If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

On January 31st, the State Department issued its annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the New START Treaty, with a notable––yet unsurprising––conclusion:

“Based on the information available as of December 31, 2022, the United States cannot certify the Russian Federation to be in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty.”

This finding was not unexpected. In August 2022, in response to a US treaty notification expressing an intent to conduct an inspection, Russia invoked an infrequently used treaty clause “temporarily exempting” all of its facilities from inspection. At the time, Russia attempted to justify its actions by citing “incomplete” work regarding Covid-19 inspection protocols and perceived “unilateral advantages” created by US sanctions; however, the State Department’s report assesses that this is “false:”

“Contrary to Russia’s claim that Russian inspectors cannot travel to the United States to conduct inspections, Russian inspectors can in fact travel to the United States via commercial flights or authorized inspection airplanes. There are no impediments arising from U.S. sanctions that would prevent Russia’s full exercise of its inspection rights under the Treaty. The United States has been extremely clear with the Russian Federation on this point.”

Instead, the report suggests that the primary reason for suspending inspections “centered on Russian grievances regarding U.S. and other countries’ measures imposed on Russia in response to its unprovoked, full-scale invasion of Ukraine.”

Echoing the findings of the report, on February 1st, Cara Abercrombie, deputy assistant to the president and coordinator for defense policy and arms control for the White House National Security Council, stated in a briefing at the Arms Control Association that the United States had done everything in its power to remove pandemic- and sanctions-related limitations for Russian inspectors, and that “[t]here are absolutely no barriers, as far as we’re concerned, to facilitating Russian inspections.”

Nonetheless, Russia has still not rescinded its exemption and also indefinitely postponed a scheduled meeting of the Bilateral Consultative Commission in November. In a similar vein, this is believed to be tied to US support for Ukraine, as indicated by Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov who said that arms control “has been held hostage by the U.S. line of inflicting strategic defeat on Russia,” and that Russia was “ready for such a scenario” if New START expired without a replacement.

These two actions, according to the United States, constitute a state of “noncompliance” with specific clauses of New START. It is crucial to note, however, the distinction between findings of “noncompliance” (serious, yet informal assessments, often with a clear path to reestablishing compliance), “violation” (requiring a formal determination), and “material breach” (where a violation rises to the level of contravening the object or purpose of the treaty).

It is also important to note that the United States’ findings of Russian noncompliance are not related to the actual number of deployed Russian warheads and launchers. While the report notes that the lack of inspections means that “the United States has less confidence in the accuracy of Russia’s declarations,” the report is careful to note that “While this is a serious concern, it is not a determination of noncompliance.” The report also assesses that “Russia was likely under the New START warhead limit at the end of 2022” and that Russia’s noncompliance does not threaten the national security interests of the United States.

The high stakes of failure: worst-case force projections after New START’s expiry

Both the US and Russia have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither country will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. Without a deal after 2026, that assumption immediately disappears; both sides would likely default to mutual distrust amid fewer verifiable data points, and our discourse would be dominated by worst case thinking about how both countries’ arsenals would grow in the future.

For an example of this kind of thinking, look no further than the new Chair of the House Armed Services Committee, who argued in response to the State Department’s findings of Russian noncompliance that “The Joint Staff needs to assume Russia has or will be breaching New START caps.” As previously mentioned, the State Department report explicitly states that they have only found Russia to be noncompliant on facilitating inspections and BCC meetings, not on deployed warheads and launchers.

It is clear that the longer that these compliance issues persist, the more they will ultimately hinder US-Russia negotiations over a follow-on treaty, which is necessary in order to continue the bilateral strategic arms control regime beyond New START’s expiry in February 2026. As Amb. Steve Pifer, non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, noted during the ACA webinar, “We have three years until New START expires. That seems like a lot of time, but it’s not a long of time if you’re going to try to do something ambitious.”

To that end, both sides should be clear-eyed about the stakes, and more specifically, about what happens if they fail to secure a new deal limiting strategic offensive arms.

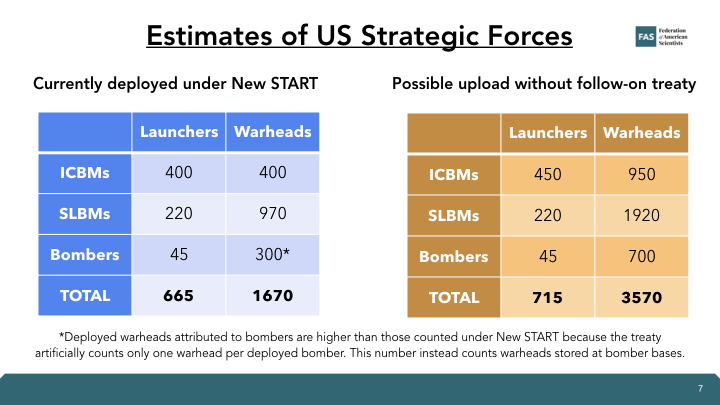

The United States has a significant upload capacity on its strategic nuclear forces, where it can bring extra warheads out of storage and add them to the deployed missiles and bombers. Although all 400 deployed US ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that is capable of carrying up to three warheads each. Moreover, the United States has an additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos which could be reloaded with missiles if necessary. With these potential additions in mind, the US ICBM force could potentially more than double from 400 to 950 warheads.

In the absence of treaty limitations, the United States could also upload each of its deployed Trident SLBMs with a full complement of eight warheads, rather than the current average of four to five. Factoring in the small numbers of submarines that are assumed to be out for maintenance at any given time, then the United States could approximately double the number of warheads deployed on its SLBMs, to roughly 1,920. The United States could potentially also reactivate the four launch tubes on each submarine that it deactivated to meet the New START limit, thus adding 56 missiles with 448 warheads to the fleet. However, this possibility is not reflected in the table because it is unlikely that the United States would choose to reconstitute the additional four launch tubes on each submarine given their imminent replacement with the next-generation Columbia-class.

Either of these actions would likely take months to complete, particularly given the complexities involved with uploading additional warheads on ICBMs. Moreover, ballistic missile submarines would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to be uploaded with additional warheads. However, deploying additional warheads to US bomber bases could be done very quickly, and the United States could potentially upload nearly 700 cruise missiles and bombs on its B-52 and B-2 bombers.

[Note: These numbers are projections based off of estimates; they are not predictions or endorsements. They also do not take into account how the number of available launchers and warheads will change when ongoing modernization programs are eventually completed, as this is unlikely to occur before New START’s expiry in 2026]

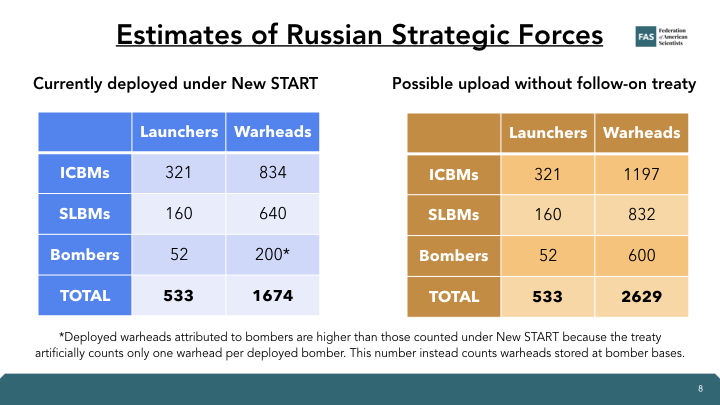

Russia also has a significant upload capacity, especially for its ICBMs. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities, in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase from approximately 834 warheads to roughly 1,197 warheads.

Warheads on submarine-launched ballistic missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without these limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased from an estimated 640 to approximately 832 (also with a small number of SSBNs assumed to be out for maintenance). As in the US case, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons. The number is highly uncertain but assuming approximately 50 bombers are operational, the number of warheads could potentially be increased to nearly 600.

Slide showing estimates of Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

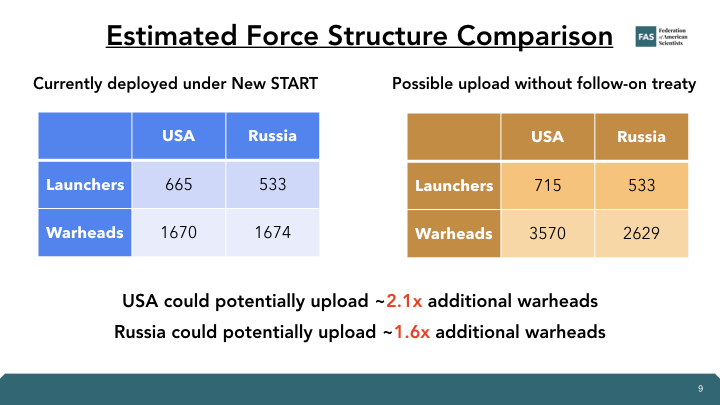

Combined, if both countries uploaded their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals would approximately double in size. The United States would have more deployable strategic warheads but Russia would still have a larger total arsenal of operational nuclear weapons, given its sizable stockpile of nonstrategic nuclear warheads which are not treaty-accountable.

Slide showing comparison estimates of US and Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

Moreover, there are expected consequences beyond the offensive strategic nuclear forces that New START regulates. If the verification regime and data exchanges elapse, both countries are likely to enhance their intelligence capabilities to make up for the uncertainty regarding the other side’s nuclear forces. Both countries are also likely to invest more into what they perceive will increase their overall military capabilities, such as conventional missile forces, nonstrategic nuclear forces, and missile defense.

These moves could trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, some of whom might also decide to increase their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. In particular, it is becoming increasingly clear that China appears to no longer be satisfied with just a couple hundred nuclear weapons to ensure its security, and in a shift from longstanding doctrine, may now be looking to size its own nuclear force closer to the size of the US and Russian deployed nuclear forces.

Some US former defense officials have suggested that the United States needs to increase its deployed nuclear force to compensate for the increased nuclear arsenal that China is already building and an alleged increase in Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons––either by negotiating a higher treaty limit with Russia or withdrawing from the New START treaty.

But doing so would not solve the problem and could put the United States on a path where it would in fact face even greater numbers of Russian and Chinese nuclear weapons in the future. A higher treaty warhead limit would obviously increase – not reduce – the number of Russian warheads aimed at the United States; and pulling out of New START would likely cause Russia to deploy even more weapons. Moreover, a significant increase in the size of US and Russian deployed nuclear forces could cause China to increase its arsenal even further. Such developments could subsequently have ripple effects for India, Pakistan, and elsewhere – developments that would undermine, rather than improve, US and international security.

Uploading more warheads is not necessary to maintain deterrence

It is important to note that even if such worst-case scenarios were to occur, in the past the Department of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence have assessed that even a significant Russian increase of deployed nuclear warheads would not have a deleterious effect on US deterrence capabilities. A 2012 joint study assessed:

“[E]ven if significantly above the New START Treaty limits, [Russia’s deployment of additional nuclear warheads] would have little to no effect on the U.S. assured second-strike capabilities that underwrite our strategic deterrence posture. The Russian Federation, therefore, would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.”

Although the political situation has dramatically changed over the past decade since the study was published, this particular deterrence dynamic has not. The United States’ second-strike capabilities remain as secure today––even among Russia’s noncompliance and China’s nuclear buildup––as they did a decade ago. As a result, it seems clear that although uploading additional warheads onto US systems may seem like a politically strong response, it would not offer the United States any additional advantage that it does not already possess, and would likely trigger developments that would not be in its national security interest.

—

Background Information:

- “The Long View: Strategic Arms Control After the New START Treaty,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November 2022.

- “United States nuclear weapons, 2023,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 2023.

- “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2022.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.