Moving the Nation: The Role of Federal Policy in Promoting Physical Activity

Physical activity is one of the most powerful tools for promoting health and wellbeing. Movement is not only medicine—effective at treating a range of physical and mental health conditions—but it is also preventive medicine, because movement reduces the risk for many conditions ranging from cancer and heart disease to depression and Alzheimer’s disease. But rates of physical inactivity and sedentary behavior have remained high in the U.S. and worldwide for decades.

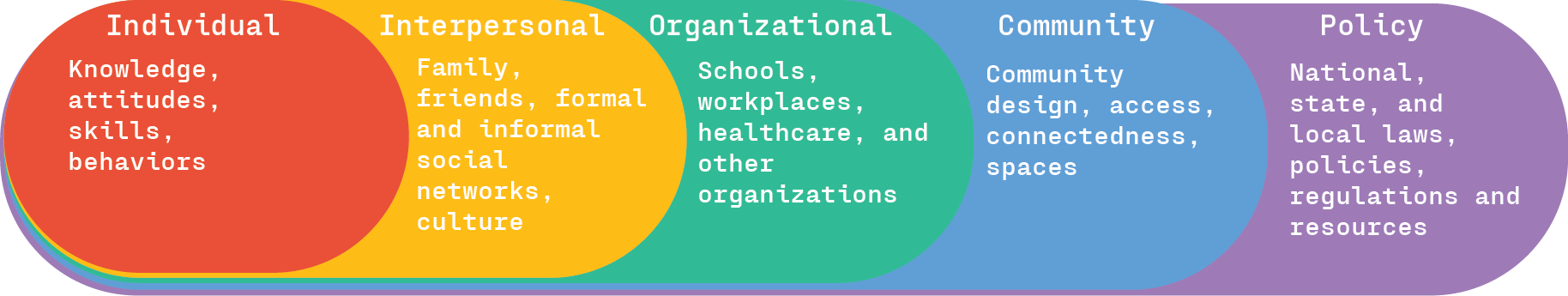

Engagement in physical activity is impacted by myriad factors that can be viewed from a social ecological perspective. This model views health and health behavior within the context of a complex interplay between different levels of influence, including individual, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy levels. When it comes to healthy behavior such as physical activity, sustainable change is considered most likely when these levels of influence are aligned to support change. Every level of influence on physical activity within a social-ecological framework is directly or indirectly affected by federal policy, suggesting physical activity policy has the potential to bring about substantial changes in the physical activity habits of Americans.

Why are federal physical activity policies needed?

Physical inactivity is recognized as a public health issue, having widespread impacts on health, longevity, and even the economy. Similar to other public health issues over past decades such as sanitation and tobacco use, federal policies may be the best way to coordinate large-scale changes involving cooperation between diverse sectors, including health care, transportation, environment, education, workplace, and urban planning. An active society requires the infrastructure, environment, and resources that promote physical activity. Federal policies can meet those needs by improving access, providing funding, establishing regulations, and developing programs to empower all Americans to move more. Policies also play an important role in removing barriers to physical activity, such as financial constraints and lack of safe spaces to move, that contribute to health disparities. With such a variety of factors impacting active lifestyles, physical activity policies must have inter-agency involvement to be effective.

What physical activity initiatives exist currently?

Analysis of publicly available information revealed that there are a variety of initiatives currently in place at the federal level, across several departments and agencies, aimed at increasing physical activity levels in the U.S. Information about each initiative was evaluated for their correspondence with levels of the social-ecological model, as summarized in the table. Note that it is possible the search that was conducted did not identify every relevant effort, thus there could be additional initiatives that are not included below.

Given the large number of groups with the shared goal of increasing physical activity in the nation, a memorandum of understanding (MOU) may help to promote coordination of goals and implementation strategies.

These and other federal departments and agencies can coordinate action with state and local partners, for example in healthcare, business and industry, education, mass media, and faith-based settings, to implement physical activity policies.

The CDC’s Active People, Healthy Nation initiative provides an example of this approach. This campaign, launched in 2020, has the goal of helping 27 million Americans become more physically active by 2027. By taking action steps focused on program delivery, partnership engagement, communication, training, and continuous monitoring and evaluation, the campaign seeks to help communities implement evidence-based strategies across sectors and settings to provide equitable and inclusive access to safe spaces for physical activity. According to our analysis, the strategies of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative are aligned with the social-ecological model. The Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network, a research partner of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative, provides an example of coordinating with partners in other sectors to promote physical activity. Through collaboration across sectors, the network brings together diverse partners to put into practice research on environments that maximize physical activity. The network includes work groups focused on equity and inclusion, parks and green space, rural active living, school wellness, transportation policy and planning, and business/industry.

The Biden-Harris Administration National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health, announced in September 2022, also includes strategies that are consistent with a social-ecological model. The strategy outlines steps toward the goal of ending hunger and increasing healthy eating and physical activity by 2030 so that fewer Americans will experience diet-related diseases. Pillar 4 of the strategy is to “make it easier for people to be more physically active—in part by ensuring that everyone has access to safe places to be active—increase awareness of the benefits of physical activity, and conduct research on and measure physical activity.” The strategy specifies goals such as building environments that promote physical activity (e.g., connecting people to parks; promoting active transportation and land use policies to support physical activity) and includes a call to action for a whole-of-society response involving the private sector, state, local, and territory governments, schools, and workplaces.

The Congressional Physical Activity Caucus has been active in introducing legislation that can help realize the goals of the current physical activity initiatives. For example, in February 2023, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH), co-chair of the Caucus, introduced the Promoting Physical Activity for Americans Act, a bill that would require the Department of Health and Human Services to continue issuing evidence-based physical-activity guidelines and detailed reports at least every 10 years, including recommendations for population subgroups (e.g., children or individuals with disabilities). In addition, members of the Caucus, along with other members of congress, reintroduced the bipartisan, bicameral Personal Health Investment Today (PHIT) Act in March 2023. This legislation seeks to encourage physical activity by allowing Americans to use a portion of the money saved in their pre-tax health savings account (HSA) and flexible spending account (FSA) toward qualified sports and fitness purchases, such as gym memberships, fitness equipment, physical exercise or activity programs and youth sports league fees. The bill would also allow a medical care tax deduction for up to $1,000 ($2,000 for a joint return or a head of household) of qualified sports and fitness expenses per year.

What progress has been made?

There are signs that some of the national campaigns are leading to changes at other levels of society. For example, 46 cities, towns, and states have passed an Active People, Healthy Nation Proclamation as of September 2023. According to the State Routes Partnership, which develops “report cards” for states based on their policies supporting walking, bicycling, and active kids and communities, many states have shown movement in their policies between 2020 and 2022, such as implementing new policies to support walking and biking and increasing state funding for active transportation. However, more time is needed to determine the extent to which recent initiatives are helping to create a more active country, since most were initiated in the past two or three years. Predating the current initiatives, the overall physical activity level of Americans increased from 2008 to 2018, but there has been little change since that time, and only about one-quarter of adults meet the physical activity guidelines established by the CDC.

Clearly, there is a critical need for concerted effort to implement the strategies outlined in current physical activity initiatives so that national policies have the intended impacts on communities and on individuals. Leveraging provisions in existing legislation related to the social-ecological model of physical activity promotion will also help with implementation. For example, title III-D of the Older Americans Act supports healthy lifestyles and promotes healthy behaviors amongst older adults (age 60 and older), providing funding for evidence-based programs that have been proven to improve health and well-being and reduce disease and injury. Physical activity programs are prime candidates for such funding. In addition, programs under the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act are helping to change the current car-dependent transportation network, providing healthier and more sustainable transportation options, including walking, biking, and using public transportation, and are providing investments in environmental programs to improve public health and reduce pollution. For example, states can use funds from the Highway Safety Improvement Program for bicycle and pedestrian highway safety improvement projects, and funding is available through the Carbon Reduction Program for programs that help reduce dependence on single-occupancy vehicles, such as public transportation projects and the construction, planning, and design of facilities for pedestrians, bicyclists, and other non-motorized forms of transportation.

Partnering with non-governmental groups working towards common goals, such as the Physical Activity Alliance, can also help with implementation. The Alliance’s National Physical Activity Plan is based on the socio-ecological model and includes recommendations for evidence-based actions for 10 societal sectors at the national, state, local and institutional levels, with a focus on making change at the community level. The plan shares many priorities with those of the Active People, Healthy Nation initiative, while also introducing new goals, such as establishing a CDC Office of Physical Activity and Health.

With coordinated action based on established public health models, such as the social-ecological framework, federal policies can be successfully implemented to make the systemic changes that are needed to create a more active nation.

The work for this blog was undertaken before Dr. Dotson joined the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Dr. Dotson is solely responsible for this blog post’s contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement as an official position of AHRQ or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Putting the fun in fundamental: how playful learning improves children’s outcomes

When we think back to our childhoods, many of us have fond memories of play. Playing outside, playing at school, or playing with friends and siblings often trump memories of worksheets and teacher lectures. Why is that?

Children are born ready to play and explore the world around them. First games of peek-a-boo with a loving caregiver provide an infant with learning and engagement— the infant develops a positive relationship with a caregiver, begins to develop object permanence, and experiences call and response social interactions – all critical steps in a child’s development.

According to the National Association of the Education of Young Children, play is a critical component of early childhood and children’s physical, social, and emotional development. Children learn best when they are doing. Playful learning includes opportunities for free play directed by the children themselves and guided play, designed by a teacher to provide children access to specific materials, concepts and guidance through hands-on engagement. These opportunities allow children to explore, expand their knowledge, take risks, develop interests, and practice their social and emotional skills.

Through play, many children are able to demonstrate their knowledge and learning that they otherwise are unable to share on a worksheet or assessment. For teachers, play provides a window into a child’s world that is not easily accessed through paper and pencil. Early childhood and early elementary programs have a critical opportunity to impact a child’s long term development by providing developmentally appropriate playful learning experiences to all children.

Playful Learning Promotes Child (and Adult) Well-being at a Critical Time

According to the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University, play can help young children develop resilience and navigate significant adversity. When young children experience playful learning, they benefit from enhanced problem solving, communication, decision-making and creative skills. Teachers and caregivers who encourage play and exploration establish positive relationships. Through this,children develop positive self-esteem and approaches to learning that can carry them for many years. All of these skills are not only critical now, but will increasingly be more important as the next generation moves forward into the future.

Unfortunately, play has become less valued over the last decade or so as school systems have put emphasis on scholastic curricula. We know that kindergarten classrooms are by and large offering less play time and more academic curriculum. Preschool programs are feeling the pressure of getting children “ready for school.” However, our children are experiencing unprecedented stress due to the pandemic, community violence and general unrest in the world. In addition, evidence suggests that children have experienced learning and development loss due to the pandemic. Now more than ever is the time to ensure they are getting what they need through playful learning.

Teachers working with our youngest children are also facing significant challenges as children and families return to the new normal of school on top of their own personal stressors. According to EducationWeek, many teachers continue to report high levels of stress and anxiety as a result of working through and post-pandemic. Teachers are not only continuing to manage virus exposure but are expected to address learning loss of their students, navigate mental health needs while all the while meeting increasingly more rigorous standards during a teacher shortage. Could “allowing” teachers to do what’s best for children and utilize playful learning as a primary strategy not only support children through this trying time but also provide a more relaxed supportive environment for teachers as well? Rather than spending time copying worksheets, conducting testing and focusing on rote memorization, play would be beneficial for teachers and children alike.

In the United States, play is often considered a four letter word mistakenly associated with less academic instruction and ultimately, lower test scores. However, the tide is changing as more and more communities both in the U.S. and abroad begin to recognize that both free and guided play in early childhood can provide children important opportunities for learning, growth and ultimately success in school and life.

Three Lessons from Quality, Play-based Early Learning Programs

Educators and policymakers alike can learn a lot from other countries’ experiences developing quality, play-based early childhood programs. There have been great strides in adopting playful learning — even in low-resource contexts and in school systems where primary schooling tends to follow more traditional teacher-led approaches. Here are three examples of how play has contributed to quality early learning outside the U.S. to show what might be possible.

Playful learning is key to quality early child education: Lively Minds in Ghana

While Ghana introduced two years of kindergarten for four- and five-year olds as part of the universal basic education system in 2007, many schools faced difficulties training and retaining teachers. Large class sizes, limited play and learning materials, and rote teaching approaches are common in preschools. In response to these challenges, Lively Minds, an NGO, developed community-led, play-based early learning programs, known as “Play Schemes” in schools. In partnership with the Ghana Education Service, Lively Minds trained two kindergarten teachers from each participating school who then trained 30-40 mothers to be play scheme facilitators. Four days a week, volunteer mothers run play stations with small groups of children focused on: counting; matching; shapes and senses; books; and building. Parents also participate in monthly workshops to learn to support their children’s health, development, and learning at home.

The program is delivered within the existing government system to promote sustainability. Government and Lively Minds staff jointly monitor the implementation of the play schemes. A randomized control trial in rural Ghana found that Lively Minds significantly improved children’s emerging literacy, executive functioning, and fine motor skills. Children from poorer households benefited more from the program; emergent literacy skills also improved in this group of children. Participating children’s socio-emotional development improved as conduct problems and hyperactive behaviors decreased. Acute malnutrition decreased by a remarkable 22% among children attending Play Schemes. Volunteer mothers improved their self-esteem and mental health as well as their knowledge about child development. They also spent more time on developmentally appropriate activities with their children at home.

Currently, the Ghanaian government is rolling out Lively Minds in 60 of the country’s 228 districts, reaching approximately 4,000 preschool classrooms and more than 1.3 million young children. A new study will evaluate the program’s effectiveness at scale.

Increasing equity through play: Play Labs in Bangladesh

The second example comes from Bangladesh, where the development organization BRAC created the Play Lab model, a low-cost, non-formal approach to play-based learning for children ages 3-5. These vibrant, child-friendly spaces follow a play-based curriculum and use low-cost recycled materials. Play Leaders, young women selected from the community, give young children space and time to explore their own interests and ideas. Play Leaders also engage young children in culturally-relevant rhymes, stories, and dancing to encourage joy-filled learning. Since 2015, Play Labs have reached over 115,000 children in local communities, government schools, and refugee camps in Bangladesh, Tanzania, and Uganda.

A quasi-experimental evaluation in 2018-2019 in Bangladesh found that the Play Labs improved children’s development across physical, cognitive, and socio-emotional domains. In fact, after two years in the Play Labs, children who scored below average at baseline were able to catch up to their peers who entered with the highest scores; no such pattern was found in the control group. By reducing these initial gaps among children, Play Labs helped improve equity and promote school readiness for very disadvantaged young children. Play Leaders not only increased their early childhood knowledge and skills, but also the quality of their interactions with children.

Reaching children experiencing crisis and conflict: Remote early childhood education program in Lebanon

In Lebanon, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) worked with Sesame Workshop to implement an 11-week Remote Early Learning Program for families affected by conflict and crisis. The curriculum focuses on social and emotional learning and school readiness skills and targets mostly (96%) Syrian caregivers with 5-6 year old children living in hard-to-access areas of Lebanon, where exposure to preschool is very limited. As with quality, in-person early childhood education, the remote program focuses on engaging children through hands-on and play-based activities. Participating families receive supplies and worksheets to use in the activities with their children. Teachers use WhatsApp to call groups of parents and send multimedia content (e.g., videos, storybooks, songs) 2-3 times a week. The first five minutes of the call involve the child to help foster their connections with the teacher, while the remainder of time engages the parent on how early childhood activities support children’s development and learning.

A 2022 study compared the impact of the Remote Early Learning Program (RELP) alone and in combination with a remote parent support program that focuses more broadly on early childhood development. Both forms of the intervention had significant, positive effects on child development and child play compared to the control group. The authors remark that: “The size of the impacts found on child development is in the range of those seen in evaluations of in-person preschool from around the world, suggesting that RELP is a viable alternative to support children in places where in-person preschool is not feasible.”

Enabling Play-Based Policies in the U.S. are Needed

While these different modalities – home-based, center-based, remote learning – are promising approaches to support young children’s learning through play, they will not be implemented or scaled in the United States without an enabling policy environment. This means playful learning should be included in policy documents, legislation, standards, and curricula. It should also be supported by committing adequate financial resources for teachers to create playful learning environments and opportunities.

We’re seeing this happen in countries that are known for their high scores on international assessments, but less for their child-centered approaches in the early years. For example, in 2019, South Korea introduced a revised curriculum for 3 to 5 year olds that is organized around learning domains instead of by age. The goal is to shift from an academic approach to early childhood education to one that is more child-focused and play-based.

In 2012, Singapore revamped its Nurturing Early Learners curriculum for children ages 4 to 6 with a key objective being “To give every child a good start, preschool education nurtures the joy of learning and children’s holistic development.” To support implementation, the government developed educators’ guides and teaching and learning resources. Coincidentally, or not, Singapore ranks 4th in the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS), an international comparative assessment that evaluates reading literacy at grade 4.

One of the more comprehensive approaches comes from Rwanda, which recently revised its curriculum for pre-primary education through upper secondary grades. The competency-based curriculum recognizes the importance of play-based learning to reach intended learning outcomes across ages. The Ministry of Education is now working with partners to develop a national strategy to institutionalize learning through play into teacher training and pedagogical practices. In addition to pre-service and in-service training, components will include appropriate learning materials, assessments, quality assurance mechanisms, monitoring and evaluation, and advocacy to roll out learning through play within the education system.

Five Ways Policymakers Can Introduce Playful Learning into any Education Model Today

We know why playful learning is important. We can take inspiration from successful programs in some of the most vulnerable contexts. It’s time for policy makers in the U.S. to take steps to make learning through play a reality for our youngest learners:

- Include playful learning in policy documents including those related to standards and curriculum

- Prioritize funding for high quality developmentally appropriate playful learning in Pre-3

- Focus on preparing and supporting teachers to create playful learning environments along the P-3 continuum

- Support family members to integrate play into everyday activities with their children

- Use appropriate technology to complement in-class activities or to reach those who do not have access to early childhood education

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.

Healthy Kids, High Grades: Using Data to Evaluate Health and Education Policy

It’s back-to-school time! As kids from across the country get back into classrooms this fall, many of them, at least in Colorado and Minnesota, will be attending a school that will offer free meals to all students through new state programs that voters approved last year. That’s good news for individual students and their classrooms. This post will look at why.

Using innovative data linkages and analysis, research finds that these policies, in combination with other school- and broad-based health policies, effectively enhance not just children’s health and wellbeing but also their reading, math, and classroom behavior. Moreover, the health policy effects on educational outcomes are comparable to a $1,000 increase in per-pupil spending.

Examining the Education Effects of Health Policies

A recent study systematically reviewed and synthesized results from 56 studies to evaluate the causal impact of various health policies targeting school-aged children and their parents on children’s education in the U.S. (Disclosure: this was my study, in conjunction with a graduate student.) We found that several health policies and programs aimed at improving the physical health of children and parents, particularly from low-income households, have positive effects on educational attainment.

For example, nutritional policies in schools, similar to the “Health School Meals for All” program started in Colorado this year, builds on empirical evidence from similar initiatives rolled out by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) in select districts across the country through a program called the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP). Careful empirical analysis found that the CEP, which was designed to universalize the access to healthy school meals in high poverty school districts, improved children’s math scores (albeit primarily in schools serving the most vulnerable kids from low-income households). Similarly, researchers also found that this policy reduced adverse school disciplinary outcomes—such as suspensions and expulsions across several parts of the country, particularly for children from low-income households.

Reducing Hunger Improves Performance in School

Food insecurity affected nearly 10 million children in 2019 according to estimates from the USDA. This situation increased during the height of the pandemic despite stop-gap arrangements such as the pandemic-EBT. Research has shown the deleterious effects of food insecurity on a whole host of learning and socioemotional outcomes for children. Some children end up eating their only meal in school. This makes school-based nutritional policies an important complement to other broad-based, nutritional policies—such as the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP). Studies find that at the end of the SNAP benefit cycle, students experience negative effects on their learning and behavior.

Children Lacking Health Insurance Struggle in School

With child poverty rising dramatically in recent weeks, it is hard not to stress the importance of access to subsidized, quality healthcare for our most vulnerable children. While past research clarified the beneficial effects of health insurance access—such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP)—on children’s health and wellbeing; more recently, researchers are uncovering the positive, educational effects from these policies as well. When parents gained access to Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act, the benefits transferred over to their children, too. Studies show these children improved their reading scores and reduced the stubborn white-Black math achievement gap, achievement differences in math standardized test scores between white and Black students.

How do these improvements compare to other educational policy reforms? Indeed, we find that these nutritional interventions, while modest in absolute terms, are roughly comparable to a $1,000 increase in per-pupil spending (annually over four years) in schools. Both sets of federal policies/programs (Medicaid/CHIP as well as per-pupil school funding increases) improve student test scores by about 0.04 standard deviations. Although such comparisons across models/policies is not often straightforward, nevertheless, these research findings provide suggestive evidence that targeted, health policy interventions can be quite effective in improving school-aged children’s educational outcomes.

Integrated Data Linkages Can Power Effective Health-Focused Learning Policies

One significant barrier to examining such cross-policy research and policymaking is the lack of high-quality, integrated data. While some states are beginning to develop robust databases that cover health and education outcomes, we have a long way to go. But, by creating data linkages, we can more quickly find and replicate solutions that support student outcomes.

There are a few such projects underway. For example, California’s “cradle-to-career” is an example of an excellent statewide, longitudinal data system, which plans to connect data on early education, K-12 schools, colleges, social/health services, and employment. Similarly, states like Minnesota, and Wisconsin have also invested in such administrative data linkages between birth records, child welfare, and education data systems.

Indeed, the Institute of Education Science’s (IES) statewide longitudinal database system program has expanded across the country and education sectors (e.g., P-20/workforce expansions) since 2019. However, modernization and expansions that prioritizes linkages with other key social innovation issues—such as health—through innovative data linkages between education and health and human services, vital statistics (birth records), Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMMS), and child welfare systems represents a huge opportunity.

We hope that such linked datasets will be opened to researchers and policymakers across the country, not least because such datasets have been integral for the development of this nascent literature. For example, one study that used such linked data from Florida to examine the negative effects of environmental pollution on children’s academic achievement. Similarly, another study used linked birth-records and education data to examine the effect of Medicaid access among low-income parents on their children’s reading outcomes in Iowa.

We always knew that healthy children do better in school—they pay better attention in class, disrupt less frequently, and learn better when they are healthy and happy. We now have rigorous empirical research to show the precise effects of such health policies on the most vulnerable children’s education. More parents, policymakers, and researchers will gain more knowledge at the health-education nexus when data is shared.

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.

It’s Time to Move Towards Movement as Medicine

For over 10 years, physical inactivity has been recognized as a global pandemic with widespread health, economic, and social impacts. Despite the wealth of research support for movement as medicine, financial and environmental barriers limit the implementation of physical activity intervention and prevention efforts. The need to translate research findings into policies that promote physical activity has never been higher, as the aging population in the U.S. and worldwide is expected to increase the prevalence of chronic medical conditions, many of which can be prevented or treated with physical activity. Action at the federal and local level is needed to promote health across the lifespan through movement.

Research Clearly Shows the Benefits of Movement for Health

Movement is one of the most important keys to health. Exercise benefits heart health and physical functioning, such as muscle strength, flexibility, and balance. But many people are unaware that physical activity is closely tied to the health conditions they fear most. Of the top five health conditions that people reported being afraid of in a recent survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the risk for four—cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, and stroke—is increased by physical inactivity. It’s not only physical health that is impacted by movement, but also mental health and other aspects of brain health. Research shows exercise is effective in treating and preventing mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety, rates of which have skyrocketed in recent years, now impacting nearly one-third of adults in the U.S. Physical fitness also directly impacts the brain itself, for example, by boosting its ability to regenerate after injury and improving memory and cognitive functioning. The scientific evidence is clear: Movement, whether through structured exercise or general physical activity in everyday life, has a major impact on the health of individuals and as a result, on the health of societies.

Movement Is Not Just about Weight, It’s about Overall Lifelong Health

There is increasing recognition that movement is important for more than weight loss, which was the primary focus in the past. Overall health and stress relief are often cited as motivations for exercise, in addition to weight loss and physical appearance. This shift in perspective reflects the growing scientific evidence that physical activity is essential for overall physical and mental health. Research also shows that physical activity is not only an important component of physical and mental health treatment, but it can also help prevent disease, injury, and disability and lower the risk for premature death. The focus on prevention is particularly important for conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia that have no known cure. A prevention mindset requires a lifespan perspective, as physical activity and other healthy lifestyle behaviors such as good nutrition earlier in life impact health later in life.

Despite the Research, Americans Are Not Moving Enough

Even with so much data linking movement to better health outcomes, the U.S. is part of what has been described as a global pandemic of physical inactivity. Results of a national survey by the CDC published in 2022 found that 25.3% of Americans reported that outside of their regular job, they had not participated in any physical activity in the previous month, such as walking, golfing, or gardening. Rates of physical inactivity were even higher in Black and Hispanic adults, at 30% and 32%, respectively. Another survey highlighted rural-urban differences in the number of Americans who meet CDC physical activity guidelines that recommend ≥ 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and ≥ 2 days per week of muscle-strengthening exercise. Respondents in large metropolitan areas were most active, yet only 27.8% met both aerobic and muscle strengthening guidelines. Even fewer people (16.1%) in non-metropolitan areas met the guidelines.

Why are so many Americans sedentary? The COVID-19 pandemic certainly exacerbated the problem; however, data from 2010 showed similar rates of physical inactivity, suggesting long-standing patterns of sedentary behavior in the country. Some of the barriers to physical activity are internal to the individual, such as lack of time, motivation, or energy. But other barriers are societal, at both the community and federal level. At the community level, barriers include transportation, affordability, lack of available programs, and limited access to high-quality facilities. Many of these barriers disproportionately impact communities of color and people with low income, who are more likely to live in environments that limit physical activity due to factors such as accessibility of parks, sidewalks, and recreation facilities; traffic; crime; and pollution. Action at the state and federal government level could address many of these environmental barriers, as well as financial barriers that limit access to exercise facilities and programs.

Physical Inactivity Takes a Toll on the Healthcare System and the Economy

Aside from a moral responsibility to promote the health of its citizens, the government has a financial stake in promoting movement in American society. According to recent analyses, inactive lifestyles cost the U.S. economy an estimated $28 billion each year due to medical expenses and lost productivity. Physical inactivity is directly related to the non-communicable diseases that place the highest burden on the economy, such as hypertension, heart disease, and obesity. In 2016, these types of modifiable risk factors comprised 27% of total healthcare spending. These costs are mostly driven by older adults, which highlights the increasing urgency to address physical inactivity as the population ages. Physical activity is also related to healthcare costs at an individual level, with savings ranging from 9-26.6% for physically active people, even after accounting for increased costs due to longevity and injuries related to physical activity. Analysis of 2012 data from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) found that each year, people who met World Health Organization aerobic exercise guidelines, which correspond with CDC guidelines, paid on average $2,500 less in healthcare expenses related to heart disease alone compared to people who did not meet the recommended activity levels. Changes are needed at the federal, state, and local level to promote movement as medicine. If changes are not made in physical activity patterns by 2030, it is estimated that an additional $301.8 billion of direct healthcare costs will be incurred.

Government Agencies Can Play a Role in Better Promoting Physical Activity Programs

Promoting physical activity in the community requires education, resources, and removal of barriers in order for programs to have a broad reach to all citizens, including communities that are disproportionately impacted by the pandemic of physical inactivity. Integrated efforts from multiple agencies within the federal government is essential.

Past initiatives have met with varying levels of success. For example, Let’s Move!, a campaign initiated by First Lady Michelle Obama in 2010, sought to address the problem of childhood obesity by increasing physical activity and healthy eating, among other strategies. The Food and Drug Administration, Department of Agriculture, Department of Health and Human Services including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Department of Interior were among the federal agencies that collaborated with state and local government, schools, advocacy groups, community-based organizations, and private sector companies. The program helped improve the healthy food landscape, increased opportunities for children to be more physically active, and supported healthier lifestyles at the community level. However, overall rates of childhood obesity remained constant or even increased in some age brackets since the program started, and there is no evidence of an overall increase in physical activity level in children and adolescents since that time.

More recently, the U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People 2030 campaign established data-driven national objectives to improve the health and well-being of Americans. The campaign was led by the Federal Interagency Workgroup, which includes representatives across several federal agencies including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the U.S. Department of Education. One of the campaign’s leading health indicators—a small subset of high-priority objectives—is increasing the number of adults who meet current minimum guidelines for aerobic physical activity and muscle-strengthening activity from 25.2% in 2020 to 29.7% by 2030. There are also movement-related objectives focused on children and adolescents as well as older adults, for example:

- Reducing the proportion of proportion of adults who do no physical activity in their free time

- Increasing the proportion of children, adolescents, and adults who do enough aerobic physical activity, muscle-strengthening activity, or both

- Increasing the proportion of child care centers where children aged 3 to 5 years do at least 60 minutes of physical activity a day

- Increasing the proportion of adolescents and adults who walk or bike to get places

- Increasing the proportion of children and adolescents who play sports

- Increasing the proportion of older adults with physical or cognitive health problems who get physical activity

- Increasing the proportion of worksites that offer an employee physical activity program

Unfortunately, there is currently no evidence of improvement in any of these objectives. All of the objectives related to physical activity with available follow-up data either show little or no detectable change, or they are getting worse.

To make progress towards the physical activity goals established by the Healthy People 2030 campaign, it will be important to identify where breakdowns in communication and implementation may have occurred, whether it be between federal agencies, between federal and local organizations, or between local organizations and citizens. Challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., less movement outside of the house for people who now work from home) will also need to be addressed, with the recognition that many of these challenges will likely persist for years to come. Critically, financial barriers should be reduced in a variety of ways, including more expansive coverage by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for exercise interventions as well as exercise for prevention. Policies that reflect a recognition of movement as medicine have the potential to improve the physical and mental health of Americans and address health inequities, all while boosting the health of the economy.

Kindergarten Needs a Revamp to Provide Better Learning Outcomes

In its early days, kindergarten was considered a radical approach to education. The foundation of the kindergarten curriculum included developmentally appropriate practice through hands-on engaging activities designed for the developmental stages of young children. Hands-on activities, play and socialization, or the ways children learn best, were the key strategies utilized to support children’s learning. Today, kindergarten is more closely associated with academics, worksheets, and learning to read as the pressure to meet certain standards is pushed down on our young children, their families and teachers. This shift has resulted in the more engaging hands on activities falling to the wayside.

One might assume that this more intensive introduction to public school would produce better long term results for our students. Why do it otherwise? However, most recent data from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) reports that the average reading scores for fourth graders in the U.S. was lower than the averages for 12 education systems across the world, many of whom wait until children are developmentally ready to read, closer to age 7, before beginning formal literacy instruction. If children are not faring as well as they progress through the grades as students in countries with less rigorous curricula in kindergarten, is our more intensive academic approach in the early years working? It is time to radicalize kindergarten again?

Kindergarten Today is More Advanced Than You Remember

According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard, emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar of brain architecture. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important for success in school, the workplace, and in the larger community. Children develop these important skills through positive relationships with caring adults, play-based, engaging activities, and opportunities to explore. In recent times, kindergarten classroom curriculum has shifted away from meeting the developmental needs and abilities of children instead following a highly academic one-size-fits-all approach to learning. Coincidentally, or not, the majority of teacher preparation programs in the United States do not require (or in some cases even offer) a course on child development or the science of learning in young children.

Today, kindergarten in the United States looks much more like first, second or even third grade yet, developmentally, our children remain the same.

According to a study conducted by the University of Virginia, between 1998 and 2006, kindergarteners were held to increasingly higher academic expectations both prior to and during kindergarten, including the expectation that parents would teach children all (presumably English) letters before entering school. Teachers reported dedicating more time to advanced literacy and math content, teacher-directed instruction, and assessment and substantially less time to art, music, science, and child-selected activities. This trend continues today.

While some states require 30 minutes of recess for kindergartners, other states do not, and have in some cases reduced outdoor play time to 15 minutes or less per day. According to Eric Jensen’s book Teaching With the Brain in Mind, “A short recess arouses students and may leave them ‘hyper’ and less able to concentrate.” Children benefit from an extended recess session (approximately an hour in length), because it gives their bodies time to regulate the movement and bring their activity level back down again.” Our kindergarteners are playing less and ‘studying’ more.

The Inequities of Kindergarten Have Lasting Consequences

Just as a child’s experience prior to entering the public school system may be different than the next child, once they enter kindergarten, their experience can vary greatly based on the state, district and community in which they live. According to the most recent 50 State Comparison: K-3 Policies released by the Education Commision of the States, every district in the country offers at least a part day kindergarten with 16 states requiring full day kindergarten. In some states, districts are required to offer over 1,000 hours of kindergarten instruction per school year whereas others require as few as 50 hours. Some kindergarten teachers have as many as 33 children alone in a kindergarten classroom while children in other states may be in a class with half as many children present. Six states do not require kindergarten attendance.

Since the pandemic, enrollment and attendance in kindergarten has declined across the country primarily in communities of color. Based on a report released by Attendance Works in 2011, we know that children with low or at-risk attendance in kindergarten and first grade were more likely to not reach grade level standards in third grade in English language arts and math. National estimates suggest that one in 10 kindergarten and first grade students misses 18 or more days of the school year, or nearly a month. More recent data suggests this rate is most likely higher. These missed days in the early years can add up to weaker reading skills, higher rates of retention and lower attendance rates in later grades.This is especially true for children from low-income families, who depend on school for literacy development. Students from lower performing schools and/or low income families were more likely to have attendance issues in the early years compared to their peers from higher performing schools.

Bridging the Gap

For many students, we know that kindergarten is their first experience in the public school system. While some may not start school until first grade, kindergarten is often the bridge from early experiences to the K-12 system. Children of color and/or those living in low income communities may face the perfect storm that challenges the integrity of the bridge that is kindergarten. For example, access to kindergarten may be limited, cultural and linguistic appropriateness may be absent, chronic health issues may impact attendance, and transportation may be challenging. For many working families, a half day kindergarten does not meet the family’s needs. Full day programs may be out of reach for families either because they are not offered or, they live within communities where the first half of kindergarten is free but the second half of the day is fee-based, excluding lower income families.

Based on 2021 U.S. Census Data, 14% of 5 year old children in the United States are not enrolled in school. This means we have over 150,000 potentially eligible children not enrolled in kindergarten. How will every child reach the Common Core standards for kindergarten if they are not in kindergarten? And even if they are present, are the standards being implemented equitably across the country? Are our kindergarteners experiencing the most appropriate learning possible?

In order to ensure all children are provided the same opportunities for growth and success, we must ensure that all schools are ready for all children. To do so, it is important we explore opportunities to:

- Develop and implement federal and state policies requiring kindergarten curricula based on the science of learning and child development while aligned to the Common Core standards

- Ensure consistent, appropriate teacher to child ratios and class sizes in every kindergarten classroom

- Provide and require professional development regarding child development and the science of learning for all kindergarten teachers and administrators

- Provide opportunities for free full day kindergarten in all communities

- Provide necessary transportation, health, and community services to kindergarteners and their families

- Expand research of kindergarten readiness, effectiveness of kindergarten curricula, and long term outcomes of kindergarten students

As kindergarten focuses on academic performance and excludes those without classroom or transportation access, we tip the scales further between the “haves” and “have nots” – at the risk to all students and American competitiveness. How a child is introduced to school and how a child is prepared for formal education has lasting effects. If the U.S. wants to develop a workforce ready to lead and compete globally we have to start at the very beginning of a student’s school experience. Kindergarten, once radical, today needs a radical reinvention that provides for today’s challenges and readies children for tomorrow.

Raise the Bar, Lead the World

Abigail Swisher, Rural Impact Fellow at FAS, served in the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. She was part of the team who developed the policy strategy, Raise the Bar, Lead the World.

We are pleased to announce the release of three new policy briefs from the U.S. Department of Education: Raising the Bar for Rural. These briefs outline key policy levers that state and local education leaders can use to make a difference on critical issues for rural students, as well as highlighting bright spots from rural communities nationwide. Organized around the Department’s Raise the Bar, Lead the World agenda, the briefs cover strategies to accelerate learning, end the educator shortage, increase access to comprehensive & rigorous coursework for all students.