Polish F-16s In NATO Nuclear Exercise In Italy

NATO is currently conducting a nuclear strike exercise in northern Italy.

The exercise, known as Steadfast Noon 2014, practices employment of U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe and includes aircraft from seven NATO countries: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Turkey, and United States.

The timing of the exercise, which is held at the Ghedi Torre Air base in northern Italy, coincides with East-West relations having reached the lowest level in two decades and in danger of deteriorating further.

It is believed to be the first time that Poland has participated with F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise.

Coinciding with the Steadfast Noon exercise, NATO is also conducting a Strike Evaluation (STRIKEVAL) nuclear certification inspection at Ghedi.

A nuclear security exercise was conducted at Ghedi Torre AB in January 2014, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment at the base.

Steadfast Noon/STRIKEVAL is the second nuclear weapons strike exercise in Italy in two years, following Steadfast Noon held at Aviano AB in 2013.

Italy hosts 70 of the 180 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

The Role of Polish F-16s

The participation of Polish F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise is noteworthy because Polish F-16s are not thought to be capable of delivery nuclear weapons or assigned nuclear strike missions under NATO or U.S. nuclear planning.

The two Polish F-16s that have been photographed at Ghedi Torre Air Base are from the 10th Tactical Squadron (ELT) of the 32nd Wing (BL) at Lask Air Base in western Poland. (Another source reported three Polish F-16s).

If Polish F-16s were directly involved in NATO nuclear strike planning, it would be a significant new development. NATO officially adheres to its “three no’s” policy, first adopted by the alliance in December 1996, according to which “NATO countries have no intention, no plan, and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members nor any need to change any aspect of NATO’s nuclear posture or nuclear policy – and we do not foresee any future need to do so.” (Emphasis added).

Since then, NATO has in fact changed the posture several times, although not eastward: In 2001, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Araxos AB earmarked for use by Greek aircraft; and later also withdrawing Incirlik AB weapons that during the first part of the W Bush administration were intended for use by Turkish aircraft (weapons for U.S. aircraft are still present at Incirlik); in 2002, by reducing the readiness level of nuclear aircraft from weeks to months; in 2003, by Germany closing Memmingen AB; in 2005, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Ramstein AB in Germany; and in 2007, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from England. Overall, these changes have resulted in a unilateral reduction of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe by 62 percent since the “three no’s” policy was adopted in 1996, from 480 to 180 today.

The Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) approved by NATO in 2012 determined that the remaining “nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defence posture.” And when asked in May 2014 if the Ukraine crisis would lead NATO to reconsider its pledge not to place nuclear weapons on the territory of new member states, then-NATO General Secretary Rasmussen said no: “At this stage, I do not foresee any NATO request to change the content of the NATO-Russia founding act.”

The 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act Agreement reference by Rasmussen echoed the 1996 policy but further explained that the three no’s policy “subsumes the fact that NATO has decided that it has no intention, no plan, and no reason to establish nuclear weapon storage sites on the territory of those members, whether through the construction of new nuclear storage facilities or the adaptation of old nuclear storage facilities. Nuclear storage sites are understood to be facilities specifically designed for the stationing of nuclear weapons, and include all types of hardened above or below ground facilities (storage bunkers or vaults) designed for storing nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added).

The 1997 Founding Act language clearly seems more focused on storage facilities rather than other parts of the posture, such as aircraft or command and control facilities that could support the nuclear mission.

Lask AB As Nuclear Staging Base?

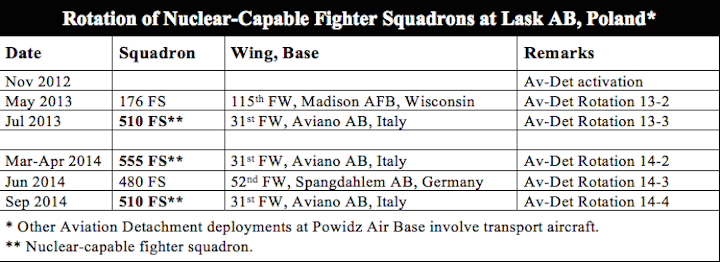

The participation of Polish F-16s from Lask AB in a NATO nuclear exercise is also interesting because the base is the primary base used by NATO aircraft deploying to Poland on temporary rotational deployments under a bilateral U.S. –Polish reinforcement treaty. Some of the U.S. squadrons that have deployed to Lask AB since 2012 are nuclear-capable.

In 2011, Poland and the United States signed an agreement to deploy a permanent U.S. Air Force aviation detachment (AV-DET) to Poland. The detachment organized under the 52nd Operations Group at Spangdahlem AB in Germany, which is also the home of the 52nd Munitions Maintenance Group that oversees the operations of the four MUNSS units deployed in four of the five western NATO countries that host U.S. nuclear weapons on their territory.

The Role of Polish F-16s

Since Polish F-16s are not nuclear-capable or assigned nuclear strike missions under U.S. and NATO strike planning, the aircraft participating in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL exercise instead are thought to serve other non-nuclear roles.

One role might be air-defense or suppression of ground-based radars. A nuclear strike would not only involve the aircraft carrying the nuclear weapon but also support aircraft to protect the strike package.

It is also potentially possible that participation of Polish F-16s reflects that NATO is working on increasing the role of conventional forces in Article V missions. The Obama administration’s nuclear employment strategy from June 2013 directed the U.S. military to “assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options” to reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

Poland is planning to equip its F-16s with the U.S.-produced Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM), a new highly accurate standoff missile that was recently approved for sale to Poland.

The U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCS) claims that Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM “will not alter the basic military balance in the region,” but the sale of the weapon to Poland (and other European countries such as Finland) in fact seems likely to do so anyway.

The only standoff weapon currently on Polish F-16s is the 23-kilometer (13 miles) range Maverick (AGM-65) [update: as several readers have pointed out (see comments below), a number of other weapons are also available]; the JASSM, in contrast, will be able to hold at risk targets at more than ten times that range with greater accuracy. Moreover, while Maverick has an optical guidance, the JASSM has all-weather GPS guidance. The JASSM is “designed to destroy high-value, well-defended, fixed and relocateable targets.” The “significant standoff range” of more than 370 kilometers (230 miles) and jam resistant GPS-guided “pinpoint accuracy,” according to Lockheed Martin, means that JASSM’s “mission effectiveness approaches a single missile required to destroy a target.”

The Pentagon says Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM missile, seen here flying through a target hole in a test, “will not alter the basic military balance” in Eastern Europe.

DSCA anticipates that Poland will use the “enhanced capability [of the JASSM] as a deterrent to regional threats and to strengthen its homeland defense.” The JASSMs and associated aircraft upgrades, according to DSCA, “will allow Poland to strengthen its air-to-ground strike capabilities and increase its contribution to future NATO operations.”

Integration of weapons such as JASSM into NATO’s posture would seem to fit well with the U.S. goal to reduce the role of nuclear weapons by providing increased conventional target destruction capability backed by a strategic nuclear deterrent that “supports our ability to project power by communicating to potential nuclear-armed adversaries that they cannot escalate their way out of failed conventional aggression,” as stated in the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review. A total of 5,000 JASSMs are planned.

Lask AB is located only 286 kilometers (178 miles) from the Belarusian border and 324 kilometer (201 miles) from the Russian border in Kaliningrad Oblast. At a speed of 1,800 kilometers per hour (1,119 miles/hour, or Mach 1.47), an F-16 launched from Lask AB would be able to reach Kaliningrad in 12 minutes and Moscow in less than an hour.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear exercise has been planned for a couple of years, the timing is delicate, to say the least, because of deteriorating East-West relations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. Russian and NATO exercises have combined to fuel a perception of a crisis that goes well beyond words to increased military posturing on both sides, reminiscent of mindsets we haven’t seen in Europe since the 1980s.

Under these conditions, there is a real risk that the tactical nuclear strike exercise at Ghedi AB with participation of Polish F-16s could feed into Russian paranoia about NATO’s military intensions. A comparable operation would be if Russia were to conduct nuclear air-strike exercises to reassure Belarus. That would deepen paranoia in eastern NATO countries and could give tactical nuclear forces in Europe a prominence that is not in anyone’s interest.

Both sides need to calm their military operations and focus on rebuilding normal relations. For Russia, that means pulling back forces from Ukrainian and NATO borders and end provocative aircraft operations near or into NATO (and Swedish and Finnish) airspace.

For NATO, that means explaining Poland’s role in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear strike exercise and the rotational deployments of U.S. nuclear-capable fighter-squadrons to Lask AB in the context of the “three no’s” policy. And it requires ensuring that reassurance of Eastern European allies does not result in conventional modernization programs or operations that deepen Russian paranoia.

Credit: Thanks to Roel Stynen of Vredesactie for first alerting me to the NATO exercise.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.