Fighting Fakes and Liars’ Dividends: We Need To Build a National Digital Content Authentication Technologies Research Ecosystem

The U.S. faces mounting challenges posed by increasingly sophisticated synthetic content. Also known as digital media ( images, audio, video, and text), increasingly, these are produced or manipulated by generative artificial intelligence (AI). Already, there has been a proliferation in the abuse of generative AI technology to weaponize synthetic content for harmful purposes, such as financial fraud, political deepfakes, and the non-consensual creation of intimate materials featuring adults or children. As people become less able to distinguish between what is real and what is fake, it has become easier than ever to be misled by synthetic content, whether by accident or with malicious intent. This makes advancing alternative countermeasures, such as technical solutions, more vital than ever before. To address the growing risks arising from synthetic content misuse, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) should take the following steps to create and cultivate a robust digital content authentication technologies research ecosystem: 1) establish dedicated university-led national research centers, 2) develop a national synthetic content database, and 3) run and coordinate prize competitions to strengthen technical countermeasures. In turn, these initiatives will require 4) dedicated and sustained Congressional funding of these initiatives. This will enable technical countermeasures to be able to keep closer pace with the rapidly evolving synthetic content threat landscape, maintaining the U.S.’s role as a global leader in responsible, safe, and secure AI.

Challenge and Opportunity

While it is clear that generative AI offers tremendous benefits, such as for scientific research, healthcare, and economic innovation, the technology also poses an accelerating threat to U.S. national interests. Generative AI’s ability to produce highly realistic synthetic content has increasingly enabled its harmful abuse and undermined public trust in digital information. Threat actors have already begun to weaponize synthetic content across a widening scope of damaging activities to growing effect. Project losses from AI-enabled fraud are anticipated to reach up to $40 billion by 2027, while experts estimate that millions of adults and children have already fallen victim to being targets of AI-generated or manipulated nonconsensual intimate media or child sexual abuse materials – a figure that is anticipated to grow rapidly in the future. While the widely feared concern of manipulative synthetic content compromising the integrity of the 2024 U.S. election did not ultimately materialize, malicious AI-generated content was nonetheless found to have shaped election discourse and bolstered damaging narratives. Equally as concerning is the accumulative effect this increasingly widespread abuse is having on the broader erosion of public trust in the authenticity of all digital information. This degradation of trust has not only led to an alarming trend of authentic content being increasingly dismissed as ‘AI-generated’, but has also empowered those seeking to discredit the truth, or what is known as the “liar’s dividend”.

A. In March 2023, a humorous synthetic image of Pope Francis, first posted on Reddit by creator Pablo Xavier, wearing a Balenciaga coat quickly went viral across social media.

B. In May 2023, this synthetic image was duplicitously published on X as an authentic photograph of an explosion near the Pentagon. Before being debunked by authorities, the image’s widespread circulation online caused significant confusion and even led to a temporary dip in the U.S. stock market.

Research has demonstrated that current generative AI technology is able to produce synthetic content sufficiently realistic enough that people are now unable to reliably distinguish between AI-generated and authentic media. It is no longer feasible to continue, as we currently do, to rely predominantly on human perception capabilities to protect against the threat arising from increasingly widespread synthetic content misuse. This new reality only increases the urgency of deploying robust alternative countermeasures to protect the integrity of the information ecosystem. The suite of digital content authentication technologies (DCAT), or techniques, tools, and methods that seek to make the legitimacy of digital media transparent to the observer, offers a promising avenue for addressing this challenge. These technologies encompass a range of solutions, from identification techniques such as machine detection and digital forensics to classification and labeling methods like watermarking or cryptographic signatures. DCAT also encompasses technical approaches that aim to record and preserve the origin of digital media, including content provenance, blockchain, and hashing.

Evolution of Synthetic Media

Published in 2018, this now infamous PSA sought to illustrate the dangers of synthetic content. It shows an AI-manipulated video of President Obama, using narration from a comedy sketch by comedian Jordan Peele.

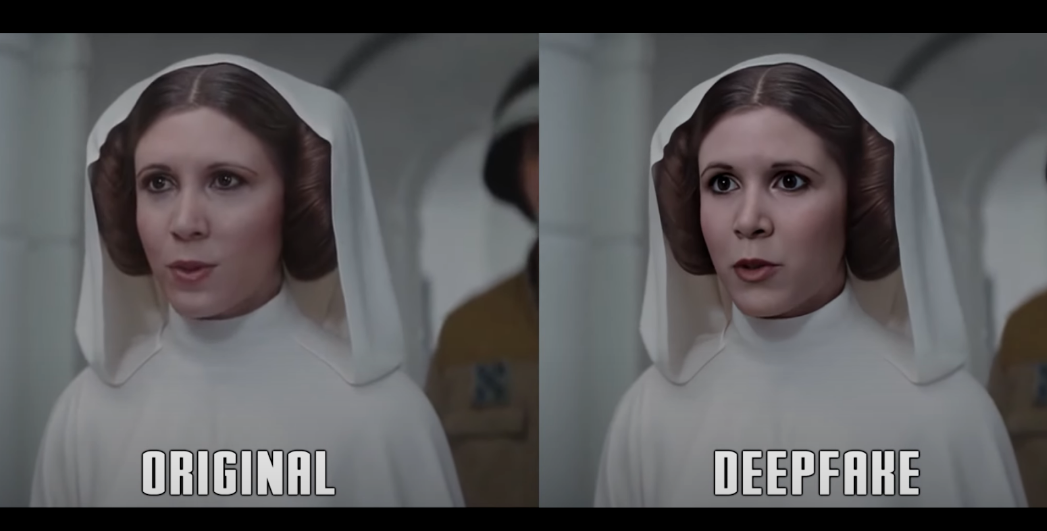

In 2020, a hobbyist creator employed an open-source generative AI model to ‘enhance’ the Hollywood CGI version of Princess Leia in the film Rouge One.

The hugely popular Tiktok account @deeptomcruise posts parody videos featuring a Tom Cruise imitator face-swapped with the real Tom Cruise’s real face, including this 2022 video, racking up millions of views.

The 2024 film Here relied extensively on generative AI technology to de-age and face-swap actors in real-time as they were being filmed.

Robust DCAT capabilities will be indispensable for defending against the harms posed by synthetic content misuse, as well as bolstering public trust in both information systems and AI development. These technical countermeasures will be critical for alleviating the growing burden on citizens, online platforms, and law enforcement to manually authenticate digital content. Moreover, DCAT will be vital for enforcing emerging legislation, including AI labeling requirements and prohibitions on illegal synthetic content. The importance of developing these capabilities is underscored by the ten bills (see Fig 1) currently under Congressional consideration that, if passed, would require the employment of DCAT-relevant tools, techniques, and methods.

However, significant challenges remain. DCAT capabilities need to be improved, with many currently possessing weaknesses or limitations such brittleness or security gaps. Moreover, implementing these countermeasures must be carefully managed to avoid unintended consequences in the information ecosystem, like deploying confusing or ineffective labeling to denote the presence of real or fake digital media. As a result, substantial investment is needed in DCAT R&D to develop these technical countermeasures into an effective and reliable defense against synthetic content threats.

The U.S. government has demonstrated its commitment to advancing DCAT to reduce synthetic content risks through recent executive actions and agency initiatives. The 2023 Executive Order on AI (EO 14110) mandated the development of content authentication and tracking tools. Charged by the EO 14110 to address these challenges, NIST has taken several steps towards advancing DCAT capabilities. For example, NIST’s recently established AI Safety Institute (AISI) takes the lead in championing this work in partnership with NIST’s AI Innovation Lab (NAIIL). Key developments include: the dedication of one of the U.S. Artificial Intelligence Safety Institute Consortium’s (AISIC) working groups to identifying and advancing DCAT R&D; the publication of NIST AI 100-4, which “examines the existing standards, tools, methods, and practices, as well as the potential development of further science-backed standards and techniques” regarding current and prospective DCAT capabilities; and the $11 million dedicated to international research on addressing dangers arising from synthetic content announced at the first convening of the International Network of AI Safety Institutes. Additionally, NIST’s Information Technology Laboratory (ITL) has launched the GenAI Challenge Program to evaluate and advance DCAT capabilities. Meanwhile, two pending bills in Congress, the Artificial Intelligence Research, Innovation, and Accountability Act (S. 3312) and the Future of Artificial Intelligence Innovation Act (S. 4178), include provisions for DCAT R&D.

Although these critical first steps have been taken, an ambitious and sustained federal effort is necessary to facilitate the advancement of technical countermeasures such as DCAT. This is necessary to more successfully combat the risks posed by synthetic content—both in the immediate and long-term future. To gain and maintain a competitive edge in the ongoing race between deception and detection, it is vital to establish a robust national research ecosystem that fosters agile, comprehensive, and sustained DCAT R&D.

Plan of Action

NIST should engage in three initiatives: 1) establishing dedicated university-based DCAT research centers, 2) curating and maintaining a shared national database of synthetic content for training and evaluation, as well as 3) running and overseeing regular federal prize competitions to drive innovation in critical DCAT challenges. The programs, which should be spearheaded by AISI and NAIIL, are critical for enabling the creation of a robust and resilient U.S. DCAT research ecosystem. In addition, the 118th Congress should 4) allocate dedicated funding to supporting these enterprises.

These recommendations are not only designed to accelerate DCAT capabilities in the immediate future, but also to build a strong foundation for long-term DCAT R&D efforts. As generative AI capabilities expand, authentication technologies must too keep pace, meaning that developing and deploying effective technical countermeasures will require ongoing, iterative work. Success demands extensive collaboration across technology and research sectors to expand problem coverage, maximize resources, avoid duplication, and accelerate the development of effective solutions. This coordinated approach is essential given the diverse range of technologies and methodologies that must be considered when addressing synthetic content risks.

Recommendation 1. Establish DCAT Research Institutes

NIST should establish a network of dedicated university-based research to scale up and foster long-term, fundamental R&D on DCAT. While headquartered at leading universities, these centers would collaborate with academic, civil society, industry, and government partners, serving as nationwide focal points for DCAT research and bringing together a network of cross-sector expertise. Complementing NIST’s existing initiatives like the GenAI Challenge, the centers’ research priorities would be guided by AISI and NAIIL, with expert input from the AISIC, the International Network of AISI, and other key stakeholders.

A distributed research network offers several strategic advantages. It leverages elite expertise from industry and academia, and having permanent institutions dedicated to DCAT R&D enables the sustained, iterative development of authentication technologies to better keep pace with advancing generative AI capabilities. Meanwhile, central coordination by AISI and NAIIL would also ensure comprehensive coverage of research priorities while minimizing redundant efforts. Such a structure provides the foundation for a robust, long-term research ecosystem essential for developing effective countermeasures against synthetic content threats.

There are multiple pathways via which dedicated DCAT research centers could be stood up. One approach is direct NIST funding and oversight, following the model of Carnegie Mellon University’s AI Cooperative Research Center. Alternatively, centers could be established through the National AI Research Institutes Program, similar to the University of Maryland’s Institute for Trustworthy AI in Law & Society, leveraging NSF’s existing partnership with NIST.

The DCAT research agenda could be structured in two ways. Informed by NIST’s report NIST AI 100-4, a vertical approach could be taken to centers’ research agendas, assigning specific technologies to each center (e.g. digital watermarking, metadata recording, provenance data tracking, or synthetic content detection). Centers would focus on all aspects of a specific technical capability, including: improving the robustness and security of existing countermeasures; developing new techniques to address current limitations; conducting real-world testing and evaluation, especially in a cross-platform environment; and studying interactions with other technical safeguards and non-technical countermeasures like regulations or educational initiatives. Conversely, a horizontal approach might seek to divide research agendas across areas such as: the advancement of multiple established DACT techniques, tools, and methods; innovation of novel techniques, tools, and methods; testing and evaluation of combined technical approaches in real-world settings; examining the interaction of multiple technical countermeasures with human factors such as label perception and non-technical countermeasures. While either framework provides a strong foundation for advancing DCAT capabilities, given institutional expertise and practical considerations, a hybrid model combining both approaches is likely the most feasible option.

Recommendation 2. Build and Maintain a National Synthetic Content Database

NIST should also build and maintain a national database of synthetic content database to advance and accelerate DCAT R&D, similar to existing federal initiatives such as NIST’s National Software Reference Library and NSF’s AI Research Resource pilot. Current DCAT R&D is severely constrained by limited access to diverse, verified, and up-to-date training and testing data. Many researchers, especially in academia, where a significant portion of DCAT research takes place, lack the resources to build and maintain their own datasets. This results in less accurate and more narrowly applicable authentication tools that struggle to keep pace with rapidly advancing AI capabilities.

A centralized database of synthetic and authentic content would accelerate DCAT R&D in several critical ways. First, it would significantly alleviate the effort on research teams to generate or collect synthetic data for training and evaluation, encouraging less well-resourced groups to conduct research as well as allowing researchers to focus more on other aspects of R&D. This includes providing much-needed resources for the NIST-facilitated university-based research centers and prize competitions proposed here. Moreover, a shared database would be able to provide more comprehensive coverage of the increasingly varied synthetic content being created today, permitting the development of more effective and robust authentication capabilities. The database would be useful for establishing standardized evaluation metrics for DCAT capabilities – one of NIST’s critical aims for addressing the risks posed by AI technology.

A national database would need to be comprehensive, encompassing samples of both early and state-of-the-art synthetic content. It should have controlled laboratory-generated along with verified “in the wild” or real world synthetic content datasets, including both benign and potentially harmful examples. Further critical to the database’s utility is its diversity, ensuring synthetic content spans multiple individual and combined modalities (text, image, audio, video) and features varied human populations as well as a variety of non-human subject matter. To maintain the database’s relevance as generative AI capabilities continue to evolve, routinely incorporating novel synthetic content that accurately reflects synthetic content improvements will also be required.

Initially, the database could be built on NIST’s GenAI Challenge project work, which includes “evolving benchmark dataset creation”, but as it scales up, it should operate as a standalone program with dedicated resources. The database could be grown and maintained through dataset contributions by AISIC members, industry partners, and academic institutions who have either generated synthetic content datasets themselves or, as generative AI technology providers, with the ability to create the large-scale and diverse datasets required. NIST would also direct targeted dataset acquisition to address specific gaps and evaluation needs.

Recommendation 3. Run Public Prize Competitions on DCAT Challenges

Third, NIST should set up and run a coordinated prize competition program, while also serving as federal oversight leads for prize competitions run by other agencies. Building on existing models such as the DARPA SemaFor’s AI FORCE and the FTC’s Voice Cloning challenge, the competitions would address expert-identified priorities as informed by the AISIC, International Network of AISI, and proposed DCAT national research centers. Competitions represent a proven approach to spurring innovation for complex technical challenges, enabling the rapid identification of solutions through diverse engagement. In particular, monetary prize competitions are especially successful at ensuring engagement. For example, the 2019 Kaggle Deepfake Detection competition, which had a prize of $1 million, fielded twice as many participants as the 2024 competition, which gave no cash prize.

By providing structured challenges and meaningful incentives, public competitions can accelerate the development of critical DCAT capabilities while building a more robust and diverse research community. Such competitions encourage novel technical approaches, rapid testing of new methods, facilitate the inclusion of new or non-traditional participants, and foster collaborations. The more rapid-cycle and narrow scope of the competitions would also complement the longer-term and broader research being conducted by the national DCAT research centers. Centralized federal oversight would also prevent the implementation gaps which have occurred in past approved federal prize competitions. For instance, the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) authorized a $5 million machine detection/deepfakes prize competition (Sec. 5724), and the 2024 NDAA authorized a ”Generative AI Detection and Watermark Competition” (Sec. 1543). However, neither prize competition has been carried out, and Watermark Competition has now been delayed to 2025. Centralized oversight would also ensure that prize competitions are run consistently to address specific technical challenges raised by expert stakeholders, encouraging more rapid development of relevant technical countermeasures.

Some examples of possible prize competitions might include: machine detection and digital forensic methods to detect partial or fully AI-generated content across single or multimodal content; assessing the robustness, interoperability, and security of watermarking and other labeling methods across modalities; testing innovations in tamper-evident or -proofing content provenance tools and other data origin techniques. Regular assessment and refinement of competition categories will ensure continued relevance as synthetic content capabilities evolve.

Recommendation 4. Congressional Funding of DCAT Research and Activities

Finally, the 118th Congress should allocate funding for these three NIST initiatives in order to more effectively establish the foundations of a strong DCAT national research infrastructure. Despite widespread acknowledgement of the vital role of technical countermeasures in addressing synthetic content risks, the DCAT research field remains severely underfunded. Although recent initiatives, such as the $11 million allocated to the International Network of AI Safety Institutes, are a welcome step in the right direction, substantially more investment is needed. Thus far, the overall financing of DCAT R&D has been only a drop in the bucket when compared to the many billions of dollars being dedicated by industry alone to improve generative AI technology.

This stark disparity between investment in generative AI versus DCAT capabilities presents an immediate opportunity for Congressional action. To address the widening capability gap, and to support pending legislation which will be reliant on technical countermeasures such as DCAT, the 118th Congress should establish multi-year appropriations with matching fund requirements. This will encourage private sector investment and permit flexible funding mechanisms to address emerging challenges. This funding should be accompanied by regular reporting requirements to track progress and impact.

One specific action that Congress could take to jumpstart DCAT R&D investment would be to reauthorize and appropriate the budget that was earmarked for the unexecuted machine detection competition it approved in 2020. Despite the 2020 NDAA authorizing $5 million for it, no SAC-D funding was allocated, and the competition never took place. Another action would be for Congress to explicitly allocate prize money for the watermarking competition authorized by the 2024 NDAA, which currently does not have any monetary prize attached to it, to encourage higher levels of participation in the competition when it takes place this year.

Conclusion

The risks posed by synthetic content present an undeniable danger to U.S. national interests and security. Advancing DCAT capabilities is vital for protecting U.S. citizens against both the direct and more diffuse harms resulting from the proliferating misuse of synthetic content. A robust national DCAT research ecosystem is required to accomplish this. Critically, this is not a challenge that can be addressed through one-time solutions or limited investment—it will require continuous work and dedicated resources to ensure technical countermeasures keep pace alongside increasingly sophisticated synthetic content threats. By implementing these recommendations with sustained federal support and investment, the U.S. will be able to more successfully address current and anticipated synthetic content risks, further reinforcing its role as a global leader in responsible AI use.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

We Need Biological Verification and Attribution Tools to Combat Disinformation Aimed at International Institutions

The Biological Weapons Convention’s Ninth Review Conference (RevCon) took place under a unique geopolitical storm, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged and the Russian invasion of Ukraine took center stage. Russia’s continued claims of United States-sponsored bioweapons research laboratories in Ukraine only added to the tension. Russia asserted that they had uncovered evidence of offensive biological weapons research underway in Ukrainian labs, supported by the United States, and that the invasion of Ukraine was due to the threat they faced so close to their borders.

While this story has been repeated countless times to countless audiences – including an Article V consultative meeting and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) as part of an Article VI complaint against the U.S. lodged by Russia, the fact remains that Russia’s assertion is untrue.

The biological laboratories present in Ukraine operate as part of the Department of Defense’s Biological Threat Reduction Program, and are run by Ukrainian scientists charged with detecting and responding to emerging pathogens in the area. Articles V and VI of the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) are intended to be invoked when a State Party hopes to resolve a problem of cooperation or report a breach of the Convention, respectively. The Article V formal consultative meeting resulted in no consensus being reached, and the Article VI UNSC meeting rejected Russia’s claims. The lack of consensus during the consultative meeting created a foothold for Russia to continue their campaign of disinformation, and the UNSC meeting only further reinforced it. The Article V and VI clauses are meant to provide some means of mediation and recourse to States Parties in the case of BWC violation. However, in this case they were not invoked in good faith, rather, they were used as a springboard for a sweeping Russian disinformation campaign.

Abusing Behavioral Norms for Political Gain

While Russia’s initial steps of calling for an Article V consultative meeting and an Article VI Security Council investigation do not seem outwardly untoward, Russia’s behavior during and after these proceedings dismissed the claims indicated their deeper purpose.

Example: Misdirection in Documentation Review

During the RevCon, the Russian delegation often brought up how the results of the UNSC investigation would be described in the final document during the article-by-article review, calling for versions of the document that included more slanted versions of the events. They also continually mentioned the U.S.’ refusal to answer their questions, despite the answers being publicly available on the consultative meeting’s UNODA page, the Russians characterized their repeated mentioning of the UNSC investigation findings as an act of defiant heroism, implying that the U.S. was trying to quash their valid concerns, but that Russia would continue to raise them until the world had gotten the answers it deserved. This narrative directly contradicts the facts of the Article V and VI proceedings. The UNSC saw no need to continue investigating Russia’s claims.

Example: Side Programming with Questionable Intent

The Russian delegation also conducted a side event during the BWC dedicated to the outcomes of the consultative meeting. The side event included a short ‘documentary’ of Russian evidence that the U.S.-Ukraine laboratories were conducting biological weapons research. This evidence included footage of pesticide-dispersal drones in a parking lot that were supposedly modified to hold bioweapons canisters, cardboard boxes with USAID stickers on them, and a list of pathogen samples supposedly present that were destroyed prior to filming. When asked about next steps, the Russian delegation made thinly veiled threats to hold larger BWC negotiations hostage, stating that if the U.S. and its allies maintain their position and don’t demonstrate any further interest in continuing dialogue, it would be difficult for the 9th RevCon to reach consensus.

Example: Misuse of ‘Point of Order’

Russia’s behavior at the 9th RevCon emphasizes the unwitting role international institutions can play as springboards for state-sponsored propaganda and disinformation.

During opening statements, the Russian delegation continually called a point of order upon any mention of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. A point of order allows the delegation to respond to the speaker immediately, effectively interrupting their statement. During the Ukrainian delegation’s opening statement, the Russian delegation called four points of order, citing Ukraine’s “political statements” as disconnected from the BWC discussion. Russia’s use of the rules of procedure to bully other delegations continued – after they concluded a point of order during the NATO delegate’s statement, they called another one almost immediately after the NATO delegate resumed her statement with the singular word, “Russia.” This behavior continued throughout all three weeks of the RevCon.

Example: Single Vote Disruption Made in Bad Faith

All BWC votes are adopted by consensus, meaning that all states parties have to agree for a decision to be made. While this helps ensure the greatest inclusivity and equality between states parties, as well as promote implementation, it also means that one country can be the ‘spoiler’ and disrupt even widely supported changes.

For example, in 2001, the United States pulled out of verification mechanism negotiations at the last minute, upending the entire effort. Russia’s behavior in 2022 was similarly disruptive, but made with the goal of subversion. The vote changed how other delegations reacted, as representatives seemed more reluctant to mention the Article V and VI proceedings. The structure of the United Nations as impartial and the BWC as consensus-based means that by their very nature they cannot combat their misuse. Any progress to be had by the BWC relies on states operating in good faith, which is impossible to do when a country has a disinformation agenda.

Thus, the very nature of the UN and associated bodies attenuates their ability to respond to states’ misuse. Russia’s behavior at the 9th RevCon is part of a pattern that shows no signs of slowing down.

We Need More Sophisticated Biological Verification and Attribution Tools

The actions described above demonstrate the door has been kicked fully open for regimes to use the UN and associated bodies as mouthpieces for state-sponsored propaganda.

So, it is imperative that 1) more sophisticated biological verification and attribution tools be developed, and 2) the BWC implements a legally binding verification mechanism.

The development of better verification methods to verify whether biological research is for civil or military purposes will help to remove ambiguity around laboratory activities around the world. It will also make it harder for benign activities to be misidentified as offensive biological weapons activities.

Further, improved attribution methods will determine where biological weapons originate from and will further remove ambiguity during a genuine biological attack.

The development of both these capabilities will strengthen an eventual legally binding verification mechanism. These two changes will also allow Article V consultative meetings and Article VI UNSC meetings to determine the presence of offensive bioweapons research more definitively, thus contributing rather substantively to the strengthening of the convention. As ambiguity around the results of these investigations decreases, so does the space for disinformation to take hold.

“Expert” Opinion More Likely to Damage Vaccine Trust Than Political Propaganda

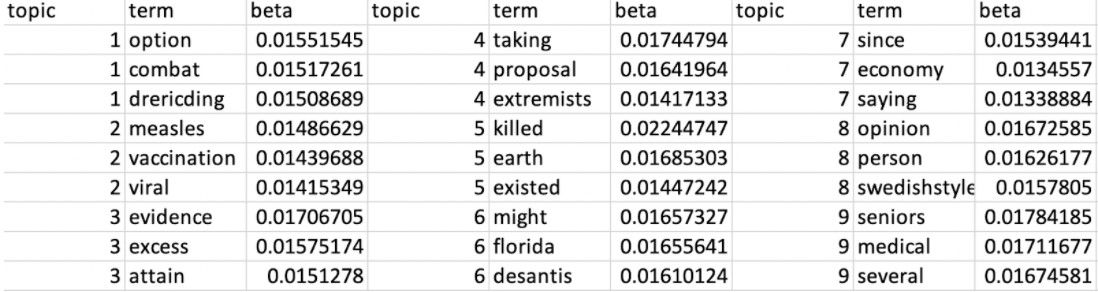

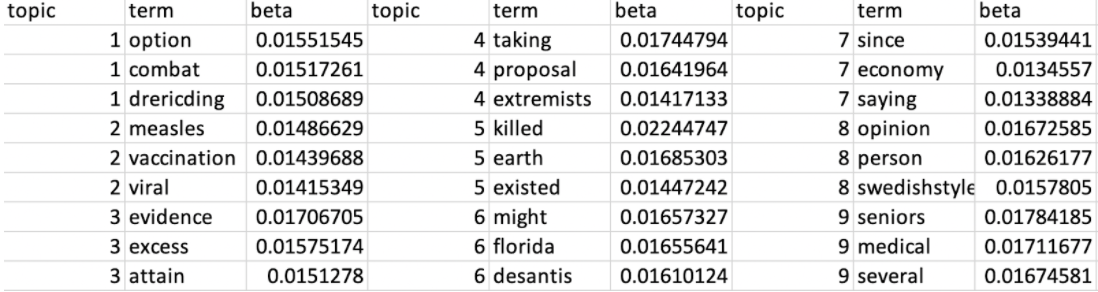

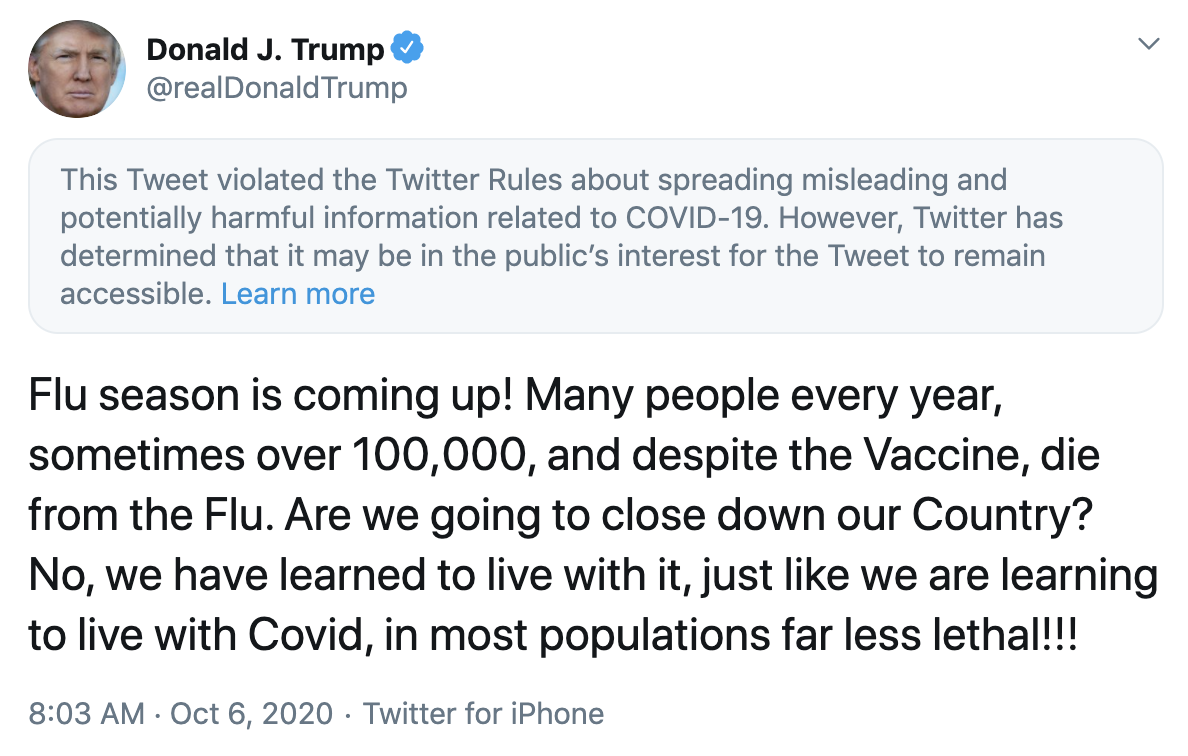

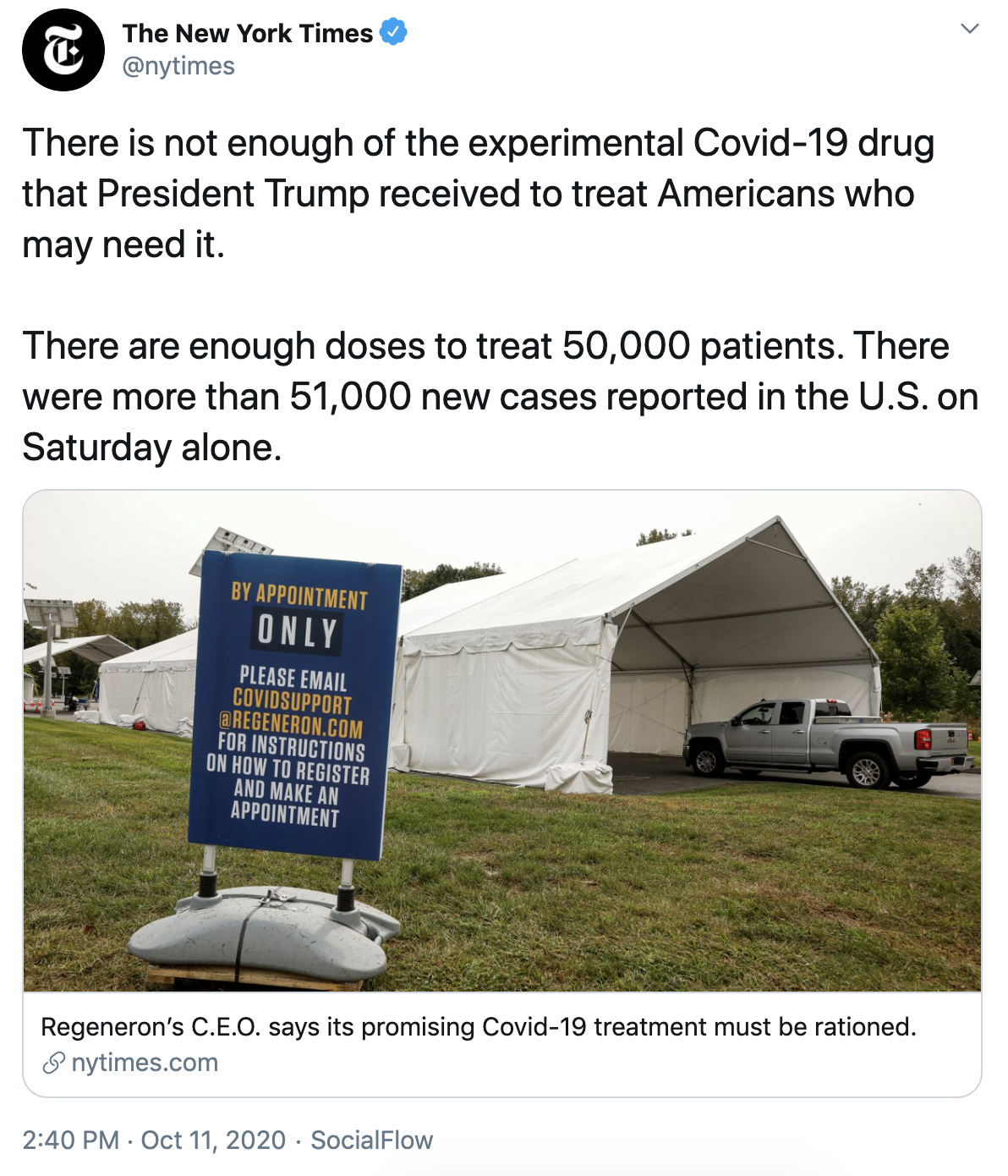

Our research shows that the biggest threat to reliable information access for military and DoD service members is expert opinion. A high-level analysis of anti-COVID vaccine narratives on social media reveals that opinions from experts achieve higher relevancy and engagement than opinions from news pundits, even if the news source is considered reliable by its base.

The Department of Defense administers 17 different vaccines for the prevention of infectious diseases among military personnel. These vaccines are distributed upon entering basic training and before deployment. By mid-July, 62% of active duty service members added vaccination against COVID-19 to that array. As impressive as that 62% is, it is not full compliance, and so in late August, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin ordered service leaders to “impose ambitious timelines for implementation” of a full-court press to vaccinate the entire armed forces.

Some Republican lawmakers, including military veterans, have opted to use policy to fight the military vaccine mandate. Representative Thomas Massie (R-KY) introduced a bill to prohibit federal funds from being used “to force” a member of the USAF to receive a COVID-19, while Representative Mark Green (R-TN) referred repeatedly to a lack of “longitudinal data” of the developed COVID-19 vaccines as the impetus for a bill that would allow unvaccinated servicemembers to be honorably discharged. Green, who is also a board-certified physician, has previously claimed that vaccines cause autism.

Users on Twitter and other social media platforms are looking for advice for themselves or family members in the service about how to navigate the new requirements. Days after Secretary Austin’s memo, a video of a self-proclaimed “tenured Navy surgeon” went viral, where she claims that the COVID-19 vaccine “killed more of our young active duty people than COVID did”, citing the open-source Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) Database which is unregulated and publicly editable. That doctor, associated with the COVID conspiracy group America’s Frontline Doctors, is one of many influencers who have targeted service members in their battle against vaccination.

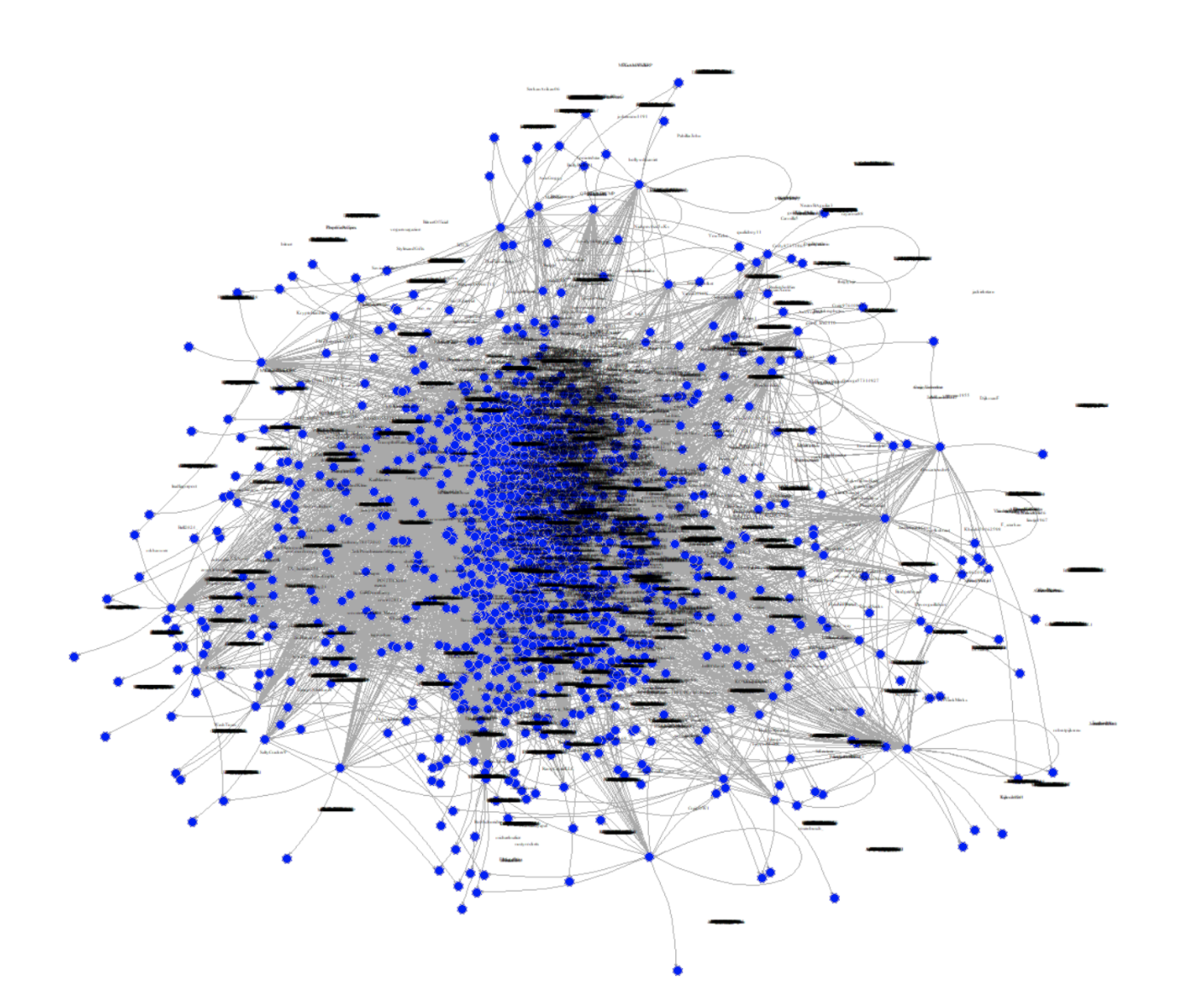

On social media, the doctor’s statement took off. A bot network amplified the narrative on Twitter, keeping it at the forefront of the vaccine conversation for weeks. The narrative also gained traction on web forums, where it was cited by soldiers looking for a credible reason to gain an exception to the vaccine mandate. Forums emerged with dozens of service members pointing to the doctor’s statements as fact, and discussing ways to skirt the mandate using religious exemptions, phony immunization cards, or other schemes. The right-wing social media website Gab has created a webpage with templates for users to send to their employers requesting religious exemptions that are being shared throughout military social media circles.

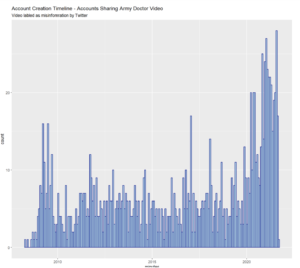

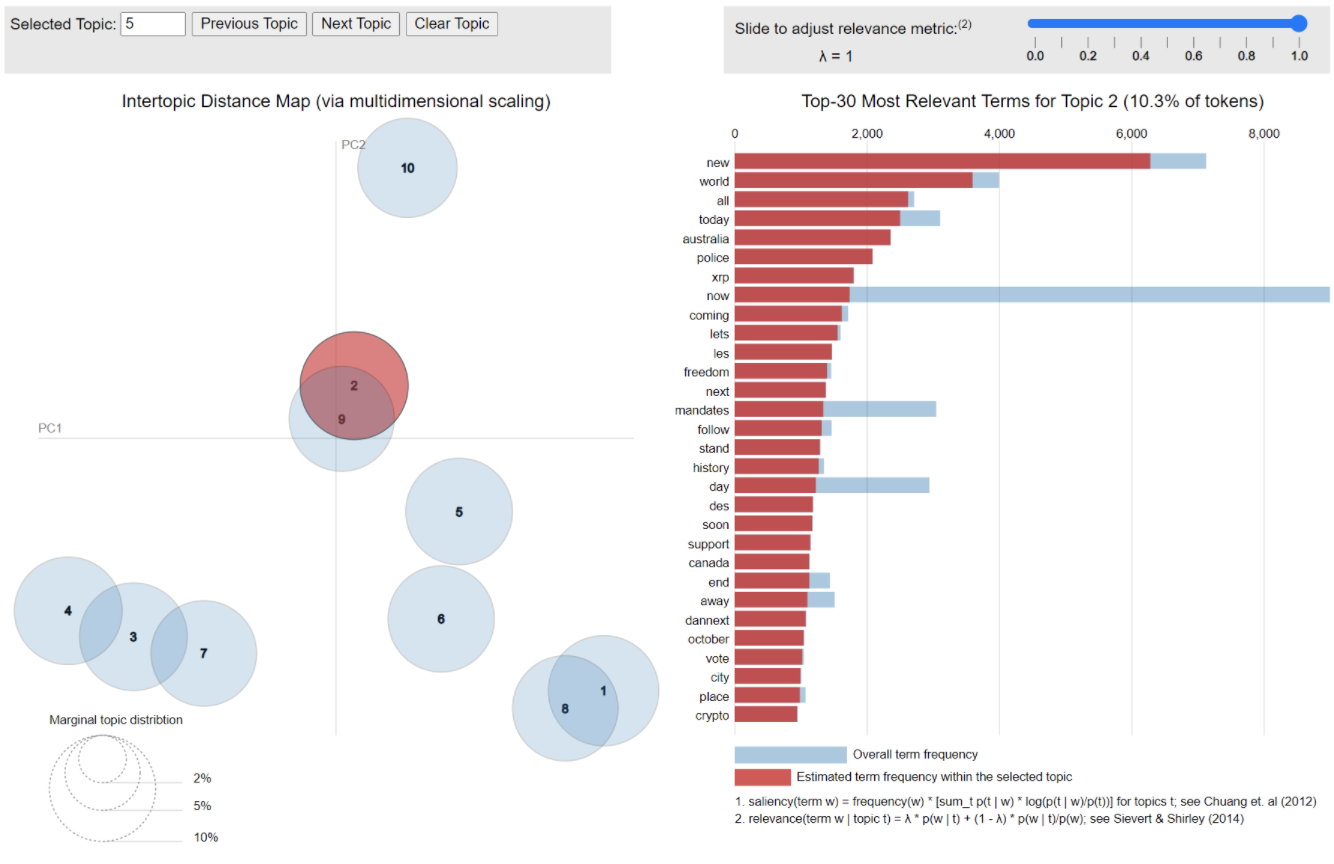

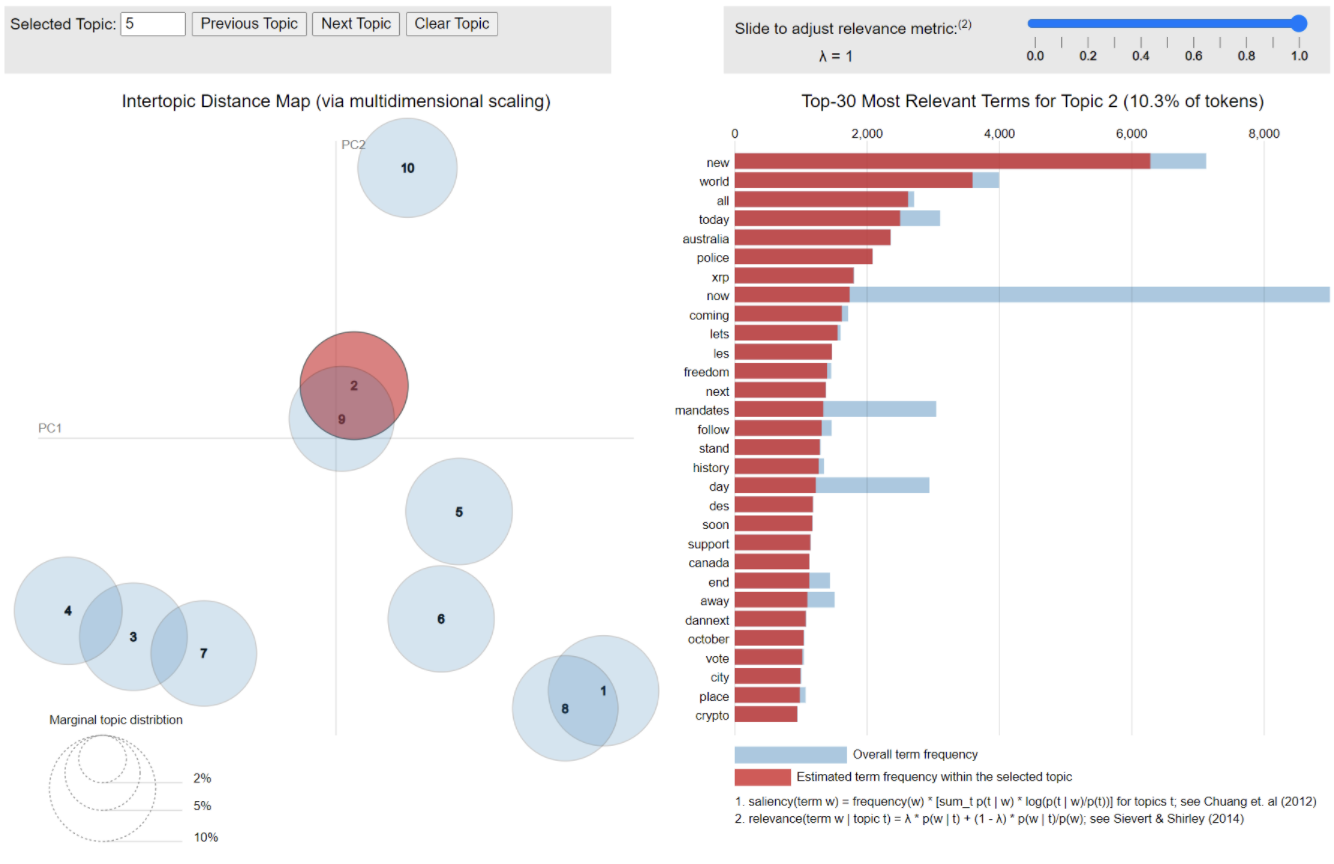

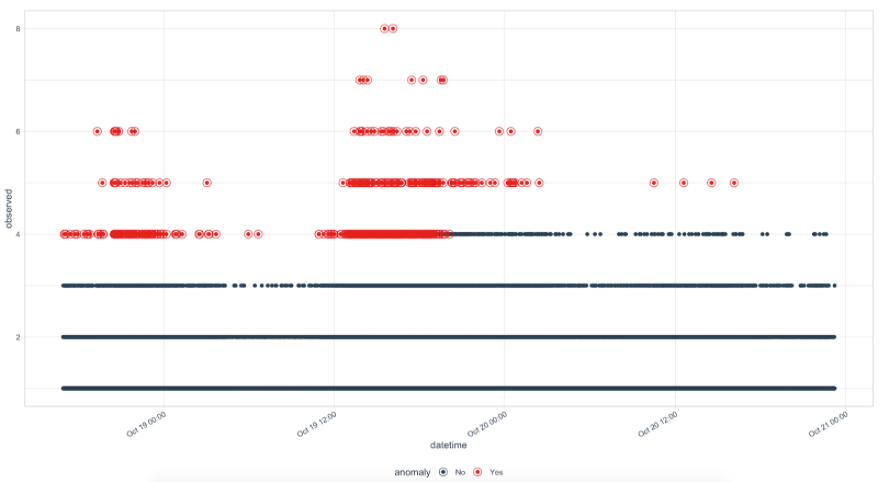

In the below analysis, we take a close look at the 1443 retweets of Dr. Merritt’s video. Assessing the accounts themselves, we see a large influx of accounts created in the last 9 months taking part in the conversation and we see statistically significant declines in the correlations between account behaviors, both of which suggest bot activity.

From the 1443 retweets, we find 1319 unique accounts, of which user data was available for 1314 accounts. Three comercial bot detector technologies agreed that 466 of these accounts – 35% – were bots. Two of three detectors found 514 bots in common. Assessing the post behaviors and posted content of these bot accounts, we find disinformation content related to COVID-19, vaccines, vaccine mandates, gun control, immigration, and school shootings in America.

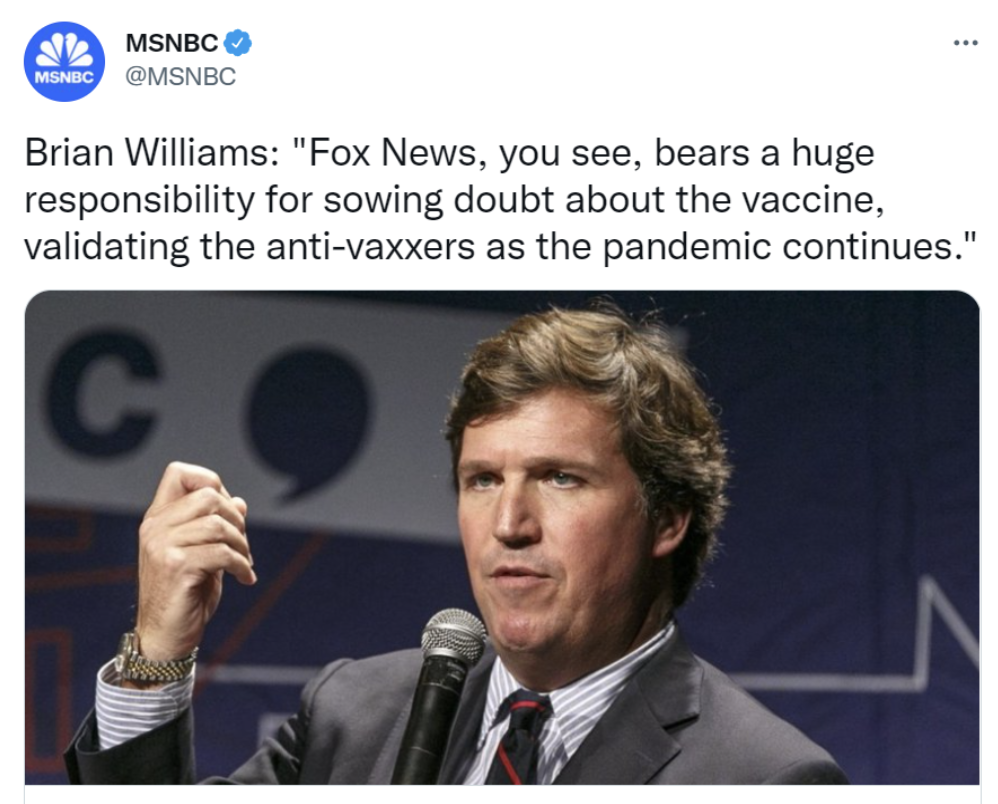

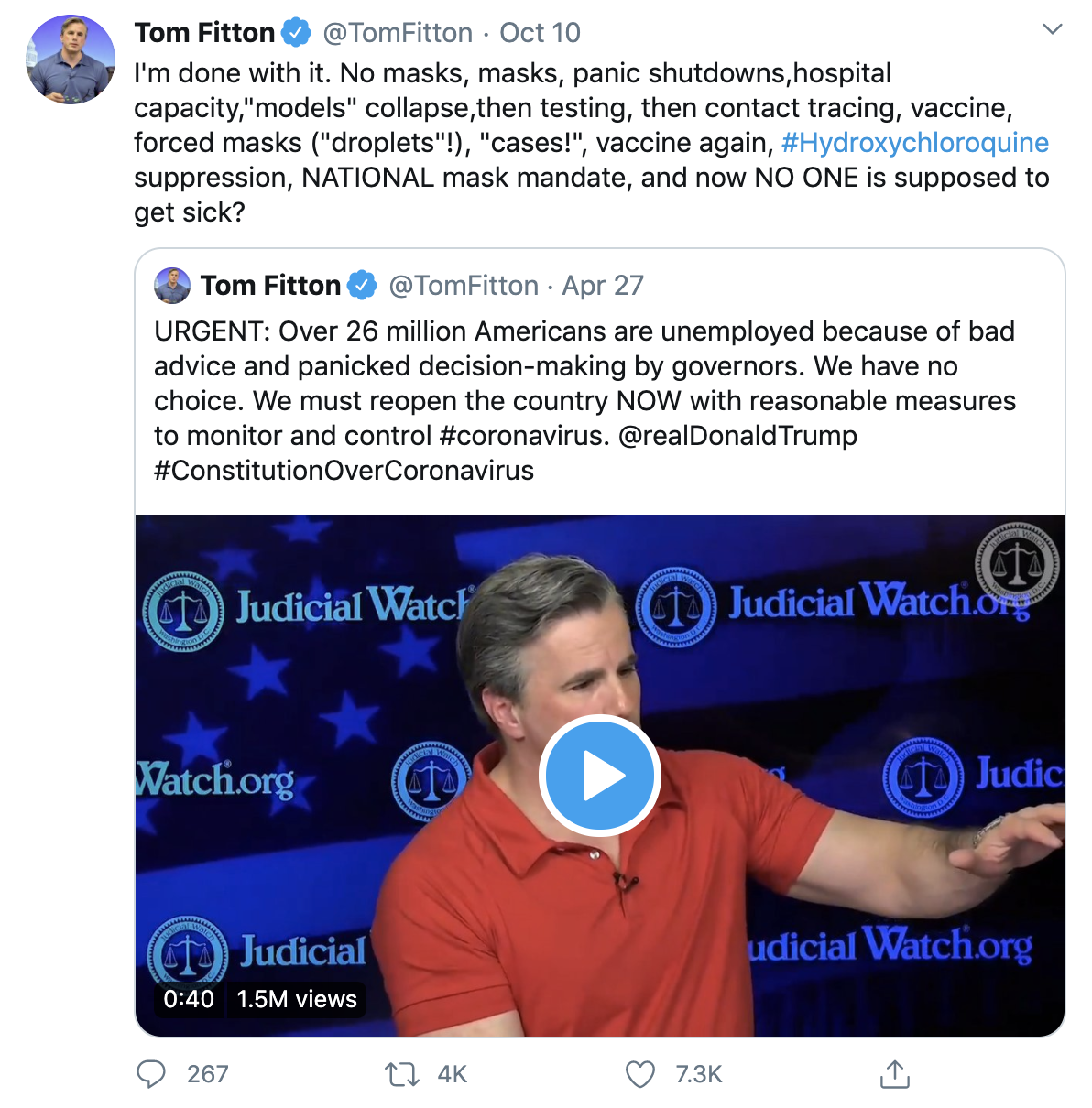

Around the same time, Fox News host Tucker Carlson labeled the vaccine mandate a plot to single out “the sincere Christians in the ranks, the free thinkers, the men with high testosterone levels, and anyone else who doesn’t love Joe Biden, and make them leave immediately.”

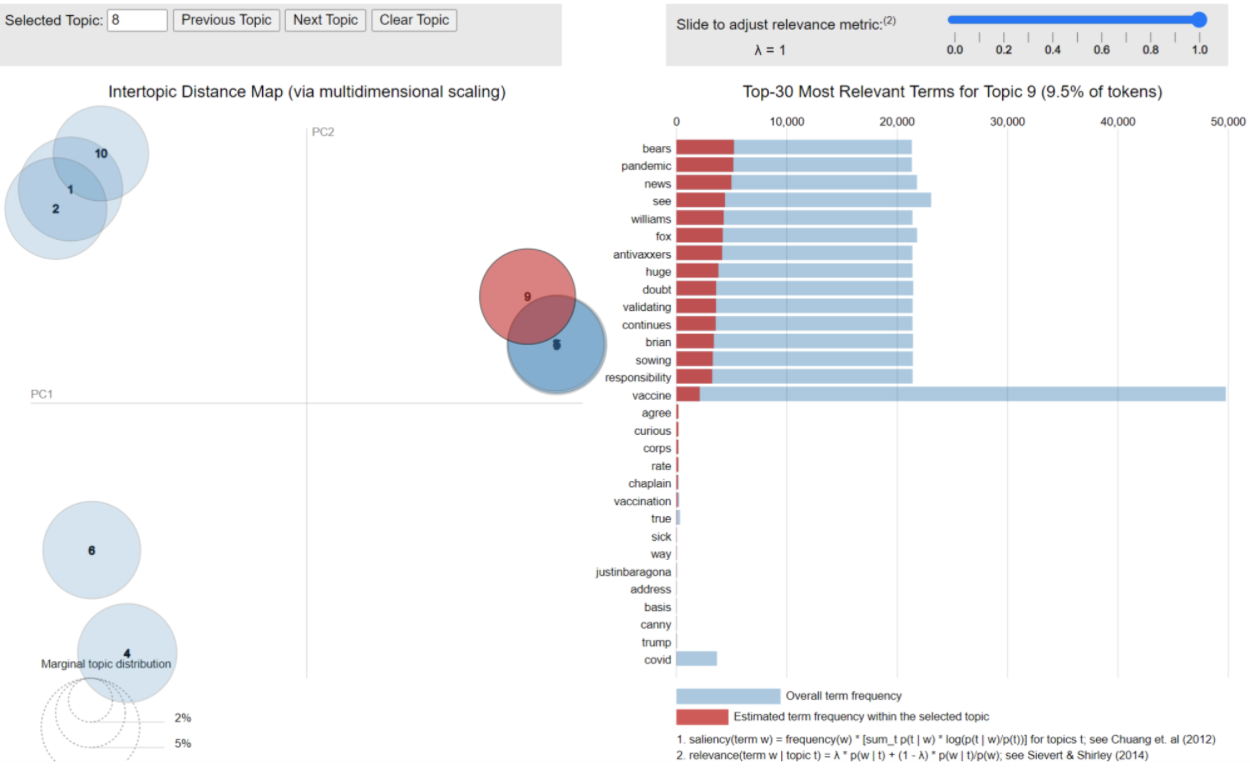

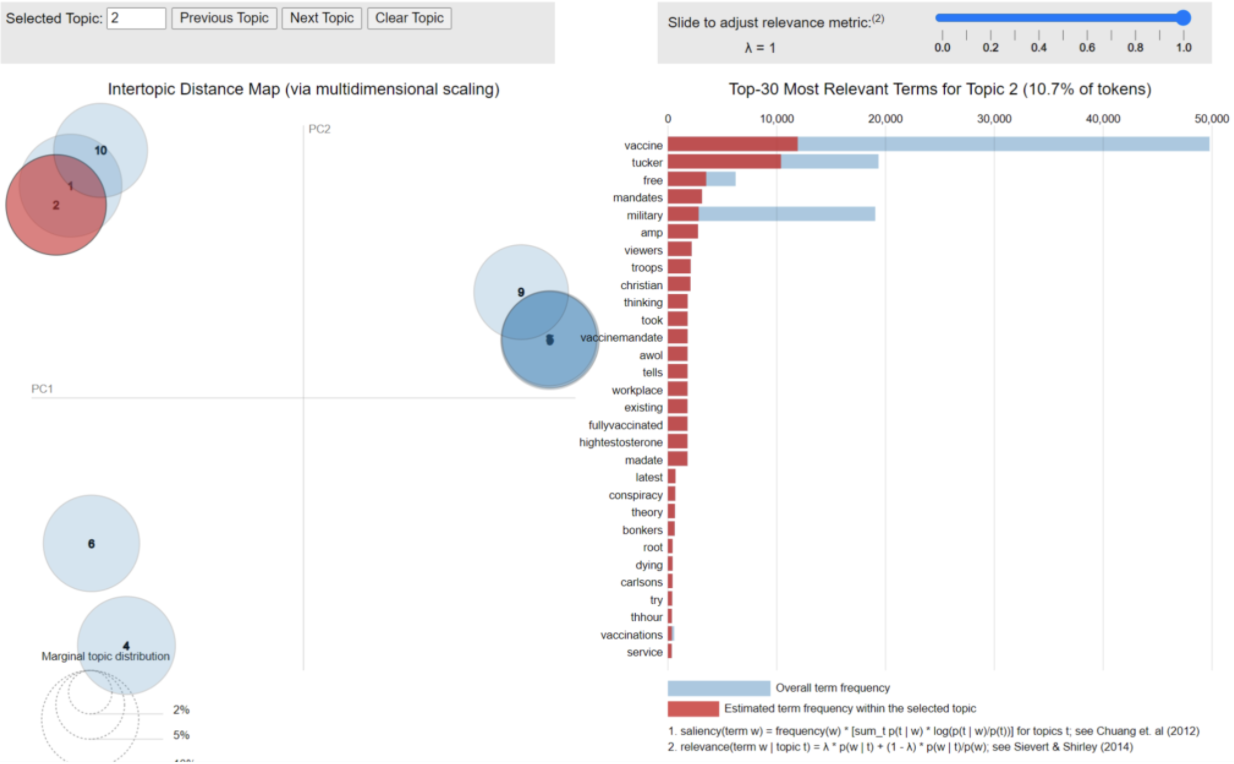

Pulling 15,000 random Tweets using key terms focusing on Tucker Carlson’s specific narrative targeting Department of Defense vaccine mandates, we find the Fox News commentator may have stretched the credulity of anti-vax misinformation beyond levels even social media can accept. The conversation was segmented along several sub-narratives. Tweets responding to Tucker Carlson’s assertions that the DoD vaccine mandate was designed to remove high testosterone men from the ranks, the conversation can be seen below.

The first conversational segment, consisting of 4 overlapping topics, is focused on a reaction tweet from MSNBC, arguing that Fox News bears “responsibility for sowing doubt about the vaccine, validating the anti-vaxxers as the pandemic continues.” The response is overwhelmingly positive towards the MSNBC statement, and condemns Fox News and Tucker Carlson.

The second conversational segment, consisting of three overlapping components, consolidates around tweets ridiculing Tucker Carlson for his “latest bonkers conspiracy theor[y]” along with discussion of workplace vaccine mandates.

Finally, the third segment of conversation, consisting of two related components, are tweets discussing Tucker Carlson’s previous claims related to COVID vaccines and disbelief in the Pentagon’s association with Satanism.

In assessing the online response to Tucker Carlson’s claims that the Department of Defense is mandating the COVID vaccine to “identify the sincere Christians in the ranks, the free thinkers, the men with high testosterone levels, and anybody else who doesn’t love Joe Biden and make them leave immediately”, we find that the Fox News personality inadvertently consolidated a reactionary conversation online. Instead of contributing to the spread and reach of COVID vaccine misinformation, Carlson’s narrative was met with incredulity, and a near unified condemnation of both Fox News and Carlson himself. Social media users rejected misinformation that the United States military is using vaccine mandates to target “high testosterone” members, and in propagating that narrative Tucker Carlson demonstrates that there is a limit to the believability of lies and conspiracy theories, even on the internet.

But Carlson is not the sole source of disinformation online. Credible or seemingly credible information sources (like expert opinion) are a much more serious threat to service members seeking information about the COVID vaccine than political efforts. Soldiers are doing their research, and it is imperative that DoD (and others) focus on getting more credible expert opinions into the marketplace of ideas so that those narratives can gain traction over these fantastical ones.

Expanding the Corporation for Public Broadcasting to Fund Local News

The Biden administration can respond to the rise in disinformation campaigns and ensure the long-term viability of American democracy by championing an expanded Corporation for Public Broadcasting to transform, revive, and create local public service newsrooms around the country.

Local newsrooms play key roles in a democracy: informing communities, helping set the agenda for local governments, grounding national debates in local context, and contributing to local economies; so it is deeply troubling that the market for local journalism is failing in the United States. Lack of access to credible, localized information makes it harder for communities to make decisions, hampers emergency response, and creates fertile ground for disinformation and conspiracy theories. There is significant, necessary activity in the academic, philanthropic, and journalism sectors to study and document the hollowing out of local news and sustain, revive, and transform the landscape for local journalism. But the scope of the problem is too big to be solely addressed privately. Maintaining local journalism requires treating it as a public good, with the scale of investment that the federal government is best positioned to provide.

The United States has shown that it can meet the opportunities and challenges of a changing information landscape. In the 1960s, Congress established the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), creating a successful and valuable public media system in response to the growth of widely available corporate radio and TV. But CPB’s purview hasn’t changed much since then. Given the challenges of today’s information landscape, it is time to reimagine and grow CPB.

The Biden administration should work with Congress to revitalize local journalism in the United States by:

- Passing legislation to evolve the CPB into an expanded Corporation for Public Media. CPB’s current mandate is to fund and support broadcast public media. An expanded Corporation for Public Media would continue to support broadcast public media while additionally supporting local, nonprofit, public-service-oriented outlets delivering informational content to meet community needs through digital, print, or other mediums.

- Doubling CPB’s annual federal budget allocation, from $445 to $890 million, to fund greater investment in local news and digital innovation. The local news landscape is the subject of significant interest from philanthropies, industry, communities, and individuals. Increased federal funding for local, nonprofit, and public-service-oriented news outlets could stimulate follow-on investment from outside of government.

Challenge and Opportunity

Information systems are fracturing and shifting in the United States and globally. Over the past 20 years, the Internet disrupted news business models and the national news industry consolidated; both shifts have contributed to the reduction of local news coverage. American newsrooms have lost almost a quarter of their staff since 2008. Half of all U.S. counties have only one newspaper or information equivalent, and many counties have no local information source. The media advocacy group Free Press estimates that the national “reporting gap”, which they define as the wages of the roughly 15,000 reporting roles lost since the peak of journalism in 2005, stands at roughly $1 billion a year.

The depletion of reputable local newsrooms creates an information landscape ripe for manipulation. In particular, the shrinking of local newsrooms can exacerbate the risk of “data voids”, when good information is not available via online search and instead users find “falsehoods, misinformation, or disinformation”. In 2019, the Tow Center at the Columbia Journalism School documented 450 websites masquerading as local news outlets, with titles like the East Michigan News, Hickory Sun, and Grand Canyon Times But instead of publishing genuine journalism, these sites were distributing algorithmically generated, hyperpartisan, locally tailored disinformation. The growing popularity of social media as news sources or conduits to news sources — more than half of American adults today get at least some news from social media — compounds the problem by making it easier for disinformation to spread.

Studies show that the erosion of local journalism has negative impacts on local governance and democracy, including increased voter polarization, decreased accountability for elected officials to their communities, and decreased competition in local elections. Disinformation narratives that take root in the information vacuum left behind when local news outlets fold often disproportionately target and impact marginalized people and people of color. Erosion of local journalism also threatens public safety. Without access to credible and timely local reporting, communities are at greater risk during emergencies and natural disasters. In the fall of 2020, for instance, emergency response to wildfires threatening communities in Oregon was hampered by the spread of inaccurate information on social media. These problems will only become more pronounced if the market for local journalism continues to shrink.

These are urgent challenges and the enormity of them can make them feel intractable. Fortunately, history presents a path forward. By the 1960s, with the rise of widely available corporate TV and radio, the national information landscape had changed dramatically. At the time, the federal government recognized the need to reduce the potential harms and meet the opportunities that these information systems presented. In particular, then-Chair of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Newton Minow called for more educational and public-interest programming, which the private TV market wasn’t producing.18 Congress responded by passing the Public Broadcasting Act in 1967, creating the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB). CPB is a private nonprofit responsible for funding public radio and television stations and public-interest programming. (Critically, CPB itself does not produce content.) CPB has a mandate to champion diversity and excellence in programming, serve all American communities, ensure local ownership and independent operation of stations, and shield stations from the possibility of political interference. Soon after its creation, CPB established the independent entities of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR).

CPB, PBS, NPR, and local affiliate stations collectively developed into the national public media system we know today. Public media is explicitly designed to fill gaps not addressed by the private market in educational, youth, arts, current events, and local news programming, and to serve all communities, including populations frequently overlooked by the private sector. While not perfect, CPB has largely succeeded in both objectives when it comes to broadcast media. CPB supports1 about 1,500 public television and radio broadcasters, many of which produce and distribute local news in addition to national news. CPB funds much-needed regional collaborations that have allowed public broadcasters to combine resources, increase reporting capacity, and cover relevant regional and localized topics, like the opioid crisis in Appalachia and across the Midwest. CPB also provides critical — though, currently too little — funding to broadcast public media for historically underserved communities, including Black, Hispanic, and Native communities.

Public media and CPB’s funding and support is a consistent bright spot for the struggling journalism industry.25 More than 2,000 American newspapers closed in the past 15 years, but NPR affiliates added 1,000 local part- and full-time journalist positions from 2011–2018 (though these data are pre-pandemic).26 Trust in public media like PBS remains high compared to other institutions; and local news is more trusted than national news.27,28 There is clear potential for CPB to revive and transform the local news landscape: it can help to develop community trust, strengthen democratic values, and defend against disinformation at a time when all three outcomes are critical.

Unfortunately, the rapid decline of local journalism nationwide has created information gaps that CPB — an institution that has remained largely unchanged since its founding more than 50 years ago — does not have the capacity to fill. Because its public service mandate still applies only to broadcasters, CPB is unable to fund stand-alone digital news sites. The result is a dearth of public-interest newsrooms with the skills and infrastructure to connect with their audiences online and provide good journalism without a paywall. CPB also simply lacks sufficient funding to rebuild local journalism at the pace and scope needed. Far too many people in the United States — especially members of rural and historically underserved communities — live in a “news desert”, without access to any credible local journalism at all.2

The time is ripe to reimagine and expand CPB. Congress has recently demonstrated bipartisan willingness to invest in local journalism and public media. Both major COVID-19 relief packages included supplemental funding for CPB. The American Rescue Act and the CARES Act provided $250 million and $75 million, respectively, in emergency stabilization funds for public media. Funds were prioritized for small, rural, and minority-oriented public-media stations.30 As part of the American Rescue Plan, smaller news outlets were newly and specifically made eligible for relief funds—a measure that built on the Local News and Emergency Information Act of 2020 previously introduced by Senator Maria Cantwell (D-WA) and Representative David Cicilline (D-RI) and supported by a bipartisan group. Numerous additional bills have been proposed to address specific pieces of the local news crisis. Most recently, Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO), Amy Klobuchar (D-MI), and Brian Schatz (D-HI), along with Representative Marc Veasy (DTX) reintroduced the Future of Local News Commission Act, calling for a commission “to study the state of local journalism and offer recommendations to Congress on the actions it can take to support local news organizations”.

These legislative efforts recognize that while inspirational work to revitalize local news is being done across sectors, only the federal government can bring the level of scale, ambition, and funding needed to adequately address the challenges laid out above. Reimagining and expanding CPB into an institution capable of bolstering the local news ecosystem is necessary and possible; yet it will not be easy and would bring risks. The United States is amid a politically uncertain, difficult, and even violent time, with a rapid, continued fracturing of shared understanding. Given how the public media system has come under attack in the “culture wars” over the decades, many champions of public media are understandably wary of considering any changes to the CPB and public media institutions and initiatives. But we cannot afford to continue avoiding the issue. Our country needs a robust network of local public media outlets as part of a comprehensive strategy to decrease blind partisanship and focus national dialogues on facts. Policymakers should be willing to go to bat to expand and modernize the vision of a national public media system first laid out more than fifty years ago.

Plan of Action

The Biden administration should work with Congress to reimagine CPB as the Corporation for Public Media: an institution with the expanded funding and purview needed to meet the information challenges of today, combat the rise of disinformation, and strengthen community ties and democratic values at the local level. Recommended steps towards this vision are detailed below.

Recommendation 1. Expand CPB’s Purview to Support and Fund Local, Nonprofit, Public Service Newsrooms.

Congress should pass legislation to reestablish the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) as the Corporation for Public Media (CPM), expanding the Corporation’s purview from solely supporting broadcast outlets to additionally supporting local, nonprofit newsrooms of all types (digital, print, broadcast).

The expanded CPM would retain all elements of the CPB’s mandate, including “ensuring universal access to non-commercial, high-quality content and telecommunications services that are commercial free and free of charge,” with a particular emphasis on ensuring access in rural, small town, and urban communities across the country. Additionally, CPB “strives to support diverse programs and services that inform, educate, enlighten and enrich the public”, especially addressing the needs of underserved audiences, children, and minorities.

Legislation expanding the CPB into the CPM must include criteria that local, nonprofit, public-service newsrooms would need to meet to be considered “public media” and become eligible for federal funding and support. Broadly, local, nonprofit newsrooms should mean nonprofit or noncommercial newsrooms that cover a region, state, county, city, neighborhood, or specific community; it would not include individual reporters, bloggers, documentarians, etc. Currently, CPB relies on FCC broadcasting licenses to determine which stations might be eligible to be considered public broadcasters. The Public Broadcasting Act lays out additional eligibility requirements, including an active community advisory board and regularly filed reports on station activities and spending. Congress should build on these existing requirements when developing eligibility criteria for CPM funding and support.

In designing eligibility criteria, Congress could also draw inspiration from the nonprofit Civic Information Consortium (CIC) being piloted in New Jersey. The CIC is a partnership between higher education institutions and newsrooms in the state to strengthen local news coverage and civic engagement, seeded with an initial $500,000 in funding. The CPM could require that to be eligible for CPM funding, nonprofit public-service newsrooms must partner with local, accredited universities.39 Requiring that an established external institution be involved in local news endeavors selected for funding would (i) decrease risks of investing in new and untested newsrooms, (ii) leverage federal investment by bringing external capabilities to bear, and (iii) increase the impact of federal funding by creating job training and development opportunities for local students and workers. Though, of course, this model also brings its own risks, potentially putting unwelcome pressure on universities to act as public media and journalism gatekeepers.

An expanded CPM would financially support broadcast, digital, and print outlets at the local and national levels. Once eligibility criteria are established, clear procedures would need to be established for funding allocation and prioritization (see next section for recommended prioritizations). For instance, procedures should explain how factors such as demonstrated need and community referrals will factor into funding decisions. Procedures should also ensure that funding is prioritized towards local newsrooms that serve communities in “news deserts”, or places at risk of becoming news deserts, and historically underserved communities, including Black, Hispanic, Native, and rural communities.

Congress could consider tasking the proposed Future of Local News Act commission with digging deeper into how CPB could be evolved into the CPM in a way that best positions it to address the disinformation and local news crises. The commission could also advise on how to avoid two key risks associated with such an evolution. The first is the perpetual risk of government interference in public media, which CPB’s institutional design and norms have historically guarded against. (For example, there are no content or viewpoint restrictions on public media today—and there should not be in the future.) Second, expanding CPB’s mandate to include broadly funding local, nonprofit newsrooms would create a new risk that disinformation or propaganda sites, operating without journalistic practices, could masquerade as genuine news sites to apply for CPM funding. It will be critical to design against both of these risks. One of the most important factors in CPB’s success is its ethos of public service and the resulting positive norms; these norms and its institutional design are a large part of what makes CPB a good institutional candidate to expand. In designing the new CPM, these norms should be intentionally drawn on and renewed for the digital age.

Numerous digital outlets would likely meet reasonable eligibility criteria. One recent highlight in the journalism landscape is the emergence of many nonprofit digital outlets, including almost 300 affiliated with the Institute for Nonprofit News. (These sites certainly have not made up for the massive numbers of journalism jobs and outlets lost over the past two decades.) There has also been an increase in public media mergers, where previously for-profit digital sites have merged with public media broadcasters to create mixed-media nonprofit journalistic entities. As part of legislation expanding the CPB into the CPM, Congress should make it easier for public media mergers to take place and easier for for-profit newspapers and sites to transition to nonprofit status, as the Rebuild Local News Coalition has proposed.

Recommendation 2. Double CPB’s Yearly Appropriation from $445 to $890 million.

Whether or not CPB is evolved into CPM, Congress should (i) double (at minimum) CPB’s next yearly appropriation from $445 to $890 million, and (ii) appropriate CPB’s funding for the next ten years up front. The first action is needed to give CPB the resources it needs to respond to the local news and disinformation crises at the necessary scale, and the second is needed to ensure that local newsrooms are funded over a time horizon long enough to establish themselves, develop relationships with their communities, and attract external revenue streams (e.g., through philanthropy, pledge drives, or other models). The CPB’s current appropriation is sufficient to fund some percentage of station operational and programming costs at roughly 1,500 stations nationwide. This is not enough. Given that Free Press estimates the national “reporting gap” as roughly $1 billion a year, CPB’s annual budget appropriation needs to be at least doubled. Such increased funding would dramatically improve the local news and public media landscape, allowing newsrooms to increase local coverage and pay for the digital infrastructure needed to better meet audiences where they are—online. The budget increase could be made part of the infrastructure package under Congressional negotiation, funded by the Biden administration’s proposed corporate tax increases, or separately funded through corporate tax increases on the technology sector.

The additional appropriation should be allocated in two streams. The first funding stream (75% of the additional appropriation, or $667.5 million) should specifically support local public-service journalism. If Free Press’s estimates of the reporting gap are accurate, this stream might be able to recover 75% of the journalism jobs (somewhere in the range of 10,000 to 11,000 jobs) lost since the industry’s decline began in earnest—a huge and necessary increase in coverage. Initial priority for this funding should go to local journalism outlets in communities that have already become “news deserts”. Secondary priority should go to outlets in communities that are at risk of becoming news deserts and in communities that have been historically underserved by media, including Black, Hispanic, Native, and rural communities. Larger, well-funded public media stations and outlets should still receive some funding from this stream (particularly given their role in surfacing local issues to national audiences), but with less of a priority focus. This funding stream should be distributed through a structured formula — similar to CPB’s funding formulas for public broadcasting stations — that ensures these priorities, protects news coverage from government interference, and ensures high-quality news.

The second funding stream (25% of additional appropriation, or $222.5 million) should support digital innovation for newsrooms. This funding stream would help local, nonprofit newsrooms build the infrastructure needed to thrive in the digital age. Public media aims to be accessible and meet audiences where they are. Today, that is often online. Though the digital news space is dominated by social media and large tech companies, public media broadcasters are figuring out how to deliver credible, locally relevant reporting in digital formats. NPR, for instance, has successfully digitally innovated with platforms like NPR One. But more needs to be done to expand the digital presence of public media. CPB should structure this funding stream as a prize challenge or other competitive funding model to encourage further digital innovation.

Finally, the overall additional appropriation should be used as an opportunity to encourage follow-on investment in local news, by philanthropies, individuals, and the private sector. There is significant interest across the board in revitalizing American local news. The attention that comes with a centralized, federally sponsored effort to reimagine and expand local public media can help drive additional resources and innovation to places where they are most needed. For instance, philanthropies might offer private matches for government investment in local news. Such an initiative could draw inspiration from the existing and successful NewsMatch program, a funding campaign where individuals donate to a nonprofit newsroom and their donation is matched by funders and companies.

Conclusion

Local news is foundational to democracy and the flourishing of communities. Yet with the rise of the Internet and social media companies, the market for local news is failing. There is significant activity in the journalistic, philanthropic, and academic sectors to sustain, revive, and transform the local news landscape. But these efforts can’t succeed alone. Maintaining local journalism as a public good requires the scale of investment that only the federal government can bring.

In 1967, our nation rose to meet a different moment of disruption in the information environment, creating public media broadcasting through the Public Broadcasting Act. Today, there is a similar need for the Biden administration, Congress, and CPB to reimagine public media for the digital age. They should champion an expanded Corporation for Public Media to better meet communities’ information needs; counter the rising tide of disinformation; and transform, revive, and create local, public-service newsrooms around the country.

Big Tech CEOs questioned about fighting disinformation with AI by the House Energy and Commerce Committee

The amount of content posted on social media platforms is increasing at a dramatic rate, and so is the portion of that content that is false or misleading. For instance, users upload over 500 hours of video to YouTube every minute. While much of this content is innocuous, some content spreads harmful disinformation, and addressing the spread of false or misleading information has been a substantial challenge for social media companies. The spread of disinformation, as well as misinformation, on social media platforms was highlighted during a March 25 hearing in the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Members questioned the CEOs of Facebook, Twitter, and Google on their roles in stopping the spread of false information, much of which contributed to the worsening of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol.

Artificial intelligence as a solution for disinformation

False or misleading posts on social media spread quickly and can significantly affect people’s views. MIT Sloan researchers found that false information was 70% more likely to be retweeted on Twitter than facts; false information also reached its first 1,500 people six times faster. Furthermore, researchers at Rand discovered that a constant onslaught of false information can even skew people’s political opinions. Specifically, false information exacerbates the views of people in closed or insular social media circles because they receive only a partial picture of how other people feel about specific political issues.

Traditionally, social media companies have relied on human reviewers to find harmful posts. Facebook alone employs over 30,000 reviewers. According to a report published by New York University, Google employs around 10,000 content reviewers for YouTube and its subsidiaries, and Twitter employs around 1,500. However, the human review of content is time-consuming, and, in many instances, extremely traumatic for these reviewers. These Big Tech companies are now developing artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms to automate much of this work.

At Facebook, the algorithms rely on tens of millions of user-submitted reports about potentially harmful content. This dataset is then used to train the algorithms to identify which types of posts are actually harmful. The content is separated into seven different categories: nudity, graphic violence, terrorism, hate speech, fake accounts, spam, and suicide prevention. In the past few years, much of their effort was dedicated to identifying fake accounts that would likely be used for malignant purposes, such as election disinformation. Facebook is also using its AI algorithms to identify fraudulent news outlets publishing fake news and to help its reviewers remove spam accounts.

Google has developed algorithms that skim all search results and rank them based on quality and relevance to a user’s search terms. When the algorithms identify articles promoting misinformation, those articles are ranked lower in the search results and are therefore more difficult to find. For YouTube, the company developed algorithms to screen new content and then demonetized any content related to COVID-19. Videos related to the pandemic are unable to earn any revenue from ads, ideally dissuading those attempting to profit from COVID-19 scams involving the posting of misleading content. YouTube has also redesigned its recommendation algorithms to show users authoritative sources of information about the COVID-19 pandemic and steer them away from disinformation or misinformation.

Twitter is also using AI to detect harmful tweets and remove them as quickly as possible. In 2019, the social media site reported that its algorithms removed 43% of the total number of tweets that were in violation of their content policies. That same year, Twitter purchased a UK-based AI startup to help counter disinformation spreading on its platform. Its algorithms are designed to quickly identify content that can pose a direct risk to the health or well-being of others, and prioritizes that content for review by human moderators. These moderators can then evaluate the potentially problematic tweets to make a final determination as to whether the content is truly harmful.

The limitations of using AI

While AI can be a useful tool in combating disinformation on social media, it can have significant drawbacks. One of the biggest problems is that AI algorithms have not achieved a high enough proficiency in understanding language and have difficulty determining what a specific post actually means. For example, AI systems like Apple’s Siri can follow simple commands or answer straightforward questions, but cannot hold conversations with a person. During the hearing, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey and Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg discussed this point, describing how it is difficult for AI algorithms to parse social media posts denouncing harmful ideas from those that are endorsing them. Another problem with AI is that the decision-making processes for these algorithms can be highly opaque. In other words, the computers are unable to explain why or how they have made their decisions. Lastly, AI algorithms are only as smart as the data on which they are trained. Imperfect or biased data will then lead to ineffective algorithms and flawed decisions. These biases can come from many sources and can be difficult for AI scientists to identify.

More needs to be done

False and misleading posts on social media about the COVID-19 pandemic and the results of the 2020 presidential election have led to significant harm in the real world. In order to fully leverage AI to help mitigate the spread of disinformation and misinformation, much more research needs to be done. As we monitor Congressional activity focused on countering disinformation, we encourage the CSPI community to serve as a resource for federal officials on this topic.

Policy proposals about countering false information from FAS’ Day One Project

A National Strategy to Counter COVID-19 Misinformation – Amir Bagherpour and Ali Nouri

Creating a COVID-19 Commission on Public Health Misinformation – Blair Levin and Ellen Goodman

Combating Digital Disinformation: Resisting Foreign Influence Operations through Federal Policy – Dipayan Ghosh

Digital Citizenship: A National Imperative to Protect and Reinvigorate our Democracy – Joseph South and Ji Soo Song

Spanish-language vaccine news stories hosting malware disseminated via URL shorteners

Key Highlights

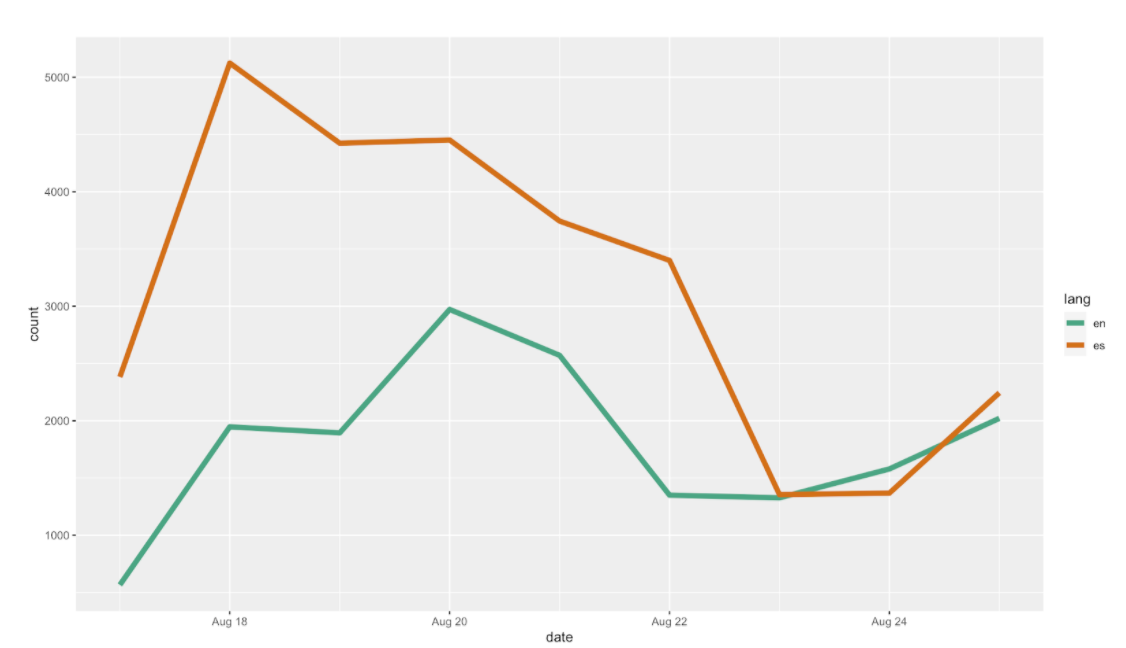

- Compared to our September report, this update discovered a much larger Spanish-language news network of COVID-19 vaccine stories with embedded malware files for all major vaccines. Now, through link-shortening services such as bit.ly, a third-party has disseminated vaccine-related malware across Latin America.

- The news of a possible adverse reaction to the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine triggered a wave of social media activity. The volume of shares, mentions, and tweets formed an ideal entry-point for malicious actors to potentially distribute malware to hundreds of thousands of unwitting readers. Embedded malware may provide opportunities for malicious actors to manipulate web traffic in order to amplify narratives that cast doubt on the efficacy of particular vaccines. These efforts have since been operationalized in at least five Latin American countries to undermine trust in the Oxford-AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines.

- An initial analysis of 88,555 Spanish-language tweets found Russia’s mundo.sputniknews.com to be the epicenter of these malware files, with eight additional infected files detected since our previous analysis. A second set of scans identified more instances of malware on the domain compared to the initial 17 scans in a previous report.

- We discovered evidence of link-shortening services being used to reroute links for stories on Latin American news outlets to malware-infected web pages. Link-shortening reduces the character count and makes it easier to click, but it also obscures the destination URL. 7,074 shortened bit.ly links were detected. This report found half of all randomly sampled bit.ly links are associated with infected sites.

Malware hosted within popular news stories about COVID-19 vaccine trials

On September 18, 2020, FAS released a report locating a network of malware files related to the COVID-19 vaccine development on the Spanish-language Sputnik News link mundo.sputniknews.com. The report uncovered 53 websites infected with malware that were spread throughout Twitter, after allegations of adverse reactions led to a pause in the Oxford-AstraZeneca (AZD1222) vaccine trial.

Whereas our first report collected 136,597 tweets and was only limited to the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, this update presents a collection of 500,166 tweets from Nov. 18 to Dec. 1 containing key terms “AstraZeneca”, “Sputnik V”, “Moderna”, and “Pfizer”. From that total, 88,555 tweets written in Spanish were analyzed for potential malware infections.

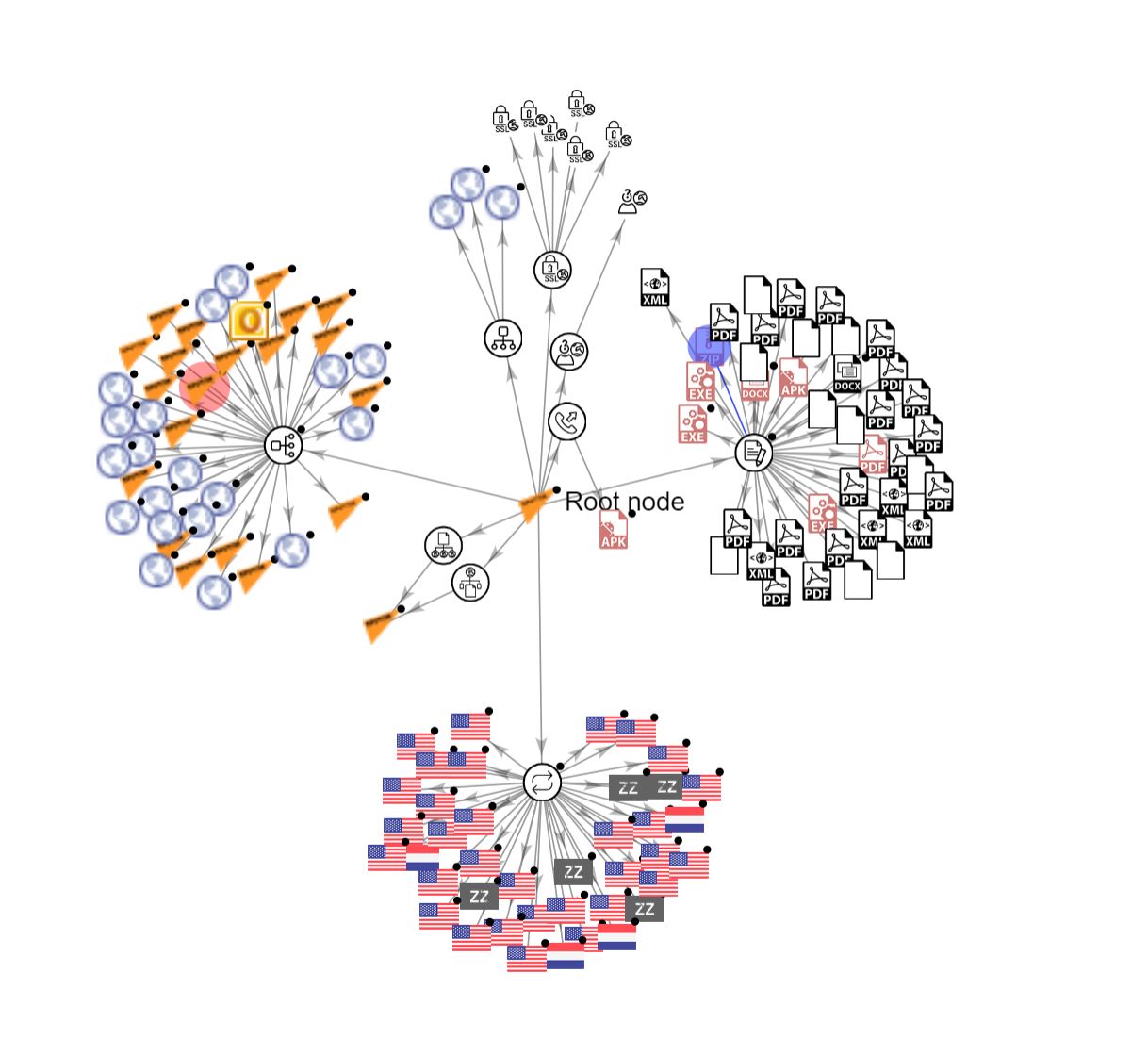

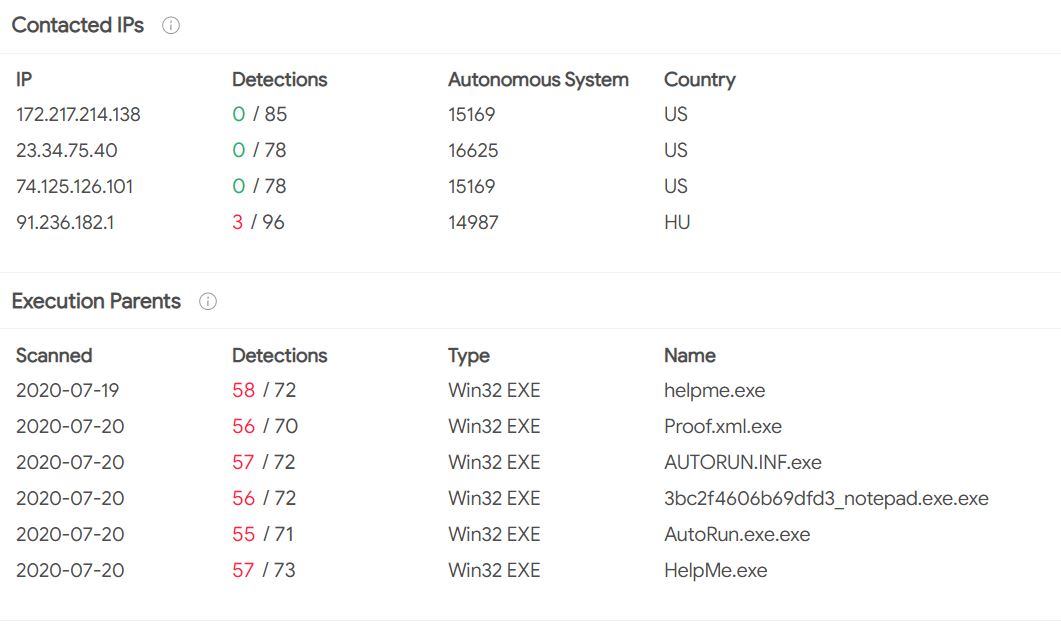

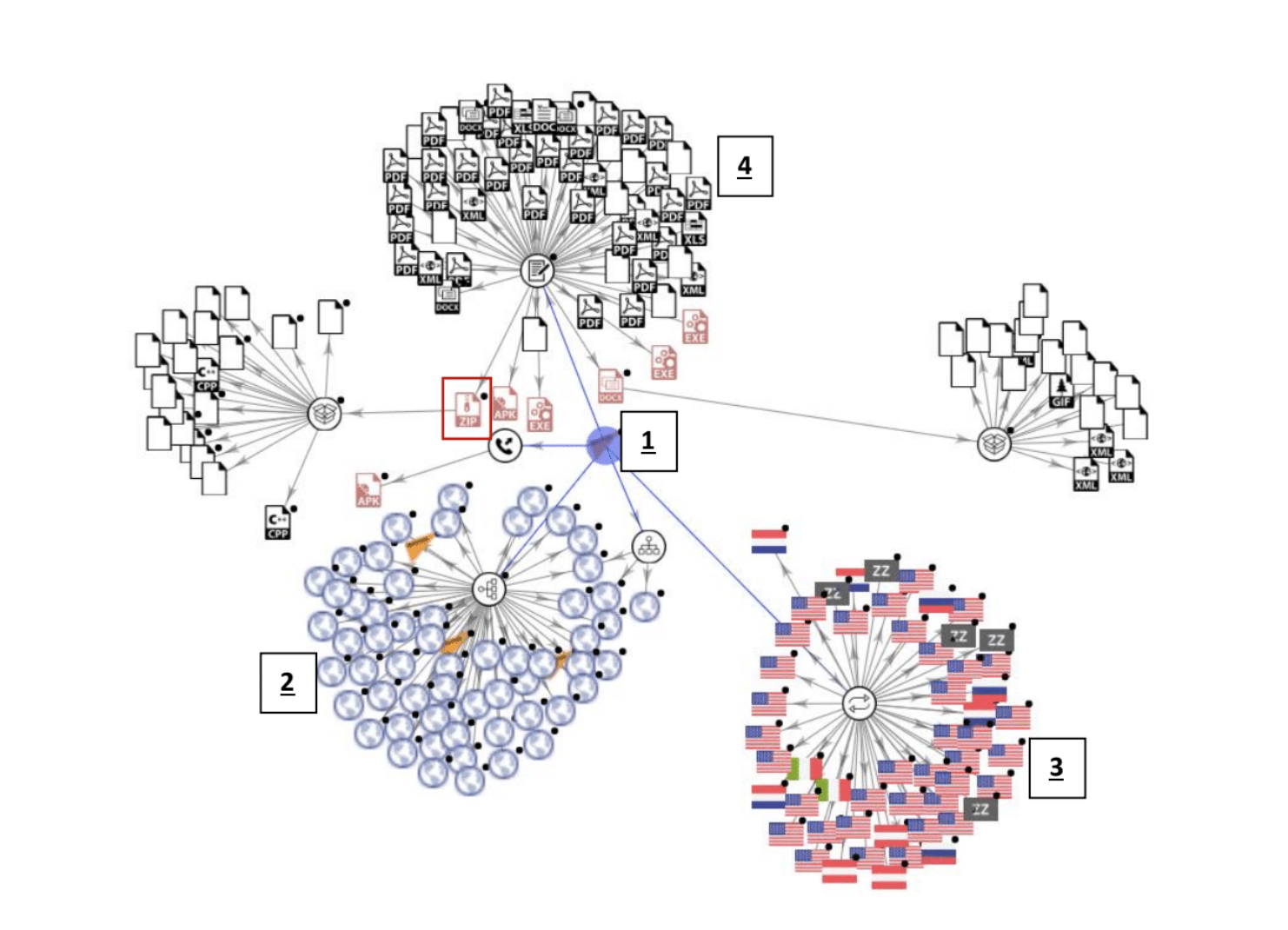

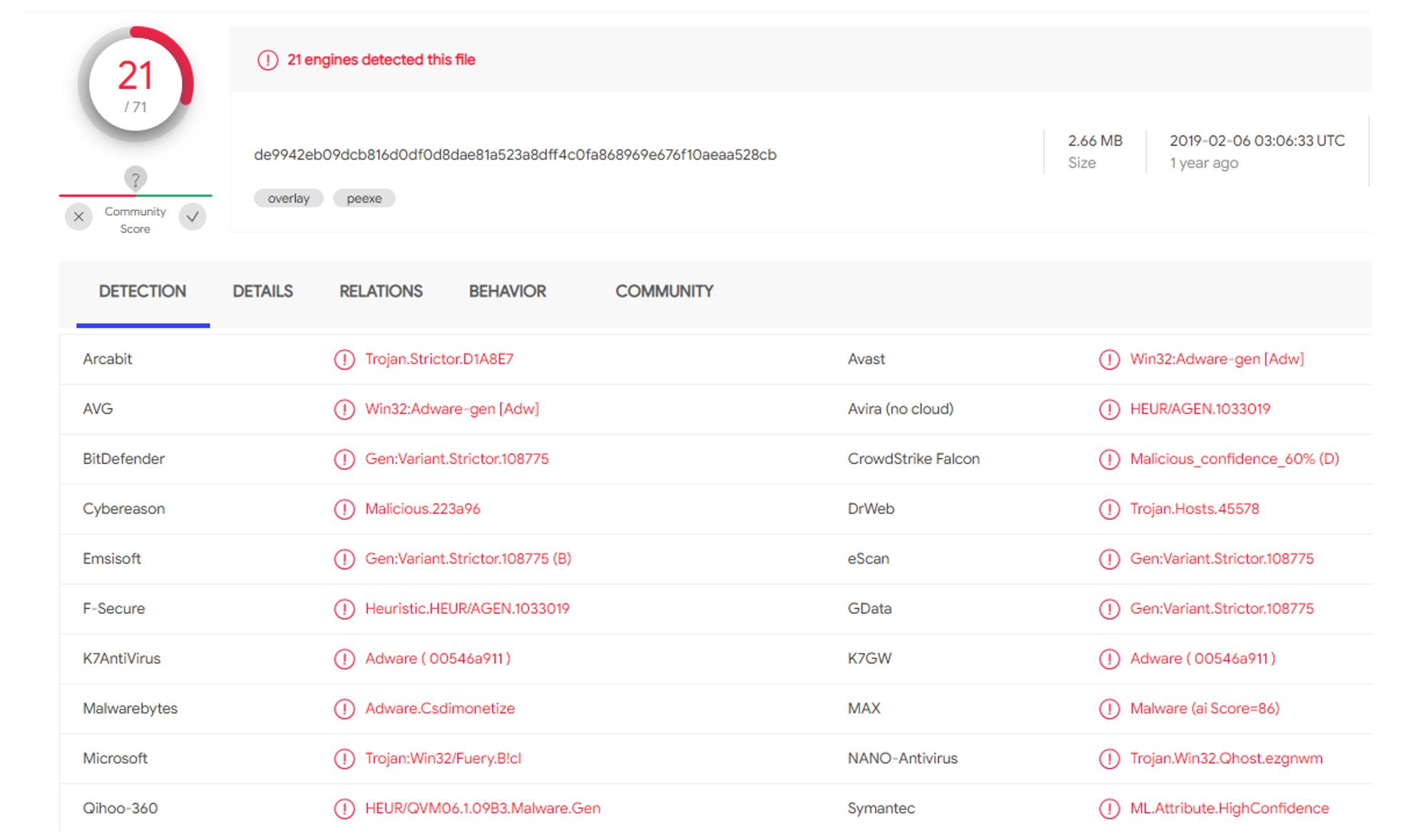

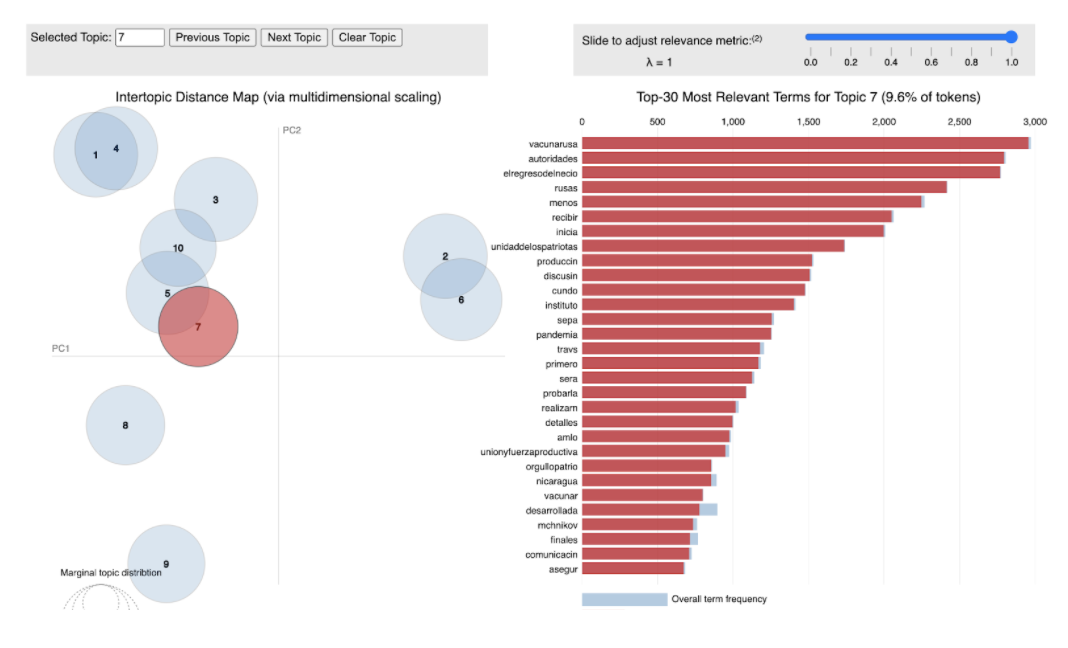

Our analysis determines that infections on the mundo.sputniknews.com domain are continuing. Eight separate files were discovered, with 52 unique scans detecting various malware — up from the 17 scans in the initial report (see Figure 1).

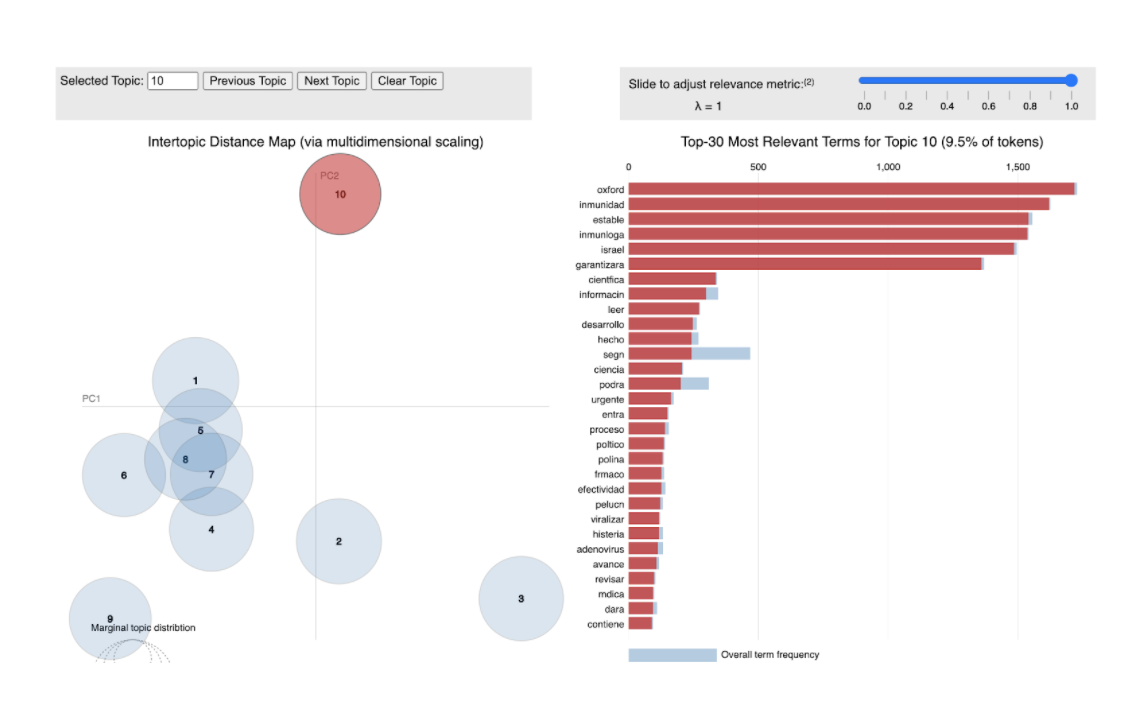

Many of the published stories contain information about possible complications or lean sceptically towards vaccine efficacy. The top translated story features the title “The detail that can complicate Moderna and Pfizer vaccines” (see Figure 2).

One possible explanation behind the use of malware is that perpetrators can identify and track an audience interested in the state of COVID-19 vaccines. From there, micro-targeting on the interested group could artificially tilt the conversation regarding certain vaccines favorably. Such a strategy works well with these sites, which are already promoting material questioning Western-based vaccines.

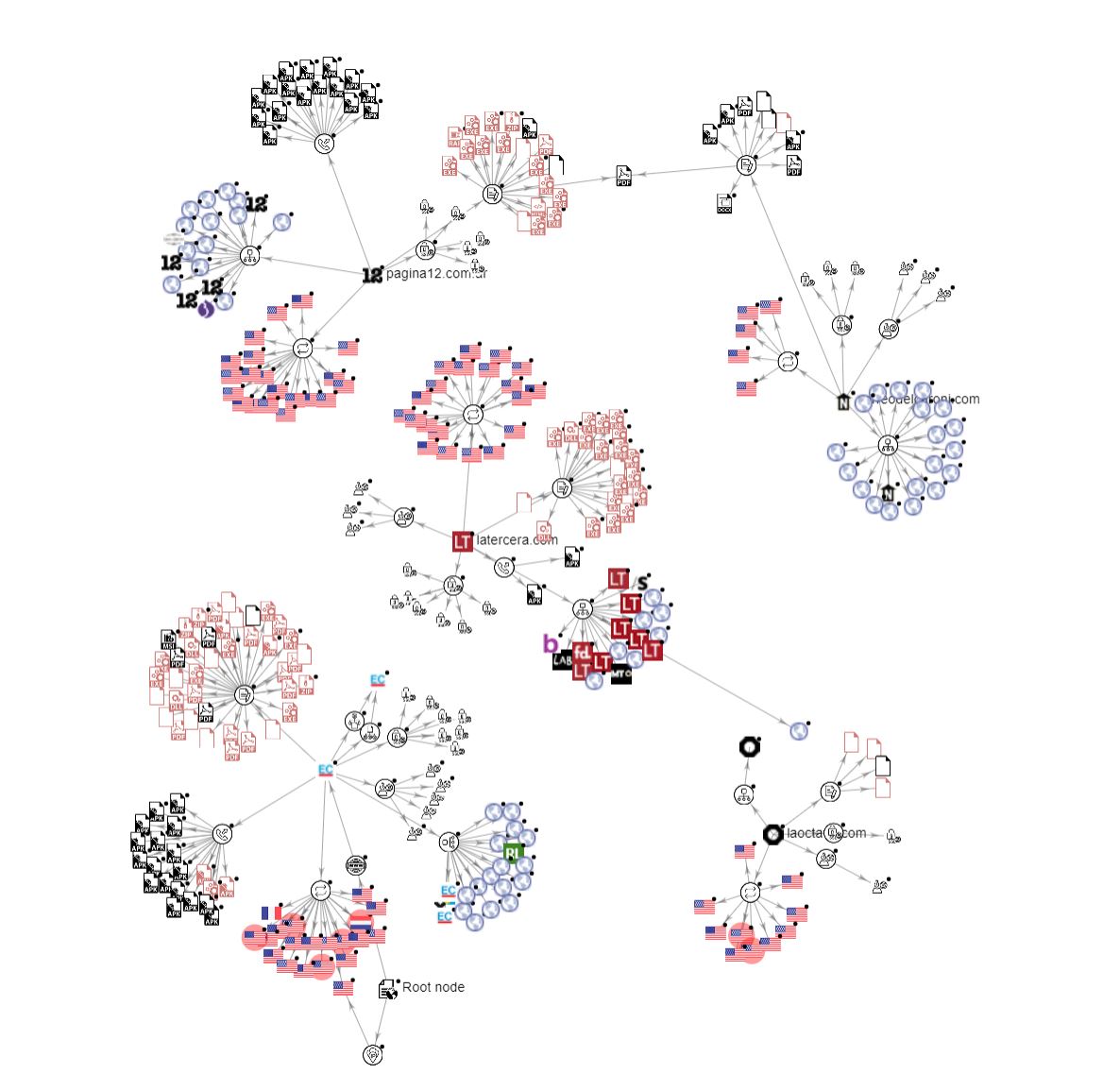

Additionally, within the Spanish-language Twitter ecosystem, 7,074 shortened bit.ly were discovered related to COVID-19 vaccines. The use of link shortening is a new discovery and a worrisome one. Not only does it enable additional messaging on Twitter by reducing URL characters, link-shortening can also obscure the final destination of the URL. The native Spanish-language news network suffering malware infection is structurally different from the Sputnik Mundo infection. Unlike the Sputnik Mundo domain, the bit.ly links routing to Latin American news outlets are doing so indirectly, first connecting to an IP that will refer the traffic to the news story URL but also hosts malware. This process has the potential to indirectly spread malware by clicking on bit.ly-linked embedded within Tweets.

Of the bit.ly links shared more than 25 times, our analysis randomly selected ten. Half were infected and half were clean links. Infected domains included: an Argentine news site (www.pagina12.com.ar), an eastern Venezuelan newspaper (www.correodelcaroni.com), a Chilean news outlet (https://www.latercera.com), a Peruvian news outlet (https://Elcomercio.com), and a Mexican news outlet (https://www.laoctava.com).

The typology of malware within the infected network was diverse. Our results indicate 77 unique pieces of malware, including adware-based malware, malware that accesses Windows registry keys on both 32- and 64-bit PC systems, APK exploits, digital coin miners, worms, and others. Our analysis indicates that the malware is designed to monitor personal behavior on users’ devices.

The malware network is robust but not highly interconnected (see Figure 3).

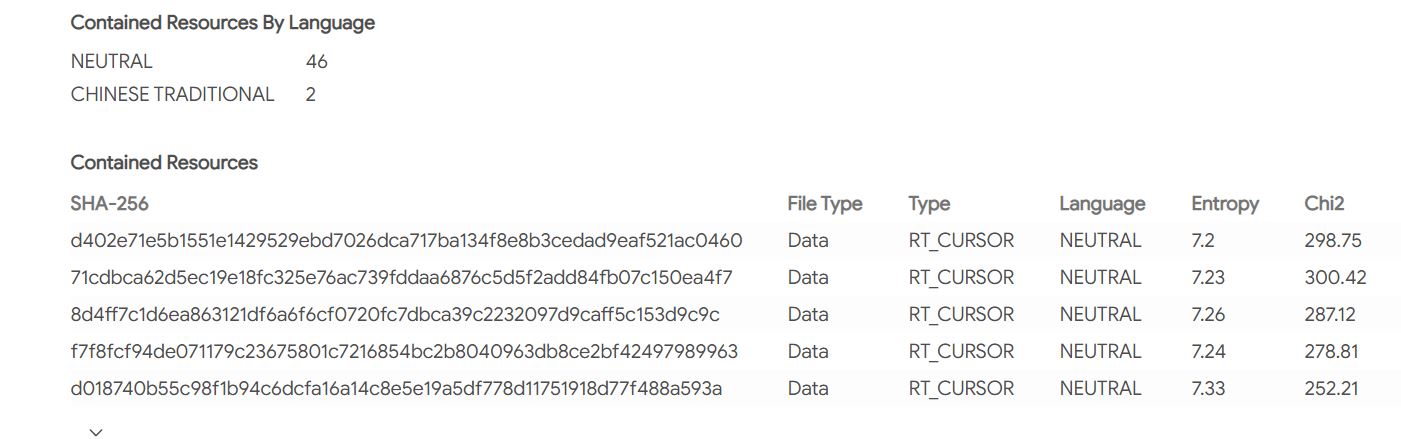

Examination of the malware contained within this network revealed interesting attribution information. While much of the specific malware (e.g. MD5 hash: 1aa1bb71c250ed857c20406fff0f802c, found on the Chilean news outlet https://www.latercera.com) has neutral encoding standards, two language resources in the file are registered as “Chinese Traditional” (see Figure 4).

As manipulation of language resources in coding is common, the presence of Chinese Traditional characters flagged in the malware’s code suggests the originators of the malware may be trying to confuse malware-detection software.

However, our analysis identified this malware’s IP address as located in Hungary, while its holding organization is in Amsterdam (see Figure 5). This IP address was also linked to the Undernet (https://www.undernet.org/), one of the largest Internet chat domains with over 17,444 users in 6,621 channels and a known source of malware origination. Again, this is but one malware on one Chilean news outlet pulled for closer inspection. Collectively, our findings demonstrate the networked production and distribution of malware in the COVID-19 vaccine conversation.

The malware network is large and presents a clear threat vector for the delivery of payload on vaccine stories. Vaccine malware-disinformation has spread beyond Russia’s Sputnik Mundo network and towards a series of other domains in Argentina, Venezuela, Chile, Peru, and Mexico. This is particularly alarming considering that aggressive conspiracy theories advanced by the Kremlin in Latin America have already tilted the region’s governments towards the use of the Sputnik V vaccine. Indeed, Russia is supplying Mexico with 32 million doses of Sputnik V. Venezuela and Argentina are set to purchase 10 million and 25 million doses respectively, while Peru is currently in negotiations to purchase the Sputnik V.

With a malware-curated audience, it will become significantly easier to pair the supply of Sputnik V with targeted information to support its use and delegitimize Western vaccines.

Considering that COVID-19 vaccine efforts are arguably the most important news topic on any given day, the spike in social media activity from the AstraZeneca COVID-19 clinical trial pause marked a key entry point for malware-disinformation. Since September, however, the network has largely permeated throughout Spanish-language Twitter — as did Sputnik V throughout Latin America.

With the explosion of reporting on the pandemic and vaccines, it is difficult to know what sites are safe and which are dangerous. This risk is magnified for less-savvy Internet users, who may not even consider the vulnerability of malware. Unfortunately, it is difficult to say the number of individuals that were infected from the malware discovered. Even one person clicking the wrong link could have a disastrous effect, as the malware siphons sensitive information from credit card numbers to confidential information appearing on a user’s screen.

Most worrisome is that the malware technique could create a library of users interested in vaccine stories who could be subsequently targeted. If used for micro-targeting, the library would become an effective audience to target with more vaccine misinformation.

Methodology

We performed a combination of social network analysis, anomalous behavior discovery and malware detection. We scanned 88,555 topic specific URLs run through an open source malware detection platform VirusTotal (www.virustotal.com).

For more about the FAS Disinformation Research Group and to see previous reports, visit the project page here.

A National Strategy to Counter COVID-19 Misinformation

Summary

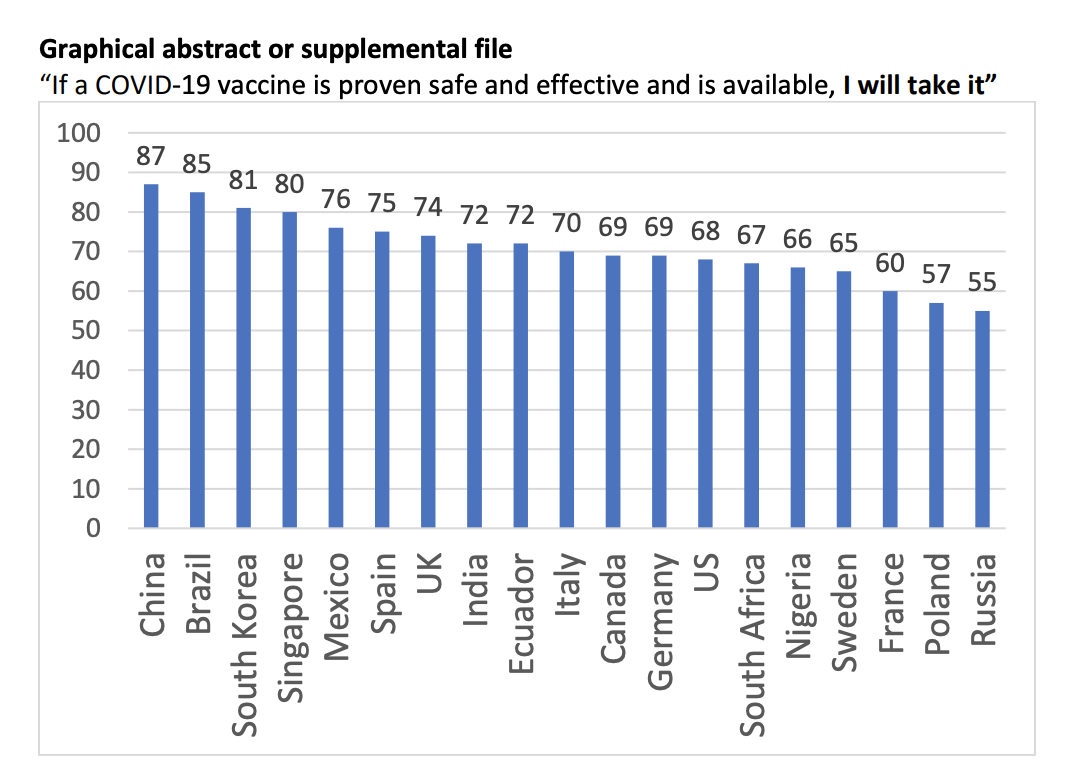

The United States accounts for over 20% of global deaths related to COVID-19 despite only having 4% of the world’s population. This unacceptable reality is in part due to the tsunami of misinformation surrounding COVID-19 that has flooded our nation. Misinformation not only decreases current compliance with best practices for containing and mitigating the spread of COVID-19, but will also feed directly into resistance against future administration of a vaccine or additional public-health measures.

The next administration should establish an office at the Department of Health and Human Services dedicated to combating COVID-19 misinformation. This office should lead a coordinated effort that:

- Ensures that evidence-based findings are at the core of COVID-19 response strategies.

- Utilizes data science and behavioral analytics to detect and counter COVID-19 misinformation.

- Works with social-media companies to remove misinformation from online platforms.

- Partners with online influencers to promote credible information about COVID-19.

- Encourages two-way conversations between public-health officials and the general public.

- Ensures that public-health communications are supported by on-the-ground action.

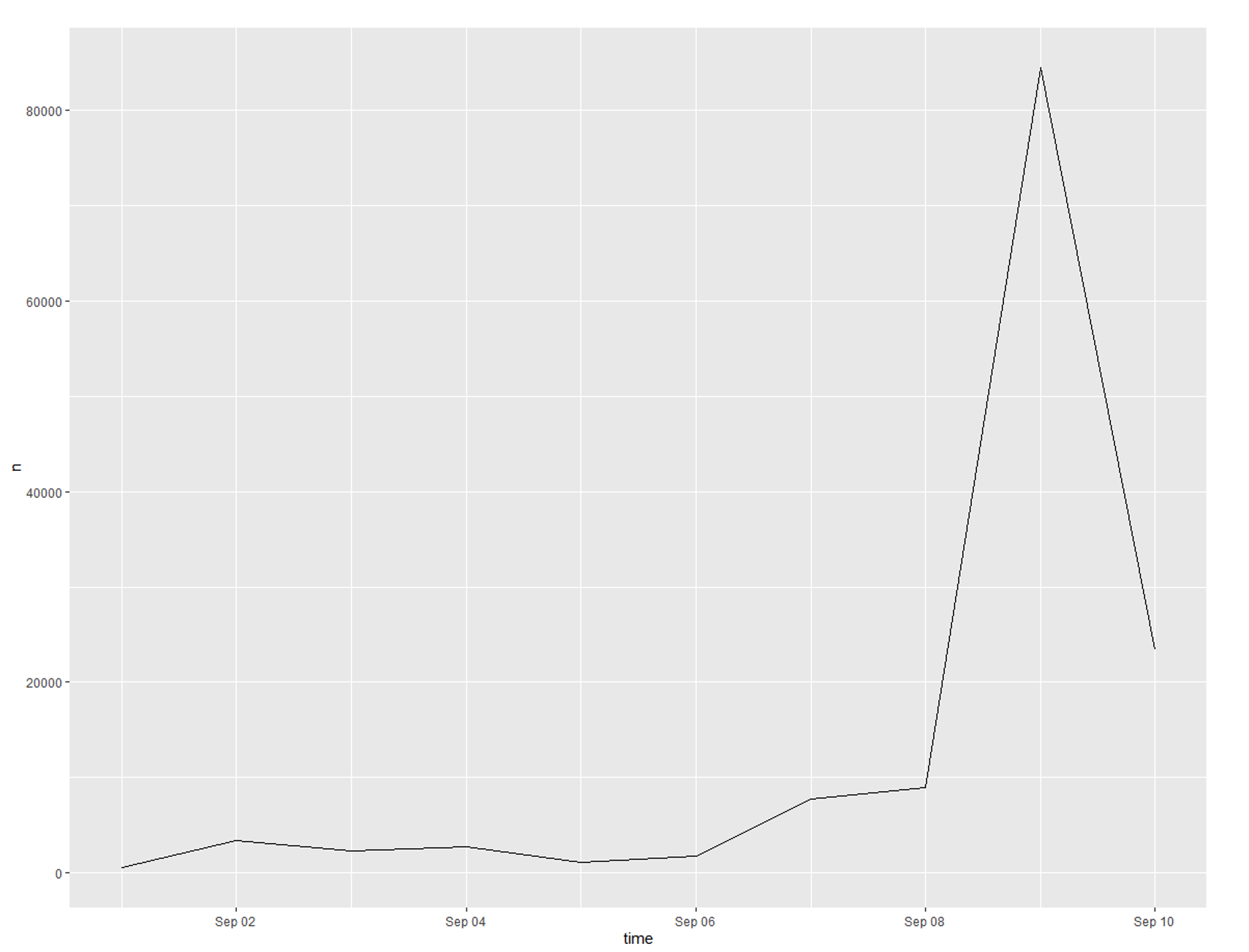

Social Media Conversations in Support of Herd Immunity are Driven by Bots

Key highlights

- Approximately half of the profiles pushing the case for herd immunity are artificial accounts. These bot or bot-like accounts are generally characterized as engaging in abnormally high levels of retweets and low content diversity.

- The high level of bot-like behavior attributed to support for the Great Barrington Declaration on social media indicates the conversation is manipulated and inorganic in comparison to the scientific consensus-based conversation opposing herd immunity theories. A consequence of high frequency of inorganic activity is the creation of a majority illusion (when certain members within a social network give the appearance that an idea or opinion is more popular than it is).

Online debate surrounding herd immunity shows one-sided automation

For months, debates about so-called herd immunity have occurred internationally. The idea behind this herd immunity strategy is to shield vulnerable populations while allowing COVID-19 transmission to go uncontrolled among less vulnerable populations. This strategy has been dismissed by many scientists for several ethical and practical reasons, such as the large size of vulnerable populations in countries like the US, and a lack of full understanding of longer-term impacts of SARS-CoV-2 on lower-risk groups. However, the conversation has increased in support, partially due to the embrace of the concept by a senior advisor to President Trump, Dr. Scott Atlas, who has called for the US to attempt the strategy. Support for the strategy has been outlined by a small group of public health scientists in the Great Barrington Declaration.