British Defense Review Ends Nuclear Reductions Era

[Article updated May 11, 2021] The United Kingdom announced yesterday that it has decided to abandon a previous plan to reduce it nuclear weapons stockpile to 180 by the mid-2020s and instead “move to an overall nuclear weapon stockpile of no more than 260 warheads.”

The decision makes Britain the first Western nuclear-armed state to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile since the end of the end of the Cold War. In terms of numbers, it takes Britain back to a stockpile size it had in the early-2000s. The change is part of “a shift to a more robust position on security and deterrence.”

The Review also decided that Britain will “no longer give public figures for our operational stockpile, deployed warhead or deployed missile numbers.” This counterproductive decision follows the earlier decision of the Trump administration to keep the nuclear stockpile number secret. By embracing nuclear secrecy, Britain effectively abdicates its ability to criticize Chinese or Russian secrecy about their nuclear arsenals.

The decision to increase the size of the future stockpile – and potentially deploy more warheads on British submarines – is but the latest example of nuclear-armed states invigorating a nuclear arms race and reversing progress toward reducing the world’s nuclear arsenals.

The British Nuclear Weapons Stockpile

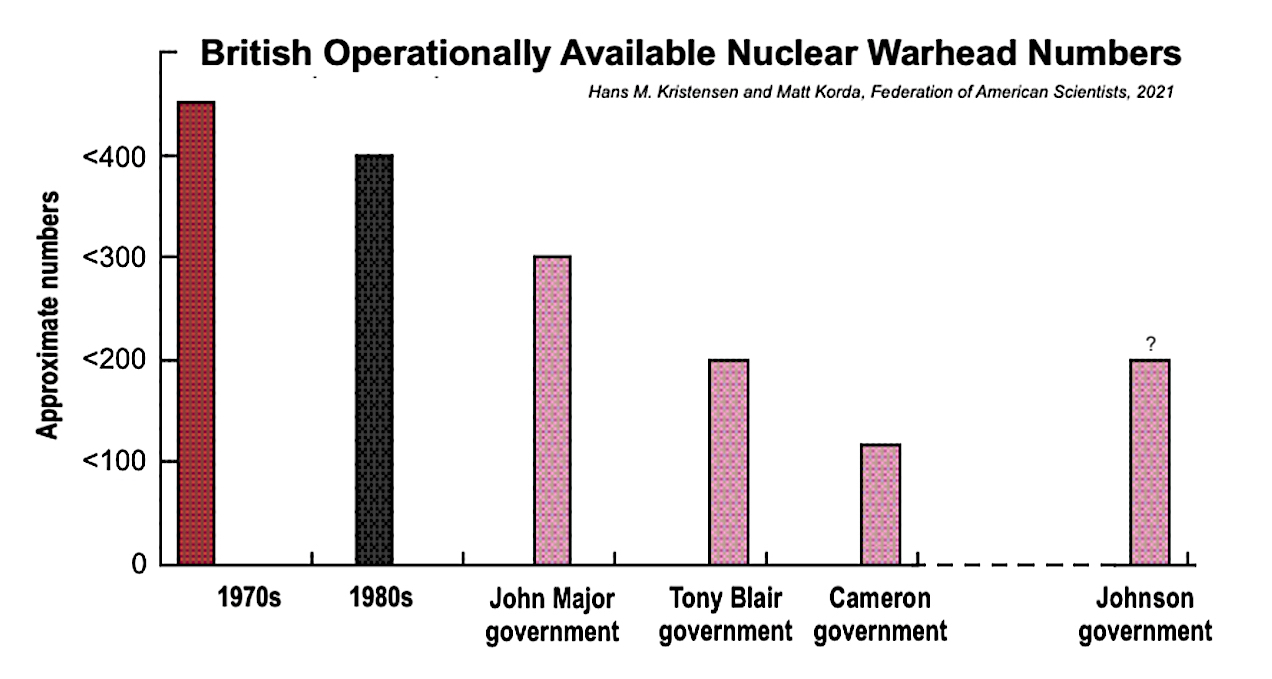

The British government has never declassified the history of its nuclear weapons stockpile. Instead, it has occasionally published documents or made statements that gave overall numbers or percentages. The government announced in 2010 that it would have “no more than 225” warheads and later that the limit would be reduced to 180 by the mid-2020s. It is unknown how far the reduction of those approximately 45 warheads has progressed. If spread out evenly over the 15 years, the number might have reached just below 200 by now. But it is highly uncertain so illustrating the British stockpile comes with considerable uncertainty (In this article we conclude that the stockpile did not drop below the 225 ceiling set in 2010 and remains at that level today). The following graph is illustrative and based on previous statements and documents.

Note: This graph has been updated. The history of the United Kingdom nuclear weapons stockpile is still classified, so the graph is provided for illustrative purposes. Click on graph to view full size.

The timeline for the new stockpile limit of 260 warheads is not entirely clear but appears to be during the 2020s. The Review reflects an assessment out to 2030 but “establishes the Government’s overarching national security and international policy objectives, with priority actions, to 2025.”

The wording of the new warhead level is vague. The Review sets the number at “no more than 260 warheads.” The British government has subsequently explained the “260 figure is a ceiling, not a target.” Political damage control is probably part of that statement, but the number could potentially be somewhat lower – or it could be about 260.

Not all of the stockpiled warheads are deployed. The majority is called “operationally available,” which means they’re onboard three of the four SSBNs or can be loaded fairly quickly. The rest are a reserve as spares or undergoing maintenance. Since 2015, the number of “operationally available warheads” has been approximately 120, of which the number deployed on the single SSBN at sea has been reduced to 40.

Unlikely previous defense reviews, the Integrated Review does not include any information about how many of the stockpiled warheads will be operationally available, loaded onboard deployed submarines, or how many submarines will be at sea at any given time. This is a step back for British nuclear transparency. Based on statements from previous governments, however, the number of operationally available warheads under the Johnson posture might end up being similar to what it was during the Blair government: perhaps close to 160 warheads.

The stockpiled warheads that are not “operationally available” are likely stored at Coulport Ammunition Depot nearly the Faslane Submarine Base in Scotland (see image below). Warheads undergoing maintenance or upgrade to the Mk4A aeroshell are probably stored at AWE Burghfield or AWE Aldermaston west of London. Retired warheads are shipped to Burghfield for dismantlement and disposition.

In 2013, the UK government described the process: warheads “yet to be disassembled” are stored at Coulport or as “work in progress” at Burghfield. “A number of warheads identified in the [stockpile reduction] programme for reduction have been modified to render them unusable whilst others identified as no longer being required for service are currently stored and have not yet been disabled or modified.”

Those retired warheads that have not been “rendered unusable” are most likely the source for increasing the stockpile now. Britain doesn’t have the capacity to quickly produce 50-60 new warheads so it simply brings warheads out of retirement. Reconstituting those warheads can probably be done in a few years.

Nuclear Strategy and Targeting

The extent to which the increased stockpile will affect targeting requirement for Britain’s ballistic missile submarines remains to be seen. But the Review states that the stockpile increase comes in response to “the evolving security environment, including the developing range of technological and doctrinal threats.”

Russia is singled out as “the most acute direct threat to the UK” but the Review also contains what appears to be a subtle but clear nuclear threat against Iran (even though it doesn’t have nuclear weapons). After assuring the “UK will not use, or threaten to use, nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 1968 (NPT),” the Review adds: “This assurance does not apply to any state in material breach of those non-proliferation obligations.”

The difference between the stockpile limit number and operationally deployed warheads in previous government statements indicates that an increased stockpile limit of 260 warheads most likely will also result in an increase in the number of operationally available warheads and possibly the number of warheads onboard the submarines. An increased number of deployed warheads means an increased number of aimpoints. The United States shares strategic war plan details with the United Kingdom in support of NATO.

In 1998, there were fewer than 200 operationally available warheads. In 2007, that category was reduced to 160 warheads, of which 48 were onboard the submarine at sea. In 2015, that category was reduced to 120 warheads, of which 40 were onboard the single submarine on patrol. The Review states that “at least one [submarine] will always be on a Continuous At Sea Deterrent patrol” (CASD) “at several days’ notice to fire…to guarantee that the UK’s nuclear deterrent remains credible and effective against the full range of state nuclear threats from any direction.”

Perhaps the increased stockpile is intended to facilitate increased targeting of Russia. Perhaps it broadens targeting to other potential adversaries (China, Iran). Perhaps it increases targeting of non-nuclear strategic threats. Perhaps it’s a combination.

The US Connection

The British announcement to increase its stockpile is particularly sensitive now because it preempts the new Biden administration’s upcoming nuclear posture review. Given the nuclear developments in Russia and China, it already seemed unlikely that Biden would reduce the US stockpile further than previously planned. But nuclear proponents in the United States must be rejoicing; the British announcement makes it politically awkward for the Biden administration to reduce.

Britain does not own its own ballistic missiles but leases U.S. Trident II D5 missiles. British SSBNs conduct test flights off Florida after being serviced at Port Canaveral.

The current British warhead, known as the Holbrook, is thought to closely resemble the U.S. W76-0. The British warhead is so similar that it is part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s “W76 Needs” maintenance schedule. The Holbrook warhead is currently being backfitted with the new Mk4A aeroshell with enhanced targeting capability. Increasing the stockpile presumably will require buying additional Mk4A aeroshells from the United States.

But the Holbrook is getting old, so British officials have been busy lobbying the U.S. government about moving forward with its proposed new W93/Mk7 warhead, which will also form part of Britain’s next warhead design. Although a U.S. defense official has described the two programs as “two independent, development systems,” a British defense official subsequently explained that although they are “not exactly the same warhead…there is a very close connection in design terms and production terms.” Like the Holbrook, which is contained in the U.S. produced Mk4A reentry body, the new British warhead will be contained in the U.S. produced Mk7 reentry body.

It sounds like we can look forward to another 30 years of discussion about how independent the British deterrent is.

The NPT Context

The decision to increase the nuclear weapons stockpile strongly conflicts with the role Britain has played in nuclear disarmament efforts and the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) regime over the past three decades. All those efforts have been about reducing arsenals. The Review breaks with that legacy.

Nonetheless, the Review reiterates long-held British support for the NPT: “We remain committed to the long-term goal of a world without nuclear weapons. We continue to work for the preservation and strengthening of effective arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation measures, taking into account the prevailing security environment. We are strongly committed to full implementation of the NPT in all its aspects, including nuclear disarmament…” In fact, the commitment to NPT as an instrument for disarmament is so singular that the Review states that “there is no credible alternative route to nuclear disarmament.”

Although NPT’s Article VI does not explicitly prohibit Britain from increasing its nuclear stockpile, it obligates Britain to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control.”

Increasing the stockpile in response to Russia and other threats certainly seems to conflict with the goal of ending the nuclear arms race. Instead, it seems to embrace a race.

Moreover, British governments have explicitly linked stockpile reductions to its “obligations under Article six.” In 2015, for example, the U.K. delegation to the NPT Review Conference stated that the “United Kingdom remains firmly committed to step-by-step disarmament, and our obligations under Article Six. We announced in January that we have reduced the number of warheads on each of our deployed ballistic missile submarines from 48 to 40, and the number of operational missiles on each of those submarines to no more than eight.”

The decision to increase the stockpile clearly contradicts those assurances and obligations. That, and the decision to reduce nuclear transparency, will make it less credible for British diplomats to criticize Russia and China for increasing their stockpiles and hiding behind nuclear secrecy. It might also weaken Britain’s ability to appeal to Iran not to develop nuclear weapons.

In conclusion: Johnson has pulled a Trumpie that will boost Britains nuclear profile but do little to reduce nuclear dangers.

Additional information: United Kingdom Nuclear Weapons, 2021

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.