Kindergarten, Once Radical, Needs a Revamp to Provide More Equitable Learning Outcomes

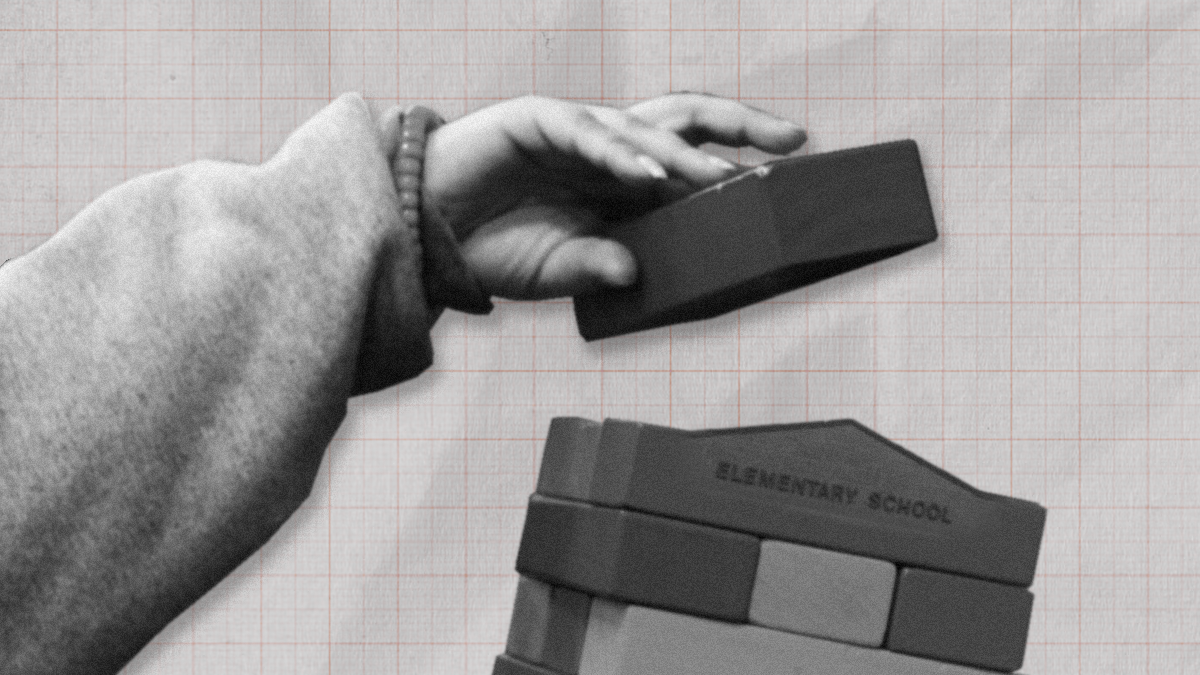

In its early days, kindergarten was considered a radical approach to education. The foundation of the kindergarten curriculum included developmentally appropriate practice through hands-on engaging activities designed for the developmental stages of young children. Hands-on activities, play and socialization, or the ways children learn best, were the key strategies utilized to support children’s learning. Today, kindergarten is more closely associated with academics, worksheets, and learning to read as the pressure to meet certain standards is pushed down on our young children, their families and teachers. This shift has resulted in the more engaging hands on activities falling to the wayside.

One might assume that this more intensive introduction to public school would produce better long term results for our students. Why do it otherwise? However, most recent data from the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) reports that the average reading scores for fourth graders in the U.S. was lower than the averages for 12 education systems across the world, many of whom wait until children are developmentally ready to read, closer to age 7, before beginning formal literacy instruction. If children are not faring as well as they progress through the grades as students in countries with less rigorous curricula in kindergarten, is our more intensive academic approach in the early years working? It is time to radicalize kindergarten again?

Kindergarten Today is More Advanced Than You Remember

According to the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard, emotional well-being and social competence provide a strong foundation for emerging cognitive abilities, and together they are the bricks and mortar of brain architecture. The emotional and physical health, social skills, and cognitive-linguistic capacities that emerge in the early years are all important for success in school, the workplace, and in the larger community. Children develop these important skills through positive relationships with caring adults, play-based, engaging activities, and opportunities to explore. In recent times, kindergarten classroom curriculum has shifted away from meeting the developmental needs and abilities of children instead following a highly academic one-size-fits-all approach to learning. Coincidentally, or not, the majority of teacher preparation programs in the United States do not require (or in some cases even offer) a course on child development or the science of learning in young children.

Today, kindergarten in the United States looks much more like first, second or even third grade yet, developmentally, our children remain the same.

According to a study conducted by the University of Virginia, between 1998 and 2006, kindergarteners were held to increasingly higher academic expectations both prior to and during kindergarten, including the expectation that parents would teach children all (presumably English) letters before entering school. Teachers reported dedicating more time to advanced literacy and math content, teacher-directed instruction, and assessment and substantially less time to art, music, science, and child-selected activities. This trend continues today.

While some states require 30 minutes of recess for kindergartners, other states do not, and have in some cases reduced outdoor play time to 15 minutes or less per day. According to Eric Jensen’s book Teaching With the Brain in Mind, “A short recess arouses students and may leave them ‘hyper’ and less able to concentrate.” Children benefit from an extended recess session (approximately an hour in length), because it gives their bodies time to regulate the movement and bring their activity level back down again.” Our kindergarteners are playing less and ‘studying’ more.

The Inequities of Kindergarten Have Lasting Consequences

Just as a child’s experience prior to entering the public school system may be different than the next child, once they enter kindergarten, their experience can vary greatly based on the state, district and community in which they live. According to the most recent 50 State Comparison: K-3 Policies released by the Education Commision of the States, every district in the country offers at least a part day kindergarten with 16 states requiring full day kindergarten. In some states, districts are required to offer over 1,000 hours of kindergarten instruction per school year whereas others require as few as 50 hours. Some kindergarten teachers have as many as 33 children alone in a kindergarten classroom while children in other states may be in a class with half as many children present. Six states do not require kindergarten attendance.

Since the pandemic, enrollment and attendance in kindergarten has declined across the country primarily in communities of color. Based on a report released by Attendance Works in 2011, we know that children with low or at-risk attendance in kindergarten and first grade were more likely to not reach grade level standards in third grade in English language arts and math. National estimates suggest that one in 10 kindergarten and first grade students misses 18 or more days of the school year, or nearly a month. More recent data suggests this rate is most likely higher. These missed days in the early years can add up to weaker reading skills, higher rates of retention and lower attendance rates in later grades.This is especially true for children from low-income families, who depend on school for literacy development. Students from lower performing schools and/or low income families were more likely to have attendance issues in the early years compared to their peers from higher performing schools.

Bridging the Gap

For many students, we know that kindergarten is their first experience in the public school system. While some may not start school until first grade, kindergarten is often the bridge from early experiences to the K-12 system. Children of color and/or those living in low income communities may face the perfect storm that challenges the integrity of the bridge that is kindergarten. For example, access to kindergarten may be limited, cultural and linguistic appropriateness may be absent, chronic health issues may impact attendance, and transportation may be challenging. For many working families, a half day kindergarten does not meet the family’s needs. Full day programs may be out of reach for families either because they are not offered or, they live within communities where the first half of kindergarten is free but the second half of the day is fee-based, excluding lower income families.

Based on 2021 U.S. Census Data, 14% of 5 year old children in the United States are not enrolled in school. This means we have over 150,000 potentially eligible children not enrolled in kindergarten. How will every child reach the Common Core standards for kindergarten if they are not in kindergarten? And even if they are present, are the standards being implemented equitably across the country? Are our kindergarteners experiencing the most appropriate learning possible?

In order to ensure all children are provided the same opportunities for growth and success, we must ensure that all schools are ready for all children. To do so, it is important we explore opportunities to:

- Develop and implement federal and state policies requiring kindergarten curricula based on the science of learning and child development while aligned to the Common Core standards

- Ensure consistent, appropriate teacher to child ratios and class sizes in every kindergarten classroom

- Provide and require professional development regarding child development and the science of learning for all kindergarten teachers and administrators

- Provide opportunities for free full day kindergarten in all communities

- Provide necessary transportation, health, and community services to kindergarteners and their families

- Expand research of kindergarten readiness, effectiveness of kindergarten curricula, and long term outcomes of kindergarten students

As kindergarten focuses on academic performance and excludes those without classroom or transportation access, we tip the scales further between the “haves” and “have nots” – at the risk to all students and American competitiveness. How a child is introduced to school and how a child is prepared for formal education has lasting effects. If the U.S. wants to develop a workforce ready to lead and compete globally we have to start at the very beginning of a student’s school experience. Kindergarten, once radical, today needs a radical reinvention that provides for today’s challenges and readies children for tomorrow.

Without a robust education system that prepares our youth for future careers in key sectors, our national security and competitiveness are at risk.

The education R&D ecosystem must be a learning-oriented network committed to the principles of innovation that the system itself strives to promote across best practices in education and learning.

Across the country in small towns and large cities, rural communities and the suburbs, millions of young people are missing school at astounding rates.

CHIPS is poised to ramp up demand for STEM graduates, but the nation’s education system is unprepared to produce them.