New Environmental Assessment Reveals Fascinating Alternatives to Land-Based ICBMs

A new Air Force environmental assessment reveals that it considered basing ICBMs in underground railway tunnels––or possibly underwater.

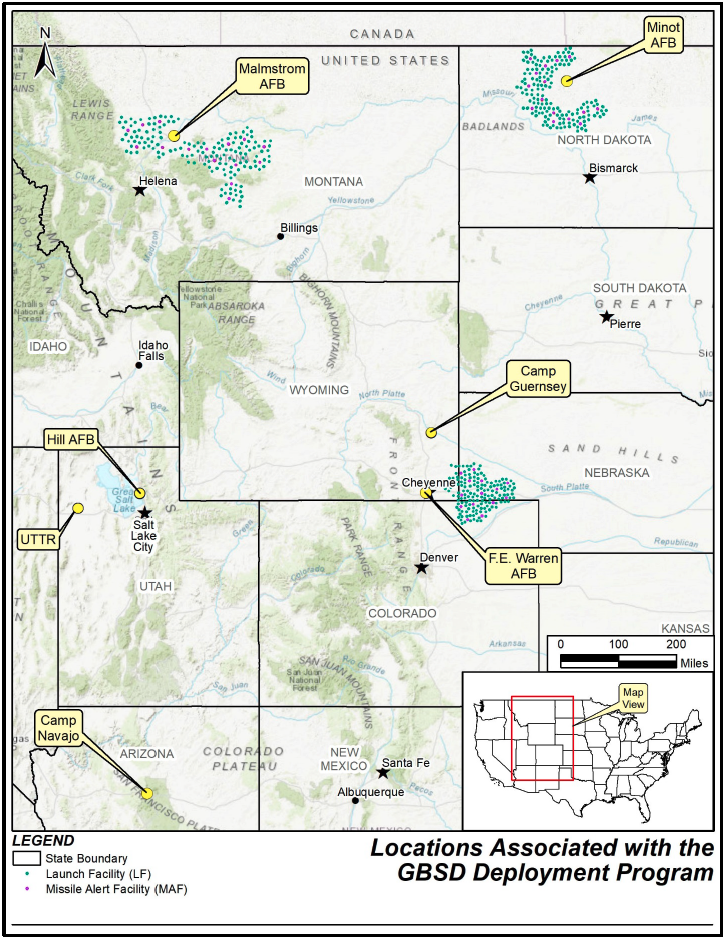

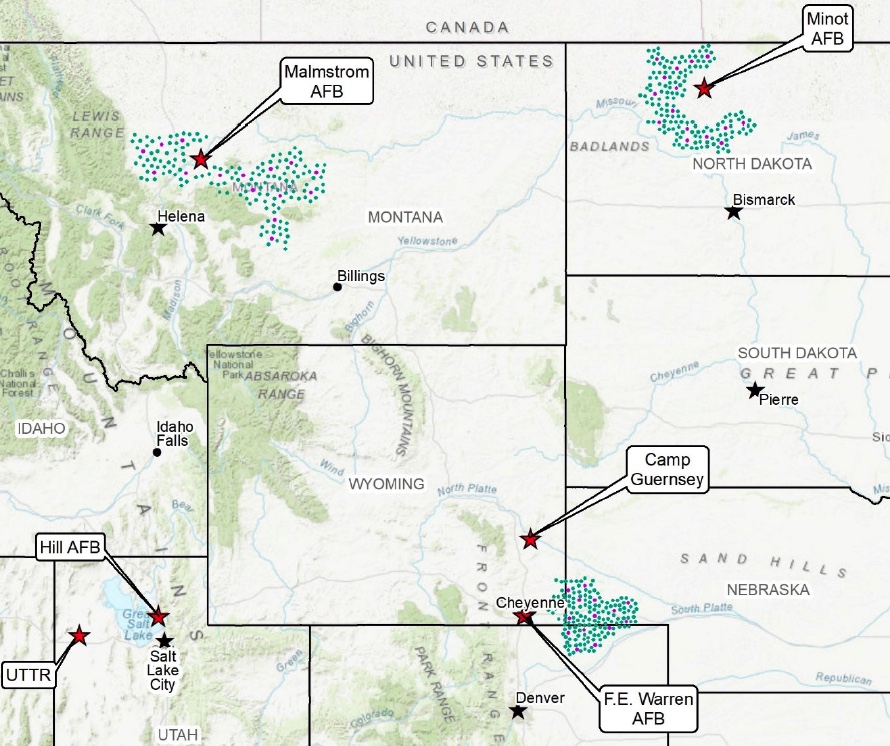

Map of the ICBM missile fields contained within the Air Force’s July 2022 assessment.

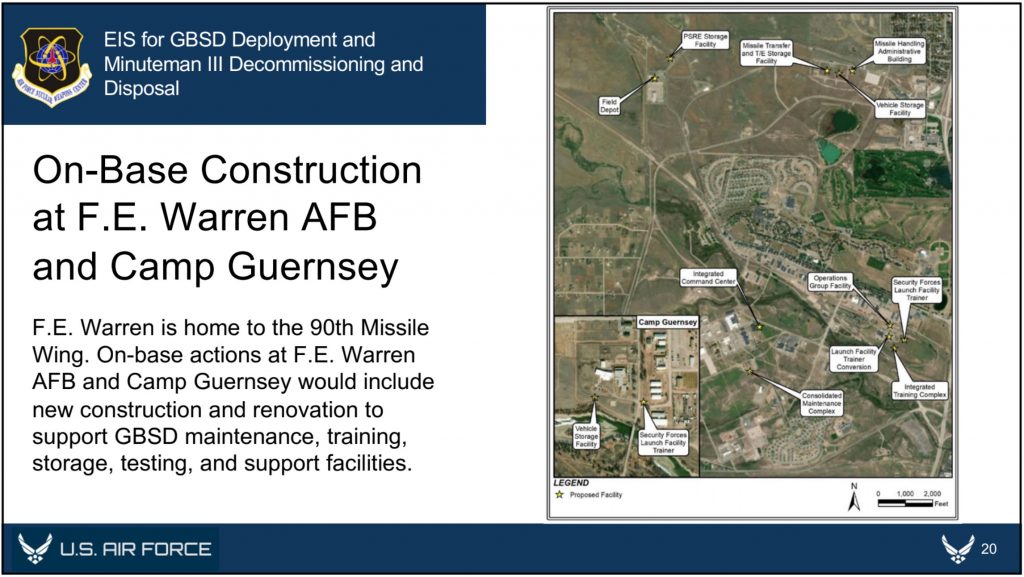

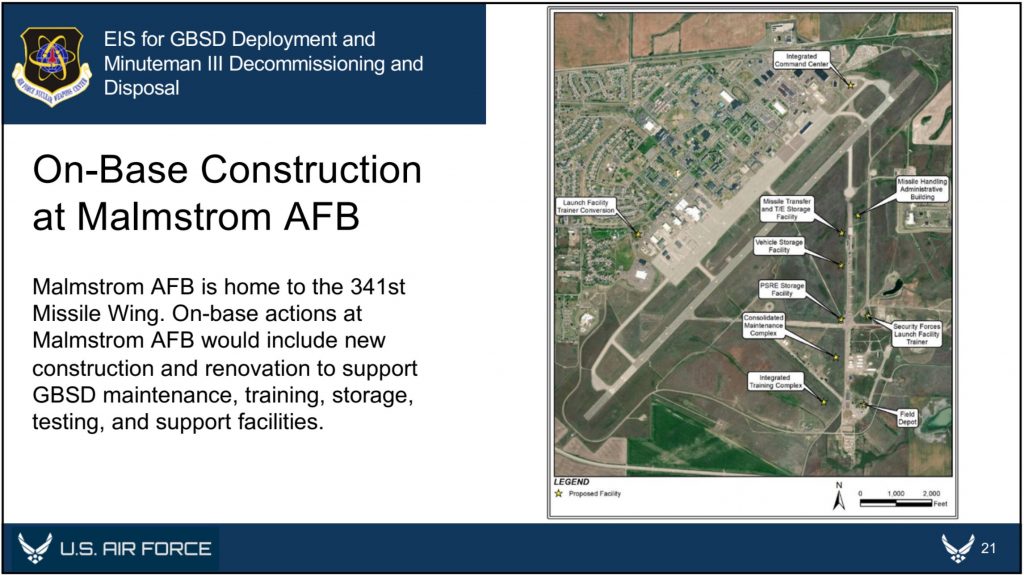

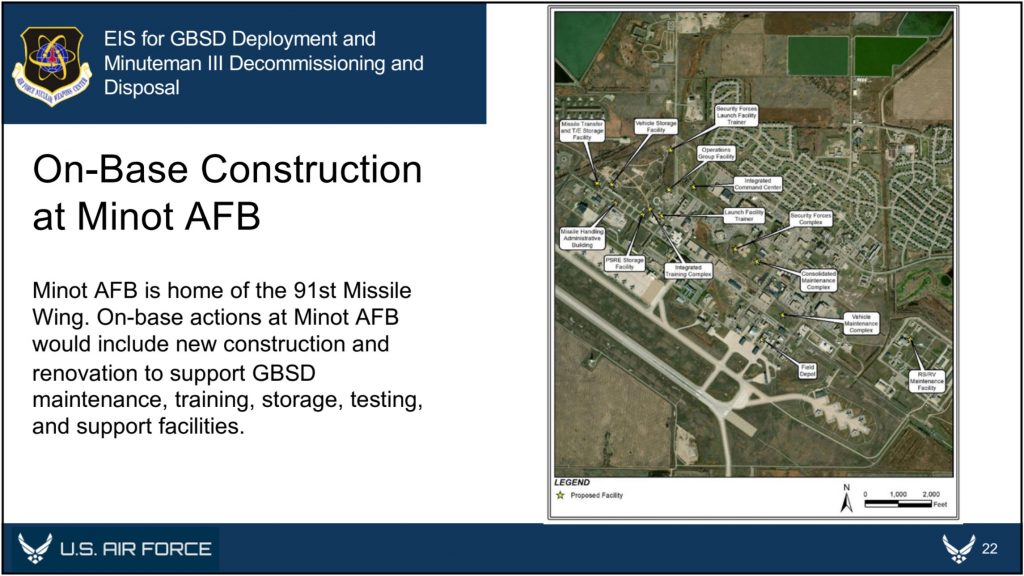

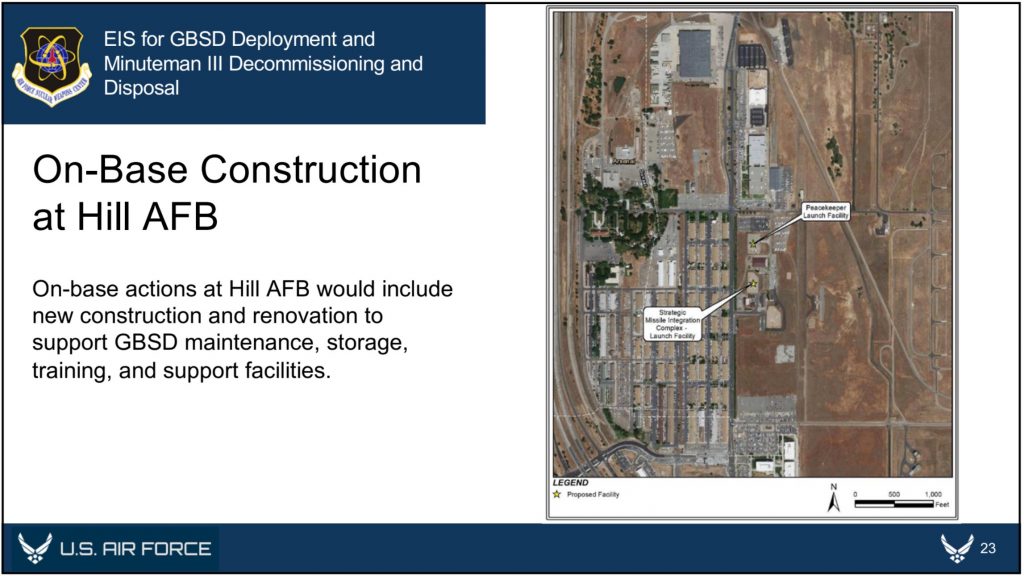

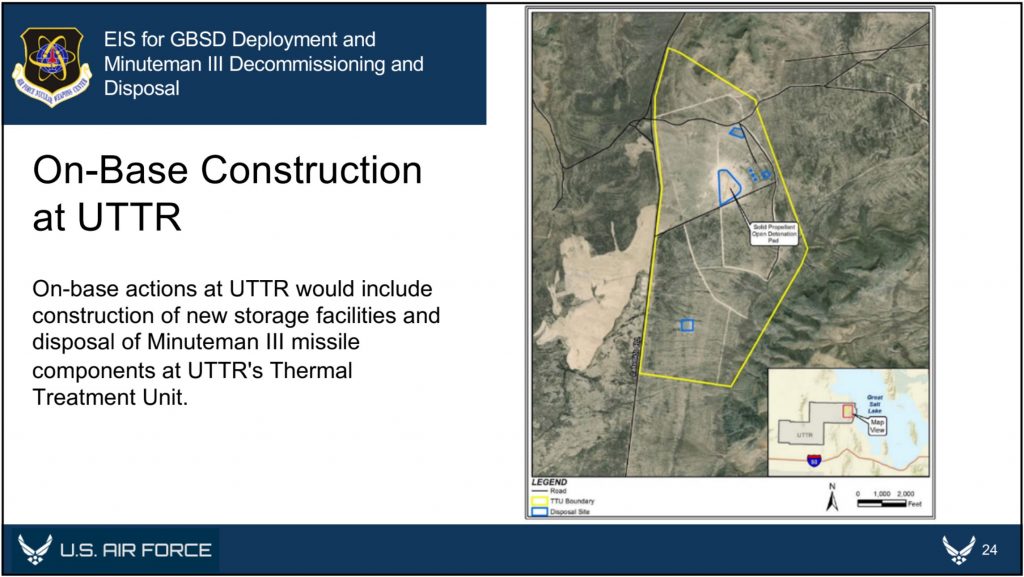

On July 1st, the Air Force published its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed ICBM replacement program, previously known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) and now by its new name, “Sentinel.” The government typically conducts an EIS whenever a federal program could potentially disrupt local water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other related factors.

A comprehensive environmental assessment is certainly warranted in this case, given the tremendous scale of the Sentinel program––which consists of a like-for-like replacement of all 400 Minuteman III missiles that are currently deployed across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, plus upgrades to the launch facilities, launch control centers, and other supporting infrastructure.

Cover page of the Air Force’s July 2022 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the GBSD.

The Draft EIS was anxiously awaited by local stakeholders, chambers of commerce, contractors, residents, and… me! Not because I’m losing sleep about whether Sentinel construction will disturb Wyoming’s Western Bumble Bee (although maybe I should be!), but rather because an EIS is also a wonderful repository for juicy, and often new, details about federal programs––and the Sentinel’s Draft EIS is certainly no exception.

Interestingly, the most exciting new details are not necessarily about what the Air Force is currently planning for the Sentinel, but rather about which ICBM replacement options they previously considered as alternatives to the current program of record. These alternatives were assessed during in the Air Force’s 2014 Analysis of Alternatives––a key document that weighs the risks and benefits of each proposed action––however, that document remains classified. Therefore, until they were recently referenced in the July 2022 Draft EIS, it was not clear to the public what the Air Force was actually assessing as alternatives to the current Sentinel program.

Missile alternatives

The Draft EIS notes that the Air Force assessed four potential missile alternatives to the current plan, which involves designing a completely new ICBM:

- Reproducing Minuteman III ICBMs to “existing specifications” by washing out and refilling the first- and second-stage rocket boosters; remanufacturing the third stages and Propulsion System Rocket Engine––the ICBM’s post-boost vehicle; and refurbishing and replacing all other subsystems;

The Air Force appears to have ultimately eliminated all four of these options from consideration because they did not meet all of their “selection standards,” which included criteria like sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure.

Of particular interest, however, is the Air Force’s note that the Minuteman III reproduction alternative was eliminated in part because it did not “meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs in the context of modern and evolving threats (e.g., range, payload, and effectiveness.” It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade.

This statement also suggests that “modern and evolving threats” are driving the need for an operationally improved ICBM; however, it is unclear what the Air Force is referring to, or how these threats would necessarily justify a brand-new ICBM with new capabilities. As I wrote in my March 2021 report, “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,”

“With respect to US-centric nuclear deterrence, what has changed since the end of the Cold War? China is slowly but steadily expanding its nuclear arsenal and suite of delivery systems, and North Korea’s nuclear weapons program continues to mature. However, the range and deployment locations of the US ICBM force would force the missiles to fly over Russian territory in the event that they were aimed at Chinese or North Korean targets, thus significantly increasing the risk of using ICBMs to target either country. Moreover, […] other elements of the US nuclear force––especially SSBNs––could be used to accomplish the ICBM force’s mission under a revised nuclear force posture, potentially even faster and in a more flexible manner. […] It is additionally important to note that even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload––not the missile itself. By the time that an adversary’s interceptor was able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would have already shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and would be guided solely by its reentry vehicle. Reentry vehicles and missile boosters can be independently upgraded as necessary, meaning that any concerns about adversarial missile defenses could be mitigated by deploying a more advanced payload on a life-extended Minuteman III ICBM.”

Of additional interest is the passage explaining why the Air Force dismissed the possibility of using the Trident II D5 SLBM as a land-based weapon:

“The D5 is a high-accuracy weapon system capable of engaging many targets simultaneously with overall functionality approaching that of land- based missiles. The D5 represents an existing technology, and substantial design and development cost savings would be realized; but the associated savings would not appreciably offset the infrastructure investment requirements (road and bridge enhancements) necessary to make it a land-based weapon system. In addition, motor performance and explosive safety concerns undermine the feasibility of using the D5 as a land-based weapon system.”

The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate. However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests: in 2015 the Navy conducted a successful Trident flight test using “the oldest 1st stage solid rocket motor flown to date” (over 26 years old), with 2nd and 3rd stage motors that were 22 years old. In January 2021, Vice Admiral Johnny Wolfe Jr.––the Navy’s Director for Strategic Systems Programs––remarked that “solid rocket motors, the age of those we can extend quite a while, we understand that very well.” This is largely due to the Navy’s incorporation of nondestructive testing techniques––which involve sending a probe into the bore to measure the elasticity of the propellant––to evaluate the reliability of their missiles.

As a result, the Navy is not currently contemplating the purchase of a brand-new missile to replace its current arsenal of Trident SLBMs, and instead plans to conduct a second life-extension to keep them in service until 2084. However, the Air Force’s comments suggest either a lack of confidence in this approach, or perhaps an institutional preference towards developing an entirely new missile system. [Note: Amy Woolf helpfully offered up another possible explanation, that the Air Force’s concerns could be related to the ability of the Trident SLBM’s cold launch system to perform effectively on land, given that these very different launch conditions could place additional stress on the missile system itself.]

Basing alternatives

The Draft EIS also notes that the Air Force assessed two fascinating––and somewhat familiar––alternatives for basing the new missiles: in underground tunnels and in “deep-lake silos.”

The tunnel option––which had been teased in previous programmatic documents but never explained in detail––would include “locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles”––and it is effectively a mashup of two concepts from the late Cold War.

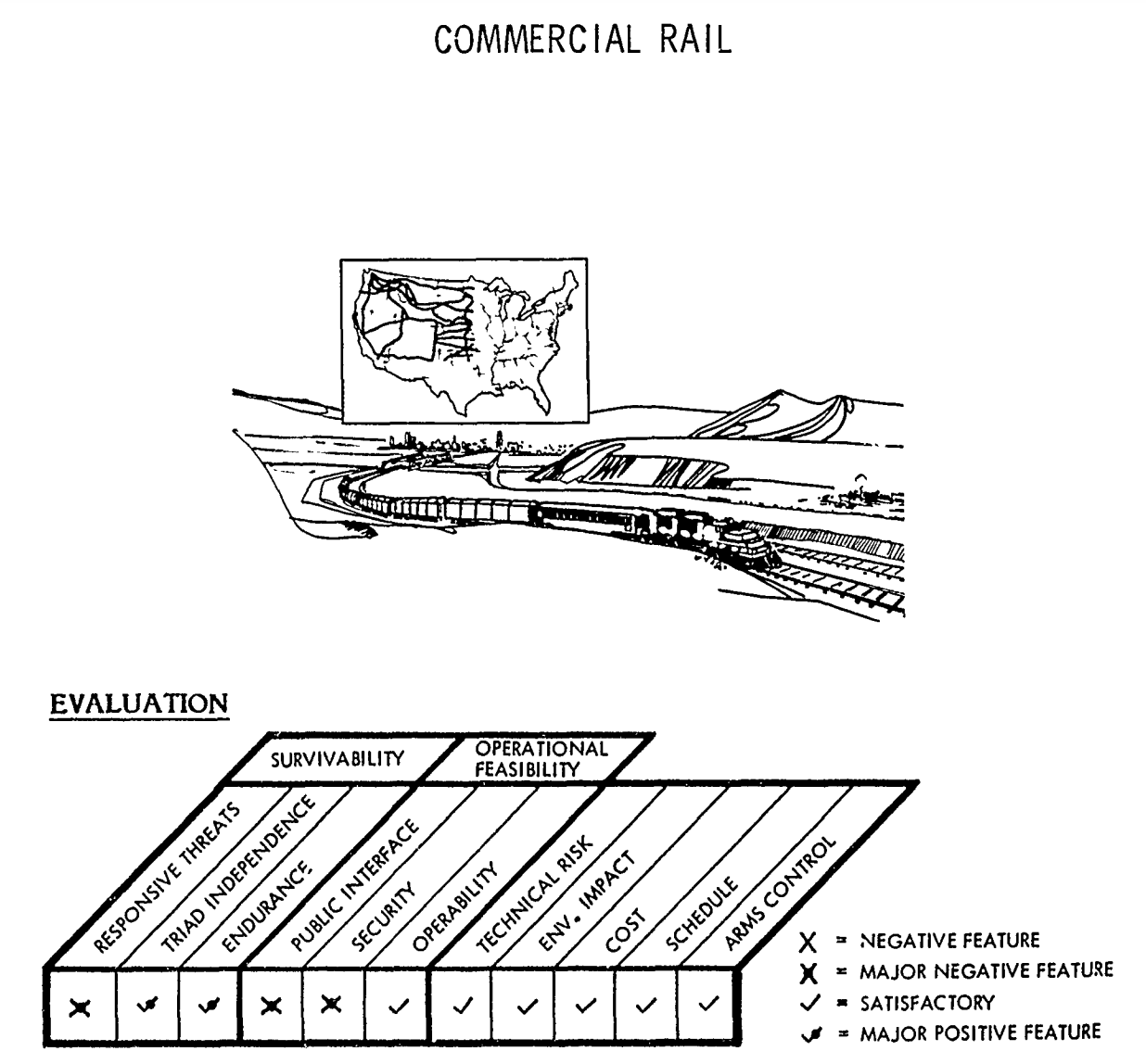

The rail concept was strongly considered during the development of the MX missile in the 1980s, although the plan called for missile trains to be dispersed onto the country’s existing civilian rail network, rather than into newly-built underground tunnels. Both the rail and tunnel concepts were referenced in one of my favourite Pentagon reports––a December 1980 Pentagon study called “ICBM Basing Options,” which considered 30 distinct and often bizarre ICBM basing options, including dirigibles, barges, seaplanes, and even hovercraft!

Illustrations of “Commercial Rail” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

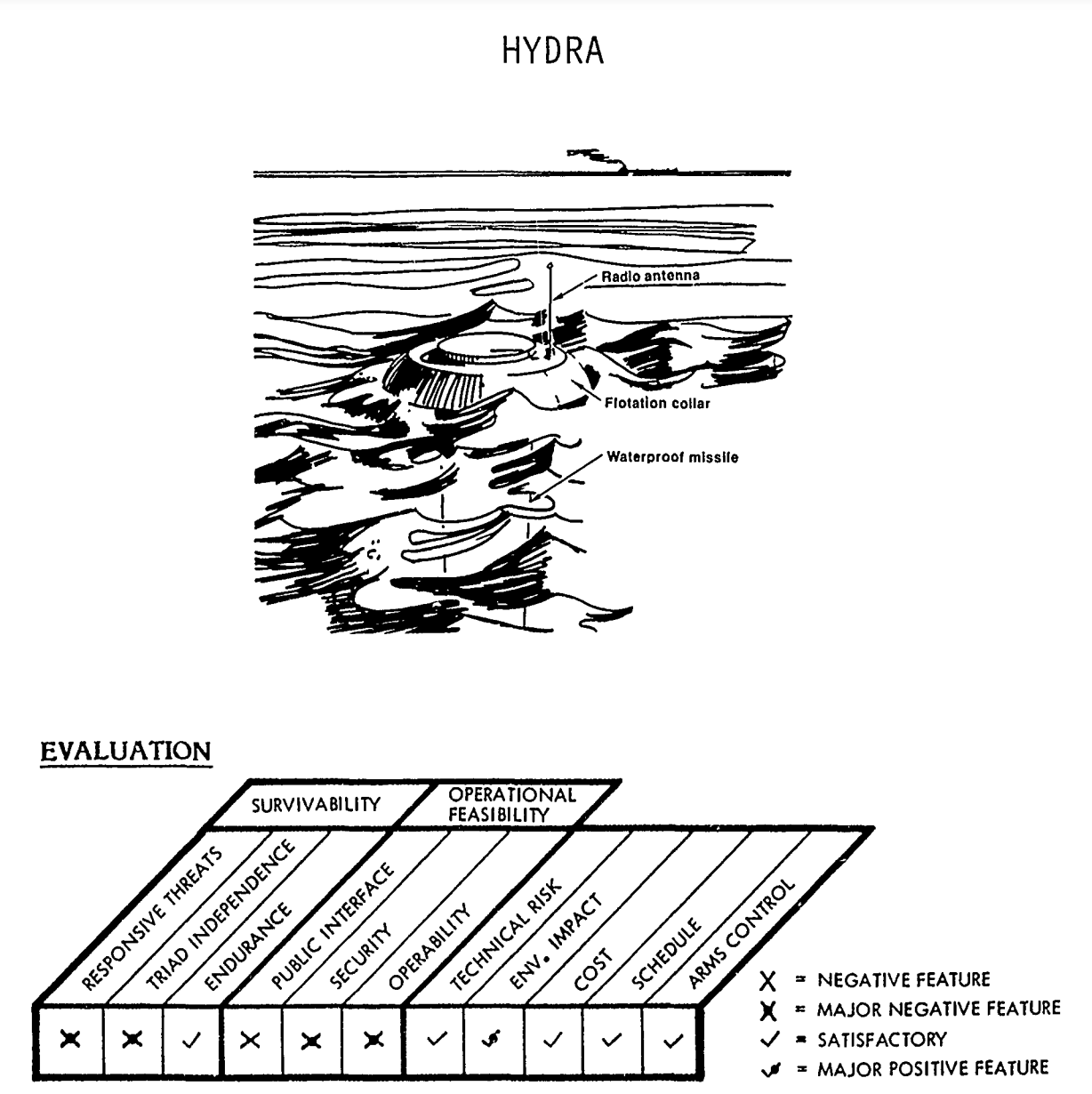

The second option––basing ICBMs in deep-lake silos––was also referenced in that same December 1980 study. The concept––nicknamed “Hydra”––proposed dispersing missiles across the ocean using floating silos, with “only an inconspicuous part of the missile front end [being] visible above the surface.” Interestingly, this raises the theoretical question of whether the Air Force would still maintain control over the ICBM mission, given that the missiles would be underwater.

Illustration of “Hydra” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

When considering alternative basing modes for the Sentinel ICBM, the Air Force eliminated both concepts due to cost prohibitions, and, in the case of underwater basing, a lack of confidence that the missiles would be safe and secure. This concern was also floated in the 1980 study as well, with the Pentagon acknowledging the likelihood that US adversaries and non-state actors “would also be engaged in a hunt for the Hydras. Not under our direct control, any missile can be destroyed or towed away (stolen) at leisure.”

Another potential option?

In addition to revealing these fascinating details about previously considered alternatives to the Sentinel program, the Draft EIS also highlighted a public comment suggesting that “the most environmentally responsible option” would simply be the reduction of the Minuteman III inventory.

The Air Force rejected the comment because it says that it is “required by law to accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground based strategic deterrent program;’” however, the public commenter’s suggestion is certainly a reasonable one. The current force level of 400 deployed ICBMs is not––and has never been––a magic number, and it could be reduced further for a variety of reasons, including those related to security, economics, or a good faith effort to reduce deployed US nuclear forces. In particular, as George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi wrote in a 2021 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, “This assumption that the ICBM force would not be eliminated or reduced before 2075 is difficult to reconcile with U.S. disarmament obligations under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.”

The security environment of the 21st century is already very different than that of the previous century. The greatest threats to Americans’ collective safety are non-militarized, global phenomena like climate change, domestic unrest and inequality, and public health crises. And recent polling efforts by ReThink Media, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Federation of American Scientists suggest that Americans overwhelmingly want the government to invest in more proximate social issues, rather than on nuclear weapons. To that end, rather than considering building new missile tunnels, it would likely be much more domestically popular to spend money on domestic priorities––perhaps new subway tunnels?

—

Background Information:

- “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,” Federation of American Scientists (Mar. 2021)

- “Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan,” Federation of American Scientists (Nov. 2020)

- ICBM Information Project, Federation of American Scientists

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and Longview Philanthropy. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

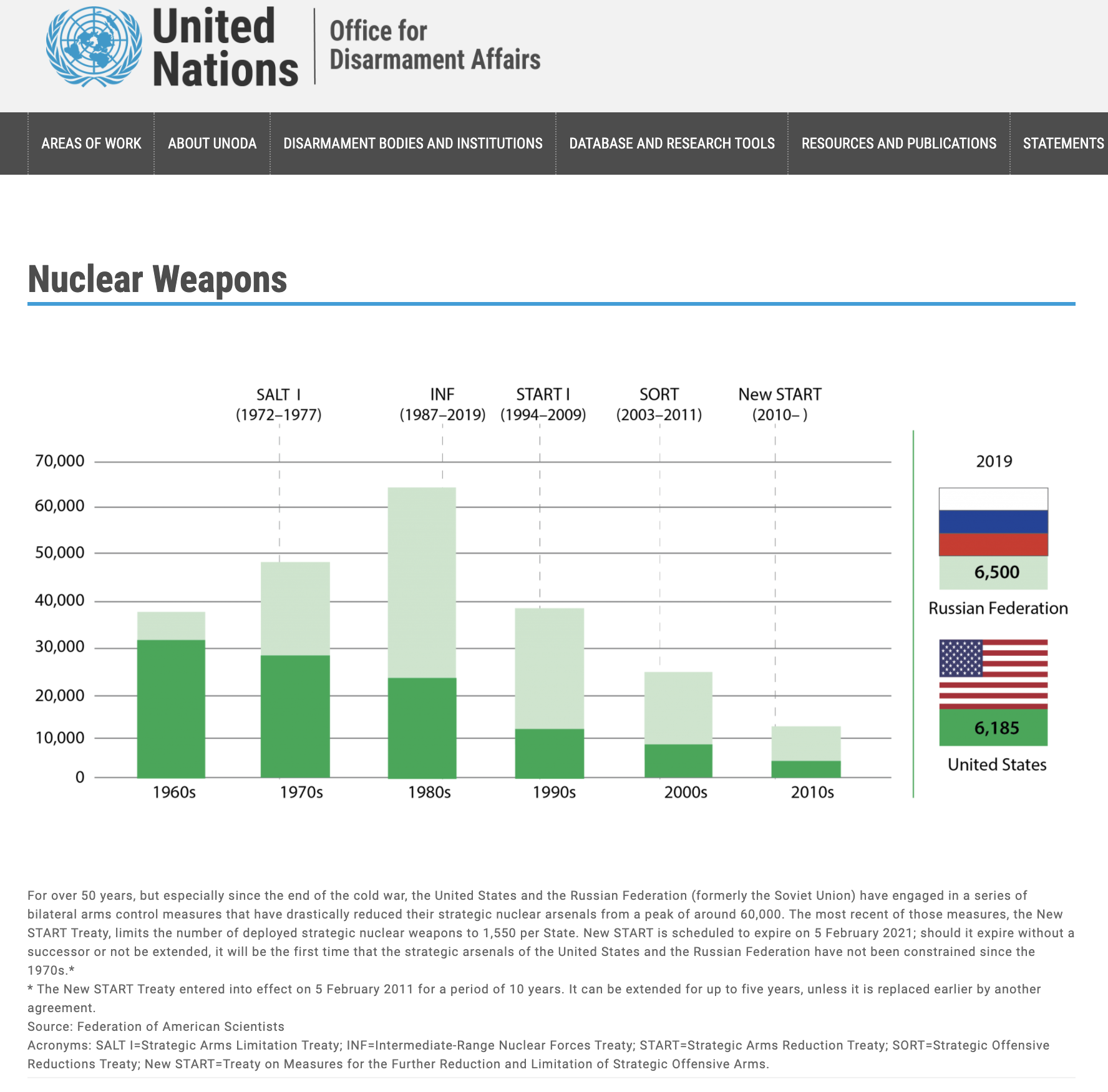

Amidst Nuclear Saber Rattling, New START Treaty Demonstrates Importance

Shortly after Russian military forces invaded Ukraine and President Vladimir Putin said that he had ordered Russian nuclear forces on high combat alert – apparently to deter the United States from getting directly involved, and the United States condemned the statement as “unacceptable” nuclear saber rattling but refused to respond in kind, the two vehemently opposed countries did something amazing: They exchanged factual information about the status of their strategic nuclear forces as required under the New START Treaty.

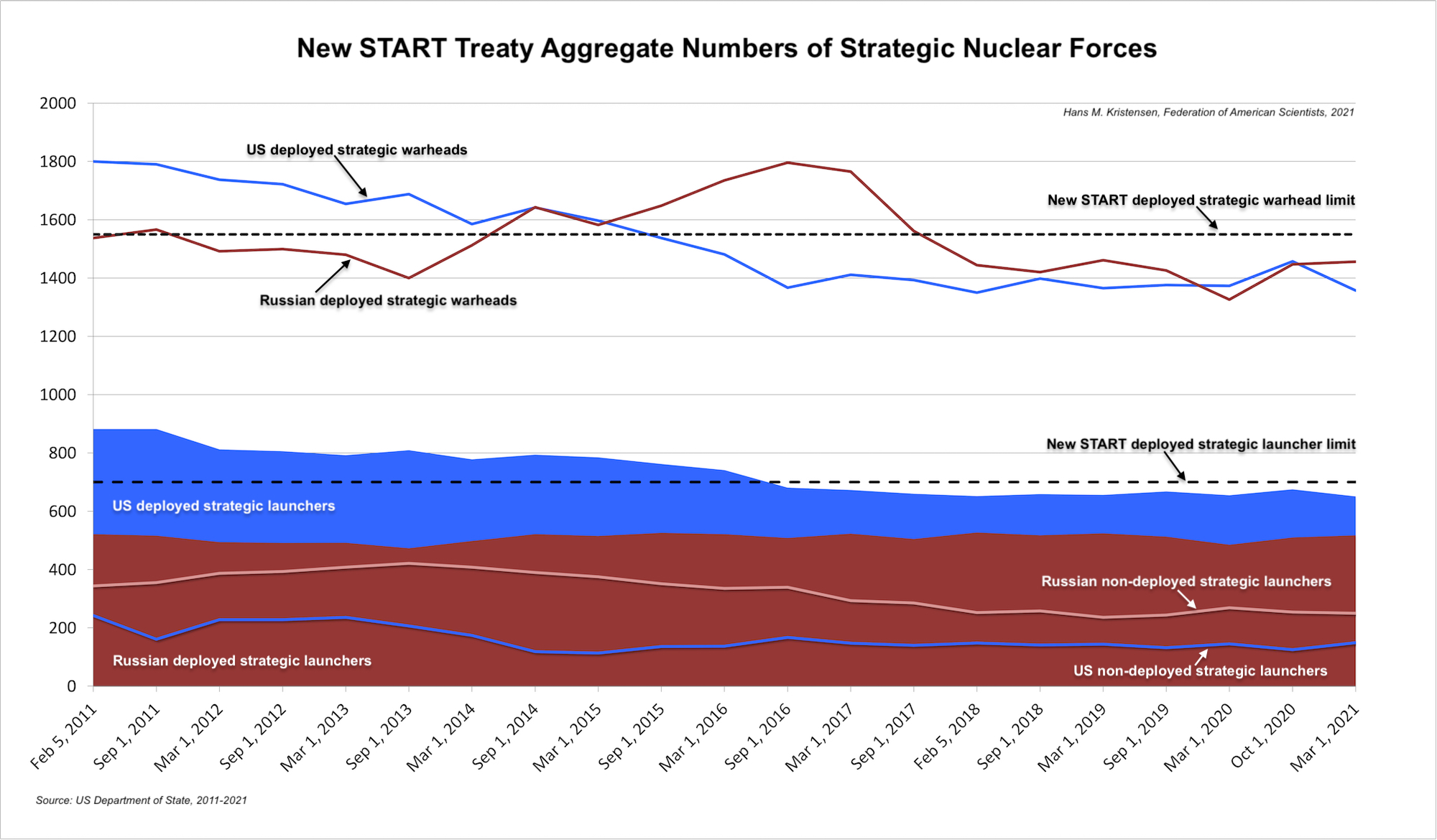

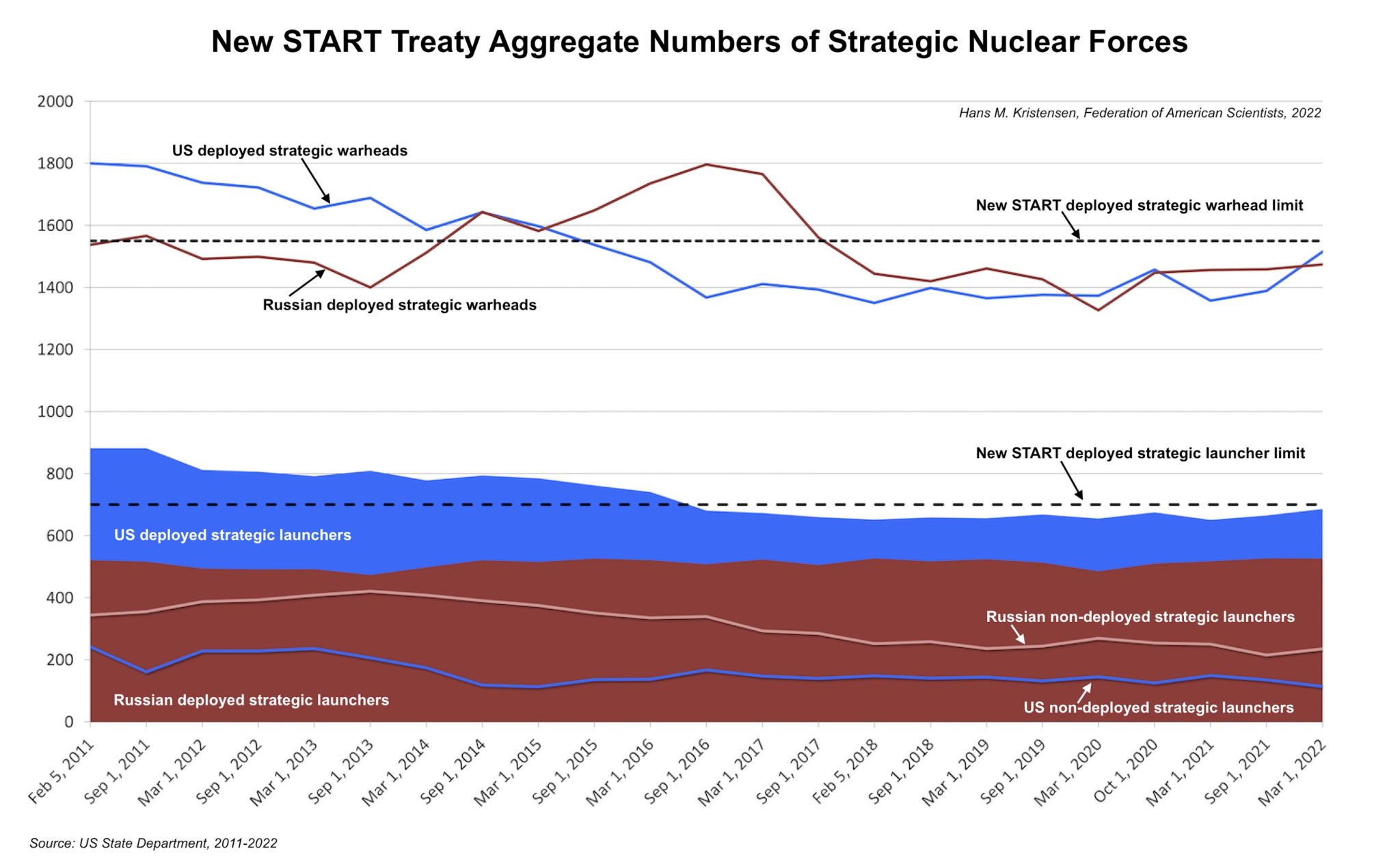

Yesterday, the US State Department published the unclassified bits of that data exchange. It shows that both countries were below the limits set by the treaty for deployed strategic nuclear forces: 1,550 warheads attributed to 700 deployed long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers.

At a time when direct contacts are being curtailed, antagonism runs high, and trust completely lost, it is nothing short of amazing that Russia and the United States continue to abide by the New START treaty and exchange classified information as if nothing had happened.

The reason is clear. Despite their differences, they both have a keen interest in keeping the other country’s long-range nuclear forces in check.

Both the United States and Russia have far more nuclear warheads in their total military stockpiles than what they deploy on their launchers under New START. If the treaty fell away, each side could dramatically and quickly increase the number of nuclear warheads ready to launch on short notice. The US has close to 2,000 strategic warheads in storage, Russia about half that many. Such an increase would be extraordinarily destabilizing and dangerous, especially with a full-scale war raging in Europe and Russia buckling under the strain of unprecedented sanctions.

What the Data Shows

The latest set of data shows that as of March 1, 2022, the United States and Russia both were in compliance with their obligations under the New START treaty not to operate more than 800 total strategic launchers, no more than 700 deployed strategic launchers, and no more than 1,550 warheads attributed to those deployed launchers.

Combined the two countries possessed a total of 1,561 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,212 launchers were deployed with 2,989 attributable warheads. That is a slight increase in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2021, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 19, increased combined deployed strategic launchers by 20, and increased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 142. Of these numbers, only the “19” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 combined have cut 428 strategic launchers from their arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 191, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 348. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (just over 4 percent) of the estimated 8,185 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (just over 3 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 11,405 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States possessing 800 strategic launchers, exactly the maximum number allowed by the treaty, of which 686 are deployed with 1,515 warheads attributed to them. This is an increase of 21 deployed strategic launchers and 126 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. The increase is probably partly due to the 13th SSBN – the USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) – having completed its reactor refueling overhaul. The 1,515 deployed warheads is the highest number the United States has deployed since September 2015. The total inventory of strategic launchers has not declined since 2017.

The aggregate data does not reveal how many warheads are attributed to the three legs of the triad. The full unclassified data set will be released later this summer. But if one assumes the number of deployed bombers and deployed ICBMs are the same as in the September 2021 data, then the SSBNs carry 1,068 warheads on roughly 220 deployed Trident II SLBMs. That is an increase of 123 warheads on the SSBN force compared with September, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for roughly 70 percent of all the 1,515 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 73 percent if excluding the “fake” 45 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data indicates that the United States as of March 1, 2022 deployed approximately 1,068 warheads on ballistic missile onboard its strategic submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 196, and deployed strategic warheads by 285. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 8 percent) of the estimated 3,708 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (just over 5 percent if counting total inventory of 5,428 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 761 strategic launchers, of which 526 are deployed with 1,474 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is a decrease of 1 deployed launcher and an increase of 16 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its total inventory of strategic launchers by 104, increased deployed launchers by 5, and decreased deployed strategic warheads by 63. This modest warhead reduction represents less than 2 percent of the estimated 4,477 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (roughly 1 percent if counting the total inventory of 5,977 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian New START reductions since 2011 are smaller than the US reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force.

That disparity remains today. Despite frequent claims by hardliners that Russia is ahead of the United States, the New START data shows that Russia has 160 deployed strategic launchers fewer than the United States, a significant gap that exceeds the number of missiles in an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. Despite its nuclear modernization program, Russia has so far not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by about one-third since its lowest point in February 2018.

Instead of closing the launcher gap, the Russian military appears to try to compensate by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles (SS-27 Mod 2, Yars, and SS-N-32, Bulava) that are replacing older types (SS-25, Topol, SS-N-18, Vysota, and SS-N-23, Sineva). Thanks to the New START treaty limit, many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but are stored and could potentially be uploaded onto the launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (SS-19 Mod 4, Avangard, and SS-29, Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types (the Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered ground-launched cruise missile) are not yet deployed and appear to be planned in relatively small numbers. They do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types, if the two sides agree.

The sanctions in reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely slow Russia’s nuclear modernization in the next decade.

Inspections and Notifications

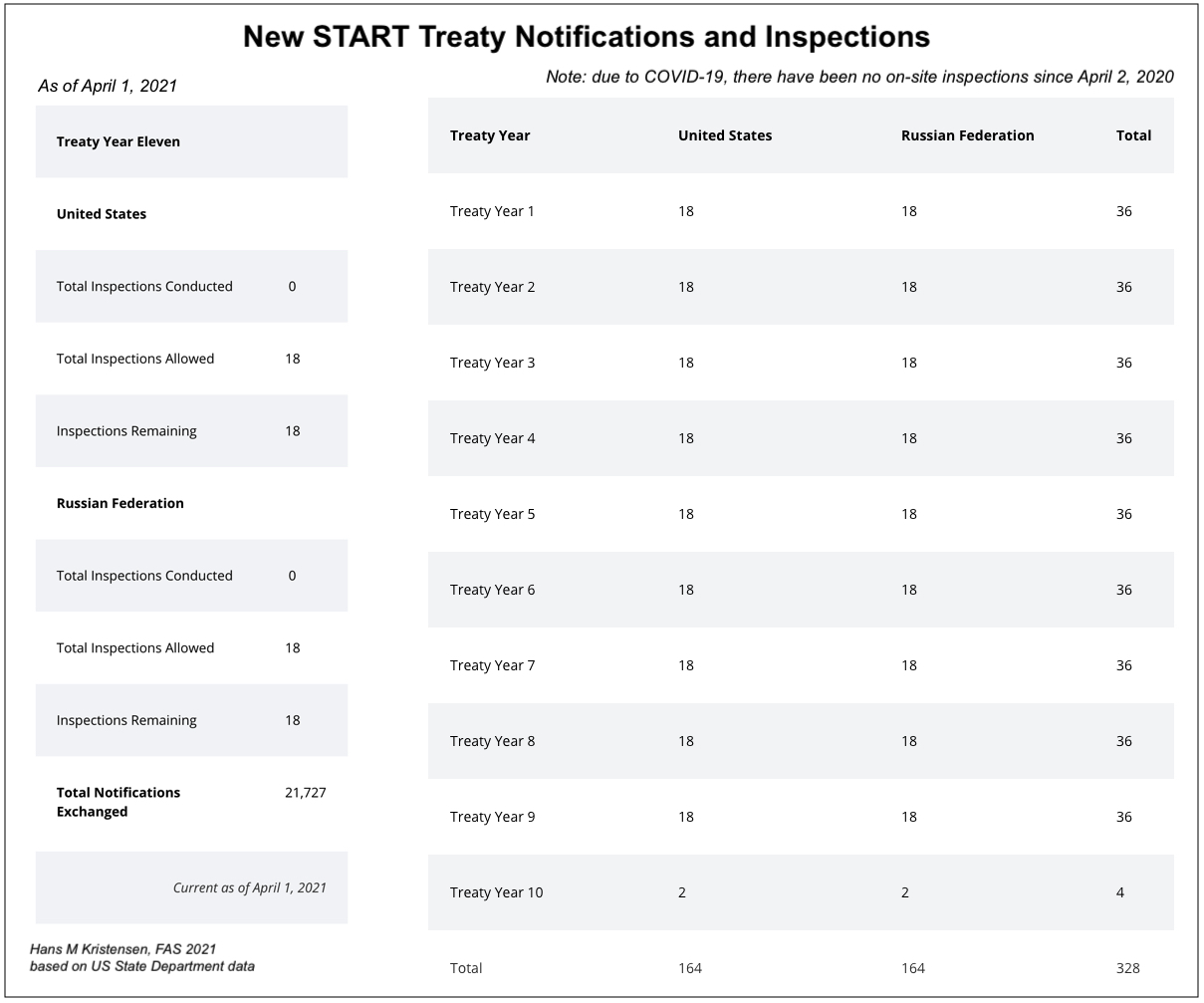

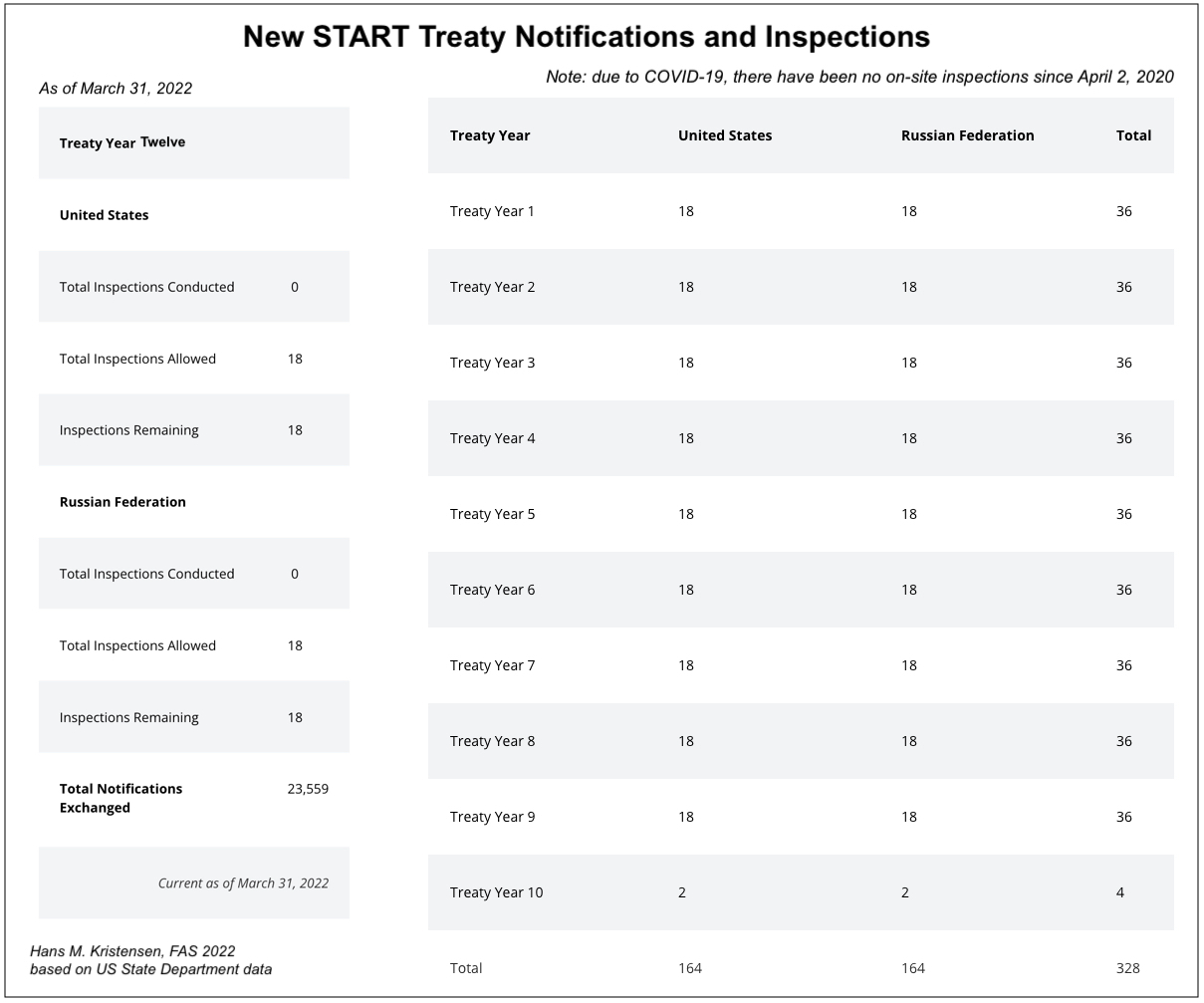

In addition to the aggregate data described above, the New START treaty also allows for up to 18 on-site inspections per year and notifications of launcher movements and activities. Up until April 2020, a total of 328 on-site inspections were conducted. Because of COVID-19, there have been no inspections since. The two countries have continued to exchange large numbers of notifications: a total of 23,559 as of March 31, 2022.

Looking Ahead

The continued complaince by the United States and Russia to the New START treaty and its data exchanges are extraordinary given the demise of treaties, agreements, and deep animosity and almost complete loss of trust. The treaty’s interactions between the two countries and the caps and predictability it provides on strategic offensive nuclear forces have never been more important since New START was negotiated more than a decade ago.

But the clock is running out. Although New START was extended in February 2021 for an additional five years, the treaty will expire in February 2026. Strategic stability talks between Russia and the United States have been disrupted by the war in Ukraine and seem unlikely to resume in the foreseeable future.

If New START is not followed by a new treaty by the time it expires in 2026, there will no limits on US and Russian nuclear forces for the first time the 1970s.

Moreover, political polarization makes it highly uncertain if the US Congress would approve a new treaty.

Short of a formal treaty, the two sides potentially could make an executive agreement and pledge to continue to abide by the New START limits even after the treaty officially expires.

The silver lining is that both countries have a strong interest in continuing to maintain limits on the other side’s strategic offensive nuclear forces. That is why it is important that hardliners are not allowed to misuse Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s nuclear buildup to undermine New START and increase nuclear forces.

Additional information:

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

- Russian nuclear forces, 2022

- United States nuclear forces, 2021 [2022 version forthcoming]

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Flying Under The Radar: A Missile Accident in South Asia

A crashed Indian missile inside Pakistani territory. Image: Pakistan Air Force.

With all eyes turned towards Ukraine these past weeks, it was easy to miss what was almost certainly a historical first: a nuclear-armed state accidentally launching a missile at another nuclear-armed state.*

On the evening of March 9th, during what India subsequently called “routine maintenance and inspection,” a missile was accidentally launched into the territory of Pakistan and impacted near the town of Mian Channu, slightly more than 100 kilometers west of the India-Pakistan border.

Because much of the world’s attention has understandably been focused on Eastern Europe, this story is not getting the attention that it deserves. However, it warrants very serious scrutiny––not only due to the bizarre nature of the accident itself, but also because both India’s and Pakistan’s reactions to the incident reveal that crisis stability between South Asia’s two nuclear rivals may be much less stable than previously believed.

The Incident

Using official statements and open-source clues, it is possible to piece together a relatively complete picture of what took place on the evening of March 9th.

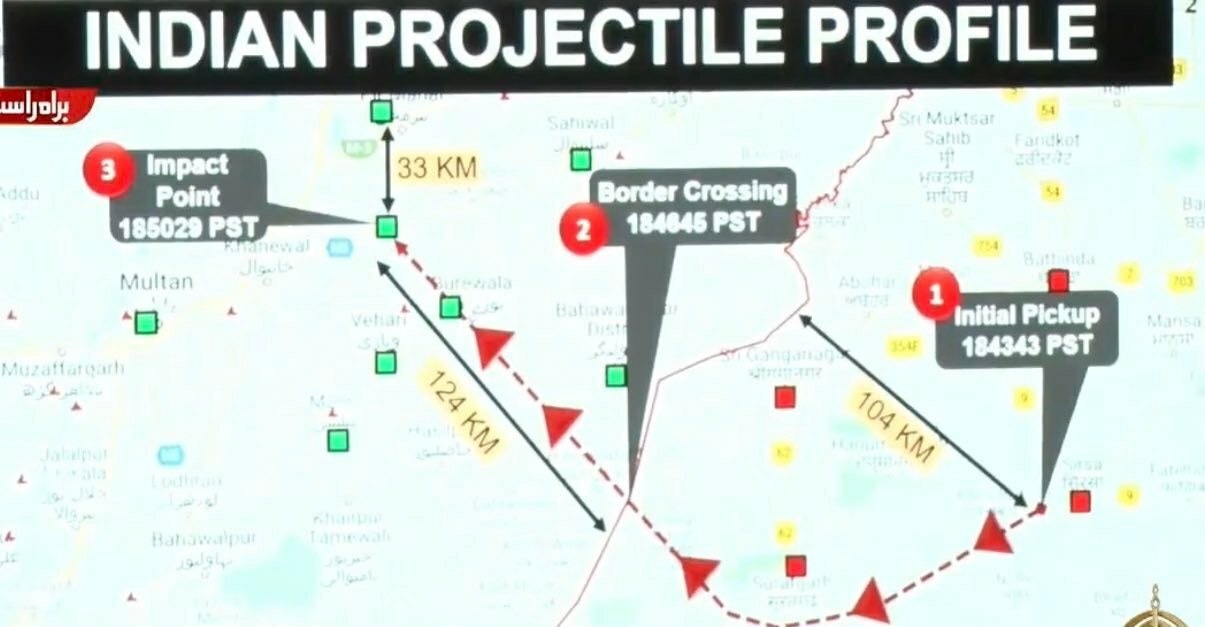

At 18:43:43 Pakistan Standard Time (19:13:43 India Standard Time), the Pakistan Air Force picked up a “high-speed flying object” 104 kilometers inside Indian territory, near Sirsa, in the state of Haryana. According Air Vice Marshal Tariq Zia––the Director General Public Relations for the Pakistan Air Force––the object traveled in a southwesterly direction at a speed between Mach 2.5 and Mach 3. After traveling between 70 and 80 kilometers, the object turned northwest and crossed the India-Pakistan border at 18:46:45 PKT. The object then continued on the same northwesterly trajectory until it crashed near the Pakistani town of Mian Channu at 18:50:29 PKT.

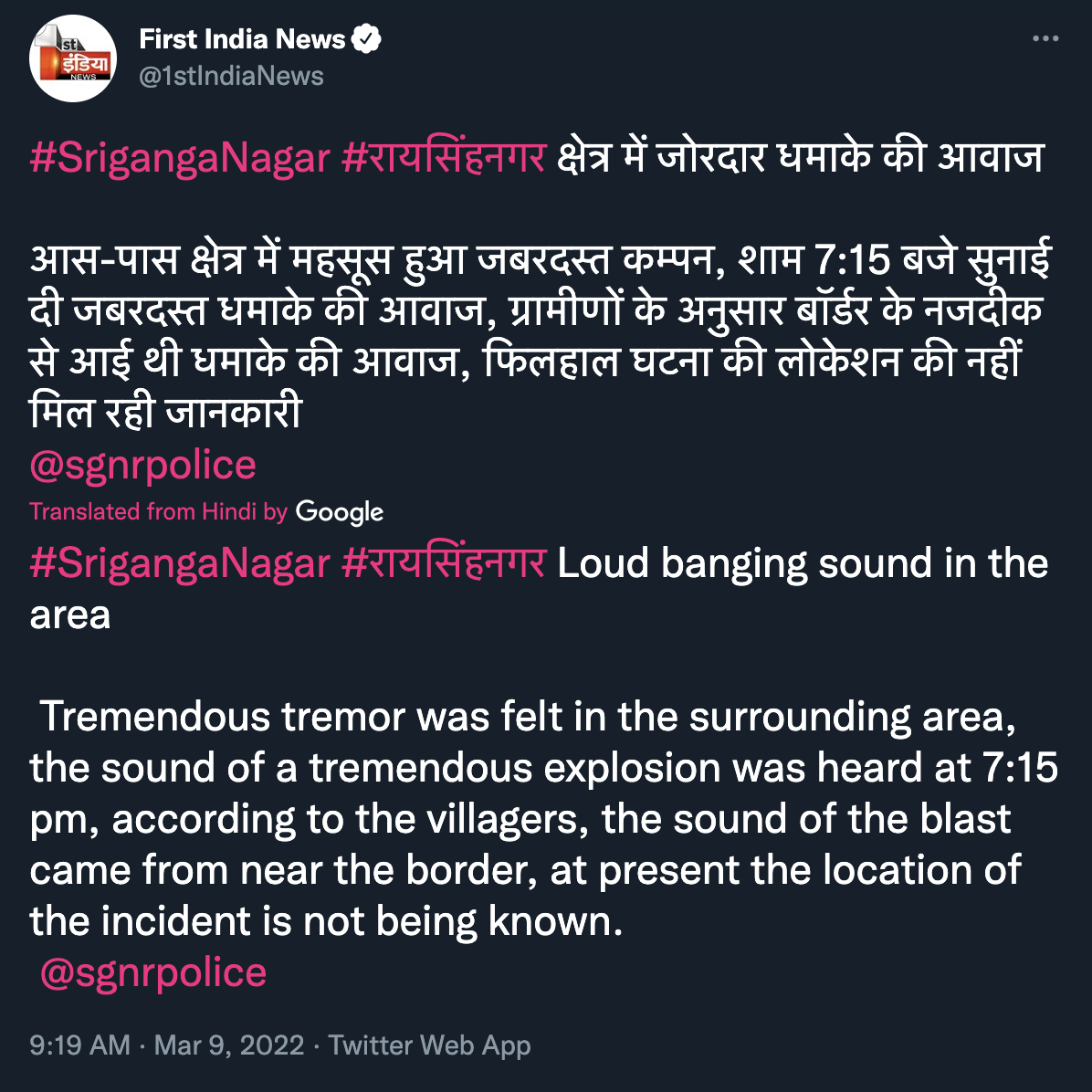

Tweet from @1stIndiaNews indicating that a “tremendous explosion” was heard at approximately 19:15 IST at the city of Sri Ganganagar near the India-Pakistan border. This time and location adds a data point to interpreting the flight path of the missile.

According to Pakistani military officials in a March 10th press conference, 3 minutes and 46 seconds of the object’s total flight time of 6 minutes and 46 seconds were within Pakistani airspace, and the total distance traveled inside of Pakistan was 124 kilometers.

Annotated map of the missile’s flight path provided by Pakistani military officials to media on 10 March 2022.

In a press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that the object was “certainly unarmed” and that no one was injured, although noted that it damaged “civilian property.”

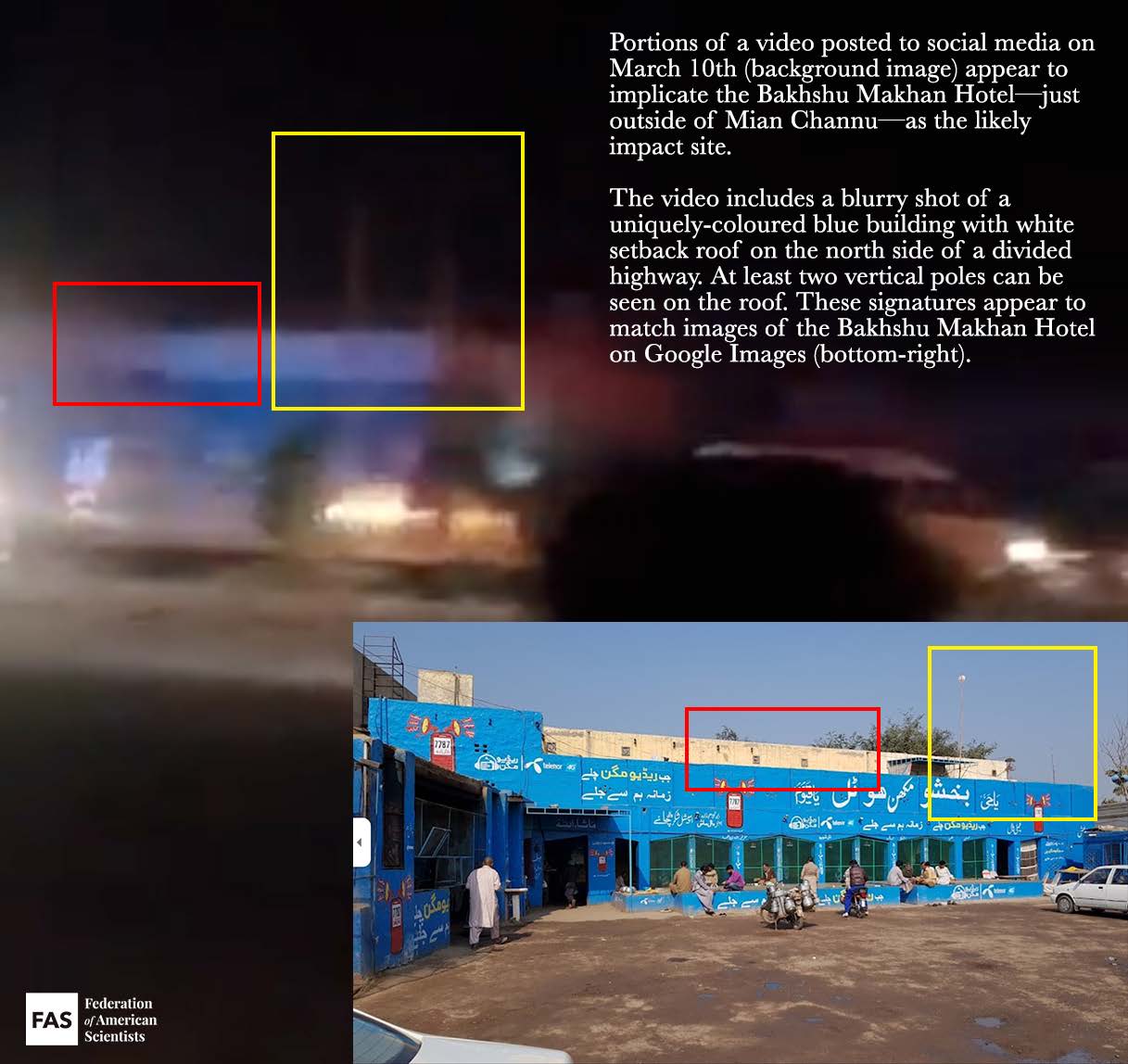

Although the crash site has not been confirmed and official photos include very few useful visual signatures, observation of local civilian social media activity indicates that a likely candidate is the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel, just outside of Mian Channu (30°27’6.40″N, 72°24’10.87″E). One video of the crash site posted to Twitter includes a shot of a uniquely-colored blue building with a white setback roof on the other side of a divided highway. At least two vertical poles can be seen on the roof of the building. All of these signatures appear to match those included in images of the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel in Google Images.

The video’s caption suggests that the object that crashed was an “army aviation aircraft drone;” however, Pakistani military officials subsequently reported that the object was an Indian missile. Neither Pakistan nor India has publicly confirmed what type of missile it was; however, in a March 10th press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that “we can so far deduce that it was a supersonic missile––an unknown missile––and it was launched from the ground, so it was a surface-to-surface missile.”

This statement, in addition to photos of the debris and other official details relating to range, speed, altitude, and flight time of the object, suggest that it was very likely a BrahMos cruise missile.

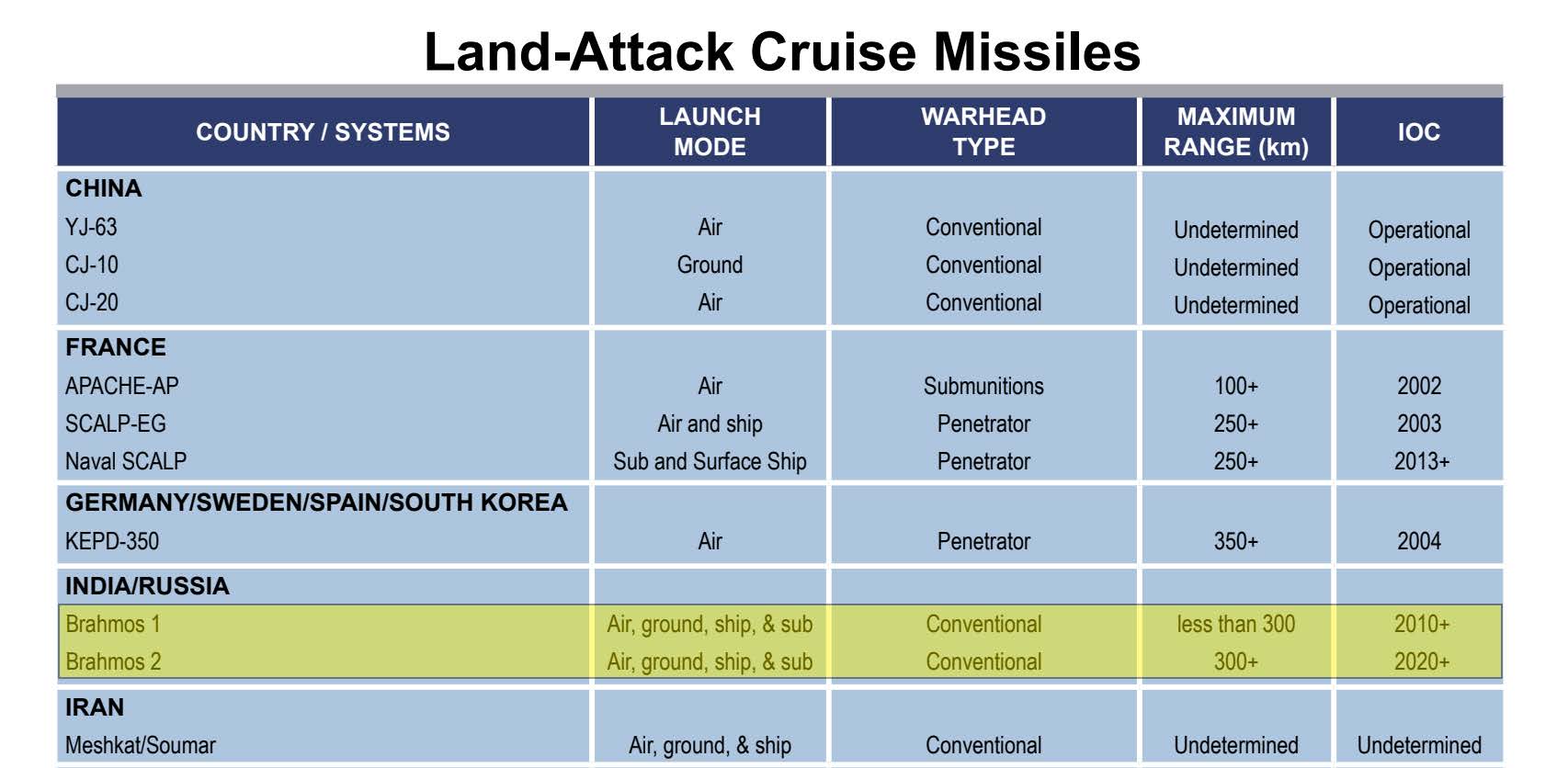

BrahMos is a ramjet-powered, supersonic cruise missile co-developed with Russia, that can be launched from land, sea, and air platforms and can travel at a speed of approximately March 2.8. The US National Air and Space Intelligence Centre (NASIC) suggested that an earlier version of BrahMos had a range of “less than 300” kilometers, but the Indian Ministry of Defence recently announced on 20 January 2022 that it had extended the BrahMos’ range, with defence sources saying that the missile could now travel over 500 kilometres. The reported speed of the “high-speed flying object,” as well as the distance traveled, matches the publicly-known capabilities of the BrahMos cruise missile.

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s 2017 Ballistic and Cruise Missile report lists two versions of the BrahMos missile as “conventional.”

Although many Indian media outlets often describe the BrahMos as a nuclear or dual-capable system, NASIC lists it as “conventional,” and there is no public evidence to indicate that the missile can carry nuclear weapons.

India has launched a Court of Inquiry to determine how the incident occurred; however, the Indian government has otherwise remained tight-lipped on details. In the absence of official statements, small snippets have trickled out through Indian and Pakistani media sources––prompting several questions that still need answers.

How did the missile get “accidentally” launched?

According to the Times of India, an audit was being conducted by the Indian Air Force’s Directorate of Air Staff Inspection at the time of the launch. As part of that audit, or possibly as part of a separate exercise, it appears that target coordinates––including mid-flight waypoints––were fed into the missile’s guidance system. According to Indian defence sources, in order to launch the BrahMos, the missile’s mechanical and software safety locks would also have had to be bypassed and the launch codes would have had to be entered into the system.

The BrahMos does not appear to have a self-destruct mechanism. As a result, once the missile was launched, there was no way to abort.

Given that defence sources indicate that the missile “was certainly not meant to be launched,” it still remains unclear whether the launch was due to human or technical error. On March 11th, in its first public statement about the incident, the Indian government stated that “a technical malfunction led to the accidental firing of a missile.” However, since the formal convening of a Court of Inquiry, the government has since changed its rhetoric, with Indian officials stating that “the accidental firing took place because of human error. That’s what has emerged at this stage of the inquiry. There were possible lapses on the part of a Group Captain and a few others.” Tribute India reports that there are currently four individuals under investigation.

While this is certainly a plausible explanation for the incident, it is also worth noting that the Indian government would be financially incentivized to emphasize the human error narrative over a technical malfunction narrative. On January 28th, India concluded a $374.96 million deal with the Philippines to export the BrahMos––a deal which amounts to the country’s largest defence export contract. Additional BrahMos exports will be crucial for India to meet its ambitious defence export targets by 2025, and the negative publicity associated with a possible BrahMos technical malfunction could significantly hinder that goal.

Did Pakistan track the missile correctly?

In a press conference on March 10th, Pakistani military officials noted that Pakistan’s “actions, response, everything…it was perfect. We detected it on time, and we took care of it.” However, Indian military officials have publicly disputed Pakistan’s interpretation of the missile’s flight path. Pakistan announced on March 10th that the missile was picked up near Sirsa; however, Indian officials subsequently stated that the missile was launched from a location near Ambala Air Force Station, nearly 175 kilometers away. India’s explanation is likely to be more accurate, given that there is no known BrahMos base near Sirsa, but there is one near Ambala (h/t @tinfoil_globe). Indian defence sources have also suggested that the map of the missile’s perceived trajectory that the Pakistani military released on March 10th was incorrect.

Annotated Google Earth image showing the 175 kilometer distance between the likely launch site and Pakistan’s radar pickup.

Furthermore, Pakistani officials announced on March 10th that the missile’s original destination was likely to be the Mahajan Field Firing Range in Rajasthan, before it suddenly turned and headed northwest into Pakistan. However, Indian defence sources have since suggested that the missile was not actually headed for the Mahajan Field Firing Range, but instead was “follow[ing] the trajectory that it would have in case of a conflict, but ‘certain factors’ played a role in ensuring that any pre-fed target was out of danger.” Given that the impact site was not near any critical military or political infrastructure, this could suggest that the cruise missile had its wartime mid-flight trajectory waypoints pre-loaded into the system, but its actual target had not yet been selected. If this is the case, then this targeting practice would be similar in nature to how some other nuclear-armed states target their missiles at the open ocean during peacetime––precisely in case of incidents like this one. Although the missile still landed on Pakistani territory, the fact that it did not hit any critical targets prevented the crisis from escalating. It is worth noting, however, that this would certainly not be the case if the missile had actually injured or killed anyone.

During the March 10th press conference, Pakistani officials noted that the Pakistan Air Force did not attempt to shoot down the missile because “the measures in place in times of war or in times of escalation are different [from those] in peace time.” However, India’s challenges to Pakistan’s narrative also raise significant questions about whether the Pakistan Air Force was able to accurately track the missile correctly. If not, then this raises the possibility of miscalculation or miscommunication, and crisis stability would be seriously eroded if a similar situation occurred during a time of heightened tensions.

Were any civilian aircraft put in danger?

In its public statements, Pakistan has emphasized that the accidental missile launch could have put civilian flights in danger, as India did not issue a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) prior to launch. Governments typically issue NOTAMs in conjunction with missile tests, in order to inform civilian aircraft to avoid a particular patch of airspace during the launch window. Given that India did not issue one, a time-lapse video prepared by Flightradar24 showed that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch. The video erroneously suggests that the missile traveled in a straight line from Ambala to Mian Channu, when it appears to have dog-legged in mid-flight; however, the video is still a useful resource to demonstrate how crowded the skies were at the time of the accident.

A screenshot of a video prepared by Flightradar24, showing that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch.

Why was India’s response so poor?

Given the seriousness of the incident, India’s delayed response has been particularly striking. Immediately following the accidental launch, India could have alerted Pakistan using its high-level military hotlines; however, Pakistani officials stated that it did not do so. Additionally, India waited two days after the incident before issuing a short public statement.

India’s poor response to this unprecedented incident has serious implications for crisis stability between the two countries. According to DNA India, in the absence of clarification from India, Pakistan Air Force’s Air Defence Operations Centre immediately suspended all military and civilian aircraft for nearly six hours, and reportedly placed frontline bases and strike aircraft on high alert. Defence sources stated that these bases remained on alert until 13:00 PKT on March 14th. Pakistani officials appeared to confirm this, noting that “whatever procedures were to start, whatever tactical actions had to be taken, they were taken.”

We were very, very lucky

Thankfully, this incident took place during a period of relative peacetime between the two nuclear-armed countries. However, in recent years India and Pakistan have openly engaged in conventional warfare in the context of border skirmishes. In one instance, Pakistani military officials even activated the National Command Authority––the mechanism that directs the country’s nuclear arsenal––as a signal to India. At the time, the spokesperson of the Pakistan Armed Forces not-so-subtly told the media, “I hope you know what the NCA means and what it constitutes.”

If this same accidental launch had taken place during the 2019 Balakot crisis, or a similar incident, India’s actions were woefully deficient and could have propelled the crisis into a very dangerous phase.

Furthermore, as we have written previously, in recent years India’s rocket forces have increasingly worked to “canisterize” their missiles by storing them inside sealed, climate-controlled tubes. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis.

This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

India’s recent missile accident––and the deficient political and military responses from both parties––suggests that regional crisis instability is less stable than previously assumed. To that end, this crisis should provide an opportunity for both India and Pakistan to collaboratively review their communications procedures, in order to ensure that any future accidents prompt diplomatic responses, rather than military ones.

Background Information:

- “Indian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August 2020.

- “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept/Oct 2021.

- “India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, Dec 2021.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This article was made possible with generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

*[Note: This type of missile accident has apparently happened before; on 11 September 1986, a Soviet missile flew more than 1,500 off-course and landed in China. Thank you to the excellent Stephen Schwartz for the historical reference.]

Categories: Arms Control, ballistic missiles, Deterrence, Disarmament, India, Nuclear Weapons, Pakistan

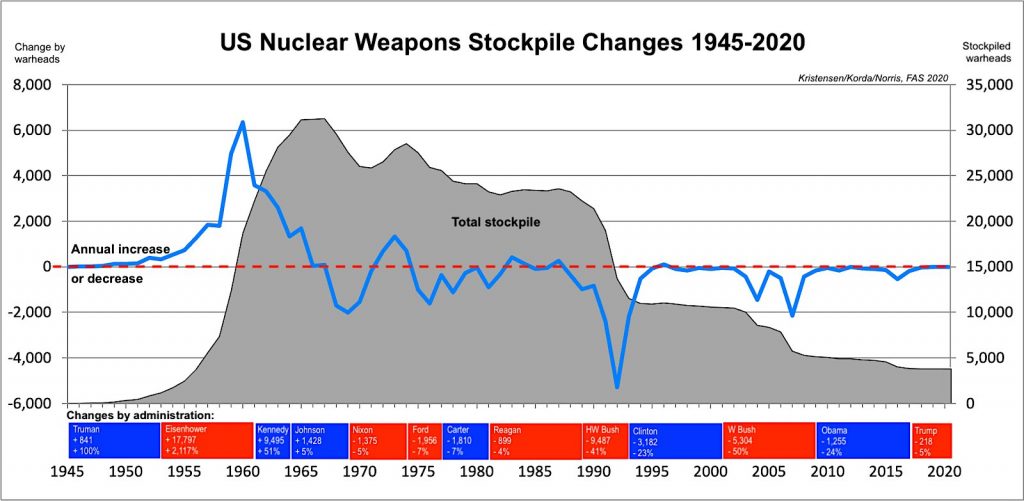

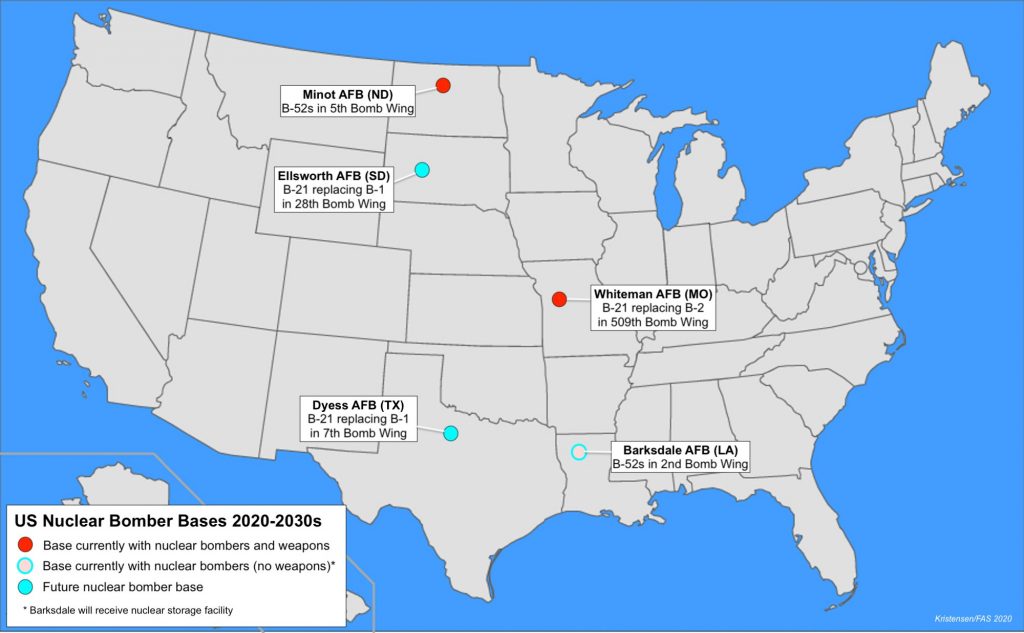

After Trump Secrecy, Biden Administration Restores US Nuclear Weapons Transparency

[Updated] The Biden administration yesterday afternoon declassified the number of nuclear weapons the United States possesses. The act reverses the secrecy of the Trump administration, which denied release of the number for three years, and restores the nuclear transparency of the Obama administration.

FAS’ Steve Aftergood asked for this information in March 2021. We have still not received an official response.

Although a victory for nuclear transparency, the data shows only very limited nuclear weapons reductions in recent years – a stark reminder of the international nuclear climate, domestic policies, and that a lot more work is needed to reduce nuclear dangers.

Stockpile Numbers

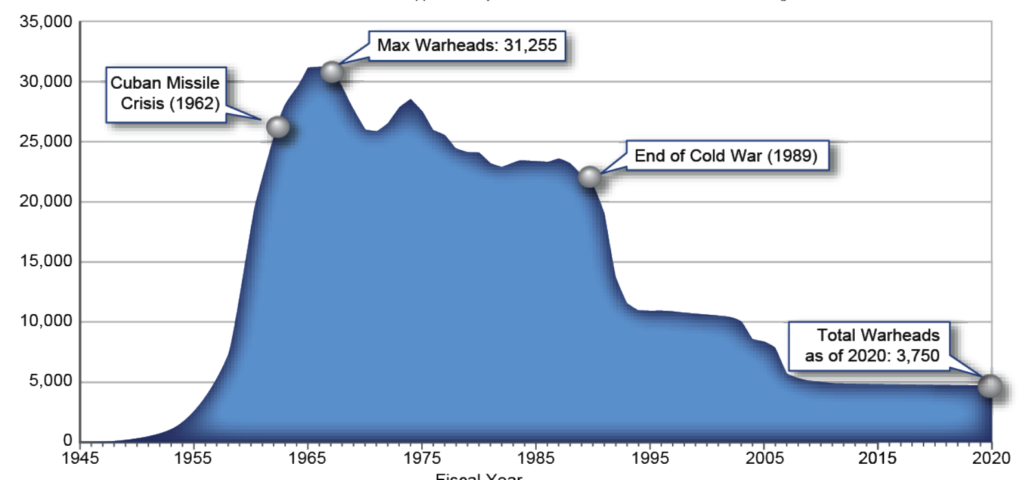

According to the new data, the United States possessed a total of 3,750 nuclear warheads in the Department of Defense nuclear weapons stockpile as of September 2020. That number is only 50 warheads less than our estimate of 3,800 warheads from early this year.

The 3,750-warhead number is only 72 warheads fewer than in September 2017, the last number made available before the Trump administration closed the books.

That reduction is by any measure mediocre. In its announcement about the new stockpile numbers, the US Department of State highlights that the current stockpile of 3,750 warheads “represents an approximate 88 percent reduction in the stockpile from its maximum (31,255) at the end of fiscal year 1967, and an approximate 83 percent reduction from its level (22,217) when the Berlin Wall fell in late 1989.” While that is true and an amazing accomplishment, the fact remains that the vast majority of that reduction happened in two phases during the H.W. Bush and W. Bush administrations. Since 2008 the reduction has been slow and limited. The trend is that the reduction is decreasing and leveling out.

A peculiar revelation in the new data is that it shows that the stockpile increased by 20 warheads between September 2018 and September 2019 when Trump was in office. The increase is not explained but one possibility is that it reflects the production of the new W76-2 low-yield warhead that the Trump administration rushed into production in response to what it said was Russia’s plans for first-use of tactical nuclear weapons. The first W76-2 was produced in February 2019, NNSA was scheduled to deliver all the warheads by end of Fiscal Year 2019, but the W76-2 wasn’t completed until June 2020. Arkin and Kristensen reported in January 2020 that the first W76-2s had been deployed, which was later confirmed by the Pentagon.

It is possible (but unconfirmed) that the 20-warhead stockpile increase between 2018 and 2019 was caused by production of the Trump administration’s W76-2 low-yield Trident warhead. Image: NNSA.

The Trump administration’s brief increase of the stockpile is only the second time the United States has increased its number of nuclear warheads since the Cold War. The first time was in 1995-1996 when the Clinton administration increased the stockpile by 107 warheads. Since the W76-2 production continued after September 2019, the increase of 20 warheads should not be misinterpreted as being the final number of W76-2 warheads. After the 2018-2019 increase, the stockpile number dropped again by 55 warheads.

Update: Another possibility for the brief stockpile increase is that a small number of retired warheads were returned to the stockpile. This could potentially be B83-1 bombs that the Trump administration decided to retain instead of retiring with the fielding of the B61-12. It could potentially also be retired warheads brought in as feedstock for new weapon systems such as the planned nuclear sea-launched cruise missile. We just don’t know at this point.

Apparently, the nuclear modernization program supported by both Republicans and most Democrats, will result in significant additional reductions of the stockpile. In 2016, the former head of the Navy’s Strategic Systems Program, Vice Admiral Terry Benedict, said that once the W76-1 warhead production was completed by the end of FY2019, the W76-0 warheads that had not been converted to W76-1 would be retired and the total number of W76 warheads in the stockpile decrease by nearly 50%.

At the same time, the Pentagon’s Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs, Arthur T. Hopkins, told Congress that production and fielding of the B61-12 bomb would “result in a nearly 50 percent reduction in the number of nuclear gravity bombs in the stockpile” and “facilitate the removal from the stockpile of the last megaton-class weapon––the B83-1.”

Production of the W76-1 has now been completed but the promised reduction is not yet visible in the stockpile data – unless the excess warheads were gradually removed during the production years. The B61-12 has not been fielded yet so the gravity bomb reduction presumably will not happen until the mid-2020s.

Whatever the number of the additional stockpile reduction is, it is not planned to be nice to Kremlin and Beijing but because the US military doesn’t need the excess warheads anymore. Whether Russia and China’s nuclear increases will cause the Biden administration to change the plan outlined by Benedict and Hopkins will be decided by the Nuclear Posture Review.

Dismantlement Numbers

The data also shows that the United States as of September 2020 had about 2,000 retired warheads in storage awaiting dismantlement. Retired warheads are owned by the Department of Energy and not part of the DOD stockpile.

That number matches the available data. Former Secretary of State John Kerry said in 2015 that there were about 2,500 retired weapons left (as of September 2014). Since then, 1,432 warheads have been dismantled and an additional 967 weapons retired, which would leave just over 2,000 warheads in the dismantlement queue.

Approximately 2,000 retired warheads away dismantlement, including the B83 megaton gravity bomb. More are expected to follow during the next decade. Image: NNSA.

In our estimate from early this year, we thought the dismantlement queue had dropped to 1,750 warheads because we assumed the annual dismantlement rate had remained around 300. But as the data shows, both the Trump and Biden administrations reduced the number of warheads being dismantled per year.

In 2016, NNSA stated that it “will increase weapons dismantlement by 20 percent starting in FY 2018” and that the “accelerated rate will allow NNSA to complete the dismantlement commitment a year early, before the end of FY 2021.” NNSA reaffirmed in 2018, that all warheads retired prior to 2009 would be dismantled by end-FY 2022.

This pledge appears to have faded from recent documents after the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review was published. Instead, the annual number of warheads dismantled has decreased since FY 2018. Is it still the goal? Some of the warheads that should have been dismantled but are still with us reportedly include the W84 warheads from the ground-launched cruise missiles that were eliminated by the 1987 INF treaty and retired well before 2009.

Many of the warheads in the current dismantlement queue were retired after 2009. At the current rate of 184 warheads dismantled per year, it will take more than a decade to dismantle the current backlog. Once the excess W76s and old gravity bombs enter the queue, it will take even longer.

In Context

We commend the Biden administration for reversing the Trump administration’s shortsighted and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency to the US nuclear weapons stockpile. This decision is a heavy lifting at a time when so-called Great Power Competition is overtaking defense and arms control analysis. The Federation of American Scientists has for years advocated for increased transparency of nuclear arsenals and have worked to provide that through our estimates of nuclear weapons arsenals.

Although the recent reductions shown in stockpile and dismantlement data are modest, to put it mildly, we believe declassification is the right decision because making the record public will help US diplomats make the case that the United States is continuing its efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals and increase nuclear transparency. This is especially important in the context of the upcoming January 2022 Review Conference for the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. Dissatisfaction with the lackluster disarmament progress – and a belief that the nuclear-armed states are walking back decades of arms control progress with their excessive nuclear modernization programs and dangerous changes to operations and strategy – have fueled support for the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

The decision to disclose the stockpile and dismantlement data will also enhance the US credibility when urging other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals. We have no illusions that Russia or China will follow the example in the short term, but keeping the US numbers secret will certainly not help. And over time, the disclosure can help shape discussions and norms about nuclear transparency to shape future decisions. This is also important because the Trump secrecy recently provided cover for the United Kingdom to reduce information about its nuclear forces.

Hardliners will no doubt criticize the Biden administration’s decision to disclose the stockpile and dismantlement data. They will argue that past nuclear transparency has not given the United States any leverage, that nuclear-armed states previously have not followed the example, and it that makes the United States look naive – even irresponsible – in view of Russia and China’s nuclear secrecy and build-up.

On the contrary: without transparency the United States has no case. Past transparency has given the United States leverage to defend its record and promote its policies in international fora, dismiss rumors and exaggerations about its nuclear arsenal, and publicly and privately challenge other nuclear-armed states’ secrecy and promote nuclear transparency. And since the disclosure does not reveal any critical national security information, there is no reason to classify the stockpile and dismantlement data.

Hardliners obviously will have to acknowledge that the data shows that there has been no unilateral US disarmament but only a very modest reduction in recent years. And although there appear to be additional unilateral reductions built into the modernization programs, those are actually programs that have been supported and defended by the hardliners.

Now it is up to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review to articulate how and to what extent those plans support and strengthen US national security and nonproliferation objectives. Arms control obviously will have to be part of that assessment. The declassified stockpile and dismantlement data will help make the case that additional reductions are both needed and possible.

Background Information:

- US Department of State, Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, Fact Sheet, October 5, 2021

- “United States Nuclear Forces, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March/April 2021

- “Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, April 17, 2019

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists global arsenal page

This article was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Reevaluating U.S. Military Use of Drone Technology

In the 21st century, drone technology has become commonplace in warfare. In fact, drones are increasingly preferred by both state and non-state actors over other modes of warfare. But widespread use of drones in war engenders considerable controversy. Civilian casualties and collateral damage have grown alongside drone deployment with little accountability or transparency. As the Biden-Harris Administration works to rebuild America’s place on the world stage and as a member of the global community, the Administration should boost accountability for civilian deaths by rethinking when and how drones are used. Specifically, the Administration should (1) sign an executive order to boost transparency and oversight of drone technology used by the military, (2) work with Congress to review use of drones in U.S. military operations, and (3) lead efforts to launch an international drone accountability regime.

Challenge and Opportunity

In the last two decades, the use of drone strikes by the U.S. military against terrorist and militant organizations has expanded. Drones have been utilized so frequently by the U.S. government because they offer numerous advantages over manned aircraft. Drones are a cost-effective way to keep American boots off the ground and safe from danger. The fact that drones lack a human pilot means that fatigue is also lessened in military operations. Drone operators can hand off controls without any downtime, and drones can offer the same accuracy and lethality as manned aircraft. Drones can also serve as a valuable tool in surveillance operations.

But there is also a downside to this technology that makes warfare easy. Commanders are more likely to greenlight attacks when those attacks pose less of a direct risk to American military personnel. As the use of drones has proliferated, so too have the number of drone strikes ordered by the U.S. military — and the accompanying losses of civilian life.

Beginning in the early 2000s and into President Obama’s Administration, the use of drone technology increased. A 2005-2030 roadmap published by the Department of Defense noted that twenty types of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) were flown for 100,000 hours in conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Under President Obama, an estimated 3,797 people, including 324 civilians, were killed in the 542 strikes carried out during the eight years of his Administration. This was the result of a dramatic increase in drone warfare. In his second term, President Obama took steps to reign in the use of drone warfare but beginning in 2017, President Trump’s Administration took it to new heights. In his first two years in office, President Trump launched more drone strikes that President Obama did in eight years. Reporting suggests that with the use of drones, President Trump launched more attacks in Yemen than all previous U.S. presidents combined. These drone strikes together killed between 86 and 154 civilians.

President Obama signed Executive Order 13732 in 2016, which required the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) to review and investigate drone strikes involving civilian casualties and offer payment to families of those killed. The executive order also required the Director of National Intelligence to release annual summaries of all U.S. drone strikes conducted, accompanied by assessments of how many civilians died as a result of those strikes. But President Trump revoked this policy in 2019, arguing that the provisions were superfluous and distracting. As the use of drones increased dramatically in the first year of President Trump’s Administration, the United States also disclosed fewer details about the frequencies and fatalities of these strikes.

The time is ripe for the Biden-Harris Administration to reevaluate and rein in the use of drone warfare to both boost U.S. accountability for civilian deaths and restore America’s leadership on the world stage.

Plan of Action

The Biden-Harris Administration should take three essential actions to improve transparency and oversight of U.S. drone operations. These actions are crucial to restoring America’s place and reputation in the international community.

First, President Biden should sign an executive order committing to boost transparency and oversight of drone technology used by the U.S. government. On the first day of his Administration, President Biden imposed temporary limits on drone strikes outside of battlefields in Afghanistan, Syria, and Iraq and ordered a review of U.S. drone policy with respect to counterterrorism operations. This was a welcome step, and the Administration can build on it to promote greater transparency without compromising U.S. national security. An Executive Order to Reevaluate U.S. Military Use of Drone Technology to Boost Accountability for Civilian Deaths can and should reinstate much of Executive Order 13732, but also go further. Specifically, the executive order should:

- Commit to reduce the use of drone strikes overall.

- Commit to limit collateral damage when drone technology is used.

- Require the CIA to release biannual summaries of U.S. drone strikes, accompanied by assessments of civilian casualties.

- Offer payment to the families of civilians killed as a result of a U.S. drone strikes.

- Require the CIA, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Defense to conduct a thorough joint investigation of all drone use resulting in civilian deaths.

- Provide quarterly briefings to Congress on the use of drone technology and provide reports to relevant Congressional committees on investigations into drone strikes that result in civilian casualties.

To complement this executive order, the Biden-Harris Administration’s review of U.S. drone policy should include an interagency process involving the CIA, the National Security Council (NSC), and the Departments of Defense, State, and Justice to evaluate the increased use of drones over the past decade, analyze trends in technology shaping the future use of drones, and devise a coordinated path forward to (1) increase accountability for use of drone warfare, and (2) boost American national security through a strategic counterterrorism strategy that minimizes the extraneous use of drones.

Second, President Biden should work with Congress to review the use of drones in U.S. military operations, including use of drones both within and beyond active military conflict. The Administration should provide members of key Congressional committees (e.g., the Senate Foreign Relations, Armed Services, and Intelligence Committees as well as the House Foreign Affairs, Armed Services, and Intelligence Committees) with both classified and public briefings on the Administration’s counterterrorism strategy and the role of drone technology in advancing military operations. Congress, in turn, should conduct public hearings on these topics and should ultimately act to repeal and replace the outdated 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) which have been used by multiple presidents to justify continued military action across the globe, including drone strikes.

In fact, the Biden-Harris Administration has pushed for these AUMFs to be replaced with a “narrow and specific framework that will ensure we can protect Americans from terrorist threats while ending forever wars,” according to a statement by Press Secretary Jen Psaki in March 2021. The 2001 AUMF was passed after the Sept 11. Terrorist attacks and the 2002 AUMF was passed in the fall of 2002 ahead of the U.S.- led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Third, as one of the largest producers and sellers of drone technology worldwide, the United States should lead efforts to launch an international drone accountability regime. This effort, which could be launched through an existing international organization like the United Nations, would bring together states to:

- Sign a treaty that creates a commitment to abide by a set of international standards on the use of drone warfare, including a commitment to reduce collateral damage and loss of civilian life.

- Review and evaluate use of drone technology by nation, especially by global military leaders.

- Investigate and make public instances of drone-technology abuse.

The global accountability effort will require development of a strong set of international standards that regulate the use of drone technology — standards that will make the United States and the world safer. These international standards should include commitments by abiding states and non-state actors to: (1) commit to reducing the use of drone strikes and limiting collateral damage; (2) issue a public statement following drone strikes resulting in civilian casualties explaining the reason for the strike and relevant surrounding circumstances; and (3) publish summaries of all casualties and damage resulting from drone strikes. (4) Additionally, abiding parties that sell or purchase drone technology should commit to only sell or purchase drone technology from other abiding parties.

Conclusion

The growing ubiquity of drone strikes within U.S. military operations demands action to increase transparency and accountability. When drone strikes are used too freely, unnecessary civilian casualties can result — as recent history has already demonstrated. By strategically rethinking how the United States uses drones for warfare, the Biden-Harris Administration can rebuild accountability for civilian deaths, restore transparency to our nation’s use of drone technology, and repair our nation’s reputation on the world stage, all without compromising military operations or national security.

President Biden can take immediate action by issuing an executive order that builds on the drone-accountability policies put in place during the late Obama era while setting a new standard for the international community, as well as by ordering an interagency review of the role that drones play in U.S. operations. Further, President Biden should work with Congress to repeal and replace the outdated 2001 and 2002 AUMFs and to consider how drones can and should be used responsibly in warfare. These steps will be essential to restoring confidence in U.S. military operations both at home and abroad. Finally, as the U.S. seeks to rebuild its position in the global community, efforts led by the Biden-Harris Administration to establish an international drone-accountability regime can help check the growing use of drones in warfare globally: a result that will strengthen the security of the United States and the world.

The unmanned nature of drone warfare does indeed limit U.S. military casualties. But the widened use of drone warfare by the American military and resulting casualties poses risks to Americans. Civilian casualties and collateral damage that result from reckless drone strikes in many instances have provoked the targets of those strikes to retaliate against American troops.

First New START Data After Extension Shows Compliance

The first public release of New START aggregate numbers since the United States and Russia in February extended the agreement for five years shows the treaty continues to limit the two nuclear powers strategic offensive nuclear forces.

Continued adherence to the New START limits is one of the few positive signs in the otherwise frosty relations between the two countries.

The ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of March 1, 2021. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,567 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,168 launchers were deployed with 2,813 warheads. That is a slight decrease in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 3, decreased combined deployed strategic launchers by 17, and decreased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 91. Of these numbers, only the “3” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 combined have cut 422 strategic launchers from their arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 235, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 524. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (just over 6 percent) of the estimated 8,297 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (just over 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 11,807 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, exactly the maxim number allowed by the treaty, of which 651 are deployed with 1,357 warheads attributed to them. This is a decrease of 24 deployed strategic launchers and 100 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual decreases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The aggregate data does not reveal how many warheads are attributed to the three legs of the triad. The full unclassified data set will be released later. But if one assumes the number of deployed bombers and deployed ICBMs are the same as in the September 2020 data, then the SSBNs carry 909 warheads on 200 deployed Trident II SLBMs. That is a decrease of 100 warheads on the SSBN force compared with September, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for 67 percent of all the 1,357 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 70 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data indicates that the United States as of March 1, 2021 deployed approximately 909 warheads on ballistic missile onboard its strategic submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 231, and deployed strategic warheads by 443. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 12 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 8 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 767 strategic launchers, of which 517 are deployed with 1,456 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 7 deployed launchers and 9 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 98, deployed launchers by 4, and deployed strategic warheads by 81. This modest warhead reduction represents less than 2 percent of the estimated 4,497 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (only 1.3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,257 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, which may be happening in some categories, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 134 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap roughly equal to the number of missiles in an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs so far has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by nearly one-third since its lowest point in February 2018.

Although Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces, such as those of this SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) ICBM exercise near Bernaul, this has not yet resulted in an increase of its strategic nuclear weapons.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher disparity by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles (SS-27 Mod 2, Yars, and SS-N-32, Bulava) that are replacing older types (SS-25, Topol, and SS-N-18, Vysota). Thanks to the New START treaty limit, many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but are stored and could potentially be uploaded onto the launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (SS-19 Mod 4, Avangard, and SS-29, Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types (Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, and Burevestnik nuclear-powered ground-launched cruise missile) are not yet deployed and appear to be planned in relatively small numbers. They do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types, if the two sides agree.

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 21,727 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 860 of those notifications were exchanged since September 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Instead, notification exchanges and National Technical Means of verification have provided adequate verification. Nonetheless, on-site inspection can hopefully be resumed soon.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for U.S.-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

Looking Ahead

Although the New START treaty has been extended for five years and it appears to be working, that is no reason to be complacent. The United States and Russia should undertake detailed and ongoing negotiations about what a follow-on treaty will look like, so they are ready well before the five-year extension runs out. The incompetent and brinkmanship negotiation style of the Trump administration fully demonstrated the risks and perils of waiting to the last minute. The Biden administration can and should do better.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

British Defense Review Ends Nuclear Reductions Era

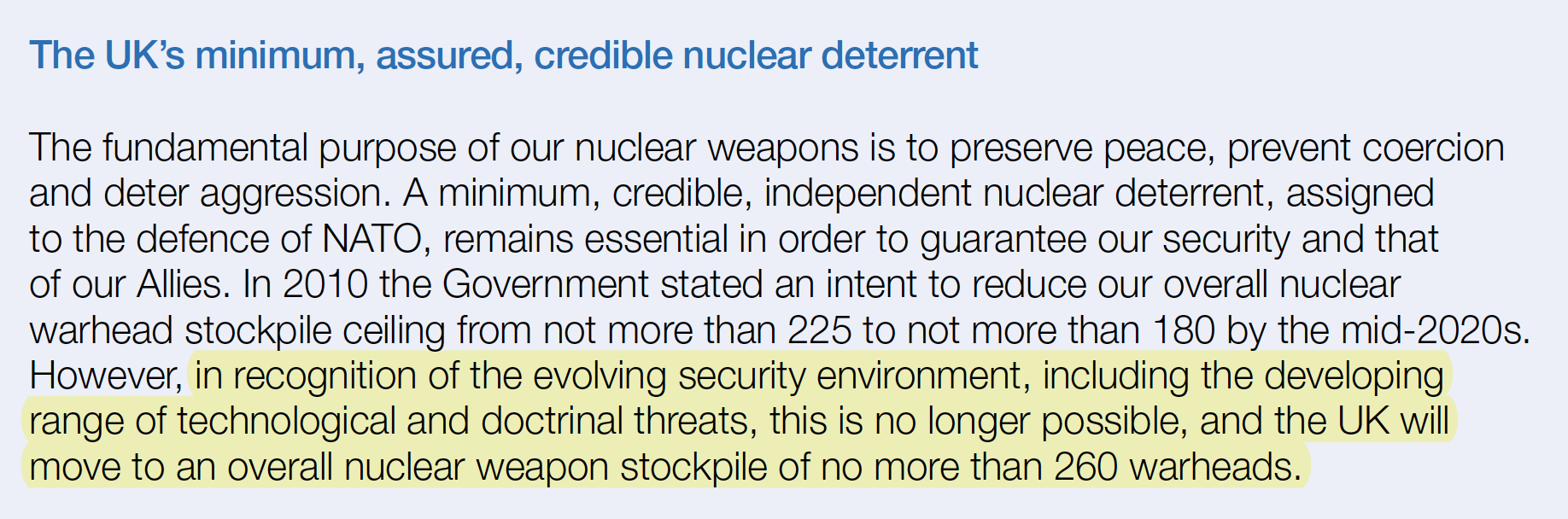

[Article updated May 11, 2021] The United Kingdom announced yesterday that it has decided to abandon a previous plan to reduce it nuclear weapons stockpile to 180 by the mid-2020s and instead “move to an overall nuclear weapon stockpile of no more than 260 warheads.”

The decision makes Britain the first Western nuclear-armed state to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile since the end of the end of the Cold War. In terms of numbers, it takes Britain back to a stockpile size it had in the early-2000s. The change is part of “a shift to a more robust position on security and deterrence.”

The Review also decided that Britain will “no longer give public figures for our operational stockpile, deployed warhead or deployed missile numbers.” This counterproductive decision follows the earlier decision of the Trump administration to keep the nuclear stockpile number secret. By embracing nuclear secrecy, Britain effectively abdicates its ability to criticize Chinese or Russian secrecy about their nuclear arsenals.

The decision to increase the size of the future stockpile – and potentially deploy more warheads on British submarines – is but the latest example of nuclear-armed states invigorating a nuclear arms race and reversing progress toward reducing the world’s nuclear arsenals.

The British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

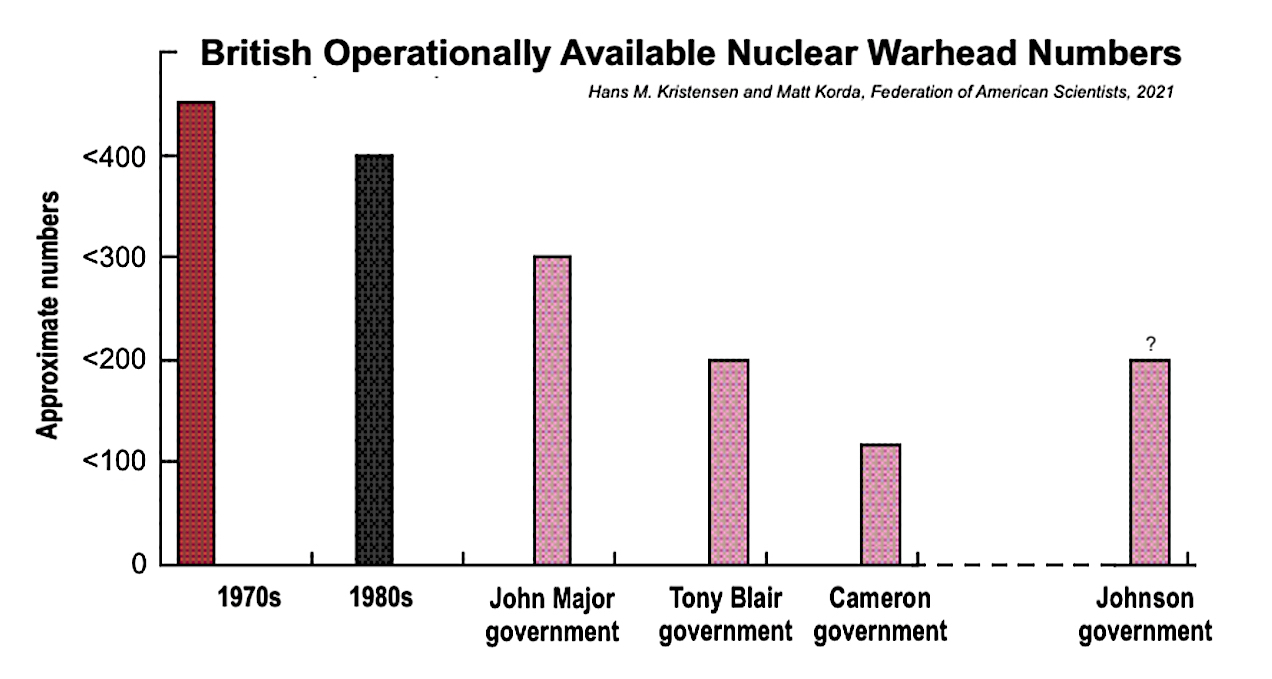

The British government has never declassified the history of its nuclear weapons stockpile. Instead, it has occasionally published documents or made statements that gave overall numbers or percentages. The government announced in 2010 that it would have “no more than 225” warheads and later that the limit would be reduced to 180 by the mid-2020s. It is unknown how far the reduction of those approximately 45 warheads has progressed. If spread out evenly over the 15 years, the number might have reached just below 200 by now. But it is highly uncertain so illustrating the British stockpile comes with considerable uncertainty (In this article we conclude that the stockpile did not drop below the 225 ceiling set in 2010 and remains at that level today). The following graph is illustrative and based on previous statements and documents.

Note: This graph has been updated. The history of the United Kingdom nuclear weapons stockpile is still classified, so the graph is provided for illustrative purposes. Click on graph to view full size.

The timeline for the new stockpile limit of 260 warheads is not entirely clear but appears to be during the 2020s. The Review reflects an assessment out to 2030 but “establishes the Government’s overarching national security and international policy objectives, with priority actions, to 2025.”

The wording of the new warhead level is vague. The Review sets the number at “no more than 260 warheads.” The British government has subsequently explained the “260 figure is a ceiling, not a target.” Political damage control is probably part of that statement, but the number could potentially be somewhat lower – or it could be about 260.

Not all of the stockpiled warheads are deployed. The majority is called “operationally available,” which means they’re onboard three of the four SSBNs or can be loaded fairly quickly. The rest are a reserve as spares or undergoing maintenance. Since 2015, the number of “operationally available warheads” has been approximately 120, of which the number deployed on the single SSBN at sea has been reduced to 40.

Unlikely previous defense reviews, the Integrated Review does not include any information about how many of the stockpiled warheads will be operationally available, loaded onboard deployed submarines, or how many submarines will be at sea at any given time. This is a step back for British nuclear transparency. Based on statements from previous governments, however, the number of operationally available warheads under the Johnson posture might end up being similar to what it was during the Blair government: perhaps close to 160 warheads.

The stockpiled warheads that are not “operationally available” are likely stored at Coulport Ammunition Depot nearly the Faslane Submarine Base in Scotland (see image below). Warheads undergoing maintenance or upgrade to the Mk4A aeroshell are probably stored at AWE Burghfield or AWE Aldermaston west of London. Retired warheads are shipped to Burghfield for dismantlement and disposition.

In 2013, the UK government described the process: warheads “yet to be disassembled” are stored at Coulport or as “work in progress” at Burghfield. “A number of warheads identified in the [stockpile reduction] programme for reduction have been modified to render them unusable whilst others identified as no longer being required for service are currently stored and have not yet been disabled or modified.”

Those retired warheads that have not been “rendered unusable” are most likely the source for increasing the stockpile now. Britain doesn’t have the capacity to quickly produce 50-60 new warheads so it simply brings warheads out of retirement. Reconstituting those warheads can probably be done in a few years.

Nuclear Strategy and Targeting

The extent to which the increased stockpile will affect targeting requirement for Britain’s ballistic missile submarines remains to be seen. But the Review states that the stockpile increase comes in response to “the evolving security environment, including the developing range of technological and doctrinal threats.”

Russia is singled out as “the most acute direct threat to the UK” but the Review also contains what appears to be a subtle but clear nuclear threat against Iran (even though it doesn’t have nuclear weapons). After assuring the “UK will not use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 1968 (NPT),” the Review adds: “This assurance does not apply to any state in material breach of those non-proliferation obligations.”

The difference between the stockpile limit number and operationally deployed warheads in previous government statements indicates that an increased stockpile limit of 260 warheads most likely will also result in an increase in the number of operationally available warheads and possibly the number of warheads onboard the submarines. An increased number of deployed warheads means an increased number of aimpoints. The United States shares strategic war plan details with the United Kingdom in support of NATO.