No, China Does Not Have 3,000 Nuclear Weapons

|

| A study from Georgetown University incorrectly suggests that China has 3,000 nuclear weapons.The estimate is off by an order of magnitude. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Only the Chinese government knows how many nuclear weapons China has. As in most other nuclear weapon states, the number is a closely held secret. Even so, it is possible to make best estimates of the approximate size that benefit the public debate.

A recent example of how not to make an estimate is the study recently published by the Asia Arms Control Project at Georgetown University. The study (China’s Underground Great Wall: Challenge for Nuclear Arms Control) suggests that China may have as many as 3,000 nuclear weapons.

Although we don’t know exactly how many nuclear weapons China has, we are pretty sure that it doesn’t have 3,000. In fact, the Georgetown University estimate appears to be off by an order of magnitude.

Fissile Material

The most fundamental problem with the 3,000-warhead estimate is that there is no evidence – at least in the public – that China has produced enough fissile material to build that many warheads. Not even close.

An arsenal of 3,000 two-stage thermonuclear warheads with yields of 300-500 kilotons would require 9-12 tons of weapon-grade plutonium and 45-75 tons of highly-enriched uranium (HEU).

Based on what is known about China’s inventory of fissile materials, how many nuclear weapons could it build?

According to the International Panel on Fissile Materials, China has produced an estimated 2 tons of plutonium for weapons. Some has been consumed in nuclear tests, leaving roughly 1.8 tons. The estimate is consistent with what the U.S. government has stated and theoretically enough for 450-600 warheads.

Total production of HEU is thought to have been approximately 20 tons. Some has been spent in nuclear tests and research reactor fuel, leaving a stockpile of some 16 tons. That’s theoretically enough for roughly 640-1,060 warheads.

Another critical material is Tritium, which is used in thermonuclear weapons. China probably only produces enough Tritium at its High-Flux Engineering Test Reactor (HFETR) in Jiajiang to maintain an arsenal of about 300 weapons.

The U.S. intelligence community concluded in 2009 that China likely has produced enough weapon-grade fissile material to meet its needs for the immediate future. In other words, no vast warhead expansion is in sight.

Nuclear Warheads

With this stockpile of fissile material on hand, how many nuclear weapons might China currently have?

First, it is important to keep in mind that nuclear weapon states do not convert all of their fissile material into nuclear weapons but use part of it for weapons and leave the rest as a reserve for future needs. Therefore, one cannot simply translate the amount of fissile material into weapons.

Second, nuclear warheads need nuclear-capable delivery vehicles, missiles and aircraft that can bring the warheads to their intended targets. Delivery vehicles can give a better idea of the size of a nuclear arsenal. Most of China’s ballistic missiles are conventional or dual-capable, but the Georgetown University study includes all missiles in its 3,000-warhead projection, including short-range DF-11 and DF-15 missiles and medium-range DF-21C missiles.

Taking those and other factors into account, our current estimate is that China has approximately 240 nuclear warheads for delivery by nearly 180 missiles and aircraft. Nearly 140 of the operational missiles are land-based. Less than 50 of those can reach the continental United States.

The 240-warhead estimate also includes warheads produced for China’s ballistic missile submarine force (which is not yet operational), weapons for bombers, and some weapons for spares.

Our estimate is consistent with the estimate made by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency in 2006: “China currently has more than 100 nuclear warheads.”

Modernization

With its ongoing modernization of its nuclear forces, which includes deployment of three new ICBMs, China will be placing a greater portion of its warheads on ICBMs. The portion of those that can strike the continental United States, according to the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, “probably will more than double…by 2025.” That doesn’t mean the total warhead stockpile will “more than double,” only the portion that is on ICBMs. Only time will tell to what extent that happens, but the U.S. projection for Chinese nuclear weapons has been wrong before.

Indeed, the DIA estimated in 1984 that China had 360 warheads, including non-strategic warheads, and projected that the arsenal would grow to 592 warheads in 1989 and 818 warheads in 1994. This projection never materialized.

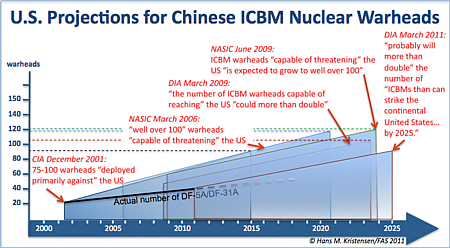

Analysis of projections made by the U.S. intelligence community during the past decade for the growth in Chinese ICBM warheads shows that they have so far been too much too soon (see figure below). The Central Intelligence Agency’s 2001 projection of 75-100 ICBM warheads deployed primarily against the United States by 2015 will not come true unless China increases its production and deployment of the DF-31A missile or begins to deploy multiple warheads on its ICBMs. China will probably only do so if the U.S. deploys a ballistic missile defense system that can nullify the Chinese deterrent.

|

| U.S. projections for Chinese ICBM warheads have generally been too much too soon. Click image for larger version. |

.

Satellite Imagery Interpretations

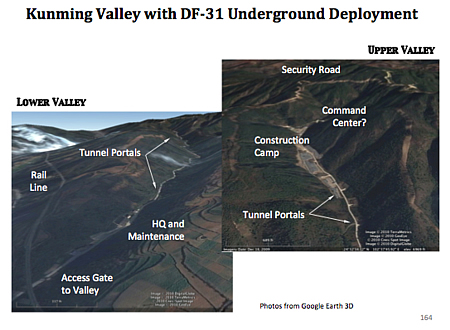

Another issue with the Georgetown University study concerns some of its analysis of commercial satellite imagery. One of the case studies is a series of buildings in a valley south of Kunming in southern China that the study concludes make up an underground deployment site for the DF-31 ICBM (see figure below).

|

| The Georgetown University study suggests that this valley near Kunming in southern China is a DF-31 deployment site. The facility looks more like a munitions depot. It is located at these coordinates: 24.545262°, 102.584378° |

.

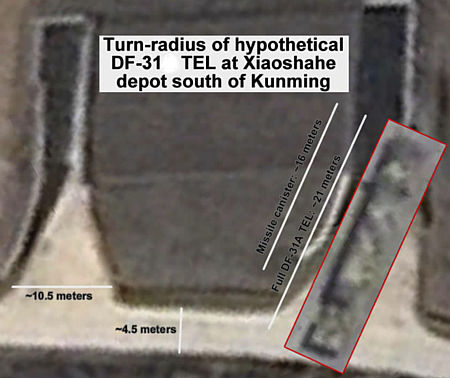

No evidence is presented for this conclusion and the source appears to be a post on the Chinese language web site Sina Military Forum (the link to the story no longer works). “Tunnel portals” in the valley apparently are thought to be for use by DF-31 launchers hiding inside the mountain. Yet the facility does not have any of the characteristics of Chinese DF-31 deployment sites and a minimum of analysis indicates that the portals and roads are too narrow to be used by DF-31 launchers (see figure below). Instead, the buildings in the valley look more like a munitions depot.

|

| This image shows two of the so-called “tunnel portals” identified by the Georgetown University report as being part of a DF-31 deployment site near Kunming. An image of a DF-31/DF-31A launcher is superimposed to illustrate the difficulty it would have turning at the site. The dimensions of the roads indicate that the facility is not for DF-31 launchers, but looks more like a munitions depot.. |

.

Conclusions

The Georgetown University study has collected an impressive amount of scattered information from the Internet about Chinese underground facilities. That is obviously interesting in and of itself, but in terms of assessing Chinese nuclear capabilities, it does the public debate a disservice by disseminating exaggerated and poorly analyzed information.

Readers can obviously read into the report what they want, but a quick Google search for news article headlines about the report shows the damage: “China may have 3000 n-warheads;” “China’s nuclear arsenal ‘many times larger’ than previously thought;” “China ‘hiding up to 3,000 nuclear warheads in secret tunnels.” Many people will not remember the details, but they tend to remember the headlines. A misperception will stick in the public consciousness that China has 3,000 nuclear weapons hidden in tunnels.

But China does not have 3,000 nuclear weapons. It neither has produced the fissile material needed to build that many, not does it have delivery vehicles enough to delivery that many warheads. The Georgetown University study warhead estimate appears to be off by an order of magnitude.

China is in the middle of a significant military modernization and it is important that it is not hyped or exaggerated but analyzed and understood for what is actually happening.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.