Measuring and Standardizing AI’s Energy and Environmental Footprint to Accurately Access Impacts

The rapid expansion of artificial intelligence (AI) is driving a surge in data center energy consumption, water use, carbon emissions, and electronic waste—yet these environmental impacts, and how they will change in the future, remain largely opaque. Without standardized metrics and reporting, policymakers and grid operators cannot accurately track or manage AI’s growing resource footprint. Currently, companies often use outdated or narrow measures (like Power Usage Effectiveness, PUE) and purchase renewable credits to obscure true emissions. Their true carbon footprint may be as much as 662% higher than the figures they report. A single hyperscale AI data center can guzzle hundreds of thousands of gallons of water per day and contribute to a “mountain” of e-waste, yet only about a quarter of data center operators even track what happens to retired hardware.

This policy memo proposes a set of congressional and federal executive actions to establish comprehensive, standardized metrics for AI energy and environmental impacts across model training, inference, and data center infrastructure. We recommend that Congress directs the Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to design, collect, monitor and disseminate uniform and timely data on AI’s energy footprint, while designating the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to coordinate a multi-agency council that coordinates implementation. Our plan of action outlines steps for developing metrics (led by DOE, NIST, and the Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]), implementing data reporting (with the Energy Information Administration [EIA], National Telecommunications and Information Administration [NTIA], and industry), and integrating these metrics into energy and grid planning (performed by DOE’s grid offices and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission [FERC]). By standardizing how we measure AI’s footprint, the U.S. can be better prepared for the growth in power consumption while maintaining its leadership in artificial intelligence.

Challenge and Opportunity

Inconsistent metrics and opaque reporting make future AI power‑demand estimates extremely uncertain, leaving grid planners in the dark and climate targets on the line.

AI’s Opaque Footprint

Generative AI and large-scale cloud computing are driving an unprecedented increase in energy demand. AI systems require tremendous amounts of computing power both during training (the AI development period) and inference (when AI is used in real world applications). The rapid rise of this new technology is already straining energy and environmental systems at an unprecedented scale. Data centers consumed an estimated 415 Terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity in 2024 (roughly 1.5% of global power demand), and with AI adoption accelerating, the International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that data center energy use could more than double to 945 TWh by 2030. This is an added load comparable to powering an entire country the size of Sweden or even Germany. There are a range of projections of AI’s energy consumption, with some estimates suggesting even more rapid growth than the IEA. Estimates suggest that much of this growth will be concentrated in the United States.

The large divergence in estimates for AI-driven electricity demand stem from the different assumptions and methods used in each study. One study uses one of the parameters like the AI Query volume (the number of requests made by users for AI answers), another tries to estimate energy demand from the estimated supply of AI related hardware. Some estimate the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of data center growth under different growth scenarios. Different authors make various assumptions about chip shipment growth, workload mix (training vs inference), efficiency gains, and per‑query energy. Amidst this fog of measurement confusion, energy suppliers are caught by surges in demand from new compute infrastructure on top of existing demands from sources like electric vehicles and manufacturing. Electricity grid operators in the United States typically plan for gradual increases in power demand that can be met with incremental generation and transmission upgrades. But if the rapid build-out of AI data centers, on top of other growing power demands, pushes global demand up by an additional hundreds of terawatt hours annually this will shatter the steady-growth assumption embedded in today’s models. Planners need far more granular, forward-looking forecasting methods to avoid driving up costs for rate-payers, last-minute scrambles to find power, and potential electricity reliability crises.

This surge in power demand also threatens to undermine climate progress. Many new AI data centers require 100–1000 megawatts (MW), equivalent to the demands of a medium-sized city, while grid operators are faced with connection lead times of over 2 years to connect to clean energy supplies. In response to these power bottlenecks some regional utilities, unable to supply enough clean electricity, have even resorted to restarting retired coal plants to meet data center loads, undermining local climate goals and efficient operation. Google’s carbon emissions rose 48% over the past five years and Microsoft’s by 23.4% since 2020, largely due to cloud computing and AI.

In spite of the risks to the climate, carbon emissions data is often obscured: firms often claim “carbon neutrality” via purchased clean power credits, while their actual local emissions go unreported. One analysis found Big Tech (Amazon, Meta) data centers may emit up to 662% more CO₂ than they publicly report. For example, Meta’s 2022 data center operations reported only 273 metric tons CO₂ (using market-based accounting with credits), but over 3.8 million metric tons CO₂ when calculated by actual grid mix according to one analysis—a more than 19,000-fold increase. Similarly, AI’s water impacts are largely hidden. Each interactive AI query (e.g. a short session with a language model) can indirectly consume half a liter of fresh water through data center cooling, contributing to millions of gallons used by AI servers—but companies rarely disclose water usage per AI workload. This lack of transparency masks the true environmental cost of AI, hinders accountability, and impedes smart policymaking.

Outdated and Fragmented Metrics

Legacy measures like Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) miss what is important for AI compute efficiency, such as water consumption, hardware manufacturing, and e-waste.

The metrics currently used to gauge data center efficiency are insufficient for AI-era workloads. Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE), the two-decades-old standard, gives only a coarse snapshot of facility efficiency under ideal conditions. PUE measures total power delivered to a datacenter versus how much of that power actually makes it to the IT equipment inside. The more power used (e.g. for cooling), the worse the PUE ratio will be. However, PUE does not measure how efficiently the IT equipment actually uses the power delivered to it. Think about a car that reports how much fuel reaches the engine but not the miles per gallon of that engine. You can ensure that the fuel doesn’t leak out of the line on its way to the engine, but that engine might not be running efficiently. A good PUE is the equivalent of saying that fuel isn’t leaking out on its way to the engine; it might tell you that a data center isn’t losing too much energy to cooling, but won’t flag inefficient IT equipment. An AI training cluster with a “good” PUE (around 1.1) could still be wasteful if the hardware or software is poorly optimized.

In the absence of updated standards, companies “report whatever they choose, however they choose” regarding AI’s environmental impact. Few report water usage or lifecycle emissions. Only 28% of operators track hardware beyond its use, and just 25% measure e-waste, resulting in tons of servers and AI chips quietly ending up in landfills. This data gap leads to misaligned incentives—for instance, firms might build ever-larger models and data centers, chasing AI capabilities, without optimizing for energy or material efficiency because there is no requirement or benchmark to do so.

Opportunities for Action

Standardizing metrics for AI’s energy and environmental footprint presents a win-win opportunity. By measuring and disclosing AI’s true impacts, we can manage them. With better data, policymakers can incentivize efficiency innovations (from chip design to cooling to software optimization) and target grid investments where AI load is rising. Industry will benefit too: transparency can highlight inefficiencies (e.g. low server utilization or high water-cooled heat that could be recycled) and spur cost-saving improvements. Importantly, several efforts are already pointing the way. In early 2024, bicameral lawmakers introduced the Artificial Intelligence Environmental Impacts Act, aiming to have the EPA study AI’s environmental footprint and develop measurement standards and a voluntary reporting system via NIST. Internationally, the European Union’s upcoming AI Act will require large AI systems to report energy use, resource consumption, and other life cycle impacts, and the ISO is preparing “sustainable AI” standards for energy, water, and materials accounting. The U.S. can build on this momentum. A recent U.S. Executive Order (Jan 2025) already directed DOE to draft reporting requirements for AI data centers covering their entire lifecycle—from material extraction and component manufacturing to operation and retirement—including metrics for embodied carbon (greenhouse-gas emissions that are “baked into” the physical hardware and facilities before a single watt is consumed to run a model), water usage, and waste heat. It also launched a DOE–EPA “Grand Challenge” to push the PUE ratio below 1.1 and minimize water usage in AI facilities. These signals show that there is willingness to address the problem. Now is the time to implement a comprehensive framework that standardizes how we measure AI’s environmental impact. If we seize this opportunity, we can ensure innovation in AI is driven by clean energy, a smarter grid, and less environmental and economic burden on communities.

Plan of Action

To address this challenge, Congress should authorize DOE and NIST to lead an interagency working group and a consortium of public, private and academic communities to enact a phased plan to develop, implement, and operationalize standardized metrics, in close partnership with industry.

Recommendation 1. Identify and Assign Agency Mandates

Creating and Implementing this measurement framework requires concerted action by multiple federal agencies, each leveraging its mandate. The Department of Energy (DOE) should serve as the co-lead federal agency driving this initiative. Within DOE, the Office of Critical and Emerging Technologies (CET) can coordinate AI-related efforts across DOE programs, given its focus on AI and advanced tech integration. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) will also act as a co-lead for this initiative leading the metrics development and standardization effort as described, convening experts and industry. The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) will act as the coordinating body for this multi-agency effort. OSTP, alongside the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), can ensure alignment with broader energy, environment, and technology policy. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should take charge of environmental data collection and oversight. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) should play a supporting role by addressing grid and electricity market barriers. FERC should streamline interconnection processes for new data center loads, perhaps creating fast-track procedures for projects that commit to high efficiency and demand flexibility.

Congressional leadership and oversight will be key. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and House Energy & Commerce Committee (which oversee energy infrastructure and data center energy issues) should champion legislation and hold hearings on AI’s energy demands. The House Science, Space, and Technology Committee and Senate Commerce, Science, & Transportation Committee (which oversee NIST, and OSTP) should support R&D funding and standards efforts. Environmental committees (like Senate Environment and Public Works, House Natural Resources) should address water use and emissions. Ongoing committee oversight can ensure agencies stay on schedule and that recommendations turn into action (for example, requiring an EPA/DOE/NIST joint report to Congress within a set timeframe(s).

Congress should mandate a formal interagency task force or working group, co-led by the Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) serving as the coordinating body and involving all relevant federal agencies. This body will meet regularly to track progress, resolve overlaps or gaps, and issue public updates. By clearly delineating responsibilities, The federal government can address the measurement problem holistically.

Recommendation 2. Develop a Comprehensive AI Energy Lifecycle Measurement Framework

A complete view of AI’s environmental footprint requires metrics that span the full lifecycle, including every layer from chip to datacenter, workload drivers, and knock‑on effects like water use and electricity prices.

Create new standardized metrics that capture AI’s energy and environmental footprint across its entire lifecycle—training, inference, data center operations (cooling/power), and hardware manufacturing/disposal. This framework should be developed through a multi-stakeholder process led by NIST in partnership with DOE and EPA, and in consultation with industry, academia as well as state and local governments.

Key categories should include:

- Data Center Efficiency Metrics: how effectively do data centers use power?

- AI Hardware & Compute Metrics: e.g. Performance per Watt (PPW)—the throughput of AI computations per watt of power.

- Cooling and Water Metrics: How much energy and water are being used to cool these systems?

- Environmental Impact Metrics: What is the carbon intensity per AI task?

- Composite or Lifecycle Metrics: Beyond a single point in time, what are the lifetime characteristics of impact for these systems?

Designing standardized metrics

NIST, with its measurement science expertise, should coordinate the development of these metrics in an open process, building on efforts like NIST’s AI Standards Working Group—a standing body chartered under the Interagency Committee on Standards Policy which brings together technical stakeholders to map the current AI-standards landscape, spot gaps, and coordinate U.S. positions and research priorities. The goal is to publish a standardized metrics framework and guidelines that industry can begin adopting voluntarily within 12 months. Where possible, leverage existing standards (for example, those from the Green Grid consortium on PUE and Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE), or IEEE/ISO standards for energy management) and tailor them to AI’s unique demands. Crucially, these metrics must be uniformly defined to enable apples-to-apples comparisons and periodically updated as technology evolves.

Review, Governance, and improving metrics

We recommend establishing a Metrics Review Committee (led by NIST with DOE/EPA and external experts) to refine the metrics whenever needed, host stakeholder workshops, and public updates. This continuous improvement process will keep the framework current with new AI model types, cooling tech, and hardware advances, ensuring relevance into the future. For example, when we move from the current model of chatbots responding to queries to agentic AI systems that plan, act, remember, and iterate autonomously, traditional “energy per query” metrics no longer capture the full picture.

Recommendation 3. Operationalize Data Collection, Reporting, Analysis and Integrate it into Policy

Start with a six‑month voluntary reporting program, and gradually move towards a mandatory reporting mechanism which feeds straight into EIA outlooks and FERC grid planning.

The task force should solicit inputs via a Request for Information (RFI) — similar to DOE’s recent RFI on AI infrastructure development, asking data center operators, AI chip manufacturers, cloud providers, utilities, and environmental groups to weigh in on feasible reporting requirements and data sharing methods. Within 12 months of starting, this taskforce should complete (a) a draft AI energy lifecycle measurement framework (with standardized definitions for energy, water, carbon, and e-waste metrics across training and data center operations), and (b) an initial reporting template for technology companies, data centers and utilities to pilot.

With standardized metrics in hand, we must shift the focus to implementation and data collection at scale. In the beginning, a voluntary AI energy reporting program can be launched by DOE and EPA (with NIST overseeing the standards). This program would provide guidance to AI developers (e.g. major model-training companies), cloud service providers, and data center operators to report their metrics on an annual or quarterly basis.

After a trial run of the voluntary program, Congress should enact legislation to create a mandatory reporting regime that borrows the best features of existing federal disclosure programs. One useful template is EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, which obliges any facility that emits more than 25,000 tons of CO₂ equivalent per year to file standardized, verifiable electronic reports. The same threshold logic could be adapted for data centers (e.g., those with more than 10 MW of IT load) and for AI developers that train models above a specified compute budget. A second model is DOE/EIA’s Form EIA-923 “Power Plant Operations Report,” whose structured monthly data flow straight into public statistics and planning models. An analogous “Form EIA-AI-01” could feed the Annual Energy Outlook and FERC reliability assessments without creating a new bureaucracy. EIA could also consider adding specific questions or categories in the Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey and Form EIA-861 to identify energy use by data centers and large computing loads. This may involve coordinating with the Census Bureau to leverage industrial classification data (e.g., NAICS codes for data hosting facilities) so that baseline energy/water consumption of the “AI sector” is measured in national statistics. NTIA, which often convenes multi stakeholder processes on technology policy, can host industry roundtables to refine reporting processes and address any concerns (e.g. data confidentiality, trade secrets). NTIA can help ensure that reporting requirements are not overly burdensome to smaller AI startups by working out streamlined methods (perhaps aggregated reporting via cloud providers, for instance). DOE’s Grid Deployment Office (GDO) and Office of Electricity (OE), with better data, should start integrating AI load growth into grid planning models and funding decisions. For example, GDO could prioritize transmission projects that will deliver clean power to regions with clusters of AI data centers, based on EIA data showing rapid load increases. FERC, for its part, can use the reported data to update its reliability and resource adequacy guidelines and possibly issue guidance for regional grid operators (RTOs/ISOs) to explicitly account for projected large computing loads in their plans.

This transparency will let policymakers, researchers, and consumers track improvements (e.g., is the energy per AI training decreasing over time?) and identify leaders/laggards. It will also inform mid-course adjustments that if certain metrics prove too hard to collect or not meaningful, NIST can update the standards. The Census Bureau can contribute by testing the inclusion of questions on technology infrastructure in its Economic Census 2027 and annual surveys, ensuring that the economic data of the tech sector includes environmental parameters (for example, collecting data center utility expenditures, which correlate with energy use). Overall, this would establish an operational reporting system and start feeding the data into both policy and market decisions.

Through these recommendations, responsible offices have clear roles: DOE spearheads efficiency measures in data center initiatives; OE (Office of Electricity and GDO (Grid Deployment Office) use the data to guide grid improvements; NIST creates and maintains the measurement standards; EPA oversees environmental data and impact mitigation; EIA institutionalizes energy data collection and dissemination; FERC adapts regulatory frameworks for reliability and resource adequacy; OSTP coordinates the interagency strategy and keeps the effort a priority; NTIA works with industry to smooth data exchange and involve them; and Census Bureau integrates these metrics into broader economic data. See the table below.Meanwhile, non-governmental actors like utilities, AI companies, and data center operators must not only be data providers but partners. Utilities could use this data to plan investments and can share insights on demand response or energy sourcing; AI developers and data center firms will implement new metering and reporting practices internally, enabling them to compete on efficiency (similar to car companies competing on miles per gallon ratings). Together, these actions create a comprehensive approach: measuring AI’s footprint, managing its growth, and mitigating its environmental impacts through informed policy.

Conclusion

AI’s extraordinary capabilities should not come at the expense of our energy security or environmental sustainability. This memo outlines how we can effectively operationalize measuring AI’s environmental footprint by establishing standardized metrics and leveraging the strengths of multiple agencies to implement them. By doing so, we can address a critical governance gap: what isn’t measured cannot be effectively managed. Standard metrics and transparent reporting will enable AI’s growth while ensuring that data center expansion is met with commensurate increases in clean energy, grid upgrades, and efficiency gains.

The benefits of these actions are far-reaching. Policymakers will gain tools to balance AI innovation with energy and environment goals. For example, by being able to require improvements if an AI service is energy-inefficient, or to fast-track permits for a new data center that meets top sustainability standards. Communities will be better protected: with data in hand, we can avoid scenarios where a cluster of AI facilities suddenly strains a region’s power or water resources without local officials knowing in advance. Instead, requirements for reporting and coordination can channel resources (like new transmission lines or water recycling systems) to those communities ahead of time. The AI industry itself will benefit by building trust and reducing the risk of backlash or heavy-handed regulation; a clear, federal metrics framework provides predictability and a level playing field (everyone measures the same way), and it showcases responsible stewardship of technology. Moreover, emphasizing energy efficiency and resource reuse can reduce operating costs for AI companies in the long run, a crucial advantage as energy prices and supply chain concerns grow.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

While there are existing metrics like PUE for data centers, they don’t capture the full picture of AI’s impacts. Traditional metrics focus mainly on facility efficiency (power and cooling) and not on the computational intensity of AI workloads or the lifecycle impacts. AI operations involve unique factors—for example, training a large AI model can consume significant energy in a short time, and using that AI model continuously can draw power 24/7 across distributed locations. Current standards are outdated and inconsistent: one data center might report a low PUE but could be using water recklessly or running hardware inefficiently. AI-specific metrics are needed to measure things like energy per training run, water per cooling unit, or carbon per compute task, which no standard reporting currently requires. In short, general data center standards weren’t designed for the scale and intensity of modern AI. By developing AI-specific metrics, we ensure that the unique resource demands of AI are monitored and optimized, rather than lost in aggregate averages. This helps pinpoint where AI can be made more efficient (e.g., via better algorithms or chips)—an opportunity not visible under generic metrics.

AI’s environmental footprint is a cross-cutting issue, touching on energy infrastructure, environmental impact, technological standards, and economic data. No single agency has the full expertise or jurisdiction to cover all aspects. Each agency will have clearly defined roles (as outlined in the Plan of Action). For instance, NIST develops the methodology, DOE/EPA collect and use the data, EIA disseminates it, and FERC/Congress use it to adjust policies. This collaborative approach prevents blind spots. A single-agency approach would likely miss critical elements (for instance, a purely DOE-led effort might not address e-waste or standardized methods, which NIST and EPA can). The good news is that frameworks for interagency cooperation already exist, and this initiative aligns with broader administration priorities (clean energy, reliable grid, responsible AI). Thus, while it involves multiple agencies, OSTP and the White House will ensure everyone stays synchronized. The result will be a comprehensive policy that each agency helps implement according to its strength, rather than a piecemeal solution. See below:

Roles and Responsibilities to Measure AI’s Environmental Impact

- Department of Energy (DOE): DOE should serve as the co-lead federal agency driving this initiative. Within DOE, the Office of Critical and Emerging Technologies (CET) can coordinate AI-related efforts across DOE programs, given its focus on AI and advanced tech integration. DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) can lead on promoting energy-efficient data center technologies and practices (e.g. through R&D programs and partnerships), while the Office of Electricity (OE) and Grid Deployment Office address grid integration challenges (ensuring AI data centers have access to reliable clean power). DOE should also collaborate with utilities and FERC to plan for AI-driven electricity demand growth and to encourage demand-response or off-peak operation strategies for energy-hungry AI clusters.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST): NIST will also act as a co-lead for this initiative leading the metrics development and standardization effort as described, convening experts and industry. NIST should revive or expand its AI Standards Coordination Working Group to focus on sustainability metrics, and ultimately publish technical standards or reference materials for measuring AI energy use, water use, and emissions. NIST is also suited to host stakeholder consortium on AI environmental impacts, working in tandem with EPA and DOE.

- White House, including the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP): OSTP will act as the coordinating body for this multi-agency effort. OSTP, alongside the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), can ensure alignment with broader climate and tech policy (such as the U.S. Climate Strategy and AI initiatives). The Administration can also use the Federal Chief Sustainability Officer and OMB guidance to integrate AI energy metrics into federal sustainability requirements (for instance, updating OMB’s memos on data center optimization to include AI-specific measures).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): EPA should take charge of environmental data collection and oversight. In the near term, EPA (with DOE) would conduct the comprehensive study of AI’s environmental impacts, examining AI systems’ lifecycle emissions, water and e-waste. EPA’s expertise in greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting will ensure metrics like carbon intensity are rigorously quantified (e.g. using location-based grid emissions factors rather than unreliable REC-based accounting).

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC): FERC plays a supporting role by addressing grid and electricity market barriers. FERC should streamline interconnection processes for new data center loads, perhaps creating fast-track procedures for projects that commit to high efficiency and demand flexibility. FERC can ensure that regional grid reliability assessments start accounting for projected AI/data center load growth using data.

- Congressional Committees: Congressional leadership and oversight will be key. The Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and House Energy & Commerce Committee (which oversee energy infrastructure and data center energy issues) should champion legislation and hold hearings on AI’s energy demands. The House Science, Space, and Technology Committee and Senate Commerce, Science, & Transportation Committee (which oversee NIST and OSTP) should support R&D funding and standards efforts. Environmental committees (like Senate Environment and Public Works, House Natural Resources) should address water use and emissions. Ongoing committee oversight can ensure agencies stay on schedule and that recommendations turn into action (for example, requiring the EPA/DOE/NIST joint report to Congress in four years as the Act envisions, and then moving on any further legislative needs).

The plan requires high-level, standardized data that balances transparency with practicality. Companies running AI operations (like cloud providers or big AI model developers) would report metrics such as: total electricity consumed for AI computations (annually), average efficiency metrics (e.g. PUE, Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE), and WUE for their facilities), water usage for cooling, and e-waste generated (amount of hardware decommissioned and how it was handled). These data points are typically already collected internally for cost and sustainability tracking but the difference is they would be reported in a consistent format and possibly to a central repository. For utilities, if involved, they might report aggregated data center load in their service territory or significant new interconnections for AI projects (much of this is already in utility planning documents). See below for examples.

Metrics to Illustrate the Types of Shared Information

- Data Center Efficiency Metrics: Power Usage Effectiveness (PUE) (refined for AI workloads), Data Center Infrastructure Efficiency (DCIE) which measures IT versus total facility power (the inverse of PUE), Energy Reuse Factor (ERF) to quantify how much waste heat is reused on-site, and Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE) to link energy use with carbon emissions (kg CO₂ per kWh). These give a holistic view of facility efficiency and carbon intensity, beyond just power usage.

- AI Hardware & Compute Metrics: Performance per Watt (PPW)—the throughput of AI computations (like FLOPS or inferences) per watt of power, which encourages energy-efficient model training and inference. Compute Utilization—ensuring expensive AI accelerators (GPUs/TPUs) are well-utilized rather than idling (tracking average utilization rates). Training energy per model—total kWh or emissions per training run (possibly normalized by model size or training-hours). Inference efficiency—energy per 1000 queries or per inference for deployed models. Idle power draw—measure and minimize the energy hardware draws when not actively in use.

- Cooling and Water Metrics: Cooling Energy Efficiency Ratio (EER)—the output cooling power per watt of energy input, to gauge cooling system efficiency. Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE)—liters of water used per kWh of IT compute, or simply total water used for cooling per year. These help quantify and benchmark the significant water and electricity overhead for thermal management in AI data centers.

- Environmental Impact Metrics: Carbon Intensity per AI Task—CO₂ emitted per training or per 1000 inferences, which could be aggregated to an organizational carbon footprint for AI operations. Greenhouse Gas emissions per kWh—linking energy use to actual emissions based on grid mix or backup generation. Also, e-waste metrics—such as total hardware weight decommissioned annually, or a recycling ratio. For instance, tracking the tons of servers/chips retired and the fraction recycled versus landfilled can illuminate the life cycle impact.

- Composite or Lifecycle Metrics: Develop ways to combine these factors to rate overall sustainability of AI systems. For example, an “AI Sustainability Score” could incorporate energy efficiency, renewables use, cooling efficiency, and end-of-life recycling. Another idea is an “AI Energy Star” rating for AI hardware or cloud services that meet certain efficiency and transparency criteria, modeled after Energy Star appliance ratings.

No, the intention is not to force disaggregation down to proprietary details (e.g., exactly how a specific algorithm uses energy) but rather to get macro-level indicators. Regarding trade secrets or sensitive info, the data collected (energy, water, emissions) is not about revealing competitive algorithms or data, it’s about resource use. These are analogous to what many firms already publish in sustainability reports (power usage, carbon footprint), just more uniformly. There will be provisions to protect any sensitive facility-level data (e.g., EIA could aggregate or anonymize certain figures in public releases). The goal is transparency about environmental impact, not exposure of intellectual property.

Once collected, the data will become a powerful tool for evidence-based policymaking and oversight. At the strategic level, DOE and the White House can track whether the AI sector is becoming more efficient or not—for instance, seeing trends in energy-per-AI-training decreasing (good) or total water use skyrocketing (a flag for action).

Energy planning: EIA will incorporate the numbers into its models, which guide national energy policy and investment. If data shows that AI is driving, say, an extra 5% electricity demand growth in certain regions, DOE’s Grid Deployment Office and FERC can respond by facilitating grid expansions or reliability measures in those areas.

Climate policy: EPA can use reported emissions data to update greenhouse gas inventories and identify if AI/data centers are becoming a significant source—if so, that could shape future climate regulations or programs (ensuring this sector contributes to emissions reduction goals).

Water resource management: If we see large water usage by AI in drought-prone areas, federal and state agencies can work on water recycling or alternative cooling initiatives.

Research and incentives: DOE’s R&D programs (through ARPA-E or National Labs) can target the pain points revealed—e.g., if e-waste volumes are high, fund research into longer-lasting hardware or recycling tech; if certain metrics like Energy Reuse Factor are low, push demonstration projects for waste heat reuse.

This could inform everything from ESG investment decisions to local permitting. For example, a company planning a new data center might be asked by local authorities, “What’s your expected PUE and water usage? The national average for AI data centers is X—will you do better?” In essence, the data ensures the government and public can hold the AI industry accountable for progress (or regress) on sustainability. By integrating these data into models and policies, the government can anticipate and avert problems (like grid strain or high emissions) before they grow, and steer the sector toward solutions.

AI services and data centers are worldwide, so consistency in how we measure impacts is important. The U.S. effort will be informed by and contribute to international standards. Notably, the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) is already developing criteria for sustainable AI, including energy, raw materials, and water metrics across the AI lifecycle NIST, which often represents the U.S. in global standards bodies, is involved and will ensure that our metrics framework aligns with ISO’s emerging standards. Similarly, the EU’s AI Act also has requirements for reporting AI energy and resource use. By moving early on our own metrics, the U.S. can actually help shape what those international norms look like, rather than react to them. This initiative will encourage U.S. agencies to engage in forums like the Global Partnership on AI (GPAI) or bilateral tech dialogues to promote common sustainability reporting frameworks. In the end, aligning metrics internationally will create a more level playing field—ensuring that AI companies can’t simply shift operations to avoid transparency. If the U.S., EU, and others all require similar disclosures, it reinforces responsible practices everywhere.

Shining a light on energy and resource use can drive new innovation in efficiency. Initially, there may be modest costs—for example, installing better sub-meters in data centers or dedicating staff time to reporting. However, these costs are relatively small in context. Many leading companies already track these metrics internally for cost management and corporate sustainability goals. We are recommending formalizing and sharing that information. Over time, the data collected can reduce costs: companies will identify wasteful practices (maybe servers idling, or inefficient cooling during certain hours) and correct them, saving on electricity and water bills. There is also an economic opportunity in innovation: as efficiency becomes a competitive metric, we expect increased R&D into low-power AI algorithms, advanced cooling, and longer-life hardware. Those innovations can improve performance per dollar as well. Moreover, policy support can offset any burdens—for instance, the government can provide technical assistance or grants to smaller firms to help them improve energy monitoring. We should also note that unchecked resource usage carries its own risks to innovation: if AI’s growth starts causing blackouts or public backlash due to environmental damage, that would seriously hinder AI progress.

Speed Grid Connection Using ‘Smart AI Fast Lanes’ and Competitive Prizes

Innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) and computing capacity is essential for U.S. competitiveness and national security. However, AI data center electricity use is growing rapidly. Data centers already consume more than 4% of U.S. electricity annually and could rise to 6% to 12% of U.S. electricity by 2028. At the same time, electricity rates are rising for consumers across the country, with transmission and distribution infrastructure costs a major driver of these increases. For the first time in fifteen years, the U.S. is experiencing a meaningful increase in electricity demand. Electricity use from data centers already consumes more than 25% of electricity in Virginia, which leads the world in data center installations. Data center electricity load growth results in real economic and environmental impacts for local communities. It also represents a national policy trial on how the U.S. responds to rising power demand from the electrification of homes, transportation, and manufacturing– important technology transitions for cutting carbon emissions and air pollution.

Federal and state governments need to ensure that the development of new AI and data center infrastructure does not increase costs for consumers, impact the environment, and exacerbate existing inequalities. “Smart AI Fast Lanes” is a policy and infrastructure investment framework that ensures the U.S. leads the world in AI while building an electricity system that is clean, affordable, reliable, and equitable. Leveraging innovation prizes that pay for performance, coupled with public-private partnerships, data center providers can work with the Department of Energy, the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI), the Department of Commerce, National Labs, state energy offices, utilities, and the Department of Defense to drive innovation to increase energy security while lowering costs.

Challenge and Opportunity

Targeted policies can ensure that the development of new AI and data center infrastructure does not increase costs for consumers, impact the environment, and exacerbate existing energy burdens. Allowing new clean power sources co-located or contracted with AI computing facilities to connect to the grid quickly, and then manage any infrastructure costs associated with that new interconnection, would accelerate the addition of new clean generation for AI while lowering electricity costs for homes and businesses.

One of the biggest bottlenecks in many regions of the U.S. in adding much-needed capacity to the electricity grid are the so-called “interconnection queues”. There are different regional requirements for power plants to complete (often, a number of studies on how a project affects grid infrastructure) before they are allowed to connect. Solar, wind, and battery projects represented 95% of the capacity waiting in interconnection queues in 2023. The operator of Texas’ power grid, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), uses a “connect and manage” interconnection process that results in faster interconnections of new energy supplies than the rest of the country. Instead of requiring each power plant to complete lengthy studies of needed system-wide infrastructure investments before connecting to the grid, the “connect and manage” approach in Texas gets power plants online quicker than a “studies first” approach. Texas manages any risks that arise using the power markets and system-wide planning efforts. The results are clear: the median time from an interconnection request to commercial operations in Texas was four years, compared to five years in New York and more than six and a half years in California.

“Smart AI Fast Lanes” expands the spirit of the Texas “connect and manage” approach nationwide for data centers and clean energy, and adds to it investment and innovation prizes to speed up the process, ensure grid reliability, and lower costs.

Data center providers would work with the Department of Energy, the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI), the Department of Commerce, National Laboratories, state energy offices, utilities, and the Department of Defense to speed up interconnection queues, spur innovation in efficiency, and re-invest in infrastructure, to increase energy security and lower costs.

Why FESI Should Lead ‘Smart AI Fast Lanes’

With FESI managing this effort, the process can move faster than the government acting alone. FESI is an independent, non-profit, agency-related foundation that was created by Congress in the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 to help the Department of Energy achieve its mission and accelerate “the development and commercialization of critical energy technologies, foster public-private partnerships, and provide additional resources to partners and communities across the country supporting solutions-driven research and innovation that strengthens America’s energy and national security goals”. Congress has created many other agency-related foundations, such as the Foundation for NIH, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, and the National Park Foundation, which was created in 1935. These agency-related foundations have a demonstrated record of raising external funding to leverage federal resources and enabling efficient public-private partnerships. As a foundation supporting the mission of the Department of Energy, FESI has a unique opportunity to quickly respond to emergent priorities and create partnerships to help solve energy challenges.

As an independent organization, FESI can leverage the capabilities of the private sector, academia, philanthropies, and other organizations to enable collaboration with federal and state governments. FESI can also serve as an access point to opening up additional external investment, and shared risk structures and clear rules of engagement make emerging energy technologies more attractive to institutional capital. For example, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation awards grants that are matched with non-federal private, philanthropic, or local funding sources that multiply the impact of any federal investments. In addition, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation has partnered with the Department of Defense and external funding sources to enhance coastal resilience near military installations. Both AI compute capabilities and energy resilience are of strategic importance to the Department of Defense, Department of Energy, and other agencies, and leveraging public-private partnerships is a key pathway to enhance capabilities and security. FESI leading a Smart AI Fast Lanes initiative could be a force multiplier to enable rapid deployment of clean AI compute capabilities that are good for communities, companies, and national security.

Use Prizes to Lessen Cost and Maximize Return

The Department of Energy has long used prize competitions to spur innovation and accelerate access to funding and resources. Prize competitions with focused objectives but unstructured pathways for success enables the private sector to compete and advance innovation without requiring a lot of federal capacity and involvement. Federal prize programs pay for performance and results, while also providing a mechanism to crowd in additional philanthropic and private sector investment. In the Smart AI Fast Lane framework, FESI could use prizes to support energy innovation from AI data centers while working with the Department of Energy’s Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER) to enable a repeatable and scalable public private partnership program. These prizes would be structured so that there is a low administrative and operational effort required for FESI itself, with other groups such as American-Made, National Laboratories, or organizations like FAS, helping to provide technical expertise to review and administer prize applications. This can ensure quality while enabling scalable growth.

Plan of Action

Here’s how “Smart AI Fast Lanes” would work. For any proposed data center investment of more than 250 MW, companies could apply to work with FESI. Successful application would leverage public, private, and philanthropic funds and technical assistance. Projects would be required to increase clean energy supplies, achieve world-leading data center energy efficiency, invest in transmission and distribution infrastructure, and/or deploy virtual power plants for grid flexibility.

Recommendation 1. Use a “Smart AI Fast Lane” Connection Fee to Quickly Connect to the Grid, Further Incentivized by a “Bring Your Own Power” Prize

New large AI data center loads choosing the “Smart AI Fast Lane” would pay a fee to connect to the grid without first completing lengthy pre-connection cost studies. Those payments would go into a fund, managed and overseen by FESI, that would be used to cover any infrastructure costs incurred by regional grids for the first three years after project completion. The fee could be a flat fee based on data center size, or structured as an auction, enabling the data centers bidding the highest in a region to be at the front of the line. This enables the market to incentivize the highest priority additions. Alternatively, large load projects could choose to do the studies first and remain in the regular – and likely slower – interconnection queue to avoid the fee.

In addition, FESI could facilitate a “Bring Your Own Power” prize award that is a combination of public, private, and philanthropic funds that data center developers can match to contract for new, additional zero-emission electricity generated locally that covers twice as much as the data center uses annually. For data centers committing to this “Smart AI Fast Lane” process, both the data center and the clean energy supply would receive accelerated priority in the interconnection queue and technical assistance from National Laboratories. This leverages economies of scale for projects, lowers the cost of locally-generated clean electricity, and gets clean energy connected to the grid quicker. Prize resources would support a “connect and manage” interconnection approach to cover 75% of the costs of any required infrastructure for local clean power projects resulting from the project. FESI prize resources could further supplement these payments to upgrade electrical infrastructure in areas of national need for new electricity supplies to maintain electricity reliability. These include areas assessed by the North American Reliability Corporation to have a high risk of an electricity shortfall in the coming years, such as the Upper Midwest or Gulf Coast, or areas with an elevated risk such as California, the Great Plains, Texas, the Mid-Atlantic, or the Northeast.

Recommendation 2. Create an Efficiency Prize To Establish World-Leading Energy and Water Efficiency at AI Data Centers

Data centers have different design configurations that affect how much energy and water are needed to operate. Data centers use electricity for computing, but also for the cooling systems needed for computing equipment, and there are innovation opportunities to increase the efficiency of both. One historical measure of AI data center energy efficiency is Power Use Effectiveness (PUE), which is the total facility annual energy use, divided by the computing equipment annual energy use, with values closer to 1.0 being more efficient. Similarly, Water Use Effectiveness (WUE) is measured as total annual water use divided by the computing equipment annual energy use, with closer to zero being more efficient. We should continue to push for improvement in PUE and WUE, but these are incomplete current metrics to drive deep innovation because they do nor reflect how much computing power is provided and do not assess impacts in the broader infrastructure energy system. While there have been multiple different metrics for data center energy efficiency proposed over the past several years, what is important for innovation is to improve the efficiency of how much AI computing work we get for the amount of energy and water used. Just like efficiency in a car is measured in miles per gallon (MPG), we need to measure the “MPG” of how AI data centers perform work and then create incentives and competition for continuous improvements. There could be different metrics for different types of AI training and inference workloads, but a starting point could be the tokens per kilowatt-hour of electricity used. A token is a word or portion of a word that AI foundation models use for analysis. Another way could be to measure the efficiency of computing performance, or FLOPS, per kilowatt-hour. The more analysis an AI model or data center can perform using the same amount of energy, the more energy efficient it is.

FESI could deploy sliding scale innovation prizes based on data center size for new facilities that demonstrate leading edge AI data center MPG. These could be based on efficiency targets for tokens per kilowatt-hour, FLOPS per kilowatt-hour, top-performing PUE, or other metrics of energy efficiency. Similar prizes could be provided for water use efficiency, within different classes of cooling technologies that exceed best-in-class performance. These prizes could be modeled after the USDA’s agency-related foundation’s FFAR Egg-Tech Prize, which was a program that was easy to administer and has had great success. A secondary benefit of an efficiency innovation prize is continuous competition for improvement, and open information about best-in-class data center facilities.

Fig. 1. Power Use Efficiency (PUE) and Water Use Efficiency (WUE) values for Data Centers Source: LBNL 2024

Recommendation 3. Create Prizes to Maximize Transmission Throughput and Upgrade Grid Infrastructure

FESI could award prizes for rapid deployment of reconductoring, new transmission, or grid enhancing technologies to increase the transmission capacity for any project in DOE’s Coordinated Interagency Authorizations and Permit Program. Similarly, FESI could award prizes for utilities to upgrade local distribution infrastructure beyond the direct needs for the project to reduce future electricity rate cases, which will keep electricity costs affordable for residential customers. The Department of Energy already has authority to finance up to $2.5 billion in the Transmission Facilitation Program, a revolving fund administered by the Grid Deployment Office (GDO) that helps support transmission infrastructure. These funds could be used for public-private partnerships in a national interest electric transmission corridor and necessary to accommodate an increase in electricity demand across more than one state or transmission planning region.

Recommendation 4. Develop Prizes That Reward Flexibility and End-Use Efficiency Investments

Flexibility in how and when data centers use electricity can meaningfully reduce the stress on the grid. FESI should award prizes to data centers that demonstrate best-in-class flexibility through smart controls and operational improvements. Prizes could also be awarded to utilities hosting data centers that reduce summer and winter peak loads in the local service territory. Prizes for utilities that meet home weatherization targets and deploy virtual power plants could help reduce costs and grid stress in local communities hosting AI data centers.

Conclusion

The U.S. is facing the risk of electricity demand outstripping supplies in many parts of the country, which would be severely detrimental to people’s lives, to the economy, to the environment, and to national security. “Smart AI Fast Lanes” is a policy and investment framework that can rapidly increase clean energy supply, infrastructure, and demand management capabilities.

It is imperative that the U.S. addresses the growing demand from AI and data centers, so that the U.S. remains on the cutting edge of innovation in this important sector. How the U.S. approaches and solves the challenge of new demand from AI, is a broader test on how the country prepares its infrastructure for increased electrification of vehicles, buildings, and manufacturing, as well as how the country addresses both carbon pollution and the impacts from climate change. The “Smart AI Fast Lanes” framework and FESI-run prizes will enable U.S. competitiveness in AI, keep energy costs affordable, reduce pollution, and prepare the country for new opportunities.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

A Holistic Framework for Measuring and Reporting AI’s Impacts to Build Public Trust and Advance AI

As AI becomes more capable and integrated throughout the United States economy, its growing demand for energy, water, land, and raw materials is driving significant economic and environmental costs, from increased air pollution to higher costs for ratepayers. A recent report projects that data centers could consume up to 12% of U.S. electricity by 2028, underscoring the urgent need to assess the tradeoffs of continued expansion. To craft effective, sustainable resource policies, we need clear standards for estimating the data centers’ true energy needs and for measuring and reporting the specific AI applications driving their resource consumption. Local and state-level bills calling for more oversight of utility rates and impacts to ratepayers have received bipartisan support, and this proposal builds on that momentum.

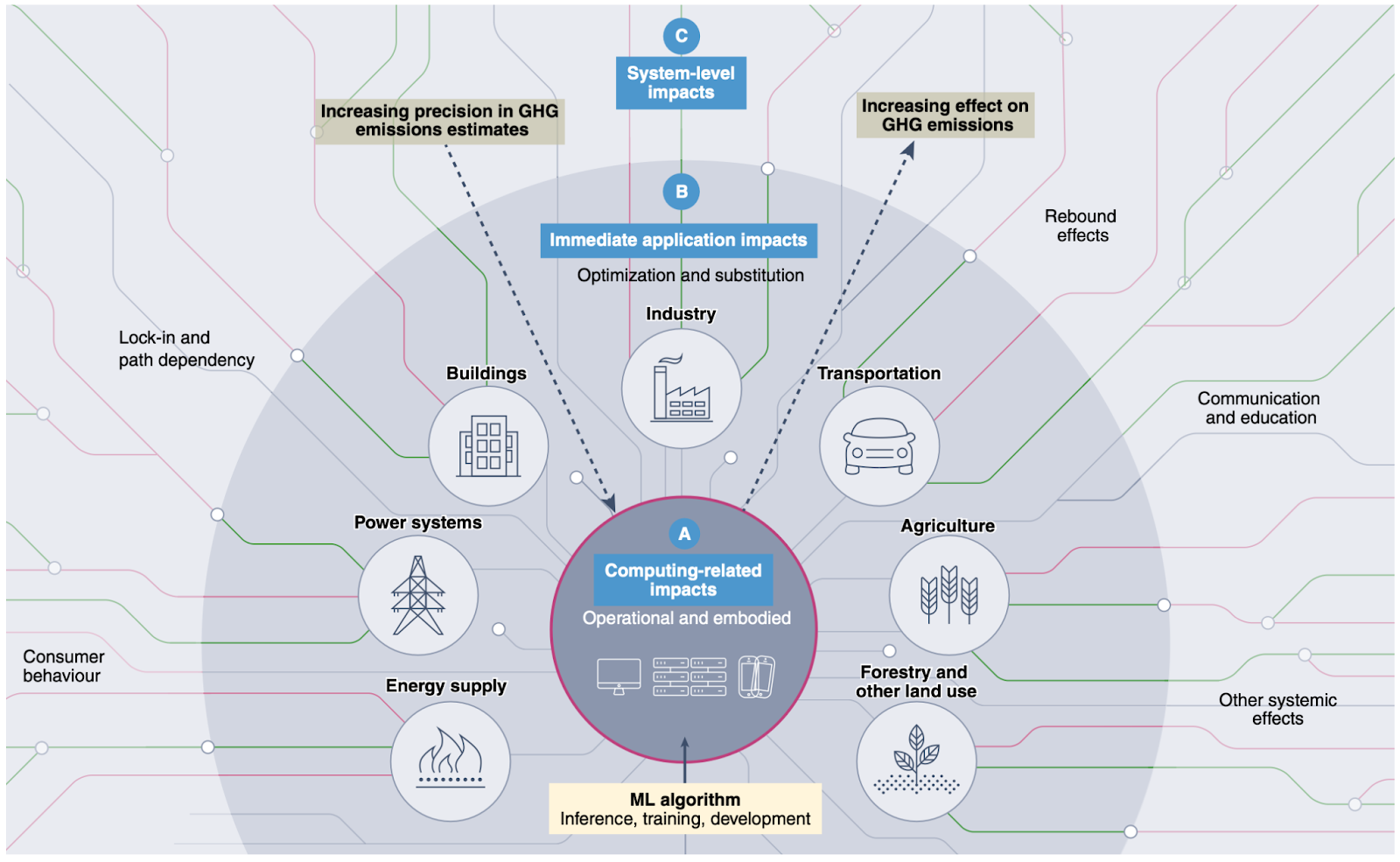

In this memo, we draw on research proposing a holistic evaluation framework for characterizing AI’s environmental impacts, which establishes three categories of impacts arising from AI: (1) Computing-related impacts; (2) Immediate application impacts; and (3) System-level impacts . Concerns around AI’s computing-related impacts, e.g. energy and water use due to AI data centers and hardware manufacturing, have become widely known with corresponding policy starting to be put into place. However, AI’s immediate application and system-level impacts, which arise from the specific use cases to which AI is applied, and the broader socio-economic shifts resulting from its use, remain poorly understood, despite their greater potential for societal benefit or harm.

To ensure that policymakers have full visibility into the full range of AI’s environmental impacts we recommend that the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) oversee creation of frameworks to measure the full range of AI’s impacts. Frameworks should rely on quantitative measurements of the computing and application related impacts of AI and qualitative data based on engagements with the stakeholders most affected by the construction of data centers. NIST should produce these frameworks based on convenings that include academic researchers, corporate governance personnel, developers, utility companies, vendors, and data center owners in addition to civil society organizations. Participatory workshops will yield new guidelines, tools, methods, protocols and best practices to facilitate the evolution of industry standards for the measurement of the social costs of AI’s energy infrastructures.

Challenge and Opportunity

Resource consumption associated with AI infrastructures is expanding quickly, and this has negative impacts, including asthma from air pollution associated with diesel backup generators, noise pollution, light pollution, excessive water and land use, and financial impacts to ratepayers. A lack of transparency regarding these outcomes and public participation to minimize these risks losing the public’s trust, which in turn will inhibit the beneficial uses of AI. While there is a huge amount of capital expenditure and a massive forecasted growth in power consumption, there remains a lack of transparency and scientific consensus around the measurement of AI’s environmental impacts with respect to data centers and their related negative externalities.

A holistic evaluation framework for assessing AI’s broader impacts requires empirical evidence, both qualitative and quantitative, to influence future policy decisions and establish more responsible, strategic technology development. Focusing narrowly on carbon emissions or energy consumption arising from AI’s computing related impacts is not sufficient. Measuring AI’s application and system-level impacts will help policymakers consider multiple data streams, including electricity transmission, water systems and land use in tandem with downstream economic and health impacts.

Regulatory and technical attempts so far to develop scientific consensus and international standards around the measurement of AI’s environmental impacts have focused on documenting AI’s computing-related impacts, such as energy use, water consumption, and carbon emissions required to build and use AI. Measuring and mitigating AI’s computing-related impacts is necessary, and has received attention from policymakers (e.g. the introduction of the AI Environmental Impacts Act of 2024 in the U.S., provisions for environmental impacts of general-purpose AI in the EU AI Act, and data center sustainability targets in the German Energy Efficiency Act). However, research by Kaack et al (2022) highlights that impacts extend beyond computing. AI’s application impacts, which arise from the specific use cases for which AI is deployed (e.g. AI’s enabled emissions, such as application of AI to oil and gas drilling have much greater potential scope for positive or negative impacts compared to AI’s computing impacts alone, depending on how AI is used in practice). Finally, AI’s system-level impacts, which include even broader, cascading social and economic impacts associated with AI energy infrastructures, such as increased pressure on local utility infrastructure leading to increased costs to ratepayers, or health impacts to local communities due to increased air pollution, have the greatest potential for positive or negative impacts, while being the most challenging to measure and predict. See Figure 1 for an overview.

from Kaack et al. (2022). Effectively understanding and shaping AI’s impacts will require going beyond impacts arising from computing alone, and requires consideration and measurement of impacts arising from AI’s uses (e.g. in optimizing power systems or agriculture) and how AI’s deployment throughout the economy leads to broader systemic shifts, such as changes in consumer behavior.

Effective policy recommendations require more standardized measurement practices, a point raised by the Government Accountability Office’s recent report on AI’s human and environmental effects, which explicitly calls for increasing corporate transparency and innovation around technical methods for improved data collection and reporting. But data should also include multi-stakeholder engagement to ensure there are more holistic evaluation frameworks that meet the needs of specific localities, including state and local government officials, businesses, utilities, and ratepayers. Furthermore, while states and municipalities are creating bills calling for more data transparency and responsibility, including in California, Indiana, Oregon, and Virginia, the lack of federal policy means that data center owners may move their operations to states that have fewer protections in place and similar levels of existing energy and data transmission infrastructure.

States are also grappling with the potential economic costs of data center expansion. Ohio’s Policy Matters found that tax breaks for data center owners are hurting tax revenue streams that should be used to fund public services. In Michigan, tax breaks for data centers are increasing the cost of water and power for the public while undermining the state’s climate goals. Some Georgia Republicans have stated that data center companies should “pay their way.” While there are arguments that data centers can provide useful infrastructure, connectivity, and even revenue for localities, a recent report shows that at least ten states each lost over $100 million a year in revenue to data centers because of tax breaks. The federal government can help create standards that allow stakeholders to balance the potential costs and benefits of data centers and related energy infrastructures. We now have an urgent need to increase transparency and accountability through multi-stakeholder engagement, maximizing economic benefits while reducing waste.

Despite the high economic and policy stakes, critical data needed to assess the full impacts—both costs and benefits—of AI and data center expansion remains fragmented, inconsistent, or entirely unavailable. For example, researchers have found that state-level subsidies for data center expansion may have negative impacts on state and local budgets, but this data has not been collected and analyzed across states because not all states publicly release data about data center subsidies. Other impacts, such as the use of agricultural land or public parks for transmission lines and data center siting, must be studied at a local and state level, and the various social repercussions require engagement with the communities who are likely to be affected. Similarly, estimates on the economic upsides of AI vary widely, e.g. the estimated increase in U.S. labor productivity due to AI adoption ranges from 0.9% to 15% due in large part to lack of relevant data on AI uses and their economic outcomes, which can be used to inform modeling assumptions.

Data centers are highly geographically clustered in the United States, more so than other industrial facilities such as steel plants, coal mines, factories, and power plants (Fig. 4.12, IEA World Energy Outlook 2024). This means that certain states and counties are experiencing disproportionate burdens associated with data center expansion. These burdens have led to calls for data center moratoriums or for the cessation of other energy development, including in states like Indiana. Improved measurement and transparency can help planners avoid overly burdensome concentrations of data center infrastructure, reducing local opposition.

With a rush to build new data center infrastructure, states and localities must also face another concern: overbuilding. For example, Microsoft recently put a hold on parts of its data center contract in Wisconsin and paused another in central Ohio, along with contracts in several other locations across the United States and internationally. These situations often stem from inaccurate demand forecasting, prompting utilities to undertake costly planning and infrastructure development that ultimately goes unused. With better measurement and transparency, policymakers will have more tools to prepare for future demands, avoiding the negative social and economic impacts of infrastructure projects that are started but never completed.

While there have been significant developments in measuring the direct, computing-related impacts of AI data centers, public participation is needed to fully capture many of their indirect impacts. Data centers can be constructed so they are more beneficial to communities while mitigating their negative impacts, e.g. by recycling data center heat, and they can also be constructed to be more flexible by not using grid power during peak times. However, this requires collaborative innovation and cross-sector translation, informed by relevant data.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Develop a database of AI uses and framework for reporting AI’s immediate applications in order to understand the drivers of environmental impacts.

The first step towards informed decision-making around AI’s social and environmental impacts is understanding what AI applications are actually driving data center resource consumption. This will allow specific deployments of AI systems to be linked upstream to compute-related impacts arising from their resource intensity, and downstream to impacts arising from their application, enabling estimation of immediate application impacts.

The AI company Anthropic demonstrated a proof-of-concept categorizing queries to their Claude language model under the O*NET database of occupations. However, O*NET was developed in order to categorize job types and tasks with respect to human workers, which does not exactly align with current and potential uses of AI. To address this, we recommend that NIST works with relevant collaborators such as the U.S. Department of Labor (responsible for developing and maintaining the O*NET database) to develop a database of AI uses and applications, similar to and building off of O*NET, along with guidelines and infrastructure for reporting data center resource consumption corresponding to those uses. This data could then be used to understand particular AI tasks that are key drivers of resource consumption.

Any entity deploying a public-facing AI model (that is, one that can produce outputs and/or receive inputs from outside its local network) should be able to easily document and report its use case(s) within the NIST framework. A centralized database will allow for collation of relevant data across multiple stakeholders including government entities, private firms, and nonprofit organizations.

Gathering data of this nature may require the reporting entity to perform analyses of sensitive user data, such as categorizing individual user queries to an AI model. However, data is to be reported in aggregate percentages with respect to use categories without attribution to or listing of individual users or queries. This type of analysis and data reporting is well within the scope of existing, commonplace data analysis practices. As with existing AI products that rely on such analyses, reporting entities are responsible for performing that analysis in a way that appropriately safeguards user privacy and data protection in accordance with existing regulations and norms.

Recommendation 2. NIST should create an independent consortium to develop a system-level evaluation framework for AI’s environmental impacts, while embedding robust public participation in every stage of the work.

Currently, the social costs of AI’s system-level impacts—the broader social and economic implications arising from AI’s development and deployment—are not being measured or reported in any systematic way. These impacts fall heaviest on the local communities that host the data centers powering AI: the financial burden on ratepayers who share utility infrastructure, the health effects of pollutants from backup generators, the water and land consumed by new facilities, and the wider economic costs or benefits of data-center siting. Without transparent metrics and genuine community input, policymakers cannot balance the benefits of AI innovation against its local and regional burdens. Building public trust through public participation is key when it comes to ensuring United States energy dominance and national security interests in AI innovation, themes emphasized in policy documents produced by the first and second Trump administrations.

To develop evaluation frameworks in a way that is both scientifically rigorous and broadly trusted, NIST should stand up an independent consortium via a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA). A CRADA allows NIST to collaborate rapidly with non-federal partners while remaining outside the scope of the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA), and has been used, for example, to convene the NIST AI Safety Institute Consortium. Membership will include academic researchers, utility companies and grid operators, data-center owners and vendors, state, local, Tribal, and territorial officials, technologists, civil-society organizations, and frontline community groups.

To ensure robust public engagement, the consortium should consult closely with FERC’s Office of Public Participation (OPP)—drawing on OPP’s expertise in plain-language outreach and community listening sessions—and with other federal entities that have deep experience in community engagement on energy and environmental issues. Drawing on these partners’ methods, the consortium will convene participatory workshops and listening sessions in regions with high data-center concentration—Northern Virginia, Silicon Valley, Eastern Oregon, and the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex—while also making use of online comment portals to gather nationwide feedback.

Guided by the insights from these engagements, the consortium will produce a comprehensive evaluation framework that captures metrics falling outside the scope of direct emissions alone. These system-level metrics could encompass (1) the number, type, and duration of jobs created; (2) the effects of tax subsidies on local economies and public services; (3) the placement of transmission lines and associated repercussions for housing, public parks, and agriculture; (4) the use of eminent domain for data-center construction; (5) water-use intensity and competing local demands; and (6) public-health impacts from air, light, and noise pollution. NIST will integrate these metrics into standardized benchmarks and guidance.

Consortium members will attend public meetings, engage directly with community organizations, deliver accessible presentations, and create plain-language explainers so that non-experts can meaningfully influence the framework’s design and application. The group will also develop new guidelines, tools, methods, protocols, and best practices to facilitate industry uptake and to evolve measurement standards as technology and infrastructure grow.

We estimate a cost of approximately $5 million over two years to complete the work outlined in recommendation 1 and 2, covering staff time, travel to at least twelve data-center or energy-infrastructure sites across the United States, participant honoraria, and research materials.

Recommendation 3. Mandate regular measurement and reporting on relevant metrics by data center operators.

Voluntary reporting is the status quo, via e.g. corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reports, but voluntary reporting has so far been insufficient for gathering necessary data. For example, while the technology firm OpenAI, best known for their highly popular ChatGPT generative AI model, holds a significant share of the search market and likely corresponding share of environmental and social impacts arising from the data centers powering their products, OpenAI chooses not to publish ESG reports or data in any other format regarding their energy consumption or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In order to collect sufficient data at the appropriate level of detail, reporting must be mandated at the local, state, or federal level. At the state level, California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB -253, SB-219) requires that large companies operating within the state report their GHG emissions in accordance with the GHG Protocol, administered by the California Air Resources Board (CARB).

At the federal level, the EU’s Corporate Sustainable Reporting Directive (CSRD), which requires firms operating within the EU to report a wide variety of data related to environmental sustainability and social governance, could serve as a model for regulating companies operating within the U.S. The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) GHG Reporting Program already requires emissions reporting by operators and suppliers associated with large GHG emissions sources, and the Energy Information Administration (EIA) collects detailed data on electricity generation and fuel consumption through forms 860 and 923. With respect to data centers specifically, the Department of Energy (DOE) could require that developers who are granted rights to build AI data center infrastructure on public lands perform the relevant measurement and reporting, and more broadly reporting could be a requirement to qualify for any local, state or federal funding or assistance provided to support buildout of U.S. AI infrastructure.

Recommendation 4. Incorporate measurements of social cost into AI energy and infrastructure forecasting and planning.

There is a huge range in estimates of future data center energy use, largely driven by uncertainty around the nature of demands from AI. This uncertainty stems in part from a lack of historical and current data on which AI use cases are most energy intensive and how those workloads are evolving over time. It also remains unclear the extent to which challenges in bringing new resources online, such as hardware production limits or bottlenecks in permitting, will influence growth rates. These uncertainties are even more significant when it comes to the holistic impacts (i.e. those beyond direct energy consumption) described above, making it challenging to balance costs and benefits when planning future demands from AI.

To address these issues, accurate forecasting of demand for energy, water, and other limited resources must incorporate data gathered through holistic measurement frameworks described above. Further, the forecasting of broader system-level impacts must be incorporated into decision-making around investment in AI infrastructure. Forecasting needs to go beyond just energy use. Models should include predicting energy and related infrastructure needs for transmission, the social cost of carbon in terms of pollution, the effects to ratepayers, and the energy demands from chip production.

We recommend that agencies already responsible for energy-demand forecasting—such as the Energy Information Administration at the Department of Energy—integrate, in line with the NIST frameworks developed above, data on the AI workloads driving data-center electricity use into their forecasting models. Agencies specializing in social impacts, such as the Department of Health and Human Services in the case of health impacts, should model social impacts and communicate those to EIA and DOE for planning purposes. In parallel, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) should update its new rule on long-term regional transmission planning, to explicitly include consideration of the social costs corresponding to energy supply, demand and infrastructure retirement/buildout across different scenarios.

Recommendation 5. Transparently use federal, state, and local incentive programs to reward data-center projects that deliver concrete community benefits.

Incentive programs should attach holistic estimates of the costs and benefits collected under the frameworks above, and not purely based on promises. When considering using incentive programs, policymakers should ask questions such as: How many jobs are created by data centers and for how long do those jobs exist, and do they create jobs for local residents? What tax revenue for municipalities or states is created by data centers versus what subsidies are data center owners receiving? What are the social impacts of using agricultural land or public parks for data center construction or transmission lines? What are the impacts to air quality and other public health issues? Do data centers deliver benefits like load flexibility and sharing of waste heat?

Grid operators (Regional Transmission Organizations [RTOs] and Independent System Operators [ISOs]) can leverage interconnection queues to incentivize data center operators to justify that they have sufficiently considered the impacts to local communities when proposing a new site. FERC recently approved reforms to processing the interconnect request queue, allowing RTOs to implement a “first-ready first-served” approach rather than a first-come first-served approach, wherein proposed projects can be fast-tracked based on their readiness. A similar approach could be used by RTOs to fast-track proposals that include a clear plan for how they will benefit local communities (e.g. through load flexibility, heat reuse, and clean energy commitments), grounded in careful impact assessment.