Declassified U2 Photos Open a New Window into the Past

Updated below

Archaeologists are using declassified imagery captured by U2 spy planes in the 1950s to locate and study sites of historical interest that have since been obscured or destroyed.

This work extends previous efforts to apply CORONA spy satellite imagery, declassified in the 1990s, to geographical, environmental and historical research. But the U2 imagery is older and often of higher resolution, providing an even further look back.

“U2 photographs allowed us to present a more complete picture of the archaeological landscape than would have otherwise been possible,” wrote archaeologists Emily Hammer and Jason Ur in a new paper. See Near Eastern Landscapes and Declassified U2 Aerial Imagery, Advances in Archaeological Practice, published online March 12, 2019.

The exploitation of U2 imagery required some ingenuity and entrepreneurship on the authors’ part, especially since the declassified images are not very user-friendly.

“Logistical and technical barriers have for more than a decade prevented the use of U2 photography by archaeologists,” they noted. “The declassification included no spatial index or finding aid for the planes’ flight paths or areas of photographic coverage. The declassified imagery is not available for purchase or download; interested researchers must photograph the original negatives at the NARA II facility in College Park, Maryland.”

Since no finding aids existed, the authors created them themselves. Their paper also contains links to web maps to help other researchers locate relevant film cans and order them for viewing in College Park.

“These [U2] photographs are a phenomenal historical resource,” said Professor Ur. “Have a look at Aleppo in 1959 and Mosul in 1958. These places are now destroyed.”

Update: Related work involving declassified aerial imagery in the UK was described in “Use of archival aerial photographs for archaeological research in the Arabian Gulf” by Richard N. Fletcher et al, Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies 48 (2018): 75–82:

- Summary

A valuable archaeological and historical resource is contained within recently declassified aerial imagery from the UK’s Joint Aerial Reconnaissance Intelligence Centre (JARIC), now held at the National Collection of Aerial Photography in Edinburgh (NCAP). A project at UCL-Qatar has begun to exploit this to acquire and research the historical aerial photography of Qatar and the wider Gulf region. The JARIC collection, comprising perhaps as many as 25 million photographs from British intelligence sources in the twentieth century, mainly from Royal Air Force reconnaissance missions, is known to include large quantities of aerial photography from the Gulf that have never been seen outside intelligence circles, dating from 1939 to 1989. This paper will demonstrate how others may gain access to this valuable resource, not only for the Gulf but for the entire MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. We will explore the research value of these resources and demonstrate how they enrich our understanding of the area. The archive is likely to be of equal value to archaeologists and historians of other regions.

Intelligence Transparency– But For What?

The new National Intelligence Strategy released last week by DNI Dan Coats affirms transparency as a value and as a strategic priority for U.S. intelligence.

The declared purpose of intelligence transparency is to raise public esteem for intelligence and to engender public trust. But because the policy is framed primarily as a public relations effort, the resulting transparency is limited unnecessarily.

“Through transparency we will strengthen America’s faith that the Intelligence Community seeks the truth, and speaks the truth,” DNI Coats said.

“This will be our hallmark, and I cannot stress this enough — this is not a limitation on us. This will make us stronger. It earns trust. It builds faith, and boosts our credibility around the world for our mission. It is the right thing to do,” he said on January 22.

The latest iteration of intelligence transparency was strongly shaped by the immediate post-Snowden environment, and it began, under then-DNI James Clapper, as an effort to restore public confidence which had been shaken by his disclosures. The legitimacy and legality of U.S. intelligence surveillance activities had been called into question, and the scope of domestic intelligence collection was revealed to a surprising new extent. In response, the intelligence transparency initiative therefore emphasized disclosure of IC legal authorities, oversight mechanisms, and the nature of IC electronic surveillance programs.

(Similar transparency has not extended to covert action, overhead reconnaissance, procurement, contracting, or numerous other areas. Declassification has been highlighted but has been preferentially focused on topics that are historically and substantively remote, such as the 1968 Tet Offensive.)

Has such transparency actually led to increased public trust in intelligence?

Data on the subject are sparse. It seems likely that most members of the public neither trust nor distrust intelligence agencies, being more concerned with other matters. However, increased transparency concerning surveillance practices has helped to focus current debate on real issues and pending policy questions rather than on more speculative topics. There is a qualitative difference between the precision of the public debate over Section 215 surveillance authority and the foggy controversy over the reputed “Echelon” surveillance program of the 1990s.

Public trust may be conditional on some degree of transparency, and undue secrecy may engender suspicion. But it is doubtful that transparency by itself would generate increased trust. It might just as easily lead to heightened opposition.

Public trust is more likely to be produced as a byproduct of agency competence and integrity. Intelligence community leaders gained credibility and respect this week by publicly differing with the White House on North Korean denuclearization (assessed as “unlikely” to be completed), Iran’s nuclear weapons program (which is “not currently undertaking” steps needed to produce a nuclear device), among other divergent views expressed at the annual threat hearing held by the Senate Intelligence Committee. (The differences elicited an angry outburst from the President.)

In any case, building public trust is not the only possible rationale for intelligence transparency. Increasing public literacy in national security matters and enriching public debate offer an alternative, and more comprehensive, goal for future intelligence transparency efforts.

At a time when even basic factual matters are in dispute, the intelligence community could perform a public service — something analogous to what the Congressional Research Service does on a different plane — by routinely adding substantive information and analysis to the public domain. CIA and other agencies are sitting on a wealth of unclassified, open source material (which is sometimes utilized by CRS itself) that could easily be shared with the public at marginal cost.

It is possible that some unclassified, open source materials might be deemed sensitive and would therefore be withheld, either because their disclosure would reveal a specific target of intelligence collection or because they provide the US government with “decision advantage” of some kind.

But even allowing for such withholding, a vast array of existing unclassified open source intelligence analysis should be releasable. A grab bag of open source intelligence products that were obtained through unauthorized disclosures a decade ago illustrates the kind of materials that could be released on a near-daily basis.

“Whenever possible, we will share with the public the insight we offer to policymakers,” DNI Coats said last week. For now, there remains a great deal of useful but undisclosed intelligence material that should be possible to share with the public.

CIA Historical Review Panel Put on Hiatus

The Historical Review Panel that advises the Central Intelligence Agency on declassification of historical intelligence records said this week that its planned December 2018 meeting was canceled by CIA, and that no future meetings were scheduled.

But CIA said yesterday that the Panel would be reconvened following some administrative changes.

“We have recently been informed that the Panel is being restructured and will not meet again until this has been done,” said the Panel of independent historians, chaired by Prof. Robert Jervis of Columbia University, in a January 14 statement published on H-DIPLO. “The reasons for this remain unclear to us, and no schedule for resumed meetings has been announced.”

Upon further investigation, it appears that changes may be made regarding composition of Panel membership, term limits, and similar issues but that the scope of the Panel’s activities will be unaffected. The reconstituted Panel is expected to meet again sometime this year.

“The CIA is committed to the public release of historical information, and the Historical Review Panel remains an important and valuable resource for this endeavor,” said CIA spokesperson Sara Lichterman.

The Panel is purely advisory and does not make or execute policy. But it serves to represent the concerns of historians regarding declassification of intelligence records. It has helped to prioritize records of particular interest for declassification and to facilitate production of intelligence records for the Foreign Relations of the United States series. And perhaps most important, through its periodic meetings with the CIA Director, it has helped to elevate historians’ concerns about intelligence declassification within the Agency.

Israel’s Official Map Replaces Military Bases with Fake Farms and Deserts

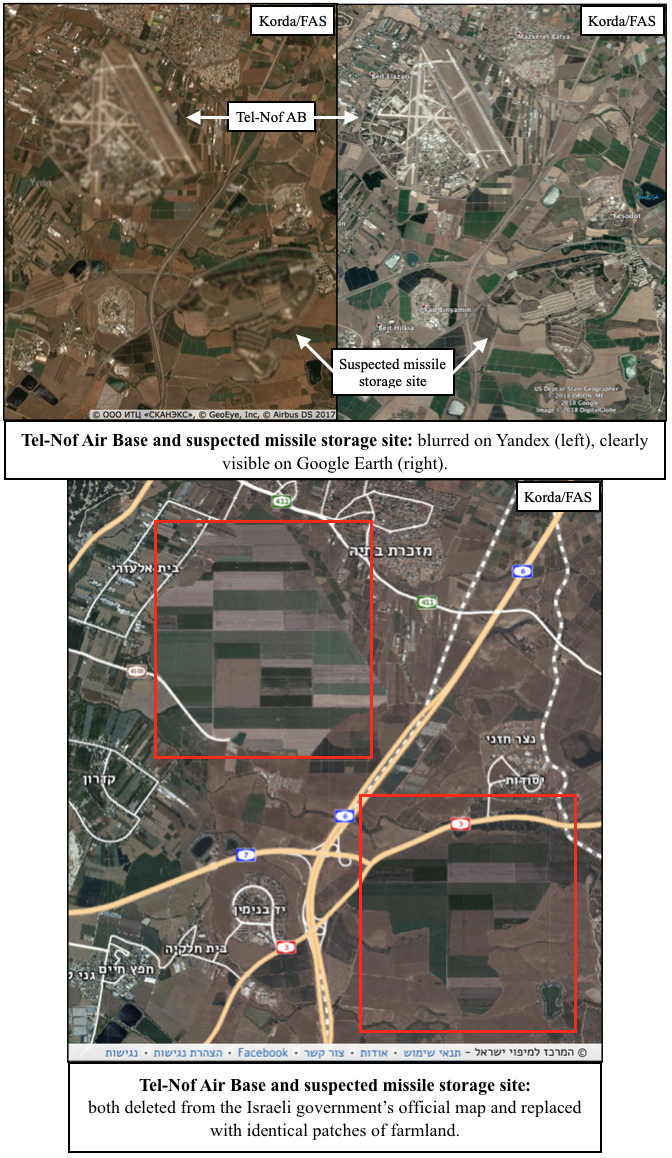

Somewhat unexpectedly, a blog post that I wrote last week caught fire internationally. On Monday, I reported that Yandex Maps—Russia’s equivalent to Google Maps—had inadvertently revealed over 300 military and political facilities in Turkey and Israel by attempting to blur them out.

In a strange turn of events, the fallout from that story has actually produced a whole new one.

After the story blew up, Yandex pointed out that its efforts to obscure these sites are consistent with its requirement to comply with local regulations. Yandex’s statement also notes that “our mapping product in Israel conforms to the national public map published by the government of Israel as it pertains to the blurring of military assets and locations.”

The “national public map” to which Yandex refers is the official online map of Israel which is maintained by the Israeli Mapping Centre (מרכז למיפוי ישראל) within the Israeli government. Since Yandex claims to take its cue from this map, I wondered whether that meant that the Israeli government was also selectively obscuring sites on its national map.

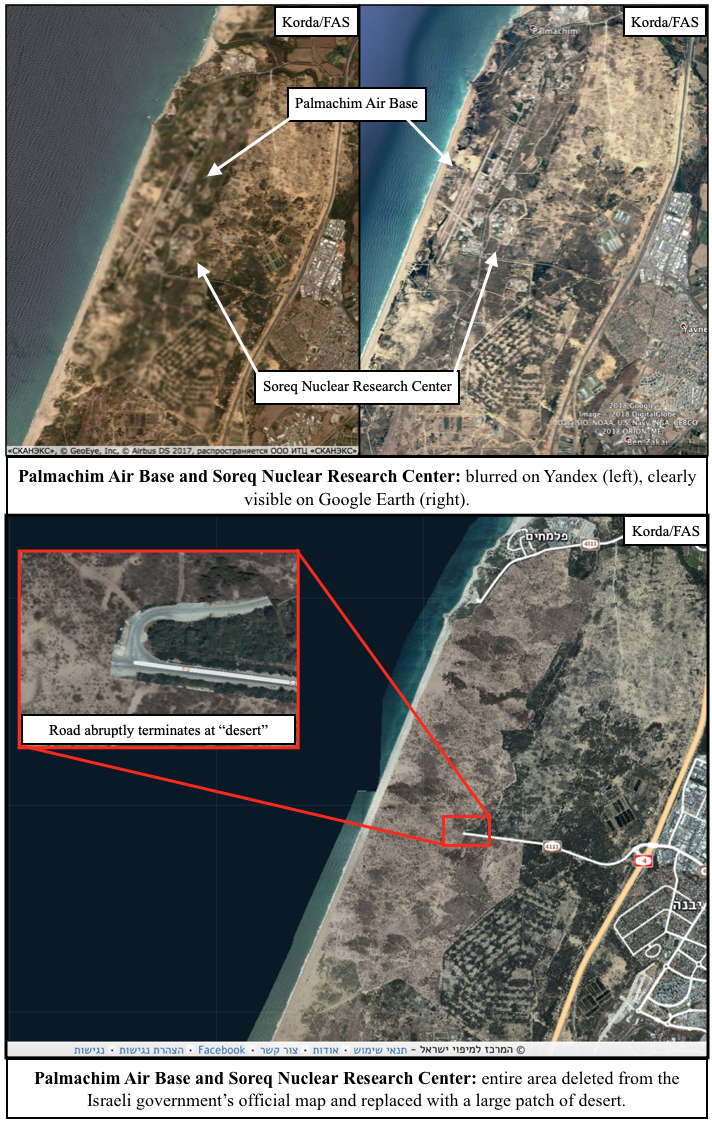

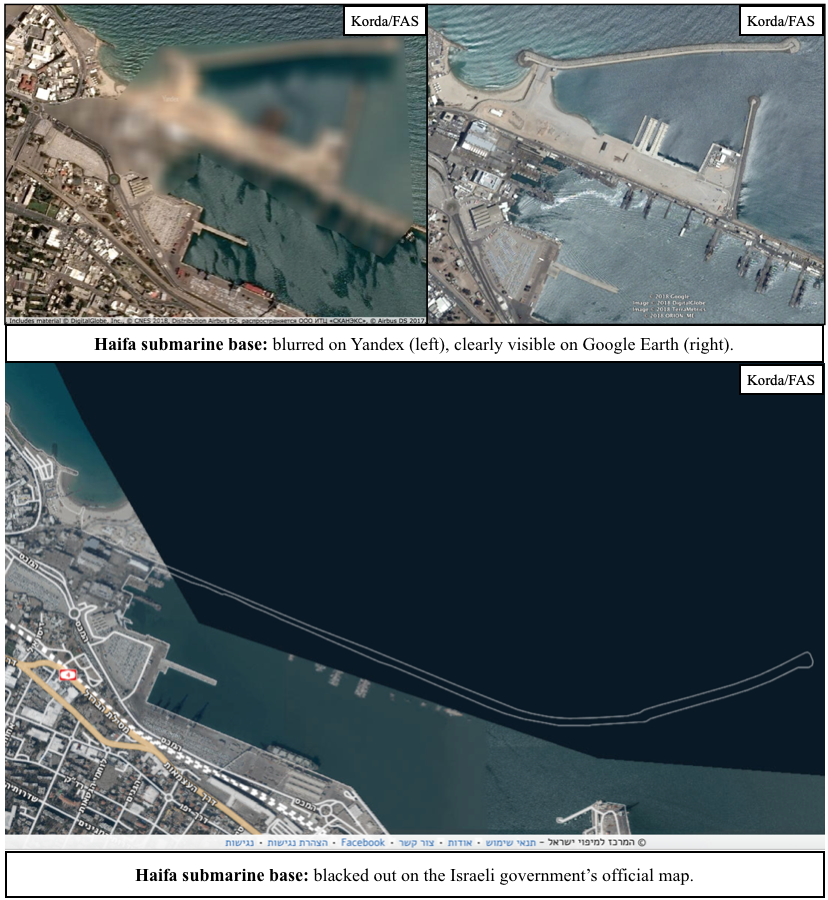

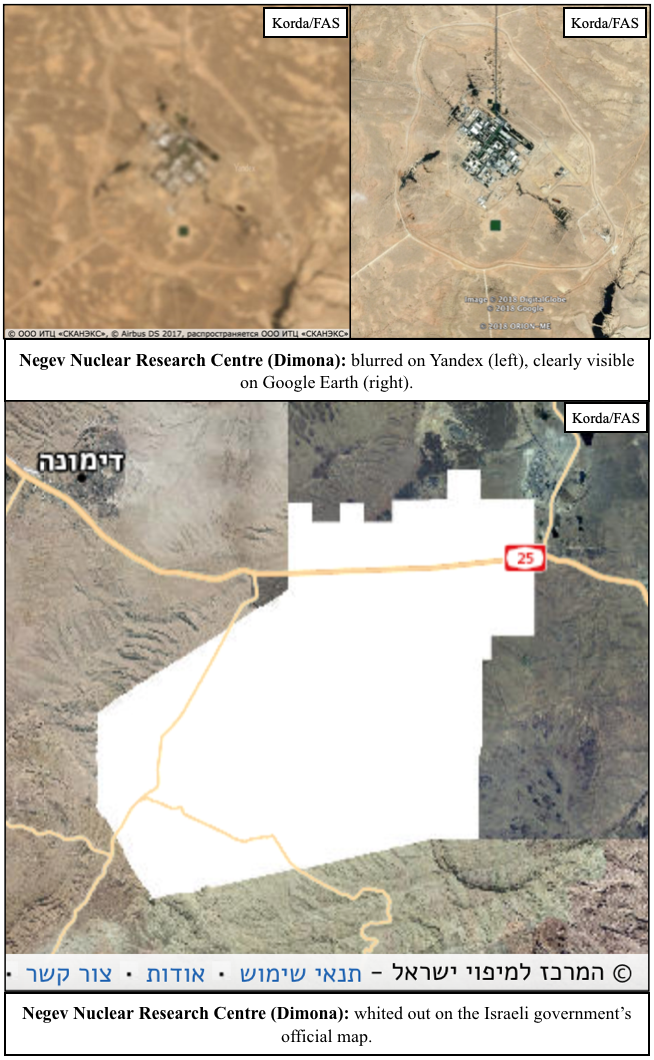

I wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Israeli government goes well beyond just blurring things out. They’re actually deleting entire facilities from the map—and quite messily, at that. Usually, these sites are replaced with patches of fake farmland or desert, but sometimes they’re simply painted over with white or black splotches.

Some of the more obvious examples of Israeli censorship include nuclear facilities:

- Tel-Nof Air Base is just down the road from a suspected missile storage site, both of which have been painted over with identical patches of farmland.

- Palmachim Air Base doubles as a test launch site for Jericho missiles and is collocated with the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, which is rumoured to be responsible for nuclear weapons research and design. The entire area has been replaced with a fake desert.

- The Haifa Naval Base includes pens for submarines that are rumoured to be nuclear-capable, and is entirely blacked out on the official map.

- The Negev Nuclear Research Center at Dimona is responsible for plutonium and tritium production for Israel’s nuclear weapons program, and has been entirely whited out on the official map.

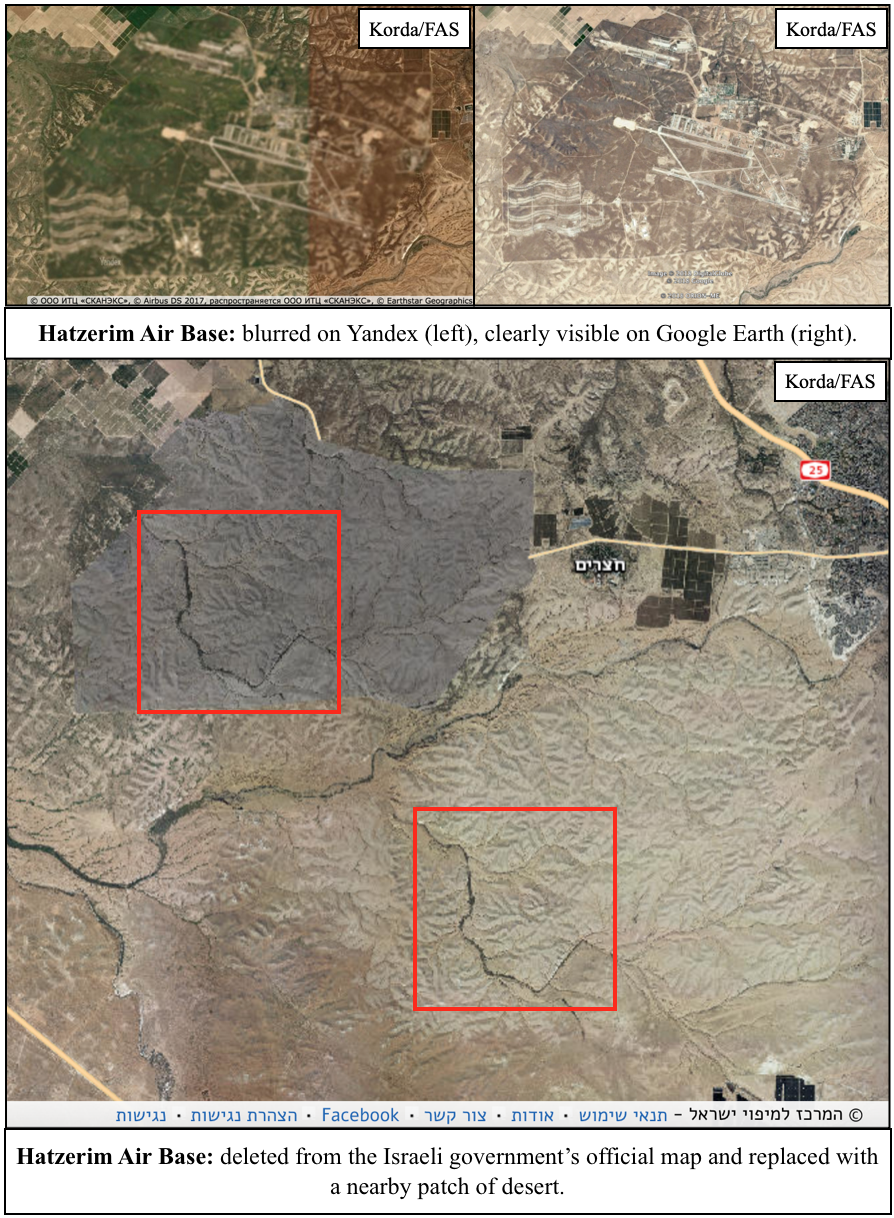

- Hatzerim Air Base has no known connection to Israel’s nuclear weapons program; however, the sloppy method that was used to mask its existence (by basically just copy-pasting a highly-distinctive and differently-coloured patch of desert to an area only five kilometres away) was too good to leave out.

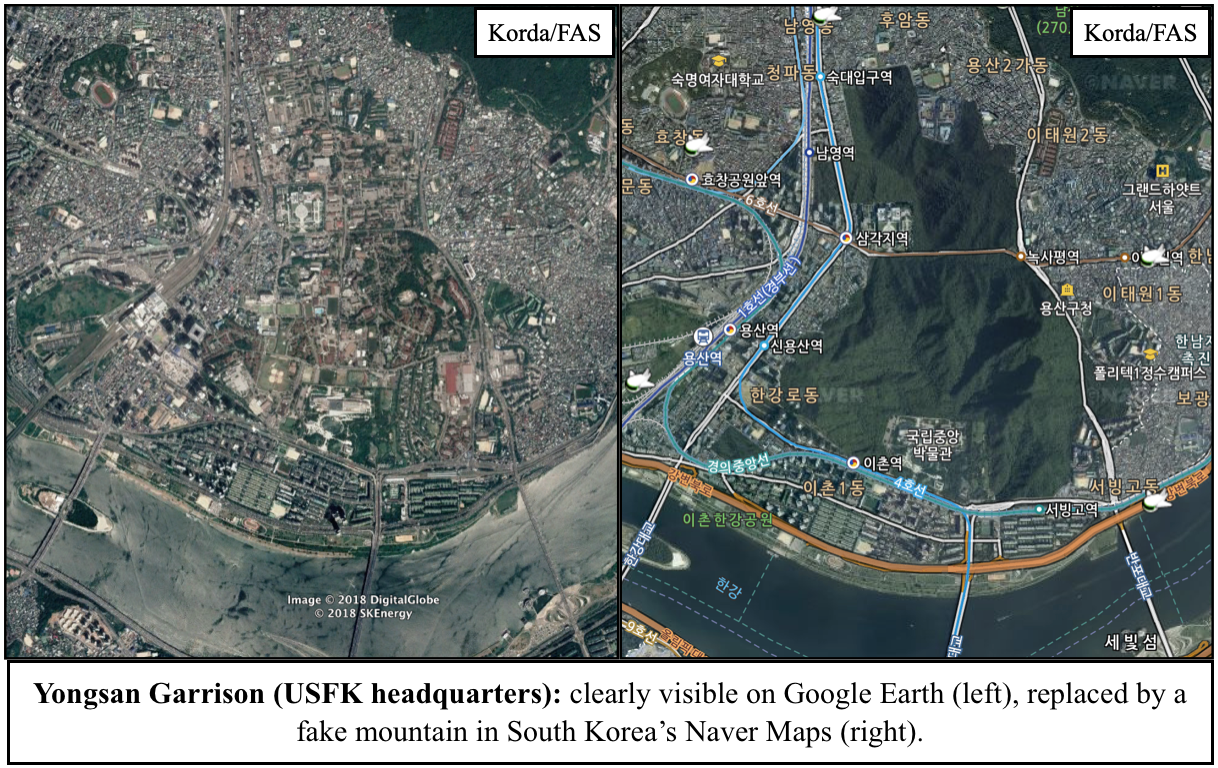

Given that all of these locations are easily visible through Google Earth and other mapping platforms, Israel’s official map is a prime example of needless censorship. But Israel isn’t the only one guilty of silly secrecy: South Korea’s Naver Maps regularly paints over sensitive sites with fake mountains or digital trees, and in a particularly egregious case, the Belgian Ministry of Defense is actually suing Google for not complying with its requests to blur out its military facilities.

Before the proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery, obscuring aerial photos of military facilities was certainly an effective method for states to safeguard their sensitive data. However, now that anyone with an internet connection can freely access these images, it simply makes no sense to persist with these unnecessary censorship practices–especially since these methods can often backfire and draw attention to the exact sites that they’re supposed to be hiding.

Case studies like Yandex and Strava—in which the locations of secret military facilities were revealed through the publication of fitness heat-maps—should prompt governments to recognize that their data is becoming increasingly accessible through open-source methods. Correspondingly, they should take the relevant steps to secure information that is absolutely critical to national security, and be much more publicly transparent with information that is not—hopefully doing away with needless censorship in the process.

New Pre-Publication Review Policy is Coming

Two years ago, the House Intelligence Committee asked the Director of National Intelligence to improve the government’s controversial policy on reviewing books, articles and speeches by current and former intelligence employees prior to their publication, so as to make the process more uniform, timely and fair.

That has still not been accomplished, but a new policy is on the way, according to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence.

“An IC-wide policy on prepublication review is being formulated and is forthcoming,” wrote ODNI FOIA Chief Sally A. Nicholson on November 20. “However, it is not completed as of today’s date.”

In 2016, the House Intelligence Committee reported that it is “aware of the perception that the pre-publication review process can be unfair, untimely, and unduly onerous and that these burdens may be at least partially responsible for some individuals ‘opting out’ of the mandatory review process. The Committee further understands that IC agencies’ pre-publication review mechanisms vary, and that there is no binding, IC-wide guidance on the subject.”

The Committee specified its own view of what a new, improved policy should entail, including a clear statement of the scope of the policy, with requirements for timely responses and procedures for appealing adverse decisions.

“The Committee believes that all IC personnel must be made aware of pre-publication review requirements and that the review process must yield timely, reasoned, and impartial decisions that are subject to appeal. The Committee also believes that efficiencies can be identified by limiting the information subject to pre-publication review, to the fullest extent possible, to only those materials that might reasonably contain or be derived from classified information obtained during the course of an individual’s association with the IC. In short, the pre-publication review process should be improved to better incentivize compliance and to deter personnel from violating their commitments,” the Committee wrote in its report on the FY 2017 intelligence authorization act.

Until the new IC-wide policy is promulgated, current and former ODNI employees must comply with ODNI’s existing pre-publication review policy, last revised in 2014.

“Correct unclassified sourcing is critical in executing pre-publication review,” that 2014 policy states. “ODNI personnel must not use sourcing that comes from known leaks, or unauthorized disclosures of sensitive information. The use of such information in a publication can confirm the validity of an unauthorized disclosure and cause further harm to national security. ODNI personnel are not authorized to use anonymous sourcing.”

Other intelligence agency personnel are subject to the rules issued by their respective agencies.

DNI Orders Security Clearance “Reciprocity”

One of the most vexatious aspects of the system of granting security clearances for access to classified information has been the reluctance of some government agencies to recognize the validity of clearances approved by other agencies, and to require new investigations and adjudications of previously cleared personnel.

A new directive from the Director of National Intelligence seeks to finally resolve this longstanding problem by mandating “reciprocity,” or mutual acceptance of security clearances issued by other agencies. See Reciprocity of Background Investigations and National Security Adjudications, Security Executive Agent Directive 7, November 9, 2018.

With certain exceptions, “Agencies shall accept national security eligibility adjudications conducted by an authorized adjudicative agency at the same or higher level,” DNI Daniel R. Coats wrote.

“Background investigations and national security eligibility adjudications, conducted by an authorized investigative agency or authorized adjudicative agency, respectively, shall be reciprocally accepted for all covered individuals,” again with certain exceptions.

In most cases, cleared personnel would not be required to fill out a new security clearance questionnaire or to undergo a new background investigation in order for their clearances to be recognized and accepted by another agency.

(Reciprocity refers to mutual recognition by agencies of an individual’s eligibility for access to classified information. Whether the individual also has the requisite “need to know” the information requires a separate determination.)

Security clearance reciprocity is an elusive policy goal that has been pursued since the Clinton Administration, if not longer.

A 2004 study by the Defense Personnel Research Center investigated the failure to fully implement reciprocity at that time and attributed it to issues of “turf and trust.”

“Virtually all respondents agreed that beneath the lack of complete reciprocity there is a certain lack of trust based on fear.” See Security Clearance Reciprocity: A Progress Report, PERSEREC, April 2004.

A new bill introduced by Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA) would require reporting on the number of individuals whose clearances take more than 2 weeks to be reciprocally recognized after they move to a new agency or department. See “Vice Chairman Warner Introduces Legislation to Revamp Security Clearance Process,” news release, December 6.

An X reveals a Diamond: locating Israeli Patriot batteries using radar interference

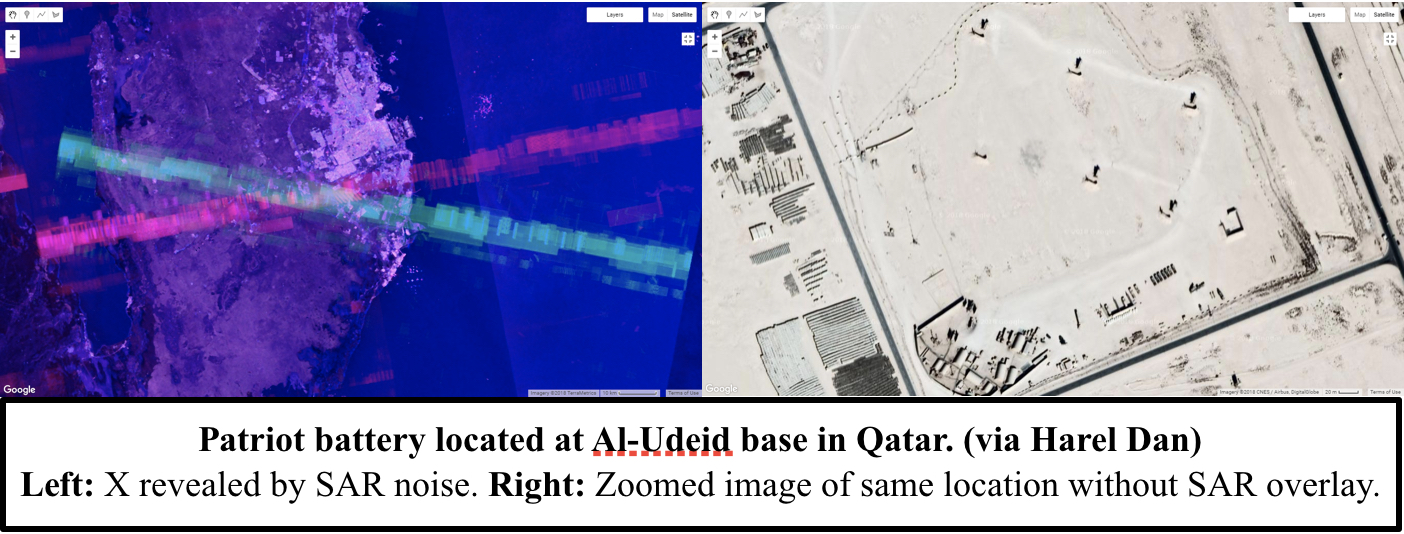

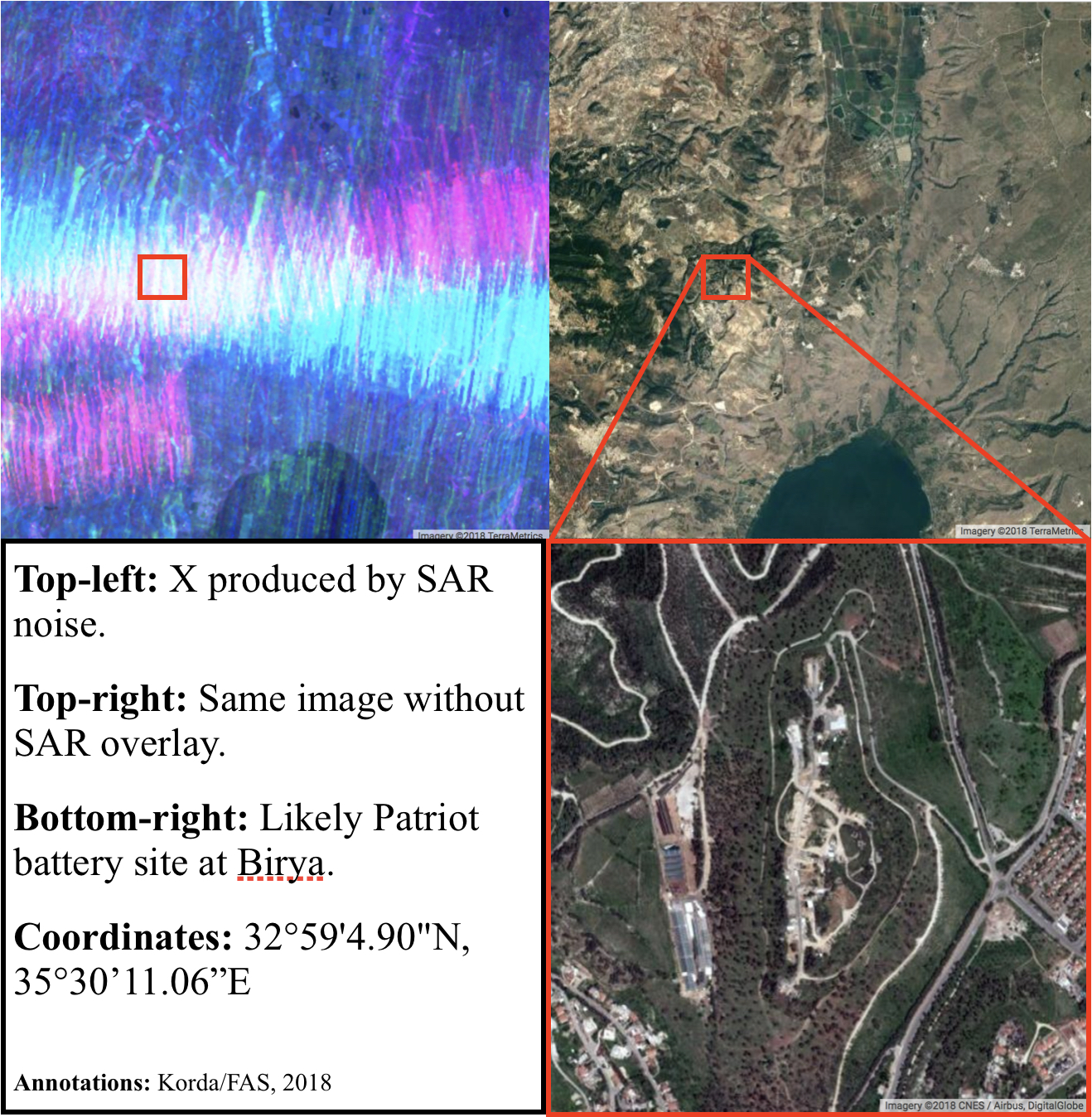

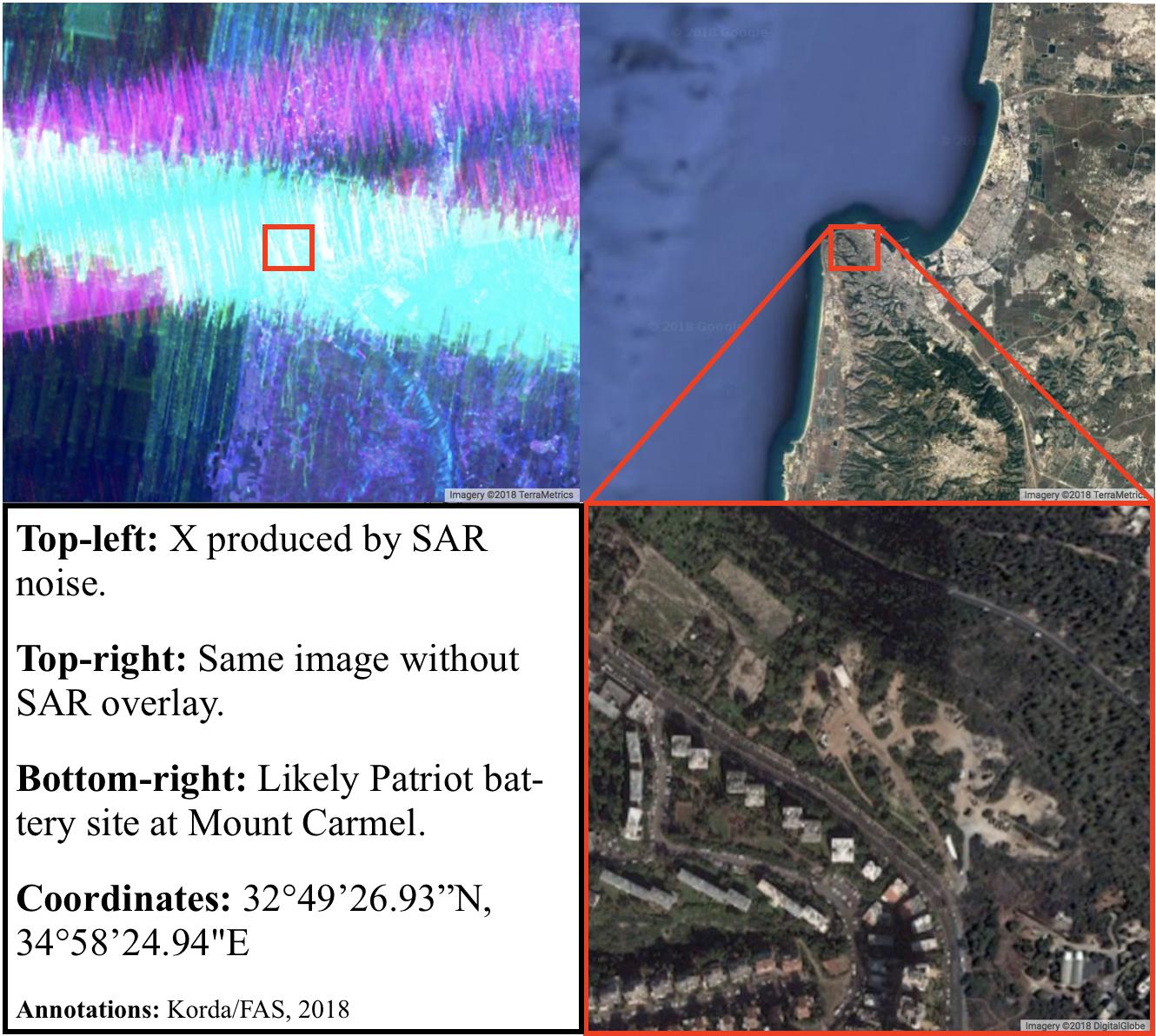

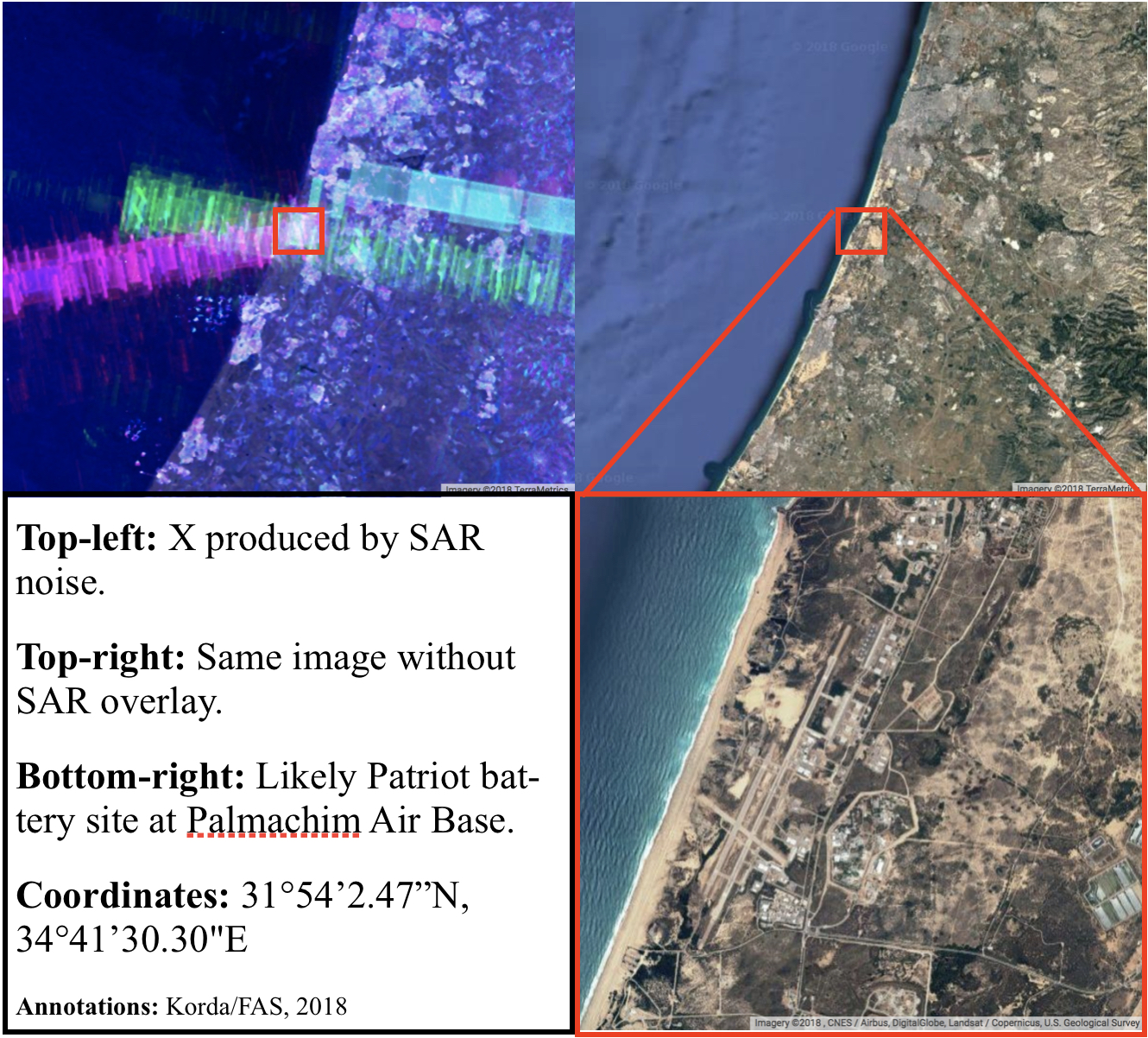

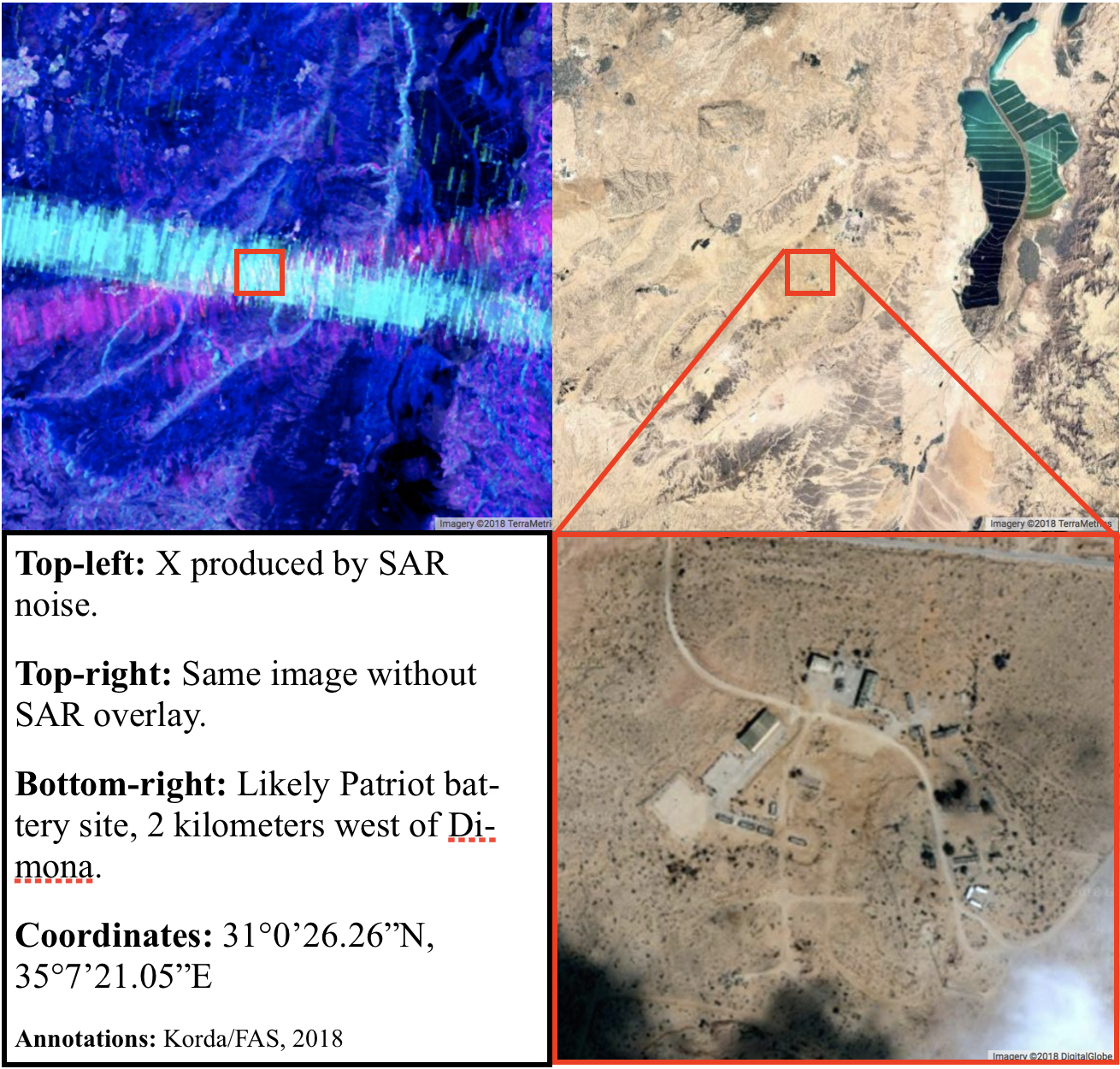

Amid a busy few weeks of nuclear-related news, an Israeli researcher made a very surprising OSINT discovery that flew somewhat under the radar. As explained in a Medium article, Israeli GIS analyst Harel Dan noticed that when he accidentally adjusted the noise levels of the imagery produced from the SENTINEL-1 satellite constellation, a bunch of colored Xs suddenly appeared all over the globe.

SENTINEL-1’s C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) operates at a centre frequency of 5.405 GHz, which conveniently sits within the range of the military frequency used for land, airborne, and naval radar systems (5.250-5.850 GHz)—including the AN/MPQ-53/65 phased array radars that form the backbone of a Patriot battery’s command and control system. Therefore, Harel correctly hypothesized that some of the Xs that appeared in the SENTINEL-1 images could be triggered by interference from Patriot radar systems.

Using this logic, he was able to use the Xs to pinpoint the locations of Patriot batteries in several Middle Eastern countries, including Qatar, Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia.

Harel’s blog post also noted that several Xs appeared within Israeli territory; however, the corresponding image was redacted (I’ll leave you to guess why), leaving a gap in his survey of Patriot batteries stationed in the Middle East.

This blog post partially fills that gap, while acknowledging that there are some known Patriot sites—both in Israel and elsewhere around the globe—that interestingly don’t produce an X via the SAR imagery.

All of these sites were already known to Israel-watchers and many have appeared in news articles, making Harel’s redaction somewhat unnecessary—especially since the images reveal nothing about operational status or system capabilities.

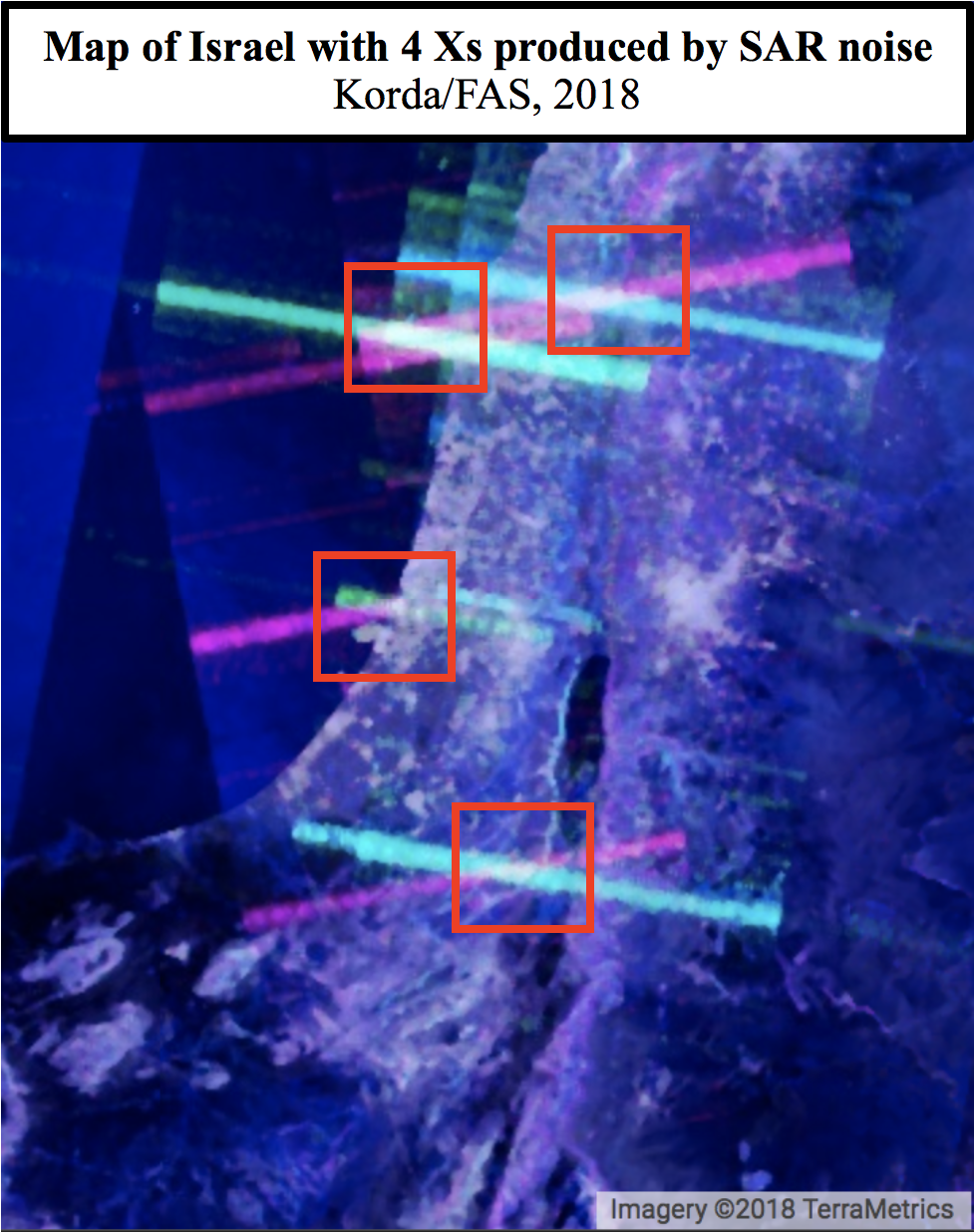

Looking at the map of Israel through the SENTINEL-1 SAR images, four Xs are clearly visible: one in the Upper Galilee, one in Haifa, one near Tel Aviv, and one in the Negev. All of these Xs correspond to likely Patriot battery sites, which are known in Israel as “Yahalom” (יהלום, meaning “Diamond”) batteries. Let’s go from north to south.

The northernmost site is home to the 138th Battalion’s Yahalom battery at Birya, which made news in July 2018 for successfully intercepting a Syrian Su-24 jet which had reportedly infiltrated two kilometers into Israeli airspace before being shot down. Earlier that month, the Birya battery also successfully intercepted a Syrian UAV which had flown 10 kilometers into Israeli airspace.

The Yahalom battery in the northwest is based on one of the ridges of Mount Carmel, near Haifa’s Stella Maris Monastery. It is located only 50 meters from a residential neighborhood, which has understandably triggered some resentment from nearby residents who have complained that too much ammunition is stored there and that the air sirens are too loud.

The X in the west indicates the location of a Yahalom site at Palmachim air base, south of Tel Aviv, where Israel conducts its missile and satellite launches. In March 2016, the Israeli Air Force launched interceptors as part of a pre-planned missile defense drill, and while the government refused to divulge the location of the battery, an Israeli TV channel reported that the drill was conducted using Patriot missiles fired from Palmachim air base.

Finally, the X in the southeast sits right on top of the Negev Nuclear Research Centre, more commonly known as Dimona. This is the primary facility relating to Israel’s nuclear weapons program and is responsible for plutonium and tritium production. The site is known to be heavily fortified; during the Six Day War, an Israeli fighter jet that had accidentally flown into Dimona’s airspace was shot down by Israeli air defenses and the pilot was killed.

The proximity of the Negev air defense battery to an Israeli nuclear facility is not unique. In fact, the 2002 SIPRI Yearbook suggests that several of the Yahalom batteries identified through SENTINEL-1 SAR imagery are either co-located with or located close to facilities related to Israel’s nuclear weapons program. The Palmachim site is near the Soreq Centre, which is responsible for nuclear weapons research and design, and the Mount Carmel site is near the Yodefat Rafael facility in Haifa—which is associated with the production of Jericho missiles and the assembly of nuclear weapons—and near the base for Israel’s Dolphin-class submarines, which are rumored to be nuclear-capable.

Google Earth’s images of Israel have been intentionally blurred since 1997, due to a US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment which prohibits US satellite imagery companies from selling pictures that are “no more detailed or precise than satellite imagery of Israel that is available from commercial sources.” As a result, it is not easy to locate the exact position of the Yahalom batteries; for example, given the number of facilities and the quality of the imagery, the site at Palmachim is particularly challenging to spot.

However, this law is actually being revisited this year and could soon be overturned, which would be a massive boon for Israel-watchers. Until that happens though, Israel will remain blurry and difficult to analyze, making creative OSINT techniques like Harel’s all the more useful.

—–

Sentinel-1 data from 2014 onwards is free to access via Google Earth Engine here, and Harel’s dataset is available here.

Aircraft Interdiction Nets Colombian Cocaine

With the support of U.S. intelligence, the Colombian Air Force last year engaged dozens of aircraft suspected of illicit drug trafficking, leading to the seizure of 4.4 metric tons of cocaine.

In 2017, “Colombia, with the assistance of the United States, responded to 80 unknown assumed suspect (UAS) air tracks throughout Colombia and the central/western Caribbean,” according to the latest annual report on the program. The report does not say how many of the aircraft were actually interdicted or fired upon. There were also 139 aircraft that were grounded by Colombian law enforcement agencies.

See Annual Report of Interdiction of Aircraft Engaged in Illicit Drug Trafficking (2017), State Department report to Congress, January 2018 (released under FOIA, October 2018).

The joint US-Colombia effort dates back at least to a 2003 Air Bridge Denial program involving detection, monitoring, interception, and interdiction of suspect aircraft.

The basic procedures for intercepting, warning, and attacking a suspect aircraft were more fully described in a 2010 version of the annual report. At that time, Brazil was also part of the Air Bridge Denial program.

US support for the Colombia aircraft interdiction program — which includes providing intelligence and radar information, as well as personnel training — was renewed by the President in a July 20, 2018 determination.

Intelligence Support to Diplomatic Facilities Abroad

The role of U.S. intelligence agencies in helping to protect U.S. diplomatic facilities and personnel abroad is highlighted in a recently revised Intelligence Community Directive.

The directive does not specifically cite the reported sonic attacks on the U.S. Embassy in Havana, but those mysterious events seem to fall within its scope, which include implementing Technical Surveillance Countermeasures (TSCM) and TEMPEST programs (shielding electromagnetic emissions and preventing penetrations).

See Counterintelligence and Security Support to U.S. Diplomatic Facilities Abroad, Intelligence Community Directive 707, amended August 21, 2018.

Army Needs Intelligence to Face “Peer Threats”

U.S. Army operations increasingly depend on intelligence to help confront adversaries who are themselves highly competent, the Army said this week in a newly updated publication on military intelligence.

Future operations “will occur in complex operational environments against capable peer threats, who most likely will start from positions of relative advantage. U.S. forces will require effective intelligence to prevail during these operations.” See Intelligence, Army Doctrine Publication 2-0, September 4, 2018.

The quality of U.S. military intelligence is not something that can be taken for granted, the Army document said.

“Despite a thorough understanding of intelligence fundamentals and a proficient staff, an effective intelligence effort is not assured. Large-scale combat operations are characterized by complexity, chaos, fear, violence, fatigue, and uncertainty. The fluid and chaotic nature of large-scale combat operations causes the greatest degree of fog, friction, and stress on the intelligence warfighting function,” the documentsaid.

“Intelligence is never perfect, information collection is never easy, and a single collection capability is never persistent and accurate enough to provide all of the answers.”

The Army document provides a conceptual framework for integrating intelligence into Army operations. It updates a prior version from 2012 which did not admit the existence of “peer” adversaries and did not mention the word “cyberspace.”

Some other recent U.S. military doctrine publications include the following.

Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, updated August 2018

Foreign Internal Defense, Joint Publication 3-22, August 17, 2018

Integrated DoD Intelligence Priorities, Directive-Type Memorandum (DTM) 15-004, September 3, 2015, Incorporating Change 2, Effective September 4, 2018

Aircraft and ICBM Nuclear Operations, Air Force Instruction 13-520, 22 August 2018

Implementation of, and Compliance with, Arms Control Agreements, SecNav Instruction 5710.23D, August 28, 2018

Bid to Rectify the “Black Budget” Fails

The so-called “black” budget — which refers to classified government spending on military procurement, operations, and intelligence — is not merely secret. It is actually deceptive and misleading, since it produces a distortion in the amount and the presentation of the published budget.

The amount of money that is purportedly appropriated for the US Air Force, for example, does not all go to the Air Force, the Senate Armed Services Committee recently observed.

“Each year, a significant portion of the Air Force budget contains funds that are passed on to, and managed by, other organizations within the Department of Defense. This portion of the budget, called ‘pass-through,’ cannot be altered or managed by the Air Force. It resides within the Air Force budget for the purposes of the President’s budget request and apportionment, but is then transferred out of the Service’s control,” according to a Senate report on the 2019 defense bill (S.Rept. 115-262).

Although the report does not say so, the Air Force budget may also include pass-through funding for the Central Intelligence Agency, which of course is not even part of the Department of Defense, as well as for other non-Air Force intelligence functions.

“In fiscal year 2018, the Air Force pass-through budget amounted to approximately $22.0 billion, or just less than half of the total Air Force procurement budget. The committee believes that the current Air Force pass-through budgeting process provides a misleading picture of the Air Force’s actual investment budget.”

The Senate therefore recommended that such “pass-through” funds be removed from the Air Force budget and included in Defense-wide appropriations.

But in the House-Senate conference on the FY2019 defense bill, this move was blocked and so the deceptive status quo will continue to prevail.

Earlier this month, the Director of National Intelligence and the Pentagon Comptroller wrote to Congress to present their views on the Senate provision. A copy of their letter, which presumably objected to the proposed move, has been requested but not yet released.

The logic of the Senate proposal was explained by Mackenzie Eaglen of the American Enterprise Institute in “Time to Get the Black Out of the Blue,” Real Clear Defense, June 13.

SSCI Requires Strategy for Countering Russia

In its new report on the FY 18-19 Intelligence Authorization bill, published today, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence would require the Director of National Intelligence “to develop a whole-of-government strategy for countering Russian cyber threats against United States electoral systems and processes.”

As if to underscore the gulf in the perception of the Russian threat that separates President Trump and the US intelligence community, the Senate Intelligence Committee comes down firmly on the side of the latter, taking “Russian efforts to interfere with the 2016 United States presidential election” as a given and an established fact.

The Senate report describes numerous other provisions of interest on election security, classification policy, cybersecurity, and more.

The House Intelligence Committee published its report on the pending FY18-19 intelligence authorization bill earlier this month.