Depot In Belarus Shows New Upgrades Possibly For Russian Nuclear Warhead Storage

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

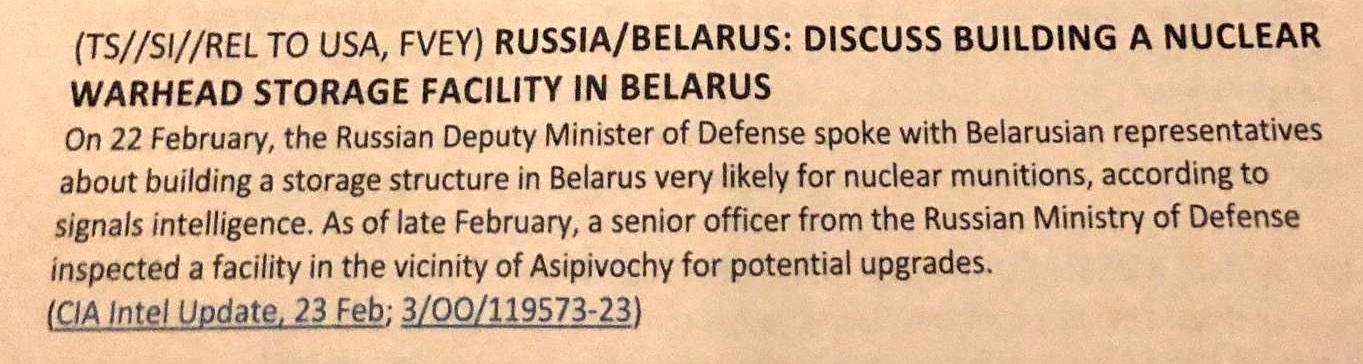

The upgraded enclosure is located inside an existing military depot east of the town of Ashipovichy. Leaked documents on Discord indicated that in February 2023, the CIA reported that “a senior officer from the Russian Ministry of Defense inspected a facility in the vicinity of Asipivochy [sic] for potential upgrades” to serve as “a nuclear warhead storage facility in Belarus” (see excerpt of CIA leaked report below).

This part of a leaked CIA document reported Russian inspection of Asipovichy for potential nuclear warhead storage.

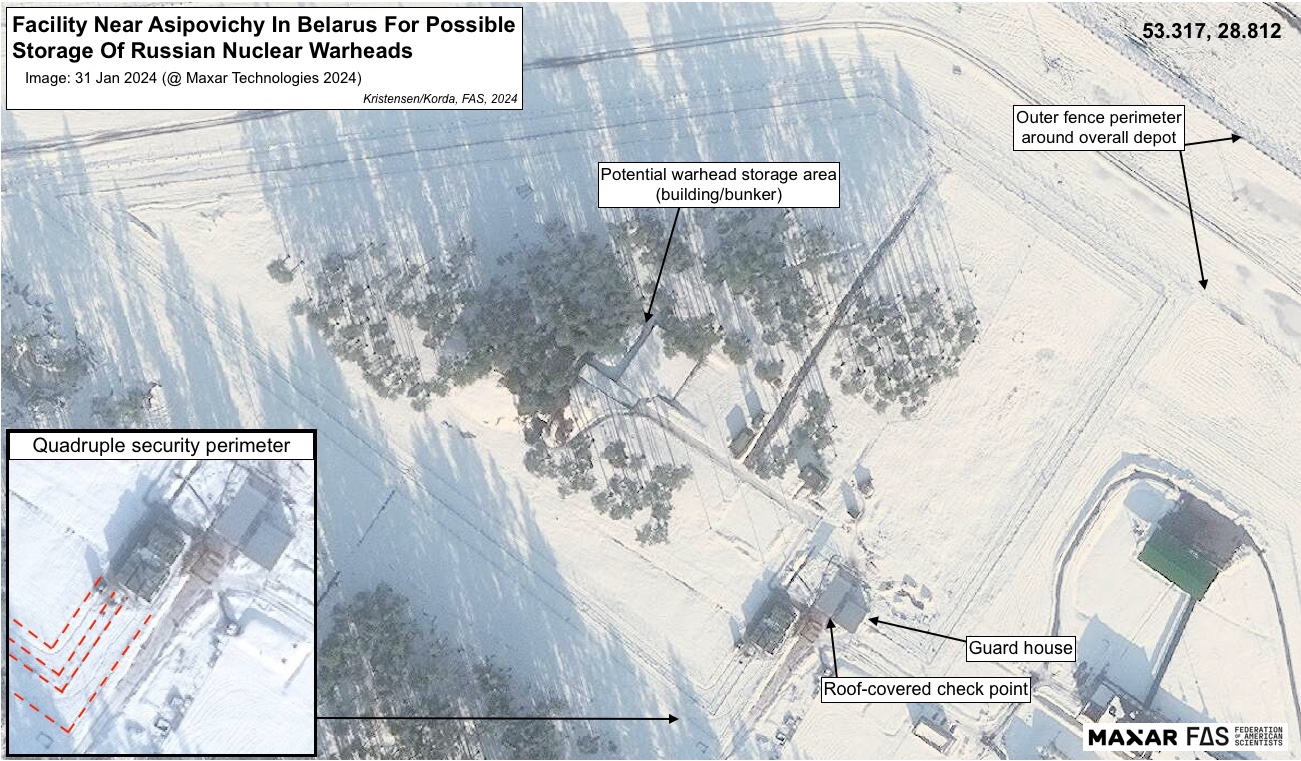

A satellite image provided by Maxar Technologies shows that part of the depot near Asipovichy has since been upgraded with a quadruple-fence security perimeter and a roof-covered guarded access point (see image below).

Upgrades to Asipovichy depot now shows quadruple security perimeter.

Satellite images show that construction began at the facility around the time of the reported visit by the senior Russian official. The upgrades have progressed slowly, with the initial construction of a double-layer security perimeter. That would be insufficient for storage of nuclear warheads. In October 2023 construction of a new perimeter began inside the existing security perimeter, and the Maxar image from late-January 2024 shows what appears to be a total of four security perimeters. The construction of the added perimeters shows significant digging for what could potentially be cables and various sensors. Trees within the new inner perimeter have also been cleared by approximately 20 meters away from the fencing.

If so, these upgrades would more closely resemble the level of physical protection that Russian authorities would require for storage of nuclear weapons.

Russian and Belarusian statements over the past two years have repeatedly claimed that nuclear weapons had been brought to Belarus, but we had previously not seen clear evidence that facilities had been readied for that purpose.

Earlier today, under the headline “Russian Nuclear Weapons Are Now In Belarus,” Foreign Policy reported that “Western officials,” including the Lithuanian defense minister, “confirmed the news of the deployment.” The article says that “a senior Lithuanian diplomat and other Western officials indicated to Foreign Policy that Russia had built specific storage facilities and railway systems in Belarus to potentially house a nuclear arsenal.”

It remains unclear if the confirmations referred to nuclear-capable launchers or the actual warheads for those launchers. But the upgrade at the Asipovichy depot shows security features that potentially could match upgrades required for nuclear warhead storage at the same facility that the Russian defense official apparently inspected one year ago.

If nuclear warheads have indeed been moved to Belarus, it does not give Russia a significant military advantage in eastern Europe. Russia already maintains modernized nuclear storage facilities in Kaliningrad and has long had the ability to target NATO countries with nuclear weapons. Instead, the deployment appears designed to unnerve NATO’s eastern-most member states and highlight Russia’s status as a nuclear power.

Additional background information:

• Nuclear Weapons Sharing, 2023

• Belarus “Nuclear-Capable” Iskanders Get A New Garage

• Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans In Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?

• Russian Nuclear Weapons In Belarus? A CNS Roundtable Discussion

• Video Indicates That Lida Air Base Might Get Russian “Nuclear Sharing” Mission In Belarus

• Geo-Location of Russian-Supplied Iskander Launchers Training at Osipovichi i Belarus

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans in Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?

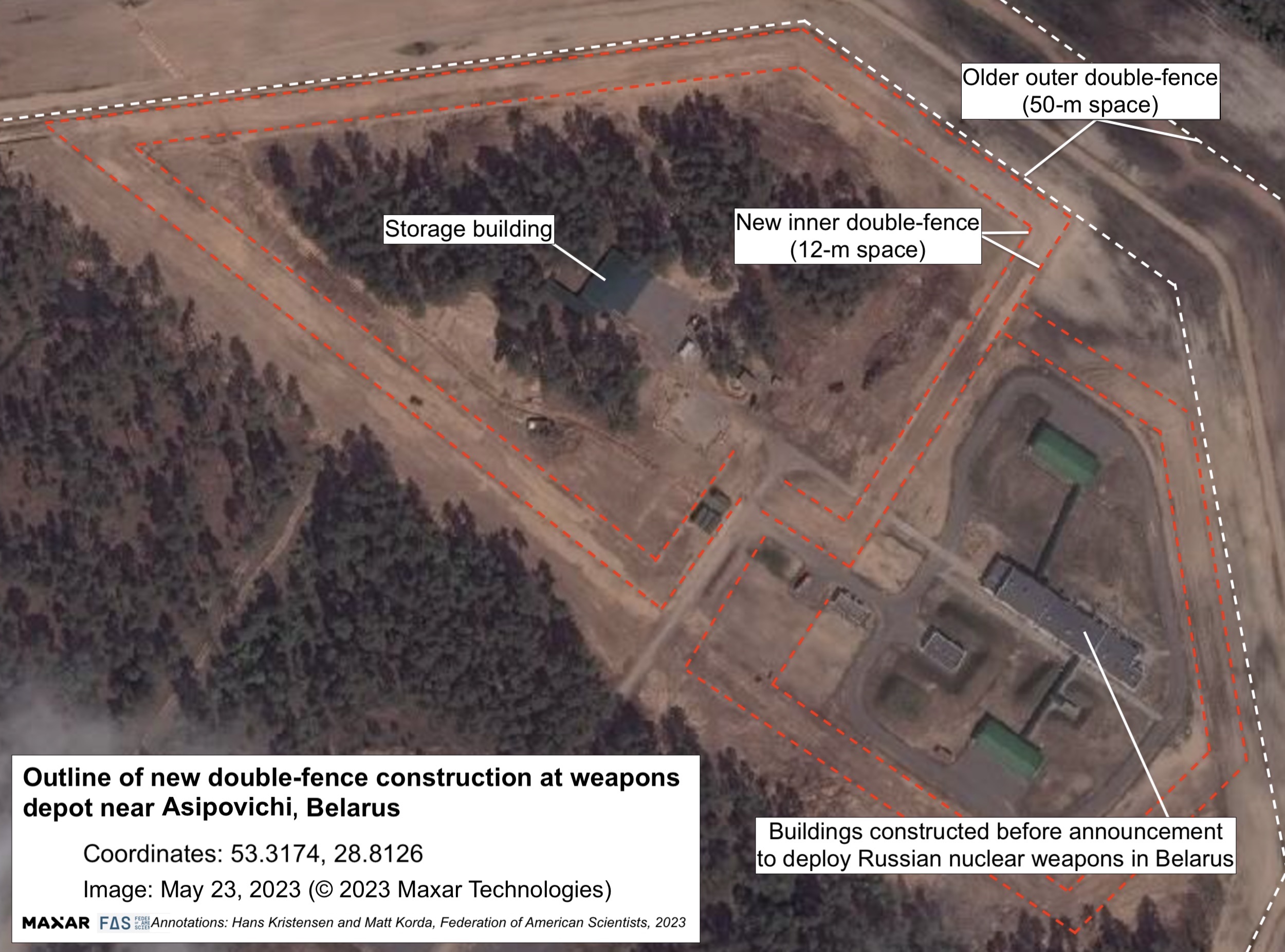

Shortly after a Russian defense official inspected possible nuclear weapons storage site near Asipovichy, construction of additional security perimeters began at depot.

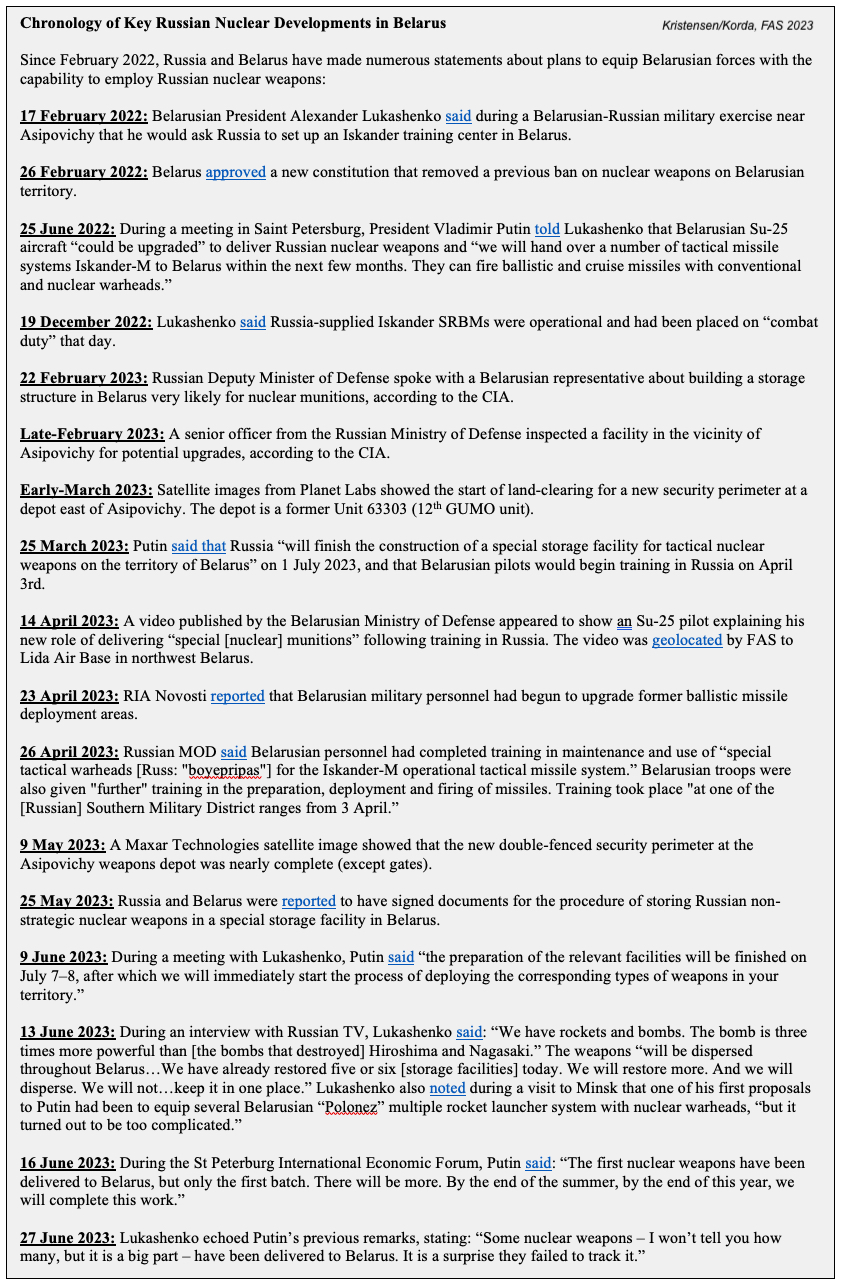

New satellite images show that the construction of a double-fenced security perimeter is underway at a weapons depot near the town of Asipovichy in central Belarus.

The US Central Intelligence Agency reported in late-February 2023 that a senior officer from the Russian Ministry of Defense had inspected a facility in the vicinity of Asipovichy (occasionally also spelled Osipovichi) for a potential upgrade to nuclear weapons storage.

Asipovichy is the deployment area for the dual-capable Iskander (SS-26) launchers that Russia supplied to Belarus in 2022. Interestingly, the weapons depot featured in this article is roughly only 25 kilometers southeast of a vacant military base that, according to the New York Times, could be used to house relocated Wagner Group fighters in Belarus. This does not, however, imply any connection between the Wagner Group and Russian nuclear deployments in Belarus, which would be overseen by the Russian Ministry of Defence’s 12th Main Directorate (also known as the 12th GUMO).

President Vladimir Putin announced in March that Russia plans to complete a nuclear weapons storage site in Belarus by July 1st, 2023, but he later modified the timeline to July 7th-8th, apparently due to delays with preparing the storage facilities.

It is important to emphasize upfront that at this stage, we are not able to make a positive identification that this site is intended for or will definitively be used to store Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus. As we discuss in detail below, while the construction timeline and some signatures correlate with a potential nuclear storage site, other signatures do not, and these raise uncertainty about the purpose of the upgrade at the Asipovichy depot. In fact, overall, we are underwhelmed by the lack of visual evidence of the construction and infrastructure that would be expected to support the deployment of Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus. We have also surveyed satellite imagery of numerous other military facilities at locations mentioned in various reports, but we have yet to find visual evidence that conclusively indicates the presence of an active nuclear weapons facility on the territory of Belarus.

Below we survey facilities at various locations in Belarus that have been mentioned in the public debate as potential transit or deployment areas for nuclear-capable forces or even nuclear weapons.

Iskander Missile Launchers

Asipovichy is an important region because it is the location of new nuclear-capable Islander short-range missile launchers that Russia transferred to Belarus in 2022. One Belarusian news report stated the transfer happened in December, but satellite images show what appear to be Iskander launchers at the training site to the west of Asipovichy in August and October 2022 (see images below).

Iskander launchers have been observed at a training range west of Asipovichy several times.

The Russian Ministry of Defense announced in late-April 2023 that Belarusian personnel had completed training in maintenance and use of “special tactical warheads [Russ: “boyepripas”] for the Iskander-M operational tactical missile system” at one of Russia’s Southern Military District ranges in early April.

The Belarusian brigade base for the Iskander launchers is thought to be located in the southern outskirts of Asipovichy, roughly seven miles west of the depot undergoing upgrades. Some five miles to the west of that garrison, there is a training range where Iskander launches have been seen on several occasions (see image below).

Belarusian Iskander military photos were geolocation to the training range west of Asipovichy.

Most Russian Iskander bases have extensive support facilities as well as a distinctive missile storage site (see image below). No similar facility has been found near Asipovichy. The Belarusian military probably uses different storage standards and could potentially use the dirt-covered bunkers in the south-west corner of the facility.

The Belarusian Iskander base does not include the distinctive missile storage site found at most Russian Iskander bases.

A few Russian Iskander bases also do not have the more elaborate missile storage site. That includes the Iskander base in Kaliningrad.

Fighter-Bomber Aircraft

In their public remarks during a meeting in St. Petersburg on 25 June 2022, Presidents Putin and Lukashenko explicitly mentioned nuclear upgrade of Belarusian Su-25 aircraft. A year later, on 14 April 2023, the Belarusian Ministry of Defense published a video of what appeared to be an Su-25 pilot at Lida Air Base explaining the new nuclear role.

An examination of the Lida base area shows no physical indications of upgrades of the kind that are thought would be required to support nuclear weapons deployment. The very latest imagery shows early construction of what appears to be an additional security perimeter around the munitions storage area at the base (see image below). It is too soon to tell, but as in the case of the Asipovichy upgrade, a second fence security perimeter does not necessarily suggest a nuclear weapons upgrade; it could simply be improvement of an existing security infrastructure.

Construction of a second security perimeter at Lida Air Base has begun but there is yet no clear indication this is related to nuclear weapons.

There have also been some speculations that the Baranavichy Air Base further to the south, which is equipped with more modern Su-30SM jets, might be a potential candidate for the nuclear mission. We are not aware of any official statements to that effect and have not seen any observable indications of physical upgrades needed to support nuclear operations there.

As with the Iskander base area upgrades near Asipovichy, we can’t positively exclude the existence of an undetected facility near the western air bases. But so far, we don’t see conclusive physical indications of nuclear weapons related upgrades on or near Lida or Baranavichy. It is also relevant to mention that both bases are very close to NATO territory; Lida is only about 20 miles (35 kilometers) from Lithuania.

Warhead Transportation

On June 16th, Putin announced: “The first nuclear weapons have been delivered to Belarus, but only the first batch. There will be more. By the end of the summer, by the end of this year, we will complete this work.”

Careful monitoring of the 12th GUMO’s transit hub at Sergiev Posad has not yet indicated the shipment of specialized nuclear-related materials, such as fencing, certified loading equipment, vault doors, or environmental control systems. However, on June 27th, a group that monitors the Belarusian railway industry reported that nuclear weapons and related equipment would be delivered to Belarus in two stages, one in June and one in November––echoing Putin’s delivery timeline. The group reported that the shipments would involve three departures planned from Potanino, Lozhok, and Cheboksary stations in Russia, arriving at Prudok station in Belarus––more than 200 kilometers north of the Asipovichy depot. These locations in Russia are hundreds of kilometers away from known nuclear storage sites, and so could either be locations for subcomponents or security equipment rather than the warheads themselves, or they could potentially be an attempt to obfuscate where the warheads would actually be coming from.

Preparation of rail transfer points and storage would require construction of a number of unique security features and support facilities. An examination of satellite images of the Prudok station area in Belarus, however, revealed no observable indication of construction needed to safeguard nuclear weapons (see image below).

Satellite imagery of the Prudok rail station and depot area reported as the first transfer point of Russian nuclear weapons into Belarus show no observable indication of preparations to nuclear weapons storage.

Many Uncertainties

It is important to be clear that these satellite images do not prove decisively that the construction at Asipovichy or other known facilities is related to nuclear weapons storage. It could potentially be related to non-nuclear weapon systems, such as air-defense missiles. There are several uncertainties that should be mentioned and carefully considered:

First, the security perimeter has two inner fences, less than the three or four normally seen at Russia nuclear weapons storage sites. This is a significant difference, because the standard of at least three layers of fencing is directly correlated with the ability of the fence disturbance system to detect security threats to the complex. Fewer layers of fencing (and thus less clear space) could cause the microwave detection system to be accidentally triggered by movement inside the complex itself. To avoid that, vegetation has been removed along the new 12-meter wide inner security perimeter. Construction is ongoing and there is so far no visual indication of electronic sensors inside the new perimeter.

Construction of an additional double-fence security perimeter began at a weapons depot east of Asipovichy in central Belarus shortly after a senior Russian defense official inspected a facility in the area for potential storage of nuclear weapons

In comparison, Russian base- and national-level nuclear weapons storage facilities have extensive security features. The base-level storage facility near Tver approximately 325 kilometers (200 miles) from the Belarusian border has considerably stronger security features around the weapons bunkers (see image below).

The outline of this Russian base-level nuclear weapons storage site near Tver is very different from the Asipovichy site.

Second, there is no bunker visible inside the enclosure, another normal feature of Russian nuclear weapon storage sites. Apart from physical protection, nuclear weapons require climate-controlled storage facilities.

Third, there is no visible segregated housing for the large number of Russian 12th GUMO personnel that would be needed to protect and manage nuclear warheads.

Fourth, the depot is next to a storage site for conventional high explosives. As other researchers have pointed out, it would be highly unusual for conventional and nuclear warheads to be stored within the same perimeter in order to maintain the security of the warheads and to segregate the chain of custody between Russian 12th GUMO personnel and Belarusian army personnel.

These differences could potentially be explained if the Belarusian site is a temporary transit site and not intended for permanent storage, but rather to introduce nuclear weapons in a crisis.

It is also curious that part of the new double-fence construction extends around a group of buildings that were constructed in 2017-2018, long before any statements were made about deploying Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus.

Even if Russia intends to follow through on its planned construction of a storage site in Belarus, it is not guaranteed that any nuclear weapons would actually cross the border in peacetime. Rather, it is possible that Russia’s actions instead constitute the building blocks for a potential future decision on deployment. Moreover, some analysts have suggested that these actions could be deliberately designed to remind the West of Russia’s nuclear-armed status, rather than actually shift Russian force posture.

In total, the facility upgrade at Asipovichy is important to monitor given the CIA report about Russia nuclear-related storage inspections in the area. So far, however, our observations and analyses show no clear observable indicators of construction of the facilities we expect would be needed to support transport and deployment of Russian nuclear weapons into Belarus. As always, we don’t know what we don’t know and it is of course possible that there are other facilities that we are not aware of that would indicate nuclear weapons activities.

Positive identification of this and other potential facilities will have to await additional information. And we look forward to the contribution of other researchers.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Video Indicates that Lida Air Base Might Get Russian “Nuclear Sharing” Mission in Belarus

On 14 April 2023, the Belarusian Ministry of Defence released a short video of a Su-25 pilot explaining his new role in delivering “special [nuclear] munitions” following his training in Russia. The features seen in the video, as well as several other open-source clues, suggest that Lida Air Base––located only 40 kilometers from the Lithuanian border and the only Belarusian Air Force wing equipped with Su-25 aircraft––is the most likely candidate for Belarus’ new “nuclear sharing” mission announced by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The Belarusian MoD’s military channel features a Belarusian pilot standing in front of a Su-25 aircraft at an unidentified air base.

The video shows the pilot standing in a revetment with a Su-25 in the background. The interview takes place at a grassy location with trees in the distance along with several distinct features, including two drop tanks flanking the Su-25 on either side, and objects behind the aircraft. The revetment itself is also somewhat distinct, as the berm wraps around three sides of the hardstand and the size and orientation of the six rectangular tiles across the opening are clearly visible in the video.

The Belarusian MoD’s video shows a Su-25 aircraft sitting in a revetment surrounded by berms and trees, with drop tanks visible on either side of the aircraft.

Although the pilot is announcing the completion of their training that occured in Russia, the footage was filmed and released by the Belarusian Ministry of Defense. This factor seemed to indicate that the filming location took place in Belarus instead of at the training center in Russia. Additionally, while Su-25s have operated out of other air bases in Belarus throughout the war, including Luninets Air Base, the only Su-25 wing in the Belarusian Air Force is based at Lida.

After analyzing the satellite imagery of other possible candidate hardstands, including those at Luninets and Baravonichi, the video’s signatures appeared to most closely match a specific hardstand found at Lida Air Base. There are multiple revetments on the western side of the base, but the existence and location of a pole on top of one particular sloped berm, as well as the location of the trees in the background, the drop tanks, and the orientation of the tiles on the tarmac all align closely with features from the video footage. While the specific aircraft from the video has yet to be identified (although the individualized camouflage patterns on each Su-25 will help with this process), all of these factors suggest the video was filmed at Lida Air Base.

During and immediately after the Cold War, the Lida area was was home to a missile operating base for the 49th Guards Missile Division, first for the SS-4 MRBM, then the SS-20 IRBM, and finally the SS-25 ICBM before the division disbanded in 1997. The former missile operating base is located only ten kilometers south of the air base, and while some areas appear to still be active (perhaps in a civilian or other military role), others appear to be overgrown.

Currently, Lida is home to the Belarusian Air Force’s 116th Guards Assault Aviation Base, which flies the Su-25 Frogfoot––the type of plane confirmed by both the Belarusian Ministry of Defense and President Putin as being newly re-equipped to deliver tactical nuclear weapons. Lida’s Su-25 aircraft have also reportedly been used to conduct strikes in Ukraine.

Two additional data points suggest that Lida is the most likely candidate: on March 25th, Putin announced in an interview with Rossiya 24 that Belarusian crews would begin training in Russia on April 3rd. Belarusian Telegram channels subsequently identified these crews as being from Lida, with one channel stating that “According to my sources, the entire flight and engineering staff of the Lida air base will undergo retraining in Russia” (h/t Andrey Baklitskiy).

In addition, on April 2nd, Russia’s ambassador to Belarus stated that Russian nuclear weapons will be “moved up close to the Western border of our union state” (the supranational union of Russia and Belarus). Although the ambassador declined to offer a more specific location, Lida Air Base is located closer to NATO territory than any other suitable candidate site––only about 40 kilometers from Lithuania’s southern border and approximately 120 kilometers from Poland’s eastern border. Although this would mean a longer journey to transport the nuclear weapons from Russia (and could also make the weapons more vulnerable to NATO strikes), its proximity to Alliance territory would be a clear nuclear signal to NATO.

Challenges for the “nuclear sharing” mission

At the time of publication, it remained highly unclear whether Russia actually intends to deploy nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory, or whether it is developing the infrastructure needed to potentially deploy them in the future. It is clear, however, that such a deployment would likely come with logistical challenges.

President Putin’s March 25th announcement noted that Russia would begin training Belarusian nuclear delivery crews on April 3rd and “on July 1, we [will finish] the construction of a special storage facility for tactical nuclear weapons on the territory of Belarus.” Judging by the April 14th video released by the Belarusian Ministry of Defence, the Belarusian crews completed their training within this short period. This is an extraordinarily fast turnaround for completing the certification process; by contrast, nuclear certification for US/NATO nuclear weapon systems can take months, or even years. And as expert Bill Moon pointed out during a recent roundtable discussion, specialized equipment for warhead transportation and handling would also need to undergo intensive certification processes, which can take months.

Additionally, other Russian nuclear storage sites have taken years to upgrade. Usually, permanent nuclear storage sites in Russia have multi-layered fencing around both the perimeter as well as the storage bunkers themselves inside the complex, which can take months to install. Even a temporary site would still require extensive security infrastructure. Moreover, personnel from the 12th GUMO––the department within Russia’s Ministry of Defence that is responsible for maintaining and transporting Russia’s nuclear arsenal––would also necessarily be deployed to Belarus to staff the storage site (regardless of whether nuclear weapons were present or not) and would need a segregated living space. Bill Moon, who has decades of experience working alongside the 12th GUMO, estimates that this could be a contingent of approximately 100 personnel, including warhead maintainers, guards, and armed response forces. Constructing these kinds of facilities could also take many months to build up, revitalize, and maintain. Although it may be possible to complete construction by Putin’s July 1st deadline, a storage facility would not be ready to actually receive warheads until all of the specialized equipment and personnel were in place.

In order to meet this schedule, as Bill Moon highlighted during the recent roundtable discussion, personnel from the 12th GUMO would have to already be preparing and securing the warhead transportation route, as well as the rail spur used to transfer the warheads from trains to specialized trucks. Lida Air Base has an enclosed rail spur on-site that could potentially be used for this, although it could also require additional security infrastructure. Overall, such a deployment would be quite a difficult task: not only would deploying warheads to Lida Air Base be a very long distance for the warheads and associated equipment to travel, but both the Russian and Belarusian rail networks have experienced significant disruptions due to the war in Ukraine, from both anti-war activists and Ukrainian strikes.

Notably, in May 2022 a Russian anarcho-communist activist group announced that they had sabotaged the rail tracks leading out of the 12th GUMO’s main transit hub at Sergiev Posad in an act of protest against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This site would be used to stage and transport specialized storage and warhead handling equipment, such as fencing, vault doors, and environmental control systems––as well as crews––from Russia to Belarus. In particular, the activist group claimed to have used standardized construction tools to unscrew the nuts connecting the rail joints together, thus allowing them to lift and move the rail tracks.

Telegram channel announcing a Russian anarcho-communist group’s successful sabotage of a rail line leading to the 12th GUMO’s main transit hub at Sergiev Posad

The group specifically noted that they wanted to conduct a type of sabotage that was “less visible so the train wouldn’t have time to slow down to a stop.” Given the relative ease with which this attack was conducted, the relative invisibility of the sabotage, and the distance that the warheads and equipment would need to travel to reach Lida or another destination inside Belarus, it is clear that the 12th GUMO’s task of securing the rail lines would be important, yet extremely difficult to accomplish.

Given all of these complexities, if Putin does indeed intend to transfer warheads to Belarus, it is highly unlikely that such a deployment would take place until at least after Putin’s July 1st construction deadline, and it could also be coupled with yet another high-level nuclear signal.

Background Information:

- “United States nuclear weapons, 2023,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 2023.

- “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2022.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.