Strategy: Directing the Instruments of National Power

The tools that can be used to assert national power and influence have often been summarized by the acronym DIME — Diplomatic, Informational, Military, and Economic.

But “US policy makers and strategists have long understood that there are many more instruments involved in national security policy development and implementation,” according to a new Joint Chiefs of Staff publication on the formulation of national strategy.

“New acronyms such as MIDFIELD — Military, Informational, Diplomatic, Financial, Intelligence, Economic, Law, and Development — convey a much broader array of options for the strategist and policymaker to use.” See Strategy, Joint Doctrine Note 1-18, April 25, 2018.

The pursuit of strategic goals naturally entails costs and risks, the document said.

“Risks to the strategy are things that could cause it to fail, and they arise particularly from assumptions that prove invalid in whole or in part. Risks from the strategy are additional threats, costs, or otherwise undesired consequences caused by the strategy’s implementation.”

Homeland Defense: An Update

The Joint Chiefs of Staff last week issued updated doctrine on homeland defense, including new guidance on cyberspace operations, unmanned aerial systems, defense support of civil authorities, and even a bit of national security classification policy.

See Joint Publication 3-27, Homeland Defense, April 10, 2018.

Homeland defense (HD) is related to homeland security, but it is a military mission that emphasizes protection of the country from external threats and aggression.

“The purpose of HD is to protect against incursions or attacks on sovereign US territory, the domestic population, and critical infrastructure and key resources as directed,” according to JP 3-27.

Homeland defense may also function domestically, subject to relevant law and policy. “Threats planned, prompted, promoted, caused, or executed by external actors may develop or take place inside the homeland. The reference to external threats does not limit where or how attacks may be planned and executed.”

Effective homeland defense, whether abroad or at home, requires sharing of information with civilian authorities, international partners, and others.

In an odd editorial remark, the new DoD doctrine says that DoD itself keeps too much information behind a classified firewall to the detriment of information sharing.

“DOD’s over-reliance on the classified information system for both classified and unclassified information is a frequent impediment. . .,” the Joint Chiefs said.

“DOD information should be appropriately secured, shared, and made available throughout the information life cycle to appropriate mission partners to the maximum extent allowed by US laws and DOD policy. Critical to transparency of information sharing is the proper classification of intelligence and information,” the document said, implying that such proper classification cannot be taken for granted.

Nuclear Weapons Maintenance as a Career Path

The US Air Force has published new guidance for training military and civilian personnel to maintain nuclear weapons as a career specialty.

See Nuclear Weapons Career Field Education and Training Plan, Department of the Air Force, April 1, 2018.

An Air Force nuclear weapons specialist “inspects, maintains, stores, handles, modifies, repairs, and accounts for nuclear weapons, weapon components, associated equipment, and specialized/general test and handling equipment.” He or she also “installs and removes nuclear warheads, bombs, missiles, and reentry vehicles.”

A successful Air Force career path in the nuclear weapons specialty proceeds from apprentice to journeyman to craftsman to superintendent.

“This plan will enable training today’s workforce for tomorrow’s jobs,” the document states, confidently assuming a future that resembles the present.

Meanwhile, however, the Air Force will also “support the negotiation of, implementation of, and compliance with, international arms control and nonproliferation agreements contemplated or entered into by the United States Government,” according to a newly updated directive.

See Air Force Policy Directive 16-6, International Arms Control and Nonproliferation Agreements and the DoD Foreign Clearance Program, 27 March 2018.

US Air Force Limits Media Access, Interviews

Updated below

The US Air Force is suspending media embeds, base visits and interviews “until further notice” and it “will temporarily limit the number and type of public engagements” by public affairs officers and others while they are retrained to protect sensitive information, according to guidance obtained by Defense News.

“In line with the new National Defense Strategy, the Air Force must hone its culture of engagement to include a heightened focus on practicing sound operational security,” the new guidance memo said.

“As we engage the public, we must avoid giving insights to our adversaries which could erode our military advantage. We must now adapt to the reemergence of great power competition and the reality that our adversaries are learning from what we say in public.”

Notably, the new Air Force guidance does not distinguish between classified and unclassified information. Nor does it define the scope of “sensitive operational information” which must be protected.

The March 1, 2018 memo was reported (and posted) in “Air Force orders freeze on public outreach” by Valerie Insinna, David B. Larter, and Aaron Mehta, Defense News, March 12.

As it happens, a counter-argument in favor of enhanced Air Force release of information was made just last week by Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson.

“The Air Force has an obligation to communicate with the American public, including Airmen and families, and it is in the national interest to communicate with the international public,” the Secretary stated in a March 8 directive.

“Through the responsive release of accurate information and imagery to domestic and international audiences, public affairs puts operational actions in context, informs perceptions about Air Force operations, helps undermine adversarial propaganda efforts and contributes to the achievement of national, strategic and operational objectives.”

“The Air Force shall respond to requests for releasable information and material. To maintain the service’s credibility, commanders shall ensure a timely and responsive flow of such information,” she wrote.

But by the same token, unwarranted delays or interruptions in the public flow of Air Force information threaten to undermine the service’s credibility. See Public Affairs Management, Air Force Policy Directive 35-1, March 8, 2018.

Update: “It’s not a freeze. We continue to do many press engagements daily,” said [Air Force] Brig. Gen. Ed Thomas. We are fully committed — and passionate about — our duty and obligation to communicate to the American people.” See The Air Force’s PR Fiasco: How a plan to tighten security backfired, Washington Examiner, March 14, 2018.

Army Visual Signals

Soldiers need to be able to communicate on a noisy, dangerous battlefield even when conventional means of communication are unavailable.

To help meet that need, the US Army has just updated its compilation of hand and flag signals.

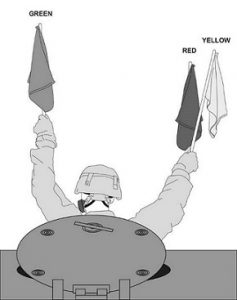

One configuration of flags signifies “Chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear hazard present”:

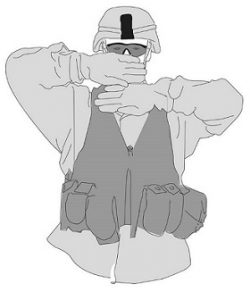

Or a soldier may need to signal “I do not understand,” as follows:

See Visual Signals for Armor Fighting Vehicles (Combined Arms), GTA 17-02-019, US Army, February 2018.

The Expanding Secrecy of the Afghanistan War

Last year, dozens of categories of previously unclassified information about Afghan military forces were designated as classified, making it more difficult to publicly track the progress of the war in Afghanistan.

The categories of now-classified information were tabulated in a memo dated October 31, 2017 that was prepared by the staff of the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR), John Sopko.

In the judgment of the memo authors, “None of the material now classified or otherwise restricted discloses information that could threaten the U.S. or Afghan missions (such as detailed strategy, plans, timelines, or tactics).”

But “All of the [newly withheld] data include key metrics and assessments that are essential to understanding mission success for the reconstruction of Afghanistan’s security institutions and armed forces.”

So what used to be available that is now being withheld?

“It is basically casualty, force strength, equipment, operational readiness, attrition figures, as well as performance assessments,” said Mr. Sopko, the SIGAR.

“Using the new [classification criteria], I would not be able to tell you in a public setting or the American people how their money is being spent,” Mr. Sopko told Congress at a hearing last November.

The SIGAR staff memo tabulating the new classification categories was included as an attachment for the hearing record, which was published last month. See Overview of 16 Years of Involvement in Afghanistan, hearing before the House Government Oversight and Reform Committee, November 1, 2017.

In many cases, the information was classified by NATO or the Pentagon at the request of the Government of Afghanistan.

“Do you think that it is an appropriate justification for DOD to classify previously unclassified information based on a request from the Afghan Government?,” asked Rep. Val Demings (D-FL). “Why or why not?”

“I do not because I believe in transparency,” replied Mr. Sopko, “and I think the loss of transparency is bad not only for us, but it is also bad for the Afghan people.”

“All of this [now classified] material is historical in nature (usually between one and three months old) because of delays incurred by reporting time frames, and thus only provides ‘snapshot’ data points for particular periods of time in the past,” according to the SIGAR staff memo.

“All of the data points [that were] classified or restricted are ‘top-line’ (not unit-level) data. SIGAR currently does not publicly report potentially sensitive, unit-specific data.”

Yesterday at a hearing of the House Armed Services Committee, Rep. Walter Jones (R-NC) asked Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis about the growing restrictions on information about the war in Afghanistan.

“We are now increasing the number of our troops in Afghanistan, and after 16 years, the American people have a right to know of their successes. Some of that, I’m sure it is classified information, which I can understand. But I also know that we’re not getting the kind of information that we need to get to know what successes we’re having. And after 16 years, I do not think we’re having any successes,” Rep. Jones said.

Secretary Mattis said that the latest restriction of unclassified information about the extent of Taliban or government control over Afghanistan that was withheld from the January 2018 SIGAR quarterly report had been “a mistake.” He added, “That information is now available.” But Secretary Mattis did not address the larger pattern of classifying previously unclassified information about Afghan forces that was discussed at the November 2017 hearing.

Army Sketches Future Cyberspace Operations

The U.S. Army this week published an overview of future military cyberspace operations. See The U.S. Army Concept for Cyberspace and Electronic Warfare Operations 2025-2040, TRADOC Pamphlet 525-8-6, 9 January 2018.

The new Army publication is intended to promote development of cyber capabilities, to foster integration with other military functions, to shape recruitment, and to guide technology development and acquisition. It addresses defense against cyber threats as well as offensive cyber activities.

Proliferation of cyber threats is eroding the benefits of US superiority in conventional military power, the document said.

“The Army faces a complex and challenging environment where the expanding distribution of cyberspace and EMS [electromagnetic spectrum] technologies will continue to narrow the combat power advantage that the Army has had over potential adversaries.”

“Adversaries will conduct complex cyberspace attacks integrated with military operations or independent of traditional military operations.”

“Since every device presents a potential vulnerability, this trend represents an exponential growth of targets through which an adversary could access Army operational networks, systems, and information.”

“Conversely, it presents opportunities for the enhanced synchronization of Army technologies and information to exploit adversary dependencies on cyberspace.”

“If deterrence fails, Army forces isolate, overwhelm, and defeat adversaries in cyberspace and the EMS to meet the commander’s objectives.”

“These [Army] capabilities exploit adversary systems to facilitate intelligence collection, target adversary cyberspace and EMS functions, and create first order effects. Cyberspace and EW [electronic warfare] operations also create cascading effects across multiple domains to affect weapons systems, command and control processes, critical infrastructure, and key resources to outmaneuver adversaries physically and cognitively, applying combined arms in and across all domains.”

Military action in cyberspace is an evolving field that may have overtaken existing law or convention.

“Many effects of cyberspace operations require considerable legal and policy review,” the Army document said.

Reversing Course, DoD Will Retain Cluster Munitions

The Department of Defense last month abandoned a 2008 policy that would have reduced the U.S. inventory of cluster munitions and imposed strict new safety and quality control standards on these anti-personnel weapons, which have been implicated in numerous civilian fatalities.

“We must not lose our qualitative and quantitative competitive advantage against potential adversaries that seek operational and tactical advantages against the United States and its allies and partners,” wrote Deputy Secretary of Defense Patrick M. Shanahan in a November 30, 2017 memo establishing the new policy. Therefore, “the Department will retain cluster munitions currently in active inventories until the capabilities they provide are replaced with enhanced and more reliable munitions.”

The new DoD policy “essentially reversed the 2008 policy,” according to a newly updated review from the Congressional Research Service.

Where the previous policy issued by Defense Secretary Robert Gates in 2008 had “established an unwaiverable requirement that cluster munitions used after 2018 must leave less than 1% of unexploded submunitions on the battlefield,” that requirement is no longer operative and no new deadline for reducing associated risks has been set.

“Cluster munitions have been highly criticized internationally for causing a significant number of civilian deaths, and efforts have been undertaken to ban and regulate their use,” CRS wrote.

Furthermore, cluster munitions today may be an anachronism, the CRS report said. “Given current and predicted future precision weaponry trends, cluster munitions might be losing their military relevance–much as chemical weapons did between World War I and World War II.” See Cluster Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress, December 13, 2017.

Other new and updated publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Mixed-Oxide Fuel Fabrication Plant and Plutonium Disposition: Management and Policy Issues, updated December 14, 2017

Defense Spending Under an Interim Continuing Resolution: In Brief, updated December 15, 2017

Federal Procurement Law & Natural Disasters, CRS Legal Sidebar, December 14, 2017

The Net Neutrality Debate: Access to Broadband Networks, updated December 14, 2017

The Purple Heart: Background and Issues for Congress, updated December 15, 2017

Pentagon Reaffirms Policy on Scientific Integrity

“It is DoD policy to support a culture of scientific and engineering integrity,” according to a Department of Defense directive that was reissued last week.

This is in large part a matter of self-interest, since the Department depends upon the availability of competent and credible scientists and engineers.

“Science and engineering play a vital role in the DoD’s mission, providing one of several critical inputs to policy and systems acquisition decision making. The DoD recognizes the importance of scientific and engineering information, and science and engineering as methods for maintaining and enhancing its effectiveness and its credibility with the public. The DoD is dedicated to preserving the integrity of the scientific and engineering activities it conducts.”

Several practical consequences flow from this policy that are spelled out in the directive, including:

–Permitting publication of fundamental research results

–Making scientific and engineering information available on the Internet

–Making articulate and knowledgeable spokespersons available to the media upon request for interviews on science and engineering

The policy further states that:

–Federal scientists and engineers may speak to the media and to the public about scientific and technical matters based on their official work with appropriate coordination with the scientists’ or engineers’ organizations.

–DoD approval to speak to the media or the public shall not be unreasonably delayed or withheld.

–In no circumstance may DoD personnel ask or direct scientists or engineers to alter or suppress their professional findings, although they may suggest that factual errors be corrected.

The reaffirmation of such principles, which were originally adopted in 2012, does not guarantee their consistent application in practice. But it does provide a point of reference and a foothold for defending scientific integrity in the Department.

See Scientific and Engineering Integrity, DoD Instruction 3200.20, July 26, 2012, Incorporating Change 1, December 5, 2017.

Military Operations Face Growing Transparency

Soldiers and Marines fighting in populated urban environments have to assume that their actions are being closely monitored by the public, according to new military doctrine published last week. They need to have “an expectation of observation.”

Increased transparency surrounding military operations in populated areas must be anticipated and factored into operational plans, the new doctrine instructs.

“Soldiers/Marines are likely to have their activities recorded in real time and shared instantly both locally and globally. In sum, friendly forces must have an expectation of observation for many of their activities and must employ information operations to deal with this reality effectively.”

This can be a matter of some urgency considering that “Under media scrutiny, the action of one Soldier/Marine has significant strategic implications.”

See Urban Operations, ATP 3-06, US Army, US Marine Corps, December 7, 2017.

“Currently more than 50 percent of the world population lives in urban areas and is likely to increase to 70 percent by 2050, making military operations in cities both inevitable and the norm,” the document states.

Inevitable or not, urban military combat presents a variety of challenges.

“Urban operations often reduce the relative advantage of technological superiority, weapons ranges, and firepower.”

“Moreover, because there is risk of high civilian casualties, commanders are generally required to protect civilians, render aid, and minimize damage to infrastructure. These requirements can reduce resources available to defeat the enemy, often creating difficult choices for the commander.”

“Military operations that devastate large amounts of infrastructure may result in more civilian casualties than directly caused by combat itself. Excessive U.S. destruction of infrastructure that causes widespread suffering amongst people may turn initially neutral or positive sentiment toward U.S. forces into hostility that can rapidly mobilize populations and change the nature of the military problem.”

“Destroying an urban area to save it is not an option for commanders.”

What is an Act of War in Cyberspace?

What constitutes an act of war in the cyber domain?

It’s a question that officials have wrestled with for some time without being able to provide a clear-cut answer.

But in newly-published responses to questions from the Senate Armed Services Committee, the Pentagon ventured last year that “The determination of what constitutes an ‘act of war’ in or out of cyberspace, would be made on a case-by-case and fact-specific basis by the President.”

“Specifically,” wrote then-Undersecretary of Defense (Intelligence) Marcel Lettre, “cyber attacks that proximately result in a significant loss of life, injury, destruction of critical infrastructure, or serious economic impact should be closely assessed as to whether or not they would be considered an unlawful attack or an ‘act of war.'”

Notably absent from this description is election-tampering or information operations designed to disrupt the electoral process or manipulate public discourse.

Accordingly, Mr. Lettre declared last year that “As of this point, we have not assessed that any particular cyber activity [against] us has constituted an act of war.”

See Cybersecurity, Encryption and United States National Security Matters, Senate Armed Services Committee, September 13, 2016 (published September 2017), at p. 85.

See related comments from Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Joseph Dunford in U.S. National Security Challenges and Ongoing Military Operations, Senate Armed Services Committee, September 22, 2016 (published September 2017), at pp. 56-57.

In January 2017, outgoing Obama DHS Secretary Jeh Johnson for the first time designated the U.S. election system as critical infrastructure. “Given the vital role elections play in this country, it is clear that certain systems and assets of election infrastructure meet the definition of critical infrastructure, in fact and in law,” he wrote. It follows that an attack on the electoral process could now be considered an attack on critical infrastructure and, potentially, an act of war.

“Russia engaged in acts of war against America, not with bullets and bombs, but through a modern form of warfare, a cyberattack on our democracy,” opined Allan Lichtman, a history professor at American University, in a letter published in the latest issue of the New York Review of Books.

Not so fast, replied Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg: “The US is not now in a legal state of war with Russia despite that country’s attempts to affect the 2016 election.”

The current issue of the US Army’s Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin (Oct-Dec 2017) includes an article on Recommendations for Intelligence Staffs Concerning Russian New Generation Warfare by MAJ Charles K. Bartles (at pp. 10-17).

Army Operations: The New Operational Environment

Other nations, including current and potential adversaries, possess military capabilities that now match or exceed those of the United States, according to a new US Army doctrinal publication.

“Today’s operational environment presents threats to the Army and joint force that are significantly more dangerous in terms of capability and magnitude than those we faced in Iraq and Afghanistan. Major regional powers like Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea are actively seeking to gain strategic positional advantage. These nations, and other adversaries, are fielding capabilities to deny long-held U.S. freedom of action in the air, land, maritime, space, and cyberspace domains and reduce U.S. influence in critical areas of the world.”

“In some contexts they already have overmatch or parity, a challenge the joint force has not faced in twenty-five years.”

That assessment appears in the Foreword to the newly updated US Army Field Manual 3.0 on Operations that was officially released today.

The Field Manual describes the conduct of operations in the new environment, with notably new material on the cyber and space domains.

“Threat operations [by adversaries] in cyberspace are often less encumbered by treaty, law, and policy restrictions than those imposed on U.S. forces, which may allow adversaries or enemies an initial advantage,” the manual states.

The unclassified field manual was released along with two supporting volumes:

ADP 3-0. Operations, Army Doctrine Publication, October 2017, and

ADRP 3-0. Operations, Army Doctrine Reference Publication, October 2017

Last week, Secretary of Defense James Mattis issued a memorandum to all military personnel and DoD employees warning against leaks of classified or otherwise restricted defense information.

“It is a violation of our oath to divulge, in any fashion, non-public DoD information, classified or unclassified, to anyone without the required security clearance as well as a specific need to know in performance of their duties,” he wrote. A copy of the memo was obtained by Military Times. (A security clearance is not required for unclassified information.)

Yet also last week, Secretary Mattis himself disclosed new information that about US rules of engagement that is normally not published, the New York Times reported. A Pentagon spokesman denied that the disclosure would place US forces at risk, or help the enemy. See “Mattis Discloses Part of Afghanistan Battle Plan, but It Hasn’t Yet Been Carried Out” by Thomas Gibbons-Neff, October 6.