Navy Lab’s Future Is At Risk, Report Warns

Updated below

The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) boasts an amazing record of achievement but its future is in jeopardy, according to a newly disclosed report of the Naval Research Advisory Committee that was suppressed by the Navy.

NRL is widely recognized as a world class research institution that has made transformational discoveries in many scientific fields from space science to marine biology, and it pioneered key technologies such as the Global Positioning System.

But that reputation is based mostly on past work. In 2018, the Secretary of the Navy tasked the Naval Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) to assess the Lab’s future role and effectiveness.

“NRL has a proud history of accomplishment,” the NRAC report concluded. “However, there are clear threats for its future.” A copy of the November 2018 interim report was obtained by Secrecy News after the Navy refused to release it.

One problem is that the physical state of the Naval Research Laboratory is a mess.

“We found that most of the facilities are in incredibly poor condition,” the NRAC report said. “Various NRL facilities and laboratories are experiencing leaks, heating and air conditioning problems, and other infrastructure failures.”

“Poor facilities lead to inefficient research, safety issues, and negative motivation for potential researchers,” NRAC said.

(On this point, at least, the Navy concurs with the advisory panel. “Due to their advanced age and deterioration, funds are planned to restore/modernize various laboratory facilities at the Naval Research Laboratory,” according to the Navy’s budget request for FY 2021.)

More subtly, NRL lacks a clear vision of its own future, NRAC said. “The bedrock of any organization is its strategy as captured in a formal strategic plan.” But NRL does not have a strategic plan for science and technology, the report said. Remarkably, neither does the Navy as a whole. Consequently, the NRL research program, buffeted by current needs and controversies, risks losing sight of more ambitious, long-term scientific goals.

Institutionally, the NRL has been isolated from Navy leadership to the detriment of both, according to the NRAC.

“Senior naval leaders are not connected directly with NRL nor do they participate in any routine meetings to keep them informed of specific areas of scientific import.”

“Senior naval leaders (i.e., SECNAV, CNO, CMC, ASNs, VCNO, 4-star Admirals, major N-codes and HQMC codes) get routine briefings on many key topics. They are vocal that the U.S. is losing ground to potential adversaries in the area of science and technology. They emphasize the criticality of S&T in national defense strategies; but NRL, the Navy’s corporate scientific laboratory, is not present at these briefings.”

If scientific advancement is to have a role in the Navy of the future, Navy leaders as well as junior officers and sailors at sea all need to talk to Navy scientists, the NRAC said.

Finally, NRAC said the NRL will have to find new ways to compete for outstanding scientific talent and to maintain a vibrant research culture and a diverse workforce.

NRAC “encourages the leadership of NRL to deliberately pursue a leadership role in enhancing diversity, equity, and inclusion of its technical workforce. Demographic data presented indicate that the distribution of scientists, engineers, and leaders is not diverse and in fact declines with seniority.”

* * *

The Navy had refused to divulge the NRAC report. A request under the Freedom of Information Act was denied on grounds that the report is “pre-decisional.”

“This report is marked ‘do not distribute’, is pre-decisional, and is thus exempt from disclosure,” the Navy said in its September 4, 2019 denial letter.

A copy of the report had to be obtained independently.

Leaks of pre-decisional DoD material are damaging to the nation even when they are unclassified, Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper told the House Armed Services Committee last week.

“The illegal leaks are terrible, they’re happening across the government, particularly at the Defense Department,” Secretary Esper said at the July 9 hearing (at 1:03:45). “Whether it’s pre-decisional unclassified items or even classified items it hurts our national security, it jeopardizes our troops and it is just damaging to our government and our relationships with our allies and partners.”

But it is hard to see how disclosure of this pre-decisional NRAC report could possibly fit Secretary Esper’s description. If anything, it is the Navy’s refusal to disclose the report that was more likely to cause damage by making it harder to advance solutions to the problems NRAC identified.

In this case, the Navy did more than simply suppress the NRAC message — it eliminated the messenger.

Shortly after the NRAC drafted its report on the Naval Research Laboratory, Under Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modly moved to terminate the 73 year old Naval Research Advisory Committee. (“Navy Torpedoes Scientific Advisory Group,” Secrecy News, April 5, 2019)

“You are hereby directed to execute all required actions to disestablish the Secretary of the Navy Advisory Panel and Naval Research Advisory Sub-Committee,” Modly wrote in a 21 February 2019 memo.

Today, as a result, the NRAC is no longer around to assess the results of its recommendations, nor will it be available to offer any further criticism in the future.

Update, 7/14/20: The Naval Research Laboratory replied to our request for comment as follows:

“The U.S. Naval Research Laboratory worked with the Naval Research Advisory Committee during their review of NRL in 2018, and has been working to implement many changes found during the NRAC’s review and since then, including a strategic plan. Further questions about the NRAC report should be sent to the Navy news desk.”

Leakers May Be Worse Than Spies, Gov’t Says

One might presume that foreign spies do more damage to national security than those who leak classified information to the press. But the opposite could be true, government attorneys told a court this week, because the leaked information is circulated more widely.

“While spies typically pass classified national defense information to a specific foreign government, leakers, through the internet, distribute such information without authorization to the entire world,” the Justice Department attorneys wrote. “Such broad distribution of unauthorized disclosures may actually amplify the potential damage to the national security in that every country gains access to the compromised intelligence,” they argued.

They wrote in opposition to a motion filed by accused leaker Daniel Everette Hale, who had moved for dismissal on First Amendment grounds of the Indictment against him.

The argument that leakers may be worse than spies is not new. It was previously advanced by the government in 2011 in the prosecution of former CIA officer Jeffrey Sterling, as reported at the time in Politico.

While Hale’s argument is obviously self-serving, the case for dismissal of the charges against him is nevertheless substantial, said the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press. The increased number of such prosecutions of sources who leak classified information to the press is adversely affecting the larger public interest, the organization argued in an amicus brief filed in support of the defendant.

“This case must be considered in the context of a dramatic uptick in the prosecution of journalistic sources since 2009, an increase in the severity of punishment, and a heightened danger of selective enforcement against lower-ranking disclosers,” their brief said.

“Not only are there far more cases today than 10 years ago, one can discern two trends in these cases: punishments that continue to increase in severity and the possibility of selective prosecutions against more vulnerable, lower-level disclosers.”

“Journalistic source prosecutions directly chill newsgathering by dissuading sources from coming forward with newsworthy information in the public interest.”

Collectively, these factors alter the context in which prior leak cases were adjudicated, the Reporters Committee argued. Current circumstances and the specifics of this case justify dismissal, the amicus brief said.

A Leaker’s Motives Are Irrelevant, Gov’t Says

Disclosing classified information without authorization is a crime even if the leaker had good intentions and was motivated by a larger public interest, the government said this week. Therefore, any mention of the purpose of the disclosure should be ruled out of bounds in trial, government attorneys argued.

The issue arose in pre-trial motions in the case of USA v. Daniel Everette Hale. Hale is a former NSA intelligence analyst and NGA contractor who is accused of having provided classified documents concerning US military drone programs to The Intercept.

“The defense likely will want to argue that, even if the defendant engaged in the conduct alleged, he had good reasons to leak the documents at issue and is being unfairly prosecuted under criminal statutes that carry significant penalties. Any such arguments, however, would be entirely improper,” the government said in a motion to exclude such material.

“Evidence of the defendant’s views of military and intelligence procedures would needlessly distract the jury from the question of whether he had illegally retained and transmitted classified documents, and instead convert the trial into an inquest of U.S. military and intelligence procedures.”

“The defendant may wish for his criminal trial to become a forum on something other than his guilt, but those debates cannot and do not inform the core questions in this case: whether the defendant illegally retained and transferred the documents he stole,” the September 16 government motion said.

The government said the defense should also be barred from arguing that a different perpetrator committed the charged crimes, from claiming that “everybody leaks classified information,” and from informing the jury that if convicted the defendant could go to prison.

“Any punishment or consequence the defendant might suffer is irrelevant to the factual issues and, therefore, inadmissible,” the government motion said.

Exclusion of a “good motive” or public interest argument is consistent with past practice in previous leak trials under the Espionage Act dating back to the case of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, as writer Tom Mueller recalled in his new cultural history of whistleblowing Crisis of Conscience: Whistleblowing in an Age of Fraud (p. 111).

In Ellsberg’s 1973 trial, “Prosecutors had also insisted, and [Judge William] Byrne had agreed, that the jury be instructed not to consider the larger questions raised by the defendant’s acts: the morality of the Vietnam War, the public’s right to know, the freedom of the press, or the Supreme Court’s recent First Amendment decision in favor of the [New York] Times,” Mueller wrote.

“Ellsberg still remembers his shock when the prosecution prevented him from explaining his motives for releasing the papers. When his lawyer asked him straightforwardly why he’d done it, a prosecutor objected that the question was ‘immaterial,’ and Judge Byrne sustained. ‘My lawyer was stunned,’ Ellsberg remembers. ‘He told Judge Byrne that he’d never heard of a case where a defendant wasn’t allowed to tell the jury why he’d done what he did. “Well, you’re hearing one now,” Byrne said’.”

“This restrictive interpretation of the Espionage Act presaged subsequent . . . prosecutions after 9/11, which forbade Chelsea Manning, Tom Drake and other national security whistleblowers from explaining why they blew the whistle,” Mueller wrote.

Defense challenges to secrecy policy and classification decisions should also be prohibited, the government argued in a separate motion in the Hale case.

“It is not proper for the Court or the defense to challenge a government agency’s classification determination. Such determinations are exclusively a function of the Executive Branch. It follows, therefore, that the defense cannot challenge the classification of the documents at issue in this case or make general allegations of misclassification of information within the U.S. government at large,” the government said.

* * *

For its part, the defense argued this week that the case against Hale should be dismissed because the Espionage Act as applied here infringes impermissibly on First Amendment freedoms.

“Now that the Act is used regularly against those who leak for no purpose other than informing their fellow citizens about their own government, its chilling effect is fatal to its continued viability. Moreover, its broad terms allow viewpoint-based prosecutions of the press and those whose actions are necessary for the press to freely operate.”

“Accordingly, the provisions charged here should be voided as facially overbroad, . . . and the Indictment should be dismissed,” the defense motion said (WaPo, AP).

The parties will respond to each other’s motions in weeks to come.

Administrative Subpoenas for Leak Investigations?

The possibility of using subpoenas to compel testimony from reporters or others in leak investigations outside of a criminal prosecution is being floated by the Intelligence Community Inspector General.

But such authority would have to be granted legislatively, and so far there is no sign that Congress is considering doing so.

The government’s interest in using administrative subpoenas was mentioned in the latest semi-annual report of the IC Inspector General:

“In March 2019, [IC] Inspector General Atkinson and the Inspector General of the Department of Justice met a second time with the President’s Intelligence Advisory Board to discuss, among other things, legislative approaches to reduce unauthorized disclosures, including testimonial subpoena authority for OIGs to compel non-agency individuals to provide testimony in administrative investigations.” (page 19)

* * *

Administrative investigations of leaks may occur before a criminal proceeding has been initiated, or after the Justice Department has declined criminal prosecution, as it often does. (In 2017-2018 there were over 200 referrals to the Justice Department of suspected criminal leaks, but only a handful of actual prosecutions ensued.)

As an alternative to criminal prosecution, administrative investigations can result in punishment of suspected leakers in the form of loss of security clearance, termination of employment, or monetary penalties.

In a criminal case, prosecutors can subpoena witnesses such as reporters and seek to compel their testimony. In the case of accused leaker Jeffrey Sterling, an appeals court concluded in a 2013 opinion that the government was within its rights to subpoena reporter James Risen. Although Risen did not ultimately testify in that case, the ruling authorizing a subpoena for a reporter in such circumstances remains in place after the US Supreme Court declined to review it.

But in internal administrative leak investigations, subpoena authority is not currently available (outside of espionage investigations involving a foreign power). It is this power which the IC Inspector General has now raised for discussion.

Leaks of Classified Info Surge Under Trump

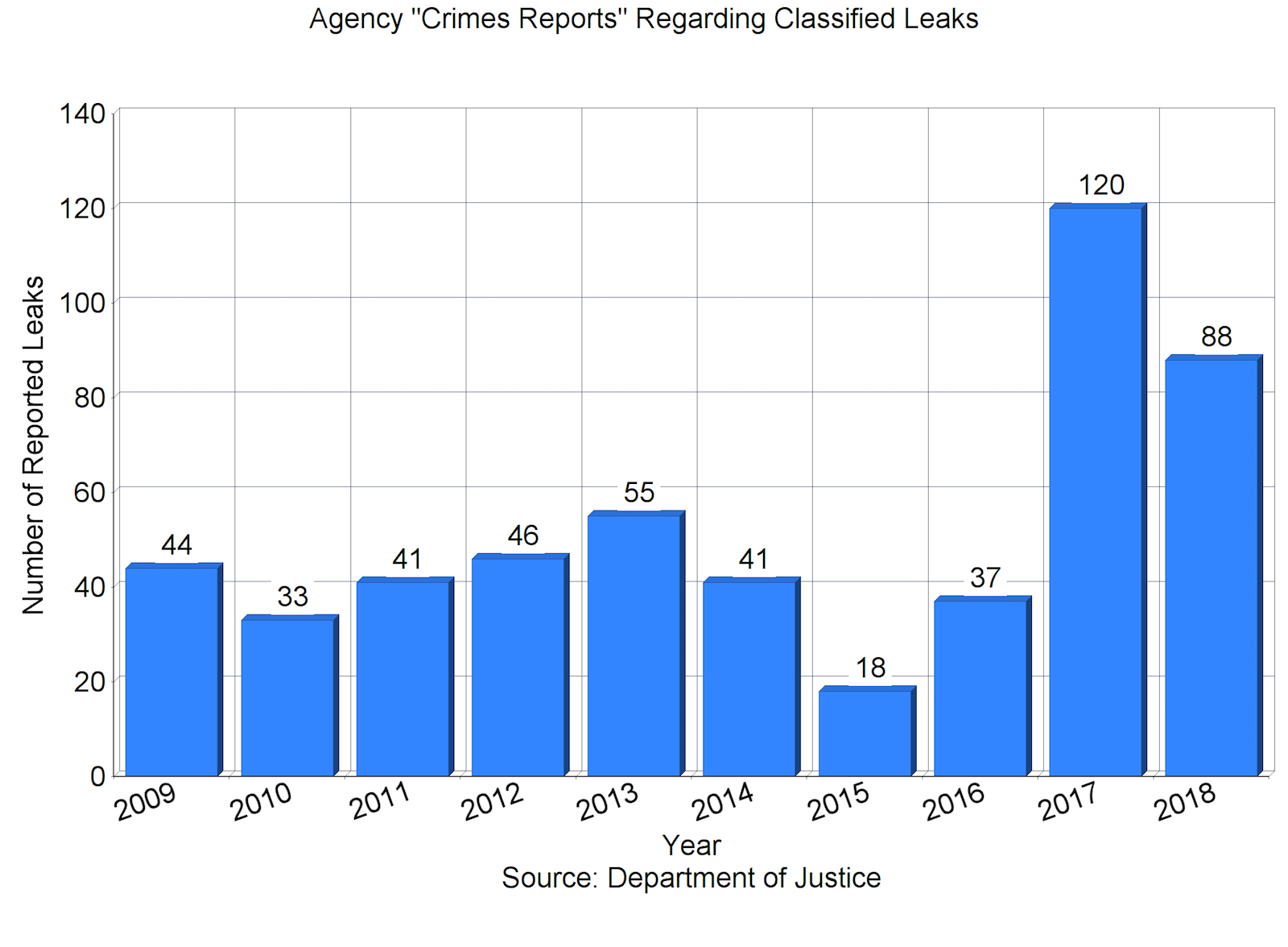

The number of leaks of classified information reported as potential crimes by federal agencies reached record high levels during the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data released by the Justice Department last week.

Agencies transmitted 120 leak referrals to the Justice Department in 2017, and 88 leak referrals in 2018, for an average of 104 per year. By comparison, the average number of leak referrals during the Obama Administration (2009–2016) was 39 per year.

There are a “staggering number of leaks,” then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at an August 4, 2017 briefing about efforts to prevent the unauthorized disclosures.

“Referrals for investigations of classified leaks to the Department of Justice from our intelligence agencies have exploded,” AG Sessions said at that time. He outlined several steps that the Administration would take to combat leaks of classified information, including tripling the number of active leak investigations by the FBI.

“We had about nine open investigations of classified leaks in the last 3 years,” he told the House Judiciary Committee at a November 2017 hearing. “We have 27 investigations open today.” (Some of those investigations pertain to leaks that occurred before President Trump took office.)

“We intend to get to the bottom of these leaks. I think it reached—has reached epidemic proportions. It cannot be allowed to continue,” Sessions said then, “and we will do our best effort to ensure that it does not continue.”

But it has continued. Despite preventive efforts, the 2018 total of 88 leak referrals was still higher than any reported pre-Trump figure. (The previous high in recent decades had been 55 referrals in 2013 and in 2007. The lowest was 18 in 2015.)

*

Not all leaks of classified information generate such criminal referrals. Disclosures that are inadvertent, insignificant, or officially authorized would not be reported to the Justice Department as suspected crimes.

Meanwhile, only a fraction of the classified leaks that are reported by agencies ever result in an investigation, and only a portion of those lead to identification of a suspect and even fewer to a prosecution.

“While DOJ and the FBI receive numerous media leak referrals each year, the FBI opens only a limited number of investigations based on these referrals,” the FBI told Congress in 2009. “In most cases, the information included in the referral is not adequate to initiate an investigation.”

The newly released aggregate data on classified leak referrals serve as a reminder that leaks of classified information are a “normal,” predictable occurrence. There is not a single year in the past decade and a half for which data are available when there were no such criminal referrals.

But the data as released leave several questions unanswered. They do not reveal how many of the referrals actually triggered an FBI investigation. They do not indicate whether the leaks are evenly distributed across the national security bureaucracy or concentrated in one or more “problem” agencies (or congressional committees). And they do not distinguish between leaks that simply “hurt our country,” as the Attorney General put it, and those that are complicated by a significant public interest in the information that was disclosed.

A Leak Prosecution That Didn’t Happen

Government prosecutors have been aggressively pursuing suspected leakers of classified information:

Reality Winner, accused of disclosing a document “information relating to the national defense” to a news outlet, changed her plea this week from “not guilty” to “guilty.”

Former FBI agent Terry J. Albury likewise pleaded guilty last April to unauthorized retention and disclosure of national defense information.

Former Senate Intelligence Committee security officer James A. Wolfe was indicted this month for allegedly lying to the FBI in the course of a leak investigation.

And also this month, Joshua Adam Schulte was indicted for allegedly disclosing national defense information to a certain “organization that purports to publicly disseminate classified, sensitive, and confidential information.”

But not every leak results in an official leak investigation. And not every leak investigation produces a suspect. Nor is every leak suspect prosecuted.

In its latest semi-annual report, the Office of the Intelligence Community Inspector General describes one recent case of an acknowledged leaker of classified information who was allowed to resign without prosecution.

The IC Inspector General “substantiated allegations that an ODNI cadre officer disclosed classified information without authorization, transmitted classified information via unauthorized means, and disclosed classified information to persons not authorized to receive it.”

“During a voluntary interview, the ODNI cadre officer admitted to transmitting classified information over unclassified (internet) email to recipients not authorized to receive classified national security information.”

But the matter was resolved outside of the criminal justice system.

“The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Virginia declined prosecution. The officer, who was retirement eligible, retired before termination,” the IC IG report said.

No other details about the episode were disclosed. But the case illustrates that a variety of responses to leak incidents are available to the government short of criminal prosecution.

A House bill to authorize intelligence spending for FY 18 and 19 (HR 6237), introduced yesterday, would require expanded reporting to Congress on unauthorized disclosures of classified information.

USA v. Terry Albury: A Guilty Plea

The second prosecution of an accused leaker in the Trump Administration (after Reality Winner) will yield the first conviction. Former FBI special agent Terry J. Albury pleaded guilty this week to unlawful disclosure and retention of national defense information, each of which is a felony under the Espionage Act statutes.

The plea agreement, signed by the defendant, outlines the facts of the case and sets the stage for sentencing.

“Terry Albury betrayed the trust bestowed upon him by the United States,” said U.S. Attorney Tracy Doherty-McCormick in an April 17 news release. “Today’s guilty plea should serve as a reminder to those who are entrusted with classified information that the Justice Department will hold them accountable.”

But Albury’s attorneys said that his actions were those of a whistleblower. “His conduct in this case was an act of conscience. It was driven by his belief that there was no viable alternative to remedy the abuses he sought to address. He recognizes that what he did was unlawful and accepts full responsibility for his conduct,” they said in a statement quoted in Politico.

Under the terms of the plea agreement, “The defendant waives all rights to obtain, directly or through others, information about the investigation and prosecution of this case under the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act of 1974.”

USA v. Terry Albury: The Second Trump-Era Leak Case

FBI agent Terry J. Albury was charged last week with two violations of the Espionage Act statutes for disclosing classified information to a reporter for the Intercept. The charges, including unauthorized disclosure and unauthorized retention of national defense information, were formally presented by the Justice Department in a March 27 “Information.”

See also “Minneapolis FBI agent charged with leaking classified information to reporter” by Mukhtar M. Ibrahim, MPR News, March 28.

The Albury case is the second criminal prosecution in the Trump Administration arising from a leak of classified information to the news media. The first was the pending case of Reality Winner.

DNI Updates Policy on Classified Leaks

Director of National Intelligence Daniel R. Coats last month issued a newly revised directive that details intelligence community procedures for dealing with leaks of classified information. See Unauthorized Disclosures of Classified National Security Information, Intelligence Community Directive 701, December 22, 2017.

The directive formalizes several notable developments in intelligence policy regarding leaks:

* It presents an expansive definition of an unauthorized disclosure that includes not simply disclosure but also the “confirmation” or “acknowledgement” of classified information to an unauthorized person.

* It mandates the use of “audits and systems monitoring” in order “to detect and attribute attempts to bypass or defeat security safeguards.”

* It specifies that polygraph examinations used by intelligence agencies shall “address the issue of unauthorized disclosures of classified information” as part of the security vetting process.

* It notes that the DNI may prohibit the IC Inspector General from investigating a leak, pursuant to 50 USC 3033(f), “if the Director determines that such prohibition is necessary to protect vital national security interests of the United States.” The DNI is obliged to notify the congressional intelligence committees if he ever exercises this authority.

The new directive defines a hierarchy of unauthorized disclosures based on their severity and the feasibility of investigating and prosecuting them. “This process is designed to identify which incidents can be closed without further review, which call for an internal investigation, and which should be referred [to the Department of Justice] with a request for a criminal investigation.”

The directive updates and expands the provisions of a prior version that was issued in 2007 by then-DNI Mike McConnell.

Army Operations: The New Operational Environment

Other nations, including current and potential adversaries, possess military capabilities that now match or exceed those of the United States, according to a new US Army doctrinal publication.

“Today’s operational environment presents threats to the Army and joint force that are significantly more dangerous in terms of capability and magnitude than those we faced in Iraq and Afghanistan. Major regional powers like Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea are actively seeking to gain strategic positional advantage. These nations, and other adversaries, are fielding capabilities to deny long-held U.S. freedom of action in the air, land, maritime, space, and cyberspace domains and reduce U.S. influence in critical areas of the world.”

“In some contexts they already have overmatch or parity, a challenge the joint force has not faced in twenty-five years.”

That assessment appears in the Foreword to the newly updated US Army Field Manual 3.0 on Operations that was officially released today.

The Field Manual describes the conduct of operations in the new environment, with notably new material on the cyber and space domains.

“Threat operations [by adversaries] in cyberspace are often less encumbered by treaty, law, and policy restrictions than those imposed on U.S. forces, which may allow adversaries or enemies an initial advantage,” the manual states.

The unclassified field manual was released along with two supporting volumes:

ADP 3-0. Operations, Army Doctrine Publication, October 2017, and

ADRP 3-0. Operations, Army Doctrine Reference Publication, October 2017

Last week, Secretary of Defense James Mattis issued a memorandum to all military personnel and DoD employees warning against leaks of classified or otherwise restricted defense information.

“It is a violation of our oath to divulge, in any fashion, non-public DoD information, classified or unclassified, to anyone without the required security clearance as well as a specific need to know in performance of their duties,” he wrote. A copy of the memo was obtained by Military Times. (A security clearance is not required for unclassified information.)

Yet also last week, Secretary Mattis himself disclosed new information that about US rules of engagement that is normally not published, the New York Times reported. A Pentagon spokesman denied that the disclosure would place US forces at risk, or help the enemy. See “Mattis Discloses Part of Afghanistan Battle Plan, but It Hasn’t Yet Been Carried Out” by Thomas Gibbons-Neff, October 6.

Legality of Presidential Disclosures, Continued

“There is no basis” for suggesting that President Trump’s disclosure of classified intelligence to Russian officials was illegal, wrote Morton Halperin this week.

To the contrary, “senior U.S. government officials in conversations with foreign officials decide on a daily basis to provide them with information that is properly classified and that will remain classified,” wrote Halperin, who is himself a former senior official.

“We should not let our desire to confront President Trump lead us to espouse positions that violate his rights and that would constrain future presidents in inappropriate ways.” See “Trump’s Disclosure Did Not Break the Law” by Morton H. Halperin, Just Security, May 23, 2017.

But constraints on presidential disclosure were on the minds of Rep. Stephanie Murphy (D-FL) and 17 House colleagues. They introduced legislation on May 24 “that would require the President to notify the intelligence committees when a U.S. official, including the President, intentionally or inadvertently discloses top-secret information to a nation that sponsors terrorism or, like Russia, is subject to U.S. sanctions.”

Yesterday, Rep. Dutch Ruppersberger (D-MD) introduced a bill “to ensure that a mitigation process and protocols are in place in the case of a disclosure of classified information by the President.”

Rep. Mike Thompson (D-CA) and five colleagues introduced a resolution “disapproving of the irresponsible actions and negligence of President Trump which may have caused grave harm to United States national security.”

For related background, see The Protection of Classified Information: The Legal Framework, Congressional Research Service, updated May 18, 2017, and Criminal Prohibitions on Leaks and Other Disclosures of Classified Defense Information, Congressional Research Service, updated March 7, 2017.

Legality of the Trump Disclosures, Revisited

When President Trump disclosed classified intelligence information to Russian officials last week, did he commit a crime?

Considering that the President is the author of the national security classification system, and that he is empowered to determine who gets access to classified information, it seems obvious that the answer is No. His action might have been reckless, I opined previously, but it was not a crime.

Yet there is more to it than that.

The Congressional Research Service considered the question and concluded as follows in a report issued yesterday:

“It appears more likely than not that the President is presumed to have the authority to disclose classified information to foreign agents in keeping with his power and responsibility to advance U.S. national security interests.” See Presidential Authority to Permit Access to National Security Information, CRS Legal Sidebar, May 17, 2017.

This tentative, rather strained formulation by CRS legislative attorneys indicates that the question is not entirely settled, and that the answer is not necessarily obvious or categorical.

And the phrase “in keeping with his power and responsibility to advance U.S. national security interests” adds an important qualification. If the president were acting on some other agenda than the U.S. national interest, then the legitimacy of his disclosure could evaporate. If the president were on Putin’s payroll, as the House majority leader lamely joked last year, and had engaged in espionage, he would not be beyond the reach of the law.

Outlandish hypotheticals aside, it still seems fairly clear that the Trump disclosures last week are not a matter for the criminal justice system, though they may reverberate through public opinion and congressional deliberations in a consequential way.

But several legal experts this week insisted that it’s more complicated, and that it remains conceivable that Trump broke the law. See:

“Don’t Be So Quick to Call Those Disclosures ‘Legal'” by Elizabeth Goitein, Just Security, May 17, 2017

“Why Trump’s Disclosure to Russia (and Urging Comey to Drop the Flynn Investigation, and Various Other Actions) Could Be Unlawful” by Marty Lederman and David Pozen, Just Security, May 17, 2017

“Trump’s disclosures to the Russians might actually have been illegal” by Steve Vladeck, Washington Post, May 16, 2017

Update, 05/23/17: But see also Trump’s Disclosure Did Not Break the Law by Morton Halperin, Just Security, May 23, 2017.