B61-12 Nuclear Bomb Triggers Debate in the Netherlands

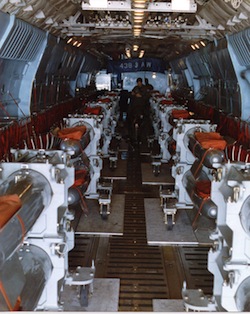

In a few years, US Air Force C-17 aircraft will begin airlifting new B61-12 nuclear bombs into six air bases in five NATO countries, including Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands (seen above).

By Hans M. Kristensen

The issue of the improved military capabilities of the new B61-12 nuclear bomb entered the Dutch debate today with a news story on KRO Brandpunt (video here) describing NATO’s approval in 2010 of the military characteristics of the weapon.

Dutch approval to introduce the enhanced bomb later this decade is controversial because the Dutch parliament wants the government to work for a withdrawal of nuclear weapons from the Netherlands and Europe. The Dutch government apparently supports a withdrawal.

Bram Stemerdink, who was Dutch defense minister in 1977 and deputy defense minister in 1973-1976 and 1981-1982, said that the Dutch government would have been consulted about the B61-12 capabilities. “Because we have those bombs at the moment. Was the Netherlands therefore consulted, yes,” Stemerdink reportedly said.

Former Dutch defense minister Bram Stemerdink said the Netherlands would have been consulted about the military capabilities of the enhanced B61-12 bomb.

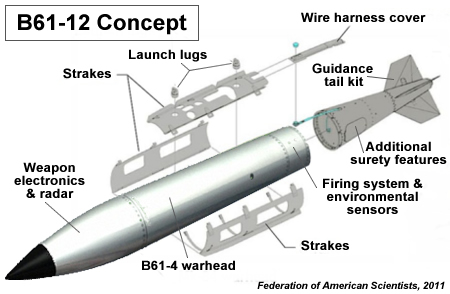

NATO approved the military characteristics of the B61-12 in April 2010, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, “including the yield, that it be capable of freefall (rather than parachute-retarded) delivery, its accuracy requirements when used on modern aircraft and that it employ a guided tailkit section, and that it have both midair and ground detonation options.”

Dutch approval is also controversial because the improved military capabilities of the B61-12 compared with the weapons currently deployed in Europe (addition of a guidance tail kit to increase accuracy and provide a standoff capability) contradict the U.S. pledge from 2010 that nuclear weapon life-extension programs “will not…provide for new military capabilities.” The U.S. currently does not have a guided standoff nuclear bomb in its stockpile. The improved military capabilities also contradict NATO’s promise from 2012 to seek to “create the conditions and considering options for further reductions of non-strategic nuclear weapons assigned to NATO…”

Last month Dutch TV disclosed a dispute between the U.S. and Dutch governments over how to discuss potential financial compensation in case of an accident involving U.S. nuclear weapons in the Netherlands.

The B61-12 is currently being designed for production with a price tag of more than $10 billion for approximately 400 bombs – possibly the most expensive U.S. nuclear bomb ever.

Nuclear weapons are unlikely to remain in Europe for long, so instead of wasting more than $10 billion on the controversial enhanced B61-12 for a mission that has expired, the United States should instead do a more basic and cheaper life extension of an existing version. Instead of wasting money on modernizing a nuclear weapon for Europe, the United States should focus its efforts on changing the views of eastern European NATO countries by providing extended deterrence in a form that actually contributes to their security.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Dispute Over US Nuke in the Netherlands: Who Pays For An Accident?

Who pays for a crash of a nuclear weapons airlift from Volkel Air Base?

By Hans M. Kristensen

Only a few years before U.S. nuclear bombs deployed at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands are scheduled to be airlifted back to the United States and replaced with an improved bomb with greater accuracy, the U.S. and Dutch governments are in a dispute over how to deal with the environmental consequences of a potential accident.

The Dutch government wants environmental remediation to be discussed in the Netherlands United States Operational Group (NUSOG), a special bilateral group established in 2003 to discuss matters relating to the U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in the Netherlands.

But the United States has refused, arguing that NUSOG is the wrong forum to discuss the issue and that environmental remediation is covered by the standard Status of Forces Agreement from 1951.

The disagreement at one point got so heated that a Dutch officials threatened that his government might have to consider reviewing US Air Force nuclear overflight rights of the Netherlands if the United States continue to block the issue from being discussed within the NUSOG.

The dispute was uncovered by the Brandpunt Reporter of the TV station KRO (see video and also this report), who discovered three secret documents previously released by WikiLeaks (document 1, document 2, and document 3).

The documents not only describe the Dutch government’s attempts to discuss – and U.S. efforts to block – the issue within NUSOG, but also confirm what is officially secret but everyone knows: that the United States stores nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base.

Michael Gallagher, the U.S. Charge d’Affaires at the U.S. Embassy in Hague, informed the U.S. State Department that environmental remediation is “primarily an issue of financial liability” and discussing it “potentially a slippery slope.” During on e NUSOG meeting, Dutch civilian and military participants were visibly agitated about the U.S. refusal to discuss the issue, and Gallagher warned that “a policy of absolute non-engagement is untenable, and will negatively impact our bilateral relationship with a strong ally.”

Gallagher predicted that the Dutch would continue to raise the issue, and said the Netherlands was ahead of the other European countries that host U.S. nuclear weapons on their territories in having signed and implemented the NUSOG. Unlike Germany, Belgium, Italy and Turkey, the Netherlands was the only country that had raised the issue of remediation in a forum such as NUSOG, but Gallagher warned that the other countries would raise the issue of remediation in the future as similar nuclear weapons operational groups are established.

Charge d’Affaires Michael Gallagher shakes hands with Dutch foreign minister Frans Timmermans, who wants U.S. nuclear weapons removed from the Netherlands.

The United States has deployed nuclear weapons in the Netherlands since April 1960 and currently deploys an estimated 10-20 nuclear B61 bombs in underground vaults inside 11 aircraft shelters at Volkel Air Base. The weapons are under the custody of the US Air Force’s 703rd Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a 140-personnel unit that secures and maintains the weapons at Volkel.

In a war, the U.S. nuclear bombs at Volkel would be handed over to the Dutch Air Force for delivery by Dutch F-16 fighter-bombers of the 1st Fighter Wing. The Netherlands is one of five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) that have this nuclear strike mission, which clearly violates the spirit of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

A B61 nuclear bomb is loaded onto a C-17 cargo plane. Improved B61-12 bombs are scheduled to be deployed to Volkel at the end of the decade.

From 2019 (although delays are expected), the U.S. Air Force would begin to deploy the new B61-12 nuclear bomb to Volkel and the five other bases in Europe that currently store the old B61 types. The B61-12, which is scheduled for production under a $10 billion-plus program, will have improved military capabilities compared with the weapons currently stored at the bases.

The U.S.-Dutch dispute over remediation is but the latest political irritant in the deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe, a deployment nearly 200 B61 bombs at five bases in six countries that costs about $100 million a year but with few benefits. President Obama has promised “bold reductions” in U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Volkel Air Base would be a good place to start.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nukes in Europe: Secrecy Under Siege

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Cold War practice of NATO and the United States refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere is under attack in Europe. This week, two former Dutch prime ministers publicly confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, one of six bases in NATO that still host US nuclear weapons.

The Cold War practice of NATO and the United States refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere is under attack in Europe. This week, two former Dutch prime ministers publicly confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, one of six bases in NATO that still host US nuclear weapons.

The first confirmation came in the program How Time Flies on the Dutch National Geographic channel where former prime minister Ruud Lubbers confirmed that there are nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base. “I would never have thought those silly things would still be there in 2013,” Lubbers said, who was prime minister in 1982-1994. He even mentioned a specific number: 22 bombs.

The second confirmation Lubbers was joined yesterday by another former Dutch prime minister, Dries van Agt, who also confirmed that the weapons are there. “They are there and its crazy they still are,” said va Agt, who was prime minister in 1977-1982.

The second confirmation Lubbers was joined yesterday by another former Dutch prime minister, Dries van Agt, who also confirmed that the weapons are there. “They are there and its crazy they still are,” said va Agt, who was prime minister in 1977-1982.

As readers of this blog are aware (and anyone who have followed this issue over the years), it is not news that the US stores nuclear weapons at Volkel AB. But it is certainly news that two former Dutch prime ministers are now confirming it.

It is not a formal Dutch break with NATO nuclear secrecy norms but it is certainly a big crack in the dike that makes the Dutch government’s continued refusal to confirm or deny nuclear weapons at Volkel AB look rather, well, silly.

The instinct of the bureaucracy will be to ignore the statements to the extent possible and retreat into past policies of neither confirming nor denying the presence of nuclear weapons. But the new situation also presents an opportunity to break with the past and attempt to engage Russia about increasing the transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe.

Privileged Information

Information about US nuclear weapons at Volkel AB is privileged information that Lubbers and van Agt would have had access to on a highly confidential basis as prime ministers under the bilateral US-Dutch nuclear weapons storage agreement code named Toy Chest (no pun intended).

After leaving office, Lubbers and van Agt would have had to rely on other people with access to such information to be told. A nod would be sufficient to confirm the general presence of weapons, but the specific number would be harder to get. Why Lubbers says 22 is unclear; perhaps that’s the number he recalls from 1994.

Back then, the Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review decided to retain 480 nuclear bombs in Europe. How many of those were at Volkel AB is unknown, but when President Clinton six years later in December 2000 signed Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-74 that authorized continued deployment of 480 nuclear weapons in Europe, 20 of those were for Volkel AB.

Since then, the United States has unilaterally reduced the stockpile in Europe by nearly 60 percent from 480 to nearly 200 bombs today. Whether the number at Volkel AB has remained the same is unknown. The base has 11 underground storage vaults inside Protective Aircraft Shelters that can house a maximum of 44 bombs (see image). The 22 bombs that Lubbers mentions would imply each vault carries two bombs, but it is probably unlikely that there are more weapons in the Volkel vaults today than in 2000.

Silly Dutch Secrecy

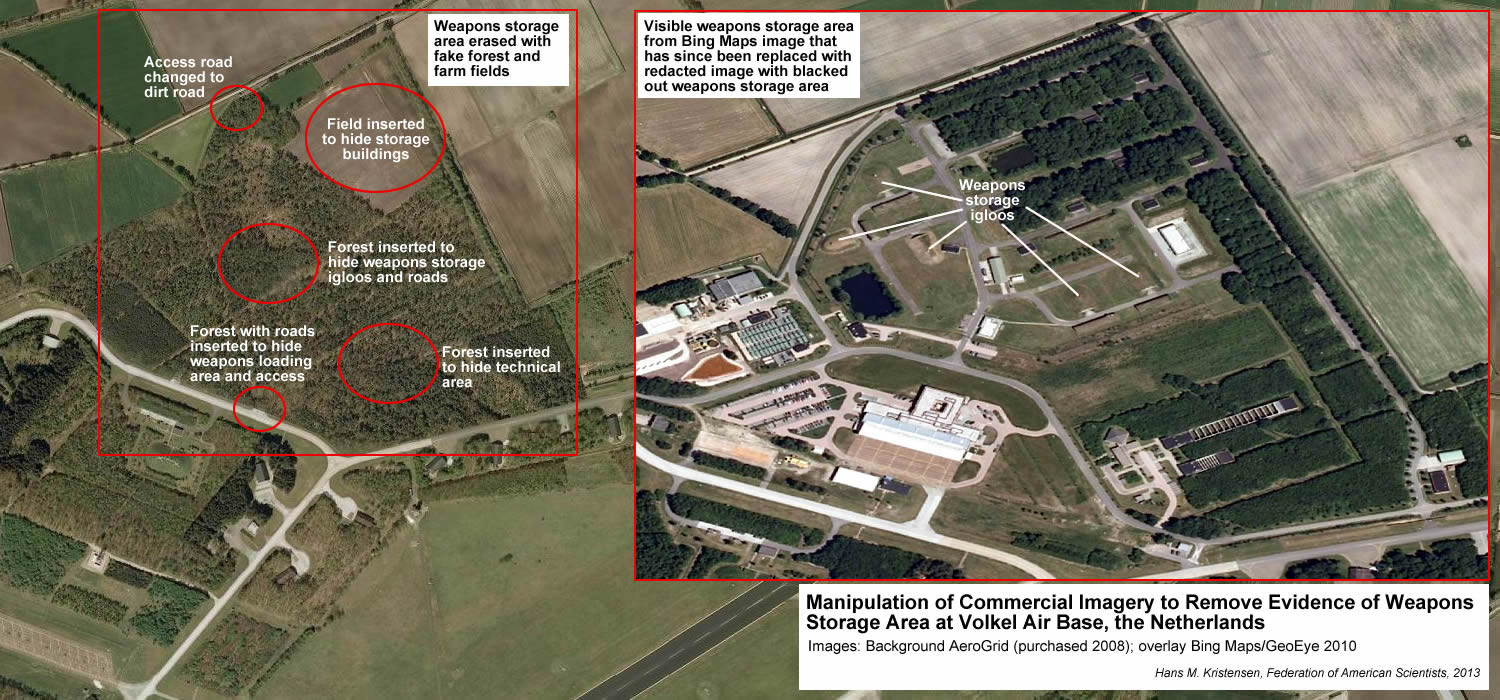

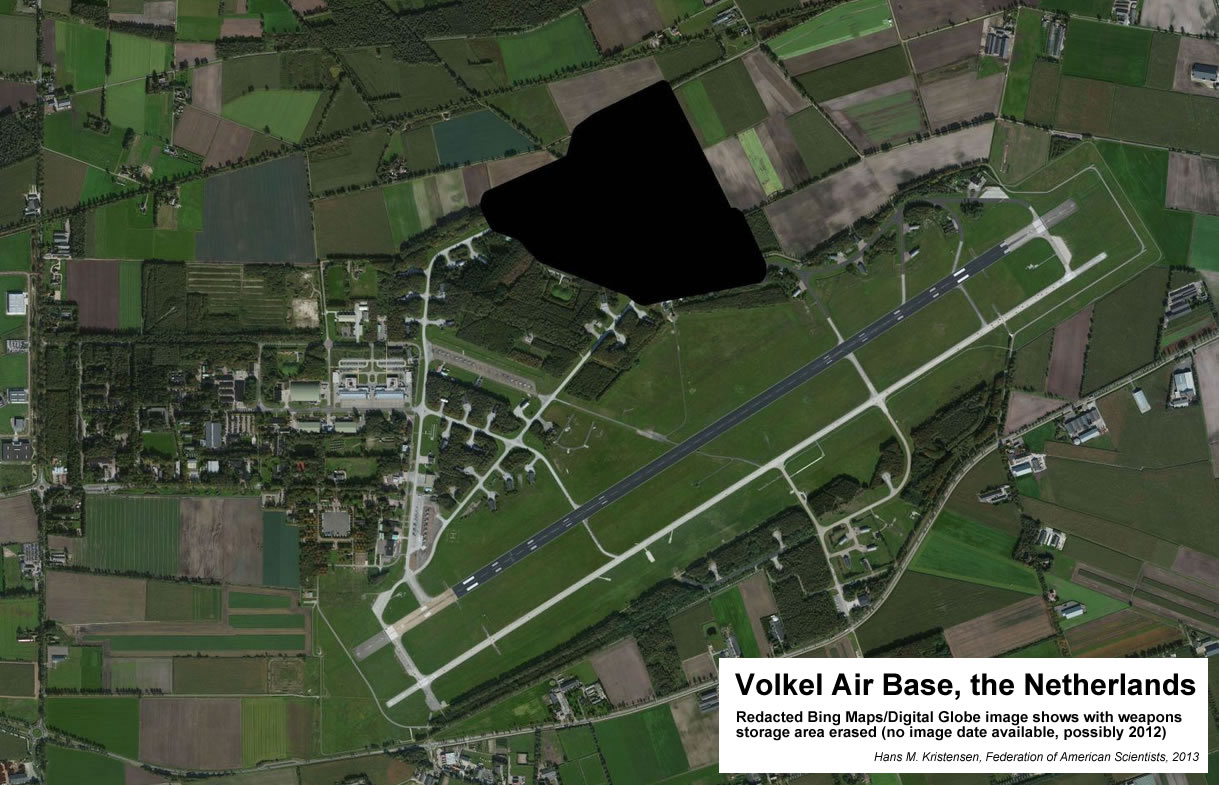

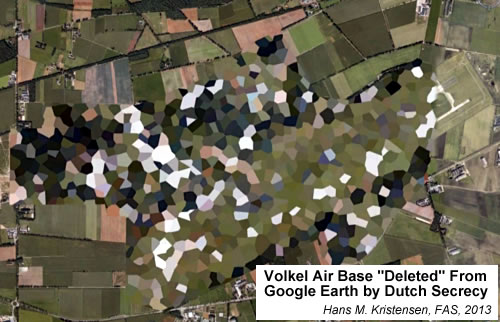

Getting basic information about the nuclear weapons at Volkel AB is not the only obstacle to nuclear transparency. Even aerial photos of the base are secret. For example, anyone who has tried to view Volkel AB on Google Earth will know that you can’t; the base has been completed pixel’ed out (see image below).

The reason is, the Dutch ministry of defense told me, that an old Dutch law requires that all military and royal (go figure!) facilities be obscured on aerial photos. And because the images covering the Netherlands on Google Earth are supplied by Aerodata International Surveys, a company partly based in Utrecht, the images are sanitized before handed over to Google Earth. It is a pity that a company such as Google lets itself be subjected to silly secrecy by accepting sanitized images on Google Earth.

The law is silly because all national-level adversaries (to Holland) have their own satellite imaging capabilities, so pixel’ing out Volkel AB won’t deny them any information. And anyone else can simply buy high-resolution satellite imagery on the Internet.

To test this point, I went to the web site of AeroGRID, a company partially owned by Aerodata (!). Armed only with a credit card, I was able to purchase a high-resolution image of Volkel Air Base that appeared to show the entire base (see image below).

Problem solved? Not quite. After a closer examination, I discovered that even this “clean” image had also been manipulated, even though AeroGRID never told me that the product I had paid for was actually a fake. Someone had very carefully erased a weapon storage area at the northern part of Volkel AB by overlaying it with trees and farm fields – even inserted forest roads that appear to meet up with dead-end access roads that would otherwise give away that the image had been altered.

Despite these efforts of silly secrecy, I was able to find the secret weapon storage area on another photo that was available on Bing Maps. That photo clearly showed the secret weapons storage area. By overlaying the area from the Bing Maps image onto the AeroGRID image, one can better see the extent of the image manipulation (see image below).

The secret weapons storage area is also visible on a Dutch military base map from 1999 that shows the layout of storage buildings and access roads. Comparison of the map with the Bing Maps image, however, also reveals that the weapons storage loading area has been upgraded significantly (see image below).

This un-redacted image is no longer available on Bing Map, however. Instead, on the new photo that is now available – yes, you guessed it – the weapons storage area has been deleted (see image below).

So why is the weapons storage area at Volkel AB secret? The facility was probably used to store the nuclear weapons until the underground vaults were added to the Protective Aircraft Shelters in 1991. But since then the weapons have been in the vaults. Perhaps they are sometimes serviced in the weapons storage area, or perhaps it’s simply a weapons storage area and therefore automatically considered secret. But now that we know that the weapons storage area is there and what it looks like, there is no need to manipulate the images anymore.

Implications and Conclusions

The confirmation by two former Dutch prime ministers that nuclear weapons are present at Volkel AB is an important contribution to increasing nuclear transparency in Europe. Although it doesn’t tell us something we don’t know, it challenges NATO’s long-standing, outdated, and counterproductive policy of keeping nuclear weapons locations secret. Germany has also confirmed that it hosts nuclear weapons.

Instead of trying to hush things up and continue the secrecy, the Dutch and German governments should together with NATO use the disclosures as an opportunity to reach out to Russia and propose a limited but reciprocal declaration of nuclear weapons storage at Volkel AB, Büchel AB in Germany, and one or two Russian bases. A declaration could be accompanied by verification of the absence of nuclear weapons from one or two bases in each country where nuclear weapons have been removed. Doing so could help jump-start the process of increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe, a goal NATO and the Dutch and German governments say they favor. Russia might be interested in exploring such an initiative.

Of course, such a transparency initiative will require the national leadership to twist the arms of the bureaucrats who will oppose any change. But incremental micromanagement of nuclear status quo in Europe will not move the ball forward; it requires political vision and leadership.

Continuing the nuclear secrecy no longer serves a beneficial purpose. The secrecy is not needed for safety or national security; those needs are taken care of by guards, guns, gates, and overall military and political postures. Instead, the secrecy fuels mistrust and rumors that lock NATO and Russia into old mindsets, postures, and relations. The secrecy is also used to chill a public debate that could otherwise result in a demand to withdraw the nuclear weapons from Europe.

One particularly controversial issue that faces the Dutch government and parliament in the next few years is that the B61 bombs at Volkel AB within the next decade are scheduled to be replaced with an improved nuclear bomb that is equipped with a new guidance tail kit that increases the weapon’s accuracy and gives it a standoff capability.

The combination of the new guided standoff B61-12 bomb and the stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter – that the Dutch air force plans to get to replace the F-16 that currently has the nuclear strike mission – will significantly increase the nuclear capability at Volkel AB.

Why does the Dutch government believe it is necessary to begin deploying new guided standoff nuclear weapons at Volkel AB? How will that support the efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons in Europe? How will that help persuade Russia to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons?

It would be smart for the Dutch parliament to try to get answers to these questions from the government before the new nuclear bombs and stealth bombers start arriving at Volkel AB.

Background: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (FAS 2012) | US Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 2011 (BAS 2011) | US Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC 2005)

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Reflecting on NATO Security in the Context of a Rising China

The future promises to be far more challenging than the past for international security analysts. The security challenges that we will face will be increasingly complex, transnational, and interrelated. This will make their mitigation all the more difficult. But, the reality of this changing security landscape should not cause us to give pause and adopt a Pangloss-like outlook toward our present condition. Insecurity is not a given – security can always be made by those with the will and intellect to do so. In any given context, making security simply requires accurately identifying and prioritizing threats to international security and then developing the requisite mitigations. In this respect, the profession remains largely unchanged from its Cold War origins.

What has changed is the theoretical disposition of international security analysts. Our current generation is far more open to the theorization of security as an essentially contested concept. This has transformed the nature of the international security discourse. It now openly embraces the notion that security is tied to the social construction of security threats. It is therefore valid to intervene in the debate over how China’s rise affects international security from a social constructivist perspective. Doing so requires recognizing that security is subjective and only meaningful in the presence of a referent object. As a consequence, we must start our analysis with the question: “Whose security are we talking about?”

For the purpose of this article, the discussion will be restricted to NATO member states.

From this perspective, China’s rise is but one of many important variables in the post-Cold War international security discourse. In fact, China is not alone in terms of rising power and prestige. Other important countries include the other BRICSI countries – Brazil, Russia, India, South Africa, and Indonesia. Their collective rise is shifting the global balance of power away from the NATO region and forcing major structural changes to global and regional security architectures.

To avert a systemic breakdown, the resident and emerging major powers will need to reach a strategic compromise. This might even require the construction of a new order that better accommodates the rising powers’ interests without sacrificing too much of the incumbents’. But, reaching such a compromise will not be easy.

If the two sides find themselves unable to forge an amicable solution, one or more of the emerging powers could make a revisionist move. In the decades ahead, international security analysts must therefore remain attentive to any signals that the rising power(s) are no longer willing or able to accept the notion that “international peace is more important than any other national objective.” In the end, it is the possible rejection of the status quo by one or more of these emerging powers that most threatens international peace and stability.

But there is far more to the story of international security in the 21st Century than just the rise of these emerging powers. The world is also witnessing other major changes across multiple levels and units of analysis in the international security domain. Chief among these are the Nanotechnology, Biotechnology, Robotics and Information and Communication technologies (NBRIC) revolution, the rise of non-state security actors, the emergence of high-end non-traditional security (NTS) threats (such as climate change and emerging infectious disease), the advent of new high-end countermeasures (like ballistic missile defense), the increasingly irrelevance of the chemical and biological weapons non-proliferation regimes, the ongoing threat posed by North Korea, and the appearance of high-end, non-lethal, destructive weapon capabilities (cyber and EMP). Any of these could potentially destabilize the current status quo.

From the perspective of China, these changes present both opportunities and challenges. For example, the rise of non-state security actors presents a threat to the traditional state monopoly on violence. This certainly does not benefit an authoritarian government that can now be brought under surveillance (or even strategically challenged) by non-state actors. However, it also provides China with new export buyers for emerging technologies (such as cyber, precision manufacturing tools, drones, etc.) that could promote domestic economic growth while at the same time empowering others to undertake activities abroad that serendipitously benefit Chinese interests. For these reasons, NATO member states will be watching to see how China responds.

However, China is only part of the story. NATO member states must contend with the larger set of resident and emerging security challenges that threaten the status quo. This has led NATO member states (and many others) to securitize against a widening range of possible security threats to ostensibly protect their security. At times, this has included even partnering with China. But, the consequences of these moves are not all positive. Whereas individual securitizations may increase the security of one referent object (states), they can at the same time increase the insecurity of others (individuals). This state-human security dilemma is itself a major challenge for NATO.

In fact, according to a recent report, global democracy is now at a standstill. This is largely the result of the international community’s post-September 11th penchant for securitization. In the last decade, the transatlantic community has even witnessed major declines across a number of important democracy measures (such as freedom of the press) in key NATO member states and their allies. Efforts to counter the threat posed by NBRICs and traditional Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRNs) also threaten to undermine commercial innovation. This represents a serious challenge to NATO’s economic security in an age where the return to economic growth is necessary to pull Europe and North America out of the global recession.

These pose serious, although often overlooked, security challenges for NATO. The indirect effects of an increasingly securitized NATO might well lead to growing societal pressures within its member states to change course on certain national security policies. The failure by some governments to acquiesce to these calls for change in the name of security could further empower state and non-state actors to challenge the security policies of NATO member states. Not only would this undermine efforts to confront serious security issues abroad, but it could also lead to new security threats on the domestic front (like Anonymous).

Finding the right balance between security and civil liberties will be key for NATO. But, there is no certainty that its member states will be able to do so. If they cannot, NATO could be forced to contend with a growing domestic backlash against its securitizing moves. In that event, it would be even more difficult for NATO member states to counter a rising China. But, whether China could capitalize on such an opportunity is itself a matter of debate. To do so, China will need to overcome its own internal security challenges, which include declining economic growth, widespread environmental degradation, an aging population, and rising ethnic tensions – just to name a few.

So, what is the best path forward for NATO? The answer to this question hinges on the opening question to this article: “Whose security are we talking about?” This is a question that NATO needs to keep at the forefront as its member states respond to an increasingly complex international security landscape.

Michael Edward Walsh is the Director of the Emerging Technologies and High-End Threats Project at the Federation of American Scientists. He is also the President of the Pacific Islands Society, a Senior Fellow at the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of Georgetown University, and a non-resident WSD-Handa Fellow at Pacific Forum CSIS.

$1 Billion for a Nuclear Bomb Tail

The U.S. Air Force plans to spend more than $1 billion on developing a guided tailkit to increase the accuracy of the B61 nuclear bomb.

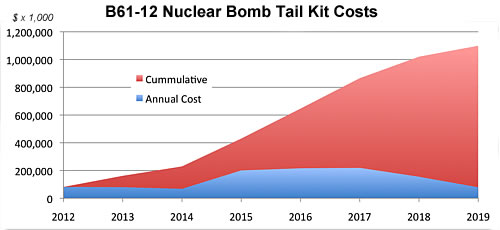

The cost is detailed (to some extent) in the Air Force’s budget request for FY2014, which shows development and engineering through FY2014 and full-scaled production starting in FY2015.

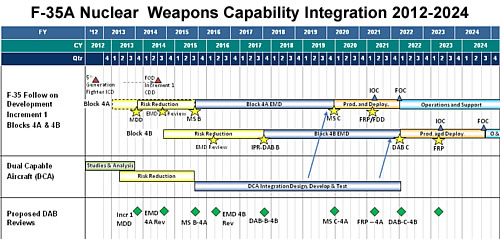

The annual costs increase by nearly 200 percent from $67.9 million in FY2014 to more than $200 million in FY2015. The high cost level will be retained for three years until the project decreases after production ceases in FY2018. Some additional funding is needed after that to complete the integration and certification on (see graph).

Production of the guided tailkit is intended to match completion of the first new B61-12 bomb in 2019, a program that is estimated to cost more than $10 billion. Although the number is a secret, it is thought that the U.S. plans to produce roughly 400 B61-12s.

The expensive guided tailkit is needed, advocates claim, to make it possible to use the 50-kiloton nuclear explosive package from the tactical B61-4 bomb in the new B61-12 against targets that today require the 360-kiloton strategic B61-7 bomb. By increasing accuracy, the B61-12 becomes more useable because it significantly reduces the amount of radioactive fallout created in an attack.

Once deployed in Europe, the B61-12 will also be able to hold at risk targets that the B61-3 and B61-4 bombs currently deployed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and Turkey cannot target.

The B61-12 program will maintain compatibility on all five current B61-capable aircraft (B-2A, B-52H, F-16, F-15E and PA 200). In 2015, integration, design and testing will begin on the new stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter. The Air Force budget request shows that B61-12 integration is scheduled for Block 4A and Block 4B aircraft in 2015-2021 with full operational capability in 2022 – three years after the first B61-12 is scheduled to be delivered (see table).

The combination of the new and more accurate guided B61-12 on the stealthy F-35A will significantly increase the capability of the U.S. non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe. This development is out of tune with U.S. and NATO pledges to reduce the role and reliance on nuclear weapons, and will make it a lot easier for hardliners in the Russian military to reject reductions of Russia’s larger inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense with Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on last week’s announcements on missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

Q: (CB) Last Friday, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

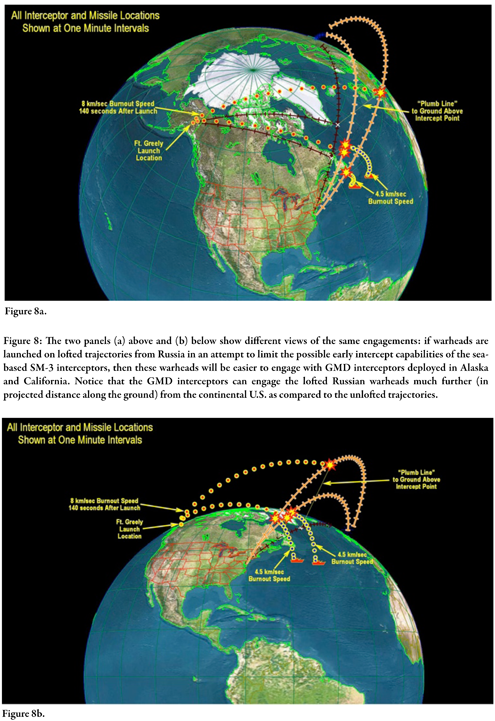

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Figures 8(a) and 8(b) from the FAS Special Report Upsetting the Reset: The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense, by Yousaf Butt and Theodore Postol (p. 27).

Q&A Session on Recent Developments in U.S. and NATO Missile Defense

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked two physicists who are experts in missile defense issues, Dr. Yousaf Butt and Dr. George Lewis, to weigh in on the announcement on March 15, 2013 regarding missile defense by the Obama administration.

Before exploring their reactions and insights, it is useful to identify salient elements of U.S. missile defense and place the issue in context. There are two main strategic missile defense systems fielded by the United States: one is based on large high-speed interceptors called Ground-Based Interceptors or “GBI’s” located in Alaska and California and the other is the mostly ship-based NATO/European system. The latter, European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense is designed to deal with the threat posed by possible future Iranian intermediate- and long-range ballistic missiles to U.S. assets, personnel, and allies in Europe – and eventually attempt to protect the U.S. homeland.

The EPAA uses ground-based and mobile ship-borne radars; the interceptors themselves are mounted on Ticonderoga class cruisers and Arleigh Burke class destroyers. Two land-based interceptor sites in Poland and Romania are also envisioned – the so-called “Aegis-ashore” sites. The United States and NATO have stated that the EPAA is not directed at Russia and poses no threat to its nuclear deterrent forces, but as outlined in a 2011 study by Dr. Theodore Postol and Dr. Yousaf Butt, this is not completely accurate because the system is ship-based, and thus mobile it could be reconfigured to have a theoretical capability to engage Russian warheads.

Indeed, General James Cartwright has explicitly mentioned this possible reconfiguration – or global surge capability – as an attribute of the planned system: “Part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.”

In the 2011 study, the authors focused on what would be the main concern of cautious Russian military planners —the capability of the missile defense interceptors to simply reach, or “engage,” Russian strategic warheads—rather than whether any particular engagement results in an actual interception, or “kill.” Interceptors with a kinematic capability to simply reach Russian ICBM warheads would be sufficient to raise concerns in Russian national security circles – regardless of the possibility that Russian decoys and other countermeasures might defeat the system in actual engagements. In short, even a missile defense system that could be rendered ineffective could still elicit serious concern from cautious Russian planners. The last two phases of the EPAA – when the higher burnout velocity “Block II” SM-3 interceptors come on-line in 2018 – could raise legitimate concerns for Russian military analysts.

A Russian news report sums up the Russian concerns: “[Russian foreign minister] Lavrov said Russia’s agreement to discuss cooperation on missile defense in the NATO Russia Council does not mean that Moscow agrees to the NATO projects which are being developed without Russia’s participation. The minister said the fulfillment of the third and fourth phases of the U.S. ‘adaptive approach’ will enter a strategic level threatening the efficiency of Russia’s nuclear containment forces.” [emphasis added]

With this background in mind, FAS’ Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threat, Charles P. Blair (CB), asked Dr. Yousaf Butt (YB) and Dr. George Lewis (GL) for their input on recent developments on missile defense with eight questions.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Q: (CB)On March 15, Secretary of Defense Hagel announced that the U.S. will cancel the last Phase – Phase 4 – of the European Phased Adaptive Approach (EPAA) to missile defense which was to happen around 2021. This was the phase with the faster SM-3 “Block IIB” interceptors. Will this cancellation hurt the United State’s ability to protect itself and Europe?

A: (YB) No, because the “ability” you mention was always hypothetical. The Achilles’ Heel of all versions of the SM-3 (Block I A/B and Block II A/B) interceptors — indeed of “midcourse” missile defense, in general, is that it is straightforward to defeat the system using cheap decoy warheads. The system simply does not have a robust ability to discriminate a genuine warhead from decoys and other countermeasures. Because the intercepts take place in the vacuum of space, the heavy warhead and light decoys travel together, confusing the system’s sensors. The Pentagon’s own scientists at the Defense Science Board said as much in 2011, as did the National Academy of Sciences earlier this year.

Additionally, the system has never been successfully tested in realistic conditions stressed by the presence of decoys or other countermeasures. The majority of the system would be ship-based and is not known to work beyond a certain sea-state: as you might imagine, it becomes too risky to launch the interceptors if the ship is pitching wildly.

So any hypothetical (possibly future) nuclear-armed Middle Eastern nation with ICBMs could be a threat to the Unites States or Europe whether we have no missile defenses, have just Block I interceptors, or even the Block II interceptors. Since the interceptors would only have offered a false sense of security, nothing is lost in canceling Phase 4 of the EPAA. In fact, the other phases could also be canceled with no loss to U.S. or NATO security, and offering considerable saving of U.S. taxpayer’s money.

Q: (CB) What about Iran and its alleged desire to build ICBMs? Having just launched a satellite in January, could such actions act as a cover for an ICBM?

A: (YB) The evidence does not point that way at all. It points the other way. For instance, the latest Congressional Research Service (CRS) report on Iran’s missile program observes: (emphasis added)

“Iran also has a genuine and ambitious space launch program, which seeks to enhance Iran’s national pride, and perhaps more importantly, its international reputation as a growing advanced industrial power. Iran also sees itself as a potential leader in the Middle East offering space launch and satellite services. Iran has stated it plans to use future launchers for placing intelligence gathering satellites into orbit, although such a capability is a decade or so in the future. Many believe Iran’s space launch program could mask the development of an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – with ranges in excess of 5,500 km that could threaten targets throughout Europe, and even the United States if Iran achieved an ICBM capability of at least 10,000 km. ICBMs share many similar technologies and processes inherent in a space launch program, but it seems clear that Iran has a dedicated space launch effort and it is not simply a cover for ICBM development. Since 1999, the U.S. Intelligence Community (IC) has assessed that Iran could test an ICBM by 2015 with sufficient foreign assistance, especially from a country such as China or Russia (whose support has reportedly diminished over the past decade). It is increasingly uncertain whether Iran will be able to achieve an ICBM capability by 2015 for several reasons: Iran does not appear to be receiving the degree of foreign support many believe would be necessary, Iran has found it increasingly difficult to acquire certain critical components and materials because of sanctions, and Iran has not demonstrated the kind of flight test program many view as necessary to produce an ICBM.”

Furthermore, the payload of Iran’s space launch vehicles is very low compared to what would be needed for a nuclear warhead — or even a substantial conventional warhead. For instance, Omid, Iran’s first satellite weighed just 27 kg [60 pounds] and Rasad-1, Iran’s second satellite weighed just 15.3 kilograms [33.74 pound], whereas a nuclear warhead would require a payload capacity on the order of 1000 kilograms. Furthermore, since launching an ICBM from Iran towards the United States or Europe requires going somewhat against the rotation of Earth the challenge is greater. As pointed out by missile and space security expert Dr. David Wright, an ICBM capable of reaching targets in the United States would need to have a range longer than 11,000 km. Drawing upon the experience of France in making solid-fuel ICBMs, Dr. Wright estimates it may take 40 years for Iran to develop a similar ICBM – assuming it has the intention to kick off such an effort. A liquid fueled rocket could be developed sooner, but there is little evidence in terms of rocket testing that Iran has kicked off such an effort.

In any case, it appears that informed European officials are not really afraid of any hypothetical Iranian missiles. For example, the Polish foreign minister, Radoslaw Sikorski, once made light of the whole scenario telling Foreign Policy, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” As if to emphasize that point, the Europeans don’t appear to be pulling their weight in terms of funding the system. “We love the capability but just don’t have the money,” one European military official stated in reference to procuring the interceptors.

Similarly, the alleged threat from North Korea is also not all that urgent.

It seems U.S. taxpayers are subsidizing a project that will have little national security benefits either for the United States or NATO countries. In contrast, it may well create a dangerous false sense of security. It has already negatively impacted ties with Russia and China.

Q: (CB) Isn’t Iran’s alleged nuclear weapons program a big concern in arguing for a missile defense? Prime Minister Netanyahu of Israel said Iran may cross some red-line in the summer?

A: (YB) Iran’s nuclear program could be a concern, but the latest report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) says Iran has not even decided to make nuclear weapons yet. Building, testing and miniaturizing a warhead to fit on a missile takes years – after a country decides to do so. In any case, no matter how scary that hypothetical prospect, one would not want a missile defense system that could be easily defeated to address that alleged eventual threat. Even if you believe the threat exists now, you may want a system that is effective, not a midcourse system that has inherent flaws.

Incidentally, the DNI’s report explicitly states: “we assess Iran could not divert safeguarded material and produce a weapon-worth of WGU [weapons grade uranium] before this activity is discovered.” As for the red-line drawn by Prime Minister Netanyahu: his track-record on predicting Iranian nuclear weaponization has been notoriously bad. As I point out in a recent piece for Reuters, in 1992 Mr. Netanyahu said Iran was three to five years from a bomb. I assess he is still wrong, more than 20 years later.

Lastly, even if Iran (or other nations) obtained nuclear weapons in the future, they can be delivered in any number of ways- not just via missiles. In fact, nuclear missiles have the benefit of being self-deterring – nations are actually hesitant to use nuclear weapons if they are mated to missiles. Other nations know that the United States can pinpoint the launch sites of missiles. The same cannot be said of a nuclear device placed in a sailboat, a reality that could precipitate the use of that type of device due to the lack of attribution. So one has to carefully consider if it makes sense to dissuade the placement of nuclear weapons on missiles. If an adversarial nation has nuclear weapons it may be best to have them mated to missiles rather than boats.

Q: (CB) It seems that the Russians are still concerned about the missile defense system, even after Defense Secretary Hagel said that the fourth phase of EPAA plan is canceled. Why are they evidently still concerned?

A: (YB) The Russians probably have four main concerns with NATO missile defense, even after the cancellation of Phase 4 of EPAA. For more details on some of these please see the report Ted Postol and I wrote.

1. The first is geopolitical: the Russians have never been happy about the Eastward expansion of NATO and they see joint U.S.-Polish and U.S.-Romanian missile defense bases near their borders as provocative. This is not to say they are right or wrong, but that is most likely their perception. These bases are to be built before Phase 4 of the EPAA, so they are still in the plans.

2. The Russians do not concur with the alleged long-range missile threat from Iran. One cannot entirely blame them when the Polish foreign minister himself makes light of the alleged threat saying, “If the mullahs have a target list we believe we are quite low on it.” Russian officials are possibly confused and their military analysts may even be somewhat alarmed, mulling what the real intent behind these missile defense bases could be, if – in their assessment – the Iran threat is unrealistic, as in fact was admitted to by the Polish foreign minister. The Russians also have to take into account unexpected future changes which may occur on these bases, for instance: a change in U.S. or Polish or Romanian administrations; a large expansion of the number or types of interceptors; or, perhaps even nuclear-tipped interceptors (which were proposed by former Defense Secretary Rumsfeld about ten years ago).

3. Russian military planners are properly hyper-cautious, just like their counterparts at the Pentagon, and they must assume a worst-case scenario in which the missile defense system is assumed to be effective, even when it isn’t. This concern likely feeds into their fear that the legal balance of arms agreed to in New START may be upset by the missile defense system.

Their main worry could be with the mobile ship-based platforms and less with the European bases, as explained in detail in the study Ted Postol and I did. Basically, the Aegis missile defense cruisers could be placed off of the East Coast of the U.S. and – especially with Block IIA/B interceptors –engage Russian warheads. Some statements from senior U.S. officials probably play into their fears. For instance, General Cartwright has been quoted as saying, “part of what’s in the budget is to get us a sufficient number of ships to allow us to have a global deployment of this capability on a constant basis, with a surge capacity to any one theater at a time.” To certain Russian military planners’ ears that may not sound like a limited system aimed at a primitive threat from Iran.

Because the mobile ship-based interceptors (hypothetically placed off of the U.S. East Coast ) could engage Russian warheads, Russian officials may be able claim this as an infringement on New START parity.

Missile defenses that show little promise of working well can, nevertheless, alter perceptions that the strategic balance between otherwise well-matched states is stable. Even when missile defenses reveal that they possess little, if any technical capabilities, they can still cause cautious adversaries and competitors to react as if they might work. The United States’ response to the Cold War era Soviet missile defense system was similarly overcautious.

4. Finally, certain Russian military planners may worry about the NATO EPAA missile defense system because in Phase 3, the interceptors are to be based on the SM-3 Block IIA booster. The United States has conducted research using this same type of rocket booster as the basis of a hypersonic-glide offensive strike weapon called ArcLight. Because such offensive hyper-glide weapons could fit into the very same vertical launch tubes – on the ground in Poland and Romania, or on the Aegis ships – used for the defensive interceptors, the potential exists for turning a defensive system into an offensive one, in short order. Although funding for ArcLight has been eliminated in recent years, Russian military planners may continue to worry that perhaps the project “went black” [secret], or that it may be resuscitated in the future. In fact, a recent Federal Business Opportunity (FBO) for the Department of the Navy calls for hypersonic weapons technologies that could fit into the same Mk. 41 Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes that the SM-3 missile defense interceptors are also placed in.

To conclude, advocates of missile defense who say we need cooperation on missile defense to improve ties with Russia have the logic exactly backward: In large part, the renewed tension between Russia and the United States is about missile defense. Were we to abandon this flawed and expensive idea, our ties with Russia — and China — would naturally improve. And, in return, they could perhaps help us more with other foreign policy issues such as Iran, North Korea, and Syria. As it stands, missile defense is harming bilateral relations with Russia and poisoning the well of future arms control.

Q: (CB) Adding to the gravity of Secretary Hagel’s announcement , last week China expressed worry about Ground-Based Interceptors, the Bush administration’s missile defense initiative in Poland discarded by the Obama administration in 2009, in favor of Phase 4 of the EPAA. Why is there concern with not only the Aegis ship-based system, but also the GBIs on the West Coast?

A: (YB) Like the Russians, Chinese military analysts are also likely to assume the worst-case scenario for the system (ie. that it will work perfectly) in coming up with their counter response . Possessing a much smaller nuclear arsenal than Russia or the United States, to China, even a few interceptors can be perceived as making a dent in their deterrent forces. And I think the Chinese are likely worried about both the ship-based Aegis system as well as the West Coast GBIs.

And this concern on the part of the Chinese is nothing new. They have not been as vocal as the Russians, but it is evident they were never content with U.S. and NATO plans. For instance, the 2009 Bipartisan Strategic Posture Commission pointed out that “China may already be increasing the size of its ICBM force in response to its assessment of the U.S. missile defense program.” Such stockpile increases, if they are taking place, will probably compel India, and, in turn, Pakistan to also ramp up their nuclear weapon numbers.

The Chinese may also be looking to the future and think that U.S. defenses may encourage North Korea to field more missiles than it may originally have been intending – if and when the North Koreans make long range missiles – to make sure some get through the defense system. This would have an obvious destabilizing effect in East Asia which the Chinese would rather avoid.

Some U.S. media outlets have also said the ship-based Aegis system could be used against China’s DF-21D anti-ship missile, when the official U.S. government position has always been that the system is only intended only against North Korea (in the Pacific theater). Such mission creep could sound provocative to the Chinese, who were told that the Aegis system is not “aimed at” China.

In reality, while the Aegis system’s sensors may be able to help track the DF-21D it is unlikely that the interceptors could be easily modified to work within the atmosphere where the DF-21D’s kill vehicle travels. (It could perhaps be intercepted at apogee during the ballistic phase). A recent CRS report was quite explicit that the DF-21D is a threat which remains unaddressed in the Navy: “No Navy target program exists that adequately represents an anti-ship ballistic missile’s trajectory,’ Gilmore said in the e-mail. The Navy ‘has not budgeted for any study, development, acquisition or production’ of a DF-21D target, he said.”

Chinese concerns about U.S. missile defense systems are also a source of great uncertainty, reducing Chinese support for promoting negotiations on the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). China’s leaders may wish to maintain the option of future military plutonium production in response to U.S. missile defense plans.

The central conundrum of midcourse missile defense remains that while it creates incentives for adversaries and competitors of the United States to increase their missile stockpiles, it offers no credible combat capability to protect the United States or its allies from this increased weaponry.

Q: (CB) Will a new missile defense site on the East Coast protect the United States? What would be the combat effectiveness of an East Coast site against an assumed Iranian ICBM threat?

A: (GL) I don’t see any real prospect for even starting a program for interceptors such as the [East Coast site] NAS is proposing any time soon in the current budget environment, and even if they did it probably would not be available until the 2020s. The recent announcement of the deployment of additional GBI interceptors is, in my view, just cover for getting rid of the Block II Bs, and was chosen because it was relatively ($1+ billion) inexpensive and could be done quickly.

The current combat effectiveness of the GBIs against an Iranian ICBM must be expected to be low. Of course there is no current Iranian ICBM threat. However, the current GMD system shows no prospect of improved performance against any attacker that takes any serious steps to defeat it as far out in time, as plans for this system are publicly available. Whether the interceptors are based in Alaska or on the East Coast makes very little difference to their performance.

Q: (CB) There were shortcomings reported by the Defense Science Board and the National Academies regarding the radars that are part of the system. Has anything changed to improve this situation?

A: (GL) With respect to radars, the main point is that basically nothing has happened. The existing early warning radars can’t discriminate [between real warheads and decoys]. The only radar that could potentially contribute to discrimination, the SBX, has been largely mothballed.

Q: (CB) Let’s say the United States had lots of money to spend on such a system, would an East Coast site have the theoretical ability to engage Russian warheads? Regardless of whether Russia could defeat the system with decoys or countermeasures, does the system have an ability to reach or engage the warheads? In short, could such a site be a concern for Russia?

A: (YB) If you have a look at Fig 8(a) and 8(b) in the report Ted Postol and I wrote you’ll see pretty clearly why an East Coast site might be a concern for Russia, especially with faster interceptors that are proposed for that site. Now I’m not saying it necessarily should be a concern – because they can defeat the system rather easily – but it may be. Whether they object to it or not vocally depends on other factors also. For instance, such a site will obviously not be geopolitically problematic for the Russians.

Charles P. Blair is the Senior Fellow on State and Non-State Threats at the Federation of American Scientists.

Dr. Yousaf Butt, a nuclear physicist, is professor and scientist-in-residence at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. George N. Lewis is a senior research associate at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University.

Additional Delays Expected in B61-12 Nuclear Bomb Schedule

The B61-7, which completed a limited life-extension program in 2006, will be retired by the more extensive B61-12 program.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) expects additional delays in production and delivery of the B61-12 nuclear bomb as a result of so-called sequestration budget cuts.

During testimony before the Hours Energy and Water Subcommittee last week, NNSA’s Acting Administrator Neile Miller said an expected $600 million reduction of the agency’s weapons activities budget could “slow the B61-12 LEP” and other weapons programs.

The Nuclear Posture Review set delivery of the first B61-12 for 2017, but that timeline has since slipped to 2019. Miller did not say how long production could be delayed but it could potentially slip into the 2020s.

The B61 LEP is already the most expensive and complex warhead modernization program since the Cold War, with cost estimates ranging from $8 billion to more than $10 billion, up from $4 billion in 2010. The price hike has triggered Congressional questions and efforts to trim the program. B61-12 proponents argue the weapon is needed to provide extended nuclear deterrence to NATO and Asian allies, but the mission in Europe is fading out and a cheaper alternative could be to retaining the B61-7 for the B-2A bomber and retire other B61 versions.

The B61-12 program extends the life of the tactical B61-4 warhead, incorporates selected components from three other B61 versions (B61-3, B61-7, and B61-10), adds unknown new safety and security features, and adds a guided tail kit to increase the accuracy and target kill capability of the B61-12 compared with the B61-4.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons Discussed in Warsaw

The conference was held in this elaborate room at the Intercontinental Warsaw hotel.

By Hans M. Kristensen