Chinese Nuclear Developments Described (and Omitted) by DOD Report

By Hans M. Kristensen

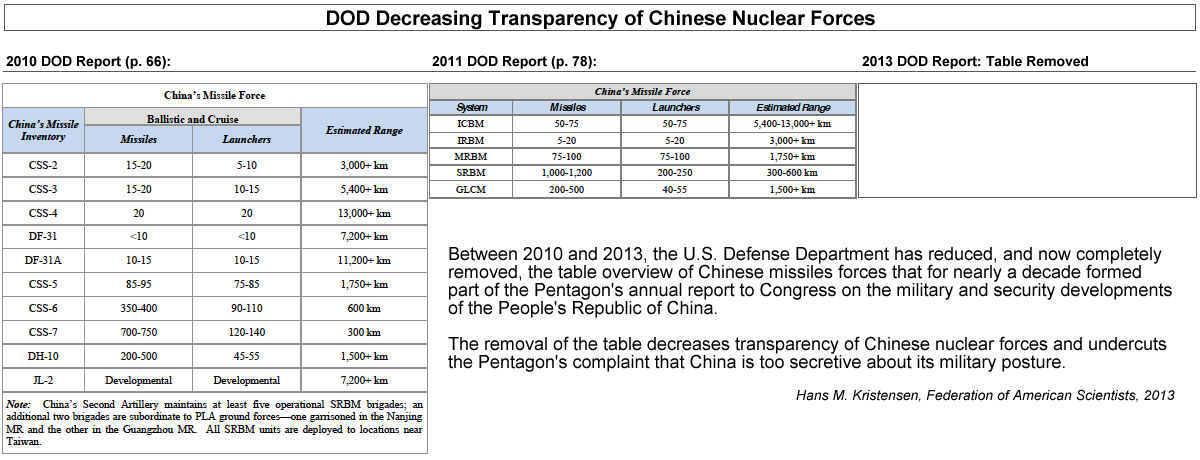

Going, going, gone! In its latest annual report to Congress on the military and security developments of the People’s Republic of China, the Pentagon has removed the last public authoritative overview of Chinese nuclear forces.

Until 2010, the annual reports included a table with a detailed breakdown of the different types of ballistic missiles that enabled the public to monitor the development of China’s nuclear modernization. In 2011, however, things began to change when a less detailed table was included that only showed overall categories of missiles. That version appeared in 2012 as well, but the 2013 report includes no table at all of China’s missile forces.

The tidbits of information left in the report indicate an ICBM force that is modernizing but leveling out and an SSBN force that is approaching functional capability.

Land-Based Nuclear Forces

DOD reports the same number of ICBMs as last year, 50-75. The Pentagon considers a missile with a range of at least 5,500 km to be an ICBM, so this number includes the DF-5A, DF-31A, DF-31 and DF-4. Of these, only the DF-5A and DF-31A can reach the continental United States.

The 50-75 ICBMs is the same number DOD has reported for the past three years, which indicates that the ICBM force level has leveled out for now. But DOD predicts that additional DF-31As will be deployed over the next two-three years.

The report also repeats the prediction from previous years that China “may also be developing” a new road-mobile ICBM that is “possible capable of” carrying MIRVed warheads. The U.S. Intelligence Community has for several decades assessed that China has a capability to develop and deploy MIRV but that it has not yet done so. One sentence in the report comes close to saying that that’s about to change with “The new generation of mobile missiles, with warheads consisting of MIRVs and penetration aids,” but the report does not confirm widespread rumors (see here and here) that a 10-warhead DF-41 ICBM was test launched last year. All appeared to feed off this article. Many MIRV reports appear to confuse warheads with decoys and penetration aids.

The report does not provide an update of nuclear medium-range missiles, except confirming that a few aging liquid-fuel DF-3As are still operational. They will likely be retired within the next few years.

As one would imagine, the new and increasingly mobile missile force requires updating the command and control system. The DOD report states that China has done so and states that “improved communications links” means that “the ICBM units now have better access to battlefield information, uninterrupted communications connecting all command echelons, and the unit commanders are able to issue orders to multiple subordinates at once, instead of serially via voice commands.”

At the same time, further increases in the number of mobile ICBMs, the DOD report states, “will force the PLA to implement more sophisticated command and control systems and processes that safeguard the integrity of nuclear release authority for a larger, more dispersed force.”

Sea-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report states that China has added a third Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN to its fleet and that two more are in various stages of construction. Their nuclear ballistic missile, the Julang-2, is not yet operational, however, but the report indicates that has missile program has overcome technical difficulties, completed a series of successful testing in 2012, and appears ready to reach initial operational capability in 2013.

There is no confirmation of the rumor that the JL-2 has a capability to carry multiple warheads.

The single Xia-class (Type 92) SSBN that China built back in the early 1980s has never been fully operational. It is still afloat, moored at the Jianggezhuang naval base near Qingdao in the Shandong province. The boat will likely be retired, along with its Julang-1 SLBMs, once the Jin-class SSBNs become fully operational.

Moreover, the report predicts that China within the next decade might begin construction of a new class of SSBNs, known as the Type 096. If so, that suggests that the Jin-class design may not have been considered a success.

A Jin-class (top) ballistic missile submarine and Shang-class attack submarine are seen docked at the naval base near Longpo on Hainan Island in this DigitalGlobe/GoogleEarth satellite image from June 27, 2012. Jin-class SSBN were first seen at Hainan in February 2008.

Once fully operational, the DOD report states, SSBNs based at Hainan Island “would then be able to conduct nuclear deterrence patrols.” But now China will operate the SSBN fleet remains to be seen. It might begin to mimic deterrence patrols of other nuclear weapon states, but it seems unlikely that China will begin to deploy nuclear-armed missiles on its SSBNs under normal circumstance because the Central Military Commission is unlikely to hand over nuclear warheads to the armed forces unless in an emergency.

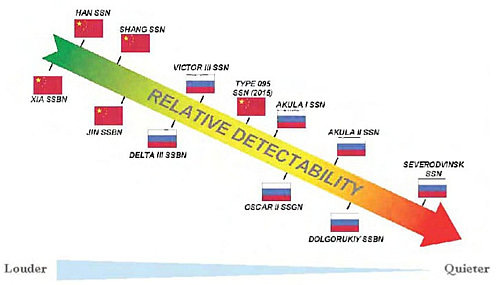

Moreover, Chinese SSBNs are relatively noisy (see graph below) and vulnerable to enemy anti-submarine capabilities, so it seems contrary to China’s core strategic objective of protecting its retaliatory nuclear capability to send some of it out to sea where it can be sunk by enemy attack submarines.

This vulnerability is compounded by the fact that Chinese SSBNs have never conducted a deterrence patrol (see below), which makes the Chinese navy woefully inexperienced in operating an SSBN effectively and safely.

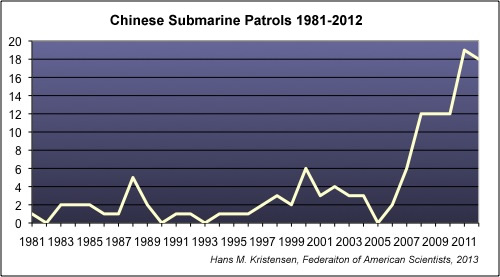

Data obtained from U.S. Naval Intelligence under the Freedom of Information Act shows that Chinese missile submarines have never conducted a deterrent patrol. The attack submarine fleet is more active, with patrols having more than quadrupled over the past decade from around four per year to approximately eighteen patrols last year (see graph).

The increase in general-purpose submarine patrols has coincided with the introduction of the Chang-class (Type 093) nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) from 2005, but probably also reflects operations by more advanced diesel-electric submarines. The introduction of Type 093 SSNs has been slow, however, with only two in service and four improved version under construction to replace the remaining aging first-generation Han-class (Type 091) class SSNs.

Within the next decade, the DOD report predicts, China will likely begin construction of a new class of nuclear-powered attack submarines (Type 096), which might be equipped with land-attack cruise missiles.

Air-Based Nuclear Forces

The DOD report does not explicitly credit the Chinese air force with a nuclear capability but it probably has a limited secondary mission with nuclear gravity bombs. The H-6 medium-range bomber was used to carry out a dozen nuclear tests in the 1970s and 1980s.

The report states that China is modifying the H-6 to “a new variant that possesses greater range and will be armed with a long-range cruise missile.” Elsewhere the report states that H-6 upgrades “may provide the capability to carry new, longer-range cruise missiles.” So whether the H-6 upgrades involve one or more types of long-range cruise missiles is a little unclear.

So far the air-launched cruise missiles have not been credited with nuclear capability, although the ground-launched DH-10 (which is not mentioned in the DOD report) was described as “conventional or nuclear” by the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center in 2009.

Conclusions and Implications

Chinese nuclear modernizations continue with modest pace with focus on safeguarding a retaliatory capability by replacing land-based liquid-fuel missiles with solid-fuel versions, increasing mobile ICBMs, and building a small fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

The size of the ICBM force appears to be leveling out for now, although more may be deployed in the future. And once the 36 JL-2 SLBMs on the three Jin-class SSBNs become operational, they will increase the Chinese nuclear ballistic missile force by approximately 27 percent compared with the current inventory.

Yet because older types are also being retired, the impact on the size of the total nuclear weapons stockpile so far appears to be modest. Earlier this year, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Affairs, Madelyn Creedon, testified before the Senate that despite China’s nuclear force modernizations, “we estimate that it has not substantially increased its nuclear warhead stockpile in the past year…” Moreover, STRATCOM Commander General Kehler last year rejected claims by some that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than the “several hundred” estimated by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

The complete deletion of the table overview of China’s missile forces is striking because the Pentagon for years has been complaining about a lack of transparency in China’s military modernization. Ironically, this complaint was repeated when the Pentagon briefed this year’s report. Said Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for East Asia, David Helvey:

“So what – what concerns me – is the extent to which China’s military modernization occurs in – in the absence of the type of openness and transparency that others are certainly asking of China and the potential implications and consequences of that lack of transparency on the security calculations of others in the region. And so it’s that uncertainty, I think, that’s of greater concern.”

Instead of assisting Chinese nuclear secrecy, the United States should push for transparency and accountability. Authoritative overviews of Chinese nuclear force developments are important to enable the public to assess implications of China’s nuclear modernization and to counter attempts by those who use the uncertainty created by lack of information to hype the threat in order to justify excessive military spending.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Satellite imagery has long served as a tool for observing on-the-ground activity worldwide, and offers especially valuable insights into the operation, development, and physical features related to nuclear technology.

This report outlines a framework relying on “Cooperative Technical Means” for effective arms control verification based on remote sensing, avoiding on-site inspections but maintaining a level of transparency that allows for immediate detection of changes in nuclear posture or a significant build-up above agreed limits.

The grant comes from the Carnegie Corporation of New York (CCNY) to investigate, alongside The British American Security Information Council (BASIC), the associated impact on nuclear stability.

Satellite imagery of RAF Lakenheath reveals new construction of a security perimeter around ten protective aircraft shelters in the designated nuclear area, the latest measure in a series of upgrades as the base prepares for the ability to store U.S. nuclear weapons.