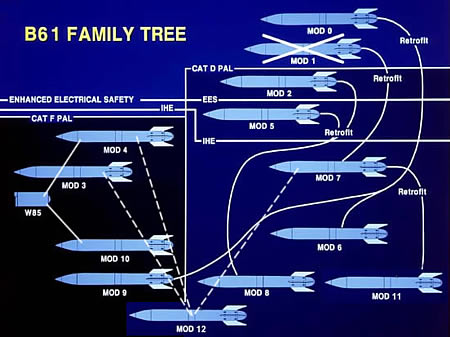

Because of the way the B61 LEP has been presented, many have the impression that the program will life-extend all four versions of the B61. In reality, only one of the four versions will be life-extended: the B61-4. It may cannibalize components from the other three (B61-3/7/10), but the heart of the new B61-12 is the B61-4 nuclear explosive package. Instead of the simple chart that STRATCOM has been circulating, the following chart more accurately illustrates the process:

Rather than a B61 life-extension program that consolidates four bombs into one, the B61 LEP should more accurately be described as a life-extension of the B61-4 that incorporates selected non-nuclear components from three other B61 versions that will be retired with new surety features and a new guided tail kit assembly.

Implications and Recommendations.

The fact that the B61-12 will use the B61-4 nuclear explosive package obviously limits the number of B61-12s that can be built to the number of B61-4 that were originally produced. That number is about 660. But most of those have been retired and only about 200 are thought to be left in the DOD stockpile. If B61-12 production is to exceed 200, then it would have to also use warheads from retired B61-4s. Given that the B61-12 will not be carried on the B-52 bomber, that B-2 bombers are probably not allocated a maximum load of weapons (they also carry others), and that the stockpile in Europe is likely to decrease within the next decade, it seems reasonable to assume a B61-12 stockpile of around 400 weapons. But the number is secret – not because it matters to national security but because it is nuclear.

The escalating cost of the B61 LEP adds to NNSA’s abysmal record of underestimating costs of nuclear weapons programs. It follows enormous budget overruns of the National Ignition Facility (NIF) at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement – Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) at the Y-12 National Security Complex at Oak Ridge in Tennessee.

As mentioned above, if these cost overruns happened in the private sector, heads would roll and the program would probably be canceled.

Apart from poor planning, the B61 LEP cost escalation is probably also fueled by planners that appear to be drunk on promises of increased nuclear funding and political commitments to nuclear modernization. The result is an overly ambitious program that instead of doing basic life-extension of existing designs is trying to add exotic features and components to the weapon that was originally tested. And the planned B61-12 is not even the most ambitious version the planners had asked for (they were not allowed to add multi-point safety and optical firing sets), which would have been even more expensive.

If poor planning is not the reason, then NNSA must be working under the assumption that costs should be underestimated when seeking initial program approval from Congress because the taxpayers will have to pay for the cost increase later on anyway. To her credit, Senator Feinstein is pushing for greater program control and told Aviation Week that the cost escalation will trigger additional congressional scrutiny. “We have to find a way to stop this from happening. …We’ve asked that we receive monthly reports, that one person be put in charge. … The purpose of that is to make people solve problems quickly, before they are left and they just continue to grow.”

The B61 LEP is not the only or necessarily most complex LEP on the horizon. NNSA and DOD are already planning the W78 LEP and envision building a “common” warhead that can be used on both ICBMs and SLBMs. Such a warhead is not currently in the stockpile. Although the design is still being worked out, it could combine W78 and W88 features and use a plutonium pit from a third warhead – the W87. If you’re worried about B61 LEP costs, just wait for the W78 LEP! Is Congress prepared to authorize $10 billion-plus per exotic LEP versus more basic LEPs?

But apart from money, the escalating B61 LEP costs must also raise questions about the importance of the mission. While the strategic mission on the B-2 strategic bomber is probably not in doubt, the non-strategic mission certainly should be. Under current plans, the B61-12 will be fitted onto four tactical aircraft – F-15E Strike Eagle, F-16 Falcon, F-35A Lightning and PA-200 Tornado. There are no important or urgent threats that require the United States to equip all these tactical aircraft with the new bomb. But the modernization will increase the military capability of NATO’s nuclear posture, not exactly in sync with the pledges from the White House and NATO to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and not increase military capabilities during LEPs.

And the few NATO officials that have either misunderstood their security requirements or been lobbied by nuclear cold warriors to support continued deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe need to be debriefed – or asked to pay their share. That would certainly end the deployment quickly.

Whatever the best way forward, the U.S. should phase out its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons, delay and redesign the B61 LEP, and focus its resources on maintaining the strategic nuclear weapons and conventional forces that are actually needed for U.S. and allied security in the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO’s Nuclear Groundhog Day?

|

| At the Chicago Summit NATO will once again reaffirm nuclear status quo in Europe |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Does NATO have a hard time waking up from its nuclear past? It would seem so.

Similar to the movie Groundhog Day where a reporter played by Bill Murray wakes up to relive the same day over and over again, the NATO alliance is about to reaffirm – once again – nuclear status quo in Europe.

The reaffirmation will come on 20-21 May when 28 countries participating in the NATO Summit in Chicago are expected to approve a study that concludes that the alliance’s existing nuclear force posture “currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” [Update May 20, 2011: Turns out I was right. Here is the official document.]

In other words, NATO will not order a reduction of its nuclear arsenal but reaffirm a deployment of nearly 200 U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs in Europe that were left behind by arms reductions two decades ago.

Visions Apart?

Although no one expected NATO to simply disarm, the reaffirmation of the current nuclear posture nonetheless falls far short of the visionary and bold initiatives that U.S. and Russian presidents took twenty year ago when they ordered sweeping reductions – and eliminations – of entire classes of non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and around the world at the time.

President George W. Bush followed up by unilaterally reducing the remaining U.S. inventory in Europe by more than 50 percent, and president Barack Obama reinvigorated arms control and disarmament aspirations around the world when he declared in Prague in 2009 that he would reduce the role of nuclear weapons to put and end to Cold War thinking. He started by ordering the unilateral retirement of the Tomahawk sea-launched land attack cruise missile – completing the elimination of all U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons from the navy, whose warships just two decades ago brought non-strategic nuclear weapons to all corners of the world.

Since then, current and former officials have been busy attaching preconditions to further reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons. The venue for these efforts was NATO’s new Strategic Concept adopted in November 2010, which broke with two decades of unilateral reductions and decided that any further reductions of NATO forces must take into account the disparity with Russia’s larger inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons. Why NATO suddenly needs to care so much about Russia’s aging and declining inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons makes little sense.

Yet the Strategic Concept also promised that NATO would “seek to create the conditions for further reductions in the future” and, ultimately, “create the conditions of a world without nuclear weapons….”

Creating Conditions

So how will NATO create the conditions for further reductions and a world without nuclear weapons? The seven-page Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) report to be released in Chicago (yes, the document will be made public) repeats this promise, but the short answer is: not by reducing forces but by studying it some more.

To that end, according to official sources, the DDPR will ask the North Atlantic Council (NAC) to task its committees to “develop concepts for how to ensure the broadest possible participation of Allies concerned [note: the DDPR identifies the “Allies concerned” as the members of the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) – which is everyone except France] in their nuclear sharing arrangements, including in case NATO were to decide to reduce its reliance on non-strategic nuclear weapons based in Europe.” (Emphasis added).

So there appears to be some intent to reduce reliance on non-strategic nuclear weapons and adjust NPG procedures accordingly. But the DDPR also echoes the Strategic Concept formally making further reductions conditioned on Russian reductions:

“NATO is prepared to consider further reducing its requirement for non-strategic nuclear weapons assigned to the Alliance in the context of reciprocal steps by Russia, taking into account the greater Russian stockpiles of non-strategic nuclear weapons stationed in the Euro-Atlantic Area.” (Emphasis added).

Creating Obstacles

But one of the problems with using words such as “disparity” and “reciprocity” is that it is unclear what they mean and NATO has yet to explain it. For example, how much disparity is acceptable? No one expects NATO to seek parity in non-strategic nuclear weapons with Russia, so at what level does continued disparity become acceptable?

And what kinds of forces are counted when NATO talks disparity? Russia’s estimated inventory of air-delivery weapons is only a little greater than that of the United States (730 versus 500), so disparity is not significant in that weapons category. And while the Russian air-delivered weapons are stored separate from their bases, nearly 200 U.S. bombs in Europe are stored at the bases, inside aircraft shelters, a few feet below the wings of operational aircraft.

Likewise, most of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are in categories where NATO and the United States have none because they no longer needed them: naval weapons, air-defense weapons, and short-range ballistic missiles. No one expects NATO to argue that it needs such non-strategic nuclear weapons as well or that Russia must eliminate what it has in those categories. So does NATO’s concern over “disparity” not include those categories or does it?

The asymmetric composition of the non-strategic nuclear arsenals is one reason why it seems unclear (at best) why NATO would be able to “trade” an offer to reduce or withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe for Russian reductions in its non-strategic nuclear weapons. Most of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons don’t exist because of U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe but to compensate for what Russia sees as NATO’s conventional superiority. So unless NATO reduces its conventional anti-submarine warfare capability, why would it expect Russia to agree to reduce or eliminate its non-strategic nuclear anti-submarine weapons?

It is simple questions like these that indicate that NATO hasn’t thought through what it means when it says that further reductions must take disparity and reciprocity with Russia into account. The DDPR to some extent acknowledges this by ordering NAC to task its committees to “develop ideas for what NATO would expect to see in the way of reciprocal Russian actions to allow for significant reductions in the forward-based non-strategic nuclear weapons assigned to NATO.” One would image that NATO had identified what it wanted from Russia before it started using “disparity” and “reciprocity” as conditions for additional reductions.

Looking Ahead

Despite the reaffirmation of nuclear status quo and other weaknesses in the DDPR, it seems that a process has been started. The Strategic Concept cleaned out most of the language that in the previous version explicitly identified the importance of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe, and the DDPR now tasks the NAC to figure out what it would look like if NATO reduced reliance on the weapons.

But while the NATO bureaucrats cautiously consider the next round of opportunities and definitions, modernization of the nuclear posture with the more accurate B61-12 bomb and stealthy F-35 aircraft is moving ahead to improve the military capabilities of NATO’s nuclear arsenal. This undercuts the pledge to create the conditions for further reductions and a world free of nuclear weapons.

To avoid that Chicago will be seen as a nuclear arms control disappointment and NATO as a military dinosaur incapable of shedding its Cold War non-strategic nuclear armor, it is essential that NATO announces new initiatives on limiting and eliminating non-strategic nuclear weapons quickly after Chicago.

The bureaucrats cannot deliver this; it requires presidential leadership. And that’s what’s missing in Chicago: the boldness that characterized earlier unilateral initiatives. The DDPR is ironically a more cautious document produced under far less threatening circumstances. Bold reductions have been reduced to a promise to develop confidence-building and transparency measures to increase mutual understanding of NATO and Russian non-strategic weapons in Europe. That’s nice and needed, but it doesn’t make the cut.

Rather than spending yet another decade thinking about how to adjust the role of nuclear weapon in Europe, NATO needs to move quickly on a next round of non-strategic nuclear arms reductions. Instead of getting lost in “disparity” and “reciprocity,” NATO should set the pace and announce its decision to withdraw the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe and call on Russia to follow suit with its own initiatives. Doing so would create room to maneuver for moderates in Moscow and deny hardliners (in the Kremlin as well as in Brussels) the excuse to stall the process of reducing non-strategic nuclear weapons. Otherwise 2022 will be NATO Nuclear Groundhog Day all over again.

Additional Information: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons report, May 2012 | NATO DDPR 2012

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61 Nuclear Bomb Costs Escalating

|

| The expected cost of the B61 Life-Extension Program has increased by 50 percent to $6 billion |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The expected cost of the B61 Life-Extension Program (LEP) has increased by 50 percent to $6 billion dollars, according to U.S. government sources.

Only one year ago, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) estimated in its Stockpile Stewardship and Management Program report to Congress that the cost of the program would be approximately $4 billion.

The escalating cost of the program – and concern that NNSA does not have an effective plan for managing it – has caused Congress to cap spending on the B61 LEP by 60 percent in 2012 and 100 percent in 2013. The Pentagon’s Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) office is currently evaluating NNSA’s cost estimate and is expected to release its assessment in July. After that, NNSA is expected to release a validated cost, schedule and scope estimate for the B61 LEP, a precondition for Congress releasing the program funds for Phase 6.3 of the program.

Ambitious Program

Beyond mismanagement, the 50 percent increase is due to the ambitious modifications that NNSA, the nuclear laboratories, and the Pentagon say are needed to extend the life of the bomb.

That includes new use-control and safety features to increase the surety of what is already the most safe warhead design in the stockpile. Several warhead design options were proposed, ranging from a simple life-extension with the current features to a significantly altered design with new optical wiring and multi-point safety. The Nuclear Weapons Council in December chose the second-most ambitious design without optical wiring and multi-point safety.

Expectation for the ambitious B61-12 program has already spawned a hiring frenzy at Sandia National Laboratory for a program that dwarfs the W76 LEP, the ongoing production of one of the navy’s Trident missile warheads. “It is the largest effort in more than 30 years, the largest, probably, since the original development of the B61-3,4,” according to the head of the B61 LEP at Sandia.

Program Justification

The Pentagon is promoting the consolidation of four B61 versions into the B61-12 as an effort to increase efficiency and lowering costs. But we have yet to see the budget justification for that and it is not clear how much of the savings will come from consolidation or from simply reducing the overall number of B61s in the stockpile. Already the consolidation part is turning out to be much more expensive than we were led to believe.

The B61 LEP was catapulted forward by the April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which committed – before a validated cost, schedule and scope estimate had been developed – the United States to conduct a “full scope” B61 LEP. That commitment came as part of a “deal” that promised significant investments in nuclear weapons modernization in return for Congressional approval of the New START treaty.

The Mission

The administration says that the B61 LEP is needed to provide nuclear extended deterrence to NATO allies and to continue a gravity bomb capability on the B-2 stealth bomber. According to the U.S. Air Force, the B61-12 is “critical” to “deterrence of adversaries in a regional context, and support of our extended deterrence commitments.”

But privately, U.S. Air Force officials do not see a need to continue the deployment in Europe, where the United States currently deploys nearly 200 B61-3/4 bombs in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries. And although the NATO Summit later this month is expected to endorse – for now – continuation of the current nuclear posture in Europe, none of the European allies appear to be willing to pay for continuing the mission.

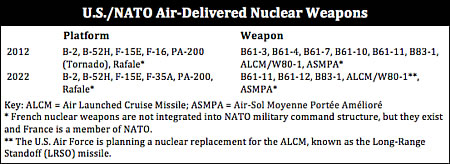

Extended deterrence can be provided with other means and the B61-12 is not the only U.S. air-delivered nuclear weapon system. Indeed, the U.S. Air Force currently has seven different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different delivery platforms. After completion of the B61-12 program, the Air Force will still have four different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different aircraft.

|

| The U.S. Air Force has six different nuclear weapons for delivery by five different aircraft. After the B61 LEP it will still have four weapons for five aircraft. |

.

Why so many different ways of delivering a nuclear weapon from the sky is needed for deterrence is anyone’s guess. The nuclear redundancy in the bomber leg is significantly greater than for ICBMs and SLBMs and appears to be the result of a combination of a left-over Cold War mission in Europe and requirements developed by warfighters to hold a variety of targets at risk in a variety of different ways.

Conclusions

After having spent hundreds of millions of dollars between 2006 and 2010 on extending the service life of the secondary of the B61-7 (and adding new spin-rocket motors to improve performance), NNSA and DOD are now planning to scrap the weapon and replace it with the $6 billion B61-12.

Although the cost estimate of the B61 LEP has increased by 50 percent over the past year, the $6 billion price tag is only part of the cost. The new guided tail kit the Air Force is developing to increase the accuracy of the B61-12 is expected to cost about $800 million. And the cost of making the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter capable of delivering the bomb is estimated to add another $340 million.

|

| After having spent hundreds of millions of dollars on refurbishing the B61-7, NNSA now plans to scrap the weapon and replace it with the B61-12. |

.

The anticipated cost of the B61-12 program is now greater than the high-end cost estimate for the CMRR-NF, the plutonium pit production factory planned at Los Alamos that the Senate recently decided to mothball for at least five years due to its high cost. Or if that is not impressive enough, the cost of the B61 LEP is comparable to what NNSA plans to spend on sustaining the entire active stockpile for the next decade.

This level of nuclear cost increase and mismanagement is neither justifiable nor sustainable. It shouldn’t be normally, but it certainly isn’t in the current financial crisis. And all of this to sustain a nuclear deployment is Europe that may well end before the B61 LEP is completed and a nuclear capability on the B-2 bomber that already carries another nuclear bomb.

The current B61-12 program should be stopped and reassessed to reduce cost and scope. Congress has already asked the JASONs to examine the scope of the program and provide an assessment of any major concerns. In the meantime, the mission in Europe should temporarily be sustained with a much more basic life-extension program while the administration works to convince NATO to agree to a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The nuclear capability of the B-2 bomber should be limited to what it already carries.

See also report: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

On May 20-21, 28 NATO member countries will convene in Chicago to approve the conclusions of a year-long Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR). Among other issues, the review will determine the number and role of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and how NATO might work to reduce its nuclear posture as well as Russia’s inventory of such weapons in the future.

Lack of transparency fuels mistrust and worst-case assumptions and the concerns some eastern NATO countries have about Russia have been used to prevent a withdrawal of the remaining U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe. The DDPR is expected to endorse the current deployment in Europe.

A new FAS report (PDF) concludes that non-strategic nuclear weapons are neither the reason nor the solution for Europe’s security issues today but that lack of political leadership has allowed bureaucrats to give these weapons a legitimacy they don’t possess and shouldn’t have.

Panel Discussion at Brookings on NATO Nukes

Steve Pifer was kind enough to invite me to participate in a panel discussion at the Brookings Institution about NATO’s nuclear future and the issue of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Alliance’s current Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR).

Steve presented his excellent paper NATO, Nuclear Weapons and Arms Control, Frank Miller, who has been involved in these issue before I could tie my shoe laces, took the “keep US nukes in Europe,” while I argued for the withdrawal of the weapons. Angela Stent moderated the panel.

I’m not yet clear if they’re planning to post a transcript or video, so in the meantime here are my prepared remarks: NATO’s Posture Review and Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons.

For my writings on this blog about NATO nuclear policy issues, go here.

See also recent letter to NATO Secretary General Ander Fogh Rasmussen coordinated by ACA and and BASIC and signed by two dozen nuclear experts and former senior government officials.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

|

| The US military is planning to replace the tail section of the B61 nuclear bomb with a new guided tail kit to increase the accuracy of the weapon. This will increase the targeting capability of the weapon and allow lower-yield strikes against targets that previously required higher-yield weapons. Image: FAS Illustration |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal.

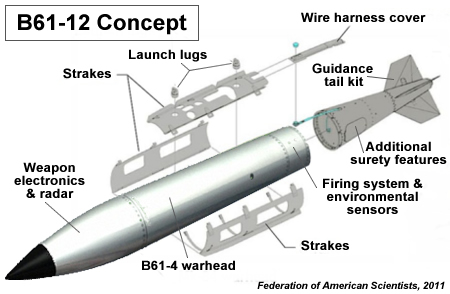

The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy.

As a result, if funded by Congress, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with a significantly enhanced capability to knock out military targets.

Add to that the stealthy capability of the new F-35 aircraft being built to deliver the new weapon, and NATO is up for a significant nuclear upgrade.

The upgrade would also improve the capability of U.S. strategic bombers to destroy targets with lower yield and less radioactive fallout, a scenario that resembles the controversial PLYWD precision low-yield nuclear weapon proposal from the 1990s.

Finally, the B61-12 will mark the end of designated non-strategic nuclear warheads in the U.S. nuclear stockpile, essentially making concern over “disparity” with Russian non-strategic weapons a non-issue.

The Obama administration and Congress should reject plans to increase the accuracy of nuclear weapons and instead focus on maintaining the reliability of existing weapons while reducing their role and numbers.

Increasing Military Capabilities

It is U.S. nuclear policy that nuclear weapons “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.” According to this policy stated in the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), the B61-12 cannot have new or greater military capabilities compared with the weapons it replaces.

Yet a new report published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reveals that the new bomb will have new characteristics that will increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

It is important at this point to underscore that the official motivation for the new capabilities does not appear to be improved nuclear targeting against Russia or other potential adversaries. Nonetheless, that will be the effect.

The GAO report describes that the nuclear weapons designers were asked to “consider revisions to the bomb’s military performance requirements” to accommodate both non-strategic and strategic missions. This includes equipping the B61-12 with a new guided tail kit section in an $800 million Air Force program that is “designed to increase accuracy, enabling the military to achieve the same effects as the older bomb, but with lower nuclear yield.”

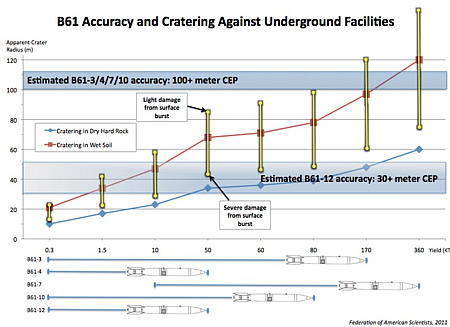

The B61 LEP consolidates four existing B61 types (non-strategic B61-3, B61-4 and B61-10, as well as the strategic B61-7) into one, so the new B61-12 must be able to meet the mission requirements for both the non-strategic and strategic versions. But since the B61-12 will use the nuclear explosive package of the B61-4, which has the lowest yield of the four types (a maximum of 50 kt), increasing the accuracy was added to essentially turn the B61-4 into a B61-7 in terms of targeting capability.

| Consolidating Four Bombs Into One |

|

| This STRATCOM slide used in the GAO report portrays the B61-12 as a mix of components from existing weapons. The message: it’s not a “new” nuclear weapon. But the slide is missing the most important new component: a new guided tail kit section that will increase the weapon’s accuracy. Image: STRATCOM/GAO |

.

The new guided tail kit – the B61 Tail Subassembly (TSA), as it is formally called – will be developed by Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing for the Air Force and similar to the tail kit used on the conventional Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bomb (Boeing has delivered more than 225,000 kits so far). But the B61-12 would be the first time a guided tail kit has been used to increase the accuracy of a deployed nuclear bomb.

The B61-12 accuracy is secret, but officials tell me it is similar to the tail kit on the JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition), which uses a GPS (Global Positioning System)-aided INS (Internal Navigation System). In its most accurate mode it provides the JDAM a circular error probable (CEP) of 5 meters or less during free flight when GPS data is available. If GPS data is denied, the JDAM can achieve a 30-meter CEP or less for free flight times up to 100 seconds with a GPS quality handoff from the aircraft. It is yet unclear if the B61-12 will have GPS, which is not hardened against nuclear effects, but many limited regional scenarios probably wouldn’t have sufficient radiation to interfere with GPS.

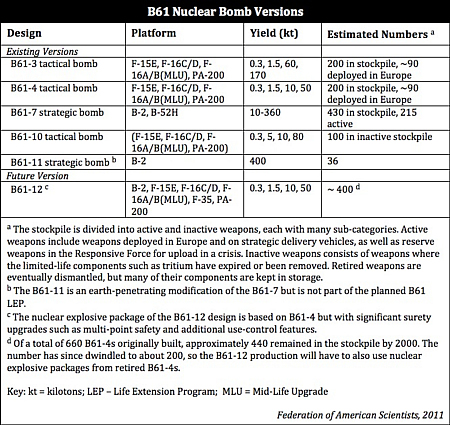

Officials explain that the increased accuracy will not violate the LEP policy in the NPR because the B61-12 will not have higher yield than the types it replaces. The B61-12 nuclear explosive package (NEP) will be based on the B61-4, which has the lowest maximum yield of the four types to be consolidated. The B61-7, in contrast, has a maximum yield of 360 kt (see table). But while B61-12 does not increase the yield of the B61-7, its guided tail kit will increase the targeting capability compared with the existing B61-3/4 and -10 versions.

|

| Click on chart to download larger version. |

.

Targeting Implications

Increasing the accuracy of the B61 has important implications for NATO’s nuclear posture and for nuclear targeting in general.

In Europe, the new guided tail kit would increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons assigned to NATO by giving them a target kill capability similar to that of the high-yield B61-7, a weapon that is not currently deployed in Europe.

This would broaden the range of targets that can be held at risk, including some capability against underground facilities. In addition, delivery from new stealthy F-35 aircraft will provide additional military advantages such as improved penetration and survivability.

Shock damage to underground structures is related to the apparent (visible) radius of the crater caused by the nuclear explosion. For example, according to the authoritative The Effects of Nuclear Weapons) published by the Department of Defense and Department of Energy in 1977, severe damage to “Relatively small, heavy, well-designed, underground structures” is achieved by the target falling within 1.25 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero (the point of detonation), and light damage is achieved by the target falling within 2.5 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero. For a yield of 50 kt – the estimated maximum yield of the B61-12, the apparent crater radii vary from 30 meters to 68 meters depending on the ground (see graph below). Therefore an improvement in accuracy from 100-plus meter CEP (the current estimated accuracy of the B61) down to 30-plus meter CEP (assuming INS guidance) improves the kill probability against these targets significantly by achieving a greater likelihood of cratering the target during a bombing run. Put simply, the increased accuracy essentially puts the CEP inside the crater.

.

The U.S. Department of Defense and NATO agreed on the key military characteristics of the B61-12 in April 2010 – the same month the NPR was published and seven months before NATO’s new Strategic Concept was approved. This included the yield options, that the B61-12 will have both midair and ground-burst detonation options, that it will be capable of freefall (but not parachute-retarded) delivery, and the required accuracy when equipped with the new guided tail section and employed by the F-35. STRATCOM, which provides targeting assistance to NATO, subsequently asked for a different yield, which U.S. European Command and SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) agreed to. Since the NPR prohibits increasing the military capability, STRATCOM’s alternative B61-12 yield cannot be greater than the current maximum yield of the B61-4.

The GAO report states that “neither NATO nor U.S. European Command, in accordance with the NATO Strategic Concept, have prepared standing peacetime nuclear contingency plans or identified targets involving nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added). The “no standing plans” claim is correct because regional nuclear strike planning is no longer done with “standing plans” as during the Cold War. But that doesn’t mean there are no plans at all. Today’s strike planning does not require “standing” plans but relies on new adaptive planning capabilities that can turn out a strike plan within days or weeks.

But the “no identified targets” claim raises an obvious question: If NATO and EUCOM have not “identified targets” for the B61 bombs in Europe, how then can they identify the military characteristics needed for the B61-12 that will replace the bombs in 2018? Obviously, some targets have been identified.

The addition of the tail kit eliminates the need for the existing parachute-retarded laydown option, where a parachute deployed from the rear of the nuclear bomb provides for increased accuracy when employed from an aircraft flying at very low altitude (and allows the pilot (and aircraft) to escape the blast). But a GPS/INS tail kit would also give the B61-12 high accuracy independent of release altitude, weather, and axis of aircraft for much greater survivability.

Reinventing PLYWD: Low-Yield Prevision Nuke

Beyond Europe, the guidance tail kit would also have implications for nuclear targeting in general. Although the B61-12 will not be able to exceed the target kill capability of the maximum yield of the B61-7, the increased accuracy will have an effect on the target kill capability at lower yields. Indeed, the B61-12 concept resembles elements of the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) program from the early-1990s when the Air Force studied combining low-yield warhead options with precision guidance to reduce collateral damage from nuclear strikes.

|

| Click on image to download report. |

.

Much of that study remains classified but parts of it were released to me under the Freedom of Information Act (see box). The study concluded that, “The use of precision guidance could permit the Air Force to accomplish some missions as effectively, or more effectively, with low-yield weapons” (emphasis added). Overall, the study found that a precision, low-yield weapon “can be effective against a large fraction of potential targets, can reduce collateral damage on a significant number of targets, is technically feasible, and can provide aircraft standoff (and thus improve survivability).”

PLYWD was rejected by Congress, which banned work on and development of new warheads with a yield of less than five kilotons. Among other things, Congress was concerned that the combination of precision and low-yield to reduce collateral damage would make nuclear weapons appear more useable and risk lowering the nuclear threshold and increase the risk that nuclear weapons would actually be used.

The issue resurfaced in 2001 with proposals to build low-yield nuclear earth penetrators, but the scenarios were shown to be inherently dirty (examples of analysis here, here, and here). Even so, the Bush administration managed to defeat the ban in 2003 in order to explore advanced concepts of nuclear strike options against regional adversaries (see CRS report for background).

The beauty of the B61-12 program is that it avoids a controversial decision to develop a new low-yield nuclear warhead but achieves many of the PLYWD mission goals by combining the existing lower-yield options of the B61 (down to only 0.3 kt) with the increased accuracy provided by the new guidance tail kit to increase targeting capability while reducing collateral damage.

Interestingly, the PLYWD project emerged after EUCOM (now a recipient of the B61-12) pressed for nuclear weapons with lower yields, Los Alamos National Laboratory (the design lab for the B61) proposed a mini-nuke concept, and the Defense Nuclear Agency (now Defense Threat Reduction Agency) began research on “a very low collateral effects nuclear weapons concept.” In fact, both the Military Characteristics (MC) and Stockpile-to-Target Sequence (STS) documents for PLYWD were based on the B61 MC and STS.

In the future, if funded by Congress, the precision B61-12 would allow a B-2, F-35, F-15E, F-16, as well as the next generation long-range bomber, to destroy targets, which previously required high yield blasts, with lower yields and less radioactive fallout.

The Nonproliferation Argument

The relatively lower yield of the B61-4 means that its secondary (CSA, or Canned Sub Assembly) contains less Highly-Enriched Uranium (HEU) that the B61-3, B61-7, and B61-10 versions. Using the B61-4 nuclear explosive package in the B61-12 to replace the three other higher-yield bombs will remove significant quantities of HEU from the deployed force. In other words, so the argument goes, the B61 LEP is a nonproliferation measure intended to reduce the amount of HEU that would be lost if a B61-12 were ever stolen.

This justification is only partly relevant because roughly half of the weapons deployed in Europe already are B61-4 so returning them as B61-12 with the same nuclear explosive package and amount of HEU will not reduce that portion of the deployed force. The HEU-heavy B61-7s are not stored overseas but in the United States (and so are the B61-10s) and most of those are not even at the bomber bases but in central storage facilities.

| B61-7 and JDAM |

|

| The B61 (front, white) is similar in size to the JDAM (back). All high-yield B61-7s are stored in the United States. Image: USAF |

.

Moreover, the total number of B61-12s to be produced is far lower than the combined number of B61 versions in today’s stockpile – perhaps only around 400, down from an estimated 930 weapons.

Far less clear is how the agencies have determined that the risk of theft of a B61 has increased so much after September 2001 that too much HEU is deployed and existing safety and security features are inadequate to protect the weapons. Not least because a National Academy of Sciences task force recently concluded that “there is no comprehensive analytical basis for defining the attack strategies that a malicious, creative, and deliberate adversary might employ or the probabilities associated with them.” As a result, the task force concluded that it “could not identify how to assess the types of attacks that might occur and their associated probabilities.”

That doesn’t seem to have dampened NNSA’s pursuit of exotic safety and security features for all U.S. nuclear warheads in the name of an increased threat. Ironically, in doing so, NNSA is following White House guidance from 2003 that ordered “incorporation of enhanced surety features independent of any threat scenario” (emphasis added). Apparently, increased surety is not needed because of a specific increased threat but because of a policy.

But no one seems to be asking whether the B61 bombs in Europe are being exposed to unnecessary risks because the Air Force continues to scatter them in underground vaults underneath dozens of aircraft shelters at airbases in five European countries with different security standards; the deployment itself may add to the insecurity of the weapons.

The End of U.S. Non-Strategic Warheads

The B61-12 program marks the end of the 60-year old practice of the U.S. military to have designated non-strategic or tactical nuclear warheads in the stockpile. The only other remaining non-strategic warhead in the stockpile, the W80-0 for the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), is also being eliminated.

| A “Tactical” Nuclear Weapons Phase-Out |

|

| The B61 LEP eliminates the last designated non-strategic (tactical) nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile, a category of warheads that used to dominate the U.S. arsenal, making the disparity with Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons a non-issue. |

.

With the elimination of the last non-strategic bombs (B61-3, -4 and -10), the B61-4 will be converted to meet the mission requirement of the B61-7; essentially, the non-strategic B61-4 will become a strategic bomb. The B61-12 will be carried by both long-range bombers and short-range fighter-bombers; strategic or non-strategic will be determined by the delivery platform rather than the warhead designation.

Ironically, eliminating non-strategic nuclear warheads and instead using strategic warheads in support of NATO actually meets the language of the Alliance’s new Strategic Concept, which states that “The supreme guarantee of the security of the Allies is provided by the strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance” rather than non-strategic bombs (emphasis added).

Implications and Recommendations

The B61 LEP appears to be much more than a simple life-extension of an existing warhead but an upgrade that will also increase military capabilities to hold targets at risk with less collateral damage.

It is perhaps not surprising that the nuclear laboratories and nuclear warfighters will try to use warhead life-extension programs to increase military capabilities of nuclear weapons. But it is disappointing that the White House and Congress so far have not objected.

The NPR clearly states that, “Life Extension Programs…will not…provide for new military capabilities.” I’m sure we will hear officials argue that the B61 LEP doesn’t provide new military capabilities because it doesn’t increase the warhead yield beyond the maximum of the existing four types.

But this narrow interpretation misses the point. Mixing precision with lower-yield options that reduce collateral damage in nuclear strikes were precisely the scenarios that triggered opposition to PLYWD and mini-nukes proposal in the 1990s. Warplanners and adversaries could see such nuclear weapons as more useable allowing some targets that previously would not have been attacked because of too much collateral damage to be attacked anyway. This could lead to a broadening of the nuclear bomber mission, open new facilities to nuclear targeting, reinvigorate a planning culture that sees nuclear weapons as useable, and potentially lower the nuclear threshold in a conflict.

Such concerns ought to be shared by the Obama administration, which has pledged to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and work to prevent that nuclear weapons are ever used. The pledge to reduce the role of nuclear weapons has received widespread international support but will fall flat if one of the administration’s first acts is to increase the capability of nuclear weapons.

How Russia and NATO allies will react remain to be seen, but increasing NATO’s nuclear capabilities at a time when the United States is trying to engage Russia in talks about limiting non-strategic nuclear weapon seems counterproductive.

These talks could become more complicated because the B61 LEP eliminates non-strategic nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile and instead leaves the B61-12 to cover both strategic and non-strategic scenarios. That will further blur the line between strategic and non-strategic weapons and make it a challenge to meet the U.S. Senate’s requirement “to initiate…negotiations with the Russian Federation on an agreement to address the disparity between the non-strategic (tactical) nuclear weapons stockpiles of the Russian federation and of the United States and to secure and reduce tactical nuclear weapons in a verifiable manner.” After the B61 LEP the United States will not have any non-strategic nuclear warheads to negotiate with, essentially making the “disparity” a non-issue.

NATO declared in its Strategic Concept from November 2010 that the alliance “will seek to create the conditions for further reductions in the future” of the number and reliance on nuclear weapons. Increasing the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture appears to contradict that pledge and could lead to increased opposition to continued deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

At the very least, the administration and Congress need to define and publicly clarify what constitutes “new capabilities.” More than $213 billion are planned for nuclear modernizations in the next decade; it’s hard to believe that there will be no “new capabilities” slipping through in that work. In fact, current plans for warhead life-extension programs indicate that the nuclear establishment intends to take full advantage of the uncertainly by increasing the targeting capabilities of the nuclear weapons: it is already happening with the W76 LEP, which is being deployed on submarines with increased targeting capability; it is scheduled to happen with the B61 LEP; and it appears to be planned for the W78 LEP as well.

The logic seems to be: “We’re reducing the number of weapons so of course the remaining ones have to be able to cover more scenarios.” In other words, the price for arms control is increased military capabilities.

The administration should also direct that the portion of the B61-12s that are earmarked for deployment in Europe be deployed without the new guidance tail kit but retain the accuracy of the exiting weapons currently deployed in Europe. Otherwise the B61-12 should not be deployed in Europe.

Finally, the administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review should narrow the role of nuclear weapons to prevent that numerical reductions become a justification for increasing the capabilities of the remaining weapons. The new guidance must depart from the “warfighting” mentality that still colors nuclear war planning and is so vividly illustrated by the precision low-yield options offered by the B61-12.

NOTE: This blog is also available in PDF format as an Issue Brief.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The B61 Life-Extension Program: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal. The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy. As a result, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with an enhanced capability targets.

Upsetting the Reset – The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense

The Obama administration is working with NATO to develop a missile defense shield to protect U.S. and European interests from ballistic missile attacks by Iran. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev has expressed strong concerns over this shield and has warned of a return to Cold War tensions, as well as possible withdrawal from international disarmament agreements like the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

On June 9, the NATO-Russia Council plans to meet with defense ministers to establish cooperation guidelines for the new European antiballistic missile system. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is releasing a new report that addresses concerns made by officials of the Russia Federation and provides recommendations for moving forward with a missile defense system..

Dr. Yousaf Butt, Scientific Consultant to FAS, and Dr. Theodore Postol, Professor of Science, Technology and National Security Policy in the Program in Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have published a technical assessment (PDF) of the Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA) missile defense system proposed by NATO and the United States and analyzed whether the Russian Federation has a legitimate concern over the proposed NATO-U.S. missile defense shield.

In practice the PAA will provide little, if any, protection leaving nuclear deterrence fundamentally intact. While the PAA would not significantly affect deterrence, it may be seen by cautious Russian planners to impose some attrition on Russian warheads. While midcourse missile defense would not alter the fundamental deterrence equation with respect to Iran or Russia, it may, in the Russian view, constitute an infringement upon the parity set down in New START.

Defense Science Board: Air Force Nuclear Management Needs Improvements

|

| The Defense Science Board recommends reducing the number of inspections of nuclear bomber and missile units. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s “independent” Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety has completed a review of the Air Force’s efforts to improve the safety and proficiency of its nuclear bomber and missile units. The report comes three and a half years after the notorious incident at Minot Air Base where six nuclear cruise missiles were mistakenly loaded onto a B-52H bomber and flown across the United States.

The report, Independent Assessment of the Air Force Nuclear Enterprise, finds progress has been made but also identifies some serious issues that still need to be fixed. Some of them are surprising.

Inspections Gone Amok

The most important finding is probably that the nuclear inspection system following Minot has gone amok and in some cases become counterproductive. The number and scope of inspections were increased in response to the incident, but now they have become so frequent and widely applied that nuclear units have neither the time nor resources to correct the deficiencies that are actually identified. Instead the inspection system needs to be limited and focused on where the problems are.

It is natural that leadership will want to demonstrate rigorous efforts to correct deficiencies after a serious incident like Minot by beefing up inspections and exercises as proof that they’re taking things seriously. But this has resulted in a continuous and across-the-board level of inspections and exercise activity that part of the Air Force leadership sees as needed “until a zero-defect culture can be reestablished.”

In reality there has probably never been a zero-defect situation and, when overdone, the high level of inspections and exercises lead to an unrealistic zero-risk mindset. In other words, the leadership needs to cultivate a realistic inspection culture that is focused on detecting and correcting defects rather than expecting to eliminate them.

Over-focus on zero-defect can create distrust in the lower ranks that the leadership doesn’t trust them to perform professionally. This is, the DSB report bluntly concludes, “creating a leadership mindset where satisfying a Nuclear Surety Inspection team, for example, can supplant, or at least compete with, focus on readiness to perform the assigned nuclear mission.”

And nuclear inspection excess combined with multiple over-laying agencies and organizations can create bizarre situations such as in the case of inspections of Munitions Support Squadrons (MUNSSs) in Europe where it is not uncommon to have 80-90 inspectors examining a unit with a total manning of less than 150 personnel.

The report recommends returning gradually to the normal 18-month inspection scheduled used before the Minot incident, and states that additional inspections should occur “only to address unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends.” In other words: no additional inspections unless a problem has already been detected.

For the Air Force’s nuclear deployment in Europe, the report recommends that follow‐up re‐inspections and special inspections of air bases and other nuclear units be discontinued unless unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends have been identified. For all other discrepancies the wing commander or the MUNSS commander should be accountable for closing out the discrepancies in communication with the appropriate inspection agency. Serious security issues were found at European bases in 2008 and evidently had still not been fixed in 2010.

The DSB report does not, however, describe in detail how or to what extent the nuclear proficiency level has evolved in the nuclear units as a result of the increased inspections and oversight established after 2007. It concludes that a culture of special attention to nuclear issues has been reestablished at the operational level, but not fully at the supporting system of the Air Force nuclear enterprise. It would have been interesting to see how that has affected the actual nuclear inspection grades of the individual units.

Resources Still Lacking

While the Air Force leadership has spoken at length about the importance of improving the nuclear proficiency and safety, the report concludes that the leadership has not yet put the money where its mouth is in terms of prioritizing budgets, upgrades of support equipment, directives and technical orders, and tailoring personnel policies to specific nuclear missions. There is still a degree of business-as-usual in planning and acquisition.

For example, the report identifies that 40-plus year munitions hoists are not being replaced, that engineering requests for reentry vehicles has skyrocketed from 100 in 2007 to 1,100 in 2010, and that repairs of nuclear Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMTs) at bases in Europe has been delayed by missing spare parts. There are currently 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs scattered across six bases in five European countries. The 14 WMTs are scheduled for replacement with the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS) in 2014.

Reliability But No Trust

The report concludes that the Air Force’s Personal Reliability Program (PRP), intended to ensure that only qualified people are allowed access to nuclear weapons, has not improved and in some cases increasingly suffers from defects. One problem identified is a continuing escalation of the pursuit of absolute assurance of personal reliability, which the report concludes created “important dysfunctional aspects in the program” where threat of suspension and decertification has produced an environment of distrust. People that have been selected are not sufficiently trustworthy to live an acceptable daily life and must continuously reestablish their credibility. According to the report:

“Even the possibility of Potentially Disqualifying Information (PDI) leads to temporary decertification until it is established that there has been no compromise of reliability. Based on this fundamentally flawed assumption, the PRP repeatedly reexamines the history of each individual.”

“As one example of the consequences of this attitude, personnel are automatically suspended from PRP duties when referred by Air Force medical authorities to off‐base medical treatment regardless of the nature of the referral. The individual must then report to base medical authorities to be reinstated.”

Personnel issues also continue to plague the nuclear wings and MUNSS units in Europe, where the DSB report describes personnel management has created “a flow of people who have no nuclear experience into the key DCA wing in Europe” [i.e. 31st FW at Aviano] and the MUNSS sites at national bases.

As a result, the DSB report recommends that Air Force PRP-based restrictions and monitoring standards be reduced to match those required by DOD.

Command Structure Readjustment

The DBS report also recommends that the nuclear command structure that was set up after the Minot incident be readjusted to that all base-level operations and logistics functions be assigned to the strategic missile and bomb wings reporting through the numbered air forces to Air Force Global Strike Command.

One effect of this command readjustment is the transfer of all munitions squadrons responsible for nuclear mission support from Air Force Material Command to the Air Force Global Strike Command within the next 12 months, recently described by the Air Force.

Download Defense Science Board report

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

10 NATO Countries Want More Transparency for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| Ten NATO countries recommend increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons, including numbers and locations at military facilities such as Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. Neither NATO nor Russia currently disclose such information. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Four NATO countries supported by six others have proposed a series of steps that NATO and Russia should take to increase transparency of U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The steps are included in a so-called “non-paper” that Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland jointly submitted at the NATO Foreign Affairs Minister meeting in Berlin on 14 April.

Six other NATO allies – Belgium, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, Luxemburg and Slovenia – also supported the paper.

The four-plus-six group recommend that NATO and Russia:

- Use the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) as the primary framework for transparency and confidence-building efforts concerning tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

- Exchange information about U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons, including numbers, locations, operational status and command arrangements, as well as level of warhead storage security.

- Agree on a standard reporting formula for tactical nuclear weapons inventories.

- Consider voluntary notifications of movement of tactical nuclear weapons.

- Exchange visits by military officials [presumably to storage locations].

- Exchange conditions and requirements for gradual reductions of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, including clarifying the number of weapons that have been eliminated and/or stored as a result of the 1991-1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs).

- Hold a NRC seminar on tactical nuclear weapons in the first quarter of 2012 in Poland.

According to estimates developed by Robert Norris and myself, the United States currently has an inventory of approximately 760 non-strategic nuclear weapons, of which 150-200 bombs are deployed in five European countries. Russia (updated estimate forthcoming soon, previous estimate here) has larger inventory of 3,700-5,400 nonstrategic weapons in central storage, of which an estimated 2,000 are deliverable by nuclear-capable forces.

The proposal comes as the first phase of NATO’s new Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR) has begun preparation of four so-called scoping papers on 1) the threat facing NATO, 2) the alliance’s strategic mission, 3) the appropriate mix of military forces, and 4) the alliance’s arms control and disarmament policy. The four-plus-six initiative seeks to provide input to the DDPR as well as future work of NATO’s new Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Control and Disarmament Committee. The results of the DDPR are scheduled for approval by the alliance at the summit in March 2012.

Five of the 10 countries supporting the new initiative also were behind an initiative in February 2010 that urged the alliance to include its nuclear policy on the agenda for the NATO meeting in Tallinn in April 2010. The non-paper builds on a previous Polish-Norwegian initiative from April 2010 that is not described.

The Strategic Concept adopted by NATO in November 2010 removed much of the language that previously had identified U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe as the trans-Atlantic “glue” in the alliance. Unfortunately, after unilaterally reducing the U.S. weapons in Europe by more than half between 2000 and 2010 and insisting that the deployment was not linked to Russia, NATO reinstated Russia as an official link by concluding in the Strategic Concept that “any” reductions in the U.S. deployment must take into account the disparity with Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The four-plus-six paper does not explicitly call for new cuts and explicitly rejects unilateral reductions. However, it states that transparency and confidence building are “crucial to paving the way for concrete reductions.” To that end the paper is in tune with statements recently made by Gary Samore, Special Assistant to the President and White House Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction, Proliferation, and Terrorism, and by Rose Gottemoeller, Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance.

I’m an avid supporter of increasing transparency, but given the success of the unilateral Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs) of 1991-1992 in jumpstarting reductions in non-strategic nuclear weapons without verification, I’m a little concerned about how ready some are to reject unilateral cuts. After all, the United States and NATO have just approved one: retirement of the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack missile (TLAM/N). Rather, transparency, unilateral cuts, and negotiated reductions should all be embraced as tools to move the process forward of reducing the number and role of nuclear weapons.

See: NATO Non-Paper on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Report: What NATO Countries Think About Tactical Nukes

|

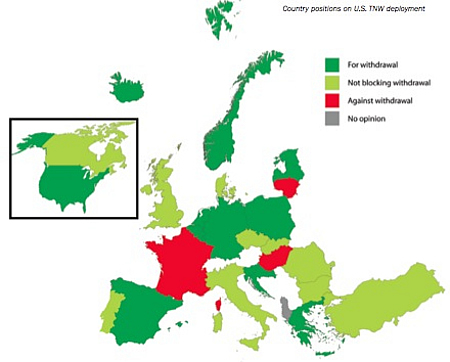

| Most NATO countries support withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, only three oppose, according to interviews with NATO officials. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two researchers from the Dutch peace group IKV Pax Christi have published a unique study that for the first time provides the public with an overview of what individual NATO governments think about non-strategic nuclear weapons and the U.S. deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe.

Their findings are as surprising as they are new: 14, or half of all NATO member states, actively support the end of the deployment in Europe; 10 more say they will not block a consensus decision to that end; and only three members say they oppose ending the deployment.

Anyone familiar with the debate will know that while there are many claims about what NATO governments think about the need for U.S. weapons in Europe, the documentation has been scarce – to say the least. Warnings against changing status quo are frequent and just yesterday a senior NATO official told me that, “no one in NATO supports withdrawal.”

The report, in contrast, finds – based on “interviews with every national delegation to NATO as well as NATO Headquarters Staff” – that there is overwhelming support in NATO for withdrawal.

The most surprising finding is probably that most of the Baltic States support withdrawal, only Lithuania does not.

Even Turkey, a country often said to be insisting on continued deployment, says it would not oppose a withdrawal.

The only real issue seems to be how a withdrawal would take place. The three opposing countries – one of which is France – block a potential consensus decision, a condition for 10 countries to support withdrawal.

The Obama administration needs to take a much more proactive role in leading NATO toward a decision to end the U.S. deployment in Europe. This can be done without ending extended deterrence and without weakening the U.S. commitment to NATO’s defense.

Background: IKV Pax Christi study | Nuclear Notebook: U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe, 2011

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The Nuclear Weapons Modernization Budget

The FY2012 budget request includes considerable nuclear weapon modernization

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Obama administration has published its budget request for Fiscal Year 2012, which includes its plans for maintaining and modernizing its nuclear weapons arsenal.

Due to the extensive debate about the New START treaty last year a great deal of the nuclear plans were already known. And the budget request demonstrates that the administration follows through on its promise to modernize the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal and production facilities.

How this modernization effort will color the administration’s public nuclear legacy remains to be seen.

Warhead Maintenance and Modernization

The budget includes significant investments in maintaining and modernizing the nuclear weapons in the stockpile through the life-extension programs (LEPs). Including the costs from FY2011, the administration plans to spend $6.3 billion through FY2016 on the warheads in the stockpile. Additional LEPs are planned after 2016 (see Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan).

Determining what portion of these costs will be spent on LEPs is difficult because LEP costs for each warhead in the budget are included in the stockpile costs until the LEP gets full go-ahead. That means that stockpile costs are significantly ballooned for some years. When compensating for this accounting rule, the total cost for LEP work in FY2011 through FY2016 is roughly $4.9 billion.

There are three primary LEPs in the budget involving the B61, W76, and W78 warheads. The W88 is also undergoing a small LEP to replace the Arming, Fuzing and Firing (AF&F) unit. Details of the LEPs are:

W76 LEP: Production of W76-1 at the Pantex Plant in Texas is well underway after start-up problems. The first warhead was produced in 2008 and warheads are now being delivered to the navy and deployed on Trident II D5 ballistic missiles. Full-scale production will be achieved in 2013 and continue through 2018. The FY2012 budget request shows $1.5 billion spent on the LEP through FY2016. The LEP extends the life of the warhead for another 30 years and adds new safety features and improves the military capability of the W76.

B61 LEP: Production of a new B61 version called the B61-12 will begin in FY2017 and increase during FY2018 as the W76 production fades out and continue through FY2022. The B61-12 will combine three older B61 versions (B61-3/4/7) into one. The consolidation was previously also scheduled to include the B61-10, a converted W85 Pershing II warhead, but the B61-10 has recently been retired. The B61-12 will reuse the B61 plutonium pit for the primary and reuse or remanufacture the B61-4 secondary. The modification will extend the life of the B61 for another 30 years.

The budget states that the new version will have better reliability, enhanced margin against failure, increasing safety, and improving security and use control. The budget also states that, “insensitive high explosives could replace conventional high explosives,” a curious statement given that the government has previously stated that the remaining B61 versions already have insensitive high explosives.

|

| The B61-12 will be based on components from three different B61 types: B61-3, B61-4 and B61-7. The secondary will be from the B61-4 or remanufactured. Although the NNSA budget mentions replacing conventional high explosives with insensitive high explosives, all stockpiled B61s already have insensitive high explosives. |

.

W78 LEP: This warhead program is evolving into a whole new experiment with the plan to develop a “common high-surety warhead” for deployment of the Minuteman III ICBMs and Trident II D5 SLBMs. Studies are still defining the full scope of this warhead but it includes new safety and use-control features. A new AF&F will “maximize” use of the fuze program for the navy’s Mk5/W88 program. Approximately $1 billion is budgeted for this LEP through FY2016, but the program extends well beyond 2025 with significant additional costs.

W87: The budget also shows that a new AF&F for the Mk21/W87, the second warhead on the Minuteman III, is being considered to match the W78 LEP. Like the common warhead, this will also maximize use of Mk5 fuze program elements.

W88: Although not yet scheduled to under a full LEP, the Mk5/W88 is undergoing a crash program to replace its AF&F unit. Fuzes are very expensive, and the budget includes roughly $432 million through FY2016. This new fuze technology will probably form the basis for the new fuze planned for the W78 and W87.

The navy budget also indicates development of an advanced radiation-hardened GPS receiver for ballistic missile reentry bodies, a technology that would be required for maneuverable warheads. A flight test of the GPS unit is scheduled for FY2011.

The dismantling of retired warheads does not appear to be a priority for the Obama administration. There are several thousand retired warheads – probably around 3,500 – in storage awaiting dismantlement. Most were retired during the reduction of the stockpile by nearly half in 2004-2007, but the annual dismantlement budget will be less than in 2010 and comparable to that of the Bush administration. The $56.8 million scheduled for FY2012 is a 40% reduction compared with FY2010. At the planned rate, all warheads retired prior to FY2010 will be dismantled by 2022.

Nuclear Delivery Vehicles

In addition to modernizing the warheads and the production complex, the Obama administration has also pledged to spend “well over 100 billion dollars” on modernizing some of the missiles, submarines and bombers designed to deliver the warheads.

Ballistic missile submarine: The next class of ballistic missile submarines – commonly called SSBN(X) – is called Sea Based Strategic Deterrent (SBSD) Advanced Submarine System Development (ASSD) in the budget. The budget includes $781.6 million in FY2012 and shows $5.1 billion through FY2010-FY2016.

|

| The next SSBN class will have 16 missile tubes, unlike the Ohio-class seen here, which has 24 tubes. The first unit is scheduled to enter service in 2029, carry a life-extended version of the Trident II D5 SLBM, and be in service through the 2080s. |

.

The SSBN development strategy is to maximize re-use of existing Ohio-class SSBN systems and new designs from Virginia-class SSNs.

The budget does not specify the number of missile tubes per submarine, but the Defense Acquisition Board decided in December 2010 that the new design should have 16 tubes. The navy purchased another 24 D5LE missiles in FY12.

The previous ambition to deploy conventional warheads on SLBMs has suffered many setbacks but lives on in the new budget, although only as a study to examine the ambiguity issues involved in launching conventional weapons from a nuclear strike platform and “better understand the capabilities that could be delivered from naval platforms.”

Land-based missiles: There is no money listed in the budget for the initial study of alternatives promised by the Nuclear Posture Review, but a small amount – $2.6 million – are included to study current or “future ICBM weapon systems.” But with the intension to extend the service life of the Minuteman III ICBM through at least 2030 – possibly longer – it is too early for a new missile to appear in the budget. The Minuteman III is in the final phase of a decade-long upgrade that has replaced all major components; it is essentially a new missile.

Efforts to equip ICBMs with conventional warheads continue, and a conventional strike mission integration demonstration study is scheduled for completion at the end of FY2011.

Heavy bombers: Both B-2 and B-52 are being upgraded for the new Advanced Extremely High Frequency (AHEF) satellite constellation, and to equip the bombers with additional nuclear hardening.

The B-2 will be equipped to carry the new B61-12 gravity bomb. The B-52 is undergoing a Reconstitution Study that will provide for further nuclear weapons in both bay and under wings. One of these is the Long Range Stand-Off (LRSO) cruise missile intended to replace the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) in 2030. The warhead might be the W80-3, a modified LEP version of the current W80-1. Nearly $10 million are scheduled to study the new missile in FY2012, with a total of $884,297 million through FY12-16.

The budget does not present a schedule for the next generation bomber, but it is in design development with $197,023 earmarked for FY2012 and $3.94 billion through FY2016. [Update: According to The Hill, Pentagon comptroller Robert Hale stated that the plan is to build 80-100 new bombers to replace the B-2 and B-52H. Only a portion of these would, presumably, become nuclear-capable.]

Fighter-bombers: The budget gives new details about the scope and nuclear capability of the Joint Strike Fighter. Follow-on development will be initiated of the F-35A CTOL Variant Air Vehicle for dual-capability (DCA). DCA integration is scheduled for FY2011-FY2017 with nuclear capability added in the first post-SDD (System Development and Demonstration) block upgrade (Block IV). F-35A will have capability to carry two B61s internally. There are $10 million budgeted for FY2012 with $262.7 million through FY2016 to support Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP) requirements from FY2017.

|

| The F-35A CTOL (conventional take off and landing) will be capable of carrying two B61-12 nuclear bombs, one in each bay. |

.

The F-35A Block IV will replace the F-15E and F-16 in the nuclear mission and also be offered to NATO allies that are tasked to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons.

Nuclear Factories

The budget provides new cost estimates for the two new nuclear weapons production factories that are under construction; the CMRR (Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement) facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the UPF (Uranium Production Facility) at the Y-12 complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Both factories are already over budget.

Based on 45% design completion, the CMRR is now estimated to cost $3.7-$5.8 billion to complete. The UPF is estimated at $4.2-$6.5 billion. A total of $9.9-$12.3 billion. But even this is probably too low and NNSA promises that a new estimate will come in FY2013 after the factories reach 90% design completion. Full operation of the two factories is planned for FY2023 and FY2024, respectively. GAO recently concluded that NNSA has very poor basis for making realistic cost estimates.

Implications and Outlook

With massive investments in widespread modernization of nuclear forces and industry, the FY2012 budget shows that the Obama administration is following through on its promise to make significant investments in modernizing the U.S. nuclear deterrent.

The “generational” modernizations proposed in the budget represent a commitment to extending the nuclear era as long into the future as it has lasted so far. A challenge will be whether nuclear modernization will overshadow nuclear disarmament in the administration’s public nuclear image.