DF-21C Missile Deploys to Central China

|

| China’s new DF-21C missile launcher shows itself in Western China. Image: GoogleEarth |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest Pentagon report on Chinese military forces recently triggered sensational headlines in the Indian news media that China had deployed new nuclear missiles close to the Indian border.

The news reports got it wrong, but new commercial satellite images reveal that launch units for the new DF-21C missile have deployed to central-western China.

New DF-21C Launch Units

Analysis of commercial satellite imagery reveals that launch units for the road-mobile DF-21C medium-range ballistic missile now deploy several hundred kilometers west of Delingha in the western part of central China.

| Location of DF-21C Launch Units |

|

| For larger versions of the two middle satellite images, click here and here. Images: GoogleEarth and chinamil.com.cn |

In one image, taken by the GeoEye-1 satellite on June 14, 2010, two launch units are visible in approximately 230 km west of Delingha. The units are dug into the dry desert slopes near Mount Chilian along national road G215. Missile launchers, barracks, maintenance and service units are concealed under large dark camouflage, which stands out clearly in the brown desert soil.

The eastern launch unit (38° 6’37.75″N, 94°59’2.19″E) includes a central area with red barracks clearly visible below the camouflage, which probably also covers logistic units such as communications vehicles, fuel trucks, and personnel carriers. An 88×17 meter garage of brown camouflaged probably covers the launcher service area, with five 15-meter garages nearby probably housing the TELs. Approximately 130 meters north of the central area, brown camouflage and dirt barriers possibly house the unit’s remote fuel area. Two launch pads are visible, one only 180 meters from the main section, the other on the access road leading to national road G215.

The western launch unit (38° 9’32.82″N, 94°55’37.02″E) is located approximately 7 km further west about 2.4 km to the north of national road G215. The unit consists of four sections: personnel barracks (almost 100 with more possibly under camouflage); a logistic vehicles area; a launcher service area with a 90×33 meter camouflage and four garages; and what is possibly a remote fuel storage area. A launch pad is located along the access road close to G215.

The satellite image shows what appears to be a DF-21C entering or leaving the camouflaged launcher service area. The characteristic nose cone of the missile canister embedded into the rear of the driver cockpit is clearly visible, with the rest of launcher probably covered by a tarp.

This is, to my knowledge, the first time that the DF-21C has been identified in a deployment area. In 2007, I used commercial satellite images to describe the first visual signs of the transition from DF-4 to DF-21 at Delingha. A second article in 2008 described the extensive system of launch pads that extends west from Delingha along national road G215 past Da Qaidam.

There are five launch pads within five miles of the two launch units, with dozens other pads along and north of G215 in both directions.

More Invulnerable but with Limits

China’s ongoing modernization from old liquid-fuel missiles to new solid-fuel missiles is getting a lot of attention. The new systems are more mobile and thus less vulnerable to attack. Yet the satellite images also give hints about limitations.

First, the launch units are large with a considerable footprint that covers an area of approximately 300×300 meters. They are manpower-intensive requiring large numbers of support equipment. This makes them harder to move quickly and relatively easy to detect by satellite images.

| DF-21C Launch Unit on the Move |

|

| The DF-21C medium-range ballistic missile may be more mobile and harder to target than older missiles, but it still relies on a large support unit that can be detected. Image: CCTV-7 |

.

Individual launchers of course would be dispersed into the landscape in case of war. But although the road-mobile launcher has some off-road capability, it requires solid ground when launching to prevent damage from debris kicked up by the rocket engine. As a result, launchers would have to stay on roads or use the pre-made launch pads that stand out clearly in high-resolution satellite images. Moreover, a launcher would not simply drive off and launch by itself, but need to be followed by support vehicles for targeting, repair, and communication.

Indian News Media (Mis)reporting

The deployment of DF-21 missiles caused constipation in Indian last month after the 2010 Pentagon report of Chinese military forces stated that China is replacing DF-4 missiles with DF-21 missiles to improve regional deterrence. The statement was contained in a section dealing with Chinese-Indian affairs and was picked up by the Press Trust of India, which mistakenly reported that the Pentagon report stated that, “China has moved advanced longer range CSS-5 [DF-21] missiles close to the border with India.” The Times of India even wrote the missiles were being deployed “on border” with India.

| India News Media Makes a Bad Situation Worse |

|

| The India news media significantly misreported what the Pentagon report said about the Chinese DF-21 deployment. Not the finest hour of Indian journalism. |

.

Not surprisingly, the misreporting triggered dramatic news articles in India, including rumors that the Indian Strategic Forces Command was considering or had already moved nuclear-capable missile units north toward the Chinese border in retaliation.

The Pentagon report, however, said nothing about moving DF-21 missiles close to or “on” the Indian border. Here is the actual statement: “To improve regional deterrence, the PLA has replaced older liquid-fueled, nuclear-capable CSS-3 intermediate-range ballistic missiles with more advanced and survivable solid-fueled CSS-5 MRBM….” The statement echoes a statement in the 2009 report: “The [People’s Liberation Army] has replaced older liquid-fueled nuclear-capable CSS-3 [DF-4 medium-range ballistic missiles] MRBMs with more advanced solid-fueled CSS-5 MRBMs in Western China.”

The sentence appears to describe the apparent near-completion of China’s replacement of DF-4 missiles with DF-21 missiles, probably at two army base areas in Hunan and Qinghai provinces, a transition that has been underway for two decades. The two deployment areas are each more than 1,500 kilometers from the Indian border.

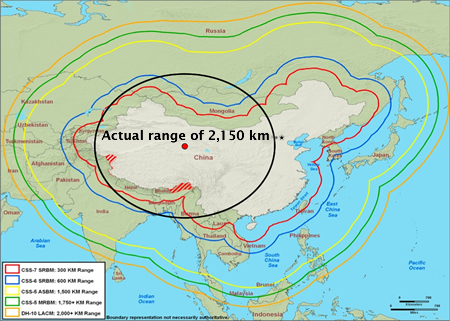

Range Confusion

The unclassified ranges of Chinese DF-21 versions published by the U.S. intelligence community are 1,770+ km (1,100+ miles) for the two nuclear versions (DF-21, CSS-5 Mod 1; and DF-21A, CSS-5 Mod 2). The DF-21A appears to have an extended range of 2,150 km. The dual-capable “conventional” DF-21C has a maximum range of 1,770 km, and the yet-to-be-deployed DF-21D anti-ship missile has a shorter range of 1,450+ km. Private publications frequently credit the DF-21D with a much longer range (CSBA: 2,150 km; sinodefence.com and Wikipedia: 3,000 km).

DOD maps are misleading because they depict missile ranges measured from the Chinese border, as if the launchers were deployed there rather than at their actual deployment areas far back from the border. The 2008 report, for example, includes a map essentially showing China’s border extended outward in different colors for each missile range. The result is a DF-21 range of about 3,000 km if measured from the actual deployment areas.

| DF-21 Range According to 2008 Pentagon Report |

|

| The 2008 Pentagon report on China’s military forces misrepresents missile ranges. |

.

The 2010 report is even worse because it shows the ranges without the border contours as circles but measured from the most extreme border position. The result is a map that is even more misleading, suggesting a DF-21 range of as much as 3,500 km from actual deployment areas. The actual maximum range is 2,150 km for DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2), and 1,770 km for the DF-21C.

| DF-21 Range According to 2010 Pentagon Report |

|

| The 2010 Pentagon report on Chinese military issues greatly exaggerates the reach of the DF-21 by drawing a ring around China that doesn’t reflect actual deployment areas. |

.

Although a DF-21 launcher could theoretically drive all the way up to the border to launch, the reality is that DF-21 bases and roaming areas are located far back from the border to protect the fragile launchers from air attack. DOD maps should reflect that reality.

Additional Resources: earlier China blogs; Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

China’s Bulava?

|

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Similar to Russia’s troubled Bulava sea-launched ballistic missile, the Pentagon’s latest report on China’s military power reveals that Chinese efforts to develop a new sea-based nuclear missile have run into problems.

Other nuclear force developments described in the Pentagon’s delayed annual report on China’s military power, now renamed Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, include a slow deployment of new land-based mobile missiles and nuclear command and control challenges.

Naval Nuclear Programs

While the first boat of a small class of new Jin-class (Type 094) sea-launched ballistic missile submarines “appears ready” and up to four more may be building, development of the long-range ballistic missile Julang-2 for the class is said to have “encountered difficulty.”

The report reveals that the new missile has been “failing several of what should have been the final round of flight tests.”

| Julang-2 “Dry” Launch |

|

| The Pentagon says China’s new sea-launched ballistic missile has failed several tests. |

.

The latest setback continues the problems that have characterized China’s naval nuclear program over the years. The first SSBN program (Type 092) only produced one boat, the Xia, which has never sailed on a deterrent patrol. Even following a recent lengthy submarine overhaul, the Pentagon describes the operational status of the Xia’s Julang-1 missile system as “questionable.”

The nuclear-powered attack submarine program also seems challenged, with only two Shang-class (Type 093) boats operational – the same as last year – and four old Han-class (Type 091) boats still in service. Instead, the focus of the nuclear attack submarine program appears to have shifted to building a new class, the Type 095. The Pentagon report projects that “up to five” Type 095s may be added “in the coming years.”

Land-Based Nuclear Missiles

Introduction of new land-based mobile ballistic missiles continues, but at a slow pace. The DF-31 program appears stagnant at “<10” missiles, the same as reported last year. The number of intercontinental DF-31As has only increased by a couple of missiles, from “<10” last year to “10-15” in this year’s report.

| DF-31A Parading in Beijing |

|

| Deployment of the DF-31 and DF-31A has been slow, new Pentagon report shows. |

.

Probably as a possible result of the slow deployment of the new DF-31, the number of old liquid-fueled DF-3A and DF-4 missiles remain the same as last year.

Despite a strong display at the military parade in Beijing last year, the number of DF-21 launchers has not increased compared with last year. The number of missiles is a little higher, 85-90 missiles versus 60-80, probably reflecting addition of conventional DF-21C versions.

The report continues previous years’ predictions that a new road-mobile ICBM may be under development, possibly a reference to the elusive DF-41 or another system. The new missile is described as “possibly capable of carrying a multiple independently targeted re-entry vehicle (MIRV).”

Previous reports have reported development of MIRV technology for many years, but always concluded that MIRV technology for mobile missiles would be too difficult and expensive. The reference to a road-mobile ICBM MIRV capability is new, although it comes with a lot of caveats: “may be under development,” and “possibly capable of carrying” MIRV.

A MIRV system would, if deployed, represent a significant change in Chinese nuclear employment strategy. Russia and the United States deployed MIRVed systems to improve targeting against military targets. A secondary reason – for Britain it was probably the primary reason – was to overwhelm missile defenses.

Rather than increased targeting, the Chinese motivation for pursuing MIRV probably is the emergence of increasingly advanced U.S. ballistic missile systems. Phase 4 of the Obama administration’s Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA) includes an anti-ballistic missile defense capability against ICBMs from around 2020. This may push China further toward MIRV.

| Julang-1 Loading |

|

| Could loading of nuclear missiles in a crisis affect crisis stability? |

Nuclear Command and Control

As were the case with the 2009 report, the 2010 report underscores the command and control issues facing Chinese leaders. “The introduction of more mobile systems will create new command and control challenges for China’s leadership, which now confronts a different set of variables related to deployment and release authorities.”

One of these is the emerging SSBN force, an almost entirely new form of nuclear deployment in Chinese posturing. The report states that “the PLA has only a limited capacity to communicate with submarines at sea, and the PLA Navy has no experience in managing a SSBN fleet that performs strategic patrols with live nuclear warheads mated to missiles.”

Chinese SSBNs have never performed a strategic deterrent patrol (none were conducted in 2009), and if current Chinese doctrine is any indication it is doubtful that the SSBNs will deploy with “live nuclear warheads mated to missiles” in peacetime. But the absence of operational experience and the limited communication capability raises serious questions about how inadequate proficiency and launch control procedures might create problems in a crisis.

The report raises similar issues with the emergency of the new generation of land-based mobile missiles. Although China has operated medium-range mobile missiles for decades, the delegation of launch authority in a crisis to units with quicker-launch solid-fuel long-range missiles raises questions about use control, crisis stability, and misunderstandings.

| DF-31A on Launch Pad |

|

| How will quicker-firing long-range missiles such as the DF-31A affect command and control and delegation of launch authority? |

.

And there “is little evidence,” the Pentagon concludes, “that China’s military and civilian leaders have fully thought through the global and systemic effects that would be associated with the employment of these strategic capabilities.”

Despite these issues and speculations in previous annual Pentagon reports and the public about possible changes to Chinese nuclear doctrine, particularly conditions to its no-first-use policy, the 2010 report concludes that, “there has been no indication that national leaders are willing to attach such nuances and caveats to China’s ‘no first use’ doctrine.”

See also: previous blogs about China

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

United States Discloses Size of Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

|

| The Obama administration has declassified the history and size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, a long-held national secret. Click image to get the fact sheet. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

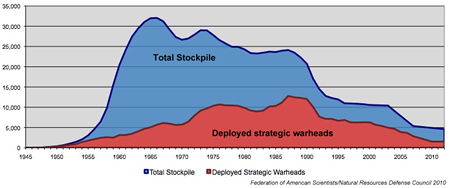

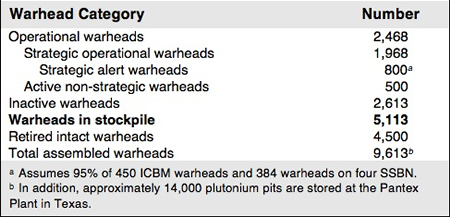

The Obama administration has formally disclosed the size of the Defense Department’s stockpile of nuclear weapons: 5,113 warheads as of September 30, 2009.

For a national secret, we’re pleased that the stockpile number is only 87 warheads off the estimate we made in February 2009. By now, the stockpile is probably down to just above 5,000 warheads.

The disclosure is a monumental step toward greater nuclear transparency that breaks with outdated Cold War nuclear secrecy and will put significant pressure on other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate.

The stockpile disclosure, along with the rapid reduction of operational deployed warheads disclosed yesterday, the Obama administration is significantly strengthening the U.S. position at the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

Progress toward deep nuclear cuts and eventual nuclear disarmament would have been very difficult without disclosing the inventory of nuclear weapons.

FAS and others have long advocated disclosure and argued that keeping the size of the nuclear arsenal secret serves no real national security purpose in the post-Cold War era. Now that the size of the nuclear stockpile is no longer a secret, that dismantlement numbers are no longer secret, and the number of deployed strategic warheads is no longer a secret, the United States should also disclose the total number of strategic and non-strategic weapons in the stockpile.

Stockpile History and Forecast

When the Bush administration took office in 2001, the stockpile included 10,526 warheads. In June 2004, the NNSA announced a decision to cut the 2001 stockpile “nearly in half” by 2012. That goal was achieved five years early in December 2007, at which point the White House announced an additional cut of 15 percent by 2012. Once these reductions are completed, the stockpile will include approximately 4,600 warheads, a force level last seen in 1956.

.

The Obama administration has not yet announced a decision to further reduce the nuclear stockpile, but there are several hints in the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) that it intends to reduce the stockpile further. The NPR states that the United States will be “significantly reducing the size of the technical hedge overall,” a reference to the thousands of non-deployed but intact warheads kept in storage for potential upload back unto missiles and bombers in case of Russia or China building up and to replace warheads that develop technical problems.

The NPR also states that the number of warheads awaiting dismantlement “will increase as weapons are removed from the stockpile under New START.” Since the New START does not require removing weapons from the stockpile – only from strategic delivery vehicles – this is also a reference to further stockpile reductions. One senior official told me that some of these reductions would be made soon.

But the “major reductions in the nuclear stockpile” promised by the NPR appear to be conditioned on “implementation of the Stockpile Stewardship Program and the nuclear infrastructure investments….” If Congress approves these investments, some “hedge” warheads can “be retired along with other stockpile reductions planned over the next decade.”

| Estimated U.S. Nuclear Weapons Inventories, 2010 |

|

| The nuclear stockpile is only a portion of the total U.S. inventory of nuclear weapons. We estimate the total number of assembled warheads is close to 9,600, probably a little less given ongoing dismantlement of retired warheads. |

.

Stockpile Warhead Categories

The stockpile contains many subcategories of warheads. There are two overall categories: active and inactive. The active category includes two subcategories: deployed warheads on missiles and bomber bases and nondeployed warheads in the “Responsive Force” for uploading in case of Russia or China building up or technical failure of deployed warheads. The inactive category includes warheads without limited-life components (such as tritium) in long-term storage.

But since the stockpile is always in a flux with warheads being moved between platforms and maintenance, each of these subcategories have numerous other categories that relate to the readiness of the warheads. According to information obtained from the government, there are four readiness state (RS) categories related to warhead functions:

RS-A: Warheads that may be used for possible wartime employment.

RS-B: Warheads intended to be used for logistical purposes (e.g., LLC exchange (LLCE), repairs, surveillance, transportation, etc.).

RS-C: Warheads intended to be used for QUART replacement.

RS-D: Warheads intended to be used for reliability replacement.

There are also five readiness state categories that relate to the warhead location an maintenance requirements:

RS-1: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily on launchers or at an operational base.

RS-2: Active stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at either an operational base or depot.

RS-3: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, require refurbishment, and require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-4: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located primarily at a depot, have the LLCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, but do require reliability and safety assessments.

RS-5: Inactive stockpile warheads intended to be located at a depot, have LCCs removed as soon as logistically practical, do NOT require refurbishment, do NOT require reliability assessments, but do require safety assessments.

Other Countries

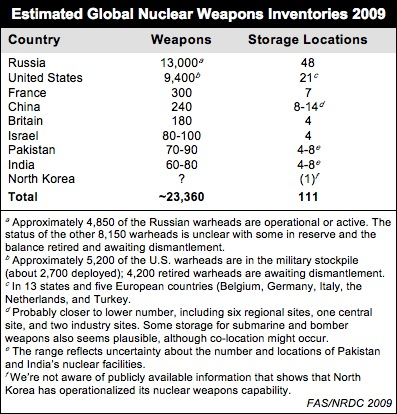

The disclosure puts pressure of the other nuclear weapon states to reciprocate. Nuclear weapon states that do not disclose the size of their nuclear arsenals will now be seen as secretive and obstructing nuclear transparency and progress towards deep cuts and eventually disarmament. Some nuclear countries have given ballpark numbers:

The Chinese Foreign Ministry declared in a fact sheet in 2004 that, “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China. . . possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.” That suggested fewer than 200 operationally available warheads, as declared by Britain in 1998. (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on China.)

Britain further declared in 2007 that it would “reduce the maximum number of operationally available warheads from fewer than 200 to fewer than 160” by 2007. This suggests that a limited inventory of non-operationally available warheads exists.

France declared in 2008 that its “arsenal will include fewer than 300 nuclear warheads” following a reduction of the bombers. French president Nicolas Sarkozy claimed France was “completely transparent because it has no other weapons beside those in its operational arsenal.” Nonetheless, a small number of spares or warheads undergoing surveillance probably exist in additional to those in the “operational arsenal.” (See also the latest Nuclear Notebook on France.)

Russia has not, to my knowledge, disclosed anything about the size of its stockpile. (See latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia.)

Dismantlements

The Pentagon also released warhead dismantlement numbers back to 1995. I’ll blog later on what that means.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Second Chinese Naval Demagnetization Facility Spotted

|

| Click image for large version |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

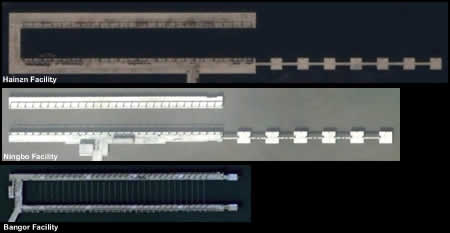

The Chinese navy has constructed what appears to be a demagnetization facility near an East Sea Fleet submarine base.

The facility is the second spotted at Chinese naval bases since 2008.

Chinese Naval Demagnetization Facilities

The new demagnetization facility is located less than 10 km from the Kilo submarine base at Maocao Nong approximately 40 km southeast of Ningbo in the Zhejiang province.

Seven Kilo-class submarines were visible at the base on January 15, 2009, nearly a third of the roughly 19 diesel-electric attack submarines that are deployed with the East Sea Fleet.

.

The East Sea Fleet facility was built between August 2007 and March 2008.

The East Sea Fleet facility is the second known Chinese demagnetization facility. In April 2008, I identified the first such facility at the South Sea Fleet base near Yulin on Hainan Island.

The South Sea Fleet facility was constructed sometime between January 2006 and February 2008.

.

The two demagnetization facilities are similar but with differences. The South Sea Fleet facility is built in a c-shape, similar to the U.S. design. The East Sea Fleet facility, which is located in a river, consists of two parallel piers, perhaps to accommodate strong currents.

The Purpose of Demagnetization

Demagnetization is conducted before deployment to remove residual magnetic fields in the metal of a vessel to make it harder to detect by other submarines and surface ships. It reduces the ship’s vulnerability to mines that are triggered by magnetic signals from metal hulls. Demagnetization apparently also can improve the speed of the vessel.

| Demagnetization of Ballistic Missile Submarine |

|

| A U.S. SSBN is prepared for demagnetization at the Kitsap Naval Submarine Base near Bangor, Washington. The U.S. Navy has such facilities on both coasts. |

.

Both submarines and surface ships are demagnetized at regular intervals.

Nuclear-powered submarines including SSBNs are based at the North Sea and South Sea Fleets, but not at the East Sea Fleet. I suspect that we’ll see construction of a North Sea Fleet demagnetization facility soon.

Some Implications

Occasional Chinese naval force operations get prominent attention in western news media, such as the recent transit between Okinawa and Miyako Island of eight destroyers and two submarines. Routine operations by U.S. forces, on the other hand, are rarely described except when they involve large exercises or when incidents occasionally expose secret options such as the Impeccable incident in 2009.

Mining of harbors and costal areas would likely be an important mission for both U.S. and Chinese attack submarines and anti-submarine warfare forces in a hypothetical military conflict between China and the United States. Chinese naval forces have, despite ongoing modernization, significant technological and operational deficiencies.

So why has China not constructed naval demagnetization facilities earlier? After all, other naval powers have done so for decades after German engineers during World War II invented the magnetic mine. According to one report, China appears to have used degaussing vessels rather than fixed facilities.

Perhaps construction now reflects acquisition of new technology, a decision that fixed facilities are more efficient than degaussing vessels, or that modifications to China’s naval strategy make demagnetization more important.

Whatever the motivation, the construction of demagnetization facilities at China’s fleets are clear tell-signs of the cat-and-mouse game that is in full swing in the region between the naval forces of China and the United States and its Asian allies.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Jin SSBN Flashes its Tubes

|

| One of China’s two Jin-class SSBNs with two open missile tubes. Click for larger image. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

One of China’s two new Jin-class SSBNs was photographed with two of its 12 missile tubes open when it visited Xiaopingdao Naval Base in March 2009.

The Jins are being readied to carry the JL-2, a single-warhead regional sea-launched ballistic missile that was most recently test-launched in May 2008. The class may become operational soon and replace the old Xia from 1982.

Xiaopingdao Naval Base, which is where I identified the Jin-class for the first time in 2007, serves as an outfitting and testing facility for new submarines and used to be the homeport of the single Golf-class diesel submarine China used for many years as a test launch platform for its first ballistic missile.

Two or three Jin-class SSBN have been under construction, and it remains to be seen if China will build up to five as projected by U.S. intelligence. China’s nuclear submarines appear to be the noisiest nuclear submarines in the world and will probably be highly vulnerable at sea.

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence described in August 2009 that two of China’s SSBNs (probably one Jin and the Xia) were based at the Northern Fleet Base in Jianggezhuang, and the third boat (probably the second Jin) at the Southern Fleet Base on Hainan Island. I identified the Jin at Hainan in February 2008.

The Obama administration’s first version of The Military Power of the People’s Republic of China is expected within the next month or two.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Estimated Nuclear Weapons Locations 2009

Some 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at 111 locations around the world

.The world’s approximately 23,300 nuclear weapons are stored at an estimated 111 locations in 14 countries, according to an overview produced by FAS and NRDC.

Nearly half of the weapons are operationally deployed with delivery systems capable of launching on short notice.

The overview is published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and includes the July 2009 START memorandum of understanding data. A previous version was included in the annual report from the International Panel of Fissile Materials published last month.

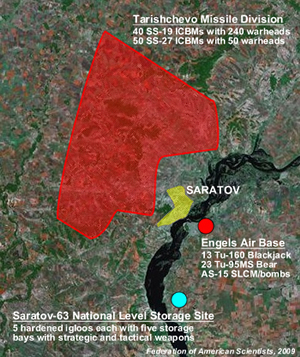

More than 1,000 nuclear weapons surround Saratov.

Russia has an estimated 48 permanent nuclear weapon storage sites, of which more than half are on bases for operational forces. There are approximately 19 storage sites, of which about half are national-level storage facilities. In addition, a significant number of temporary storage sites occasionally store nuclear weapons in transit between facilities.

This is a significant consolidation from the estimated 90 Russian sites ten years ago, and more than 500 sites before 1991.

Many of the Russian sites are in close proximity to each other and large populated areas. One example is the Saratov area where the city is surrounded by a missile division, a strategic bomber base, and a national-level storage site with probably well over 1,000 nuclear warheads combined (Figure 2).

The United States stores its nuclear weapons at 21 locations in 13 states and five European countries. This is a consolidation from the estimated 24 sites ten year ago, 50 at the end of the Cold War, and 164 in 1985 (see Figure 3).

Approximately 50 B61 nuclear bombs inside an igloo at what might be Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada. Seventy-five igloos at Nellis store “one of the largest stockpile in the free world,” according to the U.S. Air Force, one of four central storage sites in the United States.

Europe has about the same number of nuclear weapon storage locations as the Continental United States, with weapons scattered across seven countries. This includes seven sites in France and four in Britain. Five non-nuclear NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) still host U.S. nuclear weapons first deployed there during the Cold War.

We estimate that China has 8-14 facilities associated with nuclear weapons, most likely closer to the lower number, near bases with units that operate nuclear missiles or aircraft. None of the weapons are believed to be fully operational but stored separate from delivery vehicles at sites controlled by the Central Military Commission.

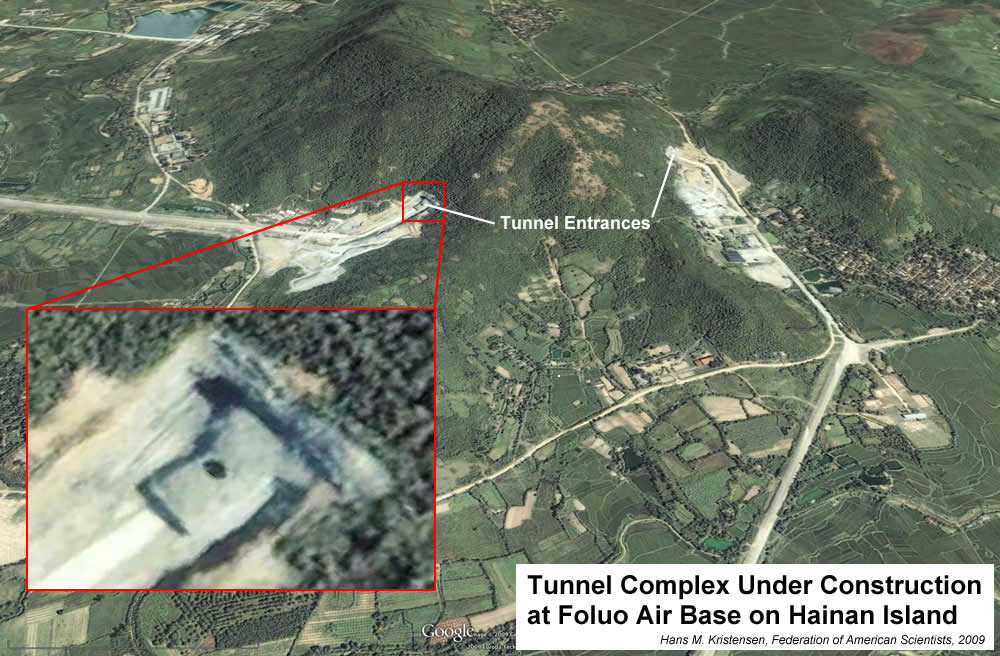

Where does China store nuclear warheads for its ballistic missile submarines? The naval base near Julin on Hainan Island has extensive underground facilities. An alternative to the base itself could potentially be a facility elsewhere on the island, such as Foluo Air Base where construction of an underground facility began five years before the first SSBN arrived at Hainan. Or are the weapons stored on the mainland? Click image to enlarge.

Israel probably has about four nuclear sites, whereas the nuclear storage facilities in India and Pakistan are – despite many rumors – largely undetermined. All three countries are thought to store warheads separate from delivery vehicles.

Despite two nuclear tests and many rumors, we are unaware of publicly available evidence that North Korea has operationalized its nuclear weapons capability.

Warhead concentrations vary greatly from country to country. With 13,000 warheads at 48 sites, Russian stores an average of 270 warheads at each location. The U.S. concentration is much higher with an average of 450 warheads at each location. These are averages, however, and in reality the distribution is thought to be much more uneven with some sites only storing tens of warheads.

Finally, a word of caution is in order: estimates such as these obviously come with a great deal of uncertainty, as we don’t have access to classified intelligence estimates. Based on publicly available information and our own assumptions we have nonetheless produced a best estimate that we hope will assist the public debate. Comments and suggestions are encouraged so we can adjust the overview in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

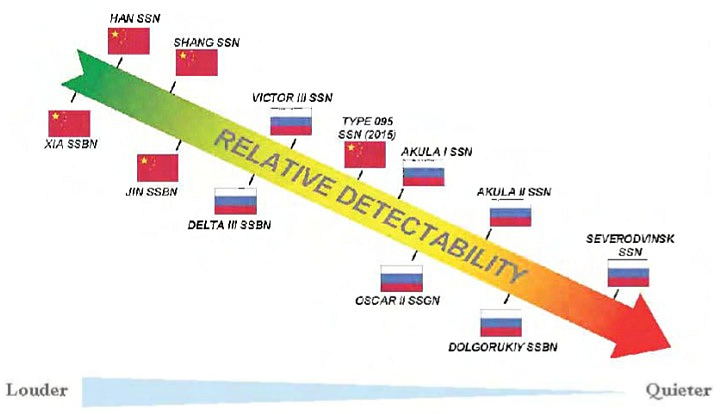

China’s Noisy Nuclear Submarines

|

| China’s newest nuclear submarines are noisier than 1970s-era Soviet nuclear submarines. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

China’s new Jin-class ballistic missile submarine is noisier than the Russian Delta III-class submarines built more than 30 years ago, according to a report produced by the U.S. Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

The report The People’s Liberation Army Navy: A Modern Navy With Chinese Characteristics, which was first posted on the FAS Secrecy News Blog and has since been removed from the ONI web site [but now back here; thanks Bruce], is to my knowledge the first official description made public of Chinese and Russian modern nuclear submarine noise levels.

Force Level

The report shows that China now has two Jin SSBNs, one of which is based at Hainan Island with the South Sea Fleet, along with two Type 093 Shang-class nuclear-powered attack submarines (SSN). The Jin was first described at Hainan in February 2008 and the two Shangs in September 2008. The second Jin SSBN is based at Jianggezhuang with the North Sea Fleet alongside the old Xia-class SSBN and four Han-class SSNs.

The report confirms the existence of the Type 095, a third-generation SSN intended to follow the Type 093 Shang-class. Five Type 095s are expected from around 2015. The Type-95 is estimated to be noisier than the Russian Akula I SSN built 20 years ago.

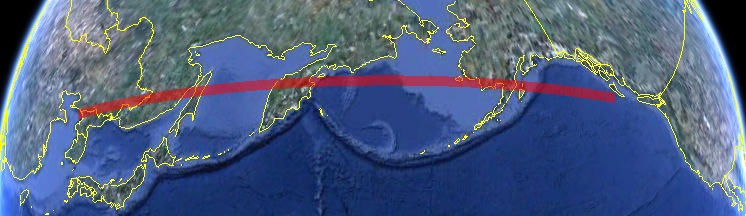

Missile Range

The ONI report states that the JL-2 sea-launched ballistic missile on the Jin SSBNs has a range of ~4,000 nautical miles (~7,400 km) “is capable of reaching the continental United States from Chinese littorals.” Not quite, unless Chinese littorals extend well into the Sea of Japan. Since the continental United States does not include Alaska and Hawaii, a warhead from a 7,400-km range JL-2 would fall into the sea about 800 km from Seattle. A JL-2 carrying penetration aids in addition to a warhead would presumably have a shorter range.

|

Julang-2 SLBM Range According to ONI |

|

| Although the ONI report states that the Julang-2 can target the Continental United States, the range estimate it provides is insufficient to reach the lower 48 states or Hawaii. |

.

Alaska would be in range if the JL-2 is launched from the very northern parts of Chinese waters, but Hawaii is out of range unless the missile is launched from a position close to South Korea or Japan. The U.S. Defense Department’s 2009 report to Congress on the Military Power of the People’s Republic of China also shows the range of the JL-2 to be insufficient to target the Continental United States or Hawaii from Chinese waters. The JL-2 instead appears to be a regional weapon with potential mission against Russia and India and U.S. bases in Guam and Japan.

Patrol Levels

The report also states that Chinese submarine patrols have “more than tripled” over the past few years, when compared to the historical levels of the last two decades.

That sounds like a lot, but given that the entire Chinese submarine fleet in those two decades in average conducted fewer than three patrols per year combined, a trippling doesn’t amout to a whole lot for a submarine fleet of 63 submarines. According to data obtained from ONI under FOIA, the patrol number in 2008 was 12.

Since only the most capable of the Chinese attack submarines presumably conduct these patrols away from Chinese waters – and since China has yet to send one of its ballistic missile submarines on patrol – that could mean one or two patrols per year per submarine.

Implications

The ONI report concludes that the Jin SSBN with the JL-2 SLBM gives the PLA Navy its first credible second-strike nuclear capability. The authors must mean in principle, because in a war such noisy submarines would presumably be highly vulnerabe to U.S. or Japanese anti-submarine warfare forces. (The noise level of China’s most modern diesel-electric submarines is another matter; ONI says some are comparable to Russian diesel-electric submarines).

That does raise an interesting question about the Chinese SSBN program: if Chinese leaders are so concerned about the vulnerability of their nuclear deterrent, why base a significant portion of it on a few noisy platforms and send them out to sea where they can be sunk by U.S. attack submarines in a war? And if Chinese planners know that the sea-based deterrent is much more vulnerable than its land-based deterrent, why do they waste money on the SSBN program?

The answer is probably a combination of national prestige and scenarios involving India or Russia that have less capable anti-submarine forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Missile Mystery in Beijing

|

| The mysterious DF-41 missile did not appear at the Chinese National Day parade on October 1st, but the Chinese Ministry of National Defense says the DF-31A did. But did it, or was it in fact the DF-31? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The military parade at China’s 60th National Day celebration last week was widely rumored to be displaying a new long-range ballistic missile described in the news media as the DF-41. The rumors turned out to be, well, rumors.

Instead the Chinese Ministry of National Defense identified two other missiles: the nuclear DF-31A and the conventional DF-21C, to my knowledge a first.

But was it the DF-31A that rolled across the square or the shorter-range DF-31 already displayed ten years ago at the 1999 parade?

What Was Displayed: DF-31A or DF-31?

The Chinese Ministry of National Defense web site carries several pictures (backup copy here) that identify the DF-31A, the long-range version of the DF-31 mobile ICBM, taking part in the parade. No DF-31s were identified. The U.S. intelligence community estimates that the DF-31A with a range of 11,200+ kilometers (6,959+ miles) is capable of striking targets throughout the United States and Europe. The missile is thought to carry a single warhead, was first deployed in 2007, and less than 15 are currently deployed.

The identification is curious because the DF-31A mobile launcher displayed in the 2009 parade is almost identical to the DF-31 launcher displayed in the 1999 parade. I’ve been going through all my images of Chinese mobile launchers and I cannot see any significant difference between the two. The only apparent difference is that the eight-axle truck has been upgraded and painted. But the missile canister on the “DF-31A” launcher appears to have the same dimensions as the one on the DF-31 launcher (see Figure 1).

|

Figure 1: |

|

| The DF-31A launcher identified by the Chinese Ministry of Defense at the 2009 parade (top) is almost identical to the DF-31 launcher displayed at the 1999 parade (bottom). Do the two missiles use a common mobile launcher or did the Chinese government re-display the DF-31? Images: Chinese Ministry of National Defense |

.

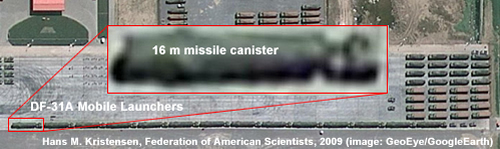

And it’s not as if there were two different long-range missile launchers in the area. A satellite image taken on June 23, 2009, and first described in China Brief, shows what appears to be the military vehicles rehearsing at Tongxian Air Base in the outskirts of Beijing in preparation for the parade. A line-up of 14 mobile launchers for long-range missiles all appear to have the same overall dimensions, including a 16-meter missile canister, and appear to be the “DF-31A” launchers identified in the parade (see Figure 2).

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Fourteen vehicles of what the Chinese Ministry of National Defense says are DF-31A missiles launchers lined up at Tongxian Air Base prior to the 2009 National Day parade all appear to have the same overall dimensions. Image: DigitalGlobe/Google Earth |

.

Do the DF-31 and DF-31A use the same or a very similar mobile launcher? Or were the launchers displayed in Beijing in fact DF-31s but misidentified on Chinese television and the Chinese Ministry of National Defense web site as DF-31As? It’s hard to imagine the Ministry misidentifying the DF-31 as the DF-31A. But although there are no official public comparisons of the two missiles and their launchers (except the DF-31 has two stages and the DF-31A has three), the DF-31A is assumed to be longer than the DF-31 – 18 meters versus 13 meters, according to Jane’s Strategic Weapons Systems. If so, the launchers displayed at the parade were too short for the DF-31A and must have been for the DF-31.

The Mysterious DF-41 (or still-to-be-seen DF-31A)?

The news media widely reported that the DF-41 would be displayed at the parade. The rumors about the missile seem to have fed off private web sites that claim the existence of a missile called DF-41. There is no official confirmation of this missile and a 2009 report from the U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Agency does not list a DF-41 missile or any other new Chinese long-range ballistic missile under development even though it lists new missiles under development by other countries.

The rumors about the DF-41 were so prevailing that an interviewer on the Chinese CCTV 4 Focus Today program the day before the parade kept asking Major General Zhang Xinan, the Assistant Director of the Second Artillery Corps’ Political Department, about the missile. But the General appeared to caution about what he called the “so-called DF-41,” saying that “this mystery will be cleared up tomorrow in the parade.” He did not dismiss the existence of a DF-41, but no such missile launcher rolled across the square.

Even so, photos have been circulating on the web for several years allegedly showing what appear to be a Chinese mobile missile launcher that is clearly different from the DF-31. Many have speculated that the launcher is for the elusive DF-41. Is it, or could this be the launcher for the DF-31A, or something completely different?

|

DF-31A or DF-41 Mobile Launcher? |

|

| Images of a Chinese eight-axle mobile missile launcher have circulated on the web for years, said to be for the DF-41 missile. Is it, or is it for the DF-31A, or something else? Images: Web |

.

The JL-2 Payload

Finally, although the Chinese Navy’s new Julang-2 sea-launched ballistic missile was not displayed at the parade, the CCTV 4 Focus Today program interviewed Du Wenlong, identified as a “researcher” from the Chinese Academy of Military Science, who said the JL-2 “penetration capability and number of carried warheads have been raised to a large degree” compared with the JL-1.

The JL-2 is expected to carry some form of penetration aids, but it would be a surprise if it carries more than one warhead. Whether the “researcher” is in a position where he would know what JL-2 will carry or is talking in general terms is unclear, but the U.S. intelligence community has consistently – most recently in June this year – assessed that the JL-2 carries a single warhead.

Final Observations

It would be interesting if the DF-31 and DF-31A use a similar mobile launcher. It would mean that estimates of an 18-meter DF-31A are wrong; the missile would have to be less than 16 meters to fit inside the launcher that was displayed at the parade as the DF-31A. A common launcher would have some serious implications for crisis stability in a hypothetical war between China and the United States because a launch of a DF-31 against regional targets initially could be misinterpreted by the U.S. military as a nuclear attack on the U.S. mainland, and lead to further escalation of the war.

But it would certainly be curious if the Chinese Ministry of National Defense claimed to display the DF-31A but instead re-displayed the DF-31.

Not Getting It Right: More Bad Reasons to Have Nuclear Weapons

A recently released report, U.S. Nuclear Deterrence in the 21st Century: Getting It Right, by the ad hoc New Deterrent Working Group with a forward by James Woolsey, is an interesting document. I believe this report is significant because it might typify the arguments that will be used against arms control treaties in the upcoming Senate debates.

Much of what is written in support of existing nuclear policies is such a logical muddle that one hardly knows where to start in a critique. As a statement of the pro-nuclear position, this paper is clearer than most so worth addressing. It makes the errors that others do when arguing for nuclear weapons, specifically, making statements about the “requirements” for nuclear weapons that imply missions left over from the Cold War, but the report is particularly blunt in its demands and might serve as a good example of the pro-nuclear arguments. The report is almost seventy pages long, so I can’t touch on every point in a blog and I think I will leave the arguments about nuclear testing for a separate blog to follow.

The report starts out with one fundamental mistake contained in almost every discussion on nuclear weapons: It conflates nuclear weapons with deterrence. Nuclear weapons are so thoroughly equated with deterrence—they are often simply called “the deterrent” —that we seldom stop to think about the details of how this deterrent is supposed to work. What is being deterred, whom, how, for what purpose? If we do not know what nuclear weapons are for, what their missions are, what their targets are, then it is impossible to pin down what their performance characteristics ought to be.

Uncertainty, Reliability, and Safety

The report argues that we need nuclear weapons in part because the world and the future are very uncertain. The report admits no one knows the answers to any of the questions above so the United States simply has to make certain that it has sufficient numbers of nuclear weapons with a variety of capabilities and hope for the best. The problem with this approach is that planning for uncertainty is never finished; we never reach an endpoint. For example, the heading on p. 25, “U.S. nuclear weapons are deteriorating and do not include all possible safety and reliability options” is not only true but always will be true. The “deteriorating” fear has been refuted: parts in weapons age, and these parts are being replaced when needed so the weapons remain within design specifications. This is not cheap or simple but neither is it impossible and can continue for decades. But admittedly, nuclear weapons do not have “all possible safety and reliability options.” There are, no doubt, “options” no one has even thought of yet. So how much reliability and safety is enough? When can we stop?

The answer depends on the missions for nuclear weapons. If nuclear weapons had only the mission of retaliating against nuclear attack, to inflict sufficient pain to make such an attack seem pointless in the first place, then one could plausibly argue that 90% reliability is adequate. If the United States needs to destroy, say, ten targets to inflict sufficient pain to deter, then which ten is not absolutely critical and it could fire at eleven targets and accept that one might escape. Even if the United States wanted to use nuclear weapons to attack and destroy stocks of chemical and biological weapons, it could fire a nuclear weapon at the target and, if one in ten does not go off, it could fire off another bomb an hour later. It is not as though we will not know whether a nuclear bomb actually went off, that will be pretty obvious. If, on the other hand, the United States wants to conduct a surprise, disarming first strike against Russian central nuclear forces, destroying its missiles on the ground, then there is a huge difference whether the attack is 90%, 95%, or 99.9% successful. If the Russians have a thousand warheads, that is the difference between 100, 50, or 1 surviving, obviously significant. So, to say that nuclear warheads need a certain reliability, specifically a high reliability, is to imply certain missions. But these are missions that nuclear advocates rarely want to acknowledge explicitly because they know what a hard sell it will be while “reliability” seems like an obvious, inarguable good quality to have.

What about safety? Certainly we should have nuclear weapons that are as safe as possible and no effort should be spared to make them safer, right? In fact, the Working Group does not agree. The safest nuclear weapons are the ones that do not exist, so ultimate safety calls for nuclear abolition, an option explicitly rejected by the Working Group. If we are going to have actual nuclear weapons, they could be made safer by storing them disassembled. If we need assembled warheads, they could be made safer by removing them from their missiles. Warheads on missiles could be made safer by taking the missiles off alert. All of these options are explicitly rejected by the Working Group. What the report really means when it says we should have “all possible” safety options is that we should fund the National Labs at high levels forever but not change deployments one iota in the interest of safety, hardly my definition of “all possible.”

How Much Is Enough?

The rest of the report makes claims that are unproven and often unprovable and sets requirements for nuclear weapons that sound as though the Cold War never ended. I understand that even in a report of seventy pages not every statement can be fully analyzed and supported but, even so, there are a score of amazing claims for nuclear weapons that are supported mostly by lots of quotes.

The report makes the error of discussing the numbers of nuclear weapons in terms of reductions, specifically since the Cold War (p. 11). All references to reductions imply the Cold War is a benchmark by which current arsenals are measured. But the world has been turned on its head since then and comparison to Cold War numbers is neither relevant nor enlightening. (The Navy also has fewer battleships than it did in World War II. The point is?)

The report states (p. 11), “In a number of cases, a robust American nuclear arsenal has proven to be effective not only in deterring attacks on the United States and its allies from adversaries using weapons of mass destruction.” This may be true but it is very hard to know. Failures of deterrence are obvious but, if some action does not happen, then why did it not happen? Was the action every really considered? Was it considered but rejected for some other reason? Or was it deterred? Arguments about the effectiveness of deterrence are inevitably going to be speculative and based on absence of evidence. As Donald Rumsfeld pointed out while Secretary of Defense, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. There is no doubt that deterrence is real in many cases, it really works in many cases, but it is very difficult to be certain when and where. We should all (me included) be very cautious when making arguments about deterrence. I believe that general discussions of deterrence almost always go off the rails. When we talk about deterrence, we should at least try to use concrete examples for discussion. In the case of nuclear weapons, going to some example, any example, almost always demonstrates that the arguments in favor of nuclear weapons are simply incredible.

The report states (p. 12), “In short, the available evidence suggests that an American nuclear deterrent that is either qualitatively or quantitatively insufficient will have the effect of encouraging the very proliferation of nuclear forces we seek to prevent.” This might be tautologically true if the definition of “insufficient” is chosen to make it true. But there is no “available evidence” for the simple reason that the “American nuclear deterrent” (note again how nuclear weapons are thoughtlessly referred to as the “deterrent”) has never been anywhere near “insufficient” since 1945. So exactly when was this experiment conducted? Later (p. 51) the reports states, “To the contrary, history has clearly shown that unilateral US reductions, far from causing a similar response, actually stimulate nuclear buildups by adversaries.” What can they be talking about? Russia, Britain, France, and China went nuclear while the U.S. arsenal was expanding or just plain huge. The nuclear arsenal of the United States declined from its peak because of the retirement of thousands of battlefield nuclear weapons made obsolete by modern precision conventional alternatives. Did South Africa, India, Israel, Pakistan, or North Korea really go nuclear because of “unilateral US reductions”? These confident statements are based on a “history” of some parallel universe.

The report asserts that China has “its own extensive military modernization program.” China, with a growing economy is naturally increasing its overall budget but its nuclear ambitions continue to appear quite restrained. Hans Kristensen has written extensively on this.

Hydronuclear Alert

The report asserts that Russia is conducting hydronuclear tests, that is, nuclear weapon tests with very small nuclear yields, tests that the United States would consider in violation of the Comprehensive Test Ban. This is a common claim from pro-nuclear people, based, apparently on highly classified reports that are repeated here in this unclassified document. Some of the authors of the report have or had security clearances so any claim to the contrary is met with “if only you knew what I know.” All I can say is that I have asked people who do know what the authors know and apparently the evidence is unclear, specifically, the United States does not have good enough detection capability to prove that the Russians are not conducting such tests. If the Russians are conducting such tests, and the pro-nuclear lobby has already let the cat out of the bag, the intelligence community should present testimony in Congress confirming the tests. As far as I know, they have not done so. Even so, note that the fuss is about a treaty that the United States has not ratified. Upon ratification, the United States and Russia (and perhaps China) could agree in parallel to place instruments at each other’s tests sites and resolve this ambiguity.

Nuclear Weapons Ready to Fly.

The report advocates, even assumes, an aggressive nuclear stance, with weapons constantly ready to go. For example, (p. 15): “Finally, the continued credibility and effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear deterrent precludes de-mating of warheads on operational systems or otherwise reducing the alert rates or alert status of U.S. forces.” Again, we should apply this general statement to a few concrete examples. First, by arguing against reducing alert rates they are endorsing current alert rates. While the report objects to the term “hair trigger alert,’ U.S. nuclear weapons are, in fact, ready to launch on a few minutes’ notice. At any given moment, many are deployed on submarines off the coast of China and Russia, atop missiles just a few minutes flight time from their targets. Do they really mean that an enemy will not be deterred if these conditions are relaxed? We have to imagine a scenario in which the leader of China, Russia, or maybe North Korea want to use nuclear weapons against the United States but, knowing that they will be hit back 40 minutes later are deterred. Then their head of military intelligence comes in and reports that the American nuclear bombs won’t arrive until eight hours later, or perhaps the next day, or whatever, and as a result the enemy leader says, “Well, in that case, let’s attack.” Perhaps someone else can think of a case in which this is plausible but I cannot.

Later (p. 59), the report does try to give some further justification for high alerts: “They [nuclear weapons] must be known to be ready and useable to have deterrent effect. No START follow-on agreement can be deemed in the national security interest if it would require downgrading of that condition and, thereby, potentially leave the United States vulnerable to coercion based on the threat of second or third strikes before we could respond to an attack.” This actually makes some sense but we have to think about what it really means. It means keeping a constant counterforce attack capability. The statement above says that, if Russia (in the context of START, we are talking about Russia) attacks the United States with nuclear weapons, the next act of the United States should be to attack all remaining Russian nuclear weapons so they can’t do any more damage. That sounds plausible but let’s think this though. The Russians can safely assume the Americans will be more than a little upset after a nuclear bomb has gone off. The Russians will know that their vulnerable weapons could be attacked so they would either disperse their weapons to make them invulnerable or they would use them. It might be that keeping a counterforce capability results in the Russians throwing everything they can throw at the United States in the first wave, actually increasing the damage to the United States in a contest that would otherwise have smaller stakes. I have written elsewhere how high U.S. alert rates make reductions in nuclear forces more difficult for Russia. Moreover, the report completely neglects the costs of high alert rates, not just the financial costs but the risks of accidental nuclear launch, either by the United States or Russia, and the danger of Russian mitigating tactics, and the loss of escalation control. The authors fail to imagine that the United States and Russia might negotiate mutual force postures that include weapons off alert that are mutually invulnerable, creating a much more stable nuclear environment. The authors seem to believe that a Cold War Lite is the only way the world can be. They cannot see over the hill into the next valley.

The report makes a series of other remarkable and unsupportable claims, but I want to address those in a separate blog about nuclear testing.

New Air Force Intelligence Report Available

By Hans M. Kristensen

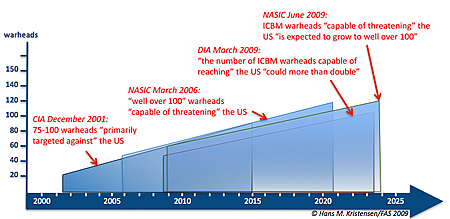

The Air Force Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published an update to its Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat. The document, which I obtained from NASIC, is sobering reading.

The latest update continues the previous user-friendly format and describes a number of important assessments and new developments in ballistic and cruise missiles of many of the world’s major military powers.

The report also helps dispel many web-rumors that have circulated about Chinese, Russian, Indian and Pakistani nuclear forces.

In this blog I’ll focus on the nuclear weapon states, particularly China.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

As the DF-3A retirement continues (there are now only 5-10 launchers left of close to 100 in the 1980s), the liquid-fuel missile is being replaced by a family of solid-fuel DF-21 variants. The NASIC identifies four, including two nuclear versions (Mod 1 and Mod 2), one conventional version, and an anti-ship version that unlike the others is not yet deployed.

Thankfully, the report dispels widespread speculation by web sites, news media, and even Jane’s after images began circulating on the Internet, that a DF-25 had been deployed, some even said with three nuclear warheads. But it was, as I predicted last year and NASIC now confirms, in fact a DF-21.

|

DF-21 Road-Mobile Launchers |

|

| A column of DF-21s on the road in what could be the Delingha deployment are in Qinghai Province. Several of the vehicles have identical camouflage patterns, raising suspicion that the image has been manipulated. Four DF-21 versions exist, two nuclear, one conventional, and one anti-ship version. Image: Web |

.

The report also reaffirms that the first of the DF-31s and DF-31As “have been deployed to units within the Second Artillery Corps,” and NASIC estimates that “less than 15” are deployed, up from the “less than 10” estimate in the Pentagon’s March 2009 report (which actually used 2008 data).

The NASIC report states that neither of China’s two types submarine-launched ballistic missiles is operational. This suggests that the multi-year overhaul of the JL-1 equipped Xia SSBN, which was completed last year, was not successful. The successor missile JL-2 for the new Jin-class SSBNs has not reached operational status either. NASIC gives the JL-2 the U.S. designation CSS-NX-14, not a numerical follow-on to the JL-1, which is listed as CSS-NX-3. The “14” could be a typo, but it appears several places in the report. The JL-2 is shown to have roughly the same dimensions as the Russian SS-N-32 SLBM.

NASIC lists single warheads on all of the Chinese missiles, not multiple warheads as speculated by many. “China could develop MIRV payloads for some of its ICBMs,” the report states. Yet it also predicts that, “Future ICBMs probably will include some with multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles.” Whether that prediction – which appears to hint that China has more ICBMs under development – comes true remains to be seen, and the U.S. intelligence community has stated for years that one development that could trigger it is a U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

The report echoes recent statements from other branches of the U.S. intelligence community that the number of warheads on Chinese ICBM capable of reaching the United States could expand to “well over 100 in the next 15 years.” Unfortunately, “well over 100” can mean anything so it is hard to compare this NASIC’s projection with the CIA projection from 2001 of 75-100 warheads “primarily targeted against the United States” by 2015. That projection only included DF-5A and DF-31A capable of targeting all of the United States, with the high number requiring multiple warheads on DF-5A. But the timeline for the anticipated increase has slipped considerably from 2015 to 2024.

.

Moreover, ICBMs “primarily targeted against the United States” is a smaller group of missiles than those “capable of reaching the United States,” which currently includes about 60 DF-4, DF-5A, DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs with as many warheads. For this group to grow to “well over 100 warheads” suggests that NASIC anticipates that China will deploy at least 60-70 DF-31, DF-31A and JL-2 missiles by 2024 (the DF-4 will probably have been retired by then). Assuming that includes 36 JL-2s on three Jin-class SSBNs, an additional 20-30 total DF-31s and DF-31As would have to be deployed to reach 120 ICBM warheads. If five SSBNs were deployed, then only 10 additional land-based ICBMs would be required, or 30 if the 20 DF-5As were retired.

The DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is listed as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation used for the nuclear and conventional Russian AS-4. But unlike the 2009 DOD report on Chinese military forces, which lists 150-350 DH-10s deployed with 40-50 launchers, NASIC lists the operational status as “undetermined.”

Russian Nuclear Forces

NASIC states that “Russia retains about 2,000 warheads on ICBMs,” which is far too many for the land-based ICBM force and so probably includes SLBMs as well. The ICBM force will continue to decrease due to arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints. Even so, “Russia will probably retain the largest ICBM force outside the United States,” and “most of these missiles are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” according to NASIC.

|

|

The multiple-warhead RS-24 ICBM is, according to NASIC, not a new missile but a modified version of the SS-27 (Topol-M). |

The NASIC report formally designates the “multiple” warhead RS-24 ICBM to be a modification of the SS-27 Mod 1. This has some significance because Russia under START is not allowed to increase the warhead loading on missiles declared under the treaty, but in anticipation of the treaty expiring in December 2009 apparently has been working on doing so anyway. The RS-24, which will exist in both silo and road-mobile versions, is not yet deployed but Russian military officials have said this will happen in December.

On the submarine force the modified SS-N-23 known as Sineva is listed as carrying the same number of warheads (4) as the original version, far less than the “up to 10” listed by NASIC in 2006 and by Russian news media. The range is listed as the usual 8,000+ km even though the Russian Navy claimed in October 2008 to have test-flown the missile to 11,547 km. NASIC also continues to list two remaining Typhoon-class SSBNs as capable of carrying the SS-N-20, even though the missile is reported to have been withdrawn from service. I suspect this is because the report uses START-counted missile tubes. A third Typhoon SSBN has been converted as a test platform for the SS-N-32/Bulava-30, and NASIC lists this submarine with 20 tubes for the new missile.

Interestingly, the kh-102 cruise missile, a replacement for the AS-15 long rumored to be under development, is not listed by NASIC.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Even though Indian news media reports and private/corporate institutes have reported for years that Agni I and Agni II were deployed, the NASIC report shows that operational deployment of the road-mobile Agni I SRBM has only recently begun, with “fewer than 25” missile launchers deployed. NASIC seems to back our assessment from last year that the Agni II at that time was not yet fully operational, by listing “fewer than 10” launchers deployed.

Two short-range sea-based ballistic missiles are under development: Dhanush and Sagarika. Neither is operational yet, and NASIC safely estimates that the Sagarika will become operational sometime after 2010.

Despite Indian news media reports of development of a nuclear-capable cruise missile, no mentioning of such a weapon system is made by NASIC.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

There are fewer than 50 launchers for the road-mobile Ghaznavi and Shaheen I SRBMs listed in the NASIC report, and the 2,000+ km Shaheen II MRBM is not yet operational but may be soon. Pakistan also appears to have two nuclear-capable cruise missiles under development: the ground-launched Babur and the air-launched Ra’ad.

Other Nuclear Weapon States

Although “friendly” nuclear weapon states are not included because they are not a “threat” to the United States, the report’s section on cruise missiles is nonetheless interesting because it – unlike the ballistic missile sections – describes weapon systems of “friendly” nuclear weapon states such as France and Israel. Yet nuclear systems, such as the French ASMP-A, are excluded. Israeli submarine-based cruise missiles, which have been rumored to have nuclear capability (I’m not convinced), are not included either.

Curiously, even after two nuclear tests and the intelligence community stating for more than a decade that North Korea has nuclear weapons, the NASIC report does not list any of North Korea’s weapons as “nuclear” or “conventional or nuclear.” That is, I think, interesting.

Background Information: 2009 NASIC report | Previous NASIC reports

A Chinese Seabased Nuclear Deterrent?

|

|

An article in USNI, which carries this photo of USS Hartford (SSN-768) damaged in a recent collision, discusses China’s ballistic missile submarines. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The magazine U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings has an interesting article about China’s nuclear ballistic missile submarines written by Andrew S. Erickson and Michael Chase from the U.S. Naval War College. And I’m not just saying that because they reference several of my publications about China, but because they provide an interesting discussion of the possible motivations for China’s emerging sea-based nuclear force.

I, for one, have always wondered why, if China’s current strategic modernization is intended to reduce the vulnerability of its long-range nuclear deterrent, would China want to cluster a significant portion of its missiles on a few submarines and send then out to sea where U.S. attack submarines can hunt them down?

In theory a sea-based nuclear deterrent is invulnerable because it can hide. But given that the U.S. Navy’s Maritime Strategy in the 1980s was explicitly designed to find and sink Soviet ballistic missile submarines before they could launch their missiles, how secure will China’s sea-based nuclear deterrent actually be? Or how would China react in a crisis, if one of the submarines went missing due to an accident?

.

Strategic Failure: Congressional Strategic Posture Commission Report

|

| The final report from the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission seems focused on hedging rather than leading. |

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

The Congressional Strategic Posture Commission report published today is definitely not the place that the President or the nation should look for new ideas on how to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and lead the world toward a world free of nuclear weapons.

Even for a compromise document written by a diverse group, it is a work of deeply disappointing failure of imagination. The recommendations can be summarized as: the nuclear world should stay pretty much the way it is but at slightly lower force levels, incrementalism is the most we can hope for, and even that should be approached very cautiously.

The report comes close to dismissing the President’s vision of a world free of nuclear weapons – and the enthusiastic support it has generated worldwide – as a utopian dream: “The conditions that might make the elimination of nuclear weapons possible are not present today and establishing such conditions would require a fundamental transformation of the world political order.” The United States should retain a viable nuclear deterrence “indefinitely.” The Commission surrenders to the nuclear problems of the world rather than recommending a proactive way forward out of the mess.

Of course, the Commission is not opposed to nuclear reductions per se and supports them under certain conditions, but it recommends that the approach “balances deterrence, arms control, and non-proliferation. Singular emphasis on one or another element,” the report says, apparently hinting at disarmament, “would reduce the nuclear security of the United States and its allies.”

If the Commission’s report is any preview of the Pentagon’s Nuclear Posture Review, we should expect minimal changes in nuclear forces, structure, or mission. The report recommends a nuclear policy of “leading and hedging” but seems to be focused on hedging.

The Nuclear Mission and Deterrence

While President Obama believes the United States should “put an end to Cold War thinking” and “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, and urge others to do the same,” the Commission offers little support for this approach or analysis of what it would mean.

Indeed, while the report concludes that, “…as long as other nations have nuclear weapons, the U.S. must continue to safeguard its security by maintaining an appropriately effective nuclear deterrent force,” the Commission fails to ask fundamental questions about what nuclear weapons are for and what their character should be. This is probably because there was no consensus on these matters, but better to ask the question and admit they have no answer than to simply state over and over again that nuclear weapons are for “deterrence.” Since some will believe that “appropriately effective” is two thousand nuclear weapons and others think it will be twenty, what does the statement mean?

But it is also an assertion that should be, but is not, challenged. Does this really mean that if North Korea has one nuclear bomb, intended to counter our overwhelming conventional capability, we need to have nuclear weapons to counter it? That may be true but it is certainly not clear to us and should not be asserted as though it needs no explanation. Elsewhere the report says the United States faces decisions about how to reduce “nuclear weapons to the absolute minimum.” Again, two honest people could agree on this goal and differ by a factor of a hundred or a thousand on what an “absolute minimum” is. When the United States had 32,000 nuclear weapons, that was also considered the “absolute minimum” needed for national security.

Without examination of the mission of nuclear weapons, how can we say what their characteristics should be? Even if nuclear weapons are for deterrence, how do they deter? What are their targets? How should those targets be attacked? If we do not answer, or even ask, those questions, how can we say that we need high levels of reliability? How can we say we need land-based missiles that can be launched on a moment’s notice? How can we say we need a vast nuclear weapons complex to design complex two-stage thermonuclear weapons with hundreds of kilotons of yield? There are other examples as well, about reliability, safety, and so on, that presume missions for nuclear weapons that simply should not be presumed.

The Commission acknowledges that it is difficult to replicate the “relatively simple” deterrence calculus of the Cold War, determined by the damage inflicted, in today’s much more complex and fluid security environment. Even so, the report states, the United States still “needs a spectrum of nuclear and non-nuclear force employment options and flexibility in planning along with the traditional requirements for forces that are sufficiently lethal and certain of their result to threaten an appropriate array of targets credibly.” The justification for this sweeping conclusion about capabilities is that “the security environment has grown more complex and fluid.”

As with so many discussions of nuclear weapons, the use of the term “deterrence” in particular is confused and the logic self-referencial. Throughout the report, in too many places to cite, are repeated explicit declarations that nuclear weapons are for deterrence. The report frequently makes the mistake of talking about nuclear weapons and deterrence and then slipping into the error of assuming that deterrence must be nuclear deterrence, or the report makes true statements about deterrence but then implies that the deterrence must be effected with nuclear weapons. It repeatedly refers to our nuclear forces as our “deterrent” or our “deterrent forces” as though they were the same thing. Nuclear weapon designers are maintaining their “deterrent skills.”

In describing the role of deterrence, the Commission glosses over many important developments that have shaped U.S. nuclear policy, strategy, and doctrine over the years. “In a basic sense, the principal function of nuclear weapons has not changed in decades: deterrence. The United States has these weapons in order to create the conditions in which they are never used,” the report declares. Yet we recall hugely important developments ranging from Mutual Assured Destruction, flexible response, adaptive planning, Global Strike, and preemptive strike options, all of which changed the policies and conditions under which the weapons might be used. The report’s more accurate statement would be: “Presidents have not changed their reluctance in decades to authorize use of nuclear weapons.”

Likewise, the report does not describe the important development after the end of the Cold War, where U.S. nuclear targeting policy expanded from Russia and China and their satellite states to deterring all forms of weapons of mass destruction use by six individual countries today (some of which do not have nuclear weapons).

Non-Use and First Strike

One of the most important conclusions in the Commission report is that the “tradition of non-use serves U.S. interests and should be reinforced by U.S. policy and capabilities.” But what that implies for policies and capabilities is not explained.

Even so, the Commission concludes that not only must U.S. nuclear forces be able to retaliate against an attack, “the United States must also design its strategic forces with the objective of being able to limit damage from an attacker if a war begins.” Such damage-limitation capabilities “are important because of the possibility of accidental or unauthorized launches by a state or attacks by terrorists,” and can be achieved “not only by active defenses, such as missile defenses, “but also by the ability to attack forces that might yet be launched against the United States or its allies.”