By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

By Ivan Oelrich and Hans M. Kristensen

Only one week before Barack Obama is expected to win the presidential election, Defense Secretary Robert Gates made one last pitch for the Bush administration’s nuclear policy during a speech Tuesday at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

What is the opposite of visionary? Whatever, that’s the word that best describes Mr. Gates’s speech. Had it been delivered in the mid-1990s it would not have sounded out of place. The theme was that the world is the way the world is and, not only is there little to be done about changing the world, our response pretty much has to be more of the same.

Granted, Gates’s job is to implement nuclear policy not change it but, at a time when Russia is rattling its nuclear sabers, China is modernizing its forces, some regional states either have already acquired or are pursuing nuclear weapons, and yet inspired visions of a world free of nuclear weapons are entering the political mainstream, we had hoped for some new ideas. Rather than articulating ways to turn things around, Gates’ core message seemed to be to “hedge” and hunker down for the long haul. And, while his arguments are clearer than most, this speech is yet another example of faulty logic and sloppy definitions justifying unjustifiable nuclear weapons.

They Do It So We Must Do It Too

Reductions cannot go on forever, Secretary Gates argues because there is still a mission for nuclear weapons. Using language from the Clinton Administration, he says we can reduce our arsenal but we must also “hedge” against unexpected threats. He said, “Rising and resurgent powers, rogue nations pursuing nuclear weapons, proliferation of international terrorism, all demand that we preserve this hedge. There is no way to ignore efforts by rogue states such as North Korea and Iran to develop and deploy nuclear weapons or Russian or Chinese strategic modernization programs.”

While the potential threats he lists are real and must be addressed, how do nuclear weapons address these threats? And even if there were some nuclear component to our responses, the nature of those responses would be so varied that lumping these threats together muddles the issue. A nuclear response to international terrorism? Even if, for example, al Qaeda used a nuclear weapon to attack an American city, what target would we strike back at with a nuclear weapon? The implicit argument of symmetry is unsustainable. Just as we don’t respond to roadside bombs with our own roadside bombs, nor would we respond to chemical attack with chemical weapons or biological attack with biological weapons. We might respond to nuclear attack with nuclear weapons but we should not allow this to be an unstated assumption. The reason rogue nations, let’s say Iran and North Korea, are developing nuclear weapons is not to counter our nuclear weapons but as a counter to our overwhelming conventional capability. They certainly are not making the mistake of implicitly assuming symmetry.

The near universal logical sleight of hand is to make some argument for nuclear weapons, let’s say we need them because North Korea has them, and then, when people nod in agreement that we need nuclear weapons, let slip in the assumption that this implies we need the nuclear arsenal the administration wants. Not so fast. If North Korea has one, perhaps we need two, but that does not mean we need two thousand.

It helps to clarify the typically foggy nuke-think if we remove Russia and China from the picture and ask whether the United States could justify anything near its currently planned nuclear arsenal only to deter and defeat rogue states and terrorists. Of course not. And perhaps we don’t need nuclear weapons for regional scenarios at all, given our overwhelming conventional capabilities. So those odds and ends are thrown into the pot just to scare, not to explain, and not because there is any well thought out strategy for how nuclear weapons are going to stop a terrorist attack on an American city, or why it be an appropriate response to a regional state that doesn’t have the capability to threaten the survival of the United States.

Russia is a very different case: Russian long-range nuclear forces are the only things in the world today that could destroy us as a nation and society, just as we could destroy them. While relations with Russia are not friendly, no conceivable difference between the United States and Russia justifies this mutual hostage relationship. This pointless threat to our very existence persists because of a failure of imagination typified by this speech. In this case, it is the nuclear weapons that are creating the threat, not protecting us from it.

That Ole Warhead Production Fever

Whatever the supposed justification of nuclear weapons, the primary purpose of the Secretary’s speech seemed to be to promote the Reliable Replacement Warhead or RRW but again, his argument rests on hidden (and unjustified) assumptions and, at times, misstatements of fact. The basic premise is that, without testing, we are slowly but certainly losing confidence in the reliability of our nuclear arsenal. He said, “With every adjustment, we move farther away from the original design that was successfully tested when the weapons was first fielded.”

We do? The implication is that we have no other choice, what we could do in 1990 we simply can’t reproduce today, like handing a modern-day native American a hunk of flint and asking him to chip out an arrowhead. Why should this be? With a budget of billions of dollars, we can’t duplicate parts that we could make twenty years ago? We can spend billions on the National Ignition Facility to create the world’s most powerful laser but we can’t reproduce a 1980s O-ring? The problem the Secretary describes is certainly possible and something we have to be alert to but it isn’t inevitable; we can maintain weapons within design margins as long as we want and in the past—pre-RRW—that was precisely the plan. And parts of the weapon that are not the nuclear core of the bomb can be improved and modernized and tested as much as we want.

But Mr. Gates claims that we are slowly and helplessly drifting, “So the information on which we base our annual certification of the stockpile grows increasing dated and incomplete.” This implies the Stockpile Stewardship Program (SSP) has failed. We believe the Secretary is wrong. Everyone we have talked to who is familiar with the enormous effort that has gone into the SSP says that our understanding of nuclear weapons today is substantially greater than it was the day after our last nuclear test. Our knowledge of the aging of nuclear warheads is increasing faster than the warheads are aging. Early uncertainties and concerns about stability, for example, of the plutonium parts of the weapon have been resolved and the parts have been shown to be stable for many decades, if not a century or more. Our computer models are dramatically and significantly more detailed and sophisticated. In fact, one weapon designer has told us that, given a fixed budget, the best investment of your next dollar would never be in a nuclear test but in more inspections, more computer simulations, more replacement of non-nuclear components, more material tests, more frequent tritium replenishment, and so forth.

|

How Many Times Does Congress Have to Say No? |

|

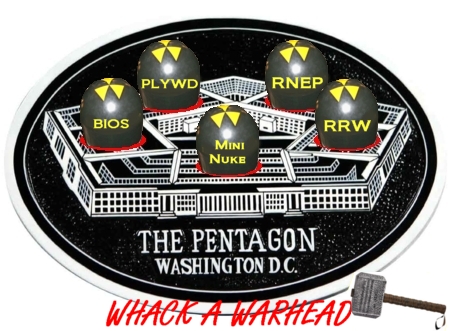

| Every time the Pentagon has proposed a new nuclear warhead since the end of the Cold War, Congress has refused to fund it. Now that the RRW appears to have been whacked, what will the next proposal for a new warhead look like? |

.

Aside from the question of the reliability of current warheads, Mr. Gates argues that we still need an RRW because we need to modernize. The British, French, Russians, and Chinese are modernizing so we must too, obviously. Why? Nuclear weapons are a mature technology. There is no new science in nuclear weapons. They are powerful, efficient explosives. They are intended to blow up things and they have specific missions, which typically involve blowing up specific things. If they can accomplish these missions, what is the problem? If the technology, even the weapons, is decades, even centuries old, if they work then they work. Nuclear weapons are not fighter planes or tanks or submarines, duking it out on a battlefield with the enemy’s opposite number, so our nuclear weapons should be evaluated with regard to the targets they are expected to destroy, not anyone else’s nuclear weapons. They can destroy the targets. We’re done.

The important factor is not the warhead but the delivery vehicle that is intended to bring the warhead to the target. And the reason the United States is not producing new nuclear weapons while Russia and China do is not because they can and we can’t, or they’re ahead and we’re behind, as the Secretary indicated. Rather, the United States has not been producing new nuclear weapons because it didn’t have to – the existing ones are more than adequate – and because not producing has been seen as much more important to U.S. foreign policy objectives. And if Russian and Chinese warhead production is a problem, why not propose how to influence them to change rather than advocating that we repeat their mistake?

The final argument for the RRW is that the US must maintain a nuclear production industry and the RRW is grist for that mill. But many of the RRW technologies and capabilities were developed by the very SSP that Gates now implies is failing. Six years ago – before they came up with RRW after having failed to get permission to build the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) and the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator (RNEP) – the National Nuclear Security Administration assured Congress: “We believe the life extension programs authorized by the Nuclear Weapons Council for the B61, W80, and the W76 will sufficiently exercise the design, production and certification capabilities of the weapons complex” (emphasis added). That assurance was given after the Foster Panel recommended, “developing new designs of robust, alternative warheads.” Now the claim suddenly is that the life extension programs do not sufficiently exercise the weapons complex. At least get the argument straight.

What’s Around the Corner?

We would be more sympathetic to the production argument if the fundamental minimal needs of the nuclear production industry were better thought out and justified, but what we see is an effort to maintain a slimmed down version of what we have without thinking through what we need. In fact, if maintaining the production industry is the core objective, we would have expected the administration to ask for an RRW design that doesn’t need a complex production industry, one that is extremely simple, perhaps using uranium rather than plutonium, perhaps a clunky design but one sure to work that does not require any sophisticated skills that must be maintained in standby in perpetuity.

We’re concerned that in the end Congress will accept a beefed-up life extension program – they seem to have already found a name for it: Advanced Certification Program – that will relax the restrictions for what modifications can be made to existing warheads in order to incorporate as much as the RRW concept as possible and add new capabilities if necessary. Unless the next president significantly changes the nuclear guidance for what the Pentagon is required to plan for, RRW-like proposals will likely continue to make it harder to create a national consensus on the future role of nuclear weapons. And Barack Obama has not explicitly rejected the RRW, but said he does “not support a premature decision to produce the RRW” and “will not authorize the development of new nuclear weapons and related capabilities.” Enhanced life-extended warheads could fit within such a policy.

In the end, justifying the nuclear weapons production industry is shaky because the justification for the weapons themselves is shaky, resting on assertion and Cold War momentum – as Gates’ speech illustrated – more than on rigorous assessments of missions and the security of the nation.

The Secretary’s speech was a disappointing missed opportunity. We are a bit perplexed about why he gave it and gave it now. Perhaps he is putting down a marker for a debate he expects in the next administration and Congress. We welcome that debate because we believe that, with careful attention to definition and no hidden assumptions, the arguments for nuclear weapons fade away.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country.

Nearly one year after the Pentagon certified the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program to continue after it incurred critical cost and schedule overruns, the new nuclear missile could once again be in trouble.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end”

Without information, without factual information, you can’t act. You can’t relate to the world you live in. And so it’s super important for us to be able to monitor what’s happening around the world, analyze the material, and translate it into something that different audiences can understand.