The COVID Emergency is Almost Over—What Did We Learn About Rapid R&D?

This month marks three years since the COVID pandemic took hold of nearly every aspect of American life. In a few more months (May 2023) the coronavirus public health emergency is set to conclude officially, following the Administration’s announcement to wind down the declarations. As the nation grapples with the tragedies and lasting effects of the pandemic, it should also take lessons from the most successful elements of how the government responded to the challenge. The most notable success might be Operation Warp Speed (OWS), the highly successful public-private partnership that produced and distributed millions of live-saving vaccines in record time. Our new memo, How to Replicate the Success of Operation Warp Speed, helps this audience assess how and if they even should attempt to replicate the approach.

The Federation of American Scientists, together with our partners at 1Day Sooner and the Institute for Progress (IFP), convened leadership from the original OWS team, agency heads, Congressional staffers, researchers, and representatives from vaccine manufacturers in November 2022 to reflect on the success of the program and future applications of the model. The memo was developed primarily from notes on presentations, panel discussions, and lively breakout conversations that were both reflective and forward looking. This piece complements other analyses by providing a practical, playbook-style approach. Those looking to replicate the success of OWS should consider the stakeholder landscape and the state of fundamental science before designing a portfolio of policy interventions.

Assess the stakeholder landscape and science surrounding the challenge

A program on the exact scale of OWS will only work for major national challenges that are self-evidently important and urgent. Designers should assess the stakeholder landscape and consider the political, regulatory, and behavioral contexts. The fundamental research must exist, and the goal should require advancing it for a specific use case at scale. Technology readiness levels (TRLs) can help guide technology assessment—a level of at least 5 is a good bet. All decisions about technology readiness should be made using the best available science, data, and demonstrated capabilities.

Design an agile program by selecting a portfolio of interventions

Choose a selection of the mechanisms below informed by the stakeholder and technology assessment. The organization of R&D, manufacturing, and deployment should be inspired by agile methodology, in which planning is iterative and more risk than normal is accepted.

- Establish a leadership team across federal agencies

- Coordinate federal agencies and the private sector

- Activate latent private-sector capacities for labor and manufacturing

- Shape markets with demand-pull mechanisms

- Reduce risk with diversity and redundancy

Operation Warp Speed was a historic accomplishment on the level of the Manhattan Project and the Apollo program, but the unique approach is not appropriate for everything. Read the full memo to understand the mechanisms and the types of challenges best suited for this approach. Even if a challenge does not meet the criteria for the full OWS treatment, the five mechanisms can be applied individually to better coordinate agencies and the private sector toward solutions.

COVID-19, advanced pharmaceutical manufacturing, and the U.S. supply chain

Innovative manufacturing techniques can expand the production of drugs and medical supplies in the U.S.

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions in global supply chains, and policymakers are now strategizing around how to ramp up U.S. supply chain resiliency. Everything from beef to toilet paper became more difficult to find in U.S. stores, and the pandemic also caused dire shortages of medical supplies and lifesaving treatments. The shortages were caused by the closure of many manufacturing plants in countries like China, and our domestic supply chain was not sufficient to meet the demand gap. In fact, it is estimated that China exports more respirators, surgical masks, and other personal protective equipment than the rest of the world combined. The limited capacity of domestic supply chains – particularly for pharmaceuticals and medical supplies – was a focus for Chair Tammy Baldwin (D, WI) during last week’s Senate Appropriations Subcommittee hearing featuring testimony from Dr. Janet Woodcock, acting commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The distributed nature of modern manufacturing

The production of goods such as smartphones, medical therapeutics, or kitchen appliances is complex. Manufacturers rely on highly-trained specialists to make different components that are eventually combined into a single product. For example, the manufacture of LCD displays requires obtaining the raw materials, like glass sheets, films, semiconductor chips, and circuit connectors, from other manufacturers around the world, and assembling components inside multi-billion-dollar factories. Specialization in manufacturing allows businesses to develop new, lower-cost technologies, and more easily scale production and design processes. Unfortunately, specialization also results in a layered network of manufacturers relying on yet other manufacturers, and so on, and it becomes very difficult to determine where each component is coming from in the supply chain. The lack of visibility into this process then exacerbates disruptions in manufacturing during crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Federal partnerships to strengthen the domestic manufacturing base

To protect against future disruptions, implementing advanced manufacturing practices in domestic facilities, and encouraging businesses, particularly those that make critical drugs and medical supplies, to set up new advanced manufacturing plants in the U.S., can make a substantial impact. During last week’s hearing, Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Agriculture, Rural Development, FDA, and Related Agencies Chair Baldwin began by asking (33:05 mark in video) FDA Acting Commissioner Woodcock about how the agency is helping to strengthen domestic pharmaceutical supply chains with advanced manufacturing.

The implementation of advanced manufacturing is a top priority for the Biden Administration, and earlier this year, the FDA partnered with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to develop an advanced manufacturing regulatory framework. The partnership aims to “increase U.S. medical supply chain resilience and advanced domestic manufacturing of drugs, biological products, and medical devices through adoption of 21st century manufacturing technologies.” One emerging technology that will be explored by the partnership is the modularization of manufacturing processes. Modularization refers to structuring discrete parts of the manufacturing process in a way that they can be plugged into each other in different combinations and still function properly. With modular processes, reconfiguring the manufacturing floor to produce a different medicine or device could take just hours or days, instead of months. Another example is using artificial intelligence to track production, tweak settings to increase efficiency, and schedule maintenance to reduce the amount of downtime necessary.

In addition to FDA and NIST efforts to implement advanced manufacturing for medical supplies, two Manufacturing USA Institutes – the National Institute for Innovation in Manufacturing Biopharmaceuticals (NIIMBL) and the Bioindustrial Manufacturing and Design Ecosystem (BioMADE) – are pursuing new advanced biomanufacturing solutions. NIIMBL is a public-private partnership supported by industry and NIST to “accelerate biopharmaceutical innovation,” develop standards, and educate the biomanufacturing workforce. Advances in manufacturing processes developed by NIIMBL aid in the production of treatments for debilitating diseases like cancer, autoimmune disorders, microbial infections, and diabetes. BioMADE is one of the newest Manufacturing USA institutes, supported by the Department of Defense and industry partners. It will promote the commercialization of new biomanufacturing technologies by (i) developing predictive models to move products from the lab to production, (ii) de-risking new technologies, and (iii) manufacturing products at pilot and intermediate scales before they are produced at full scale. BioMADE would also help establish best practices for the biofabrication of novel chemicals, enzymes, and other useful biological products.

Advanced manufacturing for on-demand pharmaceuticals

There are already numerous advanced manufacturing technologies that could be leveraged to boost domestic capacity and improve U.S. self-sufficiency in the production of high-priority medicines, such as anesthetics. Building on work that is underway at the federal level, there are additional opportunities for the Executive Branch to form cross-cutting, productive partnerships. A proposal from Dr. Geoffrey Ling – former founding director of the Biological Technologies Office at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, CEO of On Demand Pharmaceuticals, and Day One Project contributor – suggests that the U.S. Government could launch a national adaptive pharmaceutical manufacturing initiative. This initiative would aim to achieve self-sufficiency for the production of medicines in the U.S. by implementing new technologies to establish high-quality and automated systems readily deployed across the country. Action steps would include fostering:

- “Targeted synthetic biology research and development to enable faster manufacturing of low-cost, on-demand vaccines and precision immunotherapies;”

- “Advanced development of green, modular, on-demand small-molecule manufacturing technologies;” and

- “New business models to support the economically sustainable domestic adoption and deployment of new manufacturing technology.”

By convening experts from the public and private sectors, as well as academia, to craft a national strategy for advanced manufacturing, and then supporting its execution, the federal government could help reduce U.S. dependence on foreign pharmaceutical and medical supply manufacturing.

Fundamental research setting the stage for advanced manufacturing

While much of the focus to implement advanced manufacturing technologies is on later-stage experimental development and commercialization, fundamental research is critical to launching these cutting-edge systems. For instance, the National Science Foundation (NSF) spent an estimated $318 million on basic manufacturing research in fiscal year 2021, and is requesting an additional $100 million in funding for its work in fiscal year 2022. In the coming fiscal year, NSF plans to sponsor research in scientific disciplines vital to advanced manufacturing, such as:

- “Highly-connected, adaptable, resilient, safe, and secure cyber-physical systems;”

- “New methods, processes, analyses, tools, or equipment for new or existing manufacturing products, supply-chain components, or chemicals and materials, including replacements for mainstay materials such as plastics that cause environmental harm;”and

- “Next-generation manufacturing infrastructure as part of a broader effort to design and renew national infrastructure.”

Today’s investments in fundamental research into manufacturing are expected to catalyze tomorrow’s breakthrough advanced manufacturing technologies.

Looking ahead

The full implementation of new developments in advanced manufacturing has the potential to ensure the resilience of U.S. medical supply chains in future crises. It can also provide other significant benefits, such as improvements in the quality of critical treatments and therapies, the creation of new jobs, and strengthening the economy. As the FDA, NIST, and other federal agencies work together, and Congress explores ways to continue supporting advanced manufacturing, we encourage the CSPI community to continue to serve as a resource to federal officials.

Improving genome sequencing infrastructure to detect coronavirus variants is a priority for CDC

As the U.S. continues to grapple with the pandemic, there are growing concerns about the risks posed by variants of SARS-CoV-2 – the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. Recent data have shown that at least one SARS-CoV-2 variant is more transmissible than the original, and there are questions as to whether any variants could be more deadly. The main way to detect emerging variants is to perform widespread genome sequencing, but the sequencing infrastructure in the U.S. is struggling to keep up with demand. This issue was a major focus of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) briefing to the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Related Agencies this week.

Origin of variants and their detection

Viruses replicate by taking advantage of a person’s own cells, and each replication introduces small changes into a virus’ genetic code. Usually, these mistakes either have no impact, or are harmful to the virus. Sometimes, though, these errors give the virus an advantage, like increased ability to infect other people. Besides increased transmissibility, it is possible that variants could also cause more severe disease, evade detection by diagnostic tests, reduce the effectiveness of treatments, escape infection-induced immunity, or render vaccines less effective.

These risks are why it is imperative that public health officials track the emergence of variants around the country, and around the globe. Variants are found by extracting genetic material from patient samples, using sequencing equipment to read the virus’ genetic code, and comparing it with other known samples. When increasing numbers of cases of disease are found to have been caused by a virus with a genetic signature that is only slightly different from that of the known samples, scientists can estimate that they may have found a new variant. For SARS-CoV-2 specifically, there are a few variants that appear to have an advantage and are able to spread much more easily than the original strain. These variants include the UK and South African strains. There are also some early data that a variant discovered in California is more contagious than the original.

Challenges for genome sequencing of viruses in the U.S.

Public health officials use genomic sequencing to monitor for a variety of viruses, but the increased demand during the COVID-19 pandemic has put the U.S.’ sequencing infrastructure under strain. Though the U.S. has over 28 million COVID-19 cases, or about one-fourth of the total number of cases in the world, only about 96,000 samples, or around 0.3 percent, have been sequenced. For U.S. labs, the sequencing process can be costly and time-consuming, taking 48 hours to readout a virus’ genome in the best case scenario, though typical turnaround times stretch up to seven days. The cost of just one virus genome sequence can be anywhere from $80 to $500.

The country’s current genomic sequencing infrastructure has not been prioritized as a public health need and, in the past, sequencing was typically performed only by research universities. In 2014, the CDC started funding public health labs to track foodborne illnesses with genomic sequencing. By 2017 every state had labs which could perform genome sequencing, but obtaining funding is still difficult.

Current efforts and the road ahead

The CDC has been working to form various partnerships to boost the U.S.’ capacity for virus genome sequencing. According to its website, CDC has focused on several activities to increase genomic sequencing capacity, including:

- Leading the National SARS-CoV-2 Strain Surveillance (NS3) system;

- Partnering with commercial diagnostic laboratories;

- Collaborating with universities;

- Supporting state, territorial, local, and tribal health departments; and

- Leading the SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology, and Surveillance (SPHERES) consortium.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky echoed this during Tuesday’s briefing and noted that under her leadership, the agency has scaled from 250 SARS-CoV-2 sequences per week to 14,000 per week. She hopes to scale up enough that the CDC can sequence 25,000 samples per week, which is close to about 5% of positive cases. To do this, the White House announced last week it would provide $200 million to support more genomic sequencing, and the U.S. Congress is considering adding almost $2 billion to that effort in the next economic relief package.

This funding is also intended to sustain the U.S.’ genomic sequencing infrastructure for the future. Senator Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), who introduced the legislation to support further sequencing, said the federal government should establish “the basis of a permanent infrastructure that would allow us not only to do surveillance for COVID-19, to be on the leading edge of discovering new variants, but also…have that capacity for other diseases.” During Tuesday’s briefing, Ranking Member Tom Cole (R-OK) affirmed this idea, saying that the House Appropriations Committee needs to think about establishing long-term funding streams to ensure that infrastructure developed during this crisis can last well in the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted gaps in U.S. infrastructure for the genomic sequencing of pathogens, and the importance of tracking virus variants for our public health. While the CDC works with its partners to rapidly scale up sequencing capacity, lawmakers need to consider how to sustain it for future outbreaks. As the Biden Administration and Congress consider scaling and sustainment, we encourage the CSPI community to serve as a resource to federal officials on this topic.

Advanced air filtration may help limit the spread of COVID-19 when combined with other protective measures

Given the pervasiveness of COVID-19 throughout the U.S., the risk of infection to transportation workers and passengers is significant. For instance, in a survey of over 600 bus and subway workers in New York City, almost one quarter reported contracting COVID-19, and 76 percent personally knew a coworker who had died from the disease. During last week’s hearing, the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee discussed best practices for protecting transportation workers and passengers from COVID-19, with a particular focus on preventing the spread of the coronavirus through the air.

Transmission of COVID-19 via aerosols

In early October 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updated its guidance, confirming that COVID-19 can be transmitted via aerosols in addition to larger respiratory droplets. When an individual with COVID-19 coughs, speaks, or breathes, tiny coronavirus-carrying droplets can travel over distances longer than six feet and stay suspended in the air for up to several hours. For the coronavirus, most transmission via aerosols occurs in enclosed, poorly ventilated spaces, when a person is exposed to respiratory particles for an extended period of time. Mass transit vehicles can be one such pathway for infection since people from different households share the same spaces while either working or riding to their destinations.

Protecting people from COVID-19 involves implementing measures to keep virus particles from entering individuals’ noses and mouths. Scientists have found that wearing a face covering can limit the amount of droplets an individual releases, and thus also reduce the amount of virus particles in the air. Masks can also provide some degree of protection to the wearer by providing a barrier between coronavirus-carrying droplets and the person’s nose and mouth. The CDC also suggests that buildings and transportation systems examine the quality of their ventilation and filtration systems to reduce spread of COVID-19. Effective ventilation quickly dilutes the amount of virus particles in the air and allows clean air to quickly circulate in enclosed spaces. Advanced filtration systems can help catch and retain virus-carrying particles on tightly woven inserts, keeping them from reentering the space. While any one of these methods alone is not sufficient to protect people from the coronavirus, a layered approach that combines many safeguards can reduce the ability of respiratory diseases like COVID-19 to spread.

Using advanced filters to remove coronavirus-carrying particles from enclosed spaces

Several Members of the Committee noted the importance of developing and implementing advanced filtration technologies on transportation systems and in buildings. Scientists estimate that the coronavirus can spread even via airborne particles under 5 microns in diameter. (For comparison, a single raindrop is typically about 2,000 microns in diameter.) Most buildings have filters with a Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) rating of between 7 and 8, which means they can filter up to 84.9 percent of particles between 3 and 10 microns in diameter. Subway cars also use these filters. The highest rated filters (MERV 16 to 20) can capture over 75 percent of particles that are between 0.3 and 1 micron in diameter, and high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, which are used on airplanes, can theoretically remove at least 99.97 percent of particles 0.3 microns in diameter and larger. To better protect workers and passengers, transportation systems like Washington, DC’s Metro and the Bay Area Transit system in San Francisco are already testing out more advanced filtration technologies through pilot programs funded by the Federal Transit Administration.

Benefits of advanced filters beyond reducing spread of COVID-19

Widespread adoption of advanced filtration technologies can be beneficial not only to reduce the amount of coronavirus-carrying particles in the air, but also to trap other harmful aerosols. During the hearing, Dr. David Michaels from George Washington University and Dr. William Bahnfleth from Penn State University both noted that investing in better filters now can also protect people from inhaling harmful particulate matter from other sources. For example, wildfires contribute about 30% of all fine particulate emissions in the U.S., with many of these being 2.5 microns or smaller. Inhaling these harmful particles can be associated with cardiovascular and respiratory issues, as well as premature mortality, particularly in vulnerable groups such as the elderly, children, and pregnant women.

Enhanced air filtration is a useful tool to help slow the spread of COVID-19, especially when used alongside other measures like wearing masks, improving ventilation, social distancing, and hand washing. As the new administration and Congress work toward ending the pandemic, practices such as the widespread adoption of more robust filters are likely to be examined in more detail. We encourage our community to get involved in the effort to counter COVID-19 by engaging in future congressional hearings through our Calls to Action.

Congressional briefing: Potential of fluvoxamine to counter COVID-19

There has been a surge of public interest in the drug fluvoxamine as a potential treatment for individuals with mild COVID-19, and Congressional offices are receiving many questions about the possibility of using the drug to counter COVID-19 from constituents. This brief outlines what is known to date about fluvoxamine in the context of the coronavirus pandemic in order to help both policymakers and scientists discuss this issue with those in their communities.

Fluvoxamine is a long-used drug that showed promising preliminary results in a small, well-controlled COVID-19 patient study

The generic drug fluvoxamine (also referred to by the brand name Luvox) was first synthesized in 1971, and is used to treat anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Fluvoxamine blocks serotonin reuptake in the brain, but it is chemically unrelated to other selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors that are used to treat anxiety or depression, like fluoxetine (Prozac) or sertraline (Zoloft). Studies have demonstrated that fluvoxamine also binds a protein in mammalian cells called the sigma-1 receptor. One of this receptor’s functions is to regulate cytokine production; cytokines cause inflammation. When fluvoxamine has been used in the laboratory, it results in a dampened inflammatory response in human cells in the test tube, and protects mice from lethal septic shock, which is an out-of-control immune response to infection, causing massive inflammation that can impede blood flow to major organs, and result in organ failure. Notably, retrospective analyses have indicated that COVID-19 patients given antipsychotic drugs that target the sigma-1 receptor were less likely to require mechanical ventilation than COVID-19 patients given other antipsychotic drugs, and some drugs that bind the sigma-1 receptor also have antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 in the petri dish.

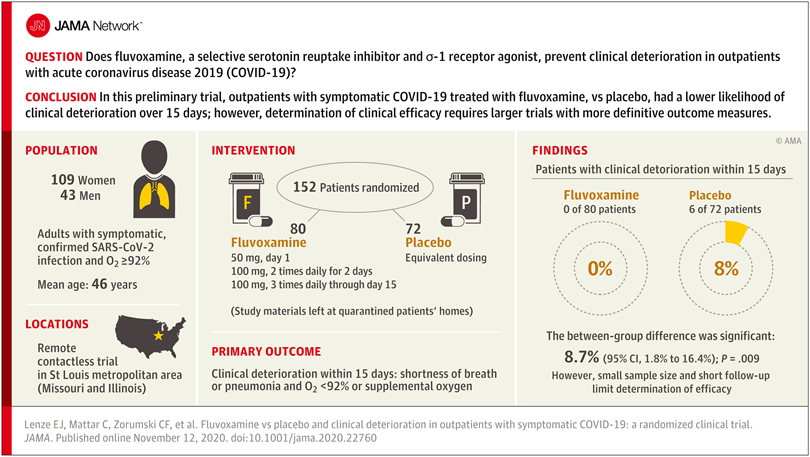

Researchers reasoned that fluvoxamine may be able to stave off the “cytokine storm” that can lead to the out-of-control inflammatory response that appears to cause severe respiratory and blood-clotting issues for some people infected with the coronavirus, and tested the drug in a pilot study to gauge whether it has potential as a treatment for COVID-19. The study was a small, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of 152 non-hospitalized adults with mild COVID-19. Treatment of symptomatic, confirmed COVID-19 patients started within 7 days of their diagnosis. None of the 80 patients treated with fluvoxamine experienced clinical deterioration, compared to 6 of 72 patients treated with placebo who experienced both “1) shortness of breath or hospitalization for shortness of breath or pneumonia and 2) oxygen saturation less than 92%.” While this amounted to a statistically significant difference, the study serves as only preliminary evidence for the efficacy of fluvoxamine as a therapy to counter COVID-19, and a much larger clinical trial has been initiated to pursue conclusive results.

Further study of treating many more COVID-19 patients with fluvoxamine is required before the drug should be used outside of clinical trials as a therapy to counter COVID-19

While the double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized design of the clinical trial does minimize bias and provide the opportunity to identify a causal relationship between treatment and patient outcome, larger randomized trials with more definitive metrics in place for assessing patients’ health status are necessary in order to reach a conclusion about whether fluvoxamine should be used to treat patients with COVID-19 outside of clinical trials. The findings of this single, small study are a launching point for larger clinical trials, and “should not be used as the basis for current treatment decisions.”

The limitations of the study include the small number of COVID-19 patients involved and the low number of patients in the placebo group whose conditions worsened – only six. And while fluvoxamine is safe, easily accessible, administered orally, and inexpensive, it may interact with other drugs, and does have some side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, loss of appetite, increased sweating, dizziness, drowsiness, insomnia, or dry mouth.

The researchers who performed this pilot study are currently conducting a larger clinical trial to conclusively determine whether fluvoxamine is an advisable treatment for mild COVID-19. The trial is expected to be watched closely since the identification of drugs – in addition to the monoclonal antibody treatments developed by Regeneron and Eli Lilly – that could be used to reduce the likelihood of progression from mild to more severe COVID-19 would greatly improve health outcomes for people infected by the coronavirus, as well as reduce the burden on the US healthcare system.

–

This briefing document was prepared by the Federation of American Scientists along with Professor Alban Gaultier at the University of Virginia and Professor David Boulware at the University of Minnesota.

Scientists take action by engaging with Congress on the promise of monoclonal antibody therapies for COVID-19

The limited science and technology (S&T) resources available to policymakers in Congress and state legislatures have compounded the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. To help meet legislators’ S&T needs, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) organized more than 60 specialists with expertise in all the different aspects of the pandemic to serve on the COVID-19 Rapid Response Task Force. In addition to providing many written briefings to Congressional and state legislative offices, members of the Task Force have so far provided three oral briefings to Congress, including one about the promise of monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies for COVID-19.

Monoclonal antibodies to counter COVID-19

Many experts believe that mAb therapies have a major role to play in protecting people from COVID-19, serving as a bridge to a vaccine, and safeguarding groups that potentially would not respond to a vaccine, for example, an aged population or immunocompromised individuals. There is certainly precedent for mAb therapies helping people survive deadly diseases; for instance, mAb therapies resulted in statistically significant survival benefits for Ebola patients.

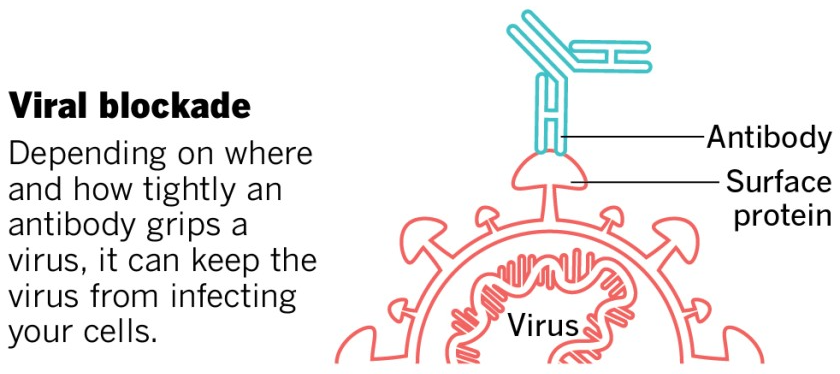

Therapeutic mAbs against COVID-19 are intended to stick to the spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2, which are on the outside of the virus, and block them from being able to attach to receptor proteins on the outside of human cells, which would be needed for viral entry and infection. Most focus has been on the spike protein interaction with the human cell surface receptor ACE2, and recent work shows that the human cell surface protein Neuropilin-1 also has a role in facilitating SARS-CoV-2 entry and infectivity in some human cell types. Designing mAb therapies that interfere with either one or both of these interactions could help explore the range of efficacies of COVID-19 mAbs.

This image was adapted from the San Diego Union-Tribune.

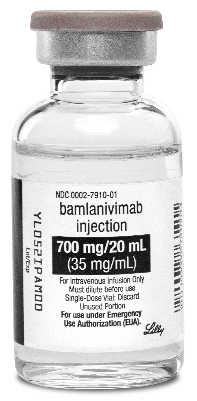

An experimental mAb from Eli Lilly being tested in early-stage clinical trials, while not appearing to help COVID-19 patients who are hospitalized (that testing has been stopped), has shown promise for people with mild or moderate COVID-19 who receive the treatment early and who are not hospitalized, reducing viral load, symptom severity, and eventual hospitalizations. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Eli Lilly’s antibody. Under the EUA, the treatment, called bamlanivimab, is supposed to be given to patients as soon as possible after a positive coronavirus test, no more than 10 days after developing symptoms. The treatment should not be used for patients who are hospitalized. It is intended for individuals 12 and older and at risk for developing a severe form of COVID-19 or being hospitalized.

Regeneron has also developed a mAb treatment, and has, like Eli Lilly, stopped its clinical trial in hospitalized patients – in Regeneron’s case, “an independent data monitoring committee warned that the risks might outweigh the benefits for hospitalised patients on high levels of oxygen.” Like Eli Lilly’s drug, Regeneron has reported that its mAB cocktail reduces virus levels in the body and improves symptoms for individuals with COVID-19 who are not hospitalized. Regeneron has also applied to the FDA for an EUA of their mAB therapy, and overall, at least ten COVID-19 antibodies are being tested in clinical trials, with many more under development.

While EUAs can serve to get drugs to patients more rapidly than going through full FDA approval, the use of mAbs outside of clinical trials can make it more difficult to ascertain the therapies’ true effectiveness in different age groups. Furthermore, it could make it harder to enroll volunteers in future clinical trials for alternative therapies, since people may want to take a drug that appears to work, rather than risk possibly getting placebo. Authorizing a low-impact therapeutic could be counterproductive. FDA must take care to only grant EUAs for mAb therapies where the data show they are potent, and clearly delineate the circumstances in which they should be administered to help patients.

Antibodies are expensive and difficult to make, and they are administered at relatively high levels. These factors conspire to limit the number of doses that are produced. By the end of the year, Regeneron is expected to have produced up to 300,000 doses of its cocktail, and Eli Lilly greater than one million. More doses are needed; experts estimate that each day, 10,000 to 15,000 people in the US would be indicated for the drugs based on age and risk factors, even if there’s no further surge of infection.

A major challenge is that manufacturing capacity for monoclonal antibodies is limited, generally actively being used to produce treatments that are needed by patients as therapies for conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, or osteoporosis. Globally, bioreactor capacity for producing mAbs from mammalian cells is spread across 200 facilities, with a total capacity of about 1,500,000 gallons. Constructing new manufacturing capacity requires years, with different types of facilities taking anywhere from 18 months to 7.5 years to come online. Bringing inactive facilities back online is a possibility, but how available such facilities are, and what would be needed to update them for operation, is unclear, and unlikely to happen in the near future. So, COVID-19 mAb manufacturing will need to rely on facilities either in use or in development, at least in the near-term.

Possible roles for government include helping to coordinate the construction of new mAb manufacturing capacity, or the repurposing of existing sites that could serve as bioreactors. Non-traditional mammalian cell lines could be tested to see which produce the highest levels of these mAbs to make the best use of the bioreactor capacity. Also, there are techniques for producing mAb therapies in bacterial or fungal (like brewer’s yeast) cells, in addition to mammalian cells, which could take advantage of existing capacity for microbial fermentation. And regulatory agencies like the Environmental Protection Agency and FDA could help expedite actions like repurposing bioreactor sites or deploying new bioproduction technologies by prioritizing the evaluation of these activities without harming the environment or sacrificing drug safety or efficacy.

Government could also assist with coordination between companies, providing a framework and forum for sharing information about or partnering on manufacturing capacity, or discussing approaches to COVID-19 mAb design that may have already been attempted and that did not pan out. This coordination could even extend to facilitating international collaborations, as COVID-19 mAb development efforts are taking place in countries all around the globe.

Considering COVID-19 is a deadly disease that can also have long-term health impacts for those who survive, the development and deployment of mAb therapies that can be administered soon after infection is detected and reduce the severity of disease are expected to contribute to countering the health effects of the pandemic.

Briefers

The experts who briefed Congress were Megan Coffee, MD/PhD, Clinical Assistant Professor at New York University; Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, Professor at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and lead of the Coronavirus Immunotherapy Consortium; Jill Horowitz, PhD, Executive Director of the Strategic Operations Laboratory of Molecular Immunology at Rockefeller University; John Cumbers, PhD, CEO of SynBioBeta; Eric Hobbs, PhD, CEO of Berkeley Lights; Jake Glanville, PhD, CEO of Distributed Bio; Mike Fisher, PhD, Senior Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists; and Ali Nouri, PhD, President of the Federation of American Scientists.For more information about FAS’ work with Congress, visit our Congressional Science Policy Initiative website.

Categories: Public Health

FDA: COVID-19 vaccine candidates should meet a higher bar for an emergency authorization than other medical products. Trump: Maybe, maybe not.

The disconnect between assurances from federal health and science agencies and President Trump’s words continues. Before Wednesday’s hearing in the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee, news broke that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has plans to implement special Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) requirements for COVID-19 vaccine candidates. The vaccine EUA requirements proposed by FDA are reported to be more stringent than those for non-vaccine products like hydroxychloroquine or COVID-19 convalescent plasma. FDA Commissioner Hahn alluded to the application of the more stringent standards in his testimony during the hearing, but later in the day the president indicated that his administration may decide to reject the FDA’s proposal.

President Trump may reject FDA COVID-19 vaccine candidate guidelines

On Wednesday, President Trump cast doubt on whether the White House would greenlight FDA’s proposed rules for evaluating COVID-19 vaccine candidates that pharmaceutical companies could submit for approval via the EUA mechanism. An EUA is a temporary clearance for medical products that can be conferred more rapidly and with less documentation than a full approval, which can take six to nine months. Standard EUAs require only that a product “may be effective,” and that the likely benefits to people outweigh the harms. In 2005, the anthrax vaccine was granted an EUA so military personnel considered at high risk of anthrax attack could receive the product, the only instance of an EUA being issued for a vaccine.

Because the vaccine would be administered to a broad population to prevent illness, as opposed to patients suffering from COVID-19, FDA has proposed to strengthen the EUA process. That proposal is now awaiting review in the White House Office of Management and Budget. In a shocking televised press conference, the president characterized the FDA proposal as a “political move.” FDA officials believe a different standard for EUAs for vaccine safety and efficacy, as opposed to EUAs for medical products like hydroxychloroquine (since revoked) and convalescent plasma, is appropriate since vaccines are given to healthy people, not to those who are sick. To earn an EUA, reports indicate the FDA plans to require clinical trial data for COVID-19 vaccine candidates that are close to what is required for a full approval. Specifically, the standards would require monitoring participants in late-stage clinical trials for a median of at least two months, starting after they receive a second vaccine shot (if the vaccine requires two shots), as well as reaching at least five severe cases of COVID-19 in the placebo group for each trial, and some cases of the disease in the elderly. Regardless, any EUA would be based on less safety data than the standard approval track, so clinical trial participants would be monitored well after an EUA, if one were to be issued.

The public will be able to evaluate FDA-reviewed COVID-19 vaccine candidates

As part of its COVID-19 vaccine candidate evaluation process, FDA plans to get the advice of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC), made up of experts in “immunology, molecular biology, recombinant DNA, virology, bacteriology, epidemiology or biostatistics, vaccine policy, vaccine safety science, federal immunization activities, vaccine development including translational and clinical evaluation programs, allergy, preventive medicine, infectious diseases, pediatrics, microbiology, and biochemistry.” These experts are screened for ethical conflicts, and are independent of both the US Government and vaccine-making companies. Notably, the VRBPAC chair recently recused herself from the review of COVID-19 vaccine candidates because she is running Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine candidate clinical trial.

FDA Commissioner Hahn, pressed by Senator Maggie Hassan (D, NH; 2:29:32 mark in video), made it clear that when a vaccine-making company either submits a COVID-19 vaccine candidate application for full approval or requests an EUA, clinical trial data and the FDA summary assessing the data will be provided to VRBPAC as well as to the entire American public. Dr. Hahn also noted that VRBPAC’s discussion, vote, and recommendations will all be public. The public will then have an opportunity to provide comments. FDA will incorporate feedback from VRBPAC into its process, and make a final decision on approval or EUA.

It is important to note, however, that the VRBPAC recommendations are not binding. In other words, the FDA commissioner, Department of Health and Human Services secretary, or possibly even the president have the authority to grant an EUA, irrespective of VRBPAC’s recommendations.

Even so, the opportunity for the entire science and medical community to review COVID-19 vaccine candidate data should help ensure that the public can learn the extent to which COVID-19 vaccine candidates are known to be safe and effective.

The outlook for COVID-19 vaccine availability

At Wednesday’s hearing, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told the Committee (2:37:41 mark in video) that if all goes well with vaccine-makers’ COVID-19 vaccine candidate clinical trials, that in November, there possibly could be 50 million doses available, about 100 million more doses in December, and roughly 700 million total doses by April. He said that the vaccines will likely be given to healthcare providers and those who are vulnerable due to underlying conditions first. However, Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a member of VRBPAC, recently told the Washington Post that “It’s hard to imagine how an [emergency use authorization] could possibly occur before December,” indicating the availability of COVID-19 vaccines in November is not certain.

FAS is tracking this situation closely; for an opportunity to contribute to oversight over the COVID-19 vaccine candidate evaluation process, click here.

Additional hearing highlights

Dr. Fauci pushes back on Senator Rand Paul in an exchange about herd immunity

Attention called to head of Operation Warp Speed’s potential conflicts of interest

More than 90 percent of Americans remain susceptible to the coronavirus

To review the entire hearing, click here.

Concerns over political interference in the COVID-19 vaccine candidate evaluation process addressed during Senate hearing

The Oval Office, biopharmaceutical executives, and federal agencies have signaled that COVID-19 vaccines could be ready to go this fall; however, leading experts believe that proof of a safe and effective vaccine before Election Day is unlikely. President Trump has said that “we can probably have [a COVID-19 vaccine] sometime in October.” Pfizer and BioNTech executives think they could know whether their joint COVID-19 vaccine candidate works by the end of October, and that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) will grant it an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) wants states ready to distribute a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as late October, with distribution sites operational by November 1st. While it is certainly important to be primed to distribute life-saving vaccines, a more realistic scenario is that thorough analyses determining the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine candidates should be possible at the very end of this year, or beginning of next year.

Nevertheless, extremely optimistic COVID-19 vaccine approval timelines that converge with Election Day are being broadcast to the American public, and during Wednesday’s Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee hearing, lawmakers demanded assurances that scientific data, not political agendas, will drive the COVID-19 vaccine approval process.

The path forward for phase III COVID-19 vaccine candidates

Three COVID-19 vaccine candidates that could be made available to Americans are currently in phase III clinical trials, and their paths forward rely on the actions that are taken by the vaccine-makers, FDA, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS, FDA’s parent agency), and the President.

Whereas vaccine candidate clinical trials have historically been designed and executed by biopharmaceutical companies alone, COVID-19 vaccine candidate trials have been overseen by the US Government. To gauge if any of the vaccine candidates prevent or decrease the severity of disease with at least 50 percent efficacy – the bar FDA set at the end of June – tens of thousands of people are being enrolled in each COVID-19 vaccine candidate phase III clinical trial. In fact, on Saturday, Pfizer proposed to FDA that it enroll up to 44,000 participants, almost 50 percent more than the initial target of 30,000. Half are dosed with the vaccine candidate, the other half are dosed with placebo, and, to prevent bias, only a select group of experimentalists – not the trial participants, not the professionals administering the doses – know who gets what. During Wednesday’s hearing, Dr. Francis Collins, the director of the National Institutes of Health, asserted (2:26:10 mark in video) that once 150 people in the entire trial have developed symptomatic disease, it should be possible to determine whether a vaccine candidate is 50 percent effective. However, some experts say that even the point at which the trial reaches 150 cases of disease is unlikely to provide enough time to prove vaccine candidate safety.

Each individual COVID-19 vaccine candidate trial is tracked by a unique Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB). DSMBs are multidisciplinary groups, independent of both the vaccine-maker and the federal government, composed of clinical trials specialists, biostatisticians, bioethicists, immunologists, vaccinologists, and virologists. As trials progress, DSMBs regularly review the data as they accumulate, and make recommendations to the company and to FDA about whether a vaccine has met safety and efficacy standards. Ultimately, DSMBs are only advisory groups, and it is up to the company as to whether it submits a Biologics License Application (BLA) to FDA for their COVID-19 vaccine candidate.

FDA will review the clinical trial data in the BLA for safety and efficacy. Following FDA’s review, the company and the FDA have the option of presenting their findings to FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC), another expert body independent of both the federal government and the vaccine-maker. If consulted, VRBPAC would provide advice to FDA regarding the safety and efficacy of the vaccine. Regardless, FDA could then approve or deny the vaccine candidate for use.

Alternatively, a vaccine-maker could request an EUA from FDA, which opens up the possibility of a vaccine being approved for use before the conclusion of the clinical trial, which could complicate the trial’s full evaluation of safety and efficacy. Another tool FDA could possibly use is Accelerated Approval, a process that could base vaccine approval only on antibody levels or another surrogate biochemical marker produced in trial participants, rather than measuring actual protection from disease. Notably, HHS, or possibly President Trump, could even overrule an FDA rejection of a request for an EUA.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, believes there would be a moral obligation to end a trial early and make a vaccine accessible if the data from the trial were to be overwhelming that the vaccine candidate is safe and effective.

Federal officials testify that COVID-19 vaccine decisions will be based only on science

During the hearing, Senator Bernie Sanders (D, VT) pressed (1:14:27 mark in video) the witnesses to affirm that the COVID-19 vaccine approval process will only be driven by science. Dr. Collins pledged that he and all US Government scientists will be basing COVID-19 vaccine candidate evaluations and assessments only on science, or else he would have no part in the process. He also expressed cautious optimism that the US will produce a safe and effective vaccine by the end of the year, adding “certainly to try to predict whether it happens on a particular week before or after a particular date in early November is well beyond anything that any scientist right now could tell you and be confident that they know what they’re saying.”

Vice Admiral Jerome Adams, the US Surgeon General, concurred with this sentiment, stating that a COVID-19 vaccine will not be moved along unless it is proven to be safe and effective, that shortcuts will not be taken, and that once approved or authorized by FDA, he and his family would not hesitate to receive the vaccine.

Will words translate into action as Election Day approaches?

Dr. Collins and Vice Admiral Adams are not the only ones giving assurances that science, not political influence, will drive COVID-19 vaccine approval. Career civil servants at FDA reiterated their resolve to working “with agency leadership to maintain FDA’s steadfast commitment to ensuring our decisions will continue to be guided by the best science.” The head of Operation Warp Speed (the US effort to accelerate COVID-19 vaccine development), Dr. Moncef Slaoui, says he will “immediately resign if there is undue interference in this process.” And nine COVID-19 vaccine-making companies have pledged to “uphold the integrity of the scientific process as they work towards potential global regulatory filings and approvals of the first COVID-19 vaccines.”

We will be tracking this issue closely as Election Day nears, and will be sure to alert the community to new developments. To review the entirety of this week’s hearing, click here.

Senate Commerce Committee homes in on consumer protection and enforcement in an era of rampant COVID-19-related scams

Consumer protection and data privacy have come into focus on Capitol Hill over the past few weeks. One week after the leaders of Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook testified in front of the House Judiciary Committee, the Senate Commerce Committee held a hearing with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) on this topic. The FTC aims to protect consumers and businesses from “anticompetitive, deceptive, and unfair business practices through law enforcement, advocacy, and education.” The hearing, titled “Oversight of the Federal Trade Commission” focused on the rise in online scams during the COVID-19 pandemic and how to make it easier for the FTC to protect consumers. The senators’ discussion with the FTC chair and commissioners was informed by expert questions provided by the Day One Project, a science and technology policy project that is developing policy proposals for the next Administration. These questions focused on how the FTC plans to keep up with the consumer risks brought by rapidly changing technology, especially from the major tech companies, and risks brought on by scams from current events, such as the pandemic.

There are numerous scams related to COVID-19 and they can be hard to detect. They range from price gouging and selling defective products to people pretending to be contact tracers, those who claim to provide “miracle” cures, and callers pretending to be from the U.S. government. According to the FTC, these pandemic-related scams have cost Americans over $13 million this year and this number is only growing. Out of the 100 million phishing emails blocked by Google each day, it is estimated that about 18 million of them reference the coronavirus. Others attempt to market products that claim to cure COVID-19, like colloidal silver (tiny silver particles suspended in a liquid), which are actually harmful to one’s health.

To combat these scams, the FTC has produced detailed guidance for businesses and consumers. However, enforcement of consumer protection rules can be challenging. Specifically, the FTC’s regulations have not kept up with an evolving internet landscape and scams take advantage of this. Commissioner Rebecca Slaughter acknowledged (1:21:08) that, especially in cases of price gouging, the FTC’s current oversight abilities are an “imperfect tool.”

Typically when a business or individual is caught using predatory tactics on consumers, the FTC sends out a warning letter. The goal of these letters is to notify the business or individual that they are violating consumer protection rules in the Federal Trade Commission Act. They also threaten legal consequences, such as a federal lawsuit, if the predatory behavior continues. The FTC has sent hundreds of letters to companies making misleading claims about COVID-19 treatments and cures, including those pushing treatments with ozone, vitamin C, 5G shields, and ultraviolet light. FTC Chair Joe Simons notes (1:49:25) that these letters tend to be effective. However, Senator Richard Blumenthal (D-CT) expressed (1:50:35) how it would be easier to combat scams if there was a judgement on the books after the first instance of predatory behavior instead of having to wait until the second occurrence to implement harsher punishments.

Through its work in this area, the Day One Project emphasized that FTC’s penalty structure may not provide proper incentives to deter businesses from engaging in predatory tactics or unfair practices in consumer privacy and protection. Experts working with the Day One Project suggested that new regulations could help. During the hearing, Chair Simons and Commissioner Noah Philips agreed and explained (1:32:50 and 2:34:15, respectively) that allowing the FTC to have targeted rulemaking capabilities and the ability to levy civil penalties can help combat scams and protect consumers’ data. This rulemaking authority would allow the FTC, according to Chair Simons, to change its definitions to “account for changes in technology and changes in business methods.”

While this targeted rulemaking authority would need to be passed by Congress, the members of the committee were receptive to the idea. The consumer protection and data privacy landscape is changing rapidly over time and businesses taking advantage of an unprecedented pandemic threaten the security and wellbeing of consumers every day. It is clear from this hearing that FTC is trying its best to combat these threats but needs more help to do so. Input from forward-leaning organizations like the Day One Project are vital to ensure that Congress is informed about the most pressing issues and has the tools it needs to solve them. This will likely not be the last hearing on this topic and the Congressional Science Policy Initiative encourages its readers to get involved in the policymaking process to help Congress protect citizens from predatory business practices.

More information can be found about the Day One Project here: https://www.dayoneproject.org/about.

To get involved with science policy and the U.S. Congress, sign up here: https://fas.org/congressional-science-policy-initiative/.

Hopes are high for safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines to be available in the fall, but the specter of political pressure looms

Come Tuesday, November 3rd – Election Day – Americans will exist in one of two realities: One reality in which COVID-19 vaccines deemed safe and effective are available to the electorate, or a different reality in which vaccines are still unavailable. Biopharma companies are optimistic their COVID-19 vaccines could be available as early as the fall. At the same time, Congress is concerned political interference from the White House could result in the approval of substandard vaccines. This tension was on full display at yesterday’s House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations hearing featuring leaders from COVID-19 vaccine-makers AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson (J&J), Merck, Moderna, and Pfizer.

The prospect of political interference in COVID-19 vaccine availability

If all goes well, there could be millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses ready to be distributed to Americans this fall. AstraZeneca may have hundreds of millions of doses available as soon as September. Moderna has its sights set on having millions of doses produced by the fall. Pfizer could provide 100 million doses by the end of this year. These hopes are contingent on these companies’ vaccines proving safe and effective in phase three trials involving tens of thousands of people.

But what if US safety and efficacy standards are adjusted, or even disregarded, to serve political interests? That’s the concern Representative Frank Pallone (D, NJ-06), chair of the full committee, raised with the five officials from vaccine-making companies.

At the end of June, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) established guidance for the approval of COVID-19 vaccines. The guidance states that any vaccine must prove at least 50 percent more effective for COVID-19 prevention when compared against placebo. (The flu vaccine varies between 40 and 60 percent efficacy from one year to another.) Efficacy of 50 percent or more for a COVID-19 vaccine must be shown in a clinical trial enrolling at least 30,000 people of all different races and ethnicities.

Chair Pallone raised the possibility that President Trump could pressure FDA to lower official COVID-19 vaccine standards to well below 50 percent efficacy, or to surreptitiously approve a vaccine even if a company’s internal data show it’s less effective than FDA’s public requirements. The Chair was looking for assurances from the vaccine-makers that they will help guard against possible political interference from the White House. Dr. Mene Pangalos, AstraZeneca’s executive vice president of biopharmaceuticals research and development, stressed that all his company’s clinical data will be published openly, and that since the vaccine will be marketed globally, it will be vetted by many countries’ regulators, in addition to FDA. Moderna’s president, Dr. Stephen Hoge, also committed to publishing his company’s data regardless of whether the vaccine succeeds in clinical trials, and added that independent investigators on a National Institutes of Health (NIH) Data Safety Monitoring Board are conducting oversight of Moderna’s trials. Even so, White House influence on FDA is expected to be monitored closely as the US heads toward Election Day.

The White House has not shied away from pressuring federal agencies responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Earlier this month, President Trump undermined Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines for reducing the risk of spreading COVID-19 at schools. In May, the Administration shelved CDC recommendations “with step-by-step advice to local authorities on how and when to reopen restaurants and other public places.” In April, a research grant funding the study of coronaviruses’ transmission from bats to people was terminated because the White House told NIH to cancel it. And finally, FDA is not immune to pressure from the Administration: A whistleblower alleges the since-rescinded emergency use authorization permitting treatment of COVID-19 patients with hydroxychloroquine was granted as a result of political interference, and there is evidence FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn took unusual steps to assist a New York medical doctor in obtaining the drug. Congress finds the possibility of political interference from the White House in FDA’s COVID-19 vaccine approval process very worrisome.

Keys to expediting vaccine-making

Vaccines are rarely developed in even less than five years. The development of a safe and effective vaccine and the beginnings of its distribution in less than a year since the emergence of a novel disease would be revolutionary. To expedite COVID-19 vaccine-making, three key tactics have been implemented.

For one, bureaucratic steps are being streamlined to move the vaccine testing process along faster. Unnecessary delays between trial phases have been eliminated, while rigorous studies on vaccine safety and effectiveness have been maintained.

Second, some “plug-and-play” technologies developed in prior vaccine work have been applied to SARS-CoV-2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19). For example, Moderna’s vaccine development platform had been used previously to produce influenza virus and Zika virus vaccine candidates, and during the hearing, J&J’s Janssen Vaccines head of clinical development and medical affairs, Dr. Macaya Douoguih, cited her company’s accelerated program that produced an Ebola vaccine as critical to J&J’s efforts to produce 100 million COVID-19 vaccine doses by March 2021.

And third, companies are already scaling up the manufacture of potential COVID-19 vaccines in parallel with the testing phases, so that if a COVID-19 vaccine candidate proves successful in trials, millions of doses will be immediately available. Called at-risk manufacturing – if vaccine candidates do not pass muster, millions of doses would be worthless – vaccine-makers are implementing this capital intensive tactic because of the urgent need for safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines to be available for protection of the public.

Vaccine-makers are optimistic that tens of millions of COVID-19 vaccine doses will be available by the end of this year; however, the US government’s plan for fair and equitable vaccine distribution is yet to be released. CDC has the lead on planning for COVID-19 immunization infrastructure and vaccine distribution to the American people, and the Department of Defense is supporting CDC on logistics. Ensuring all Americans can be vaccinated against COVID-19 demands intensive local-state-federal coordination, as well as cooperation between the public and private sectors. While biopharma companies continue their rapid pursuit of vaccines against COVID-19, there is good reason for both hope and vigilance.

To review the full House Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations hearing, click here.

US vaccine manufacturing capacity assessed at Senate HELP Committee hearing

At the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee hearing on Tuesday, Members of Congress and witnesses evaluated whether the U.S. will be able to manufacture enough COVID-19 vaccines to protect the population, as well as be able to distribute them equitably. Vaccine manufacturers are racing to increase their capacity to produce what will likely be billions of doses, but it might take months to years from when the vaccine is approved to produce enough doses to vaccinate the number of people necessary (about 70% of the world’s population) to achieve herd immunity.

Infrastructure for producing vaccines

Committee Chair Lamar Alexander (R, TN) asked witnesses for recommendations on what type of manufacturing capacity the federal government should have on hand to produce and distribute doses of a potential COVID-19 vaccine. Former Governor of Utah Michael Leavitt explained (1:03:30) that while the infrastructure exists to scale up U.S. vaccine manufacturing capacity, the plants were not effectively maintained after they were built. Additionally, maintaining such manufacturing facilities costs a significant amount of money, and, prior to the pandemic, pharmaceutical companies were reluctant to spend so much on facilities that are specific to only one vaccine, which may not ultimately be approved or sold.

Dr. Julie Gerberding, Executive Vice President of Merck & Co., added (1:05:00) that most pharmaceutical companies manufacturing large quantities of vaccines are nearly at capacity producing doses of other vaccines, such as those for the flu. Moderna’s CEO, Stephane Bancel, who is overseeing one of the leading experimental COVID-19 vaccine efforts, mentioned this problem in a May 12 interview with CNBC. He stated, “The odds that every [vaccine] program works are really low, obviously, but I really hope we have three, four, five vaccines, because no manufacturer can make enough doses for the planet.” To put this in perspective, pharmaceutical companies estimated they provided between 162 to 169 million doses of the flu vaccine for the U.S. during the 2019-2020 flu season. To protect the U.S. population from COVID-19, about 230 million Americans would have to be vaccinated. This also does not account for the possibility that each person may need multiple doses to be fully vaccinated or the fact that many manufacturers in the U.S. supply vaccines to other countries.

Besides overall capacity, one of the largest challenges is that the manufacturing infrastructure will differ depending on which type of vaccine(s) are the most effective. The vaccines may need to be produced by processes requiring large vats of cells or other organisms, such as tobacco plants. If a successful vaccine is based on inactivated virus, vaccine production might require highly secure facilities, of which there are very few. This means that until one or more vaccine candidates are closer to being approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), vaccine manufacturers will have a difficult time tailoring their existing facilities, or building new ones, that have the necessary equipment ready to produce the vaccines.

Some pharmaceutical companies are relying on public-private partnerships to develop and scale their vaccines, such as Johnson & Johnson with the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). These flexible agreements allow the federal government to help the pharmaceutical companies invest money and talent into the most promising vaccine candidates. They also make it possible for companies to overhaul their production facilities and build new ones to accommodate the new vaccines, a complex and costly process for these organizations by themselves.

Equitable distribution of a potential COVID-19 vaccine

Even if companies are able to develop and produce enough doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, there are concerns that the doses may not be distributed equitably among the global population. For example, during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, Australia was the first to manufacture a vaccine but did not export it immediately because it wanted to inoculate its citizens first. Additionally, wealthier countries have the advantage of being able to purchase large quantities of vaccines at much higher rates than countries with fewer resources.

However, even in wealthy countries like the U.S., care must be taken to ensure that vaccines get to the country’s most vulnerable communities. The pandemic has devastated minority communities in cities across the country due to deep-seated public health disparities. Dr. Joneigh Khaldun, Chief Medical Executive for the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services, noted (1:06:40) during her testimony that people of color are more likely to be impoverished and more likely work in occupations that are deemed essential, but they also have the least access to healthcare. Both Dr. Khaldun (45:25) and former Governor Leavitt (40:20) emphasized that the U.S. should develop a national procurement and distribution strategy not only to reduce the competition for vaccines, but also competition for supplies in future pandemics.

Currently, pharmaceutical companies are working to adapt their vaccine manufacturing facilities to accommodate the production of the large number of doses that will be needed to protect against COVID-19, but they have a long way to go. As Chair Alexander noted (2:50:00), Congress will be reviewing the U.S. response to COVID-19 regularly, so stay tuned for more opportunities to engage with Capitol Hill.

To review the full hearing, click here.

Much-needed supplies for responding to COVID-19 remain limited

Unlike countries such as South Korea, New Zealand, or Germany, the US has not controlled the spread of COVID-19 in a coordinated fashion, and the nation is in danger of a second surge of cases. Some experts already see indicators of the second surge. For instance, COVID-19 hospitalizations rose sharply in several states after Memorial Day, and the percentage of COVID-19 tests that are positive is rising in some parts of the country. Tragically, more than 113,000 Americans have died from COVID-19, about a quarter of all deaths reported globally. This week’s Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing examined key aspects of US preparedness for a second surge of COVID-19.

Status of US availability of medical supplies

From mid March through April, when COVID-19 was first on the rise throughout the country – with cases especially surging in New York City and New Jersey – there were shortages of almost every COVID-19-related medical supply imaginable. N95 respirator masks. Face shields. Cleaning supplies. Drugs for patients on ventilators. Swabs for COVID-19 tests. States scrambled to obtain much-needed supplies, sometimes forced into bidding against one another. This was all due to the combined impacts of the sudden worldwide surge in demand for these goods, deficiencies with US caches of emergency supplies, domestic distribution issues, and a lack of timely, decisive, evidence-based leadership in the White House.

The US should have been ready for the intensified needs brought on by the pandemic, with the health security community recommending for many years that more resources be dedicated to infectious disease preparedness and response, but unfortunately, the country was caught flat-footed. The White House COVID-19 Supply Chain Task Force’s own estimates of US personal protective equipment (PPE) needs and availability – made public because Senator Maggie Hassan (D, NH) pressed the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to release them during the hearing – show US supplies of N95 respirator masks, surgical masks, gowns, and nitrile gloves not meeting demand in March, April, and May. Moving forward, the Task Force projects that beginning in July for N95 respirator masks, surgical masks, and gowns, and beginning this month for nitrile gloves, supply will meet demand for hospitals, long-term care facilities like nursing homes, first responders, and janitorial, laboratory, and correctional workers.

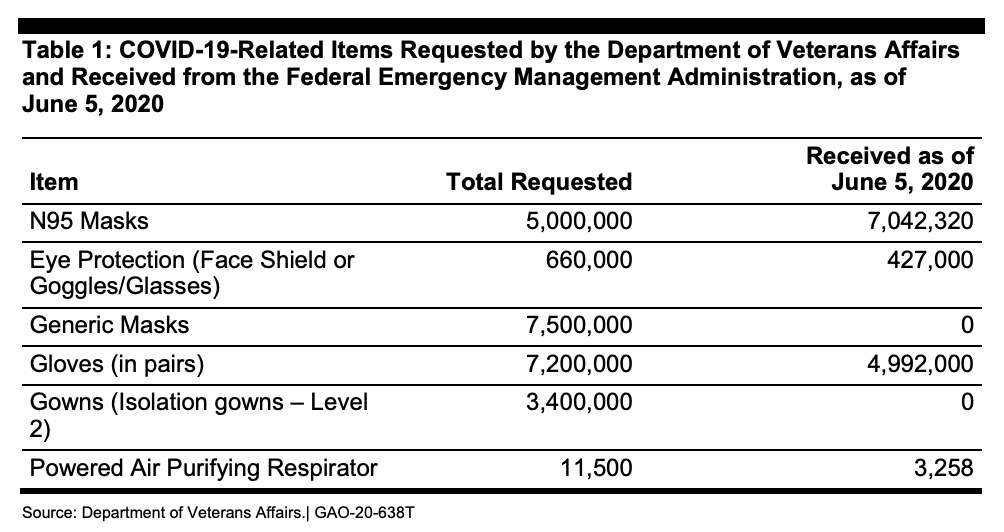

But America’s PPE supply is in flux, and there are clearly inadequacies. For example, the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) says it needs a six-month supply of PPE to handle a second surge of COVID-19. At the height of the initial surge, the VA’s 170 medical centers were using 250,000 N95 respirator masks every day. Right now, the VA only has about a 30-day supply of PPE, and as of June 5th, the VA had not received any of the 7.5 million “generic masks,” nor any of the 3.4 million “isolation gowns,” it had requested from FEMA’s Strategic National Stockpile program back in mid-April.

Strategic National Stockpile

The Strategic National Stockpile was intended to be America’s fallback plan. Through April 1st (the Administration changed the wording on April 2nd), the stockpile was defined as

“…the nation’s largest supply of life-saving pharmaceuticals and medical supplies for use in a public health emergency severe enough to cause local supplies to run out. When state, local, tribal, and territorial responders request federal assistance to support their response efforts, the stockpile ensures that the right medicines and supplies get to those who need them most during an emergency. Organized for scalable response to a variety of public health threats, the repository contains enough supplies to respond to multiple large-scale emergencies simultaneously.”

The stockpile was initially launched in 1999 and managed by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2018, responsibility for the stockpile shifted to the HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response (ASPR). In March, responsibility for the stockpile shifted again, this time to FEMA.

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, the stockpile did not offer much resilience. Government officials estimated that the US would require 3.5 billion N95 respirator masks for a severe outbreak. There were only 12 million unexpired N95 respirator masks in the stockpile in February. In early March, the stockpile contained only 16,600 ventilators, and on April 3rd, the federal government had just 9,800 ventilators available. It is unlikely that the stockpile is being replenished since PPE that becomes available is generally immediately put to use in COVID-19 hot spots or delivered to medical centers, and it is difficult to gain insight into the current inventory of the stockpile. For instance, after not receiving a response to their Freedom of Information Act request, ProPublica filed a lawsuit against the Administration to get medical stockpile records.

A group of nine former presidential science advisors warned that the US needs to build the stockpile back up by September 1st in order to be prepared for a possible COVID-19 resurgence in the fall, and that state and local supply inventories need to be stocked as well. Their recommendations revolve around increased funding for producing essential medical goods, stockpiling supplies, and improving the coordination of the supply chain and distribution.

Moving forward through the pandemic

During the hearing, the vice director of logistics for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Rear Admiral John Polowczyk, testified that the US is ramping up domestic production of at least some critical medical supplies. Polowczyk cited the current capacity to manufacture 180 million N95 respirator masks each month, his expectation for the production of an adequate number of reusable gowns by the fall, the beginnings of at least some nitrile glove manufacturing (compared to essentially zero previous domestic capacity), and initiating the process of onshoring the making of some ventilator drugs.

Despite these signs of progress, at the moment, the US does not appear ready for another surge of coronavirus. And that surge may come sooner rather than later.