NNSA Nuclear Plan Shows More Weapons, Increasing Costs, Less Transparency

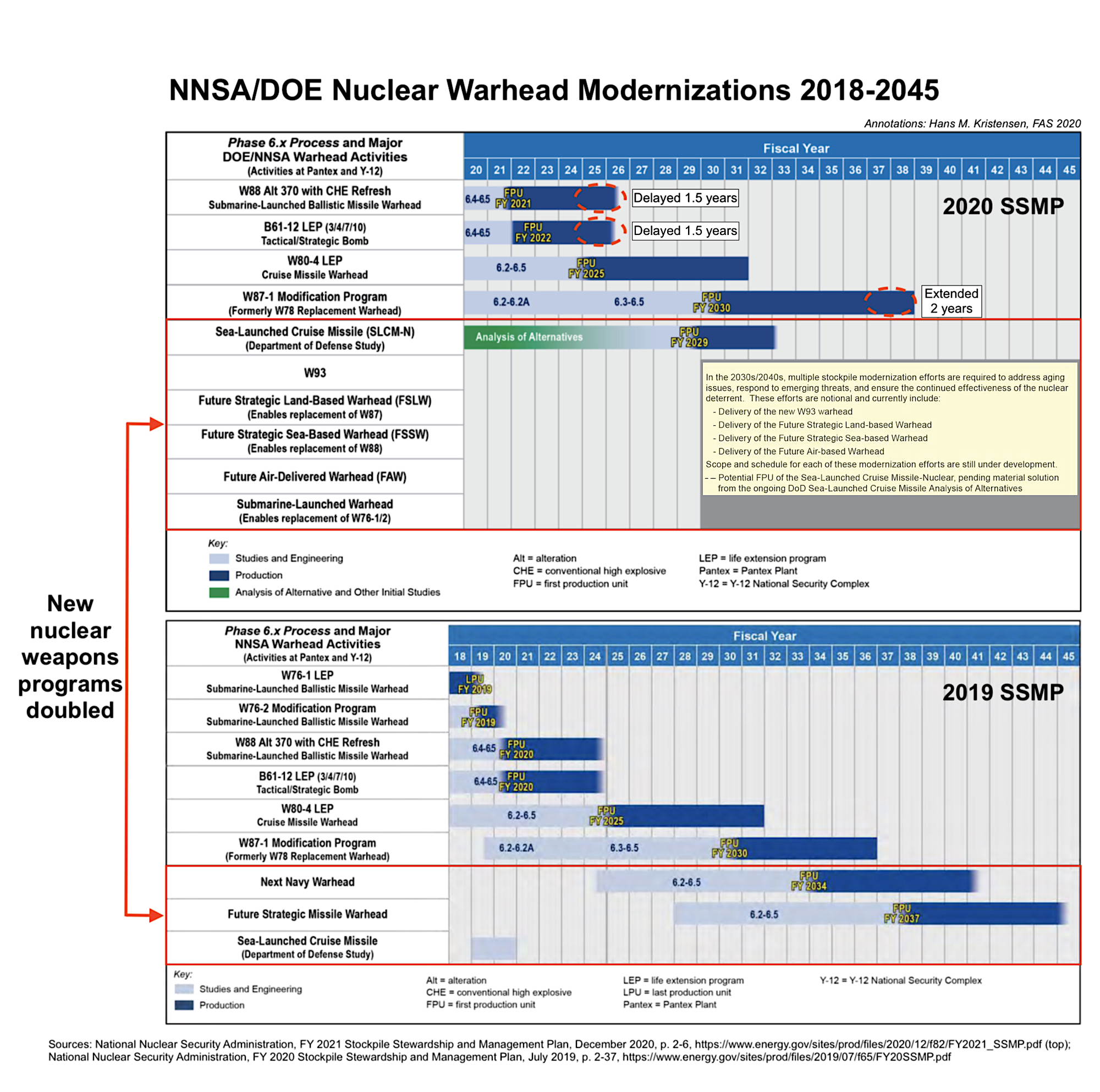

The National Nuclear Security Administration’s (NNSA’s) new Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) doubles the number of new nuclear warhead programs compared with the previous plan from 2019. The plan shows nuclear weapons advocates taking full advantage of the Trump administration to boost nuclear weapon programs.

The new plan also shows significantly increasing nuclear weapons costs projected for the next two decades. These additional costs reflect the steadily growing ambitions of the nuclear modernization programs in response to the embrace of the Great Power Competition strategy articulated in the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy and Nuclear Posture Review.

Moreover, the 2020 SSMP significantly reduces the information available to the public about NNSA’s nuclear weapons activities by cutting by nearly half the size of the public version of the plan and omitting information that used to be included in previous SSMP reports.

More Nuclear Weapons

The new NNSA report doubles the number of new nuclear weapons modernization programs compared with the previous SSMP plan from 2019. This includes the recently reported W93 navy warhead, a new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile, and two future warheads that appear to be derived from what was previously called the Reliable Replacement Warheads. “In addition to these warheads,” the SSMP states, “a replacement air-delivered warhead and submarine-launched warhead (for the W76-1/2) will be needed in the 2040s.” Some of these future warheads were indicated in the DOD’s Nuclear Matters Handbook, which was published earlier this year.

The 2020 NNSA plan lists twice as many new nuclear weapons as the previous plan from 2019. Click on figure to view full size.

The navy gets four of the six new warheads. The first of these is the new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) advocated by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. Congress has funded a study for this weapon and NNSA plans to begin production in 2029, but it remains to be seen if the new Biden administration will continue it. If so, the missile might be equipped with a modified W80 cruise missile warhead (perhaps a W80-5 modification) for deployment on Virginia-class attack submarines.

The second navy warhead is the W93, which was announced by NNSA in February. Importantly, the W93 is not listed as a replacement for the W76 or W88 warheads, which are listed to be replaced by two other warheads, but as a supplement. This fits the description in the navy’s talking points on the new warhead.

The third navy warhead is the Submarine Launched Warhead (SLW) slated to replace the W76-1 and W76-2. This indicates that the SLW might have flexible yield settings to cover both the medium/high-yield mission of the W76-1 and the low-yield mission of the W76-2, or that they will produce two yield versions of it, or that the W76-2 mission will simply fall away.

The fourth navy warhead is the Future Strategic Sea-Based Warhead (FSSW), which is listed as a replacement of the W88, the highest-yield ballistic missile warhead, which is currently being life-extended under the Alt 370 program.

Four of the six new nuclear weapon programs listed in the new NNSA plan are for the US Navy. (Image: US Navy)

The ICBM force gets one new warhead – known as Future Strategic Land-Based Warhead (FSLW) – to replace the W87. It is unclear from the SSMP if the if the new warhead is intended to replace both versions of the W87 or only the W87-0. The W87-1 will still have a lot of life left in it in the 2040s, so it probably initially means replacing the W87-0. If it replaces both, then the ICBM force would go to a single warhead instead of the two currently arming it.

The bombers get a new weapon, known as the Future Air-Delivered Warhead (FAW). The weapon was previously known as the B61-13. The weapon is a follow-on to the B61-12, which will begin rolling off the projection line in late-2021.

The new warhead focus appears to continue the trend to somewhat break with the post-Cold War approach by moving away from simple life-extension of existing warheads to instead produce weapons based on significantly modified or even new designs with new military capabilities. The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review removed restrictions in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review on new warheads with new military capabilities. Instead, the 2020 SSMP more overtly justifies new requirement to be able to quickly design and produce new nuclear weapons with “enhanced military capabilities” and “responding to increased threats” in a Great Power Competition context.

The W93, for example, will “address the changing strategic environment” and “improve…flexibility to address future threats,” according to the SSMP. And the new future ballistic missile warheads will “support threats anticipated in 2030 and beyond.” Likewise, part of the justification to increase warhead pit production capacity to at least 80 pits per year is “Renewed competition among global powers that may lead to changes in deterrent requirements.”

Growing Costs

Underpinning all of these nuclear weapons maintenance and modernization plans is a sprawling nuclear weapons complex that is scheduled to increase significantly with new bomb-making factories and support facilities. This includes boosting the warhead pit production capacity at the Los Alamos National Laboratory and adding a second pit production factory at the Savannah River Site to produce no fewer than 80 new pits per year by 2030. The new pits will feed the W87-1 production and the new future warheads.

The NNSA budget began to increase during the Obama administration and the Trump administration has increased it significantly since and is proposing an additional increase of 19 percent in the FY2021 budget.

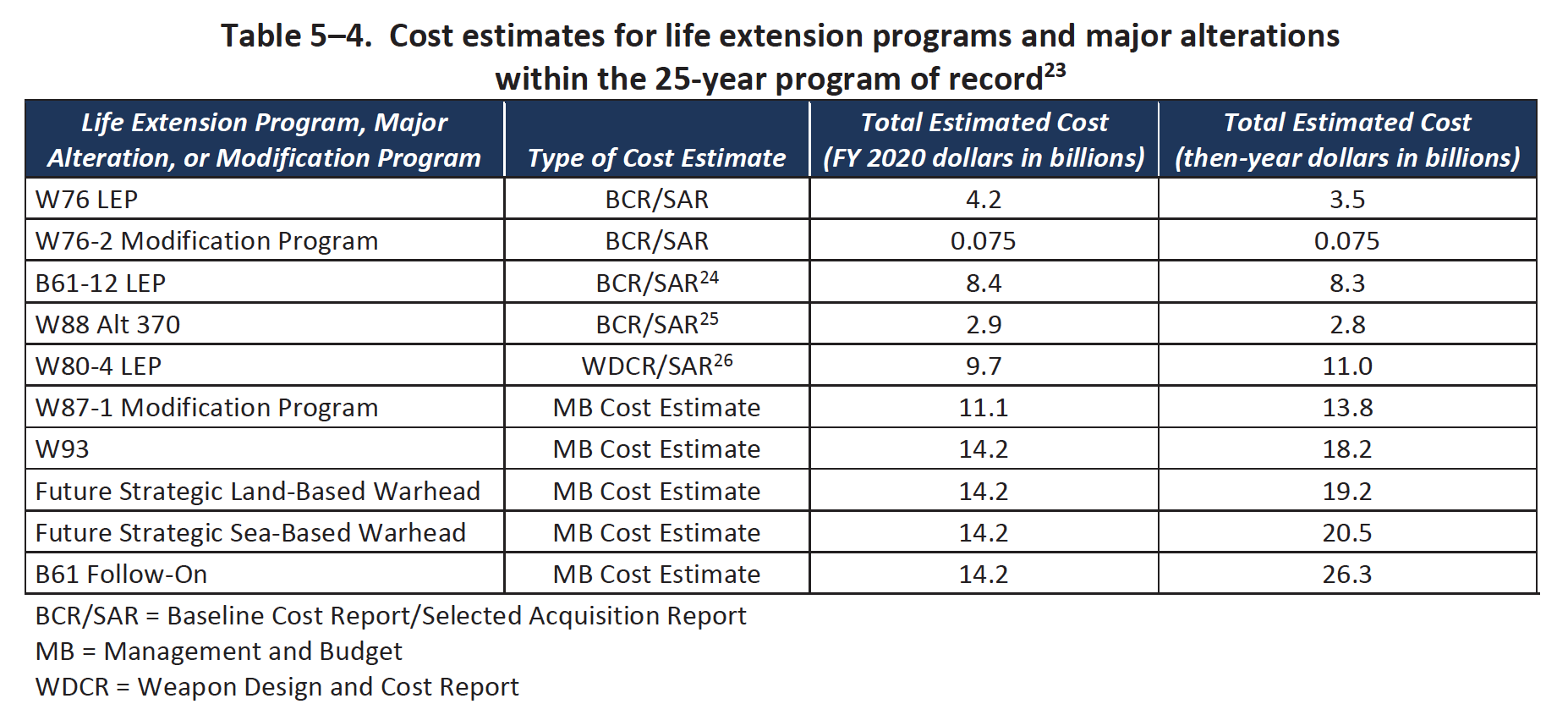

The trend is that warhead modernization programs are becoming more and more expensive. The current LEPs are twice as expensive as the W76-1 LEP, and the new warheads in the SSMP are projected to cost three-and-a-half times that amount (see figure below). Once the programs get underway, the early estimates will likely prove to be too low. The reason for this dramatic increase is that the nuclear laboratories and the military add more and more bells and whistles and new components to more advanced warhead designs that increase complexity and cost.

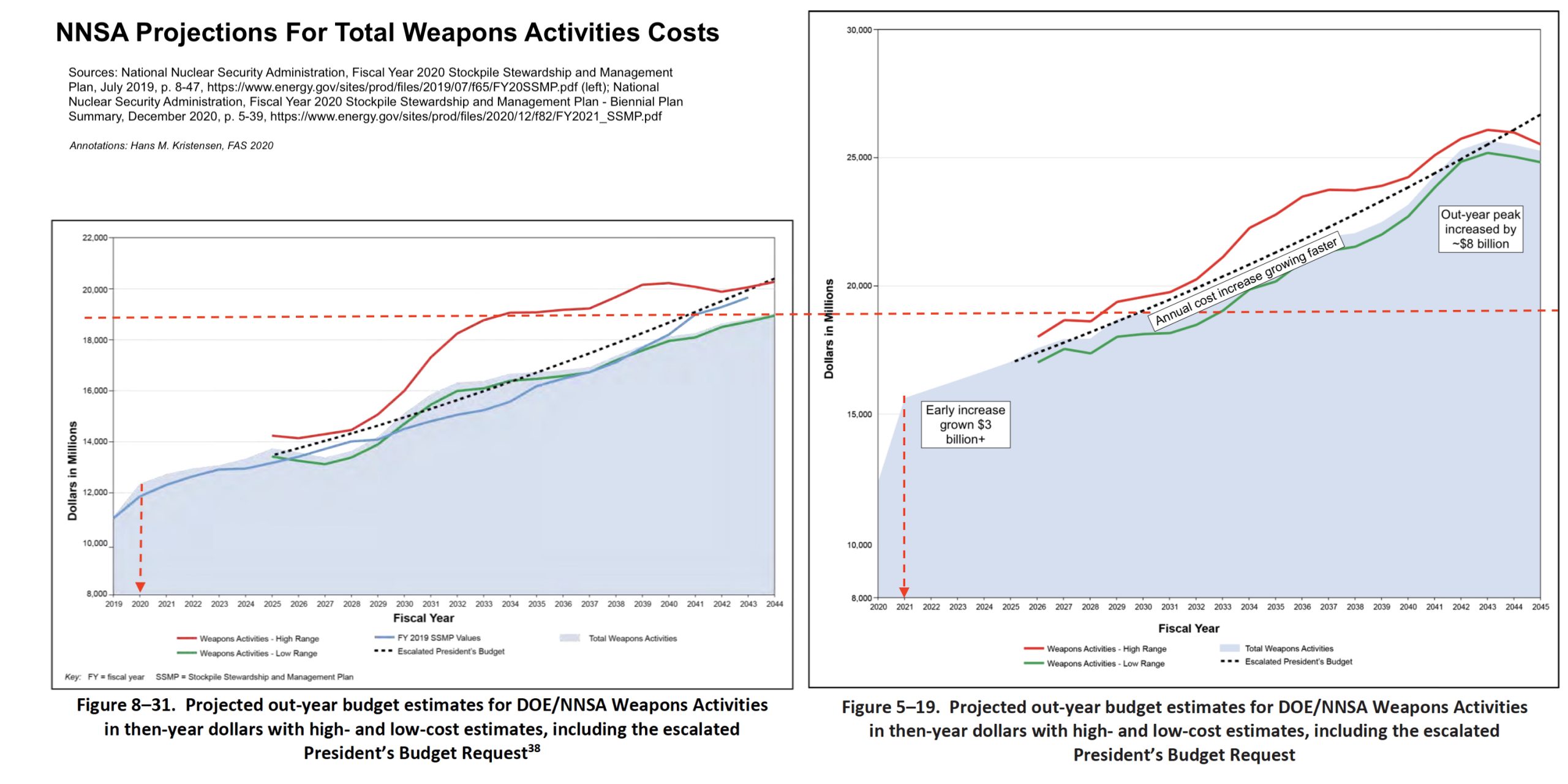

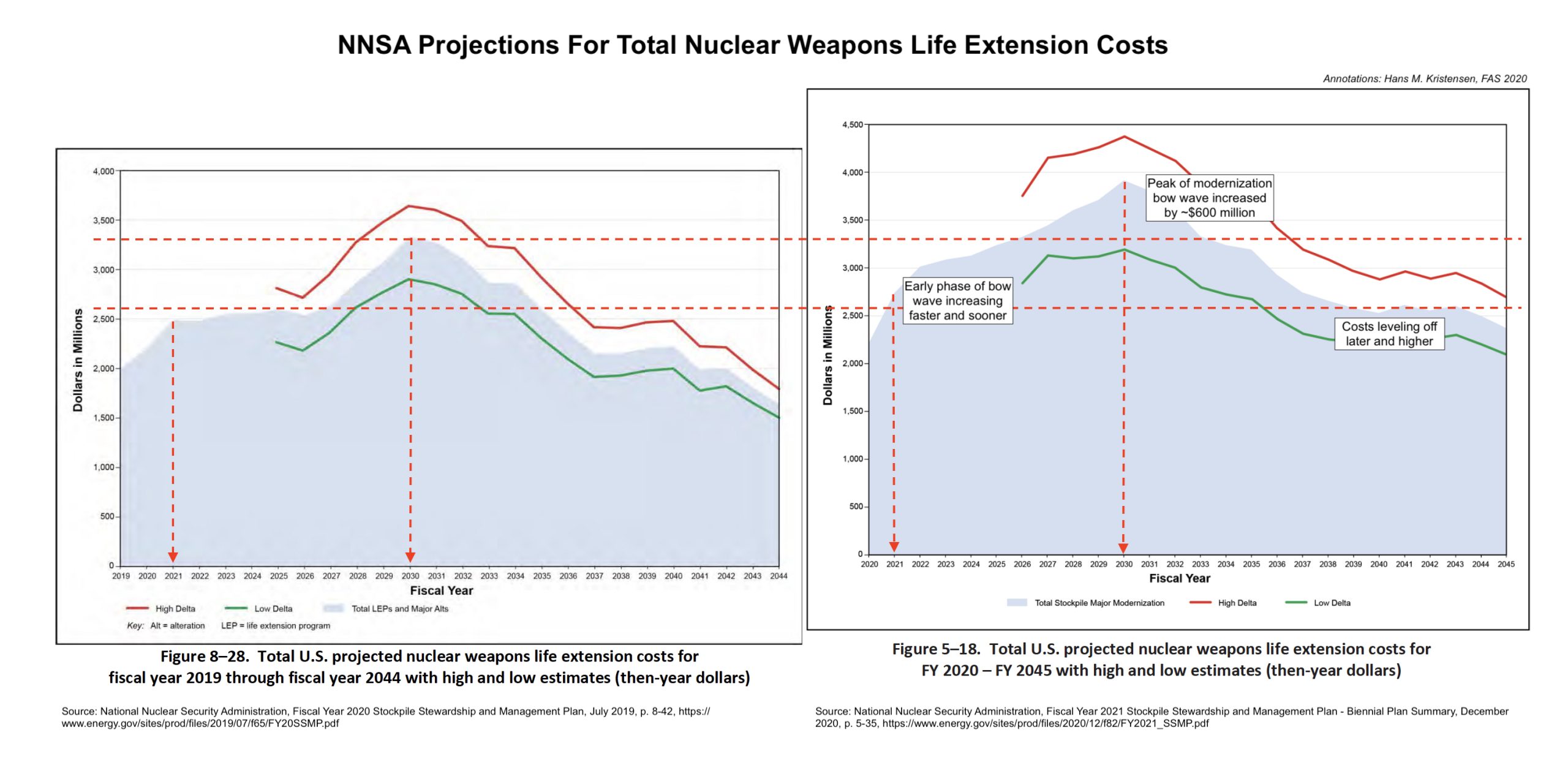

The 2020 SSMP shows increased costs for nuclear weapons life-extensions compared with the previous SSMP (in then-year dollars). A rough comparison of the two reports shows that the cost bow wave peak in 2030 is about $600 million higher than projected last year, the early phase of the bow wave increases faster and sooner, and the future costs are leveling off later and higher than projected in the 2019 report (see figure below).

NNSA cost projection for warhead life-extension programs is increasing. Click on figure to view full size.

Similarly, the cost projection for total Weapons Activities in the 2020 SSMP shows a significant increase across the board. The peak projected for the early-2040s has increased by approximately $8 billion, the increase in the early 2020s has increased by more than $3 billion, and the annual cost increase is growing faster than projected in the 2019 SSMP.

Reducing Nuclear Transparency

The 2020 SSMP significantly reduces nuclear weapons information made available to the public. Contrary to the 2019 SSMP, the new report is not a full report but a plan summary. It is only about half the size of 2019 SSMP (192 pages versus 364). Important information that was previously made available is not included at all or significantly reduced.

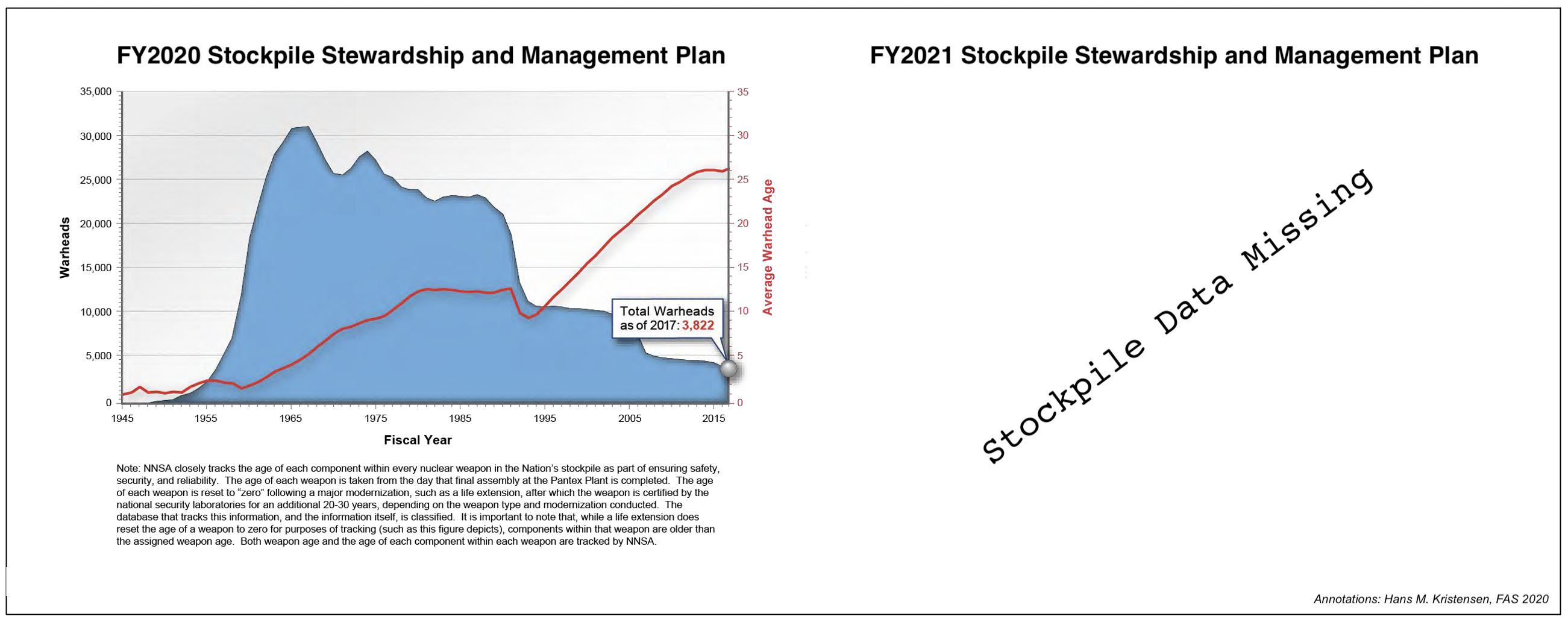

One example of omitted information is the United States nuclear weapons stockpile, which is completely missing from the new report. The 2019 SSMP included a chart that showed the history and size of the stockpile and the average age of stockpiled warheads. The omission of the stockpile data coincides with the Trump administration’s refusal to declassify the stockpile data for the past two years.

The new NNSA plan no longer includes nuclear weapons stockpile data. Click on image to view full size.

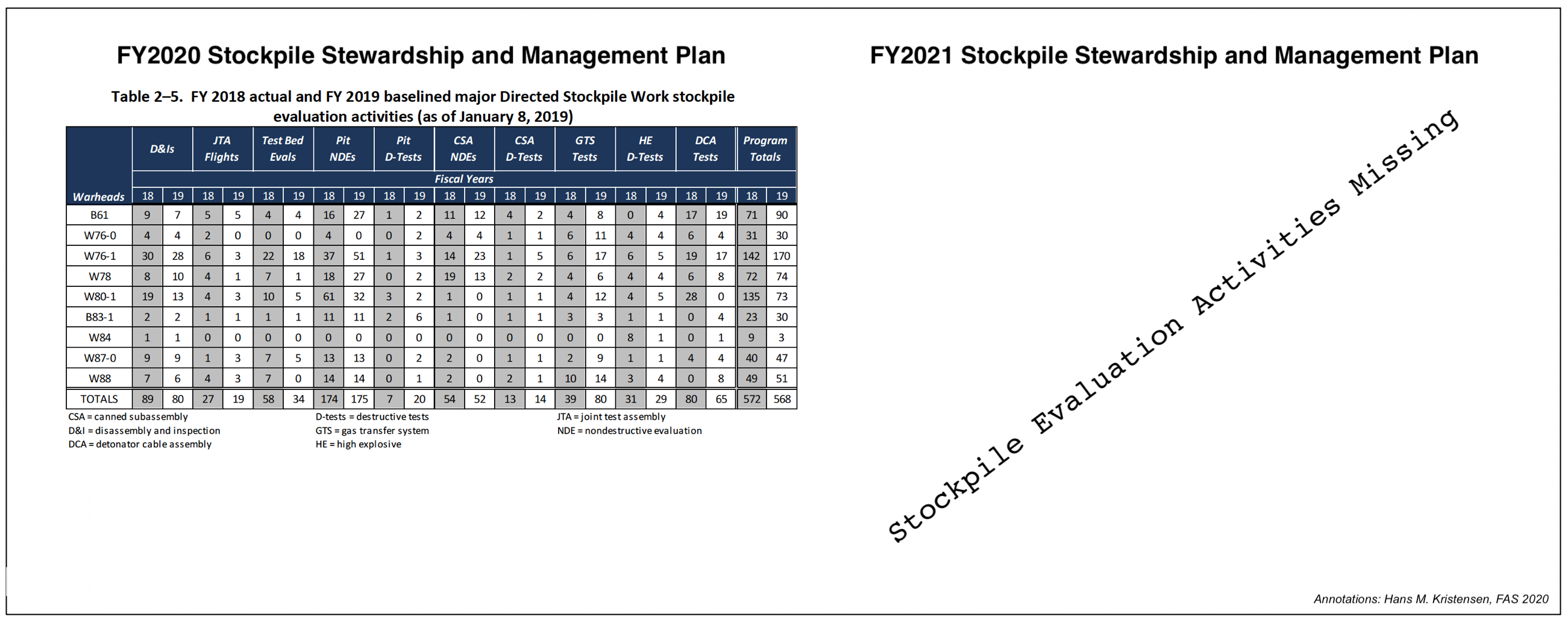

Another example of omitted information is data about warhead sustainment activities. The 2019 SSMP includes two charts that showed the number of such activities for each warhead as well as the total number of sustainment tests. Such information is not included in the 2020 version.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) deserves credit for publishing the 2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP). Other nuclear-armed states should follow the example to increase transparency of their nuclear weapons activities to avoid misunderstandings, reduce worst-case planning, and increase trust. That said, the new SSMP shows some concerning trends.

First, the plan shows a nuclear modernization program that goes well beyond modernizing the existing nuclear deterrent to increasing the types – and in the future potentially the number – of nuclear weapons and enhancing their military capabilities as part of growing competition with other nuclear-armed states.

Second, the plan shows nuclear weapon modernization programs where costs are not only increasing but doing so faster. The plan shows that NNSA anticipates that significant additional funding is required in the years ahead. The increased costs to the taxpayers come at a time when the US economy is buckling under the strain of the COVID-19 pandemic. And the nuclear modernization costs compete with funding for other high-priority programs.

Third, the NNSA plan continues a worrisome trend of increased secrecy by significantly reducing the type and amount of information previously made available in SSMP reports about nuclear modernization programs and activities. This reduces the public’s ability to monitor government programs, ask questions, and make informed decisions.

The 2020 SSMP is a timely reminder that the incoming Biden administration must trim and adjust the nuclear weapons modernization program to make it more affordable, sustainable, and justifiable. It must do so in a way that safeguards US national security and that of its allies while reducing international tension and military competition. Some adjustments can be unilateral, others bilateral, while some will require broader international cooperation.

Background information:

2020 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan – Biennial Plan Summary

2019 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country.

Nearly one year after the Pentagon certified the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program to continue after it incurred critical cost and schedule overruns, the new nuclear missile could once again be in trouble.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end”

Without information, without factual information, you can’t act. You can’t relate to the world you live in. And so it’s super important for us to be able to monitor what’s happening around the world, analyze the material, and translate it into something that different audiences can understand.