Police Misconduct and Violence: Let the Data Talk

Limited insight into police misconduct makes it difficult to improve policing, but a national registry could help

Police misconduct and violence have vaulted to the forefront of the national discourse on civil rights and safety. Researchers have found that Black people are three and a half times more likely to be killed by police when not holding a weapon, or not attacking, than white people. Tragically, one out of every thousand Black men in the U.S. will be killed by police violence.

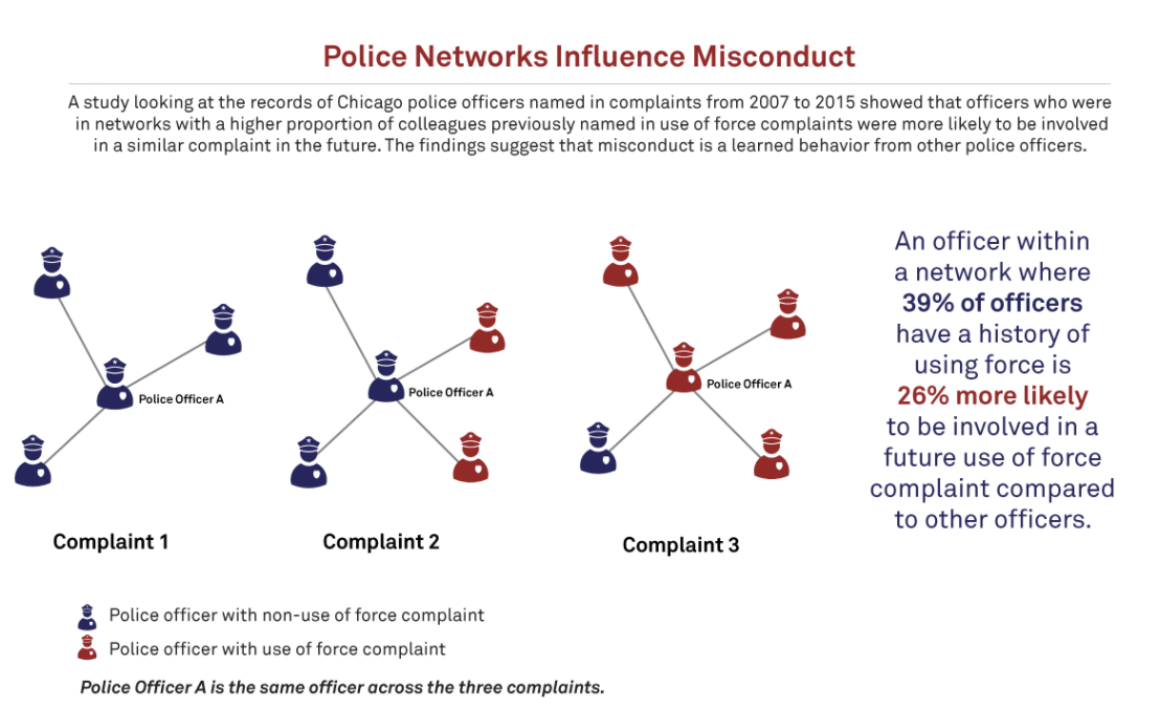

While the removal of offending police officers from their positions would be a straightforward solution, it is rarely easy to permanently expel bad actors from police departments. Yale researchers found that police officers who are fired for misconduct from one department are often hired by another department within three years. These officers also tend to move to smaller departments that serve communities with greater numbers of people of color. To make matters worse, these officers’ bad behavior can spread through the departments in which they work. For example, as depicted in Figure 1, officers involved in excessive force complaints were more likely to work with officers with histories of similar complaints. Because of this behavioral trend and the difficulty of removing transgressive officers, it is unsurprising that law enforcement misconduct and violence remains largely unresolved by police departments or policymakers.

Officers with use of force complaints on their records can set a trend of behavior in their departments where other officers become more likely to receive use of force complaints in the future. Figure reproduced from Ouellet, Hasimi, Gravel, and Papachristos 2019, Criminology and Public Policy.

To keep harmful police misconduct from spreading throughout new police departments, some researchers and policymakers suggest developing a national registry for police behavior. This independent registry would catalogue misconduct among police officers and be available for policymakers and police department leadership to use for decision-making about hiring, training, or policing duties. Currently, a less comprehensive National Decertification Index records officers who have engaged in misconduct severe enough to lose their state policing certifications – typically a requirement to work in a police department. The goal of the Index is to prevent former police officers who were guilty of misconduct from being rehired without their new departments knowing about their prior misconduct. Unfortunately, there is a significant amount of police misconduct that does not result in decertification, such as illegal searches and use of excessive force, but that is still important to track. Tracking all police misconduct in a national registry for police behavior could serve as a significant resource in the effort to reduce destructive policing practices.

However, a national registry of police behavior would face several challenges. For example, each police department has different protocols for complaint records. And even when officer misconduct is reported and addressed by the community, recommendations from civilian review boards on officer misconduct are adopted infrequently. Police unions can also create obstacles to weeding out bad actors in police departments. For a national registry of police behavior to be maximally effective in helping to reform policing, additional measures need to be taken in parallel.

Policymakers, community members, and police departments are exploring policy options for policing, and national registries of misconduct and complaints could help indicate trends of behavior in officers, aiding decision-makers in their pursuit of more just policing systems.

This CSPI Science and Technology Policy Snapshot expands upon a scientific exchange between Congressman Bill Foster (D, IL-11) and his new FAS-organized Science Council.

The transition to a clean energy future and diversified sources of energy requires a fundamental shift in how we produce and consume energy across all sectors of the U.S. economy.

Advancing the U.S. leadership in emerging biotechnology is a strategic imperative, one that will shape regional development within the U.S., economic competitiveness abroad, and our national security for decades to come.

Inconsistent metrics and opaque reporting make future AI power‑demand estimates extremely uncertain, leaving grid planners in the dark and climate targets on the line

As AI becomes more capable and integrated throughout the United States economy, its growing demand for energy, water, land, and raw materials is driving significant economic and environmental costs, from increased air pollution to higher costs for ratepayers.