Federation of American Scientists among leading voices for federal policy action at White House Summit on Extreme Heat

Summit comes on heels of record 2024 summer heat; convenes experts on strategies to address this nationwide threat

Washington, D.C. – September 13, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS), the non-partisan, nonprofit science think tank dedicated to deploying evidence-based policies to address national threats, is today participating in the White House Summit on Extreme Heat.

This Summit, announced by President Biden earlier this summer, will bring together local, state, Tribal, and territorial leaders and practitioners to discuss how to drive further locally-tailored and community-driven actions to address extreme heat. FAS has been a leading voice for action on this topic, and has developed a compendium of 150+ heat-related federal policy recommendations.

FAS will be represented by Hannah Safford, Associate Director of Climate and Environment, and Grace Wickerson, Health Equity Policy Manager.

“Extreme heat is affecting every corner of our nation, making it more difficult and dangerous for Americans to live, work, and play,” says Wickerson. “Heat-related deaths and illnesses are on the rise, especially among our most vulnerable populations. We must work together to tackle this public health crisis.”

“It’s September, and millions of Americans are still suffering in triple-digit temperatures,” adds Safford. “We applaud the Biden-Harris Administration for drawing attention to the increasing challenges of extreme heat, and for driving on action to build a more heat-resilient nation in 2025 and beyond.”

FAS’s Ongoing Work to Address Extreme Heat

To date FAS has fostered extensive policy innovation related to extreme heat:

- Our Extreme Heat Policy Sprint engaged more than 85 experts and generated heat-related policy recommendations for 34 federal offices and agencies.

- This work is comprehensively summarized in our Whole-of-Government Strategy To Address Extreme Heat, and our associated library of heat policy memos.

- FAS has delivered expert briefings on extreme heat to the White House and federal agencies. Our policy solutions have informed Senate appropriations requests, proposed legislation, and Congressional Research Service reports.

FAS Workshops Will Harness Momentum From White House Summit

Immediately following the White House Heat Summit, FAS will collaborate with the Arizona State University (ASU) Knowledge Exchange for Resilience to host the Celebration for Resilience 2024 Symposium and Gala on September 19th in Tempe.

On Friday, September 20th, FAS will partner with Arizona State University (ASU) to host workshops in Tempe, AZ, Washington DC, and virtually on Defining the 2025 Heat Policy Agenda. This workshop will harness momentum from the White House Summit on Extreme Heat, providing a forum to discuss actions that the next Administration and new Congress should prioritize to tackle extreme heat. For more information and to participate, contact Grace Wickerson (gwickerson@fas.org).

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Preparing and Responding to Extreme Heat through Effective Local, State, and Federal Action Planning

Heat risks are borne out of a combination of contextual factors (e.g., physical geography, planning efforts, political priorities, etc.) and the creation of vulnerability through exposure to the heat hazard (e.g., exposure, sensitivity, adaptive capacity, etc.). These heat-specific, contextual risks provide insight for formulating tailored strategies and technical guidance for devising heat-mitigation interventions that align with regional needs and climatic conditions.

Thus, heat action planning systematically and scientifically organizes short-, medium-, and long-term heat interventions within a spectrum of context-specific, socially, and fiscally responsive options. Integrating existing planning tools and risk assessment frameworks, similar to the broader-scale natural hazard mitigation planning process, offers a timely and effective approach to developing regionally tailored heat action plans.

For heat action planning to succeed nationwide, multiple agencies and offices within the federal government need to 1) support state, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments with timely information and tools that identify specific guidelines, thresholds, objectives, and financial support for advancing interventions for extreme heat adaptation and 2) include extreme heat within their planning processes. Since all state and local public agencies are already involved in a wide variety of planning processes—many of which are requirements to receive federal investments—the focus on heat offers opportunities to integrate several currently disparate efforts into a comprehensive activity aimed at safeguarding the public’s health and infrastructure.

Challenge and Opportunity

Few U.S. municipal governments are actively engaged in a systematic process that prepares local communities for extreme heat. For example, as of 2023, only seven U.S. states had a section dedicated to extreme heat in their Hazard Mitigation Plans (HMPs), as required by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Even when included within HMPs, the medium and long-term planning implications are consistently lacking. Planning for extreme heat’s current and future risk is not a requirement of many federally-mandated planning processes for SLTTs, limiting nationwide uptake.

Despite decades of scientific assessments on risks to human health and infrastructure, there currently needs to be more precedent for developing comprehensive plans that address heat, nor the integration of risks with effective interventions. Many state, local, tribal, and territorial governments (SLTTs) are not planning for extreme heat and its future risk to populations. The appointment of Chief Heat Officers and other regional coordination efforts are currently limited, and the primary mechanism for heat response relies on emergency management. This short-term solution needs to be revised to prepare a region for ongoing and acute temperature increases. SLTTs and the federal government are just starting to invest billions of dollars in material services and non-material interventions, including tree plantings, air conditioning and heat pumps, white paints, cooling centers, new staff roles (i.e., Chief Heat Officers), and communication programs.

Planning for Future Risks of Extreme Heat

Further, as the federal government is just starting to assess its portfolio of assets and programs for heat resilience, it will need to consider future risks of extreme heat beyond immediate health and infrastructure risks to establish a fiscal agenda for risk mitigation. For one, extreme heat events are a catalyst for other destructive disasters, like wildfires and drought. Higher temperatures increase evapotranspiration rates, drying out grasses and trees and turning fallen branches into firewood. Compounding this are the shrinking snowpacks in western states, which make forests more flammable by reducing the water available for vegetation. All of these factors caused by excess heat — along with a history of unsustainable forest management practices and land use decisions — are contributing to more destructive wildfires. From 2017 to 2024, these wildfires came with an estimated $97+ billion in costs.

Additionally, more surface evaporation (1) increases SLTT reliance on limited groundwater sources and (2) leads to less groundwater seepage and aquifer replenishment. Warmer temperatures also mean plants and animals need more water, further driving up consumption of this limited resource. All of these factors compound the growing risk of drought facing American communities. In 2023, over 80% of the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) emergency disaster designations were for drought or excessive heat, and the costliest 2023 disaster was a combined drought/heat wave at $14.5 billion. The interactions and compounding risk of natural hazards are often unaccounted for in HMPs and other plans that consider hazard events in isolation.

Federal Support for Risk Mapping and Planning

Existing federal initiatives to assist SLTTs in planning for extreme heat have focused on documenting extreme heat’s disparate impacts in cities and regions but do not strategically progress heat action planning. For example, the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) is an interagency entity operated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that manages www.heat.gov, and provides several opportunities for SLTTs to socialize and familiarize heat-related interventions. Since 2017, NOAA, in collaboration with NIHHIS, has supported the Heat Watch Campaigns, wherein SLTTs and community groups use temperature sensors to collect hyperlocal heat measurements. These sensors measure and collect temperatures every second, and the resulting maps describe differences in intra-regional heat, known popularly as “urban heat islands” (UHIs), which often vary by upwards of 20°F. These Heat Watch campaigns communicate heat as a local challenge and engage residents in socializing the potential impacts, while also advancing several initiatives and policies that aim to reduce the harmful effects of extreme temperatures. While almost all Heat Watch participating organizations have taken some immediate and often one-off actions, these campaigns have not advanced heat action planning through a systematic process. SLTTs have faced barriers to identifying promising adaptation strategies and resourcing necessary infrastructure improvements without dedicated, reliable follow-on investments. And, because most campaigns are conducted in urban areas, the Heat Watch campaigns currently do not capture the rural and ecosystem effects of heat. More systemic actions that integrate chronological and science-based applications of interventions that include the public, along with scientific assessments and contextual factors, are necessary for SLTTs to adapt.

Moreover, the federal government, which employs +3 million people, procures +$700 billion in goods and services annually, and delivers +$700 billion in financial assistance to states, locals, and private entities, must plan more effectively for extreme heat’s impacts on basic operations, services, infrastructure, and program delivery. As an example, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has completed several assessments on heat (and continues to), and other agencies need to follow suit to ensure infrastructure and programs are resilient to future temperatures. The heat risks posed to basic operations can further strain vulnerable supply chains and put employees who are on the frontline of enabling and operating these Federal programs at risk of illness and death.

Plan of Action

The heat action planning process requires five steps that help identify areas and populations that face disproportionate exposure to regionally-specific hottest temperatures and move towards interventions for mitigating extreme heat for SLTTs and the federal government:

Recommendation 1. Define “extreme heat” risk by local geography.

Extreme heat in Phoenix, AZ differs from extreme heat in Portland, OR; a week of 90°F in the Pacific Northwest can cause as many heat-related illnesses as a 110°F day in the South East. A regional approach to characterizing the relevant risks is an essential first step. Developing heat hazard maps that describe the potential implications of extreme ambient temperatures on the public’s health, infrastructure, and critical services is essential to prepare SLTTs and the federal government. Existing “heat vulnerability indexes and maps” support the articulation of heat hazards, though they remain primarily passive interfaces that do not directly contribute to broader planning or policy processes. In addition, response to hazards requires local understanding and communication of existing risk, which is done by the National Weather Service (NWS) and FEMA through the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System.

To define current and future “extreme heat” risk by local geography:

- FEMA, NOAA, USDA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) can collaborate on assessments of regionally-specific risk in the present and future, codifying cooling assets (potentially through ground-based assessments of summertime air temperatures, atmospheric dynamics, land use and land cover assessments), expected population acclimatization and existing health risks, and assessments of future climate conditions, such as ClimRR. Finally, USDA could assess agricultural growing zones for heat risk and better predict impacts on food and nutrition services supply chains.

- HUD, EPA, and NOAA can work to identify localized exposure to extreme heat by expanding opportunities for monitoring indoor and outdoor air temperature in and around potentially vulnerable land uses (e.g., multifamily residential, older single-family residential, manufactured homes, and trailer parks), seeking additional funding from Congress where needed to develop and place these sensors.

- FEMA can include metrics in its National Risk Index that characterize the building stock (i.e., by adherence to certain building codes), expected thermal comfort levels (even with cooling devices) under current and future climate conditions, and thermal resilience during power brownouts and blackouts. Additional focus on heat inequities will also help to advance approaches that center the public’s long-term health and safety.

Recommendation 2. Establish standards and codes for extreme heat resilience and risk mitigation.

Several federal agencies are directly involved in the development of standards (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Department of Energy (DOE), Department of Transportation (DOT), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), FEMA, Department of Education (Ed)); however, we have no current designation for heat risk, certification of promising solutions, and identification of best practices for heat action planning. Once standards and guidelines exist, funding can accelerate the application of suitable technologies, analysis, and local engagement for developing heat action plans for SLTTs and federal government operations. Further, it is critical that adaptation solutions do not come at the risk of climate mitigation, for example, relying solely on air conditioning to keep people cool, which then leads to increased greenhouse gas emissions. Other strategies like urban forestry, building codes, and reflective materials in suitable locations will also need to be directly applied.

To establish standards and codes for extreme heat resilience and risk mitigation:

- NIST, EPA, and U.S. Forest Service (USFS) can create “technology test beds” for heat resilience best practices, effectiveness evaluation, and associated benefits-costs analysis.

- DOE can work with stakeholders to create “cool” building standards and metrics with human health and safety in mind, and integrate them into building codes like ASHREI 189.1 and 90 series that can then be adopted by SLTTs. Where possible, DOE should explore evaluations of co-benefits of heat resilience with decarbonization and energy efficiency and work with state energy offices to implement these evaluations. Finally, DOE can also consider grid impacts during increasing periods of demand and conduct predictive analyses needed to prevent overload and prepare SLTT energy suppliers.

- FEMA can integrate extreme heat considerations and thermal resilience within its National Strategy to Improve Building Codes.

- HUD can update the Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to require homes to perform a certain level of cooling under high heat conditions.

- HUD and Ed can consider what safe thresholds for occupancy look like for residential settings and schools and provide guidance to SLTTs.

- The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and USFS can consider future risks to nature-based solutions (i.e., extreme heat) within different climate regions as a part of government-wide efforts to scale nature-based solutions.

- DOT can consider requirements for infrastructure projects in SLTTs to mitigate UHI effects.

Recommendation 3. Operationalize interventions and coordinate amongst agencies that require SLTT planning processes.

While knowledge about heat exposure requires further assessment, integrating thresholds and programming to reduce preventable exposure to heat is necessary within planning processes, financial assistance delivery, and program and regulatory implementation. For example, an important next step will be establishing a heat tolerance threshold for occupations with higher heat exposure to ensure workers do not exceed core body temperatures. Currently, several wearable sensor technologies offer a direct means for firms to monitor the health of their outdoor workers. Such information can help develop material and non-material interventions that reduce the likelihood of heat stress and risk and ensure compliance with federal mandates and regulations. As another example, EPA, Health and Human Services (HHS), HUD, FEMA, Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and others can use new standards to implement federal funds or tax incentives.

To better operationalize interventions and coordinate amongst agencies that require SLTT planning processes,

- FEMA can incentivize Hazard Mitigation Planning for SLTTs that accounts for and emphasizes extreme heat risk as well as compounding disaster risk as a part of its National Mitigation Planning Program.

- The Executive Office of the President (EOP) can consider its role in coordinating nationwide climate-risk planning, through auditing plans required by CDC, Administration for Strategic Planning and Response (ASPR), Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), Department of Transportation (DOT), FEMA, and other agencies for their readiness for future climate conditions (i.e. extreme heat). Where heat risk is not currently required in a federally-mandated plan, federal agencies should consider incentives to drive the adoption and uptake of heat action planning by SLTTs.

- OMB can identify potential regulatory pathways to build extreme heat resilience within SLTTs and federal government operations, considering technology standards, behavioral guidelines and expectations, and performance standards.

- Technology standards: Required presence of a cooling and/or thermal-regulating technology

- Behavioral guidelines and expectations: Required actions to avert overexposure

- Performance standards: Requirements that heat exposure cannot cross a certain threshold.

Recommendation 4. Support fiscal planning and funding prioritization.

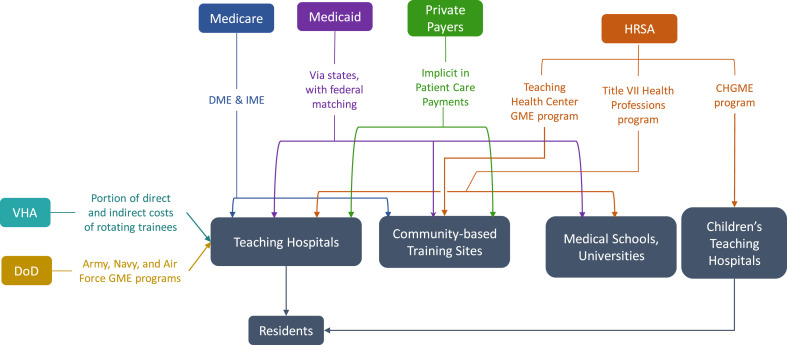

Local jurisdictions must plan for many hazards and risks, and because heat funding is scarce and hard to get, it falls to the bottom of the list of priorities. Establishing a clear and accessible set of resources to understand the resources available to support heat adaptation and resilience can help to advance effective solutions. Further, SLTTs will get more funding to prevent past hazards, versus prepare for future ones like extreme heat. Current funding through FEMA and DOE is helping to shore up heat risk assessments and interventions in select locations, yet they remain inadequate for the scale of the challenge facing SLTTs. By prioritizing future climate risk in fiscal planning and funding, extreme heat resilience will become a larger priority because it can integrate into several programmatic and policy priorities, such as transportation, housing, and emergency response. The insurance and healthcare industries, operated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and Veterans Health Administration (VHA) can also play a larger role in shepherding heat resilience forward, by advancing beneficiaries that are adapting to extreme heat, and reducing emergency room visits due to heat illness.

To support fiscal planning and funding prioritization,

- OMB can work with federal agencies to perform a budget review of actual allocations to extreme heat activities, including financial assistance to SLTTs, as well as extreme heat’s existing risks to federal assets, critical infrastructure, programs, and workforce. OMB can collaborate with the General Services Administration (GSA) on federal workforce and contractor workforce safety protections and VHA, Department of Justice (DOJ), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), DOT, Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), DOE, and other relevant agencies on operations of critical infrastructure during current and future heat events.

- OMB, in collaboration with EPA, FEMA, DOE, and NIST, can produce a report that identifies gaps in funding to advance heat mitigation and preparedness efforts.

- HUD, FEMA, EPA, and others can recommend recipients of federal financial assistance adhere to building and energy codes that ensure thermal comfort and resilience.

- Treasury can investigate potential insurance options for covering the losses from extreme heat, including security from utility cost spikes, real-estate assessment and scoring for future heat risk, “worker wage” coverage for days where it is unsafe to work, protections for household resources lost during an extended blackout or power outage, and coverage for healthcare expenses caused by or exacerbated by heat waves that CMS could incentivize.

- The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) can price climate risk when deciding on interest payments for municipal bonds for SLTTs and give beneficial rates to SLTTs that have done a full analysis of their risks and made steps towards resilience.

Recommendation 5. Build evaluative capacity of extreme heat resilience interventions.

There is a need for designated bodies that evaluate and monitor the effectiveness of specific heat mitigation interventions to make systematic improvements. Universities, research non-profits, and many private organizations have deep expertise in evaluating and assessing heat-relevant programs and projects. Such programs will need to be developed through universities and through private-public partnerships that support SLTTs in ensuring that specific actions are effective and transferable.

To build out the evaluative capacity of extreme heat resilience interventions,

- GSA can demonstrate low-power, passive and resilient cooling strategies in its buildings as a part of “Net Zero” initiatives and document promising strategies by climate region. DOE can also conduct more demonstration projects to build strategies that ensure indoor survivability in everyday and extreme conditions.

- EPA and NOAA can administer research and evaluation grants to assess, identify, and promote heat mitigation actions that are effective in reducing heat risks across diverse geographies as well as design effective heat action planning strategies for SLTTs. This could look like further expansion and institutionalization of the NIHHIS Centers of Excellence program.

Conclusion

In all scientific estimates, 2024 will be the next hottest year on human record, and each year thereafter is likely to be even hotter. Under even existing climate conditions, thousands of Americans are already unnecessarily dying every year, and critical infrastructures like grids are being pushed to their limits. With temperature trends point to ever-hotter summers, effective and strategic heat adaptation planning within SLTTs and across the federal government is a national security priority. Through the broad uptake and implementation of the Heat Action Planning framework by key agencies and offices (EOP, OMB, Treasury, SEC, NOAA, USDA, CDC, NASA, HUD, DHS, FEMA, NIST, EPA, USFS, DOE, DOJ, DOT, ASPR, GSA, USACE, VHA, SEC, and others), the federal government will enable a more heat-prepared nation.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

Potential examples of federal heat risk mitigation include:

- General Services Administration (GSA) protecting the federal workforce and federal contractors from extreme heat conditions;

- Department of Energy (DOE) and Department of Education (Ed) ensuring heat resilient school and education infrastructure so that children, teachers, and staff are able to engage in continuous learning during the hottest periods of the year;

- Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and Department of Justice (DOJ) guaranteeing veterans and incarcerated people in their care (or in the care of dependent organizations) are not dying of heat illness;

- USDA assessing potential risk to its food, nutrition, and forestry services due to heat-exacerbated supply chain shortages;

- Department of Transportation (DOT), Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and DOE ensuring critical infrastructure (roads, railways, power grids, data centers, utilities, etc) are designed and ready for increasingly extreme temperatures.

U.S. Water Policy for a Warming Planet

In 2000, Fortune magazine observed, “Water promises to be to the 21st century what oil was to the 20th century: the precious commodity that determines the wealth of nations.” Like petroleum, freshwater resources vary across the globe. Unlike petroleum, no living creature survives long without it. Recent global episodes of extreme heat intensify water shortages caused by extended drought and overpumping. Creating actionable solutions to the challenges of a warming planet requires cooperation across all water consumers.

The Biden-Harris administration should work with stakeholders to (1) develop a comprehensive U.S. water policy to preserve equitable access to clean water in the face of a changing climate, extreme heat, and aridification; (2) identify and invest in agricultural improvements to address extreme heat-related challenges via U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and Farm Bill funding; and (3) invest in water replenishment infrastructure and activities to maintain critical surface and subsurface reservoirs. America’s legacy water rules, developed under completely different demographic and environmental conditions than today, no longer meet the nation’s current and emerging needs. A well-conceived holistic policy will optimize water supply for agriculture, tribes, cities, recreation, and ecosystem health even as the planet warms.

Challenge and Opportunity

In 2023, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recorded the hottest global average temperature since records began 173 years prior. In the same year, the U.S. experienced a record 28 billion-dollar disasters. The earth system responds to increasing heat in a variety of ways, most of them involving swings in weather and water cycles. Warming air holds more moisture, increasing the possibility of severe storm events. Extreme heat also depletes soil moisture and increases evapotranspiration. Finally, warmer average temperatures across the U.S. induce northward shifts in plant hardiness zones, reshaping state economies in the process.

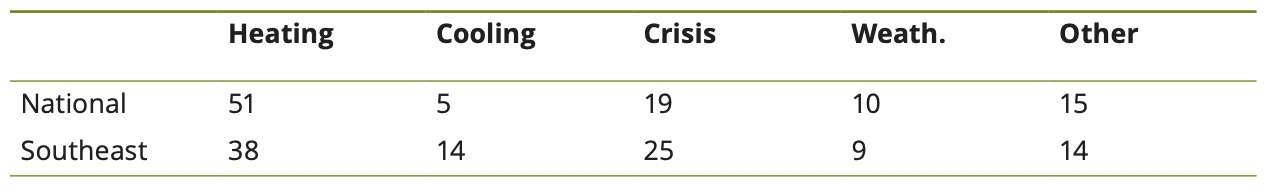

As a result, agriculture currently experiences billions of dollars in losses each year (Fig. 1). Drought, made worse by high heat conditions, accounts for a significant amount of the losses. In 2023, 80% of emergency disaster designations declared by USDA were for drought or excessive heat.

Agriculture consumes up to 80% of the freshwater used annually. Farmers rely on surface water and groundwater during dry conditions, as climate change systematically strains water resources. Rising heat can increase overall demand for water for irrigating crops, exacerbating water shortages. Plants need more water; evapotranspiration rates increase to keep internal temperatures in check. Warming is also shrinking the snowpack that feeds rivers, driving a “snow loss cliff” that will impact future supply. Compounding all of this, Americans have overused depleted reservoirs across the country, leading to a system in crisis.

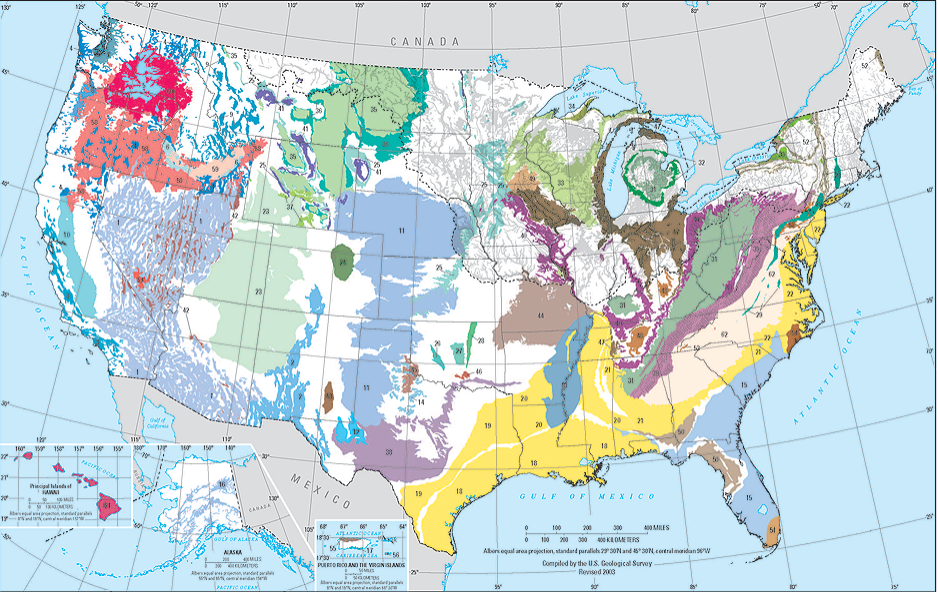

America’s freshwater resources fall under a tangle of state, local, and watershed agreements cobbled together over the past 100 years. In general, rules fall into two main categories: riparian rights and prior appropriation. In the water-replete eastern U.S., states favor riparian rights. Under this doctrine, property owners generally maintain local use of the water running through the property or in the aquifer below it, except in the case of malicious overuse. Most riparian states currently fall under the Absolute Dominion (or the English) Rule, the Correlative Rights Doctrine, or the Reasonable Use Rule, and many use term-limited permitting to regulate water rights (Table 1). In the arid western region, states prefer the Doctrine of Prior Appropriation. Under this scheme, termed “first in time, first in right,” property owners with older claims have priority over all newer claimants. Unlike riparian rights, prior appropriation claims may be separated from the land and sold or leased elsewhere. Part of the rationale for this is that prior appropriation claims refer to shares of water that must be transported to the land via canals or pipes, rather than water that exists natively on the property, as found in the riparian case. Some states use a mix of the two approaches, and some maintain separate groundwater and surface water rules (Fig. 2).

Original “use it or lose it” rules required claimants to take their entire water allotment as a hedge against speculation by absentee owners. While persistent drought and overuse reduced water availability over time, “use it or lose it” rules continue to penalize reduction in usage rates, making efficiency counterproductive. For example, Colorado’s “use it or lose it”’ rule remains on the books, despite repeated efforts to revise it. In a sign of progress, in 2021, Arizona passed a bipartisan law to change their “use it or lose it” rule to guarantee continued water rights if users choose to conserve water.

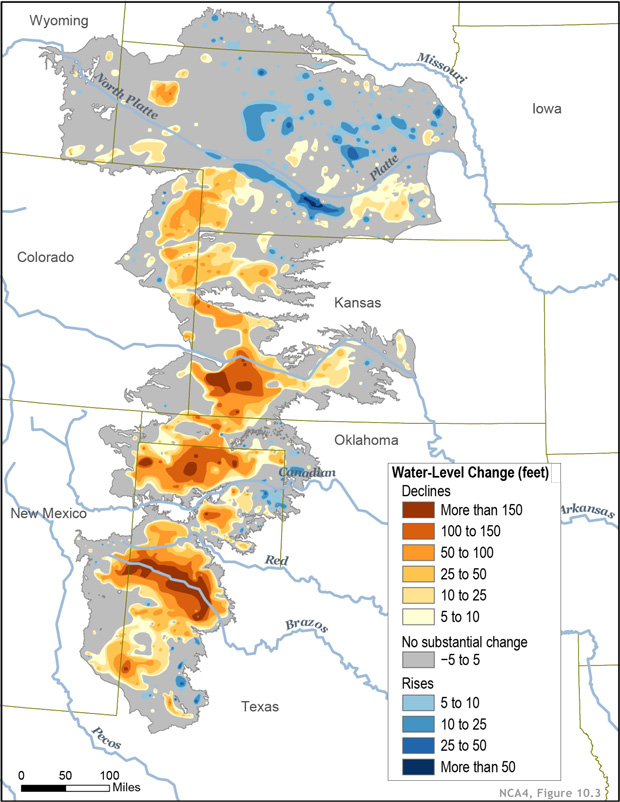

Water scarcity extends well beyond the arid western states. In the Midwest, higher temperatures and drought exacerbate overpumping that continues to deplete the vast Ogallala Reservoir that underlies the Great Plains (Fig. 3). Driven in part by rising temperatures, the effective 100th meridian that separates the arid West from the humid East appears to have shifted east by about 140 miles since 1980, indicating creeping aridification across the Midwest. The drought-impacted Mississippi River level dropped for the past two consecutive years, impeding river transport and causing saltwater intrusion into Louisiana groundwater, contaminating formerly potable water in many wells.

via Climate.gov

Recognition of water’s increased importance, especially in a future of more extreme heat and its cascading impacts, drives new markets for the trade of physical water. The impetus for some markets arises from the variance in water availability and cost between different industries and communities. Ideally, benefits accrue to both sellers and buyers by offering a valuable revenue stream for meeting a resource need. Markets differ between groundwater and surface water. For groundwater markets, agreements allow one user to trade some portion of allocated pumping rights to another local user, although impacts to neighbors and ecosystems that share the aquifer must be considered. Successful groundwater trades rely on accurate assessments of subsurface water levels over time. For surface water trades, a portion of the prior appropriation water can be sold or leased to another user regardless of proximity, or banked for future use. Legislation passed in 2022 enables Colorado River Indian Tribes to lease or trade newly settled water rights, or to bank them for future use in surface or subsurface reservoirs without facing a “use it or lose it” penalty.

There are less obvious water considerations. Import from and export to foreign nations of heavily irrigated crops or water-intensive commodities equates to virtual water trade. The most common virtual water export involves foreign sale of American farmer-grown crops. Other means include sales or leases of domestic land to foreign entities that grow water-intensive crops on U.S. soil, often on arid land, for export. Virtual water trades occur within the U.S. as well, through exchange of goods and services.

Developing a framework for cooperation across end users, complementary to previous frameworks recommended for the Ogallala Aquifer, creates a mechanism to address urgent water issues. Establishing the federal government’s role to convene and collaborate with stakeholders helps all parties participate within a common structure toward solving a mutual problem. To promote sustained productivity and water resources in the face of extreme heat and aridification, a holistic federal water policy should focus on:

- Simplifying and streamlining water rights

- Creating a framework for water trades

- Increasing water use efficiency

- Developing data-driven predictive tools

- Initiating and supporting new agricultural approaches

- Developing strategic water recharge

The Biden-Harris administration should develop a plan that creates incentives for all stakeholders to participate in water management policy development in the face of rising heat and climate change. Specifically, discussions must consider real reservoir volumes (surface and subsurface), current and future temperatures, annual rain and snow measurements, evapotranspiration calculations, and estimates of current and future water needs and trades across all end users. History supports federal assistance in thorny resource management areas. One close analog, that of fisheries management, shows the power of compromise to conserve future resources despite fierce competition.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. The White House Council on Environmental Quality should convene a working group of experts from across federal and state agencies to develop a National Water Policy to future-proof water resources for a hotter nation.

Progress toward increased scientific understanding of the large-scale hydrologic cycle offers new opportunities for managing resources in the face of change. Management efforts started at local scales and expanded to regional scales. Country-wide management requires a more holistic view. The U.S. water budget is moving to a more unstable regime. Climate change and extreme heat add complexity by shifting weather and water cycles in real-time. Improving the system balance requires convening stakeholders and experts to formulate a high-level policy framework that:

- Creates mechanisms for cooperation across all stakeholders

- Coordinates with stakeholders to restructure water rights at the basin scale, including high-demand industries like agriculture

- Accounts for changes in total, and basin- and aquifer-scale, water volumes at the necessary spatial and temporal resolution as a basis for decision-making, including estimations of future water capacity

- Develops a mechanism to assess and manage, when necessary, physical and virtual water trades, considering climate risk to supply and demand

- Identifies opportunities for investment based on observations and best-in-class models

- Includes a framework for adaptive policy modification as climate changes, heat’s impacts are better understood, and new water trends occur

- Monitors and evaluates emerging markets to “buy” water to “bank” it for sale at a higher price during drought years and/or high heat events

- Identifies one lead government agency to coordinate water policy, nominally the Department of the Interior (DOI)

- Coordinates with Congress to identify a lead committee in each chamber to oversee water policy

As such, the White House Council on Environmental Quality should convene a working group of experts from across federal and state agencies to create a comprehensive National Water Policy. Relevant government agencies include the DOI; the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS); the Bureau of Indian Affairs; the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE); Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); Department of Commerce; NOAA; and the USDA. The envisioned National Water Policy complements the U.S. Government Global Water Strategy.

via USGS

Data products to support the creation of a robust National Water Policy already exist (Fig. 4). USGS, FEMA, the National Weather Service, USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, and NOAA’s National Climate Data Center, Office of Water Prediction, and National Water Center all contribute data critical to development of both high-level and regional-scale assessments and data layers crucial for short- and mid-term planning. Creating term reassessments as more data accrue and models improve supports effective decision-making as climate change and extreme heat continue to alter the hydrologic cycle. An overall water policy must remain dynamic due to changing trends and new data.

National, regional, and local aspects of the water budget and related models and visualizations help federal and state decision makers develop a strategic plan for modernizing water rights for both river water, basins, and groundwater and to identify risks to supplies (e.g., decreasing snowpack due to higher heat) and opportunities for recharge. Stakeholders and water managers with shared knowledge of well-documented data are best positioned to determine minimum reservoir volumes in the primary storage basins, including aquifers, in alignment with the objectives of the National Strategy to Develop Statistics for Environmental and Economic Decisions. By creating a strategy that uses actual average values to maintain reservoir volumes, some of the potential shocks created by drought years and high heat could be cushioned, and related financial losses could be avoided or mitigated. Ultimately, stakeholders and managers must share a common understanding of the water budget when seeking to resolve water rights disputes, to review and revise water rights, and to inform trades.

Basin and local data promote development of a strategic framework for water trades. As trades and markets continue to grow, states and municipalities must account for water rights, both the lease and sale of rights, to buffer large fluctuations in water prices and availability. Emerging markets to “buy” water to “bank” it for sale at a higher price during drought years and/or high heat events should also be monitored and evaluated by relevant agencies like Commerce. States’ and investors’ maintenance of transparency around market activities, including investor purchases of land with water rights, promotes fair trade and ensures stakeholder confidence in the process.

Finally, to communicate clearly with the public, funds should be provided through the DOI budget to NOAA and USGS data scientists to create decision-support tools that build on the work already underway through mature databases (e.g., at drought.gov and water.weather.gov). New water visualization tools to show the nowcast and forecast of the national water status would help the public understand policy decisions, akin to depictions used by weather forecasters. Variables should include heat index, humidity, expected evapotranspiration, precipitation, surface volumes, and groundwater levels, along with information on water use restrictions and recharge mechanisms at the local level. Making this product media-friendly aids public education and bolsters policy adoption and acceptance.

Recommendation 2. USDA should invest in infrastructure, research, and development.

Agriculture, as the largest water consumer, faces scarcity in the coming years even as populations continue to grow. Increasing demands on a dwindling resource and growing need for more water lead to conflict and acrimony. To ease tensions and maintain the goods and services needed to fuel the U.S. economy in the future, investment in both immediately practicable future-proofed, heat-resilient water solutions and over-the-horizon research and development must commence. To prepare, USDA will need to:

- Continue to fund the installation of liners or pipes for irrigation and conveyance canals, in alignment with efforts under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL). Farmers historically irrigated their fields by flooding them via outdated earthen canals. Extensive evaporation and ground seepage losses delay water delivery to fields and creates unintended ecological side effects.

- Promote the installation of water-efficient irrigation methods on farms that previously used field flooding or other inefficient practices. Policy may include co-funding improvements, buying back “conserved water” and offering low-interest loans. The combination of improved canals with efficient irrigation technologies maintains agricultural production while reducing water loss.

- Test the efficacy of installing solar panels over or adjacent to open lined aqueducts or conveyance canals to both produce energy by taking advantage of evaporative cooling of the panel undersides and reduce some heat-driven evaporation of water from the canal by blocking sunlight. The dual benefit especially increases in the face of extreme heat where panels ordinarily become much less efficient as temperatures rise. An additional advantage includes running electrical infrastructure out to farms where farmers could use energy or connect their own panels if they wished to sell energy back to the grid.

- Add agrivoltaics (or other emerging energy/agricultural land use options) to the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program (ACEP). Research indicates that co-benefits include locally increased moisture for plants protected by panels while evapotranspiration cools the panels. This adaptation creates a reliable source of local energy while keeping agricultural land productive.

- Support transition to USDA-recommended varieties of climate-resilient Western native grasses for forage and soil stabilization of marginal land. Converting some highly irrigated farmland to desert livestock forage maintains agricultural land while reducing water usage, in line with the goals of the ACEP program.

- Support market development for desert agricultural crops adapted to the native conditions under the new Regional Agricultural Promotion Program (RAPP). Include food science and animal feed research to increase adoption. Examples include cactus opuntia fruit for natural sweetening, cactus paddles for food and fodder, drought-tolerant grasses and grains, mesquite grass forage, and mesquite bush seed pod flour. These developments build on careful research and accounts of Indigenous people and early settler practices and diets.

- Support development and deployment of technology that remotely detects water-stressed, heat-stressed plants to enable smart irrigation and cooling under USDA’s Agriculture and Food Research Initiative (AFRI).

- Develop crops with greater resilience to extreme heat, intermittent flooding, and intermittent drought via funding through Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority (AgARDA) and AFRI. Examples include genetically modifying or hybridizing plants for:

- greater heat-tolerance and resilience to heat-stress,

- adaptation to inundation-related oxygen deficiency, and

- resilience to increased heat driving evapotranspiration during droughts.

To support these efforts and broader climate resilience needs of farmers, Congress can:

- Reauthorize and fully fund the AgARDA at the requested $50 million annual budget to begin its mission. AgARDA was originally established under the 2018 Farm Bill (Section 7132 of the Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018(Public Law 115-334)). The agency received $1 million in each of the years 2022 and 2023, for a total of 0.8% of the total amount authorized. Addressing the challenges facing this century’s agriculture requires high-risk, high-reward thinking. No mechanism within the USDA sponsors such programs. Historically, the $250 million total recommended budget represented less than 0.06% of the total value ($428 billion) of the 2018 Farm Bill over its five-year span.

Recommendation 3. Federal, state, and local governments must invest in replenishing water reserves.

To balance water shortage, federal, state and local governments must invest in recharging aquifers and reservoirs while also reducing losses due to flooding. Opportunities for flood basin recharge arise during wet years, especially accounting for the shift from longer, frequent, lighter rainstorms to shorter, less frequent durations of very heavy rainfall. Federal agencies currently have opportunities to leverage Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and BIL money for replenishment, including the following:

- FEMA, DOI and USDA can encourage grantees to use, and USACE can implement, proven nature-based, physical barriers to slow down surface flow in the event of heavy precipitation and flooding. Restoring river oxbows with associated wetlands, creating tree falls and wetland horizontal levees, reintroducing beavers, and employing other nature-based solutions can improve recharge and reduce downstream flood damage by slowing release of water. These measures should be instigated with a view to improving the hydrologic cycle of streams in the drainage basin, especially those that have been heavily engineered in the past. Co-benefits of these greening interventions include reducing surface temperature, thereby benefiting humans, livestock, and crops.

Congress can further support these actions by:

- Implementing annual-enrollment, permanent floodplain easements in the 2023 US Farm Bill. As outlined in the American Rivers report, the Emergency Watershed Protection (EWP) program “received 2,210 applications, but less than 10 percent of total applications and 16 percent of flood prone acres have been enrolled.” At present, the EWP program solely provides funds following a disaster rather than as a long-term strategic investment. Adopting floodplain easements as policy would maintain soil fertility, offer flood protection for downstream properties, and help to recharge aquifers for subsequent use and safeguard against future extreme heat and drought.

- Creating mechanisms whereby farmers who flood their fields during wet years accrue credits toward water allocations in dry years. Where appropriate, farms should be funded to develop appropriately located swales and catchments to collect rainwater and irrigation runoff.

- Funding expansion of the USACE Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) program authorized under the 2016 Water Resources Development Act. Projects have commenced in 17 states so far. In this approach, USACE pumps surface water into aquifers for:

- Drought resilience

- Flood mitigation

- Aquatic ecosystem restoration and constructed wetlands

- Reducing saltwater intrusion

- Multi-use urban environmental restoration projects

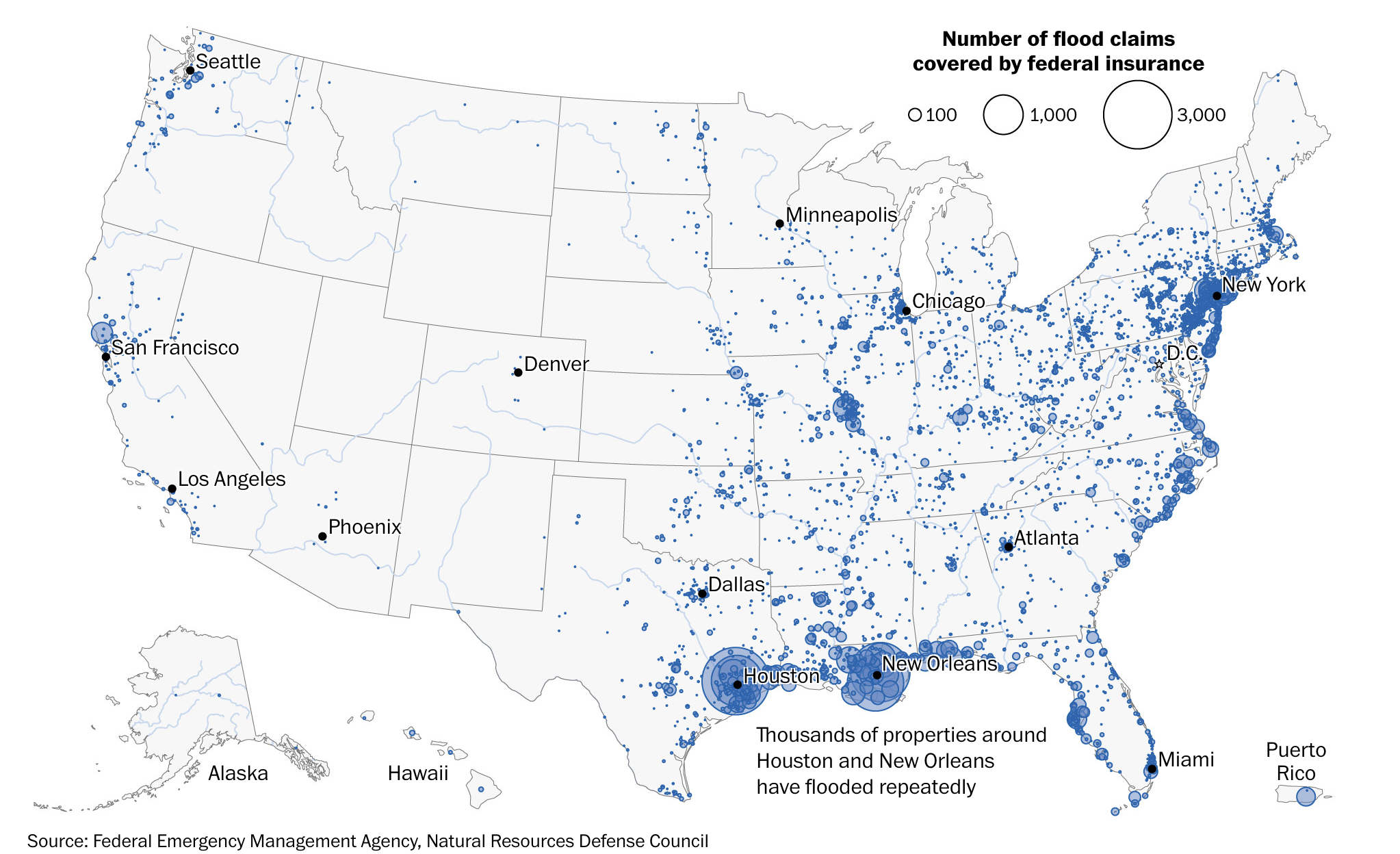

- Funding the purchase of properties repeatedly affected by flooding to convert them into natural flood buffer areas and to support aquifer recharge zones in line with FEMA’s Public Assistance Program. Expanding this program beyond disaster response would remove vulnerable structures proactively, based on historic flood records and documented flood risk (Fig. 5). The purchase approach is distinct from the easement program that allows farmers to retain ownership of the property.

via Washington Post, with credit to Federal Emergency Management Agency, Natural Resources Defense Council

Conclusion

Water policy varies regionally, by basin, and by state. Because aquifers cross regions and water supplies vary over interstate and international boundaries, the federal government is the best arbiter for managing a dynamic, precious resource. By treating the hydrologic cycle as a dynamic system, data-driven water policy benefits all stakeholders and serves as a basis for future federal investment.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

DOI already manages surface waters in some basins through the Bureau of Reclamation and through the decision in Arizona vs. California. DOI also coordinates water infrastructure investments across multiple states via BIL funding. Furthermore, DOI agencies actively engage in collecting and sharing water resource data across the U.S. Because DOI maintains a holistic view of the hydrologic cycle and currently engages with stakeholders across the country on water concerns, it is best positioned to lead the discussions.

DOI, through the USGS, mapped out most of the largest U.S. aquifers (Fig. 4) and drainage basins. The main stakeholders for each reservoir emerge through those maps.

The best way to maintain agricultural production is to invest in increasingly efficient water farming practices and infrastructure. For example, installing canal liners, pipes, and smart watering equipment reduces water loss during conveyance and application. Funds have been allocated under the BIL and IRA for water infrastructure upgrades. Some government and state agencies offer grants in support of increased water efficiency. Working with seed companies to select drought- and/or flood-tolerant variants offers another approach. Farmers should also encourage funding agencies to ramp up groundwater replenishment activities and to accelerate development of new supporting technologies that will help maintain production.

Funds or tax credits are available to help defray some of the costs of installing renewable energy on rural land. Various agencies also offer targeted funding opportunities to test agrivoltaics; these opportunities tend to entail collaboration with university partners.

Over a century ago, the prior appropriation doctrine attracted homesteaders to the arid Colorado River basin by offering set water entitlements. Several early miscalculations contributed to the basin’s current water crisis. First, the average annual flow of the Colorado River used to calculate entitlements was overestimated. Second, entitlements grew to exceed the overestimated annual flow, compounding the deficit. Third, water entitlement plans failed to set aside specific shares for federally recognized tribes as well as the vast populations that responded to the call to move west. Finally, “use it or lose it” rules that govern prior appropriation entitlements created roadblocks to progress in water use efficiency.

A water futures market already exists in California.

Program leaders would need to work cooperatively with impacted families to find agreeable home sites away from flood zones, especially in close-knit communities where residents have established ties with neighbors and businesses. If desired and when practicable, existing homes could be transported to drier ground. Working with all of the stakeholders in the community to chart a path forward remains the best and most equitable policy.

Defining Disaster: Incorporating Heat Waves and Smoke Waves into Disaster Policy

Extreme heat – and similar people-centered disasters like heavy wildfire smoke – kills thousands of Americans annually, more than any other weather disaster. However, U.S. disaster policy is more equipped for events that damage infrastructure than those that mainly cause deaths. Policy actions can save lives and money by better integrating people-centered disasters.

Challenge and Opportunity

At the federal level, emergency management is coordinated through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), with many other agencies as partners, including Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Small Business Administration (SBA). Central to the FEMA process is the requirement under the Stafford Act that the President declare a major disaster, which has never happened for extreme heat. This seems to be caused by a lack of tools to determine when a heat wave event escalates into a heat wave disaster, as well as a lack of a clear vision of federal responsibilities around a heat wave disaster.

Gap 1. When is a heat event a heat disaster?

A core tenet of emergency management is that events escalate into disasters when the impacts exceed available resources. Impact measurement is increasingly quantitative across FEMA programs, including quantitative metrics used in awarding Fire Management Assistance Grant (FMAG), Public Assistance (PA), and Individual Assistance (IA) and in the Benefit Cost Analysis (BCA) for hazard mitigation grants.

However, existing calculations are unable to incorporate the health impacts that are a main impact of heat waves. When health impacts are included in a calculation, it is only in limited cases; for example, the BCA allows mental healthcare savings, but only for residential mitigation projects that reduce post-disaster displacement.

Gap 2. What is the federal government’s role in a heat disaster?

Separate from the declaration of a major disaster is the federal government’s role during that disaster. Existing programs within FEMA and its partner agencies are designed for historic disasters rather than those of the modern and future eras. For example, the National Risk Index (NRI), used to understand the national distribution of risks and vulnerability, bases its risk assessment on events between 1996 and 2019. As part of considering future disasters, disaster policy should consider intensified extreme events and compound hazards (e.g., wildfire during a heat wave) that are more likely in the future.

A key part of including extreme heat and other people-centered disasters will be to shift toward future-oriented resilience and adaptation. FEMA has already been making this shift, including a reorganization to highlight resilience. The below plan of action will further help FEMA with its mission to help people before, during, and after disasters.

Plan of Action

To address these gaps and better incorporate extreme heat and people-centered disasters into U.S. emergency management, Congress and federal agencies should take several interrelated actions.

Recommendation 1. Defining disaster

To clarify that extreme heat and other people-centered disasters can be disasters, Congress should:

(1) Add heat, wildfire smoke, and compound events (e.g., wildfire during a heat wave) to the list of disasters in Section 102(2) of the Stafford Act. Though the list is intended to be illustrative rather than exhaustive, as demonstrated by the declaration of COVID-19 as a disaster despite not being on the list, explicit inclusion of these other disasters on the list clarifies that intent. This action is widely supported and example legislation includes the Extreme Heat Emergency Act of 2023.

(2) FEMA should standardize procedures for determining when disparate events are actually a single compound event. For example, many individual tornadoes in Kentucky in 2021 were determined to be the results of a single weather pattern, so the event was declared as a disaster, but wildfires that started due to a single heat dome in 2022 were determined to be individual events and therefore unable to receive a disaster declaration. Compound hazards are expected to be more common in the future, so it is critical to work toward standardized definitions.

(3) Add a new definition of “damage” to Section 102 of the Stafford Act that includes human impacts such as death, illness, economic impacts, and loss of critical function (i.e., delivery of healthcare, school operations, etc.). Including this definition in the statute facilitates the inclusion of these categories of impact.

To quantify the impacts of heat waves, thereby facilitating disaster decisions, FEMA should adopt strategies already used by the federal government. In particular, FEMA should:

(4) Work with HHS to expand the capabilities of the National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP) to evaluate in real time various societal impacts like the medical-care usage and work or school days lost. Recent studies indicate that lost work productivity is a major impact of extreme heat that is currently unaccounted—a gap of potentially billions of dollars. The NSSP Community of Practice can help expand tools across multiple jurisdictions too. Expanding syndromic surveillance expands our ability to measure the impacts of heat, building on the tools available through the CDC Heat and Health Tracker.

(5) Work with CDC to expand their use of excess-death and flu-burden methods, which can provide official estimates of the health impacts of extreme heat. These methods are already in use for heat, but should be regularly applied at the federal level, and would complement the data available from health records via NSSP because it calculates missing data.

(6) Work with EPA to expand BenMAP software to include official estimates of health impacts attributable to extreme heat. The current software provides official estimates of health impacts attributable to air pollution and is used widely in policy. Research is needed to develop health-impact functions for extreme heat, which could be solicited in a research call such as through NIH’s Climate and Health initiative, conducted by CDC epidemiologists, added to the Learning Agenda for FEMA or a partner agency, or tasked to a national lab. Additional software development is also needed to cover real-time and forecast impacts in addition to the historic impacts it currently covers. The proposed tool complements Recommendations #4-5 because it includes forecast data.

(7) Quantify heat illness and death impacts. Real-time data is available in the CDC Heat and Health Tracker. These impacts can be converted to dollars for comparison to property damage using the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL), which FEMA already does in the NRI ($11.6 million per death and $1.16 million per injury in 2022). VSL should be expanded across FEMA programs, in particular the decision for major disaster declarations. VSL could be immediately applied to current data from NSSP, to expanded NSSP and excess-death data (Recommendations #4-5), and is already incorporated into BenMAP so would be available in the expanded BenMAP (Recommendation #6).

(8) Quantify the impact of extreme heat on critical infrastructure, including agriculture. Improved quantification methods could be achieved by expanding the valuation methods for infrastructure damage already in the NRI and could be integrated with the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS). The damage and degradation of infrastructure is often underestimated and should be accurately quantified. For example,

- (a) The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) has reported on extreme heat and documented heat impacts on asset management, where the Department of Transportation (DOT) in multiple states, including Arizona’s DOT, and the National Cooperative Highway Research Program have developed evaluation methods for quantifying impacts, and

- (b) Impacts to critical infrastructure have been quantified across sectors and should include representative agencies such as transportation (e.g., FHWA, DOT), transit (e.g., Federal Transit Authority (FTA)), energy (e.g., Department of Energy (DOE), EPA, water/sanitation (e.g., U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), Bureau of Reclamation (BOR)), telecommunications (e.g., Department of Homeland Security, Federal Communications Commission), social (e.g., HUD, HHS, Department of Education (ED)), and environmental infrastructures (e.g., EPA, USACE, National Parks Service (NPS)).

Together, these proposed data tools would provide FEMA with a comprehensive understanding of the impacts of extreme heat on human health in the past, present, and near future, putting heat on the same playing field as other disasters.

Real-time impacts are particularly important for FEMA to investigate requests for a major disaster declaration. Forecast impacts are important for the ability to preposition resources, as currently done for hurricanes. The goal for forecasting should be 72 hours. To achieve this goal from current models (e.g., air quality forecasts are generally just one day in advance):

(9) Congress should fund additional sensors for extreme weather disasters, to be installed by the appropriate agencies. More detailed ideas can be found in other FAS memos for extreme heat and wildfire smoke and in recommendation 44 of the recent Wildland Fire Commission report.

(10) Congress should invest in research on integrated wildfire-meteorological models through research centers of excellence funded by national agencies or national labs. Federal agencies can also post specific questions as part of their learning agendas. Models should specifically record the contribution of wildfire smoke from each landscape parcel to overall air pollution in order to document the contribution of impacts. This recommendation aligns with the Fire Environment Center proposed in the Wildland Fire Commission report.

Recommendation 2. Determining federal response to heat disasters

To incorporate extreme heat and people-centered disasters across emergency management, FEMA and its peer agencies can expand existing programs into new versions that incorporate such disasters. We split these programs here by the phase of emergency management.

Preparedness

(11) Using Flood Maps as a model, FEMA should create maps for extreme heat and other people-centered disasters. Like flood maps, these new maps should highlight the infrastructure at risk of failure or the loss of access to critical infrastructure (e.g., FEMA Community Lifelines) during a disaster. Failure here is defined as the inability of infrastructure to provide its critical function(s); infrastructure that ceases to be usable for its purpose when an extreme weather event occurs (i.e., bitumen softening on airport tarmacs, train line buckling, or schools canceled because classrooms were too hot or too smokey). This includes impacts to evacuation routes and critical infrastructure that would severely impact the functioning of society. Creating such a map requires a major interagency effort integrating detailed information on buildings, heat forecasts, energy grid capacity, and local heat island maps, which likely requires major interagency collaboration. NIHHIS has most of the interagency collaborators needed for such effort, but should also include the Department of Education. Such an effort likely will need direct funding from Congress in order to have the level of effort needed.

(12) FEMA and its partners should publish catastrophic location-specific scenarios to align preparedness planning. Examples include the ARkStorm for atmospheric rivers, HayWired for earthquake, and Cascadia Rising for tsunami. Such scenarios are useful because they help raise public awareness and increase and align practitioner preparedness. A key part of a heat scenario should be infrastructure failure and its cascading impacts; for example, grid failure and the resulting impact on healthcare is expected to have devastating effects.

(13) FEMA should incorporate future projections of disasters into the NRI. The NRI currently only uses historic data on losses (typically 1996 to 2019). An example framework is the $100 million Prepare California program, which combined historic and projected risks in allocating preparedness funds. An example of the type of data needed for extreme heat includes the changes in extreme events that are part of the New York State Climate Impacts Assessment.

(14) FEMA should expand its Community Lifelines to incorporate extreme heat and cascading impacts for critical infrastructure as a result of extreme heat, which must remain operable during and after a disaster to avoid significant loss of human life and property.

(15) The strategic national stockpile (SNS) should be expanded to focus on tools that are most useful in extreme weather disasters. A key consideration will be fluids, including intravenous (IV) fluids, which the current medical-focused SNS excludes due to weight. In fact, the SNS relies on the presence of IV fluids at the impacted location, so if there is a shortage due to extreme heat, additional medicines might not be deliverable. To include fluids, a new model will be necessary because of the logistics of great weight.

(16) OSHA should develop occupational safety guidelines to protect workers and students from hazardous exposures, expanding on its outdoor and indoor heat-related hazards directive. Establishing these thresholds, such as max indoor air temperatures similar to California’s Occupational Safety and Health Standards Board, can help define the threshold of when a weather event escalates into a disaster. No federal regulations exist for air quality, so California’s example could be used as a template. The need already exists: an average of 2,700 heat-related injuries and 38 heat-related fatalities were reported annually to OSHA between 2011 and 2019.

(17) FEMA and its partners should expand support for community-led multi-hazard resilience hubs, including learning from those focused on extreme heat. FEMA already has its Hubs for Equitable Resilience and Engagement, and EPA has major funding available to support resilience hubs. This equitable model of disaster resilience that centers on the needs of the specific community should be supported.

Response

(18) FEMA should introduce smaller disaster-assistance grants for extreme weather disasters: HMAG, CMAG, and SMAG (Heat, Cold, and Smoke Management Assistance Grants, respectively). They should be modeled on FMAG grants, which are rapidly awarded when firefighting costs exceed available resources but do not necessarily escalate to the level of a major disaster declaration. For extreme weather disasters, the model would be similar, but the eligible activities might focus on climate-controlled shelters, outreach teams to reach especially vulnerable populations, or a surge in medical personnel and equipment. Just like firefighting equipment and staff needed to fight wildfires, this equipment and staff are needed to reduce the impacts of the disaster. FMAG is supported by the Disaster Relief Fund, so if the H/C/SMAG programs also tap that, it will require additional appropriations. Shelters are already supported by the Public Assistance (PA) program, but PA requires a major disaster declaration, so the introduction of lower-threshold funds would increase access.

(19) HHS could activate Disaster Medical Assistance Teams to mitigate any surge in medical needs. These teams are intended to provide a surge in medical support during a disaster and are deployed in other disasters. See our other memos on this topic.

(20) FEMA could deploy Incident Management Assistance Teams and supporting gear for additional logistics. They can also deploy backup energy resources such as generators to prevent energy failure at critical infrastructure.

Recovery and Mitigation

(21) Programs addressing gray or green infrastructure should consider the impact upgrades will have on heat mitigation. For example, EPA and DOE programs funding upgrades to school gray infrastructure should explicitly consider whether proposed upgrades will meet the heat mitigation needs based on climate projections. Projects funding schoolyard redesign should explicitly consider heat when planning blacktop, playground, and greenspace placement to avoid accidentally creating hot spots where children play. CAL FIRE’s grant to provide $47 million for schools to convert asphalt to green space is a state-level example.

(22) Expand the eligible actions of FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) to include installation/upgrade of heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC) systems and a more expansive program to support nature-based solutions (NBS) like green space installation. Existing guidance allows HVAC mitigation for other hazards and incentivizes NBS for other hazards.

(23) Increase alignment across federal programs, identifying programs where goals align. For example, FEMA just announced that solar panels would be eligible for the 75% federal cost share as part of mitigation programs; other climate and weatherization improvements should also be eligible under HMA funds.

(24) FEMA should modify its Benefit Cost Analysis (BCA) process to fairly evaluate mitigation of health and life-safety hazards, to better account for mitigation of multiple hazards, and to address equity considerations introduced in Office of Management and Budget’s recent BCA proposal. Some research is likely needed (e.g., the cost-effectiveness of various nature-based solutions like green space is not yet well-defined enough to use in a BCA); this research could be performed by national labs, put into FEMA’s Learning Agenda, or tasked to a partner agency like DOE.

(25) Expand the definition of medical devices to include items that protect against extreme weather. For example, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services could define air-conditioning units and innovative personal cooling devices as eligible for prescription under Medicare/Medicaid.

To support the above recommendations, Congress should:

(26) Ensure FEMA is sufficiently and consistently funded to conduct resilience and adaptation activities. Congress augments the Disaster Relief Fund in response to disasters, but they report that the fund will be billions of dollars in deficit by September 2024. It has furthermore been reported that FEMA has delayed payments due to uncertainty of funding through Congressional budget negotiations. In order to support the above programs, it is essential that Congress fund FEMA at a level needed to act. To support FEMA’s shift to a focus on resilience, the increase in funding should be through annual appropriations rather than the Disaster Relief Fund, which is augmented on an ad hoc basis.

(27) Convene a congressional commission like the recent Wildland Fire Commission to analyze the federal capabilities around extreme weather disasters and/or extreme heat. This commission would help source additional ideas and identify political pathways toward creating these solutions, and is merited by the magnitude of the disaster.

Conclusion

People across the U.S. are being increasingly exposed to extreme heat and other people-centered disasters. The suggested policies and programs are needed to upgrade national emergency management for the modern and future era, thereby saving lives and reducing disaster costs to the public.

We estimate a minimum of 1,670 deaths and $157.8 billion of annual heat impacts. These deaths and dollar amounts exceed almost every recorded disaster in U.S. history. Only COVID-19, 9/11, and Hurricanes Maria and Katrina have more deaths, and only Hurricanes Katrina and Harvey have caused more dollar damage. It should be noted that most of the estimates reported are several years out of date and exclude major heat waves of 2021 and 2022. For example, individual heat waves produced sizable numbers of deaths, including 395 deaths in a 2022 California heat wave and 600 deaths in the 2021 Pacific Northwest heatwave.

- Health ($20 billion): The CDC’s 2022 Mortality Statistics estimates 1,670 deaths annually are attributable to extreme heat. Using FEMA’s estimate of the Value of a Statistical Life ($11.6 million 2022 USD), that is $19.4 billion. Additional costs come from the burden on the healthcare system, which is estimated at $1 billion annually.

- Infrastructure ($1–16 billion): The impacts of extreme heat are estimated at $1 billion in 2020 and are projected to impose a cost burden of approximately $26 billion on the U.S. transportation sector by the year 2040. Agriculture loses billions of dollars each year from natural hazards. Drought, made worse by high heat conditions, accounts for a significant amount of the losses. In 2023, 80% of emergency disaster designations declared by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) were for drought or excessive heat. In 2023, the Southern/Midwestern drought and heatwave was the costliest disaster, at $14.5 billion in losses.

- Workforce ($136.8 billion annually): Between 2011 and 2019, an average of 2,700 heat-related injuries and 38 heat-related fatalities were reported annually to OSHA ($36.8 billion annually using the VSL). Lost work productivity is a major impact of extreme heat that is currently unaccounted for, but was estimated at $100 billion for 2020 and is projected to reach $500 billion by 2050.

- Other people-centered disasters: There are an estimated 6,000 annual acute and chronic deaths due to wildfire smoke (spanning 2006–2018) and 1,300 deaths attributable to extreme cold (estimates prior to 2010). These health impacts are comparable to those of extreme heat, and again even these high impacts exclude recent smoke waves of 2020, 2021, and 2023 and cold waves of 2021 and 2022.

It is insufficient to just add heat to the list of disasters enumerated in the Stafford Act because it omits (1) the important recognition of compound events that often are associated with extreme heat, (2) other people-centered disasters like smoke waves, and (3) the ability to measure these disasters. We, therefore, recommend some version of the following text:

Section 102(2) of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5122(2)) is amended by striking “or drought” and inserting “drought, heat, smoke, or any other weather pattern causing a combination of the above”.

Section 102 of the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (42 U.S.C. 5122(2)) is amended by inserting

(13) DAMAGE—“Damage” means–

- (A) Loss of life or health impacts requiring medical care

- (B) Loss of property or impacts on property reducing its ability to function

- (C) Diminished usable lifespan for infrastructure

- (D) Economic damage, which includes the value of a statistical life, burden on the healthcare system due to injury, burden on the economy placed by lost days of work or school, agricultural losses, or any other economic damage that is directly measurable or calculated.

- (E) Infrastructure failure of any duration, including temporary, that could lead to any of the above

Tracking and Preventing the Health Impacts of Extreme Heat

The response to the 9/11 terrorist attacks included building from scratch a bioterrorism-monitoring system that remains a model for public health systems worldwide. Today we face a similarly galvanizing moment: weather-related hazards cause multiple times the 9/11 death toll each year, with extreme heat often termed the “top weather killer,” at 1,670 official deaths a year and 10,000 attributed via excess deaths analysis. Extreme cold and dense wildfire smoke each cause comparable numbers of deaths. By rapidly upgrading and expanding the health-tracking systems of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Veterans Health Administration (VHA), and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) to improve real-time surveillance of health impacts of climate change, the U.S. can similarly meet the current moment to promote climate-conscientious care that save lives.

Challenge and Opportunity

The official death toll of extreme heat since 1979 stands at over 11,000, but the methods used to develop this count are known to underestimate the true impacts of heat waves. The undercounting of deaths related to extreme heat and other people-centered disasters — like extreme cold and smoke waves — hinders the political and public drive to address the problem and adds difficulty to declaring heat waves as disasters despite the massive loss of life. Similarly, the lack of integration of critical environmental data like “wet bulb” temperature alongside these health impacts in electronic data systems hinders the provision of medical care.

National Accounting

The national reaction to the 9/11 terrorist attacks provides a roadmap forward: improved data and tracking is fundamental to a nation’s evidence-based threat response. Operated by federal, state, and local public health professionals who comprise the CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP), surveillance systems were developed across the nation to meet new challenges in disease detection and situational awareness. Since 2020, the CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative (DMI) has provided a framework for this transformation, with the stated goal of improving the nation’s ability to predict, understand, and share data on new health threats in real time. While the DMI has focused on the pioneering role of new technologies for health protection, this effort also offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity for the public health and medical surveillance establishment to increase their capacity to address pressing future threats to the nation’s welfare, including the evolving climate crisis. Increasingly, extreme weather is responsible for both near-term disasters (more frequent and intense heat waves, dense smoke waves, and cold waves) and the long-term exacerbation of prevalent health conditions (such as heart, lung, and neurological disease). Its increasingly severe impacts demand a detailed and funded roadmap to attain the DMI’s goals of “real-time, scalable emergency response” capability.

Patient Care