Unpacking Hiring: Toward a Regional Federal Talent Strategy

Government, like all institutions, runs on people. We need more people with the right skills and expertise for the many critical roles that public agencies are hiring for today. Yet hiring talent in the federal government is a longstanding challenge. The next Administration should unpack hiring strategy from headquarters and launch a series of large scale, cross-agency recruitment and hiring surges throughout the country, reflecting the reality that 85% of federal employees are outside the Beltway. With a collaborative, cross-agency lens and a commitment to engaging jobseekers where they live, the government can enhance its ability to attract talent while underscoring to Americans that the federal government is not a distant authority but rather a stakeholder in their communities that offers credible opportunities to serve.

Challenge and Opportunity

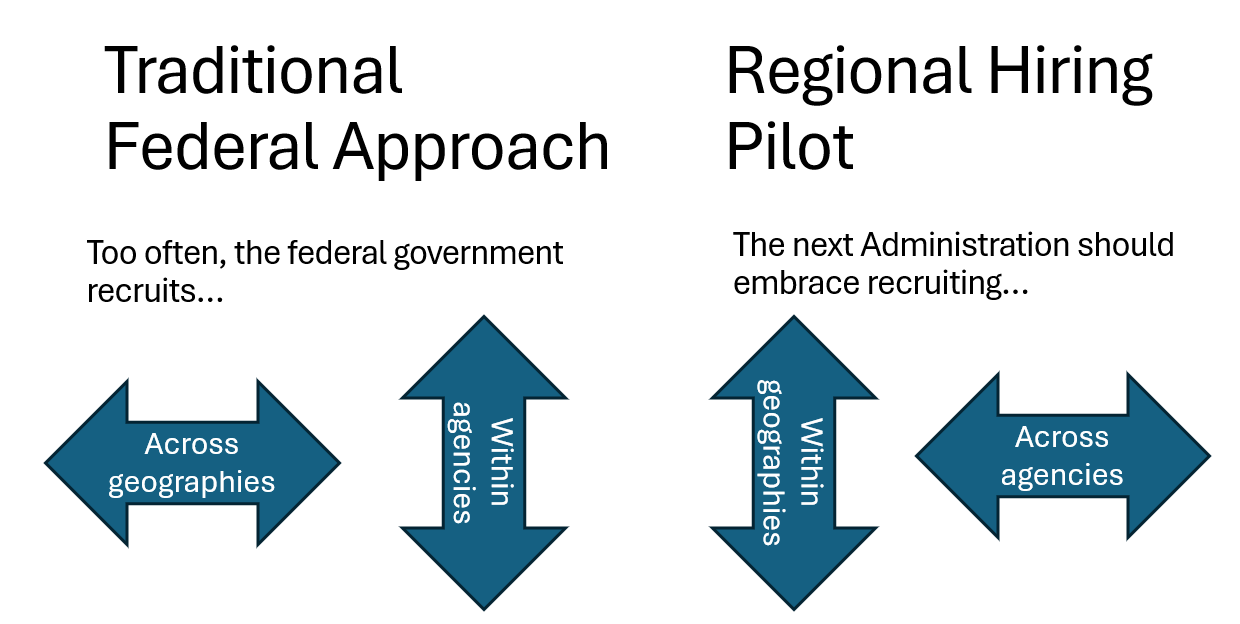

The Federal Government’s hiring needs—already severe across many mission-critical occupations—are likely to remain acute as federal retirements continue, the labor market remains tight, and mission needs continue to grow. Unfortunately, federal hiring is misaligned with how most people approach job seeking. Most Americans search for employment in a geographically bounded way, a trend which has accelerated following the labor market disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, federal agencies tend to engage with jobseekers in a manner siloed to a single agency and across a wide variety of professions.

The result is that the federal government tends to hire agency by agency while casting a wide geographic net, which limits its ability to build deep and direct relationships with talent providers, while also duplicating searches for similar roles across agencies. Instead, the next Administration should align with jobseekers’ expectations by recruiting across agencies within each geography.

By embracing a new approach, the government can begin to develop a more coordinated cross-agency employer profile within regions with significant federal presence, while still leveraging its scale by aggregating hiring needs across agencies. This approach would build upon the important hiring reforms advanced under the Biden-Harris Administration, including cross-agency pooled hiring, renewed attention to hiring experience for jobseekers, and new investments to unlock the federal government’s regional presence through elevation of the Federal Executive Board (FEB) program. FEBs are cross-agency councils of senior appointees and civil servants in regions of significant federal presence across the country. They are empowered to identify areas for cross-agency cooperation and are singularly positioned to collaborate to pool talent needs and represent the federal government in communities across the country.

Plan of Action

The next Administration should embrace a cross-agency, regionally-focused recruitment strategy and bring federal career opportunities closer to Americans through a series of 2-3 large scale, cross-agency recruitment and hiring pilots in geographies outside of Washington, DC. To be effective, this effort will need both sponsorship from senior leaders at the center of government, as well as ownership from frontline leaders who can build relationships on the ground.

Recommendation 1. Provide Strategic Direction from the Center of Government

The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) should launch a small team, composed of leaders in recruitment, personnel policy and workforce data, to identify promising localities for coordinated regional hiring surges. They should leverage centralized workforce data or data from Human Capital Operating Plan workforce plans to identify prospective hiring needs by government-wide and agency-specific mission-critical occupations (MCOs) by FEB region, while ensuring that agency and sub-agency workforce plans consistently specify where hiring will occur in the future. They might also consider seasonal or cyclical cross-agency hiring needs for inclusion in the pilot to facilitate year-to-year experimentation and analysis. With this information, they should engage the FEB Center of Operations and jointly select 2-3 FEB regions outside of the capital where there are significant overlapping needs in MCOs.

As this pilot moves forward, it is imperative that OMB and OPM empower on-the-ground federal leaders to drive surge hiring and equip them with flexible hiring authorities where needed.

Recommendation 2. Empower Frontline Leadership from the FEBs

FEB field staff are well positioned to play a coordinating role to help drive surges, starting by convening agency leadership in their regions to validate hiring needs and make amendments as necessary. Together, they should set a reasonable, measurable goal for surge hiring in the coming year that reflects both total need and headline MCOs (e.g., “in the next 12 months, federal agencies in greater Columbus will hire 750 new employees, including 75 HR Specialists, 45 Data Scientists, and 110 Engineers”).

To begin to develop a regional talent strategy, the FEB should form a small task force drawn from standout hiring managers and HR professionals, and then begin to develop a stakeholder map of key educational institutions and civic partners with access to talent pools in the region, sharing existing relationships and building new ones. The FEB should bring these external partners together to socialize shared needs and listen to their impressions of federal career opportunities in the region.

With these insights, the project team should announce publicly the number and types of roles needed and prepare sharp public-facing collateral that foregrounds headline MCOs and raises the profile of local federal agencies. In support, OPM should launch regional USAJOBS skins (e.g., “Columbus.USAJOBS.gov”) to make it easy to explore available positions. The team should make sustained, targeted outreach at local educational institutions aligned with hiring needs, so all federal agencies are on graduates’ and administrators’ radar.

These activities should build toward one or more signature large, in-person, cross-agency recruitment and hiring fairs, perhaps headlined by a high profile Administration leader. Candidates should be able to come to an event, learn what it means to hold a job in their discipline in federal service, and apply live for roles at multiple agencies, all while exploring what else the federal government has to offer and building tangible relationships with federal recruiters. Ahead of the event, the project team should work with agencies to align their hiring cycles so the maximum number of jobs are open at the time of the event, potentially launching a pooled hiring action to coincide. The project team should capture all interested jobseekers from the event to seed the new Talent Campaigns function in USAStaffing that enables agencies to bucket tranches of qualified jobseekers for future sourcing.

Recommendation 3. Replicate and Celebrate

Following each regional surge, the center of government and frontline teams should collaborate to distill key learnings and conclude the sprint engagement by developing a playbook for regional recruitment surges. Especially successful surges will also present an opportunity to spotlight excellence in recruitment and hiring, which is rarely celebrated.

The center of government team should also identify geographies with effective relationships between agencies and talent providers for key roles and leverage the growing use of remote work and location negotiable positions to site certain roles in “friendly” labor markets.

Conclusion

Regional, cross-agency hiring surges are an opportunity for federal agencies to fill high-need roles across the country in a manner that is proactive and collaborative, rather than responsive and competitive. They would aim to facilitate a new level of information sharing between the frontline and the center of government, and inform agency strategic planning efforts, allowing headquarters to better understand the realities of recruitment and hiring on the ground. They would enable OPM and OMB to reach, engage, and empower frontline HR specialists and hiring managers who are sufficiently numerous and fragmented that they are difficult to reach in the present course of business.

Finally, engaging regionally will emphasize that most of the federal workforce resides outside of Washington, D.C., and build understanding and respect for the work of federal public servants in communities across the nation.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Enhancing Local Capacity for Disaster Resilience

Across the United States, thousands of communities, particularly rural ones, don’t have the capacity to identify, apply for, and manage federal grants. And more than half of Americans don’t feel that the federal government adequately takes their interests into account. These factors make it difficult to build climate resilience in our most vulnerable populations. AmeriCorps can tackle this challenge by providing the human power needed to help communities overcome significant structural obstacles in accessing federal resources. Specifically, federal agencies that are part of the Thriving Communities Network can partner with the philanthropic sector to place AmeriCorps members in Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZs) as part of a new Resilient Communities Corps. Through this initiative, AmeriCorps would provide technical assistance to vulnerable communities in accessing deeply needed resources.

There is precedent for this type of effort. AmeriCorps programming, like AmeriCorps VISTA, has a long history of aiding communities and organizations by directly helping secure grant monies and by empowering communities and organizations to self-support in the future. The AmeriCorps Energy Communities is a public-private partnership that targets service investment to support low-capacity and highly vulnerable communities in capitalizing on emerging energy opportunities. And the Environmental Justice Climate Corps, a partnership between the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and AmeriCorps, will place AmeriCorps VISTA members in historically marginalized communities to work on environmental justice projects.

A new initiative targeting service investment to build resilience in low-capacity communities, particularly rural communities, would help build capacity at the local level, train a new generation of service-oriented individuals in grant writing and resilience work, and ensure that federal funding gets to the communities that need it most.

Challenge and Opportunity

A significant barrier to getting federal funding to those who need it the most is the capacity of those communities to search and apply for grants. Many such communities lack both sufficient staff bandwidth to apply and search for grants and the internal expertise to put forward a successful application. Indeed, the Midwest and Interior West have seen under 20% of their communities receive competitive federal grants since the year 2000. Low-capacity rural communities account for only 3% of grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s flagship program for building community resilience. Even communities that receive grants often lack the capacity for strong grant management, which can mean losing monies that go unspent within the grant period.

This is problematic because low-capacity communities are particularly vulnerable to natural disasters from flooding to wildfires. Out of the nearly 8,000 most at-risk communities with limited capacity to advocate for resources, 46% are at risk for flooding, 36% are at risk for wildfires, and 19% are at risk for both.

Ensuring communities can access federal grants to help them become more climate resilient is crucial to achieving an equitable and efficient distribution of federal monies, and to building a stronger nation from the ground up. These objectives are especially salient given that there is still a lot of federal money available through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) that low-capacity communities can tap into for climate resilience work. As of April 2024, only $60 billion out of the $145 billion in the IRA for energy and climate programs had been spent. For the IIJA, only half of the nearly $650 billion in direct formula funding had been spent.

The Biden-Harris Administration has tried to address the mismatch between federal resilience funding and community capacity in a variety of ways. The Administration has deployed resources for low-capacity communities, agencies tasked with allocating funds from the IRA and IIJA have held information sessions, and the IRA and IIJA contain over a hundred technical assistance programs. Yet there still is not enough support in the form of human capacity at the local level to access grants and other resources and assistance provided by federal agencies. AmeriCorps members can support communities in making informed decisions, applying for federal support, and managing federal financial assistance. Indeed, state programs like the Maine Climate Corps, include aiding communities with both resilience planning and emergency management assistance as part of their focus. Evening the playing field by expanding deployment of human capital will yield a more equitable distribution of federal monies to the communities that need it the most.

AmeriCorps’ Energy Communities initiative serves as a model for a public-private partnership to support low-capacity communities in meeting their climate resilience goals. Over a three-year period, the program will invest over $7.8 million from federal agencies and philanthropic dollars to help communities designated by the Interagency Working Group on Coal & Power Plant Communities & Economic Revitalization on issues revolving around energy opportunity, environmental cleanup, and economic development to help communities capitalize on emerging energy opportunities.

There is an opportunity to replicate this model towards resilience. Specifically, the next Administration can leverage the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA’s) Community Disaster Resilience Zone (CDRZ) designations to target AmeriCorps support to the communities that need it most. Doing so will not only build community resilience, but will help restore trust in the federal government and its programs (see FAQ).

Plan of Action

The next administration can support vulnerable communities in building climate resilience by launching a new Resilient Communities Corps through AmeriCorps. The initiative can be launched through a three-part Plan of Action: (1) find a philanthropic partner to fund AmeriCorps placements in CDRZs, (2) engage federal agencies that are part of the Thriving Communities Network to provide resilience training and support to Corps members, and (3) use the CDRZ designations to help guide where AmeriCorps members should be placed.

Recommendation 1. Secure philanthropic funding

American service programs have a history of utilizing philanthropic monies to fund programming. The AmeriCorps Energy Communities is funded with philanthropic monies from Bloomberg Philanthropies. California Volunteers Fund (CVF), the Waverly Street Foundation, and individual philanthropists helped fund the state Climate Corps. CVF has also provided assistance and insights for state Climate Corps officials as they develop their programs.

A new Resilient Communities Corps under the AmeriCorps umbrella could be funded through one or several major philanthropic donors, and/or through grassroots donations. Widespread public support for AmeriCorps’ ACC that transcends generational and party lines presents the opportunity for new grassroots donations to supplement federal monies allocated to the program along with tapping the existing network of foundations, individuals, companies, and organizations that have provided past donations. The Partnership for the Civilian Climate Corps (PCCC), which has had a history of collaborating with the ACC’s federal partners, would be well suited to help spearhead this grassroots effort.

America’s Service Commissions (ASC), which represents state service commissions, can also help coordinate with state service commissions to find local philanthropic monies to fund AmeriCorps work in CDRZs. There is precedent for this type of fundraising. Maine’s state service commission was able to secure private monies for one Maine Service Fellow. The fellow has since worked with low-capacity communities in Maine on climate resilience. ASC can also work with state service commissions to identify current state, private, and federally funded service programming that could be tapped to work in CDRZs or are currently working in CDRZs. This will help tie in existing local service infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. Engage federal agencies participating in the Thriving Communities Network and the American Climate Corps (ACC) interagency working group.

Philanthropic funding will be helpful but not sufficient in launching the Resilient Communities Corps. The next administration should also engage federal agencies to provide AmeriCorps members participating in the initiative with training on climate resilience, orientations and points of contact for major federal resilience programs, and, where available, additional financial support for the program. The ACC’s interagency working group has centered AmeriCorps as a multiagency initiative that has directed resources and provides collaboration in implementing AmeriCorps programming. The Resilient Communities Corps will be able to tap into this cross-agency collaboration in ways that align with the resilience work already being done by partnership members.

There are currently four ACC programs that are funded through cooperation with other federal agencies. These are the Working Lands Climate Corps with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)’s Natural Resources and Conservation Service, AmeriCorps NCCC Forest Corps with the USDA Forest Service, Energy Communities AmeriCorps with the Department of Interior and the Department of Commerce, and the Environmental Justice Corps, which was announced in September 2024 and will launch in 2025, with the EPA. The Resilient Communities Corps could be established as a formal partnership with one or more federal agencies as funding partners.

In addition, the Resilient Communities Corps can and should leverage existing work that federal agencies are doing to build community capacity and enhance community climate resilience. For instance, USDA’s Rural Partners Network helps rural communities access federal funding while the EPA’s Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers Program provides training and assistance for communities to build the capacity to navigate, develop proposals, and manage federal grants. The Thriving Communities Network provides a forum for federal agencies to provide technical assistance to communities trying to access federal monies. Corps members, through the network, can help federal agencies provide communities they are working with building capacity to access this technical assistance.

Recommendation 3. Use CDRZ designations and engage with state service commissions to guide Resilient Communities Corps placements

FEMA, through its National Risk Index, has identified communities across the country that are most vulnerable to the climate crisis and need targeted federal support for climate resilience projects. CDRZs provide an opportunity for AmeriCorps to identify low-capacity communities that need their assistance in accessing this federal support. With assistance from partner agencies and philanthropic dollars, the AmeriCorps can fund Corps members to work in these designated zones to help drive resources into them. As part of this effort, the ACC interagency working group should be broadened to include the Department of Homeland Security (which already sponsors FEMA Corps).

In 2024, the Biden-Harris Administration announced Federal-State partnerships between state service commissions and the ACC. This partnership with state service commissions will help AmeriCorps and partner agencies identify what is currently being done in CDRZs, what is needed from communities, and any existing service programming that could be built up with federal and philanthropic monies. State service commissions understand the communities they work with and what existing programming is currently in place. This knowledge and coordination will prove invaluable for the Resilient Communities Corps and AmeriCorps more broadly as they determine where to allocate members and what existing service programming could receive Resilient Communities Corps designation. This will be helpful in deciding where to focus initial/pilot Resilient Communities Corps placements.

Conclusion

A Resilient Communities Corps presents an incredible opportunity for the next administration to support low-capacity communities in accessing competitive grants in CDRZ-designated areas. It will improve the federal government’s impact and efficiency of dispersing grant monies by making grants more accessible and ensure that our most vulnerable communities are better prepared and more resilient in the face of the climate crisis, introduce a new generation of young people to grant writing and public service, and help restore trust in federal government programs from communities that often feel overlooked.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Funding for one AmeriCorps member in each of FEMA’s 483 designated Community Disaster Resilience Zones would cost around $14,500,000 per year. This is with an estimate of $30,000 per member. However, this figure will be subject to change due to overhead and living adjustment costs.

There are many communities that could benefit from additional support when it comes to building resilience. Headwater Economics, a research institute in Montana, has flagged that the CDRZ does not account for all low-capacity communities hampered in their efforts to become more climate resilient. But the CDRZ designation does provide a federal framework that can serve as a jumping-off point for AmeriCorps to begin to fill capacity gaps. These designations, identified through the National Risk Index, provide a clear picture for where federal, public and private monies are needed the most. These communities are some of the most vulnerable to climate change, lack the resources for resilience work, and need the human capacity to access them. Because of these reasons, the CDRZ communities provide the ideal and most appropriate area for the Resilient Communities Corps to first serve in.

Funding for national service programming, particularly for the ACC, has bipartisan support. 53% of likely voters say that national service programming can help communities face climate-related issues.

On the other hand, 53% of Americans also feel that the federal government doesn’t take into account “the interests of people like them.” ACC programming, like what Maine’s Climate Corps is doing in rural areas, can help reach communities and build support among Americans for government programs that can be at times met with hostility.

For example, in Maine, the small and politically conservative town of Dover-Foxcroft applied for and was approved to host a Maine Service Fellow (part of the Maine Climate Corps network) to help the local climate action committee to obtain funding for and implement energy efficiency programs. The fellow, a recent graduate from a local college, helped Dover-Foxcroft’s new warming/cooling emergency shelter create policies, organized events on conversations about climate change, wrote a report about how the county will be affected by climate change, and recruited locals at the Black Fly Festival to participate in energy efficiency programs.

Like the Maine Service Fellows, Resilient Communities Corps members will be integral members of the communities in which they serve. They will gather essential information about their communities and provide feedback from the ground on what is working and what areas need improvement or are not being adequately addressed. This information can be passed up to the interagency working groups that can then be relayed to colleagues administering the grants, improving information flow, and creating feedback channels to better craft and implement policy. It also presents the opportunity for representatives of those agencies to directly reach out to those communities to let them know they have been heard and proactively alert residents to any changes they plan on making.

Building Talent Capacity for Permitting: Insights from Civil Servants

Have you ever asked a civil servant in the federal government what it was like to hire new staff? It’s quite common to hear how challenging it is to navigate the hiring process and how long it takes to get someone through the door. At FAS, we know it’s hard. We’ve seen how it works, and we’ve heard stories from civil servants in government.

Following the wave of legislation aimed at addressing infrastructure, environment, and economic vulnerabilities (i.e., the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and the CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS)), we knew that the federal government’s hiring needs were going to soar. As we previously stated, permitting is a common bottleneck that would hinder the implementation of BIL, IRA, and CHIPS. The increase in work following this legislation came in conjunction with a push for faster permits, which in turn significantly increased agency workload. Many agencies did not have the capacity to clear the existing backlogs of permitting projects they already had in their pipeline, which would not even begin to address the new demand that would result from these laws. As such, talent capacity, or having staff with the knowledge and skills needed to meet the work demands, presented a major bottleneck.

We also knew that surge hiring is not a strength of the government, and there are a number of reasons for that; some we highlighted in our recent blog post. It’s a difficult task to coordinate, manage, and support the hiring process for a variety of roles across many agencies. And agencies that are responsible for permitting activities, like environmental reviews and authorizations, do not have standardized roles and team structures to make it easier to hire. Furthermore, permitting responsibility and roles are disaggregated within and across agencies – some roles are permanent, others are temporary. Sometimes responsibility for permitting is core to the job. In other cases, the responsibility is part of other program or regional/state needs. This makes it hard to take concerted and sustained action across government to improve hiring.

While this sounds like a challenge, FAS saw an opportunity to apply our talent expertise to permitting hiring with the aim of reducing the time to hire and improving the hiring experience for both hiring managers and HR specialists. Our ultimate goal was to enable the implementation of this new legislation. We also knew that focusing on hiring for permitting would offer a lens to better understand and solve for systemic talent challenges across government.

As part of this work, we had the opportunity to connect and collaborate with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a broad understanding of the hiring difficulties experienced across permitting agencies. This helped us identify some of the biggest challenges preventing progress, which enabled us to co-host two webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, focused on showcasing tactical solutions that could be applied today to improve hiring processes.

Our team wanted to complement this understanding of the core challenges with voices from agencies – hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders – who have all been involved in the process. We hoped to validate the challenges we heard and identify new issues, as well as capture best practices and talent capacity strategies that had been successfully employed. The intention of this blog is to capture the lessons from our discussions that could support civil servants in building talent capacity for permitting-related activities and beyond, as many solutions identified are broadly applicable across the federal government.

Approach

Our team at FAS reached out to over 55 civil servants who work across six agencies and 17 different offices identified through our hiring webinars to see if they’d be willing to share about their experiences trying to hire for permitting-related roles in the implementation of IRA, BIL, and CHIPS. Through this outreach, we facilitated 14 interviews and connected with 18 civil servants from six different organizations within the Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Defense, Department of Interior, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Department of Commerce. The roles of the participants varied; it included Hiring Managers, HR Specialists, HR Leaders, Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers, and Chief Human Capital Officers.

In our conversations, we focused on identifying their hiring needs to support permitting-related activities within their respective organization, the challenges they experience in trying to hire for those new positions, what practices were successful in their hiring efforts, and any recommendations they had for other agencies. We synthesized the data we gathered through these discussions and identified common challenges in hiring, successful hiring practices, talent capacity strategies, and additional tips for civil servants to consider.

Challenges to Hiring

We identified many challenges hindering agencies from quickly bringing on new staff to fill their open roles. From the start, many teams responsible for permitting were already very understaffed. One interviewee explained that they had serious backlogs requiring complex analysis, but were only able to triage and take on what was feasible. Another shared that they initially were only processing 60% of their workload annually. A third interviewee explained that some of their staff had previously been working on 4-5 Environment Impact Statements (EIS) at one time, which is very high and not common for the field. Their team had a longstanding complaint about high workload that led to a high attrition rate, which only increased the need for more hires. In addition to the permitting teams being under resourced, many HR counterpart teams were also understaffed. This created an environment where teams needed to hire a significant number of new staff, but did not necessarily have the HR support necessary to execute.

The budget was the next issue many agencies faced. The budget constraints resulting from the time-bound funding of IRA and BIL raised a number of important questions for the agencies. BIL funds expire at the end of FY2026 and IRA funds expire anywhere between 2-10 years from the legislation passing in 2022. For example, the funds allocated to the Permitting Council in the IRA expire at the end of FY2031, and some of these funds have been given to agencies to bolster workforce capacity for supporting timely permitting reviews. Ultimately, agencies needed to decide if they wanted to hire temporary or full time employees. This decision cannot be made without additional information and analysis of retirement rates, attrition rates, and other funding sources.

In addition to managing the budgetary constraints, agencies needed to determine how they would allocate the funds provided to their bureaus and programs. This required negotiations, justifications, and many discussions. The ability of Program Leaders to negotiate and justify their allocation is dependent upon their ability to accurately conduct workforce planning, which was a challenge identified through interviews. Specifically, some managers were challenged to accurately plan in an environment that is demand-driven and continuously evolving. Additionally, managing staff who have a variety of responsibilities and may only work on permitting projects for a portion of their time only increases the complexity of the planning process.

A number of challenges we heard were common pain points in the federal government’s hiring process, as noted in Many Chutes and Few Ladders in the Federal Hiring Process. These include:

- Assessments: Inadequate assessments have led to issues with the certificate lists of eligible candidates provided from the HR Specialist to the hiring manager. Some hiring managers have received lists with too many candidates to choose from, while others have been disappointed to not see qualified candidates on the list. This is largely a result of assessments that do not effectively screen qualified applicants. Self-assessments are an example of this, where applicants score their own abilities in response to a series of multiple choice questions. From our conversations, self-assessments are still a commonly used practice, and skills-based assessments have not been widely adopted.

- Job Descriptions: Both creating new and updating job descriptions has caused delays in the hiring process. Some agencies have started moving towards standardized job descriptions with the goal of making the process more efficient, but this has not been an easy task and has required a lot of time for collaboration across a variety of stakeholders.

- Background Checks: Delays in background checks have slowed the process. These delays often result from mistakes in or incomplete Electronic Questionnaires for Investigations Processing (e-QIP) forms, delays in scheduling fingerprint appointments, a lack of infrastructure for sharing and tracking information between key stakeholders (e.g., selected applicant, suitability manager, hiring manager), and delayed responses to notifications in the process.

- Candidate Declinations: Candidates declining a job offer have set a number of agencies back, especially those lacking deep applicant pools. The reasons provided have varied. Some applicants believed that the temporary positions were negotiable or did not realize they had applied to a term position, and they were no longer interested. In some cases, agency hiring managers did not know they had hiring flexibilities or incentives to offer that may have bridged the gap for the candidate. Others were unable to accept the offer for the specific location, citing the increased cost of living and housing prices as a barrier.

Lastly, recruiting was noted as a challenge by a number of participants. Recruiting for a qualified applicant pool has been difficult, especially for those looking to hire very specialized roles. One participant explained their need for someone with experience working in a specific region of the country and the limitations that came with not being able to offer a relocation bonus. Another participant described the difficulty in finding qualified candidates at the right grade level because the pay scale was very limiting for the expertise required. These challenges are exacerbated in agencies that lack recruiting infrastructure and dedicated resources to support recruitment.

These challenges manifested as bottlenecks in the hiring process and present opportunities for improvement. Apart from the new, uncertain funding, these challenges are not novel. Rather, these are issues agencies have been facing for many years. The new legislation has drawn broader attention back to these problems and presents an opportunity for action.

Successful Hiring Practices

Despite these bottlenecks, participants shared a number of practices they employed to improve the hiring process and successfully bring new staff onboard. We wanted to share seven (7) practices that could be adopted by civil servants today.

Establish Hiring Priority and Gain Leadership Support

One agency leveraged the Biden-Harris Permitting Action Plan to establish and elevate their hiring needs. Following the guidance shared by OMB, CEQ, and the Permitting Council, this agency set out to develop an action plan that would function as a strategic document over the next few years. They employed a collaborative approach to develop their plan. The Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officer (CERPO) and Deputy CERPO, the roles responsible for overseeing environmental review and permitting projects within their agencies and under their jurisdiction, brought together a team of NEPA Specialists and other staff engaged in environmental reviews and permitting across their organizations with equities. This group collectively brainstormed what they could do to strengthen and streamline permitting and environmental reviews at their agency. From this list, they prioritized five key focus areas for the first phase of their plan. This included hiring as the highest priority because it had been identified as a critical issue. Given their positioning within the organization and the Administration’s mandate, they were able to gain the support of the Secretary, and as a result, escalate their hiring needs to fill over 30 open positions over the course of FY24.

Collaborate and Share Across the Organization

Sharing and collaborating across the agency helped many expedite the hiring process. Here are examples that highlight the importance of this for success.

(1) One agency described how they share position descriptions across the enterprise. They have a system that allows any hiring manager to search for a similar position that they could use themselves or refine for their specific role. This reduces the time spent by hiring managers recreating positions.

(2) Another agency explained how they created an open tracking tool of positions they were interested in hiring across the organization. This tool allowed hiring managers across the agency to share the positions they wanted to hire. The initial list included 300 potential positions; it allowed them to prioritize and identify opportunities for collaboration. By leveraging shared certificates, they were able to reduce duplication. This tool evolved into an open repository of positions the organization was looking to recruit and a timeline for when they would be recruiting for those roles. Once announcements were closed, they would share the certificate lists widely to hiring managers.

(3) In another example, the participant explained how they facilitated ongoing collaboration between the CERPO, CHCO, HQ, and both HR and Program Leads from each relevant bureau to drive forward the hiring process. They initially worked with the Program Leads from the key bureaus impacted to identify their hiring needs and discuss the challenges they were facing. Then they reached out to the CHCO to engage them and share their priority hiring needs and worked to bring in each bureau’s respective HR teams to provide technical assistance. With everyone engaged, they set up a regular check-in to discuss progress, and the group collaborated to develop and classify position descriptions for the open positions. Later once candidates had been selected, they collaborated with operations to prioritize their hires in suitability. This ultimately saved time and streamlined the process.

Improve Hiring Processes

Participants described improving hiring processes within their organization through a variety of approaches. One method that we heard numerous times is standardizing job descriptions across the enterprise to reduce duplicative job revision and classification efforts and support the use of shared certifications. One agency approached this by facilitating focus groups with key stakeholders to define the non-negotiable and “nice to have” duties for the role. These sessions included classifiers, domain specialists, leadership, and data analysts. They found that when the group started discussing the knowledge and skills that really mattered, they were able to understand why combining efforts would help them achieve their goals more quickly. They realized that some of the minute details (e.g., expertise in Atlantic Salmon) did not need to be in the position description and rather could be deduced through the interview process. While this took a great deal of buy in and leadership support, they were successful in standardizing some position descriptions.

Other methods for improving hiring processes included standardizing the process for establishing pay to reduce competition across the agency, setting a 30-day time limit for making selections, setting applicant limits for closing job announcements, and using data to drive improvements. In one interview with an agency’s HR team, we learned about their role in collecting and analyzing data in each step of the hiring process (e.g., overall hiring time, time at each step, etc.). They use this information to monitor progress, track performance, understand which incentives are being employed, and identify opportunities for improvement in the overall process. This data helps inform their decisions and allows them to identify where they need to provide more support.

Leverage Position and Recruiting Incentives

Multiple participants described using incentives to make a position more attractive to a candidate and encourage the acceptance of a job offer. Multiple agencies offered remote and hybrid positions where possible, which they cited as generating more interest in the role. One HR team shared how they employ a series of OPM approved recruiting incentives to make positions more compelling. These included starting bonuses, student loan repayment, credit for industry work, advanced leave, higher step options, relocation bonuses, and additional leave time. They find these incentives to be particularly helpful when the location requires a far move (e.g., Alaska, Hawaii) or is difficult to hire into for whatever reason.

Leverage Hiring Flexibilities

Multiple agencies cited using different hiring flexibilities to hire for their open positions and remove some of the barriers embedded in the competitive service hiring process. The flexibilities included, Direct Hire Authority, Schedule A, Pathways Programs, retired annuitants, internship conversions, internal detailees, Presidential Innovation Fellows via GSA, Digital Service Fellows Program, as well as contract staff to support IT development. Many agencies also hired for term or temporary positions that ranged from three to 10 years, depending on the additional funding sources that could be found. Employing these authorities helped to streamline the hiring process.

Seek HR Recruiting Support

One agency described how their HR office supported and collaborated with hiring managers throughout the hiring process, especially in bolstering their recruitment efforts. One HR team helped lead recruitment outreach, sharing their open positions on a variety of media in coordination with their communications team (i.e., their website, facebook, instagram). They also developed standard language for hiring managers to share with their networks that highlighted information about the role and mistakes to avoid when applying. This helped relieve the pressure on the hiring manager to lead the recruiting effort.

Invest in Dedicated HR Staff to Manage and Support Permitting Hiring

Multiple agencies shared how they hired a dedicated resource to oversee the hiring process for their organization. One agency hired a retired annuitant (i.e., someone who retired from working in the federal government and is rehired) to help manage the organization’s hiring process after they realized that they were making minimal progress against their hiring needs. This individual returned to the government workforce and brought a deep understanding of government hiring. They collaborated with the HR Specialists and hiring managers to develop position descriptions, organize procurement packages, schedule interviews, and support the applicant selection process. They said, “we would not have been able to do any of the 40 hires without this person.”

Another agency described how they detailed someone to manage BIL and IRA hiring requests across their organization. This person was situated outside of HR, and they were responsible for tracking the end-to-end hiring and recruitment efforts. They maintained a repository of the positions each office needed to recruit and generated weekly reports on BIL and IRA hiring efforts that highlighted how many positions are open, how many are closed, and where certificate lists are available. This allowed the broader team to identify how they could drive progress.

While there were a number of challenges, many participants described successfully hiring 15-30+ new employees over the last year alone. One agency in particular described hiring over 2,000 people in 2024 for the IRA, which was an all time high for their organization. These seven practices have enabled agencies to be successful in filling new positions to support permitting-related activities, and they can be applied to other hiring needs as well. Any future talent surge in the federal government could benefit from adopting these hiring practices.

Solutions to Build Talent Capacity

While the majority of the interviews focused on hiring due to concerns of understaffed teams and the new funding availability, there are many other ways to build talent capacity in government. Some of the participants we interviewed shared other strategies they employed to address high workload demands, which present opportunities for other agencies to consider, especially as we move into the new administration. Here are six (6) strategies for building workforce capacity.

Establish Strike Teams

During our conversations, two different agencies described creating a strike team, or making an investment in additional, flexible staff, to provide supplemental capacity where there is insufficient staff for the current demand. One organization accomplished this by hiring project managers with NEPA expertise into their CERPO Office. These Project Managers could then be detailed out to specific bureaus to fill capacity gaps and provide management for high priority, multi-agency projects. This helped fill immediate capacity gaps, as teams were continuing to hire.

Another agency piloted a relief brigade, or a pool of Headquarters (HQ) staff who could be detailed to support regional staffing needs on large projects, consultations, and backlogs with temporary funding. This team was formed from a national perspective and aimed to reduce the pressure on each region and center. Based on this organization’s needs, the team was composed of natural resource management and biological science generalists. Participants shared that some efficiencies have been gained, but there was a substantial learning curve that required training and learning on the job. One hiring manager stated, the “relief brigade is the permanent embodiment of what we need more of.” These types of teams can help address dynamic capacity needs and provide more flexibility to the organization more broadly.

Conduct Bottom Up Workforce Analysis

One Program Manager shared their experience joining a new team and conducting workforce analysis to quantify their staffing needs and inform strategic decisions for their organizational structure. In their initial discussions with staff, they learned that many employees were feeling overworked and capacity was a major concern. To understand the need, they conducted a bottom up workforce analysis to estimate the office’s workload and identify gaps. This involved gathering project data from the past two years, identifying the average time frame by activity type and NEPA category, the staff hours needed to accomplish the work, and the delta between existing and needed staff hours. This data provided evidence of capacity gaps, which they were able to bring to their senior leadership to advocate and secure approval for a team expansion. This analysis enabled them to make data informed decisions about hiring that would reduce the overall workload of staff and ultimately increase staff morale and improve retention rates, which had been a concern. This approach can serve as a model for other agencies who have had difficulty in workforce planning.

Reorganize Team to Drive Efficiencies

The Program Manager who conducted bottom-up workforce analysis applied this new understanding of the work and the demands to reorganize their team to drive efficiencies and share the workload. They established three branches in their team and added four supervisory roles. The branches included one NEPA Branch, one Archeological Branch, and a Program and Policy Branch, and a supervisor was established for each. An additional leadership Deputy role was created to focus on overseeing their programs and coordinating on integration points with relevant agencies.

With this shift, they created new processes and roles to support continuous improvements and fill outstanding duties. Specifically, the Program and Policy Branch is designed to be more proactive, support throughput, and build programmatic and tribal agreements. They added an environmental trainer who is responsible for educating both internal staff and external stakeholders. Two Environmental Protection Specialists now oversee project intake, collaborate with applicants to ensure the applications are complete, manage applicant communications, and then distribute the projects to the assigned owner. A GIS Program Manager was added to the team to support data and analytics. Their role is to identify process delays and their causes, analyze points of failure, and create a geological database to understand where there are project overlaps to expedite and streamline processes. In addition to these internal changes, the Program Manager has also brought on additional contractors to provide greater capacity.

These changes have significantly increased their team’s capacity and has over doubled the number of projects they are able to complete in a year, from 400 projects two years ago to over 900+ projects this year.

Reallocate Work Across Offices and Regions

Numerous participants described work reallocation as a solution to addressing some of their capacity gaps. For example, when one agency was struggling to hire people in a particular location due to the high cost of living, they redistributed the work to another region in the country, where the cost of living was lower. This made it easier to hire into the position. Another HR Leader described supporting their overcapacity teams by redistributing hiring efforts from one office to another in the same region. The original office had minimal bandwidth, while the other had capacity, so they were able to help post the job announcement for the region. They explained the importance of encouraging local offices to help one another deliver, when appropriate.

Others described the reallocation of staff and projects to different regions. This not only allows the organization to match staff with demand, but it also allows for staff to gain experience and knowledge working on a new topic or in a new region. For example, most offshore wind projects are located in the greater Atlantic region, but these projects are gaining traction in the Pacific, so they assigned staff to work in the Atlantic region with the goal of building experience and gaining lessons learned to apply to future Pacific projects. One of these participants emphasized the value and efficiencies that could be derived from developing staff to have more interagency and interservice experience. These examples highlight how leaders can be creative in addressing workload gaps by strategically reallocating work to pair capacity and demand.

Invest in Recruiting Networks

One agency stood out as being an exemplar for their recruiting efforts, which have the potential to be replicated across agencies. They have spent significant time and effort investing in building out their recruitment networks and engaging in career fairs to hire talent. Their organization has been building a repository of potential candidates that is maintained in a system to capture candidate information, educational background, contact information, locations of interest, areas of interest, and remote and relocation preferences. This has been used to generate a list of potential candidates for hiring managers.

They have made connections through affinity groups, communities of practice, and social media. They’ve also built many partnerships with schools and organizations and have a calendar of events (e.g., career fairs) that they attend over the course of the year. At some events, they’ll have their HR team facilitate breakout sessions to discuss the benefits of working at their organization. To make sure they’re getting diverse candidates, they are continuously reaching out to new sources and potential candidate pools.

In addition to engaging in others’ events, they have hosted their own career fair, where they hired about 200 people. Prior to the event, they reviewed and vetted resumes to know who might be a qualified candidate for a position. With Direct Hire Authority for some of their positions, this allowed hiring managers to interview candidates at the fair and immediately make temporary job offers to attendees. HR staff also worked with the hiring managers at the career fair. This infrastructure sets hiring managers up for success and enables them to easily tap into a variety of networks to find qualified candidates.

Invest in Hiring Manager Training

One agency’s training and support for hiring managers can serve as a model for other HR teams to learn from. This agency offers a robust toolkit for supporting hiring managers through the hiring process. While the Supervisor is ultimately responsible for the hiring, the HR team ensures that they have the tools needed to execute and are equipped to be successful. These tools include:

- Handouts on HR highlights to ensure key information is simple and clear;

- Videos on Recruitment, Relocation, and Retention Incentives and Direct Hire Authority, which are posted on their website for all employees to access;

- Annual talent acquisition workshops in-person and virtually to hear from speakers and discuss recruitment and marketing strategies; and

- A Train-the-Trainer program on how to have recruitment conversations.

In addition to these tools and training, HR Specialists work with hiring managers to coach them on how to determine the duties for their open position, especially if they need to re-announce a position multiple times. They are also developing a new marketing strategy centered on everyone being a recruiter. This strategy will result in a new resource to support all staff in recruiting and retaining staff based on their needs.

Another participant identified this as a key opportunity. “Agencies need to educate hiring managers on those processes and what’s out there and available to them… [hiring managers need to] utilize those tools and work with HR to get the best candidates.” This agency’s approach empowers hiring managers to navigate the process, leverage incentives, and successfully recruit.

Establish Apprenticeship Programs

One participant highlighted the need for apprenticeship programs in their permitting work. Short-term or summer internship programs present difficulties with early career staff because there is not enough time for the interns to learn. They explained that it takes about six months for a new employee to become independent. Given this need, they have invested in a 1-year internship program through GeoCorps America. This duration provides interns with the time needed to learn on-the-job through practice, understand the laws and regulations, and gain exposure to the work (e.g., problem solving and stakeholder communication). This program has been successful in creating a pipeline of early career talent; 12 of their interns have moved into permanent federal service positions at different agencies (i.e., DOI, USFS, USGS, and BLM). This type of apprenticeship program could serve as a model for developing early career talent that can be trained on the job and build expertise to take on more complex projects as they grow.

These strategies offer a few examples for how agencies could build workforce capacity. These strategies do not necessarily require bringing on new talent, but rather finding opportunities to improve their internal processes to drive efficiencies and build a more dynamic, flexible workforce to respond to new demand.

Other Considerations

At the end of our interviews, we asked participants if they had any tips or recommendations that they’d want to share with others looking to hire in the government. Here are a few things we heard that we have not already captured in our best practices or talent capacity strategies.

- Always Be Recruiting: Everyone is a recruiter, and you should always be building relationships and connections, being present at events even if you do not have any active job announcements.

- Maintain Communication with Candidates: Stay in touch with potential candidates before there is a job open, while recruiting, and throughout the entire hiring process. This can keep them engaged and help you ultimately receive a job acceptance.

- Invest in Suitability Case Management: Invest in a case management system that sends automatic notifications to each user (i.e., hiring manager, HR specialist, applicant, suitability team) when an action is required. This will streamline the process and ensure that no cases slip through the cracks.

- Cast a Wide Net: Invest in a wide distribution for your job announcements, interview as many qualified people as you can, and identify multiple candidates that you would like to hire, in case someone declines. Also, leave the announcement open for longer, and if you have large offices with continuous turnover, consider keeping a job open on USAJobs, where you can always accept resumes.

- Keep Certificate Lists Open: Keep certificate lists open for a long time, so if a candidate declines, you can return to the list of potential candidates. If it is a shared certificate, then this can also assist your colleagues in quickly finding qualified candidates to interview and hire.

- Regularly Update Position Descriptions: Update your position descriptions to accurately capture the duties of the role and to align with any updated technology. Many agencies have policies for how regularly position descriptions need to be updated, but many question how well these guidelines are followed.

- Listen to Your Staff’s Plans: Engage with your staff on a regular basis and pay attention to who says they may retire or leave in the next year. This will allow you to more proactively plan and predict your future staffing needs.

Hiring into the federal government is not easy – you will very likely experience challenges even if you follow the practices and strategies highlighted here. However, there are things you can do to set yourself up for success in the future and strategies you can use to address workload demands even if you are not currently hiring. This permitting hiring surge has offered an opportunity to learn how you can effectively hire people into the federal workforce, which can serve as an example for future talent surges. Within the permitting space itself, these strategies have proven successful in supporting more timely and efficient reviews. Bolstering workforce capacity has enabled more effective mission execution.

Fixing Impact: How Fixed Prices Can Scale Results-Based Procurement at USAID

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) currently uses Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee (CPFF) as its de facto default funding and contracting model. Unfortunately, this model prioritizes administrative compliance over performance, hindering USAID’s development goals and U.S. efforts to counter renewed Great Power competition with Russia, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and other competitors. The U.S. foreign aid system is losing strategic influence as developing nations turn to faster and more flexible (albeit riskier) options offered by geopolitical competitors like the PRC.

To respond and maintain U.S. global leadership, USAID should transition to heavily favor a Fixed-Price model – tying payments to specific, measurable objectives rather than incurred costs – to enhance the United States’ ability to compete globally and deliver impact at scale. Moreover, USAID should require written justifications for not choosing a Fixed-Price model, shifting the burden of proof. (We will use “Fixed-Price” to refer to both Firm Fixed Price Contracts and Fixed Amount Award Grants, wherein payments are linked to results or deliverables.)

This shock to the system would encourage broader adoption of Fixed-Price models, reducing administrative burdens, incentivizing implementers (of contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants) to focus on outcomes, and streamlining outdated and inefficient procurement processes. The USAID Bureau for Management’s Office of Acquisition and Assistance (OAA) should lead this transition by developing a framework for greater use of Firm Fixed Price (FFP) contracts and Fixed Amount Award (FAA) grants, establishing criteria for defining milestones and outcomes, retraining staff, and providing continuous support. With strong support from USAID leadership, this shift will reduce administrative burdens within USAID and improve competitiveness by expanding USAID’s partner base and making it easier for smaller organizations to collaborate.

Challenge and Opportunity

Challenge

The U.S. remains the largest donor of foreign assistance around the world, accounting for 29% of total official development assistance from major donor governments in 2023. Its foreign aid programs have paid dividends over the years in American jobs and economic growth, as well as an unprecedented and unrivaled network of alliances and trading partners. Today, however, USAID has become mired once again in procurement inefficiencies, reversing previous trends and efforts at reform and blocking – for years – sensible initiatives such as third country national (TCN) warrants, thereby reducing the impact of foreign aid for those it intends to help and impeding the U.S. Government’s (USG) ability to respond to growing Great Power Competition.

Foreign aid serves as a critical instrument of foreign policy influence, shaping geopolitical landscapes and advancing national interests on the global stage. No actor has demonstrated this more clearly than the PRC, whose rise as a major player in global development adds pressure on the U.S. to maintain its leadership. Notably, China has increased its spending of foreign assistance for economic development by 525% in the last 15 years. Through the Belt & Road Initiative, its Digital Silk Road, alternative development banks, and increasingly sophisticated methods of wielding its soft power, the PRC has built a compelling and attractive foreign assistance model which offers quick, low-cost solutions without the governance “strings” attached to U.S. aid. While it seems to fulfill countries’ needs efficiently, hidden costs include long-term debt, high lifecycle expenses, and potential Chinese ownership upon default.

By contrast, USAID’s Cost-Plus-Fixed-Fee (CPFF) foreign assistance model – in which implementers are guaranteed to recover their costs and earn a profit – mainly prioritizes tracking receipts over achieving results and therefore often fails to achieve intended outcomes, with billions spent on programs that lack measurable impact or fail to meet goals. Implementers are paid for budget compliance, regardless of results, placing all performance risk on the government.

The USG invented CPFF to establish fair prices where no markets existed. However, its use has now extended far beyond this purpose – including for products and services with well-established commercial markets. The compliance infrastructure necessary to administer USAID awards and adhere to the documentation/reporting requirements favors entrenched contractors – as noted by USAID Administrator Samantha Power – stifles innovation, and keeps prices high, thereby encumbering America’s ability to agilely work with local partners and respond to changing conditions. (Note: USAID typically uses “award” to refer to contracts, cooperative agreements, and grants. We use “award” in this same manner to refer to all three procurement mechanisms. We use “Fixed-Price Awards” to refer to fixed-price grants and contracts. “Fixed Amount Awards,” however, specifically refers to a fixed-price grant.)

In light of the growing Great Power Competition with China and Russia – and threats by those who wish to undermine the US-led liberal international order – as well as the possibility of further global shocks like COVID-19 or the war in Ukraine, USAID must consider whether its current toolset can maintain a position of strategic strength in global development. Furthermore, amid declining Official Development Assistance (ODA) – 2% year-over-year – and a global failure to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is critical for USAID to reconcile the gap between its funding and lack of results. Without change, USAID funding will largely continue to fall short of objectives. The time is now for USAID to act.

Opportunity

While USAID cannot have a de jure default procurement mechanism, CPFF has become the de facto default procurement mechanism, but it does not have to be. USAID has other mechanisms to deploy funding at its disposal. In fact, at least two alternative award and contract pricing models exist:

- Time and materials (T&M): The implementer proposes a set of fully loaded (i.e., inclusive of salary, benefits, overhead, plus profit) hourly rates for different labor categories and the USG pays for time incurred – not results delivered.

- Fixed-Price (Firm Fixed Price, FFP, for contracts, or Fixed Amount Award, FAA/Fixed Obligation Grants, FOG, for grants): The implementer proposes a set fee and is paid for milestones or results (not receipts).

While CPFF simply reimburses providers for costs plus profit, the Fixed-Price alternatives tie funding to achieving milestones, promoting efficiency and accountability. The Code of Federal Regulations (§ 200.1) permits using Fixed-Price mechanisms whenever pricing data can establish a reasonable estimate of implementation costs.

USAID has acknowledged the need to adapt funding mechanisms to better support local and impact-driven organizations and enhance cost-effectiveness. USAID has already started supporting these goals by incorporating evidence-based approaches and transitioning to models that emphasize cost-effectiveness and impact. As an example, in the Biden administration, USAID’s Office of the Chief Economist (OCE) issued the Promoting Impact and Learning with Cost-Effectiveness Evidence (PILCEE) award, which aims to enhance USAID’s programmatic effectiveness by promoting the use of cost-effectiveness evidence in strategic planning, policy-making, activity design, and implementation. Progress, though, remains limited. Funding disbursed based on performance milestones has remained unchanged since Fiscal Year (FY) 2016. In FY 2022, Fixed Amount Awards represented only 12.4% of new awards, or 1.4% by value.

An October 2020 Stanford Social Innovation Review article by two USAID officials argued that the Agency could enhance its use of Fixed Amount Awards by promoting “performance over compliance”. Other organizations have already begun to make this shift: the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria – among others – have invested in increasing results-based approaches and embedding different results-based instruments into their procurement processes for increased aid effectiveness.

To shift USAID into an Agency that invests in impact at scale, we propose going one step further, and making Fixed-Price awards the de facto default procurement mechanism across USAID by requiring procurement officials to provide written justification for choosing CPFF.

This would build on the work completed during the first Trump administration under Administrator Mark Green, including the creation of the first Acquisition and Assistance Strategy, designed to “empower and equip [USAID] partners and staff to produce results-driven solutions” by, inter alia, “increasing usage of awards that pay for results, as opposed to presumptively reimbursing for costs”, and the promotion of the Pay-for-Results approach to development.

Such a change would unlock benefits for both the USG and for global development, including:

- Better alignment of risk and reward by ensuring implementers are paid only when they deliver on pre-agreed milestones. The risk of not achieving impact would no longer be solely borne by the USG, and implementers would be highly incentivized to achieve results.

- Promotion of a results-driven culture by shifting focus from administrative oversight to actual outcomes. By agreeing to milestones at the start of an award, USAID would give implementers flexibility to achieve results and adapt more nimbly to changing circumstances and place the focus on performing and reporting results, rather than administrative reporting.

- Diversification of USAID’s partner base by reducing the administrative burden associated with being a USAID implementer. This would allow the Agency to leverage the unique strengths, contextual knowledge, and innovative approaches of a diverse set of development actors. By allowing the Agency to work more nimbly with small businesses and local actors on shared priorities, it would further enhance its ability to counter current Great Power Competition with China and Russia.

- Incentivization of cost efficiency, motivating implementers to reduce expenses if they want to increase their profits, without extra cost to the USG.

- Facilitation of greater progress by USAID and the USG toward the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in ways likely to attract more meaningful and substantive private sector partnerships and leverage scarce USG resources.

Plan of Action

Making Fixed-Price the de facto default option for both grants and contracts would provide the U.S. foreign aid procurement process a necessary shock to the system. The success of such a large institutional shift will require effective change management; therefore, it should be accompanied with the necessary training and support for implementing staff. This would entail, inter alia, establishing a dedicated team within OAA specialized in the design and implementation of FFPs and FAAs; and changing the culture of USAID procurement by supporting both contracting and programming staff with a robust change management program, including training and strong messaging from USAID leadership and education for Congressional appropriators.

Recommendation 1. Making Fixed-Price the de facto “default” option for both grants and contracts, and tying payments to results.

Fixed-Price as the default option for both grants and contracts would come at a low additional cost to USAID (assuming staff are able to be redistributed). The Agency’s Senior Procurement Executive, Chief Acquisition Officer (CAO), and Director for OAA should first convene a design working group composed of representatives from program offices, technical offices, OAA, and the General Counsel’s office tasked with reviewing government spending by category to identify sectors exempt from the “Fixed-Price default” mandate, namely for work that lacks deep commercial markets (e.g., humanitarian assistance or disaster relief). This working group would then propose a phased approach for adopting Fixed-Price as the default option across these sectors. After making its recommendations, the working group would be disbanded and a more permanent dedicated team would carry this effort forward (see Recommendation 2).

Once reset, Contract and Agreement Officers would justify any exceptions (i.e., the choice of T&M or CPFF) in an explanatory memo. The CAO could delegate authority to supervising Contracting Officers or other acquisition officials to approve these exceptions. To ensure that the benefits of Fixed-Price results-based contracting reach all levels of awardees, this requirement should become a flow-down clause in all prime awards. This will require additional training for the prime award recipient’s own overseers.

Recommendation 2. Establishing a dedicated team within USAID’s OAA, or the equivalent office in the next administration, specialized in the design and implementation of FFPs and FAAs.

To facilitate a smooth transition, USAID should create a dedicated team within OAA specialized in designing and implementing FFPs and FAAs using existing funds and personnel. This team would have expertise in the choices involved in designing Fixed-Price agreements: results metrics and targets, pricing for results, and optimizing payment structures to incentivize results.

They would have the mandate and resources necessary to support expanding the use of and the amount of funding flowing through high-quality FFPs and FAAs. They would jumpstart the process and support Acquisition and Program Officers by developing guidelines and procedures for Fixed-Price models (along with sector-specific recommendations), overseeing their design and implementation, and evaluating effectiveness. As USAID will learn along the way about how to best implement the Fixed-Price model across sectors, this team will also need to capture lessons learned from the initial experiences to lower the costs and increase the confidence of Acquisition and Assistance Officers using this model going forward.

Recommendation 3. Launching a robust change management program to support USAID acquisition, assistance, program, and legislative and public affairs staff in making the shift to Fixed-Price grant and contract management.

Successfully embedding Fixed-Price as the default option will entail a culture shift within USAID, requiring a multi-faceted approach. This will include the retraining of Contracts and Agreements Officers and their Representatives – who have internalized a culture of administrative compliance and been evaluated primarily on their extensive administrative oversight skills – and promoting a reorganization of the culture of Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning (MEL) and Collaboration, Learning and Adaptation (CLA) to prioritize results over reporting. Setting contracting and agreements staff up for success requires capacity building in the form of training, toolkits, and guidelines on how to implement Fixed-Price models across USAID’s diverse sectors. Other USG agencies make greater use of Fixed-Price awards, and alternative training for both government and prime contractor overseers exists. OAA’s Professional Development and Training unit should adapt existing training from these other agencies, specifically ensuring it addresses how to align payments with results.

Furthermore, the broader change management program should seek to create the appropriate internal incentive structure at the Agency for Acquisition and Assistance staff, motivating and engaging them in this significant restructuring of foreign aid. To succeed at this, the mandate for change needs to come from the top, reassuring staff that the Fixed-Price model does not expose individuals, the Agency, or implementers to undue legal or financial liability.

While this change will not require a Congressional Notification, the Office of Legislative & Public Affairs (LPA) should join this effort early on, including as part of the design working group. LPA would also play a guiding role in both internal and external communications, especially in educating members of Congress and their staffs on the importance and value of this change to improve USAID effectiveness and return on taxpayer dollars. Entrenched players with significant investments in existing CPFF systems will resist this effort, including with political lobbying; LPA will play an important role informing Congress and the public.

Conclusion

USAID’s current reliance on CPFF has proven inadequate in driving impact and must evolve to meet the challenges of global development and Great Power Competition. To create more agile, efficient, and results-driven foreign assistance, the Agency should adopt Fixed-Price as the de facto default model for disbursing funds, prioritizing results over administrative reporting. By embracing a results-based model, USAID will enhance its ability to respond to global shocks and geopolitical shifts, better positioning the U.S. to maintain strategic influence and achieve its foreign policy and development objectives while fostering greater accountability and effectiveness in its foreign aid programs. Implementing these changes will require a robust change management program, which would include creating a dedicated team within OAA, retraining staff and creating incentives for them to take on the change, ongoing guidance throughout the award process, and education and communication with Congress, implementing partners, and the public. This transformation is essential to ensure that U.S. foreign aid continues to play a critical role in advancing national interests and addressing global development challenges.