Biden Administration Decides To Build A New Nuclear Bomb to Get Rid Of An Old Bomb

A B-2 bomber drops an unarmed B61-12 bomb in a trial. The planned B61-13, which seems intended to persuade Congress to allow retirement of the B83-1, would look the same and arm the new B-21 bomber.

[UPDATED] The Biden administration has decided to add a new nuclear gravity bomb to the US arsenal. The bomb will be known as the B61-13.

The decision to add the B61-13 comes shortly after another new nuclear bomb – the B61-12 – began full-scale production last year and is currently entering the nuclear stockpile. The administration stated that it would not increase the number of weapons in the arsenal and that any B61-13s would come at the expense of the long-planned B61-12.

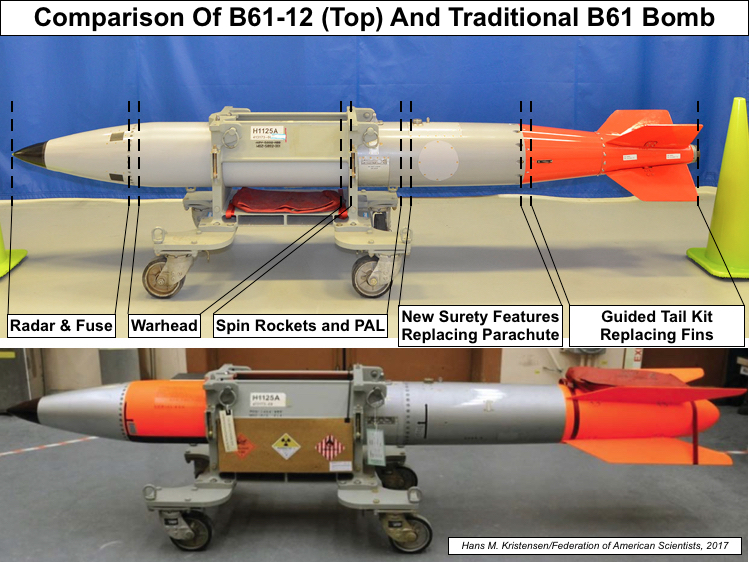

According to defense officials, the B61-13 will use the warhead from the B61-7 but will be modified with new safety and use-control features as well as a guided tail kit (like the B61-12) to increase the bomb’s accuracy compared with the B61-7.

Although officials assured us that the B61-13 plan is not due to new developments in the target set, the press material from the Pentagon is more direct: B61-13 will “provides us with additional flexibility” by “providing the President with additional options against certain harder and large-area military targets.”

Like the B61-7, the B61-13 will be designed for delivery by strategic bombers: the future B-21 and, until it is retired, possibly also the B-2. It is not intended for delivery by dual-capable fighters. This decision to build the B61-13, however, appears to have less to do with a military need than striking a political deal to get rid of the last megaton-yield weapon in the US arsenal: the B83-1. This weapon was originally slated for retirement under President Obama until it was resurrected by the Trump administration; it has since become a focal point of the battle between the Biden administration, which wants to retire it, and congressional hardliners, who want to keep it.

Change Of Plan

The case for the B61-13 is strange. For the past 13 years, the sales pitch for the expensive B61-12 has been that it would replace all other nuclear gravity bombs. By re-using the B61-4 warhead, adding new safety and use-control features, and increasing accuracy with a guided tail kit, the agencies initially argued that it would be a consolidation of four existing types (B61-3/4/7/10) into a single type of gravity bomb.

Military officials have explained countless times that the B61-12 would be able to cover all gravity missions with less collateral damage than large-yield bombs. Increasing the bomb’s accuracy was the key reason why the tail kit was added, replacing the older drag parachute system of the older weapons.

By reducing the number of bomb types, the administration argued, it would be possible to reduce the total number of gravity bombs in the arsenal by 50 percent and save a substantial amount of money. Moreover, by using a warhead for the B61-12 with the least amount of fissile material, the proliferation risk from theft would be reduced, so the argument went. When the B61-10 was retired in 2016, the pitch obviously changed to consolidating three bomb types, rather than four, into one. But the Obama administration also wanted to use it to replace the ultra-high yield B83-1 and eventually the B61-11 earth-penetrator.

The Biden administration appears to have decided to build the new B61-13 nuclear bomb to persuade hardliners to get rid of the old B83-1 bomb.

The Trump administration had different interests, however, and its Nuclear Posture Review decided to retain the B83-1 (for reasons that remain unclear, and appear to have as much to do with undoing any decisions from the previous administration and little to do with military requirements or target sets) and leave the fate of the B61-11 unanswered.

When the Biden administration took over, its Nuclear Posture Review decided to proceed with retirement of the B83-1 but did not say anything about the B61-11. The Republican-controlled House did not agree and have used the years since to solicit hardline views that the B83-1 is somehow still needed.

Privately, however, Air Force and NNSA official disagreed. A high-yield gravity bomb is no longer needed and maintaining the B83-1 would cost a lot of money that could be better used elsewhere. Moreover, the NNSA production schedule is packed and adding a B83-1 life-extension program could jeopardize much more important programs. Although the B61-13 will add stress to this backlog, it will not increase the NNSA’s planned plutonium pit production schedule.

B61-13 Characteristics

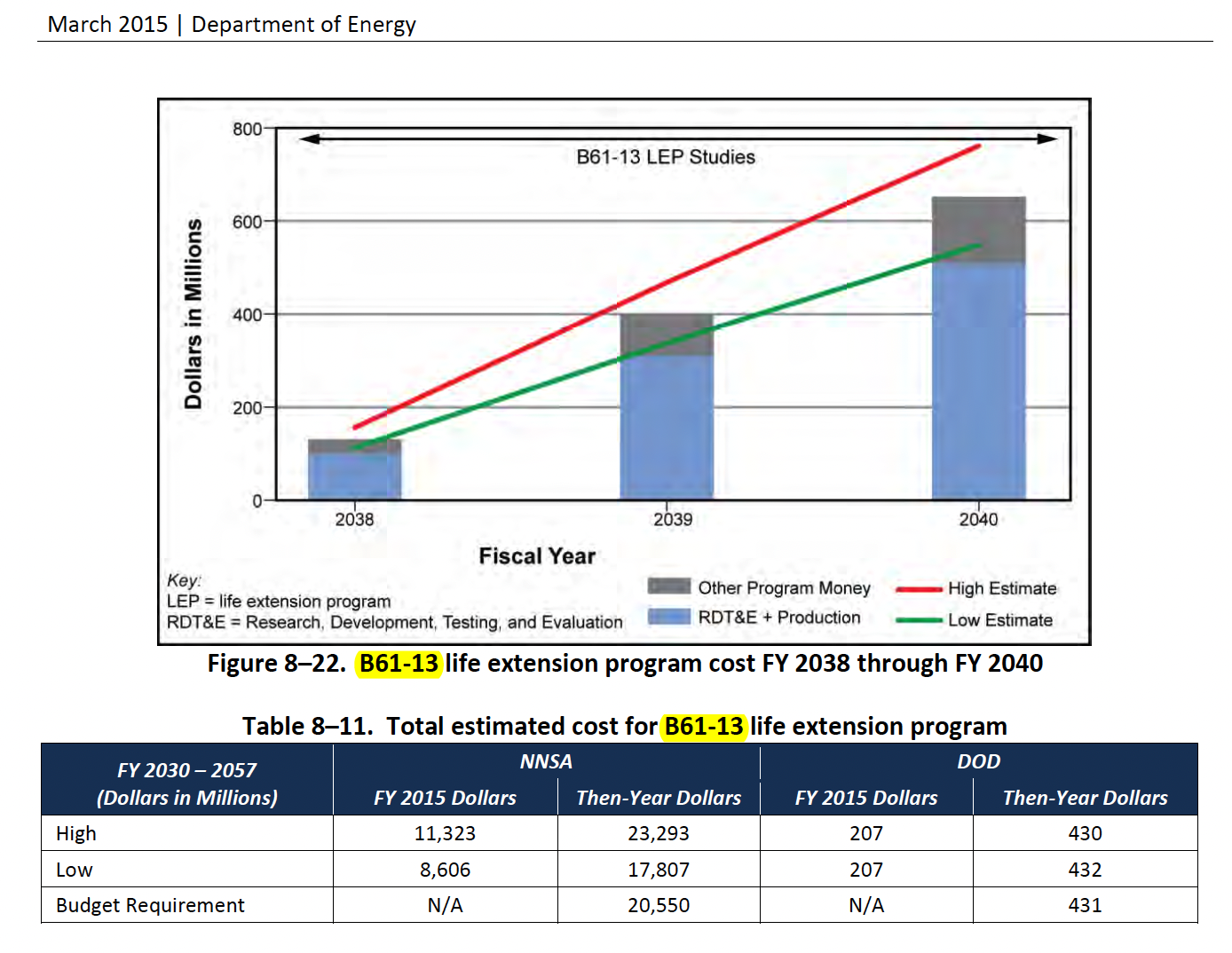

Confusingly, the name B61-13 has already been used for another nuclear weapon: the future bomb intended to replace the B61-12 in the late-2030s and 2040s. That weapon was first described in NNSA’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan in 2015 (see images below).

The B61-13 designation was previously given to another future nuclear bomb back in 2015.

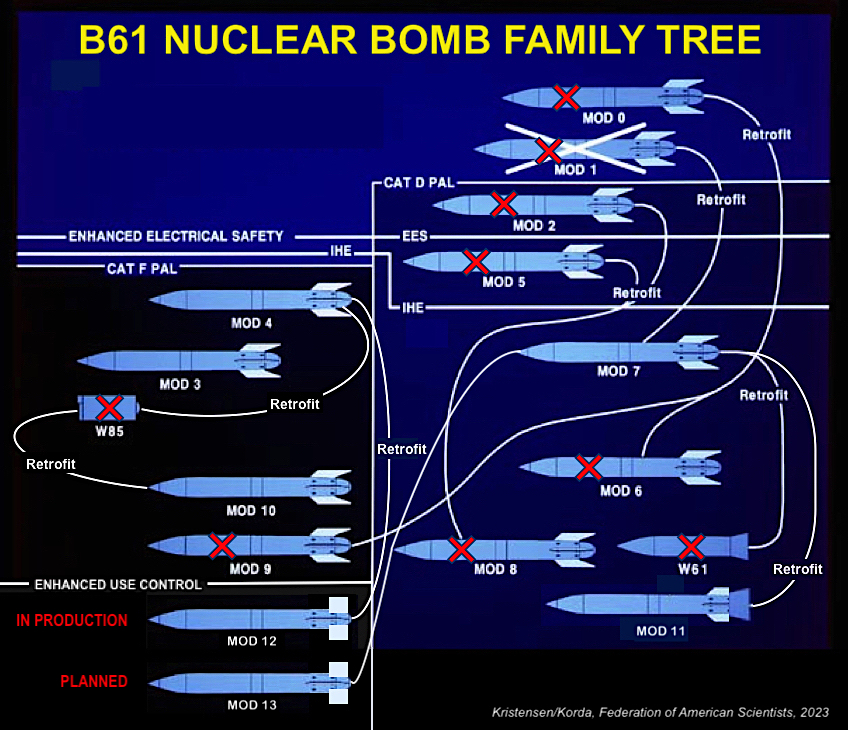

The new B61-13 bomb will be the 13th modification of the B61 warhead design (see image below). These modifications have varied in physical appearances, yields, safety and use-control features, and delivery platforms. Five of these modifications remain in the stockpile (B61-3/4/7/11/12).

The B61-13 will be the 13th modification of the original B61 bomb. It will use the warhead from the B61-7 but with enhanced use- and security features and a guided tail kit like the B61-12 to increase accuracy.

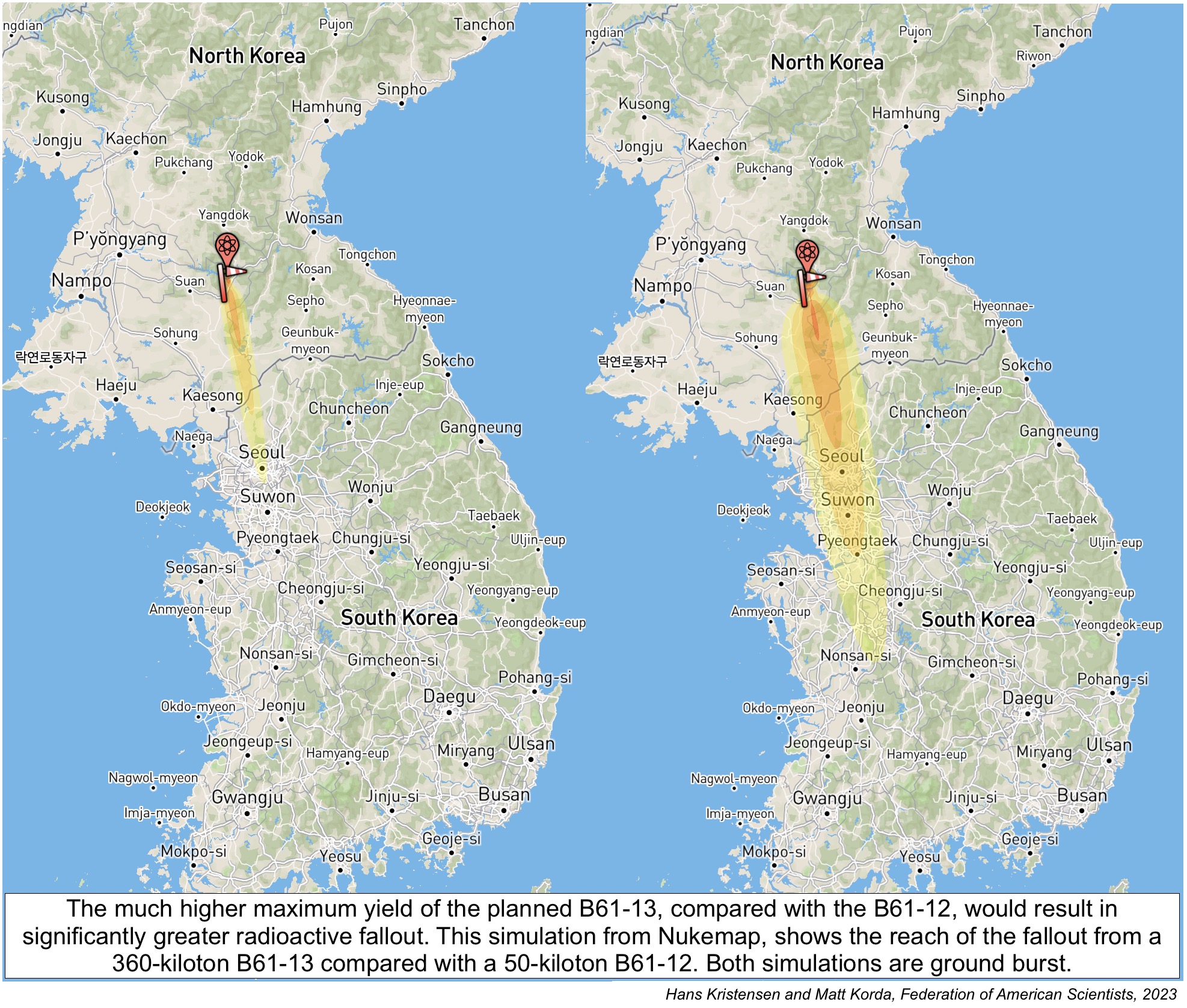

The B61-13 will have the same maximum yield as the B61-7 (360 kilotons), according to defense officials, a significant increase compared with the 50-kiloton B61-12 it is intended to supplement. If detonated on the surface, a yield of 360 kilotons would cause significant radioactive fallout over large areas.

The effects of a 360-kiloton explosion are significantly greater than those that would result from a 50-kiloton explosion. The following map compared the radioactive fallout from a ground burst detonation in North Korea. Depending on target location and weather conditions, the fallout from a B61-13 could reach half-way across South Korea (simulation from Nukemap).

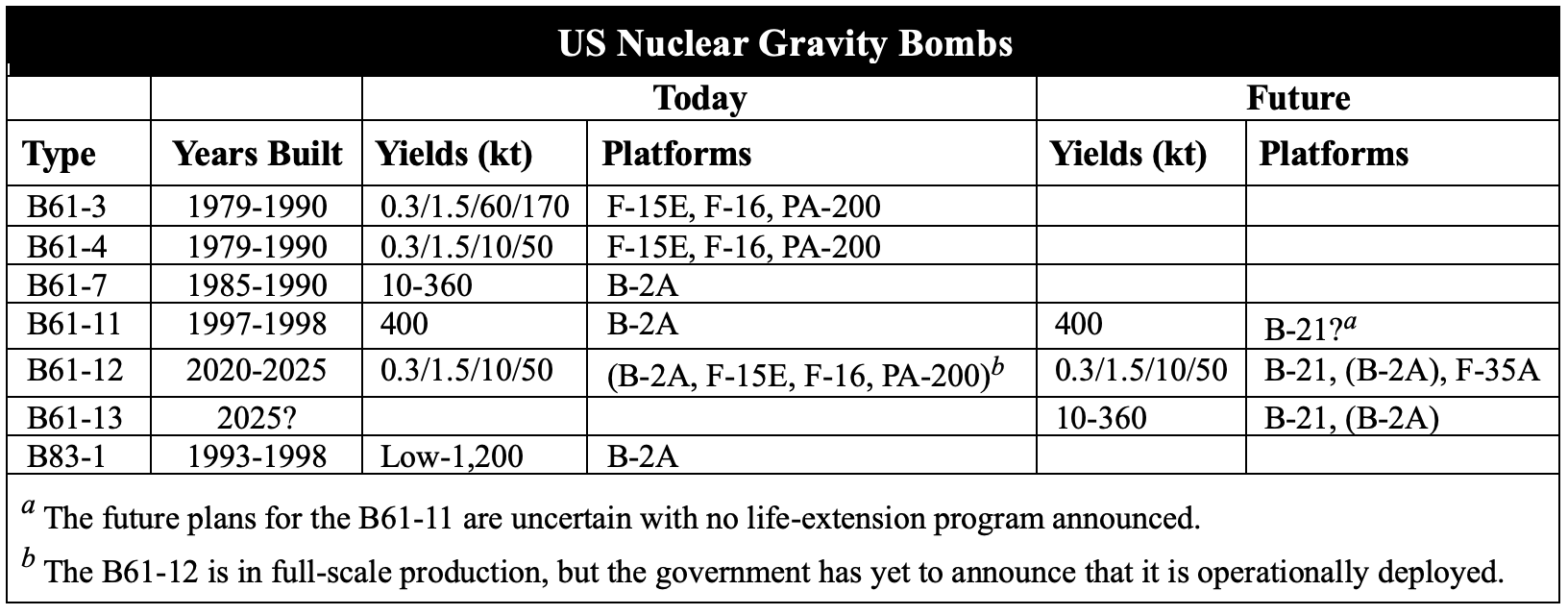

Similar to the B61-12, the B61-13 will likely also have limited earth-penetration capabilities (through soft soil), which will be enhanced by the addition of the guided tail kit. Due to the phenomenon of ground-shock coupling, the B61-13’s relatively high yield and accuracy will likely enable the bomb to strike underground targets with yields equivalent to a surface-burst weapon of more than one megaton. The B61-13 will also have lower-yield options (see table below).

Although government officials insist that the B61-13 plan is not driven by new developments in adversarial countries or a new military targeting requirement, increasing the accuracy of a high-yield bomb obviously has targeting implications. Detonating the weapon closer to the target will increase the probably that the target is destroyed, and a very hard facility could hypothetically be destroyed with one B61-13 instead of two B61-12s. The DOD says the B61-13 will “provides us with additional flexibility” by “providing the President with additional options against certain harder and large-area military targets.”

Once the B61-12 and B61-13 are produced and stockpiled, the older versions replaced, and the B83-1 retired, the changes to the gravity weapons inventory will look something like this:

Although the B61-12 was previously said to also allow retirement of the B61-11 earth-penetrator, the B61-13 plan only appears intended to facilitate retirement of the B83-1. There is currently no life-extension program for the B61-11. The plan might be to allow it to age out. Officials say the B61-13 plan does not preclude that the United States potentially decides in the future to field a new nuclear earth-penetrator to replace the B61-11. But there is no decision on this yet.

Defense officials explain that the new B61-13 will not result in an increase of the overall number of warheads in the stockpile. The reason is that the administration plans to reduce the number of B61-12s produced by the number of B61-13s produced, so the total number of new bombs will ultimately be the same. The production plan for the B61-12 involved an estimated 480 bombs for both strategic bombers and dual-capable fighters. Since the bombers will now carry both B61-12 and B61-13 bombs (in addition to the new LRSO cruise missiles), and because the actual number of targets requiring a high-yield gravity bomb is probably small, it seems likely that the number of B61-13 bombs to be produced is very limited – perhaps on the order of 50 weapons – and that production will happen at the back end of the B61-12 schedule in 2025.

Unlike the B61-12s – of which a portion will be forward-deployed to Europe for use with NATO’s dual-capable aircraft – all of the B61-13s will be stored within the United States for use with the incoming B-21 bomber and the B-2 bomber (until it is replaced by the B-21). Nonetheless, because the B61-13 will use the same mechanical and electronic interface as the B61-12, the fighters that are destined to deliver the B61-12 will also be capable of delivering the B61-13. But the current plan is that the B61-13 is only for the bombers.

The B61-13 will look identical to the B61-12 (top) but use a much more powerful warhead from the B61-7. It is intended for delivery by bombers but can technically also be delivered by fighter jets (although that is not planned).

A Political Nuclear Bomb

The military justification for adding the B61-13 to the stockpile is hard to see. Instead, it seems more likely to be a political maneuver to finally get rid of the B83-1.

Defense officials say that the decision is not related to current events or developments in China, Russia, or other potential adversaries. Nor is the administration’s decision a product of the hard and deeply buried target capability study mentioned in the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review.

The B61-13 is a separate decision, they explain.

The military doesn’t need an additional, more powerful gravity bomb. In fact, Air Force officials privately say the military mission of nuclear gravity bombs is decreasing in importance because of the risk of putting bombers and their pilots in harm’s way over heavily defended targets – particularly as long-range missiles are becoming more capable.

To that end, the military mission of the B61-13 is somewhat of a mystery, especially given that the LRSO will also be arming the bombers and that the United States has thousands of other high-yield weapons in its arsenal.

Instead, what appears to have happened is this: after defense hardliners blocked the administration’s plans to retire the B83-1, the administration likely agreed to retain the B61-7 yield in the stockpile in the form of a modern bomb modification (B61-13) that is easier and cheaper to maintain, so that they can finally proceed with the retirement of the B83-1.

As such, the B61-13 will be the second “political” weapon in recent memory. The first was the low-yield W76-2 warhead fielded in late-2019 on the Trident submarines. The next one could be a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), if defense hawks have their way.

Additional Information

• US nuclear weapons, 2023

• The B61 Family of Nuclear Bombs

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

On January 31st, the State Department issued its annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the New START Treaty, with a notable––yet unsurprising––conclusion:

“Based on the information available as of December 31, 2022, the United States cannot certify the Russian Federation to be in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty.”

This finding was not unexpected. In August 2022, in response to a US treaty notification expressing an intent to conduct an inspection, Russia invoked an infrequently used treaty clause “temporarily exempting” all of its facilities from inspection. At the time, Russia attempted to justify its actions by citing “incomplete” work regarding Covid-19 inspection protocols and perceived “unilateral advantages” created by US sanctions; however, the State Department’s report assesses that this is “false:”

“Contrary to Russia’s claim that Russian inspectors cannot travel to the United States to conduct inspections, Russian inspectors can in fact travel to the United States via commercial flights or authorized inspection airplanes. There are no impediments arising from U.S. sanctions that would prevent Russia’s full exercise of its inspection rights under the Treaty. The United States has been extremely clear with the Russian Federation on this point.”

Instead, the report suggests that the primary reason for suspending inspections “centered on Russian grievances regarding U.S. and other countries’ measures imposed on Russia in response to its unprovoked, full-scale invasion of Ukraine.”

Echoing the findings of the report, on February 1st, Cara Abercrombie, deputy assistant to the president and coordinator for defense policy and arms control for the White House National Security Council, stated in a briefing at the Arms Control Association that the United States had done everything in its power to remove pandemic- and sanctions-related limitations for Russian inspectors, and that “[t]here are absolutely no barriers, as far as we’re concerned, to facilitating Russian inspections.”

Nonetheless, Russia has still not rescinded its exemption and also indefinitely postponed a scheduled meeting of the Bilateral Consultative Commission in November. In a similar vein, this is believed to be tied to US support for Ukraine, as indicated by Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov who said that arms control “has been held hostage by the U.S. line of inflicting strategic defeat on Russia,” and that Russia was “ready for such a scenario” if New START expired without a replacement.

These two actions, according to the United States, constitute a state of “noncompliance” with specific clauses of New START. It is crucial to note, however, the distinction between findings of “noncompliance” (serious, yet informal assessments, often with a clear path to reestablishing compliance), “violation” (requiring a formal determination), and “material breach” (where a violation rises to the level of contravening the object or purpose of the treaty).

It is also important to note that the United States’ findings of Russian noncompliance are not related to the actual number of deployed Russian warheads and launchers. While the report notes that the lack of inspections means that “the United States has less confidence in the accuracy of Russia’s declarations,” the report is careful to note that “While this is a serious concern, it is not a determination of noncompliance.” The report also assesses that “Russia was likely under the New START warhead limit at the end of 2022” and that Russia’s noncompliance does not threaten the national security interests of the United States.

The high stakes of failure: worst-case force projections after New START’s expiry

Both the US and Russia have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither country will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. Without a deal after 2026, that assumption immediately disappears; both sides would likely default to mutual distrust amid fewer verifiable data points, and our discourse would be dominated by worst case thinking about how both countries’ arsenals would grow in the future.

For an example of this kind of thinking, look no further than the new Chair of the House Armed Services Committee, who argued in response to the State Department’s findings of Russian noncompliance that “The Joint Staff needs to assume Russia has or will be breaching New START caps.” As previously mentioned, the State Department report explicitly states that they have only found Russia to be noncompliant on facilitating inspections and BCC meetings, not on deployed warheads and launchers.

It is clear that the longer that these compliance issues persist, the more they will ultimately hinder US-Russia negotiations over a follow-on treaty, which is necessary in order to continue the bilateral strategic arms control regime beyond New START’s expiry in February 2026. As Amb. Steve Pifer, non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, noted during the ACA webinar, “We have three years until New START expires. That seems like a lot of time, but it’s not a long of time if you’re going to try to do something ambitious.”

To that end, both sides should be clear-eyed about the stakes, and more specifically, about what happens if they fail to secure a new deal limiting strategic offensive arms.

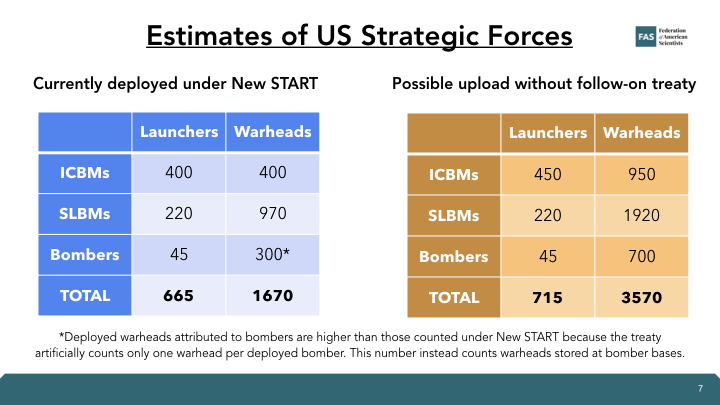

The United States has a significant upload capacity on its strategic nuclear forces, where it can bring extra warheads out of storage and add them to the deployed missiles and bombers. Although all 400 deployed US ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that is capable of carrying up to three warheads each. Moreover, the United States has an additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos which could be reloaded with missiles if necessary. With these potential additions in mind, the US ICBM force could potentially more than double from 400 to 950 warheads.

In the absence of treaty limitations, the United States could also upload each of its deployed Trident SLBMs with a full complement of eight warheads, rather than the current average of four to five. Factoring in the small numbers of submarines that are assumed to be out for maintenance at any given time, then the United States could approximately double the number of warheads deployed on its SLBMs, to roughly 1,920. The United States could potentially also reactivate the four launch tubes on each submarine that it deactivated to meet the New START limit, thus adding 56 missiles with 448 warheads to the fleet. However, this possibility is not reflected in the table because it is unlikely that the United States would choose to reconstitute the additional four launch tubes on each submarine given their imminent replacement with the next-generation Columbia-class.

Either of these actions would likely take months to complete, particularly given the complexities involved with uploading additional warheads on ICBMs. Moreover, ballistic missile submarines would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to be uploaded with additional warheads. However, deploying additional warheads to US bomber bases could be done very quickly, and the United States could potentially upload nearly 700 cruise missiles and bombs on its B-52 and B-2 bombers.

[Note: These numbers are projections based off of estimates; they are not predictions or endorsements. They also do not take into account how the number of available launchers and warheads will change when ongoing modernization programs are eventually completed, as this is unlikely to occur before New START’s expiry in 2026]

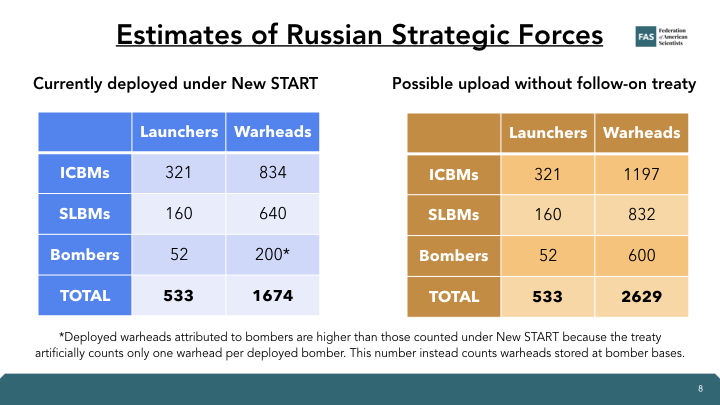

Russia also has a significant upload capacity, especially for its ICBMs. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities, in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase from approximately 834 warheads to roughly 1,197 warheads.

Warheads on submarine-launched ballistic missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without these limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased from an estimated 640 to approximately 832 (also with a small number of SSBNs assumed to be out for maintenance). As in the US case, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons. The number is highly uncertain but assuming approximately 50 bombers are operational, the number of warheads could potentially be increased to nearly 600.

Slide showing estimates of Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

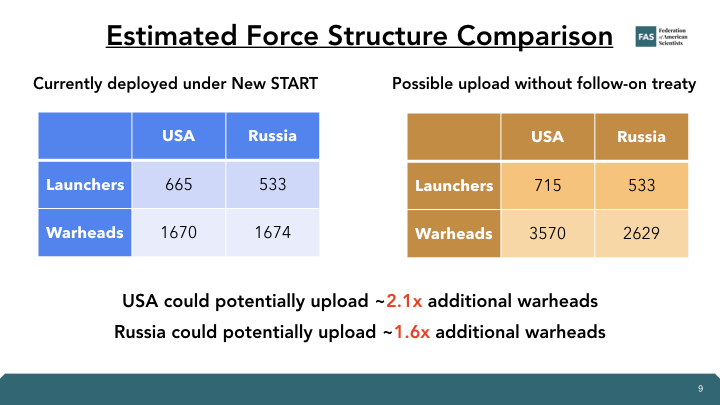

Combined, if both countries uploaded their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals would approximately double in size. The United States would have more deployable strategic warheads but Russia would still have a larger total arsenal of operational nuclear weapons, given its sizable stockpile of nonstrategic nuclear warheads which are not treaty-accountable.

Slide showing comparison estimates of US and Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

Moreover, there are expected consequences beyond the offensive strategic nuclear forces that New START regulates. If the verification regime and data exchanges elapse, both countries are likely to enhance their intelligence capabilities to make up for the uncertainty regarding the other side’s nuclear forces. Both countries are also likely to invest more into what they perceive will increase their overall military capabilities, such as conventional missile forces, nonstrategic nuclear forces, and missile defense.

These moves could trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, some of whom might also decide to increase their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. In particular, it is becoming increasingly clear that China appears to no longer be satisfied with just a couple hundred nuclear weapons to ensure its security, and in a shift from longstanding doctrine, may now be looking to size its own nuclear force closer to the size of the US and Russian deployed nuclear forces.

Some US former defense officials have suggested that the United States needs to increase its deployed nuclear force to compensate for the increased nuclear arsenal that China is already building and an alleged increase in Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons––either by negotiating a higher treaty limit with Russia or withdrawing from the New START treaty.

But doing so would not solve the problem and could put the United States on a path where it would in fact face even greater numbers of Russian and Chinese nuclear weapons in the future. A higher treaty warhead limit would obviously increase – not reduce – the number of Russian warheads aimed at the United States; and pulling out of New START would likely cause Russia to deploy even more weapons. Moreover, a significant increase in the size of US and Russian deployed nuclear forces could cause China to increase its arsenal even further. Such developments could subsequently have ripple effects for India, Pakistan, and elsewhere – developments that would undermine, rather than improve, US and international security.

Uploading more warheads is not necessary to maintain deterrence

It is important to note that even if such worst-case scenarios were to occur, in the past the Department of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence have assessed that even a significant Russian increase of deployed nuclear warheads would not have a deleterious effect on US deterrence capabilities. A 2012 joint study assessed:

“[E]ven if significantly above the New START Treaty limits, [Russia’s deployment of additional nuclear warheads] would have little to no effect on the U.S. assured second-strike capabilities that underwrite our strategic deterrence posture. The Russian Federation, therefore, would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.”

Although the political situation has dramatically changed over the past decade since the study was published, this particular deterrence dynamic has not. The United States’ second-strike capabilities remain as secure today––even among Russia’s noncompliance and China’s nuclear buildup––as they did a decade ago. As a result, it seems clear that although uploading additional warheads onto US systems may seem like a politically strong response, it would not offer the United States any additional advantage that it does not already possess, and would likely trigger developments that would not be in its national security interest.

—

Background Information:

- “The Long View: Strategic Arms Control After the New START Treaty,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 2022.

- “United States nuclear weapons, 2023,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 2023.

- “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2022.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

National Security and LGBTQI+ Rights

On February 4, President Biden issued a memorandum to agency heads on “advancing the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex persons around the world.”

He directed that “it shall be the policy of the United States to pursue an end to violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or sex characteristics.”

Somewhat surprisingly, the memorandum was designated National Security Memorandum/NSM-4 and was published as such in the Federal Register on February 26.

This was unexpected since the NSM designation was not included in the original White House release on February 4, and the memorandum itself does not make any explicit reference to national security. The Biden memo builds on a 2011 Obama Memorandum which also did not invoke national security.

In effect, the defense of LGBTQI+ rights has now been elevated by the Biden Administration to a national security policy of the United States.

* * *

A January 21 White House policy on International COVID-19 Response was originally issued as National Security Directive 1.

But perhaps because the “National Security Directive” designation was previously claimed by the first Bush Administration, Biden’s NSD-1 was renamed and reissued as National Security Memorandum 1.

An unnumbered National Security Memorandum dated February 4 on Revitalizing the National Security Workforce is apparently NSM-3.

Biden Aims for “Highest Standards of Transparency”

“In a democracy, the public deserves as much transparency as possible regarding the work of our national security institutions, consistent with legitimate needs to protect sources and methods and sensitive foreign relationships,” according to a memorandum issued by President Biden on February 4.

“The revitalization of our national security and foreign policy workforce requires a recommitment to the highest standards of transparency,” the President wrote.

See Revitalizing America’s Foreign Policy and National Security Workforce, Institutions, and Partnerships, National Security Memorandum, February 4, 2021.

The memorandum presents a set of principles to guide the conduct and operation of the whole national security apparatus with a particular focus on “strengthening the national security workforce.”

The President notably envisions increased engagement with public interest organizations, among others.

“It is the policy of my Administration to advance its national security and foreign policy goals by harnessing the ideas, perspectives, support, and contributions of a diverse array of partners, such as State and local governments, academic and research institutions, the private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and civil society.”

The memorandum also calls for “a foreign policy for the middle class.”

“Our work abroad is — and always will be — tethered to our needs at home. I have committed to the American people that my Administration will prioritize policies abroad that help Americans to succeed in the global economy and ensure that everyone shares in the success of our country here at home.”

* * *

Despite the previous issuance of “National Security Directive 1” on January 21, the national security directives of the Biden Administration are to be known as National Security Memoranda (NSMs). (Update: National Security Directive 1 was subsequently redesignated as National Security Memorandum 1.)

The President made the new designation in National Security Memorandum (NSM) 2 on Renewing the National Security Council System, February 4.

“This document is one in a series of National Security Memoranda that, along with National Security Study Memoranda, shall replace National Security Presidential Memoranda and Space Policy Directives [of the Trump Administration] as instruments for communicating Presidential decisions about national security policies of the United States,” the NSM states.

NSM-2 defines the organization of the National Security Council in the Biden Administration. So, for example, the prior system of NSC Policy Coordination Committees will be replaced by a new system of Interagency Policy Committees.

“The Biden NSC structure will reflect the cross-cutting nature of our most critical national challenges by more regularly integrating cabinet officials from domestically-focused agencies into national security decision-making,” according to a White House statement.

“President Biden has also made clear that his National Security Council will bring professionalism, respect, transparency, inclusivity, collaboration, collegiality, and accountability to its work. Above all, the Biden administration will respect the rule of law and act consistently with our values,” the statement said.

There will of course be many opportunities to test that vision.