Solutions for an Efficient and Effective Federal Permitting Workforce

The United States faces urgent challenges related to aging infrastructure, vulnerable energy systems, and economic competitiveness. Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy critical energy and infrastructure. Unfortunately, these projects face one common bottleneck: permitting.

Permits and authorizations are required for the use of land and other resources under a series of laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. However, recent court rulings and the Trump Administration’s executive actions have brought uncertainty and promise major disruption to the status quo. The Executive Order (EO) on Unleashing American Energy mandates guidance to agencies on permitting processes be expedited and simplified within 30 days, requires agencies prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, and revokes the Council of Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) authority to issue binding NEPA regulations. While these changes aim to advance the speed, efficiency, and certainty of permitting, the impact will ultimately depend on implementation by the permitting workforce.

Unfortunately, the permitting workforce is unprepared to swiftly implement changes following shifts in environmental policy and regulations. Teams responsible for permitting have historically been understaffed, overworked, and unable to complete their project backlogs, while demands for permits have increased significantly in recent years. Building workforce capacity is critical for efficient and effective federal permitting.

Project Overview

Our team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has spent 18 months studying and working to build government capacity for permitting talent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided resources to expand the federal permitting workforce, and we partnered with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a cross-agency understanding of the hiring challenges experienced in permitting agencies and prioritize key challenges to address. Through two co-hosted webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, we shared tactical solutions to improve the hiring process.

We complemented this understanding with voices from agencies (i.e., hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders) by conducting interviews to identify new issues, best practices, and successful strategies for building talent capacity. With this understanding, we developed long-term solutions to build a sustainable, federal permitting workforce for the future. While many of our recommendations are focused on permitting talent specifically, our work naturally uncovered challenges within the broader federal talent ecosystem. As such, we’ve included recommendations to advance federal talent systems and improve federal hiring.

Problem

Building permitting talent capacity across the federal government is not an easy endeavor. There are many stakeholders involved across different agencies with varying levels of influence who need to play a role: the Permitting Council staff, the Permitting Council members-represented by Deputy Secretaries (Deputy Secretaries) of permitting agencies, the Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) in each agency, the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), the Chief Human Capital Officer (CHCO) in each permitting agency, agency HR teams, agency permitting teams, hiring managers, and HR specialists. Permitting teams and roles are widely dispersed across agencies, regions, states, and programs. The role each agency plays in permitting varies based on their mission and responsibilities, and there are many silos within the broader ecosystem. Few have a holistic view of permitting activities and the permitting workforce across the federal government.

With this complex network of actors, one challenge that arises is a lack of standardization and consistency in both roles and teams across agencies. If agencies are looking to fill specialized roles unique to one permitting need, it means that there will be less opportunity for collaboration and for building efficiencies across the ecosystem. The federal hiring process is challenging, and there are many known bottlenecks that cause delays. If agencies don’t leverage opportunities to work together, these bottlenecks will multiply, impacting staff who need to hire and especially permitting and/or HR teams who are understaffed, which is not uncommon. Additionally, building applicant pools to have access to highly qualified candidates is time consuming and not scalable without more consistency.

Tracking workforce metrics and hiring progress is critical to informing these talent decisions. Yet, the tools available today are insufficient for understanding and identifying gaps in the federal permitting workforce. The uncertainty of long-term, sustainable funding for permitting talent only adds more complexity into these talent decisions. While there are many challenges, we have identified solutions that stakeholders within this ecosystem can take to build the permitting workforce for the future.

There are six key recommendations for addressing permitting workforce capacity outlined in the table below. Each is described in detail with corresponding actions in the Solutions section that follows. Our recommendations are for the Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress.

Solutions

The six solutions described below include an explanation of the problem and key actions our signal stakeholders (Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress) can take to build permitting workforce capacity. The table in the appendix specifies the stakeholders responsible for each recommendation.

Enhance the Permitting Council’s Authority to Improve Permitting Processes and Workforce Collaboration

Permitting process, performance, and talent management cut across agencies and their bureaus—but their work is often disaggregated by agency and sub-agency, leading to inefficient and unnecessarily discrete practices. While the Permitting Council plays a critical coordinating role, it lacks the authority and accountability to direct and guide better permitting outcomes and staffing. There is no central authority for influencing and mandating permitting performance. Agency-level CERPOs vary widely in their authority, whereas the Permitting Council is uniquely positioned for this role. Choosing to overlook this entity will lead to another interagency workaround. Congress needs to give the Permitting Council staff greater authority to improve permitting processes and workforce collaboration.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Improved Performance: Enhance provisions in FAST-41 and IRA by passing legislation that empowers the Permitting Council staff to create and enforce consistent performance criteria for permitting outcomes, permitting process metrics, permitting talent acquisition, talent management, and permitting teams KPIs.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Interagency Coordination: Empower the Permitting Council staff to manage interagency coordination and collaboration for defining permitting best practices, establishing frameworks for permitting, and reinforcing those frameworks across agencies. Clarify the roles and responsibilities between Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

- Assign Responsibility for Tracking Changes and Providing Guidance for Permitting Practices: Assign the Permitting Council staff in coordination with OMB responsibility for tracking changes and providing guidance on permitting practices in response to recent and ongoing court rulings that change how permitting outcomes are determined (e.g., Loper Bright/Chevron Deference, CEQ policies, etc.).

- Provide Permitting Council staff with Consistent Funding: Either renew components of IRA and/or IIJA funding that enables the Council to invest in agency technologies, hiring, and workforce development, or provide consistent appropriations for this.

- Enhance CERPO Authority and Position CERPOs for Agency-Wide and Cross-Agency Permitting Actions: Expand CERPO authority beyond the FAST-41 Act to include all permitting work within their agency. Through legislation, policy, and agency-level reporting relationships (e.g., CERPO roles assigned to the Secretary’s office), provide CERPOs with clear authority and accountability for permitting performance.

Build Efficient Permitting Teams and Standardize Roles

In our research, we interviewed one program manager who restructured their team to drive efficiency and support continuous improvement. However, this is not common. Rather, there is a lack of standardization in roles engaged in permitting teams within and across agencies, which hinders collaboration and prevents efficiencies. This is likely driven by the different roles played by agencies in permitting processes. These variances are in opposition to shared certifications and standardized job descriptions, complicate workforce planning, hinder staff training and development, and impact report consistency. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OMB, and the CHCO Council should improve the performance and consistency of permitting processes by establishing standards in permitting team roles and configurations to support cross-agency collaboration and drive continuous improvements.

- Characterize Types of Permitting Processes: Permitting Council staff should work with Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and Permitting Program Team leaders to categorize types of permitting processes based on project “footprint”, complexity, regulatory reach (i.e., regulations activated), populations affected and other criteria. Identify the range of team configurations in use for the categories of processes.

- Map Agency Permitting Roles: Permitting Council staff should map and clarify the roles played by each agency in permitting processes (e.g., sponsoring agency, contributing agency) to provide a foundation for understanding the types of teams employed to execute permitting processes.

- Research and Analyze Agency Permitting Staffing: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with OMB to conduct or refine a data call on permitting staffing. Analyze the data to compare the roles and team structures that exist between and across agencies. Conduct focus groups with cross agency teams to identify consistent talent needs, team functions, and opportunities for standardization.

- Develop Permitting Team Case Studies: Permitting Council staff should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight efficient and high performing permitting team structures and processes.

- Develop Permitting Team Models: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop team models for different agency roles (i.e., sponsor, lead agency, coordinating agency) that focus on driving efficiencies through process improvements and technology, and develop guidelines for forming new permitting teams.

- Create Permitting Job Personas: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop personas to showcase the roles needed on each type of permitting team and roles, recognizing that some variance will always remain, and the type of hiring authority that should be used to acquire those roles (e.g., IPA for highly specialized needs). This should also include new roles focused on process improvements; technology and data acquisition, use, and development; and product management for efficiency, improved customer experience, and effectiveness.

- Define Standardized Permitting Roles and Job Analyses: With the support of Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should identify roles that can be standardized across agencies based on the personas, and collaborate with permitting agencies to develop standard job descriptions and job analyses.

- Develop Permitting Practice Guide: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop a primer on federal permitting practices that explains how to efficiently and effectively complete permitting activities.

- Place Organizational Strategy Fellows: Permitting Council staff should hire at least one fellow to their staff to lead this effort and coordinate/liaise between permitting teams at different agencies.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with the CHCO Council to mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates.

- Revise Permitting Funding Requirements: Permitting Council staff should include requirements for the adoption of new team models and roles in the resources and coordination provided to permitting agencies to drive process efficiencies.

Improve Workforce Strategy, Planning, and Decisions through Quality Workforce Metrics

Agency permitting leaders and those working across agencies do not have the information to make informed workforce decisions on hiring, deployment, or workload sharing. Attempts to access accurate permitting workforce data highlighted inefficient methods for collecting, tracking, and reporting on workforce metrics across agencies. This results in a lack of transparency into the permitting workforce, data quality issues, and an opaque hiring progress. With these unknowns, it becomes difficult to prioritize agency needs and support. Permitting provided a purview into this challenge, but it is not unique to the permitting domain. OPM, OMB, the CHCO Council, and Permitting Council staff need to accurately gather and report on hiring metrics for talent surges and workforce metrics by domain.

- Establish Permitting Workforce Data Standards: OPM should create minimum data standards for hiring and expand existing data standards to include permitting roles in employee records, starting with the Request for Personnel Action that initiates hiring (SF52). Permitting Council staff should be consulted in defining standards for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Agency Data Sharing: OPM and OMB should require agencies share personnel action data; this should be done automatically through APIs or a weekly data pull between existing HR systems. To enable this sharing, agencies must centralize and standardize their personnel action data from their components.

- Create Workforce Dashboards: OPM should create domain-specific workforce dashboards based on most recent agency data and make it accessible to the relevant agencies. This should be done for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: The CHCO Council should mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates. This data should feed into existing agency talent management/acquisition systems to track workforce needs and support adaptive decision making.

Invest in Professional Development and Early Career Pathways

There are few early career pathways and development opportunities for personnel who engage in permitting activities. This limits agencies’ workforce capacity and extends learning curves for new staff. This results in limited applicant pools for hiring, understaffed permitting teams, and limited access to expertise. More recently, many of the roles permitting teams hired for were higher level GS positions. With a greater focus on early career pathways and development, future openings could be filled with more internal personnel. In our research, one hiring manager shared how they established an apprenticeship program for early career staff, which has led 12 interns to continue into permanent federal service positions. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should create more development opportunities and early career pathways for civil servants.

- Invest in Training to Upskill and Reskill Staff: The Permitting Council staff should continue investing in training and development programs (i.e., Permitting University) to upskill and reskill federal employees in critical permitting skills and knowledge. Leveraging the knowledge gained through creating standard permitting team roles and collaborating with permitting leaders, the Permitting Council staff should define critical knowledge and skills needed for permitting and offer additional training to support existing staff in building their expertise and new employees in shortening their learning curve.

- Allocate Permitting Staff Across Offices and Regions: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should implement a flexible staffing model to reallocate staff to projects in different offices and regions to build their experience and skill set in key areas, where permitting work is anticipated to grow. This can also help alleviate capacity constraints on projects or in specific locations.

- Invest in Flexible Hiring Opportunities: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should invest in a range of flexible hiring options, including 10-year STEM term appointments and other temporary positions, to provide staffing flexibility depending on budget and program needs. Additionally, OPM needs to redefine STEM to include technology positions that do not require a degree (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialists).

- Establish a Permitting Apprenticeship: The Permitting Council staff should establish a 1-year apprenticeship program for early career professionals to gain on-the-job experience and learn about permitting activities. The apprenticeship should focus on common roles shared across agencies and place talent into agency positions. A rotational component could benefit participants in experiencing different types of work.

Improve and Invest in Pooled Hiring for Common Positions

Outdated and inaccurate job descriptions slow down and delay the hiring process. Further delays are often caused by the use of non-skills-based assessments, often self-assessments, which reduce the quality of the certificate list, or the list of eligible candidates given to the hiring manager. HR leaders confront barriers in the authority they have to share job announcements, position descriptions (PDs), classification determinations, and certificate lists of eligible candidates (Certs). Coupled with the above ideas on creating consistency in permitting teams and roles and better workforce data, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should improve and make joint announcements, shared position descriptions, assessments, and certificates of eligibles for common positions a standard practice.

- Provide CHCOs the Delegated Authority to Share Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs: OPM and OMB should lower the barriers for agencies to share key hiring elements and jointly act on common permitting positions by delegating the authority for CHCOs to work together within and across their agencies, including with the Permitting Council staff.

- Revise Shared Certificate Policies: OPM and OMB should revise shared certificate policies to allow agencies to share certificates regardless of locations designated in the original announcement and the type of hire (temporary or permanent). They should require skills-based assessments in all pooled hiring. Additionally, OPM should streamline and clarify the process for sharing certificates across agencies. Agencies need to understand and agree to the process for selecting candidates off the certificate list.

- Create a Government-wide Platform for Permitting Hiring Collaboration: OPM should create a platform to gather and disseminate permitting job announcements, PDs, classification determinations, job/competency evaluations, and cert. lists to support the development of consistent permitting teams and roles.

- Pilot Sharing of Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs for Common Permitting Positions: OPM and the CHCO Council should collaborate with the Permitting Council staff to select most common and consistent permitting team roles (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialist) to pilot sharing within and across agencies.

- Track Permitting Hiring and Workforce Performance through Data Sharing and Dashboards: Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should leverage the metrics (see Improve Workforce Decisions Through Quality Workforce Metrics) and data actions above to track progress and make adjustments for sharing permitting hiring actions.

- Incorporate Shared Certificates into Performance: OPM and the CHCO Council should incorporate the use of shared certificates into the performance evaluations of HR teams within agencies.

Improve Human Resources Support for Hiring Managers

Hiring managers lack sufficient support in navigating the hiring and recruiting process due to capacity constraints. This causes delays in the hiring process, restricts the agency’s recruiting capabilities, limits the size of the applicant pools, produces low quality candidate assessments, and leads to offer declinations. The CHCO Council, OPM, CERPOs, and the Permitting Council staff need to test new HR resourcing models to implement hiring best practices and offer additional support to hiring managers.

- Develop HR Best Practice Case Studies: OPM should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight HR best practices for recruitment, performance management, hiring, and training to share with CHCOs and provide guidance for implementation.

- Document Surge Hiring Capabilities: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and CERPOs should document successful surge hiring structures (e.g., strike teams), including how they are formed, how they operate, what funding is required, and where they sit within an organization, and plan to replicate them for future surge hiring.

- Create Hiring Manager Community of Practice: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and Permitting Agency HR Teams with support from the CHCO Council should convene a permitting hiring manager community of practice to share best practices, lessons learned, and opportunities for collaboration across agencies. Participants should include those who engage in hiring, specifically permitting hiring managers, HR specialists, and HR leaders.

- Develop Permitting Talent Training for HR: OPM should collaborate with CERPOs to create a centralized training for HR professionals to learn how to hire permitting staff. This training could be embedded in the Federal HR Institute.

- Contract HR Support for Permitting: The Permitting Council staff should create an omnibus contract for HR support across permitting agencies and coordinate with OPM to ensure the resources are allocated based on capacity needs.

- Establish HR Strike Teams: OPM should create a strike team of HR personnel that can be detailed to agencies to support surge hiring and provide supplemental support to hiring managers.

- Place a Permitting Council HR Fellow: The Permitting Council should place an HR professional fellow on their staff to assist permitting agencies in shared certifications and build out talent pipelines for the key roles needed in permitting teams.

- Establish Talent Centers of Excellence: The CHCO Council should mandate the formation of a Talent Center of Excellence in each agency, which is responsible for providing training, support, and tools to hiring managers across the agency. This could include training on hiring, hiring authorities, and hiring incentives; recruitment network development; career fair support; and the development of a system to track potential candidates.

Next Steps

These recommendations aim to address talent challenges within the federal permitting ecosystem. As you can see, these issues cannot be addressed by one stakeholder, or even one agency, rather it requires effort from stakeholders across government. Collaboration between these stakeholder groups will be key to realizing sustainable permitting workforce capacity.

Setting the Stage for a Positive Employee Experience

Federal hiring ebbs and flows with changes in administrations, legislative mandates, attrition, hiring freezes, and talent surges. The lessons and practices in this blog post series explore the earlier stages of the hiring process. Though anchored in our permitting talent research, the lessons are universal in their application, regardless of the hiring environment. They can be used to accelerate and improve hiring for a single or multiple open positions, and they can be kept in reserve during hiring downturns.

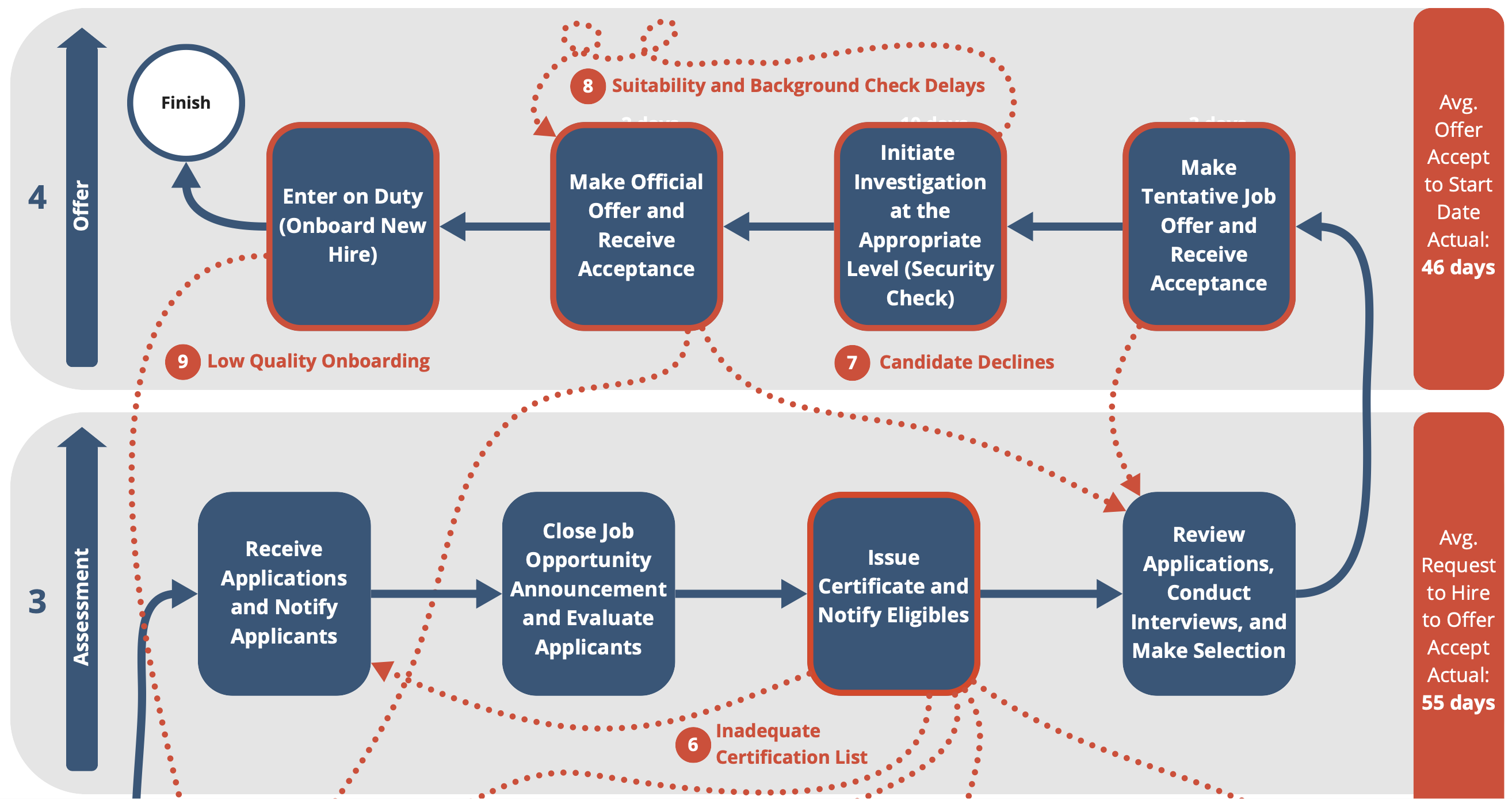

Assessing, Selecting, and Onboarding the Successful Candidate

Previously we described the end-to-end hiring process, the importance of getting hiring right from the start, and how sharing resources speeds hiring. This post focuses on the last two phases of the process: Assessment and Offer. While these phases include eight steps, we’ve narrowed down our discussion to five key steps:

- Close Job Opportunity Announcement and Evaluate Applicants

- Review Certificate of Eligibles, Conduct Interviews, and Make Selection

- Make Tentative Job Offer and Receive Acceptance

- Initiate Investigation at the Appropriate Level (Security Check)

- Make Official Offer and Enter on Duty (Onboard New Hire)

Our insights shared in this post are based on extensive interviews with hiring managers, program leaders, staffing specialists, workforce planners, and budget professionals as well as on-the-job experience. These recommendations for improvement focus on process and do not require policy or regulatory changes. They do require adoption of these practices more broadly throughout HR, program, and permitting managers, and staff. These recommendations are not unique to permitting; they apply broadly to federal government hiring. These insights should be considered both for streamlining efforts related to environmental permitting, as well as improving federal hiring.

Breaking Down the Steps

For each step, we provide a description, explain what can go wrong, share what can go right, and provide some examples from our research, where applicable.

Close Job Opportunity Announcement and Evaluate Applicants

Once the announcement period has ended, job announcements close, and HR begins reviewing the applications in the competitive hiring process. HR reviews the applications, materials provided by the applicants, and the completed assessments, which vary depending on the assessment strategy. This selection process is governed by policies in competitive examination and will be determined by whether the agency is following category rating, rule of many, or other acceptable evaluation methods.

If the agency is using a different hiring authority or flexibility, this step will change. For example, if the agency has Direct Hire Authority (DHA), they may not need to provide a rigorous assessment and may be able to proceed to selection after a review of resumes. Most agencies will still engage in some assessment process for these types of positions. After the applicants are evaluated, HR issues a Certificate of Eligibles (or “cert list”) with the ranking of the applicants from which the hiring manager can select, including the implementation of Veterans preference.

What Can Go Wrong

- Most applicant assessments rely on the resume review and candidate self-assessment. Applicants who understand the process rate themselves as highly qualified on all aspects of the job, resulting in a certificate list with unqualified applicants at the top. Agencies are now required by law to use skills-based assessments in the Chance to Compete Act and previous Executive Order guidance to prevent this, but the adoption process will be slow.

- HR staffing resources are frequently strained to immediately review applications and resumes causing delays. This causes applicant and hiring manager dissatisfaction and possibly a loss of attractive, qualified applicants. Within permitting, hiring managers have been struggling to find talent with the required expertise, especially specialized or niche expertise, and this loss is a critical setback.

- Frequently HR specialists do not consult with the program managers to gain a deep understanding of what they’re looking for in a resume or application and rely solely on their interpretation of the qualifications listed in the position description. This can result in poor quality applicants referred to the hiring manager.

What Can Go Right

- If the recruiters and hiring manager have engaged in effective recruiting, applicant quality is likely to be quite high. This eases the HR’s job of finding strong applicants.

- With a strong applicant pool, HR specialist can limit the number of applicants they consider and/or limit how long the job announcement is open. This will expedite the process, as the assessment will be faster. Rigorous assessments reduce the likelihood of unqualified applicants making it to the certificate list. A hiring manager who insists on a skills-based assessment will likely move forward with a successful hire. Using subject-matter experts in a Subject Matter Expert Qualifications Assessment (SME-QA) or similar assessment process can result in a strong list of applicants, and it has the added benefit of building familiarity by engaging the employee’s future peers in the process.

Review Certificate of Eligibles, Conduct Interviews, and Make Selection

HR sends a Certificate of Eligibles (certificate list) to the hiring manager that ranks the applicants who passed the assessment(s). Under competitive hiring rules (as opposed to some of the other hiring authorities), hiring managers are obligated to select from the top of the Certificate of Eligibles list, or those considered to be most qualified.

The Veterans preference rules also require that qualified Veterans move to the top of the list and must be considered first. Outside of competitive hiring and under other hiring authorities, the hiring manager may have more flexibility in the selection of candidates. For example, direct hire authority allows the hiring manager to make a selection decision based on their own review of resumes and applications.

If determined as part of the assessment process beforehand, the hiring manager may choose to conduct final interviews with the top candidates. In this case, the manager then informs HR of their selection decision.

What Can Go Wrong

- If the hiring manager cannot find an applicant they deem qualified on the certificate list, they inform HR, restart the hiring action, and/or re-post the position, further delaying the process. This happens frequently when the assessment tools default to a self-evaluation, or self-assessment. One Hiring Manager we met needed to request a second certificate list, and this extended the hiring process to nine months.

- Lack of resources in HR or the hiring manager’s program often results in evaluation and selection delays. Top applicants in high demand may take other jobs if the process takes longer than anticipated. This was a concern voiced by hiring managers during our interviews.

- In rare circumstances, agency funding could be uncertain and the budget function could rescind the approval to hire at this stage, frustrating hiring managers, applicants, and HR specialists.

What Can Go Right

- Strong recruiting early and throughout the process results in a strong certificate list with excellent candidates. One permitting agency, following best practice, kept a pipeline of potential candidates, including prior applicants to boost the quality of the applicant pool.

- An effective assessment process weeds out unqualified or unsuitable candidates and culls the list of applicants to only those who can do the job.

- A deep partnership between the HR staffing specialist and the hiring manager in which they discuss the skills and “fit” of the top candidates increases the hiring manager’s confidence in the selection.

Make Tentative Job Offer and Receive Acceptance

HR reaches out to the applicant to make a tentative job offer (i.e., tentative based on the applicant’s suitability determination, outlined below) and asks for a decision from the applicant within an acceptable time frame, which is normally a couple of days to a week. The HR staffing specialist will keep in close contact with the hiring manager and HR officials regarding the status of the candidate accepting the position.

What Can Go Wrong

- The applicant rejects the offer due to a misunderstanding of the job. This could be the location, remote work, or telework availability. In our interviews, we learned that some applicants declined offers because they believed the position was full time or a temporary position that could convert to a full time role, but that was not the case.

- The applicant rejects the offer due to a competing offer at a higher salary or as a result of other financial factors (e.g., relocation expenses). Some participants shared that financial factors had been the reason for some of their declinations.

- The applicant rejects the offer because of how they have been treated throughout the process or delays, which have led them to remain in their current role or accept another position.

What Can Go Right

- The HR specialist and others involved in the hiring process maintain regular communications with the candidate regarding their offer, listens to any concerns they may have about accepting their offer, and works with the hiring manager to correct any misperceptions about the job requirements.

- The HR specialist and the hiring manager understand the financial incentives they can use to negotiate salary, relocation expenses, signing bonuses, and other benefits to negotiate with the candidate. These options are usually agency-, function-, or job-specific.

Initiate Investigation at the Appropriate Level (Security Check)

Different federal occupations require different levels of suitability determinations or security clearances – from simple background checks to make sure the information an applicant provided on their application is accurate to a Top Secret clearance that enables the employee to access sensitive information. Each type of suitability determination has a different time frame needed for a security officer to evaluate the candidate. (Some positions require the security officer to not only interview the candidate, but also interview their friends, relatives, and neighbors.) This takes time during a part of the hiring process when both the candidate with the tentative offer and the hiring manager are anxious to move forward.

Once the candidate selection is made, the HR specialist works with the agency suitability professionals to initiate the background check and clearance process. Agency suitability experts work with the Defense Counterintelligence Security Agency (DCSA) to conduct the determination of the applicant.

What Can Go Wrong

- Applicants who have never applied for a federal job may be unfamiliar with their responsibilities during the suitability determination. If they do not fill out the forms properly, this causes delays, especially when the applicant is slow to respond.

- If the candidate does not know how long the suitability determination will take or what is involved in the process, the lack of transparency may create uncertainty and/or frustration among the applicant. Furthermore, if the candidate is not kept informed on where they are in the process or what to expect next, they may get discouraged and decline the tentative offer.

- Delays in scheduling fingerprinting appointments or access to fingerprinting facilities can also lengthen the time for the suitability determination.

What Can Go Right

- The hiring manager, HR specialist, and suitability experts work together to ensure the candidate knows where they are in the process and what is expected of them through frequent check-ins and progress tracking.

- Offering applicants a range of options for fingerprinting, including the opportunity to go to a third party vendor for prints. This can enable fast digital uploads within 24 hours (applicant may have to pay for third-party services).

- Hiring managers and HR specialists leverage the DCSA resources and tools, including the PDT Tool to determine the level of background check needed for their role.

- The Suitability manager uses a case management system to track and maintain all suitability requests. This will help ensure nothing is lost, and system notifications can help keep the process on track by requesting applicants, hiring managers, and HR specialists complete their tasks in a timely manner. One interview participant highlighted this as critical to the timeliness of the suitability process.

Make Official Offer and Enter on Duty (Onboard New Hire)

The last step in the hiring process is administering the final offer of employment, identifying and Entry on Duty date, and onboarding the new employee. HR staff usually shepherd the new employee through this step. The hiring manager, administrator, or a peer mentor frequently assists the new employee in making sure the employee understands what they need to do to begin contributing to the agency.

What Can Go Wrong

- The candidate declines the final offer of employment due to delays or dissatisfaction with their experience during the hiring process.

- Frequently, onboarding consists of filling out online forms, paperwork to register the new employee in the various agency systems, and required compliance training. Minimal attention is spent on their work and how it connects to the agency mission.

- All too often, the new employee does not receive their computer equipment, phone, or other resources necessary for them to do their jobs in a timely manner. These delays degrade the initial employee experience.

What Can Go Right

- HR and hiring manager program staff stay in constant connection with the candidate as they accept the job and start the onboarding process, ensuring that the early employee experience is positive. This includes not only the administrative activities but also introductions to the agency and the work they will be doing.

- Program managers and administrative staff can work with IT functions and other departments to make sure the new employee has the equipment and resources needed to start their job successfully.

- The hiring manager establishes their relationship with the new employee during onboarding, creating a positive atmosphere for the employee by clearly articulating expectations.

Conclusion

Hiring success depends heavily on the broader hiring ecosystem. There are many stakeholders (e.g., leadership, budget, program, HR, suitability, applicant) who play a crucial role; collaboration and communication is important for both a timely and successful hire. Adoption of best practices across the ecosystem will help to improve hiring outcomes, reduce process delays, and enhance the overall hiring experience for all parties involved. The best practices outlined in our blog post series provide a guide to better navigate the hiring process.

The overall intent of hiring is to improve the performance of the federal program or function. New employees expand the organization’s workforce capacity and bring capabilities needed to achieve the mission. A skilled, prepared, and engaged federal employee can have an outsized impact on a program’s success.

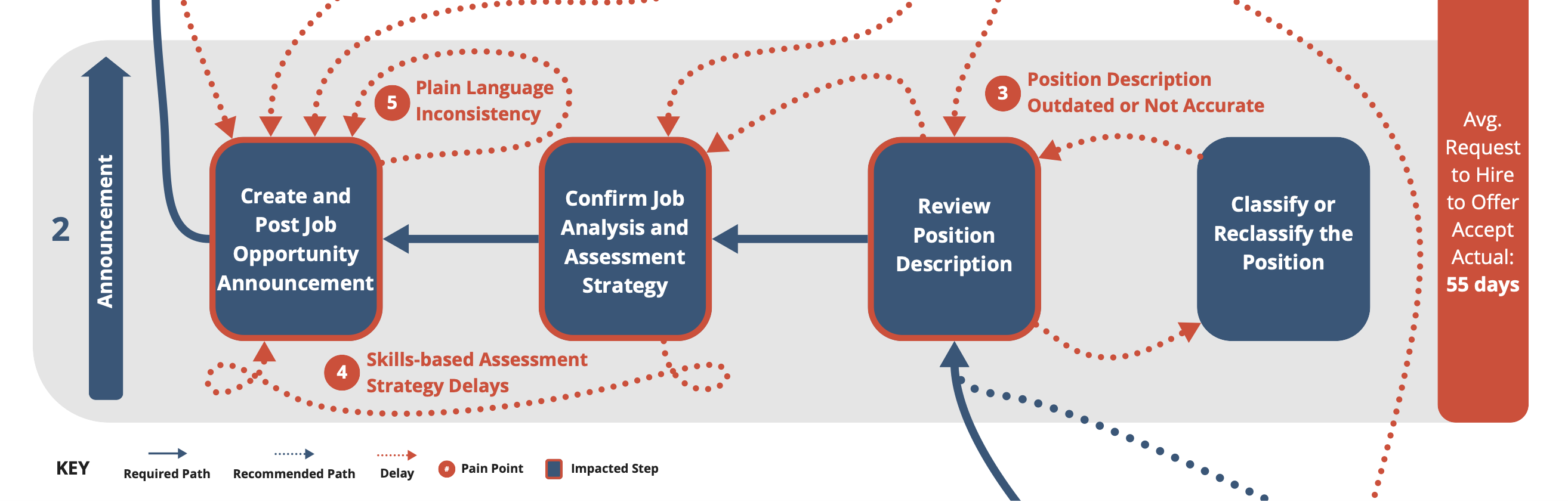

Herding Unicorns: Sharing Resources Speeds Hiring

“There really are fewer unicorn positions out there than we all imagined” – Bob Leavitt, HHS CHCO on shared PDs and certificates for common positions

Creating a job announcement that attracts high quality applicants is critical to the hiring process. For hiring managers, finding a balance between identifying the unique details of the position and managing the time and resources required is a challenge. When defining a position, there are many potential “off-ramps.” While these diversions are sometimes necessary, they often result in significant time delays and demand scarce resources from both hiring managers and HR staff. Improvements over the past few years offer hiring managers opportunities to accelerate the process while improving applicant quality, primarily done through collaboration within and across agencies that requires a level of standardization.

In our previous blog posts, we outlined the hiring process and dove into the first phase – Getting Hiring Right from the Start. This post discusses the second phase of the process: planning for and announcing the job. This phase includes four steps:

- Review Position Description and Confirm Job Analysis

- Classify or Reclassify the Position

- Confirm Job Analysis and Assessment Strategy

- Create and Post the Job Opportunity Announcement (JOA)

Our insights shared in this post are based on extensive interviews with hiring managers, program leaders, staffing specialists, workforce planners, and budget professionals as well as on-the-job experience. These recommendations for improvement focus on process and do not require policy or regulatory changes. They do require adoption of these practices more broadly throughout HR, program, and permitting managers, and staff. Additionally, our insights here are not unique to permitting, rather they apply broadly to federal government hiring. These insights should be considered both for streamlining efforts related to environmental permitting, as well as improving federal hiring.

Breaking Down the Steps

For each step in this phase, we provide a description, explain what can go wrong, share what can go right, and provide some examples from our research, where applicable.

Review Position Description and Confirm Job Analysis

The Position Description (PD) is core to the hiring process. It describes the occupation, grade level, job duties, qualifications, and any special skills needed for the job and agency. In hiring, it is used to develop the job announcement, review the position’s classification, and establish a foundation for assessing candidates. Outside of hiring, it is used in performance management, position management, probation period evaluation, and serves as a reference for disciplinary action.

At this step, a hiring manager reviews the position description to make sure it is an accurate, current depiction of the job requirements, which may require a review of the past job analysis, or the evaluation of the knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviors, and experience needed for the positions (i.e., the competencies). The PD can be inaccurate due to dynamic changes in the job: core duties, technologies used, process changes, and supervisory responsibilities. These updates can range from simple wording changes to major changes that require additional work.

In our interviews, we heard from hiring managers and HR specialists that updating position descriptions had been a challenge and bottleneck in their hiring process. One hiring manager shared that they chose to not change their positions even if they wanted a different role because of the anticipated time delays. Other participants shared that they have begun moving towards standardized PDs within their agency to reduce redundancies and enable more collaboration.

What Can Go Wrong

- Based on hiring manager feedback to the HR specialist, a significantly out-of-date PD can result in major revisions that require a job analysis and/or reclassification of the position. This can delay the hiring process by weeks, or even months. If the grade level or other key aspects of the position need to be changed, the position requisition (SF-52 form) needs to be revised, adding even more time.

- Overzealous staffing specialists or classifiers may perceive major job changes where they do not exist in practice, causing delays for additional reviews and revisions.

- Too much specificity in job task descriptions will require additional job analyses, causing further delays. Whereas not enough specificity provides insufficient guidance for developing the assessment strategy, JOA, and other management actions dependent on the PD (e.g., performance management, development plans, or disciplinary action).

What Can Go Right

- With permission from their Chief Human Capital Office (CHCO) office, a hiring manager can use a current PD from elsewhere in the agency that accurately describes the job. A number of agencies have created PD libraries that bring together common PDs from across the organization. One HR Leader we interviewed described having a library of available positions that hiring managers are encouraged to look through when creating a new position. Hiring managers can even include specialized skills in an existing PD to augment the fundamental job duties, avoiding reclassification.

- Hiring managers can offer flexibility in location, where possible. Based on our interviews, agencies are seeing greater success attracting strong applicants with flexible locations, remote work, or telework options.

- The HR staffing specialist can search for and find a shared certificate of eligibles (i.e., a list of eligible candidates) for their PD already available through their own agency HR talent systems or through the USAJOBS Agency Talent Portals. As long as the job and grade match, the hiring manager can bypass much of the hiring process and move quickly to identifying applicants.

- Many agencies require managers to review and if needed, revise position description every year during the performance management process. This can make sure the PD is ready to go for the hiring process. In our interviews, we heard that this is required, but may not be regularly completed.

Classify/Reclassify the Position

Position classification is a structured process in every Cabinet agency in which an expert assesses the requirements of the job by evaluating factors such as knowledge, skills, abilities, complexity, and supervisory controls/responsibilities. The process is initiated when a PD is deemed inaccurate due to changes in the role. The HR staffing specialist will ask a classification expert to assess the role. This is done by reviewing the PD, existing job analyses, past classifications, and classification audits. They will also gather and review data from the hiring manager and others working in similar roles. Based on their assessment, the classifier can recommend changes to the grade level and/or the occupational series. These changes could be simple revisions or a more extensive reclassification. This process can take days or weeks to complete and can delay the hiring process significantly.

What Can Go Wrong

- HR staff and classifiers sometimes do not explain the need for classification and its benefits. This makes the process opaque and leaves the hiring manager wondering how long it will take to complete.

- HR staffing specialists and classifiers vary widely in how they apply the classification standards. Some seek greater specificity, and therefore insist on a full classification review when it may not be needed.

- Agency HR functions frequently lack workforce capacity for classification and job analyses. As a result, they have to prioritize requests, which can cause further delays.

What Can Go Right

- Collaboration and transparency between hiring managers, staffing specialists, and classifiers can lead to rapid approval of a PD and classification review. If there cannot be a quick approval, this close engagement leads to clearer expectations and realistic timelines.

- If the same position, at the same grade level, has recently completed a classification audit in a different part of the agency, the hiring team can use it. This can also be done across agencies with CHCO approval.

- Hiring managers who invest time to understand the position well and articulate the roles, duties, relationships, and complexity to the classifier can improve the outcomes and make the process more efficient.

- Agencies that lack classification resources frequently engage with outside contractors or retired annuitants to provide more capacity for the classification and job analysis work.

Develop Assessment Strategy

A critical, but sometimes overlooked step in hiring is developing the assessment strategy for the position. This determines how the HR staff and hiring manager will evaluate applicants and identify candidates for the certificate list, or the list of eligible applicants. The strategy needs to assess candidates based on the defined job duties and position criteria, and it plays a major role in determining the quality of candidates.The assessment strategy consists of three parts:

- How job applications and resumes are reviewed

- How the applicants demonstrate the required skills and abilities

- How the hiring manager makes the final selection

Recently, agencies have moved toward evaluating applicants by assessing their skills, spurred on by the Executive Order and guidance on skills-based assessments and now reinforced by the Chance to Compete Act. This shift aims to move away from relying on education and/or self-assessments. Skills-based assessments can include online tests, skills-based simulation exercises, simulated job tryouts, as well as the Subject Matter Expert Qualifications Assessment (SME-QA) process developed by OPM and USDS/OMB. This improves the quality of assessments and aims to ensure the candidates on the certificate list are qualified for the job.

What Can Go Wrong

- If a hiring manager and HR staffing specialist bypass this step, this frequently results in a certificate list with unqualified candidates. Without a strategy, many default to using a resume review and self-assessments. Unfortunately, our research indicated that many agencies are still using self-assessments.

- Most of the time, resume screening is left solely to the HR staff. Lack of alignment between HR specialists and hiring managers on essential qualifications results in an inaccurate screening, leading unqualified candidates to make the cut. Too often, HR staff will only screen applications for the exact phrases that appear in the job announcement. Applicants know this and revise their documents accordingly.

- When a skills-based assessment does not exist for the position and specific grade level, it needs to be created. This takes time and expert resources, thus delaying the hiring process.

- Inaccurate resume screenings and self-assessments frequently lead to a high number of unqualified Veterans making the top of the certificate list due to Veterans preference. Unfortunately, this leads to a negative perception of Veterans preference.

What Can Go Right

- Working with HR staffing specialists to find existing assessments can save time and improve candidate selection quality. In addition, USA Hire, Monster, and other HR talent acquisition platforms are offering compendiums of assessment strategies and tools that can be accessed, usually for free.

- Deep engagement between hiring managers, staffing specialists, and assessment professionals in developing an assessment strategy and selecting tools pays off. This can lead to enhanced resume and application screening, stronger alignment between candidate and position needs, and higher quality certificate lists of eligible candidates.

- Engagement with staffing specialists and assessment experts can also help the hiring manager understand and make tradeoff decisions related to the speed and ease of administration. For example, an online test may be easier to utilize, while embedding Subject Matter Experts into the selection process may increase the efficacy.

Create and Post Job Opportunity Announcement

Though creating and posting the JOA is relatively straightforward, lack of attention to this step can reduce the number of attractive candidates. The HR staffing specialist usually creates the JOA in consultation with the hiring manager to ensure that it not only accurately reflects the job duties, but also sells the job to potential applicants. The JOA is an opportunity to showcase the importance of the role and its contribution to the agency’s mission.

The JOA outlines applicant eligibility, job duties, job requirements (e.g., conditions of employment, qualifications, etc.), education (if needed), assessment strategy, and application requirements. It also lists the occupation, grade level, location, and other details. See USAJOBS for examples.

What Can Go Wrong

- Some hiring managers and staffing specialists are under the misapprehension that the JOA needs to contain the exact language from the PD in both the title and description. This can include jargon and terms that are unfamiliar to those not within the organization.

- Unintentionally, a hiring manager may lock the job location in a specific city or metropolitan area when the job could be remote or in multiple locations. To correct this, the JOA will need to be taken down and re-posted if no suitable applicants can be found.

What Can Go Right

- JOAs need to be tailored to the target applicants, and working with those currently in the job or in a related-discipline can help in crafting an attractive JOA.

- Using plain language in the job title and description instead of jargon will attract more candidates. OPM has published plain language guidance to help hiring managers and staffing specialists do this effectively.

- Earlier in the hiring process, successful hiring managers and staffing specialists define recruiting and sourcing strategies to attract candidates. This can include posting the job on alternative sites (e.g., agency websites, LinkedIn, Handshake, Indeed, etc.) in addition to USAJOBS to reach a broader audience. One agency’s HR team described leveraging multiple platforms for outreach and was able to successfully recruit many qualified candidates for their open roles. Strategies can also include asking hiring managers, peers, agency leaders, and recruiters to message highly qualified candidates to expand the applicant pool and bring in more qualified applicants.

Conclusion

Throughout this phase of work, there are many actions hiring managers and staffing specialists can take to streamline the process and improve the quality of eligible candidates. Most importantly, hiring managers and staffing specialists can collaborate within and across agencies to expedite and simplify the process. Using an existing PD from another part of the agency, finding an assessment tool for the job and grade level, pooling resources on a common job announcement with a peer, and using shared certificates to move straight to a job offer are all ways you can find a well-qualified hire faster. More tips and techniques to improve hiring can be found in OPM’s Workforce of the Future Playbook.

Changes that can be made to improve efficiency and promote collaboration. These center on moving to standardized PDs, where appropriate, leveraging shared certifications with those standardized PDs, and investing in skills-based assessments, which are now required by law in the Chance to Compete Act.

Making these actions common practice is one of the key challenges to improving hiring. The Executive Order on skills-based hiring states “in light of today’s booming labor market, the Federal government must position itself to compete with other sectors for top talent.” It is critical we take advantage of these collaboration tools that can improve the hiring experience for all those involved.

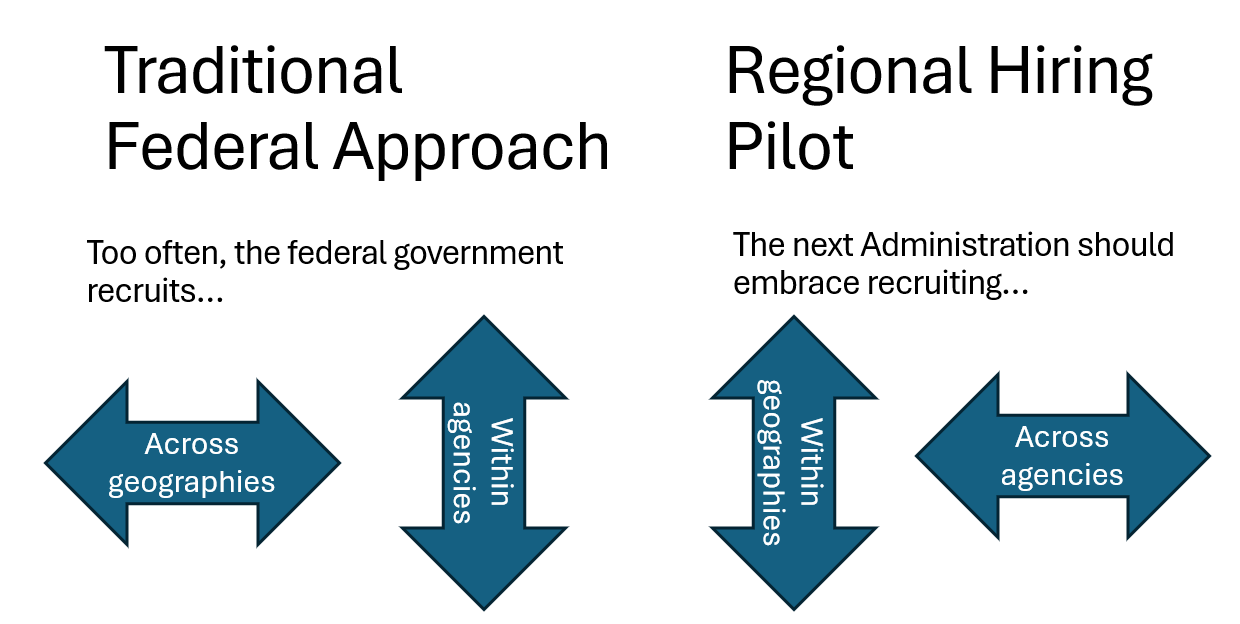

Unpacking Hiring: Toward a Regional Federal Talent Strategy

Government, like all institutions, runs on people. We need more people with the right skills and expertise for the many critical roles that public agencies are hiring for today. Yet hiring talent in the federal government is a longstanding challenge. The next Administration should unpack hiring strategy from headquarters and launch a series of large scale, cross-agency recruitment and hiring surges throughout the country, reflecting the reality that 85% of federal employees are outside the Beltway. With a collaborative, cross-agency lens and a commitment to engaging jobseekers where they live, the government can enhance its ability to attract talent while underscoring to Americans that the federal government is not a distant authority but rather a stakeholder in their communities that offers credible opportunities to serve.

Challenge and Opportunity

The Federal Government’s hiring needs—already severe across many mission-critical occupations—are likely to remain acute as federal retirements continue, the labor market remains tight, and mission needs continue to grow. Unfortunately, federal hiring is misaligned with how most people approach job seeking. Most Americans search for employment in a geographically bounded way, a trend which has accelerated following the labor market disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, federal agencies tend to engage with jobseekers in a manner siloed to a single agency and across a wide variety of professions.

The result is that the federal government tends to hire agency by agency while casting a wide geographic net, which limits its ability to build deep and direct relationships with talent providers, while also duplicating searches for similar roles across agencies. Instead, the next Administration should align with jobseekers’ expectations by recruiting across agencies within each geography.

By embracing a new approach, the government can begin to develop a more coordinated cross-agency employer profile within regions with significant federal presence, while still leveraging its scale by aggregating hiring needs across agencies. This approach would build upon the important hiring reforms advanced under the Biden-Harris Administration, including cross-agency pooled hiring, renewed attention to hiring experience for jobseekers, and new investments to unlock the federal government’s regional presence through elevation of the Federal Executive Board (FEB) program. FEBs are cross-agency councils of senior appointees and civil servants in regions of significant federal presence across the country. They are empowered to identify areas for cross-agency cooperation and are singularly positioned to collaborate to pool talent needs and represent the federal government in communities across the country.

Plan of Action

The next Administration should embrace a cross-agency, regionally-focused recruitment strategy and bring federal career opportunities closer to Americans through a series of 2-3 large scale, cross-agency recruitment and hiring pilots in geographies outside of Washington, DC. To be effective, this effort will need both sponsorship from senior leaders at the center of government, as well as ownership from frontline leaders who can build relationships on the ground.

Recommendation 1. Provide Strategic Direction from the Center of Government

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should launch a small team, composed of leaders in recruitment, personnel policy and workforce data, to identify promising localities for coordinated regional hiring surges. They should leverage centralized workforce data or data from Human Capital Operating Plan workforce plans to identify prospective hiring needs by government-wide and agency-specific mission-critical occupations (MCOs) by FEB region, while ensuring that agency and sub-agency workforce plans consistently specify where hiring will occur in the future. They might also consider seasonal or cyclical cross-agency hiring needs for inclusion in the pilot to facilitate year-to-year experimentation and analysis. With this information, they should engage the FEB Center of Operations and jointly select 2-3 FEB regions outside of the capital where there are significant overlapping needs in MCOs.

As this pilot moves forward, it is imperative that OMB and OPM empower on-the-ground federal leaders to drive surge hiring and equip them with flexible hiring authorities where needed.

Recommendation 2. Empower Frontline Leadership from the FEBs

FEB field staff are well positioned to play a coordinating role to help drive surges, starting by convening agency leadership in their regions to validate hiring needs and make amendments as necessary. Together, they should set a reasonable, measurable goal for surge hiring in the coming year that reflects both total need and headline MCOs (e.g., “in the next 12 months, federal agencies in greater Columbus will hire 750 new employees, including 75 HR Specialists, 45 Data Scientists, and 110 Engineers”).

To begin to develop a regional talent strategy, the FEB should form a small task force drawn from standout hiring managers and HR professionals, and then begin to develop a stakeholder map of key educational institutions and civic partners with access to talent pools in the region, sharing existing relationships and building new ones. The FEB should bring these external partners together to socialize shared needs and listen to their impressions of federal career opportunities in the region.

With these insights, the project team should announce publicly the number and types of roles needed and prepare sharp public-facing collateral that foregrounds headline MCOs and raises the profile of local federal agencies. In support, OPM should launch regional USAJOBS skins (e.g., “Columbus.USAJOBS.gov”) to make it easy to explore available positions. The team should make sustained, targeted outreach at local educational institutions aligned with hiring needs, so all federal agencies are on graduates’ and administrators’ radar.

These activities should build toward one or more signature large, in-person, cross-agency recruitment and hiring fairs, perhaps headlined by a high profile Administration leader. Candidates should be able to come to an event, learn what it means to hold a job in their discipline in federal service, and apply live for roles at multiple agencies, all while exploring what else the federal government has to offer and building tangible relationships with federal recruiters. Ahead of the event, the project team should work with agencies to align their hiring cycles so the maximum number of jobs are open at the time of the event, potentially launching a pooled hiring action to coincide. The project team should capture all interested jobseekers from the event to seed the new Talent Campaigns function in USAStaffing that enables agencies to bucket tranches of qualified jobseekers for future sourcing.

Recommendation 3. Replicate and Celebrate

Following each regional surge, the center of government and frontline teams should collaborate to distill key learnings and conclude the sprint engagement by developing a playbook for regional recruitment surges. Especially successful surges will also present an opportunity to spotlight excellence in recruitment and hiring, which is rarely celebrated.

The center of government team should also identify geographies with effective relationships between agencies and talent providers for key roles and leverage the growing use of remote work and location negotiable positions to site certain roles in “friendly” labor markets.

Conclusion

Regional, cross-agency hiring surges are an opportunity for federal agencies to fill high-need roles across the country in a manner that is proactive and collaborative, rather than responsive and competitive. They would aim to facilitate a new level of information sharing between the frontline and the center of government, and inform agency strategic planning efforts, allowing headquarters to better understand the realities of recruitment and hiring on the ground. They would enable OPM and OMB to reach, engage, and empower frontline HR specialists and hiring managers who are sufficiently numerous and fragmented that they are difficult to reach in the present course of business.

Finally, engaging regionally will emphasize that most of the federal workforce resides outside of Washington, D.C., and build understanding and respect for the work of federal public servants in communities across the nation.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Building Talent Capacity for Permitting: Insights from Civil Servants

Have you ever asked a civil servant in the federal government what it was like to hire new staff? It’s quite common to hear how challenging it is to navigate the hiring process and how long it takes to get someone through the door. At FAS, we know it’s hard. We’ve seen how it works, and we’ve heard stories from civil servants in government.

Following the wave of legislation aimed at addressing infrastructure, environment, and economic vulnerabilities (i.e., the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS)), we knew that the federal government’s hiring needs were going to soar. As we previously stated, permitting is a common bottleneck that would hinder the implementation of BIL, IRA, and CHIPS. The increase in work following this legislation came in conjunction with a push for faster permits, which in turn significantly increased agency workload. Many agencies did not have the capacity to clear the existing backlogs of permitting projects they already had in their pipeline, which would not even begin to address the new demand that would result from these laws. As such, talent capacity, or having staff with the knowledge and skills needed to meet the work demands, presented a major bottleneck.

We also knew that surge hiring is not a strength of the government, and there are a number of reasons for that; some we highlighted in our recent blog post. It’s a difficult task to coordinate, manage, and support the hiring process for a variety of roles across many agencies. And agencies that are responsible for permitting activities, like environmental reviews and authorizations, do not have standardized roles and team structures to make it easier to hire. Furthermore, permitting responsibility and roles are disaggregated within and across agencies – some roles are permanent, others are temporary. Sometimes responsibility for permitting is core to the job. In other cases, the responsibility is part of other program or regional/state needs. This makes it hard to take concerted and sustained action across government to improve hiring.

While this sounds like a challenge, FAS saw an opportunity to apply our talent expertise to permitting hiring with the aim of reducing the time to hire and improving the hiring experience for both hiring managers and HR specialists. Our ultimate goal was to enable the implementation of this new legislation. We also knew that focusing on hiring for permitting would offer a lens to better understand and solve for systemic talent challenges across government.

As part of this work, we had the opportunity to connect and collaborate with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a broad understanding of the hiring difficulties experienced across permitting agencies. This helped us identify some of the biggest challenges preventing progress, which enabled us to co-host two webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, focused on showcasing tactical solutions that could be applied today to improve hiring processes.

Our team wanted to complement this understanding of the core challenges with voices from agencies – hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders – who have all been involved in the process. We hoped to validate the challenges we heard and identify new issues, as well as capture best practices and talent capacity strategies that had been successfully employed. The intention of this blog is to capture the lessons from our discussions that could support civil servants in building talent capacity for permitting-related activities and beyond, as many solutions identified are broadly applicable across the federal government.

Approach

Our team at FAS reached out to over 55 civil servants who work across six agencies and 17 different offices identified through our hiring webinars to see if they’d be willing to share about their experiences trying to hire for permitting-related roles in the implementation of IRA, BIL, and CHIPS. Through this outreach, we facilitated 14 interviews and connected with 18 civil servants from six different organizations within the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Defense, Department of Interior, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Commerce. The roles of the participants varied; it included Hiring Managers, HR Specialists, HR Leaders, Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers, and Chief Human Capital Officers.

In our conversations, we focused on identifying their hiring needs to support permitting-related activities within their respective organization, the challenges they experience in trying to hire for those new positions, what practices were successful in their hiring efforts, and any recommendations they had for other agencies. We synthesized the data we gathered through these discussions and identified common challenges in hiring, successful hiring practices, talent capacity strategies, and additional tips for civil servants to consider.

Challenges to Hiring

We identified many challenges hindering agencies from quickly bringing on new staff to fill their open roles. From the start, many teams responsible for permitting were already very understaffed. One interviewee explained that they had serious backlogs requiring complex analysis, but were only able to triage and take on what was feasible. Another shared that they initially were only processing 60% of their workload annually. A third interviewee explained that some of their staff had previously been working on 4-5 Environment Impact Statements (EIS) at one time, which is very high and not common for the field. Their team had a longstanding complaint about high workload that led to a high attrition rate, which only increased the need for more hires. In addition to the permitting teams being under resourced, many HR counterpart teams were also understaffed. This created an environment where teams needed to hire a significant number of new staff, but did not necessarily have the HR support necessary to execute.

The budget was the next issue many agencies faced. The budget constraints resulting from the time-bound funding of IRA and BIL raised a number of important questions for the agencies. BIL funds expire at the end of FY2026 and IRA funds expire anywhere between 2-10 years from the legislation passing in 2022. For example, the funds allocated to the Permitting Council in the IRA expire at the end of FY2031, and some of these funds have been given to agencies to bolster workforce capacity for supporting timely permitting reviews. Ultimately, agencies needed to decide if they wanted to hire temporary or full time employees. This decision cannot be made without additional information and analysis of retirement rates, attrition rates, and other funding sources.

In addition to managing the budgetary constraints, agencies needed to determine how they would allocate the funds provided to their bureaus and programs. This required negotiations, justifications, and many discussions. The ability of Program Leaders to negotiate and justify their allocation is dependent upon their ability to accurately conduct workforce planning, which was a challenge identified through interviews. Specifically, some managers were challenged to accurately plan in an environment that is demand-driven and continuously evolving. Additionally, managing staff who have a variety of responsibilities and may only work on permitting projects for a portion of their time only increases the complexity of the planning process.

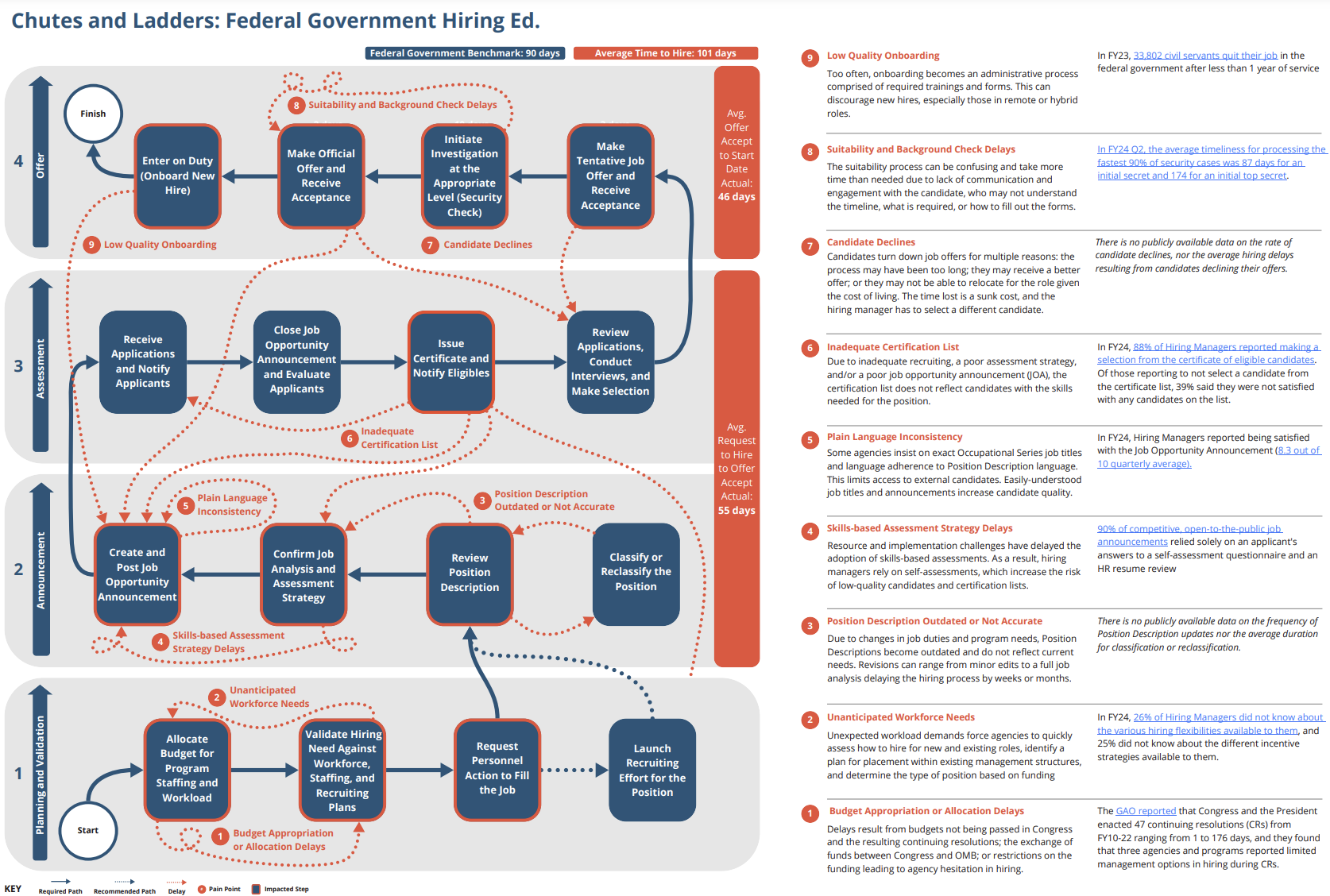

A number of challenges we heard were common pain points in the federal government’s hiring process, as noted in Many Chutes and Few Ladders in the Federal Hiring Process. These include:

- Assessments: Inadequate assessments have led to issues with the certificate lists of eligible candidates provided from the HR Specialist to the hiring manager. Some hiring managers have received lists with too many candidates to choose from, while others have been disappointed to not see qualified candidates on the list. This is largely a result of assessments that do not effectively screen qualified applicants. Self-assessments are an example of this, where applicants score their own abilities in response to a series of multiple choice questions. From our conversations, self-assessments are still a commonly used practice, and skills-based assessments have not been widely adopted.

- Job Descriptions: Both creating new and updating job descriptions has caused delays in the hiring process. Some agencies have started moving towards standardized job descriptions with the goal of making the process more efficient, but this has not been an easy task and has required a lot of time for collaboration across a variety of stakeholders.

- Background Checks: Delays in background checks have slowed the process. These delays often result from mistakes in or incomplete Electronic Questionnaires for Investigations Processing (e-QIP) forms, delays in scheduling fingerprint appointments, a lack of infrastructure for sharing and tracking information between key stakeholders (e.g., selected applicant, suitability manager, hiring manager), and delayed responses to notifications in the process.

- Candidate Declinations: Candidates declining a job offer have set a number of agencies back, especially those lacking deep applicant pools. The reasons provided have varied. Some applicants believed that the temporary positions were negotiable or did not realize they had applied to a term position, and they were no longer interested. In some cases, agency hiring managers did not know they had hiring flexibilities or incentives to offer that may have bridged the gap for the candidate. Others were unable to accept the offer for the specific location, citing the increased cost of living and housing prices as a barrier.

Lastly, recruiting was noted as a challenge by a number of participants. Recruiting for a qualified applicant pool has been difficult, especially for those looking to hire very specialized roles. One participant explained their need for someone with experience working in a specific region of the country and the limitations that came with not being able to offer a relocation bonus. Another participant described the difficulty in finding qualified candidates at the right grade level because the pay scale was very limiting for the expertise required. These challenges are exacerbated in agencies that lack recruiting infrastructure and dedicated resources to support recruitment.

These challenges manifested as bottlenecks in the hiring process and present opportunities for improvement. Apart from the new, uncertain funding, these challenges are not novel. Rather, these are issues agencies have been facing for many years. The new legislation has drawn broader attention back to these problems and presents an opportunity for action.

Successful Hiring Practices

Despite these bottlenecks, participants shared a number of practices they employed to improve the hiring process and successfully bring new staff onboard. We wanted to share seven (7) practices that could be adopted by civil servants today.

Establish Hiring Priority and Gain Leadership Support

One agency leveraged the Biden-Harris Permitting Action Plan to establish and elevate their hiring needs. Following the guidance shared by OMB, CEQ, and the Permitting Council, this agency set out to develop an action plan that would function as a strategic document over the next few years. They employed a collaborative approach to develop their plan. The Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officer (CERPO) and Deputy CERPO, the roles responsible for overseeing environmental review and permitting projects within their agencies and under their jurisdiction, brought together a team of NEPA Specialists and other staff engaged in environmental reviews and permitting across their organizations with equities. This group collectively brainstormed what they could do to strengthen and streamline permitting and environmental reviews at their agency. From this list, they prioritized five key focus areas for the first phase of their plan. This included hiring as the highest priority because it had been identified as a critical issue. Given their positioning within the organization and the Administration’s mandate, they were able to gain the support of the Secretary, and as a result, escalate their hiring needs to fill over 30 open positions over the course of FY24.

Collaborate and Share Across the Organization

Sharing and collaborating across the agency helped many expedite the hiring process. Here are examples that highlight the importance of this for success.

(1) One agency described how they share position descriptions across the enterprise. They have a system that allows any hiring manager to search for a similar position that they could use themselves or refine for their specific role. This reduces the time spent by hiring managers recreating positions.