How Government Cuts Could Impact Your Right to Information

Recent CNN reporting on the Trump administration’s firing of personnel handling Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) sparks concern over the future of the FOIA system. This move by the administration puts a system that is already strained by lack of staff and funding at even further risk, and raises the question of whether other FOIA officers across the federal service are safe or if more will be fired in the coming days.

Signed into law in 1967, the Freedom of Information Act is one of the crowning achievements of government transparency in the United States. It gives the public the right to request federal government records, representing decades of advocacy centered around the idea that a government should be transparent and accountable to its people. Under FOIA, any record from any federal agency is subject to being disclosed with the exceptions for national security, foreign policy, private, and legal proceedings. This provides journalists, researchers, civic society, and the wider public with valuable insights into how their government is executing its obligations. Since its creation, FOIA requests have been used to reveal information that exposes wasteful government spending, threats to public health and safety, excessive secrecy, and more. Based on the First Amendment’s fundamental freedom of the press, FOIA acknowledges the right to access government places and papers.

Among the Department of Government Efficiency’s (DOGE) ongoing purge of thousands of federal employees, members of OPM’s “privacy team,” as well as staff responsible for FOIA requests at OPM, have been fired, according to familiar sources who spoke with CNN.

At FAS, our teams have used FOIA and declassification reviews for decades as a means of increasing transparency and holding the government accountable. This work has led to the declassification of the size and history of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and the discovery of inadequate security at nuclear weapons storage sites.

Steven Aftergood, former director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, is a long-term FOIA practitioner. In 1997, Aftergood was a plaintiff in a FOIA lawsuit against the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), resulting in the declassification of the CIA budget for the first time in 50 years.

The current legislative design of FOIA “fails to balance supply and demand,” Aftergood said in a conversation with FAS staff about the recent firings at OPM, and how firing FOIA officers will further strain an already overburdened and under-resourced process. ”Requesters can easily generate high volumes of requests that overwhelm an agency’s ability to respond. Nor does Congress reliably provide the resources that are needed to meet the demand. Breakdowns and mutual frustration are the predictable result.”

FOIA requires that agencies reply with a determination to valid requests within 20 business days, but many agencies can’t keep up with requests. While FOIA applies to all agencies, each agency implements it differently. For example, according to the Government Accountability Office, total government backlogs of FOIA requests surpassed 200,000 in 2022.

“Some agencies respond to FOIA requests diligently and promptly. That has been my experience with the US Patent and Trademark Office, for example,” said Aftergood. “Some agencies barely comply with the law at all, allowing requests to linger for years or even a decade and more. The US Air Force is notorious in this respect.”

In an era of such massive sweeps upending federal programs, increased transparency is even more important to provide the public with the knowledge necessary to respond and hold the government accountable. Now is the time to bolster and improve the FOIA process, not to fire those who are working–with already limited resources–to hold it together. In order to ensure the transparency of government actions required for a democratic society, Congress should reform FOIA, directing further funding to equip trained personnel with the resources they need. To assist in evaluating agency needs, the Project on Government Oversight suggests agencies include a line-item FOIA budget during the appropriation request process.

For 58 years, FOIA has put power and knowledge directly in the hands of the people. Any erosion of transparency mechanisms such as FOIA–whether by direct abolishment or de-prioritization that leads to eventual decay–sets a concerning precedent. The Trump administration should reverse the firing of FOIA officers at OPM and allocate increased funding for FOIA personnel across the federal service.

New Environmental Assessment Reveals Fascinating Alternatives to Land-Based ICBMs

A new Air Force environmental assessment reveals that it considered basing ICBMs in underground railway tunnels––or possibly underwater.

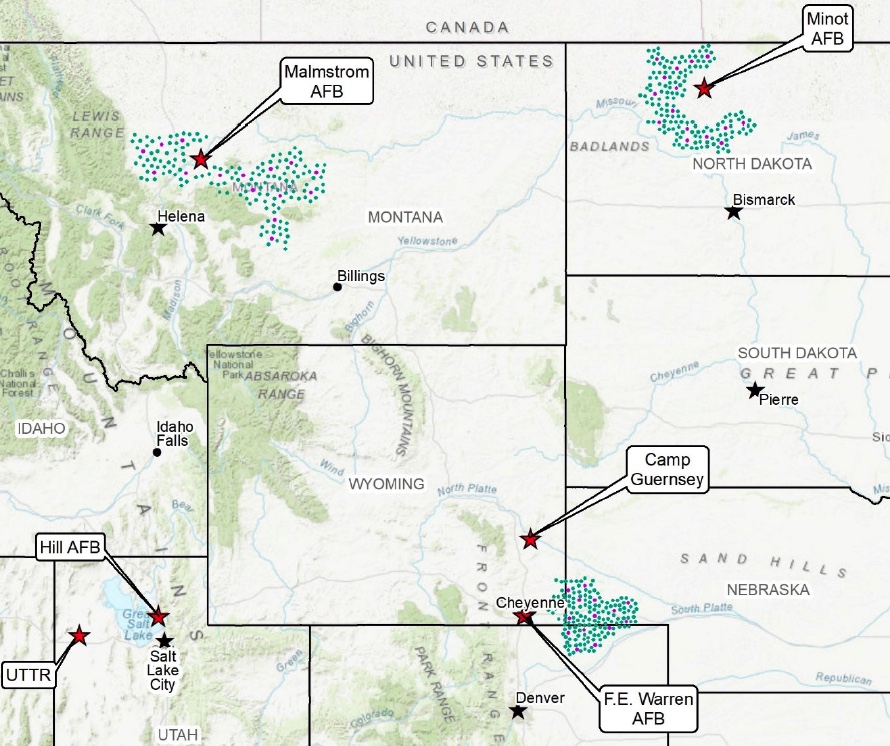

Map of the ICBM missile fields contained within the Air Force’s July 2022 assessment.

On July 1st, the Air Force published its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed ICBM replacement program, previously known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) and now by its new name, “Sentinel.” The government typically conducts an EIS whenever a federal program could potentially disrupt local water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other related factors.

A comprehensive environmental assessment is certainly warranted in this case, given the tremendous scale of the Sentinel program––which consists of a like-for-like replacement of all 400 Minuteman III missiles that are currently deployed across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, plus upgrades to the launch facilities, launch control centers, and other supporting infrastructure.

Cover page of the Air Force’s July 2022 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the GBSD.

The Draft EIS was anxiously awaited by local stakeholders, chambers of commerce, contractors, residents, and… me! Not because I’m losing sleep about whether Sentinel construction will disturb Wyoming’s Western Bumble Bee (although maybe I should be!), but rather because an EIS is also a wonderful repository for juicy, and often new, details about federal programs––and the Sentinel’s Draft EIS is certainly no exception.

Interestingly, the most exciting new details are not necessarily about what the Air Force is currently planning for the Sentinel, but rather about which ICBM replacement options they previously considered as alternatives to the current program of record. These alternatives were assessed during in the Air Force’s 2014 Analysis of Alternatives––a key document that weighs the risks and benefits of each proposed action––however, that document remains classified. Therefore, until they were recently referenced in the July 2022 Draft EIS, it was not clear to the public what the Air Force was actually assessing as alternatives to the current Sentinel program.

Missile alternatives

The Draft EIS notes that the Air Force assessed four potential missile alternatives to the current plan, which involves designing a completely new ICBM:

- Reproducing Minuteman III ICBMs to “existing specifications” by washing out and refilling the first- and second-stage rocket boosters; remanufacturing the third stages and Propulsion System Rocket Engine––the ICBM’s post-boost vehicle; and refurbishing and replacing all other subsystems;

The Air Force appears to have ultimately eliminated all four of these options from consideration because they did not meet all of their “selection standards,” which included criteria like sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure.

Of particular interest, however, is the Air Force’s note that the Minuteman III reproduction alternative was eliminated in part because it did not “meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs in the context of modern and evolving threats (e.g., range, payload, and effectiveness.” It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade.

This statement also suggests that “modern and evolving threats” are driving the need for an operationally improved ICBM; however, it is unclear what the Air Force is referring to, or how these threats would necessarily justify a brand-new ICBM with new capabilities. As I wrote in my March 2021 report, “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,”

“With respect to US-centric nuclear deterrence, what has changed since the end of the Cold War? China is slowly but steadily expanding its nuclear arsenal and suite of delivery systems, and North Korea’s nuclear weapons program continues to mature. However, the range and deployment locations of the US ICBM force would force the missiles to fly over Russian territory in the event that they were aimed at Chinese or North Korean targets, thus significantly increasing the risk of using ICBMs to target either country. Moreover, […] other elements of the US nuclear force––especially SSBNs––could be used to accomplish the ICBM force’s mission under a revised nuclear force posture, potentially even faster and in a more flexible manner. […] It is additionally important to note that even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload––not the missile itself. By the time that an adversary’s interceptor was able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would have already shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and would be guided solely by its reentry vehicle. Reentry vehicles and missile boosters can be independently upgraded as necessary, meaning that any concerns about adversarial missile defenses could be mitigated by deploying a more advanced payload on a life-extended Minuteman III ICBM.”

Of additional interest is the passage explaining why the Air Force dismissed the possibility of using the Trident II D5 SLBM as a land-based weapon:

“The D5 is a high-accuracy weapon system capable of engaging many targets simultaneously with overall functionality approaching that of land- based missiles. The D5 represents an existing technology, and substantial design and development cost savings would be realized; but the associated savings would not appreciably offset the infrastructure investment requirements (road and bridge enhancements) necessary to make it a land-based weapon system. In addition, motor performance and explosive safety concerns undermine the feasibility of using the D5 as a land-based weapon system.”

The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate. However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests: in 2015 the Navy conducted a successful Trident flight test using “the oldest 1st stage solid rocket motor flown to date” (over 26 years old), with 2nd and 3rd stage motors that were 22 years old. In January 2021, Vice Admiral Johnny Wolfe Jr.––the Navy’s Director for Strategic Systems Programs––remarked that “solid rocket motors, the age of those we can extend quite a while, we understand that very well.” This is largely due to the Navy’s incorporation of nondestructive testing techniques––which involve sending a probe into the bore to measure the elasticity of the propellant––to evaluate the reliability of their missiles.

As a result, the Navy is not currently contemplating the purchase of a brand-new missile to replace its current arsenal of Trident SLBMs, and instead plans to conduct a second life-extension to keep them in service until 2084. However, the Air Force’s comments suggest either a lack of confidence in this approach, or perhaps an institutional preference towards developing an entirely new missile system. [Note: Amy Woolf helpfully offered up another possible explanation, that the Air Force’s concerns could be related to the ability of the Trident SLBM’s cold launch system to perform effectively on land, given that these very different launch conditions could place additional stress on the missile system itself.]

Basing alternatives

The Draft EIS also notes that the Air Force assessed two fascinating––and somewhat familiar––alternatives for basing the new missiles: in underground tunnels and in “deep-lake silos.”

The tunnel option––which had been teased in previous programmatic documents but never explained in detail––would include “locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles”––and it is effectively a mashup of two concepts from the late Cold War.

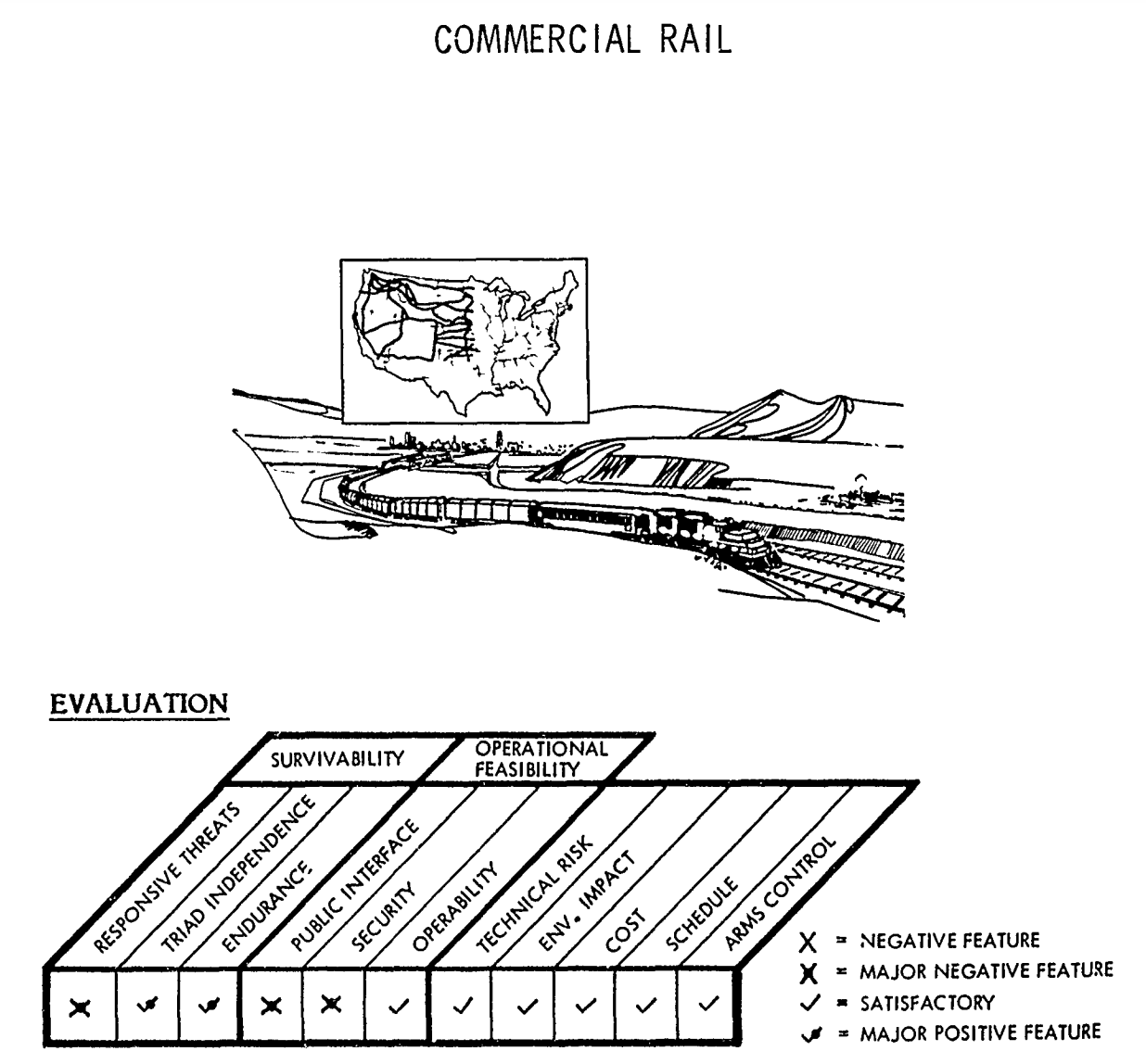

The rail concept was strongly considered during the development of the MX missile in the 1980s, although the plan called for missile trains to be dispersed onto the country’s existing civilian rail network, rather than into newly-built underground tunnels. Both the rail and tunnel concepts were referenced in one of my favourite Pentagon reports––a December 1980 Pentagon study called “ICBM Basing Options,” which considered 30 distinct and often bizarre ICBM basing options, including dirigibles, barges, seaplanes, and even hovercraft!

Illustrations of “Commercial Rail” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

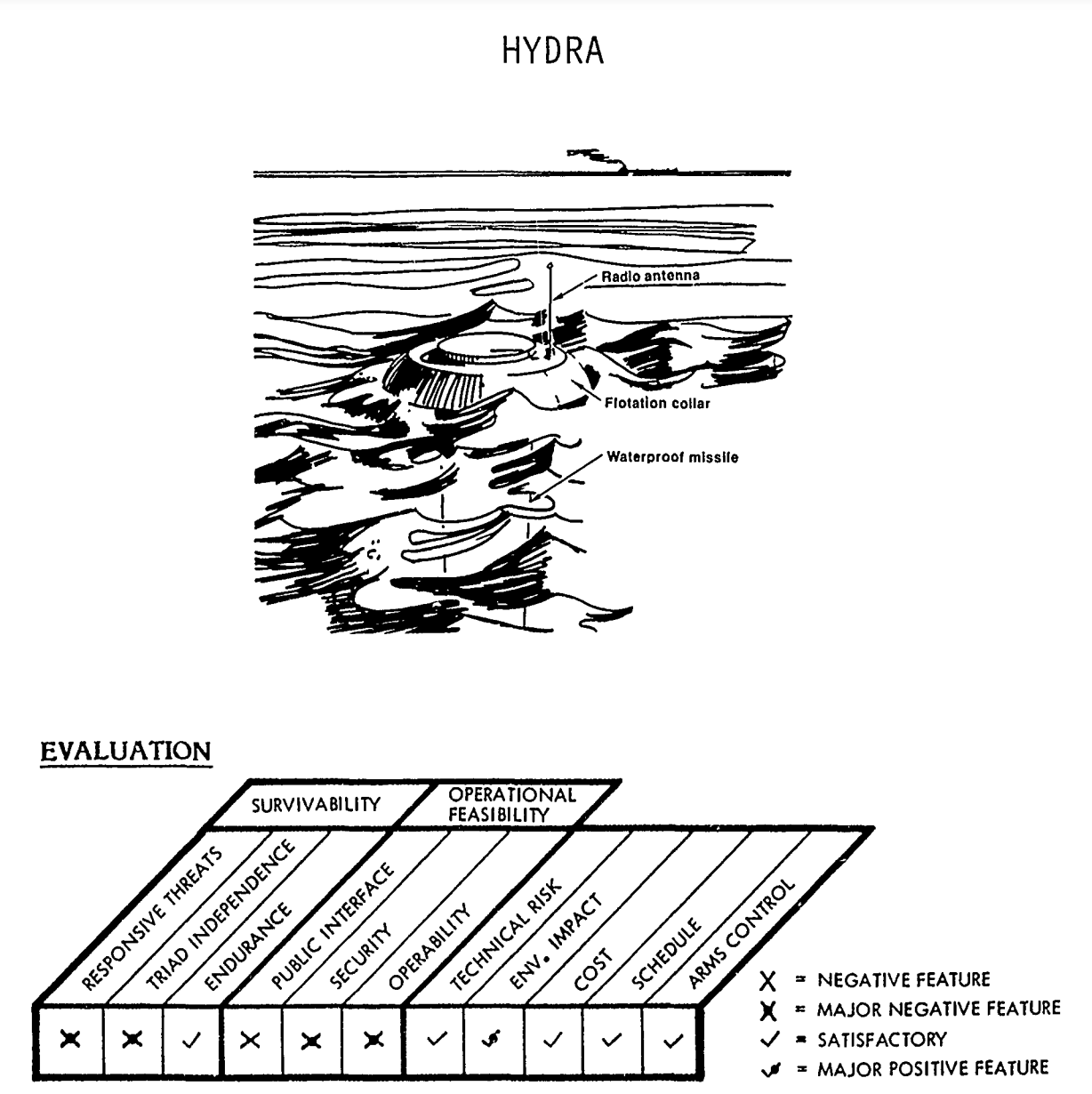

The second option––basing ICBMs in deep-lake silos––was also referenced in that same December 1980 study. The concept––nicknamed “Hydra”––proposed dispersing missiles across the ocean using floating silos, with “only an inconspicuous part of the missile front end [being] visible above the surface.” Interestingly, this raises the theoretical question of whether the Air Force would still maintain control over the ICBM mission, given that the missiles would be underwater.

Illustration of “Hydra” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

When considering alternative basing modes for the Sentinel ICBM, the Air Force eliminated both concepts due to cost prohibitions, and, in the case of underwater basing, a lack of confidence that the missiles would be safe and secure. This concern was also floated in the 1980 study as well, with the Pentagon acknowledging the likelihood that US adversaries and non-state actors “would also be engaged in a hunt for the Hydras. Not under our direct control, any missile can be destroyed or towed away (stolen) at leisure.”

Another potential option?

In addition to revealing these fascinating details about previously considered alternatives to the Sentinel program, the Draft EIS also highlighted a public comment suggesting that “the most environmentally responsible option” would simply be the reduction of the Minuteman III inventory.

The Air Force rejected the comment because it says that it is “required by law to accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground based strategic deterrent program;’” however, the public commenter’s suggestion is certainly a reasonable one. The current force level of 400 deployed ICBMs is not––and has never been––a magic number, and it could be reduced further for a variety of reasons, including those related to security, economics, or a good faith effort to reduce deployed US nuclear forces. In particular, as George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi wrote in a 2021 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, “This assumption that the ICBM force would not be eliminated or reduced before 2075 is difficult to reconcile with U.S. disarmament obligations under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.”

The security environment of the 21st century is already very different than that of the previous century. The greatest threats to Americans’ collective safety are non-militarized, global phenomena like climate change, domestic unrest and inequality, and public health crises. And recent polling efforts by ReThink Media, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Federation of American Scientists suggest that Americans overwhelmingly want the government to invest in more proximate social issues, rather than on nuclear weapons. To that end, rather than considering building new missile tunnels, it would likely be much more domestically popular to spend money on domestic priorities––perhaps new subway tunnels?

—

Background Information:

- “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,” Federation of American Scientists (Mar. 2021)

- “Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan,” Federation of American Scientists (Nov. 2020)

- ICBM Information Project, Federation of American Scientists

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and Longview Philanthropy. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DoD Again Presses for New FOIA Exemption

The Department of Defense is once again asking Congress for an exemption from the Freedom of Information Act for certain unclassified military information including records on critical infrastructure and military tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs).

The latest proposal was included in the Pentagon’s draft of legislative language for the Fiscal Year 2022 defense authorization act (section 1002, Nondisclosure of certain sensitive military information).

Similar language has been proposed by DoD each year since 2015, and each year (so far) it has been rejected by Congress. (“DoD Seeks New FOIA Exemption for Fourth Time,” Secrecy News, May 1, 2018).

The provision is still needed, according to DoD. “The effectiveness of U.S. military operations is dependent upon adversaries, or potential adversaries, not obtaining advance knowledge of sensitive TTPs, rules for the use of force; or rules of engagement that will be employed in such tactical operations,” DoD wrote in its June 7 justification of the proposal.

Furthermore, DoD assured Congress that if it were approved the exemption would not be used indiscriminately. It “will not be applied in an overly broad manner to withhold from public disclosure information related to the handling of disciplinary matters, investigations, acquisitions, intelligence oversight, oversight of contractors, allegations of sexual harassment or sexual assault, allegations of prisoner and detainee maltreatment, installation management activities, etc.”

Most DoD doctrinal publications are unclassified and are publicly available online. Some are classified. But some are unclassified and restricted. For example, last week the Army issued a publication on Special Forces Air Operations (ATP 3-18.10) that is unclassified but that is only available to government agencies and contractors. The withholding of such documents might be susceptible to a focused challenge under the Freedom of Information Act, and DoD apparently wishes to bolster its legal defense against any such challenge.

The Freedom of Information Act provides both for disclosure and for withholding of various government records, so exemptions are part of the package.

But Congress may again decide to reject DoD’s latest proposal because of the Department’s inconsistent and unreliable implementation of the FOIA.

There are FOIA requests dating back as far as 2005 that are still pending at the Defense Intelligence Agency, according to the latest DoD annual report on FOIA. If an agency is unable to act on a valid FOIA request for a decade or longer, a new exemption would be superfluous.

DoD has also taken a relaxed approach to other statutory requirements.

In December 2019, Congress enacted a provision requiring DoD to produce a plan for addressing the backlog of classified documents awaiting declassification. (“Pentagon Must Produce Plan for Declassification,” Secrecy News, December 11, 2019). This was not optional. But it was not done.

More Light on Black Program to Track UFOs

The Defense Intelligence Agency disclosed this week that it had funded research on warp drive, invisibility cloaking, and other areas of fringe or speculative science and engineering as part of a now-defunct program to track and identify threats from space.

From 2007 to 2012, the DIA spent $22 million on the activity, formally known as the Advanced Aerospace Threat Identification Program. It was apparently initiated at the behest of then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, with most of the funding directed to a Nevada constituent of his. See “Glowing Auras and ‘Black Money’: The Pentagon’s Mysterious U.F.O. Program” by Helene Cooper, Ralph Blumenthal and Leslie Kean, New York Times, December 16, 2017.

Yesterday, the DIA released a list of 38 research titles funded by the program, many of which are highly conjectural and well beyond the boundaries of current science, engineering — or military intelligence. One such title, “Traversable Wormholes, Stargates, and Negative Energy,” was prepared by Dr. Eric Davis, who has also written on “psychic teleportation.”

(Dr. Davis responded vigorously to skepticism of his work in a 2006 comment to this Secrecy News post.)

The DIA list of research papers, marked for Official Use Only, was previously provided to Congress in January 2018. It was publicly released yesterday under the Freedom of Information Act.

Although many FOIA offices are closed due to the continuing shutdown of the federal government, the DIA FOIA office and at least some others in the Department of Defense are still operational.

A DIA FOIA officer noted with some exasperation that yesterday’s release of the list of research papers will, in all likelihood, prompt new FOIA requests to his Agency for each of the listed papers.

DOE Declassifies Declassification of Downblending Move

Last year, the Department of Energy decided to declassify the fact it intended to make 25 metric tons of Highly Enriched Uranium available from “the national security inventory” for downblending into Low Enriched Uranium for use in the production of tritium.

However, the decision to declassify that information was classified Secret.

This year, the Department of Energy decided to declassify the declassification decision, and it was disclosed last week under the Freedom of Information Act.

While the contortions in classification policy are hard to understand, the underlying move to downblend more HEU for tritium production probably makes sense. Among other things, it “delays the urgency — but doesn’t eliminate the eventual need — to build a new domestic enrichment capacity,” said Alan J. Kuperman of the University of Texas at Austin.

There were 160 MT of US HEU downblended by the end of FY 2018, according to the FY 2019 DOE budget request (volume 1, at page 474), and a total of 162 MT was anticipated by the end of FY 2019, as noted recently by the International Panel on Fissile Materials.

“The overall amount of HEU available for down-blending and the rate at which it will be down-blended is dependent upon decisions regarding the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, the pace of warhead dismantlement and receipt of HEU from research reactors, as well as other considerations, such as decisions on processing of additional HEU through H-Canyon, disposition paths for weapons containing HEU, etc,” according to the DOE budget request.

Aircraft Interdiction Nets Colombian Cocaine

With the support of U.S. intelligence, the Colombian Air Force last year engaged dozens of aircraft suspected of illicit drug trafficking, leading to the seizure of 4.4 metric tons of cocaine.

In 2017, “Colombia, with the assistance of the United States, responded to 80 unknown assumed suspect (UAS) air tracks throughout Colombia and the central/western Caribbean,” according to the latest annual report on the program. The report does not say how many of the aircraft were actually interdicted or fired upon. There were also 139 aircraft that were grounded by Colombian law enforcement agencies.

See Annual Report of Interdiction of Aircraft Engaged in Illicit Drug Trafficking (2017), State Department report to Congress, January 2018 (released under FOIA, October 2018).

The joint US-Colombia effort dates back at least to a 2003 Air Bridge Denial program involving detection, monitoring, interception, and interdiction of suspect aircraft.

The basic procedures for intercepting, warning, and attacking a suspect aircraft were more fully described in a 2010 version of the annual report. At that time, Brazil was also part of the Air Bridge Denial program.

US support for the Colombia aircraft interdiction program — which includes providing intelligence and radar information, as well as personnel training — was renewed by the President in a July 20, 2018 determination.

To Fix FOIA, “Best Practices” Will Not Be Enough

Many executive branch agencies have significant backlogs of Freedom of Information Act requests that could be reduced by adopting procedural improvements. And some agencies have made such improvements, a new report from the Government Accountability Office says. Yet substantial backlogs remain.

See Freedom of Information Act: Agencies Are Implementing Requirements but Additional Actions Are Needed, GAO-18-365, June 25.

All of the agencies reviewed had “implemented request tracking systems, and provided training to FOIA personnel.” Most of the agencies had also “provided online access to government information, such as frequently requested records…, designated chief FOIA officers, and… updated their FOIA regulations on time to inform the public of their operations.”

Nevertheless, FOIA is still not functioning well system-wide.

What the GAO report should have said but did not explicitly say is that even if all agencies adopted all of the recommended “best practices” for FOIA processing, they would still face substantial backlogs of unanswered requests.

The simple reason for that is that there is a mismatch between the growing demand from individual FOIA requesters — with 6 million requests filed in the past 9 years — and the resources that are available to satisfy them.

In order to bring the system into some rough alignment, it would be necessary either to increase the amount of agency funding appropriated and allocated for FOIA, or else to regulate the demand from requesters by imposing or increasing fees, limiting the number of requests from individual users, or some other restrictive measure.

None of these steps is appealing and none may be politically feasible. Other than a cursory reference to “available resources,” the GAO report does not address these core issues.

But in the absence of some such move to reconcile the “supply and demand” for FOIA, overall system performance is being degraded and seems unlikely to recover any time soon.

Meanwhile, government agencies have identified no fewer than 237 statutes that they say can be used to withhold information under the Freedom of Information Act, according to the GAO report, which tabulated the statutes. Since 2010, agencies have actually used 75 of those statutes. GAO did not venture an opinion as to whether the exemption statutes were properly and justifiably employed.

Another new report from Open the Government finds that “FOIA lawsuits grew steadily across the government by 57 percent overall for a ten year period, from 2006-15, and increased sharply by 26 percent in FY 2017.”

Court Rules in Favor of Selective Disclosure

The Central Intelligence Agency can selectively disclose classified information to reporters while withholding that very same information from a requester under the Freedom of Information Act, a federal court ruled last month.

The ruling came in a FOIA lawsuit brought by reporter Adam Johnson who sought a copy of emails sent to reporters Siobhan Gorman of the Wall Street Journal, David Ignatius of the Washington Post, and Scott Shane of the New York Times that the CIA said were classified and exempt from disclosure.

“The Director of Central Intelligence is free to disclose classified information about CIA sources and methods selectively, if he concludes that it is necessary to do so in order to protect those intelligence sources and methods, and no court can second guess his decision,” wrote Chief Judge Colleen J. McMahon of the Southern District of New York in a decision in favor of the CIA that was released last week with minor redactions.

The Freedom of Information Act is a tool that can change as it is used, whether for the better or the worse, especially since FOIA case law rests on precedent. That means that a FOIA lawsuit that is ill-advised or poorly argued or that simply fails for any reason can alter the legal landscape to the disadvantage of future requesters. In particular, as anticipated a few months ago, “a lawsuit that was intended to challenge the practice of selective disclosure could, if unsuccessful, end up ratifying and reinforcing it.” That is what has now happened.

The shift is starkly illustrated by comparing the statements of Judge McMahon early in the case, when she seemed to identify with the plaintiff’s perspective, and her own final ruling that coincided instead with the CIA’s position.

“There is absolutely no statutory provision that authorizes limited disclosure of otherwise classified information to anyone, including ‘trusted reporters,’ for any purpose, including the protection of CIA sources and methods that might otherwise be outed,” she had previously stated in a January 30 order.

“In the real world, disclosure to some who are unauthorized operates as a waiver of the right to keep information private as to anyone else,” which was exactly the plaintiff’s point.

“I suppose it is possible,” she added in a cautionary footnote, “that the Government does not consider members of the press to be part of ‘the public.’ I do.”

But this congenial (to the plaintiff) point of view would soon be abandoned by the court. By the end of the case, the mere act of disclosure to one or more members of the press would no longer be deemed equivalent to “public disclosure” for purposes of waiving an exemption from disclosure under FOIA.

Instead, Judge McMahon would come to accept, as the CIA argued in a February 14 brief, that “a limited disclosure of information to three journalists does not constitute a disclosure to the public. Where, as here, the record shows that the classified and statutorily protected information at issue has not entered the public domain, there is no waiver of FOIA’s exemptions.”

Plaintiff Johnson objected that “the Government cannot define ‘public’ to mean members of the public it is not disclosing information to.”

“The Government’s position that it may selectively disclose without waiver, if it has the best of intentions, knows no logical limits and would render the FOIA waiver doctrine a nullity,” he wrote. “The CIA’s motive in releasing the information is irrelevant under FOIA. Whether good reason, bad reason, or no reason at all, what matters is that an authorized disclosure took place. If the CIA does not wish to waive its secrecy prerogative, it cannot authorize a disclosure to a member of the public.”

In an amicus brief, several FOIA advocacy groups presented a subtle technical argument in support of the plaintiff. Under the circumstances, they concluded, the court had no choice but to order disclosure. “It does not matter… how much alleged damage the release of the information could cause.”

But these counterarguments proved unpersuasive to the court, and Judge McMahon ended up with a new conception of what constitutes the kind of prior “public disclosure” that would compel release of information under FOIA. Selective disclosure to individual reporters would not qualify.

“For something to be ‘public,’ it has to, in some sense, be accessible to members of the general public,” she now held in her final opinion.

“Selective disclosure of protectable information to an organ of the press… does not create a ‘truly public’ record of that information.” So CIA cannot be forced to disclose it to others. This was exactly the opposite of the view expressed by Judge McMahon earlier in the case.

The ruling was a defeat for the FOIA in the sense that it affirmed and strengthened a barrier to disclosure.

But it might also be considered a victory for the press, to the extent that it enables exchange of classified information with reporters off the record. Had the court compelled disclosure of the classified CIA emails to reporters Gorman, Ignatius and Shane, that would likely have reduced or eliminated the willingness of agencies to share classified information with reporters, as they occasionally do.

But the practice of selective disclosure has risks of its own, wrote plaintiff’s attorney Dan Novack last year. It “allow[s] the government to hypocritically release sensitive national security information when it suits its public relations interests without fear of being held to its own standard later.”

A Forum for Classified Research on Cybersecurity

By definition, scientists who perform classified research cannot take full advantage of the standard practice of peer review and publication to assure the quality of their work and to disseminate their findings. Instead, military and intelligence agencies tend to provide limited disclosure of classified research to a select, security-cleared audience.

In 2013, the US intelligence community created a new classified journal on cybersecurity called the Journal of Sensitive Cyber Research and Engineering (JSCoRE).

The National Security Agency has just released a redacted version of the tables of contents of the first three volumes of JSCoRE in response to a request under the Freedom of Information Act.

JSCoRE “provides a forum to balance exchange of scientific information while protecting sensitive information detail,” according to the ODNI budget justification book for FY2014 (at p. 233). “Until now, authors conducting non-public cybersecurity research had no widely-recognized high-quality secure venue in which to publish their results. JSCoRE is the first of its kind peer-reviewed journal advancing such engineering results and case studies.”

The titles listed in the newly disclosed JSCoRE tables of contents are not very informative — e.g. “Flexible Adaptive Policy Enforcement for Cross Domain Solutions” — and many of them have been redacted.

However, one title that NSA withheld from release under FOIA was publicly cited in a Government Accountability Office report last year: “The Darkness of Things: Anticipating Obstacles to Intelligence Community Realization of the Internet of Things Opportunity,” JSCoRE, vol. 3, no. 1 (2015)(TS//SI//NF).

“JSCoRE may reside where few can lay eyes on it, but it has plenty of company,” wrote David Malakoff in Science Magazine in 2013. “Worldwide, intelligence services and military forces have long published secret journals” — such as DARPA’s old Journal of Defense Research — “that often touch on technical topics. The demand for restricted outlets is bound to grow as governments classify more information.”

US Gifts to Foreign Individuals Reported

The Obama Administration gave dozens of wrist watches to various foreign leaders in 2014.

A newly released State Department report to Congress lists all of the gifts presented by President Obama, Mrs. Obama, Vice President Biden, Mrs. Biden, and Secretary of State Kerry to foreign individuals.

The 32 page report reflects the fact that the presentation of gifts is a customary feature of personal encounters between US and foreign leaders, as is the recording and reporting of each gift.

Based on the descriptions in the report, most of the gifts seem generic and unimaginative, not reflecting any particularized esteem. The most common gift was a “custom men’s watch in a wooden presentation box with inscription plaque” with a reported value of $465.

One exception was a “custom seed chest… containing nine varieties of American seeds” (declared value $1964.87) that was presented to Pope Francis. Also noteworthy is a rare edition of a book about the 1893 World’s Congress of Religions that featured Swami Vivekananda and other luminaries (declared value $1375 — but now half that price on Amazon) that was given to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

The report on gifts from the United States to foreign individuals in FY2014 was released under the Freedom of Information Act following a three-year processing delay.

DOE Seeks to End MOX Plutonium Disposal Program

The Trump Administration requested $220 million next year “to continue the orderly and safe closure of the Mixed Oxide (MOX) Fuel Fabrication Facility.”

The MOX Fuel Fabrication Facility was intended to eliminate excess weapons-grade plutonium by blending it with uranium oxide to produce a “mixed oxide” that is not suitable for nuclear weapons. The Administration proposes instead to pursue a “dilute and dispose” approach.

Termination of the MOX Facility in South Carolina had previously been proposed — but not approved — in budget requests for the last two years, due to mounting costs.

“Construction remains significantly over budget and behind schedule,” the Department of Energy said in a November 2017 report to Congress. “The MOX production objective was not met in 2015 or 2016 and will not be met in 2017.”

“Due to the increasing costs of constructing and operating the MOX facility, both the Department’s analysis and independent analyses of U.S. plutonium disposition strategies have consistently and repeatedly concluded that the MOX fuel strategy is more costly and requires more annual funding than the dilute and dispose approach,” the DOE report said. The report was released by DOE under the Freedom of Information Act.

Though disfavored by the Administration, the MOX program has a champion in South Carolina Senator Lindsay Graham. “I will fight like crazy” to preserve it unless he is convinced that a superior alternative exists, he said at a February 8 hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Detailed background on the MOX program can be found in Mixed-Oxide Fuel Fabrication Plant and Plutonium Disposition: Management and Policy Issues, Congressional Research Service, December 14, 2017.

The latest proposal to terminate the MOX program was reported in “Aiken County legislators unsurprised by Trump’s anti-MOX budget” by Colin Demarest, Aiken Standard, February 19.

CIA Defends Selective Disclosure to Reporters

The Central Intelligence Agency said yesterday that it has the right to disclose classified information to selected journalists and then to withhold the same information from others under the Freedom of Information Act.

FOIA requester Adam Johnson had obtained CIA emails sent to various members of the press including some that were redacted as classified. How, he wondered, could the CIA give information to uncleared reporters — in this case Siobhan Gorman (then) of the Wall Street Journal, David Ignatius of the Washington Post, and Scott Shane of the New York Times — and yet refuse to give it to him? In an effort to discover the secret messages, he filed a FOIA lawsuit.

His question is a good one, said Chief Judge Colleen McMahon of the Southern District of New York in a court order last month. “The issue is whether the CIA waived its right to rely on otherwise applicable exemptions to FOIA disclosure by admittedly disclosing information selectively to one particular reporter [or three].”

“In this case, CIA voluntarily disclosed to outsiders information that it had a perfect right to keep private,” she wrote. “There is absolutely no statutory provision that authorizes limited disclosure of otherwise classified information to anyone, including ‘trusted reporters,’ for any purpose, including the protection of CIA sources and methods that might otherwise be outed. The fact that the reporters might not have printed what was disclosed to them has no logical or legal impact on the waiver analysis, because the only fact relevant to waiver analysis is: Did the CIA do something that worked a waiver of a right it otherwise had?”

Judge McMahon therefore ordered CIA to prepare a more rigorous justification of its legal position. It was filed by the government yesterday.

CIA argued that the court is wrong to think that limited, selective disclosures of classified information are prohibited or unauthorized by law. The National Security Act only requires protection of intelligence sources and methods from “unauthorized” disclosure, not from authorized disclosure. And because the disclosures at issue were actually intended to protect intelligence sources and methods, they were fully authorized, CIA said. “The CIA properly exercised its broad discretion to provide certain limited information to the three reporters.”

“The Court’s supposition that a limited disclosure of information to three journalists necessarily equates to a disclosure to the public at large is legally and factually mistaken,” the CIA response stated. “The record demonstrates beyond dispute that the classified and statutorily protected information withheld from the emails has not entered the public domain. For these reasons, the limited disclosures here did not effect any waiver of FOIA’s exemptions.”

A reply from plaintiff Adam Johnson is due March 1. (Prior coverage: Tech Dirt, Intel Today).

Selective disclosure of classified information to uncleared reporters is a more or less established practice that is recognized by Congress, which has required periodic reporting to Congress of such disclosures. See Disclosing Classified Info to the Press — With Permission, Secrecy News, January 4, 2017.

The nature of FOIA litigation is such that a lawsuit that was intended to challenge the practice of selective disclosure could, if unsuccessful, end up ratifying and reinforcing it.