Impacts of Extreme Heat on Children’s Health and Future Success

Extreme heat poses serious and growing risks to children’s health, safety, and education. Yet, schools and childcare facilities are unprepared to handle rising temperatures. To protect the health and well-being of American children, Congress should (1) set policies that guide childcare facilities and schools in preparing for and responding to extreme heat, (2) collect the data required to inform extreme heat readiness and adaptation, and (3) strategically invest in necessary infrastructure upgrades to build heat resilience.

Children are Uniquely Vulnerable to Extreme Heat Exposure and Acute and Chronic Health Impacts

At least five factors drive children’s vulnerability to negative health outcomes from extreme heat, like heat-related illnesses and chronic complications. First, children’s bodies take a longer time to increase sweat production and acclimatize to higher temperatures. Second, young children are more prone to dehydration than adults because a larger percentage of their body weight is water. Third, infants and young children have challenges regulating their body temperatures and often do not recognize when they should act to cool down. Fourth, compared with adults, children spend more time active outdoors, which results in increased exposure to high ambient heat. Fifth, children usually depend on others to provide them with water and protect them from unsafe outdoor environments, but children’s caretakers often underestimate the seriousness of the symptoms of heat stress. Research shows that extreme heat days are linked to increased emergency room (ER) visits for children, especially the 16% of children living at or below the federal poverty line. Extreme heat also exacerbates children’s chronic diseases, like asthma and eczema, increasing health care costs and decreasing children’s overall quality of life.

The Consequences of Chronic Extreme Heat Exposure on Children’s Learning and Well-Being

Studies show that excess temperatures reduce cognitive functioning. Hot weather also impacts children’s behavior, making them more prone to restlessness, irritability, aggression, and mental distress. Finally, nighttime extreme heat exposure can disrupt sleep patterns, making it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep. These factors can all reduce children’s ability to focus, learn and succeed in school. For each 1°F rise in average annual temperature in school districts without air conditioning or proper heat protections, there is a 1% drop in learning. The Environmental Protection Agency found that these learning losses could translate into nearly $7 billion dollars in annual future income losses if warming trends continue.

Extreme Heat’s Threat to Schools and Childcare Facilities

Rising temperatures force school districts and childcare facilities into a dilemma: choosing between staying open in unsafe heat or closing and disrupting learning and care.

Staying open can expose students and young children to extreme indoor and outdoor temperatures. The Government Accountability Office found that 41% of U.S. schools need to upgrade their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems: upgrades that will cost billions of dollars that schools in low-income areas do not have. Similar infrastructure challenges extend to childcare facilities. Extreme heat also makes outdoor recess more dangerous, as unshaded playgrounds and asphalt surfaces can heat up far above ambient temperatures and pose burn risks.

Yet when schools close for heat, children still suffer. Even five days of closures for inclement weather in a school year can cause measurable learning loss. Additionally, students may lose access to school meals; while food service continuation plans exist, overheated facilities can complicate implementation. Many children, especially in low-income families, also don’t have access to reliable cooling at home, meaning that when schools close for heat, these children receive little respite. Finally, parents are directly impacted as well: school closures also mean parents lose access to childcare, forcing many to miss work or pay for alternative arrangements, straining vulnerable households.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard American Children from the Impacts of Extreme Heat

To support the capacity of child-serving facilities to adapt to extreme heat, Congress should direct the Department of Education to develop extreme heat guidance, technical assistance programs, and temperature standards, following existing state-level policies as a model for action. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop analogous policies for early childhood facilities and daycare centers receiving federal funding. Finally, Congress should direct the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

To support improved federal data collection efforts on extreme heat’s impacts, Congress should direct the Department of Education and Administration for Children and Families to collect data on how schools and childcare facilities are experiencing and responding to extreme heat. There should be a particular focus on the infrastructure upgrades that these facilities need to make to be more prepared for extreme temperatures — especially in low-income and rural communities.Lastly, to foster much-needed infrastructure improvements in schools and childcare facilities, Congress should consider amending Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act or directing the Department of Education to clarify that funds for Title I schools may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning losses. These upgrades can include the replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavement, solar and other shade canopies, and green roofs, trees, and other green infrastructure, which can keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to identify funding resources that can be used to upgrade federally-supported childcare facilities.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Federal Healthcare Spending

Public health insurance programs, especially Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), are more likely to cover populations at increased risk from extreme heat, including low-income individuals, people with chronic illnesses, older adults, disabled adults, and children. When temperatures rise to extremes, these populations are more likely to need care for their heat-related or heat-exacerbated illnesses. Congress must prioritize addressing the heat-related financial impacts onthese programs. To boost the resilience of these programs to extreme heat, Congress should incentivize prevention by enabling states to facilitate health-related social needs (HRSN) pilots that can reduce heat-related illnesses, continue to support screenings for the social drivers of health, and implement preparedness and resilience requirements into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs) of relevant programs.

Extreme Heat Increases Fiscal Impacts on Public Insurance Programs

Healthcare costs are a function of utilization, which has been rapidly rising since 2010. Extreme heat is driving up utilization as more Americans seek medical care for heat-related illnesses. Extreme heat events are estimated to be annually responsible for nearly 235,000 emergency department visits and more than 56,000 hospital admissions, adding approximately $1 billion to national healthcare costs.

Heat-driven increases in healthcare utilization are especially notable for public insurance programs. One recent study found that there is a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits and a 7% increase in hospitalizations during heat wave days for low-income populations eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. Further demonstrating the relationship between increased spending and extreme heat, the Congressional Budget Office found that for every 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, extreme temperatures cause an additional 156 emergency department visits and $388,000 in spending per day on average. These higher utilization rates also drive increases in Medicaid transfer payments from the federal government to help states cover rising costs. For every 10 additional days of extreme heat above 90°F, annual Medicaid transfer payments increase by nearly 1%, equivalent to an $11.78 increase per capita.

Additionally, Medicaid funds services for over 60% of nursing home residents. Yet Medicaid reimbursement rates often fail to cover the actual cost of care, leaving many facilities operating at a financial loss. This can make it difficult for both short-term and long-term care facilities to invest in and maintain the cooling infrastructure necessary to comply with existing requirements to maintain safe indoor temperatures. Further, many short-term and long-term care facilities do not have the emergency power back-ups that can keep the air conditioning on during extreme weather events and power outages, nor do they have emergency plans for occupant evacuation in case of dangerous indoor temperatures. This can and does subject residents to deadly indoor temperatures that can worsen their overall health outcomes.

The Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R. 1) will have consequential impacts on federally-supported health insurance programs. The Congressional Budget Office projects that an estimated 10 million people could lose their healthcare coverage by 2034. Researchers have estimated that a loss of coverage could result in 50,000 preventable deaths. Further, health care facilities and hospitals will likely see funding losses as a result of Medicaid funding reductions. This will be especially burdensome to low-resourced hospitals, such as those serving rural areas, and result in reductions in available offerings for patients and even closure of facilities. States will need support navigating this new funding landscape while also identifying cost-effective measures and strategies to address the health-related impacts of extreme heat.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard America’s Health from Extreme Heat

To address these impacts in this additionally challenged context, there are common-sense strategies to help people avoid extreme heat exposure. For example, access to safely cool indoor environments is one of the best preventative strategies for heat-related illness. In particular, Congress should create a demonstration pilot that provides eligible Medicare beneficiaries with cooling assistance and direct CMS to encourage Section 1115 demonstration waivers for HRSN related to extreme heat. Section 1115 waivers have enabled states to finance pilots for life-saving cooling devices and air filter distributions. These HRSN financing pilots have helped several states to work around the challenges of U.S. underinvestment in health and social services by providing a flexible vehicle to test methods of delivering and paying for healthcare services in Medicaid and CHIP. As Congress members explore these policies, they should consider the impact of H.R. 1’s new requirements for 1115 waiver’s proof of cost-neutrality.

To further support these efforts for heat interventions, Congress should direct CMS to continue Social Drivers of Health (SDOH) screenings as a part of Quality Reporting Programs and integrate questions about extreme heat exposure risks into the screening process. These screenings are critical for identifying the most vulnerable patients and directing them to the preventative services they need. This information will also be critical for identifying facilities that are treating high proportions of heat-vulnerable patients, which could then be sites for testing interventions like energy and housing assistance.

Congress should also direct the CMS to integrate heat preparedness and resilience requirements and metrics into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs), such as through the Emergency Preparedness Rule. This could include assessing the cooling capacity of a health care facility under extreme heat conditions, back-up power that is sufficient to maintain safe indoor temperatures, and policies for resident evacuation in the event of high indoor temperatures. For safety net facilities, such as rural hospitals and federally qualified health centers, Congress should consider allocating resources for technical assistance to assess these risks and the infrastructure upgrades.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Agriculture

Agriculture, food, and related industries produce nearly 90% of the food consumed in the United States and contribute approximately $1.54 trillion to the national GDP. Given the agricultural sector’s importance to the national economy, food security, and public health, Congress must pay attention to the impacts of extreme heat. To boost the resilience of this sector, Congress should design strategic insurance solutions, enhance research and data, and protect farmworkers through on-farm adaptation measures.

Extreme Heat Reduces Farm Productivity and Profitability

Extreme heat threatens agricultural productivity by increasing crop damage, causing livestock illness and mortality, and worsening water scarcity. Hotter conditions can damage crops through crop sunburn and heat stress, reducing annual yields for farms by as much as 40%. Animals raised for meat, milk, and eggs also experience increased risks of heat stress and heat-related mortality. For dairy production in particular, an estimated 1% of total annual yield is lost to heat stress alone. Further straining agricultural productivity, extreme heat accelerates water scarcity by increasing water evaporation rates. These higher evaporation rates force farmers to use even more water, drawing often from already stressed water sources. The compounding pressures posed by extreme heat can translate into significant economic losses: a study of Kansas commodity farms found that for every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in temperature, net farm incomes drop by 66%. Together, this means reduced revenue for farms and less food available for people.

Insurance solutions can help mitigate these financial impacts from extreme heat if employed responsibly. Multiple permanently authorized federal programs provide insurance or direct payments to help producers recover losses from extreme heat, including the Federal Crop Insurance Program, the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, the Livestock Indemnity Program, and the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program. These programs need to ensure that producers are adequately covered against heat-related impacts and incentivize practices that reduce the risk of extreme heat related damages. This in turn will reduce the fiscal exposure of federal farm risk management programs. Congress should call on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to research the feasibility of incentivizing heat resilience through federal crop insurance rates. Congress should also consider insurance premium subsidies for producers who adopt practices that enhance heat resilience for crops and livestock.

Given the increasing stress of extreme heat on the water systems necessary to sustain agricultural production, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should build on its Weather, Water, and Climate Strategy and collaborate with USDA on a national water security strategy that accounts for current and future hotter temperatures. To enhance system-wide drought resilience, Congress can also appropriate funds to leverage existing USDA programs to support on-farm adoption of shade systems, effective water management, cover crops, and soil regeneration practices.

Finally, there are still notable knowledge gaps around extreme heat and its impacts on agriculture. These gaps include the long-term effects of higher temperatures on yields, farm input costs, and federal program spending. To address these information gaps and guide future research, Congress can direct the USDA Secretary to submit a report to Congress on the impacts of extreme heat on agriculture, farm input costs and losses, consumer prices, and the federal government’s spending (e.g., federal insurance and direct payment programs for losses of agricultural products and the provision of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits).

Extreme Heat Lowers Agricultural Workers’ Productivity and Exposes Them to Health Risks

Higher temperatures and resulting heat stress are endangering farmer and farmworker safety and reducing their overall productivity, impacting bottom lines. Farmworkers are essential to the American food system, yet they are among the most vulnerable to extreme heat, facing a 35 times greater risk of dying from heat-related illnesses than workers in other sectors. This risk is intensifying as the sector increasingly relies on H‑2A farmworkers, who are hired to fill persistent domestic farm labor shortages. In many regions, over 25% of certified H‑2A farmworkers are required to work when local average temperatures exceed 90°F, and counties with the highest concentrations of H‑2A workers often coincide with the hottest parts of the country. After the work day, many of these workers return to substandard employer-provided housing that lacks essential cooling or ventilation, preventing effective recovery from daily heat exposure and exacerbating heat-related health risks. On top of the health risks, these conditions make people less effective on the job, which translates to economy-wide impacts: heat-related labor productivity losses across the U.S. economy currently exceeds $100 billion annually.

To address these risks, Congress should pass legislation requiring the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to finalize a federal heat standard that provides sufficient coverage for farming operations. In tandem with Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) finalizing the standard, USDA should be funded to provide technical assistance to agricultural employers for tailoring heat illness prevention plans and implementing cost-effective interventions that improve working conditions while maintaining productivity. This should include support for agricultural employers to integrate heat awareness into workforce training, resources for safety equipment and education, and support for the addition of shade structures. Doing so would ensure that agricultural workers across both large and small-scale farming operations have access to essential protections, like shade, clean water, and breaks, as well as sufficient capacity to comply. Current funding streams that could have an extreme heat infrastructure “plus-up” include the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Farm Service Agency’s microloans program.Lastly, Congress should also direct OSHA to continue implementing its National Emphasis Program on Heat, which enforces employers’ obligation to protect workers against heat illness or injury. OSHA should additionally review employers’ practices to ensure that H2A and other agricultural workers are protected from job or wage loss when extreme heat renders working conditions unsafe.

Clean Water: Protecting New York State Private Wells from PFAS

This memo responds to a policy need at the state level that originates due to a lack of relevant federal data. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a learning agenda question that asks,“To what extent does EPA have ready access to data to measure drinking water compliance reliably and accurately?” This memo fills that need because EPA doesn’t measure private wells.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are widely distributed in the environment, in many cases including the contamination of private water wells. Given their links to numerous serious health consequences, initiatives to mitigate PFAS exposure among New York State (NYS) residents reliant on private wells were included among the priorities outlined in the annual State of the State address and have been proposed in state legislation. We therefore performed a scenario analysis exploring the impacts and costs of a statewide program testing private wells for PFAS and reimbursing the installation of point of entry treatment (POET) filtration systems where exceedances occur.

Challenge and Opportunity

Why care about PFAS?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of chemicals containing millions of individual compounds, are of grave concern due to their association with numerous serious health consequences. A 2022 consensus study report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine categorized various PFAS-related health outcomes based on critical appraisal of existing evidence from prior studies; this committee of experts concluded that there is high confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) decreased antibody response (a key aspect of immune function, including response to vaccines) (2) dyslipidemia (abnormal fat levels in one’s blood), (3) decreased fetal and infant growth, and (4) kidney cancer, and moderate confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) breast cancer, (2) liver enzyme alterations, (3) pregnancy-induced high blood pressure, (4) thyroid disease, and (5) ulcerative colitis (an autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease).

Extensive industrial use has rendered these contaminants virtually ubiquitous in both the environment and humans, with greater than 95% of the U.S. general population having detectable PFAS in their blood. PFAS take years to be eliminated from the human body once exposure has occurred, earning their nickname as “forever chemicals.”

Why focus on private drinking water?

Drinking water is a common source of exposure.

Drinking water is a primary pathway of human exposure. Combining both public and private systems, it is estimated that approximately 45% of U.S. drinking water sources contain at least one PFAS. Rates specific to private water supplies have varied depending on location and thresholds used. Sampling in Wisconsin revealed that 71% of private wells contained at least one PFAS and 4% contained levels of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), two common PFAS compounds, exceeding Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) of 4 ng/L. Sampling in New Hampshire, meanwhile, found that 39% of private wells exceeded the state’s Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS), which were established in 2019 and range from 11-18 ng/L depending on the specific PFAS compound. Notably, while the EPA MCLs represent legally enforceable levels accounting for the feasibility of remediation, the agency has also released health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) of zero for PFOA and PFOS.

PFAS in private water are unregulated and expensive to remediate.

In New York State (NYS), nearly one million households rely on private wells for drinking water; despite this, there are currently no standardized well testing procedures and effective well water treatment is unaffordable to many New Yorkers. As of April 2024, the EPA has established federal MCLs for several specific PFAS compounds and mixtures of compounds and its National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) require public water systems to begin monitoring and publicly reporting levels of these PFAS by 2027; if monitoring reveals exceedances of the MCLs, public water systems must also implement solutions to reduce PFAS by 2029. In contrast, there are no standardized testing procedures or enforceable limits for PFAS in private water. Additionally, testing and remediating private wells are both associated with high costs which are unaffordable to many well owners; prices range in hundreds of dollars for PFAS testing and can cost several thousands of dollars for the installation and maintenance of effective filtration systems.

How are states responding to the problem of PFAS in private drinking water?

Several states, including Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina, have already initiated programs offering well testing and financial assistance for filters to protect against PFAS.

- After piloting its PFAS Testing and Assistance (TAP) program in one county in 2024, Colorado will expand it to three additional counties in 2025. The program covers the expenses of testing and a $79 nano pitcher (point-of-use) filter. Residents are eligible if PFOA and/or PFOS in their wells exceeds EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L; filters are free if their household income is ≤80% of the area median income and offered at a 30% discount if this income criteria is not met.

- The New Hampshire (NH) PFAS Removal Rebate Program for Private Wells offers greater flexibility and higher cost coverage than Colorado PFAS TAP, with reimbursements of up to $5000 offered for either point-of-entry or point-of-use treatment system installation and up to $10,000 offered for connection to a public water system. Though other residents may also participate in the program and receive delayed reimbursement, households earning ≤80% of the area median family income are offered the additional assistance of payment directly to a treatment installer or contractor (prior to installation) so as to relieve the applicant of fronting the cost. Eligibility is based on testing showing exceedances of the EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L for PFOA or PFOS or 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (trademarked as “GenX”).

- The North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program offers flexibility similar to New Hampshire in terms of the types of water treatment reimbursed, including multiple point-of-entry and point-of-use filter options as well as connection to public water systems. It is additionally notable for its tiered funding system, with reimbursement amounts ranging from $375 to $10,000 based on both the household’s income and the type of water treatment chosen. The tiered system categorizes program participants based on whether their household income is (1) <200%, (2) 200-400%, or (3) >400% the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Also similar to New Hampshire, payments may be made directly to contractors prior to installation for the lowest income bracket, who qualify for full installation costs; others are reimbursed after the fact. This program uses the aforementioned EPA MCLs for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (“GenX”) and also recognizes the additional EPA MCL of a hazard index of 1.0 for mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, or PFBS.

An opportunity exists to protect New Yorkers.

Launching a program in New York similar to those initiated in Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina was among the priority initiatives described by New York Governor Kathy Hochul in the annual State of the State she delivered in January 2025. In particular, Hochul’s plans to improve water infrastructure included “a pilot program providing financial assistance for private well owners to replace or treat contaminated wells.” This was announced along with a $500 million additional investment beyond New York’s existing $5.5 billion dedicated to water infrastructure, which will also be used to “reduce water bills, combat flooding, restore waterways, and replace lead service lines to protect vulnerable populations, particularly children in underserved communities.” In early 2025, the New York Legislature introduced Senate Bill S3972, which intended to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment. Bipartisan interest in protecting the public from PFAS-contaminated drinking water is further evidenced by a hearing focused on the topic held by the NYS Assembly in November 2024.

Though these efforts would likely initially be confined to a smaller pilot program with limited geographic scope, such a pilot program would aim to inform a broader, statewide intervention. Challenges to planning an intervention of this scope include uncertainty surrounding both the total funding which would be allotted to such a program and its total costs. These costs will be dependent on factors such as the eligibility criteria employed by the state, the proportion of well owners who opt into sampling, and the proportion of tested wells found to have PFAS exceedances (which will further vary based on whether the state adopts EPA MCLs or NYS Department of Health MCLs, which are 10 ng/L for PFOA and PFOS). We allay the uncertainty associated with these numerous possibilities by estimating the numbers of wells serviced and associated costs under various combinations of 10 potential eligibility criteria, 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS testing among eligible wells, and 5 possible rates (5, 25, 50, 75, and 100%) of PFAS>MCL and subsequent POET installation among wells tested.

Scenario Analysis

Key findings

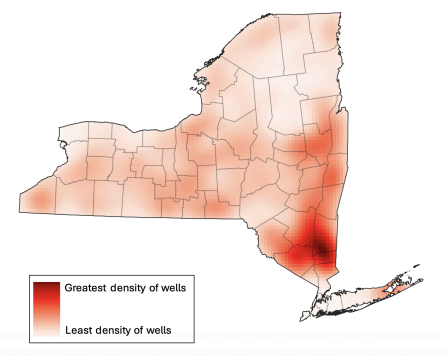

- Over 900,000 residences across NYS are supplied by private drinking wells (Figure 1).

- The three most costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every private well owner (901,441 wells; $1,034,403,547)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) AND/OR belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (725,923 wells; $832,996,643)

- Every well belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 (705,959 wells; $810,087,953)

- The three least costly scenarios were offering testing and installation rebates for (Table 1):

- Every well located within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% of the area median income (22,835 wells; $26,191,688)

- Every well belonging to a household earning <100% of the Federal Poverty Level (92,661 wells; $106,328,398)

- Every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) (93,840 wells; $107,681,400)

- Of six income-based eligibility criteria, household income <$150,000 included the greatest number of wells, whereas location within a census tract in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% the area median income (a definition of low-to-moderate income used for programs coordinated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development), included the fewest wells. This amounts to a cost difference of $783,896,265 between these two eligibility scenarios.

- Six income-based criteria varied dramatically in terms of their inclusion of wells across NYS which fall within either disadvantaged or small communities (Table 2):

- For disadvantaged communities, this ranged from 12% (household income <100% federal poverty level) to 79% (income <$150,000) of all wells within disadvantaged communities being eligible.

- For small communities, this ranged from 2% (census tracts in which at least 51% of households earn below 80% area median income) to 83% (income <$150,000) of all wells within small communities being eligible.

Plan of Action

New York State is already considering a PFAS remediation program (e.g., Senate Bill S3972). The 2025 draft of the bill directed the New York Department of Environmental Conservation to establish an installation grant program and a maintenance rebate program for PFAS removal treatment, and establishes general eligibility criteria and per-household funding amounts. To our knowledge, S3972 did not pass in 2025, but its program provides a strong foundation for potential future action. Our suggestions below resolve some gaps in S3972, including additional detail that could be followed by the implementing agency and overall cost estimates that could be used by the Legislature when considering overall financial impacts.

Recommendation 1. Remediate all disadvantaged wells statewide

We recommend including every well located within a census tract designated as disadvantaged (based on NYS Disadvantaged Community (DAC) criteria) and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000 as the eligibility criteria which protects the widest range of vulnerable New Yorkers. Using this criteria, we estimate a total program cost of approximately $833 million, or $167 million per year if the program were to be implemented over a 5-year period. Even accounting for the other projects which the state will be undertaking at the same time, this annual cost falls well within the additional $500 million which the 2025 State of the State reports will be added in 2025 to an existing $5.5 million state investment in water infrastructure.

Recommendation 2. Target disadvantaged census tracts and household incomes

Wells in DAC census tracts accounts for a variety of disadvantages. Including NYS DAC criteria helps to account for the heterogeneity of challenges experienced by New Yorkers by weighing statistically meaningful thresholds for 45 different indicators across several domains. These include factors relevant to the risk of PFAS exposure, such as land use for industrial purposes and proximity to active landfills.

Wells in low-income households account for cross-sectoral disadvantage. The DAC criteria alone is imperfect:

- Major criticisms include its underrepresentation of rural communities (only 13% of rural census tracts, compared to 26% of suburban and 48% of urban tracts, have been DAC-designated) and failure to account for some key stressors relevant to rural communities (e.g., distance to food stores and in-migration/gentrification).

- Another important note is that wells within DAC communities account for only 10% of all wells within NYS (Table 2). While wells within DAC-designated communities are important to consider, including only DAC wells in an intervention would therefore be very limiting.

- Whereas DAC designation is a binary consideration for an entire census tract, place-based criteria such as this are limited in that any real community comprises a spectrum of socioeconomic status and (dis)advantage.

The inclusion of income-based criteria is useful in that financial strain is a universal indicator of resource constraint which can help to identify the most-in-need across every community. Further, including income-based criteria can widen the program’s eligibility criteria to reach a much greater proportion of well owners (Table 2). Finally, in contrast to the DAC criteria’s binary nature, income thresholds can be adjusted to include greater or fewer wells depending on final budget availability.

- Of the income thresholds evaluated, income <$150,000 is recommended due to its inclusion not only of the greatest number of well owners overall, but also the greatest percentages of wells within disadvantaged and small communities (Table 2). These two considerations are both used by the EPA in awarding grants to states for water infrastructure improvement projects.

- As an alternative to selecting one single income threshold, the state may also consider maximizing cost effectiveness by adopting a tiered rebate system similar to that used by the North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program.

Recommendation 3. Alternatives to POETs might be more cost-effective and accessible

A final recommendation is for the state to maximize the breadth of its well remediation program by also offering reimbursements for point-of-use treatment (POUT) systems and for connecting to public water systems, not just for POET installations. While POETs are effective in PFAS removal, they require invasive changes to household plumbing and prohibitively expensive ongoing maintenance, two factors which may give well owners pause even if they are eligible for an initial installation rebate. Colorado’s PFAS TAP program models a less invasive and extremely cost-effective POUT alternative to POETs. We estimate that if NYS were to provide the same POUT filters as Colorado, the total cost of the program (using the recommended eligibility criteria of location within a DAC-designated census tract and/or belonging to a household with annual income <$150,000) would be $163 million, or $33 million per year across 5 years. This amounts to a total decrease in cost of nearly $670 million if POUTs were to be provided in place of POETs. Connection to public water systems, on the other hand, though a significant initial investment, provides an opportunity to streamline drinking water monitoring and remediation moving forward and eliminates the need for ongoing and costly individual interventions and maintenance.

Conclusion

Well testing and rebate programs provide an opportunity to take preventative action against the serious health threats associated with PFAS exposure through private drinking water. Individuals reliant on PFAS-contaminated private wells for drinking water are likely to ingest the chemicals on a daily basis. There is therefore no time to waste in taking action to break this chain of exposure. New York State policymakers are already engaged in developing this policy solution; our recommendations can help both those making the policy and those tasked with implementing it to best serve New Yorkers. Our analysis shows that a program to mitigate PFAS in private drinking water is well within scope of current action and that fair implementation of such a program can help those who need it most and do so in a cost-effective manner.

While the Safe Drinking Water Act regulates the United States’ public drinking water supplies, there is no current federal government to regulate private wells. Most states also lack regulation of private wells. Introducing new legislation to change this would require significant time and political will. Political will to enact such a change is unlikely given resource limitations, concerns around well owners’ privacy, and the current time in which the EPA is prioritizing deregulation.

Decreasing blood serum levels is likely to decrease negative health impacts. Exposure via drinking water is particularly associated with elevated serum PFAS levels, while appropriate water filtration has demonstrated efficacy in reducing serum PFAS levels.

We estimated total costs assuming that 75% of eligible wells are tested for PFAS and that of these tested wells, 25% are both found to have PFAS exceedances and proceed to have filter systems installed. This PFAS exceedance/POET installation rate was selected because it falls between the rates of exceedances observed when private well sampling was conducted in Wisconsin and New Hampshire in recent years.

For states which do not have their own tools for identifying disadvantaged communities, the Social Vulnerability Index developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) may provide an alternative option to help identify those most in need.

Too Hot not to Handle

Every region in the U.S. is experiencing year after year of record-breaking heat. More households now require home cooling solutions to maintain safe and liveable indoor temperatures. Over the last two decades, U.S. consumers and the private sector have leaned heavily into purchasing and marketing conventional air conditioning (AC) systems, such as central air conditioning, window units and portable ACs, to cool down overheating homes.

While AC can offer immediate relief, the rapid scaling of AC has created dangerous vulnerabilities: rising energy bills are straining people’s wallets and increasing utility debt, while surging electricity demand increases reliance on high-polluting power infrastructure and mounts pressure on an aging power grid increasingly prone to blackouts. There is also an increasing risk of elevated demand for electricity during a heat wave, overloading the grid and triggering prolonged blackouts, causing whole regions to lose their sole cooling strategy. This disruption could escalate into a public health emergency as homes and people overheat, leading to hundreds of deaths.

What Americans need to be prepared for more extreme temperatures is a resilient cooling strategy. Resilient cooling is an approach that works across three interdependent systems — buildings, communities, and the electric grid — to affordably maintain safe indoor temperatures during extreme heat events and reduce power outage risks.

This toolkit introduces a set of Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling and outlines a set of actionable policy options and levers for state and local governments to foster broader access to resilient cooling technologies and strategies.

This toolkit introduces a set of Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling and outlines a set of actionable policy options and levers for state and local governments to foster broader access to resilient cooling technologies and strategies. For example, states are the primary regulators of public utility commissions, architects of energy and building codes, and distributors of federal and state taxpayer dollars. Local governments are responsible for implementing building standards and zoning codes, enforcing housing and health codes, and operating public housing and retrofit programs that directly shape access to cooling.

The Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling for a robust resilient cooling strategy are:

- Expand Cooling Access and Affordability. Ensuring that everyone can affordably access cooling will reduce the population-wide risk of heat-related illness and death in communities and the resulting strain on healthcare systems. Targeted financial support tools — such as subsidies, rebates, and incentives — can reduce both upfront and ongoing costs of cooling technologies, thereby lowering barriers and enabling broader adoption.

- Incorporate Public Health Outcomes as a Driver of Resilience. Indoor heat exposure and heat-driven factors that reduce indoor air quality — such as pollutant accumulation and mold-promoting humidity — are health risks. Policymakers should embed heat-related health risks into building codes, energy standards, and guidelines for energy system planning, including establishing minimum indoor temperature and air quality requirements, integrating health considerations into energy system planning standards, and investing in multi-solving community system interventions like green infrastructure.

- Advance Sustainability Across the Cooling Lifecycle. Rising demand for air conditioning is intensifying the problem it aims to solve by increasing electricity consumption, prolonging reliance on high-polluting power plants, and leaking refrigerants that release powerful greenhouse gases. Policymakers can adopt codes and standards that reduce reliance on high-emission energy sources and promote low-global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants and passive cooling strategies.

- Promote Solutions for Grid Resilience. The U.S. electric grid is struggling to keep up with rising demand for electricity, creating potential risks to communities’ cooling systems. Policymakers can proactively identify potential vulnerabilities in energy systems’ ability to sustain safe indoor temperatures. Demand-side management strategies, distributed energy resources, and grid-enhancing technologies can prepare the electric grid for increased energy demand and ensure its reliability during extreme heat events.

- Build a Skilled Workforce for Resilient Cooling. Resilient cooling provides an opportunity to create pathways to good-paying jobs, reduce critical workforce gaps, and bolster the broader economy. Investing in a workforce that can design, install, and maintain resilient cooling systems can strengthen local economies, ensure preparedness for all kinds of risks to the system, and bolster American innovation.

By adopting a resilient cooling strategy, state and local policymakers can address today’s overlapping energy, health, and affordability crises, advance American-made innovation, and ensure their communities are prepared for the hotter decades ahead.

A Holistic Framework for Measuring and Reporting AI’s Impacts to Build Public Trust and Advance AI

As AI becomes more capable and integrated throughout the United States economy, its growing demand for energy, water, land, and raw materials is driving significant economic and environmental costs, from increased air pollution to higher costs for ratepayers. A recent report projects that data centers could consume up to 12% of U.S. electricity by 2028, underscoring the urgent need to assess the tradeoffs of continued expansion. To craft effective, sustainable resource policies, we need clear standards for estimating the data centers’ true energy needs and for measuring and reporting the specific AI applications driving their resource consumption. Local and state-level bills calling for more oversight of utility rates and impacts to ratepayers have received bipartisan support, and this proposal builds on that momentum.

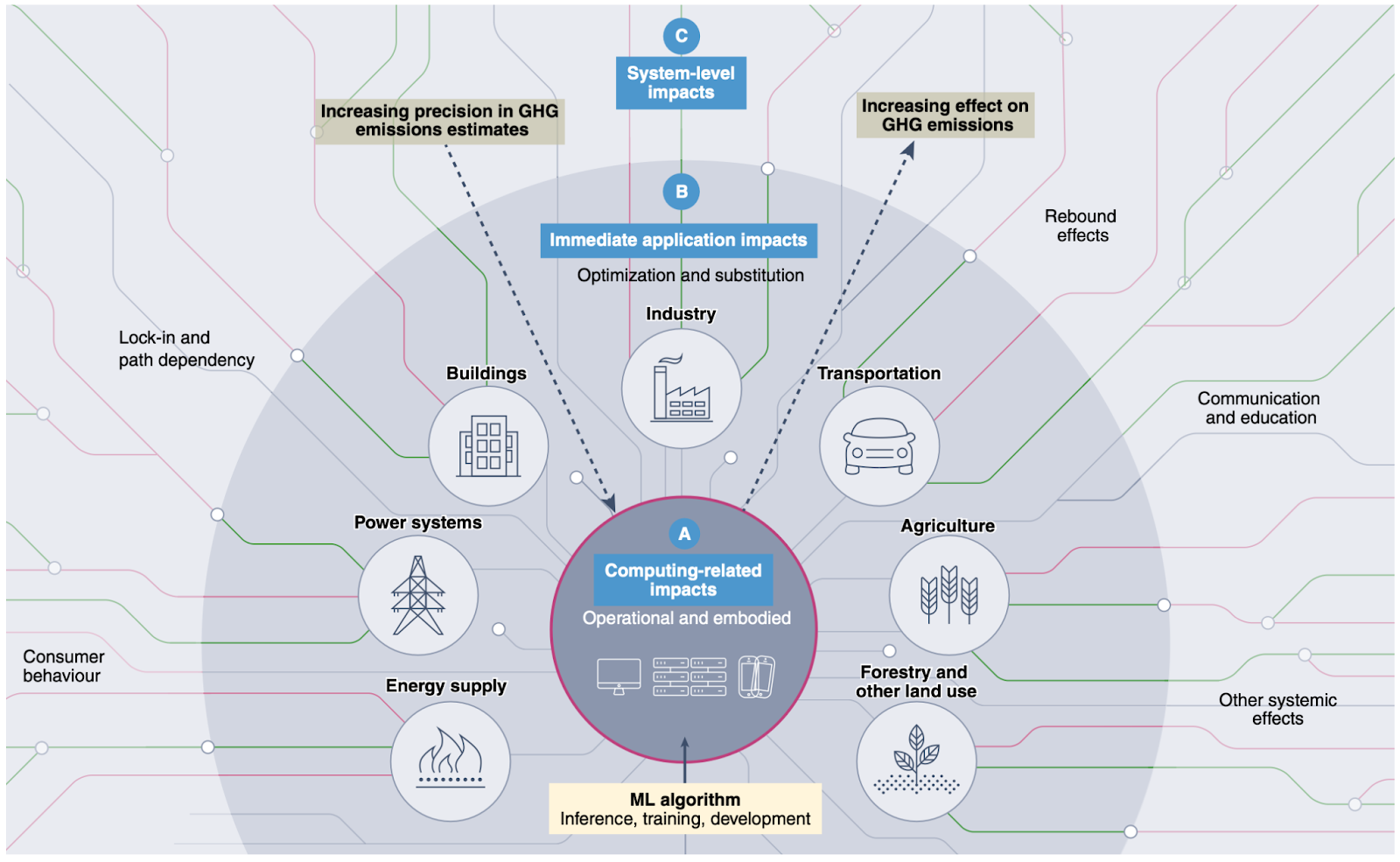

In this memo, we draw on research proposing a holistic evaluation framework for characterizing AI’s environmental impacts, which establishes three categories of impacts arising from AI: (1) Computing-related impacts; (2) Immediate application impacts; and (3) System-level impacts . Concerns around AI’s computing-related impacts, e.g. energy and water use due to AI data centers and hardware manufacturing, have become widely known with corresponding policy starting to be put into place. However, AI’s immediate application and system-level impacts, which arise from the specific use cases to which AI is applied, and the broader socio-economic shifts resulting from its use, remain poorly understood, despite their greater potential for societal benefit or harm.

To ensure that policymakers have full visibility into the full range of AI’s environmental impacts we recommend that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) oversee creation of frameworks to measure the full range of AI’s impacts. Frameworks should rely on quantitative measurements of the computing and application related impacts of AI and qualitative data based on engagements with the stakeholders most affected by the construction of data centers. NIST should produce these frameworks based on convenings that include academic researchers, corporate governance personnel, developers, utility companies, vendors, and data center owners in addition to civil society organizations. Participatory workshops will yield new guidelines, tools, methods, protocols and best practices to facilitate the evolution of industry standards for the measurement of the social costs of AI’s energy infrastructures.

Challenge and Opportunity

Resource consumption associated with AI infrastructures is expanding quickly, and this has negative impacts, including asthma from air pollution associated with diesel backup generators, noise pollution, light pollution, excessive water and land use, and financial impacts to ratepayers. A lack of transparency regarding these outcomes and public participation to minimize these risks losing the public’s trust, which in turn will inhibit the beneficial uses of AI. While there is a huge amount of capital expenditure and a massive forecasted growth in power consumption, there remains a lack of transparency and scientific consensus around the measurement of AI’s environmental impacts with respect to data centers and their related negative externalities.

A holistic evaluation framework for assessing AI’s broader impacts requires empirical evidence, both qualitative and quantitative, to influence future policy decisions and establish more responsible, strategic technology development. Focusing narrowly on carbon emissions or energy consumption arising from AI’s computing related impacts is not sufficient. Measuring AI’s application and system-level impacts will help policymakers consider multiple data streams, including electricity transmission, water systems and land use in tandem with downstream economic and health impacts.

Regulatory and technical attempts so far to develop scientific consensus and international standards around the measurement of AI’s environmental impacts have focused on documenting AI’s computing-related impacts, such as energy use, water consumption, and carbon emissions required to build and use AI. Measuring and mitigating AI’s computing-related impacts is necessary, and has received attention from policymakers (e.g. the introduction of the AI Environmental Impacts Act of 2024 in the U.S., provisions for environmental impacts of general-purpose AI in the EU AI Act, and data center sustainability targets in the German Energy Efficiency Act). However, research by Kaack et al (2022) highlights that impacts extend beyond computing. AI’s application impacts, which arise from the specific use cases for which AI is deployed (e.g. AI’s enabled emissions, such as application of AI to oil and gas drilling have much greater potential scope for positive or negative impacts compared to AI’s computing impacts alone, depending on how AI is used in practice). Finally, AI’s system-level impacts, which include even broader, cascading social and economic impacts associated with AI energy infrastructures, such as increased pressure on local utility infrastructure leading to increased costs to ratepayers, or health impacts to local communities due to increased air pollution, have the greatest potential for positive or negative impacts, while being the most challenging to measure and predict. See Figure 1 for an overview.

from Kaack et al. (2022). Effectively understanding and shaping AI’s impacts will require going beyond impacts arising from computing alone, and requires consideration and measurement of impacts arising from AI’s uses (e.g. in optimizing power systems or agriculture) and how AI’s deployment throughout the economy leads to broader systemic shifts, such as changes in consumer behavior.

Effective policy recommendations require more standardized measurement practices, a point raised by the Government Accountability Office’s recent report on AI’s human and environmental effects, which explicitly calls for increasing corporate transparency and innovation around technical methods for improved data collection and reporting. But data should also include multi-stakeholder engagement to ensure there are more holistic evaluation frameworks that meet the needs of specific localities, including state and local government officials, businesses, utilities, and ratepayers. Furthermore, while states and municipalities are creating bills calling for more data transparency and responsibility, including in California, Indiana, Oregon, and Virginia, the lack of federal policy means that data center owners may move their operations to states that have fewer protections in place and similar levels of existing energy and data transmission infrastructure.

States are also grappling with the potential economic costs of data center expansion. Ohio’s Policy Matters found that tax breaks for data center owners are hurting tax revenue streams that should be used to fund public services. In Michigan, tax breaks for data centers are increasing the cost of water and power for the public while undermining the state’s climate goals. Some Georgia Republicans have stated that data center companies should “pay their way.” While there are arguments that data centers can provide useful infrastructure, connectivity, and even revenue for localities, a recent report shows that at least ten states each lost over $100 million a year in revenue to data centers because of tax breaks. The federal government can help create standards that allow stakeholders to balance the potential costs and benefits of data centers and related energy infrastructures. We now have an urgent need to increase transparency and accountability through multi-stakeholder engagement, maximizing economic benefits while reducing waste.

Despite the high economic and policy stakes, critical data needed to assess the full impacts—both costs and benefits—of AI and data center expansion remains fragmented, inconsistent, or entirely unavailable. For example, researchers have found that state-level subsidies for data center expansion may have negative impacts on state and local budgets, but this data has not been collected and analyzed across states because not all states publicly release data about data center subsidies. Other impacts, such as the use of agricultural land or public parks for transmission lines and data center siting, must be studied at a local and state level, and the various social repercussions require engagement with the communities who are likely to be affected. Similarly, estimates on the economic upsides of AI vary widely, e.g. the estimated increase in U.S. labor productivity due to AI adoption ranges from 0.9% to 15% due in large part to lack of relevant data on AI uses and their economic outcomes, which can be used to inform modeling assumptions.

Data centers are highly geographically clustered in the United States, more so than other industrial facilities such as steel plants, coal mines, factories, and power plants (Fig. 4.12, IEA World Energy Outlook 2024). This means that certain states and counties are experiencing disproportionate burdens associated with data center expansion. These burdens have led to calls for data center moratoriums or for the cessation of other energy development, including in states like Indiana. Improved measurement and transparency can help planners avoid overly burdensome concentrations of data center infrastructure, reducing local opposition.

With a rush to build new data center infrastructure, states and localities must also face another concern: overbuilding. For example, Microsoft recently put a hold on parts of its data center contract in Wisconsin and paused another in central Ohio, along with contracts in several other locations across the United States and internationally. These situations often stem from inaccurate demand forecasting, prompting utilities to undertake costly planning and infrastructure development that ultimately goes unused. With better measurement and transparency, policymakers will have more tools to prepare for future demands, avoiding the negative social and economic impacts of infrastructure projects that are started but never completed.

While there have been significant developments in measuring the direct, computing-related impacts of AI data centers, public participation is needed to fully capture many of their indirect impacts. Data centers can be constructed so they are more beneficial to communities while mitigating their negative impacts, e.g. by recycling data center heat, and they can also be constructed to be more flexible by not using grid power during peak times. However, this requires collaborative innovation and cross-sector translation, informed by relevant data.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Develop a database of AI uses and framework for reporting AI’s immediate applications in order to understand the drivers of environmental impacts.

The first step towards informed decision-making around AI’s social and environmental impacts is understanding what AI applications are actually driving data center resource consumption. This will allow specific deployments of AI systems to be linked upstream to compute-related impacts arising from their resource intensity, and downstream to impacts arising from their application, enabling estimation of immediate application impacts.

The AI company Anthropic demonstrated a proof-of-concept categorizing queries to their Claude language model under the O*NET database of occupations. However, O*NET was developed in order to categorize job types and tasks with respect to human workers, which does not exactly align with current and potential uses of AI. To address this, we recommend that NIST works with relevant collaborators such as the U.S. Department of Labor (responsible for developing and maintaining the O*NET database) to develop a database of AI uses and applications, similar to and building off of O*NET, along with guidelines and infrastructure for reporting data center resource consumption corresponding to those uses. This data could then be used to understand particular AI tasks that are key drivers of resource consumption.

Any entity deploying a public-facing AI model (that is, one that can produce outputs and/or receive inputs from outside its local network) should be able to easily document and report its use case(s) within the NIST framework. A centralized database will allow for collation of relevant data across multiple stakeholders including government entities, private firms, and nonprofit organizations.

Gathering data of this nature may require the reporting entity to perform analyses of sensitive user data, such as categorizing individual user queries to an AI model. However, data is to be reported in aggregate percentages with respect to use categories without attribution to or listing of individual users or queries. This type of analysis and data reporting is well within the scope of existing, commonplace data analysis practices. As with existing AI products that rely on such analyses, reporting entities are responsible for performing that analysis in a way that appropriately safeguards user privacy and data protection in accordance with existing regulations and norms.

Recommendation 2. NIST should create an independent consortium to develop a system-level evaluation framework for AI’s environmental impacts, while embedding robust public participation in every stage of the work.

Currently, the social costs of AI’s system-level impacts—the broader social and economic implications arising from AI’s development and deployment—are not being measured or reported in any systematic way. These impacts fall heaviest on the local communities that host the data centers powering AI: the financial burden on ratepayers who share utility infrastructure, the health effects of pollutants from backup generators, the water and land consumed by new facilities, and the wider economic costs or benefits of data-center siting. Without transparent metrics and genuine community input, policymakers cannot balance the benefits of AI innovation against its local and regional burdens. Building public trust through public participation is key when it comes to ensuring United States energy dominance and national security interests in AI innovation, themes emphasized in policy documents produced by the first and second Trump administrations.

To develop evaluation frameworks in a way that is both scientifically rigorous and broadly trusted, NIST should stand up an independent consortium via a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA). A CRADA allows NIST to collaborate rapidly with non-federal partners while remaining outside the scope of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), and has been used, for example, to convene the NIST AI Safety Institute Consortium. Membership will include academic researchers, utility companies and grid operators, data-center owners and vendors, state, local, Tribal, and territorial officials, technologists, civil-society organizations, and frontline community groups.

To ensure robust public engagement, the consortium should consult closely with FERC’s Office of Public Participation (OPP)—drawing on OPP’s expertise in plain-language outreach and community listening sessions—and with other federal entities that have deep experience in community engagement on energy and environmental issues. Drawing on these partners’ methods, the consortium will convene participatory workshops and listening sessions in regions with high data-center concentration—Northern Virginia, Silicon Valley, Eastern Oregon, and the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex—while also making use of online comment portals to gather nationwide feedback.

Guided by the insights from these engagements, the consortium will produce a comprehensive evaluation framework that captures metrics falling outside the scope of direct emissions alone. These system-level metrics could encompass (1) the number, type, and duration of jobs created; (2) the effects of tax subsidies on local economies and public services; (3) the placement of transmission lines and associated repercussions for housing, public parks, and agriculture; (4) the use of eminent domain for data-center construction; (5) water-use intensity and competing local demands; and (6) public-health impacts from air, light, and noise pollution. NIST will integrate these metrics into standardized benchmarks and guidance.

Consortium members will attend public meetings, engage directly with community organizations, deliver accessible presentations, and create plain-language explainers so that non-experts can meaningfully influence the framework’s design and application. The group will also develop new guidelines, tools, methods, protocols, and best practices to facilitate industry uptake and to evolve measurement standards as technology and infrastructure grow.

We estimate a cost of approximately $5 million over two years to complete the work outlined in recommendation 1 and 2, covering staff time, travel to at least twelve data-center or energy-infrastructure sites across the United States, participant honoraria, and research materials.

Recommendation 3. Mandate regular measurement and reporting on relevant metrics by data center operators.

Voluntary reporting is the status quo, via e.g. corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reports, but voluntary reporting has so far been insufficient for gathering necessary data. For example, while the technology firm OpenAI, best known for their highly popular ChatGPT generative AI model, holds a significant share of the search market and likely corresponding share of environmental and social impacts arising from the data centers powering their products, OpenAI chooses not to publish ESG reports or data in any other format regarding their energy consumption or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In order to collect sufficient data at the appropriate level of detail, reporting must be mandated at the local, state, or federal level. At the state level, California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB -253, SB-219) requires that large companies operating within the state report their GHG emissions in accordance with the GHG Protocol, administered by the California Air Resources Board (CARB).

At the federal level, the EU’s Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive (CSRD), which requires firms operating within the EU to report a wide variety of data related to environmental sustainability and social governance, could serve as a model for regulating companies operating within the U.S. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) GHG Reporting Program already requires emissions reporting by operators and suppliers associated with large GHG emissions sources, and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) collects detailed data on electricity generation and fuel consumption through forms 860 and 923. With respect to data centers specifically, the Department of Energy (DOE) could require that developers who are granted rights to build AI data center infrastructure on public lands perform the relevant measurement and reporting, and more broadly reporting could be a requirement to qualify for any local, state or federal funding or assistance provided to support buildout of U.S. AI infrastructure.

Recommendation 4. Incorporate measurements of social cost into AI energy and infrastructure forecasting and planning.

There is a huge range in estimates of future data center energy use, largely driven by uncertainty around the nature of demands from AI. This uncertainty stems in part from a lack of historical and current data on which AI use cases are most energy intensive and how those workloads are evolving over time. It also remains unclear the extent to which challenges in bringing new resources online, such as hardware production limits or bottlenecks in permitting, will influence growth rates. These uncertainties are even more significant when it comes to the holistic impacts (i.e. those beyond direct energy consumption) described above, making it challenging to balance costs and benefits when planning future demands from AI.

To address these issues, accurate forecasting of demand for energy, water, and other limited resources must incorporate data gathered through holistic measurement frameworks described above. Further, the forecasting of broader system-level impacts must be incorporated into decision-making around investment in AI infrastructure. Forecasting needs to go beyond just energy use. Models should include predicting energy and related infrastructure needs for transmission, the social cost of carbon in terms of pollution, the effects to ratepayers, and the energy demands from chip production.

We recommend that agencies already responsible for energy-demand forecasting—such as the Energy Information Administration at the Department of Energy—integrate, in line with the NIST frameworks developed above, data on the AI workloads driving data-center electricity use into their forecasting models. Agencies specializing in social impacts, such as the Department of Health and Human Services in the case of health impacts, should model social impacts and communicate those to EIA and DOE for planning purposes. In parallel, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) should update its new rule on long-term regional transmission planning, to explicitly include consideration of the social costs corresponding to energy supply, demand and infrastructure retirement/buildout across different scenarios.

Recommendation 5. Transparently use federal, state, and local incentive programs to reward data-center projects that deliver concrete community benefits.

Incentive programs should attach holistic estimates of the costs and benefits collected under the frameworks above, and not purely based on promises. When considering using incentive programs, policymakers should ask questions such as: How many jobs are created by data centers and for how long do those jobs exist, and do they create jobs for local residents? What tax revenue for municipalities or states is created by data centers versus what subsidies are data center owners receiving? What are the social impacts of using agricultural land or public parks for data center construction or transmission lines? What are the impacts to air quality and other public health issues? Do data centers deliver benefits like load flexibility and sharing of waste heat?

Grid operators (Regional Transmission Organizations [RTOs] and Independent System Operators [ISOs]) can leverage interconnection queues to incentivize data center operators to justify that they have sufficiently considered the impacts to local communities when proposing a new site. FERC recently approved reforms to processing the interconnect request queue, allowing RTOs to implement a “first-ready first-served” approach rather than a first-come first-served approach, wherein proposed projects can be fast-tracked based on their readiness. A similar approach could be used by RTOs to fast-track proposals that include a clear plan for how they will benefit local communities (e.g. through load flexibility, heat reuse, and clean energy commitments), grounded in careful impact assessment.

There is the possibility of introducing state-level incentives in states with existing significant infrastructure. Such incentives could be determined in collaboration with the National Governors Association, who have been balancing AI-driven energy needs with state climate goals.

Conclusion

Data centers have an undeniable impact on energy infrastructures and the communities living close to them. This impact will continue to grow alongside AI infrastructure investment, which is expected to skyrocket. It is possible to shape a future where AI infrastructure can be developed sustainably, and in a way that responds to the needs of local communities. But more work is needed to collect the necessary data to inform government decision-making. We have described a framework for holistically evaluating the potential costs and benefits of AI data centers, and shaping AI infrastructure buildout based on those tradeoffs. This framework includes: establishing standards for measuring and reporting AI’s impacts, eliciting public participation from impacted communities, and putting gathered data into action to enable sustainable AI development.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

Data centers are highly spatially concentrated largely due to reliance on existing energy and data transmission infrastructure; it is more cost-effective to continue building where infrastructure already exists, rather than starting fresh in a new region. As long as the cost of performing the proposed impact assessment and reporting in established regions is less than that of the additional overhead of moving to a new region, data center operators are likely to comply with regulations in order to stay in regions where the sector is established.

Spatial concentration of data centers also arises due to the need for data center workloads with high data transmission requirements, such as media streaming and online gaming, to have close physical proximity to users in order to reduce data transmission latency. In order for AI to be integrated into these realtime services, data center operators will continue to need presence in existing geographic regions, barring significant advances in data transmission efficiency and infrastructure.

bad for national security and economic growth. So is infrastructure growth that harms the local communities in which it occurs.

Researchers from Good Jobs First have found that many states are in fact losing tax revenue to data center expansion: “At least 10 states already lose more than $100 million per year in tax revenue to data centers…” More data is needed to determine if data center construction projects coupled with tax incentives are economically advantageous investments on the parts of local and state governments.

The DOE is opening up federal lands in 16 locations to data center construction projects in the name of strengthening America’s energy dominance and ensuring America’s role in AI innovation. But national security concerns around data center expansion should also consider the impacts to communities who live close to data centers and related infrastructures.

Data centers themselves do not automatically ensure greater national security, especially because the critical minerals and hardware components of data centers depend on international trade and manufacturing. At present, the United States is not equipped to contribute the critical minerals and other materials needed to produce data centers, including GPUs and other components.

Federal policy ensures that states or counties do not become overburdened by data center growth and will help different regions benefit from the potential economic and social rewards of data center construction.

Developing federal standards around transparency helps individual states plan for data center construction, allowing for a high-level, comparative look at the energy demand associated with specific AI use cases. It is also important for there to be a federal intervention because data centers in one state might have transmission lines running through a neighboring state, and resultant outcomes across jurisdictions. There is a need for a national-level standard.

Current cost-benefit estimates can often be extremely challenging. For example, while municipalities often expect there will be economic benefits attached to data centers and that data center construction will yield more jobs in the area, subsidies and short-term jobs in construction do not necessarily translate into economic gains.

To improve the ability of decision makers to do quality cost-benefit analysis, the independent consortium described in Recommendation 2 will examine both qualitative and quantitative data, including permitting histories, transmission plans, land use and eminent domain cases, subsidies, jobs numbers, and health or quality of life impacts in various sites over time. NIST will help develop standards in accordance with this data collection, which can then be used in future planning processes.

Further, there is customer interest in knowing their AI is being sourced from firms implementing sustainable and socially responsible practices. These efforts which can be used in marketing communications and reported as a socially and environmentally responsible practice in ESG reports. This serves as an additional incentive for some data center operators to participate in voluntary reporting and maintain operations in locations with increased regulation.

Advance AI with Cleaner Air and Healthier Outcomes

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming industries, driving innovation, and tackling some of the world’s most pressing challenges. Yet while AI has tremendous potential to advance public health, such as supporting epidemiological research and optimizing healthcare resource allocation, the public health burden of AI due to its contribution to air pollutant emissions has been under-examined. Energy-intensive data centers, often paired with diesel backup generators, are rapidly expanding and degrading air quality through emissions of air pollutants. These emissions exacerbate or cause various adverse health outcomes, from asthma to heart attacks and lung cancer, especially among young children and the elderly. Without sufficient clean and stable energy sources, the annual public health burden from data centers in the United States is projected to reach up to $20 billion by 2030, with households in some communities located near power plants supplying data centers, such as those in Mason County, WV, facing over 200 times greater burdens than others.

Federal, state, and local policymakers should act to accelerate the adoption of cleaner and more stable energy sources and address AI’s expansion that aligns innovation with human well-being, advancing the United States’ leadership in AI while ensuring clean air and healthy communities.

Challenge and Opportunity

Forty-six percent of people in the United States breathe unhealthy levels of air pollution. Ambient air pollution, especially fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is linked to 200,000 deaths each year in the United States. Poor air quality remains the nation’s fifth highest mortality risk factor, resulting in a wide range of immediate and severe health issues that include respiratory diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and premature deaths.

Data centers consume vast amounts of electricity to power and cool the servers running AI models and other computing workloads. According to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the growing demand for AI is projected to increase the data centers’ share of the nation’s total electricity consumption to as much as 12% by 2028, up from 4.4% in 2023. Without enough sustainable energy sources like nuclear power, the rapid growth of energy-intensive data centers is likely to exacerbate ambient air pollution and its associated public health impacts.

Data centers typically rely on diesel backup generators for uninterrupted operation during power outages. While the total operation time for routine maintenance of backup generators is limited, these generators can create short-term spikes in PM2.5, NOx, and SO2 that go beyond the baseline environmental and health impacts associated with data center electricity consumption. For example, diesel generators emit 200–600 times more NOx than natural gas-fired power plants per unit of electricity produced. Even brief exposure to high-level NOx can aggravate respiratory symptoms and hospitalizations. A recent report to the Governor and General Assembly of Virginia found that backup generators at data centers emitted approximately 7% of the total permitted pollution levels for these generators in 2023. Based on the Environmental Protection Agency’s COBRA modeling tool, the public health cost of these emissions in Virginia is estimated at approximately $200 million, with health impacts extending to neighboring states and reaching as far as Florida. In Memphis, Tennessee, a set of temporary gas turbines powering a large AI data center, which has not undergone a complete permitting process, is estimated to emit up to 2,000 tons of NOx annually. This has raised significant health concerns among local residents and could result in a total public health burden of $160 million annually. These public health concerns coincide with a paradigm shift that favors dirty energy and potentially delays sustainability goals.

In 2023 alone, air pollution attributed to data centers in the United States resulted in an estimated $5 billion in health-related damages, a figure projected to rise up to $20 billion annually by 2030. This projected cost reflects an estimated 1,300 premature deaths in the United States per year by the end of the decade. While communities near data centers and power plants bear the greatest burden, with some households facing over 200 times greater impacts than others, the health impacts of these facilities extend to communities across the nation. The widespread health impacts of data centers further compound the already uneven distribution of environmental costs and water resource stresses imposed by AI data centers across the country.

While essential for mitigating air pollution and public health risks, transitioning AI data centers to cleaner backup fuels and stable energy sources such as nuclear power presents significant implementation hurdles, including lengthy permitting processes. Clean backup generators that match the reliability of diesel remain limited in real-world applications, and multiple key issues must be addressed to fully transition to cleaner and more stable energy.