Finding True North with Community Navigator Programs

State, local, and Tribal governments still face major capacity issues when it comes to accessing federal funding opportunities – even with the sheer amount of programs started since the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) were passed. Communities need more technical assistance if implementation of those bills is going to reach its full potential, but federal agencies charged with distributing funding can’t offer the amount needed to get resources to where they need to go quickly, effectively, and equitably.

Community navigator programs offer a potential solution. Navigators are local and regional experts with a deep understanding of the climate and clean energy challenges and opportunities in their area. These navigators can be trained in federal funding requirements, clean energy technologies, permitting processes, and more – allowing them to share that knowledge with their communities and boost capacity.

Federal agencies like the Department of Energy (DOE) should invest in standing up these programs by collecting feedback on specific capacity needs from regional partners and attaching them to existing technical assistance funding. These programs can look different, but agencies should consider specific goals and desired outcomes, identify appropriate regional and local partners, and explore additional flexible funding opportunities to get them off the ground.

Community navigator programs can provide much-needed capacity combined with deep place-based knowledge to create local champions with expertise in accessing federal funding – relieving agencies of technical assistance burdens and smoothing grant-writing processes for local and state partners. Agencies should quickly take advantage of these programs to implement funding more effectively.

Challenge

BIL/IRA implementation is well under way, with countless programs being stood up at record speed by federal agencies. Of course, the sheer size of the packages means that there is still quite a bit of funding on the table at DOE that risks not being distributed effectively or equitably in the allotted time frame. While the agency is making huge strides to roll out its resources—which include state-level block grants, loan guarantee programs, and tax rebates—it has limited capacity to fully understand the unique needs of individual cities and communities and to support each location effectively in accessing funding opportunities and implementing related programs.

Subnational actors own the burden of distributing and applying for funding. States, cities, and communities want to support distribution, but they are not equally prepared to access federal funding quickly. They lack what officials call absorptive capacity, the ability to apply for, distribute, and implement funding packages. Agencies don’t have comprehensive knowledge of barriers to implementation across the hundreds of thousands of communities and can’t provide individualized technical assistance that is needed.

Two recent research projects identified several keys ways that cities, state governments, and technical assistance organizations need support from federal agencies:

- Identifying appropriate federal funding opportunities and matching with projects and stakeholders

- Understanding complex federal requirements and processes for accessing those opportunities

- Assistance with completing applications quickly and accurately

- Assembling the necessary technical capacity during the pre-application period to develop a quality application with a higher likelihood of funding

- Guidance on allowable expenditures from federal funding that support the overall technical capacity or coordinating capability of a subnational entity to collect, analyze, and securely share data on project outcomes

While this research focuses on several BIL/IRA agencies, the Department of Energy in particular distributed hundreds of billions of dollars to communities over the past few years. DOE faces an additional challenge: up until 2020, the agency was mainly focused on conducting basic science research. With the advent of BIL, IRA, and the CHIPS and Science Act, it had to adjust quickly to conduct more deployment and loan guarantee activities.

In order to meet community needs, DOE needs help – and at its core, this problem is one of talent and capacity. Since the passage of BIL, DOE has increased its hiring and bolstered its offices through the Clean Energy Corps.

Yet even if DOE could hire faster and more effectively, the sheer scope of the problem outweighs any number of federal employees. Candidates need not only certain skills but also knowledge specific to each community. To fully meet the needs of the localities and individuals it aims to reach, DOE would need to develop thorough community competency for the entire country. With over 29,000 defined communities in the United States – with about half being classified as ‘low capacity’ – it’s simply impossible to hire enough people or identify and overcome the barriers each one faces in the short amount of time allotted to implementation of BIL/IRA. Government needs outside support in order to distribute funds quickly and equitably.

Opportunity

DOE, the rest of the federal government, and the national labs are keen to provide significant technical assistance for their programs. DOE’s Office of State and Community Energy Programs has put considerable time and energy into expanding its community support efforts, including the recently stood up Office of Community Engagement and the Community Energy Fellows program.

National labs have been engaging communities for a long time – the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) conducts trainings and information sessions, answers questions, and connects communities with regional and federal resources. Colorado and Alaska, for example, were well-positioned to take advantage of federal funding when BIL/IRA were released as a result of federal training opportunities from the NREL, DOE, and other institutions, as well as local and regional coordinated approaches to preparing. Their absorptive capacity has helped them successfully access opportunities – but only because communities, cities, and Tribal governments in those regions have spent the last decade preparing for clean energy opportunities.

While this type of long-term technical assistance and training is necessary, there are resources available right now that are at risk of not being used if states, cities, and communities can’t develop capacity quickly. As DOE continues to flex its deployment and demonstration muscles, the agency needs to invest in community engagement and regional capacity to ensure long-term success across the country.

A key way that DOE can help meet the needs of states and cities that are implementing funding is by standing up community navigator programs. These programs take many forms, but broadly, they leverage the expertise of individuals or organizations within a state or community that can act as guides to the barriers and opportunities within that place.

Community navigators themselves have several benefits. They can act as a catalytic resource by delivering quality technical assistance where federal agencies may not have capacity. In DOE’s case, this could help communities understand funding opportunities and requirements, identify appropriate funding opportunities, explore new clean energy technologies that might meet the needs of the community, and actually complete applications for funding quickly and accurately. They understand regional assets and available capital and have strong existing relationships. Further, community navigators can help build networks – connecting community-based organizations, start-ups, and subnational government agencies based on focus areas.

The DOE and other agencies with BIL/IRA mandates should design programs to leverage these navigators in order to better support state and local organizations with implementation. Programs that leverage community navigators will increase the efficiency of federal technical assistance resources, stretching them further, and will help build capacity within subnational organizations to sustain climate and clean energy initiatives longer term.

These programs can target a range of issues. In the past, they have been used to support access to individual benefits, but expanding their scope could lead to broader results for communities. Training community organizations, and by extension individuals, on how to engage with federal funding and assess capital, development, and infrastructure improvement opportunities in their own regions can help federal agencies take a more holistic approach to implementation and supporting communities. Applying for funding takes work, and navigators can help – but they can also support the rollout of proposed programs once funding is awarded and ensure the projects are seen through their life cycles. For example, understanding broader federal guidance on funding opportunities like the Office of Management and Budget’s proposed revisions to the Uniform Grants Guidance can give navigators and communities additional tools for monitoring and evaluation and administrative capacity.

Benefits of these programs aren’t limited to funding opportunities and program implementation – they can help smooth permitting processes as well. Navigators can act as ready-made champions for and experts on clean energy technologies and potential community concerns. In some communities, distrust of clean energy sources, companies, and government officials can slow permitting, especially for emerging technologies that are subject to misinformation or lack of wider recognition. Supporting community champions that understand the technologies, can advocate on their behalf, and can facilitate relationship building between developers and community members can reduce opposition to clean energy projects.

Further, community navigator programs could help alleviate cost-recovery concerns from permitting teams. Permitting staff within agencies understand that communities need support, especially in the pre-application period, but in the interest of being good stewards of taxpayer dollars they are often reluctant to invest in applications that may not turn into projects.

Overall, these programs have major potential for expanding the technical assistance resources of federal agencies and the capacity of state and local governments and community-based organizations. Federal agencies with a BIL/IRA mandate should design and stand up these programs alongside the rollout of funding opportunities.

Plan of Action

With the Biden Administration’s focus on community engagement and climate and energy justice, agencies have a window of opportunity in which to expand these programs. In order to effectively expand community navigator programs, offices should:

Build community navigator programs into existing technical assistance budgets.

Offices at agencies and subcomponents with BIL/IRA funding like the Department of Energy, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have expanded their technical assistance programs alongside introducing new initiatives from that same funding. Community navigator programs are primarily models for providing technical assistance – and can use programmatic funding. Offices should assess funding capabilities and explore flexible funding mechanisms like the ones below.

Some existing programs are attached to large block grant funding, like DOE’s Community Energy Programs attached to the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grant Program. This is a useful practice as the funding source has broad goals and is relatively large and regionally nonspecific.

Collect feedback from regional partners on specific challenges and capacity needs to appropriately tailor community navigator programs.

Before setting up a program, offices should convene local and regional partners to assess major challenges in communities and better design a program. Feedback collection can take the form of journey mapping, listening sessions, convenings, or other structures. These meetings should rely on partners’ expertise and understanding of the opportunities specific to their communities.

For example, if there’s sufficient capacity for grant-writing but a lack of expertise in specific clean energy technologies that a region is interested in, that would inform the goals, curricula, and partners of a particular program. It also would help determine where the program should sit: if it’s targeted at developing clean energy expertise in order to overcome permitting hurdles, it might fit better at the BLM or be a good candidate for a partnership between a DOE office and BLM.

Partner with other federal agencies to develop more holistic programs.

The goals of these programs often speak to the mission of several agencies – for example, the goal of just and equitable technical assistance has already led to the Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers program, a collaboration between EPA and DOE. By combining resources, agencies and offices can even further expand the capacity of a region and increase accessibility to more federal funding opportunities.

A good example of offices collaborating on these programs is below, with the Arctic Energy Ambassadors, funded by the Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP) and the Arctic Energy Office.

Roadmap for Success

There are several initial considerations for building out a program, including solidifying the program’s goals, ensuring available funding sources and mechanisms, and identifying regional and local partners to ensure it is sustainable and effective. Community navigator programs should:

Identify a need and outline clear goals for the program.

Offices should clearly understand the goals of a program. This should go without saying, but given the inconsistency in needs, capacity, and readiness across different communities, it’s key to develop a program that has defined what success looks like for the participants and region. For example, community navigator programs could specifically work to help a region navigate permitting processes; develop several projects of a singular clean energy technology; or understand how to apply for federal grants effectively. Just one of those goals could underpin an entire program.

Ideally, community navigator programs would offer a more holistic approach – working with regional organizations or training participants who understand the challenges and opportunities within their region to identify and assess federal funding opportunities and work together to develop projects from start to finish. But agencies just setting up programs should start with a more directed approach and seek to understand what would be most helpful for an area.

Source and secure available funding, including considerations for flexible mechanisms.

There are a number of available models using different funding and structural mechanisms. Part of the benefit of these programs is that they don’t rely solely on hiring new technical assistance staff, and offices can use programmatic funds more flexibly to work with partners. Rather than hiring staff to work directly for an agency, offices can work with local and regional organizations to administer programs, train other individuals and organizations, and augment local and community capacity.

Further, offices should aim to work across the agency and identify opportunities to pool resources. The IRA provided a significant amount of funding for technical assistance across the agency – for example, the State Energy Program funding at SCEP, the Energy Improvements in Rural and Remote Areas funding at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), and the Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers program from a Department of Transportation/Department of Energy partnership could all be used to fund these programs or award funding to organizations that could administer programs.

Community navigator programs could also be good candidates for entities like FESI, the DOE’s newly authorized Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation. Although FESI must be set up by DOE, once formally established it becomes a 501(c)(3) organization and can combine congressionally appropriated funding with philanthropic or private investments, making it a more flexible tool for collaborative projects. FESI is a good tool for the partnerships described above – it could hold funding from various sources and support partners overseeing programs while convening with their federal counterparts.

Finally, DOE is also exploring the expanded use of Partnership Intermediary Agreements (PIAs), public-private partnership tools that are explicitly targeted at nontraditional partners. As the DOE continues to announce and distribute BIL/IRA funds, these agreements could be used to administer community navigator programs.

Build relationships and partner with appropriate local and regional stakeholders.

Funding shouldn’t be the only consideration. Agency offices need to ensure they identify appropriate local and regional partners, both for administration and funding. Partners should be their own form of community navigators – they should understand the region’s clean energy ecosystem and the unique needs of the communities within. In different places, the reach and existence of these partners may vary – not every locality will have a dedicated nonprofit or institution supporting clean energy development, environmental justice, or workforce, for example. In those cases, there could be regional or county-level partners that have broader scope and more capacity and would be more effective federal partners. Partner organizations should not only understand community needs but have a baseline level of experience in working with the federal government in order to effectively function as the link between the two entities. Finding the right balance of community understanding and experience with federal funding is key.

This is not foolproof. NREL’s ‘Community to Clean Energy (C2C) Peer Learning Cohorts’ can help local champions share challenges and best practices across states and communities and are useful tools for enhancing local capacity. But this program faces similar challenges as other technical assistance programs: participants engage with federal institutions that provide training and technical expertise that may not directly speak to local experience. It may be more effective to train a local or regional organization with a deeper understanding of the specific challenges and opportunities of a place and greater immediate buy-in from the community. It’s challenging for NREL as well to identify the best candidates in communities across the country without that in-depth knowledge of a region.

Additional federal technical assistance support is sorely needed if BIL/IRA funds are to be distributed equitably and quickly. Federal agencies are moving faster than ever before but don’t have the capacity to assess state and local needs. Developing models for state and local partners can help agencies get funding out the door and where it needs to go to support communities moving towards a clean energy transition.

Case Study: DOE’s Arctic Energy Ambassadors

DOE’s Arctic Energy Office (AEO) has been training state level champions for years but recently introduced the Arctic Energy Ambassadors program, using community navigators to expand clean energy project development.

The program, announced in late October 2023, will support regional champions of clean energy with training and resources to help expand their impact in their communities and across Alaska. The ambassadors’ ultimate goal is clean energy project development: helping local practitioners access federal resources, identify appropriate funding opportunities, and address their communities’ specific clean energy challenges.

The Arctic Energy Office is leading the program with help from several federal and subnational organizations. DOE’s Office of State and Community Engagement and Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy are also providing funding.

On the ground, the Denali Commission will oversee distribution of funding, and the Alaska Municipal League will administer the program. The combination of comparative advantages is what will hopefully make this program successful. The Denali Commission, in addition to receiving congressionally appropriated funding, can receive funds from other nonfederal sources in service of its mission. This could help the Commission sustain the ambassadors over the longer term and use funds more flexibly. The Commission also has closer relationships with state-level and Tribal governments and can provide insight into regional clean energy needs.

The Alaska Municipal League (AML) brings additional value as a partner; its role in supporting local governments across Alaska gives it a strong sense of community strengths and needs. AML will recruit, assess, and identify the 12 ambassadors and coordinate program logistics and travel for programming. Identifying the right candidates for the program requires in-depth knowledge of Alaskan communities, including more rural and remote ones.

For its own part, the AEO will provide the content and technical expertise for the program. DOE continues to host an incredible wealth of subject matter knowledge on cutting-edge clean energy technologies, and its leadership in this area combined with the local understanding and administration by AML and Denali Commission will help the Arctic Energy Ambassadors succeed in the years to come.

In all, strong local and regional partners, diverse funding sources and flexible mechanisms for delivering it, and clear goals for community navigator programs are key for successful administration. The Arctic Energy Ambassadors represents one model that other agencies can look to for success.

Case study: SCEP’s Community Energy Fellows Program

DOE’s State and Community Energy Programs office has been working tirelessly to implement BIL and IRA, and last year as part of those efforts it introduced the Community Energy Fellows Program (CEFP).

This program aims to support local and Tribal governments with their projects funded by the Energy Efficiency and Conservation Block Grants. CEFP matches midcareer energy professionals with host organizations to provide support and technical assistance on projects as well as learn more about how clean energy development happens.

Because the program has a much broader scope than the Arctic Energy Fellows, it solicits and assesses host institutions as well as Fellows. This allows SCEP to more effectively match the two based on issue areas, expertise, and specific skillsets. This structure allows for multiple community navigators – the host institution understands the needs of its community and the Fellow brings expertise in federal programs and clean energy development. Both parties gain from the fellowship.

In addition, SCEP has added another resource: Clean Energy Coaches, who provide another layer of expertise to the host institution and the Fellow. These coaches will help develop the Fellows’ skills as they work to support the host institution and community.

Some of the awards are already being rolled out, with a second call for host institutions and Fellows out now. Communities in southern Maine participating in the program are optimistic about the support that navigators will provide – and their project leads have a keen sense of the challenges in their communities.

As the program continues to grow, it can provide a great opportunity for other agencies and offices to learn from its success.

Dr. Adria Brooks, Grid Deployment Office,

Transmission Champion

This series of interviews spotlights scientists working across the country to implement the U.S. Department of Energy’s massive efforts to transition the country to clean energy, and improve equity and address climate injustice along the way. The Federation’s clean energy workforce report discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with ramping up this dynamic, in-demand workforce. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE.

Dr. Adria Brooks’ journey to the Department of Energy has been a winding road. From the forests of Western Massachusetts, to the desert mountains of Arizona, to the frosty fields of Wisconsin, she has made a career out of teaching others why they should care about clean energy.

From Felling Trees to Harnessing Sunshine

Dr. Brooks’ pathway to clean energy began as an undergraduate when she took time off from her Bachelors degree to work on a forest trail crew. She spent nine months on a trail crew in Western Massachusetts. “I was trained to be a lumberjack, basically, but for conservation purposes – so felling trees to build bridges or trails and things. I loved that job; it was really fun and helped me connect with the environment.” Interacting with the environment in such a physical, tangible way encouraged her to change her course of study from space sciences to climate change and energy issues.

Soon after switching her academic focus, she found work at a solar test facility managed by her alma mater, the University of Arizona. Very quickly she got hands-on experience in every facet of solar energy, from installation of modules and inverters to running experiments, collecting data, doing analysis, and writing reports. In addition, she honed her science communication skills by giving tours to visiting audiences – ranging from Girl Scouts to the late Senator John McCain.

Understanding how solar and its supporting power systems worked on the ground illuminated a new lesson for Dr. Brooks: “Solar [was] not the problem – the power grid is the reason we can’t get more clean energy.” With this new understanding, Dr. Brooks pursued both a Master’s and a PhD in electrical engineering, with a certificate in energy analysis and policy.

“I loved the policy piece of it, because it brought together economists and engineers and policy folks,” she says. This cohort of people came from different disciplines into the energy analysis and policy program at University of Wisconsin. “It was a really cool program; I loved it.”

State Government Service

While pursuing her dissertation Dr. Brooks started working at the Wisconsin Public Service Commission as a transmission engineer. This demanding state government role proved to be a valuable training ground, building on the communication skills she honed in Arizona. As an engineer she worked across two different administrations, explaining electrical transmission systems, their challenges, and how different policies might impact reliability and clean energy goals. The key to effectively engaging her audience? Understanding their specific goals and meeting them where they were.

“The information [on power systems] I was providing was essentially the same. The question became: What lens am I using? Am I focusing on reliability and consumer cost? Am I focusing on decarbonisation? From my view, it didn’t really matter. The solutions wind up being pretty similar, but it was eye-opening for me to learn how to communicate the science to folks that don’t have that background, but who have the ability to make big decisions affecting the power grid. I thoroughly loved that job. And that’s what set me off wanting to do more policy work at the federal level.”

Joining DOE and the GDO

Setting her sights on the federal government, Dr. Brooks joined the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)in 2020 as a AAAS Science Technology Policy Fellow in the Department’s Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Office. The position was meant to be research heavy and focused on maximizing taxpayer investments in different investigative projects. But when a new administration came in with a long list of renewable energy goals and a serious focus on transmission, Dr. Brooks found herself reassigned to the Office of Electricity, and later hired into the newly created Grid Deployment Office (GDO).

GDO, which is tasked with investing in critical generation facilities, increasing grid resilience, and improving and expanding transmission and distribution systems to provide reliable, affordable electricity, needed internal folks who understood the science of renewable energy and grid deployment, and who could translate it to cross-cutting program teams and leadership who weren’t mired in the details day-to-day. Dr. Brooks found her groove by bringing in skills from her days at the solar test facility and the Wisconsin Public Service Commission. “My job became a lot more policy focused, trying to explain the science to stand up new programs related to the transmission and the power grid,” she said. Dr. Brooks’ communications skills combined with her technical background are hugely important because the science of electrical transmission – and how that impacts what clean energy development can occur and how quickly – is often an incomprehensible thing for people, including policymakers.

Communication remains a crucial part of Dr. Brooks’s role and contribution at DOE.

A big win for Dr. Brooks and GDO was the October 2023 release of the National Transmission Needs Study. This study is a useful planning reference to efficiently and effectively deploy resources to update and expand the nation’s transmission grid infrastructure. Conducted every three years, this most recent study is more expansive in scope than previous versions. “Future policy decisions that the Department makes are going to be based on the findings of this report. It also provides a lot of valuable insight for utilities, developers, and other decision makers across the country, so that’s very big,” Dr. Brooks said. Although modest, she played a major role in planning, analyzing the data for, and rolling out the report.

The journey that brought Dr. Brooks to DOE seems almost preordained, as she is bringing her specific knowledge to bear on the urgent problem of climate change.

“Now I feel more impactful being so close to the policymaking, getting to have one foot in the engineering analysis and one foot in policy development. That is really exciting. I do think a lot of that is a very specific opportunity that matched the specific skill set that I had. I have felt very lucky in that regard, to be seen as an expert around the Department. Lots of different offices will reach out, or policymakers will reach out to try to get clarity on the transmission system, and that is exciting. But I also know that it’s luck that I stepped in at the exact time to make that opportunity for myself.”

Looking Ahead

While the transmission issues she works on can often feel insurmountable, Dr. Brooks feels optimistic about the future.

“I am hopeful about how much transmission we’re going to be able to build over the next 10 to 15 years. The word ‘transmission’ is now a common term; people understand it. A couple of years ago, I would talk to folks about my job and they would say, ‘I don’t understand what the power grid is.’ Now, more people at least understand what the grid is, and that it is a bottleneck to getting clean energy online. That’s huge. I think we’re going to make a lot more progress than I had any hope of us making even a couple of years ago.”

More than just the policy implications of her work, Dr. Brooks is impressed by how many young professionals want to join government service to play an active role in fighting climate change. Starting in Tucson, continuing in Wisconsin, and now from her home in Boston, she’s volunteered in a variety of roles unrelated to energy systems and grid work that facilitate climate discussions. “I’ve always found kids to be super eager and curious to learn”, she said, providing even more hope that the work will continue with the support of future generations.

Dr. Olivia Lee, Grid Deployment Office (GDO),

Fighting for Resilient Communities

This series of interviews spotlights scientists working across the country to implement the U.S. Department of Energy’s massive efforts to transition the country to clean energy, and improve equity and address climate injustice along the way. The Federation’s clean energy workforce report discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with ramping up this dynamic, in-demand workforce. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE.

From the rugged snowbanks of Alaska to the tropical seaside of Hawai’i, Dr. Olivia Lee Mei Ling has sought to improve the access to, and delivery of, energy. To understand her journey to the Department of Energy and her work today, our story begins in Alaska.

Women in Polar Science

After obtaining her PhD in Wildlife and Fisheries Science from Texas A&M University, Dr. Lee headed north to accept a teaching position at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. She spent ten years there, first in the Geophysical Department and later in the International Arctic Research Center. While there she developed future energy scenarios for Alaskans, working with federal, state, tribal and local governments, expert stakeholders and non-governmental organizations. Those conversations were sometimes difficult – bringing together a wide range of perspectives and personalities and asking them to align on a plan – but were vital to the state’s future.

“Building those relationships [between energy stakeholders], and helping those conversations continue to happen was a fantastic opportunity to delve into how policy and science can co-occur.”

While at the university she did a short stint with the National Science Foundation as an IPA [Intergovernmental Personnel Act, a temporary position in the federal government] supporting researchers doing work in the Arctic. There she was involved in interagency programs, with a lot of emphasis on developing diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives across agencies.

During this time Dr. Lee supported growing outreach for a group of scientists, Women in Polar Science. She identified a need for this group after submitting an article to a geophysical journal about the group’s work – which was rejected because it ‘wasn’t of interest to a wide enough audience.’

Dr. Lee said it was “appalling to think that the science community is not interested or doesn’t believe there is enough value in sharing what we’ve learned about the women who face adversity doing research in polar environments. And so I co-founded the Interagency Arctic Research Policy Committee’s (IARPC) community of interest on diversity, equity, and inclusion issues.” The group has grown and since taken off, bringing more scientists together to work on DEI within arctic research.

Dr. Lee’s work in Polar Science led to more social ties within Alaska’s Tribal communities, and a deeper understanding of their unique needs. These experiences showed the value of skills beyond traditional scientific training. Empathy quickly became her guiding principle; as an oil-rich state, it became clear that any energy plan in Alaska needed to address community needs first. “In some areas, like in Alaska, diesel will have to continue to be a part of the energy mix until they’re able to support something more reliable year-round than renewables can offer right now. We need to push clean energy, but not at the cost of livelihoods and safety of communities.” says Dr. Lee. To non-scientists, this statement might be surprising – isn’t the goal to eliminate all fossil fuels? No, the goal is to support a just transition in every region.

Moving States, Territories and Tribes to Clean Energy As Quickly As Possible at DOE

When the Department of Energy began ramping up hiring through the Clean Energy Corps, Dr. Lee was immediately interested. When she interviewed with the Grid Deployment Office, the office recognized her knowledge and skills were unique and vital to their work, and in particular, her combination of scientific expertise and knowledge of the needs associated with Tribal communities.

“We work with a lot of tribes, and it’s a skill set that not everyone has – to take the time to self-educate on the history of colonization, to respectfully interact with tribes, understand that they are self-governing entities and continue to face a lot of challenges in developing their economies.

At GDO, Dr. Lee supports grid resilience projects. Her team thinks critically about what specific infrastructure investments could help communities be more resilient to impacts from climate change – and what resources or guidance communities need to implement those ideas. “We’re not just reacting to disasters as they happen, but thinking about 10 years, 20 years down the road, where do we need to be? How do we sustain energy access and what partnerships we can help build now to make sure that this is an ongoing process?

She continues: “It’s really exciting to know that you are a part of modernizing the grid in a way that will have tangible benefits in the near term – and in the long term as well, if we’re able to help states and tribes plan how [IRA funds] can shape their sustainability moving forward.”

There are lots of unknowns: what kind of infrastructure exists today, and what kind of investment is required to hasten transition? What resources specific to that location are available now, and how can productive programs be amplified? The work involves measuring and modeling to ensure waste and harm are minimized, while maximizing positive environmental and economic opportunities across the lifecycle of any energy plan.

“In my particular program, we’re supporting projects that develop good resilience. And there’s a very strong emphasis on going beyond theoretical into implementation. Like: what specific infrastructure investments and projects are going to be done to make the electrical grid more resilient to impacts from climate change?”

Unsurprisingly, this work is more than spreadsheets of numbers. To deploy an energy upgrade so much more must be considered: a region’s history, its present day health, and how the region may evolve based on the impacts of climate change prediction models. How can the department meet communities where they are and at the same time prepare them for a changing environment?

Unexpected Opportunities to Build Grid Resilience

Dr. Lee shares one example of how her team did just that. One of the Alaskan tribes they work with requested funding for a project that seemed outside the bounds of grid resilience. They didn’t ask for wiring, poles or grounding, but for snow removal equipment for their wind facility.

During a recent snowstorm, the community couldn’t access their wind facilities because they lacked updated snow removal equipment. Without ready access to those facilities, if anything had gone wrong, the grid would have had problems as well. “It’s so important to have energy in Alaska winters – it’s life or death. You can’t just say ‘I’ll put on an extra blanket.’ Responding to a request for something as simple as snow removal equipment is an actual, valid, small step that we can take to support grid resilience.”

Dr. Lee’s ability to think creatively and understand the needs of remote communities are the skills that make her an exceptional team member. Without that level of understanding, that tribe may not have gotten support for equipment that at first glance, isn’t immediately related to grid resilience.

Advice for Those Seeking Roles in Government Clean Energy Work

Dr. Lee’s achievements underscore the importance of a strong federal workforce. She offered advice for those entering government for the first time: “Find mentors who can help you navigate how the government works, and be open to new opportunities and trying new things.” She adds that being open to learning and finding mentors in different offices and different career stages brings the most opportunities compared to a so-called “straight career path.”

She says another benefit is that the people working clean energy technology in the government are some of the most optimistic people. Her work at GDO – helping modernize and fortify the grid – is vital to the resilience and livelihood of communities across the country.

Using Other Transactions at DOE to Accelerate the Clean Energy Transition

Summary

The Department of Energy (DOE) should leverage its congressionally granted other transaction authority to its full statutory extent to accelerate the demonstration and deployment of innovations critical to the clean energy transition. To do so, the Secretary of Energy should encourage DOE staff to consider using other transactions to advance the agency’s core missions. DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management should provide resources to educate program and contracting staff on the opportunity that other transactions present. Doing so would unlock a less used but important tool in demonstrating and accelerating critical technology developments at scale with industry.

Challenge and Opportunity

OTs are an underleveraged tool for accelerating energy technology.

Our global and national clean energy transition requires advancing novel technology innovations across transportation, electricity generation, industrial production, carbon capture and storage, and more. If we hope to hit our net-zero emissions benchmarks by 2030 and 2050, we must do a far better job commercializing innovations, mitigating the risk of market failures, and using public dollars to crowd in private investment behind projects.

The Biden Administration and the Department of Energy, empowered by Congress through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), have taken significant steps to meet these challenges. The Loan Programs Office, the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, the Office of Technology Transitions, and many more dedicated public servants are working hard towards the mission set forward by Congress and the administration. They are deploying a range of grants, procurement contracts, and tax credits to achieve their goals, and there are more tools at their disposal to accelerate a just, clean energy transition. The large sums of money appropriated under BIL and IRA require new ways of thinking about contracting and agreements.

Congress gives several federal agencies the authority to use flexible agreements known as other transactions (OTs). Importantly, OTs are defined by what they are not. They are not a government contract or grant, and thus not governed by the Federal Acquisitions Regulations (FAR). Historically, NASA and the DoD have been the most frequent users of other transaction authorities, including for projects like the Commercial Orbital Transportation System at NASA which developed the Falcon 9 space vehicle, and the Global Hawk program at DARPA.

In contrast, the Department of Energy has infrequently used OTs, and even when it has, the programs have achieved no notable outcomes in support of their agency mission. When the DOE has used OTs, the agency has interpreted their authority as constraining them to cost-sharing research agreements. This restricts the creativity of agency staff in executing OTs. All the law says is that an OT is not a grant or contract. By limiting itself to cost sharing research agreements, DOE is preemptively foreclosing all other kinds of novel partnerships. This is critical because some nascent climate-solution technologies may face a significant market failure or a set of misaligned incentives that a traditional research and development transaction (R&D) may not fix.

This interpretation has hampered DOE’s use of OTs, limited its ability to engage small businesses and nontraditional contractors, and prevented DOE from fully pursuing its agency mission and the administration’s climate goals.

Exploring further use of OTs would open up a range of possibilities for the agency to help address critical market failures, help U.S. firms bridge the well-documented valleys of death in technology development, and fulfill the benchmarks laid out in the DOE’s Pathways to Commercial Liftoff.

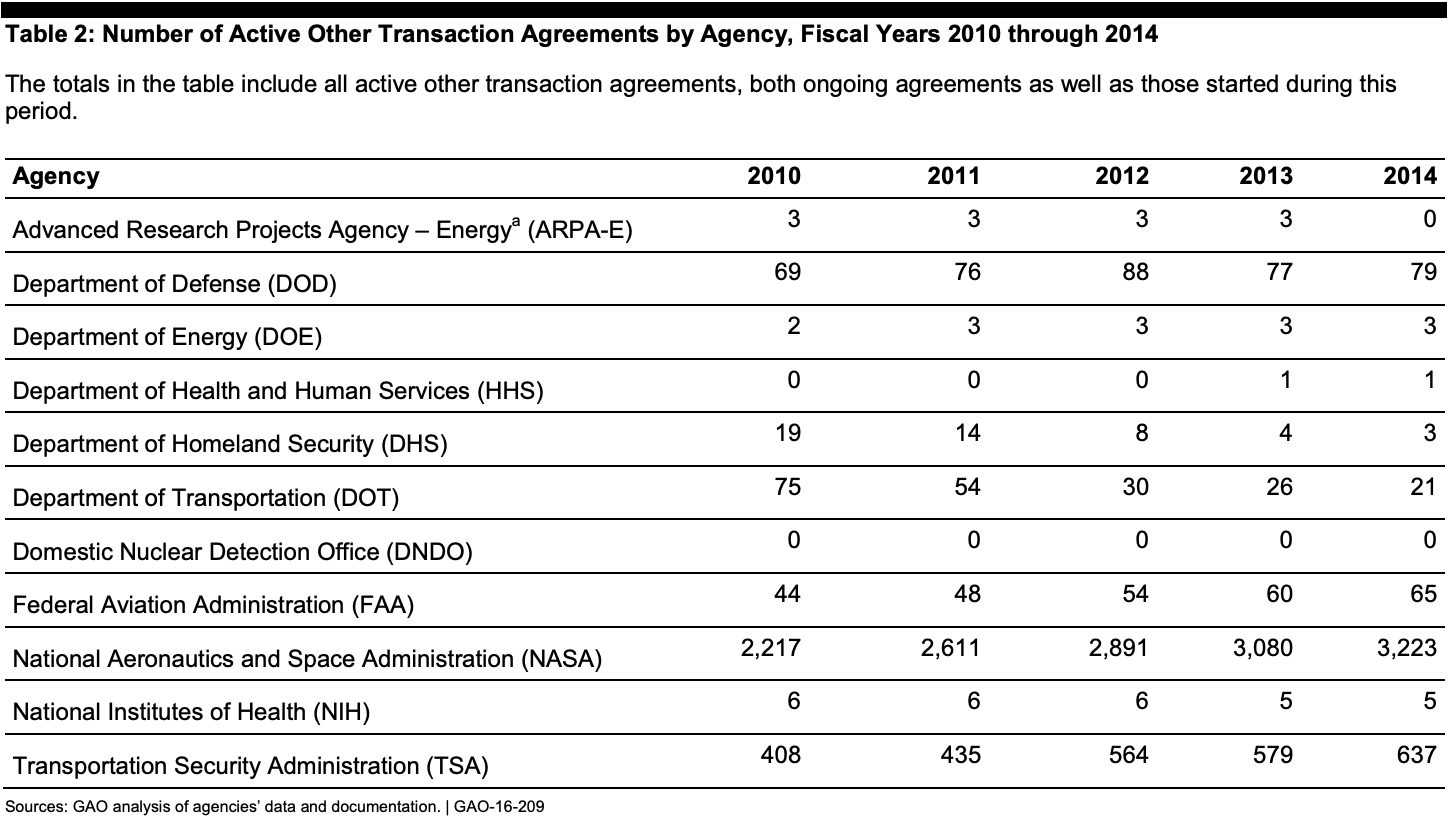

According to a GAO report from 2016, the DOE has only used OTs a handful of times since they had the authority updated in 2005, nearly two decades ago. Compare the DOE’s use of OTs to other agencies in the four-year period in the table below (the most recent for which there is open data).

From GAO-16-209

Almost every other agency uses OTs at a significantly higher rate, including agencies that have smaller overall budgets. While quantity of agreements is not the only metric to rely on, the magnitude of the discrepancy is significant.

Other agencies have made significant changes since 2014, most notably the Department of Defense. A 2020 CSIS report found that DoD use of OTs for R&D increased by 712% since FY2015, including a 75% increase in FY2019. This represents billions of dollars in awards, much of which went to consortia, including for both prototyping and production transactions. While the DOE does not have the same budget or mission as DoD, the sea change in culture among DoD officials willing to use OTs over the past few years is instructive. While DoD did receive expanded authority in the FY2015 and 2016 NDAA, this alone did not account for the massive increase. A cultural shift drove program staff to look at OTs as ways to quickly prototype and deploy solutions that could advance their missions, and support from leadership enabled staff to successfully learn how and when to use OTs.

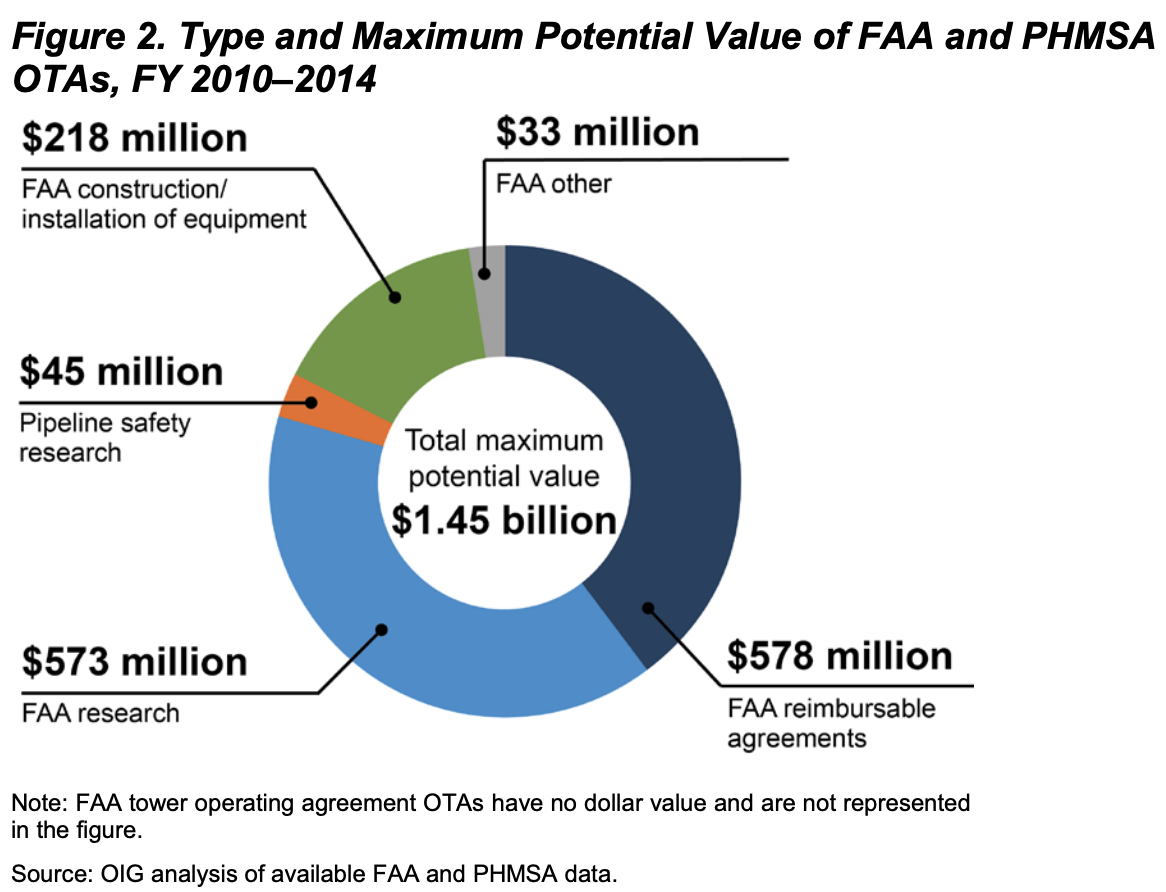

The Department of Transportation (DOT) only uses OTs for two agencies, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHIMSA). Like DOE, the FAA is not restricted in what it can and can’t use OTs for. It is authorized to “carry out the functions of the Administrator and the Administration…on such terms and conditions as the Administrator may consider appropriate.” Unlike DOE, the FAA and DOT have used their authority for several dozen transactions a year, totaling $1.45 billion in awards between 2010 and 2014.

From the GAO chart (Table 1), it’s clear that ARPA-E also follows the DOE in deploying very few OTs in support of its mission. Despite being originally envisioned as a high-potential, high-impact funder for technology that is too early in the R&D process for private investors to support, the most recent data shows that ARPA-E does not use OTs flexibly to support high-potential, high-impact tech.

The same GAO report cited above stated that:

“DOE’s regulations—because they are based on DOD’s regulations—include requirements that limit DOE’s use of other transaction agreements…. Officials told us they plan to seek approval from the Office of Management and Budget to modify the agency’s other transaction regulations to better reflect DOE’s mission, consistent with its statutory authority. According to DOE officials, if the changes are approved, DOE may increase its use of other transaction agreements.”

That report was published in 2016, but it is unclear that any changes were sought or approved, though they likely do not need to change any regulations at all to actually make use of their authority.1 The realm of the possible is quite large, and DOE has yet to fully explore the potential benefits to its mission that OTs provide.

DOE can use OTs without any further authority to drive progress in critical technologies.

The good news is that DOE has the ability to use OTs without further guidance from Congress or formally changing any guidelines. Recognizing their full statutory authority would open up use cases for OTs that would help the DOE make meaningful progress towards its agency mission and the administration’s climate goals.

For example, the DOE could use OTs in the following ways:

- Using demand-side support mechanisms to reduce the “green premium” for promising technologies like hydrogen, carbon capture, sustainable aviation fuel, enhanced geothermal, and low-embodied construction materials like steel and concrete

- Coordinating the demonstration of promising technologies through consortia with private industry in support of their commercial liftoff goals

- Organizing joint demonstration projects with the DOT or other agencies with overlapping solution sets

- Rapidly and sustainably meeting critical energy infrastructure needs across rural areas

Given the exigencies of climate change and the need to rapidly decarbonize our society and economy, there are very real instances in which traditional research contracts or grants are not enough to move the needle or unlock a significant market opportunity for a technology. Forward contract acquisitions, pay for delivery contracts, or other forms of transactions that are nonstandard but critical to supporting development of technology are covered under this authority.

One promising area where it seems the DOE is currently using this approach is in supporting the hydrogen hubs initiative. Recently the DOE announced a $1 billion initiative for demand-side support mechanisms to mitigate the risk of market failures and accelerate the commercialization of clean hydrogen technologies. The Funding Opportunity Announcement (FOA) for the H2Hubs program notes that “other FOA launches or use of Other Transaction Authorities may also be used to solicit new technologies, capabilities, end-uses, or partners.” The DOE could use OTs more frequently as a tool to advance other critical commercial liftoff strategies or to maximize the impact of dollars appropriated to implementation of the BIL and IRA. Some areas that are ripe for creative uses of other transactions include:

- Critical Minerals Consortium: A critical minerals consortium of vendors, nonprofits, academics, and others all managed by a single entity could do more than just mineral processing improvement and R&D. It could take long-term offtake agreements and do forward purchasing of mineral supplies like graphite that are essential to the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries and other products. This could function similarly to the successful forward contract acquisition for the Strategic Petroleum Reserve executed in June 2023 by DOE.

This demand-pull would complement other recent actions taken to bolster critical minerals like the clean vehicle tax credit and the Loan Program Office’s loans to mineral processing facilities. Such a consortium could come from the existing critical materials institute or be formed by separate entities.

- Geothermal Consortium: Enhanced geothermal systems technology has received neither the attention nor the investment that it should proportional to its potential benefits as a path towards decarbonizing the electric grid. At the same time, legacy oil and natural gas industries have workforces, equipment, and experiences that can easily translate to growing the geothermal energy industry. Recently, the DOE funded the first cross-industry consortium with the $165 million GEODE competition grant awarded to Project Innerspace, Geothermal Rising, and the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

DOE could use other transactions to further support this nascent consortium and increase the demonstration and deployment of geothermal projects. The agency could also use other transactions to organize the sharing of critical subsurface data and resources through a single entity.

- Direct Air Capture (DAC): The carbon removal market faces extremely uncertain long-term demand, and unproven technological innovations may or may not present economically viable means of pulling carbon out of the atmosphere. In order to accelerate the pace of carbon removal innovation, aggregated demand structures like Frontier’s advanced market commitment have stepped up to organize pre-purchasing and offtake agreements between buyers and suppliers. The scale of the problem is such that government intervention will be necessary to capture carbon at a rate that experts believe is necessary to mitigate the worst warming pathways.

A carbon removal purchasing agreement for the DOE’s Regional Direct Air Capture Hubs could function much the same as the proposed hydrogen hubs initiative. It also could take the shape of a consortium of DAC vendors, nonprofits, scientists, and others managed by a single entity that can set standards for purchase agreements. This would cut the negotiation time among potential parties by a significant amount, allowing for cost saving and faster decarbonization.

- Rural Energy Improvements Consortium: The IRA appropriated $1 billion for energy improvements in rural and remote areas. Because of inherent resource limitations, the DOE will not be able to fund every potential compelling project that applies to this grant program. In order to keep the program from making single one-off grants for narrowly tailored projects, it could focus on funding projects with demonstrated catalytic impact. Through OTs, the DOE could encourage promising project developers to form a Rural Energy Improvement/Developers consortium that would not only help create efficiencies in renewable energy development and novel resilient local structures but attract private investment at a scale that each individual developer would not independently attract.

- Hydrogen Fuel Cell Lifespan Consortia: As hydrogen fuel cells start gaining traction across transportation, shipping, and industrial applications, a consortia for fuel cell R&D could help provide new insights into the degradation of fuel cells, organize uniform standards for recycling of fuel cells, and also provide unique financial incentives to hedge against early uncertainty of fuel cell lifespans. As firms invest in new fleets of fuel cell vehicles, it may help them to have an idea of what expected value they can receive for assets as they reach the end of their lifespans. A backstopped guarantee of a minimum price for assets with certain criteria could reduce uncertainty. Such a consortium could be led by the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC) and complement existing initiatives to accelerate domestic manufacturing.

- Long Duration Energy Storage (LDES): The DOE commercial liftoff pathway highlights the need to intervene to address stakeholder and investor uncertainty by providing long-term market signals for LDES. The tools they highlight to do so are carbon pricing, greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction targets, and transmission expansion. While these provide generalizable long-term signals, DOE could leverage OTs to provide more concrete signals for the value of LDES.

DOE could organize an advance market commitment for long-duration energy storage capabilities on federal properties that meet certain storage hour and grid integration requirements. Such a commitment could include the DoD and the General Services Administration (GSA), which own and operate the large portfolio of federal properties, including bases and facilities in hard-to-reach locations that could benefit from more predictable and secure energy infrastructure. Early procurement of capability-meeting but expensive systems could help diversify the market and drive technology down the cost curve to reach the target of $650 per kW and 75% RTE for intra-day storage and $1,100 per kW 55 and 60% RTE for multiday storage.

To use OTs more frequently, the DOE needs to focus on culture and education.

As noted, the DOE does not need additional authorization or congressional legislation to use OTs more frequently. The agency received authority in its original charter in 1977, codified in 42 U.S. Code § 7256, which state:

“The Secretary is authorized to enter into and perform such contracts, leases, cooperative agreements, or other similar transactions with public agencies and private organizations and persons, and to make such payments (in lump sum or installments, and by way of advance or reimbursement) as he may deem to be necessary or appropriate to carry out functions now or hereafter vested in the Secretary.” [emphasis added]

This and other legislation gives DOE the authority to use OTs as the Secretary deems necessary.

Later guidelines in implementation state that other officials at DOE who have been presidentially appointed and confirmed by the Senate are able to execute these transactions. The DOE’s Office of Acquisition Management, Office of General Counsel, and any other legal bodies involved should update any unnecessarily restrictive guidelines, or note that they will follow the original authority granted in the agency’s 1977 charter.

While that would resolve any implementation questions about the ability to use OT at DOE, the agency ultimately needs strong leadership and buy-in from the Secretary in order to take full advantage. As many observers note regarding DoD’s expanding use of OTs, culture is what matters the most. The DOE should take the following actions to make sure the changing of these guidelines empowers DOE public servants to their full potential:

- The Secretary should make clear to DOE leadership and staff that increased use of OTs is not only permissible but actively encouraged.

- The Secretary should provide internal written guidance to DOE leadership and program-level staff on what criteria need to be met for her to sign off on an OT, if needed. These criteria should be driven by DOE mission needs, technology readiness, and other resources like the commercial liftoff reports.

- The Office of Acquisition Management should collaboratively educate relevant program staff, not just contracting staff, on the use of OTs, including by providing cross-agency learning opportunities from peers at DARPA, NASA, DoD, DHS, and DOT.

- DOE should provide an internal process for designing and drawing up an OT agreement for staff to get constructive feedback from multiple levels of experienced professionals.

- DOE should issue a yearly report on how many OTs they agree to and basic details of the agreements. After four years, GAO should evaluate DOE’s use of OTs and communicate any areas for improvement. Since OTs don’t meet normal contracting disclosure requirements, some form of public disclosure would be critical for accountability.

Mitigating risk

Finally, there are many ways to address potential risks involved with executing new OTs for clean energy solutions. While there are no legal contracting risks (as OTs are not guided by the FAR), DOE staff should consider ways to most judiciously and appropriately enter into agreements. For one resource, they can leverage the eight recent reports put together by four different offices of inspector generals on agencies’ usage of other transactions to understand best practices. Other important risk limiting activities include:

- DoD commonly uses consortiums to gather critical industry partners together around challenges in areas such as advanced manufacturing, mobility, enterprise healthcare innovations, and more.

- Education of relevant parties and modeling of agreements after successful DARPA and NASA OTs. These resources are in many cases publicly available online and provide ready-made templates (for example, the NIH also offers a 500-page training guide with example agreements).

Conclusion

The DOE should use the full authority granted to it by Congress in executing other transactions to advance the clean energy transition and develop secure energy infrastructure in line with their agency mission. DOE does not need additional authorization or legislation from Congress in order to do so. GAO reports have highlighted the limitations of DOE’s OT use and the discrepancy in usage between agencies. Making this change would bring the DOE in line with peer agencies and push the country towards more meaningful progress on net-zero goals.

The following examples are pulled from a GAO report but should not be regarded as the only model for potential agreements.

Examples of Past OTs at DOE

“In 2010, ARPA-E entered into an other transaction agreement with a commercial oil and energy company to research and develop new drilling technology to access geothermal energy. Specifically, according to agency documentation, the technology being tested was designed to drill into hard rock more quickly and efficiently using a hardware system to transmit high-powered lasers over long distances via fiber optic cables and integrating the laser power with a mechanical drill bit. According to ARPA-E documents, this technology could provide access to an estimated 100,000 or more megawatts of geothermal electrical power in the United States by 2050, which would help ARPA-E meet its mission to enhance the economic and energy security of the United States through the development of energy technologies.

According to ARPA-E officials, an other transaction agreement was used due to the company’s concerns about protecting its intellectual property rights, in case the company was purchased by a different company in the future. Specifically, one type of intellectual property protection known as “march-in rights” allows federal agencies to take control of a patent when certain conditions have not been met, such as when the entity has not made efforts to commercialize the invention within an agreed upon time frame.33 Under the terms of ARPA-E’s other transaction agreement, march-in rights were modified so that if the company itself was sold, it could choose to pay the government and retain the rights to the technology developed under the agreement. Additionally, according to DOE officials, ARPA-E included a United States competitive clause in the agreement that required any invention developed under the agreement to be substantially manufactured in the United States, provided products were also sold in the United States, unless the company showed that it was not commercially feasible to do so. This agreement lasted until fiscal year 2013, and ARPA-E obligated about $9 million to it.”

Examples at DoD

“In 2011, DOD entered into a 2-year other transaction agreement with a nontraditional contractor for the development of a new military sensor system. According to the agreement documentation, this military sensor system was intended to demonstrate DOD’s ability to quickly react to emerging critical needs through rapid prototyping and deployment of sensing capabilities. By using an other transaction agreement, DOD planned to use commercial technology, development techniques, and approaches to accelerate the sensor system development process. The agreement noted that commercial products change quickly, with major technology changes occurring in less than 2 years. In contrast, according to the agreement, under the typical DOD process, military sensor systems take 3 to 8 years to complete, and may not match evolving mission needs by the time the system is complete. According to an official, DOD obligated $8 million to this agreement.”

Other interpretations of the statute have prevented DOE from leveraging OTs, and there seems to be confusion on what is allowed. For example, a commonly cited OTA explainer implies that DOE is statutorily limited to “RD&D projects. Cost sharing agreement required.”

But nowhere in the original statute does Congress require DOE to exclusively use cost sharing agreements, nor is this the case at other agencies where OTs are common practice.

However, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 did require the DOE to issue guidelines for the use of OTs 90 days after the passing of the law, and this is where it gets complicated. They did so, and according to a 2008 GAO report, DOE enacted guidelines which used a specific model called a technology investment agreement (TIA). These guidelines were modeled on the DoD’s then-current guidelines for OTs and TIAs, mandating cost sharing agreements “to the maximum extent practicable” between the federal government and nonfederal parties to an agreement.2 An Acquisition/Financial Assistance Letter issued by senior DOE procurement officials in 2021 defines this explicitly: “Other Transaction Agreement, as used in this AL/FAL, means Technology Investment Agreement as codified at 10 C.F.R., Part 603, pursuant to DOE’s Other Transaction Authority of 42 U.S.C. § 7256.” However, the DOE’s authority as codified in 42 U.S.C. § 7256 (a) and (g) does not define OTs as TIAs, the definition is just a guideline from DOE, and could be changed.

Technology Investment Agreements are used to reduce the barrier to commercial and nontraditional firms’ involvement with mission-critical research needs at DOE. They are particularly useful in that they do not require traditional government accounting systems, which can be burdensome for small or new firms to implement. But that does not mean they are the only instrument that should be used. The law says that TIAs for research projects should involve cost sharing to the “maximum extent practicable.” This does not mean that cost sharing must always occur. There could be many forms of transactions other than grants and contracts in which cost sharing is neither practicable nor feasible.

Furthermore, the DOE is empowered to use OTs for research, applied research, development, and demonstration projects. Development and demonstration projects would not fit neatly in the category of research projects covered by TIAs. So subjecting them to the same guidelines is an unduly restrictive guideline.

Consortia are basically single entities that manage a group of members (to include private firms, academics, nonprofits, and more) aligned around a specific challenge or topic. Government can execute other transactions with the consortium manager, who then organizes the members around an agreed scope. MITRE provides a longer explainer and list of consortia.

Leveraging Department of Energy Authorities and Assets to Strengthen the U.S. Clean Energy Manufacturing Base

Summary

The Biden-Harris Administration has made revitalization of U.S. manufacturing a key pillar of its economic and climate strategies. On the campaign trail, President Biden pledged to do away with “invent it here, make it there,” alluding to the long-standing trend of outsourcing manufacturing capacity for critical technologies — ranging from semiconductors to solar panels —that emerged from U.S. government labs and funding. As China and other countries make major bets on the clean energy industries of the future, it has become clear that climate action and U.S. manufacturing competitiveness are deeply intertwined and require a coordinated strategy.

Additional legislative action, such as proposals in the Build Back Better Act that passed the House in 2021, will be necessary to fully execute a comprehensive manufacturing agenda that includes clean energy and industrial products, like low-carbon cement and steel. However, the Department of Energy (DOE) can leverage existing authorities and assets to make substantial progress today to strengthen the clean energy manufacturing base.

This memo recommends two sets of DOE actions to secure domestic manufacturing of clean technologies:

- Foundational steps to successfully implement the new Determination of Exceptional Circumstances (DEC) issued in 2021 under the Bayh-Dole Act to promote domestic manufacturing of clean energy technologies.

- Complementary U.S.-based manufacturing investments to maximize the DEC’s impact and to maximize the overall domestic benefits of DOE’s clean energy innovation programs.

Challenge and Opportunity

Recent years have been marked by growing societal inequality, a pandemic, and climate change-driven extreme weather. These factors have exposed the weaknesses of essential supply chains and our nation’s legacy energy system.

Meanwhile, once a reliable source of supply chain security and economic mobility, U.S. manufacturing is at a crossroads. Since the early 2000s, U.S. manufacturing productivity has stagnated and five million jobs have been lost. While countries like Germany and South Korea have been doubling down on industrial innovation — in ways that have yielded a strong manufacturing job recovery since the Great Recession — the United States has only recently begun to recognize domestic manufacturing as a crucial part of a holistic innovation ecosystem. Our nation’s longstanding, myopic focus on basic technological research and development (R&D) has contributed to the American share of global manufacturing declining by 10 percentage points, and left U.S. manufacturers unprepared to scale up new innovations and compete in critical sectors long-term.

The Biden-Harris administration has sought to reverse these trends with a new industrial strategy for the 21st century, one that includes a focus on the industries that will enable us to tackle our most pressing global challenge and opportunity: climate change. This strategy recognizes that the United States has yet to foster a robust manufacturing base for many of the key products —ranging from solar modules to lithium-ion batteries to low-carbon steel — that will dominate a clean energy economy, despite having funded a large share of the early and applied research into underlying technologies. The strategy also recognizes that as clean energy technologies become increasingly foreign-produced, risks increase for U.S. climate action, national security, and our ability to capture the economic benefits of the clean energy transition.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has a central role to play in executing the administration’s strategy. The Obama administration dramatically ramped up funding for DOE’s Advanced Manufacturing Office (AMO) and launched the Manufacturing USA network, which now includes seven DOE-sponsored institutes that focus on cross-cutting research priorities in collaboration with manufacturers. In 2021, DOE issued a Determination of Exceptional Circumstances (DEC) under the Bayh-Dole Act of 19801 to ensure that federally funded technologies reach the market and deliver benefits to American taxpayers through substantial domestic manufacturing. The DEC cites global competition and supply chain security issues around clean energy manufacturing as justification for raising manufacturing requirements from typical Bayh-Dole “U.S. Preference” rules to stronger “U.S. Competitiveness” rules across DOE’s entire science and energy portfolio (i.e., programs overseen by the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4)). This change requires DOE-funded subject inventions to be substantially manufactured in the United States for all global use and sales (not just U.S. sales) and expands applicability of the manufacturing requirement to the patent recipient as well as to all assignees and licensees. Notably, the DEC does allow recipients or licensees to apply for waivers or modifications if they can demonstrate that it is too challenging to develop a U.S. supply chain for a particular product or technology.

The DEC is designed to maximize return on investment for taxpayer-funded innovation: the same goal that drives all technology transfer and commercialization efforts. However, to successfully strengthen U.S. manufacturing, create quality jobs, and promote global competitiveness and national security, DOE will need to pilot new evaluation processes and data reporting frameworks to better assess downstream impacts of the 2021 DEC and similar policies, and to ensure they are implemented in a manner that strengthens manufacturing without slowing technology transfer. It is essential that DOE develop an evidence base to assess a common critique of the DEC: that it reduces appetite for companies and investors to engage in funding agreements. Continuous evaluation can enable DOE to understand how well-founded these concerns are.

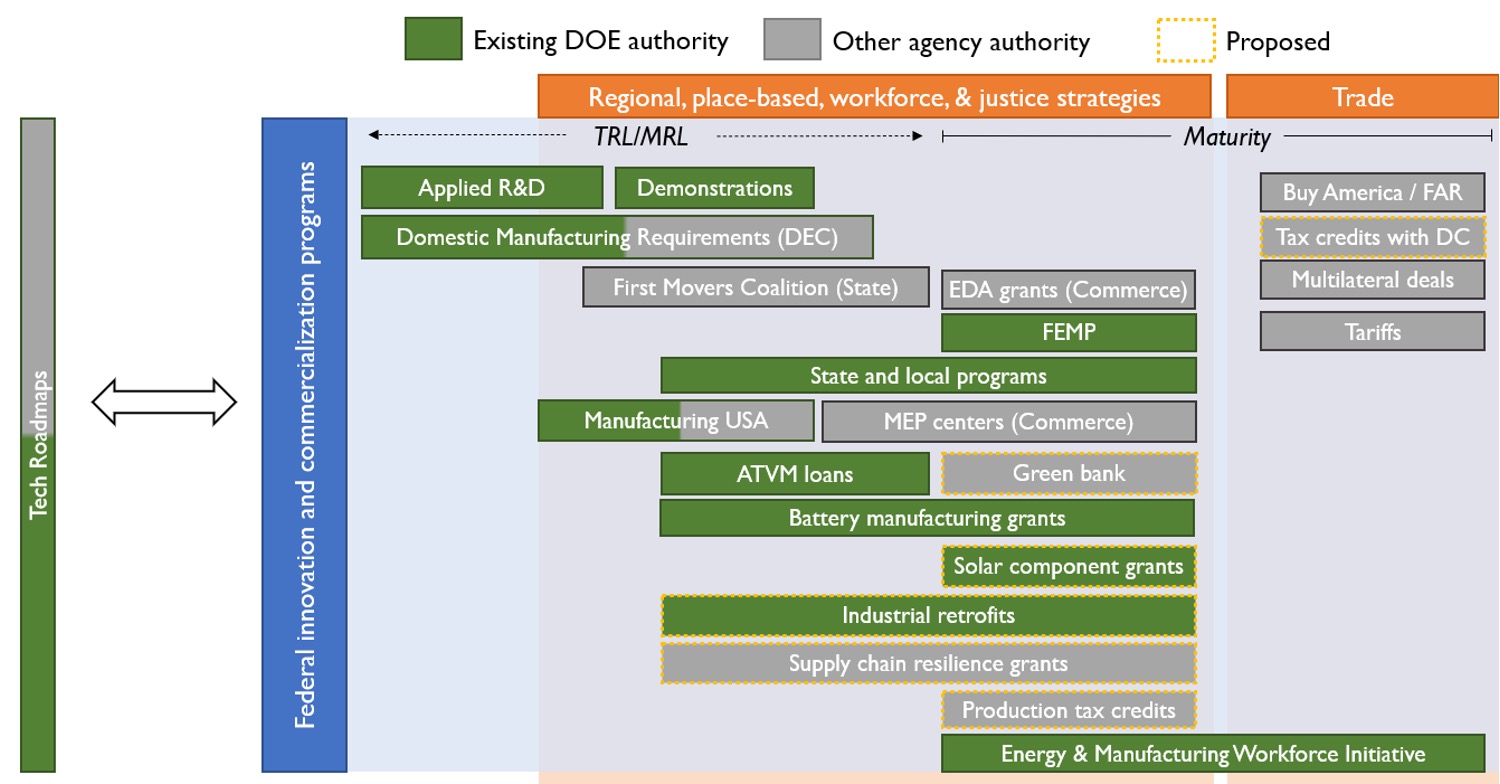

Yet, the new DEC rules and requirements alone cannot overcome the structural barriers to domestic commercialization that clean energy companies face today. DOE will also need to systematically build domestic manufacturing efforts into basic and applied R&D, demonstration projects, and cross-cutting initiatives. DOE should also pursue complementary investments to ensure that licensees of federally funded clean energy technologies are able and eager to manufacture in the United States. Under existing authorities, such efforts can include:

- Elevating and empowering AMO and Manufacturing USA to build a competitive U.S. workforce and regional infrastructure for clean energy technologies.

- Directly investing in domestic manufacturing capacity through DOE’s Loan Programs Office and through new authorities granted under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

- Market creation through targeted clean energy procurement.

- Coordination with place-based and justice strategies.

These complementary efforts will enable DOE to generate more productive outcomes from its 2021 DEC, reduce the need for waivers, and strengthen the U.S. clean manufacturing base. In other words, rather than just slow the flow of innovation overseas without presenting an alternative, they provide a domestic outlet for that flow. Figure 1 provides an illustration of the federal ecosystem of programs, DOE and otherwise, that complement the mission of the DEC.

Programs are arranged in rough accordance to their role in the innovation cycle. TRL and MRL refer to technology and manufacturing readiness level, respectively. Proposed programs, highlighted with a dotted yellow border, are either found in the Build Back Better Act passed by the House in 2021 or the Bipartisan Innovation Bill (USICA/America COMPETES)

Figure 1Programs are arranged in rough accordance to their role in the innovation cycle. TRL and MRL refer to technology and manufacturing readiness level, respectively. Proposed programs, highlighted with a dotted yellow border, are either found in the Build Back Better Act passed by the House in 2021 or the Bipartisan Innovation Bill (USICA/America COMPETES).

Plan of Action

While further Congressional action will be necessary to fully execute a long-term national clean manufacturing strategy and ramp up domestic capacity in critical sectors, DOE can meaningfully advance such a strategy now through both long-standing authorities and recently authorized programs. The following plan of action consists of (1) foundational steps to successfully implement the DEC, and (2) complementary efforts to ensure that licensees of federally funded clean energy technologies are able and eager to manufacture in the United States. In tandem, these recommendations can maximize impact and benefits of the DEC for American companies, workers, and citizens.

Part 1: DEC Implementation

The following action items, many of which are already underway, are focused on basic DEC implementation.

- Develop and socialize a draft reporting and data collection framework. The Office of the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation should work closely with DOE’s General Counsel and individual program offices to develop a reporting and data collection framework for the DEC. Key metrics for the framework should be informed by the Science and Innovation (S4) mission, and capture broader societal benefits (e.g., job creation). DOE should target completion of a draft framework by the end of 2022, with plans to socialize, pilot, and finalize the framework in consultation with the S4 programs and key external stakeholders.

- Identify pilots for the new data reporting framework in up to five Science and Innovation programs. Since the DEC issuance, Science and Innovation (S4) funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) have been required to include a section on “U.S. Manufacturing Commitments” that states the requirements of the U.S. Competitiveness Provision. FOAs also include a section on “Subject Invention Utilization Reporting,” though the reporting listed is subject to program discretion. By early 2023, DOE should identify up to five program offices in which to pilot the data reporting framework referenced above. The Office of the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4) should also consider coordinating with the Office of the Under Secretary for Infrastructure (S3) to pilot the framework in the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. Pilot programs should build in opportunities for external feedback and continuous evaluation to ensure that the reporting framework is adequately capturing the effects of the DEC.

- Set up a DEC implementation task force. The DEC requires quarterly reporting from program offices to the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation. The Under Secretary’s office should convene a task force — comprising representatives from the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT), the General Counsel’s office (GC), the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains, and each of DOE’s major R&D programs — to track these reports. The task force should meet at least quarterly, and its findings should be transmitted to the DOE GC to monitor DEC implementation, troubleshoot compliance issues, and identify challenges for funding recipients and other stakeholders. From an administrative standpoint, these activities could be conducted under the Technology Transfer Policy Board.

- Incorporate domestic manufacturing objectives into all technology-specific roadmaps and initiatives, including the Earthshots. DOE and the National Labs regularly track the development and future potential of key clean energy technologies through analysis (e.g., the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)’s Future Studies). DOE also has developed high-profile cross-cutting initiatives, such as the Grid Modernization Initiative and the “Earthshots” initiative series, aimed at achieving bold technology targets. OTT, in concert with the Office of Policy and individual program offices, should incorporate domestic manufacturing into all technology-specific roadmaps and cross-cutting initiatives. Specifically, technology-specific roadmaps and initiatives should (i) assess the current state of U.S. manufacturing for that technology, and (ii) identify key steps needed to promote robust U.S. manufacturing capabilities for that technology. ARPA-E (which has traditionally included manufacturing in its technology targets and been subject to a DEC since 2013)and the supply chain recommendations in the Energy Storage Grand Challenge Roadmap may provide helpful models.