Despite Rhetoric, US Stockpile Continues to Decline

Click on image to view full size. Full document here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

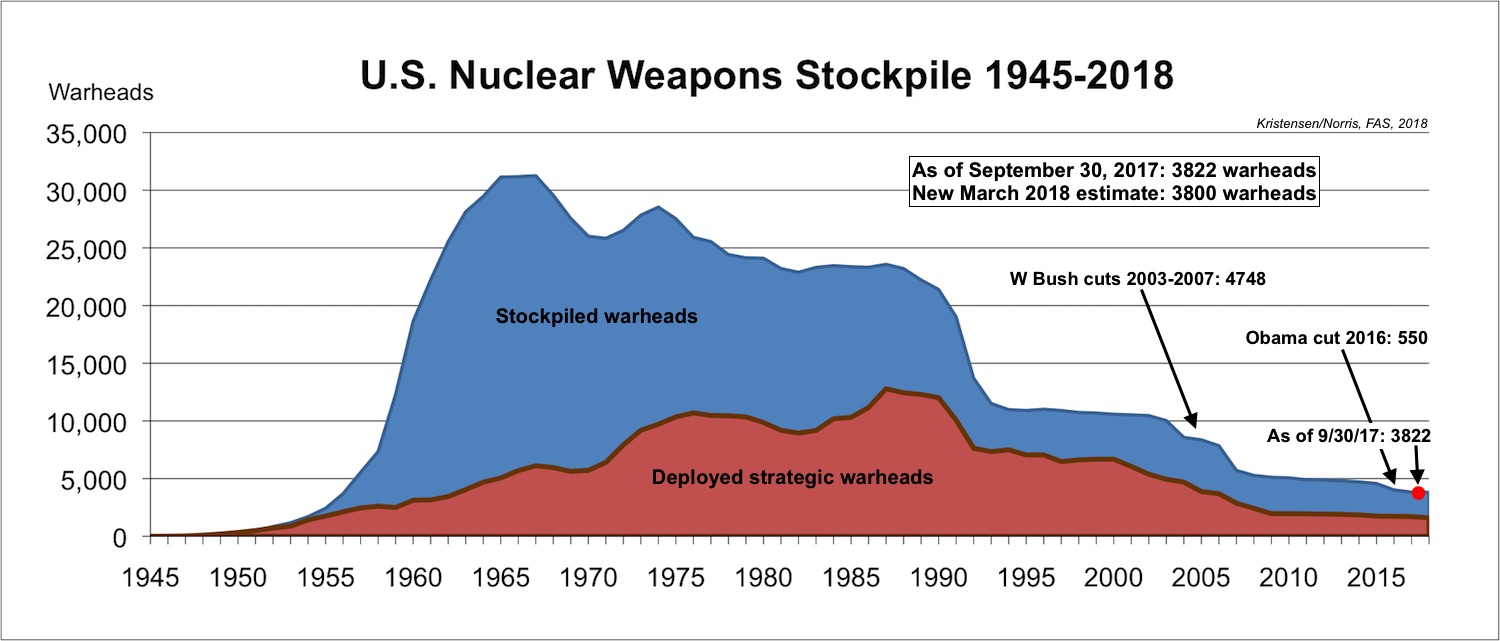

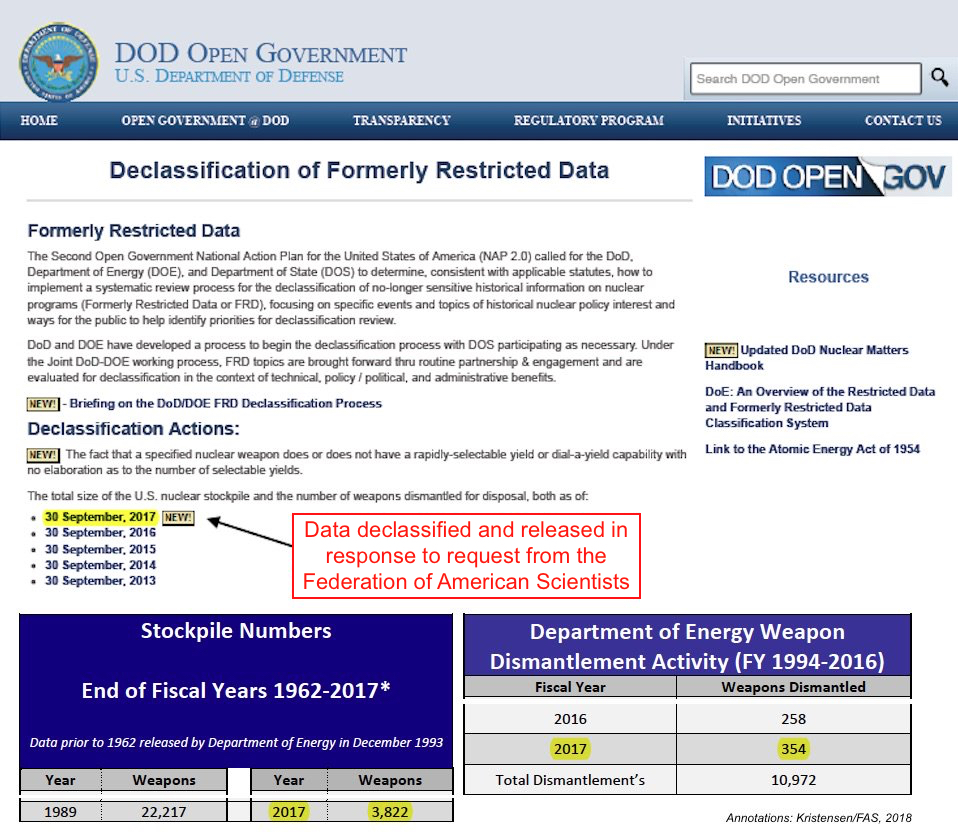

The US nuclear weapons stockpile dropped to 3,822 warheads by September 2017 – down nearly 200 warheads from the last year of the Obama administration, according to new information released by the Department of Defense in response to a request from the Federation of American Scientists (see here for full document).

Since September 2017, the number has likely declined a little further to about 3,800 warheads as of March 2018. This is the lowest number of stockpiled warheads since 1957 (see graph), although the nuclear weapons and the conventional capabilities that make up today’s arsenal are vastly more capable than back then.

The new data also shows that the United States dismantled 354 warheads during the period October 2016 to September 2017 – the highest number of warheads dismantled in a single year since 2009. Since 1994, the United States has dismantled nearly 11,000 nuclear warheads.

The continued reductions are not the result of new arms control agreements or a change in defense planning, but reflects a longer trend of the Pentagon working to reduce excess numbers of warheads while upgrading the remaining weapons. This trend is as old as the Post Cold war era.

The majority of the warheads retired during the Trump administration’s first year probably included W76-0 warheads no longer needed as feedstock for the Navy’s W76-1 life-extension program.

The reduction has happened despite tensions with Russia, bombastic nuclear statements by President Donald Trump, and Nuclear Posture Review assertions about return of Great Power competition and need for new nuclear weapons.

The apparent disconnect between rhetoric and the stockpile trend illustrates that nuclear deterrence and national security are less about the size of the arsenal than what it, and the overall defense posture, can do and how it is postured.

Although defense hawks home and abroad will likely seize upon the reduction and argue that it undermines deterrence and reassurance, the reality is that it does not; the remaining arsenal is more than sufficient to meet the requirements for national security and international obligations. On the contrary, it is a reminder that there still is considerable excess capacity in the current nuclear arsenal beyond what is needed.

President Trump recently said he expected to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin “in the not-too-distant future to discuss the arms race,” which Trump added “is getting out of control…” He is right. In such discussions he should urge Russia to follow the U.S. example and also disclose the size of its nuclear warhead stockpile, agree to extend the New START treaty for five years, work out a roadmap to resolve INF Treaty compliance issues, and develop new agreements to regulate nuclear and advanced conventional forces.

There is much work to be done.

Additional information:

Declassified stockpile numbers.

Recent FAS Nuclear Notebook on US nuclear forces (written before the new stockpile information became available).

For an overview of all nuclear-armed states, see our Status of World Nuclear Forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.