Over the Line: The Implications of China’s ADIZ Intrusions in Northeast Asia

When China established its first ADIZ in the East China Sea on November 23, 2013, the move was widely seen as a practice run before establishing one in the South China Sea to strengthen its controversial territorial claims. However, examining China’s use of its ADIZ the way its treatment of those of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has evolved over the past seven years reveals that China’s East China Sea ADIZ has effectively given China new latitude to extend its influence in Northeast Asia.

Since 2013, China has committed more than 4,400 intrusions into the ADIZs of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Often, Chinese forces violate multiple countries’ ADIZs on their flights, flying routes that consecutively transgress South Korea’s and Japan’s ADIZs or Taiwan’s and Japan’s. While each country has so far managed the issue in its own way by scrambling jets, discussing the issue with China in bilateral meetings, and publicizing some information about the intrusions, the issue has become a regional one impacting all three countries.

This report uses data gathered from multilingual sources to explore China’s motivations behind these intrusions as well as the implications for Japanese, South Korean, Taiwanese, and U.S. forces operating in Northeast Asia.

The History of U.S. Decision-making on Nuclear Weapons in Japan

Earlier this month, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said he favored placing conventional intermediate-range missiles in Asia following the demise of the INF treaty. While Secretary Esper did not indicate where the missiles might be deployed, many security experts believe Japan to be the most likely candidate. The tight U.S.-Japan security alliance built from the American Occupation has historically set up Japan as an ideal staging ground for U.S. weapons systems. Though Secretary Esper and most proposals for intermediate-range missiles in Asia refer to conventional weapons, because of their strategic importance, many Japanese are likely to read these proposals as part of a long and politically fractious history of US weapons deployments to Japanese territory that included nuclear weapons.

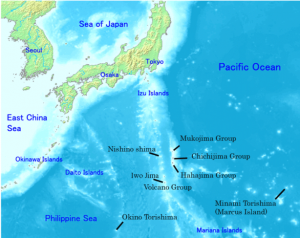

Japan’s strategic location in the Pacific coupled with the heavy American influence on the emerging democracy made it an attractive option to host U.S. nuclear weapons during the Cold War. U.S. control of Japan’s southern island chain presented a strategic opportunity to forward deploy tactical nuclear weapons into an increasingly volatile Pacific region where war planners anticipated their increased military utility as they planned force postures to respond to the aftermath of the Korean War and the Chinese Civil War.

In 1959, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi first declared that Japan would neither develop nor permit nuclear weapons on its territory. This declaration formed the cornerstone of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s 1967 establishment of Japan’s “three non-nuclear principles” which promise not to process, produce, or permit the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan. The Diet formally adopted these principles through a resolution in 1971, though they are not legally binding. Prime Minister Sato, worried that the three non-nuclear principles were too binding on Japan’s defense posture, supplemented the policy in February 1968 with his “four pillars nuclear policy.” The four pillars were to promote peaceful use of nuclear power, to work toward global nuclear disarmament, to rely on the extended U.S. nuclear deterrent, and to support the three non-nuclear principles.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, U.S. officials often complained that Japan’s “nuclear allergy” imposed constraints on U.S. nuclear force posture. But despite the Japanese government’s public anti-nuclear stance, the nuances of the bilateral security relationship and treaty language emboldened the U.S. to deploy nuclear weapons to Japan in the mid-1950s. The occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1951 but the Treaty of San Francisco allowed the U.S. to maintain its control over Japan’s southern island chains, which include the islands of Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and Chichi Jima. War planners worried that compromised communication systems in a time of crisis would make emergency deployments and transfers of nuclear weapons difficult or impossible, so they sought to establish a forward deployed posture in the Pacific.

The bulk of the nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa at the Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot adjacent from Camp Schwab and the Kadena Ammunition Storage Area at Kadena Air Base, where SAC’s strategic bombers were based. Between 1954 and 1972, the bases on Okinawa hosted 19 different types of nuclear weapons. At the height of the Vietnam War, around 1,200 nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa alone. A document declassified in 2017 shows that in 1969 Japan officially consented to the U.S. bringing nuclear weapons to Okinawa.

Every American president from 1952 onward remained publicly committed to the reversion of Okinawa, but was privately reluctant to initiate the hand-over. During the 1950s to mid-1960s, the Japanese were largely willing to accept reversion as a distant goal, in part because the U.S.-backed Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that held power in the post-Occupation era was hesitant to challenge the U.S. on the issue. The Japanese government also recognized the security value of U.S. forces stationed in Okinawa, given Japan’s restraining pacifist constitution. However, in the late-1960s, pressure began to build from the Okinawans and the mainland Japanese establishment to return the island to Japan.

Prime Minister Sato first raised the issue with the U.S. in 1967 during talks with President Johnson. President Johnson responded that because of the 1968 election and the war in Vietnam, the U.S. would be unable to address reversion of Okinawa until 1969 at the earliest. In March of 1969, Henry Kissinger sent President Nixon a memo outlining the Japanese demands for reversion as well as the relevant military and political considerations. While the memo acknowledged that public demand within Japan for reversion was growing politically untenable for Prime Minister Sato, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff were primarily concerned about the effect of reversion on nuclear storage and military activities such as B-52 operations against Vietnam. On nuclear storage, Kissinger wrote, “The loss of Okinawan nuclear storage would degrade nuclear capabilities in the Pacific and reduce our flexibility.”

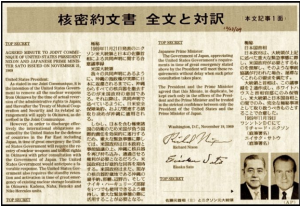

Top secret agreement allowing the U.S. to maintain emergency reactivation of nuclear weapons storage on U.S. bases in Okinawa. (Image courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists.)

While the Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted the Nixon Administration to push for continued nuclear storage post-reversion, Kissinger wrote that it was unlikely that the Japanese Diet would support it in face of growing public dissatisfaction, even if Prime Minister Sato agreed. Kissinger added that “…in the slim possibility that Japanese agreement to nuclear storage is obtained, we must recognize that the Japanese proponents of this position view this as the opening wedge for an independent Japanese nuclear force.” Kissinger recommended that the U.S. return Okinawa to Japanese control and give up nuclear storage on the island in order to maintain basing rights, emergency nuclear storage rights, and full nuclear transit rights.

Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon agreed to the reversion of Okinawa in 1969. The agreement contained a secret clause permitting the U.S. to reintroduce nuclear weapons to its Okinawa bases in the case of an emergency. Okinawa was officially returned to Japan in 1972 and shortly after all U.S. nuclear warheads were withdrawn.

In 2016, the U.S. government officially declassified the fact that nuclear weapons were deployed to Okinawa before 1972. It also declassified “the fact that prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japan that the U.S. Government conducted internal discussion, and discussions with Japanese government officials regarding the possible re-introduction of nuclear weapons onto Okinawa in the event of an emergency or crisis situation.”

While military planners believed the forward deployed nuclear weapons on Okinawa were useful in launching potential attacks against China, Russia, or Vietnam, they feared that in the event of nuclear war with either China or Russia, the U.S. bases on Okinawa would be attacked and destroyed early. In order to maintain a viable second salvo in the Pacific, nuclear weapons were also stored on the U.S.-controlled islands of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima. Iwo Jima became a fallback support station for the Far East Air Force, maintaining an unknown arsenal of atomic bombs that bombers could pick up for a second strike after dropping their first load on China or Russia. Chichi Jima was outfitted with W5 nuclear warheads for Regulus missiles to serve as a reload point for Regulus submarines if U.S. bases in Japan, Pearl Harbor, Guam, and Adak were destroyed in nuclear war.

The U.S. maintained nuclear weapons as well as other military support structures on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima into the mid-1960s. The Japanese had been pushing for return of Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Okinawa since the mid-1950s and by 1964, U.S. diplomats in Tokyo also began pressuring Washington to return the islands to Japan, believing it vital to maintaining the cooperative and positive relationship the two countries shared. President Johnson, realizing that returning Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima would be a necessary concession in order to delay the return of the more strategically valuable island of Okinawa, reverted control of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima to Japan in 1968. All nuclear weapons were removed from the islands by the time of their reversion, but the agreement President Johnson and Foreign Minister Takeo Miki signed would allow the U.S. to redeploy nuclear weapons to the islands in an emergency, upon consultation with the Japanese government. The U.S. government has not confirmed the deployment of nuclear weapons to Iwo Jima or Chichi Jima.

In addition to the nuclear weapons stored on Japan’s southern island chains, the U.S. allegedly stored nuclear weapons without the fissile cores on the Japanese mainland at Misawa and Itazuki airbases until 1965, avoiding by mere semantic technicality violation of Japan’s sovereignty and the integrity of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles. Nuclear armed naval ships were also allegedly allowed to transit Japanese waters and dock at mainland ports with tacit Japanese approval into the 1980s under an oral agreement the two countries made when Japan and the U.S. renegotiated the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960.

While the U.S. government has never confirmed that U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons visited Japanese ports, there are two instances that support this claim. In 1974, retired Rear Admiral Gene La Rocque who formally commanded a flagship of the Seventh Fleet, testified before Congress that “any ship capable of carrying nuclear weapons carries nuclear weapons. They do not unload them when they go into foreign ports such as Japan or other countries.”

In 1981, Edwin O. Reischauer, former U.S. Ambassador to Tokyo during the 1960s, acknowledged in a newspaper interview that Japan was permitting U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons to transit Japanese ports under the aforementioned oral agreement. According to Reischauer, American warships could bring nuclear weapons into Japanese waters and ports during routine visits but were not allowed to be unloaded or stored in Japan. The agreement allowed the same freedom to U.S. military planes carrying nuclear weapons.

Both disclosures incited protests from the Japanese public, which has adamantly maintained its anti-nuclear posture since U.S. atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. However, the historical record shows that the Japanese executive branch, dominated for decades by conservative LDP politicians, has at times acquiesced to asserted U.S. military necessities when it comes to nuclear weapons.

The coalitional Diet however has been historically reluctant to publicly support such domestically unpopular measures as allowing U.S. nuclear weapons into Japanese territory or developing an independent nuclear force. This reluctance extends to the possible deployment of conventional intermediate-range missiles being discussed among U.S. defense specialists today.

Policymakers and analysts should be aware of the complex history of US weapons deployments to Japan when discussing future deployments. It should be expected that proposed deployments will face similarly strong political reactions from activists, civil society groups, and communities who remember this history first hand.

“Fact of” Nuclear Weapons on Okinawa Declassified

Updated below

The Department of Defense revealed this week that “The fact that U.S. nuclear weapons were deployed on Okinawa prior to Okinawa’s reversion to Japan on May 15, 1972” has been declassified.

While this is indeed news concerning classification policy, it does not represent new information about Okinawa.

According to an existing Wikipedia entry, “Between 1954 and 1972, 19 different types of nuclear weapons were deployed in Okinawa, but with fewer than around 1,000 warheads at any one time” (citing research by Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin and William Burr that was published in 1999 in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists). As often seems to be the case, declassification here followed disclosure, not the other way around.

If there is any revelation in the new DoD announcement, it is that this half-century-old historical information was still considered classified until now. As such, it has been an ongoing obstacle to the public release of records concerning the history of Okinawa and US-Japan relations.

Because this information had been classified as “Formerly Restricted Data” under the Atomic Energy Act rather than by executive order, its declassification required the concurrence of the Department of Defense, the Department of Energy, and (in this case) the Department of State. Any one of those agencies had the power to veto the decision to declassify, or to stymie it by simply refusing to participate.

Instead, the information was declassified as a result of a new procedure adopted by the Obama Administration to coordinate the review of nuclear weapons-related historical material that is no longer sensitive but that has remained classified under the Atomic Energy Act by default. The new procedure had been recommended by a 2012 report from the Public Interest Declassification Board, and was adopted by the White House-led Classification Reform Committee.

Also newly declassified and affirmed this week was “The fact that prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japan that the U.S. Government conducted internal discussion, and discussions with Japanese government officials regarding the possible re-introduction of nuclear weapons onto Okinawa in the event of an emergency or crisis situation.”

Such individual declassification actions could go on indefinitely, since there are innumerable other “facts” whose continued classification cannot reasonably be justified by current circumstances. A more systemic effort to recalibrate national security classification policy government-wide is to be performed over the coming year.

Update: The National Security Archive posted the first officially declassified document on nuclear weapons in Okinawa, which was released in response to its request. See Nuclear Weapons on Okinawa Declassified, February 19, 2016.

A Looming Crisis of Confidence in Japan’s Nuclear Intentions

Nearly two years into Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second stint at governing Japan, his tenure has been characterized by three primary themes. The first two themes include his major legislative priorities: enabling Japan’s economic revival and bringing Japan closer to the status of a “normal” country that takes on a greater share of its own security needs. Both of these priorities are largely celebrated in the United States, which longs to see Japan become a more able and active partner in the region. A third theme has not been well received in Washington: the prime minister’s apparent efforts to whitewash Japan’s wartime past. Through personal expressions of admiration for convicted war-criminals, an official reinvestigation of past apologies for war-time atrocities, and appointments of hardline nationalists to prominent posts (such as the NHK board of governors), the prime minister’s actions have raised the spectre among wary neighbors of a Japanese return to militarism and begun raising eyebrows even among friends in Washington.

It is against this backdrop that Japan is now attempting to reinstate its nuclear energy program. Japan, which, not long ago, had planned to generate half of its electricity from nuclear power by 2030, has watched its nuclear reactors sit largely idle since the Fukushima disaster in 2011. Abe’s government views nuclear restarts as a critical pillar of his first legislative priority—Japan’s economic recovery. However, observers both outside and inside Japan note that, in addition to providing Japan the baseload electricity that its economy craves, the country’s sophisticated nuclear energy program effectively serves a dual purpose, providing Japan a latent nuclear weapons capability as well.

Citing Abe’s particular treatment of historical issues, some have begun to question whether reinstatement of Japan’s nuclear program is really more about the prime minister’s security goals than his economic agenda. China, for one, has hinted at allegations of a Japanese nuclear weapons program—after a recent incident in which Japan negotiated to repatriate an aging store of highly enriched uranium (HEU) to the United States, Chinese media propagated a narrative that twisted the event into evidence of Japan’s militaristic intentions.1 Koreans have begun expressing similar concerns.2

In fact, Japan’s current movement towards a more normal military posture is not entirely unrelated to the push to restart the country’s nuclear energy program—it was the Fukushima nuclear disaster that both idled Japan’s nuclear fleet and helped enable the return of the more hawkish LDP government. But the relationship likely ends there. As a legacy of World War II, Japanese society’s discomfort with the idea of a “normal” Japan has restricted Abe’s normalization efforts to steps that are only modest by any comparable measure.3 Events that have conspired to suggest the possibility of Japanese nuclear weapons are reflective of awkward timing and, perhaps, less than acute politics, but not likely of some new militant spirit in Japanese society. Unfortunately, as Japan pushes to restart its nuclear energy program in the months and years ahead, circumstances are aligning that will amplify—not mitigate—alarm over Japan’s nuclear intentions.

Japan’s Plutonium Economy

For a tangle of social and legal reasons, the restart of Japanese reactors is tied together with operation of Japan’s nuclear fuel reprocessing plant at Rokkasho Village in Aomori Prefecture. Under agreements with reactor host communities, utilities cannot operate reactors unless there is somewhere for nuclear fuel to go once it has been used. Because Japan lacks a geological repository and nearly all plant sites lack dry cask storage facilities,4 Rokkasho is currently the only viable destination for spent fuel from Japan’s reactors. Unless this situation changes, Japan is effectively unable to operate reactors without Rokkasho.

Rokkasho itself is, in turn, effectively dependent on Japan’s operating reactors. According to a sort of public-private arrangement that has been in place since before Fukushima, Japanese utilities send spent nuclear fuel to Rokkasho, where it is separated into waste and fissionable MOX (mixed uranium and plutonium oxides) powder. MOX is processed into fresh reactor fuel and sent back to Japan’s reactors. High-level waste is ultimately sent to a geological repository that is to be built in a different prefecture (one of Aomori Prefecture’s conditions for originally agreeing to host the reprocessing plant). Of Japan’s reactors, 16 to 18 of the 54 that were operating prior to the Fukushima accident would, after receiving local government consent, consume MOX in an effort to maximize use of Japan’s limited energy resources. That was the plan—prior to the Fukushima disaster, anyway.

As a legacy of the Fukushima disaster, Japan’s nuclear reactors currently sit idle. The six at Fukushima Daiichi will never operate again, nor will a number of others that are older, particularly vulnerable to earthquakes and tsunamis, or for other reasons not worth the trouble and expense of restarting. While impossible to predict for certain, a consensus seems to be emerging among experts and industry watchers that post-Fukushima, somewhere in the order of half of Japan’s original 54 reactors will return to service under Japan’s new regulatory regime. Currently, two reactors (Sendai 1 and 2 in southwestern Japan) have cleared safety reviews from Japan’s new regulator, the Japan Nuclear Regulatory Authority (JNRA), and now appear headed towards restart this winter. Eighteen more reactors await review from the JNRA. Of those 20 reactors, only five5 have received consent to use MOX, but that was prior to Fukushima. All 20 reactor restarts depend on the promise of a functioning Rokkasho. But if Rokkasho were to restart on a similar timeframe as the reactors, one thing is certain—there will be far fewer than the originally envisioned 16 to 18 reactors available to consume the MOX when the plant starts up.6

Reactor Restart X-Factors

As with Rokkasho, the question of when the JNRA will conclude its reviews of the next eighteen reactors remains quite murky. However, it stands to reason that ultimately most, if not all, of the reactors that have applied for restart will ultimately pass safety inspections. Japan’s electric power companies are unlikely to have invested the time and resources in plant upgrades and regulatory application had they less than a high degree of confidence that they would qualify under Japan’s new regime. Likewise, there is little question that Japan’s LDP government (assuming an LDP government at the time of restart) would stand in the way of restarts. But the JNRA and national government are only two of the three main factors in restarting Japan’s reactors—leaders of the towns and prefectures that host nuclear power plants have a de facto say in the matter as well.

The conventional wisdom is that local leaders have strong financial incentives to restart the nuclear power plants that they host: government and industry have historically lavished incentives on host communities and prefectures in order to overcome any inclination toward local resistance. In one sense, local governments have over time become dependent on plants and can ill afford to forego not only the government and utility incentives, but also the base of jobs and tax revenues they represent. On the other hand, communities need now only look to the example of the towns that have been rendered uninhabitable by the Fukushima disaster to see a terrifyingly clear picture of their tradeoff.

In some cases, apparently including the Sendai reactors, it is unlikely that local government would stand in the way of restarts. Earthquakes are less common in Kyushu,7 the geography on the west coast is less prone to large tsunamis, and local residents may take comfort in the fact that Sendai reactors are pressurized water reactors—not the boiling water rector type used at Fukushima Daiichi. But in other cases, local approvals may not be as certain. Take for example TEPCO’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant in Nagano prefecture, where Governor Izumida has very publicly challenged TEPCO. He has insisted that, irrespective of the findings of the JNRA, with the Fukushima Daiichi reactor cores still too highly radioactive to investigate and verify the true nature of the accident, he will be unwilling to allow the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa reactors to restart.

In addition to the local government factor, an X-factor may be emerging—preemptive lawsuits against reactor restarts. Earlier this year, in Fukui prefecture where political leadership otherwise favors nuclear power, a citizens group brought a lawsuit alleging an inadequate basis for confidence in the restart of the Oi plant.8 More recently, a second lawsuit has been brought by the city of Hakodate (Hokkaido prefecture) against the yet-to-be completed Ohma plant in nearby Aomori prefecture.9 In the case of Oi, a local judge sided with the plaintiffs, but the decision has been appealed by Kansai Electric Power Company, and the case is all but certain to drag out until long past the serviceable lifetime of the Oi reactors. The Hakodate case is ongoing.

It is possible that Governor Izumida is an outlier and that the Fukui and Hakodate challenges will prove to be ineffective and isolated. However, it is equally possible that there are more Governor Izumidas and lawsuits yet to come. Furthermore, what is undeniable is that these cases have set a precedent and raised public pressure on local officials to seriously consider opposing restart of local reactors even if they do pass JNRA safety inspections. In any case, it is premature to presume that once the JNRA has rendered a safety verdict, reactor restart is imminent.

The MOX Question

Within the concurrent push to open Rokkasho and restart reactors, the availability of MOX-burning reactors seems to be assumed. But, notwithstanding all of the other hurdles facing nuclear reactor restarts in Japan, MOX fuel itself has been a subject of controversy and public discomfort since even before the Fukushima disaster. As utilities received approvals to burn MOX fuel and subsequently began receiving shipments of MOX from Europe (where it had been processed on behalf of Japan’s utilities), they were met with consistent and passionate public protests. These protests were typically confined to a cohort of smaller national-level interest groups that argue that using MOX elevates risk in transportation and regular reactor operation.10 On a national scale, prior to Fukushima the fuel cycle has been a relatively fringe issue—MOX had been a largely unfamiliar acronym to the public. Post-Fukushima, as utilities push for restarts amidst an atmosphere of heightened public scrutiny, there will be no free pass for MOX. For nuclear energy opponents, the prospect of MOX usage would provide one more narrative with which to hammer against proposed reactor restarts.

At the macro level, utilities share in the incentive to burn MOX fuel as they depend on Rokkasho, and Rokkasho is hard to rationalize in the absence of a functioning MOX program. However, in a much more tangible and immediate sense, utilities desperately need their reactors up and running again. Most of Japan’s utilities have posted consistent losses since their reactors were relegated to nonperforming assets on their balance sheets and they were forced to substitute expensive fossil fuels for relatively cheaper nuclear power. For Japan’s utilities, restarting nuclear reactors could be a life or death proposition. That being the case, can it be taken for granted that utilities will risk complicating their restart efforts by forging ahead with plans to burn MOX? Will the government create explicit incentive for utilities to do so? Given enhanced public scrutiny, it cannot be assumed that the pre-Fukushima local approvals for MOX usage will be honored anyway.

The Japanese government’s 2014 energy policy (despite reaffirming Japan’s commitment to its beleaguered ‘no surplus plutonium’ policy), gives blessing to proceeding with Rokkasho (recognizing that, among other things, if it didn’t, Aomori threatens to send the spent nuclear fuel right back to the plants of origin). But even assuming that the five MOX reactors under regulatory review do receive restart approval and recommence MOX burning, the original goal of 16 to 18 Japanese reactors burning MOX fuel seems far off.11 There has been some suggestion that Rokkasho could restart slowly, at a throughput commensurate with the ability to consume MOX. However, as Meiji University Professor Tadahiro Katsuta points out, reducing throughput of Rokkasho effectively raises the per-unit cost of MOX, necessitating a reexamination of the cost basis on which the MOX program was justified to Japanese ratepayers.12

Rokkasho Controversy

Even outside of the MOX capacity question, Rokkasho is not without controversy. Officially, Rokkasho is justified as an investment in energy security for Japan. However, from the standpoint of global nonproliferation concerns, Japan sets an uncomfortable precedent with Rokkasho. While otherwise a leading global champion for peace and nuclear disarmament, Japan is the only non-nuclear weapons country to possess a commercial nuclear fuel recycling program. Whereas global nonproliferation efforts prioritize limiting the spread of reprocessing capabilities, Rokkasho has enabled Iran, for one, to point to Japan in defending the legitimacy of its own fuel cycle activities. South Korea, seeking American consent for a Korean recycling program, also cites Japan’s example in negotiating a replacement for the U.S.-ROK nuclear cooperation agreement that expires in 2016.

Controversial or not, Japan’s leaders feel compelled to push forward with Rokkasho and through an agreement under section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act,13 they enjoy the support of the United States government. American consent to Rokkasho is only guaranteed through 2018, but the United States, which granted consent in 1988 largely out of deference to diplomatic concerns, for the same reason is highly unlikely to withdraw consent in 2018. Given the effective concurrence of the 2018 date with U.S.-ROK negotiations and the looming startup of Rokkasho in the face of low (or no) capacity to consume MOX, timing has become extremely awkward.

As Rokkasho proceeds towards restart, public reaction from Washington has been surprisingly muted. Perhaps this reflects appreciation for the energy conundrum in which Japan finds itself, or tacit consent that bringing Japan’s nuclear industry back onto solid footing after the Fukushima disaster was always going to be awkward—Japan has an inherent chicken or egg dilemma in restarting Rokkasho and its reactors. But the reality is that Japan’s situation puts Washington in a very tough spot. Washington is effectively complicit in what might appear to be Japanese disregard for its own commitments to global nonproliferation. This poses a risk to the global nonproliferation regime and American credibility on the subject.

Implications

Global nonproliferation principles undoubtedly remain a high priority for Japan. But it is likely that in the short term, the eyes of Japan’s leaders are focused more intently on bringing nuclear reactors back on line. Particularly in the context of Prime Minister Abe’s provocative views on history, the perception outside of Japan is certain to be one of alarm if Japan is seen to be separating plutonium without a credible pathway for its disposition. While the coincidence of the 2016/2018 Korea and Japan 123 agreements and Japan’s reentry into nuclear energy will shine a spotlight on the American role in Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle scheme, it is seen as highly unlikely that the United States will attempt to withdraw from or renegotiate the 123 agreement with Japan irrespective of Japan’s plutonium balance concerns. This will effectively make the United States appear complicit in Japan’s growing inventory of plutonium.

For the United States, this situation has consequences on three fronts. Firstly, Japan’s apparent failure to abide by its plutonium commitments undercuts American interests in limiting fuel cycle capabilities through treaty agreements. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the ongoing U.S.-ROK 123 agreement negotiations. Secondly, Japan is a leader, if not the symbolic face of the global nonproliferation regime. For Japan to be separating plutonium for no demonstrable purpose dramatically undercuts its own leadership on nonproliferation and aggravates the already controversial precedent it sets with its fuel cycle program, elevating the risk of proliferation in the region. Thirdly, at just the time when the United States is working to underscore its alliance with Japan as the bedrock of its security presence in East Asia, Japan’s growing plutonium surplus will only exacerbate concerns of Japan’s return to militarism, eroding its legitimacy and efficacy as a partner in regional security.

In the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster, the United States has appeared somewhat ambivalent in its response to Japan’s efforts to restart its nuclear energy system. However, the American stake in Japan’s road ahead is profound. While it is not the case in all foreign capitals, in Tokyo, opinions and preferences from Washington are meaningful. Washington, particularly the Department of State and Department of Energy, has an opportunity to protect American interests by formulating and articulating an unambiguous American position on Japan’s path forward on nuclear energy to Japan’s leadership.

The critical interest of the United States would be for Japan to demonstrate clear commitment to the no-surplus plutonium policy and to the global nonproliferation regime. As elements of a policy that might be necessary to make that happen, the United States should urge Japan’s leadership and utilities to:

- Articulate a plan for plutonium disposition that provides quantifiable and publicly demonstrable benchmarks for reducing Japan’s plutonium inventory.

- Call for official, temporary suspension of operations at Rokkasho until MOX burners or another credible disposition pathway for Japan’s separated fissile materials, is available.

- Advocate operating Rokkasho (if and when started), at an output rate that is no more than commensurate with plutonium disposition goals and available means for plutonium disposition.

- Encourage utilization of temporary dry-cask storage of spent nuclear fuel in order to enhance safety at reactor sites while expanding nuclear fuel cycle policy options. One of the rare positive stories to emerge from the Fukushima Daiichi disaster was the robustness of dry cask storage. Utilities and the government should capitalize on this success story and prioritize arrangements with local communities to allow for expeditious transfer of spent nuclear fuel from wet-storage to on-site dry casks.

There is no nuclear weapons program in Japan’s foreseeable future. However, there is a significant risk of an outward appearance that suggests otherwise to South Korea, China, North Korea, Iran, and the rest of the world. Whether or not appearance differs from reality, the real world consequences would likely be the same. While Japan has serious and immediate energy concerns, it also has a very deep and fundamental commitment to global nonproliferation. With support from friends in Washington, Japan must face its looming nuclear energy challenges head on with eyes fully open. The stakes are too high to allow current circumstances to dictate their own outcomes.

Next year is the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The event would provide a fitting platform for Prime Minister Abe to recognize opportunities in Japan’s current crisis and make bold decisions on Japan’s nuclear energy program. The right decisions can help regain global confidence in Japan’s intentions, while reminding the world of Japan’s unwavering commitment to nuclear safety and nonproliferation. The anniversary would make an equally unfortunate occasion to demonstrate otherwise.

Ryan Shaffer is an Associate Director of Programs at the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation in Washington, D.C., where he manages Japan and Northeast Asia policy programs including the Mansfield-FAS U.S.-Japan Nuclear Working Group. Prior to joining the Mansfield Foundation, Mr. Shaffer served as a research analyst for the Federation of Electric Power Companies of Japan.

President’s Message: Complexity Overload and Extreme Events

To paraphrase Leon Trotsky’s saying about war but applied to extreme events, “You may not be interested in extreme events, but extreme events are interested in you.” The “you” here refers to the general public. I trust that readers of the Public Interest Report have self-selected themselves to be concerned about extreme events such as nuclear war, pandemics, and massive tsunamis triggering nuclear disasters. But the public has largely averted its gaze and would prefer not to contemplate “unthinkable” extreme events. Our task here at FAS is to convey to the public a better understanding of these events and provide better means to reduce and respond to them.

As I wrote in the previous president’s message, FAS is refocusing its mission on understanding, reducing, and responding to catastrophic risks. To further this mission, I have been looking for guidance as to how FAS can discover the intellectual talent and form the networks of specialists to help the world in dealing with catastrophic threats or extreme events. I recently found important insights in Dr. John Casti’s book X-Events: Complexity Overload and the Collapse of Everything, published in 2012. Dr. Casti, a mathematician and a former researcher at RAND and the Santa Fe Institute among other places, has been one of the foremost experts on complexity science. In his latest book, he argues that an extreme event or “X-event” is “human nature’s way of bridging a chasm between two (or more) systems.”

He gives the example of the gap between an authoritarian government (think Egypt under Hosni Mubarak) and the populace. The government has clamped down on people’s freedoms for decades using draconian methods and has been exceedingly corrupt and dysfunctional. Wanting outlets for political expression, citizens have been using social media tools such as Facebook and Twitter for political organizing. Dr. Casti points out that this development represents a growing, positive increase in the political capabilities of the citizenry—what he would term formation of a “high complexity” environment—versus an ossified, low-complexity government that is initially inclined to crush the protests instead of expanding freedoms. Dr. Casti argues that instead what the government should have done was to increase its complexity such that it could respond constructively to the protests. But it takes significant effort to bridge the complexity gap.

Seeking an easy way out of the perceived impasse, the Egyptian government’s initial response to the protests was to shut down the Internet in Egypt by ordering the country’s five main service providers to cut service on January 28, 2011, and the government also arrested several bloggers. U.S. President Barack Obama soon called on the Egyptian government to restore the Internet and give its citizens freedom of expression, and international service providers worked to find ways around the government’s cut in service. The Internet was restored on February 2, 2011, and the bloggers were released from prison. Mubarak was not so long afterwards deposed. As we have seen in the past two years, Egypt is still experiencing growing pains in its political transition, and it is not clear whether it will soon form a government responsive to its people’s needs. However, the movement illustrated the power of social networking tools in expanding people’s opportunities to organize and increase political complexity.

As Dr. Casti discusses in his book, there is a law of requisite complexity such that “the complexity of the controller has to be at least as great as the complexity of the system that’s being controlled.” For example, in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, the complexity of the control system (in particular, the height of the seawall and the location of the emergency diesel generators) was literally and figuratively too low to counter the higher complexity of the massive earthquake and tsunami.

I would also point out that the Japanese regulatory authorities and industry officials told the public for many years before the Fukushima accident that major nuclear accidents would not occur; this is the so-called nuclear safety myth. In effect, these authorities tried to sell the public on nuclear power being relatively low complexity. Today, Japan is faced with public mistrust and lack of confidence in nuclear power. The government has created a new regulatory agency called the Nuclear Regulation Authority. There are concerns that it is adopting too much of a deterministic approach to nuclear safety. That is, it is trying to achieve the strictest safety standards in the world by requiring many redundant safety systems at each nuclear plant to prevent further accidents. Instead, many experts outside of Japan are recommending a risk-informed approach that that uses multiple layers of safety systems but acknowledges that there will be some small level of risk. The question remains: can the Japanese public accept having some risk of a nuclear accident? Perhaps they can if the government and industry can demonstrate that it can handle high complexity events such as the possibility of accidents so as to protect the public from harm. For example, if the accident’s effects such as radioactivity release can be contained on the nuclear plant site, the public can be protected from radioactive contamination.

Can complexity mismatches be identified ahead of a catastrophe and steps taken to bridge the gap before catastrophe strikes? This is the message of the latter part of Dr. Casti’s book. He advises, for example, to look for major fluctuations and repeated occurrences in critical parameters of a system in order to forecast an impending catastrophe. For instance, in nuclear safety systems, one can look for repeated failures to inspect safety equipment, numerous unplanned shutdowns of plants due to exceeding thresholds in safety systems, and calls from whistleblowers about safety concerns. These are some major signs that urgent attention is needed.

How can governments and the public respond to avert such catastrophes? For example, a government needs to demonstrate its responsiveness to a crisis before it explodes into a catastrophe. Syria shows how lack of a government response to an environmental crisis triggered widespread public discontent and the recent civil war. As Tom Friedman wrote in the May 19 edition of the New York Times, the Syrian government did essentially nothing to help farmers deal with the massive drought that occurred a few years ago. Instead, President Bashar al-Assad’s policy of allowing big conglomerate farms to drain the very limited aquifers made Syria’s smaller farms acutely vulnerable to the drought. Out of work farmers flocked to Syria’s cities and began political organizing. The high unemployment further exacerbated people’s discontent with Assad’s government and helped spur the civil war. In hindsight, if Assad’s advisers could have foreseen this turn of events, they could have advised him to tend to the legitimate concerns of the farmers and other people out of work.

In another Arab country further south of Syria, water and political crises have been unfolding. But unlike Syria, Yemen might find a way out of its political crisis stopping short of civil war. Yemen confronts a major water disaster in that its capital Sana’a, according to some estimates, may run out of sufficient potable water in a decade, and numerous aquifers across the country are being drained faster than they can be refilled. But the good news is that after President Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down in 2012, the political factions in the country have begun a national dialogue. This process has encouragingly included many women leaders. Several women had led the protests demanding that then-President Saleh relinquish power. While there will undoubtedly be hurdles along this dialogue process, it is a sign of increasing positive political complexity. This is greatly needed for Yemen to have any hope of solving its water crisis in addition to the crises of shortages of energy and burgeoning population with high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

I invite you to contact FAS headquarters with your suggestions about how we can work together to use the insights of complexity science to better understand our complex world and work to reduce and respond to catastrophic risks.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists

New Report on Aftermath of Fukushima Nuclear Accident

The U.S.-Japan Nuclear Working Group, co-chaired by FAS President Dr. Charles Ferguson, has released a new report recommending priorities for the Japanese government following the March 11, 2011 nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

The U.S.-Japan Nuclear Working Group is composed of bi-national experts who have come together to examine the broader strategic implications of the Fukushima accident. The mission of the group is to understand, articulate and advocate for shared strategic interests between the United States and Japan which could be impacted through changes to Japan’s energy program. In the past twelve months, the group has conducted meetings with industry leaders and policymakers in Japan, the United States and the nuclear governance community in Vienna to examine the implications of Japan’s future energy policy. As a result of these meetings, the group released a report of its findings and recommendations, “Statement on Shared Strategic Priorities in the Aftermath of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident”.

The report discusses specific issues that must be addressed regardless of Japan’s energy policy decisions, including: strategy for reducing Japan’s plutonium stockpile, new standards for radiation safety and environmental cleanup and treatment of spent nuclear fuel.

The report also examines broader concerns to Japan’s energy policy including: climate change concerns, emerging nuclear safety regulations and global nuclear nonproliferation leadership (as Japan is a non-nuclear weapons state with advanced nuclear energy capabilities). The group offers strategic recommendations for Japanese and U.S. industries and governments regarding the direction of Japan’s energy policy, and how both countries can work together for joint energy security.

Read the report here (PDF).

For more information on the U.S.-Japan Nuclear Working Group, click here.

Japan’s Role as Leader for Nuclear Nonproliferation

A country with few natural resources, first Japan began to develop nuclear power technologies in 1954. Nuclear energy assisted with Japanese economic development and reconstruction post World War II. However, with the fear of lethal ash and radioactive fallout and the lingering effects from the 2011 accident at Fukushima-Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, there are many concerns related to Japanese nonproliferation, security and nuclear policy.

In a FAS issue brief, Ms. Kazuko Goto, Research Fellow of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of the Government of Japan, writes of Japan’s advancement of nuclear technologies which simultaneously benefits international nonproliferation policies.

The Future of Nuclear Power in the United States

In the wake of the devastating meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan, many Americans are now reevaluating the costs and benefits of nuclear energy. If anything, the accident underscores that constant vigilance is needed to ensure nuclear safety.

Policymakers and the public need more guidance about where nuclear power in the United States appears to be headed in light of the economic hurdles confronting construction of nuclear power plants, aging reactors, and a graying workforce, according to a report (PDF) by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and Washington and Lee University.

Nuclear Posture Review to Reduce Regional Role of Nuclear Weapons

|

| The Quadrennial Deference Review forecasts reduction in regional role of nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

A little-noticed section of the Quadrennial Defense Review recently published by the Pentagon suggests that that the Obama administration’s forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review will reduce the role of nuclear weapons in regional scenarios.

The apparent reduction coincides with a proposal by five NATO allies to withdraw the remaining U.S. tactical nuclear weapons from Europe.

Another casualty appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear-armed Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile, despite the efforts of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission.

New Regional Deterrence Architectures

Earlier this month President Barack Obama told the Global Zero Summit in Paris that the NPR “will reduce [the] role and number of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” The reduction in numbers will initially be achieved by the START follow-on treaty soon to be signed with Russia, but where the reduction in the role would occur has been unclear.

Yet the Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) published earlier this month strongly suggests that the reduction in the role will occur in the regional part of the nuclear posture:

“To reinforce U.S. commitments to our allies and partners, we will consult closely with them on new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent. These regional architectures and new capabilities, as detailed in the Ballistic Missile Defense Review and the forthcoming Nuclear Posture Review, make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (emphasis added)

There are two parts (with some overlap) to the regional mission: the role of nuclear weapons against regional adversaries (North Korea, Iran, and Syria); and the role of nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Rumors have circulated for long that the administration will remove the requirement to plan nuclear strikes against chemical and biological weapons from the mission; to limit the role to deterring nuclear attacks. Doing so would remove Iran, Syria and others as nuclear targets unless they acquire nuclear weapons. A broader regional change could involve leaving regional deterrence against smaller regional adversaries (including North Korea) to non-nuclear forces and focus the nuclear mission on the large nuclear adversaries (Russia and China).

An immediate consequence of the new architecture appears to be a decision to retire the nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). According to a report by Kyodo News (see also report by Daily Yomiuri), Washington has informally told the Japanese government that it intends to retire the weapon. The 2009 Congressional Strategic Posture Commission report had recommended retaining the weapons, but neither the Pentagon nor the Japanese government apparently agreed.

| Nuclear Tomahawk To Be Retired |

|

| The Obama administration has informally told the Japanese government that the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile will be retired. The retirement appears to be part of a new regional deterrence architecture that enables a reduction of the role of nuclear weapons. |

.

A Nuclear Withdrawal From Europe?

The other part of the regional mission concerns the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe, where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys 150-200 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Some of the TLAM/Ns also are earmarked for support of NATO, but are stored on land in the United States. The weapons are the last remnant of the Cold War deployment of thousands of tactical nuclear weapons to deter a Soviet attack on Europe. Similar deployments in the Pacific ended two decades ago and pressure has been building for NATO to finally end the Cold War.

Three of the five NATO countries that currently host the U.S. nuclear bombs on their territories are expected to ask for the weapons to be withdrawn, according to a report by AFP.

A spokesperson for the Belgian Prime Minister said that Belgium, German, and the Netherlands, together with Norway and Luxemburg, in the coming weeks will formally propose within NATO that “that nuclear arms on European soil belonging to other NATO member states are removed.”

Presumably, some coordination with Washington has taken place. Otherwise, if the NPR does not recommend a withdrawal from Europe, the five countries’ initiative will from the outset be in conflict with the Obama administration’s nuclear policy, which NATO likely will follow.

The European initiative would help the Obama administration justify a decision to withdraw the weapons from Europe by demonstrating that key NATO allies no longer see a need for the deployment. Extended nuclear deterrence would continue, as the QDR language underscores, but with long-range strategic weapons as it is done in the Pacific.

Other than the forthcoming NPR, the political context for the European initiative is NATO’s ongoing review of its Strategic Concept, scheduled for completion in November. The Obama administration might not want to preempt that review, so an alternative could be that the NPR concludes that the U.S. sees no need for the continued deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe but leaves it up to NATO’s new Strategic Concept to make the formal decision. In that case, the initiative by the five NATO countries could serve to formally start that process within NATO. (see comments by U.S. NATO Ambassador Ivo Daalder)

Whether that means a complete withdrawal from Europe now, a decision to end the NATO strike portion (a controversial Cold War mission that assigns nuclear weapons for delivery by Belgian, Dutch, German, and Italian aircraft) and consolidating the remaining weapons at one or two U.S. bases in Europe, or something else remains to be seen. But a reduction rather than complete withdrawal would achieve little.

Heated Debate

The debate over the deployment in Europe is in full swing, recently triggered by the new German government’s decision to work for a withdrawal.

A paper by Franklin Miller, a former top-Pentagon official in charge of the deployment in Europe, and former NATO head George Robertson calling the German position dangerous was rejected as old-fashioned thinking on the New York Times’ opinion pages by Wolfgang Ischinger, Germany’s former foreign deputy foreign minister and chairman of the Munich Security Conference, and Ulrich Weisser, a former director of the policy planning staff of the German defense minister.

And suggestions by some supporters of continued deployment that Eastern European countries oppose withdrawal have suffered recently with Poland’s Prime Minister Radek Sikorski calling for the reduction and elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and a report from the Polish Institute of International Affairs in March 2009 that appeared to question the need for the nuclear deployment.

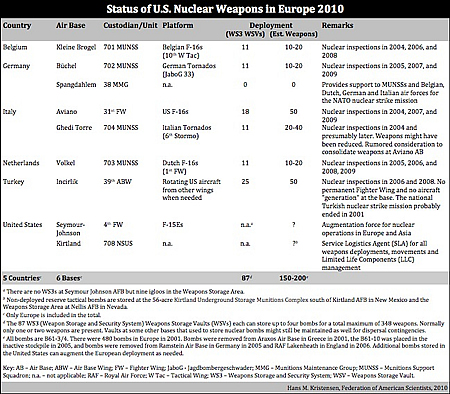

Status of U.S. Nuclear Deployment in Europe

The U.S. Air Force currently deploys an estimated 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs in 87 aircraft shelters at six bases in five countries, a reduction from approximately 480 bombs in 2001. The breakdown by country looks like this:

|

| Click image to download larger pdf-version. |

.

Additional Background: History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Japanese Government Rejects TLAM/N Claim

|

| Katsuya Okada and Hillary Clinton met in September 2009. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Japanese government has officially rejected claims made by some that Japan is opposed to the United States retiring the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile (TLAM/N).

The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States from May 2009 emphasized the importance of maintaining the TLAM/N for extended deterrence in Asia by referring to private conversations with specifically “one particularly important ally” (read: Japan) that “would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

In a letter sent to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on December 24, 2009, Japanese Foreign Minister Katsuya Okada explicitly says that the Japanese government has expressed no such views.

The Japanese Foreign Minister’s letter explicitly refers to the Commission: “It was reported in some sections of the Japanese media that, during the production of the report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States released in May this year, Japanese officials of the responsible diplomatic section lobbied your government not to reduce the number of its nuclear weapons, or, more specifically, opposed the retirement of the United States Tomahawk Land Attack Missile – Nuclear (TLAM/N) and requested that the United States maintain a Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP).

I don’t know who made a reference to RNEP (the Commission didn’t; perhaps it was a reference to earth-penetration capabilities in general rather than RNEP per ce), but Okada’s rejection of the TLAM/N claim is clear:

“[A]lthough the discussions were held under the previous Cabinet, it is my understanding that, in the course of exchanges between our countries, including the deliberations of the above mentioned Commission, the Japanese Government has expressed no view concerning whether or not your government should possess particular [weapons] systems such as TLAM/N and RNEP.” (my emphasis)

Okada’s statement suggests that he has checked the government’s files. It also matches the statement made by Admiral Timothy J. Keating, the former Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, in July 2009, that he was “unaware of specific Japanese interests in the” TLAM/N.

If the TLAM/N were retired, Okada says, Japan would of course like to be informed about how this would affect extended deterrence and how it could be supplemented. I hope “supplemented” means by other existing nuclear and non-nuclear means, not by new nuclear weapon system.

It seem so, because Okada writes that he favors nuclear disarmament, and he also expresses interest in the proposal made recently by the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament (ICNND) – and many others – that the role of nuclear weapons be restricted to deterrence of the use of nuclear weapons. That is important for the Japanese government to say because one of the current missions for U.S. nuclear weapons involve North Korean chemical and biological attacks on Japan. Apparently, closer consultations between the United States and Japan on extended deterrence issues would be a good idea.

It seems more and more that the TLAM/N claim resulted from a shady collusion between a few U.S. and Japanese officials (some current and some former) who sought to present private views as more than that in an effort to put brakes on the Obama administration’s disarmament agenda.

Hopefully the pending Nuclear Posture Review will not be led astray.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Japan, TLAM/N, and Extended Deterrence

|

| PACOM Commander Admiral Keating is “unaware” of the Japanese interest in the nuclear Tomahawk cruise missile reported by the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Admiral Timothy J. Keating, who is Commander of U.S. Pacific Command, said Monday that he is “unaware of specific Japanese interests in the” nuclear-armed Tomahawk Land-Attack Missile.

That’s interesting because the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission recently pointed explicitly to such a Japanese interest in the role that the missile – known as the TLAM/N – provides in extending a U.S. nuclear umbrella over Japan to deter nuclear attacks against it from China and other potential adversaries in the region.

We would expect the commander of Pacific forces to be in close contact with the highest levels of the Japanese government and military. Shouldn’t he be aware of a specific Japanese interest in specific weapons for the U.S. nuclear umbrella? So statements to the contrary in the recent Congressional Commission report seem odd and worth investigating.

The Claims

The final report of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States of America makes several claims about Japan and the TLAM/N, primarily that:

“extended deterrence [in Asia] relies heavily on the deployment of nuclear cruise missiles on some Los Angeles class attack submarines—the Tomahawk Land Attack Missile/Nuclear (TLAM/N). This capability will be retired in 2013 unless steps are taken to maintain it. U.S. allies in Asia are not integrated in the same way into nuclear planning and have not been asked to make commitments to delivery systems. In our work as a Commission it has become clear to us that some U.S. allies in Asia would be very concerned by TLAM/N retirement.”

Indeed, the report states that the TLAM/N is “primarily relevant to extended deterrence to allies in Asia.”

According to several sources, Japanese government officials provided the Commission with a written list of requirements for the nuclear umbrella. Neither the list not the wording of the Japanese statements are included in the report, which provides the following statement without mentioning Japan by name: “One particularly important ally has argued to the Commission privately that the credibility of the U.S. extended deterrent depends on its specific capabilities to hold a wide variety of targets at risk, and to deploy forces in a way that is either visible or stealthy, as circumstances may demand.”

The U.S. Nuclear Posture in the Pacific

The United States has approximately 300 nuclear-armed TLAM/N, of which about half are stored in igloos at Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC) near Bangor, Washington (the other half or so are at Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic (SWFLANT) at Kings Bay, Georgia).

Only about 100 of the TLAM/N warheads are active with limited-life components installed, but none of the missiles are deployed on attack submarines under normal circumstances. Less than a dozen of the 53 U.S. attack submarines are capable of firing the TLAM/N, and although the boats and crews periodically undergo training and inspections to certify them for the mission, they are de-certified again to focus on real-world non-nuclear missions. It would take several months to ready the missiles, recertify the submarines, and deploy the missiles at sea.

The approximately 150 TLAM/N at SWFPAC represent but a fraction of the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific, which includes well over 1,000 W76 and W88 warheads for Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) on eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) patrolling the Pacific Ocean. Five-six of the eight Pacific SSBNs with an estimated 480-570 warheads onboard are deployed at any given time. Hundreds of additional warheads stored at SWFPAC are available for increasing loading on the SSBNs to an estimated 1,300 warheads if necessary.

| USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) in Hawaii |

|

| The nuclear umbrella over Japan is supported by a huge nuclear arsenal in the Pacific region, including SSBNs such as this one that continuously patrol the Pacific and occasionally make their presence known by visiting Hawaii and other Pacific ports. |

In addition to this sea-based force, a portion of the 500 warheads on 450 Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) also cover strike options in the PACOM region, as do B-2 and B-52H bombers with nuclear bombs and cruise missiles. Moreover, F-15Es of the 4th Fighter Wing at Seymour-Johnson Air Force Base in North Carolina have contingency a nuclear strike mission in the Pacific (and elsewhere).

In addition to these nuclear forces, the U.S. Navy is moving 60 percent of its carrier battle groups and nuclear attack submarines into the Pacific. One of these battle groups is even homeported in Japan. Naval exercises in the Pacific are now bigger than even during the Cold War. The Air Force is rotating long-range bomber squadrons to Guam more or less continuously.

Why, given these extensive U.S. forces earmarked for the Pacific region, anyone in Tokyo, Washington, Beijing or Pyongyang would doubt the U.S. capability to project a nuclear umbrella over Japan – or see the TLAM/N as essential – is puzzling. While not all of these warheads are necessarily intended for the defense of Japan per ce, just how many are is probably irrelevant for the purpose of deterrence and assurance. Even if the posture were cut by fifty percent, more than three times the entire Chinese nuclear stockpile would still remain, enough to deter any real-world adversary – to the extent anything can.

The Nuclear Lobby: Articulating a Persuasive Nuclear Mission

So why do we suddenly hear all this talk of Japan being deeply worried about the future of a few hundred TLAM/Ns? After all, nearly all U.S. presidents since Kennedy have called for the elimination of nuclear weapons. As a nuclear target in World War II Japan has always called for the elimination of nuclear weapons, perhaps a little disingenuous given its reliance on the U.S. nuclear umbrella and Japanese officials privately saying that elimination probably wouldn’t happen anyway. Yet the growing international momentum across the traditional political trench-lines for moving convincingly down the nuclear ladder toward zero appears to have caught some in the Japanese government by surprise. Now they suddenly have to think about what it means to move toward zero, and change is always hard.

Another reason appears to be that the end of the Cold War and a growing momentum toward a nuclear free world – even supported by even the presidents of the United States and Russia – have left defense hawks and nuclear proponents on the defensive. Chinese modernization, rogue states, and terrorism haven’t quite been able to sustain the nuclear vigor after the demise of the Soviet threat. In that void, obscure and confidential statements from Japanese and other allied officials about extended deterrence have suddenly become essential tools in an attempt to articulate a persuasive – even positive – enduring role for nuclear weapons. The essence of the message is: nuclear weapons prevent proliferation of nuclear weapons and without them more will come.

It’s tempting to see a collusion. In December 2006, the Defense Science Board (DSB) task force on nuclear capabilities warned that “entrenched views” of arms control advocates had robbed the United States of its “national consensus” on the role of nuclear weapons. The White House and senior leaders had to “engage more directly to articulate the persuasive case” for how modern nuclear weapons serve U.S. national security policy.

After clumsy attempts to get Congressional approval for Complex 2030 and the Reliable Replacement Program backfired and instead caused Congress to ask for a review of nuclear policy, a four-page joint DOD-DOE-State Department statement in July 2007 attempted to articulate one but fell short. And although the loss of control of six nuclear warheads at Minot Air Force Base the following month initially put the nuclear enterprise in doubt, the incident has since become an important vehicle for arguing the case urged by the DSB. During the past 12 months, a series of reports by government agencies and defense institutes have emerged that echo the same basic themes of an enduring role for nuclear weapons, need for modernizations, and continued nuclear threats. The extended deterrence mission underpins these themes:

* September 2008: Schlesinger Task Force Phase I report on the Air Force’s nuclear mission

* September 2008: joint DOD-DOE report on nuclear weapons in the 21st century

* October 2008: Air Force Task Force report on reinvigorating the Air Force nuclear enterprise

* January 2009: Schlesinger Task Force Phase II report on the DOD nuclear mission

* May 2009: Congressional Commission report on the strategic posture of the United States.

These reports, authored by agencies and individuals that are or have been deeply involved in the nuclear business (and many of which “ran the Cold War”), argue for a reaffirmation – even strengthening – of extended deterrence as a “good” and enduring mission for nuclear weapons to prevent proliferation in the 21st Century. They argue that since the U.S. nuclear umbrella is extended to some 30 countries (one report even says 30-plus countries; I can only count 30) it prevents them from acquiring nuclear weapons themselves. Yet for the overwhelming majority of those countries, the function of the extended deterrent is not about nonproliferation but about the ultimate security guarantee. The number of those countries that could potentially be expected to develop nuclear weapons if the U.S. nuclear umbrella disappeared is very small, perhaps a couple, and whether they would actually do so depends on a wide spectrum of factors, most of which have nothing to do with nuclear weapons. Yet the reports paint the role of nuclear weapons as alpha omega.

| James Schlesinger |

|

| James Schlesinger, who like many other key contributors to recent nuclear studies helped shape Cold War nuclear planning, has been granted a powerful role in articulating post-Cold War policy. |

The September 2008 Schlesinger report describes a “daily” contribution of nuclear weapons, a theme that is echoed by many of the other reports and has been used in testimony before Congress: “Though our consistent goal has been to avoid actual weapons use, the nuclear deterrent is ‘used’ every day by assuring friends and allies, dissuading opponents from seeking peer capabilities to the United States, deterring attacks on the United States and its allies from potential adversaries, and providing the potential to defeat adversaries if deterrence fails.”

One has to be very careful about such nuclear dogma because it quickly can balloon the perceived contribution, mission, and requirements beyond reality. Since the end of the Cold War, which country can we actually say has been deterred by nuclear weapons from attacking anyone, which country has been dissuaded by nuclear weapons from pursuing advanced military capabilities, and which allied or friendly country has been assured by nuclear weapons from pursuing nuclear weapons? This list is very small and the evidence dubious and circumstantial even in the best cases.

Yet the combined effect of these studies and the lobbying that accompany them appears to be setting the tone, at least at the outset, for the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. Extended deterrence has risen to the top of the agenda and has been assigned to one of only four working groups in the review (International Dimensions), instead of incorporating analysis of that mission into the Policy and Strategy working group like the other missions.

Concluding Remarks

It is impossible to say to what extent Admiral Keating was aware of the public relations battle that is raging on the nuclear extended deterrence front when he gave his answer at the Atlantic Council. I think he was. He certainly looked like he was choosing his words very carefully.

Nuclear advocates and defense hawks appear to be milking the extended deterrence mission for all it’s worth to secure funding for pet projects such as the TLAM/N, a replacement missile, and a nuclear role for the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, capabilities that are not needed. Yet the Congressional Commission report concludes that assuring allies that the U.S. extended deterrent remains credible and effective “may require that the United States retain numbers or types of nuclear capabilities that it might not deem necessary if it were concerned only with its own defense.” Indeed, the Commission said, echoing the January 2009 Schlesinger report, the extended deterrence mission has “design implications for the posture” and nuclear weapons “modernization is essential to the non-proliferation benefits derived from the extended deterrent”.

| Admiral Timothy J. Keating |

|

| The head of PACOM, Admiral Timothy Keating, says he is “unaware of specific Japanese interest in that particular system” (TLAM/N) described recently by the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission. |

The issue is not whether there should be an extended deterrent or not but what characteristics it needs to have and for what purpose. Nuclear cruise missiles and dual-capable fighter aircraft are characteristics of what nuclear extended deterrence looked like the Cold War, but they might not be necessary or even appropriate today. Long-range systems might be sufficient. Whatever Japanese officials have said about the composition and role of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, there is probably more to the story than meets the eye. Even if some Japanese express a unique value in the TLAM/N – the U.S. military certainly does not share that view – what they say might tell us more about what deterrence literature and Cold War history they have read and which U.S. officials they meet with.

To that end I find it curious that the Japanese government apparently has not brought its alleged interest in the TLAM/N to the attention of PACOM even though that command works with Japanese officials on a daily basis to provide the military capabilities that make up the U.S. security guarantee to Japan. And it is not because PACOM is not aware of their interest in the nuclear umbrella. In the words of Admiral Keating, responding to a question from Miles Pompers from the Center for Nonproliferation Studies:

“As I move around the [PACOM Area of Responsibility]…sooner or later many of the folks with whom we have discussions will get around to asking ‘is your nuclear deterrent umbrella going to continue to extend over’ fill-in-the-blank country? So our capabilities in this area are not taken for granted all throughout our area of responsibility. Everywhere I go, sooner or later – not just in mil-to-mil – the conversation comes up.

I am unaware of specific Japanese interest in that particular system [TLAM/N] you describe. I am, as I said, aware of Japanese interest in the nuclear umbrella.”

It is important for the quality and credibility of the nuclear extended deterrent debate here in the United States and elsewhere to see what the Japanese officials have said and provided, what status and function the officials have within the Japanese government (the Commission report only identifies four individuals from the Japanese embassy in Washington, D.C.), and exactly what they were asked and by whom. The reason is, as all officials know, that questions asked and answers given are always influenced by such factors. It would serve neither the United States nor its allies if the future U.S. nuclear extended deterrence policy and capabilities were to fall victim to bias and special interests.