How Should FESI Work with DOE? Lessons Learned From Other Agency-Affiliated Foundations

In May, Secretary Granholm took the first official step towards standing up the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) by naming its inaugural board. FESI, authorized in the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 and appropriated in the FY24 budget, holds a unique place in the clean energy ecosystem. It can convene public-private partnerships and accept non-governmental and philanthropic funding to spur important projects. FESI holds tremendous potential for empowering the DOE mission and accelerating the energy transition.

Through the Friends of FESI Initiative at FAS, we’ve identified a few opportunities for FESI to have some big wins early on – including boosting next-generation geothermal development and supporting pilot stage demonstrations for nascent clean energy technologies. We’ve also written about how important it is for the FESI Board to be ambitious and to think big. It’s important that FESI be intentional and thoughtful about the way that it’s structured and connected to the Department of Energy (DOE). The advantage of an entity like FESI is that it’s independent, non-governmental, and flexible. Therefore, its relationship to DOE must be complementary to DOE’s mission, but not tethered too tightly. FESI should not be bound by the same rules as DOE.

While the board has been organizing itself and selecting a leadership team, we’ve been gathering insights from leaders at other Congressionally-chartered foundations to provide best practices and lessons learned for a young FESI. Below, we make a case for the mutually-beneficial agreement that DOE and FESI should pursue, outline the arrangements that three of FESI’s fellow foundations have with their anchor agencies, and highlight which elements FESI would be wise to incorporate based on existing foundation models. Structuring an effective relationship between FESI and DOE from the start is crucial for ensuring that FESI delivers impact for years to come.

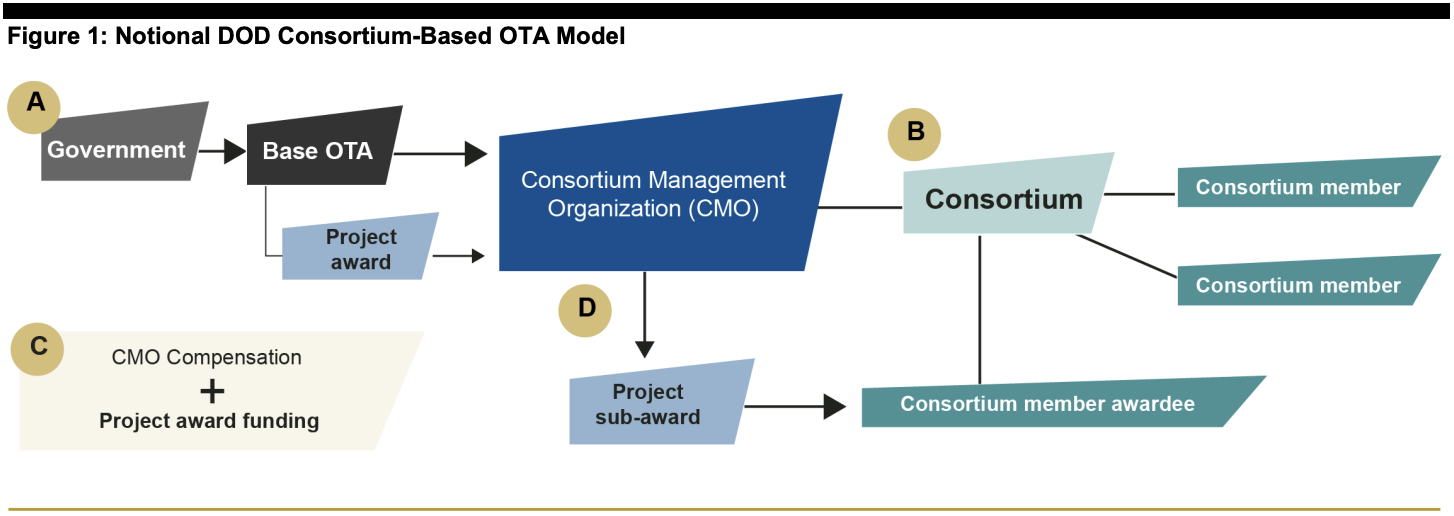

Other Transactions Agreements (OTA)

If FESI is going to continue to receive Congressional appropriations through DOE, which we hope it will, it should be structured from the start in a way that allows it to be as effective as possible while it receives both taxpayer dollars and private support. The legal arrangement between FESI and DOE that most lends itself to supporting these conditions is an Other Transactions (OT) agreement. Congress has granted several agencies, including DOE, the authority to use OTs for research, prototype, and production purposes, and these agreements aren’t bound by the same regulations that government contracts or grants are. FESI and DOE wouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel to design a mutually beneficial OT agreement after looking at other shining examples from other agencies.

Effective Use of an Other Transactions Agreement Between FNIH and NIH

Many consider the gold standard of public-private accomplishment – made possible through an Other Transactions Agreement – to be a partnership first ideated in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Leaders at the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Foundation for National Institute of Health (FNIH) were faced with an unprecedented need for developing a vaccine on an accelerated timeline. In a matter of weeks, these leaders pulled together a government-industry-academia coalition to coordinate research and clinical testing efforts. The resulting partnership is called ACTIV (Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines) and includes eight U.S. government agencies, 20 biopharmaceutical companies and several nonprofit organizations.

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change is a global crisis. Expedited energy research, commercialization, and deployment efforts require cohesive collaboration between government and the private sector. Other Transactions consortia like ACTIV pool together the funding to support some of the brightest minds in the field, in alignment with the national agenda, and return discoveries to the public domain. Pursuing an OT agreement allowed the FNIH and NIH to act swiftly and at the scale required to begin to tackle the task of developing a life-saving vaccine.

What We Can Learn from Other Agency-Affiliated Foundations

FESI Needs to Find its Specific Value-Add and then Execute

The allure of an independent, non-governmental foundation like FESI is pretty straightforward. Unencumbered by traditional government processes, agency-affiliated foundations are nimble, fast-moving, and don’t face the same operational barriers as government when working with the private sector. They can raise and pool funds from private and philanthropic donors. For that reason, it’s crucial that FESI differentiates itself from DOE and doesn’t become a shadow agency. Although FESI’s mission aligns with that of the DOE’s, and may focus on programs similar to those of ARPA-E, there is a drastic difference between being a federal agency and being a foundation affiliated with a federal agency.

FESI’s potential relies on its ability to be independent enough to take risks while still maintaining a strong relationship with DOE and the agency’s mission. FESI’s goals should be aligned with DOE’s through frequent communication with the agency – to understand priorities, opportunities, and barriers it might face in achieving those goals. In reality, neither FESI nor DOE can directly instruct the other what to do, but the two entities should be aligned and aware of what the other is doing at all times.

Additionally, a young FESI should figure out what it can do that DOE can’t and then capitalize on that. The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR), for example, was established with a specific purpose of convening public private partnerships. At the time, the USDA struggled to connect with industry. FFAR found its benefit by serving as a more flexible extension of the agency’s aims. FESI could play a similar role – acting in concert with DOE, but playing different instruments.

More important than the agreement are the relationships between FESI and DOE leaders and staff

Pursue a flexible agreement that can be revisited and revised

Whatever relationship structure DOE and FESI decide on needs to be flexible enough so that they can both exercise the relationship required to tackle problems together. The agreement needs to be more than a list of what FESI can and can’t do. Based on other foundations’ experiences, it is best to revisit, revise, and refresh the document every so often. An ancient contract collects dust and doesn’t serve FESI or DOE. Luckily, Other Transactions agreements can be amended at any time.

Select a strategic executive director with a vision

DOE is racing against time to commercialize the clean energy technology needed to solve difficult decarbonization challenges. With FESI’s strength being its agility and ability to act quickly, the foundation is poised to be an invaluable asset to DOE’s mission. Whomever the FESI Board designates to lead this fight must walk in on day one with a clear, focused vision ready to fund projects that earn wins and to work with the board to make good on their promises. One of the first challenges they will face will be educating the ecosystem about FESI’s role and purpose. A clearly articulated answer to, “What does FESI hope to accomplish?” is key for fundraising and program design and execution.

Being FESI’s first ever executive director is no small feat and the board’s selection should be a quick study who has proven experience under their belt for fundraising and managing nine-figure budgets – the scale that we hope FESI is one day able to operate at. A successful leader will have high credibility throughout the energy system and with both political parties. They will bring with them networks that span sectors and add on to those of the board members. With these assets in tow, the Secretary of Energy should be excited about the FESI executive director and eager to work with them.

The agreement is the backstop, but the game is played at the plate

An overarching theme across each agency-affiliated foundation is the importance of agency-foundation relationships that are based on deep trust. One foundation leader even said, “It’s really not about the paper – [the structuring agreement] – at all.” Instead, they said, the success of an agency and its foundation runs on “tacit knowledge and relationships” that will grow over time between foundation and agency. Clearly, an agreement needs to be in place between FESI and DOE, but if the organization “runs exclusively off those pieces of paper, it won’t be its best self.”

As a young FESI grows over time, leaders of each organization – the FESI executive director and the Secretary of Energy – and the board and the executive director should all be in close contact with one another. Any of these folks should be able to pick up the phone, dial their counterpart, and give them good – or bad – news directly. These relationships should be prioritized and fostered, especially early on.

Create and raise the profile of FESI as early as possible

By far the greatest benefit of DOE having an agency-affiliated foundation is that FESI can raise and distribute funding more quickly and more efficiently than DOE will ever be able to. This can be a great driver for DOE success as FESI’s role is to support the agency. The FNIH, for example, can raise funding from biopharma, send it into projects, and then grant it out, all while avoiding cumbersome procedures since that money doesn’t belong to taxpayers.

To successfully fundraise, FESI will need the staff and the infrastructure needed to identify and execute on promising projects. Leaders at other foundations have found that their respective funder ecosystems are drawn to projects that fill a gap and that convene the public and private sectors. Whenever possible, and to the extent possible, FESI should aim to pool funding from different streams by convening consortia – in order to avoid the procedural strings attached to receiving federal dollars. One example, the Biomarkers Consortium, led by the FNIH, pools funding from government, for-profit, and non-profit partners. Members of this consortium pay annual dues to participate and contribute their scientific and technical expertise as advisors.

How Do Other Congressionally-chartered Foundations Work with Their Agencies?

The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture

In the first year of the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR), it had $200 million from Congress, one staff member, and no reputation to fundraise off of. By year three, FFAR had established its first public-private consortium – composed of companies and global research organizations working to develop crop varieties to meet global nutritional demands in a changing environment. FFAR provided the Crops of the Future Collaborative with an initial $10 million investment that was matched by participants for a total investment of $20 million. The law requires that the foundation matches every dollar of public funding with at least one dollar from a private source. This partnership marked FFAR’s first big, early win that set the young foundation on a road to success.

FFAR is unique among its fellow foundations as it doesn’t receive any funding from USDA. Instead, FFAR receives appropriations from the Farm Bill about every five years as mandatory funding that doesn’t go through the regular appropriations process. Because of this, this funding is separate from that of the USDA’s so the funding streams remain separate and not in competition with one another. While FFAR doesn’t receive money from USDA, USDA can receive grants from FFAR and the two entities conduct business in close coordination with one another. Whenever FFAR identifies a program for launch, its staff run the possibility past the USDA to ensure that FFAR is filling a USDA gap and that there isn’t any programmatic overlap.

A memorandum of understanding (MOU) is the legal agreement of choice that structures the relationship between USDA and FFAR. This document describes how the two exchange with each other and is updated every other year. In addition, FFAR has USDA representatives sit as ex-officio members of its board. While FFAR remains to this day quite independent of the USDA, according to staff, the agency is a “valued piece” of the work of the foundation.

In addition to having an MOU with USDA, FFAR has MOUs and funding agreements with each of the corporations in their consortia. These funding agreements either give FFAR money or fund the project directly. The foundation’s public private partnerships are generally funded through a competitive grants process or through direct contract; however, the foundation also uses prize competitions to encourage the development of new technologies.

When it comes to fundraising as a science-based organization, FFAR has encountered distinct challenges. Most of its fundraising is done by its Executive Director and scientists who solicit funding for each of its six main research focus areas. Initially, in 2016, these six “Challenge Areas” were selected by the board of directors using stakeholder input to address urgent food and agricultural needs. Recently, FFAR has pivoted to a framework that is based on four overarching priority areas – Agroecosystems, Production Systems, Healthy Food Systems and Scientific Workforce Development. Defining focus areas creates clarity and structure for a foundation working in an overwhelming abyss of opportunity. It would be wise for FESI leadership to define a handful of focus areas to hone in on in its early rounds of projects.

Most of FFAR’s fundraising efforts are on a project and program basis, instead of finding high net-worth individuals that will donate large sums of untethered money. To be a successful fundraiser, FFAR leaders must be able to clearly articulate the vision of the foundation, locate projects that will appeal to donors, and also be able to articulate the benefits to donors (i.e. receiving early access to information or notice of publications). FFAR leaders have found that projects that promise to fill gaps between the public and private sector have proven highly enticing amongst the funder community.

The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and The National Institutes of Health

The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) is going on its 35th year advancing the mission of the NIH and leading public-private partnerships that advance breakthrough biomedical discoveries. Its authorizing statute has been amended slightly since it was initially passed in 1990, but its language served as a model for FESI’s authorization legislation.

The FNIH statute does not lay down specific rules or regulations for projects or programs that the organization is confined to. Instead, it allows the foundation to do whatever its leaders decide, as long as it relates to NIH and there’s a partner from the NIH involved. Per law, the NIH Director is required to transfer “not less than $1.25 million and not more than $5 million” of the agency’s annual appropriations to FNIH. Between FY2015 and FY2022, NIH transferred between $1 million and $1.25 million annually to FNIH for administrative and operational expenses (less than 0.01% of NIH’s annual budget).The FNIH and the NIH also have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed to facilitate the legal relationship between each organization, though this agreement has aged since it was signed and the relationship in practice is more informal.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Fish and Wildlife Service

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), chartered by Congress to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), is the nation’s largest non-governmental conservation grant-maker. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the NFWF awarded $1.3 billion to 797 projects that will generate a total conservation impact of $1.7 billion.

NFWF doesn’t have a guiding agreement, like an MOU, with FWS. Instead, it uses the text language in the initial authorizing legislation. Since its inception, NFWF has built cooperative agreements with roughly 15 other agencies and 150 active federal funding sources. These agreements function as mechanisms through which agencies can transfer appropriated funds over to NFWF to administer and deploy to projects on the ground. These cooperative agreements are revisited on a program-specific basis; some are revised annually, while others last over a five-year period.

Congress mandates that each federal dollar NFWF awards is matched with a non-federal dollar or “equivalent goods and services.” NFWF also has its own policy that it aims to achieve at least a 2:1 return on its project portfolio — $2 raised in matching contributions to every federal dollar awarded. This non-federal funding comes from conservation-focused philanthropic foundations, but also project developers needing to fulfill regulatory obligations, or even from legal settlements, such as in the case of NFWF receiving $2.544 billion from BP and Transocean to fund Gulf Coast projects impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

To distribute this money, NFWF solicits its own requests for proposals (RFP), separate from FWS, and awards roughly 98% of its grants to NGOs or state/local governments. If it wanted, FWS could apply to or be a joint applicant to receive a grant issued by NFWF. Earlier this year, NFWF announced an RFP – the “America the Beautiful Challenge” – that pooled funds $119 million from multiple federal agencies and the private sector to eventually award to project applicants working to address conservation and public access needs across public, Tribal, and private lands. NFWF has review committees composed of NFWF staff and third-party expert consultants or members of other involved agencies. These committees converge to discuss a proposed slate of projects to decide which move forward before the NFWF Board delivers its seal of approval.

While NFWF is regarded as a successful model of a foundation supporting several federal agencies, its accomplishments are slightly distinct from what FESI has been created to do. As a 501(c)3, NFWF is able to channel funds from various sources, both public and private, to support projects that comply with federal conservation and resilience requirements. NFWF works closely with the Department of Defense to fund resilience projects that protect military bases and nearby towns against natural disasters in coastal areas. With just under 200 employees, NFWF is also able to serve as a “release valve” for agencies that do not have the workforce capacity to handle the influx of work generated by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) or Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), for example. While FESI could take on projects that DOE doesn’t have the capacity or agility to handle, it should also operate independently and aim to act on ideas that originate from outside of DOE.

Takeaways for FESI

The foundations that have preceded FESI, each chartered by Congress to support the mission of federal agencies, have proven that these models can be successful. They have supported public-private partnerships to produce life-saving vaccines, breakthrough discoveries in food and agriculture, and to more quickly distribute grants to conservation organizations on the ground. FESI was authorized and appropriated by Congress to accelerate innovation to support the global transition to affordable and reliable low-carbon energy. Its inaugural board is now tasked with choosing leadership and pursuing strategic projects that will put FESI on a path to accomplishing the goals set before it.

In order to deliver on its potential, FESI should initially select focus areas that will guide the foundation’s projects intentionally and methodically, like FFAR has done. Foundation leaders should also pursue a flexible legal arrangement with DOE that allows leaders from both entities to work together freely and flexibly. An Other Transactions Agreement is an ideal choice to structure this agreement, as it can be revisited as often as desired and frees transactions between DOE and FESI from regulations that government contracts or grants are bound by. FESI’s potential contributions to the global energy transition and national security rely on its ability to be independent enough to take risks while simultaneously pursuing projects that complement DOE’s mission. An effective legal agreement that structures the foundation’s relationship with DOE will ensure that FESI delivers impact for years to come.

Putting FESI on a Maximum Impact Path

The Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation is now a reality: an affiliated but autonomous non-profit organization authorized by Congress to support the mission of the U.S. Department of Energy and to accelerate the commercialization of energy technologies. FESI’s establishment was a vital first step, but its value depends on what happens next. In order to maximize FESI’s impact, the board and staff should think big from the start, identify unique high-leverage opportunities to complement DOE’s work, and systematically build the capacity to realize them. This memo suggests that:

- FESI should align with DOE’s energy mission,

- FESI should serve as catalyst and incubator of initiatives that advance this mission, especially initiatives that drive public-private technology partnerships, and

- FESI should develop lean and highly-networked operational capabilities that enable it to perform these functions well.

Three appendices to this memo provide background information on FESI’s genesis, excerpt its authorizing legislation, and link to other federal agency-affiliated foundations and resources about them.

Thinking Big: FESI’s Core Mission

DOE is responsible for managing the nation’s nuclear stockpile, cleaning up the legacy of past nuclear weapons development, and advancing basic scientific research as well as transforming the nation’s energy system. Although FESI’s authorizing legislation allows it to support DOE in carrying out the Department’s entire mission [Partnerships for Energy Security and Innovation Act Section b(3)(A)], the detailed description of FESI’s purposes [Sections b(1)(B)(ii), b(3)(B)] and the qualifications specified for its board members [Section b(2)(B)] signal that Congress viewed the energy mission as FESI’s primary focus. This conclusion is also supported by the hearing testimony gathered by the House Science Committee.

“Catalyz[ing] the timely, material, and efficient transformation of the nation’s energy system and secur[ing] U.S. leadership in energy technologies,” the two pillars of DOE’s energy mission, are extremely challenging responsibilities. The energy system makes up about 6% of the U.S. economy, or about $4000 per person per year, and its importance outweighs this financial value. This system keeps Americans warm in the winter and cool in the summer, gets us to our jobs and schools, and allows us to work, learn, and enjoy life. The system’s transformation to cleaner and more secure resources must not interrupt the affordable and reliable provision of these and many other vital services.

In addition to posing daunting system management challenges, the incipient energy transition is testing America’s global technological leadership. The United States now leads the world in oil and natural gas production, thanks in part to breakthroughs enabled by DOE. But the risks imposed by the use of conventional energy resources have risen. Other nations, notably China and Russia, have taken aggressive actions to establish leadership positions in new energy technologies, such as advanced nuclear power, solar panels, and lithium-ion batteries. DOE is tasked with reclaiming these fields.

DOE’s ambitious energy mission would benefit more from FESI’s support than would DOE’s other responsibilities. The energy system, unlike the nuclear stockpile or cleanup, and to a far greater extent than basic science, lies outside federal control. To transform it and secure global leadership in key technologies, DOE will have to collaborate closely with the private sector, philanthropy, and non-profits. Strengthening such collaboration, particularly to accelerate commercialization of energy technologies, is precisely the purpose specified for FESI by Congress. [Sections b(1)(B)(ii); b(3)(B)(i)]

FESI’s alignment with DOE’s energy mission should be resilient to changes in Congress and the administration. Its authorizing legislation was sponsored by members of both parties across three Congresses and won overwhelming majorities when voted on as a freestanding bill. By law, a majority of its board members must have experience in the energy sector, research, or technology commercialization [Section b(2)(B)(iii)(III)] FESI will have difficulty building strong collaborations and thus achieving its congressional mandate unless it is seen as a long-term partner with a clear and stable mission.

Filter, Catalyst, and Incubator: FESI’s Core Functions

DOE brings many assets to its mission of energy system transformation and global technological leadership. It invests over $9 billion per year in energy research, development, and demonstration, far more than any other entity in the world. Its network of 17 national laboratories and thousands of academic collaborators converts those funds into a vast store of knowledge and opportunities for real-world impact. It possesses financial and regulatory tools that allow it to shape energy markets to varying degrees.

FESI’s responsibility – and opportunity – is to help DOE use these assets to more effectively advance its energy mission. More effective public-private partnerships to accelerate technology commercialization, including such dimensions as technology maturation, new product development, and regional economic development [Sections b(3)(B)(ii), (iii), and (v)] will be an enduring priority. But the specific use-cases and projects that FESI invests in will change as the global energy landscape does. Indeed, the dynamic nature of that landscape, along with structural constraints on DOE, is a key justification for FESI’s creation. FESI must develop processes that enable it to quickly identify and act on points of leverage that enhance the impact of DOE’s assets in a rapidly-changing system.

These processes should perform three vital functions, all of which will benefit from collaboration between FESI and the national laboratory-affiliated foundations [Section b(4)(G)]. The first is to serve as a filter that helps DOE gather and sift valuable insights about the global energy landscape that the department’s leadership might otherwise miss. Information flows in a large bureaucracy like DOE are inevitably shaped by its organizational structure. The structure of DOE’s energy-focused units and the national labs is in many respects a legacy of the times in which they were established and does not map well to today’s energy system. In addition, DOE’s immense scale means that the voices of newer and less powerful players in the system, such as start-up companies and community groups, may be drowned out. Some voices of the grassroots internal to DOE and the labs may also be hard to discern at the leadership level. The Secretary of Energy’s Advisory Board helps to fill these gaps, but it is constrained by the Federal Advisory Committee Act and other laws and regulations. FESI’s flexibility, bipartisan character, and non-governmental status, bolstered by a strong relationship with the lab foundations, will allow it to recognize DOE’s blind spots, whether internal or external.

FESI should draw on this new or neglected information to perform the second function: catalyzing actionable opportunities that advance DOE’s energy mission. It can develop these opportunities (jointly, as appropriate, with one or more lab foundations) by convening a broad range of stakeholders in formats that DOE cannot effectively utilize and at a pace that DOE cannot match. For example, a group of firms in an emerging clean energy industry may identify a shared technological need that international competitors are pursuing aggressively. FESI could support these firms to articulate their need, identify DOE-affiliated assets that could address it, and rapidly assemble a public-private partnership that aligns the two. Such a partnership might have a regional focus and engage state and local governments and regionally-focused philanthropy as well. If FESI’s information filter were to pick up unrecognized obstacles to effective community engagement or lack of attention to end-user priorities, it could assemble cross-sectoral partnerships appropriate to those opportunities. The catalyst function could be particularly important for crisis response, when speed and agility are essential, and DOE’s formal processes are likely to slow the agency down.

FESI’s third core function should be to incubate and ultimately spin out the initiatives that it has catalyzed. The process of assembling each initiative will require FESI to provide basic administrative support, like internal communication and coordination. FESI should frequently go several steps further by raising seed funding for each initiative, particularly from non-governmental sources, and serving as its external champion. FESI should not, however, become the permanent home of mature partnerships. The managerial demands imposed by carrying out this function risk undermining the filter and catalyst functions. Spinning out the successes will permit FESI’s leadership to hunt more effectively for new opportunities. The destination for the spinoffs might be new or expanded programs within DOE, an existing non-profit like an industry consortium or community foundation, or a new organization.

Lean and Intensely Networked: FESI’s Operational Capabilities

FESI’s high ambition, dynamic functions, and unique institutional position determine the capabilities it will need to operate effectively. Above all, it must be plugged intensively into a broad network that spans the energy industry; DOE and the national labs; states, communities, and Congress; and philanthropy. FESI will only be able to spot what DOE could do better by having a savvy understanding of what DOE is already doing and what its potential partners want to be doing. FESI must be able to gather and interpret this information continuously at a modest cost, which puts a premium on networking.

FESI board members must be vital nodes of its network. FESI’s authorizing statute specifies that the board represent “a broad cross-section of stakeholders.” The members will hold positions that provide insights and contacts of value to FESI and should be selected to build and maintain the network’s breadth. The board’s ex officio representatives from DOE will provide complementary perspectives and connections inside the Department. FESI’s staff will only have the knowledge and resources required to do their jobs well if the entire board is active and engaged (but not micro-managing the staff).

FESI’s staff should be led by an executive director who is responsible for its day-to-day operations [Section b(5)(A)] and has high credibility throughout the energy system and with both political parties. Staff members should bring sector-spanning networks to the organization that leverage those of the board. Even more important, the staff must possess the entrepreneurial skills, and technological and market knowledge, to recognize and act on promising opportunities. Prior experience in business, social, or public entrepreneurship – building new companies, non-profit organizations, and government programs – is likely to be particularly valuable to FESI.

Running lean should be a value for a FESI and will likely be a necessity as well. The value lies in taking initiative and moving quickly. The necessity arises from the likely limits on federal appropriations for operations, which are authorized at $3 million annually [Section b(11)] and may not rise to that level. To be sure, FESI must raise resources from non-federal sources – indeed, that will be one of its core challenges. But those resources are likely to be much easier to raise if they are devoted to projects rather than operations.

Finally, FESI will need to mitigate risks to its reputation that might arise from real and perceived conflicts of interest of the board and staff as well as from the images and interests of its potential partners. A pristine reputation will be vital to maintaining the confidence of DOE, Congress, and external stakeholders. FESI should seek to reduce the cost in money and time of rigorous vetting and disclosure, but ultimately this investment is an essential one that must be borne.

Appendix 1. A Brief Prehistory of FESI

- The immediate genesis of FESI’s authorizing legislation was idea #22 in this 2016 ITIF report.

- ITIF and its partners socialized the concept beginning in the 115th Congress, including at this 2018 event, which featured Reps. Fleischmann (current chair of the House Energy & Water Development appropriations subcommittee) and Lujan (now Senator from New Mexico)

- During the same Congress, Rep. Lujan and Sen. Coons authored the first bills to authorize a DOE-affiliated foundation, which were co-sponsored on a bipartisan basis, a pattern that was sustained through the concept’s ultimate passage.

- Jetta Wong took the lead role along with me in driving the foundation initiative for ITIF during the 116th Congress (2019-2020). That work included two stakeholder workshops and extensive interview and documentary research, leading to our 2020 “Mind the Gap” report, which provides our fullest vision for the foundation’s potential role in innovation and commercialization.

- In July 2020, Jetta testified on the foundation before the House Science Committee along with Jennifer States (Maritime Blue), Farah Benahmed (Breakthrough Energy), Emily Reichert (Greentown Labs), and Lee Cheatham (PNNL)

- Our work led to an appropriations report that required DOE to sponsor a study by the National Academy of Public Administration, which was issued in January 2021. This report has a good round-up of other agency foundations, as does the 2019 CRS report on the topic

- The Partnerships for Energy Security and Innovation Act, sponsored by Rep. Stansbury and Sen. Coons in the 117th Congress, won an 83-14 vote in the Senate in 2021, passed the House in early 2022, and was ultimately incorporated into the August 2022 CHIPS and Science Act. The Act passed just after Jetta joined the administration; I partnered with Kerry Duggan of SustainabiliD for the next phase of work. Our August 2022 blog post provides a good synopsis of the effort up to the bill’s passage.

- With SustainabiliD and later with the Federation of American Scientists and with support from Schmidt Futures and Breakthrough Energy, the “Friends of FESI” focused on sustaining support for FESI and generating project ideas.

- Jetta joined the panel on FESI at the 2023 ARPA-E summit, where DOE held its first public events on FESI, and we participated in the workshop that DOE organized there.

- We responded to DOE’s RFI on FESI, along with several other NGOs. We also focused on FESI in a response to to DOE’s RFI on place-based innovation.

- We developed a set of broad use-cases and held two workshops, one on geothermal energy and the other on “fast track” commercialization.

- We worked with supporters and allies to secure FESI’s appropriation

Appendix 2. Other Federal Agency-Affiliated and National Laboratory Foundations

Numerous federal agencies have Congressionally authorized non-governmental foundations that work with them to advance their missions. The National Park Foundation (NPF) is the oldest, dating back to 1935. Anyone who wants to support a particular national park, or the system as a whole, can do so through a contribution to NPF. Similarly, donors who care about public health can give to the CDC Foundation (CDC Foundation) or the Foundation for NIH (FNIH). A 2021 report by the National Academy of Public Administration (NAPA), which recommended establishing a foundation for DOE, reviews a wide range of agency-related foundations, as does the 2020 ITIF “Mind the Gap” report and a 2019 CRS report.

As the NAPA report describes, all of these foundations leverage federal investment with private contributions to complement and supplement their agency affiliate, while guarding against potential conflict of interest. Yet, more remarkable than this commonality among is the foundations’ diversity. Each seeks to complement and supplement its partner agency, but because each agency has a different mission, structure, and functions, each affiliated foundation is unique.

FESI will likely have much in common with the FNIH. Like NIH, DOE is a major research funder that advances a critical national mission. Like NIH, DOE must rely on the private sector to turn advances made possible by the R&D it funds into technologies that make a difference on the ground. FNIH’s contributions to fighting the pandemic illustrate how having a flexible non-profit partner for an agency can advance the agency’s mission in a moment of need. Its Pandemic Response Fund and Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines (ACTIV) partnership with NIH, private firms, other federal agencies, and allied governments, aids the search for treatments and vaccines and prepares the nation to defend against future pandemics.

The Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, which is affiliated with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, is another potential source of inspiration and learning for FESI. One notable innovation made by FFAR is its use of prizes and challenges, along with more traditional competitive, cost-shared grants. To ensure technologies can scale, FFAR brings industry experts into its project design and administration. In a review of the FFAR’s progress, the Boston Consulting Group (BGC) found that FFAR’s “Congressional funding allows it to bring partners to the table and serve as an independent, neutral third party.”

Links to agency-affiliated foundations not linked above:

- Foundation for America’s Public Lands (Interior/Bureau of Land Management)

- Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine (DOD)

- National Association of Veterans’ Research and Education Foundations (VA)

- National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (Interior/Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA)

- National Forest Foundation (Interior/US Forest Service)

- Reagan-Udall Foundation for the FDA (Food and Drug Administration)

Appendix 3. Selected Provisions of FESI’s Authorizing Statute1

Partnerships for Energy Security and Innovation (42 USC 19281)

CHIPS AND SCIENCE ACT SEC. 10691. FOUNDATION FOR ENERGY SECURITY AND INNOVATION

(b)(1)(B) MISSION.—The mission of the Foundation shall be—

(i) to support the mission of the Department; and

(ii) to advance collaboration with energy researchers, institutions of higher education, industry, and nonprofit and philanthropic organizations to accelerate the commercialization of energy technologies.

(b)(2)(B)(iii)(II) REPRESENTATION.—The appointed members of the Board shall reflect a broad cross-section of stakeholders from academia, National Laboratories, industry, nonprofit organizations, State or local governments, the investment community, and the philanthropic community.

(III) EXPERIENCE.—The Secretary shall ensure that a majority of the appointed members of the

Board— (aa)(AA) has experience in the energy sector; (BB) has research experience in the

energy field; or (CC) has experience in technology commercialization or foundation operations;

and (bb) to the extent practicable, represents diverse regions, sectors, and communities.

(b)(3) PURPOSES.—The purposes of the Foundation are—

(A) to support the Department in carrying out the mission of the Department to ensure the security and prosperity of the United States by addressing energy and environmental challenges through transformative science and technology solutions; and

(B) to increase private and philanthropic sector investments that support efforts to create, characterize, develop, test, validate, and deploy or commercialize innovative technologies that address crosscutting national energy challenges, including those affecting minority, rural, and other

underserved communities, by methods that include—

(i) fostering collaboration and partnerships with researchers from the Federal Government, State

governments, institutions of higher education, including historically Black colleges or universities,

Tribal Colleges or Universities, and minority-serving institutions, federally funded research and development centers, industry, and nonprofit organizations for the research, development, or commercialization of transformative energy and associated technologies;

(ii) strengthening and sharing best practices relating to regional economic development through scientific and energy innovation, including in partnership with an Individual Laboratory-Associated Foundation;

(iii) promoting new product development that supports job creation;

(iv) administering prize competitions—

(I) to accelerate private sector competition and investment; and

(II) that complement the use of prize authority by the Department;

(v) supporting programs that advance technology maturation, especially where there may be gaps in Federal or private funding in advancing a technology to deployment or commercialization from the prototype stage to a commercial stage;

(vi) supporting efforts to broaden participation in energy technology development among individuals from historically underrepresented groups or regions; and

(vii) facilitating access to Department facilities, equipment, and expertise to assist in tackling national challenges.

(b)(4)(G) INDIVIDUAL AND FEDERAL LABORATORY-ASSOCIATED FOUNDATIONS.—

(ii) SUPPORT.—The Foundation shall provide support to and collaborate with covered foundations.

(iv) AFFILIATIONS.—Nothing in this subparagraph requires—

(I) an existing Individual Laboratory-Associated Foundation to modify current practices or

affiliate with the Foundation

(b)(5)(I) INTEGRITY.—

(i) IN GENERAL.—To ensure integrity in the operations of the Foundation, the Board shall develop and enforce procedures relating to standards of conduct, financial disclosure statements, conflicts of interest (including recusal and waiver rules), audits, and any other matters determined appropriate by the Board.

(b)(6) DEPARTMENT COLLABORATION.—

(A) NATIONAL LABORATORIES.—The Secretary shall collaborate with the Foundation to develop a process to ensure collaboration and coordination between the Department, the Foundation, and National Laboratories

Get Ready, Get Set, FESI!: Putting Pilot-Stage Clean Energy Technologies on a Commercialization Fast Track

It may sound dramatic, but “Valleys of Death” are delaying the United States’ technology development progress needed to achieve the energy security and innovation goals of this decade. As emerging clean energy technologies move along the innovation pipeline from first concept to commercialization, they encounter hurdles that can prove to be a death knell for young startups. These “Valleys of Death” are gaps in funding and support that the Department of Energy (DOE) hasn’t quite figured out how to fill – especially for projects that require less than $25 million.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, almost 35% of CO2 emissions to avoid require technologies that are not yet past the demonstration stage. It’s important to note that this share is even higher in harder-to-decarbonize sectors like long-haul transportation and heavy industry. To reach this metric, a massive effort within the next ten years is needed for these technologies to reach readiness for deployment in a timely manner.

Although programs exist within DOE to address different barriers to innovation, they are largely constrained to specific types of technologies and limited in the type of support they can provide. This has led to a discontinuous support system with gaps that leave technologies stranded as they wait in the “valleys of death” limbo. A “Fast Track” program at DOE – supported by the CHIPS and Science-authorized Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) – would remove obstacles for rapidly-growing startups that are hindered by traditional government processes. FESI is uniquely positioned to be a valuable tool for DOE and its allies as they seek to fill the gaps in the technology innovation pipeline.

Where does FAS come in?

The Department of Energy follows the lead of other agencies that have established agency-affiliated foundations to help achieve their missions, like the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) and the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR). These models have proven successful at facilitating easier collaboration between agencies and philanthropy, industry, and communities while guarding against conflicts of interest that might arise from such collaboration. Notably, in 2020, the FNIH coordinated a public-private working group, ACTIV, between eight U.S. government agencies and 20 companies and nonprofits to speed up the development of the most promising COVID-19 vaccines.

As part of our efforts to support DOE in standing up its new foundation with the Friends of FESI Initiative, FAS is identifying potential use cases for FESI – structured projects that the foundation could take on as it begins work. The projects must forward DOE’s mission in some way, with a particular focus on accelerating clean energy technology commercialization.

In early April, we convened leaders from DOE, philanthropy, industry, finance, the startup community, and fellow NGOs to workshop a few of the existing ideas for how to implement a Fast Track program at DOE. We kicked things off with some remarks from DOE leaders and then split off into four breakout groups for three discussion sessions.

In these sessions, participants brainstormed potential challenges, refinements, likely supporters, and specific opportunities that each idea could support. Each discussion was focused around what FESI’s unique value-add was for each concept and how best FESI and DOE could complement each other’s work to operationalize the idea. The four main ideas are explored in more detail below.

Support Pilot-scale Technologies on the Path to Commercialization

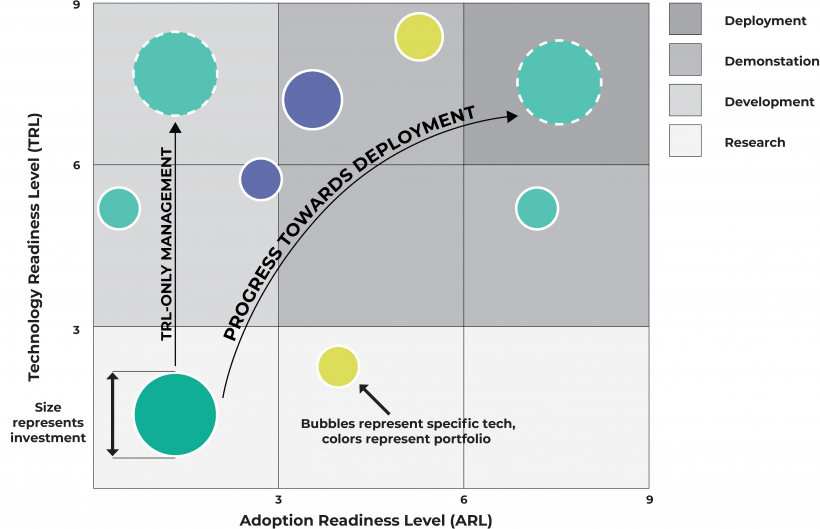

The technology readiness level (TRL) framework has been used to determine an emerging technology’s maturity since NASA first started using it in the 1970s. The TRL scale begins at “1” when a technology is in the basic research phase and ends at “9” when the technology has proven itself in an operating environment and is deemed ready for full commercial deployment.

However, getting to TRL 9 alone is insufficient for a technology to actually get to demonstration and deployment. For an emerging clean technology to be successfully commercialized, it must be completely de-risked for adoption and have an established economic ecosystem that is prepped to welcome it. To better assess true readiness for commercial adoption, the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) at the Department of Energy (DOE) uses a joint “TRL/Adoption Readiness Level (ARL)” framework. As depicted by the adoption readiness level scale below, a technology’s path to demonstration and deployment is less linear in reality than the TRL scale alone suggests.

Source: The Office of Technology Transitions at the Department of Energy

There remains a significant gap in federal support for technologies trying to progress through the mid-stages of the TRL/ARL scales. Projects that fall within this gap require additional testing and validation of their prototype, and private investment is often inaccessible until questions are answered about the market relevance and competitiveness of the technology.

FESI could contribute to a pilot-scale demonstration program to help small- and medium-scale technologies move from mid-TRLs to high-TRLs and low to medium ARLs by making flexible funding available to innovators that DOE cannot provide within its own authorities and programs. Because of its unique relationship as a public-private convener, FESI could reach the technologies that are not mature enough, or don’t qualify, for DOE support, and those that are not quite to the point where there is interest from private investors. It could use its convening ability to help identify and incubate these projects. As it becomes more capable over time, FESI might also play a role in project management, following the lead of the Foundation for the NIH.

Leverage the National Labs for Tech Maturation

The National Laboratories have long worked to facilitate collaboration with private industry to apply Lab expertise and translate scientific developments to commercial application. However, there remains a need to improve the speed and effectiveness of collaboration with the private sector.

A Laboratory-directed Technology Maturation (LDTM) program, first ideated by the EFI Foundation, would enable the National Labs to allocate funding for technology maturation projects. This program would be modeled after the highly successful DOE Office of Science Laboratory-directed Research and Development (LDRD) program and it would focus on taking ideas at the earliest Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) and translating them to proof of concept—from TRL 1 and 2 to TRL 3. This program would translate scientific discoveries coming out of the Labs into technology applications that have great potential for demonstration and deployment. FESI could assist in increasing the effectiveness of this effort by lowering the transaction costs of working with the private sector. It could also be a clearinghouse for LDTM-funded scientists who need partners for their projects to be successful, or could support an Entrepreneur-in-Residence or entrepreneurial postdoc program that could house such partners.

While FESI would be a practical convener of non-federal funding for this program, the magnitude of the funding needed to establish this program may not be well-suited for an initial project for the foundation to take on. It is estimated that each project would be in the ballpark of $5-20 million, and funding a full portfolio, which private sponsors are more likely to be interested in, is a nine-figure venture. Supporting a LDTM program is a promising idea for further down the line as FESI grows and matures.

Align Later-stage R&D Market Needs with Corporate Interest via a Commercialization Consortium

Industry and investors often struggle to connect with government-sponsored technologies that fit their plans and priorities. At the same time, government-sponsored researchers often struggle to navigate the path to commercialization for new technologies.

Based on a model widely-used by the Department of Defense (DOD), an open consortium is a mechanism and means to convene industry and highlight relevant opportunities coming out of DOE-funded work. The model creates an accessible and flexible pathway to get U.S.-funded inventions to commercial outcomes.

FESI could function as the Consortium Management Organization (CMO), pictured below, to help structure interactions and facilitate communications between DOE sponsors and award recipients while freeing government staff from “picking winners.” As the CMO, FESI would issue task orders and handle contracting per the consortium agreement, which would be organized under DOE’s other transactions authority (OTA). In this model, FESI could work with DOE staff in applied R&D offices and OCED to identify opportunities and needs in the development pipeline, and in parallel work with consortium members (including holders of DOE subject inventions, industry partners, and investors) to build teams and scope projects to advance targeted technology development efforts.

This consortium could help work out the kinks in the pipeline to ensure that successful technologies in the applied offices have sufficient “runway” to reach TRL 7, and that OCED has a healthy pipeline of candidate technologies for scaled demonstrations. FESI could mitigate the offtake risk that is known to stall first-of-a-kind projects, like financing a lithium extraction project, for example. Partners in industry and the investment community will be aligned, and potentially provide cost share, in order to gain access to technologies emerging from DOE subject inventions.

The Time is Right

This workshop comes at a prime time for FESI. The Secretary of Energy appointed the inaugural FESI board—composed of 13 leaders in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors—in mid-May. In the coming months, the board will formally set up the organization, hire staff, adopt an agenda, and begin to pursue projects that will make a real impact to advance DOE’s mission. As Friends of FESI, we want to see the foundation position itself for the grand impact it is designed to have.

The above proposals are actionable and affordable projects that a young FESI is uniquely-positioned to achieve. That said, supporting pilot-stage demonstrations is only one area where FESI can make an impact. If you have additional ideas for how FESI could leverage its unique flexibility to accelerate the clean energy transition, please reach out to our team at fesifriends@fas.org. You can also keep up with the Friends of FESI Initiative by signing up for our email newsletter. Email us!

Building a Firm Foundation for the DOE Foundation: It All Starts with a Solid Board

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has a vital mission: “to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions.” In 2022’s CHIPS and Science Act, Congress gave DOE a new partner to accelerate its pursuit of this mission: the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI). As ‘Friends of FESI’ we want to see this new foundation set up from day one to successfully fulfill the promise of its large impact.

Once fully established, FESI will be an independent 501(c)3 non-profit organization with a complementary relationship to DOE. It will raise money from non-governmental sources to support activities of joint interest to the Department and its constituents, such as accelerating commercialization of next-generation geothermal power and bridging gaps in the clean energy technology innovation pipeline.

Judging by the success of other agency-affiliated foundations that served as a template for FESI, the potential for the Foundation’s impact is hefty. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, chartered by Congress to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service, for instance, is the nation’s largest non-governmental conservation grant-maker. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the NFWF awarded $1.3 billion to 797 projects that will generate a total conservation impact of $1.7 billion.

FESI’s creation is timely. As the U.S. races to net-zero, the International Energy Agency estimates that at least $90 billion of public funding needs to be raised by 2026 for an efficient portfolio of demonstration projects. For perspective, the most recent yearly budget for the entire DOE is just slightly more than half of that number. Non-DOE funding to support innovation is essential to ensure that energy remains affordable and reliable. DOE’s mission is a vital national interest, and the Department needs all the help it can get. The stronger FESI is, the more it will be able to help.

This week, Secretary of Energy Granholm took the first official step to create FESI by appointing its inaugural board. The board consists of 13 accomplished members whose backgrounds span the nation’s regions and communities and who have deep experience in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors.

A strong founding board is an essential ingredient in FESI’s success, and we are pleased to see that its members reflect the bipartisan support that FESI has had since legislation to form it was first introduced. While non-partisan technical and market expertise is vital to make objective judgments about hiring and investments, bipartisan relationships will ensure that FESI is sustained through changes of partisan control of Congress and the presidency.

Another key to FESI’s success will be stringent conflict of interest rules. Public-private partnerships, like those that FESI will foster, are always at risk of being subverted to pursue only private ends. It is equally important for FESI to also prioritize transparency and oversight of compliance with these rules to avoid the appearance of any conflict of interest that would undermine its progress.

What Happens Next?

In the coming weeks and months, the FESI board will hire a CEO and other leaders. This board will set FESI’s agenda and initial priorities, and later down the line, it will also eventually appoint its own successors. Its imprint will be long-lasting. The organizational culture the board creates will strongly influence whether FESI will make a real difference for energy, climate, science, national security, and the economy. As ‘Friends of FESI’ we are eager to see what the FESI board decides to take on first.

To learn more about the Inaugural FESI Board nominees, check out the DOE press release here.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) Applauds the Newly Announced Board Selected to Lead the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI)

FAS eager to see the Board set an ambitious agenda that aligns with the potential scale of FESI’s impact

Washington, D.C. – May 9, 2024 – Earlier today Secretary of Energy Granholm took the first official step to stand up the Department of Energy-affiliated non-profit Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) by appointing its inaugural board. Today the “Friends of FESI” Initiative of the nonpartisan, non-profit Federation of American Scientists (FAS) steps forward to applaud the Secretary, congratulate the new board members, and wish FESI well as it officially begins its first year. The Inaugural FESI Board consists of 13 accomplished members whose backgrounds span the nation’s regions and communities and who have deep experience in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors. It includes:

- Jason Walsh, BlueGreen Alliance

- Nancy Pfund, DBL Partners

- Rita Baranwal, Westinghouse Electric

- Vicky Bailey, Anderson Stratton

- Mike Boots, Breakthrough Energy

- Miranda Ballentine, Clean Energy

- Stephen Pearse, Yucatan Rock

- Noel Bakhtian, Bezos Earth Fund

- Mung Chiang, President of Purdue University

- Noelle Laing, Builder’s Initiative Foundation

- Katie McGinty, Johnson Controls

- Tomeka McLeod, Hydrogen VP at bp

- Rudy Wynter, National Grid NY

Since the CHIPS and Science Act authorized FESI in 2022, FAS, along with many allies and supporters who collectively comprise the “Friends of FESI,” have been working to enable FESI to achieve its full potential as a major contributor to the achievement of DOE’s vital goals. “Friends of FESI” has been seeking projects and activities that the foundation could take on that would advance the DOE mission through collaboration with private sector and philanthropic partners.

“FAS enthusiastically celebrates this FESI milestone because, as one of the country’s oldest science and technology-focused public interest organizations, we recognize the scale of the energy transition challenge and the urgency to broker new collaborations and models to move new energy technology from lab to market,” says Dan Correa, CEO of FAS. “As a ‘Friend of FESI’ FAS continues our outreach amongst our diverse network of experts to surface the best ideas for FESI to consider implementing.” The federation is soliciting ideas at fas.org/fesi, underway since FESI’s authorization.

FESI has great potential to foster the public-private partnerships necessary to accelerate the innovation and commercialization of technologies that will power the transition to clean energy. Gathering this diverse group of accomplished board members is the first step. The next is for the FESI Board to pursue projects set to make real impact. Given FESI’s bipartisan support in the CHIPS & Science Act, FAS hopes the board is joined by Congress, industry leaders and others to continue to support FESI in its initial years.

“FESI’s establishment is a vital initial step, but its value will depend on what happens next,” says David M. Hart, a professor at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and leader of the “Friends of FESI” initiative at FAS. “FESI’s new Board of Directors should take immediate actions that have immediate impact, but more importantly, put the foundation on a path to expand that impact exponentially in the coming years. That means thinking big from the start, identifying unique high-leverage opportunities, and systematically building the capacity to realize them.”

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Resources

Building a Firm Foundation for the DOE Foundation: It All Starts with a Solid Board

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-board-launch/

FAS use case criteria:

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-priority-use-cases/

FAS open call for FESI ideas:

https://fas.org/publication/share-an-idea-for-what-fesi-can-do-to-advance-does-mission/

DOE announcing FESI board:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-appoints-inaugural-board-directors-groundbreaking-new-foundation

DOE release announcing FESI:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-launches-foundation-energy-security-and-innovation

Geothermal is having a moment. Here’s how the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation can make sure it lasts.

Geothermal energy is having a moment. The Department of Energy has made it a cornerstone of their post-BIL/IRA work – announcing an Enhanced Geothermal Earthshot last year and funding for a new consortium this year, along with additional funding for the Frontier Observatory for Research in Geothermal Energy (FORGE), Utah’s field lab.

It’s not just government – companies hit major milestones in commercial applications of geothermal this year. Fervo Energy launched a first-of-its-kind next-generation geothermal plant, using technology it developed this year. Project Innerspace, a geothermal development organization, recently announced a partnership with Google to begin large-scale mapping and subsurface data collection, a project that would increase understanding of and access to geothermal resources. Geothermal Rising recently hosted their annual conference, which saw record numbers of attendees.

But despite the excitement in these circles, the uptake of geothermal energy broadly is still relatively low, with only 0.4% of electricity generated in the U.S. coming from geothermal.

There are multiple reasons for this – that despite its appeal as a clean, firm, baseload energy source, geothermal has not exploded like its supporters believe it can and should. It has high upfront costs, is somewhat location dependent, and with the exception of former oil and gas professionals, lacks a dedicated workforce. But there are a range of actors in the public and private sector who are already trying to overcome these barriers and take geothermal to the next level with new and creative ideas.

One such idea is to use DOE’s newly authorized Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) to convene philanthropy, industry, and government on these issues. At a recent FAS-hosted workshop, three major, viable use cases for how FESI can drive expansion of geothermal energy rose to the surface as the result of this cross-sector discussion. The foundation could potentially oversee: the development of an open-source database for data related to geothermal development; agreements for cost sharing geothermal pilot wells; or permitting support in the form of technical resource teams staffed with geothermal experts.

Unlocking Geothermal Energy

DOE’s Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) was authorized by the CHIPS and Science Act and is still in the process of being stood up. But once in action, FESI could provide an opportunity for collaboration between philanthropy, industry, and government that could accelerate geothermal.

As part of our efforts to support DOE in standing up its new foundation with the Friends of FESI initiative, FAS is identifying potential use cases for FESI – structured projects that the foundation could take on as it begins work. The projects must forward DOE’s mission in some way, with particular focus on clean energy technology commercialization. We have already received a wide range of ideas for how FESI can act as a central hub for collaboration on specific clean energy technologies; how it can support innovative procurement and talent models for government; or how it can help ensure an equitable clean energy transition.

In early October, FAS had the opportunity to host a workshop as part of the 2023 Geothermal Rising Conference. The workshop invited conference attendees from nonprofits, companies, and government agencies of all levels to come together to brainstorm potential projects that could forward geothermal development. The workshop centered on four major ideas, and then invited attendees to break out into small groups, rotating after a period of time to ensure attendees could discuss each idea.

The workshop was successful, adding depth to existing ideas. The three main ideas that came out of the workshop – an open source geothermal database, cost sharing pilot wells, and permitting support – are explored in more detail below.

Open-source database for subsurface characterization

One of the major barriers to expanded geothermal development is a lack of data for use in exploration. Given the high upfront costs of geothermal wells, developers need to have a detailed understanding of subsurface conditions of a particular area to assess the area’s suitability for development and reduce their risk of investing in a dead end. Useful data can include bottom hole temperatures, thermal gradient, rock type, and porosity, but can also include less obvious data – information on existing water wells or transmission capacity in a particular area.

These data exist, but with caveats: they might be proprietary and available for a high cost, or they might be available at the state level and constrained by the available technical capacity in those offices. Data management standards and availability also vary by state. The Geothermal Data Repository and the US Geological Survey manage databases as well, but utility of and access to these data sources is limited.

With backing from industry and philanthropic sources, and in collaboration with DOE, FESI could support collection, standardization, and management of these data sources. A great place to begin would be making accessible existing public datasets. Having access to this data would lower the barrier to entry for geothermal start-ups, expand the types of geothermal development that exist, and remove some of the pressure that state and federal agencies feel around data management.

Cost sharing pilot wells

After exploration, the next stage in a geothermal energy source’s life is development of a well. This is a difficult stage to reach for companies: there’s high risk, high investment cost, and a lack of early equity financing. In short, it’s tough for companies to scale up, even if they have the expertise and technology. This is also true across different types of geothermal – just as much in traditional hydrothermal as in superhot or enhanced geothermal.

One way FESI could decrease the upfront costs of pilot wells is by fostering and supporting cost-share agreements between DOE, companies, and philanthropy. There is a precedent for this at DOE – from loan programs in the 1970s to the Geothermal Resource Exploration and Definition (GRED) programs in the 2000s. Cost-share agreements are good candidates for any type of flexible financial mechanism, like the Other Transactions Authority, but FESI could provide a neutral arena for funding and operation of such an agreement.

Cost share agreements could take different forms: FESI could oversee insurance schemes for drillers, offtake agreements, or centers of excellence for training workforces. The foundation would allow government and companies to pool resources in order to share the risk of increasing the number of active geothermal projects.

Interagency talent support for permitting

Another barrier to geothermal development (as well as to other clean energy technologies) is the slow process of permitting, filled with pitfalls. While legislative permitting reform is desperately needed, there are barriers that can be addressed in other ways. One of these is by infusing new talent: clean energy permitting applications require staff to assess and adjudicate them. Those staff need encyclopedic knowledge of various state, local, tribal, and federal permitting laws and an understanding of the clean energy technology in question. The federal government doesn’t have enough people to process applications at the speed the clean energy transition needs.

FESI could offer a solution. With philanthropic and private support, the foundation could enable fellowships or training programs to support increased geothermal (or other technological) expertise in government. This could take the form of ‘technical resource teams,’ or experts who can be deployed to agencies handling geothermal project permitting applications and use their subject matter knowledge to move applications more quickly through the pipeline.

The Bottom Line

These ideas represent a sample in just one technology area of what’s possible for FESI. In the weeks to come, the Friends of FESI team will work to develop these ideas further and also start to gauge interest from philanthropies in supporting them in the future. If you’re interested in contributing to or potentially funding these ideas, please reach out to our team at fesifriends@fas.org. If you have other ideas for what FESI could work on or just want to keep up with FESI, sign up for our email newsletter here.

Share an Idea For What FESI Can Do To Advance DOE’s Mission

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is seeking to engage experts who can leverage their knowledge to propose projects and use-cases for FESI to consider. Priority use cases areas include but are not limited to:

- Catalyzing industry-led consortia

- Supporting coordinated procurement

- Strengthening innovation incentives

- Supporting regional innovation ecosystems

- Convening venture and impact investors

- Piloting or expanding DOE innovation programs with non-DOE funding

- Collaborating with the National Lab Foundations

- Responding quickly to crises

- Enabling communities to participate in clean energy innovation

- Read more about priority use cases here.

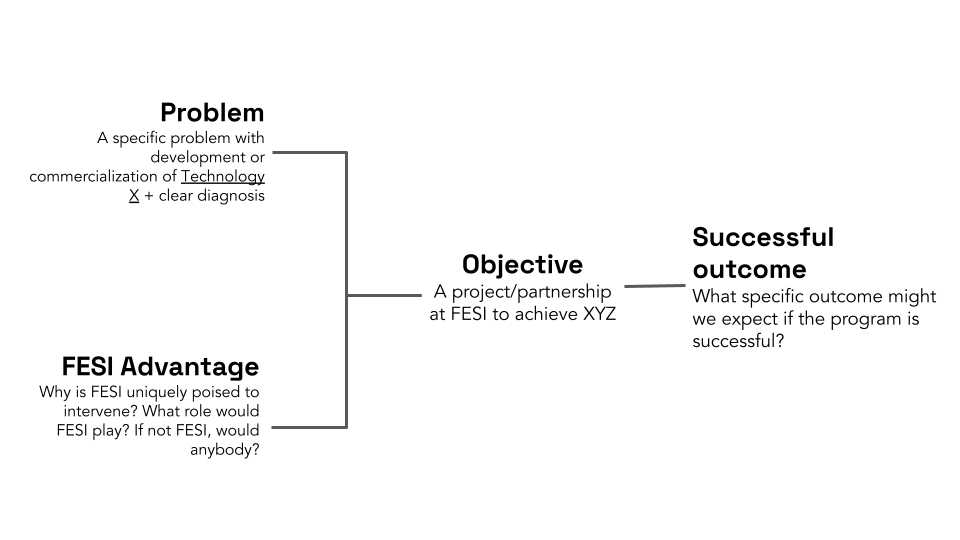

What We’re Looking For (and what we’re not)

Please submit your initial project designs in the form of wireframes. A wireframe is an outline of a potential project that demonstrates its fit and potential for impact. The template below reflects the components of a wireframe. The submission form can be found at the end of this page.

When filling out your wireframe, we ask you aim to avoid the following pitfalls to ensure that ideas are properly scoped, appropriately ambitious, and are in line with the agency’s goals:

- Failure to align to mission. Your proposal should be aligned with DOE’s mission, particularly catalyzing the timely, material, and efficient transformation of the nation’s energy system; securing U.S. leadership in energy technologies; and maintaining a vibrant U.S. effort in science and engineering as a cornerstone of economic prosperity

- Going alone. FESI’s central role is to cultivate long-lasting external partnerships and cross-sector activities. Your proposal should not rely on FESI as the sole funder or service provider, except in places where a first-in, crowd-in approach is needed.

- No clear diagnosis of the problem. Your project proposal should identify points of leverage where FESI can make a big impact on a complex problem.

- Duplication of efforts. While FESI can expand upon successful DOE programs that would amplify their benefits for the public , your proposal should not duplicate existing DOE efforts.

Sample Idea

Problem

Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) technology has advanced significantly in recent years, but there is a lack of accurate, public information on heat flows accessible to would-be developers.*

FESI Advantage

FESI could fund the creation and maintenance of a public platform on global heat flows and related knowledge. To do so they can leverage the expertise at DOE’s Utah FORGE experiment and Geothermal Technologies Office while also convening academics, geothermal startups, legacy oil/natural gas firms, and nonprofits.

Program Objective

A partnership between FESI, Project InnerSpace, and Global Heat Flow to update, publish, and maintain a public database of heat flow maps.

Activities

- Kickoff convening of relevant stakeholders, identification of core problems to be overcome in creating a mapping database. Outreach to discover any critically missing information.

- Funding of a team of researchers to complete scope of work identified at kickoff.

- Popularization of research findings and resources to help new startups and projects make the most of available information.

Successful Outcome

Lead time from exploration/discovery to project initiation reduced by X amount. Y number of new projects or investments announced.

*This idea inspired by the partnership between Project Innerspace and the International Heat Flow Commission.

FESI >> Priority Use Cases

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is seeking to engage experts who can leverage their knowledge to propose projects and use-cases for FESI to consider. Priority use cases areas include but are not limited to:

1. Catalyzing problem-focused industry-led consortia. DOE has often worked on precompetitive technologies with industrial consortia. Once they are up and running, these consortia can be very productive, but their initial implementation tends to be slow and saddled by red tape. Like the Foundation for the NIH, FESI could launch consortia quickly and assist them to transition into stable, permanent relationships with DOE.

2. Supporting coordinated procurement, advance market commitments, and other sources of demand to stimulate innovation uptake. Early adoption of new technologies spurs their improvement and lowers their cost. FESI could work with DOE to identify uptake opportunities, while simultaneously collaborating with non-governmental funders who might buy down the costs. FESI’s network could become a repository of design expertise and operational know-how for demand-side energy and climate innovation policy.

- H2 Global Foundation (Germany)

- First Movers Coalition

3. Strengthening incentives to broaden the pool of innovators. The nation’s energy challenges demand an “all-of-society” response. The more diverse the communities that are advancing solutions (rural to urban, coast to coast), the better. Learning from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, FESI could work with DOE to assess the pool of innovators and design programs, including prize competitions, to broaden it.

- Egg-Tech Prize (FFAR)

- Carbon Removal X Prize (X Prize)

4. Collaborating to strengthen regional innovation ecosystems. Regions are increasingly building economic development strategies around clean energy. DOE has not had a strong regional presence in the past, but now has a Congressional mandate to build one. Working with the national laboratory foundations, universities, and other partners, FESI could convene initiatives to strengthen regional ecosystems.

- Coordinating with NSF Engines and EDA Tech Hubs

- Coordinating with and learning from state innovation ecosystems

5. Convening impact and venture investors. Early-stage investors have a granular understanding of the technological opportunities, competitive landscape, and commercialization challenges facing clean energy start-ups. FESI could bring this community together with DOE managers and national laboratory experts to identify promising areas for public-private partnerships as well as pitfalls that may impede participation of entrepreneurs in such efforts.

- Building on ARPA-E’s successful annual Summit

6. Piloting or expanding DOE innovation programs with non-DOE funding. DOE has fielded an array of creative programs that foster technology commercialization, such as Lab-Embedded Entrepreneurship Program, Cradle 2 Commerce, Lab Partnering Service, Small Business Vouchers, and Energy I-Corps. The demand for these programs is often stronger than federal funding can accommodate. FESI could enable donors to expand capacity, as the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation has done for federal conservation programs.

7. Responding quickly to crises. The global energy and climate situation is volatile, and crises are inevitable. As the CDC Foundation showed in its response to covid, FESI could act quickly in such situations, laying the basis for a longer-lasting response from DOE. Key activities might include public communication about the performance of the energy system and coordination with non-federal actors, especially in philanthropy and business.