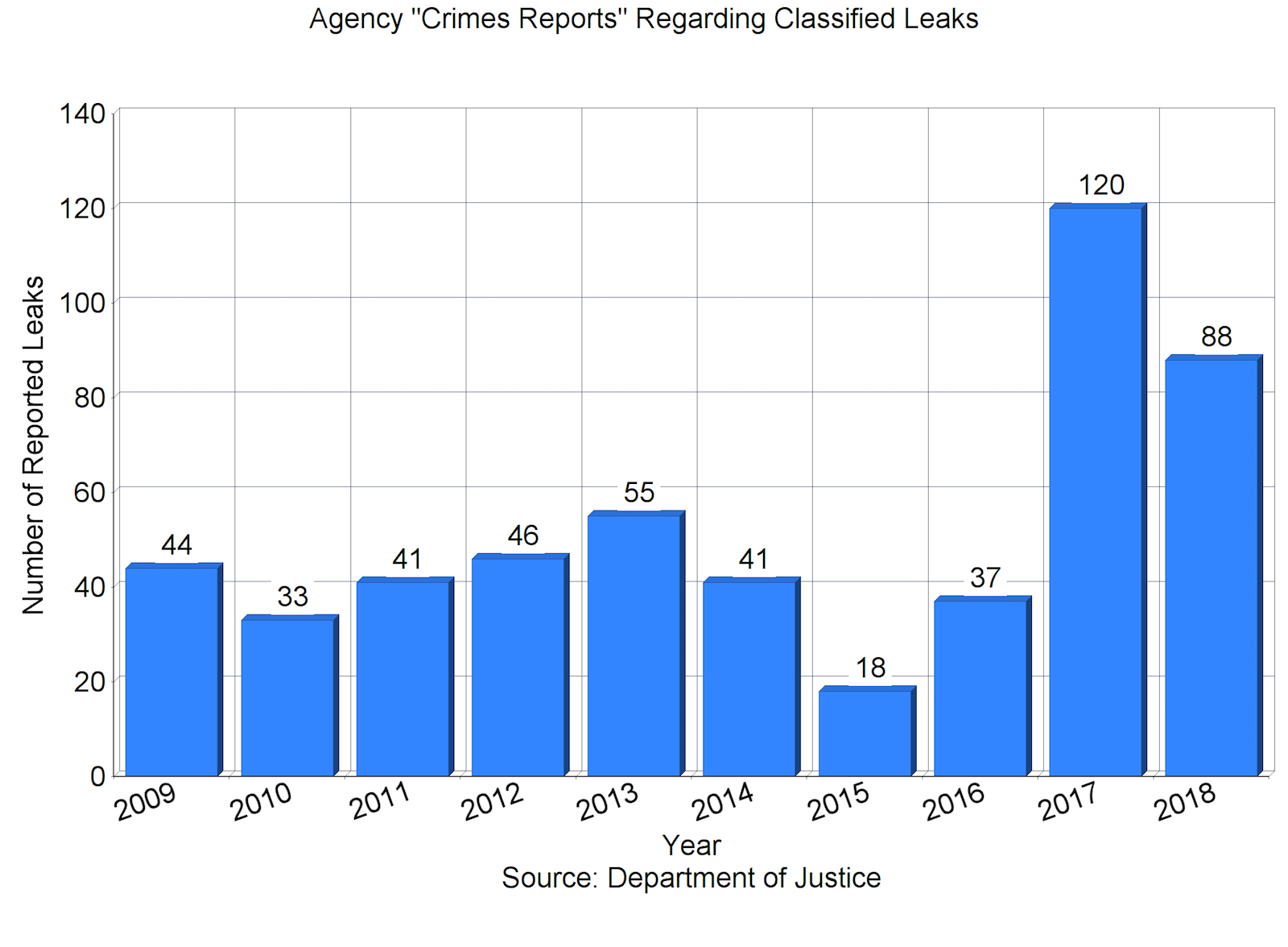

The number of leaks of classified information reported as potential crimes by federal agencies reached record high levels during the first two years of the Trump Administration, according to data released by the Justice Department last week.

Agencies transmitted 120 leak referrals to the Justice Department in 2017, and 88 leak referrals in 2018, for an average of 104 per year. By comparison, the average number of leak referrals during the Obama Administration (2009–2016) was 39 per year.

There are a “staggering number of leaks,” then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions said at an August 4, 2017 briefing about efforts to prevent the unauthorized disclosures.

“Referrals for investigations of classified leaks to the Department of Justice from our intelligence agencies have exploded,” AG Sessions said at that time. He outlined several steps that the Administration would take to combat leaks of classified information, including tripling the number of active leak investigations by the FBI.

“We had about nine open investigations of classified leaks in the last 3 years,” he told the House Judiciary Committee at a November 2017 hearing. “We have 27 investigations open today.” (Some of those investigations pertain to leaks that occurred before President Trump took office.)

“We intend to get to the bottom of these leaks. I think it reached—has reached epidemic proportions. It cannot be allowed to continue,” Sessions said then, “and we will do our best effort to ensure that it does not continue.”

But it has continued. Despite preventive efforts, the 2018 total of 88 leak referrals was still higher than any reported pre-Trump figure. (The previous high in recent decades had been 55 referrals in 2013 and in 2007. The lowest was 18 in 2015.)

*

Not all leaks of classified information generate such criminal referrals. Disclosures that are inadvertent, insignificant, or officially authorized would not be reported to the Justice Department as suspected crimes.

Meanwhile, only a fraction of the classified leaks that are reported by agencies ever result in an investigation, and only a portion of those lead to identification of a suspect and even fewer to a prosecution.

“While DOJ and the FBI receive numerous media leak referrals each year, the FBI opens only a limited number of investigations based on these referrals,” the FBI told Congress in 2009. “In most cases, the information included in the referral is not adequate to initiate an investigation.”

The newly released aggregate data on classified leak referrals serve as a reminder that leaks of classified information are a “normal,” predictable occurrence. There is not a single year in the past decade and a half for which data are available when there were no such criminal referrals.

But the data as released leave several questions unanswered. They do not reveal how many of the referrals actually triggered an FBI investigation. They do not indicate whether the leaks are evenly distributed across the national security bureaucracy or concentrated in one or more “problem” agencies (or congressional committees). And they do not distinguish between leaks that simply “hurt our country,” as the Attorney General put it, and those that are complicated by a significant public interest in the information that was disclosed.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

In the absence of guardrails and guidance, AI can increase inequities, introduce bias, spread misinformation, and risk data security for schools and students alike.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.