New Nuclear Weapons Employment Guidance Puts Obama’s Fingerprint on Nuclear Weapons Policy and Strategy

President Barack Obama’s Berlin speech failed to capture the nuclear disarmament spirit of the Prague speech four years ago. And no wonder. Back then Obama had to contrast with the Bush administration’s nuclear policies. This time Obama had to upstage his own record.

The only real nuclear weapons news that was included in the Berlin speech was a decision previously reported by the Center for Public Integrity that the administration is pursuing an “up to a one-third reduction” in deployed nuclear weapons established under New START.

Instead, the real nuclear news of the day were the results of the Obama administration’s long-awaited new guidance on nuclear weapons employment policy that was explained in a White House fact sheet and a more in-depth report to Congress.

From a nuclear arms control perspective, the new guidance is a mixed bag.

One the one hand, the guidance directs pursuit of additional reductions in deployed strategic warheads and less reliance on preparing for a surprise nuclear attack. On the other hand, the guidance reaffirms a commitment to core Cold War posture characteristics such as counterforce targeting, retaining a triad of strategic nuclear forces, and retaining non-strategic nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

Pursue Additional Reductions

The top news is that the administration has decided that it can meet its security obligations with “up to one-third” fewer deployed strategic warheads that it is allowed under the New START treaty. That would imply that the guidance review has concluded that the United States needs 1,000-1,100 warheads deployed on land- and sea-based strategic warheads, down from the 1,550 permitted under the New START treaty.

It is not entirely clear from the public language, but it appears to be so, that these additional reductions will be pursued in negotiations with Russia rather than as reciprocal unilateral reductions.

Even though the nuclear weapons employment policy would allow for reductions below the New START Treaty levels, it does not direct any changes to the currently deployed forces of the United States. That is up to the follow-on process of the Secretary of Defense producing an updated Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) appendix to the Guidance for the Employment of the Force (GEF), and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff then producing an update to the nuclear supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP-N).

These updates will inform the Commander of STRATCOM on how to direct the Joint Functional Component Command Global Strike (JFCC-GS) to update the strategic war plan (OPLAN 8010-12), and Geographic Combatant Commanders such as the Commander of European Command to update their regional plans.

So if an when Russia agrees to cutting its deployed strategic warheads by up to one third, it could take several years before President Obama’s guidance actually affects the nuclear employment plans.

Already now, many news articles covering the Berlin speech misrepresent the “cut” by saying it would reduce the U.S. “arsenal” or “stockpile” by one third. But that is not accurate. The envisioned one-third reduction of deployed strategic warheads will not in and of itself destroy a single nuclear warhead or reduce the size of the bloated U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals.

Reduce Launch Under Attack

The new guidance recognizes, which is important although late, that the possibility of a disarming surprise nuclear attack has diminished significantly since the Cold War. Therefore, the guidance “directs DoD to examine further options to reduce the role of Launch Under Attack plays in U.S. planning, while retaining the ability to Launch Under Attack if directed.”

Launch under attack is the capability to be able to launch nuclear forces after detection that an adversary has initiated a major nuclear attack. Because it only takes about 30 minutes for an ICBM to fly from Russia over the North Pole, Launch Under Attack (LOA) has meant keeping hundreds of weapons on alert and ready to launch within minutes after receiving the launch order.

Barack Obama promised during his election campaign in 2007 that he would work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger alert,” but the Nuclear Posture Review instead decided to continue the existing readiness of nuclear forces. Now the DOD is directed to study how to reduce LOA in nuclear strike planning but retain some LOA capability.

The guidance does not explicitly say – to the extent it is covered by the DOD report – that nuclear force will be retained on alert. The NPR makes such a statement clearly. The DOD guidance report only states that the practice of open-ocean targeting should be retained so that a weapon launched by mistake would land in the open ocean.

Despite the decision to reduce deployed strategic warheads and reduce Launch Under Attack, the guidance hedges against the change by stating that “the maintenance of a Triad and the ability to upload warheads ensures that, should any potential crisis emerge in the future, no adversary could conclude that any perceived benefits of attacking the United States or its Allies and partners are outweighed by the costs our response would impose on them.”

Counterforce Reaffirmed

The new guidance reaffirms the Cold War practice of using nuclear forces to hold nuclear forces at risk. According to the DOD summary, the new guidance “requires the United States to maintain significant counterforce capabilities against potential adversaries” and explicitly “does not rely on a ‘counter-value’ or ‘minimum deterrence’ strategy.”

This reaffirmation is perhaps the single most important indicator that the new guidance fails to “put and end to Cold War thinking” as envisioned by the Prague speech.

Because “counterforce is preemptive or offensively reactive,” in the words of a STRATCOM-led study from 2002, reaffirmation of nuclear counterforce reaffirms highly offensive planning that is unnecessarily threatening for deterrence to work in the 21st Century. This condition is exacerbated because the reaffirmation of counterforce is associated with a decision to retain – albeit at a reduced level – the ability to Launch Under Attack if directed (see below).

The “warfighting” nature of nuclear counterforce drives requirements for Cold War-like postures and technical and operational requirements that sustain nuclear competition between major nuclear powers at a level that undercuts efforts to reduce the role and numbers of nuclear weapons.

No Sole Purpose…But

Four years after the Nuclear Posture Review decided that the United States could not adopt a sole purpose of nuclear weapons to deter only nuclear attacks, the new guidance reaffirms this rejection by saying “we cannot adopt such a policy today.”

Even so, the guidance apparently reiterates the intention to work towards that goal over time. And it directs the DOD to undertake concrete steps to further reducing the role of nuclear weapons.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

The decisions regarding non-strategic nuclear weapons are disappointing because they fail to progress the issue. In fact, the White House fact sheet explicitly states that the guidance review did not address forward deployed non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe.

Even so, the guidance decides to retain a forward-based posture in Europe until NATO agrees it is time to change the posture. The last four years have shown that NATO is incapable of doing so because a few eastern NATO countries cling to Cold War perceptions about nuclear weapons in Europe that blocks progress.

In effect, the lack of initiative now means countries like Lithuania now effectively dictate U.S. policy on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Hedging Against Hedging

The guidance also directs that the United States will continue to retain a large reserve of non-deployed warheads to hedge against technical failures in deployed warheads.

This both means enough extra warhead types within each leg to hedge against another warhead on that leg failing, as well as keeping enough extra warheads for each leg to hedge against failure of one of the warheads on another leg.

Now that warhead life-extension programs are underway, the guidance directs that DOD should only retain hedge warheads for those modified warheads until confidence is attained. This is a little cryptic because why would the DOD not do that, but the intension seems to be to avoid keeping the old hedge warheads longer than necessary.

Moreover, the guidance also states that all of the hedging against technical issues will provide enough reserve warheads to allow upload of additional warheads – including those removed under the New START Treaty – in response to a geopolitical development somewhere in the world.

This all suggests that we should not expect to see significant reductions in the hedge in the near future but that much of the current hedging strategy will be in place for the next decade and a half.

Conclusions

The Obama administration deserves credit for seeking further reductions in nuclear forces and the role of Launch of Warning in nuclear weapons employment planning. A White House fact sheet and a DOD report provide important information about the new nuclear weapons employment guidance, a controversial issue on which previous administrations have largely failed to brief the public.

The DOD’s report on the new guidance reiterates that it is U.S. policy to “seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” but helpfully reminds that “it is imperative that we continue to take concrete steps toward it now.” This is helpful because Obama’s recognition in Prague that the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons might not be achieved in his lifetime has been twisted by opponents of reductions and disarmament to mean an affirmative “not in my lifetime!”

The guidance directs that nuclear “planning should focus on only those objectives and missions that are necessary for deterrence in the 21st century.” The force should be flexible enough, the guidance says, to be able to respond to “a wide range of options” by being able to “threaten credibly a wide range of nuclear responses if deterrence should fail.”

Unfortunately, the public documents do not shed any light on what those objectives and missions are or which ones have been deemed no longer necessary.

Instead, the official descriptions of the new guidance show that its retains much of the Cold War thinking that President Obama said in Prague four years ago that he wanted to put an end to. The reaffirmation of nuclear counterforce and retention of nuclear weapons in Europe are particularly disappointing, as is the decision to retain a large reserve of non-deployed warheads partly to be able to reverse reductions of deployed strategic warheads achieved under the New START Treaty.

In the coming months and years, these decisions will likely be used to justify expensive modernizations of nuclear forces and upgrades to nuclear warheads that will prompt many to ask what has actually changed.

Background: US Nuclear Forces, 2013 – Russian Nuclear Forces, 2013 – Reviewing Nuclear Guidance – From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

SIPRI Yearbook 2013 Published

The Swedish International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) today published the 2013 issue of the SIPRI Yearbook. I’m coauthor of the chapter on worldwide nuclear weapons arsenals.

The yearbook is translated into Arabic, Chinese, Russian and Ukrainian, providing a unique source of nuclear weapons information to regions where such information is either not available or only to English-speaking readers.

In addition to the annual SIPRI Yearbook, bimonthly updates of individual nuclear weapon states are published as Nuclear Notebooks in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Moreover, an online table of world nuclear forces is provided on the FAS web site. The table is updated as new information becomes available.

Finally, occasional issue reports are published on the FAS Strategic Security Blog.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

President’s Message: Complexity Overload and Extreme Events

To paraphrase Leon Trotsky’s saying about war but applied to extreme events, “You may not be interested in extreme events, but extreme events are interested in you.” The “you” here refers to the general public. I trust that readers of the Public Interest Report have self-selected themselves to be concerned about extreme events such as nuclear war, pandemics, and massive tsunamis triggering nuclear disasters. But the public has largely averted its gaze and would prefer not to contemplate “unthinkable” extreme events. Our task here at FAS is to convey to the public a better understanding of these events and provide better means to reduce and respond to them.

As I wrote in the previous president’s message, FAS is refocusing its mission on understanding, reducing, and responding to catastrophic risks. To further this mission, I have been looking for guidance as to how FAS can discover the intellectual talent and form the networks of specialists to help the world in dealing with catastrophic threats or extreme events. I recently found important insights in Dr. John Casti’s book X-Events: Complexity Overload and the Collapse of Everything, published in 2012. Dr. Casti, a mathematician and a former researcher at RAND and the Santa Fe Institute among other places, has been one of the foremost experts on complexity science. In his latest book, he argues that an extreme event or “X-event” is “human nature’s way of bridging a chasm between two (or more) systems.”

He gives the example of the gap between an authoritarian government (think Egypt under Hosni Mubarak) and the populace. The government has clamped down on people’s freedoms for decades using draconian methods and has been exceedingly corrupt and dysfunctional. Wanting outlets for political expression, citizens have been using social media tools such as Facebook and Twitter for political organizing. Dr. Casti points out that this development represents a growing, positive increase in the political capabilities of the citizenry—what he would term formation of a “high complexity” environment—versus an ossified, low-complexity government that is initially inclined to crush the protests instead of expanding freedoms. Dr. Casti argues that instead what the government should have done was to increase its complexity such that it could respond constructively to the protests. But it takes significant effort to bridge the complexity gap.

Seeking an easy way out of the perceived impasse, the Egyptian government’s initial response to the protests was to shut down the Internet in Egypt by ordering the country’s five main service providers to cut service on January 28, 2011, and the government also arrested several bloggers. U.S. President Barack Obama soon called on the Egyptian government to restore the Internet and give its citizens freedom of expression, and international service providers worked to find ways around the government’s cut in service. The Internet was restored on February 2, 2011, and the bloggers were released from prison. Mubarak was not so long afterwards deposed. As we have seen in the past two years, Egypt is still experiencing growing pains in its political transition, and it is not clear whether it will soon form a government responsive to its people’s needs. However, the movement illustrated the power of social networking tools in expanding people’s opportunities to organize and increase political complexity.

As Dr. Casti discusses in his book, there is a law of requisite complexity such that “the complexity of the controller has to be at least as great as the complexity of the system that’s being controlled.” For example, in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, the complexity of the control system (in particular, the height of the seawall and the location of the emergency diesel generators) was literally and figuratively too low to counter the higher complexity of the massive earthquake and tsunami.

I would also point out that the Japanese regulatory authorities and industry officials told the public for many years before the Fukushima accident that major nuclear accidents would not occur; this is the so-called nuclear safety myth. In effect, these authorities tried to sell the public on nuclear power being relatively low complexity. Today, Japan is faced with public mistrust and lack of confidence in nuclear power. The government has created a new regulatory agency called the Nuclear Regulation Authority. There are concerns that it is adopting too much of a deterministic approach to nuclear safety. That is, it is trying to achieve the strictest safety standards in the world by requiring many redundant safety systems at each nuclear plant to prevent further accidents. Instead, many experts outside of Japan are recommending a risk-informed approach that that uses multiple layers of safety systems but acknowledges that there will be some small level of risk. The question remains: can the Japanese public accept having some risk of a nuclear accident? Perhaps they can if the government and industry can demonstrate that it can handle high complexity events such as the possibility of accidents so as to protect the public from harm. For example, if the accident’s effects such as radioactivity release can be contained on the nuclear plant site, the public can be protected from radioactive contamination.

Can complexity mismatches be identified ahead of a catastrophe and steps taken to bridge the gap before catastrophe strikes? This is the message of the latter part of Dr. Casti’s book. He advises, for example, to look for major fluctuations and repeated occurrences in critical parameters of a system in order to forecast an impending catastrophe. For instance, in nuclear safety systems, one can look for repeated failures to inspect safety equipment, numerous unplanned shutdowns of plants due to exceeding thresholds in safety systems, and calls from whistleblowers about safety concerns. These are some major signs that urgent attention is needed.

How can governments and the public respond to avert such catastrophes? For example, a government needs to demonstrate its responsiveness to a crisis before it explodes into a catastrophe. Syria shows how lack of a government response to an environmental crisis triggered widespread public discontent and the recent civil war. As Tom Friedman wrote in the May 19 edition of the New York Times, the Syrian government did essentially nothing to help farmers deal with the massive drought that occurred a few years ago. Instead, President Bashar al-Assad’s policy of allowing big conglomerate farms to drain the very limited aquifers made Syria’s smaller farms acutely vulnerable to the drought. Out of work farmers flocked to Syria’s cities and began political organizing. The high unemployment further exacerbated people’s discontent with Assad’s government and helped spur the civil war. In hindsight, if Assad’s advisers could have foreseen this turn of events, they could have advised him to tend to the legitimate concerns of the farmers and other people out of work.

In another Arab country further south of Syria, water and political crises have been unfolding. But unlike Syria, Yemen might find a way out of its political crisis stopping short of civil war. Yemen confronts a major water disaster in that its capital Sana’a, according to some estimates, may run out of sufficient potable water in a decade, and numerous aquifers across the country are being drained faster than they can be refilled. But the good news is that after President Ali Abdullah Saleh stepped down in 2012, the political factions in the country have begun a national dialogue. This process has encouragingly included many women leaders. Several women had led the protests demanding that then-President Saleh relinquish power. While there will undoubtedly be hurdles along this dialogue process, it is a sign of increasing positive political complexity. This is greatly needed for Yemen to have any hope of solving its water crisis in addition to the crises of shortages of energy and burgeoning population with high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

I invite you to contact FAS headquarters with your suggestions about how we can work together to use the insights of complexity science to better understand our complex world and work to reduce and respond to catastrophic risks.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists

Digital Manufacturing and Missile Proliferation

Digital manufacturing is likely to be one of the key disruptive technologies of the 21st century. Described by The Economist as the foundation of a third industrial revolution, 1 digital manufacturing enables individuals and communities of designers to manufacture products themselves rather than relying on large factories with global supply chains.

While digital manufacturing holds significant potential as an engine of economic change, its potential effects on the proliferation of missiles and other weapons has not been adequately explored. The production and proliferation of missiles is foundationally an industrial process. Developing missile capability currently requires specialized industrial capabilities and expertise. Proliferation involves worldwide supply and transport chains similar to that of any modern globalized industry, albeit operating in secret. Just as digital manufacturing is likely to change the way household goods are produced, it will affect how missiles and other weapons are developed and proliferated.

What is Digital Manufacturing?

Digital manufacturing combines desktop design software – the sort that can be run from your home computer- and both traditional and new manufacturing equipment including 3D printers, Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines that use digital instructions to operate a variety of cutting and millings tools, and laser cutters.

Digital manufacturing begins with software. Using software that has been used by industrial designers for decades, one can design and render a 3D model of the object for production. Designers need not start from scratch. The open source movement- a worldwide movement of inventors, programmers and designers who make their work available to others free of charge- provides a wide range of designs that can be directly manufactured or built on to create custom designs for particular needs. Designers can also take advantage of 3D scanners which can make a digital model of a physical object, saving the designer the trouble of redesigning the object from scratch and allowing the production of exceedingly exact copies.2

The designer can then upload their work to digital manufacturing machines that can craft a range of products. 3D printers have received the lion’s share of attention in popular press due to the novel way they function. Rather than subtracting mass from a piece of raw material by cutting or molding, it adds material together to create a product. Printers equipped with print heads similar to the one of desktop inkjet printers spray layers of plastic to create products. More advanced machines use lasers to harden powder or liquid in layers to create objects, and can fashion products out of a wide range of metals including steel and titanium. CNC machines can be equipped with various tools that allow them to cut or mill a block of material into a desired shape or product. Laser cutters slice sheets of metal or wood into 2-dimensional objects and components.3

Digital manufacturing inverts traditional industrial mass production. Mass production creates very large numbers of identical objects. Digital manufacturing tools are more flexible- each machine can be used to produce a wide range of objects without requiring the often expensive and lengthy retooling traditional mass production would require. As digitally manufactured objects are produced individually there are no additional costs for additional complexity or customization in an object, allowing products to be designed to fit extremely specific requirements. This individualized production, however, means that digital manufacturing doesn’t capture the economies of scale seen in traditional mass production- the 100th or 1000th digitally manufactured object will cost as much as the first, whereas mass production requires a significant upfront investment that pays for itself over the manufacture of many hundreds or thousands of copies of a product.4

Another advantage of digital manufacturing is that it enables local production. A file can be sent to a digital manufacturing machine anywhere in the world and produce an object on demand. Rather than outsourcing the manufacture of a product to a factory in China or elsewhere in the world (a process that can take weeks or months and introduces significant supply chain risks), a designer or customer can immediately make a product to meet a local need. The localization of manufacturing is potentially one of the most important effects of digital manufacturing as it could shift manufacturing (and manufacturing jobs) away from China and other low-cost global powerhouses back to the West and to local markets. The local advantage of digital manufacturing, beyond potentially changing the nature of the global economy, also encourages the spread of digital manufacturing capabilities. As 3D printers and other machines become available in local economies throughout the world, they will also become increasingly available to state and non-state actors who could harness them to produce missiles and other weapons.

The automotive and aerospace industries have been early adopters of digital manufacturing technologies. Ford uses 3D printers for rapid prototyping of automobile parts. 5 In 2012, GE Aviation purchased Morris Technologies, a company heavily invested in 3D printing and other digital manufacturing technologies, which produces components for commercial jet engines. 3D printing reduces the amount and weight of the material in these engine parts, resulting in a more efficient jet engine.6 On a grander scale, Airbus is reported to be developing a 3D printer large enough to manufacture entire aircraft wings.7

Digital manufacturing has also been embraced by the U.S military. The U.S. Army Research, Development and Engineering Command uses computer design software, 3D scanners, and 3D printers for the development and rapid prototyping of equipment before it is mass produced using conventional manufacturing techniques.8 Starting in 2012, mobile laboratories equipped with digital manufacturing capabilities have been forward deployed to support the logistics needs of troops in Afghanistan.9 The mobile labs allow the U.S. Army’s Rapid Equipping Force to manufacture spare parts and new components in Afghanistan based on collaborations from designers and engineers both in the United States and deployed in Afghanistan.

Printing Missiles

The proliferation of missiles and other complex systems is, at heart, an industrial process. Digital manufacturing will disrupt that process and allow for the production of more effective missile components, using a wider variety of facilities and equipment, by a larger number of actors. Digital manufacturing tools themselves would not be capable of producing a complete missile but they could be used to fabricate many key missile components, thereby reducing the challenge faced by a new weapons state from the manufacture of a weapon from scratch to the simpler assembly of a missile from its digitally produced parts.

Digital manufacturing can be used to produce components for missiles that are more effective than those produced by traditional industrial processes. NASA is currently using selective laser melting, a process similar to 3D printing which uses a laser to harden layers of metallic powder into an object, to produce components for the Space Launch System(SLS). The SLS is a heavy lift rocket intended to carry robotic and manned missions to “nearby asteroids and eventually to Mars.”10 As digital manufacturing allows rocket components to be produced in a single piece, rather than welding together smaller parts produced using traditional processes, the components are stronger and more resilient increasing the reliability of the launch vehicle. Digital manufacturing would likely produce similar benefits for the production of components for ballistic missiles, which share many common features with space launch vehicles.

Missile warheads and fuel may also be made more effective by digital manufacturing. 3D printing could be used to produce warheads with specific geometries that would produce enhanced effects when detonated.11 Similar methods could also be used to produce propellants shaped to provide better and more efficient burn rates for rockets and ammunition. 12

A greater proportion of digital manufacturing equipment than its traditional industrial counterparts will be dual-use technology. Digital manufacturing tools are inherently flexible and can produce a wide range of products without requiring retooling or other substantial modification. Governments and non-state actors could take advantage of civilian digital manufacturing capabilities to produce components for missiles and other weapons systems without needing to modify the equipment or the facilities that house it. The number of facilities that could be used for proliferation activities would be significantly greater making detecting and tracking a missile program more difficult. This would also complicate efforts to disable or delay a missile program through sabotage or an overt military attack. Lastly, the greater number of proliferation-sensitive facilities would make transparency and confidence building more difficult even in the absence of intent to acquire missiles or other weapons.

Digital manufacturing would also allow proliferators to better leverage limited human capital. Design software requires less expertise to use than traditional design methods. Digital manufacturing systems themselves are automated, reducing the number of skilled machinists and technicians needed to produce missile components. 13 While the assembly and integration of components into a functioning missile system would still require a pool of experienced engineers and technicians, proliferators would still require less design and production expertise than traditional industrial production processes would demand.

Digital manufacturing would also benefit non-state proliferators. Non-state actors generally lack access to facilities to produce anything beyond crude artillery rockets and depend on support from state sponsors. As digital manufacturing capabilities become increasingly available throughout the world, non-state actors will be able to access local manufacturing capabilities to produce weapons based on designs provided by their state benefactors or to improve home built capabilities. Hamas, for instance, has made extensive use of crude artillery rockets, the accuracy and effectiveness of which would be significantly improved if engine parts and other components currently made with drills and lathes were produced with greater precision by digital manufacturing machines.

Online Proliferation

A key advantage of digital manufacturing is the ability to easily convert a design from a file directly into a physical object. As cyber-crime, efforts to crack down on software and music piracy and Wikileaks have demonstrated, information is very difficult to protect, contain, and control. Rather than attempting to prevent the shipment of missiles or components from states like North Korea or Iran to new weapons states or non-state actors, the non-proliferation regime will be faced with the problem of controlling the movement of information. It would most likely be easier for North Korea, for instance, to transfer data to allow a customer to manufacture missile components using local digital manufacturing facilities than to ship missiles or components that could be tracked and intercepted as they traveled from Northeast Asia to the Middle East or other hotspots. A proliferating state could leverage digital manufacturing to shift its business model to the sale of weapon design information rather than complete weapons or to reduce the scale of shipments to make them more difficult to track.

Digital manufacturing is also deeply linked with the open source hardware movement which has developed tools to allow for the easy sharing of hardware designs as well as collaboration on new projects. This approach has been adopted for military projects in the United States; the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) currently sponsors a project to design a new amphibious tank for the U.S. Marine Corp that uses online collaboration tools to allow far flung networks of researchers to collaborate on designs.14 Similar tools would facilitate collaboration among global proliferation networks such as the Iranian-North Korean partnership for the development of ballistic missiles.15 Non-state actors could also use such tools to leverage the efforts of sympathetic engineers and designers throughout the world. Proliferators could also take advantage of the blueprints made available by members of the open-source movement elsewhere in the world. Designers with an interest in space systems or aerodynamics could unwittingly provide assistance to a foreign missile design program.16

Proliferators could also benefit from design information from Western governments and industry. The computer networks of the U.S. government and defense contractors are frequent targets of cyber-attacks from a variety of sources. While technical specifications and other design information obtained via cyber-espionage would already be useful to proliferators, digital manufacturing would exacerbate this vulnerability. Designs intended for digital manufacture – either for rapid prototyping or for the production of final components – would be easier for proliferators to use. Rather than needing to interpret and replicate the production of a component or system from stolen design files, proliferators could simply enter the data into compatible digital manufacturing machines to produce an exact physical copy of the stolen design.

Beyond Missiles

Digital manufacturing has security implications beyond missile proliferation. The information sharing and streamlined production processes that make the proliferation of missiles easier could also enable nuclear proliferation. Digital manufacturing would have little effect on the production of nuclear weapons themselves or their requirement for significant quantities of highly enriched uranium or weapons grade plutonium. The design and production of uranium enrichment centrifuges and other equipment necessary for a nuclear program, however, would be simplified by digital manufacturing much as missile production would be.

Digital manufacturing could also be used to produce small arms. Open source networks are collaborating on the design of small arms including Defense Distributed, a U.S. based group that is working to design and produce 3D printable firearms including the controversial AR-15 rifle.17 As digital manufacturing becomes more widespread such projects will serve to significantly undermine domestic gun control laws as well as undercut international efforts to control the trade in small arms.

The manufacture of spare parts, as currently undertaken by the U.S. military, could also serve to undermine sanctions regimes intended to curtail proliferation. Iran, for instance, has a significant number of aircraft and weapons systems obtained from the West before the Islamic Revolution. While Iran’s F-14 fighter aircraft are less capable than the most advanced aircraft flown by the United States and its regional allies, they could still pose a potent threat. The difficulty in obtaining spare parts and other maintenance supplies from the U.S. has grounded most of the Iranian Air Force’s F-14s and forced Iran to develop clandestine networks to secretly obtain spare parts under the cover of legitimate business deals.18 In the future, a state placed under an arms embargo could use digital files- obtained legally before the sanctions or clandestinely afterwards- or 3D scans of existing components to produce new parts and maintain their military capabilities despite sanctions.

Proliferation in the Digital Future

Digital manufacturing will change the production and proliferation of missiles and other weapons in much the same way it will transform civilian industries. Rather than depending on a small number of states with the capability and will to proliferate missile systems or technologies, state and non-state actors will be able to leverage the civilian manufacturing sector and global networks of missile expertise to obtain weapons.

This new industrial model for proliferation will require new concepts for counter-proliferation. Missile and other weapons technologies will be available to a wider number of actors. Future counter-proliferation efforts will be faced with less visible footprints for missile production and ethereal web-based networks of missile expertise and data proliferation. Non-proliferation and cyber security experts will need to collaborate to understand how to track and defeat the information sharing capabilities that digital manufacturing enables. Stopping the flow of missile technology around the world has been a difficult task faced with many setbacks. As digital manufacturing comes of age, preventing further missile proliferation will only become more difficult.

Matthew Hallex is a defense analyst who lives and works in northern Virginia. He holds a Masters in Security Policy Studies from George Washington University.

PREPCOM Nuclear Weapons De-Alerting Briefing

By Hans M. Kristensen

Greetings from Geneva! I’m at the Palais des Nations for the second Preparatory Committee (PREPCOM) meeting for the 2015 Review Conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). I was invited by the Swiss and New Zealand UN Missions to brief our report Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons.

With me on the panel was Richard Garwin, an FAS board member who for more than five decades has advised U.S. governments on nuclear weapons and other issues, and Gareth Evans, former Australian Foreign Minister and now Chancellor of the Australian National University.

The panel was co-chaired by Ambassador H.E. Dell Higgie, the head of the New Zealand UN Mission and Permanent Representative to the United Nations and Conference on Disarmament, and Ambassador Benno Laggner, the head of the Swiss Foreign Ministry’s Division for Security Policy and Ambassador for Nuclear Disarmament and Non-Proliferation. Switzerland and New Zealand have for several years spearheaded efforts in the United Nations to reduce the alert level of nuclear weapons.

I wrote the de-alerting report together with Matthew McKinzie who directs the nuclear program at the Natural Resources Defense Council. Click to download my briefing slides (7.6 MB) and prepared remarks.

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 2

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea’s recent success with its nuclear test and satellite launch evidence that it is maturing? Is there trepidation in Japan over the perceived threat of North Korea attacking Japan with a nuclear weapon? Has North Korea mastered re-entry vehicle (RV) technology? Is there any plausible way to de-nuclearize North Korea?

This is the second part of the Q&A, featuring Dr. Yousaf Butt, Dr. Jacques Hymans and Ms. Masako Toki. Read the first part here. (more…)

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 1

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea serious about their threats and are we on the brink of war? What influence does China exert over DPRK, and what influence is China wiling to exert over the DPRK? How does the increase in tension affect South Korean President Park Guen-he’s political agenda?

This is the first part of the Q&A featuring Dr. Ted Galen Carpenter, Dr. Balbina Hwang, Ms. Duyeon Kim and Dr. Leon Sigal. Read part two here.

New START Data: US Reductions Finally Picking Up; Russia Flatlining

By Hans M. Kristensen

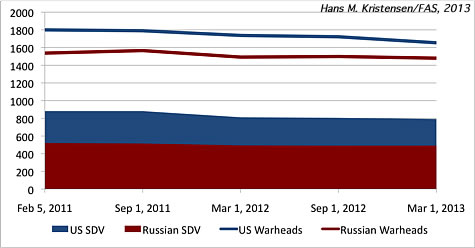

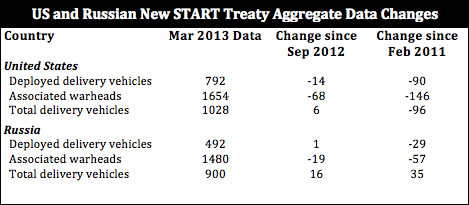

After two years of stalling, the latest New START Treaty aggregate data released today by the State Department indicates that U.S. warhead reductions under the treaty are finally picking up.

Russia, which is already below the treaty limit, has been more or less flatlining over the past year.

Seen in perspective, however, the warhead reductions achieved under New START so far are not impressive: since the treaty entered into effect in February 2011, the world’s two largest nuclear weapons states – with combined stockpiles of nearly 10,000 warheads – have only reduced their deployed arsenals by a total of 203 warheads!

The data for the United States shows a reduction of 68 warheads compared with September 2012. Fourteen of those are probably “fake” warheads attributed to B-52G bombers that are counted as deployed under the treaty, although they are neither deployed nor nuclear tasked anymore. The remaining 54-warhead reduction probably reflects downloading of the remaining MIRVed ICBMs (and some fluctuations in SLBM loadings of SSBNs in refit). Another 104 warheads will have to be reduced over the next five years to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed accountable warheads by 2018 (although many of those will come from reducing bombers that are not actually assigned nuclear weapons).

Russia, which has been below the ceiling of 1,550 deployed accountable strategic warheads for the past year, appears to be flatlining. It is counted with a 19-warhead reduction compared with September 2012. But that number is too low say whether it reflects real reductions due to retirement of missiles or just fluctuations in SLBM loadings on SSBNs in refit. Russia increased its delivery vehicles slightly due to deployment of the first new Borei-class SSBN.

What’s most striking about the data, though, is the significant asymmetry in delivery vehicles: the United States has 300 deployed delivery vehicles more than Russia, a disparity that causes Russia to deploy more warheads on each delivery vehicle and fuels worst-case military planning and paranoia about treaty break-out plans.

A clear objective for the next arms control agreement between the United States and Russia will have to be to reduce the U.S. delivery vehicles and Russian warhead loading to improve stability of the postures.

Moreover, with only 203 deployed warheads cut since the New START Treaty entered into effect more than two years ago, and nearly 10,000 nuclear warheads remaining in their stockpiles combined, there is clearly a need for the United States and Russia to speed up implementation of the treaty and agree to significant additional reductions.

[Details about the reductions are murky because the aggregate data only includes overall numbers, and does not specify how many of each delivery system are counted. A more detailed analysis will follow when the full detailed U.S. data becomes available in a few weeks.]

Background: See previous New START Treaty data analysis

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Invitation to Debate on Nuclear Weapons Reductions

Nuclear Debate at the Big 1800 Tonight

.By Hans M. Kristensen

Tonight I’ll be debating additional nuclear weapons reductions with former Assistant Secretary of State Stephen Rademaker at a PONI event at CSIS.

I will argue (prepared remarks here) that the United States could make more unilateral nuclear arms reductions in the future, as it has safely done in the past, as I argued in Trimming Nuclear Excess, in addition to pursuing arms control agreements. Mr. Rademaker will argue against unilateral reductions in favor of reciprocal or negotiated ones.

I suspect there will be a fair amount of overlap in the arguments but it is certainly a timely debate with the Obama administration pursuing additional reductions with Russia, the still-to-be-announced Nuclear Posture Review Implementation Study having determined that the United States can meet its national security and extended deterrence obligations with 500 fewer deployed strategic warheads, and budget cuts forcing new thinking about how many nuclear weapons and of what kind are needed.

The doors open at CSIS on 1800 K Street at 6 PM for a reception followed by the debate starting at 6:30 PM.

Document: Prepared remarks

(Still) Secret US Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Reduced

The United States has unilaterally reduced the size of its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009.

By Hans M. Kristensen

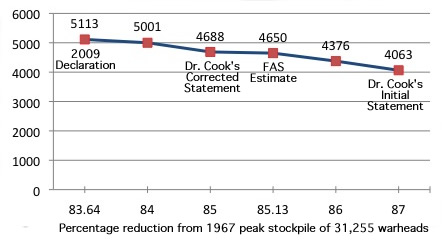

The United States has quietly reduced its nuclear weapons stockpile by nearly 500 warheads since 2009. The current stockpile size represents an approximate 85-percent reduction compared with the peak size in 1967, according to information provided to FAS by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The reduction is unilateral and not required by any arms control treaty. It apparently includes retirement of warheads for the last non-strategic naval nuclear weapon, the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N).

85 Versus 87

One of the interesting moments at the Deterrence Summit last week came when Dr. Donald Cook, who is NNSA’s administrator for defense programs, talked about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

At one point, Dr. Cook said that there are “roughly 5,000” warheads in the stockpile today. And then he added: “Today it’s, I’ll just say it’s a bit under about 5,000…about an 87 percent reduction” compared with the peak in 1967. (The 87 percent statements occurs 2:52:25 into the CSPAN recording).

Since the peak size of the stockpile has been declassified (31,255 warheads in 1967), an 87 percent reduction would in fact be quite a bit under 5,000 – a stockpile of 4,063 warheads, to be precise. If so, the stockpile would have shrunk by 1,050 warheads since September 2009 when the stockpile contained 5,113 warheads.

The number didn’t fit the stockpile estimate that Norris and I currently have (4,650 warheads), so I contacted Dr. Cook to double check if he meant to say 87 percent. He told me that it was an error and that the correct figure was “approximately 85% reduction.” That corresponds to a stockpile of roughly 4,688 warheads (depending on how many digits “approximately” implies), or about 38 warheads off our estimate of 4,650 warheads.

The warheads retired since 2009 apparently include the W80-0 warhead previously used on the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N). The 2010 Nuclear Posture Review decided the weapon was no longer needed, and “a very substantial number of W80-0″ warheads already have been dismantled, Dr. Cook told Congress last week. [Update 21 Mar: FY12 Pantex Performance Evaluation Report states (p.24): “All W80-0 warheads in the stockpile have been dismantled.” (Thanks Jay!)].

|

| The last remaining U.S. non-strategic naval nuclear weapon – the Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM/N – appears to have been retired in accordance with the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review determination that the weapon is no longer needed. |

.

Implications

Why is the size of the stockpile an issue? Well, first, because the Obama administration in 2010 declassified the 64-year history of the stockpile from 1945 through September 2009 because, as the Pentagon explained at the time, increasing transparency is important for U.S. nonproliferation efforts and additional arms reductions beyond the New START treaty. In his briefing, Dr. Cook also pointed to the importance of transparency.

Second, the size of the stockpile is important because although the administration has declassified 64 years of its history, its current size is – yes, you guessed it – still a secret. In fact, officials have told us that the 2010 disclosure was a one-time decision, not something that would be updated each year. So all stockpile numbers after September 2009 are still secret. Deep in the dark corridors of the Pentagon there are still people who believe this is necessary for national security.

Third, the unilateral retirement of roughly 500 warheads from the stockpile since 2009 – an inventory comparable to the total stockpiles of China and Britain combined – is political dynamite (no pun intended) because conservative Cold Warriors in Congress (and elsewhere) vehemently oppose unilateral reductions of U.S. nuclear weapons. Their argument is (as best I can gauge) that Russia and China are modernizing their nuclear weapons, and North Korea has just conducted a nuclear test. Therefore, so the thinking goes, it would somehow be detrimental to U.S. national security to unilaterally reduce its nuclear weapons.

The argument is, of course, deeply flawed because the reductions that Dr. Cook describe are warheads that the military has decided it no longer needs to meet presidential guidance for maintaining a strong nuclear deterrent in support of national security and reassurance of allies. Similar unilateral adjustments of the stockpile have been made by both Republican and Democratic administrations in the past.

The saga about stockpile classification and declassification is also important because it exemplifies a deeply schizophrenic policy. On the one hand, the administration has declassified decades worth of formerly secret stockpile information, emphasizes the continued importance of nuclear weapons transparency to support nonproliferation and arms control efforts, and urges other nuclear weapons states to be more open about their arsenals. At the same time, the administration continues to keep secret the current size of the stockpile, which, among other effects, forces officials such as Dr. Cook to be unnecessarily vague about the extent to which the United States continues to make progress on reducing nuclear weapons in compliance with its obligations under the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Recommendations

If the administration believes that nuclear transparency is important, then it must continue to disclose stockpile numbers and avoid drifting back into automatic nuclear secrecy. It should also declassify how many weapons are dismantled each year and how many retired warheads are in storage awaiting dismantlement.

The Pentagon said in 2010 that it was looking at declassifying the number of weapons awaiting dismantlement, but so far nothing has happened.

The Nuclear Posture Review stated in 2010: “Today, there are several thousand nuclear warheads awaiting dismantlement, and this number will increase as weapons are removed from the stockpile under New START.” Actually, the New START Treaty does not require that nuclear warheads be removed from the stockpile, but the military will nonetheless probably retire the roughly 500 warheads assigned to the 48 SLBMs and 50 ICBMs that will be retired under the treaty.

We estimate that “several thousand” currently means about 3,000 retired warheads, and that 300-400 warheads are dismantled each year.

Declassification of the back-end (dismantlement numbers) of the nuclear posture goes hand in hand with declassification of the front-end (stockpile size) because dismantlement numbers prove that the United States is actually getting rid of the weapons and not just putting them in storage. That is the key message that unnecessary secrecy prevents U.S. officials from being able to convey to the international nonproliferation community.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons

.By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States and Russia have some 1,800 nuclear warheads on alert on ballistic missiles that are ready to launch in a few minutes, according to a new study published by UNIDIR. The number of U.S. and Russian alert warheads is greater than the total nuclear weapons inventories of all other nuclear weapons states combined.

The report Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons is co-authored by Matthew McKinzie from the Natural Resources of Defense Council and yours truly.

France and Britain also keep some of their nuclear force on alert, although at lower readiness levels than the United States and Russia. No other nuclear weapon state has nuclear weapons on alert.

The report concludes that the warning made by opponents of de-alerting, that it could trigger a re-alerting race in a crisis that count undermine stability, is a “straw man” argument that overplays risks, downplays benefits, and ignores that current alert postures already include plans to increase readiness and alert rates in a crisis.

According to the report, “while there are risks with alerted and de-alerted postures, a re-alerting race that takes three months under a de-alerted posture is much preferable to a re-alerting race that takes only three hours under the current highly alerted posture. A de-alerted nuclear posture would allow the national leaders to think carefully about their decisions, rather than being forced by time constraints to choose from a list of pre-designated responses with catastrophic consequences.”

During his election campaign, Barack Obama promised to work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, but the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) instead decided to keep the existing alert posture. The post-NPR review that has now been completed but has yet to be announced hopefully will include a reduction of the alert level, not least because the Intelligence Community has concluded that a Russian surprise first strike is unlikely to occur.

The UNIDIR report finds that the United States and Russia previously have reduce the alert levels of their nuclear forces and recommends that they continue this process by removing the remaining nuclear weapons from alert through a phased approach to ensure stability and develop consultation and verification measures.

Full report: Reducing Alert Rates of Nuclear Weapons (FAS mirror)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Swiss Government. General nuclear forces research is supported by the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons Discussed in Warsaw

The conference was held in this elaborate room at the Intercontinental Warsaw hotel.

By Hans M. Kristensen

In early February, I participated in a conference in Warsaw on non-strategic nuclear weapons. The conference was organized by the Polish Institute of International Affairs, the Norwegian Institute for Defense Studies, and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland, with the participation of the U.S. State Department.

The conference had very high-level government representation from the United States and NATO, and included non-governmental experts from the academic and think-tank communities in Russia and NATO countries. The Russian government unfortunately did not send participants.

The United States and NATO want to broaden the arms control agenda to non-strategic nuclear weapons, which have so far largely eluded limitations and verification. The objective of the conference was to try to identify options for how NATO and Russia might begin to discuss confidence-building measures and eventually limitations on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The conference commissioned eight working papers to form the basis for the discussions. My paper, which focused on identifying common definitions for categories of non-strategic nuclear weapons, recommended starting with air-delivered weapons as the only compatible category for negotiations on U.S-Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Background: Working papers and lists of participants are available on the PISM web site. For background on non-strategic nuclear weapons, see this FAS report.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.