Pentagon’s 2011 China Report: Reducing Nuclear Transparency

|

| The Pentagon’s new report on China’s military forces significantly reduces transparency of China’s missile force by eliminating specific missile numbers previously included in the annual overview. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon has published its annual assessment of China’s military power (the official title is Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China). I will leave it to others to review the conclusions on China’s general military forces and focus here on the nuclear aspects.

Land-Based Nuclear Missiles

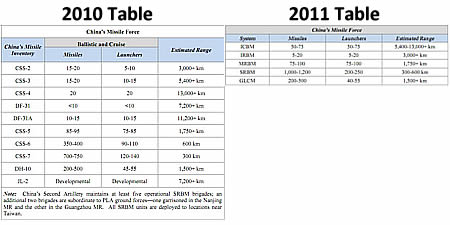

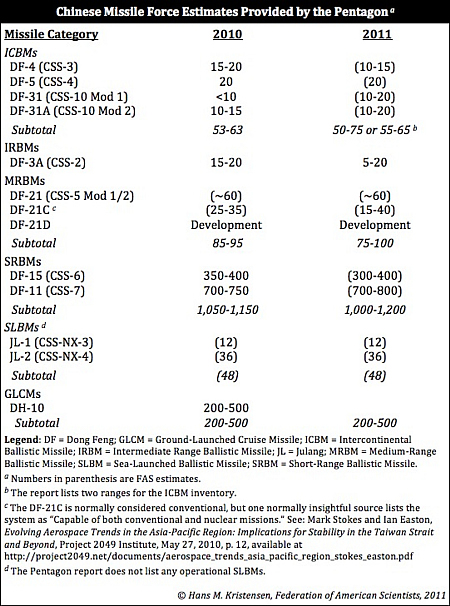

The most noticeable new development compared with last year’s report is that the Pentagon this year has decided to significantly reduce the transparency of China’s land-based nuclear missile force. For the past decade, the Pentagon reports have contained a breakdown of Chinese missiles showing approximately how many they have of each type. Not anymore. This year the details are gone and all we get to see are the overall numbers within each missile range category: ICBMs, IRBM, MRBM, SRBM, and GLCMs.

This is something one would expect the Chinese government to do and not the Pentagon, which has spent the last decade criticizing China for not being transparent enough about its military posture.

What the numbers we’re allowed to see indicate is that China’s missile force has been largely stagnant over the past year. The changes have been in minor adjustments, probably involving:

- Phasing out a few older DF-4s and introducing a few more DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs.

- Reducing the DF-3A force and replacing it with the DF-21 MRBMs (which appears largely unchanged but with greater uncertainty).

- Essentially no increase in number of SRBMs off Taiwan.

- The same number of DH-10 GLCMs.

| Addition: Some news media reports unfortunately misrepresent what the Pentagon report says about Chinese nuclear developments:Washington Times (8/25/11)

Claim: “China expanding its nuclear stockpile” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report says nothing about China expanding its nuclear stockpile (the word “stockpile” does appear in the report at all) but that it is “qualitatively and quantitatively improving its strategic missile forces.” But it is a “limited nuclear force.” Claim: “Richard Fisher, a China military-affairs analyst, said the report is significant for listing strategic nuclear forces that show an estimated increase of up to 25 new ICBMs, some with multiple warheads, in a year….” Fact: The Pentagon report lists 50-75 and 55-63 ICBMs (both ranges are listed). The medium values are 59-62 ICBMs. The 2010 report listed 53-63 (58) ICBMs. That is an increase of 1-4 ICBMs, not 25, which is the highest end of the estimate. The Pentagon report does not say that China has deployed ICBMs with MIRV, but that it “may be” developing a new mobile ICBM, “possible capable of carrying” MIRV. China has been researching MIRV since the 1980s but so far not chosen to deploy any. The one thing that could drive China to a decision to potentially deploy MIRV in the future would be a U.S. ballistic missile defense system that diminished the effectiveness of China’s nuclear deterrent. Claim: (Fisher) “China will not reveal its missile-buildup plans…so this simply is not the time to be considering further cuts in the U.S. nuclear force, as is the Obama administration’s intention.” Fact: The United States has 5,000 warheads, China 240. Only about 60 of the Chinese warheads can reach the United States, and only half of those can reach all of the United States. Claim: “Advanced China n-missiles on India border, says Pentagon” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report does not state that China has deployed nuclear missiles on the Indian border. Instead, the report states in general terms that “To strengthen deterrence posture relative to India, the PLA has replaced” DF-3As “with more advanced and survivable” DF-21s. This is a reference to the DF-21 replacing outdated DF-3A brigades at Chuxiong, Jianshui and Kunming in the Yunnan province and near Delingha and Da Qaidam in the Qinghai province. |

.

Trying to reconstruct the table the way it should have been comes with considerable uncertainty, but here is my best estimate (for corrections I will have to rely on individuals in the Pentagon who think that buying into Chinese government secrecy does not advance U.S. or Northeast Asian interests):

|

| Click on table to download larger version. |

.

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The new Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN appears ready but the Pentagon report states that its JL-2 SLBM “has faced a number of problems and will likely continue flight tests.” The Pentagon previously estimated that the Jin/JL-2 system would become operational in 2010 but the new report now states that it is “uncertain” when the new system will become fully operational.

The range of the JL-2 SLBM is extended, somewhat, from 7,200+ km in the 2010 report to 7,400 km in the 2011 report. This does not change the fact that a Jin-class SLBM would have to deploy deep into the Sea of Japan for its JL-2 to be able to strike the Continental United States. Alaska is within range from Chinese waters, but not Hawaii.

The operational status of the old Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN and its JL-1 SLBM “remain questionable.” Neither class has conducted any deterrent patrols yet.

As a result, China does not appear to have any operational sea-launched ballistic missiles at this point.

The report lists only five nuclear attack submarines with the three fleets, down from six last year, suggesting that retirement of the Han-class (Type 091) continues. The Shang-class (Type 093) is operational, and the Pentagon report states that “as many as five third-generation Type 095 SSNs will be added in the coming years.” The U.S. Navy’s intelligence branch estimated in 2009 that the Type 095 will be noisier than the Russian Akula I but quieter than the Victor III.

Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols during all of 2010, the same level as the previous two years.

Underground Facilities

While there has recently been some sensational reporting (see also here) that China since 1995 has built a 5,000-km “great wall” of tunnels under Hebei mountain in the western parts of the Shaanxi province to hide “all of their missiles hundreds of meters underground,” including the DF-5 (CSS-4) ICBM, the reality is probably a little different.

First, as anyone who has spent just a few hours studying satellite images of Chinese military facilities and monitoring the Chinese internet will know, the Chinese military widely uses underground facilities to hide and protect military forces and munitions. Some of these facilities are also used to hide nuclear weapons. The old DF-4, for example, reportedly has existed in a cave-based rollout posture since the 1970s.

The Pentagon report states that China has “developed and utilized UGFs [underground facilities] since deploying its oldest liquid-fueled missile systems and continue today to utilize them to protect and conceal their newest and most modern solid-fueled mobile missiles.” So it is not new but it is also being used for modern missiles.

| Chinese Underground Missile Launcher Facility |

|

| A Chinese mobile missile launcher, possibly for the DF-11 or DF-15 SRBM, emerges from an underground facility at an unknown location. Image: Chinese TV |

.

Second, the particular facility under Hebei mountain appears to be China’s central nuclear weapons storage facility, as recently described by Mark Stokes. The missiles themselves are at the regional bases, although it cannot be ruled out that some may be near Hebei as well. But Stokes estimates that the warheads are concentrated in the central facility with only a small handful of warheads maintained at the six missile bases’ storage regiments for any extended period of time. The missile regiments themselves could also have nearby underground facilities for storing launchers and missiles, although specifics are not known.

One of the Chinese bases with plenty of underground facilities is the large naval base near Yulin on Hainan Island, which I described in 2006 and 2008. The Pentagon report concludes that this base has now been completed and asserts that it is large enough to accommodate a mix of attack and ballistic missile submarines and advanced surface combatants, including aircraft carriers. The report adds that, “submarine tunnel facilities at the base could also enable deployments from this facility with reduced risk of detection.” That would seem to require the submarine exiting from the tunnel submerged; a capability I haven’t seen referenced anywhere yet.

Conclusions

The 2011 Pentagon report shows that China’s nuclear missile force changed little during the past year but appears to continue the slow replacement of old liquid-fueled missiles with new solid-fueled missiles. China’s efforts to develop a sea-launched ballistic missile capability have been delayed.

In an unfortunate change from previous versions of the Pentagon report, the 2011 version significantly reduces the transparency of China’s nuclear missile forces by removing numbers for individual missile types. This change is particularly surprising given the Pentagon’s repeated insistence that China must increase transparency of its military posture. In this case, military secrecy appears to contradict U.S. foreign policy objectives.

The decision to reduce the transparency of China’s missile force is even more troubling because it follows the recent U.S.-Russian decision to significantly curtail the information released to the public under the New START treaty.

The combined effect of these two decisions is that within the past 12 months it has become a great deal harder for the international community to monitor the development of the offensive nuclear missile forces of the United States, Russia and China.

Tell me again whose interest that serves?

See also: 2010 Pentagon Report on China

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.