How A Defunct Policy Is Still Impacting 11 Million People 90 Years Later

Have you ever noticed a lack of tree cover in certain areas of a city? Have you ever visited a city and been advised to avoid certain districts or communities? Perhaps you even recall these visual shifts occurring immediately after crossing a particular road or highway?

If so, what you experienced was likely by design:

In the early 20th century, Black communities across the U.S. were subjected to economic constraint and social isolation through housing policies that mandated segregation. Black communities were systematically excluded from the housing benefits offered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal and Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC). The HOLC served as the basis of the National Housing Act of 1934, which ratified the Federal Housing Authority (FHA).

Housing policy discrimination was further exacerbated by the FHA refusing to insure mortgages near and within Black neighborhoods. The HOLC provided lenders with maps that circled areas with sizeable black populations with red markers—a practice now referred to as redlining. While the systematic practice of redlining ended in 1968 under The Fair Housing Act of 1968, redlining continues to economically impair over 11 million Americans—and less than half are Black.

You are probably thinking (1) how is this possible? (2) How could a defunct 20th-century policy designed to discriminate against Black communities still impact over 11 million—mostly non-Black—Americans today? The answer is the same for both questions: place-based discrimination.

Policies such as redlining are designed to worsen the material conditions of a target group by preventing investment in the places where they live. Over time, this results in physical locations that are systemically denied access to features such as loans, enterprise, and ecosystem services simply due to their location or place. Place-based discrimination is the principal mechanism of redlining effects, and consequently, costs taxpayers millions of dollars per year.

What is the problem?

Starting in the 1990s, during the Clinton Administration, billions of dollars in tax credits were devoted towards community development and economic growth through the use of special tax credits that attract private investments (Table 1). One of the principal agents from this funding to address place-based discrimination was the creation of Community Development Entities (CDEs). According to the New Markets Tax Credit Coalition, CDEs are private entities that have “demonstrated” an interest in serving or providing capital to low-income- communities (LICs) and individuals (LIIs). Once certified, CDEs are eligible to apply for a special tax credit, New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), through the Community Development Financial Institution (CDFI) Fund.

However, this program, and others like it, have had a negligible impact on addressing the systemic implications of redlining . A recent Urban Institute report found that inequity in capital flow and investment trends within cities (i.e., Chicago) is driven by residential lending patterns. Highlighting the inequalities that exist between investment among neighborhoods with different racial and income demographics, the analysts surmise that redressing economic downturn involves expanding investments into divested neighborhoods. To date, more than $71 billion have been awarded to CDE’s, and yet, historically-redlined areas remain economically desolate. If these programs are intended to economically revitalize historically-redlined areas, then these programs are not doing what they are supposed to do.

One example of this is the city of Philadelphia:

Philadelphia, a city in the top ten for redlined populations, possesses tens of thousands of vacant buildings and lots that are overlaid by redlining and riddled with brownfield sites. According to the Philadelphia Office of the Controller, historically redlined communities of Philadelphia continue to experience disproportionate amounts of poverty, poor health outcomes, limited educational attainment, unemployment, and violent crime compared to non-redlined areas in the city.

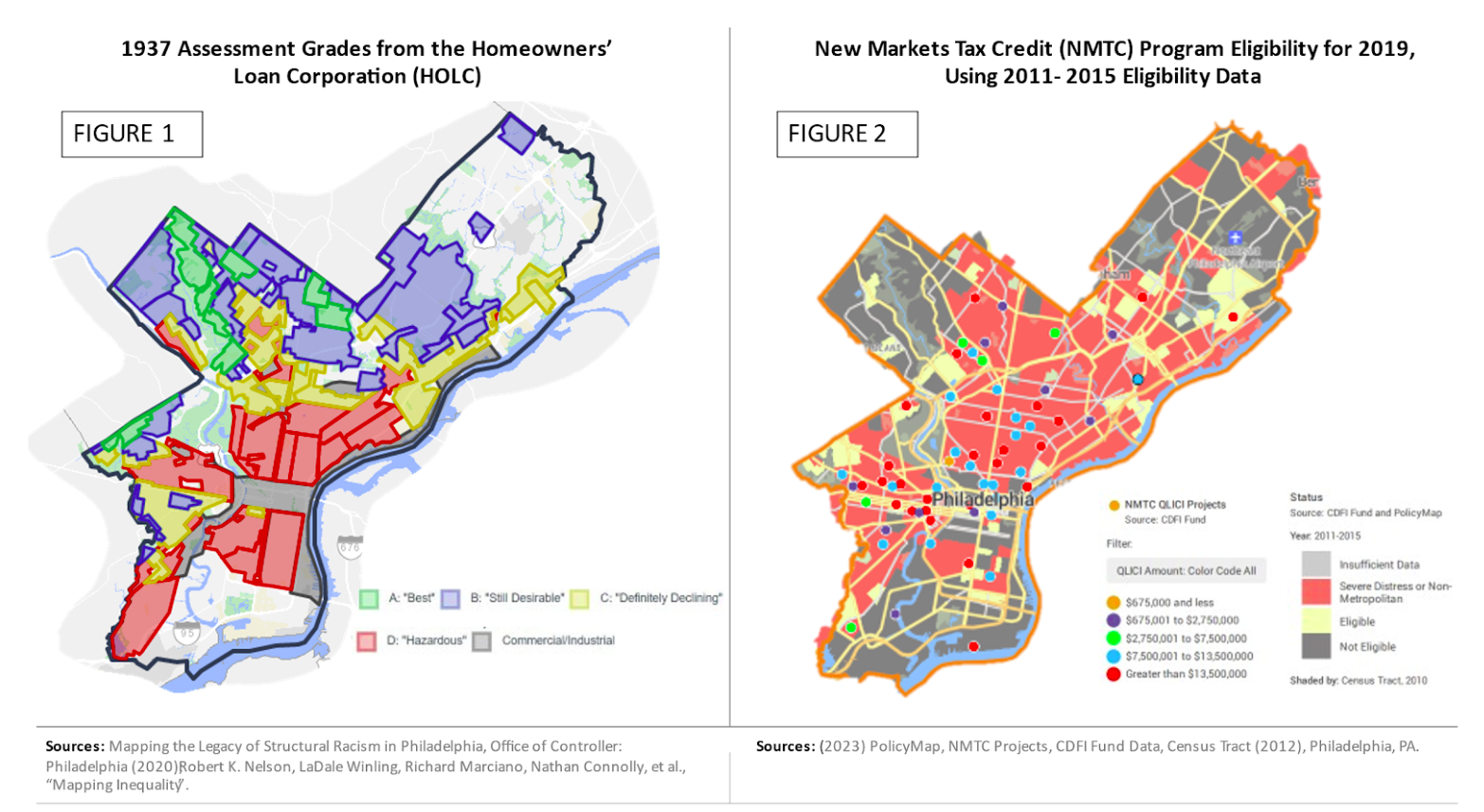

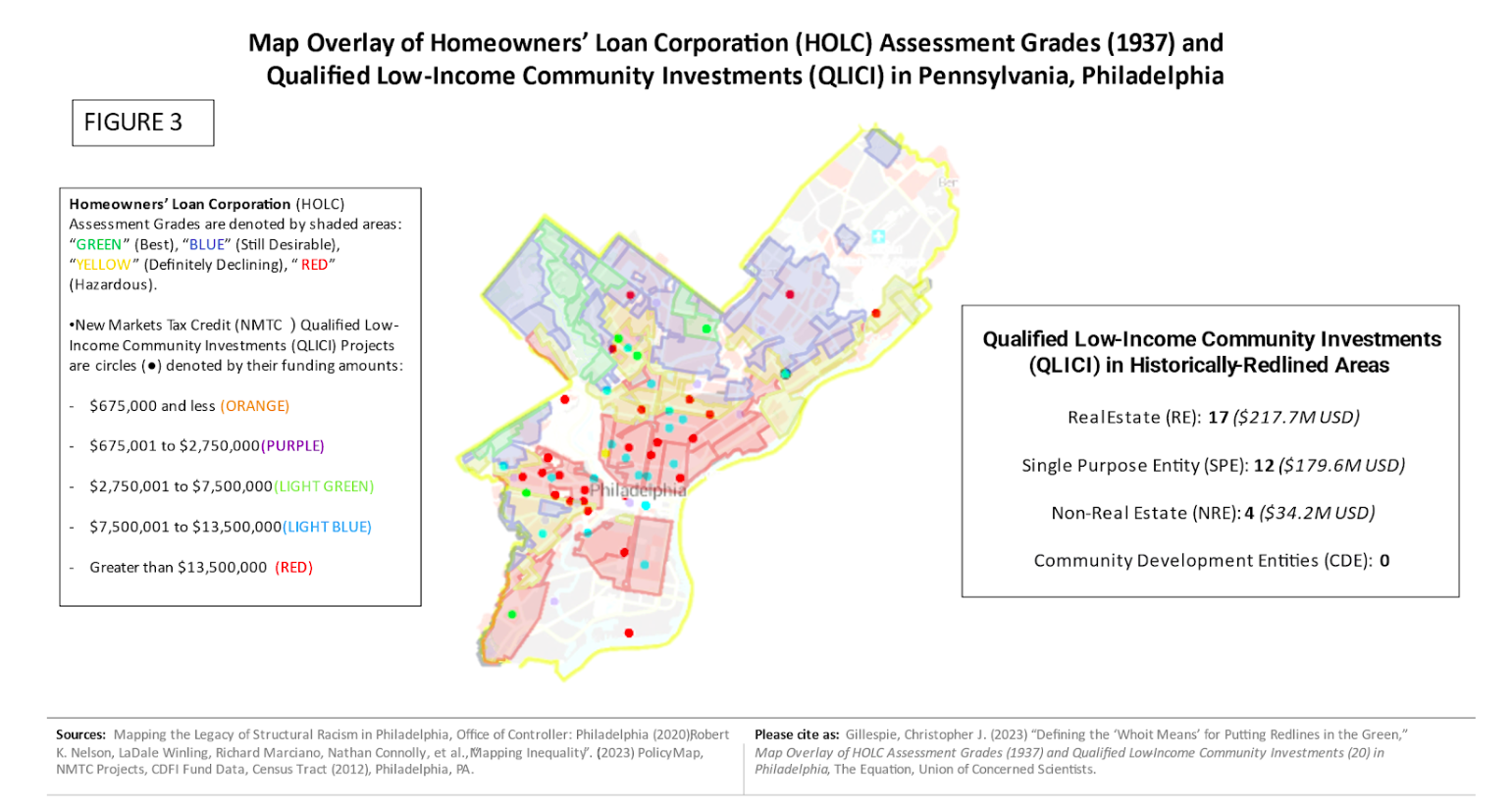

By analyzing HOLC assessment grades (1937) and New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility (i.e., PolicyMap, projects from 2015-2019) for Philadelphia, PA, I found that of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

HOLC assessment grades (1937) vs. New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) Program Eligibility

Of the 30+ Qualified Low-Income Community Investments (QLICIs) in historically-redlined areas, totaling over $400 million in tax credits, none are categorized as Community Development Entities (CDEs).

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia City Council just passed a budget that allocates a record $788 million to the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD). Recent studies show that fatal encounters with police are more likely to occur within historically-redlined areas. It appears the nicest buildings in redlined areas may very well be police stations.

Yet, public investment has been more concerned with maintaining systems of oppression than reversing them. Why continue to invest in systems that do not create wealth? No matter your perception of American policing, the following is clear: policing does not create wealth for distressed communities.

Currently, there are 200+ cities and thousands of communities that are, like Philadelphia, enduring the systemic implications of redlining.

What would happen if public investments were allocated towards restorative policy actions within historically-redlined areas?

A federal program that amalgamates the best elements of community-driven inventiveness into a vehicle for innovative and sustainable economic development. That is, a program that promotes economic revitalization of historically-redlined communities through multipurpose, community-owned enterprises called Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs).

What is the policy action?

One thing that urban policy initiatives have made clear, is that distressed communities are prime real-estate targets for private developers . A new federal effort could ensure that investment opportunities are also accessible to community members seeking to launch place-based businesses and enterprises. Businesses and enterprises of this sort will not only reduce urban blight in historically-redlined communities, but also serve as avenues for the direct state, local, and private investment needed to address historical inequities.

The Biden-Harris Administration can combat redlining through a placed-based community investment program, coined Putting Redlines in the Green: Economic Revitalization Through Innovative Neighborhood Markets (PRITG), that affords historically-redlined communities the ability to establish their own profitable enterprise before outside parties (i.e., private developers).

These Innovative Neighborhood Markets (INMs) would be resource hubs that provide affordable grocery items (i.e., fresh produce, meats, dairy, etc.); an outlet for residents of the community to market goods and services (i.e., small businesses); and create cross-sector initiatives that build community enterprise and increase greenspace (i.e., Farm to Neighborhood Model [F2NM], parks, gardens, and tree cover). Most importantly, INM’s are community owned. Through community governance, the community elects and authorizes the types of place-based businesses and enterprises that are present within their INM.

Do you remember the Philadelphia example from earlier?

Under PTRIG, a number of those underutilized structures or vacant spaces are transformed into a vested, profitable, and sustainable community resource. The majority of the financial capital remains within the community, and economic gains are partially earmarked for community revitalization (i.e., soil remediation for brownfield sites, community restoration, and construction of greenspace).

All Taxpayers Benefit

By legally and financially empowering communities with ownership, PRITG will incentivize investment and development that can actually reduce taxpayer liability. For example, the INM can generate the funding to invest in more attractive (and expensive) treecover and landscaping that will reduce the impact of heat islands and imperviousness related to redlining, thereby reducing taxpayer liability by more than $308 million dollars per year. Implementation of PTRIG will decrease taxpayer burden through profit-driven and self-supporting community services.

“Fair and Equal” Access

Another beneficial aspect of this policy involves increasing community access to financial provisions without third-party obstacles (i.e., CDEs and CDFIs). Black and Hispanic home loan applicants are charged higher interest rates than White home loan applicants, resulting in Black and Hispanic borrowers paying $765 million in additional interest per year. Discriminatory practices only succeed in worsening community divestment and increasing the resident displacement which disproportionately impact minority residents. Through the economic-agency provided by PRITG, historically-redlined communities would have heightened protection against lending discrimination, gentrification, and displacement.

Moreover, PTRIG would reinforce the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC)’s Combating Redlining Initiative in ensuring that formerly redlined neighborhoods receive “fair and equal access” to the lending opportunities that are—and always have been—available to non-redlined, and majority-White, neighborhoods.

While INMs possess aspects of grocery stores, community banks, business improvement districts (BIDs), and farmers markets, they would differ in one particular area: community wealth.

What is Community Wealth?

As someone who grew up in Champaign, Illinois (Douglas Park), and whose family currently lives in a historically-redlined community (Lansing, MI), it brings me peace to reimagine my community with an INM.

Until my early 20’s, I spent most of my life largely unaware of the importance of community wealth on individual empowerment and its impact on the maintenance of cultural identity. For me, reimagining my community with an INM is not just about correcting the past, it is about enriching the uniqueness of what makes our home, Home.

In general, a community wealth building process needs to address the lack of an asset in a way that builds community sustainability. That is the materialization of a communal epicenter(s) that produces a sense of ownership and pride.

So how would INMs build community wealth? Simple. The community, as a whole, would be defined as the ownership group. Each community member would be legally referenced as a shareholder of this newly acquired, financially-appreciating, community-owned enterprise.

Community Ownership Key to Community Wealth

According to Evan Absher, Chief Executive Officer at Folks Capital, there are currently two broad ways of understanding community ownership.

The first type involves community ownership in the form of trusts or fiduciary arrangements between a community entity and an independent financial establishment. This structure creates a community entity that holds the financial wealth and is subject to some form of community governance. This structure includes entities such as Community Investment Trusts, Community Land Trusts, and Mixed-Income Neighborhood Trust. These structures ensure permanent and lasting control of the land and fidelity to charitable purposes. However, these entities often do not increase actual ownership or produce meaningful wealth at the individual or family levels. Further, they are often nonprofits and can struggle with attracting capital and sustainability.

The second type of community ownership is specifically targeted at individuals and families. These are models that focus on financial agency and ownership of land and property by people within communities. This concept includes models such as employee-ownership, Co-operatives, ROC-USA’s model, and Folks Capital’s Neighborhood Equity Model. These models have an advantage in wealth building and agency for the families involved. The benefit of this second concept of community ownership is that community members have the autonomy to (1) choose to sell their ownership share back to the community fund; (2) receive pro rata (dividend) payments; and/or (3) if the community chooses, sell the enterprise to “would-be gentrifiers.”

Regardless, the community receives more empowerment than was ever offered by previous economic revitalization models (i.e., Opportunity Zones) [See Table 1]. However these models sometimes lack the permanence or control of the other models. If not structured thoughtfully, this lack of control poses a risk of further gentrification.

Regardless of the approach, all models should seek first to center communities and people in the governance and benefits of the model. Institutionalizing models is not the objective. Closing the wealth gap and ending disparities in economic, health, and education outcomes are the ultimate goal.

However, an important question is raised by this policy: who counts as community—especially when talking about the ownership of an individual building?

Are multiple communities expected to be consolidated into one community for the sake of ease? Would that be fair to those communities?

The challenge is making ownership meaningful. Understandably, a resident may possess more pride if their stake in an INM is $1000 opposed to 20 cents.

Thus, communities that are smaller in size may be most benefited by the establishment of an INM. This is not to say that large historically-redlined areas do not stand to gain from INM establishment. Quite the contrary. INMs are designed to not only enfranchise the local communities , but also revitalize the place through restorative, economic, and environmental justice.

Nevertheless, if PTRIG is to provide communities with tools that guarantee full community empowerment, then factors of community ownership should be considered.

Now, one final question remains, and it can only be answered by those within historically-redlined communities: “Who is your community?”