The Nuclear Weapons “Procurement Holiday”

It has become popular among military and congressional leaders to argue that the United States has had a “procurement holiday” in nuclear force planning for the past two decades.

“Over the past 20-25 years, we took a procurement holiday” in modernizing U.S. nuclear forces, Major General Garrett Harencak, the Air Force’s assistant chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, said in a speech yesterday.

Harencak’s claim strongly resembles the statement made by then-commander of US Air Force Global Strike Command, Lt. General Jim Kowalski, that the United States had “taken about a 20 year procurement holiday since the Soviet Union dissolved.”

Kowalski, who is now deputy commander at US Strategic Command, made a similar claim in May 2012: “Our nation has enjoyed an extended procurement holiday as we’ve deferred vigorous modernization of our nuclear deterrent forces for almost 20 years.”

One can always want more, but the “procurement holiday” claim glosses over the busy nuclear modernization and maintenance efforts of the past two decades.

About That Holiday…

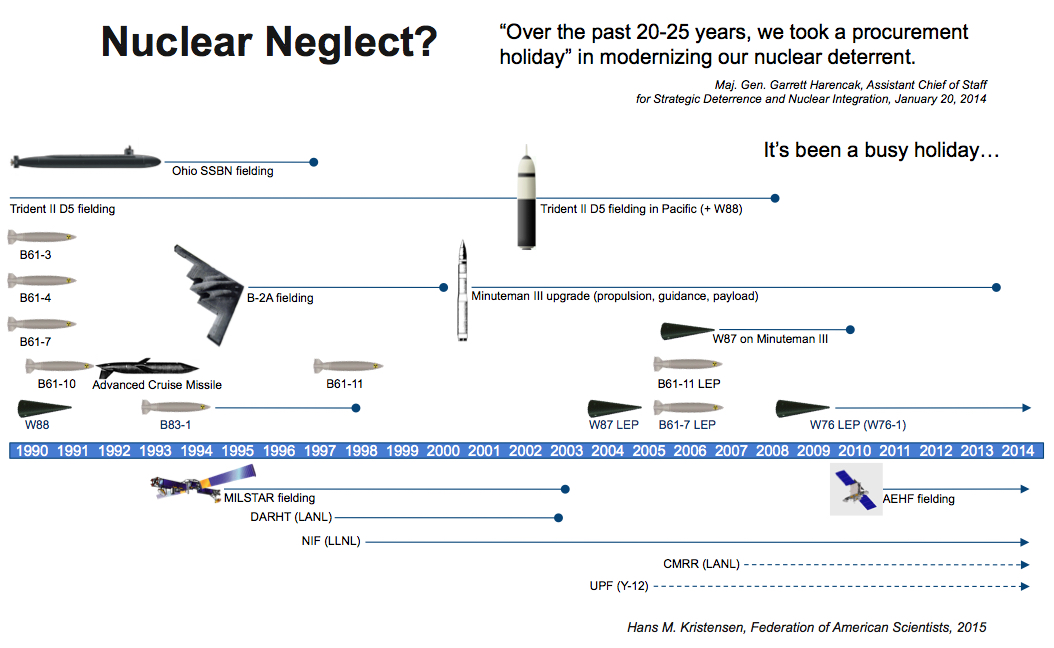

If “holiday” generally refers to “a day of festivity or recreation when no work is done,” then its been a bad holiday. For during the “procurement holiday” described by Harencak, the United States has been busy fielding and upgrading submarines, bombers, missiles, cruise missiles, gravity bombs, reentry vehicles, command and control satellites, warhead surveillance and production facilities (see image below).

Despite claims about a two-decade long nuclear weapons “procurement holiday,” the United States has actually been busy modernizing and maintaining its nuclear forces.

The not-so-procurement-holiday includes fielding of eight of 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (the last in 1997), fielding of the Trident II sea-launched ballistic missile (the world’s most reliable nuclear missile), all 21 B-2A stealth bombers (the last in 2000), an $8 billion-plus complete overhaul of the entire Minuteman III ICBM force including back-fitting it with the W87 warhead, five B61 bomb modifications, one modification of the B83 bomb, a nuclear cruise missile, the W88 warhead, completed three smaller life-extensions of the W87 ICBM warhead and two B61 modifications, and developed and commenced full-scale production of the modified W76-1 warhead.

Harencak’s job obviously is to advocate nuclear modernization but glossing over the considerable efforts that have been done to maintain the nuclear deterrent for the past two decades is, well, kind of embarrassing.

Russia and China have continued to introduce new weapons and the United States is falling behind, so the warning from Harencak and others goes. But modernizations happen in cycles. Generally speaking, the previous Russian strategic modernization happened in the 1970s and 1980s (the country was down on its knees much of the 1990s), so now we’re seeing their next round of modernizations. Similarly, China modernized in the 1970s and 1980s so now we’re seeing their next cycle. (For an overview about worldwide nuclear weapons modernization programs, see this article.)

The United States modernized later (1980s-2000s), and since then has focused more on refurbishing and life-extending existing weapons instead of wasting money on mindlessly deploying new systems.

What the next cycle of U.S. nuclear modernizations should look like, how much is needed and with what kinds of capabilities, requires a calm and intelligent assessment.

Comparing Nuclear Apples and Oranges With a Vengeance

“Once you strip away all the emotions, once you strip away all the ‘I just don’t like nuclear weapons,’ OK fine. Alright. And I would love to live in a world that doesn’t have it. But you live in this world. And in this world there still is a nuclear threat,” Harencak said yesterday in an apparent rejection of at least part of his Commander-in-Chief’s 2009 Prague speech.

“This nuclear deterrent, here in January 2015, I’m here to tell you, is relevant and is as needed today as it was in January 1965, and 1975, and 1985, and 1995. And it will be till that happy day comes when we rid the world of nuclear weapons. It will be just as relevant in 2025, ten years from now…it will still be as relevant,” he claimed.

God forbid we have emotions when assessing the nuclear mission, but I fear Harencak may be doing the deterrent mission a disservice with his over-zealot nuclear advocacy that belittles other views and time-jumps from Cold War relevance to today’s world.

Whether or not one believes that nuclear weapons are relevant and needed (or to what extent) in today’s world, to suggest that they are as relevant and as needed today as during the nail-biting and gong-ho conditions that characterized the Cold War demonstrates a surprising lack of understanding and perspective. Remember: the Cold War that held the world hostage at gunpoint with tens of thousands of nuclear weapons deployed around the world only minutes from global annihilation?

Even with Russian and Chinese nuclear modernizations, there is no indication that today’s threats or challenges are even remotely as dire or as intense as the Cold War.

Instead of false claims about “procurement holiday” and demonization of other views – listen for example to Harencak’s new bomber argument: if you don’t want to pay for my grant child to destroy enemy targets with the next-generation bomber, then send your own grandchild! – how about an intelligent debate about how much is needed, for what purpose, and at what cost?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.