118th Congress: National Security

The 21st century will be shaped by the US-China strategic competition. The United States and China are locked in a battle for global power, influence, and resources, and are fighting for control of the world’s most important geopolitical regions, including the Indo-Pacific and Africa. They are also vying for leadership in cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), 5G, quantum computing, and cybersecurity. This competition is not just about economic dominance; it is also about ideology and values. To ensure that we can lead in today’s world, the United States must innovate. If we don’t, we may fall behind.

Below, we provide concrete, actionable policy proposals to help the 118th Congress meet this moment. These proposals will protect our troops, cultivate an agile and effective military, and develop a national security industrial base that allows America to lead in critical emerging technologies.

Medical Readiness. To support our troops, Congress should take steps to maintain military medical readiness. Generally, at the start of a given war, the American battlefield mortality rate is higher than it was at the end of the previous war, suggesting that military medical capabilities erode between wars. This erosion is responsible for the deaths of hundreds of American troops. To better protect our troops, Congress should direct the Department of Defense to expand military-civilian partnerships (MCPs) to pursue a national goal of eliminating preventable deaths, as detailed in the above memo.

Cultivating a 21st Century National Security Innovation Base. The National Security Commission on AI warned that a digital-talent deficit at the Department of Defense (DoD) represents the greatest impediment to the U.S. military’s effective embrace of emerging technologies. To address this challenge:

- Congress should create a national civilian “STEM Corps” modeled after the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps and the National Guard, as introduced in HR 6526 in the 116th Congress. A competitive process would select students to receive full tuition to attend public universities. In return for accepting the scholarship, graduates would commit to several years serving in either the “active” or “reserve” STEM Corps. Additionally, Congress should work with the DoD lengthen Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) rotations, allowing DoD representatives more time to establish strong networks in Silicon Valley. The DIU should also continue to hire rapidly from those ecosystems.

- Nearly half of all STEM PhDs and 60% of computer science PhDs in the U.S. are awarded to international students. Barriers in recruiting this talent hurt our Defense Industrial Base. Congress should create a path to citizenship for noncitizen technologists through military service, and make some changes to existing law governing U.S. military eligibility. Additionally, Congress should increase green card caps for advanced STEM degree holders working in critical industries for national defense, and establish a National Security Innovation Visa to grant DoD the ability to recruit top global STEM talent.

Combating Increasing Global Threats. Many threats to national security can only be effectively countered by working with allies. To effectively combat such challenges, we must strengthen U.S. Engagement in International Standards Bodies. The U.S. should also lead in the formulation and ratification of a global treaty on artificial intelligence in the vein of the Geneva Conventions, the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to establish guardrails and protections for the civilian and military use of AI, as recommended by the Future of Defense Task Force.

Increasing Military Efficiency. Greater military efficiency can also be achieved by cutting down on unnecessary expenses. We can save billions on the U.S. nuclear deterrent by directing the Pentagon to wind down its current efforts to deploy an entirely new missile force, instead extending the life of our current arsenal of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs).

Appropriations Recommendations

To protect American technological advantage and compete with China across all aspects of America’s national security strategy:

- The National Defense Education Program: The Department of Defense is not only working to create high end emerging technologies, but also putting resources into training the STEM workforce, which is essential for the safety of our country. To ensure that this expertise comes from a variety of backgrounds, we must offer chances to students and teachers of all ages in underprivileged and underrepresented communities, those with ties to the military, and veterans. The National Defense Education Program does just that, and we must ensure it continues receiving full support of Congress. The program element was funded at $145 million in FY 2022.

- The role of the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) has become especially important on the technology competition front, as previously highlighted by members of the Foreign Affairs Committee. By enforcing export controls, BIS can limit China’s access to technologies like AI which are used for military ends, thereby protecting America’s national security. To ensure that BIS can effectively enforce these export controls, we recommend appropriating additional funding to BIS to support their critical work.

- While well-enforced export controls ensure that the U.S. leads in the development of AI systems, we must also ensure that we advance AI technologies safely and responsibly. Congress should appropriate robust funding to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to support their work on trustworthy AI. The CHIPS and Science Act authorizes funding to establish NIST AI test beds (Sec. 10232), appropriations for which are critical.

- The National Defense Authorization Act of 2019 established the National Security Innovation Capital (NSIC) program in response to worries that American hardware startups were unable to secure sufficient funds from trustworthy domestic sources. Less than 30% of U.S. venture capital investments go towards hardware businesses, and less than 10% is invested during the early phases when it’s needed most. Many times, these startups have had to depend on overseas investors, leaving them open to the risk of their intellectual property being taken by possible adversaries. In February 2021, the DIU established this fund as a result of $15 million in appropriations from Congress. Ensuring this program is fully funded every year is critical to our global competitiveness and national security.

118th Congress: Ensuring Energy Security

Recent crises, such as the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, have led to volatile fossil fuel prices and raised national concerns about energy security. The growing frequency of blackouts across the country due to extreme weather points to an increasingly vulnerable and aging electric grid. Grid capacity right now is incapable of supporting the rapid deployment of renewable energy projects that can generate clean, reliable, domestic energy. Further, as global competition rises, the United States finds itself overly reliant on foreign manufacturing and supply chains for these very technologies we want to deploy.

In order to improve energy security, affordability, and reliability for everyday Americans, the 118th Congress should act decisively to strengthen our energy infrastructure while leveraging emerging energy technology for the energy system of the future. Below are some recommendations for action.

Transmission Lines. The current U.S. electrical grid is an aging piece of infrastructure with sluggish growth and increasing vulnerability to threats from extreme weather and foreign attacks. The 118th Congress should implement policies to revitalize domestic manufacturing and construction, strengthen national energy security and reliability, and generate new jobs and economic growth. The $83 billion worth of planned transmission projects that the ISO/RTO Board has approved or recommended is projected to add $42 billion to U.S. GDP, create more than 400,000 well-paying jobs, and boost direct local spending by nearly $40 billion. However, the rate of construction for new transmission lines must substantially increase to fully harness the new energy economy and achieve ambitious emissions reductions.

High voltage direct current (HVDC) transmission lines are particularly important for connecting renewable energy producing regions with low demand, such as the Southwest and Midwest, to high demand regions. At these distances greater than 300 miles, HVDC transmission lines transmit power with fewer losses than AC lines. HVDC lines can also avoid some of the challenges to AC transmission line development because they can be buried underground, eliminating resident concerns of visual pollution and avoiding vulnerability to extreme weather. Further, if HVDC lines are built along existing rail corridors, their construction only requires negotiation with the seven major American rail companies rather than a myriad of private landowners and federal land management agencies. Congress took an important first step to advancing HVDC technology by directing DOE to develop an HVDC moonshot initiative on cost reduction, as part of the FY 2023 omnibus bill. Now, the 118th Congress can further support this goal by working with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to eliminate regulatory obstacles preventing the private sector from building more of these lines along existing corridors. Congress should also create federal tax credits to stimulate domestic manufacturing and construction of HVDC transmission, as well as transmission line construction in general.

Manufacturing. To spur domestic manufacturing capabilities and regain competitive advantages in clean energy technologies, the 118th Congress should fund a new manufacturing-focused branch of DOE’s highly effective State Energy Program (SEP). Congress can double down on this action by scaling investments in domestic capacity to manufacture key industrial products, such as low-carbon cement and steel.

Workforce. Our nation needs a workforce equipped with the skills to build a robust energy economy. To that end, Congress could provide the Department of Energy (DOE) with $30 million annually to establish an Energy Extension System (EES). Modeled after the USDA’s Cooperative Extension System (CES), and in partnership with the DOE’s National Labs, the EES would provide technical assistance to help institutions and individuals across the country take full advantage of emerging opportunities in the energy economy, including carbon capture and storage (CCS), installation and maintenance of electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure, geothermal power, and more.

Permitting Reform. In order to improve government efficiency, reduce costs, and enable the construction of new infrastructure for the clean energy transition, the 118th Congress should pass legislation on permitting reform to improve National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) compliance timelines. These reforms should include:

- Shortening the statute of limitations on litigation under NEPA to 6 months or less in order to be more consistent with state-level policies;

- Requiring that any public-interest group bringing a case against a NEPA decision to have submitted input during public comment periods;

- Clarifying the duties of federal, state, tribal and local governments when conducting environmental reviews and communicating information to project applicants and the public;

- Clarifying vague statutes, such as the requirement that agencies consider “all reasonable alternatives”;

- Clarifying the appropriate admissibility or substitutability of documents that may reduce burdens on executive staff; and

- Permitting fast-track approval to site zero-emission fueling stations (see next section), in consultation with local utility regulators.

Zero-Emission Fueling Stations. Zero-emission vehicles powered by electric batteries and hydrogen fuel cells are the future of American auto manufacturing. The 118th Congress should pass key legislation to provide the federal government and states with the authorities and resources necessary to build a nationwide network of zero-emission fueling stations, so these new vehicles can refuel anywhere in the country. This includes:

- Amending Title 23 in the United States Code so that the federal government and states can apply gas tax dollars towards funding zero-emission fueling stations;

- Directing the Department of Transportation to use “Jason’s Law” surveys to identify medium- and heavy-duty vehicle parking locations that should be used for zero-emission fueling stations; and

- Authorizing pilot programs and public-private partnerships to develop “best practices” and techniques with key stakeholders for building out a commercially viable nationwide network of zero-emission fueling stations.

Electricity Markets. Power grids are being transformed from simple, fixed energy sources and points of demand to complex webs that feature distributed energy storage, demand response, and power quality factors. “Qualifying facilities” are a special class of small power production facilities and cogeneration facilities created by the Power Utility Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA) of 1978 with the right to sell energy or capacity to a utility and purchase services from utilities while being relieved of certain regulatory burdens. The definition of “qualifying facilities” should be expanded beyond power generation facilities to include households and businesses that provide grid services (e.g., feeding power back to the grid during times of peak energy demand). This would ensure that utilities properly compensate customers if they supply these services, thus allowing individual Americans to participate in electricity markets and spurring the adoption of novel clean-energy technologies.

Geothermal Energy. The Earth’s crust holds more than enough untapped geothermal energy to meet U.S.energy needs. Yet, only 0.4% of U.S. electricity is generated by geothermal energy. There’s a major opportunity to leverage this emerging domestic source for U.S. consumers. Congress should support the Geothermal Earthshot and drive innovation by:

- Establishing a $2 billion risk mitigation fund for geothermal energy development within the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, modeled off of successful programs in Iceland, Costa Rica, and Kenya;

- Establishing a $450 million USDA Rural Development grant program to transition industrial cooling and heating systems in the agricultural sector to geothermal energy

- Expanding the authority of the Leaking Underground Storage Tank (LUST) Trust Fund within the EPA to include the conversion of existing and abandoned oil and gas fields into geothermal wells; and

- Provide $15 million for a national geothermal team within the Bureau of Land Management to develop training materials, standard operating procedures, and provide technical support to district offices to ensure timely review of geothermal power and cooling/heating projects on federal lands.

A policy memo on Empowering the Geothermal Earthshot is forthcoming from FAS.

Appropriations Recommendations

- CHIPS and Science: Research and Development in the Office of Science at the Department of EnergyA number of line items for basic science research at the Department of Energy (DOE) were authorized as part of the CHIPS and Science Act – including materials, physical, chemical, and others. These research programs are central to building a new wave of clean energy technologies and ensuring domestic energy security for decades to come. Subsections of this part of the bill include authorizations for research on nuclear energy, energy storage, carbon sequestration, and other technologies. We recommend that the Office of Science, and especially items in Section 10102 of the CHIPS and Science Act covering Basic Energy Sciences, be funded in alignment with the amounts authorized.

- CHIPS and Science: Funding for the Office of Technology Transitions and prize authorized programs Two additional line items in the CHIPS and Science Act that were authorized but are not yet funded are sections 10713 and 10714. Both authorize prize programs housed in the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) at the Department of Energy–programs that, if funded, could support innovation and commercialization of clean energy technology. Section 10713 authorizes an awards program for clean energy startup incubators, and section 10714 authorizes a new clean energy technology prize competition for universities. Congress should appropriate the authorized funds for these programs.In addition, Congress should appropriate funds authorized in section 10715 of the CHIPS and Science Act. This section authorizes $3 million per year through FY 2027 for coordination capacity at OTT, including to develop metrics for the impact of OTT programs and to engage more effectively with the clean energy ecosystem. Additional capacity for OTT is critical to the office’s success, and to the development of clean energy technologies more broadly.

- IIJA: Funding for the Critical Minerals Mining and Recycling Grant Program in the DOECritical minerals are crucial for clean energy and semiconductor technologies. The U.S. lacks a sufficient domestic supply of critical minerals and is currently overly reliant on foreign critical minerals, which have volatile prices and are often controlled by adversarial countries. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) authorized $100 million from FY 2022 to FY 2024 for the DOE Critical Minerals Mining and Recycling Grant Program to fund pilot projects that process, recycle, or develop critical minerals. This program is not limited to critical minerals for lithium-ion battery production, and has the potential to impact critical minerals used in a variety of clean energy and semiconductor technologies. Congress should appropriate the authorized funds for this program, since it fills the pre-commercialization funding gap for scaling these technologies that is not met by other programs in the IIJA.

- FY 2024: Research and Development in the DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) and the Advanced Research Project Agency for Energy (ARPA-E)

These two offices are key investors in clean energy technologies at different stages of research and commercialization and provide a direct way for the government to scale up American-made energy technologies. To accelerate the energy transition, Congress should provide robust increases for these offices, and at least meet EERE and ARPA-E’s FY 2024 budget requests, such that they can scale up their proven ability of identifying and supporting promising candidates for energy innovation.

118th Congress: Emerging Tech & Competitiveness

Global competition for advanced technology leadership is fierce. China continues to build scholarship capacity across science and engineering disciplines, has surpassed the United States in knowledge- and technology-intensive manufacturing, and is hot on American heels for the global lead in R&D investment. In the U.S., domestic manufacturing jobs have enjoyed a recent surge, but the U.S. trade deficit in high technology stood at nearly $200 billion in 2021, and appears set to far surpass that this year.

The federal government has played an historic role in fostering basic science and the development of critical technologies like the Internet and GPS, and federal investments have helped drive manufacturing and high-tech cluster development for nearly a century. In light of that role, the 118th Congress should act decisively to sustain America’s competitive edge in industries of the future.

R&D Policy. The most important step the new Congress can take is to ensure robust appropriations for the array of science and innovation initiatives authorized in the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. New and ongoing activities in agencies like the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (SC), the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and the Department of Commerce will drive scientific excellence, STEM talent, and industrial competitiveness in key areas like advanced communications, materials, semiconductors, and others.

Congress should also continue to build out Manufacturing USA, a network of highly effective public-private innovation institutes serving defense, energy, life sciences, and other sectors. In addition to CHIPS-authorized funding boosts, the Manufacturing USA network could be enhanced by regional demonstration centers, talent programs to align American worker skills with industry needs, and other steps.

As Congress invests, lawmakers should also seek out opportunities to fund alternative, novel models for research including, for example, focused research organizations (FROs) or institutes for independent scholarship. While the federal science enterprise remains an engine of discovery and progress, new ways of doing science can foster untapped creativity and let scientists and engineers tackle new problems or come up with unforeseen breakthroughs. For instance, the CEO-led FRO model is intended to facilitate mid-scale research projects to produce new public goods (like technologies, techniques, processes, or datasets) that in turn have a catalyzing effect on productivity in the broader science enterprise. Congress should work with agencies to create space and find opportunities to foster such novel approaches.

Congress could also consider legislative reforms to empower national labs to innovate and commercialize cutting-edge technology. For instance, legislation could extend Enhanced Use Lease (EUL) authority to allow for public-private research facilities on surplus federal lands, or create a federally chartered technology transfer organization inspired by similar models at effective universities. Such capabilities would further leverage the labs as engines for regional innovation.

Innovation & Entrepreneurship. The new Congress has the opportunity to invest in critical technologies through new funds and public-private partnerships that drive growth of frontier technology companies. Congress can also invest in the broader ecosystem to make innovation sustainable, expand the geography of innovation, and support equitable access to opportunities. Such investments would continue the momentum that Congress established in 2022.

A major element of this momentum is bipartisan support for the Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs program authorized in Section 10621 of the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act. The new program, intended to catalyze and expand high-tech industry clusters in up-and-coming regions around the United States, was authorized at $10 billion over five years in CHIPS, and received a $500 million down payment in appropriations so far. Now, the 118th Congress should continue and expand upon that support, while more generally continuing to build out place-based and sustainable infrastructure that advances deep-tech and tough-tech industries like the bioeconomy, advanced manufacturing, and clean energy.

In addition, Congress should find ways to support early-stage companies at the technology frontier, through establishing and funding a Frontier Tech consortium or a Deep Tech capital fund to coordinate public investments across government agencies. This would ensure that government funding is used efficiently to spur private investment in early stage frontier tech companies within critical national industrial base areas.

Artificial Intelligence. As AI technologies advance, the government needs to harness them safely and efficiently. Congress should include a National Framework for AI Procurement in the next NDAA to establish a standardized process for vetting AI applications proposed for public use, in line with a 2020 Executive Order on “Promoting the Use of Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence in the Federal Government.” To protect the privacy and security of those using or affected by all AI products, this framework should include a strategy for investing in and deploying privacy-preserving machine learning (PPML).

Space Innovation. While some NASA language was included in CHIPS and Science, space sector innovation didn’t get nearly as much attention as it could have. The 118th should remedy this by placing special focus on investments and policy reform to enhance U.S. ability to innovate in the space sector. The potential opportunity is huge: space is likely to become a trillion-dollar sector before midcentury.

Multiple areas are ripe for action. One is in the area of orbital debris. There are thousands of pieces of space junk now in low-earth orbit – often emerging from defunct satellites or collisions – and these pose a substantial hazard to commercial space operations as well as U.S. national security. To deal with this issue, Congress could work with relevant agencies including the Departments of Defense and Commerce to develop and fund an advanced market commitment for space debris to incentivize solutions via the possibility of investment returns. Congress could also take another run at SPACE Act ideas that were left out of the final Chips and Science text, to codify responsibility for civilian Space Situational Awareness (S.S.A.) with the Department of Commerce and to authorize the creation of one or more centers of excellence for S.S.A.

Congress should also work with the Administration to advance in-space servicing, assembly, and manufacturing (ISAM), an emerging suite of capabilities that offer substantial upside for the future space economy. The White House has already released an ISAM strategy and implementation plan, but substantial action is still needed, and Congress can provide leadership and support in this area. For example, Congress can work with NASA to create an Advanced Space Architectures Program, which would operate under a public-private consortium model to pursue missions that develop new technological capabilities for the U.S. space sector. Congress can also encourage federal agencies and the White House to develop a public roadmap of needs, goals and desired capabilities in the emerging ISAM sector, and to work toward establishing ISAM-specific funding wedges in key agency budget requests to better track related investments for concerted appropriations decisions.

Appropriations Recommendations

- CHIPS and Science: Microelectronics Research (MICRO Act). To drive U.S. science and innovation in microelectronics and semiconductors, Section 10731 authorized the establishment of a network of Microelectronics Science Research Centers at national labs and other institutions, authorized at $25 million in FY 2024, and a broader Department of Energy microelectronics research program at $100 million in FY 2024. These are vital investments in United States technological leadership.

- CHIPS and Science: Entrepreneurial Fellowships. NSF is a vital cog in the non-medical university research ecosystem. In addition to topline funding increases, CHIPS also authorized several smart programs that should receive appropriations within a rising NSF topline overall. One of these is the Entrepreneurial Fellowships program within the newly established technology directorate (Section 10392). The fellowship program, which officially launched last fall, is intended to provide scientists with entrepreneurial training to help shift ideas from lab to market or forge connections between academia, investors, and government. The program is authorized at $125 million over five years, and Congress should ensure robust support.

- As mentioned above, Congress has so far provided $500 million in appropriations for the Regional Technology and Innovation Hub Program, as well as $200 million for the Recompete Pilot Program, a similar place-based program focused specifically on distressed regions and communities. The CHIPS and Science Act authorized these programs at $10 billion and $1 billion respectively, and if past experience is any indication, demand for support from local cluster development teams will far exceed the supply of appropriations provided thus far. To that end, Congress should continue to fund these programs through FY 2024 appropriations: at least by replicating the earlier appropriations figures of $500 million and $200 million, and ideally by getting as close to the authorized amounts as possible. Catalytic investments from the federal government are critical to the early growth of ecosystem efforts, and this program’s continuation would be a continued force in creating greater economic opportunity in communities across the nation.

- Congress should fund the Competitiveness Policy Council (authorized under the Competitiveness Policy Council Act, 15 U.S.C. §4801 et seq.) to provide future recommendations to the president on manufacturing competitiveness. This council should assemble an independent advisory group composed of business, labor, and government leaders to develop policy recommendations that benefit the workforce across their sectors, like President Reagan’s Commission on Industrial Competitiveness.

118th Congress: Resilient Agriculture, Society & Environment

Over the past several years, instability has been a national and global constant. The COVID-19 pandemic upended supply chains and production systems. Floods, hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, and fires have imposed catastrophic consequences and forced people to reconsider where they can safely live. Russia’s war with Ukraine and other geopolitical conflicts have forced countries around the world to scramble for reliable energy sources.

Congress must act decisively to fortify the United States against these and future destabilizing threats. Priorities include revitalizing U.S. agriculture to ensure a dependable, affordable, and diverse food supply; improving disaster preparation and response; and driving development and oversight of critical environmental technologies.

Revitalizing U.S. Agriculture. Every society needs a robust food supply to survive, thrive, and grow. But skyrocketing food prices and agricultural supply-chain disruptions indicate that our nation’s food supply may be on shaky ground. Congress can take measures to rebuild a world-leading U.S. agricultural sector that is sustainable amid evolving external pressures.

A first step is to invest in agricultural innovation and entrepreneurship. The 2018 Farm Bill created the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority (AgARDA) as a driver of transformative progress in agriculture, but failed to equip the institution with a key tool: prize authority. Prizes have proven to be force multipliers for innovation dollars invested by many institutions, including other Advanced Research Projects Agencies (ARPAs). It would be simple for Congress to extend prize authority to AgARDA as well.

Prize authority at AgARDA would be especially powerful if coupled with additional support for agricultural entrepreneurship. Congress should fund the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Small Business Administration (SBA), and the Minority Business Development Administration (MBDA) with $25 million per year for five years to jointly develop a “Ground Up” program to help Americans start small businesses focused on sustainable agriculture.

We must also begin viewing our nation’s soil as a strategic resource. Farmers and ranchers cannot succeed without good places to plant crops and graze livestock. But our nation’s fertile soil is being lost ten times faster than it is being produced. At this rate, many parts of the country will run out of arable land in the next 50 years. Some places—such as the Piedmont region of the eastern United States—already have. States including New Mexico, Illinois, and Nebraska have already introduced or passed legislation to preserve and restore soil health; Congress should follow their example. A comprehensive soil-health bill could, for instance, create bridge-loan projects for farmers transitioning to soil-protective farm practices, expand the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) program to cover such practices, fund USDA Extension offices to provide related technical assistance, and support regenerative agriculture in general.

Finally, Congress should extend funding for two programs that are delivering clear benefits to U.S. food systems. With major food production concentrated in five states, often far from major population centers, the farm-to-table pathway is extraordinarily susceptible to disruptions. The American Rescue Plan Act created the Food Supply Chain Guaranteed Loan Program to help small- and medium-sized enterprises strengthen this pathway, including through “aggregation, processing, manufacturing, storing, transporting, wholesaling or distribution of food.” This program should be continued and resourced going forward. In addition, the Bioproduct Pilot Program studies how materials derived from agricultural commodities can be used for construction and consumer products. This program increases economic activity in rural areas while also lowering commercialization risks associated with bringing bio-based products to market. Congress should extend funding for this program (currently set to expire after FY 2023) for at least $5 million per year through the end of FY 2028.

Improving Disaster Preparation and Response. Every year, Americans lose billions of dollars to natural hazards including hurricanes, wildfires, floods, heat waves, and droughts. We know these disasters will happen…yet only 15% of federal disaster funding is invested to blunt their effects. In particular, current disaster policy and practice lacks incentives for local governments to proactively reduce risks.

Congress can address this failure by amending aspects of the Stafford Act of 1988. In particular, Congress should redefine the disaster threshold in ways that factor in local capacity and ability to recover. Congress should also consider (i) reducing the federal cost share for disaster response, (ii) implementing other incentive models that may induce better local hazard-reduction decisions and improve long-term resilience, and (iii) strengthening existing incentive programs. For example, the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Community Rating System (CRS) could be improved by requiring local governments to take stronger actions to qualify for reduced insurance rates and increasing transparency about how community ratings are calculated.

Disaster management response is not the sole purview of FEMA. For example, the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery (CDBG-DR) program positions the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as a primary disaster-response funder. To ensure efficiency and prevent duplication of effort, Congress must clarify the role of each federal agency involved in disasters.

Congress should also ensure adequate research funding to investigate evidence-based and cost-effective disaster mitigation and response strategies. A useful first step would be doubling the interagency Disaster Resilience Research Grant (DRRG) program, which already supports researchers in groundbreaking modeling, simulations, and solutions development to protect Americans from the most catastrophic consequences.

Driving Development and Oversight of Critical Environmental Technologies. Environmental technologies are critical to ensure energy and resource security. Congress can use market-shaping mechanisms to pull critical environmental technologies, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), forward. Operation Warp Speed demonstrated breakthrough capacity of federally backed advance market commitments (AMCs) to incentivize rapid development and scaling of transformative technologies. Building on this example, Congress should authorize a $1 billion AMC for scalable carbon-removal approaches—providing the large demand signal needed to attract market entrants, and helping to advance a clean all-of-the-above energy portfolio. This approach could then be extended to other environmentally relevant applications, such as building infrastructure to enable next-generation transportation.

Congress must also ensure responsible deployment and reasonable oversight of new environmental technologies. For instance, DOE recently launched an ambitious “Carbon Negative Shot” to foster breakthroughs in carbon dioxide removal (CDR) technology, and is also leading an interagency CDR task force pursuing the advancement of many CDR approaches. But we lack a national carbon-accounting standard and tool to ensure that CDR initiatives are being implemented consistently, honestly, and successfully. Congress should work with the Department of Energy and the Environmental Protection Agency to address this assessment gap.

Similarly, the IRA appropriates over $405 million across federal agencies for activities including “the development of environmental data or information systems.” This could prove a prescient investment to efficiently guide future federal spending on environmental initiatives—but only if steps are taken to ensure that these dollars are not spent on duplicative efforts (for instance, water data are currently collected by 25 federal entities across 57 data platforms and 462 data types). Congress should therefore authorize and direct the creation of a Digital Service for the Planet “with the expertise and mission to coordinate environmental data and technology across agencies”, thus promoting efficiencies in the data enterprise. This centralized service could be established either as a branch of the existing U.S. Digital Service or as a parallel but distinct body.

118th Congress: Infrastructure

America’s infrastructure is in disrepair and our transportation system has failed to keep pace with usage, technology and maintenance needs. As a result, 43% of public roadways are in poor or mediocre condition, roadway fatalities reached nearly 43,000 last year, and logistics and supply chain systems are ill-prepared for the increasing stresses caused by pandemics, international conflicts, and extreme weather events. In addition, our nation’s water supply system is plagued by aged infrastructure such as lead pipes that contribute to irreversible health effects, and vulnerable pipelines leading to water main breaks that lose up to 6 billion gallons of treated water daily. These conditions stem from declining public infrastructure investment, which has decreased as a share of GDP by more than 40% from its high in 1961.

The 118th Congress has an historic opportunity to develop and harness innovative technologies and methods to strengthen our economy, spur job growth, and bolster physical security with an eye toward equitable outcomes for all Americans. Our recommendations for policies that can help us achieve these outcomes are detailed below.

Reducing Transportation and Infrastructure GHGs. Commercial trucks and buses are one of the top contributors of anthropogenic greenhouse gases (GHGs). To help these vehicles transition to cleaner power sources, Congress should facilitate the build-out of a nationwide network of zero-emission fueling stations that would not only help reduce GHGs but also support America’s emerging alternative fuels and vehicles industry, and the job growth that would come with it.

Another significant contributor to GHGs is air travel, specifically small aircraft, the largest source of environmental lead pollution in the United States. Congress should help bolster a more sustainable aviation industry through funding, regulations, and taxes to spur the electrification of regional airports while putting the U.S. back on track to competing with European and Asian companies in the sustainable aviation technology market.

But reducing greenhouse gas emissions of different travel modes is not enough: we need to revolutionize the way we build, in light of the emissions intensity of materials such as steel and concrete. To support a “Steel Shot” at DOE, Congress should provide funding for a Clean Energy Manufacturing USA Institute focused on clean steel, as well as funding and authorities for federal investment in commercial-scale solutions.

Harnessing the Benefits of Smart-City Technologies While Mitigating Risks. Smart-city technologies – such as autonomous vehicles, smart grids, and internet-connected sensors – have the opportunity to deliver a better quality of life for communities by harnessing the power of data and digital infrastructure. However, they are not being used to their full potential. Congress should support more widespread adoption of smart-city technologies through funding for a new Smart Community Prize Competition, increased funding for community development programs such as HUD’s ConnectHome pilot program, planning grants, and resources for regional innovation ecosystems, amongst others.

But communities should not invest in or adopt smart-city technologies without consideration for individual protections and privacy. To that end, Congress should fund the development of technologies and processes that have civic protections embedded at their core.

Putting AVs and CVs at the Forefront of Advancing Societal Benefits and Equity. The widespread adoption of Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) and Connected Vehicles (CVs) can revolutionize the way we travel and accelerate progress on a number of outcomes, including safety, GHG emissions, and travel times and costs. There are several ways Congress can play a role in spurring the AV and CV markets toward realizing these outcomes.

On AVs, Congress can create an Evaluation Innovation Engine at the Department of Transportation (USDOT) funded at $72 million annually to identify priority AV metrics and spur innovative technologies and strategies that would achieve them. Congress can also support AV-5G connections, critical for AV integration with the built environment, by funding a program to establish transportation infrastructure pilot zones; funding a National Connected AV Research Consortium; funding a research initiative at NSF focused on safety; and funding a new U.S. Corps of Engineers and Computer Scientists for Technology.

On CVs, Congress can help stakeholders at the federal, state, and local level realize their benefits and work towards a common strategy by creating a National Task Force on Connected Vehicles.

Supporting Communities of Opportunity. In support of a national equitable transit-oriented development (TOD) program that addresses widespread demand for affordable housing and walkable communities, Congress should pass legislation that extends the use of Railroad Rehabilitation Improvement Financing (RRIF) funds for TOD initiatives; increases RRIF’s loan authorization to $50B, creates new funding and tax incentives to support TOD initiatives; and expands USDOT’s federal credit assistance programs, among other measures.

Appropriations Recommendations

- ARPA-Infrastructure (ARPA-I). ARPA-I, authorized in the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, presents a generational opportunity for USDOT to think big and take on monumental challenges across transportation and infrastructure that are ripe for breakthrough innovation. The office has received funding for initial planning and staffing but still requires considerable appropriations to begin building out an initial set of programs around high-priority infrastructure problems. Our recommendation is $500 million in appropriated funds for FY 2024 to scale ARPA-I.

- Secretary of Transportation Open Research Initiative Pilot Program. We recommend that the authorized pilot programs in Section 25013 of the IIJA be appropriated $50 million in funding for FY 2024, as authorized, to spur advanced transportation research.

- Clean Energy Manufacturing Institute for Clean Steel. We recommend that Congress appropriate $15 million in FY 2024 (a similar funding magnitude as existing institutes) for a Clean Energy Manufacturing Institute focused specifically on clean steel.

- Clean Steel and Aluminum Earthshot Appropriations. The budget request for FY 2023 included $204 million for the Department of Energy’s Energy Earthshots Initiative. We recommend this program receive robust continued appropriations in FY 2024, including $15 million to include an earthshot for clean steel and aluminum.

Congress May Miss CHIPS And Science Research Targets by Billions This December

Earlier this year Congress passed the CHIPS And Science Act: a once-in-a-generation piece of legislation to secure U.S. semiconductor manufacturing, enhance U.S. science investment, and foster the next generation of STEM talent.

But at the core of that legislation are aggressive spending targets for the National Science Foundation (NSF), the Department of Energy Office of Science (DOE SC), and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). These targets tee all of these agencies up for sustained long-term growth, but Congress has to provide actual dollars to make it happen. Now, amid a looming funding deadline December 16, Congress is running the risk of falling substantially short of its own bipartisan aspirations.

To tally up the current shortfalls between current appropriations and aspirational CHIPS targets, FAS has produced a short report breaking down key programs and provisions by agency. Read below for a summary of major takeaways, or download now for the full report.

What is CHIPS and Science?

The CHIPS And Science Act has some of its original roots in calls almost three years ago to create a new technology directorate at NSF, ramp up federal science funding, and create regional tech hubs around the country. These investments are still at the final law’s core, along with policies to achieve additional goals like achieving energy security and fostering STEM talent. Collective program changes in the law offer the potential to boost domestic manufacturing, tackle supply-chain vulnerabilities, and power the workforce of the future in emerging industries.

A key aspect of CHIPS And Science is the inclusion in Section 10387 of a list of 10 critical technology areas (including AI, quantum science, robotics, biotech, and others) and five societal challenge areas (like national security, industrial productivity, and climate change). These priorities are intended to guide investments by the new NSF technology directorate, and inform other activities like long-term strategy development.

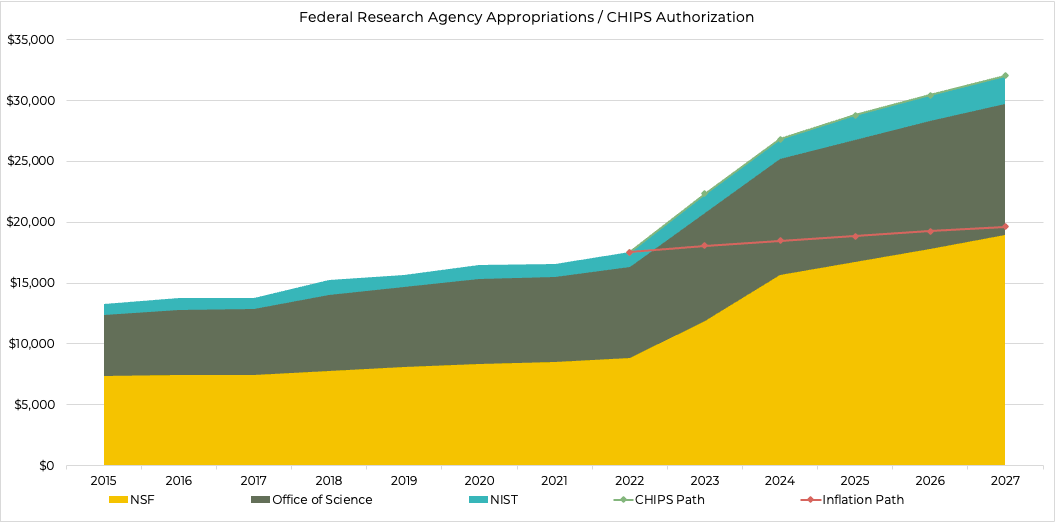

Again, a key component of CHIPS And Science is rising spending targets, or authorizations, from the current fiscal year (FY 2023) through FY 2027. In the first year, NSF, DOE SC, and NIST are slated for a 28% year-over-year increase to kick off a long-term rise (see graph below). But that’s just a target, and not a guarantee that actual funding will arrive.

Enter Appropriations

These agencies are funded through annual appropriations bills, typically marked up by Congress in summer and finalized each fall. To date, the House has completed work on six out of twelve annual spending bills, while Senate Democrats have released a round of proposals that have yet to receive necessary bipartisan action.

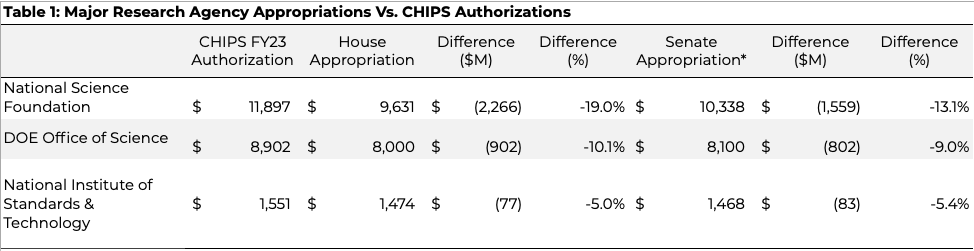

How are things shaping up for the three research agencies included in CHIPS? While FY 2023 appropriations for the three agencies would provide at least moderate year-over-year boosts, they’re also substantially short of the aspirational targets set thus far. In the aggregate, as we show in our report, appropriations for the NSF, DOE SC, and NIST are currently $2.4 billion or 11% short of the bipartisan CHIPS targets in the Senate, and $3.2 billion or 15% short in the House, as of November 2022.

Legislators will still have a chance to make up this ground in conference talks for the final omnibus, which should arrive very soon. Science advocates, including universities, companies, and science societies, have been at work in recent months calling for robust appropriations. Robust funding closer to the CHIPS targets will ultimately put U.S. scientists and companies in a better position to compete and win in fields with emerging technology on the global stage.

Agency Specifics

The appropriations shortfalls are fairly broad-based for NSF and DOE SC, while more narrow for NIST. Here’s a quick recap of the state of appropriations for each; for more, see the full report.

National Science Foundation: NSF forms a cornerstone of federal R&D and is the leading funder for non-medical research at U.S Universities. It’s particularly prominent in research and STEM education in disciplines like chemistry that undergird excellence in the technology priorities identified in Section 10387.

Currently, House and Senate appropriations are $2.3 billion and $1.6 billion short of the CHIPS And Science authorizations, respectively – shortfalls that some experts warn could sink U.S. competitive ambitions. This includes a shortfall of at least $738 million for the primary NSF research account, funding for which is important for ensuring NSF has sufficient resources to boost existing programs and allow the new technology directorate to get off to the running start Congress intended. In addition, STEM education appropriations are $700 million shy of CHIPS in the House and $623 million in the Senate. A few of many areas that could do with a top-up include:

- Mid-Scale Infrastructure. Appropriators have allocated some funding, but CHIPS targeted an additional unfunded $55 million for university infrastructure projects with a cost between $20 million and $100 million, representing an underserved subset of science infrastructure investment. The existing program is significantly oversubscribed.

- Entrepreneurial Fellowships. The new directorate was directed to establish a fellowship program that provides scientists with entrepreneurial training (not unlike this Day One Project proposal), authorized at $125 million over five years. Funding would award fellowships to scientists and engineers with promising ideas capable of forging connections between academia, industry, government, and other end-users.

- Robert Noyce Teacher Fellowships. The fellowship provides stipends, scholarships, and programmatic support to prepare and recruit highly skilled STEM professionals to become K-12 teachers in high-need districts, and is at least $60 million below target in both chambers.

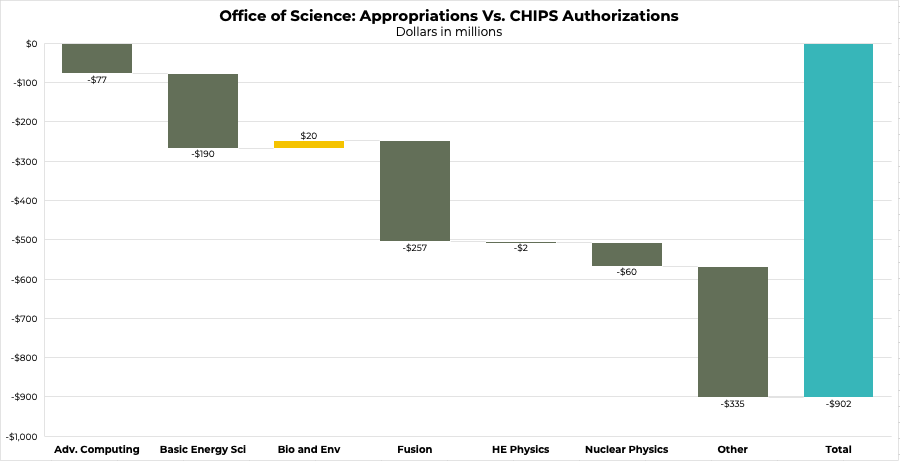

Office of Science: DOE SC is the largest funder of the physical sciences, and pursues several crosscutting research initiatives directly aligned with CHIPS technology priorities, including in microelectronics, quantum science, critical materials, and other areas. This work is spread over the Office’s six major research programs, appropriations for most of which are well below the CHIPS targets (see graph above). Overall, House and Senate appropriations are currently $902 million and $802 million short of the authorizations established in CHIPS, respectively.

- Fusion science funding is $257 million below CHIPS at the House level and $282 million below in the Senate. Among CHIPS priorities are an authorization of $35 million in FY 2023 for designs and technology roadmaps for a pilot fusion plant. It also authorizes a research program and innovation center in high-performance computing for fusion.

- The Basic Energy Sciences program is short of $190 million at the House and $145 million in the Senate. The largest research program supports fundamental science disciplines for several CHIPS And Science technology areas. Among other things the law authorized research in energy storage ($120 million authorized in FY 2023) and $50 million per year for carbon materials and storage research in coal-rich U.S. regions.

- Advanced Scientific Computing Research is at least $50 million below CHIPS targets in appropriations so far. CHIPS authorized a program in quantum network infrastructure at $100 million in FY 2023 and a program to expand quantum hardware and research cloud access at $30 million in FY 2023.

NIST. The agency’s R&D activities cover several CHIPS And Science technology priorities including cybersecurity, advanced communications, AI, quantum science, and biotechnology. NIST also boasts a wide-ranging system of manufacturing extension centers in all 50 states and Puerto Rico, which help thousands of U.S. manufacturers grow and innovate every year. Topline NIST appropriations to date have gotten reasonably close to CHIPS targets in the House, and far exceed the target in the Senate proposal, though this is primarily driven by construction project earmarks. Still, appropriations so far for NIST’s primary lab research account are not far from CHIPS And Science targets.

On the other hand, NIST manufacturing programs lag well behind the CHIPS targets, including shortfalls in appropriations for the Hollings Manufacturing Extension Partnership of $63 million in the House and $75 million in the Senate; and a $79 million shortfall in the House for Manufacturing USA funding.

Next Steps

For Congress to move from the current status of appropriations to a final deal (hopefully) closer to CHIPS, a few things have to happen. First, leadership has to agree on an overall spending topline or what’s known as a “302(a)” allocation, with robust increases for nondefense spending in particular: all three of NSF, DOE SC, and NIST are funded via the nondefense budget, and a good nondefense number is necessary to create room for budget boosts to fulfill the CHIPS vision.

Second, Congress will have to provide adequate increases for CHIPS-crucial spending bills – specifically, the Commerce-Justice-Science bill (for NSF and NIST, as well as other CHIPS priorities like the tech hubs) and the Energy & Water bill (for DOE programs), through are what is known as “302(b)” allocations. With competing interests and priorities making claims on taxpayer dollars in every bill, its incumbent for appropriations leaders to ensure spending bills are big enough to provide room for CHIPS competitiveness growth.

Finally, legislators and staff will have to make final decisions on agency and programmatic spending levels. There’s a golden opportunity to top up those key programs for U.S. technology leadership authorized in CHIPS – but the clock is ticking.

Unlocking Federal Grant Data To Inform Evidence-Based Science Funding

Summary

Federal science-funding agencies spend tens of billions of dollars each year on extramural research. There is growing concern that this funding may be inefficiently awarded (e.g., by under-allocating grants to early-career researchers or to high-risk, high-reward projects). But because there is a dearth of empirical evidence on best practices for funding research, much of this concern is anecdotal or speculative at best.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF), as the two largest funders of basic science in the United States, should therefore develop a platform to provide researchers with structured access to historical federal data on grant review, scoring, and funding. This action would build on momentum from both the legislative and executive branches surrounding evidence-based policymaking, as well as on ample support from the research community. And though grantmaking data are often sensitive, there are numerous successful models from other sectors for sharing sensitive data responsibly. Applying these models to grantmaking data would strengthen the incorporation of evidence into grantmaking policy while also guiding future research (such as larger-scale randomized controlled trials) on efficient science funding.

Challenge and Opportunity

The NIH and NSF together disburse tens of billions of dollars each year in the form of competitive research grants. At a high level, the funding process typically works like this: researchers submit detailed proposals for scientific studies, often to particular program areas or topics that have designated funding. Then, expert panels assembled by the funding agency read and score the proposals. These scores are used to decide which proposals will or will not receive funding. (The FAQ provides more details on how the NIH and NSF review competitive research grants.)

A growing number of scholars have advocated for reforming this process to address perceived inefficiencies and biases. Citing evidence that the NIH has become increasingly incremental in its funding decisions, for instance, commentators have called on federal funding agencies to explicitly fund riskier science. These calls grew louder following the success of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19, a technology that struggled for years to receive federal funding due to its high-risk profile.

Others are concerned that the average NIH grant-winner has become too old, especially in light of research suggesting that some scientists do their best work before turning 40. Still others lament the “crippling demands” that grant applications exert on scientists’ time, and argue that a better approach could be to replace or supplement conventional peer-review evaluations with lottery-based mechanisms.

These hypotheses are all reasonable and thought-provoking. Yet there exists surprisingly little empirical evidence to support these theories. If we want to effectively reimagine—or even just tweak—the way the United States funds science, we need better data on how well various funding policies work.

Academics and policymakers interested in the science of science have rightly called for increased experimentation with grantmaking policies in order to build this evidence base. But, realistically, such experiments would likely need to be conducted hand-in-hand with the institutions that fund and support science, investigating how changes in policies and practices shape outcomes. While there is progress in such experimentation becoming a reality, the knowledge gap about how best to support science would ideally be filled sooner rather than later.

Fortunately, we need not wait that long for new insights. The NIH and NSF have a powerful resource at their disposal: decades of historical data on grant proposals, scores, funding status, and eventual research outcomes. These data hold immense value for those investigating the comparative benefits of various science-funding strategies. Indeed, these data have already supported excellent and policy-relevant research. Examples include Ginther et. al (2011) which studies how race and ethnicity affect the probability of receiving an NIH award, and Myers (2020), which studies whether scientists are willing to change the direction of their research in response to increased resources. And there is potential for more. While randomized control trials (RCTs) remain the gold standard for assessing causal inference, economists have for decades been developing methods for drawing causal conclusions from observational data. Applying these methods to federal grantmaking data could quickly and cheaply yield evidence-based recommendations for optimizing federal science funding.

Opening up federal grantmaking data by providing a structured and streamlined access protocol would increase the supply of valuable studies such as those cited above. It would also build on growing governmental interest in evidence-based policymaking. Since its first week in office, the Biden-Harris administration has emphasized the importance of ensuring that “policy and program decisions are informed by the best-available facts, data and research-backed information.” Landmark guidance issued in August 2022 by the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy directs agencies to ensure that federally funded research—and underlying research data—are freely available to the public (i.e., not paywalled) at the time of publication.

On the legislative side, the 2018 Foundations for Evidence-based Policymaking Act (popularly known as the Evidence Act) calls on federal agencies to develop a “systematic plan for identifying and addressing policy questions” relevant to their missions. The Evidence Act specifies that the general public and researchers should be included in developing these plans. The Evidence Act also calls on agencies to “engage the public in using public data assets [and] providing the public with the opportunity to request specific data assets to be prioritized for disclosure.” The recently proposed Secure Research Data Network Act calls for building exactly the type of infrastructure that would be necessary to share federal grantmaking data in a secure and structured way.

Plan of Action

There is clearly appetite to expand access to and use of federally held evidence assets. Below, we recommend four actions for unlocking the insights contained in NIH- and NSF-held grantmaking data—and applying those insights to improve how federal agencies fund science.

Recommendation 1. Review legal and regulatory frameworks applicable to federally held grantmaking data.

The White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB)’s Evidence Team, working with the NIH’s Office of Data Science Strategy and the NSF’s Evaluation and Assessment Capability, should review existing statutory and regulatory frameworks to see whether there are any legal obstacles to sharing federal grantmaking data. If the review team finds that the NIH and NSF face significant legal constraints when it comes to sharing these data, then the White House should work with Congress to amend prevailing law. Otherwise, OMB—in a possible joint capacity with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)—should issue a memo clarifying that agencies are generally permitted to share federal grantmaking data in a secure, structured way, and stating any categorical exceptions.

Recommendation 2. Build the infrastructure to provide external stakeholders with secure, structured access to federally held grantmaking data for research.

Federal grantmaking data are inherently sensitive, containing information that could jeopardize personal privacy or compromise the integrity of review processes. But even sensitive data can be responsibly shared. The NIH has previously shared historical grantmaking data with some researchers, but the next step is for the NIH and NSF to develop a system that enables broader and easier researcher access. Other federal agencies have developed strategies for handling highly sensitive data in a systematic fashion, which can provide helpful precedent and lessons. Examples include:

- The U.S. Census Bureau (USCB)’s Longitudinal Employer-Household Data. These data link individual workers to their respective firms, and provide information on salary, job characteristics, and worker and firm location. Approved researchers have relied on these data to better understand labor-market trends.

- The Department of Transportation (DOT)’s Secure Data Commons. The Secure Data Commons allows third-party firms (such as Uber, Lyft, and Waze) to provide individual-level mobility data on trips taken. Approved researchers have used these data to understand mobility patterns in cities.

In both cases, the data in question are available to external researchers contingent on agency approval of a research request that clearly explains the purpose of a proposed study, why the requested data are needed, and how those data will be managed. Federal agencies managing access to sensitive data have also implemented additional security and privacy-preserving measures, such as:

- Only allowing researchers to access data via a remote server, or in some cases, inside a Federal Statistical Research Data Center. In other words, the data are never copied onto a researcher’s personal computer.

- Replacing any personal identifiers with random number identifiers once any data merges that require personal identifiers are complete.

- Reviewing any tables or figures prior to circulating or publishing results, to ensure that all results are appropriately aggregated and that no individual-level information can be inferred.

Building on these precedents, the NIH and NSF should (ideally jointly) develop secure repositories to house grantmaking data. This action aligns closely with recommendations from the U.S. Commission on Evidence-Based Policymaking, as well as with the above-referenced Secure Research Data Network Act (SRDNA). Both the Commission recommendations and the SRDNA advocate for secure ways to share data between agencies. Creating one or more repositories for federal grantmaking data would be an action that is simultaneously narrower and broader in scope (narrower in terms of the types of data included, broader in terms of the parties eligible for access). As such, this action could be considered either a precursor to or an expansion of the SRDNA, and could be logically pursued alongside SRDNA passage.

Once a secure repository is created, the NIH and NSF should (again, ideally jointly) develop protocols for researchers seeking access. These protocols should clearly specify who is eligible to submit a data-access request, the types of requests that are likely to be granted, and technical capabilities that the requester will need in order to access and use the data. Data requests should be evaluated by a small committee at the NIH and/or NSF (depending on the precise data being requested). In reviewing the requests, the committee should consider questions such as:

- How important and policy-relevant is the question that the researcher is seeking to answer? If policymakers knew the answer, what would they do with that information? Would it inform policy in a meaningful way?

- How well can the researcher answer the question using the data they are requesting? Can they establish a clear causal relationship? Would we be comfortable relying on their conclusions to inform policy?

Finally, NIH and NSF should consider including right-to-review clauses in agreements governing sharing of grantmaking data. Such clauses are typical when using personally identifiable data, as they give the data provider (here, the NIH and NSF) the chance to ensure that all data presented in the final research product has been properly aggregated and no individuals are identifiable. The Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board can provide some helpful guidance for NIH and NSF to follow on this front.

Recommendation 3. Encourage researchers to utilize these newly available data, and draw on the resulting research to inform possible improvements to grant funding.

The NIH and NSF frequently face questions and trade-offs when deciding if and how to change existing grantmaking processes. Examples include:

- How can we identify promising early-career researchers if they have less of a track record? What signals should we look for?

- Should we cap the amount of federal funding that individual scientists can receive, or should we let star researchers take on more grants? In general, is it better to spread funding across more researchers or concentrate it among star researchers?

- Is it better to let new grantmaking agencies operate independently, or to embed them within larger, existing agencies?

Typically, these agencies have very little academic or empirical evidence to draw on for answers. A large part of the problem has been the lack of access to data that researchers need to conduct relevant studies. Expanding access, per Recommendations 1 and 2 above, is a necessary part of but not a sufficient solution. Agencies must also invest in attracting researchers to use the data in a socially useful way.

Broadly advertising the new data will be critical. Announcing a new request for proposals (RFP) through the NIH and/or the NSF for projects explicitly using the data could also help. These RFPs could guide researchers toward the highest-impact and most policy-relevant questions, such as those above. The NSF’s “Science of Science: Discovery, Communication and Impact” program would be a natural fit to take the lead on encouraging researchers to use these data.

The goal is to create funding opportunities and programs that give academics clarity on the key issues and questions that federal grantmaking agencies need guidance on, and in turn the evidence academics build should help inform grantmaking policy.

Conclusion

Basic science is a critical input into innovation, which in turn fuels economic growth, health, prosperity, and national security. The NIH and NSF were founded with these critical missions in mind. To fully realize their missions, the NIH and NSF must understand how to maximize scientific return on federal research spending. And to help, researchers need to be able to analyze federal grantmaking data. Thoughtfully expanding access to this key evidence resource is a straightforward, low-cost way to grow the efficiency—and hence impact—of our federally backed national scientific enterprise.

For an excellent discussion of this question, see Li (2017). Briefly, the NIH is organized around 27 “Institutes or Centers” (ICs) which typically correspond to disease areas or body systems. ICs have budgets each year that are set by Congress. Research proposals are first evaluated by around 180 different “study sections”, which are committees organized by scientific areas or methods. After being evaluated by the study sections, proposals are returned to their respective ICs. The highest-scoring proposals in each IC are funded, up to budget limits.

Research proposals are typically submitted in response to announced funding opportunities, which are organized around different programs (topics). Each proposal is sent by the Program Officer to at least three independent reviewers who do not work at the NSF. These reviewers judge the proposal on its Intellectual Merit and Broader Impacts. The Program Officer then uses the independent reviews to make a funding recommendation to the Division Director, who makes the final award/decline decision. More details can be found on the NSF’s webpage.

The NIH and NSF both provide data on approved proposals. These data can be found on the RePORTER site for the NIH and award search site for the NSF. However, these data do not provide any information on the rejected applications, nor do they provide information on the underlying scores of approved proposals.

Congress Extends Small Business Innovation Program for Three Years. Now What?

The collective sigh of relief you heard last week came from small businesses and university innovators across the country who had been holding their breath for passage of the SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022. The bill, which was finally adopted by Congress on Thursday and signed into law by President Biden on Friday, ensures continuity for a 40-year-old R&D grant program that invests about $4 billion a year in 4,000 small businesses pursuing innovative research across all fields of science, technology, and medicine. The program had been facing termination at the end of September, with its extension held up due to concerns over non-competitiveness and risks of foreign influence. Last week’s extension bill, which Congress slid just under the deadline, includes key provisions to address those concerns, and reauthorizes the program for three years until September 30th, 2025.

What is SBIR / STTR?

The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs fund American small businesses engaging in dual-use research and development (R&D). Often referred to as “America’s Seed Fund,” their goals are to stimulate innovations that can address federal agencies’ missions and be commercialized in the private sector. They also seek to promote the participation of women and socially or economically disadvantaged persons in entrepreneurship. The program is a source of non-dilutive funding for small businesses, meaning they do not give up equity in exchange for SBIR funds.

SBIR has its roots in 1970s-era concerns that the United States was losing its technological and scientific edge in the global economy — concerns that are all too familiar today. Piloted at the National Sciences Foundation (NSF) and formally established in 1982, the program now includes 11 federal agencies. The five largest of those agencies (Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Department of Health and Human Services, NASA, and NSF) also fund STTR awards which require participation of a nonprofit research institution.

Each agency decides which research topics to fund, and awards funding in two sequential phases. For example, the Department of Defense calls for topics that meet warfighter mission needs, while the National Institutes of Health (NIH) funds research related to novel cancer treatments, Alzheimer’s drugs, and more. The program’s success stories include household names like Qualcomm, Symantec, iRobot, and 23andme.

More broadly, the economic impact of both programs is massive. One frequently cited Department of Defense study claims that the two programs generated a 22-1 return on investment for the public between 1995 and 2018, with a total national economic impact of $347 billion and 1.5 million jobs created.

Key Hold Ups to Extension

In light of the looming authorization lapse, Congress discussed an extension of SBIR for months, but negotiations foundered over a few key issues. One of these was disagreement over what to do about the minority of firms that receive an outsized share of awards, which some pejoratively refer to as “SBIR mills.” Most firms that participate in SBIR receive only one or two awards in their lifetime. But the award distribution has a major skew: for instance, a recent analysis finds that just 10 firms, accounting for 0.7% of all SBIR recipient firms, have received 6.5% of all SBIR awards since 2000.

Some argue that this skew is evidence of large, well-entrenched companies gaming a system intended to drive innovation from smaller businesses and new entrants. On the other hand, there is some evidence to suggest these firms do deliver value in the form of scientific publications, inventions, follow-on funding, and commercialization, and may also serve as venues for talented scientists and engineers who go on to become founders.

The other major issue is that of foreign influence. Amid general Congressional concerns over foreign involvement in the U.S. scientific enterprise, an oft-cited 2021 report from the Defense Department allegedly found troubling indications of Chinese state involvement in SBIR funding recipients. These findings prompted cautious backlash on the part of lawmakers.

Summary of Major Bill Sections

While Congress kept it until the final hours, the SBIR and STTR Extension Act of 2022 was ultimately approved by overwhelming majorities. The core of the act is a three-year extension of the overall program and several SBIR pilot programs through September 2025. The reauthorization also includes several new provisions to address past criticism and points of concern. Let’s unpack these below.

New requirements

Foreign Risk Management: The extension mandates each agency pursue diligence to assess the risk of foreign involvement with and ties to SBIR-funded small businesses. Business applicants will be required to disclose business relationships and financial arrangements before receiving an award, under threat of an agency funding clawback should a firm misrepresent itself. Relatedly, the bill requires multiple agencies to issue reports on foreign risks.

In practice, it is unclear how much of a burden the new financial reporting requirement will be for small businesses. Some startups, particularly first time awardees or those with foreign investors, could face challenges properly reporting this information. Others may be dissuaded from applying to SBIR solicitations entirely. It’s also unclear what mechanism would apply for managing foreign risk after a small business has received funding and completed the planned scope of work. To mitigate this, the SBA should be clear in its guidance to companies on what they need to disclose.

Open Topics: The extension mandates that Defense Department components each issue at least one ‘open topic’ announcement per year. Open topics are technology-agnostic solicitations to which any small business may respond with their proposed innovation. The Air Force pioneered the open topic model at DoD in 2018, and according to a 2022 GAO report, it proved successful in attracting first-time award winners (43% of awardees were net new) and cutting time to award (108-126 days faster on average). This new requirement also requests annual reports comparing open and conventional topic awards across a host of metrics.

Increased Minimum Performance Standards for Experienced Firms: The extension outlines higher performance standards for experienced firms regarding both Phase I and Phase II awards. They’re also known as “multiple award winners.” This is an effort to cut down on SBIR ‘mills’, but whether it will achieve this end or not is questionable. The number of companies these restrictions apply to is small, and the minimum penalty for not meeting the standard is a restriction to only 20 Phase I awards at each agency in the next year. The impact of these new restrictions is an open question that the next three years will hopefully answer. Finally, the new standards remove patents as a way to meet performance standards.

Here’s a breakdown of the new standards:

Pilot programs

The reauthorization of pilot programs–and the inclusion of new efforts–provides the SBA and policymakers an opportunity to learn more from different agency efforts. They’ll get three more years worth of data to weigh whether or not to permanently weave these pilots into the fabric of the overall program. Brief overview of the pilots are included below:

- Phase Flexibility Pilot: NIH, DoD, and ED can issue direct to Phase II awards to fund projects that might be too advanced for a Phase I.

- Civilian Agency Commercialization Readiness Pilot: Civilian agencies can use 10% of their SBIR funding for technical assistance not usually covered by Phase II awards. NIH uses it to give Phase II awardees resources for slow moving processes like Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, development of an intellectual property (IP) strategy, or planning for clinical trials.

- Pilot to Accelerate DoD SBIR/STTR Awards: DoD required to simplify their award process and issue awards in about 90 days from start to finish.