Tracking AI Provisions in FY 2024 Appropriations Bills

As Congress moves forward with the appropriations process, both the House and Senate have proposed various provisions related to artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) across different spending bills. These proposals reflect the growing importance and adoption of AI/ML technologies across many areas of government.

Below we summarize AI/ML provisions for each appropriations bill in tables comparing the Senate and House versions. Tables include:

- Provision: Describes the AI/ML provision at a high level.

- Senate/House Summary: Summarizes the AI/ML language in the Senate or House bill for this provision. “N/A” indicates no related language.

- Status: Shows how far this provision has progressed in the legislative process.

- Page: Indicates where in the Senate or House bill report this provision appears, with page numbers. “S.” and “H.” indicate whether it is the Senate or House report, respectively.

Both chambers provide significant funding increases for AI research at science agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Department of Energy (DoE)’s Office of Science. For example, the Senate recommends $135 million for AI initiatives across DoE’s Office of Science, while the House includes $20 million for NSF to research AI explainability. NIST sees a $68 million funding increase in the Senate bill for its measurement labs and research, and a $15 million increase in the House.

The provisions overall seem focused on practical AI applications and boosting research, rather than ideological battles. The language in both chambers’ bills is framed in terms of maintaining US leadership and competitiveness, which tends to avoid partisan divisions. The House justifies more of its spending on AI in tones that are hawkish toward China. The Senate bills tend to have more congressionally directed spending items, or earmarks, related to AI.

Both bills demonstrate interest in AI applications like agricultural forecasting, autonomous vehicles, and utilizing AI to modernize government operations. But the Senate more explicitly directs agencies to adopt AI to improve such programs, and in some cases, such as NIST funding, the Senate is more fiscally generous. Overall, the Senate bill reports and bill summaries are more specific in the language and observations around AI, with 65 provisions related to AI or machine learning, compared to 44 in the House, across all appropriations bills. This potentially reflects a somewhat higher level of interest within the Senate Appropriations committee on the topic.

While both chambers agree on boosting AI research funding, the Senate takes a more top-down approach prescribing funding for AI initiatives while the House allows more agency discretion. Differences also emerge regarding perspectives on AI oversight and governance. Clearly, there will be a lot of coordination needed to align on AI funding priorities when (and if) these bills go to conference.

This tracker will be updated as the appropriations process continues.

Agriculture

- Senate: Passed Senate 11/1/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House Appropriations 6/14/23, failed on House floor 9/28/23. Bill Report.

Commerce, Science & Justice

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/13/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House Appropriations 7/14/23. Bill Summary. Explanatory Materials.

Energy & Water Development

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/20/23. Bill Summary. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House 10/26/23. Bill Report.

Financial Services & Government

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/13/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House Appropriations 7/13/23. Bill Report.

Homeland Security:

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/27/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House 9/28/23. Bill Summary. Bill Report.

Interior & Environment

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/27/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed full House 11/3/23. Bill Report.

Labor, HHS & Education

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/27/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House Appropriations Subcommittee 7/14/2023. No Bill Report published.

Legislative Branch

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/13/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House 11/1/23. Bill Report.

Military Construction & VA

- Senate: Passed Senate 11/1/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House 7/27/23. Bill Report.

State & Foreign Operations

- Senate: Passed Senate Appropriations 7/20/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House 9/28/23. Bill Report.

Transportation & HUD

- Senate: Passed Senate 11/1/23. Bill Report.

- House: Passed House Appropriations 7/18/23. Bill Report.

A Push to Elevate Open Source Intelligence

Open source intelligence — which is derived from open, unclassified sources — should be recognized as a mature intelligence discipline that is no less important than other established forms of intelligence, the House of Representatives said last month in the FY 2022 defense authorization act (sec. 1612).

The House directed the Secretary of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence to develop and implement “a plan to elevate open-source intelligence to a foundational intelligence for strategic intelligence that is treated on par with information collected from classified means (for example, human intelligence, signals intelligence, and geospatial intelligence).”

Considering that those classified disciplines have large dedicated agencies of their own (CIA, NSA, NGA), it would seem to be a major undertaking to “elevate” open source intelligence to the same level and to treat it comparably.

Significantly, the House directive is driven not by some abstract preference for open sources but by “the intelligence priorities of the commanders of the combatant commands.” The thinking appears to be that open source intelligence — that can be shared widely or even (sometimes) publicly disclosed — offers practical advantages to military commanders that other, highly classified forms of intelligence typically lack.

A related sign of dissatisfaction with unchecked military secrecy can be found in another provision of the House authorization bill that would require the Space Force to “conduct a review of each classified program . . . to determine whether the level of classification of the program could be changed to a lower level or the program could be declassified.”

In recent years, open source intelligence has been managed by the elusive Open Source Enterprise (OSE) which is administratively housed at the Central Intelligence Agency. To the bewilderment and frustration of many users, the OSE decommissioned its own website in 2019 and made its products exceptionally difficult to access.

In response, last year’s intelligence authorization act (sect. 326) required a plan “for improving usability of the OSE” as well as other steps to enhance the utility of open source collection for intelligence. But so far, there is no externally visible sign of any change for the better.

Earlier this year, the CIA denied a Freedom of Information Act request for an unclassified OSE publication on North Korean ballistic missile tests. The CIA did not dispute that the document is unclassified, but it said the report was exempt from disclosure anyway. An appeal of the denial is pending.

The US military’s interest in open source intelligence is longstanding and arguably dates back to colonial times. The Army’s Military Intelligence Professional Bulletin devoted an issue to the subject in 2005.

A 2006 Army Field Manual (since superseded) presented interim doctrine on the collection of open source intelligence.

New Declassification Reforms Are Classified

Legislative measures to improve the process of declassifying classified national security information were introduced by Sen. Ron Wyden in the pending intelligence authorization act for FY2022. But they were included in the classified annex so their substance and import are not publicly known.

“I remain deeply concerned about the failures of the Federal Government’s obsolete declassification system,” Sen. Wyden wrote in a statement that was included in the new Senate Intelligence Committee report on the intelligence bill. “I am therefore pleased that the classified annex to the bill includes several amendments I offered to advance efforts to accelerate declassification and promote declassification reform.”

But the nature of those amendments has not been disclosed. “As absurd as it is to be opaque about the topic of declassification I’m afraid I can’t tell you more right now,” a Committee staffer said. “Sorry.”

“Putting aside the irony of declassification amendments found only in a classified annex, I can confirm that we’re tracking it,” said an intelligence community official.

It requires some effort to think of declassification reforms that could themselves be properly classified. The idea seems counterintuitive. But there are agency declassification guides that are classified because they detail the precise boundaries of classified information. And any directive to declassify an entirely classified topical area would have to begin by identifying the classified subject matter that is to be declassified.

“True perfection seems imperfect,” says the Tao Te Ching (trans. Stephen Mitchell), and “true straightness seems crooked.” Still, some things are truly crooked.

DoD Legislative Proposals to be Published

After failing to publicly disclose its proposed legislative agenda, the Department of Defense will soon be required to do so.

Each year DoD generates proposals for legislative actions that it would like to see incorporated in the coming year’s national defense authorization act. These may include tweaks to existing statutes, requests for relief from reporting requirements, or something more ambitious.

It used to be the case — until two years ago — that those legislative proposals were routinely posted on the website of the DoD Office of Legislative Counsel where they could be publicly examined and evaluated. Then, without explanation, DoD stopped posting them.

Last spring, one of DoD’s more far-reaching but publicly undisclosed proposals sought to rescind a requirement to produce an unclassified version of the Future Years Defense Program budget document. (Secrecy News, 03/30/20),

That proposal was not adopted in the House-Senate conference version of the FY2021 defense authorization act (HR 6395).

But Congress did adopt a provision (sec. 1059) crafted by Reps. Katie Porter and Jackie Speier that will now require DoD to publish its legislative proposals online within 21 days of their transmission to Congress.

* * *

Last month, the Departments of Energy and Defense denied a request from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the current size of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and the number of warheads that have been dismantled. Such information had previously been declassified and published by the executive branch each year through 2017. But for now it remains classified. See “Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size” by Hans Kristensen, FAS Strategic Security, December 3.

Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

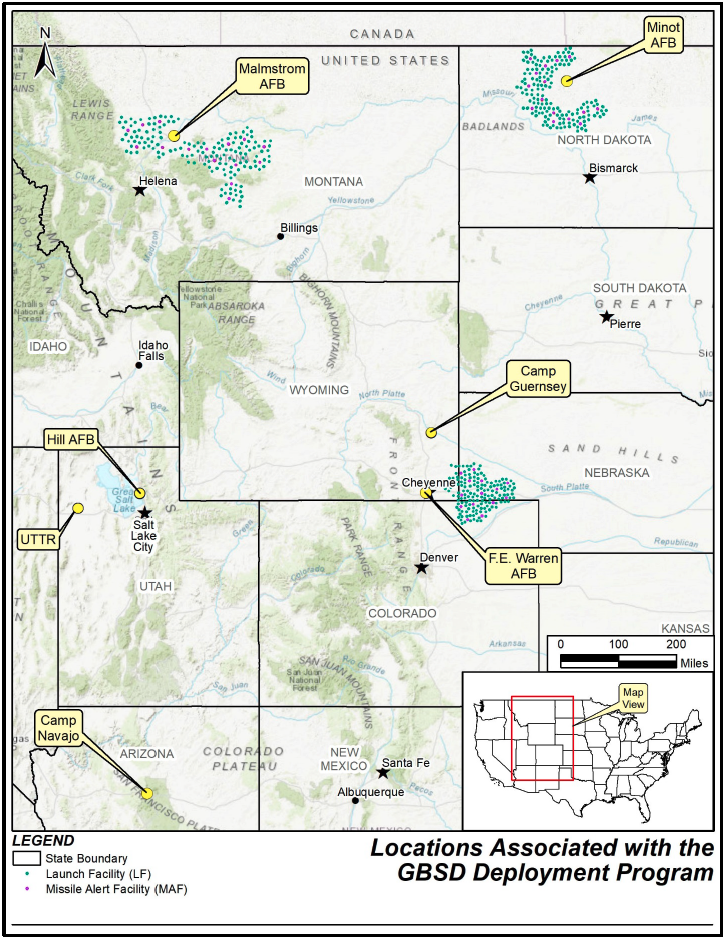

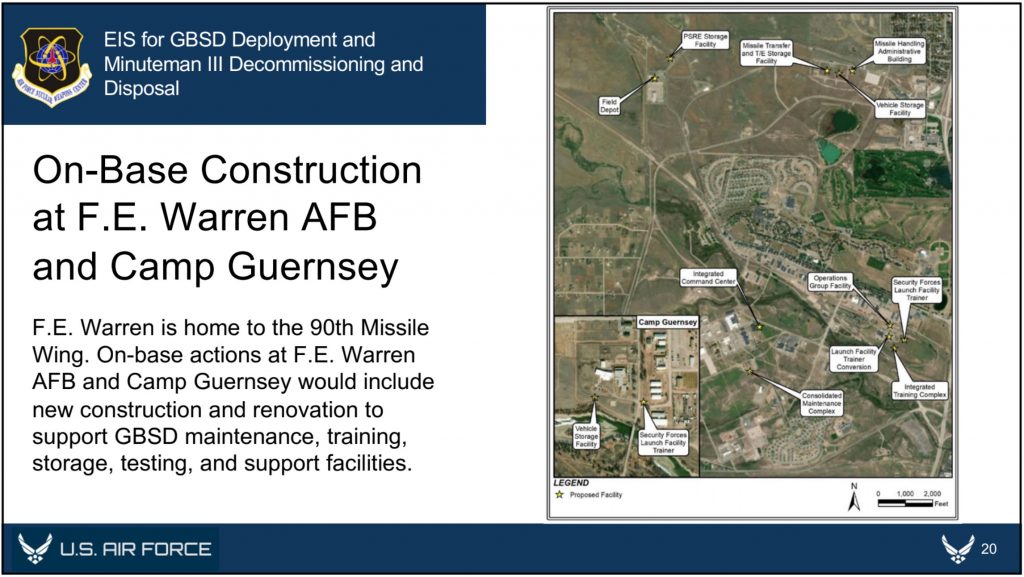

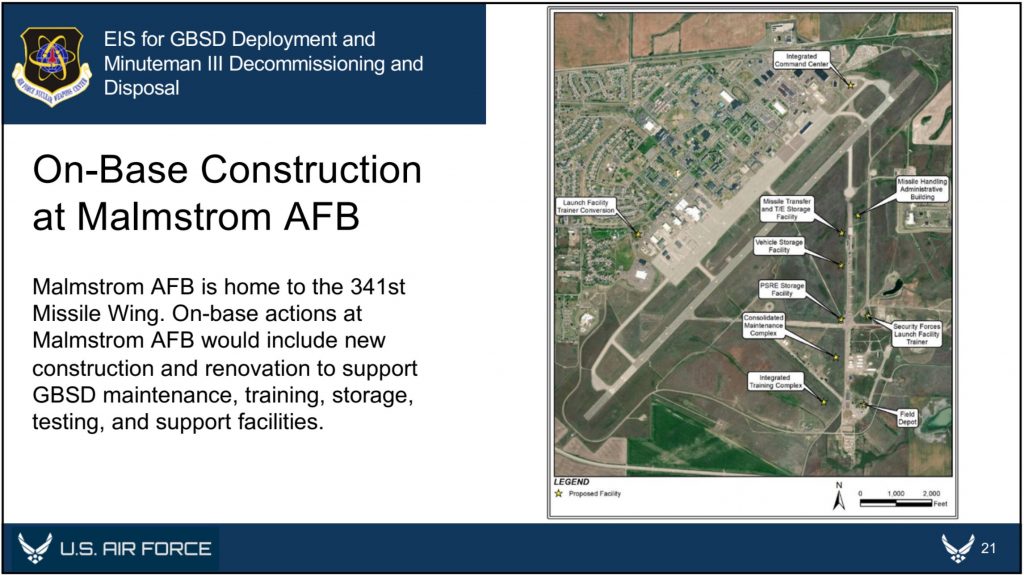

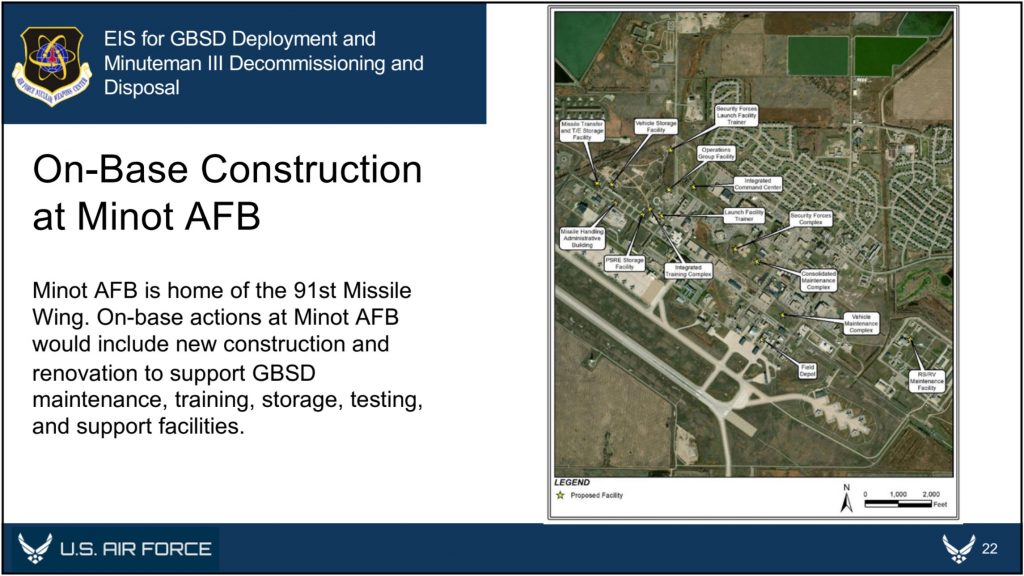

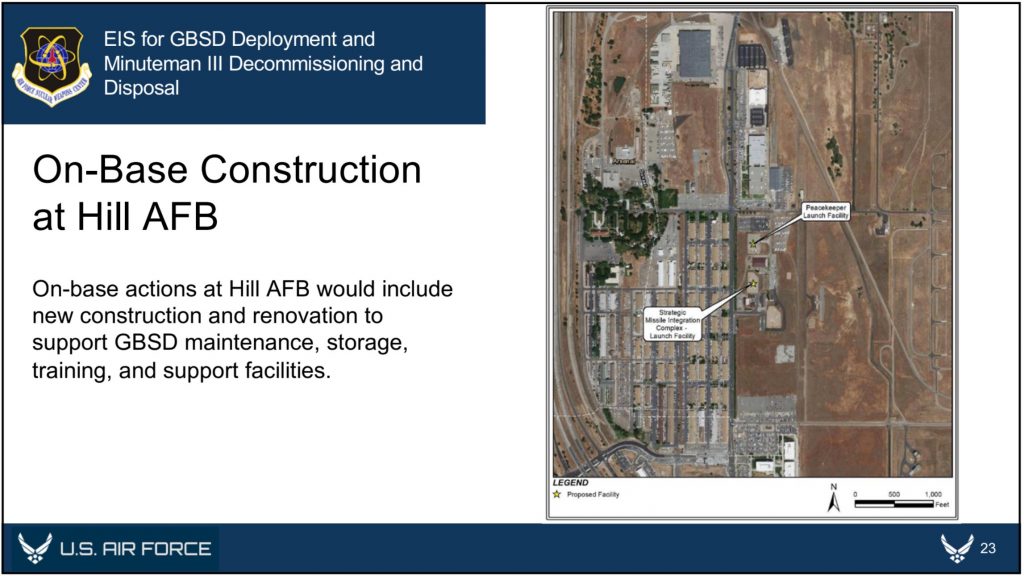

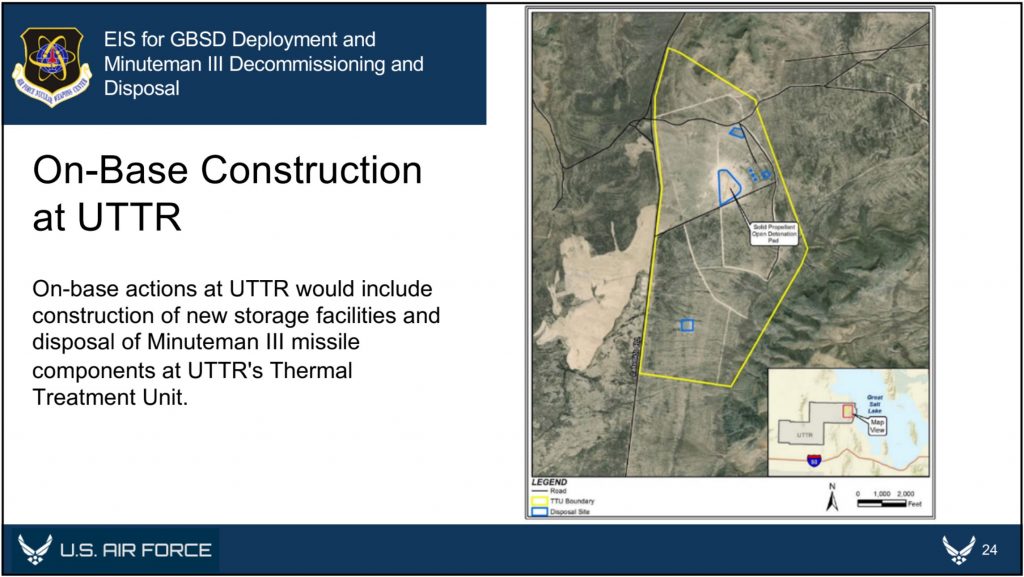

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

Senator’s Challenge to War Powers Secrecy Blocked

Last January the Trump Administration formally notified Congress under the War Powers Act of a US drone strike that killed Iranian Maj. Gen. Qasem Soleimani.

But unlike all known prior War Powers Act notifications, the report on the Soleimani killing was classified in its entirety. (Previous reports sometimes included a classified annex together with the unclassified notification.)

Senator Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) said that was unacceptable. “There’s a veil being pulled over the foreign policy of this country,” he told the Washington Post. See “Six months later, Democrats keep working to unearth a big national security secret” by Greg Sargent, The Washington Post Plum Line, July 21, 2020.

Senator Murphy asked the White House to reconsider the classification. “It is critical that decisions regarding the use of force consistent with the War Powers Act be provided in unclassified form to the American people,” he wrote. He received no response.

So he turned to the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel (ISCAP), a group of executive branch agency representatives that is authorized by executive order to decide appeals of challenges to classification.

The initiative failed. Last month the ISCAP said that it would not consider such an appeal from Senator Murphy or from any other member of Congress.

The ISCAP refusal leaves the War Powers Act report on Soleimani fully classified and it keeps the public in the dark about the asserted legal and factual basis for killing him. But it highlights an important gap in classification policy that could be corrected in a new Administration and a new Congress.

* * *

When information is classified improperly or unnecessarily, the opportunities for correcting such actions are quite limited.

A provision for government employees to formally challenge the classification of certain information was introduced in President Clinton’s 1995 executive order 12958 (section 1.9) and has remained in effect until the present (executive order 13526, section 1.8). The provision states:

“Authorized holders of information who, in good faith, believe that its classification status is improper are encouraged and expected to challenge the classification status of the information. . . .”

Importantly, this provision was not intended as a courtesy or a privilege. In fact, it was not intended for the sake of the challengers at all. Rather, the purpose of such classification challenges was to promote the integrity of the classification system and to help make the system self-correcting, as far as possible. That’s why potential challengers are “encouraged and expected” to present challenges even if they don’t personally care about the issue at all.

There were 954 such challenges in fiscal year 2016, according to the Information Security Oversight Office, and 167 of those resulted in the classification being overturned in whole or in part. In FY 2017, there were 721 challenges, 58 of which led to changes in classification.

No member of Congress had ever invoked this provision before. But Senator Murphy had some reason to believe that such a classification challenge could be effective in the case of the Soleimani war powers report.

The sticking point was the definition of “authorized holders of [classified] information,” who are the only ones that can present a classification challenge under the executive order.

One would suppose that a member of Congress who is in possession of a classified report that was officially provided to him or her by the executive branch would certainly qualify as an “authorized holder.” In fact, the executive branch has a binding legal obligation to provide certain classified defense and intelligence information to Congress.

But it turns out that the executive order (in section 6.1c) narrowly defines an “authorized holder of classified information” as one who has been vetted by an agency and found eligible for access. (Oddly, this limiting definition was only added in 2009.) Since Members of Congress are cleared for classified information by virtue of their office and do not undergo agency vetting, they are not “authorized persons” for purposes of the executive order.

This does not make any sense from a policy point of view. Just as executive branch employees and contractors are “encouraged and expected” to point out potential errors in classification, so should Members of Congress be, and for the same reasons.

But the classification challenge procedure is constrained by the language of the executive order, said Mark Bradley, director of the Information Security Oversight Office and executive secretary of the ISCAP.

“We have to do what the Order says, not what we want,” said Mr. Bradley, who early in his career served as an aide to Senator Daniel P. Moynihan.

* * *

Mr. Bradley suggested that Senator Murphy could direct his challenge to the Public Interest Declassification Board, which unlike the ISCAP is specifically authorized to review congressional challenges to the classification of certain records.

But the PIDB is a much weaker body than the ISCAP. While the ISCAP can “decide” on classification challenges (subject to appeal), the PIDB can only review and “recommend.” And while the ISCAP has actually overturned existing classifications on numerous occasions, no PIDB recommendation has ever had the same effect.

The PIDB did previously handle one congressional request for declassification review, said John Powers of the ISOO and PIDB staff, in or around 2014. For the most part, the subject document in that case turned out to be properly classified, substantively and procedurally, in the PIDB’s view. But the Board forwarded a limited redaction proposal that would have allowed partial release to the Obama White House for consideration. The White House did not act on it.

Senator Murphy turned to the PIDB to request declassification review of classified intelligence concerning foreign interference in the upcoming US elections, the Washington Post reported yesterday.

* * *

The statement by ISOO director Mark Bradley cited above — “We have to do what the Order says, not what we want” — is worth further consideration.

What he was saying is that those who are responsible for enforcing checks and balances have to follow a code of conduct and have to adhere to a set of principles, whether or not they personally agree with the outcome in a particular case.

The problem is that those who abuse the system to classify (or sometimes to selectively declassify) information improperly recognize no such constraint. This discrepancy is vexatious.

It means that the checks and balances of the current system are most effective when they are least necessary. When everyone is acting in good faith and with an honest commitment to shared (constitutional) values, most disagreements can be resolved over time. Some compromise is usually possible.

But when good faith and principled self-restraint are lacking, and one side aims to maximize its power at any cost, the current structure of checks and balances has proved to be largely helpless.

Even if the ISCAP had agreed to consider Senator Murphy’s classification challenge, and if it had actually agreed with him that all or part of the War Powers Act notification concerning the Soleimani killing was not properly classified, that might not have been the end of the story.

“Panel decisions are committed to the discretion of the Panel,” according to the executive order (sect. 5.3e), “unless changed by the President.” But that means that a hypothetical ISCAP decision to declassify the notification could be overruled by the same White House that classified the whole thing in the first place.

So while good policies are necessary, they are not enough. For our constitutional system of government to work, we also need officials who are, if not the “angels” that James Madison spoke of, at least dedicated public servants who share a common purpose.

Senator Murphy’s office said that he would soon introduce legislation to authorize and require the ISCAP to consider classification challenges from Congress.

* * *

The current infrastructure for declassifying classified records that are no longer sensitive is already being overwhelmed by a deluge of historical records that are accumulating faster than they can be processed. This situation was discussed in a September 9 hearing before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and is the subject of new legislation (S. 3733) introduced by Senators Wyden and Moran.

That is an issue of efficiency and productivity that probably has a technological solution, as the Public Interest Declassification Board has argued.

A harder problem is over-classification, in which information is classified improperly or unnecessarily, or at a higher level than is warranted. Such classification errors can be corrected, at least hypothetically, through classification challenges, Freedom of Information Act requests, and other means.

A still harder problem concerns information that is properly classified — in the sense that it meets the criteria of the executive order — but nevertheless belongs in the public domain because of its fundamental policy importance. Examples include classified reports of torture, mass surveillance, or foreign election interference.

To the extent that such information is “properly classified” in a formal sense, it is currently beyond the reach of the Freedom of Information Act, mandatory declassification review, or classification challenges. When it does become public, that is often due to unauthorized disclosures. While agency heads may declassify classified information in the public interest as a matter of discretion (under section 3.1d of the executive order), they rarely do so and there is no mechanism for asking or inducing them to.

So along with adequate basic functionality and improved procedures for challenging improper classification, any future classification system also needs to tackle the problem of “properly classified” information that should not be classified.

Pentagon Seeks Authority to Recall More Retirees to Duty

The Department of Defense is asking Congress to expand its authority to recall retired members of the military to active duty in the event of a war or national emergency.

The DoD proposal predates the turmoil that followed the killing of George Floyd by a police officer in Minneapolis last week and the activation of National Guard units in numerous states.

Current law (10 USC 688a) permits the military to recall no more than 1,000 retirees in order “to alleviate a high-demand, low-density military capability” or when necessary “to meet wartime or peacetime requirements.” DoD wants to remove that 1,000 person limit.

“This proposal . . . would allow the Secretary of a military department to recall more than 1,000 retirees to active duty during a war or national emergency,” the Pentagon said in its May 4 request, which is one of numerous legislative proposals for the FY 2021 defense authorization act.

“Waiving the 1,000 member limitation on this temporary recall authority and the authority’s expiration date in time of war or of national emergency will increase the Department of Defense’s flexibility and agility in generating forces with the expertise required to respond rapidly and efficiently during such a period.”

“Given the unpredictability of war and national emergencies, such as the COVID 19 pandemic, waiver of the 1,000-member limit will better posture the Department to respond to unpredictable and rapidly evolving situations,” DoD said.

There is no reason to be concerned that such authority would ever be abused, the Pentagon told Congress, because “The Office of the Secretary of Defense will ensure the amount of recalled retirees does not exceed the number warranted by mission requirements.”

Last March, the US Army contacted more than 800,000 retired soldiers to inquire if they would be willing to assist with military’s pandemic response, according to a report in Military.com.

The Congressional Research Service summarized the constitutional and statutory authorities and limitations governing the military role in disaster relief and law enforcement in The Use of Federal Troops for Disaster Assistance: Legal Issues, November 5, 2012.

Air Force Calls for Expansion of Nevada Test Range

The US Air Force wants to renew and expand the withdrawal of public land for the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR), where it conducts flight testing, classified research and development projects, and weapons tests. A Defense Department proposal to Congress would increase the amount of land currently withdrawn from public use by more than 10 percent.

The NTTR is already “the largest contiguous air and ground space available for peacetime military operations in the free world,” according to a 2017 Air Force fact sheet.

But it’s not big enough to meet future requirements, the Pentagon told Congress in an April 17 legislative proposal.

“The land withdrawal that makes up the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR) expires in 2021. The NTTR is the Air Force’s most vital test and training asset and must be continued,” the DoD proposal said. But even more is needed, according to DoD: “Maintaining the status quo by simply extending the current withdrawal will not be sufficient to meet 5th generation requirements.”

“This proposal would expand the current withdrawal, enacted in the FY2000 NDAA and set to expire in 2021, and make that withdrawal for a period of 25 years.”

Approximately 300,000 acres of additional land would be withdrawn under the proposal, for a total of around 3.2 million acres that would be reserved “for use by the Secretary of the Air Force for certain military purposes.”

As of now, “The range occupies 2.9 million acres of land, 5,000 square miles of airspace which is restricted from civilian air traffic over-flight and another 7,000 square miles of Military Operating Area, or MOA, which is shared with civilian aircraft,” the 2017 USAF fact sheet said. “The 12,000-square-nautical mile range provides a realistic arena for operational testing and training aircrews to improve combat readiness. A wide variety of live munitions can be employed on targets on the range.”

Many Reports to Congress May Go Online

Many of the hundreds or thousands of reports that are submitted to Congress by executive branch agencies each year may be published online pursuant to a provision in the new Consolidated Appropriations Act (HR 1158, section 8092).

That provision states that any agency that is funded by the Act shall post on its website any report to Congress “upon the determination by the head of the agency that it shall serve the national interest.”

The impact of the latter condition is unclear, particularly since no criteria for satisfying the national interest are defined. In any case, reports containing classified or proprietary information would be exempt from publication online, and publication of all reports would be deferred for at least 45 days after their receipt by Congress, diminishing their relevance, timeliness and news value.

Reports to Congress often contain new information and perspectives but they are an under-utilized resource particularly because they are not readily available.

Some otherwise unpublished 2019 reports address, for example, DoD use of open burn pits, political boycotts of Israel, and the financial cost of war post-9/11.

The newly enacted FY2020 national defense authorization act alone includes hundreds of new, renewed, or modified reporting requirements, according to an unofficial tabulation.

Mixed Messages On Trump’s Missile Defense Review

President Trump personally released the long-overdue Missile Defense Review (MDR) today, and despite the document’s assertion that “Missile Defenses are Stabilizing,” the MDR promotes a posture that is anything but.

Firstly, during his presentation, Acting Defense Secretary Shanahan falsely asserted that the MDR is consistent with the priorities of the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). The NSS’ missile defense section notes that “Enhanced missile defense is not intended to undermine strategic stability or disrupt longstanding strategic relationships with Russia or China.” (p.8) During Shanahan’s and President Trump’s speeches, however, they made it clear that the United States will seek to detect and destroy “any type of target,” “anywhere, anytime, anyplace,” either “before or after launch.” Coupled with numerous references to Russia’s and China’s evolving missile arsenals and advancements in hypersonic technology, this kind of rhetoric is wholly inconsistent with the MDR’s description of missile defense being directed solely against “rogue states.” It is also inconsistent with the more measured language of the National Security Strategy.

Secondly, the MDR clearly states that the United States “will not accept any limitation or constraint on the development or deployment of missile defense capabilities needed to protect the homeland against rogue missile threats.” This is precisely what concerns Russia and China, who fear a future in which unconstrained and technologically advanced US missile defenses will eventually be capable of disrupting their strategic retaliatory capability and could be used to support an offensive war-fighting posture.

Thirdly, in a move that will only exacerbate these fears, the MDR commits the Missile Defense Agency to test the SM-3 Block IIA against an ICBM-class target in 2020. The 2018 NDAA had previously mandated that such a test only take place “if technologically feasible;” it now seems that there is sufficient confidence for the test to take place. However, it is notable that the decision to conduct such a test seems to hinge upon technological capacity and not the changes to the security environment, despite the constraints that Iran (which the SM-3 is supposedly designed to counter) has accepted upon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

Fourthly, the MDR indicates that the United States will look into developing and fielding a variety of new capabilities for detecting and intercepting missiles either immediately before or after launch, including:

- Developing a defensive layer of space-based sensors (and potentially interceptors) to assist with launch detection and boost-phase intercept.

- Developing a new or modified interceptor for the F-35 that is capable of shooting down missiles in their boost-phase.

- Mounting a laser on a drone in order to destroy missiles in their boost-phase. DoD has apparently already begun developing a “Low-Power Laser Demonstrator” to assist with this mission.

There exists much hype around the concept of boost-phase intercept—shooting down an adversary missile immediately after launch—because of the missile’s relatively slower velocity and lack of deployable countermeasures at that early stage of the flight. However, an attempt at boost-phase intercept would essentially require advance notice of a missile launch in order to position US interceptors within striking distance. The layer of space-based sensors is presumably intended to alleviate this concern; however, as Laura Grego notes, these sensors would be “easily overwhelmed, easily attacked, and enormously expensive.”

Additionally, boost-phase intercept would require US interceptors to be placed in very close proximity to the target––almost certainly revealing itself to an adversary’s radar network. The interceptor itself would also have to be fast enough to chase down an accelerating missile, which is technologically improbable, even years down the line. A 2012 National Academy of Sciences report puts it very plainly: “Boost-phase missile defense—whether kinetic or directed energy, and whether based on land, sea, air, or in space—is not practical or feasible.”

Overall, the Trump Administration’s Missile Defense Review offers up a gamut of expensive, ineffective, and destabilizing solutions to problems that missile defense simply cannot solve. The scope of US missile defense should be limited to dealing with errant threats—such as an accidental or limited missile launch—and should not be intended to support a broader war-fighting posture. To that end, the MDR’s argument that “the United States will not accept any limitation or constraint” on its missile defense capabilities will only serve to raise tensions, further stimulate adversarial efforts to outmaneuver or outpace missile defenses, and undermine strategic stability.

During the upcoming spring hearings, Congress will have an important role to play in determining which capabilities are actually necessary in order to enforce a limited missile defense posture, and which ones are superfluous. And for those superfluous capabilities, there should be very strong pushback.

DoD Says US, Turkey on a Collision Course

Turkey’s pending procurement of a Russian surface to air missile system would jeopardize its status in NATO, and disrupt other aspects of US military relations with that country, the Department of Defense told Congress.

“The U.S. Government has made clear to the Turkish Government that purchasing the S-400 [surface to air missile system] would have unavoidable negative consequences for U.S.-Turkey bilateral relations, as well as Turkey’s role in NATO,” DoD said in an unclassified summary of a classified report to Congress.

See DoD report to Congress on Status of the U.S. Relationship with the Republic of Turkey (unclassified summary), November 2018.

The report was obtained and reported by Bloomberg News. See “Turkey’s F-35 Role at Risk If It Buys From Russia, Pentagon Warns” by Tony Capaccio, November 28, 2018.

Next HASC Chair Sees Need for Greater DoD Transparency

Rep. Adam Smith (D-WA), the likely chair of the House Armed Services Committee in the next Congress, told congressional colleagues that enhancing national security transparency is among his top oversight priorities.

“Together, we have made strides on national security issues but much more must be done to conduct vigorous oversight of the Trump Administration and the Department of Defense,” he wrote in a November 8 letter to House Democrats, declaring his candidacy for HASC chairman.

“Specifically, we must look to eliminate inefficiency and waste at the DOD; boost oversight of sensitive military operations and ensure that the military works to avoid civilian casualties; protect our environmental laws nationwide; advance green technology in defense; take substantial steps to reduce America’s overreliance on nuclear weapons; and promote greater transparency in national security matters,” he wrote.

In an opinion column last month, Rep. Smith elaborated on the topic. He said the Trump Administration and the Pentagon had abused their secrecy authority with counterproductive results.

“The Defense Department under this administration [. . .] declared war on transparency in their earliest days on the job. On issue after issue, they have made conspicuous decisions to roll back transparency and public accountability precisely when we need it most,” he wrote, citing numerous examples of unwarranted secrecy.

A course correction is needed, he said.

“Candid discussion with Congress about military readiness, the defense budget, or deployments around the world; the release of general information about the effectiveness of weapons systems that taxpayers are funding; and many other basic transparency practices have not harmed national security for all the years that they have been the norm,” he wrote. “The efforts to further restrict this information are unjustified, and if anything, the recent policies we have seen call for an increase in transparency.”

See “The Pentagon’s Getting More Secretive — and It’s Hurting National Security” by Rep. Adam Smith, Defense One, October 28, 2018.

* * *

The mystery surrounding a classified US military operation called Yukon Journey was partially dispelled by a news story in Yahoo News.

“Even as the humanitarian crisis precipitated by Saudi Arabia’s more-than-three-year war in Yemen has deepened, the Pentagon earlier this year launched a new classified operation to support the kingdom’s military operations there, according to a Defense Department document that appears to have been posted online inadvertently.”

See “Pentagon launched new classified operation to support Saudi coalition in Yemen” by Sharon Weinberger, Sean Naylor and Jenna McLaughlin, Yahoo News, November 10.

* * *

The need for greater transparency in military matters will be among the topics discussed (by me and others) at a briefing sponsored by Sen. Jack Reed and the Costs of War Project at Brown University on Wednesday, November 14 at 10 am in 236 Russell Senate Office Building. A new report on the the multi-trillion dollar costs of post-9/11 US counterterrorism operations will be released.