Building Regional Cyber Coalitions: Reimagining CISA’s JCDC to Empower Mission-Focused Cyber Professionals Across the Nation

State, local, tribal, and territorial governments along with Critical Infrastructure Owners (SLTT/CIs) face escalating cyber threats but struggle with limited cybersecurity staff and complex technology management. Relying heavily on private-sector support, they are hindered by the private sector’s lack of deep understanding of SLTT/CI operational environments. This gap leaves SLTT/CIs vulnerable and underprepared for emerging threats all while these practitioners on the private sector side end up underleveraged.

To address this, CISA should expand the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) to allow broader participation by practitioners in the private sector who serve public sector clients, regardless of the size or current affiliation of their company, provided they can pass a background check, verify their employment, and demonstrate their role in supporting SLTT governments or critical infrastructure sectors.

Challenge and Opportunity

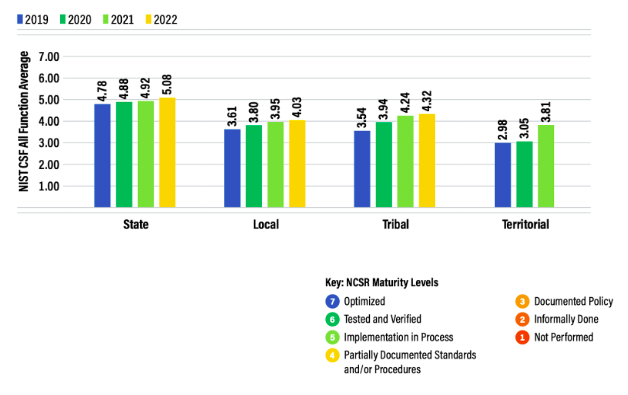

State, local, tribal, and territorial (SLTT) governments face a significant increase in cyber threats, with incidents like remote access trojans and complex malware attacks rising sharply in 2023. These trends indicate not only a rise in the number of attacks but also an increase in their sophistication, requiring SLTTs to contend with a diverse and evolving array of cyber threats.The 2022 Nationwide Cybersecurity Review (NCSR) found that most SLTTs have not yet achieved the cybersecurity maturity needed to effectively defend against these sophisticated attacks, largely due to limited resources and personnel shortages. Smaller municipalities, especially in rural areas, are particularly impacted, with many unable to implement or maintain the range of tools required for comprehensive security. As a result, SLTTs remain vulnerable, and critical public infrastructure risks being compromised. This urgent situation presents an opportunity for CISA to strengthen regional cybersecurity efforts through enhanced public-private collaboration, empowering SLTTs to build resilience and raise baseline cybersecurity standards.

Average cyber maturity scores for the State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial peer groups are at the minimum required level or below. Source: Center for Internet Security

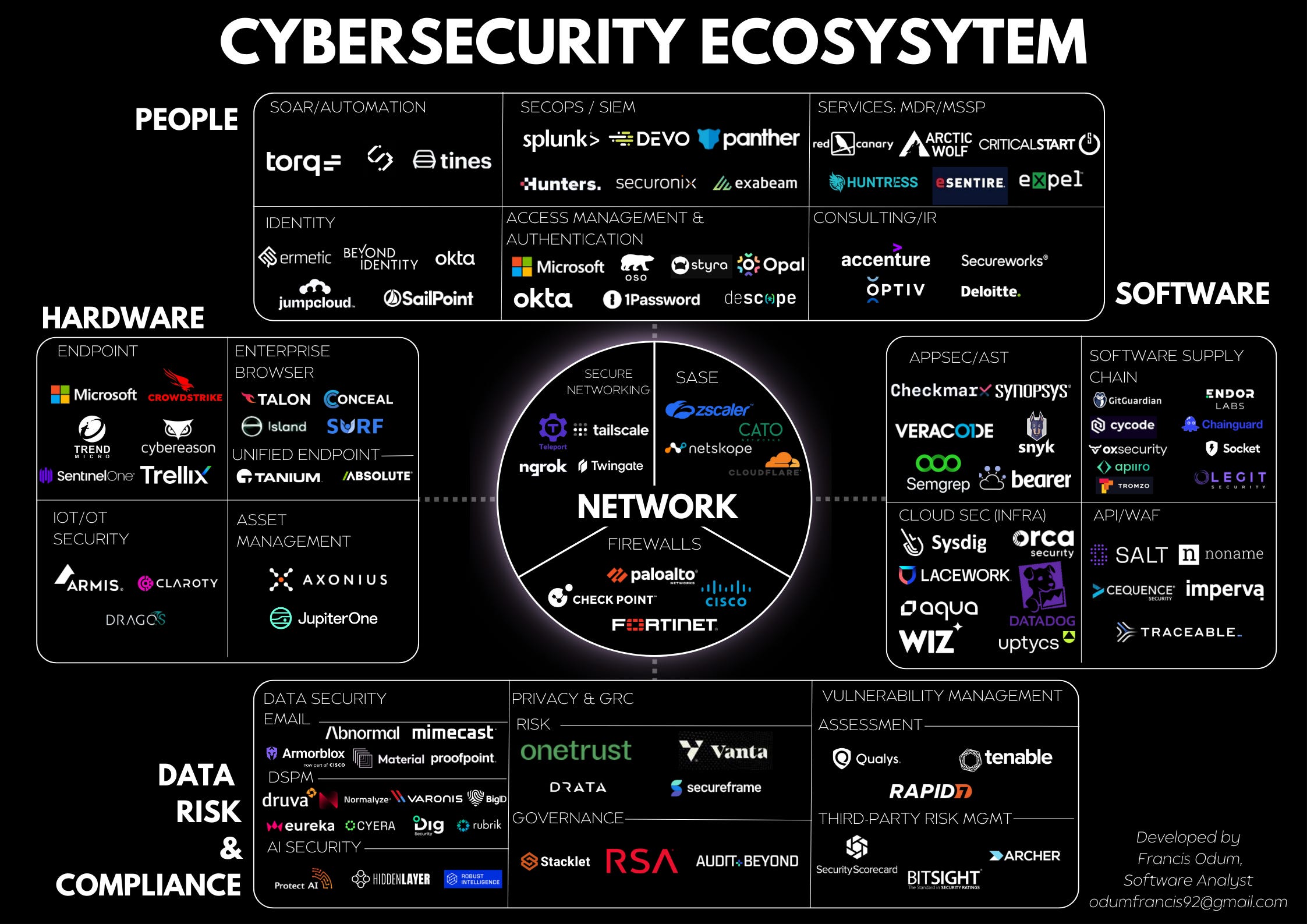

Furthermore, effective cybersecurity requires managing a complex array of tools and technologies. Many SLTT organizations, particularly those in critical infrastructure sectors, need to deploy and manage dozens of cybersecurity tools, including asset management systems, firewalls, intrusion detection systems, endpoint protection platforms, and data encryption tools, to safeguard their operations.

An example of the immense array of different combinations of cybersecurity tools that could comprise a full suite necessary to implement baseline cybersecurity controls. Source: The Software Analyst Newsletter

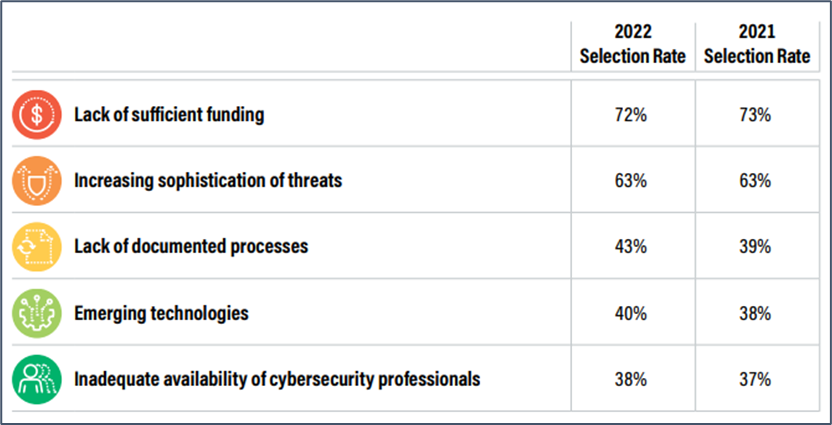

The ability of SLTTs to implement these tools is severely hampered by two critical issues: insufficient funding and a shortage of skilled cybersecurity professionals to operate such a large volume of tools that require tuning and configuration. Budget constraints mean that many SLTT organizations are forced to make difficult decisions about which tools to prioritize, and the shortage of qualified cybersecurity professionals further limits their ability to operate them. The Deloitte-NASCIO Cybersecurity Study highlights how state Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) are increasingly turning to the private sector to fill gaps in their workforce, procuring staff-augmentation resources to support security control deployment, management of Security Operations Centers (SOCs), and incident response services.

The Top 5 Security Concerns for Nationwide Cybersecurity Review Respondents include lack of sufficient funding and inadequate availability of cybersecurity professionals. Source: Centers for Internet Security.

What Strong Regionalized Communities Would Achieve

This reliance on private-sector expertise presents a unique opportunity for federal policymakers to foster stronger public-private partnerships. However, currently, JCDC membership entry requirements are vague and appear to favor more established companies, limiting participation from many professionals who are actively engaged in this mission.

The JCDC is led by CISA’s Stakeholder Engagement Division (SED) which also serves as the agency’s hub for the shared stakeholder information that unifies CISA’s approach to whole-of-nation operational collaboration. One of the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative’s (JCDC) main goals is to “organize and support efforts that strengthen the foundational cybersecurity posture of critical infrastructure entities,” ensuring they are better equipped to defend against increasingly sophisticated threats.

Given the escalating cybersecurity challenges, there is a significant opportunity for CISA to enhance localized collaboration between the public and private sectors in the form of improving the quality of service delivery that personnel at managed service providers and software companies can provide. This helps SLTTs/CIs close the workforce gap, allows vendors to create new services focused on SLTT/CIs consultative needs, and boosts a talent market that incentivizes companies to hire more technologists fluent in the “business” needs of SLTTs/CIs.

Incentivizing the Private Sector to Participate

With intense competition for market share in cybersecurity, vendors will need to provide good service and successful outcomes in order to retain and grow their portfolio of business. They will have to compete on their ability to deliver better, more tailored service to SLTTs/CIs and pursue talent that is more fluent in government operations, which incentivizes candidates to build great reputations amongst SLTT/CI customers.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Community Platform

To accelerate the progress of CISA’s mission to improve the cyber baseline for SLTT/CIs, the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) should expand into a regional framework aligned with CISA’s 10 regional offices to support increasing participation. The new, regionalized JCDC should facilitate membership for all practitioners that support the cyber defense of SLTT/CIs, regardless of whether they are employed by a private or public sector entity. With a more complete community, CISA will be able to direct focused, custom implementation strategies that require deep public-private collaboration.

Participants from relevant sectors should be able to join the regional JCDC after passing background checks, employment verification, and, where necessary, verification that the employer is involved in security control implementation for at least one eligible regional client. This approach allows the program to scale rapidly and ensures fairness across organizations of all sizes. Private sector representatives, such as solutions engineers and technical account managers, will be granted conditional membership to the JCDC, with need-to-know access to its online resources. The program will emphasize the development of collaborative security control implementation strategies centered around the client, where CISA coordinates the implementation functions between public and private sector staff, as well as between cybersecurity vendors and MSPs that serve each SLTT/CI entity.

Recommendation 2. Online Training Platform

Currently, CISA provides a multitude of training offerings both online and in-person, most of which are only accessible by government employees. Expanding CISA’s training offerings to include programs that teach practitioners at MSPs and Software Companies how to become fluent in the operation of government is essential for raising the cybersecurity baseline across various National Cybersecurity Review (NCSR) areas with which SLTTs currently struggle. The training platform should be a flexible, learn-at-your-own-pace virtual learning platform, and CISA is encouraged to develop on existing platforms with existing user bases, such as Salesforce’s Trailhead. Modules should enable students around specific challenges tailored to the SLTT/CI operating environment, such as applying patches to workstations that belong to a Police or Fire Department, where the availability of critical systems is essential, and downtime could mean lives.

The platform should offer a gamified learning experience, where participants can earn badges and certificates as they progress through different learning paths. These badges and certificates will serve as a way for companies and SLTT/CIs to understand which individuals are investing the most time learning and delivering the best service. Each badge will correspond to specific skills or competencies, allowing participants to build a portfolio of recognized achievements. This approach has already proven effective, as seen in the use of Salesforce’s Trailhead by other organizations like the Center for Internet Security (CIS), which offers an introductory course on CIS Controls v8 through the platform.

The benefits of this training platform are multifaceted. First, it provides a structured and scalable way to upskill a large number of cybersecurity professionals across the country with a focus on tailored implementation of cybersecurity controls for SLTT/CIs. Second, the badge system incentivizes ongoing participation, ensuring that cybersecurity professionals can continue to maintain their reputation if they choose to move jobs between companies or between the public and private sectors. Third, the platform fosters a sense of community and collaboration around the client, allowing CISA to understand the specific individuals supporting each SLTT/CI organization, in the case that it needs to mobilize a team with both security knowledge and government operations knowledge around an incident response scenario.

Recommendation 3. A “Smart Rolodex”

A Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system should be integrated within CISA’s Office of Stakeholder Engagement to manage the community of cyber defenders more effectively and streamline incident response efforts. The CRM will maintain a singular database of regionalized JCDC members, their current company, their expertise, and their roles within critical infrastructure sectors. This system will act as a “smart Rolodex,” enabling CISA to quickly identify and coordinate with the most suitable experts during incidents, ensuring a swift and effective response. The recent recommendations by a CISA panel underscore the importance of this approach, emphasizing that a well-organized and accessible database is crucial for deploying the right resources in real-time and enhancing the overall effectiveness of the JCDC.

Recommendation 4. Establishment of Merit-Based Recognition Programs

Finally, to foster a sense of mission and camaraderie among JCDC participants, recognition programs should be introduced to increase morale and highlight above-and-beyond contributions to national cybersecurity efforts. Digital badges, emblematic patches, “CISA Swag” or challenge coins will be awarded as symbols of achievement within the JCDC, boosting morale and practitioner commitment to the greater mission. These programs will also enhance the appeal of cybersecurity careers, elevating those involved with the JCDC, and encouraging increased participation and retention within the JCDC initiative.

Cost Analysis

Estimated Costs and Justification

The proposed regional JCDC program requires procuring ~100,000 licenses for a digital communication platform (Based on Slack) across all of its regions and 500 licenses for a popular Customer Relationship Management (CRM) platform(Based on Salesforce) for its Office of Stakeholder Engagement to be able to access records. The estimated annual costs are as follows:

Digital Communication Platform Licenses:

- Standard Plan: $8,700,000 per year (100,000 users at $7.25 per month).

CRM Platform Licenses:

- Professional Tier: $450,000 per year (500 users at $75 per month).

Total Estimated Cost:

- Lower Tier Option (Standard Communication + Professional CRM): $9,150,000 per year.

Buffer for Operational Costs: To ensure the program’s success, a buffer of approximately 15% should be added to cover additional operational expenses, unforeseen costs, and any necessary uplifts or expansions in features or seats. This does not take into consideration volume discounts that CISA would normally expect when purchasing through a reseller such as Carahsoft or CDW.

Cost Justification: Although the initial investment is significant, the potential savings from avoiding cyber incidents should far outweigh these costs. Considering that the average cost of a data breach in the U.S. is approximately $9.48 million, preventing even a few such incidents through this program could easily justify the expenditure.

Conclusion

The cybersecurity challenges faced by State, Local, Tribal, and Territorial (SLTT) governments and critical infrastructure sectors are becoming increasingly complex and urgent. As cyber threats continue to evolve, it is clear that the existing defenses are insufficient to protect our nation’s most vital services. The proposed expansion of the Joint Cyber Defense Collaborative (JCDC) to allow broader participation by practitioners in the private sector who serve public sector clients, regardless of the size or current affiliation of their company presents a crucial opportunity to enhance collaboration, particularly among SLTTs, and to bolster the overall cybersecurity baseline.These efforts align closely with CISA’s strategic goals of enhancing public-private partnerships, improving the cybersecurity baseline, and fostering a skilled cybersecurity workforce. By taking decisive action now, we can create a more resilient and secure nation, ensuring that our critical infrastructure remains protected against the ever-growing array of cyber threats.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

FAS Receives $1.5 Million Grant on The Artificial Intelligence / Global Risk Nexus

Grant Funds Research of AI’s Impact on Nuclear Weapons, Biosecurity, Military Autonomy, Cyber, and other global issues

Washington, D.C. – September 11, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has received a $1.5 million grant from the Future of Life Institute (FLI) to investigate the implications of artificial intelligence on global risk. The 18-month project supports FAS’s efforts to bring together the world’s leading security and technology experts to better understand and inform policy on the nexus between AI and several global issues, including nuclear deterrence and security, bioengineering, autonomy and lethality, and cyber security-related issues.

FAS’s CEO Daniel Correa noted that “understanding and responding to how new technology will change the world is why the Federation of American Scientists was founded. Against this backdrop, FAS has embarked on a critical journey to explore AI’s potential. Our goal is not just to understand these risks, but to ensure that as AI technology advances, humanity’s ability to understand and manage the potential of this technology advances as well.

“When the inventors of the atomic bomb looked at the world they helped create, they understood that without scientific expertise and brought her perspectives humanity would never live the potential benefits they had helped bring about. They founded FAS to ensure the voice of objective science was at the policy table, and we remain committed to that effort after almost 80 years.”

“We’re excited to partner with FLI on this essential work,” said Jon Wolfsthal, who directs FAS’ Global Risk Program. “AI is changing the world. Understanding this technology and how humans interact with it will affect the pressing global issues that will determine the fate of all humanity. Our work will help policy makers better understand these complex relationships. No one fully understands what AI will do for us or to us, but having all perspectives in the room and working to protect against negative outcomes and maximizing positive ones is how good policy starts.”

“As the power of AI systems continues to grow unchecked, so too does the risk of devastating misuse and accidents,” writes FLI President Max Tegmark. “Understanding the evolution of different global threats in the context of AI’s dizzying development is instrumental to our continued security, and we are honored to support FAS in this vital work.”

The project will include a series of activities, including high-level focused workshops with world-leading experts and officials on different aspects of artificial intelligence and global risk, policy sprints and fellows, and directed research, and conclude with a global summit on global risk and AI in Washington in 2026.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

ABOUT FLI

Founded in 2014, the Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a leading nonprofit working to steer transformative technology towards benefiting humanity. FLI is best known for their 2023 open letter calling for a six-month pause on advanced AI development, endorsed by experts such as Yoshua Bengio and Stuart Russell, as well as their work on the Asilomar AI Principles and recent EU AI Act.

Combating Malicious Cyber Acts, Penny by Penny

Updated below

The Department of the Treasury blocked one transaction by a foreign person or entity who was engaged in malicious cyber activities earlier this year, using the national emergency powers that are available pursuant to a 2015 executive order.

But the value of the intercepted transaction was only $0.04, the Department said in a new report to Congress.

No other transactions were blocked by the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) during the reporting period from March 15 to September 8 of this year, according to the Department’s latest report. See Periodic Report on the National Emergency With Respect to Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities, October 3.

Meanwhile, the cost of implementing the national emergency on malicious cyber activities was approximately $770,000 during the latest six-month period, the same report said.

Is this normal? Should Americans be concerned about the stark disparity between the amount of government expenditures and the reported proceeds? The Department of the Treasury did not respond to our inquiry on the subject yesterday. [see update below]

Background on OFAC’s Cyber-Related Sanctions Program can be found here.

Update: An official said that it would be a mistake to judge the efficacy or the efficiency of a particular sanctions program from a single periodic report, especially since these reports are not comprehensive assessments of the program.

Nor are blocked transactions the sole or primary measure of impact. Persons subject to sanctions may experience a range of other impacts, including: the disruption or loss of existing or planned contracts and other relationships with U.S. and foreign business partners; the blocking or rejection of transactions with persons outside of U.S. jurisdiction; the disruption of financial and other activities due to complementary actions taken by U.S. allies and partners; reputational damage due to the exposure of malign activities; the cost of altering and rebuilding cyber infrastructure exposed due to the imposition of sanctions; disavowal by associated governments; and loss of visas to travel to the United States and potentially to other countries.

A Forum for Classified Research on Cybersecurity

By definition, scientists who perform classified research cannot take full advantage of the standard practice of peer review and publication to assure the quality of their work and to disseminate their findings. Instead, military and intelligence agencies tend to provide limited disclosure of classified research to a select, security-cleared audience.

In 2013, the US intelligence community created a new classified journal on cybersecurity called the Journal of Sensitive Cyber Research and Engineering (JSCoRE).

The National Security Agency has just released a redacted version of the tables of contents of the first three volumes of JSCoRE in response to a request under the Freedom of Information Act.

JSCoRE “provides a forum to balance exchange of scientific information while protecting sensitive information detail,” according to the ODNI budget justification book for FY2014 (at p. 233). “Until now, authors conducting non-public cybersecurity research had no widely-recognized high-quality secure venue in which to publish their results. JSCoRE is the first of its kind peer-reviewed journal advancing such engineering results and case studies.”

The titles listed in the newly disclosed JSCoRE tables of contents are not very informative — e.g. “Flexible Adaptive Policy Enforcement for Cross Domain Solutions” — and many of them have been redacted.

However, one title that NSA withheld from release under FOIA was publicly cited in a Government Accountability Office report last year: “The Darkness of Things: Anticipating Obstacles to Intelligence Community Realization of the Internet of Things Opportunity,” JSCoRE, vol. 3, no. 1 (2015)(TS//SI//NF).

“JSCoRE may reside where few can lay eyes on it, but it has plenty of company,” wrote David Malakoff in Science Magazine in 2013. “Worldwide, intelligence services and military forces have long published secret journals” — such as DARPA’s old Journal of Defense Research — “that often touch on technical topics. The demand for restricted outlets is bound to grow as governments classify more information.”

Cybersecurity Resources, and More from CRS

A compilation of online documents and databases related to cybersecurity is presented by the Congressional Research Service in Cybersecurity: Cybercrime and National Security Authoritative Reports and Resources, November 14, 2017.

Other new and updated publications from CRS include the following.

A Primer on U.S. Immigration Policy, November 14, 2017

Defense Primer: Department of Defense Maintenance Depots, CRS In Focus, November 7, 2017

Potential Effects of a U.S. NAFTA Withdrawal: Agricultural Markets, November 13, 2017

State Exports to NAFTA Countries for 2016, CRS memorandum, n.d., October 24, 2017

Membership of the 115th Congress: A Profile, updated November 13, 2017

Drought in the United States: Causes and Current Understanding, updated November 9, 2017

Impact of the Budget Control Act Discretionary Spending Caps on a Continuing Resolution, CRS Insight, November 14, 2017

Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations, updated November 14, 2017

Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations, updated November 14, 2017

The Latest Chapter in Insider Trading Law: Major Circuit Decision Expands Scope of Liability for Trading on a “Tip”, CRS Legal Sidebar, November 14, 2017

In Any Way, Shape, or Form? What Qualifies As “Any Court” under the Gun Control Act?, CRS Legal Sidebar, November 14, 2017

Generalized System of Preferences: Overview and Issues for Congress, updated November 14, 2017

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Frequently Asked Questions, updated November 14, 2017

The Article V Convention to Propose Constitutional Amendments: Current Developments, November 15, 2017

FAS Website Blocked by US Cyber Command, Then Unblocked

For at least the past six months, and perhaps longer, the Federation of American Scientists website has been blocked by U.S. Cyber Command. This week it was unblocked.

The “block” imposed by Cyber Command meant that employees throughout the Department of Defense who attempted to access the FAS website on their government computers were unable to do so. Instead, they were presented with a notice stating: “You have attempted to access a blocked website. Access to this website has been blocked for operational reasons by the DOD Enterprise-Level Protection System.”

The basis for the Cyber Command block is unclear, and official documentation of the decision that we requested has not yet been provided. In all likelihood, it is due to the presence on the FAS website of a small number of currently classified documents that were obtained in the public domain.

The basis for the removal of the block is likewise unclear, though we know that a number of DoD employees complained about the move and advised US Cyber Command that direct access to the FAS website was needed for them to perform their job.

The record of a 2015 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee on Implementing the Department of Defense Cyber Strategy was published last month.

Cyber “Emergency” Order Nets No Culprits

In April 2015, President Obama issued Executive Order 13694 declaring a national emergency to deal with the threat of hostile cyber activity against the United States.

But six months later, the emergency powers that he invoked to punish offenders had still not been used because no qualifying targets were identified, according to a newly released Treasury Department report.

In a White House statement coinciding with the release of last year’s Executive Order, the President said that “Cyber threats pose one of the most serious economic and national security challenges to the United States, and my Administration is pursuing a comprehensive strategy to confront them…. This Executive Order offers a targeted tool for countering the most significant cyber threats that we face.”

The Executive Order authorized the Secretary of the Treasury “to impose sanctions on individuals or entities that engage in malicious cyber-enabled activities that create a significant threat to the national security, foreign policy, or economic health or financial stability of the United States.”

But although the criminal justice system has produced indictments against suspected Chinese and Iranian hackers, the President’s cyber “emergency” regime has not yielded any comparable results.

In the first periodic report on the implementation of the order, Treasury Secretary Jacob J. Lew said that “No entities or individuals have been designated pursuant to E.O. 13694.” Accordingly, the Department of the Treasury took no punitive licensing actions, and it assessed no monetary penalties, Secretary Lew wrote.

A copy of the Treasury report was obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. See Periodic Report on the National Emergency With Respect to Significant Malicious Cyber-Enabled Activities, October 1, 2015.

Even though it generated no policy outputs, implementation of the executive order nevertheless incurred costs of “approximately $760,000, most of which represent wage and salary costs for federal personnel,” the Treasury report said.

Unbeknownst to most people, there are typically multiple “national emergencies” in progress at any given time. A helpful introduction to the subject was prepared by then-CRS specialist Harold C. Relyea a decade ago.

By invoking emergency powers derived from the Constitution or from statutory law, Relyea wrote, “the President may seize property, organize and control the means of production, seize commodities, assign military forces abroad, institute martial law, seize and control all transportation and communication, regulate the operation of private enterprise, restrict travel, and, in a variety of ways, control the lives of United States citizens. [However], Congress may modify, rescind, or render dormant such delegated emergency authority.” See National Emergency Powers, updated August 30, 2007.

One other ongoing “emergency” pertains to North Korea. A Treasury Department Periodic Report on the National Emergency With Respect to North Korea, dated May 21, 2015, reveals that five financial transactions involving North Korean agents or interests — and totaling $23,200 — were blocked by executive order between December 2014 and April 2015. That’s an increase from $17,600 during the previous reporting period.

A Bureaucratic History of Cyber War

When Gen. Keith Alexander became the new director of the National Security Agency in 2005, “his predecessor, Mike Hayden, stepped down, seething with suspicion”– towards Alexander.

As told by Fred Kaplan in his new book Dark Territory, Gen. Hayden and Gen. Alexander had clashed years before in a struggle “for turf and power, leaving Hayden with a bitter taste, a shudder of distrust, about every aspect and activity of the new man in charge.” The feeling was mutual.

The subject (and subtitle) of Kaplan’s book is “the secret history of cyber war.” But the most interesting secrets disclosed here have less to do with any classified missions or technologies than with the internal bureaucratic evolution of the military’s interest in cyber space. Who met with whom, who was appointed to what position, or even (as in the case of Hayden and Alexander) who may have hated whom all turn out to be quite important in the ongoing development of this contested domain.

Kaplan seems to have interviewed almost all of the major players and participants in this history, and he has an engaging story to tell. (Two contrasting reviews of Dark Territory in the New York Times are here and here.)

Meanwhile, the history of cyber war is becoming gradually less secret.

This week, the Department of Defense openly published an updated instruction on Cybersecurity Activities Support to DoD Information Network Operations (DoD Instruction 8530.01, March 7).

It replaces, incorporates and cancels previous directives from 2001 that were for restricted distribution only.

The Federal Cybersecurity Workforce, and More from CRS

New and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service that Congress has withheld from online public distribution include the following.

The Federal Cybersecurity Workforce: Background and Congressional Oversight Issues for the Departments of Defense and Homeland Security, January 8, 2016

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): In Brief, updated January 8, 2016

American Agriculture and the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) Agreement, January 8, 2016

Cuba: Issues for the 114th Congress, updated January 11, 2016

Guatemala: One President Resigns; Another Elected, to Be Inaugurated January 14, CRS Insight, updated January 11, 2016

China’s Recent Stock Market Volatility: What Are the Implications?, CRS Insight, updated January 9, 2016

Navy John Lewis (TAO-205) Class Oiler Shipbuilding Program: Background and Issues for Congress, updated January 8, 2016

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress, updated January 8, 2016 (This report explains that “John Lewis (TAO-205) class oilers, previously known as TAO(X)s, are being named for people who fought for civil rights and human rights.” An oiler is a fuel resupply vessel that is used to transfer fuel to surface ships at sea.)

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress, updated January 8, 2016

Free Riders or Compelled Riders? Key Takeaways as Court Considers Major Union Dues Case, CRS Legal Sidebar, January 12, 2016

Unauthorized Aliens, Higher Education, In-State Tuition, and Financial Aid: Legal Analysis, updated January 11, 2016

The TRIO Programs: A Primer, updated January 11, 2016

The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016: Effects on Budgetary Trends, CRS Insight, January 11, 2016

President Obama Announces Executive Actions to “Reduce Gun Violence”, CRS Legal Sidebar, January 8, 2016

Juvenile Justice Funding Trends, updated January 8, 2016

Community Services Block Grants (CSBG): Background and Funding, updated January 8, 2016

Drones, Pope Francis, Encryption, and More from CRS

A new report from the Congressional Research Service looks at the commercial prospects for the emerging drone industry.

“It has been estimated that, over the next 10 years, worldwide production of UAS for all types of applications could rise from $4 billion annually to $14 billion. However, the lack of a regulatory framework, which has delayed commercial deployment, may slow development of a domestic UAS manufacturing industry,” the report said. See Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS): Commercial Outlook for a New Industry, September 9, 2015.

In advance of the September 22–27 visit to the United States by Pope Francis, another new CRS report “provides Members of Congress with background information on Pope Francis and a summary of a few selected global issues of congressional interest that have figured prominently on his agenda.” See Pope Francis and Selected Global Issues: Background for Papal Address to Congress, September 8, 2015.

Another new report from CRS on encryption and law enforcement presents “an overview of the perennial issue involving technology outpacing law enforcement and discusses how policy makers and law enforcement officials have dealt with this issue in the past.” See Encryption and Evolving Technology: Implications for U.S. Law Enforcement, September 8, 2015.

Other new and newly updated publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Syrian Refugee Admissions to the United States, CRS Insight, September 10, 2015

An Analysis of Efforts to Double Federal Funding for Physical Sciences and Engineering Research, updated September 8, 2015

Cybersecurity: Data, Statistics, and Glossaries, updated September 8, 2015

Cybersecurity: Legislation, Hearings, and Executive Branch Documents, updated September 8, 2015

The EMV Chip Card Transition: Background, Status, and Issues for Congress, updated September 8, 2015

Cyprus: Reunification Proving Elusive, udpated September 10, 2015

Saudi Arabia: Background and U.S. Relations, updated September 8, 2015

Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations, updated September 10, 2015

Iran Nuclear Agreement, updated September 9, 2015

Statutory Qualifications for Executive Branch Positions, updated September 9, 2015

Federal Reserve: Emergency Lending, September 8, 2015

Pentagon’s Cyber Mission Force Takes Shape

The Department of Defense plans to complete the establishment of a new Cyber Mission Force made up of 133 teams of more than 6000 “cyber operators” by 2018, and it’s already nearly halfway there.

From FY2014-2018, DoD intends to spend $1.878 billion dollars to pay for the Cyber Missions Force consisting of approximately 6100 individuals in the four military services, DoD said in response to a question for the record that was published in a congressional hearing volume last month.

“This effort began in October 2013 and today we have 3100 personnel assigned to 58 of the 133 teams,” or nearly 50% of the intended capacity, DoD wrote in response to a question from Rep. Rick Larsen (D-WA) of the House Armed Services Committee. The response was included in the published record of a February 26, 2015 Committee hearing (page 67).

The DoD Cyber Mission Force was described in an April 2015 DoD Cyber Strategy and in April 2015 testimony by Assistant Secretary of Defense Eric Rosenbach:

“The Department of Defense has three primary missions in cyberspace: (1) defend DoD information networks to assure DoD missions, (2) defend the United States against cyberattacks of significant consequence, and (3) provide full-spectrum cyber options to support contingency plans and military operations,” Mr. Rosenbach said.

“To carry out these missions, we are building the Cyber Mission Force and equipping it with the appropriate tools and infrastructure to operate in cyberspace. Once fully manned, trained, and equipped in Fiscal Year 2018, these 133 teams will execute USCYBERCOM’s three primary missions with nearly 6,200 military and civilian personnel,” Mr. Rosenbach said at an April 14 hearing of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

The new Cyber Mission Force will naturally have both defensive and offensive characteristics.

“Congressman, we are building these cyber teams… in order to, one, protect ourselves from cyber attacks,” said Adm. Cecil D. Haney, commander of U.S. Strategic Command. “We are being probed on a daily basis by a variety of different actors.”

“The protection side is one thing,” said Rep. Larsen at the February hearing of the House Armed Services Committee. “What about the other side?”

“The other aspect of it, we are distributing these forces out to the various combatant commands so that they can be integrated into our overall joint military force capability,” Adm. Haney replied.

* * *

“Worldwide Cyber Threats” was the subject of an open hearing of the House Intelligence Committee on Thursday.

The foreign intrusions suffered by U.S. government and private networks have yielded some useful lessons, said Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper.

“Of late, unauthorized disclosures and foreign defensive improvements have cost us some technical accesses, but we are also deriving valuable new insight from cyber security investigations of incidents caused by foreign actors and new means of aggregating and processing big data. Those avenues will help offset some more traditional collection modes that are obsolescent,” he told the Committee.

Cybersecurity and Information Sharing, and More from CRS

New and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Cybersecurity and Information Sharing: Comparison of H.R. 1560 and H.R. 1731, April 20, 2015

FY2016 Appropriations for the Department of Justice (DOJ), April 15, 2015

Domestic Human Trafficking Legislation in the 114th Congress, April 16, 2015

Trade Promotion Authority (TPA): Frequently Asked Questions, April 20, 2015

Mountaintop Mining: Background on Current Controversies, April 20, 2015

FEMA’s Public Assistance Grant Program: Background and Considerations for Congress, April 16, 2015

Cuba: Issues for the 114th Congress, April 17, 2015