New Environmental Assessment Reveals Fascinating Alternatives to Land-Based ICBMs

A new Air Force environmental assessment reveals that it considered basing ICBMs in underground railway tunnels––or possibly underwater.

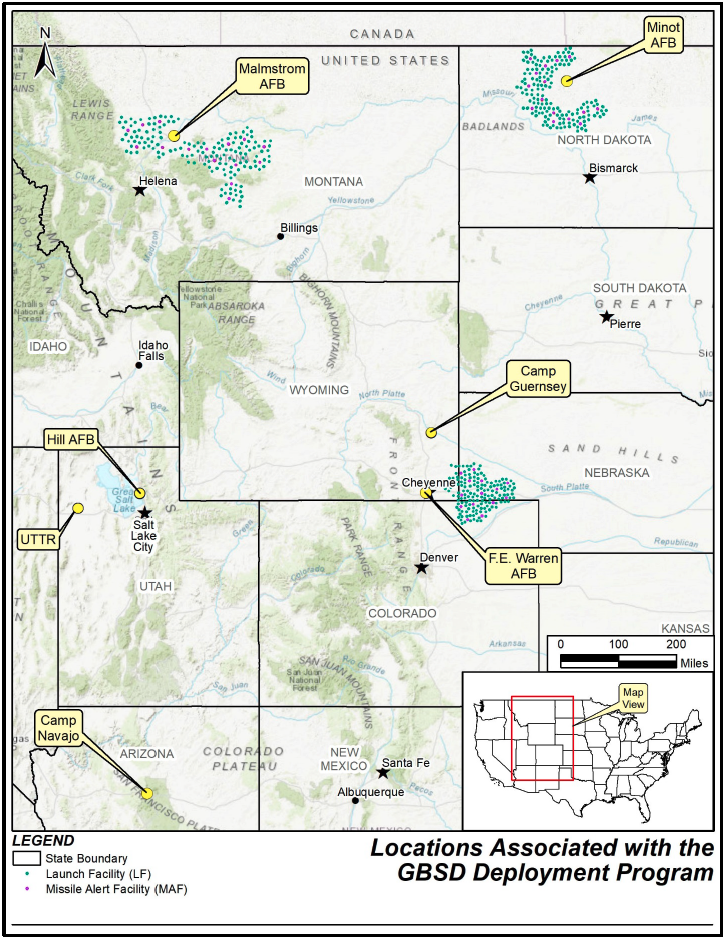

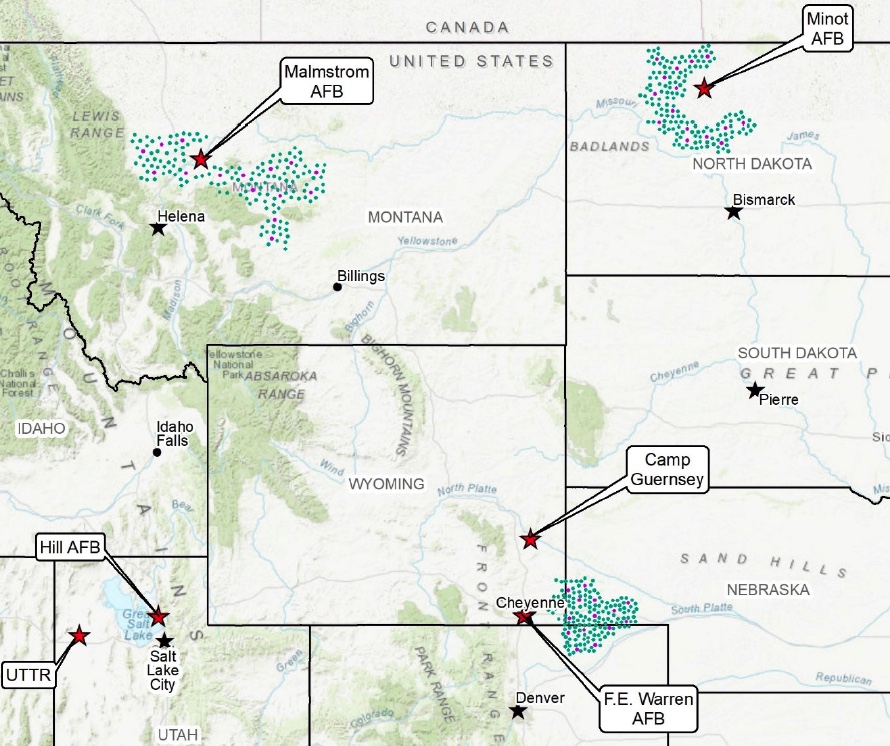

Map of the ICBM missile fields contained within the Air Force’s July 2022 assessment.

On July 1st, the Air Force published its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed ICBM replacement program, previously known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) and now by its new name, “Sentinel.” The government typically conducts an EIS whenever a federal program could potentially disrupt local water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other related factors.

A comprehensive environmental assessment is certainly warranted in this case, given the tremendous scale of the Sentinel program––which consists of a like-for-like replacement of all 400 Minuteman III missiles that are currently deployed across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, plus upgrades to the launch facilities, launch control centers, and other supporting infrastructure.

Cover page of the Air Force’s July 2022 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the GBSD.

The Draft EIS was anxiously awaited by local stakeholders, chambers of commerce, contractors, residents, and… me! Not because I’m losing sleep about whether Sentinel construction will disturb Wyoming’s Western Bumble Bee (although maybe I should be!), but rather because an EIS is also a wonderful repository for juicy, and often new, details about federal programs––and the Sentinel’s Draft EIS is certainly no exception.

Interestingly, the most exciting new details are not necessarily about what the Air Force is currently planning for the Sentinel, but rather about which ICBM replacement options they previously considered as alternatives to the current program of record. These alternatives were assessed during in the Air Force’s 2014 Analysis of Alternatives––a key document that weighs the risks and benefits of each proposed action––however, that document remains classified. Therefore, until they were recently referenced in the July 2022 Draft EIS, it was not clear to the public what the Air Force was actually assessing as alternatives to the current Sentinel program.

Missile alternatives

The Draft EIS notes that the Air Force assessed four potential missile alternatives to the current plan, which involves designing a completely new ICBM:

- Reproducing Minuteman III ICBMs to “existing specifications” by washing out and refilling the first- and second-stage rocket boosters; remanufacturing the third stages and Propulsion System Rocket Engine––the ICBM’s post-boost vehicle; and refurbishing and replacing all other subsystems;

The Air Force appears to have ultimately eliminated all four of these options from consideration because they did not meet all of their “selection standards,” which included criteria like sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure.

Of particular interest, however, is the Air Force’s note that the Minuteman III reproduction alternative was eliminated in part because it did not “meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs in the context of modern and evolving threats (e.g., range, payload, and effectiveness.” It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade.

This statement also suggests that “modern and evolving threats” are driving the need for an operationally improved ICBM; however, it is unclear what the Air Force is referring to, or how these threats would necessarily justify a brand-new ICBM with new capabilities. As I wrote in my March 2021 report, “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,”

“With respect to US-centric nuclear deterrence, what has changed since the end of the Cold War? China is slowly but steadily expanding its nuclear arsenal and suite of delivery systems, and North Korea’s nuclear weapons program continues to mature. However, the range and deployment locations of the US ICBM force would force the missiles to fly over Russian territory in the event that they were aimed at Chinese or North Korean targets, thus significantly increasing the risk of using ICBMs to target either country. Moreover, […] other elements of the US nuclear force––especially SSBNs––could be used to accomplish the ICBM force’s mission under a revised nuclear force posture, potentially even faster and in a more flexible manner. […] It is additionally important to note that even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload––not the missile itself. By the time that an adversary’s interceptor was able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would have already shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and would be guided solely by its reentry vehicle. Reentry vehicles and missile boosters can be independently upgraded as necessary, meaning that any concerns about adversarial missile defenses could be mitigated by deploying a more advanced payload on a life-extended Minuteman III ICBM.”

Of additional interest is the passage explaining why the Air Force dismissed the possibility of using the Trident II D5 SLBM as a land-based weapon:

“The D5 is a high-accuracy weapon system capable of engaging many targets simultaneously with overall functionality approaching that of land- based missiles. The D5 represents an existing technology, and substantial design and development cost savings would be realized; but the associated savings would not appreciably offset the infrastructure investment requirements (road and bridge enhancements) necessary to make it a land-based weapon system. In addition, motor performance and explosive safety concerns undermine the feasibility of using the D5 as a land-based weapon system.”

The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate. However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests: in 2015 the Navy conducted a successful Trident flight test using “the oldest 1st stage solid rocket motor flown to date” (over 26 years old), with 2nd and 3rd stage motors that were 22 years old. In January 2021, Vice Admiral Johnny Wolfe Jr.––the Navy’s Director for Strategic Systems Programs––remarked that “solid rocket motors, the age of those we can extend quite a while, we understand that very well.” This is largely due to the Navy’s incorporation of nondestructive testing techniques––which involve sending a probe into the bore to measure the elasticity of the propellant––to evaluate the reliability of their missiles.

As a result, the Navy is not currently contemplating the purchase of a brand-new missile to replace its current arsenal of Trident SLBMs, and instead plans to conduct a second life-extension to keep them in service until 2084. However, the Air Force’s comments suggest either a lack of confidence in this approach, or perhaps an institutional preference towards developing an entirely new missile system. [Note: Amy Woolf helpfully offered up another possible explanation, that the Air Force’s concerns could be related to the ability of the Trident SLBM’s cold launch system to perform effectively on land, given that these very different launch conditions could place additional stress on the missile system itself.]

Basing alternatives

The Draft EIS also notes that the Air Force assessed two fascinating––and somewhat familiar––alternatives for basing the new missiles: in underground tunnels and in “deep-lake silos.”

The tunnel option––which had been teased in previous programmatic documents but never explained in detail––would include “locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles”––and it is effectively a mashup of two concepts from the late Cold War.

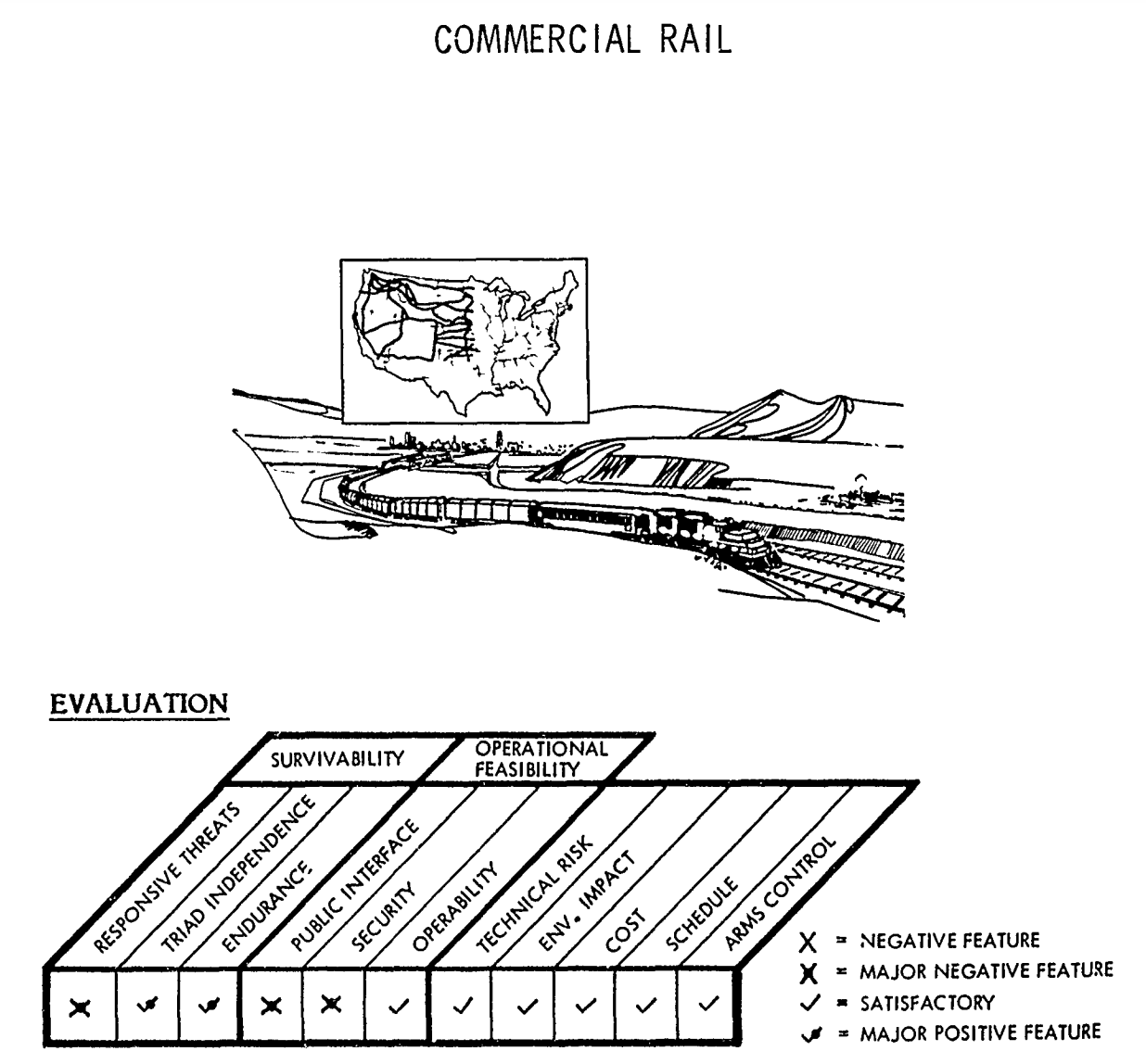

The rail concept was strongly considered during the development of the MX missile in the 1980s, although the plan called for missile trains to be dispersed onto the country’s existing civilian rail network, rather than into newly-built underground tunnels. Both the rail and tunnel concepts were referenced in one of my favourite Pentagon reports––a December 1980 Pentagon study called “ICBM Basing Options,” which considered 30 distinct and often bizarre ICBM basing options, including dirigibles, barges, seaplanes, and even hovercraft!

Illustrations of “Commercial Rail” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

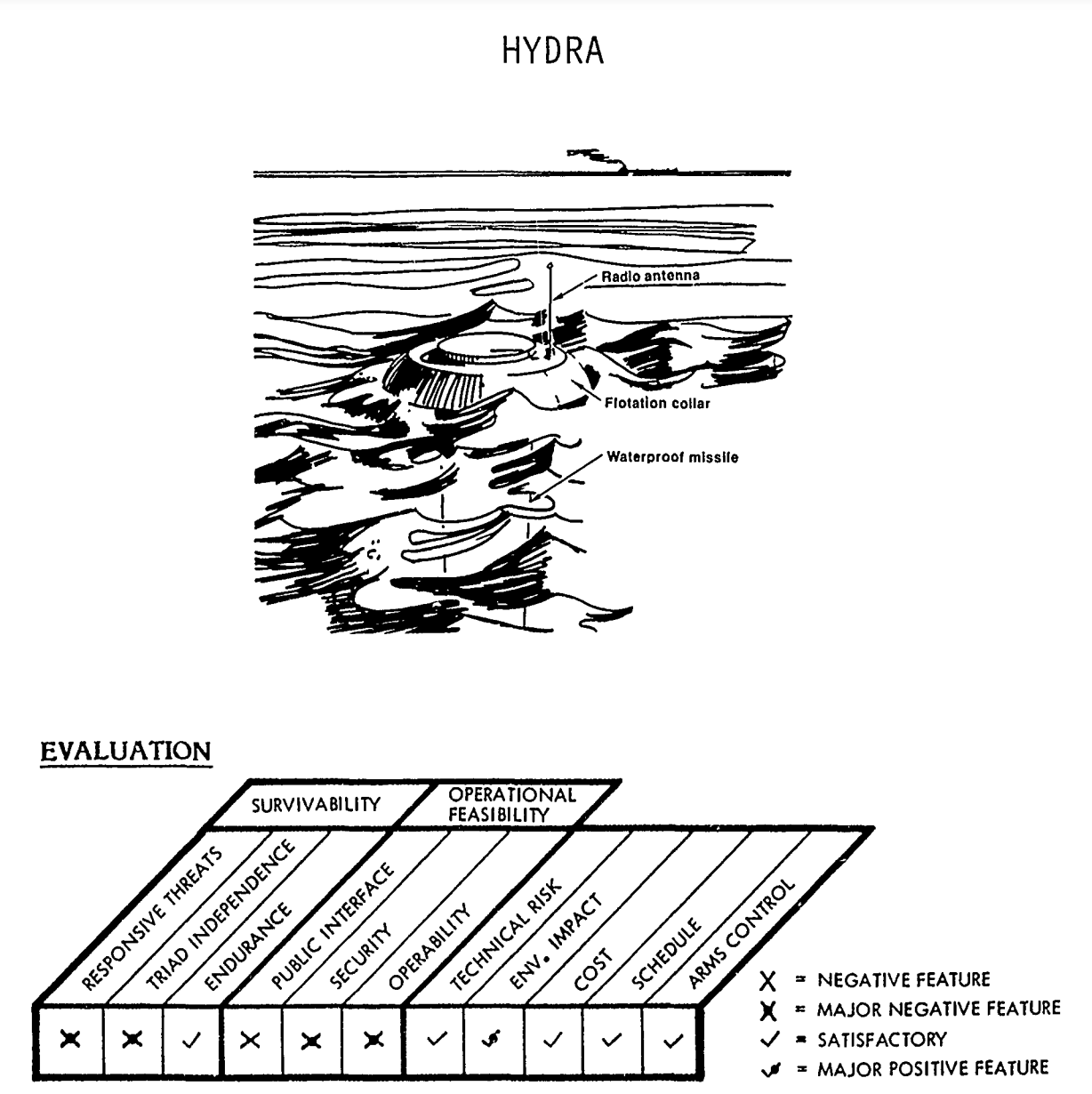

The second option––basing ICBMs in deep-lake silos––was also referenced in that same December 1980 study. The concept––nicknamed “Hydra”––proposed dispersing missiles across the ocean using floating silos, with “only an inconspicuous part of the missile front end [being] visible above the surface.” Interestingly, this raises the theoretical question of whether the Air Force would still maintain control over the ICBM mission, given that the missiles would be underwater.

Illustration of “Hydra” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

When considering alternative basing modes for the Sentinel ICBM, the Air Force eliminated both concepts due to cost prohibitions, and, in the case of underwater basing, a lack of confidence that the missiles would be safe and secure. This concern was also floated in the 1980 study as well, with the Pentagon acknowledging the likelihood that US adversaries and non-state actors “would also be engaged in a hunt for the Hydras. Not under our direct control, any missile can be destroyed or towed away (stolen) at leisure.”

Another potential option?

In addition to revealing these fascinating details about previously considered alternatives to the Sentinel program, the Draft EIS also highlighted a public comment suggesting that “the most environmentally responsible option” would simply be the reduction of the Minuteman III inventory.

The Air Force rejected the comment because it says that it is “required by law to accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground based strategic deterrent program;’” however, the public commenter’s suggestion is certainly a reasonable one. The current force level of 400 deployed ICBMs is not––and has never been––a magic number, and it could be reduced further for a variety of reasons, including those related to security, economics, or a good faith effort to reduce deployed US nuclear forces. In particular, as George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi wrote in a 2021 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, “This assumption that the ICBM force would not be eliminated or reduced before 2075 is difficult to reconcile with U.S. disarmament obligations under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.”

The security environment of the 21st century is already very different than that of the previous century. The greatest threats to Americans’ collective safety are non-militarized, global phenomena like climate change, domestic unrest and inequality, and public health crises. And recent polling efforts by ReThink Media, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Federation of American Scientists suggest that Americans overwhelmingly want the government to invest in more proximate social issues, rather than on nuclear weapons. To that end, rather than considering building new missile tunnels, it would likely be much more domestically popular to spend money on domestic priorities––perhaps new subway tunnels?

—

Background Information:

- “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,” Federation of American Scientists (Mar. 2021)

- “Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan,” Federation of American Scientists (Nov. 2020)

- ICBM Information Project, Federation of American Scientists

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and Longview Philanthropy. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Trump Administration Again Refuses To Disclose Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Size

The Trump administration has denied a request from the Federation of American Scientists to disclose the size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile and the number of dismantled warheads.

The denial was made by the Department of Defense Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) in response to a petition from Steven Aftergood, director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, “that the Department of Energy (and the Department of Defense) authorize declassification of the size of the total U.S, nuclear stockpile and the number of weapons dismantled as of the end of fiscal year 2020.”

The decision to deny release of the data contradicts past US disclosure of such information, undercuts US criticism of secrecy in other nuclear-armed states, and weakens US ability to document its adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. As Aftergood explained in the petition letter:

[su_quote]We believe that the reasons that led to the previous declassifications of stockpile information are still valid. The benefits of declassification are substantial while the detrimental consequences, if any, are insignificant.

As the first nuclear weapons state, the United States should strive to set a global example for clarity and transparency in nuclear weapons policy by disclosing its current stockpile size. Ambiguity is not helpful to anyone in this context.

Far from diminishing security, a credible USG account of its stockpile size both enhances deterrence and serves as a confidence building measure. Even if other nations do not immediately follow our lead, stockpile declassification sends a valuable message. And at a time when the future of US nuclear weapons policy is under discussion in Congress and elsewhere, stockpile disclosure also helps to provide a factual foundation for ongoing public deliberation.[/su_quote]

In its denial letter, the DOD Formerly Restricted Data Declassification Working Group (FDR DWG) did not respond to these points and gave no reason for the denial other than stating that “the information requested cannot be declassified at this time.”

Stockpile Size and Developments

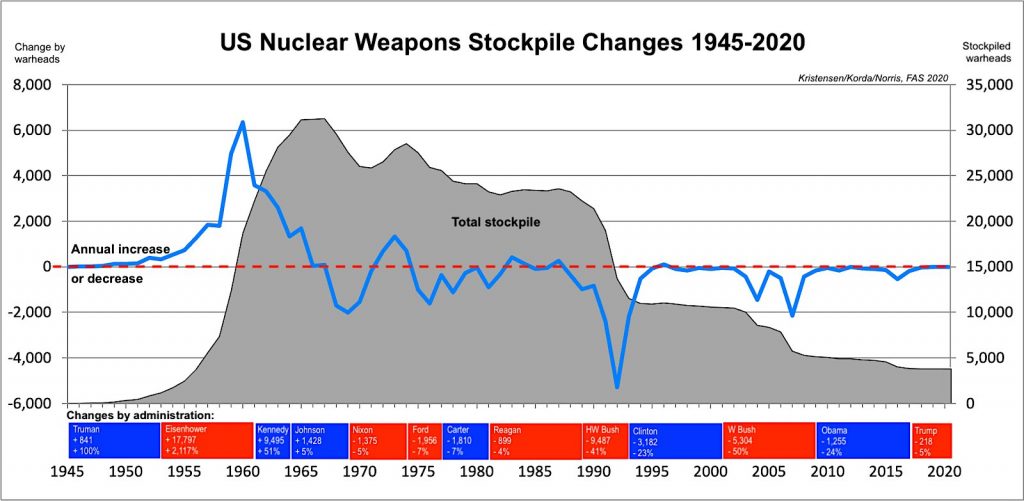

The decision to deny declassification of the warhead stockpile and dismantlement numbers contradicts the publication of such data between 2010 and 2017 during which the Obama administration released annual numbers as well as the entire history of the stockpile size going back to 1945.

The decision also contradicts the decision in 2018 to declassify the data for 2017, the first year of the Trump administration.

In 2019, however, the Trump administration suddenly, and without explanation, decided to withhold the stockpile data.

The available data shows significant fluctuations in the size of the US stockpile over the years depending on how the various administrations increased or decreased the number of nuclear weapons. The graph below shows the size of the stockpile over the years and the in- and out-flux of warheads from the stockpile. As far as we can gauge, the stockpile has remained relatively stable for the past three years at around 3,800 warheads. And the number of warheads dismantled per year is probably currently in the order of 300-350.

The size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile has fluctuated considerably over the years but remained relatively stable during the Trump administration. Click on image to view full size.

Implications and Recommendations

The decision by the Trump administration to deny declassification of the nuclear weapons stockpile size and dismantlement numbers contradict release of such data in the past for no apparent reason.

The increased secrecy of the US nuclear weapons arsenal comes at a time when the Trump administration has been criticizing China for “its secretive, nuclear crash buildup…” The administration’s criticism would carry a lot more weight if it didn’t hide its own stockpile behind a “great wall of secrecy.”

In addition to undercutting the US ability to push for greater transparency among other nuclear-armed states, the decision to classify warhead stockpile and dismantlement data also weakens the ability of the United States to demonstrate good faith on its efforts to continue to reduce its nuclear arsenal in the context of the upcoming review conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The decision enables conspiracists to spread false rumors that the United States is secretly increasing its nuclear arsenal.

The incoming Biden administration should overturn the Trump administration’s excessive and counterproductive nuclear secrecy and restore transparency of the US nuclear warhead stockpile and dismantlement data.

Background Information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

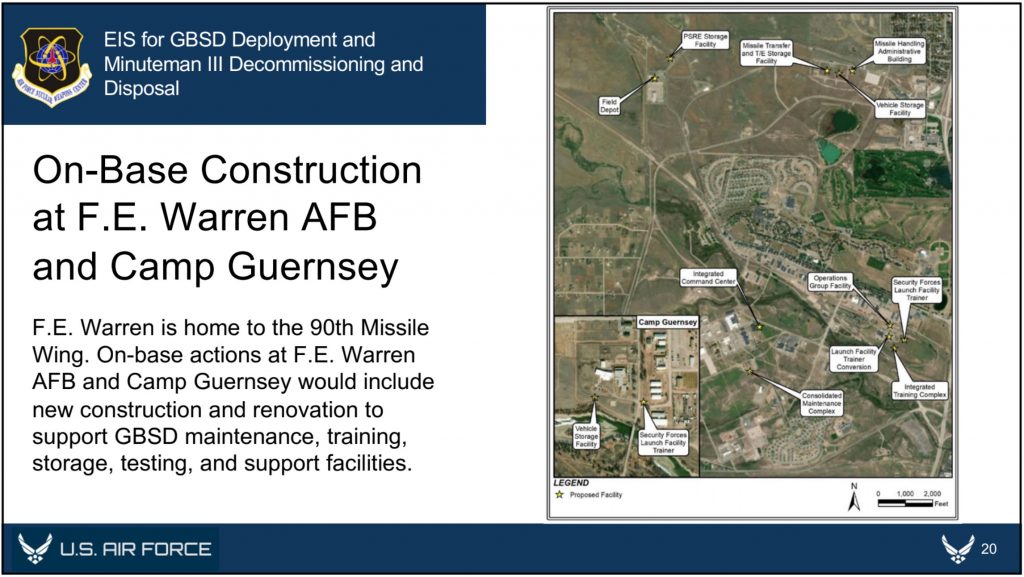

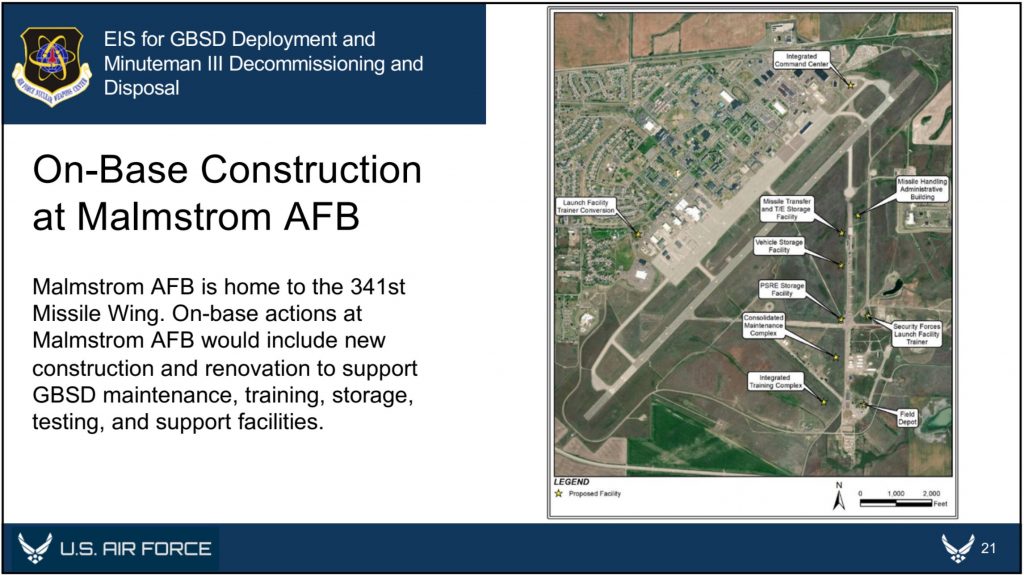

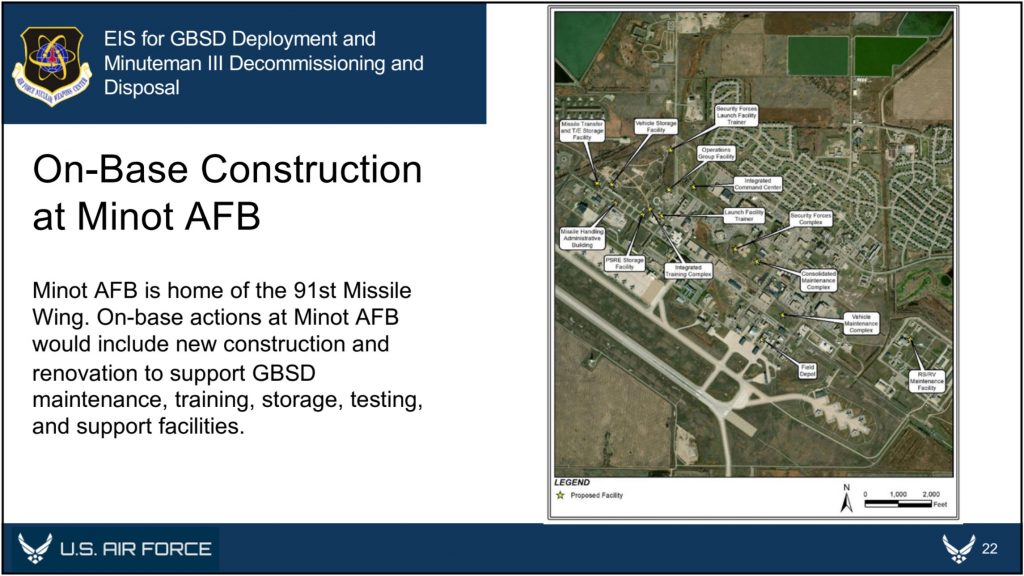

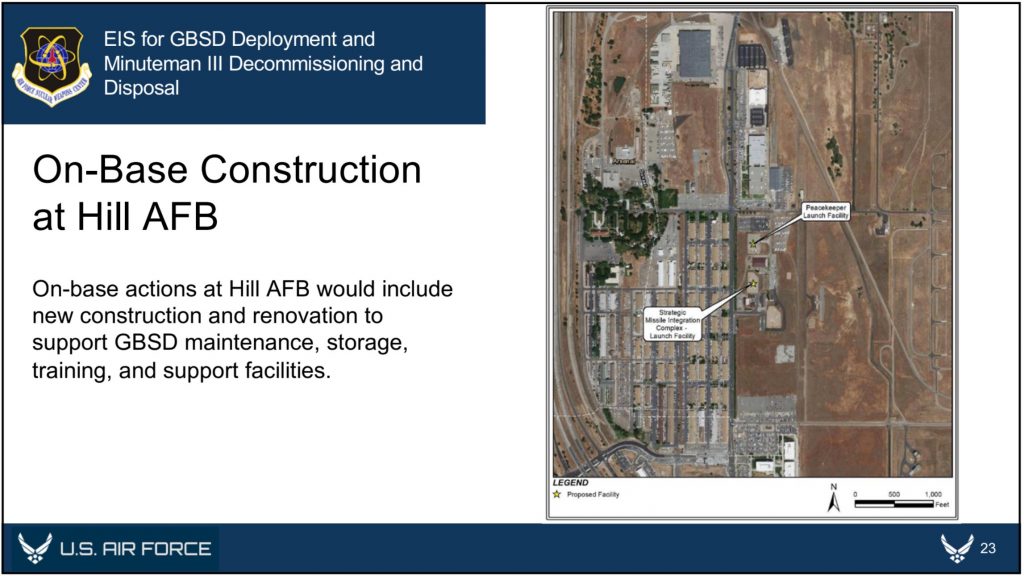

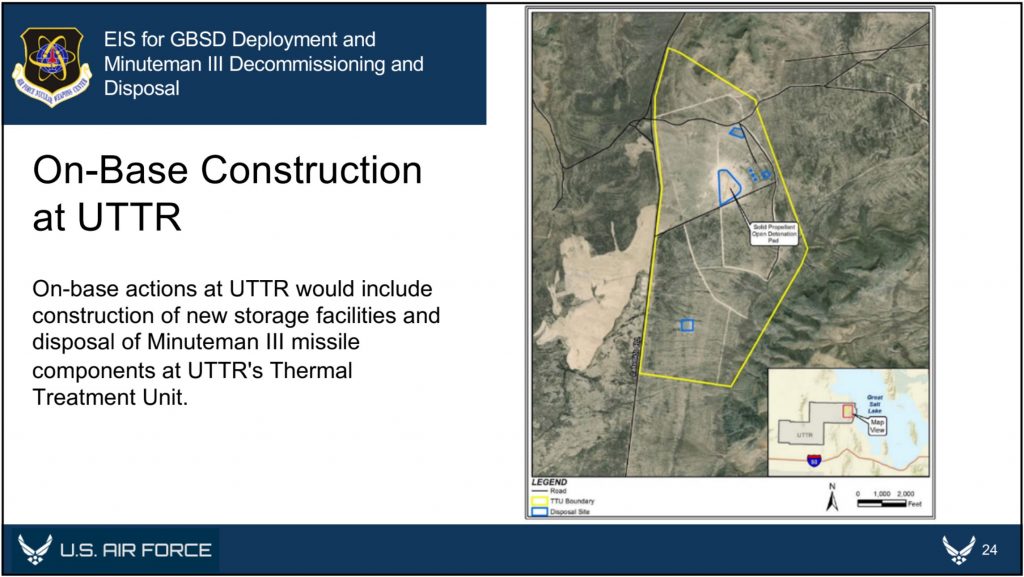

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

Mixed Messages On Trump’s Missile Defense Review

President Trump personally released the long-overdue Missile Defense Review (MDR) today, and despite the document’s assertion that “Missile Defenses are Stabilizing,” the MDR promotes a posture that is anything but.

Firstly, during his presentation, Acting Defense Secretary Shanahan falsely asserted that the MDR is consistent with the priorities of the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). The NSS’ missile defense section notes that “Enhanced missile defense is not intended to undermine strategic stability or disrupt longstanding strategic relationships with Russia or China.” (p.8) During Shanahan’s and President Trump’s speeches, however, they made it clear that the United States will seek to detect and destroy “any type of target,” “anywhere, anytime, anyplace,” either “before or after launch.” Coupled with numerous references to Russia’s and China’s evolving missile arsenals and advancements in hypersonic technology, this kind of rhetoric is wholly inconsistent with the MDR’s description of missile defense being directed solely against “rogue states.” It is also inconsistent with the more measured language of the National Security Strategy.

Secondly, the MDR clearly states that the United States “will not accept any limitation or constraint on the development or deployment of missile defense capabilities needed to protect the homeland against rogue missile threats.” This is precisely what concerns Russia and China, who fear a future in which unconstrained and technologically advanced US missile defenses will eventually be capable of disrupting their strategic retaliatory capability and could be used to support an offensive war-fighting posture.

Thirdly, in a move that will only exacerbate these fears, the MDR commits the Missile Defense Agency to test the SM-3 Block IIA against an ICBM-class target in 2020. The 2018 NDAA had previously mandated that such a test only take place “if technologically feasible;” it now seems that there is sufficient confidence for the test to take place. However, it is notable that the decision to conduct such a test seems to hinge upon technological capacity and not the changes to the security environment, despite the constraints that Iran (which the SM-3 is supposedly designed to counter) has accepted upon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

Fourthly, the MDR indicates that the United States will look into developing and fielding a variety of new capabilities for detecting and intercepting missiles either immediately before or after launch, including:

- Developing a defensive layer of space-based sensors (and potentially interceptors) to assist with launch detection and boost-phase intercept.

- Developing a new or modified interceptor for the F-35 that is capable of shooting down missiles in their boost-phase.

- Mounting a laser on a drone in order to destroy missiles in their boost-phase. DoD has apparently already begun developing a “Low-Power Laser Demonstrator” to assist with this mission.

There exists much hype around the concept of boost-phase intercept—shooting down an adversary missile immediately after launch—because of the missile’s relatively slower velocity and lack of deployable countermeasures at that early stage of the flight. However, an attempt at boost-phase intercept would essentially require advance notice of a missile launch in order to position US interceptors within striking distance. The layer of space-based sensors is presumably intended to alleviate this concern; however, as Laura Grego notes, these sensors would be “easily overwhelmed, easily attacked, and enormously expensive.”

Additionally, boost-phase intercept would require US interceptors to be placed in very close proximity to the target––almost certainly revealing itself to an adversary’s radar network. The interceptor itself would also have to be fast enough to chase down an accelerating missile, which is technologically improbable, even years down the line. A 2012 National Academy of Sciences report puts it very plainly: “Boost-phase missile defense—whether kinetic or directed energy, and whether based on land, sea, air, or in space—is not practical or feasible.”

Overall, the Trump Administration’s Missile Defense Review offers up a gamut of expensive, ineffective, and destabilizing solutions to problems that missile defense simply cannot solve. The scope of US missile defense should be limited to dealing with errant threats—such as an accidental or limited missile launch—and should not be intended to support a broader war-fighting posture. To that end, the MDR’s argument that “the United States will not accept any limitation or constraint” on its missile defense capabilities will only serve to raise tensions, further stimulate adversarial efforts to outmaneuver or outpace missile defenses, and undermine strategic stability.

During the upcoming spring hearings, Congress will have an important role to play in determining which capabilities are actually necessary in order to enforce a limited missile defense posture, and which ones are superfluous. And for those superfluous capabilities, there should be very strong pushback.

Israel’s Official Map Replaces Military Bases with Fake Farms and Deserts

Somewhat unexpectedly, a blog post that I wrote last week caught fire internationally. On Monday, I reported that Yandex Maps—Russia’s equivalent to Google Maps—had inadvertently revealed over 300 military and political facilities in Turkey and Israel by attempting to blur them out.

In a strange turn of events, the fallout from that story has actually produced a whole new one.

After the story blew up, Yandex pointed out that its efforts to obscure these sites are consistent with its requirement to comply with local regulations. Yandex’s statement also notes that “our mapping product in Israel conforms to the national public map published by the government of Israel as it pertains to the blurring of military assets and locations.”

The “national public map” to which Yandex refers is the official online map of Israel which is maintained by the Israeli Mapping Centre (מרכז למיפוי ישראל) within the Israeli government. Since Yandex claims to take its cue from this map, I wondered whether that meant that the Israeli government was also selectively obscuring sites on its national map.

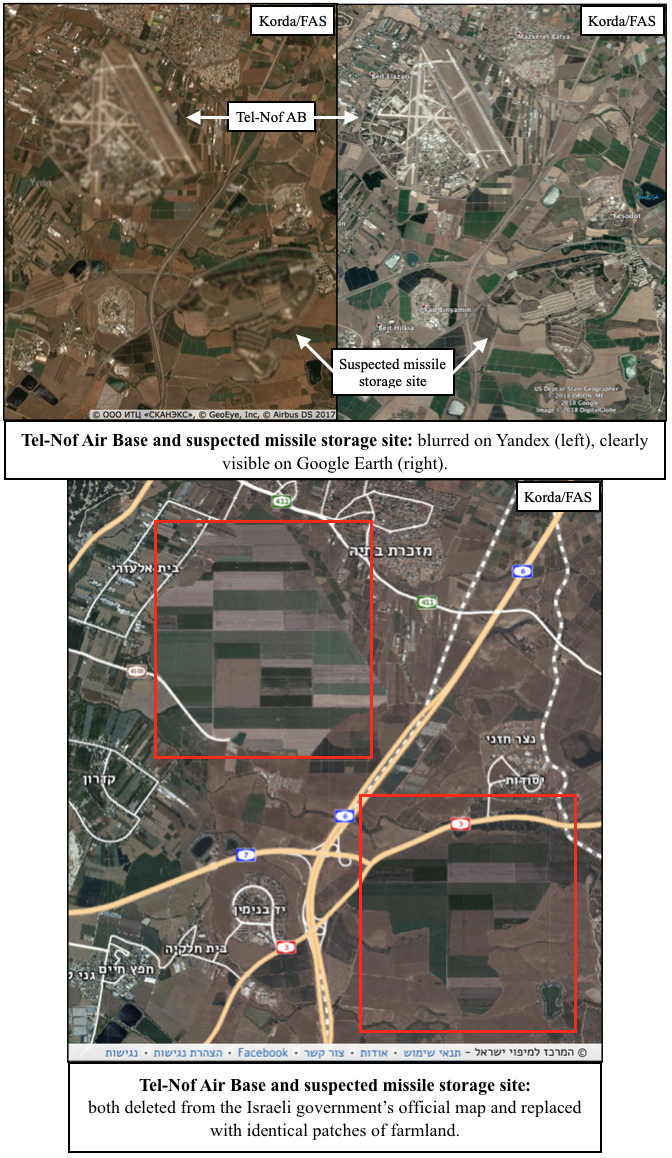

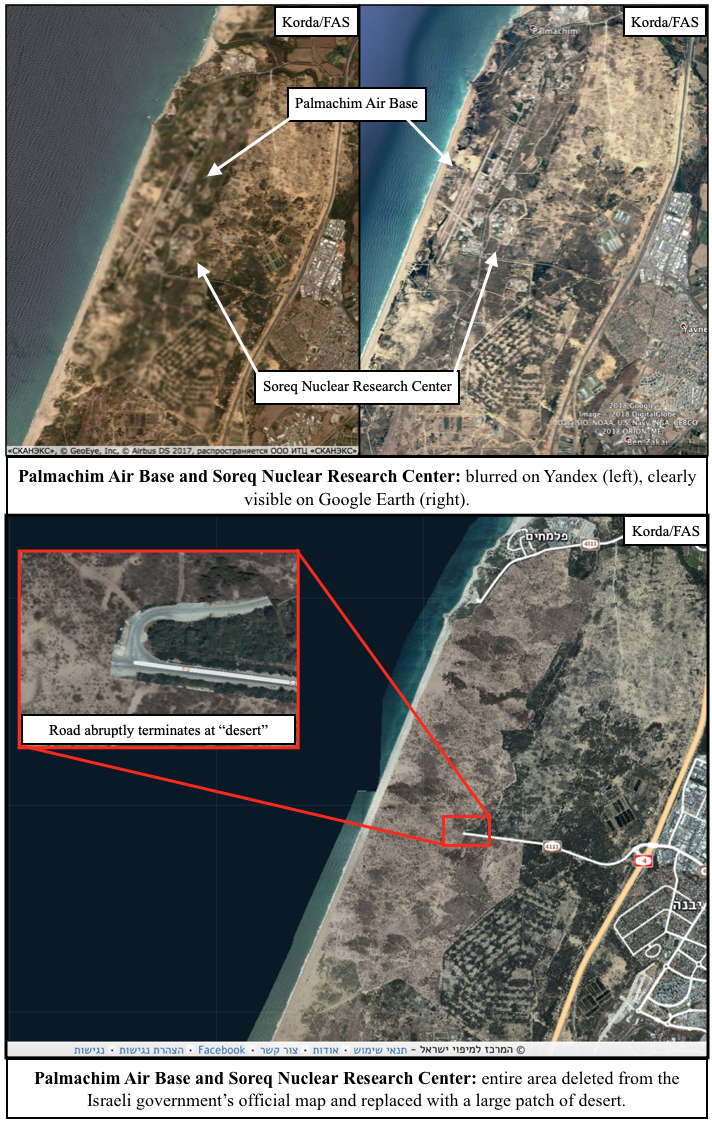

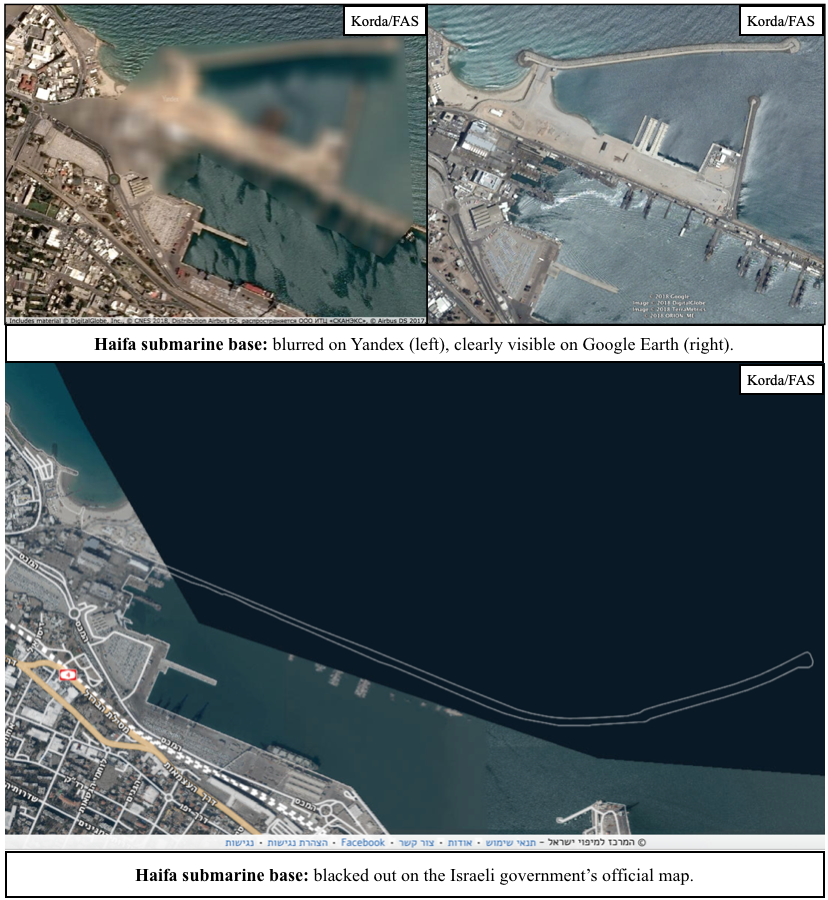

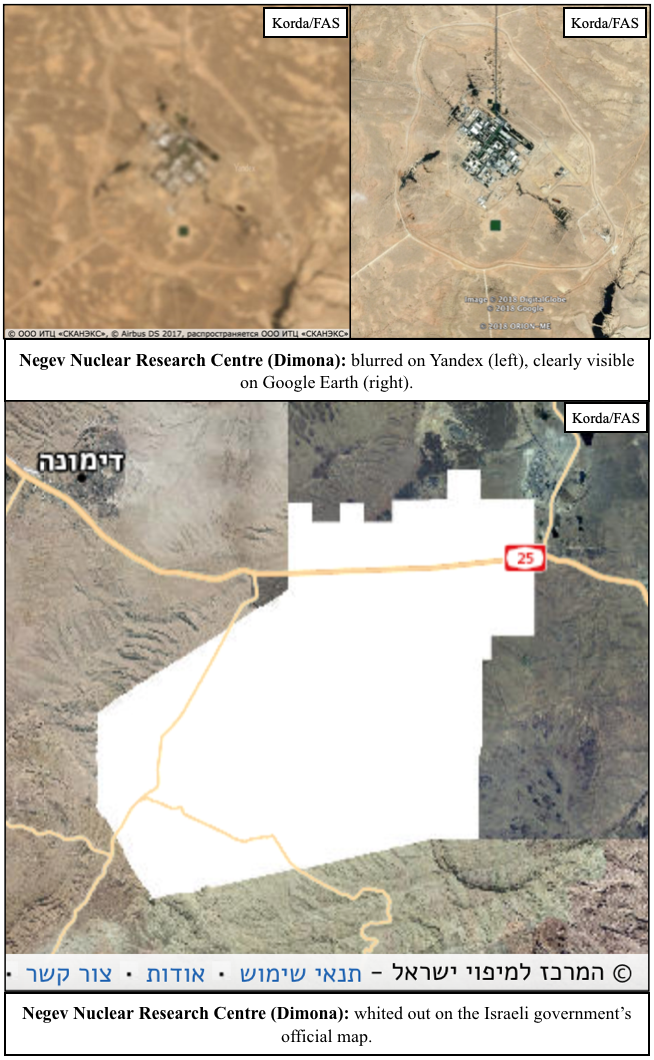

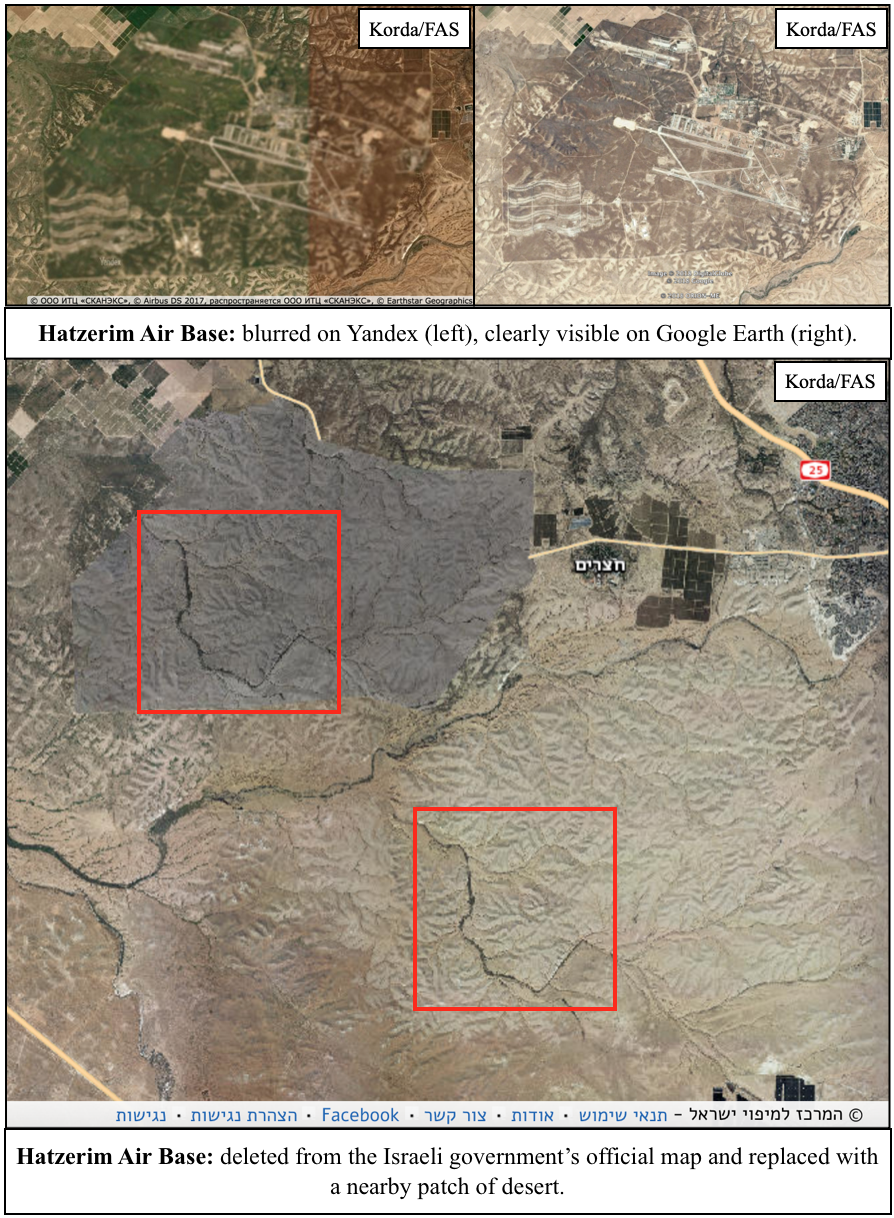

I wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Israeli government goes well beyond just blurring things out. They’re actually deleting entire facilities from the map—and quite messily, at that. Usually, these sites are replaced with patches of fake farmland or desert, but sometimes they’re simply painted over with white or black splotches.

Some of the more obvious examples of Israeli censorship include nuclear facilities:

- Tel-Nof Air Base is just down the road from a suspected missile storage site, both of which have been painted over with identical patches of farmland.

- Palmachim Air Base doubles as a test launch site for Jericho missiles and is collocated with the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, which is rumoured to be responsible for nuclear weapons research and design. The entire area has been replaced with a fake desert.

- The Haifa Naval Base includes pens for submarines that are rumoured to be nuclear-capable, and is entirely blacked out on the official map.

- The Negev Nuclear Research Center at Dimona is responsible for plutonium and tritium production for Israel’s nuclear weapons program, and has been entirely whited out on the official map.

- Hatzerim Air Base has no known connection to Israel’s nuclear weapons program; however, the sloppy method that was used to mask its existence (by basically just copy-pasting a highly-distinctive and differently-coloured patch of desert to an area only five kilometres away) was too good to leave out.

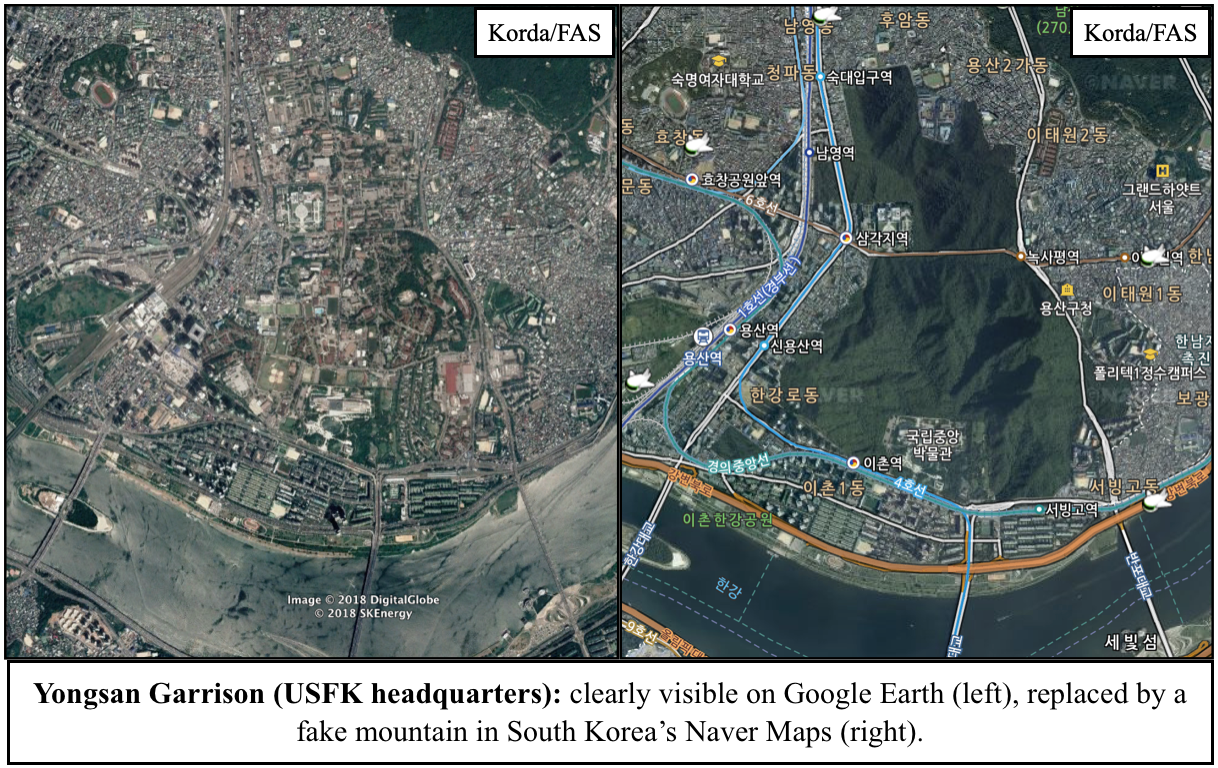

Given that all of these locations are easily visible through Google Earth and other mapping platforms, Israel’s official map is a prime example of needless censorship. But Israel isn’t the only one guilty of silly secrecy: South Korea’s Naver Maps regularly paints over sensitive sites with fake mountains or digital trees, and in a particularly egregious case, the Belgian Ministry of Defense is actually suing Google for not complying with its requests to blur out its military facilities.

Before the proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery, obscuring aerial photos of military facilities was certainly an effective method for states to safeguard their sensitive data. However, now that anyone with an internet connection can freely access these images, it simply makes no sense to persist with these unnecessary censorship practices–especially since these methods can often backfire and draw attention to the exact sites that they’re supposed to be hiding.

Case studies like Yandex and Strava—in which the locations of secret military facilities were revealed through the publication of fitness heat-maps—should prompt governments to recognize that their data is becoming increasingly accessible through open-source methods. Correspondingly, they should take the relevant steps to secure information that is absolutely critical to national security, and be much more publicly transparent with information that is not—hopefully doing away with needless censorship in the process.

Accounting Board Okays Deceptive Budget Practices

Government agencies may remove or omit budget information from their public financial statements and may present expenditures that are associated with one budget line item as if they were associated with another line item in order to protect classified information, the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board concluded last week.

Under the newly approved standard, government agencies may “modify information required by other [financial] standards” in their public financial statements, omit otherwise required information, and misrepresent the actual spending amounts associated with specific line items so that classified information will not be disclosed. (Accurate and complete accounts are to be maintained separately so that they may be audited in a classified environment.)

See Classified Activities, Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards (SFFAS) 56, Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, October 2018.

The new policy was favored by national security agencies as a prudent security measure, but it was opposed by some government overseers and accountants.

Allowing unacknowledged modifications to public financial statements “jeopardizes the financial statements’ usefulness and provides financial managers with an arbitrary method of reporting accounting information,” according to comments provided to the Board by the Department of Defense Office of Inspector General.

Properly classified information should be redacted, not misrepresented, said the accounting firm Kearney & Company. “Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) should not be modified to limit reporting of classified activities. Rather, GAAP reporting should remain the same as other Federal entities and redacted for public release or remain classified.”

The new policy, which extends deceptive budgeting practices that have long been employed in intelligence budgets, means that public budget documents must be viewed critically and with a new degree of skepticism.

A classified signals intelligence program dubbed “Vesper Lillet” that recently became the subject of a fraud indictment was ostensibly sponsored by the Department of Health and Human Services, but in reality it involved a joint effort of the National Reconnaissance Office and the National Security Agency.

See “Feds allege contracting fraud within secret Colorado spy warehouse” by Tom Roeder, The Gazette (Colorado Springs), October 5, 2018.

Financial Accounts May Be “Modified” to Shield Classified Programs

In an apparent departure from “generally accepted accounting principles,” federal agencies will be permitted to publish financial statements that are altered so as to protect information on classified spending from disclosure.

The new policy was developed by the government’s Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) in response to concerns raised by the Department of Defense and others that a rigorous audit of agency financial statements could lead to unauthorized disclosure of classified information.

In order to prevent disclosure of classified information in a public financial statement, FASAB said that agencies may amend or obscure certain spending information. “An entity may modify information required by other [accounting] standards if the effect of the modification does not change the net results of operations or net position.”

Agencies may also shift accounts around in a potentially misleading way. “A component reporting entity is allowed to be excluded from one reporting entity and consolidated into another reporting entity. The effect of the modifications may change the net results of operations and/or net position.” See Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards 56, FASAB, July 5, 2018 (final draft for sponsor review).

In response to an earlier draft of the new standard that was issued last December, most government agencies endorsed the move to permit modifying public financial statements.

“The protection of classified information and national security takes precedence over financial statements,” declared the Central Intelligence Agency in its comments (submitted discreetly under the guise of an “other government agency”).

“It is in the best interest of national security to allow for modification to the presentation of balances and reporting entity in the GPFFR [the publicly available General Purpose Federal Financial Report],” CIA wrote.

But in a sharply dissenting view, the Pentagon’s Office of Inspector General said the new approach was improper, unwise and unnecessary.

It “jeopardizes the financial statements’ usefulness and provides financial managers with an arbitrary method of reporting accounting information,” the DoD OIG said.

“We do not agree that incorporating summary-level dollar amounts in the overall statements will necessarily result in the release of classified information.”

“This proposed guidance is a major shift in Federal accounting guidance and, in our view, the potential impact is so expansive that it represents another comprehensive basis of accounting.”

“The Board should clarify whether this proposed standard, or subsequent Interpretations, could permit entities to record misstated amounts in the financial statements to mislead readers with the stated purpose of protecting classified information. We believe that no accounting guidance should allow this type of accounting entry.”

“We do not believe that… the Board’s proposed guidance would effectively protect classified information, comply with GAAP [generally accepted accounting principles], or serve the public interest,” the DoD OIG wrote.

The Kearney & Company accounting firm also objected, saying that it would be better to classify certain financial statements or redact classified spending than to misrepresent published information.

“Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) should not be modified to limit reporting of classified activities. Rather, GAAP reporting should remain the same as other Federal entities and redacted for public release or remain classified.”

If a published account is modified “so material activity is no longer accurately presented to the reader of financial statements, its usefulness to public users is limited and subject to misinterpretation.”

“This approach limits the value, usefulness, and benefits of financial statements as currently defined by GAAP. Financial statements of classified entities should remain classified or redacted like other classified documents before release to the public.”

“The integrity of current GAAP as it applies to all Federal entities should be retained,” Kearney said in its comments.

But the FASAB ultimately rejected those views.

“The Board determined that options other than those permitted in this Statement may not always adequately resolve national security concerns,” according to the final draft of the policy, which the Board provided to Secrecy News.

“Without this Statement, there is a risk that reporting entities may need to classify their entire financial statements to comply with existing accounting standards, which would likely result in the need to classify a large portion of the government-wide financial statements.”

In practice, the Board suggested, “Modifications may not be needed to prevent the disclosure of certain classified information. Therefore, this Statement permits, rather than requires, modifications on a case-by-case basis.”

The new accounting standard is expected to be approved by the FASAB sponsors — namely the Secretary of Treasury, the Comptroller General, and the Director of the Office of Management and Budget — by the end of a 90 day review period in October.

Last month, the FASAB issued a separate classified “Interpretation” of the new standard that addressed the policy’s implementation in detail. The contents of that document are not publicly known.

The topic of accounting for classified spending has been a challenging one for the Board, said Assistant Director Monica R. Valentine on Monday. “This is the first time we’ve had to deal with this sort of issue.”

Pentagon Audit: “There Will Be Unpleasant Surprises”

For the first time in its history, the Department of Defense is now undergoing a financial audit.

The audit, announced last December, is itself a major undertaking that is expected to cost $367 million and to involve some 1200 auditors. The results are to be reported in November 2018.

“Until this year, DoD was the only large federal agency not under full financial statement audit,” Pentagon chief financial officer David L. Norquist told the Senate Budget Committee in March. Considering the size of the Pentagon, the project is “likely to be the largest audit ever undertaken,” he said.

The purpose of such an audit is to validate the agency’s financial statements, to detect error or fraud, to facilitate oversight, and to identify problem areas. Expectations regarding the outcome are moderate.

“DOD is not generally expected to receive an unqualified opinion [i.e. an opinion that affirms the accuracy of DoD financial statements] on its first-ever, agency-wide audit in FY2018,” the Congressional Research Service said in a new report last week. See Defense Primer: Understanding the Process for Auditing the Department of Defense, CRS In Focus, June 26, 2018.

In fact, “It took the Department of Homeland Security, a relatively new and much smaller enterprise, about ten years to get to its first clean opinion,” Mr. Norquist noted at the March Senate hearing.

In the case of the DoD audit, “I anticipate the audit process will uncover many places where our controls or processes are broken. There will be unpleasant surprises. Some of these problems may also prove frustratingly difficult to fix.”

“But the alternative is to operate in ignorance of the challenge and miss the opportunity to reform. Fixing these vulnerabilities is essential to avoid costly or destructive problems in the future,” Mr. Norquist said.

STRATCOM Commander “Hates” Some Press Reports

“I hate the stuff that shows up in the press,” said Gen. John E. Hyten, commander of U.S. Strategic Command, at a congressional hearing on nuclear deterrence last March, the record of which has just been published.

Gen. Hyten was responding to a question from Rep. Austin Scott (R-GA) about the volume of unclassified information that gets released concerning the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD).

“General Hyten, we have seen a lot of GBSD acquisition details loaded into unclassified acquisition databases and run by the Air Force,” said Rep. Scott. “We all know that Russia, China, and others scoop all this stuff up to the best of their abilities and analyze it intensively.”

“Why is all of this put out in the open? Should we reassess what is unclassified in these acquisition documents?” Rep. Scott wanted to know.

“I hate the stuff that shows up in the press,” Gen. Hyten replied. “I think we should reassess that.”

“Just to complete that thought, I hate the fact that cost estimates show up in the press as well,” he added. “So I would really like to figure out a different way to do business than that. I hate seeing that kind of information in the newspaper.”

See Military Assessment of Nuclear Deterrence Requirements, hearing before the House Armed Services Committee, March 8, 2017.

In answer to another question at the hearing, Gen. Hyten denied that US nuclear forces are on “hair trigger alert.”

“Our nuclear command and control system is constantly exercised to ensure that only the President, after consultations with his senior advisors and military leaders, can authorize any employment of our nuclear forces,” he said.

On the other hand, Gen. Paul Selva, Vice Chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said that the time available for a President to make a decision about a nuclear strike could be highly compressed depending on the scenario.

“The launch-on-warning criteria basically are driven by physics,” he said at the hearing. “The amount of time the President has to make a decision is based on when we can detect a launch [and] what it takes to physically characterize the launch.”

“I don’t believe the physics let us give him much more time,” Gen. Selva said.

Executive Branch Oversight, Here & There

Government oversight can take diverse forms even among Western democracies.

A new report from the Law Library of Congress surveys the mechanisms of parliamentary oversight of the executive branch in Canada, Germany, Italy, Japan, Poland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In Sweden, for example, “Any member of the public may ask the JO [Justitieombudsman, or parliamentary ombudsman] to investigate a breach of law committed by an agency or employee. The complaint must be made in writing and cannot be anonymous.”

The Law Library report does not provide comparative analysis, but simply presents a descriptive summary of each nation’s government oversight practices, with links to additional resources. Any policy conclusions to be drawn are left to the reader.

See Parliamentary Oversight of the Executive Branch, Law Library of Congress, August 2017.

ODNI: Annexes to Intelligence Bills are not “Secret Law”

A recent article in Secrecy News indicated that the classified annexes that accompany the annual intelligence authorization bills are legally binding and constitute “secret law” (A Growing Body of Secret Intelligence Law, May 4).

Robert S. Litt, the General Counsel of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, wrote in last week to dispute that characterization:

I read your piece on secret law and the classified annex to the Intelligence

Authorization bills with interest. I thought it was worth responding to let you know

that I believe you are incorrect in saying that the classified annex has the force of

law. Each year’s Intelligence Authorization Act contains a provision — usually

Section 102 in recent years — that provides that the amounts authorized to be

appropriated are those set out in the schedule of authorizations in the classified

annex. It is only that schedule of authorizations that has the force of law. The

remainder of the annex is report language explaining the positions of the committee

on a variety of issues, and has no more force than any other committee report. That

is to say, it expresses the views of the Congress, and it therefore would ordinarily be

followed as a matter of comity, but does not have the force of law.

In this regard, it is worth noting that the unclassified Joint Explanatory Statement

accompanying the Intelligence Authorization Act for FY 2015 states (160 Cong. Rec.

S6464, Dec. 9, 2014):

“This joint explanatory statement shall have the same effect with respect to the

implementation of this Act as if it were a joint explanatory statement of a

committee of conference.

“This explanatory statement is accompanied by a classified annex that contains

a classified Schedule of Authorizations. The classified Schedule of

Authorizations is incorporated by reference in the Act and has the legal status of

public law.”

Bob Litt

In short: The schedule of authorized amounts that is contained within the classified annex does have the force of law, but the rest of the classified annex does not.

We accept the correction.

A congressional intelligence committee staff member concurred.

“The majority of the classified annexes are distinct from the schedules of authorization and are where the Committees opine on and direct various things,” the staff member said. “As a technical point, I believe that Bob is correct — they don’t have the force of law as they are not incorporated in the same way as the schedules.”

“That said, we very much expect that the Executive Branch will follow them, which in fact it does. I don’t know that this matters much, though. While it may not be secret law, it is secret text that the Congress approves and is presented to the President at the time of his signature and that we believe is binding in practical terms,” the staff member added.

Thus, even if they do not entirely qualify as “secret law,” the classified annexes still have normative force, helping to shape the direction and execution of intelligence policy.

They therefore retain their significance for government accountability, including congressional accountability. And yet as a category of documents, the annexes are completely withheld from the public even decades after they are produced. Unfortunately, that remains undisputed.

* * *

Its specific content aside, Mr. Litt’s message is noteworthy as an uncommon act of official participation in public dialog.

In an open society, government officials ought to be reasonably accessible to the members of the public whom they ostensibly serve. But with some exceptions, they are not. Either they are insulated by layers of security, or they are isolated by hierarchical bureaucratic structures that make them unreachable. The secrecy-intensive culture of intelligence only aggravates the problem. Even an open government law like the Freedom of Information Act creates a procedural buffer that often impedes any kind of direct dialog.

Unlike most of his colleagues, Mr. Litt has been willing to engage with members of the public with some frequency. You can ask him a question. You can argue with him. He will argue with you. The point is that he is available to non-governmental interlocutors in a way that should be ordinary but is in fact unusual and exemplary. (See, for example, here, here and here.)

Mr. Litt’s attentiveness to the nuances of an article in Secrecy News brings to mind a passage from Robert M. Gates’ 1996 CIA memoir From the Shadows that is dear to the heart of small newsletter writers. The author was recalling Director of Central Intelligence Bill Casey whom he described as an omnivorous consumer of information from even the most obscure sources.

“Bill Casey was one of the smartest people I have ever known and certainly one of the most intellectually lively,” Gates wrote (p. 217). “He subscribed to newsletters and information sheets that I sometimes thought couldn’t have more than five readers in the world, and then he would ask if I had seen one or another item in them.”

Making Government Accountability Work

The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly recognize a “public right to know.” But without reliable public access to government information, many features of constitutional government would not make sense. Citizens would not be able to evaluate the performance of their elected officials. Freedom of speech and freedom of the press would be impoverished. Americans’ ability to hold their government accountable for its actions would be neutered.

The conditions that make government accountability possible and meaningful are the subject of the new book Reclaiming Accountability by Heidi Kitrosser (University of Chicago Press, 2015).

The author introduces the term “substantive accountability,” which she contrasts with mere “formal accountability.” While formal accountability includes such things as the right to vote, substantive accountability requires that people must “have multiple opportunities to discover information relevant to their votes….”

This may seem obvious, but the trappings of formal accountability are often unsupported by the information that is needed to provide the substance of accountability, especially in matters of national security.

Kitrosser, a professor of law at the University of Minnesota Law School, shows that the principles of substantive accountability are deeply rooted in the text, structure and history of the Constitution. She uses those principles to provide a framework for evaluating contemporary assertions of presidential power over information, including executive privilege, state secrets, secret law, and prosecutions of unauthorized disclosures.

It cannot be the case, for example, that unauthorized disclosures of classification information are categorically prohibited by law and also that the President has discretion to classify information as he sees fit. If that were so, she explains, then the President would have unbounded authority to criminalize disclosure of information at will, and the classification system would have swallowed the First Amendment. As she writes: “The First Amendment’s promise would be empty indeed if its protections did not extend to information that the president wishes to keep secret.”

Kitrosser reviews the relevant case law to find openings and lines of argument that could be used to bolster the case for substantive accountability. She notes that Supreme Court rulings over the years “contain the seeds of an affirmative case for strongly protecting classified speakers.” In a 1940 ruling in Thornhill v. Alabama, for example, the Court declared that “The freedom of speech and of the press guaranteed by the Constitution embraces at the least the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all matters of public concern without previous restraint or fear of subsequent punishment.”

There is, of course, an opposing school of thought which posits a largely unconstrained presidential authority over government information. Moreover, this presidentialist view has been on “an upward historical trajectory” in recent decades. Leak investigations and prosecutions have risen markedly, and so have assertions of the state secrets privilege. Secret law blossomed after 9/11. The very term “executive privilege” is a modern formulation that only dates back to 1958 (as noted by Mark Rozell).

One of the deeply satisfying features of Kitrosser’s book (which is a work of scholarship, not a polemic) is her scrupulous and nuanced presentation of the presidential supremacist perspective. Her purpose is not to ridicule its weakest arguments, but to engage its strongest ones. To that end, she traces its origins and development, and its various shades of interpretation. She goes on to explain where and how substantive accountability is incompatible with presidential supremacy, and she argues that the supremacist viewpoint misreads constitutional history and is internally inconsistent.

The book adds analytical rigor and insight to current debates over secrecy and accountability, which it ultimately aims to inspire and inform.

“We can seek to harness and support those aspects of American law, politics, and culture that advance substantive accountability,” she writes.

“Reclaiming accountability is no single act. From internal challenges or external leaks by civil servants, to journalistic inquiries and reports, to congressional oversight, to FOIA requests, accountability is claimed and reclaimed every day by countless actors in myriad ways.”